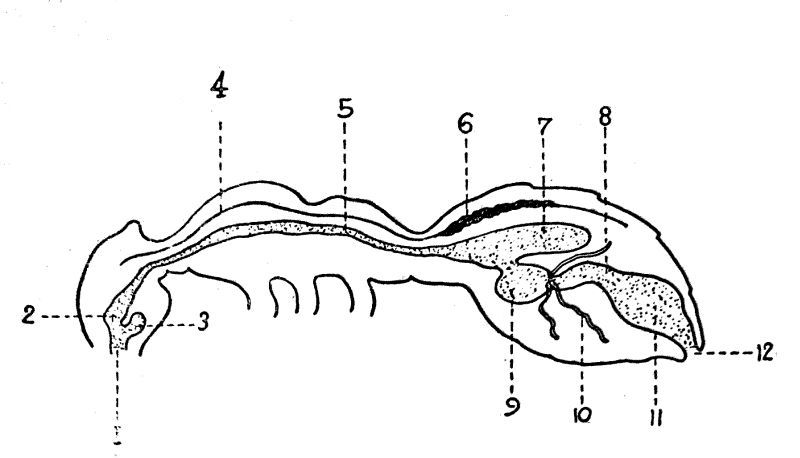

Fig. I. Diagram showing internal structure. 1, mouth; 2, pharynx; 3, infrabuccal cavity; 4, aorta; 5, esophagus; 6, heart; 7, crop; 8, small intestine; 9, stomach; 10, Malpighian tubes; 11, large intestines or rectum; 12, anal opening.

Title: Life among the ants

Author: Vance Randolph

Editor: E. Haldeman-Julius

Illustrator: Peter Quinn

Release date: January 7, 2026 [eBook #77638]

Language: English

Original publication: Girard: Haldeman-Julius Company, 1925

Credits: Carla Foust, Tim Miller and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

LITTLE BLUE BOOK NO. 833

Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius

Vance Randolph

Drawings by Peter Quinn

HALDEMAN-JULIUS COMPANY GIRARD, KANSAS

Copyright, 1925,

Haldeman-Julius Company

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

| Chapter | Page | ||

| 1. | Books About Ants | 4 | |

| 2. | The Ant’s Body | 5 | |

| 3. | Reproduction and Metamorphosis | 12 | |

| 4. | The Harvesting Ants | 20 | |

| 5. | The Mushroom Growers | 25 | |

| 6. | The Honey Ants | 30 | |

| 7. | The Legionary Ants | 36 | |

| 8. | The Red Slave Makers | 46 | |

| 9. | The Amazons and Their Slaves | 51 | |

| 10. | Dairies and Guests | 54 |

[Pg 4]

LIFE AMONG THE ANTS

There are many references to ants in the works of the ancients (Aesop, Plutarch, Horace, Ovid and Pliny), and these were quoted and elaborated by the mediaeval authors, but modern scientific investigation may be said to begin with the nineteenth century. Since then an enormous amount of work has been done by European scientists, but their papers are scattered through the files of obscure scientific journals in a great variety of continental languages, and are usually inaccessible or useless to the American student who wishes to make a serious (but not too serious) study of ant life and behavior.

The first general treatise in English was doubtless Sir John Lubbock’s famous work entitled Ants, Bees and Wasps, first published in 1881. This work was for many years a sort of standard textbook on the subject, and is still well worth looking into.

Another book which may be of use is Animal Intelligence, by George Romanes. The sixth edition, which appeared in 1895, devotes more than one hundred pages to the habits of ants.

Eric Wasmann has written a great number of books and papers about ants, one of the best of which has appeared in English as The Psychology of Ants and of Higher Animals, published in 1905. All of Wasmann’s works [Pg 5]are valuable and well worth reading, but they are marred by his constant references to philosophical and theological matters which are of no great interest to the general reader. Father Wasmann feels called upon to demonstrate that ants, as regards their psychical powers, are much nearer to man than are the anthropoid apes, and is forever interrupting himself to defend his vitalistic biology and condemn the theory of organic evolution.

By all odds the best work available on the subject is the large volume called Ants, written by Professor William Morton Wheeler of Harvard University, and published in 1910. This book is, in fact, not merely the best but the only book required by the average student. There is, of course, a great deal of material which is uncomprehensible to one who has no particular technical background, but the whole thing is so admirably arranged that the student has only to glance through the table of contents to locate matter suited to his taste and training. I have made a very free use of Ants in the preparation of this booklet, some sections of which are little more than epitomes or abstracts of Wheeler’s chapters.

The body of the ant, like those of other insects, is segmented, and covered with a hard chitinous external skeleton. It is separated by constrictions into three distinct parts, the head, which bears the eyes and mouth-parts; [Pg 6]the thorax, to which the wings and legs are attached; and the abdomen, which contains most of the entrails and the sexual apparatus.

The Head, Eyes, and Mouth-parts. The head varies greatly in shape and size, but always bears a frontal plate or clypeus, just above which the two jointed antennae or feelers are attached. The antennae contain a great number of minute structures which are supposed to be connected with the sense of smell. Three small simple eyes or ocelli are set in the top of the head, and two large compound eyes are located one on either side. The eyes are always very well developed in the males, and somewhat less so in the females; the eyes of the workers are relatively small, and the ocelli are sometimes lacking altogether. The compound eyes are the principal organs of vision, while the ocelli are supposed to register only very near objects.

Just below the clypeus are the mouth-parts, consisting of the labrum or upper lip, a pair of powerful mandibles, another pair of jaws called maxillae, and the labium or lower lip. Both maxillae and labium bear little palpi or feelers, and are plentifully supplied with taste-buds containing the gustatory cells. The tongue or glossa with which the ant laps up its food is attached to the upper part of the labium.

The Thorax, Legs and Wings. The ant’s thorax consists of four segments. The first segment is known as the prothorax; it is quite small, and bears the first pair of legs. The next segment, the mesothorax, carries the second pair of legs and the front wings—when [Pg 7]wings are present. The third segment or metathorax bears the third pair of legs and the hind wings—if there are any wings. The fourth segment is really a part of the abdomen, and is known as the epinotum. On each side of the thorax are two breathing-holes or stigmata, which communicate directly with the tracheae or windpipes which supply air to the interior tissues.

The ant has six legs, one pair attached to each of the three segments of the thorax proper. Each leg consists of five parts, the coxa, the trochanter, the femur, the tibia, and the tarsus or foot. The wings are four in number, and the venation is similar to that found in other members of the order Hymenoptera, but the wings are not much used in classification because the workers are always wingless, and the females wear wings only for a part of their lives.

The Abdomen and Its Appendages. The ant’s abdomen is divided into two parts, the slender pedicel which articulates with the last segment of the thorax, and the larger part of the abdomen called the gaster. The pedicel is provided with a file-like structure, which by rubbing against a non-striated segment produces a sound of very high pitch. In some species the females and workers bear stings and poison glands in the last segment of the gaster. The female has no ovipositor. In the male the tip of the gaster usually bears three pairs of sexual appendages; the two outer pairs are used in clasping the female during copulation, and the inner pair, when held tightly [Pg 8]together, form a tube which functions as a penis.

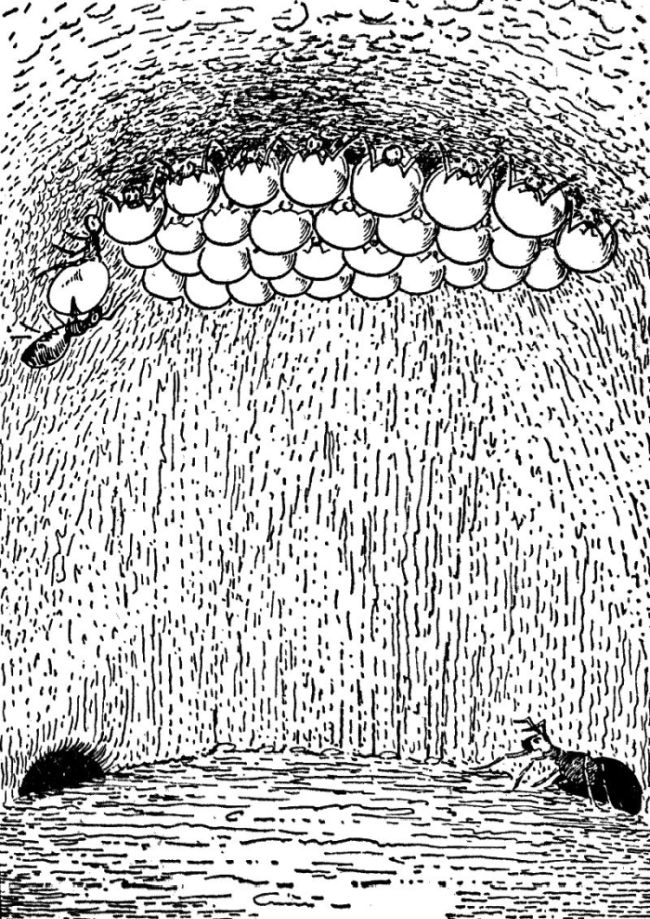

The Alimentary Canal. The mouth is located between the maxillae, and is provided with a little pouch called the infrabuccal cavity, which is used to hold solid matter while the liquid nutriment is being sucked out of it. When this has been accomplished the pellet is thrown out. The liquid food passes back into the pharynx, and then on through a slender tube called the esophagus, which is lined with fine hairs. In the gaster the esophagus expands into the crop, which acts as a reservoir; no food is absorbed through its walls, but is often regurgitated to feed the young. Just back of the crop is the proventriculus or gizzard, the movements of which provide the suction by which liquid is drawn up the esophagus and into the crop, and the force by which food is regurgitated. The true stomach is rather small, and it is here that the food is both digested and absorbed. The small intestine communicates with the stomach by a valve, and is connected with a number of Malpighian tubes which act as kidneys, absorbing liquid waste from the blood and pouring it into the intestine. The large intestine or rectum receives the feces and urine from the small intestine and expels them from the body by way of the anal opening.

The Circulatory System. The blood of the ant, like that of other insects, is colorless, and contains several kinds of corpuscles. [Pg 9]

Fig. I. Diagram showing internal structure. 1, mouth; 2, pharynx; 3, infrabuccal cavity; 4, aorta; 5, esophagus; 6, heart; 7, crop; 8, small intestine; 9, stomach; 10, Malpighian tubes; 11, large intestines or rectum; 12, anal opening.

Its function is to carry food from the stomach where it is absorbed to other parts of the body where [Pg 10]it is needed. The blood of insects has no red corpuscles, and does not carry oxygen about. The blood is not confined in definite veins and arteries as in the higher animals, but percolates about through the entire body cavity. There is a simple heart in the dorsal part of the abdomen which pulsates and forces blood forward through an aorta into the head, from which it seeps gradually back into the abdomen, to be pumped forward through the aorta again. Thus a sluggish circulation is maintained.

Respiration. Ants have neither lungs nor gills, and the blood does not carry oxygen into the cells and carbon dioxide out as in the higher animals. As in most other insects, air is taken into the body through breathing-holes or stigmata, and brought into direct contact with the tissues. There are ten pairs of these stigmata in the ant—two pairs in the thorax and eight in the abdominal segments. Each opens through a sort of valve into a trachea or wind-pipe, which branches until its ramifications extend to all parts of the body. When certain muscles contract the size of the body increases, and air is drawn in through the stigmata; when the size of the body is decreased the air is forced out. The incoming air brings in the necessary oxygen, and the outgoing current is laden with carbon dioxide waste from the tissues.

The Nervous System. The brain proper is a mass of nerve matter in the head just above the esophagus, but the subesophageal ganglion is very close to it, and the two are connected [Pg 11]by heavy fibers on each side of the esophagus, so that the whole thing has the appearance of a brain with the gullet running through the middle of it. The major part of the upper brain is connected with the compound eyes, but there are nerves also which supply the ocelli, the antennae, the pharynx, the labrum, and muscles in the head. The subesophageal ganglion gives off nerves to the mandibles, maxillae and labium. From the lower back part of the subesophageal ganglion the ventral nerve cord arises, and runs through the thorax and far back into the abdomen. This cord bears three large thoracic ganglia which innervate the muscles of the wings and legs. In the abdomen are eleven smaller abdominal ganglia, with nerves running out to supply all of the abdominal organs. The so-called sympathetic system consists of a few very small ganglia and nerves not directly connected with the ventral nerve cord, which function in connection with the digestive organs.

The Reproductive Organs. The ovaries of the female or queen ant are located in the upper and front part of the gaster, and each is connected by a slender oviduct with the uterus. The uterus is continuous with the vagina, the external opening of which is located near the tip of the abdomen. At the top of the uterus is a small pouch called the seminal receptacle, which receives the sperm from the male in copulation. The spermatozoa live in this pouch for several years, and meet and fertilize the eggs as they descend into the uterus from the ovaries.

[Pg 12]

The organs of the worker are similar to those of the queen, except that they are very much smaller, and are usually incapable of functioning normally. Worker ants have never been seen to copulate. The testes of the male ant are located in the front part of the gaster, and are connected by the vas deferens with the seminal vesicles. Tubes from the vesicles unite to form the ejaculatory duct, which is connected with the penis at the tip of the abdomen.

Like their relatives the bees and wasps, ants have developed two types of females, so that a colony contains three distinct sorts of individuals, known as males, females, and workers.

The Male. The male is less subject to variation than either the queen or the worker. The body is usually slender and graceful, the eyes and antennae are well developed, and the mouth parts rather small and weak. In most species the male is winged. As in the bees, the one great function of the male in the colony is to copulate with the female or queen, so as to supply her with sperm to fertilize future eggs. The male is not killed in the course of the sexual embrace, as the drone honeybee is, but usually dies soon afterward.

The Female. The true female or queen is usually larger than either the male or the worker; the head, eyes, and mandibles are well developed, and the abdomen is very large to contain the reproductive organs. The female [Pg 13]is usually winged at the time of mating, but the wings are loosely attached and she loses them as soon as the nuptial flight is over. The wings and legs are stouter and shorter than those of the male, in most cases. In a few species the females have no wings, and in others it is the males which are wingless. No case is known in which neither male nor female is provided with wings.

The Worker. The worker is an undeveloped, wingless female. The eyes are small, and the ocelli are often lacking; the antennae, legs, and mouth parts are strong and well developed. There is a great deal of variation among workers; one common variant is the dinergate, or soldier—a form with a very large head and mandibles adapted to fighting. The sex organs of the worker are unquestionably female, but they do not ordinarily function, and a worker has never been seen to copulate.

Mating. In species in which both the male and female are winged, mating occurs in the air, as in the nuptial flight of the queen bee. In the case of the honeybee, however, there is only one queen to a great number of drones, while with the ants there may be hundreds of queens and drones in the air, all copulating at once. Another difference is that the mated females do not often return to the parent colony, as the queen bee always does. When the mating hour draws near all the ants, even the nearly blind and wingless workers, rush out of the nest in great excitement, and the air is soon full of flying ants. Copulation usually begins high in the air, but the linked pairs often fall [Pg 14]to the ground together. In the mating of bees the male is almost always instantly killed, the genital organs and entrails being torn out of his body. This mutilation never happens among ants, but the male’s life-work is ended with the sexual act, and he usually dies shortly afterward.

The New Colony. As soon as the mated female is upon solid ground again she tears off her wings, or removes them by rubbing against some solid object. This done, condemned to a crawling, terrestrial existence for the rest of her days, she sets out alone to establish a new colony. She digs a hole in the ground, or in rotten wood, or under a flat stone, seals up the opening, and sits down in the dark until the eggs in her abdomen are mature. Sometimes this takes weeks or even months, and during this time the queen has nothing to eat, but lives by absorbing the large wing-muscles which she will never use again. Finally the eggs are deposited, being fertilized by some of the spermatozoa which were obtained from the male, and which are stored in the spermatheca, a little pouch just above the uterus. When the larvae hatch she feeds them with a secretion from her salivary glands. The resulting ants are normal workers, except that they are unusually small. Sometimes it takes nearly a year to rear this first brood, and all this time the queen has eaten absolutely nothing. As soon as the workers are old enough they dig passages to the open air, and enlarge the nest by adding galleries and runways. They drag in food and feed the exhausted female, [Pg 15]who from this time forward does nothing but eat and lay eggs—the brood being cared for entirely by the workers. From now on the female is a timid, photophobic, rickety old egg-laying machine. During her long fast the great wing-muscles have been absorbed, leaving the thorax hollow, so that she floats if placed in water. Only a very few females can survive the ordeal necessary to found a new colony—probably only one of many thousands which undertake it. It is a beautiful example of the Darwinian phenomena of survival.

The procedure described above is the usual one in most species of ants. It was guessed at by Huber in 1810, but the first man to watch the actual founding of a new colony was an American named Lincecum, about 1866. In 1879 Sir John Lubbock observed the whole process in an artificial nest, and his account of the process has since been verified by numerous other investigators.

In certain species, however, the queen is unequal to the task of founding a family in this manner. In this case she must return to the parent colony, join a queenless colony of her own or an allied species, or raid a small colony of aliens. In this latter event she kills them all, and adopts their eggs and brood.

Complete Metamorphosis. Like the butterflies and beetles, ants have a complete metamorphosis, that is, they pass through four distinct developmental stages. In many other insects—the grasshoppers for example—the metamorphosis is said to be incomplete, because the newly hatched young have the same [Pg 16]general form as the adult, and their development is merely a matter of increase in bulk.

The Egg. Ant’s eggs are very small, rarely more than one-fiftieth of an inch in length, and are very seldom seen by the casual observer, who mistakes the comparatively large cocoons for eggs. The egg is usually elongated, and consists of the germinal spot, the yolk, and the thin transparent shell called the chorion. The eggs look very much alike, and one cannot predict whether a given egg will produce a male, a worker, or a queen. Some eggs are fertilized by sperm stored in the female’s spermatheca, others are deposited without fertilization, while those laid by workers are certainly not fertilized, since workers do not copulate. In bees and certain other related insects it has been found that unfertilized eggs always produce males, but whether this is always true in ants is still an open question.

Very little is known of the embryological development of the ant, but the unhatched larva certainly has traces not only of antennae and legs, but remnants of certain abdominal appendages not present in the adult ant, and evidently harking back to more remote ancestors. The egg usually hatches about twenty days after it is laid, but the length of this period varies greatly with the temperature.

The Larva. The newly hatched larva is a soft, semi-transparent grub, with a fat body, slender crooked neck and small head. There are no eyes, but the mouth-parts are fairly well developed, and ten pairs of stigmata are usually present.[Pg 17]

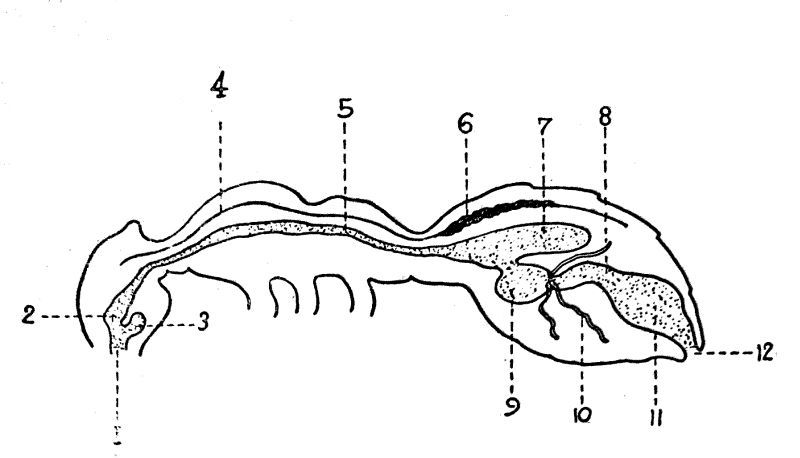

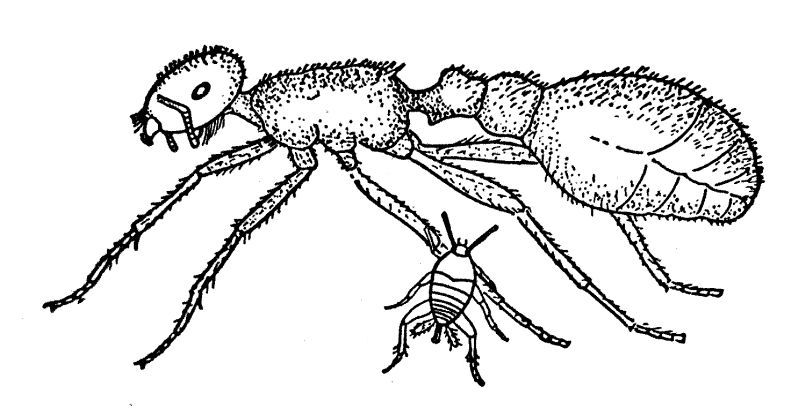

Fig. II. Cross-section of an ant-hill, showing the arrangement of larvae and pupae according to size. (Adapted from Andre.)

The body is covered with [Pg 18]short fine hairs. The digestive system is well formed, but there is no connection between the stomach and the intestine, so that the larva has no movement of the bowels until it is about to transform into the next stage. The accumulated feces in the lower part of the stomach may often be seen as a black spot showing through the semi-transparent walls of the body.

The larva is fed by the workers, the food being either regurgitated liquid food or pieces of fresh vegetable or animal matter. It has been found in the case of the bees that the kind of food given the larva determines whether it will develop into a queen or a worker, but we have no definite information about this matter among the ants.

When the larva is fully grown, usually about a month after hatching, it is buried in the ground by the workers, and spins a silken cocoon about itself. All ant larvae have spinning organs in the head, but some do not spin cocoons, and in this case are not buried, but undergo their metamorphosis in the open chambers of the nest. The larva now voids its accumulated feces, sheds the larval skin, and appears as the pupa, the third stage in the ant’s development.

The Pupa. In the pupal stage the ant has most of the appendages and organs of the adult, but they are small and folded close against the body. The pupa lies quietly, is not fed, and ordinarily gives no signs of life at all. Gradually the various parts develop, the darker color of the adult appears, until [Pg 19]finally the mature pupa has very much the appearance of the imago. Then the cocoon is opened by the attendant workers, the young ant dragged out and fed, and begins its life as an adult. The pale, newly emerged ant is known as a callow. The pupal stage usually lasts from fifteen to twenty days, but is sometimes much longer in cold weather.

The Adult. The general appearance and characteristics of the adult are described elsewhere in this book. The total time of development from the deposition of the egg to the appearance of the callow varies from about sixty days to five months, and is considerably longer than the corresponding period in most other insects. The queen bee, for example, passes through all three stages in about sixteen days, while some butterflies are developed in less than twenty-five days. Another interesting feature is the extreme longevity of the adult ant. The males are short-lived, but the workers of many species live for four or five years, and the queens for still longer periods. Janet kept one for fully ten years, and Sir John Lubbock had a queen in his possession from December, 1874 to August, 1888, “when she must have been nearly fifteen years old, and, of course, may have been more,” since he had no means of knowing her age at the beginning of her captivity.

[Pg 20]

The works of Pliny and other ancient writers contain references to ants which collected great stores of seeds, and these accounts were quoted by numerous mediaeval authors. Modern students of ants, however, worked mostly in northern and central Europe, and as they did not find any of these harvesting ants they were rather inclined to dismiss the classic stories as fiction pure and simple, and class the seed-gathering ants with the unicorn and the mermaid.

In 1829, however, one W. H. Sykes, an Englishman located in India, reported that certain ants near his station not only collected great quantities of grass seed, but after a heavy rain could always be seen bringing their cereal out of the underground granaries to dry it in the sun. These observations went far to vindicate the ancient naturalists, and the work of J. T. Moggridge, in 1873, completed the vindication. Moggridge watched the workers bring in the seeds, bite off the germinating part to prevent the seeds from sprouting, and store them in the nests, which often contain a pint or so of grain. By examination of these hoards he identified as many as eighteen different families of plants represented in a single nest. Despite the efforts to prevent germination by biting off the radicles (a fact noted by Pliny some sixteen hundred years before) many of the seeds do sprout, and thus the harvesting [Pg 21]ants play a part in the distribution of plants. Of this subject Moggridge says: “As the ants often travel some distance from their nest in search of food, they may certainly be said to be, in a limited sense, agents in the dispersal of seeds, for they not infrequently drop seeds by the way, which they fail to find again, and often also among the refuse matter which forms the kitchen hidden in front of their entrances, a few sound seeds are often present, and these in many instances grow up and form a little colony of strange plants. This presence of seedlings foreign to the wild grounds in which the nest is usually placed, is quite a feature where there are old established colonies of Atta barbara, where young plants of fumitory, chickweed, cranesbill, Arabis thaleana, etc., may be seen on or near the rubbish heap.... One can imagine cases in which the ants during the lapse of long periods of time might pass the seeds of plants from colony to colony, until after a journey of many stages, the descendants of the ant-borne seedlings might find themselves transported to places far removed from the original home of their immediate ancestors.”

There are many species of harvester ants in America; one of the most interesting is Solenopsis geminata, popularly known as the fire-ant because of its readiness to use its painful sting. Although the fire-ant certainly stores up seeds, often to the extent of damaging crops of soft fruits like strawberries, it will also eat insects, or almost anything else that it can get. The nests are usually found beneath [Pg 22]flat stones, and in some localities are so common and so populous that Wheeler refers to the fire-ant as being “in possession of a large portion of the soil of the American tropics.” In Louisiana and other southern states these ants nest along the shores of lagoons and bayous; when the floods come and the nest is submerged the workers cling together in a ball as much as eight inches in diameter, with the brood in the center. This ball floats in the water, the ants constantly shifting about so that very few are drowned, and very little brood lost, until they are able to effect a landing.

The so-called Texas harvester (Pogonomyrmex molefaciens) has become famous because a man named Lincecum, about 1862, published a paper in which he claimed that this ant actually plants seeds in the ground, weeds and cultivates its fields all summer, gathers the crop, dries it in the sun, and finally stores it away in subterranian granaries. This story was accepted and promulgated by Charles Darwin, and so was believed in many quarters. It seems to rest solely upon the fact that ant-rice (Aristida) is usually found growing about the nest, although it may occur nowhere else in the immediate vicinity. “Four years of nearly continuous observation,” writes Wheeler, “enable me to suggest the probable source of Lincecum’s misconception. If the nests of this ant can be studied during the cool winter months—and this is the only time to study them leisurely, as the cold subdues the fiery stings of their inhabitants—the seeds, which [Pg 23]the ants have garnered in many of their chambers will often be found to have sprouted. Sometimes, in fact, the chambers are literally stuffed with dense wads of seedling grasses and other plants. On sunny days the ants may often be seen removing these seeds when they have sprouted too far to be fit for food and carrying them to the refuse heap, which is always at the periphery of the crater or cleared earthen disk. Here the seeds, thus rejected as inedible, often take root and in the spring form an arc or a complete circle of growing plants around the nest. Since the Pogonomyrmex feeds largely, though by no means exclusively, on grass seeds, and since, moreover, the seeds of Aristida are a very common and favorite article of food, it is easy to see why this grass should predominate in the circle. In reality however, only a small percentage of the nests, and only those situated in grassy localities, present such circles. Now to state that molefaciens, like a provident farmer, sows this cereal and guards and weeds it for the sake of garnering its grain, is as absurd as to say that the family cook is planting and maintaining an orchard when some of the peach stones, which she has carelessly thrown into the backyard with the other kitchen refuse, chance to grow into peach trees.”

Wheeler has also observed the mating flight of the Texas harvester, and his graphic description is worth setting down in its entirety: “During three successive years (1901-1903) at Austin, Texas, the nuptial flight of molefaciens took place on one of the last days [Pg 24]of June (28 and 29) or the first in July. On one of these occasions (July 4, 1903) the flight was of exceptional magnitude and beauty. A few days previous the country had been deluged with heavy rains, but Independence Day was clear and sunny, the mesquite trees were in full bloom and the air resounded with the hum of insects. For several days I had seen a few males and winged females stealthily creep out of the nest entrance as if for an airing, but hurry back at the slightest alarm. From 1:30 to 3 o’clock, however, on the afternoon of July 4, all the numerous colonies I could visit during a long walk west of the town, gave forth their males and females as by a common impulse. The number issuing from a single large nest was often sufficient to have filled a half liter measure. Soon every mound and disk was covered with the bright red females and darker males, intermingled with workers, many of whom kept on bringing seeds and dead insects into the nest as unconcernedly as if nothing unusual were happening. The males and females, quivering with excitement, mounted the stones or pebbles of the nest or hurriedly climbed onto the surrounding leaves and grass and rocked to and fro in the breeze. Then, raising themselves on their feet and spreading their opalescent wings, they mounted obliquely one by one into the air. I could follow them only for a distance of ten or twenty meters when their rapidly diminishing bodies melted away against the brilliant cloudless sky. Many pairs, hesitating to take flight, chased one another about on the surface [Pg 25]of the nest. The amorous males seized many of the females before they could leave the ground. Lizards crept forth in great numbers and gulped down quantities of the fat females, while others were borne off into the air by large robber flies (Asilidae). By a little after three o’clock the males and females had left the nest and only the workers were seen pursuing the quiet routine business of bringing in seeds.”

In tropical and subtropical America there are about one hundred species and varieties of ants which have most extraordinary habits, and are grouped together in the Myrmicine tribe Attii. These ants are usually rather small and dull colored, and, while they are powerful and industrious diggers, are not given to rapid movements as most ants are, but walk slowly and sedately about. When picked up they do not struggle as many other ants do, but feign death after the manner of certain well known beetles.

It was long noted that the Attii carried great quantities of leaves into their nests, and there was considerable doubt as to the use to which these were put, some observers believing that they were used immediately as food, and others contending that they served as roofing and carpets in the underground passageways. Belt, a naturalist who lived in Nicaragua, [Pg 26]was probably the first to discover the secret of the leaves. Digging into one of the nests in his garden, he was surprised to find no great quantity of leaves in any of the passages, although ants were continually bringing them in at the entrance. The chambers were always partly filled with “a speckled, brown, flocculent, spongy-looking mass of a light and loosely connected substance.... This mass, which I have called the ant-food, proved on examination to be composed of minutely subdivided pieces of leaves, weathered to a brown color, and overgrown and lightly connected together by a minute white fungus that ramified in every direction throughout it.... When a nest is disturbed and the masses of ant-food spread about, the ants are in great concern to carry away every morsel of it under shelter again; and sometimes, when I dug into the nest, I found the next day all the earth thrown out filled with little pits that the ants had dug into it to get out the covered up food.”

Further investigation brought Belt to the conclusion that the Attii do not eat leaves at all, but use them as manure to grow fungus on; and further, that they feed upon this fungus, and will eat nothing else. The Attii are, in Belt’s own phrase, “mushroom growers and eaters.” While leaves are the chief fertilizer, other substances are often found suitable for growing fungus on; flowers are sometimes used, and some species are particularly partial to pieces of orange peel. The temperature and ventilation of the subterranean gardens [Pg 27]are matters of great importance, and there are many small holes which connect the larger chambers with the surface. These air-shafts are plugged and reopened at intervals, and by this means the temperature and ventilation are regulated.

Alfred Moeller was a naturalist who studied the Attii in Brazil, and published the results of his labors in 1893. He found that the gardens contain only one kind of fungus, all alien spores being carefully weeded out. The ants do not allow the fruits to develop, and this has made the classification of the fungi a very difficult matter. The fungi found in the Attii nests are different from any others known, but no one can tell whether they are really distinct species or merely modified forms of certain common moulds or mushrooms.

Von Ihering, in 1898, discovered that the virgin queen, when leaving the nest on her nuptial flight, always carries a little pellet of fungus in her mouth. After being fertilized by the male the queen shuts herself up in a little burrow and sets about the founding of a new colony. There are in this case no leaves available, and she starts the fungus growing upon some of her new-laid eggs, which she crushes for the purpose, and which seem to work quite as well as the usual vegetable fertilizer.

J. Huber, in 1905, studied the same problems which interested Von Ihering, and concluded that the fungus is not grown upon crushed eggs, but is nourished by the liquid [Pg 28]excrement of the queen. He describes his observations as follows: “After watching the ant for hours she will be seen suddenly to tear a little piece of the fungus from the garden with her mandibles and hold it against the tip of her abdomen, which is bent forward for this purpose. At the same time she emits from her vent a clear yellowish or brownish droplet which is at once absorbed by the tuft of hyphae. Hereupon the tuft is again inserted, amid much feeling about with the antennae, in the garden, but usually not in the same spot from which it was taken, and is then patted into place by means of the fore feet.... According to my observations, this performance is repeated usually once or twice an hour, and sometimes, to be sure, even more frequently.” Although, according to Huber, the eggs are not used directly as fertilizer for the fungus, the same result is brought about indirectly, as the female is accustomed to feed upon her own new-laid eggs. Huber estimates that nine out of every ten eggs laid are eaten at once by the mother. The young larvae, too, are fed with eggs thrust directly into their mouths by the queen. When the adult workers appear, however, they live exclusively on the fungus which has been growing during their larval life, and feed the queen upon fungus also, while continuing to supply the larvae with their mother’s eggs. After a week or so the workers dig their way out of the chamber, bring in leaf-manure for the garden, and the fungus is no longer cared for by the queen, who now gives all her attention to the serious [Pg 29]business of egg-laying. As the fungus becomes more abundant under this cultivation it is fed to the larvae also, and eggs are no longer used as food by any of the individuals in the hive.

The extraordinary habits of the Attine ants have fascinated many students, and a number of theories about their development have been advanced. Forel suggested that the ancestors of the present mushroom-growers must have lived in rotten wood, and fed upon the fungus which grew upon the moist walls of their nests, or upon insect excrement. Von Ihering thinks that they may have developed from the harvesting ants, which gradually acquired such an appetite for the fungus which happened to grow in their granaries that the original stores came to be used only as fertilizer. Wheeler points out that, besides the Attine ants, there are several kinds of beetles and termites which cultivate fungus upon their own excrement, and suggests that originally this was the method employed by the ants. Later on they came to use the excrement of other insects, and finally passed to the addition of leaves and other non-fecal vegetable matter.

As has been said above, the Attii are primarily tropical and subtropical insects, but a few species have come north into the United States. They are found chiefly in peninsular Florida, in southern Texas, and in Arizona, although one species has been reported as far north as southern New Jersey.

[Pg 30]

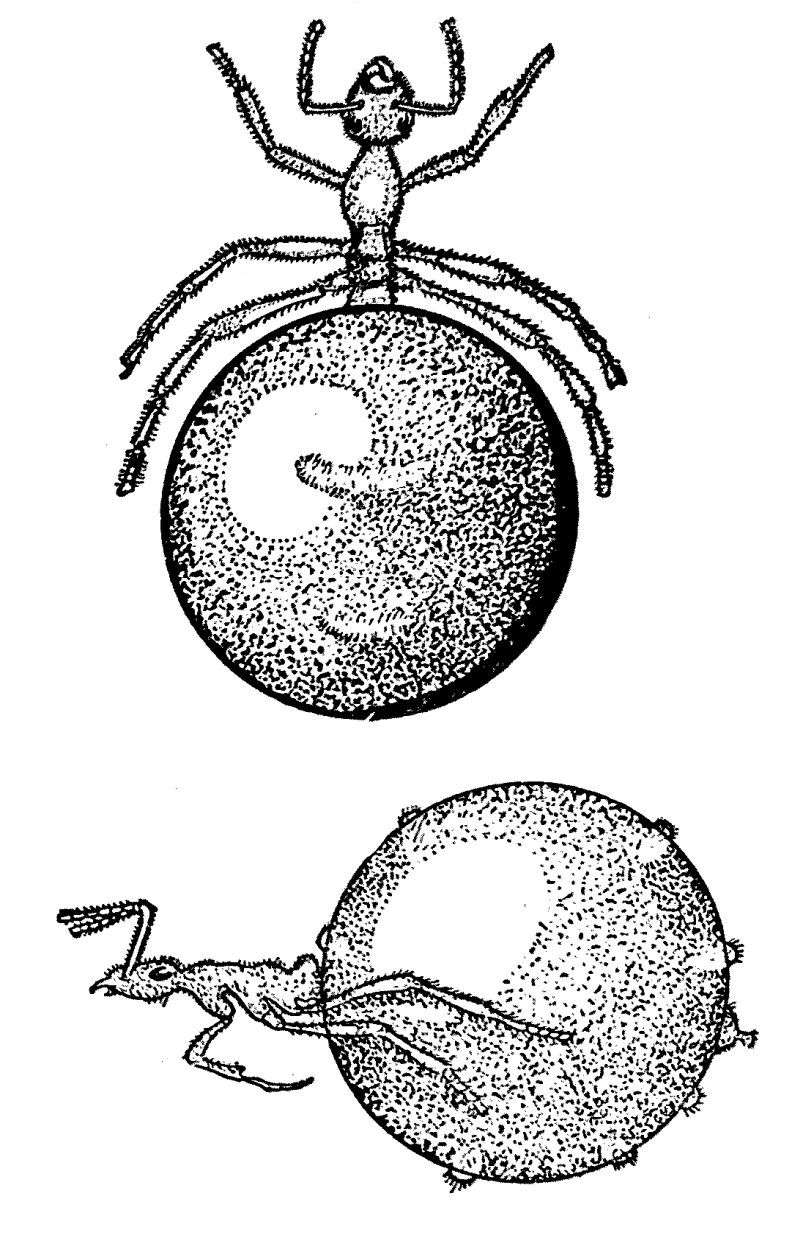

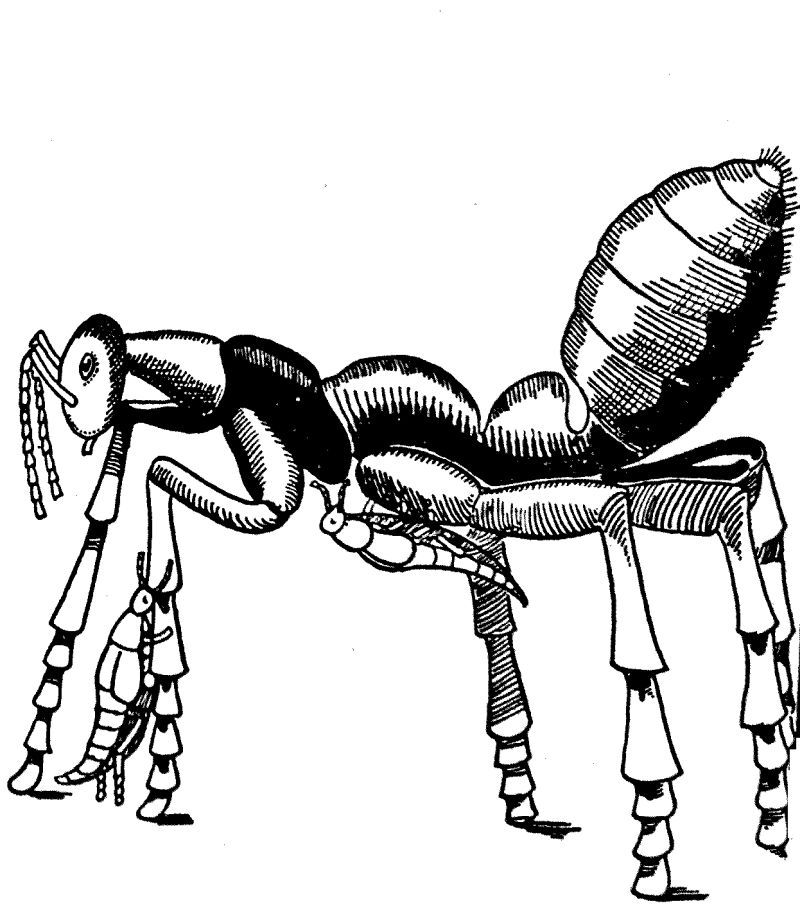

Many species of ants are in the habit of collecting nectar from flowers, and the sweet juices excreted by plant-lice, until the crop is greatly swollen. When they arrive at the nest, however, the sweets are soon regurgitated and fed to the larvae. Any worker ant is able to expand its crop to a certain extent, but in some species this power is developed to an enormous degree. In still other tribes this peculiar capacity seems to be limited to certain individuals. In the true honey ants only a comparatively small number of workers are capable of this honey-carrying, and these individuals are known as honey-bearing or repletes. The repletes never accompany the other workers on their foraging expeditions, but remain always in the nest, and are used as living bottles in which to store the nectar brought in from the fields.

In some North American species of Myrmecocystus the abdomen is distended to such an extent that the repletes are unable to move about without serious danger of bursting open, and spend their lives hanging in clusters from the ceilings of certain chambers in the nest. These honey ants are found in desert regions from central Mexico as far north as Denver, Colorado, and have since ancient times been highly prized as sweetmeats by the aborigenes of this region.[Pg 31]

Fig. III. Repletes of a common honey-ant. (From a drawing by Wheeler.)

Honey ants were described in Mexican publications as long ago as 1832, but the first important study was made by McCook, [Pg 32]whose investigations were carried out in the so-called Garden of the Gods, near Manitou, Colorado, about 1882. He found several very large nests, covering an area of more than six feet in diameter, and extending three feet below the surface of the ground. One of these nests contained some three hundred replete honey-vessels hanging by their claws from the ceiling, and so distended with honey that, once fallen from their positions, they were quite unable to get back up again. McCook saw the ordinary workers bringing in great quantities of nectar and honeydew, which was immediately regurgitated and fed to the repletes or rotunds, as he called them, and thus stored up in a living reservoir until needed.

It was formerly supposed that the sweet liquid was kept in the stomach of the replete, but Forel, in 1880, showed that it is in reality the enormously distended crop which functions. McCook made careful dissections which bore out Forel’s views, and demonstrated that the replete has all the abdominal organs of the ordinary worker, although these are flattened against the body wall and rendered inconspicuous by the distension of the crop.

McCook rejected the view that the replete belongs to a separate caste, saying that “a comparison of the workers with the honey-bearer shows that there is absolutely no difference between them except in the distended condition of the abdomen....[Pg 33]

Fig. IV. Repletes of a honey-ant (Myrmecocystus hortideorum) hanging from the roof of a honey chamber. (After McCook.)

The process by which the rotundity of the honey-bearer has probably been produced, has its exact counterpart in the ordinary distension of the crop in [Pg 34]overfed ants; the condition of the alimentary canal, in all the castes, is the same, differing only in degree, and therefore the probability is very great that the honey-bearer is simply a worker with an overgrown abdomen.... Thus workers are transformed by the gradual distension of the crop and expansion of the abdomen into honey-bearers, and the latter do not compose a distinct caste.”

Just why these repletes should be developed in some species and not in others is a mooted question. The fact that they are found only in desert regions in North America, Australia, and South Africa may mean that a dry climate is one of the important conditions of the phenomena. Forel said: “The extraordinary distension of the crop seems to be frequent in the Australian species of the general Melophorus, Gamponotus and Leptomyrmex. I suppose that this is due to the extremely dry climate of the country, which must compel the ants to remain, often for long periods, in their subterranean abodes. At such times a store of provisions in living bags must be very useful to them.” Wheeler, in commenting on the above statement by Forel, writes: “There can be little doubt of the truth of this statement, but I believe that it should be expressed in a different manner. The impulse to develop repletes is probably due to the brief and temporary abundance of liquid food (honeydew, gall secretions, etc.) in arid regions and the long period during which not only these substances, but also insect food are unobtainable. The honey is stored in the living reservoirs for the purpose of tiding [Pg 35]over such periods of scarcity, and the ants remain in their nests because they do not need to forage. Hence the confinement mentioned by Forel is not the immediate but one of the ulterior effects of drought. I am convinced from my observations on desert ants that no amount of drought will keep these insects in their nest when they are in need of food.

“While excavating the nests of M. hortideorum I was impressed with certain peculiarities in their structure and situation, which seem to be explainable only as adaptations to the development of repletes. One of these peculiarities is the great hardness of the soil that is preferred by the ants. This is the more astonishing because the workers are very slender and delicate organisms. It is evident that such soil is well adapted to the construction of vaulted chambers like those in which the repletes hang, whereas soft or friable soil would be most unsuitable. The development of repletes also makes it necessary for the ants to seek very dry situations for their nests. Hence we always find them, in the environs of Manitou at least, on the summits of ridges which shed the rain very rapidly. The honey chambers must be kept dry, both to prevent the disastrous results of crumbling and slipping walls and to obviate the growth of mould on the repletes, which are, of course, imprisoned for life in dark cavities and filled with substances that are favorable to the development of fungi. I believe also that the size of the nest openings and galleries, which [Pg 36]are so much larger than would seem to be required by such small, slender ants, may be an adaptation to securing plenty of fresh air in the honey chambers. If these suppositions are correct, there is obviously a reciprocal relation between the replete habit and an arid environment: the ants store honey because they are living in an arid region where moisture and food are precious, and the storing of honey in replete workers, in turn, is possible only in very dry soil.”

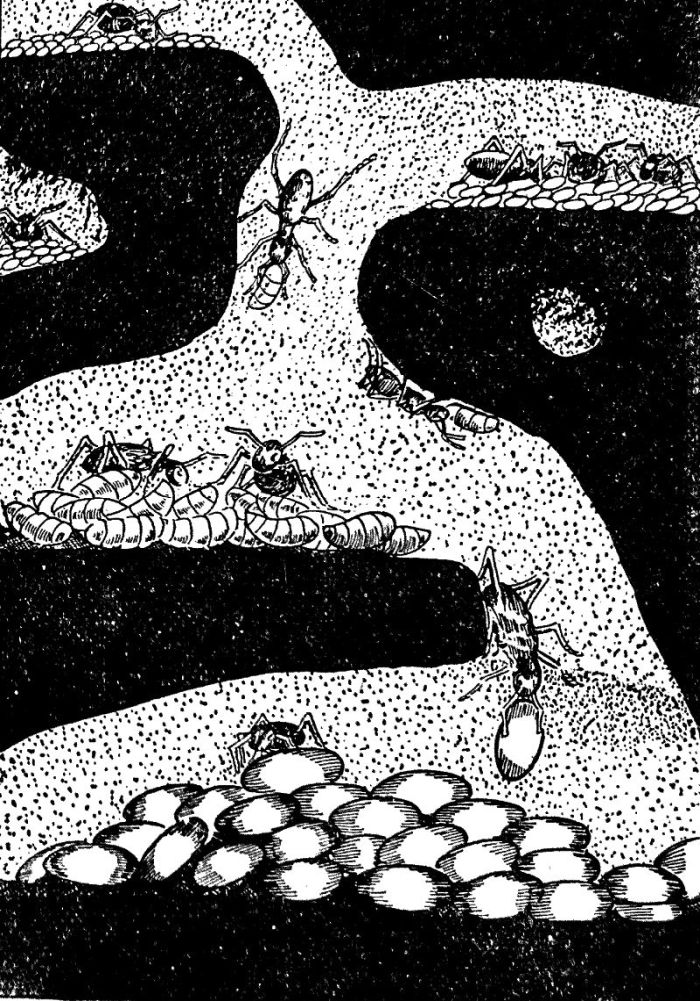

These insects, which Wheeler describes as “the Huns and Tartars of the insect world,” are found in tropical Africa and Asia, and in the warmer parts of America. There is a great variation in size and appearance between the different castes, the females and workers being blind and wingless, while the males have well developed wings and large compound eyes. Some of these ants have no fixed habitation, but wander from place to place, traveling mostly at night, and camping during the day in any shallow hole that affords a temporary shelter. They cannot endure the direct rays of the sun, and Savage, in 1845, observed that “if they should be detained abroad till late in the morning of a sunny day by the quantity of their prey, they will construct arches over their path, of dirt agglutinated by a fluid excreted from the mouth,” except when they can remain concealed by thick grass or leaves. [Pg 37]Sometimes the soldier ants form a sort of network arch with their own bodies, and Savage says that “whenever an alarm is given the arch is instantly broken, and the ants, joining others of the same class on the outside of the line, who seem to be acting as commanders, guards and scouts, run about in a furious manner in pursuit of the enemy. If the alarm should prove without foundation, the victory won or the danger passed, the arch is quickly renewed, and the main column marches forward as before in all the order of a military discipline.”

In these marches the ants carry their eggs, larvae and pupae with them, these being borne in the mandibles of the minima or small workers, and the whole column lives by foraging. Savage’s description of their predatory habits is well worth quoting here: “They will soon kill the largest animal if confined. They attack lizards, guanas, snakes, etc., with complete success. We have lost several animals by them—monkeys, pigs, fowl, etc. The severity of their bite is increased to great intensity by vast numbers, to a degree impossible to conceive. We may easily believe that it would prove fatal to any animal in confinement. They have been known to destroy the Python natalensis, our largest serpent. When gorged with prey it lies motionless for days; then, monster as it is, it easily becomes their victim.... Their entrance into a house is soon known by the simultaneous and universal movement of rats, mice, lizards, Blapsidae, Blattidae, and of the numerous other [Pg 38]vermin that infest our dwellings. Not being agreed, they cannot dwell together, which modifies in a good measure the severity of the driver’s habits, and renders their visits sometimes (though very seldom in my view) desirable. Their ascent into our beds we sometimes prevent by placing the feet of the bedsteads into a basin of vinegar, or some other uncongenial fluid; this will generally be successful if the rooms are ceiled, or the floors overhead tight; otherwise they will drop down upon us, bringing along with them their noxious prey in the very act of contending for victory. They move over the house with a good degree of order, ransacking one point after another, till, either having found something desirable, they collect upon it, when they may be destroyed en masse by hot water; or, disappointed, they abandon the premises as a barren spot, and seek some other more promising locality for exploration. When they are fairly in we give up the house, and try to await with patience their pleasure, thankful, indeed, if permitted to remain within the narrow limits of our beds or chairs. They are decidedly carnivorous in their propensities. Fresh meat of all kinds is their favorite food; fresh oils also they love, especially that of Elais guiniensis, either in the fruit or expressed. Under my observation they pass by milk, sugar and pastry of all kinds, also salt meat; the latter, when boiled, they have eaten, but not with the zest of fresh. It is an incorrect statement, often made, that they devour everything eatable by us in our houses; there are many articles which form an [Pg 39]exception. If a heap of rubbish comes within their route, they invariably explore it, when larvae and insects of all orders are borne off in triumph—especially the former.”

Sometimes, instead of camping in shelters on the ground, these ants climb up into a tree and hang together in a cluster like a swarm of bees. Savage reports a colony suspended from a low tree: “From the lower limbs (four feet high) were festoons or lines of the size of a man’s thumb, reaching to the plants and ground below, consisting entirely of these insects; others were ascending and descending upon them, thus holding free and ready communication with the lower and upper portions of this dense mass. One of these festoons I saw in the act of formation; it was a good way advanced when first observed: ant after ant coming down from above, extending their long limbs and opening wide their jaws, gradually lengthened out the living chain till it touched the broad leaf of a Canna coccinea below. It now swung to and fro in the wind, the terminal ant meanwhile endeavoring to attach it by his jaws and legs to the leaf; not succeeding, another ant of the same class (the very largest) was seen to ascend the plant, and, fixing his hind legs with the apex of the abdomen firmly to the leaf under the vibrating column, then reaching with his fore-legs and opening wide his jaws, closed in with his companion above, and thus completed the most curious ladder in the world.”

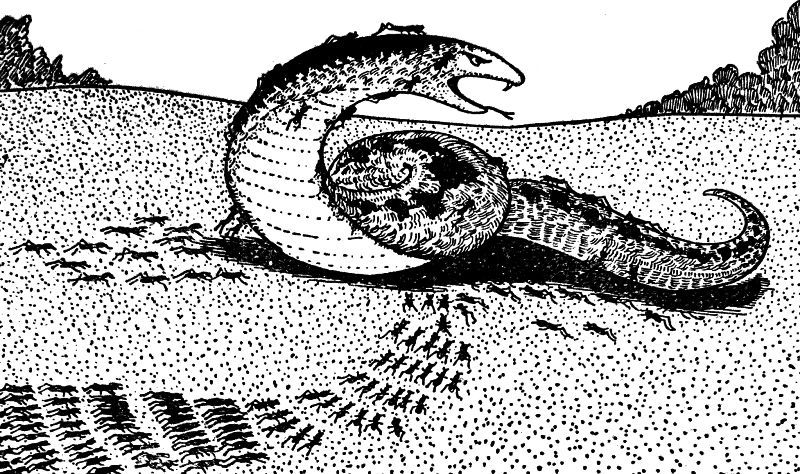

Similar chains are used in bridging little rills or even small brooks, but when a real [Pg 40]flood occurs a different procedure is adopted. In this case they cling together so as to form a large ball, with the eggs and young in the center, and float away upon the water until a safe landing can be effected.

There are several kinds of legionary and driver ants in America; some species have been found as far north as Texas and even Colorado, but most of them are confined to the tropics. These ants usually do not spend all of their time on the march, but have permanent nests, from which they sally out at intervals on foraging expeditions. Belt offers a graphic description of the sortie of a colony in Brazil: “One of the smaller species (Eciton praedator) used occasionally to visit our house, swarm over floors and walls, searching every cranny, and driving out the cockroaches and spiders, many of which were caught, pulled or bitten to pieces, and carried off.... I saw many large armies of this, or a closely allied species, in the forest. My attention was generally first called to them by the twittering of some small birds, belonging to several different species, that followed the ants in the woods. On approaching to ascertain the cause of the disturbance, a dense body of the ants, three or four yards wide, and so numerous as to blacken the ground, would be seen moving rapidly in one direction, examining every cranny, and underneath every fallen leaf. On the flanks, and in advance of the main body, smaller columns would be pushed out. These smaller columns would generally first flush the cockroaches, grasshoppers and spiders.[Pg 41]

Fig. V. Legionary ants attacking a snake.

The pursued [Pg 42]insects would rapidly make off, but many, in their confusion and terror, would bound right into the midst of the main body of ants.... The greatest catch of the ants was, however, when they got amongst some fallen brushwood. The cockroaches, spiders and other insects, instead of running right away, would ascend the fallen branches and remain there, whilst the host of ants were occupying all of the ground below. By and by up would come some of the ants, following every branch, and driving their prey before them to the ends of the small twigs, when nothing remained for them but to leap, and they would alight in the very midst of their foes, with the result of being certainly caught and pulled to pieces. Many of the spiders would escape by hanging suspended by a thread of silk from the branches, safe from the foes that swarmed both above and below.”

Some of the Brazilian species are more nomadic in their habits. Belt says: “I think Eciton hamata does not stay more than four or five days in one place. I have sometimes come across the migratory columns. They may easily be known by all the common workers moving in one direction, many of them carrying the larvae and pupae carefully in their jaws. Here and there one of the light-colored officers moves backwards and forwards directing the columns. Such a column is of enormous length, and contains many thousands, if not millions, of individuals. I have sometimes followed them up for two or three hundred yards without getting to the end.... [Pg 43]They make their temporary habitation in hollow trees, and sometimes underneath large fallen trunks that offer suitable hollows. A nest I came across in the latter situation was open at one side, and the ants were clustered together in a dense mass, like a great swarm of bees, hanging from the roof but reaching to the ground below. Their innumerable long legs looked like brown threads binding together the mass, which must have been at least a cubic yard in bulk, and contained hundreds of thousands of individuals, although many columns were outside, some bringing in the pupae of ants, others the legs and dissected bodies of insects. I was surprised to see in this living nest tubular passages leading down into the center of the mass, kept open just as if it had been formed of inorganic material. Down these holes the ants who were bringing the booty passed with their prey. I thrust a long stick down to the center of the cluster and brought out clinging to it many ants holding larvae and pupae, which were probably kept warm by the crowding together of the ants. Besides the common dark-colored workers and light-colored officers, I saw there many still larger individuals with enormous jaws. These they go about holding wide open in a threatening manner, and I found, contrary to my expectation, that they could give a severe bite with them, and that it was difficult to withdraw the jaws from the skin.”

Sumichrast, who studied some of the Mexican legionaries in 1863, noted many seemingly aimless migrations, “which they undertake at [Pg 44]undetermined epochs, but in relation, it appears to me, with the atmospheric changes. What traveler, passing over the tierra caliente, has not encountered the phalanxes of tepeguas upon the paths of the primitive forests? What inhabitant of these countries has not, at least once, been unpleasantly torn from the arms of sleep by the invasion of his domicile by a black army of soldados?... Besides the changes of domicile which are so generally in relation with the atmospheric variation as to serve as a rule to the inhabitants of the country, the Eciton devotes itself every season to excursions for pillage, destined to supply the larvae with nourishment. Nothing is more curious than these battues executed by an entire population. Over an extent of many square meters, the soil literally disappears under the agglomeration of their little black bodies. No apparent order reigns in the mass of the army, but behind this many lines or columns of laggards press on to rejoin it. The insects concealed under the dry leaves and the trunks of fallen trees fly on all sides before this phalanx of pitiless hunters, but, blinded by fright, they fall back among their persecutors and are seized and dispatched in the twinkling of an eye. Grasshoppers, in spite of the advantage given them by their power of leaping, hardly escape more easily. As soon as they are taken, the Eciton tears off the hinder feet and all resistance becomes useless.”

The same author describes with some feeling their habit of invading houses. “These visits ordinarily take place at the beginning of the [Pg 45]rainy season, and almost always during the night. The expeditionary army penetrates the habitation which it proposes to visit at many points at once, and for this purpose divides itself into many columns of attack. One is apprised very soon of their arrival by the household commotion among the parasitic animals. The rats, the spiders, the cockroaches, abandon their retreats and seek to escape from the attacks of the ants by flight. Alimentary substances the soldados hold in no esteem, and they disdain even sugary things, to which the ants in general are so partial. Dead insects even do not seem to invite their covetousness. It has often happened to me to be obliged to abandon my abode, without having time to carry away my collection, to which they have never done the least injury. The trouble occasioned by these insects in entering houses is more than compensated by the expeditious manner in which they purge them of vermin, and in this view their visit is an actual benefit.”

As these ants are usually quite blind and their movements are directed (so far as we can tell) by the sense of smell and contact alone, it is quite remarkable that they are able to move about so readily, and become familiar with their surroundings in less time than their seeing relatives. Forel wrote in 1899: “Throw a handful of Ecitons with their larvae on a spot with which they are absolutely unacquainted. In such circumstances other ants scatter about in disorder and require an hour or more to assemble and bring their brood together [Pg 46]and especially to become acquainted with their environment, but the Ecitons do this at once. In five minutes they have formed distinct files which no longer disintegrate. They carry their larvae and pupae, marching in a straight path, palpating the ground with their antennae and exploring all the holes and crevices till they find a suitable retreat and enter it with surprising order and promptitude. The workers follow one another as if at a word of command, and in a very short time all are in safety.”

The European ant known as Formica sanguinea is blood-red in color, and is one of the most industrious, versatile, and belligerent insects known to man. This species, according to Wheeler, “assails any intruder with its mandibles, simultaneously turning the tip of its gaster forward and injecting formic acid into the wound.”

Although sanguinea is widely known as a slave-holding species, it is by no means wholly dependent upon its slaves, but is quite able to dig its own nest, gather food and rear young without the aid of any slaves at all. “There is,” said Wheeler, “nothing to show that the slaves contribute anything more to the communal activities than would be contributed by an equal number of small sanguinea workers.” Many observers have reported slaveless colonies of sanguinea which seemed to be flourishing, and Wasmann found that the [Pg 47]youngest colonies contain, as a rule, more slaves than the older nests. He also reported an inverse ratio between the number of slaves and the size of the colony, some of the very largest being practically slaveless.

The slave-hunting expeditions of the sanguinea are said to occur only two or three times a year, and the general procedure is described by Wheeler as follows: “The army of workers usually starts out in the morning and returns in the afternoon, but this depends on the distance of the sanguinea nest from the nest to be plundered. Sometimes the slavemakers postpone their sorties till three or four o’clock in the afternoon. On rare occasions they may pillage two different colonies in succession before going home. The sanguinea army leaves its nest in a straggling, open phalanx sometimes a few meters broad and often in several companies or detachments. These move to the nest to be pillaged over the directest route permitted by the often numerous obstacles in their path. As the forefront of the army is not headed by one or a few workers that might serve as guides, but is continually changing, some dropping back while others move forward to take their places, it is not easy to understand how the whole body is able to go so directly to the nest of the slave species, especially when this nest is situated, as is often the case, at a distance of fifty or a hundred meters. We must suppose that the colony has acquired a knowledge of the precise location of the various nests of the slave species within an area of a hundred meters or more of its own nest. This knowledge [Pg 48]is probably acquired by scouts leaving the nest singly and from time to time for a period of several weeks, and these scouts must be sufficiently numerous to determine the movements of the whole worker body when it leaves the nest. This presupposes not only a high development of memory, but some form of communication, for the nest attacked is usually one of many lying in different directions from the sanguinea nest.

“When the first workers arrive at the nest to be pillaged, they do not enter at once, but surround it and wait for the other detachments to arrive. In the meantime the fusca or rufibarbis scent their approaching foes and either prepare to defend their nest or seize their young and try to break through the cordon of sanguinea and escape. They scramble up the grass-blades with their larvae and pupae in their jaws or make off on the ground. The sanguinary ants, however, intercept them, snatch away their charges, and begin to pour into the entrance of the nest. Soon they issue forth one by one with the remaining larvae and pupae and start for home. They turn and kill the workers of the slave-species only when these offer hostile resistance. The troop of cocoon-laden sanguinea straggle back to their nest, while the bereft ants slowly enter their pillaged formicary and take up the nurture of the few remaining young or await the appearance of future broods.

“Forel is of the opinion that many of the young brought home by the sanguinea are eaten, for the number of those which eventually hatch and become auxiliaries is very small [Pg 49]compared with the number pillaged during the course of the summer. Wasmann believes, however, that the forays take place for the specific purpose of obtaining young to rear. This seems to be disproved by the fact that even small sanguinea colonies are quite able to get along without slaves and by the insignificant number of these individuals in many nests. Darwin has interpreted the surviving and adopted workers as a kind of by-product, or as representing food which the ants failed to eat at the proper time, and such they would appear to be in the adult colony, though, as we shall see, they have an additional significance as the result of an instinct inherited by the sanguinea workers from their queen. That the foray is, to some extent at least, due to the promptings of hunger, seems to be shown by the fact that sanguinea sometimes plunders the nests of ants which it could not adopt as slaves.”

Wasmann describes the military expeditions of the so-called sanguine slavemakers (F. sanguinea), which generally hunt in companies of from twenty to fifty workers, “with the purpose not only of stealing the neuter pupae of the slave species, but often also of pillaging the nests of smaller ants belonging to the genus Lasius, the larvae, pupae and winged individuals of which are carried off to be devoured. During the time of the nuptial flight of Lasius niger, many sanguinea colonies are hunting in the vicinity of their nest for the heavy Lasius females which drop to the ground. Then either singly or with united forces these robbers pull their victims into their strongholds, where [Pg 50]they are mercilessly slaughtered. On the afternoon of August 24, 1888, I witnessed such a typical hunting expedition of several sanguinea colonies near Exaten, Holland, on the outskirts of a fir plantation. The road passing the nests was covered far and wide with sanguineas rushing upon every Lasius female that dropped from the air, as upon a welcome booty. Within the space of an hour I counted more than one hundred females of Lasius niger that fell victims to the hunters.”

There are several species and sub-species of sanguinea in the United States, and the habits of these differ in several particulars from those of their European relatives. Wheeler reports that although he has found plenty of slaveless colonies, most nests contain slaves in much greater number than do similar colonies in Europe. He thinks this due in part to the fact that the American species make more frequent raids, and partly also because the species chosen as slaves are “much more cowardly and docile” than the victims of the slave-hunters of the Old World. The actual tactics employed in the raids do not differ essentially from those of the European species.

It was long supposed that new colonies of the sanguinea were founded in this wise: When the queen descends from her nuptial flight she either brings up a brood of her own like many common ants, or she is adopted into a nest of one of the slave species. On either of these suppositions it is difficult to explain how the slave-making instincts could be transmitted to the workers, because the latter have no offspring and the queen was supposed to [Pg 51]lack the slaving instincts. In 1906, Wheeler cleared the matter up by introducing a sanguinea queen into a nest containing workers, larvae, and cocoons of one of the slave species. She was immediately attacked, but beat off her assailants, killed a number of them, and captured a large number of cocoons, which she carried into a separate chamber and defended against all comers. Here she waited until the workers emerged from the captured cocoons; these workers, of course, attached themselves to her and soon gained possession of the whole nest. This experiment shows clearly that the sanguinea queen really possesses all the slave-making tendencies exhibited by the workers in their raiding, and solves the problem of the inheritance of these instincts.

Another type of slave-owning ants is represented by the genus Polyergus, found in both Europe and North America, and known as amazons. Slavery among the amazons is a very different thing from the casual master-servant relationship found in the various species of sanguinary ants. The sanguinea are quite able to build nests, gather food, and rear their young unaided by slave labor, and slaveless colonies are not at all uncommon, but the amazons are absolutely dependent upon their slaves, and no amazon colony could exist without them. As Wheeler says, the amazons “are even incapable of obtaining their own food, although they may lap up water or liquid food [Pg 52]when this happens to come in contact with their short tongues. For the essentials of food, lodging and education they are wholly dependent on the slaves hatched from worker cocoons that they have pillaged from alien colonies. Apart from these slaves they are quite unable to live, and hence are always found in mixed colonies inhabiting nests whose architecture throughout is that of the slave species. Thus the amazons display two contrasting sets of instincts. While in the home they sit about in stolid idleness or pass the long hours begging the slaves for food or cleaning themselves and burnishing their ruddy armor, but when outside the nest on one of their predatory expeditions they display a dazzling courage and capacity for concerted action compared with which the raids of sanguinea resemble the clumsy efforts of a lot of untrained militia. The amazons may, therefore, be said to represent a more specialized and perfected stage of dulosis than that of the sanguinary ants. In attaining to this stage, however, they have become irrevocably dependent and parasitic.”

The same author describes a slave-hunting foray of the European species. “The ants leave the nest very suddenly and assemble about the entrance if they are not, as sometimes happens, pulled back and restrained by their slaves. Then they move out in a compact column with feverish haste, sometimes, according to Forel, at the rate of a meter in 33 seconds, or 3 cm. per second. On reaching the nest to be pillaged, they do not hesitate like sanguinea but pour into it at once in a body, seize the brood, [Pg 53]rush out again and make for home. When attacked by the slave species they pierce the heads or thoraces of their opponents and often kill them in considerable numbers. The return to the nest with the booty is usually made more leisurely and in less serried ranks. The observer of one of these forays cannot fail to be impressed with the marvelous precision of its execution. Although the ants may occasionally lose their way and have to retrace their steps or start off in a different direction, they usually make straight for the nest to be plundered. They must, therefore, like sanguinea, possess a keen sense and memory of locality. There can be little doubt that they often leave the nest singly and make a careful reconnoissance of the slave colonies in the vicinity.”

One can hardly believe that as soon as the fighting is over these warriors relapse into their accustomed lethargy, and are fed and cared for by their slaves, who often prevent them from leaving the nest, and sometimes, when they have wandered away, pick them up bodily and carry them home by main strength. When a colony moves to a new home the whole enterprise is left to the slaves, who choose and prepare the new nesting site, and carry the warriors to it. In the case of the sanguinea it will be remembered that it is the masters who carry the slaves on these occasions.

An American amazon which has been the subject of considerable study is Polyergus breviceps, found in the mountainous regions of Colorado and New Mexico. This species is [Pg 54]very striking in appearance, the worker and queen being of a rich purplish-red color, while the male is jet-black with white wings. A peculiar feature of the breviceps’ raiding parties is that there are no casualties on either side. The slave species offer no real resistance, and the amazons simply put them gently to one side, take their larvae and pupae, and go their way.

We do not know exactly how new amazon colonies are established. Forel, Wasmann and Viehmeyer have agreed that the queen lacks the domestic instinct, and therefore the new colony must be founded by the slave species, which cares for the amazon females. It has been shown that the adoption occurs readily enough in artificial nests. Some experiments by Wheeler gave rather conflicting results, and he closes his discussion of the matter by saying: “It will be necessary, therefore, to study this question further before making definite statements in regard to the method employed by our American amazons in establishing colonies.”

The peculiar symbiotic relations between ants and aphids is worth a brief description. The aphids or plant-lice live in colonies upon certain plants, and feed upon juices which they suck from the foliage. The liquid excrement of these insects is sweet, and a surprisingly large amount is voided—Bŭsgen found that the [Pg 55]maple aphid produces as many as forty-eight drops in twenty-four hours. This substance is sometimes so abundant that it covers the leaves and even drips down to the ground; it is known as honeydew, and some rustics still believe that it somehow falls from heaven. The ants are very fond of this honeydew, and some species live upon it almost exclusively at certain seasons, and locate their nests always near good aphid-pastures. The ants never kill and eat aphids as they do other insects, but protect them against their enemies. They even carry them about from one pasture to another, and some species build little sheds and corrals in which their aphids are confined just as we confine cattle. Sometimes the ants simply lap up the honeydew as it falls upon the leaves, but in most cases they milk the aphids by gently stroking them with the antennae, which causes the emission of a drop of the sweet liquid. Some kinds of aphids have developed a circle of stiff hairs around the anal opening, which thus retains the honeydew till the ant comes for it. Not only do the ants care for and milk the adult aphids, but they rear them from the eggs. Huber, Lubbock and others have seen ants collecting aphid eggs in the Autumn, and it has been found that these eggs are stored in the nest until they hatch, when the young plant-lice are carried out and placed on a suitable food-plant. On cold or rainy days they are taken back into the nest; when the weather moderates the ants carry them out to pasture again.

The scale-insects and mealy-bugs (Coccidae) [Pg 56]also produce honeydew, and are visited by the ants precisely as the aphids are. The manna of the Biblical story, according to Wheeler, “is now known to be the honeydew of one of these insects (Gossyparia mannifera) which lives on the tamarisk. This excretion is still called man by the Arabs who use it as food.” Forel, Cockerell and Wheeler have seen ants tending great herds of coccids, and a few of these insects are found in many nests.

Several kinds of tree-hoppers bear a similar relation to ants. Bare, who studied these matters in Argentina, “watched the larvae of various species of Centrotus being assiduously attended by ants. The larvae are gregarious, frequenting the succulent shoots of plants, and have an extensile organ at the extremity of the body, from which the coveted fluid is emitted.” Wheeler observed whole colonies of ants herding leaf-hoppers in Colorado, and reports that these novel milk-cows “responded to the antennal caresses of the ants in precisely the same manner as the plant-lice and scale-insects.” Some ants confine their tree-hoppers in sheds and shelters similar to those used for the aphids.

The relationship of ants to certain small caterpillars (the larvae of some of the Lycaenid butterflies) has been known for a long time. These little caterpillars, when caressed on the posterior end by the antennae of the ants, give up a drop of sweet liquid, doubtless very similar to that produced by the aphids and coccids.[Pg 57]

These larvae are often found in the ants’ nests, and some of the newly emerged [Pg 58]butterflies have been seen to come out of the ant-hills. It is said that the ants protect the caterpillars from the attacks of hymenopterous parasites, and De Niceville is authority for the statement that the butterfly will not lay her eggs when there are no ants about: “If the right plant has no ants, or the ants on that plant are not the right species, the butterfly will lay no eggs on that plant. Some larvae will certainly not live without the ants, and many larvae are extremely uncomfortable when brought up away from their hosts or masters.”

Besides the ants’ relationship with the insects which produce sweet substances, there are symbiotic relations of a very different type with a group of insects known as myrmecophiles—ant-guests. These insects, at one stage or another, live in the ant-hills. At least fifteen hundred species of ant-guests are known, and Escherich estimates that there must be at least three thousand altogether. Wheeler thinks that even this estimate is probably too low. At least a thousand of the known species are beetles, and most of the rest are insects of one kind or another, but there are about sixty arachnids and a few crustaceans.

Some of the myrmecophiles are not friends of ants as the name implies, but mere interlopers—scavengers, robbers and assassins. There are a number of small beetles which live in the less frequented galleries of the nest, eat dead ants and brood, kill ailing or crippled ants, and even attack healthy adults when they catch them alone or at some disadvantage. Some of these beetles resemble ants in general [Pg 59]appearance, a mimicry which is doubtless of considerable value to them. The ants kill these pests whenever they can, but many are protected by their ability to emit an evil-smelling substance which puts the ants to flight. Others will be killed at once if confined in a small chamber with a few ants, but in a large nest are able to escape by reason of their agility.

Another class of myrmecophiles, known as synoeketes, or tolerated guests, live in the ant-hills without attracting any great attention, being treated with contemptuous indifference by their hosts. The larvae of certain moths and flies, a large number of beetles, and numerous other insects are of this class, and feed largely upon the refuse of the kitchen-middens. Wasmann has studied a group of beetles which live with the nomadic Doryline ants. These camp-followers mimic the legionaries, and march along in their columns apparently unnoticed, being allowed to share the prey taken by the blind warriors. Other beetles live in the nests of the sanguinea, and feed largely upon the tiny parasites from the bodies of their hosts. Certain minute wingless crickets are very abundant in many nests; they are seen to lick the bodies of the ants, and it is supposed that they live upon some cutaneous secretion.

The insect called Attaphila is a sort of miniature cockroach, which lives with the fungus growing Attii, and is, according to Wheeler, the only insect known to be on intimate terms with these ants. A peculiar thing about the Attaphila is that the last joint of the antennae [Pg 60]is nearly always bitten off. This insect was formerly supposed to feed on fungus, but has since been found to lick the surface secretions from the ants’ bodies. A little beetle called Oxysoma oberthueri is very like Attaphila in its habits, “mounting the bodies of its host and licking or shampooing them with great eagerness.”

Very different from the furtive, barely tolerated myrmecophiles described above are the three or four hundred species known as true guests, which, to quote Wheeler again, “are no longer content to be treated with animosity or indifference, but have acquired more intimate and even friendly relations with the ants. These true guests are not, therefore, to be found skulking in the unfrequented galleries of the nest, or suspiciously dodging about among the ants, but live in their very midst with an air of calm assurance, if not of proprietorship.” Among these are many beetles bearing tufts of hair which produce some aromatic secretion very pleasing to the ants. The ants rush to lick the odorous tufts, are caressed by the peculiar antennae of the beetle, and feed the latter with regurgitated food. Many of these beetles are cleaned and shampooed by the ants, are often carried about, and favored in other ways, despite the fact that they sometimes devour the ant brood. Some of the smaller species are totally blind, and are permitted to ride about on the ants’ backs for hours at a time.

Fig. VII. Showing two minute myrmecophilous beetles (Oxysoma oberthueri) feeding on the surface secretions of an ant. (Adapted from Escherich).

Another sort of guest is the little mite called Antennophorus, which Janet has found in the [Pg 62]nests of several European ants. These mites attach themselves firmly to the body of their host, and it is interesting to note that no matter how many are present on a single ant, they are always so placed that the weight is properly distributed, and the host’s progress not interfered with. These creatures remind one of the ticks found on higher animals like dogs, but they are not parasites in the sense that ticks are—they do not suck the ant’s blood, but reach out and snatch their nutriment from the drops of regurgitated food as they pass from one ant to another.