Title: A dictionary of the art of printing

Author: William Savage

Release date: December 6, 2025 [eBook #77410]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1841

Credits: Louise Hope, John Campbell, Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Books project.)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Basic fractions are displayed as ½ ⅓ ¼ etc; other fractions are shown in the form a-b/c, for example 5/2 or 8-3/7.

Breves and macrons are accurately represented (ă ĕ ā ē etc). Many other unusual characters are displayed using Unicode combining diacriticals.

The old long s character ſ is used exactly as in the original text.

The latin ligatures ff fi fl ffi ffl are displayed as one Unicode character. However older ligatures are displayed as separate characters; these include ct, st, ſt, ſh, ſi, ſl, ſb, ſk, ſſ, fſ, ſſi.

Footnotes are indicated by * † ‡ or § as in the original text, and have not been moved from their position in the printed text. Thirteen other footnote anchors are denoted by [number], as in the original text, and those footnotes have also been left in place at the end of their table or text section.

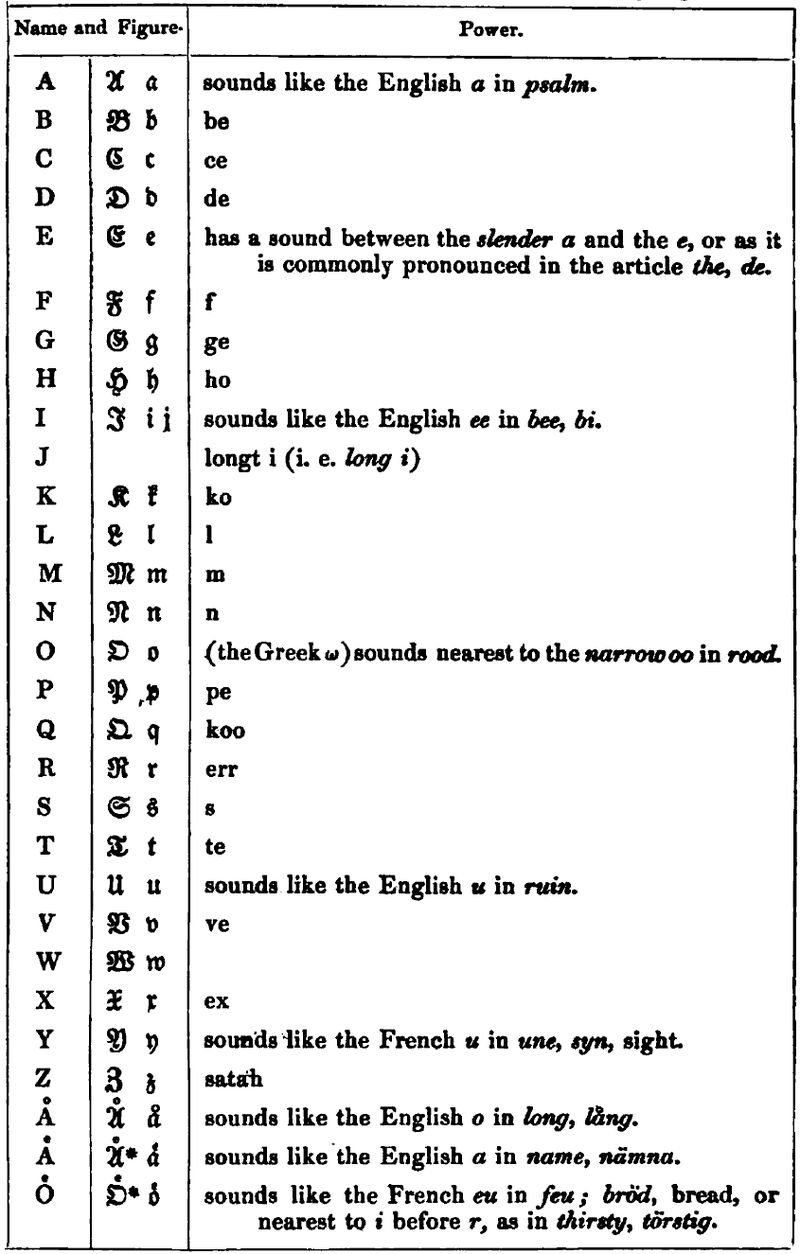

The ALPHABET and BLACK LETTER sections will display the Gothic characters if any of these fonts are installed: Blackletter, Fraktur, Textur, "Olde English Mt", "Olde English", Diploma, England, Gothic. The DANISH, GERMAN and SWEDISH sections also have these Gothic characters.

The IRISH section will display the Irish characters (insular script) if any of these fonts are installed: KellsFLF, Ring of Kerry, MeathFLF.

The Rabbinical Hebrew characters, used extensively on p315-317, can be displayed if the Rashi font "Noto Rashi Hebrew" or "Noto Rashi Hebrew Regular" is installed. Otherwise regular Hebrew characters will be displayed.

This book uses characters from many different alphabets. Unicode

codepoints are used whenever possible, but some printed characters

have no codepoint. These are represented in this etext by [#] for a

single character or dipthong and by [###] for a word or phrase.

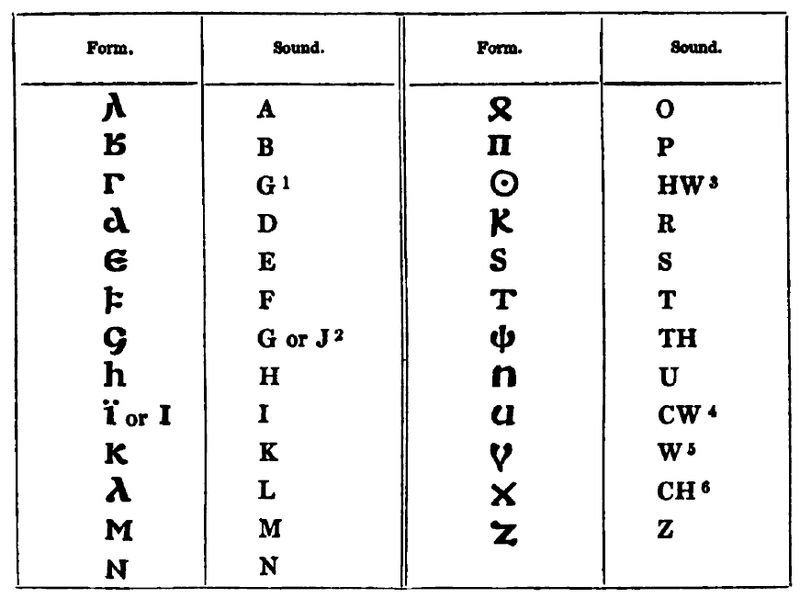

The Etruscan, Maeso-Gothic and Swash alphabets are displayed as an image only

since no codepoints exist for their characters at this time.

Some characters with valid codepoints may not display properly on some handheld devices. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols.

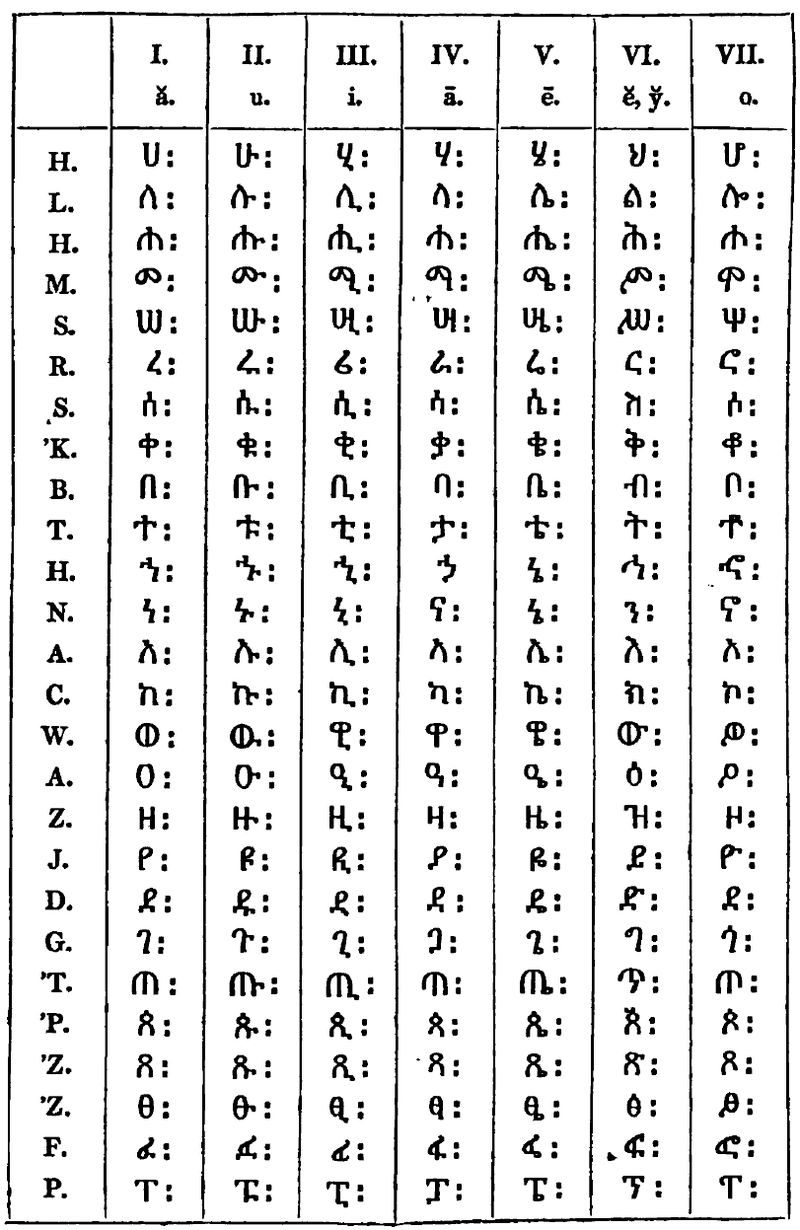

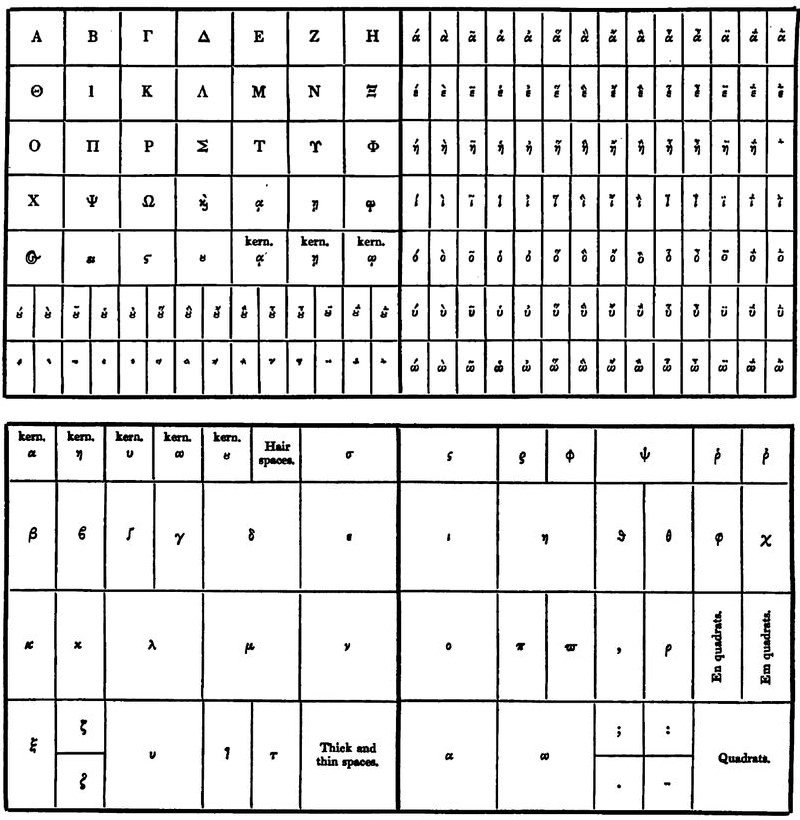

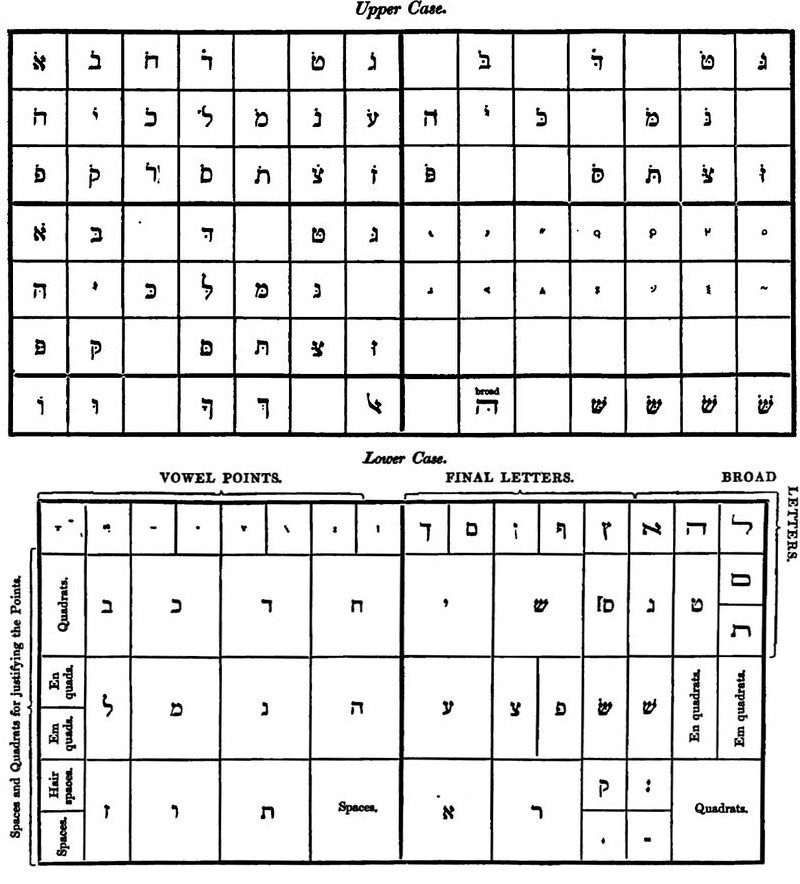

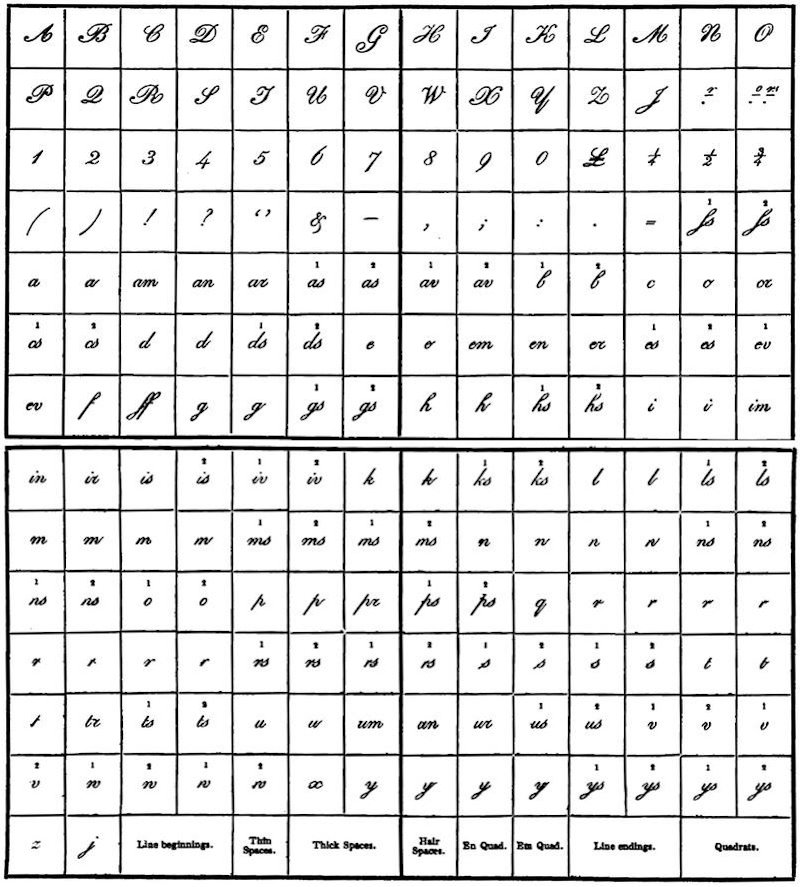

All the Alphabet tables are displayed as an Illustration in browsers and ereaders, as well as a text table.

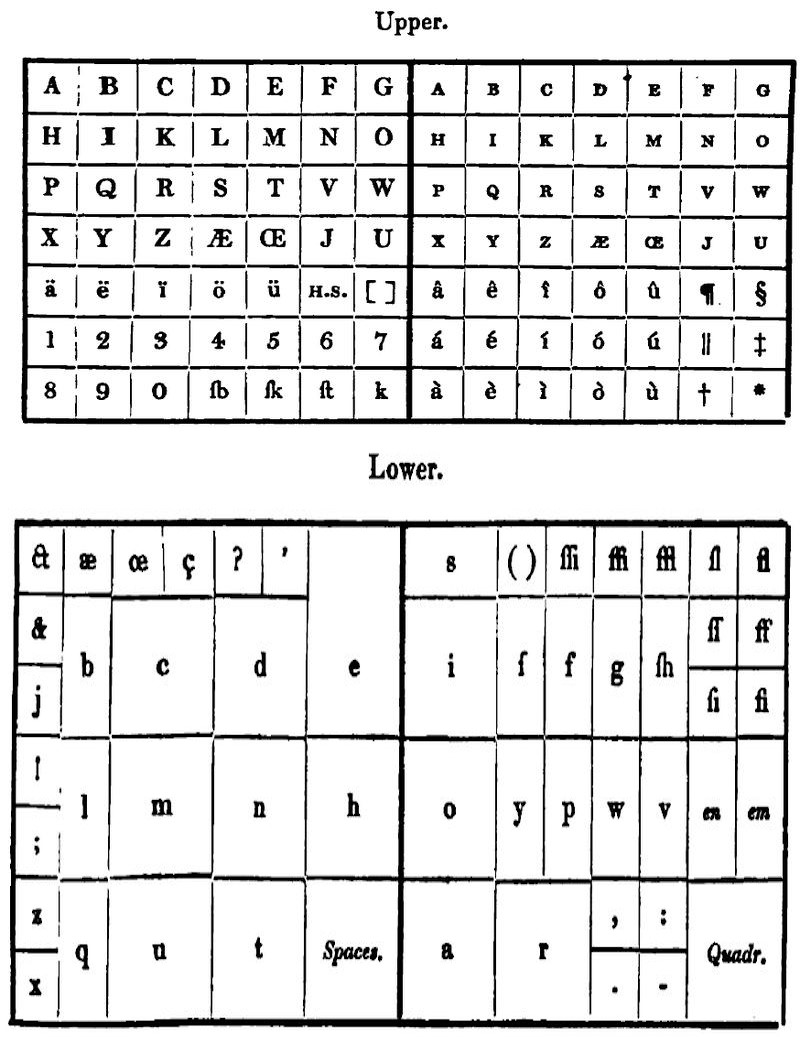

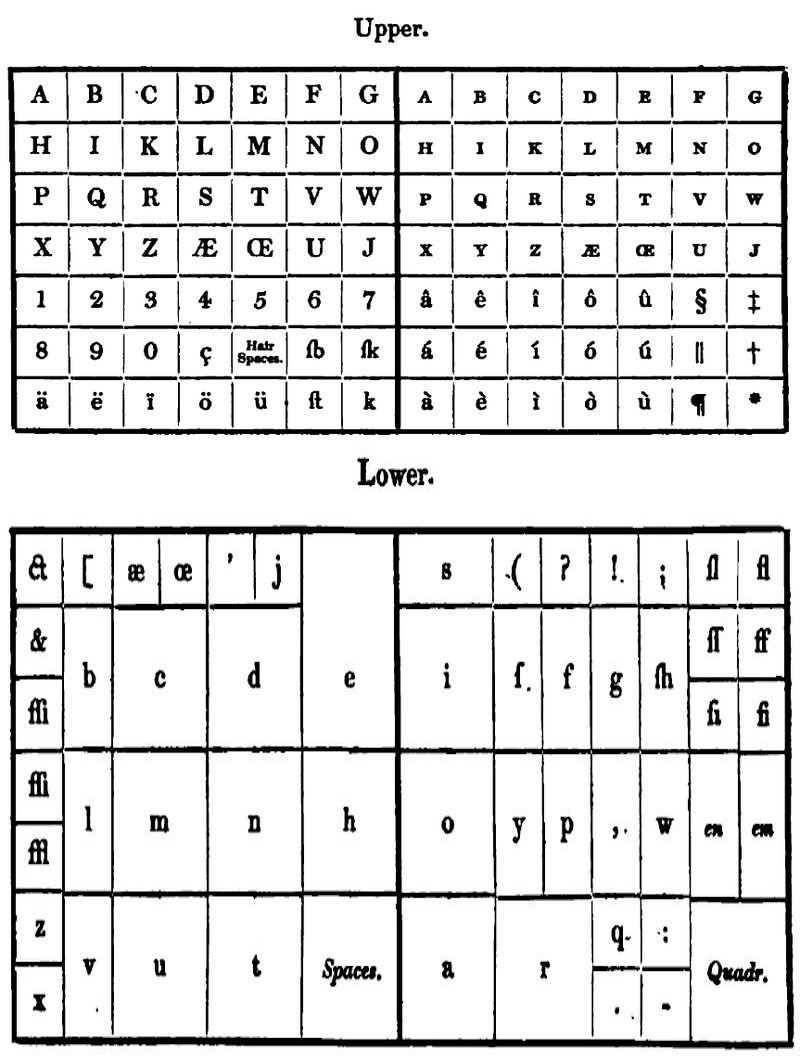

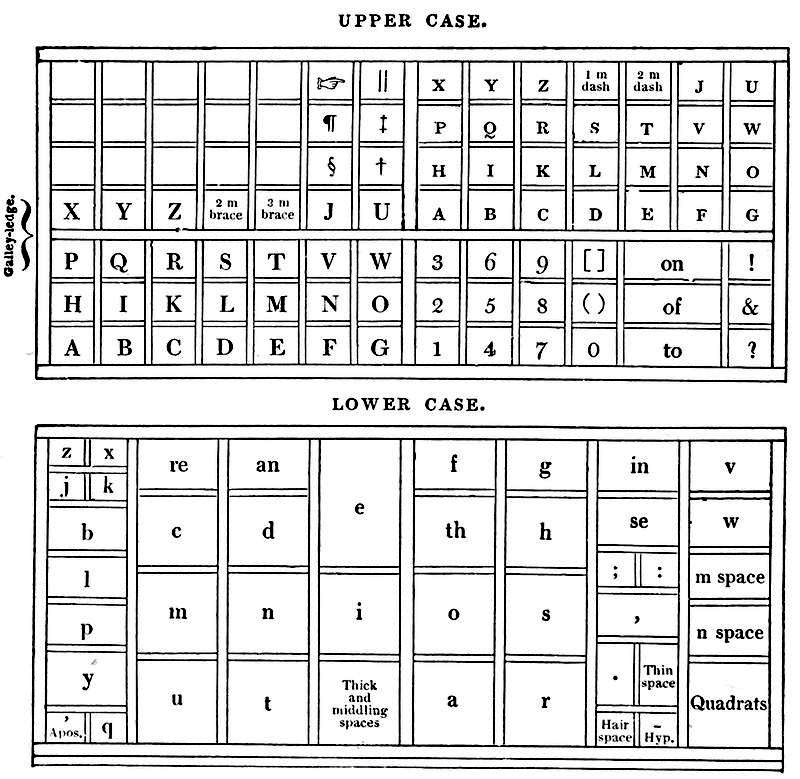

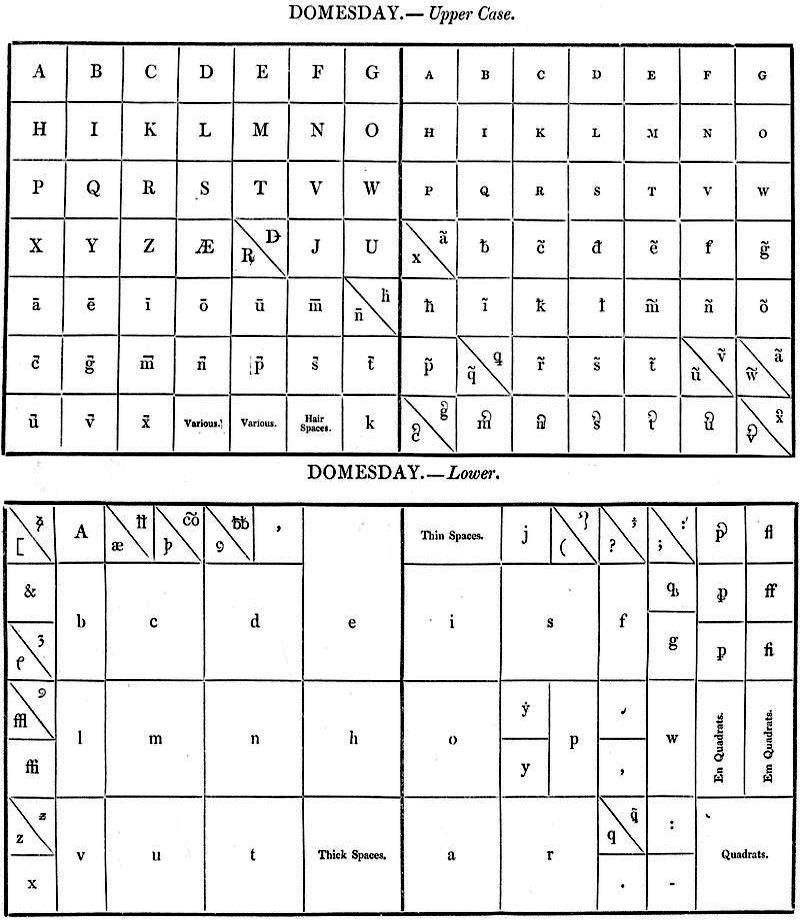

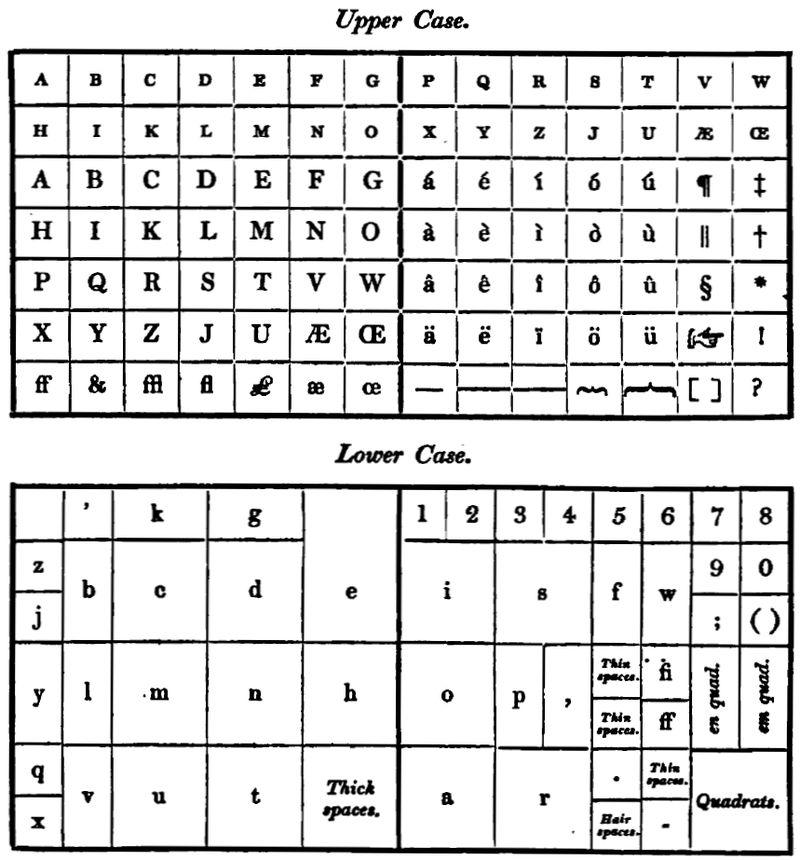

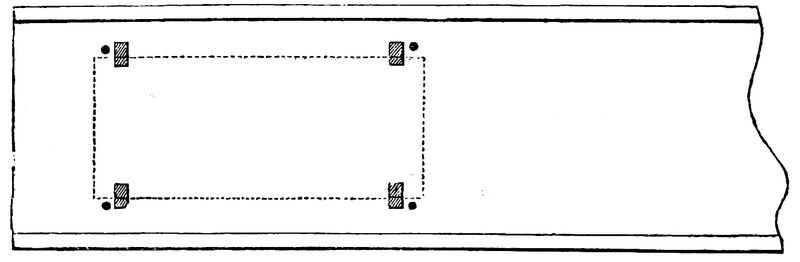

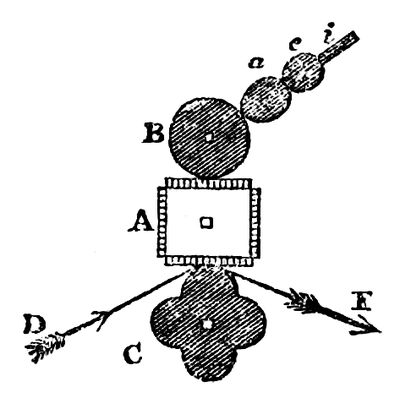

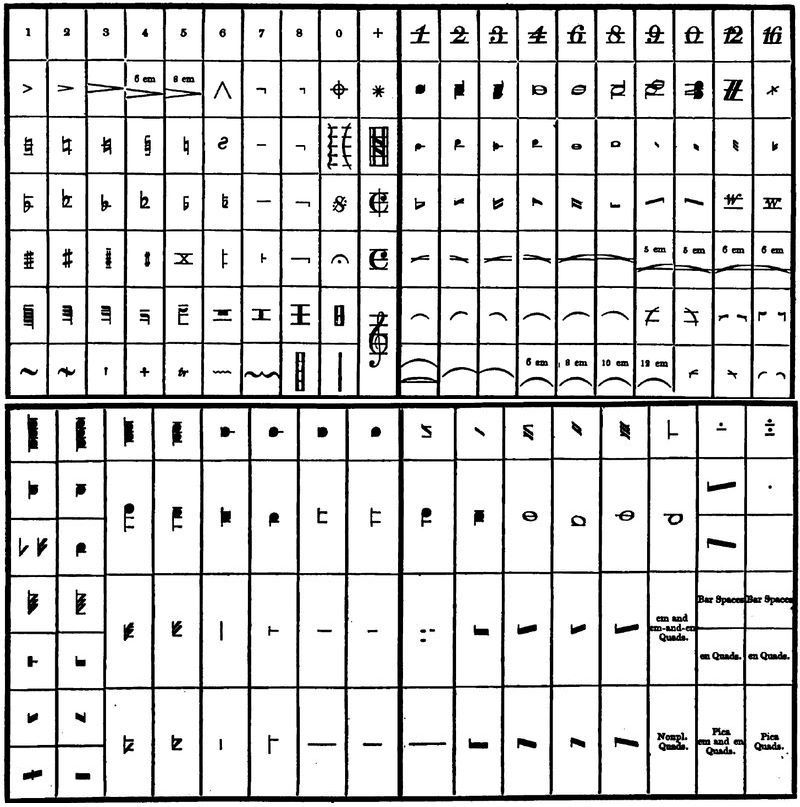

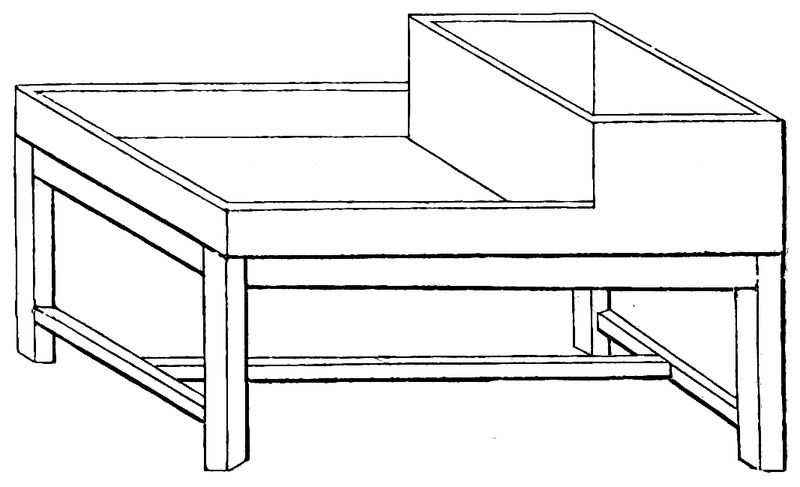

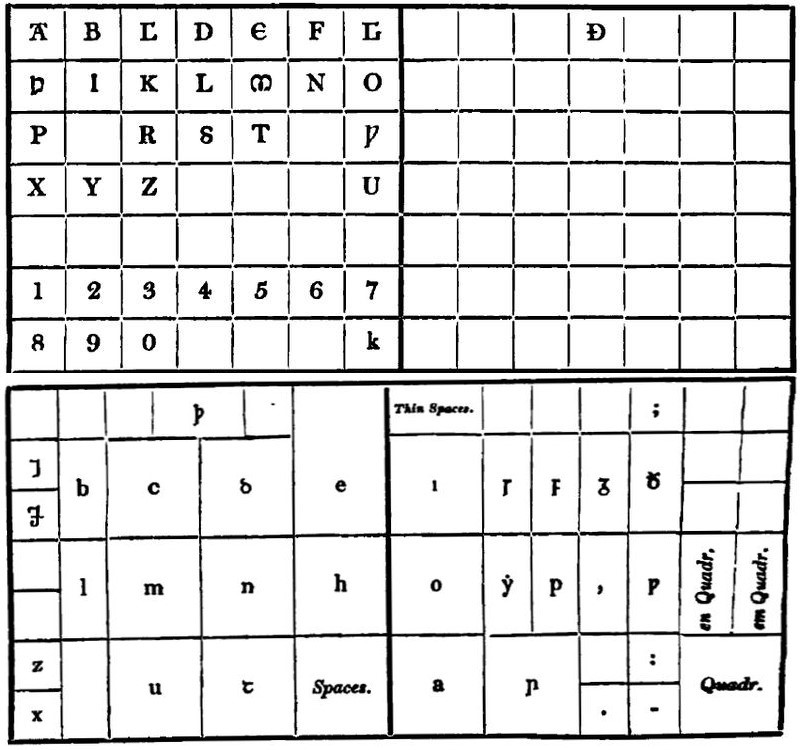

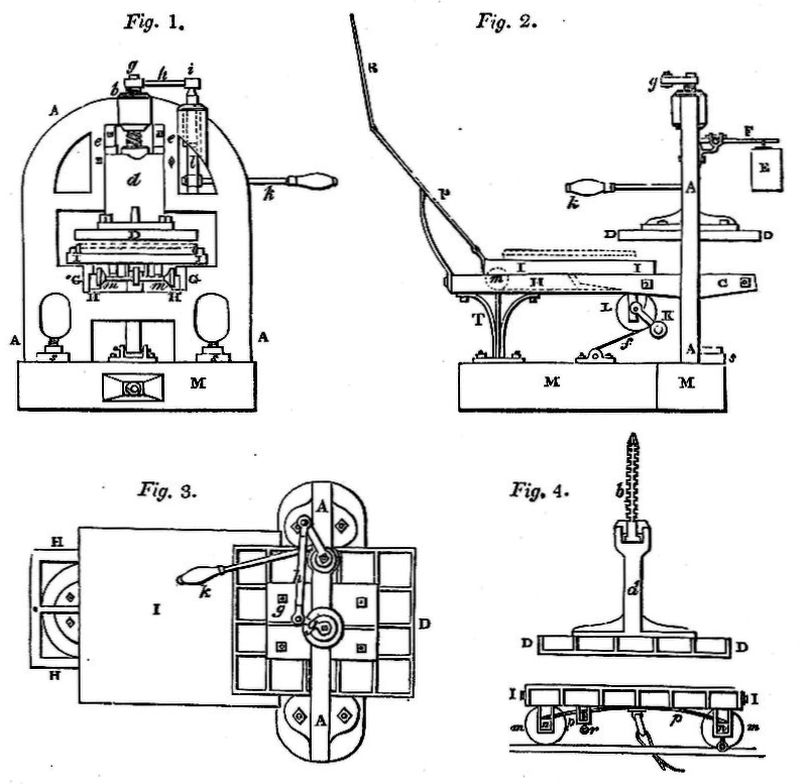

Case diagrams, showing the Upper case and Lower case layout used by compositors for a particular font, are displayed only with an Illustration.

Tables on p104 to p161 show the count of letters on a sheet. The first page of 6 tables is shown in an Illustration. Only the table header and the first row of its data are displayed. The printed book had over three hundred of these tables on fifty-eight pages.

Tables on p273 to p292. The first JOBS table is displayed in full. Only the table header and the first row of data is displayed in all subsequent tables. The printed book had twenty pages of these tables.

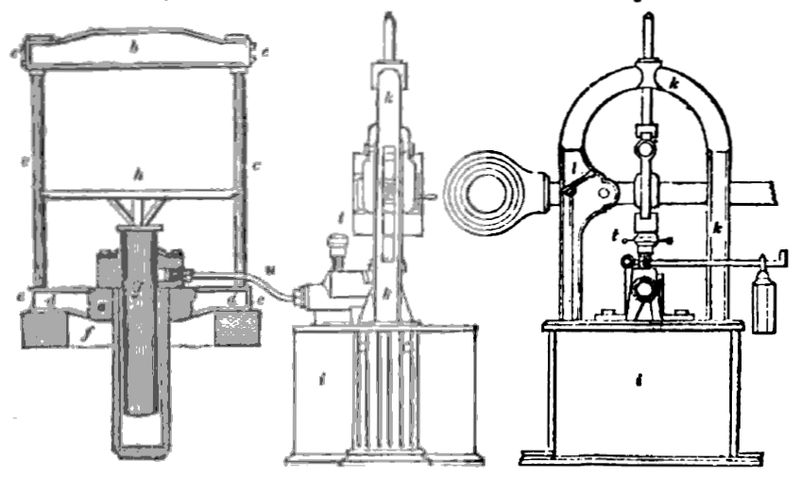

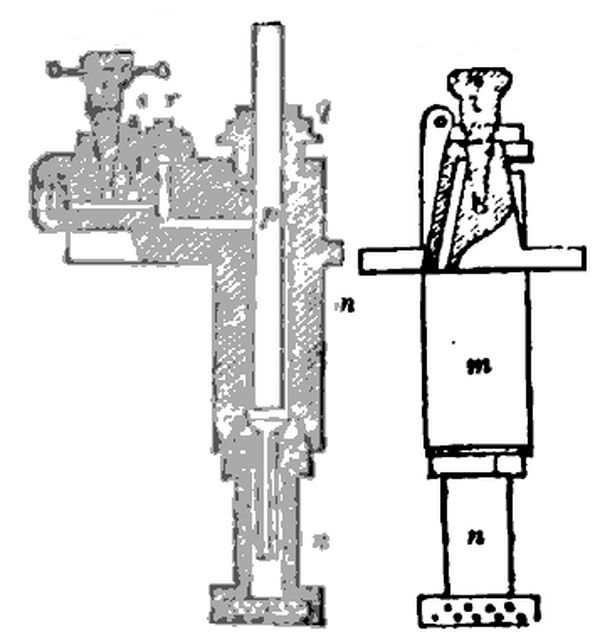

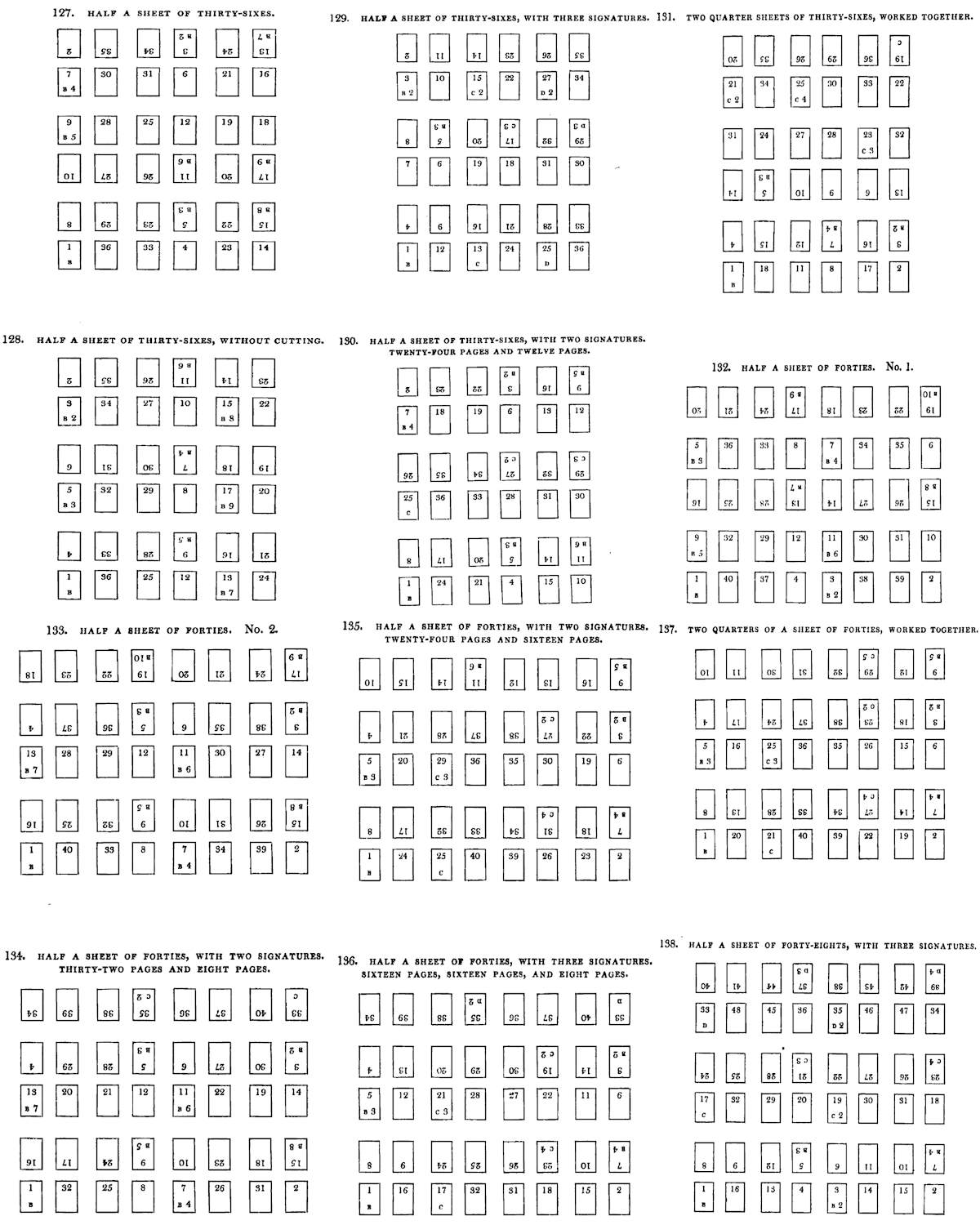

Tables of Imposition on p335 to p400. The first three pages are displayed as searchable tables, the remaining sixty-three pages are displayed as small Illustrations. Many of the numerical signatures on a page were printed upside down in the original book. This is indicated in this etext (on those first three pages of tables) by putting the number in brackets, for example [14] or [B2].

Tables on p598 to p643. Only the table header and the first row of its data are displayed. The first page of 5 tables is shown in an Illustration. The printed book had over one hundred of these tables on forty-six pages.

Tables of signatures on p761 to p773. These tables are displayed in full.

The citation M. refers to Joseph Moxon, a 17th-century English printer.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Some other minor text changes are noted at the end of the book.

London:

Printed by A. Spottiswoode,

New-Street-Square.

A

DICTIONARY

OF

THE ART OF PRINTING.

BY WILLIAM SAVAGE,

AUTHOR OF

“PRACTICAL HINTS ON DECORATIVE PRINTING,”

AND OF A TREATISE

“ON THE PREPARATION OF PRINTING INK, BOTH BLACK AND COLOURED.”

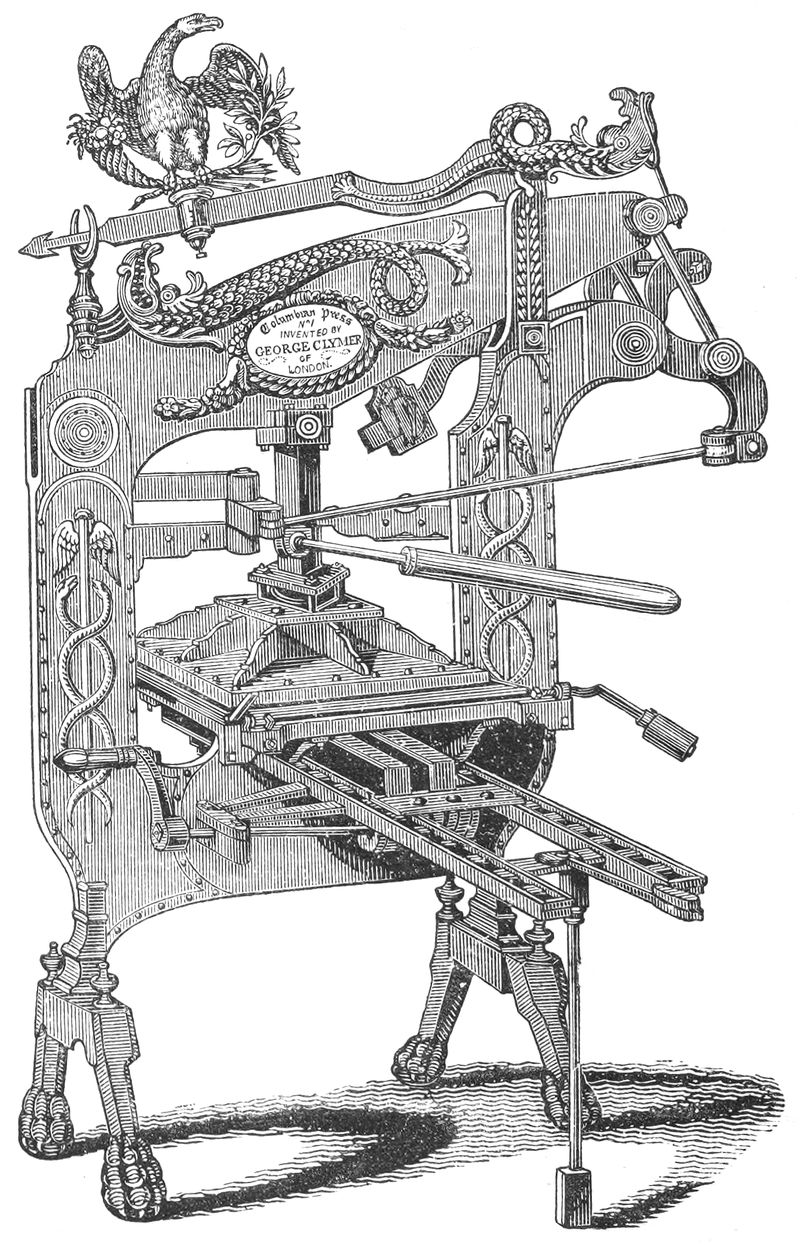

LONDON:

LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, AND LONGMANS.

1841.

Books of this class, themselves series of explanations, require fewer prefatory remarks than those of any other; yet I cannot allow the present work to go before the public without availing myself of this privilege of authors. It affords me an opportunity of acknowledging, which I do most gratefully, the kind and valuable assistance I have received during my protracted labours, and of saying a few words on the History of Printing, the limits of the book, the style of writing adopted, and on the introduction of subjects that at a first glance may appear to have but little or no connexion with the art.

I am indebted to Mr. Fehon, of Mr. Bentley’s establishment, Bangor House, Shoe Lane, for the valuable article on Records, who is, perhaps, more competent than any other printer in the kingdom for such an undertaking; and also for his judicious opinions during the progress of the work. Mr. Murray kindly prepared the specimens of electrotype by his improved method, for which method he received a premium from the Society of Arts. To Mr. Knight I am obliged for permission to copy the list of botanical terms from his Encyclopædia. From the letter founderies of Mr. Caslon, of Messrs. Figgins, and of Messrs. Thorowgood and Besley, I have obtained the various alphabets, &c., and am happy to acknowledge the courteous manner in which these and other kindnesses were granted. To other friends who feel an interest in the work, and have rendered me their services, I beg to tender my sincere thanks. The books quoted are each mentioned with every quotation, therefore there will be no necessity to recapitulate them here; I may, however, state, that they are the works of standard authors, as it has been my endeavour to refer to the opinions of men whose talents and learning are generally acknowledged, rather than to opinions perhaps more pertinent in works but little known.

The origin of the art is involved in obscurity, there being no clue by which it can be traced, yet it is doubtless of very early date: some authors maintain that printing was practised during the building of Babylon. It is not my intention, however, to enter upon this inquiry here, as it is probable, if my health continue, that I shall embody the facts and information I have been so long collecting on this subject in another work. The dates given of the introduction of the practice into Europe by previous writers are unquestionably erroneous, as we have conclusive evidence of its being followed as a profession for nearly a century before the earliest date they give. There has, in reality, hitherto been but little said on the History or Practice of Printing, the numerous[vi] books on the subject being chiefly copies from one or two of the earliest writers. The object in the present undertaking was that of making a purely practical work: one that might meet every exigence of the printer whilst in the exercise of his art, and one that would serve as a book of reference to the author, the librarian, and, in fact, to every one interested in books or their production.

It will be observed that Moxon’s book has been frequently referred to, and in many instances quoted from. This I was induced to do in consequence of the quantity of useful matter it contains, and more especially in order to point out and contrast the then method of printing with the present. (Where the letter M is used it refers to this author.) The intermediate stages, where improvements or alterations have occurred, are also noticed; so that the practical history of the art is complete from the year 1683, when Moxon published, to the present time.

The Statutes at Large I have carefully gone through from their commencement; all the acts of parliament that in any way refer to printing, and unrepealed, I have introduced: so that the Printer has here all the Statute Law in existence for his guidance in conducting his business.

The List of Abbreviations will be found extensive, and, I trust, valuable, as until now there has been no printed list of many of them. The interpretations have been obtained by comparing the writings of contemporary authors, and by consulting those of my friends who have made the early writers their study.

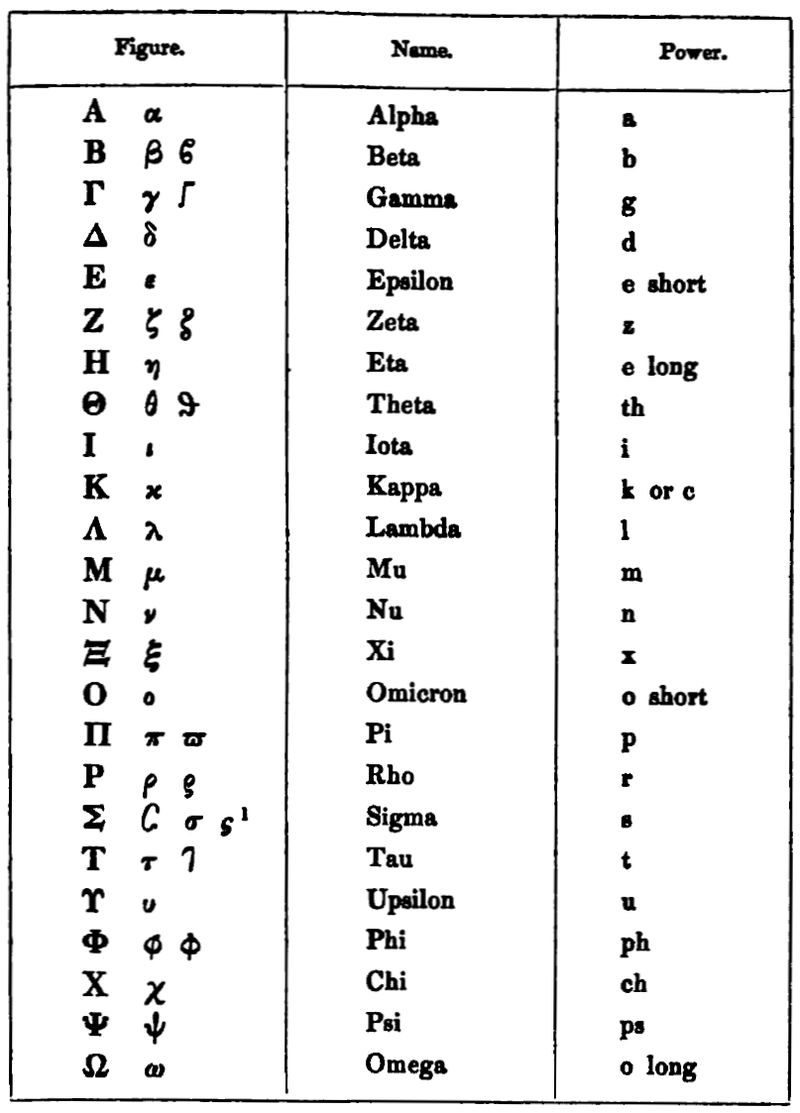

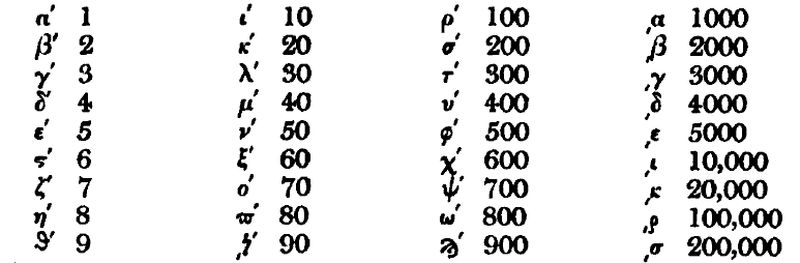

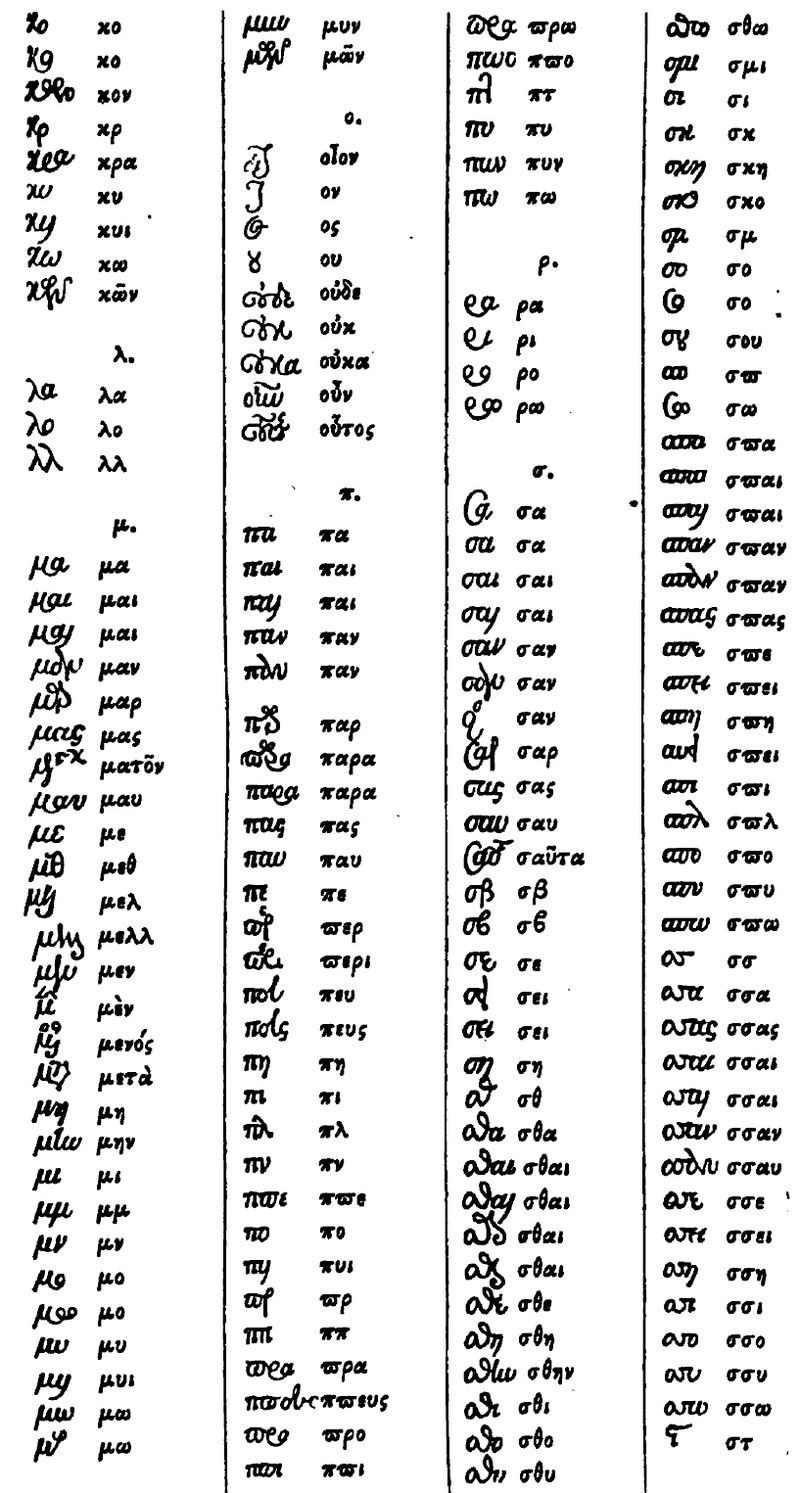

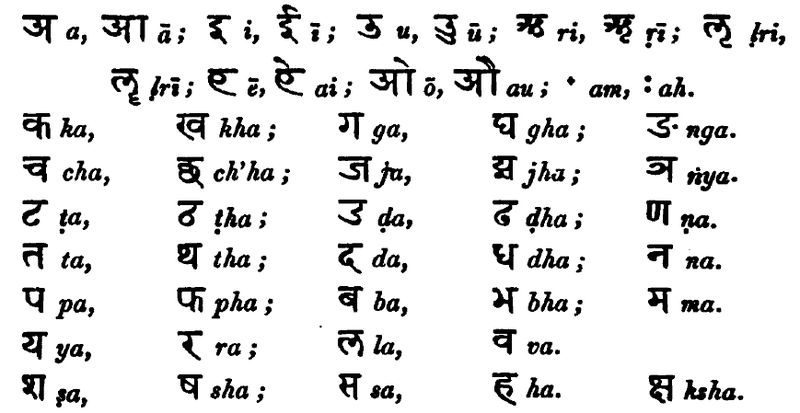

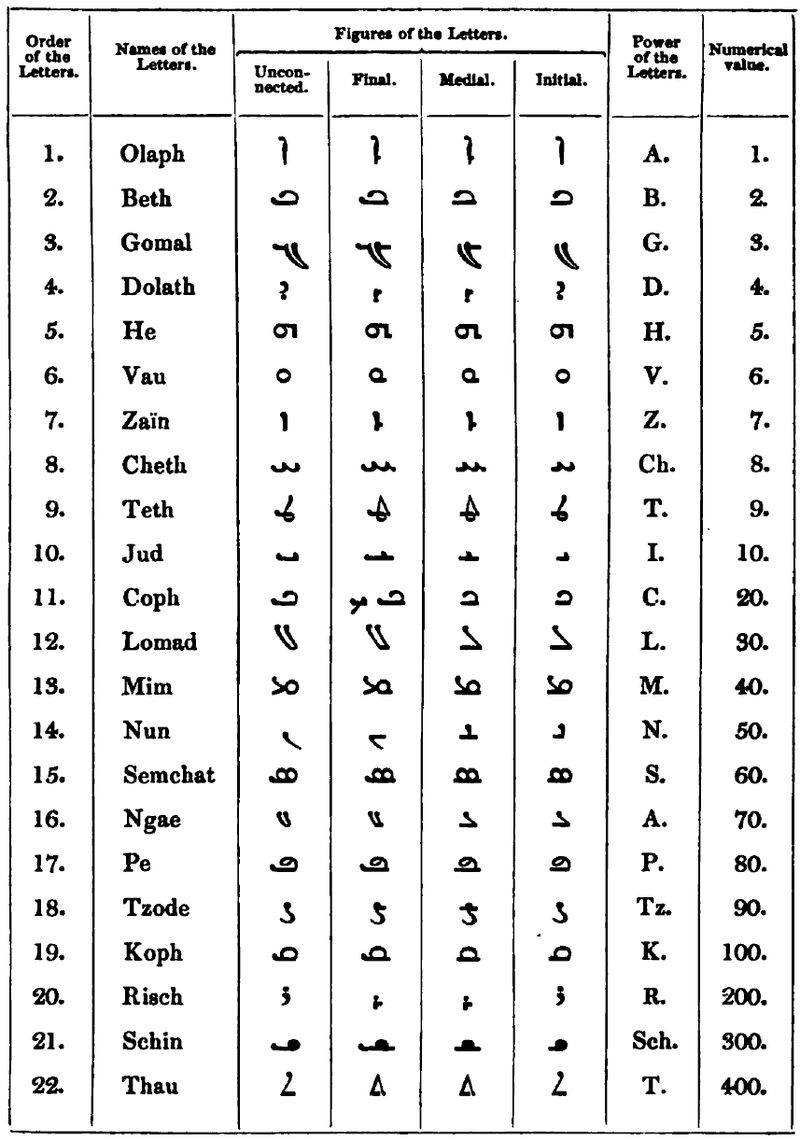

All the alphabets are taken from the best grammars in each language, in preference to the more easy, but less correct method, of copying the letters from any indifferent book printed in the characters of the respective languages. I have confined myself to those languages of which the characters are in the British founderies.

Whether my views are right or wrong respecting the orthography, punctuation, and the capital letters of the Bible, rests with the public to determine. I cannot consent to give an opinion in favour of the changes that fashion, prejudice, or even the rules of grammar have introduced, which are now adopted in general writing, until we have another authorized version of the Bible, but think the more literally we copy the present the better, otherwise the discrepancies will soon be notorious.

The article on Imposing is of considerable length; yet I could not, in justice to the work, curtail it: the tables might even have been still more numerous, and yet serviceable, had the limits of the book permitted; as it is, they are much more extensive than any tables hitherto published. Men from the country having been but little used to book-work, find themselves at a loss on entering a town-house in this part of their business.

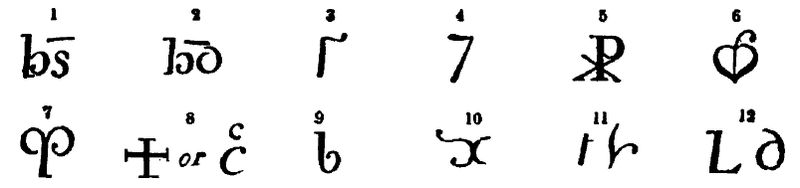

In printing topographical works, copies of early acts of parliament, state papers of the middle ages, or books published soon after the introduction of printing, when there were no general rules for either writing or spelling, the list of characters and abbreviations under the head of[vii] Records will be found invaluable. My kind friend Mr. Fehon has spent many years of his life in investigating this subject, and has here condensed most of what will be valuable to the Printer.

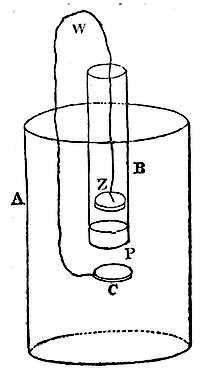

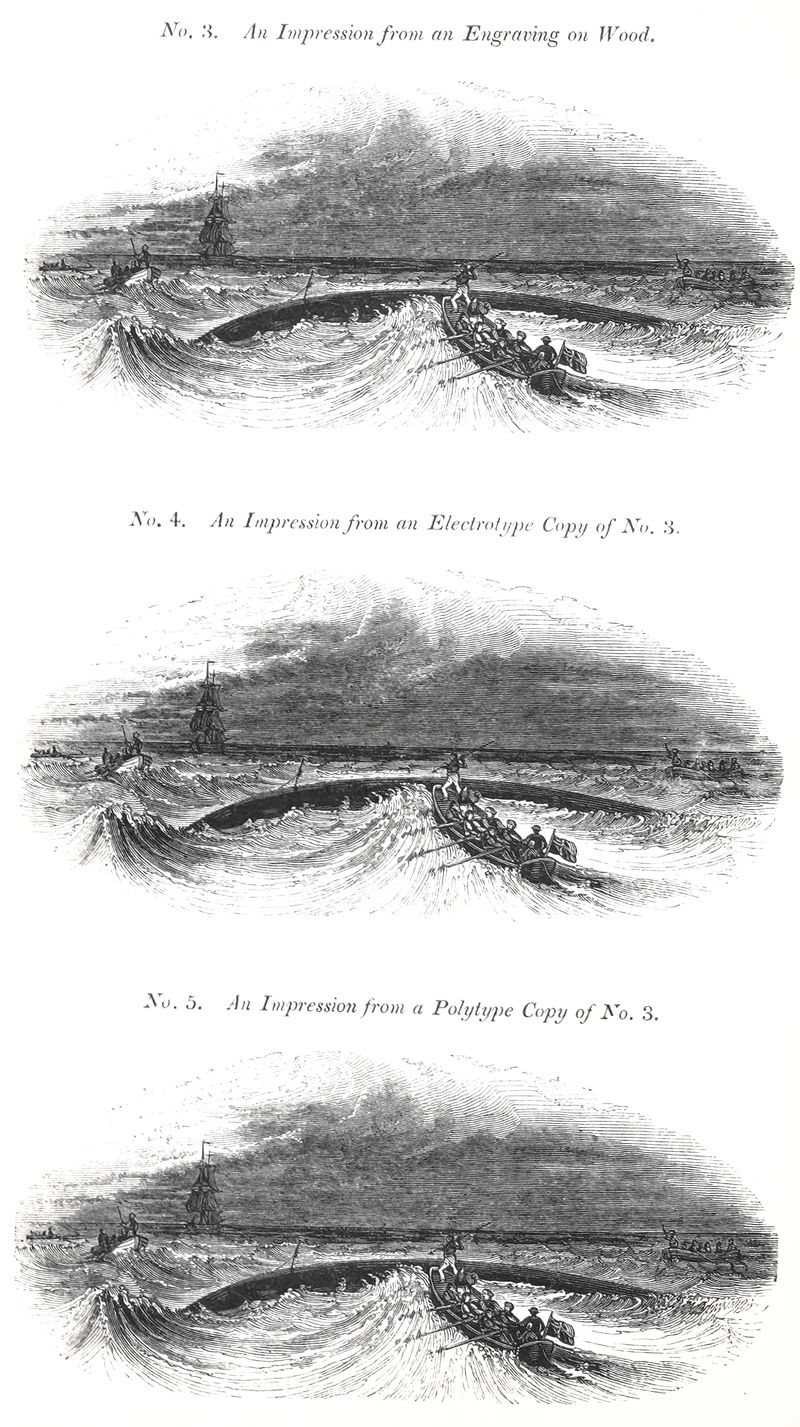

Electrotype, although quite in its infancy, promises to be of great utility in the arts, and not the least so in that of printing. I have therefore thought it right to give some account of it, together with specimens, amongst which will be found an electrotype copy of a page of types: it is imperfect, but I believe it is the first that has been published.

No detailed account of the process of producing fine presswork has before appeared. This circumstance I cannot otherwise explain than by supposing it to arise from the jealous feeling that exists in the bosoms of many of those who are masters of the practice. On speaking to them of the value a detailed statement would be, I have been told that there were already a sufficiency of men who knew it, and that there was no necessity to deprive them of their advantages. Having paid particular attention to this department, and having produced works of this character that have been highly applauded, I have given a detailed account of all the minutiæ of so valuable a branch of the business.

Printing from engravings on wood is also a subject that has particularly interested me, the practice of which I have given at length: the result of my experience confirms the opinion that the press is infinitely superior to the machine for this description of work.

Having prepared the bulk of the matter prior to going to press, I thought it might be safely stated that the whole would be comprised in fourteen numbers. Yet, on revising, I found that some important articles had not been touched upon, and that others perfectly new (electrotype, &c.) had sprung up during the progress of printing; so that either the book must have been left incomplete (had the first arrangement been adhered to), or three more numbers must be added, and thus every branch that pertained to the practice be embraced. I trust none will regret that the latter plan has been adopted. With regard to the style of writing—I am now an old man, and perhaps may be, in some degree, wedded to the writings as well as the customs of my youth; therefore the quaintness of expression, which my friends have noticed, may possibly be more marked than I am aware of; yet the manner is not wholly unintentional. To some persons simple language may not have the attractions that are presented by the writings of many authors of the present day, whose chief study is elegance of expression; but do we not, by adopting this flowery style, lose in clearness, in strength, in conciseness? Yes, and, I think, even in beauty; and when it is considered that it was the intention to make the book one of practical instruction, and that it was written with the hope that it might be placed in the hands of each printer’s boy on entering the business, I trust this sin of inelegance may be pardoned. No one but the compiler of a dictionary can conceive the unwearied labour that is requisite for its completion. Having possessed greater opportunities than most men for the present undertaking, yet have I been upwards of half a century in collecting the materials; not, perhaps, having entertained the idea of publishing[viii] during the whole of this period, still never neglecting to amass every species of information that might be made available. On going over such an extent of ground much has been culled that would either never have been known to me, or, if known, would have been forgotten, had the book been more hastily got up; and all those subjects, a knowledge of which, at first, may appear irrelevant or useless, will in practice be found highly necessary, there having been no dictionary or book of reference kept in the printing offices to which the workmen could apply. Should the work prove less useful than I could wish it, the fault is in myself, and not in the subject; but if on its perusal the young be instructed, the knowledge of the more mature workman be refreshed and confirmed, and the general reader find its utility as a book of reference, then have I nothing to regret, but much to be grateful for. Lord Bacon says, “Every man is a debtor to his profession, from the which, as men do of course seek to receive countenance and profit, so ought they of duty to endeavour themselves by way of amends to be a help thereunto.”

DICTIONARY

OF THE

ART OF PRINTING.

“ABBREVIATIONS

are characters, or else marks on letters, to signify either a word or syllable. & is the character for and, ye is the abbreviated, yt is that abbreviated; and several other such. Straight strokes over any of the vowels abbreviate m or n. They have been much used by printers in old times, to shorten or get in matter; but now are wholly left off as obsolete.”—Moxon. In reprints of old books, where the original is closely followed, we occasionally meet with ɋ as an abbreviation of que: this mark of contraction for ue was attached to the q, and was originally used solely for that purpose; for the convenience of using the q without it, the abbreviation was afterwards cast separate, and by degrees it was adopted as a point or stop to divide a sentence, becoming the semicolon, the next in order to the comma.

Some few authors yet retain the ; after a q, for the termination ue, which appears to be the proper mark.

Abbreviations “occur very frequently, and are often the occasion of perplexity to readers less familiarly acquainted with them, in the early-printed books. These also originated from the idea which the first Printers entertained of making their books as much as possible resemble manuscripts. That they should perpetually occur in manuscripts is natural enough; for the librarii, or writers of manuscripts, necessarily had recourse to them to shorten their labours. These abbreviations, in the infancy of Printing, were perhaps to be excused; but it seems they multiplied to so preposterous an extent that it was found necessary to publish a book, both in the Gothic and Roman character, to explain their meaning.”—Beloe’s Anecdotes of Literature, &c. See Domesday Book. Records. Sigla.

A.—Aulus.

A. B.—Artium Baccalaureus. Bachelor of Arts.

Abp.—Archbishop.

A. C.—Ante Christum. Before the Birth of Christ.

A. C.—Arch-Chancellor.

A. D.—Anno Domini. In the Year of our Lord.

A. D.—Ante Diem.

A. D.—Arch-Duke.

Adm.—Admiralty.

Adm. Co.—Admiralty Court.

A. H.—The Year of the Hegira.

A. M.—Artium Magister. Master of Arts.

A. M.—Anno Mundi. In the Year of the World.

A. M.—Ante Meridiem. Before Noon.

An. A. C.—Anno ante Christum. In the Year before Christ.

Ana.—Of each a like Quantity.

Anon.—Anonymous.

A. P. G.—Professor of Astronomy in Gresham College.

A. R.—Anno Regni. In the Year of the Reign.

A. R. R.—Anno Regni Regis. In the Year of the Reign of the King.

Ast. P. G.—Astronomy Professor in Gresham College.

A. T.—Arch-Treasurer.

A. U. C.—Ab Urbe condita. From the building of the City.

Aug.—Augustus.

B. et L. D.—Duke of Brunswick and Lüneburg.

B. A.—Artium Baccalaureus. Bachelor of Arts.

Bart.—Baronet.

B. C.—Before Christ.

B. C. L.—Bachelor of Civil Law.

B. D.—Baccalaureus Divinitatis. Bachelor of Divinity.

B. M.—Baccalaureus Medicinæ. Bachelor of Medicine.

Bp.—Bishop.

B. R.—Banco Regis. The King’s Bench.

Brit. Mus.—British Museum.

Bt.—Baronet.

B. V.—Blessed Virgin.

B. V.—Bene Vale. Farewell.

C.—Caius.

c.—Caput. Chapter.

Cæs. Aug.—Cæsar Augustus.

Cal.—Calendis. The first Day of the Month.

Cal. Rot. Pat.—Calendarium Rotulorum Patentium. Calendar of the Patent Rolls.

Cap.—Capitulum. Chapter.

C. B.—Companion of the Bath.

C. C.—Caius College.

C. C. C.—Corpus Christi College.

ca. sa.—Capias ad satisfaciendum.

cf.—Confer. Compare.

Chart. Max.—Large Paper.

Cic.—Cicero.

Civ.—Civitas.

C. J. C.—Caius Julius Cæsar.

Cl.—Clarus. The celebrated.

Cl.—Claudius.

Cl. Dom. Com.—Clerk of the House of Commons.

Clk.—Clerk, a Clergyman.

Cn.—Cneius.

Coh.—Cohors.

Col.—Collega, Collegium.

C. O. S. S.—Consulibus. To the Consuls, or, From the Consuls, or, By the Consuls, Being Consuls, or, During the Consulate.

C. P.—Common Pleas.

C. P. S.—Custos Privati Sigilli. Keeper of the Privy Seal.

C. R.—Custos Rotulorum. Keeper of the Rolls.

C. R.—Civis Romanus.

Cr.—Creditor.

C. S.—Custos Sigilli. Keeper of the Seal.

D.—Decimus.

D. B.; Domesd. B.—Domesday Book.

D. C.—Dean of Christ Church.

10ber.—December.

D. C. L.—Doctor of Civil Law.

D. D.—Divinitatis Doctor. Doctor in Divinity.

D. D.—Dono dedit. Gave as a Present.

D. D. D.—Dat, Dicat, Dedicat. He gives, he devotes, he makes sure, or, consecrates.

D. F.—Dean of Faculty (Scotland).

D. G.—Deo gratias. Thanks to God.

D. G.—Dei gratiâ. By the Grace of God.

Dict.—Dictator.

D. M. S.—Diis Manibus Sacrum. Sacred to the Gods of the dead.

Dn.—Dominus.

Do.—Ditto. The same.

D. O. M.—Deo Optimo Maximo. To God the best, the greatest.

Dr.—Doctor.

Dr.—Debtor.

E.—East.

Eccl.—Ecclesiastes.

Ecclus.—Ecclesiasticus.

e. g.—Exempli gratiâ. As for example.

e. g.—Ex grege. Among the rest (literally from the Flock).

Ep.—Epistola.

Eps.—Episcopus.

Erg.—Ergo.

Esq.—Esquire.

Et.—Etiam.

Eur.—Europa.

Exch.—Exchequer.

Exon. D.—Exeter Domesday Book.

Exor.—Executor.

Ex S. C.—Ex Senatûs consulto.

Ex V.—Ex Voto.

F. D.—Fidei Defensor. Defender of the Faith.

F. E. S.—Fellow of the Entomological Society.

F. G. S.—Fellow of the Geological Society.

F. H. S.—Fellow of the Horticultural Society.

Fi. B.—Fide bonâ.

Fid.—Fides.

fi. fa.—Fieri facias.

Fil.—Filius.

F. L. S.—Fraternitatis Linneanæ Socius. Fellow of the Linnean Society.

Fœd. N. E.—Rymer’s Fœdera, New Edition.

F. R. S.—Fraternitatis Regiæ Socius. Fellow of the Royal Society.

F. R. S. E.—Fellow of the Royal Society, Edinburgh.

F. R. S. L.—Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

F. S. A. E.—Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, Edinburgh.

G. C. B.—Grand Cross of the Bath.

G. C. H.—Grand Cross of the Royal Hanoverian Guelphic Order.

G. R.—Georgius Rex. George the King.

h. e.—Hoc est. That is, or, this is.

Heb.—Hebrews.

Hel.—Helvetia.

Hhd.—Hogshead.

Hier.—Hierusalem. Jerusalem.

H. J. S.—Hic jacet sepultus. Here lies buried.

H. M.—His or Her Majesty.

H. M. P.—Hoc Monumentum posuit. Erected this Monument.

H. M. S.—His or Her Majesty’s Ship.

H. R. I. P.—Hîc requiescit in Pace. Here rests in Peace.

H. S.—Sestertius. Two-pence.

Id.—Idem. The same.

Id. E.—Idem est.

i. e.—Id est. That is.

Ig.—Igitur.

I. H. S.—Jesus Hominum Salvator. Jesus the Saviour of Man.

Imp.—Imperator. Emperor.

Impp.—Imperatores, viz. de duobus.

Imppp.—Imperatores, viz. de tribus.

Incog.—Incognito. Unknown.

Inq. p. m.—Inquisitio post Mortem.

I. N. R. I.—Jesus Nazarenus, Rex Judæorum. Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.

Ins.—Instant. Of this Month.

J. C.—Juris consultus.

J. C.—Julius Cæsar.

J. D.—Jurum Doctor. Doctor of Laws.

Jul.—Julius.

Jun.—Junius.

J. V. D.—Juris utriusque Doctor. Doctor of Canon and Civil Law.

K. Aug.—Kalendæ Augusti.

K. A. N.—Knight of Alexander Newski, Russia.

K. B.—Knight of the Bath.

K. B.—King’s Bench.

K. B. E.—Knight of the Black Eagle of Prussia.

K. C.—Knight of the Crescent of Turkey.

K. C.—King’s Counsel.

K. C. B.—Knight Commander of the Bath.

K. C. H.—Knight Commander of the Royal Hanoverian Guelphic Order.

K. C. S.—Knight of Charles III. of Spain.

K. G.—Knight of the Garter.

K. G. F.—Knight of the Golden Fleece, of Spain, or of Austria.

K. G. H.—Knight of Guelph of Hanover.

K. G. V.—Knight of Gustavus Vasa of Sweden.

K. H.—Knight of the Royal Hanoverian Guelphic Order.

K. L. A.—Knight of Leopold of Austria.

K. L. H.—Knight of the Legion of Honour.

K. M.—Knight of Malta.

K. Mess.—King’s Messenger.

K. M. T.—Knight of Maria Theresa of Austria.

K. N. S.—Knight of the Royal North Star of Sweden.

Knt.—Knight.

K. P.—Knight of Saint Patrick.

K. R. E.—Knight of the Red Eagle of Prussia.

K. S.—Knight of the Sword of Sweden.

K. S. A.—Knight of St. Anne of Russia.

K. S. E.—Knight of St. Esprit (or Holy Ghost) of France.

K. S. F.—Knight of St. Fernando of Spain.

K. S. F. M.—Knight of St. Ferdinand and Merit of Naples.

K. S. G.—Knight of St. George of Russia.

K. S. H.—Knight of St. Hubert of Bavaria.

K. S. J.—Knight of St. Januarius of Naples.

K. S. L.—Knight of the Sun and Lion of Persia.

K. S. M. & S. G.—Knight of St. Michael and St. George of the Ionian Islands.

K. S. P.—Knight of St. Stanislaus of Poland.

K. S. S.—Knight of the Southern Star of the Brazils.

K. S. W.—Knight of St. Wladimir of Russia.

K. T.—Knight of the Thistle.

K. T. S.—Knight of the Tower and Sword of Portugal.

K. W.—Knight of William of the Netherlands.

L.—Lucius.

lb.—Libra. A Pound.

Ldp.—Lordship.

Leg.—Legatus. Lieutenant-General.

Leg.—Legio. Legion.

Lev.—Leviticus.

Lib.—Liber. Book.

Lieut.—Lieutenant.

LL. B.—Legum Baccalaureus. Bachelor of Laws.

LL. D.—Legum Doctor. Doctor of the Canon and Civil Law.

LL. S.—Sestertius. Two-pence.

L. N. E. S.—Ladies Negro Education Society.

L. P.—Large Paper.

Lp.—Lordship.

Lre.—[French] Lettre. Letter.

L. S.—Loco Sigilli. Place of the Seal.

L. s. d.—[French] Livres, Sous, Deniers. Pounds, Shillings, Pence.

M.—Manipulus. An Handful.

M.—Marcus.

M.—Monsieur.

M. A.—Master of Arts.

M. B.—Medicinæ Baccalaureus. Bachelor in Medicine.

M. B.—Musicæ Baccalaureus. Bachelor of Music.

M. D.—Medicinæ Doctor. Doctor of Medicine.

Mens.—Mensis. Month.

Messrs.—Messieurs. [French, the plural of Monsieur.] Gentlemen; Sirs.

Mil.—Miles. A Soldier.

Mil.—Mille. A Thousand.

M. M. S.—Moravian Missionary Society.

Monsr.—Monsieur.

M. P.—Member of Parliament.

Mr.—Mister.

M. R. A. S.—Member of the Royal Asiatic Society.

M. R. I.—Member of the Royal Institution of Great Britain.

M. R. I. A.—Member of the Royal Irish Academy.

Mrs.—Mistress.

M. R. S. L.—Member of the Royal Society of Literature.

MS.—Manuscript.

M. S.—Memoriæ Sacrum. Sacred to the Memory.

MSS.—Manuscripts.

Mus. D.—Doctor of Music.

M. W. S.—Member of the Wernerian Society.

N.—North.

n.—Note.

N. B.—Nota bene. Mark well.

Nem. Con.—Nemine Contradicente. No Person opposing or disagreeing.

Nem. Diss.—Nemine Dissentiente. No Person opposing or disagreeing.

Nep.—Nepos.

n. l.—Non liquet. It appears not.

N. L.—North Latitude.

Nr.—Noster. Our; our own.

N. S.—New Style.

N. T.—New Testament.

Ob.—Obiit. He or she died.

Ob.—Obolus. Three Half-pence.

Oct.—October.

8vo.—Octavo.

O. S.—Old Style.

O. T.—Old Testament.

oz.—Ounce.

P.—Publius.

p.—Page.

p.—Pugil. What may be taken up, in compounding Medicine, between the two Fingers and Thumb.

Pag.—Pagina. A Page of a Book.

P. C.—Patres Conscripti. Conscript Fathers; Senators.

Pent.—Pentecost.

Per Cent.—Per Centum. By the Hundred.

Philom.—Philomathes. A Lover of Learning.

Philomath.—Philomathematicus. A Lover of the Mathematics.

P. M.—Post Meridiem. Afternoon.

P. M. G.—Professor of Music at Gresham College.

Pon. M.—Pontifex Maximus.

P. P.—Pater Patriæ. The Father of his Country.

P. P. C.—[French] Pour prendre congé. To take Leave.

P. R.—Populus Romanus. The Roman People.

Prof.—Professor.

P. R. S.—President of the Royal Society.

P. S.—Postscript. After written.

P. S.—Privy Seal.

P. Th. G.—Professor of Divinity at Gresham College.

Pub.—Publicus.

Q.—Quintus.

Q.—Quadrans. A Farthing.

q.—Quasi. As it were; almost.

q.—Quære. Inquire.

Q. C.—Queen’s College.

Q. C.—Queen’s Counsel.

q. d.—Quasi dicat. As if he should say.

Q. E.—Quod est. Which is.

Q. E. D.—Quod erat demonstrandum. Which was the Thing to be demonstrated.

q. l.—Quantum libet. As much as you please.

Qm.—Quomodo. How, by what means.

q. s.—Quantum sufficit. A sufficient quantity.

Quæs.—Quæstor.

q. v.—Quantum vis. As much as you will.

q. v.—Quod vide. Which see.

4to.—Quarto.

Qv.—Query.

R.—Rex. King.

R. A.—Royal Academician.

R. A.—Royal Artillery.

R. E.—Royal Engineers.

Reg.—Regi.

Resp.—Respublica. Republic.

Rev.—Reverend.

R. M.—Royal Marines.

R. M.—Resident Magistrate.

R. N.—Royal Navy.

R. N. O.—Riddare af Nordstjerne. Knight of the Order of the Polar Star.

Ro.—Right-hand Page.

R. P.—Respublica. Republic.

R. S. S. commonly F. R. S.—Regiæ Societatis Socius. Fellow of the Royal Society.

R. S. V. P.—[French] Réponse s’il vous plaît. Answer if you please.

Rt. Hon.—Right Honourable.

R. W. O.—Riddare af Wasa Orden. Knight of the Order of Wasa.

S.—Sacrum; Sepulcrum; Senatus.

S.—South.

S.—Uncia. An Ounce.

Sax. Chron.—Saxon Chronicle.

S. C.—Senatûs Consultum. The Decree of the Senate.

Scil.—Scilicet. To wit.

Scip.—Scipio.

S. D.—Salutem dicit. Sends Health.

S. L.—South Latitude.

S. L.—Solicitor at Law (in Scotland).

S. P.—Salutem Precatur. He prays for his Prosperity.

S. P.—Sine prole. Without issue.

S. P. D.—Salutem plurimam dicet. He wishes much Health.

S. P. G.—Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.

S. P. Q. R.—Senatus Populusque Romanus. The Senate and People of Rome.

ss.—Semissis. Half a Pound (six Ounces). The half of any Thing.

S. S. C.—Solicitor before the Supreme Courts (Scotland).

St.—Saint.

S. T. D.—Sacræ Theologiæ Doctor.

S. T. P.—Sacrosanctæ Theologiæ Professor. Professor of Divinity.

S. V. B. E. E. Q. V.—Si vales, bene est; ego quoque valeo. If you are in good Health, it is well; I also am in good Health.

T.—Titus.

Tab.—Tabularius.

Testa de N.—Testa de Nevill.

T. L.—Testamento legavit. Bequeathed by Will.

Tr. Br. Mus.—Trustee of the British Museum.

T. R. E.—Tempore Regis Edwardi. Time of King Edward.

T. R. M.—Tribunus militum. A military Tribune.

U. E. I. C.—United East India Company.

U. J. D.—Utriusque Juris Doctor. Doctor of both Laws.

ult.—Ultimus. The last.

U. S.—United States of America.

v.—Vide. See.

v.—Verse.

v.—Versus. Against.

v.—(Sub) voce.

V. C.—Vir clarissimus. A celebrated Man.

v. g.—Verbi gratiâ. As for Example.

Vic.—Victores; Victor; Victoria.

viz.—Videlicet. That is to say.

Vl.—Videlicet. That is to say.

W.—West.

W. M. S.—Wesleyan Missionary Society.

W. S.—Writer to His Majesty’s Signet.

Xmas.—Christmas.

Xn.—Christian.

Xpofer.—Christopher.

Xps.—Christus.

Xt.—Christ.

Xtian.—Christian.

See Botanical Authorities. Law Authorities. Organic Remains. Sigla.

ACCENTED LETTERS.

“In English, the accentual marks are chiefly used in spelling-books and dictionaries, to mark the syllables which require a particular stress of the voice in pronunciation.

“The stress is laid on long and short syllables indiscriminately. In order to distinguish the one from the other, some writers of dictionaries[6] have placed the grave on the former, and the acute on the latter, in this manner: ‘Mìnor, míneral, lìvely, líved, rìval, ríver.’

“The proper mark to distinguish a long syllable is this ̄: as, ‘Rōsy:’ and a short one thus ̆: as ‘Fŏlly.’ This last mark is called a breve.

“A diæresis, thus marked ¨, consists of two points placed over one of the two vowels that would otherwise make a diphthong, and parts them into two syllables: as, ‘Creätor, coädjutor, aërial.’

“A circumflex, thus marked ^, when placed over some vowel of a word, denotes a long syllable: as, ‘Euphrâtes.’”—Murray.

The c à la queue, or the c with a tail, is a French sort, and sounds like ss, when it stands before a o u, as in ça, garçon. To make a tail to a capital C, a small figure of 5 with the top dash cut away, thus ⦢, and justified close to the bottom of the letter, answers the purpose, when it is required; for the letter-founders do not cast this letter with a tail, neither in the capitals nor small capitals. Ç.

The ñ is used in the Spanish language, and is pronounced like a double n, or rather like ni; but short and quick, as in España. It is a sort which is used in the middle of words, but rarely at the beginning.

In the Welsh language, ŵ and ŷ, as well as the other circumflex letters, are used either to direct the pronunciation, as in yngŵydd, in presence; ynghŷd, together; or else for distinction sake; as, mwg, a mug; mŵg, smoke; hyd, to, until; hŷd, length.

Accents. See Accented Letters.

ACTS OF PARLIAMENT.

There are various Acts of Parliament which affect printers, and inflict penalties for the neglect or violation of their provisions. Many printers frequently subject themselves to penalties, which are in many instances very heavy, through ignorance of those laws. To enable them to avoid these penalties, and also to show the legal restrictions on the business, I have taken great pains to examine the whole of the Statutes at Large, and to extract from them all such clauses as are in force, that affect the trade.—See the respective subjects.

Admiration, Note of. See Punctuation.

ADVERTISEMENTS.

By the Act 3 & 4 Will. 4. c. 23. s. 1., intituled

“An Act to reduce the Stamp Duties on Advertisements and on certain Sea Insurances; to repeal the Stamp Duties on Pamphlets, and on Receipts for Sums under Five Pounds; and to exempt Insurances on Farming Stock from Stamp Duties;” the Act 55 Geo. 3. c. 184.; the Act 55 Geo. 3. c. 185.; and the Act 56 Geo. 3. c. 56., for the Duties granted and payable in Ireland, are repealed; “save and except so much and such Part and Parts of the said Duties respectively as shall have accrued or been incurred before or upon the said Fifth Day of July One thousand eight hundred and thirty-three, and shall then or at any Time afterwards be or become due or payable and remain in arrear and unpaid; all which said Duties so remaining in arrear and unpaid as aforesaid shall be recoverable by the same Ways and Means, and with such and the same Penalties, as if this Act had not been made.

s. 2. “And be it enacted, That from and after the Fifth Day of July One thousand eight hundred and thirty-three, in lieu and stead of the said several Duties upon Advertisements and Sea Insurances by this Act repealed, there shall be granted, raised, levied, collected, and paid, in Great Britain and Ireland respectively, unto and for the Use of His Majesty, His Heirs and Successors, for and in respect of the several Articles, Matters, and Things mentioned and described in the Schedule to this Act annexed, the several Duties or Sums of Money set down in Figures against the same respectively, or otherwise specified and set forth in the said Schedule; and that the said Schedule, and the several Provisions, Regulations, and Directions therein contained, with respect to the said Duties, and the Articles, Matters, and Things charged therewith, shall be deemed and taken to be Part of this Act; and that the said Duties shall be denominated and deemed to be Stamp Duties, and shall be under the Care and Management of the Commissioners of Stamps for the Time being for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

s. 3. “And in order to provide for the Collection of the Duty by this Act granted on[7] Advertisements contained in or published with any Pamphlet, Literary Work, or Periodical Paper, be it enacted, That one printed Copy of every Pamphlet or Literary Work or Periodical Paper (not being a Newspaper), containing or having published therewith any Advertisements or Advertisement liable to Stamp Duty, which shall be published within the Cities of London, Edinburgh, or Dublin respectively, or within Twenty Miles thereof respectively, shall, within the Space of Six Days next after the Publication thereof, be brought, together with all Advertisements printed therein, or published or intended to be published therewith, to the Head Office for Stamps in Westminster, Edinburgh, or Dublin nearest to which such Pamphlet, Literary Work, or Periodical Paper shall have been published, and the Title thereof, and the Christian Name and Surname of the Printer and Publisher thereof, with the Number of Advertisements contained therein or published therewith; and any Stamp Duty by Law payable in respect of such Advertisements shall be registered in a Book to be kept at such Office, and the Duty on such Advertisements shall be there paid to the Receiver General of Stamp Duties for the Time being, or his Deputy or Clerk, or the proper authorized Officer, who shall thereupon forthwith give a Receipt for the same; and one printed Copy of every such Pamphlet, Literary Work, or Paper as aforesaid, which shall be published in any Place in the United Kingdom, not being within the Cities of London, Edinburgh, or Dublin, or within Twenty Miles thereof respectively, shall, within the Space of Ten Days next after the Publication thereof, be brought, together with all such Advertisements as aforesaid, to the Head Distributor of Stamps for the Time being within the District in which such Pamphlet, Literary Work, or Paper shall be published; and such Distributor is hereby required forthwith to register the same in manner aforesaid in a Book to be by him kept for that Purpose; and the Duty payable in respect of such Advertisements shall be thereupon paid to such Distributor, who shall give a Receipt for the same; and if the Duty which shall be by Law payable in respect of any such Advertisements as aforesaid shall not be duly paid within the respective Times and in the Manner herein-before limited and appointed for that Purpose, the Printer and Publisher of such Pamphlet, Literary Work, or Paper, and the Publisher of any such Advertisements, shall respectively forfeit and pay the Sum of Twenty Pounds for every such Offence; and in any Action, Information, or other Proceeding for the Recovery of such Penalty, or for the Recovery of the Duty on any such Advertisements, Proof of the Payment of the said Duty shall lie upon the Defendant.

s. 4. “And be it enacted, That all the Powers, Provisions, Clauses, Regulations, and Directions, Fines, Forfeitures, Pains, and Penalties, contained in or imposed by the several Acts of Parliament relating to the Duties on Advertisements and Sea Insurances respectively, and the several Acts of Parliament relating to any prior Duties of the same Kind or Description, in Great Britain and Ireland respectively, shall be of full Force and Effect with respect to the Duties by this Act granted, and to the Vellum, Parchment, Paper, Articles, Matters, and Things charged or chargeable therewith, and to the Persons liable to the Payment of the said Duties, so far as the same are or shall be applicable in all Cases not hereby expressly provided for, and shall be observed, applied, enforced, and put in execution for the raising, levying, collecting, and securing of the said Duties hereby granted, and otherwise relating thereto, so far as the same shall not be superseded by and shall be consistent with the express Provisions of this Act, as fully and effectually to all Intents and Purposes as if the same had been herein repeated and especially enacted with reference to the said Duties by this Act granted.”

THE SCHEDULE.

Advertisements:—

| Duty. | |

| For and in respect of every Advertisement contained in or published with any Gazette or other Newspaper, or contained in or published with any other Periodical Paper, or in or with any Pamphlet or Literary Work, | £ s. d. |

| Where the same shall be printed and published in Great Britain | 0 1 6 |

| And where the same shall be printed and published in Ireland | 0 1 0 |

[So much of this Act repealed by 6 & 7 Will. 4. c. 76. s. 32. “as provides the Mode of collecting the Duty on Advertisements contained in or published with any Pamphlet, Periodical Paper, or Literary Work.”]

Albion Press. See Cope’s Press.

ALGEBRAIC CHARACTERS.

+ is the sign of addition; as c + d denotes that d is to be added to c.

- is the sign of subtraction; thus, c - d implies that d is to be subtracted from c.

× is the sign of multiplication; as c × d means the product of c and d.

÷ is the sign of division; as c ÷ d signifies the quotient of c and d.

= is the sign of equality; thus c + d = e means the sum of c and d equals e.

√ is the sign of the square root; thus √x denotes the square root of x.

∛ is the sign of the cube root, and generally any root of a quantity may be denoted by this sign, with the index of the root placed over it; thus ∛x signifies the cube root, ∜x the biquadrate root, &c.; but they may likewise be represented by the reciprocals of these indices; as x½, x⅓, implying the square and cube roots of x.

A vinculum is a line drawn over several quantities, and means that they are taken together, as √ax + b signifies the square root of ax and b.—Phillips’s Compendium of Algebra. 12mo. 1824.

Almanack. See Nautical Almanack.

ALPHABET.

A perfect alphabet of the English language, and, indeed, of every other language, would contain a number of letters, precisely equal to the number of simple articulate sounds belonging to the language. Every simple sound would have its distinct character; and that character be the representative of no other sound. But this is far from being the state of the English alphabet. It has more original sounds than distinct significant letters; and, consequently, some of these letters are made to represent, not one sound alone, but several sounds. This will appear by reflecting, that the sounds signified by the united letters th, sh, ng, are elementary, and have no single appropriate characters, in our alphabet; and the letters a and u represent the different sounds heard in hat, hate, hall; and but, bull, mute.

The letters of the English language, called the English Alphabet, are twenty-six in number.—Murray.

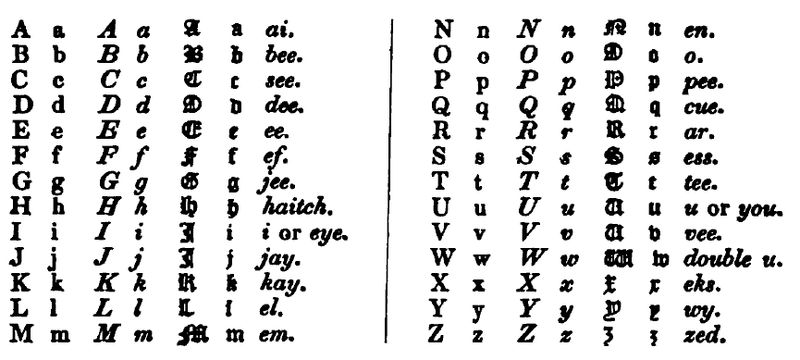

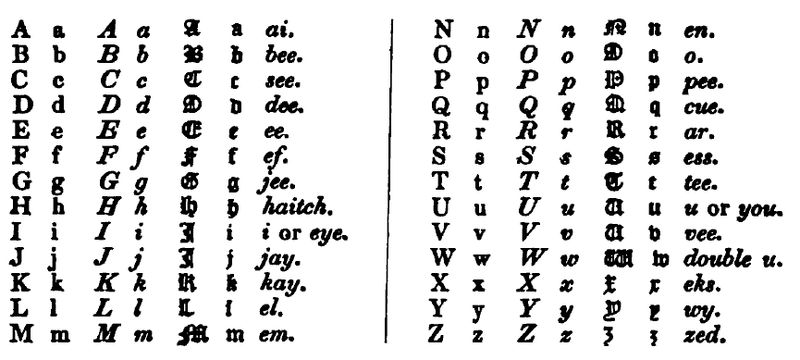

The following is a list of the Roman, Italic, and Old English Characters, being those used at the present day in England. The Roman and Italic are also used by most of the European nations.

| A a | A a | A a | ai. |

| B b | B b | B b | bee. |

| C c | C c | C c | see. |

| D d | D d | D d | dee. |

| E e | E e | E e | ee. |

| F f | F f | F f | ef. |

| G g | G g | G g | jee. |

| H h | H h | H h | haitch. |

| I i | I i | I i | i or eye. |

| J j | J j | J j | jay. |

| K k | K k | K k | kay. |

| L l | L l | L l | el. |

| M m | M m | M m | em. |

| N n | N n | N n | en. |

| O o | O o | O o | o. |

| P p | P p | P p | pee. |

| Q q | Q q | Q q | cue. |

| R r | R r | R r | ar. |

| S s | S s | S s | ess. |

| T t | T t | T t | tee. |

| U u | U u | U u | u or you. |

| V v | V v | V v | vee. |

| W w | W w | W w | double u. |

| X x | X x | X x | eks. |

| Y y | Y y | Y y | wy. |

| Z z | Z z | Z z | zed. |

For the characters of the different languages, see their respective names, Arabic, &c.

Tacquet, an able mathematician, in his Arithmeticiæ Theor., Amst. 1704, states, that the various combinations of the twenty-four letters (without any repetition) will amount to

620,448,401,733,239,439,360,000.

Thus it is evident, that twenty-four letters will admit of an infinity of[9] combinations and arrangements, sufficient to represent not only all the conceptions of the mind, but all words in all languages whatever.

Clavius the Jesuit, who also computes these combinations, makes them to be only 5,852,616,738,497,664,000.

As there are more sounds in some languages than in others, it follows of course that the number of elementary characters, or letters, must vary in the alphabets of different languages. The Hebrew, Samaritan, and Syriac alphabets, have twenty-two letters; the Arabic, twenty-eight; the Persic, and Egyptian or Coptic, thirty-two; the present Russian, forty-one; the Shanscrit, fifty; the Cashmirian and Malabaric are still more numerous.—Astle.

ALTERATION OF MARGIN.

In works that are published in different sizes, this is the changing of the margin from the small paper to the large paper edition, when at press.

After the margin for the small paper copies is finally made, the additional width of the gutters, the backs, and the heads, is ascertained in the same manner, by folding a sheet of the large paper, that it was in the first instance. The additional pieces for the change should, if possible, be in one piece for each part. See Margin.

Folios, quartos, and octavos, are the sizes most usually printed with an alteration of margin; duodecimos are sometimes, but rarely; of smaller sizes I never knew an instance.

The alteration of margin requires care, for it occasionally happens that the sheet is imposed with the wrong furniture; and where it happens to be in one form only, and that form is first laid on, it sometimes passes undiscovered till a revise of the second form is pulled, when the error is detected, but too late to rectify it; the consequence must be, to cancel a part of the sheet, or to print the reiteration with the margin also wrong; nay, sometimes both forms are worked off with the furniture wrong, without being perceived till the compositor comes to distribute, particularly when they are printed at different presses. Such errors destroy the uniformity of the book, and spoil its appearance.

These mistakes can only be avoided by care and attention on the part of the compositor, the reader, and the pressman; but I would recommend that the furniture for the alteration should be cut of different lengths from the furniture of the small paper: in octavos the gutters and backs should be the exact length of the page, and be always imposed within the sidestick; and the head should be the width of the two pages and the gutter, and be imposed within the footstick. This method of cutting the furniture of precise lengths for the alteration, and locking it up within the side and foot sticks, will not only distinguish it from the rest of the furniture, and from the pieces that may be put in for the convenience of quoining the form, but will also preserve it from being injured by the mallet and shooting stick, in locking up, and by the indention of the quoins.

The same principle, of cutting the alteration to precise lengths, and locking it up within the side and foot sticks, will hold good in all other sizes, where it is required: in quartos, the pieces must be cut to the length and width of the page; and in folios to the length of the page only, as the margin of the head is regulated at the press.

ANCIENT CUSTOMS.

The following Customs used in Printing Offices in former times are extracted from Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises, published in 1683, the first practical work that appeared on the Art of Printing. I insert them because I think it interesting to trace the old Customs, that were established by printers to preserve Order among[10] themselves; and to show the changes that have taken place since that period. The insertion of them in this place will also tend to preserve them, as the original work is now very scarce, and this department of it has been superseded by subsequent publications, which however, with the exception of Mr. Hansard’s work, have not copied these Customs.

“Ancient Customs used in a Printing-house.

“Every Printing-house is by the Custom of Time out of mind, called a Chappel; and all the Workmen that belong to it are Members of the Chappel: and the Oldest Freeman is Father of the Chappel. I suppose the stile was originally conferred upon it by the courtesie of some great Churchman, or men, (doubtless when Chappels were in more veneration than of late years they have been here in England) who for the Books of Divinity that proceeded from a Printing-house, gave it the Reverend Title of Chappel.

“There have been formerly Customs and By-Laws made and intended for the well and good Government of the Chappel, and for the more Civil and orderly deportment of all its Members while in the Chappel; and the Penalty for the breach of any of these Laws and Customs is in Printers Language called a Solace.

“And the Judges of these Solaces, and other Controversies relating to the Chappel or any of its Members, was plurality of Votes in the Chappel. It being asserted as a Maxim, That the Chappel cannot Err. But when any Controversie is thus decided, it always ends in the Good of the Chappel.

“1. Swearing in the Chappel, a Solace.

“2. Fighting in the Chappel, a Solace.

“3. Abusive Language, or giving the Ly in the Chappel, a Solace.

“4. To be Drunk in the Chappel, a Solace.

“5. For any of the Workmen to leave his Candle burning at Night, a Solace.

“6. If the Compositer let fall his Composing-stick, and another take it up, a Solace.

“7. Three Letters and a Space to lye under the Compositers Case, a Solace.

“8. If a Press-man let fall his Ball or Balls, and another take it up, a Solace.

“9. If a Press-man leave his Blankets in the Tympan at Noon or Night, a Solace.

“These Solaces were to be bought off, for the good of the Chappel: Nor were the price of these Solaces alike: For some were 12d. 6d. 4d. 2d. 1d. ob. according to the nature and quality of the Solace.

“But if the Delinquent prov’d Obstinate or Refractory, and would not pay his Solace at the Price of the Chappel, they Solac’d him.

“The manner of Solacing, thus.

“The Workmen take him by force, and lay him on his Belly athwart the Correcting-stone, and held him there while another of the Work-men with a Paper-board, gave him 10l. and a Purse, viz. Eleven blows on his Buttocks; which he laid on according to his own mercy. For Tradition tells us, that about 50 years ago one was Solaced with so much violence, that he presently P——d Blood; and shortly after dyed of it.

“These nine Solaces were all the Solaces usually and generally accepted: yet in some particular Chappels the Work-men did by consent make other Solaces, viz.

“That it should be a Solace for any of the Workmen to mention Joyning their Penny or more apiece to send for Drink.

“To mention spending Chappel-money till Saturday night, or any other before agreed time.

“To Play at Quadrats, or excite any of the Chappel to Play at Quadrats; either for Money or Drink.

“This Solace is generally purchas’d by the Master-Printer; as well because it hinders the Workmens work, as because it Batters and spoils the Quadrats: For the manner how they Play with them is Thus: They take five or seven more m Quadrats (generally of the English Body) and holding their Hand below the Surface of the Correcting Stone, shake them in their Hand, and toss them upon the Stone, and then count how many Nicks upwards each man throws in three times, or any other number of times agreed on: And he that throws most Wins the Bett of all the rest, and stands out free, till the rest have try’d who throws fewest Nicks upwards in so many throws; for all the rest are free: and he pays the Bett.

“For any to Take up a Sheet, if he receiv’d Copy-money; Or if he receiv’d no Copy-money, and did Take up a Sheet, and carryed that Sheet or Sheets off the Printing-House till the whole Book was Printed off and Publisht.

“Any of the Workmen may purchase a Solace for any trivial matter, if the rest of the Chappel consent to it. As if any of the Workmen Sing in the Chappel; he that is[11] offended at it may, with the Chappels Consent purchase a penny or two penny Solace for any Workmans singing after the Solace is made; Or if a Workman or a Stranger salute a Woman in the Chappel, after the making of the Solace, it is a Solace of such a Value as is agreed on.

“The price of all Solaces to be purchased is wholly Arbitrary in the Chappel. And a Penny Solace may perhaps cost the Purchaser Six Pence, Twelve Pence, or more for the Good of the Chappel.

“Yet sometimes Solaces may cost double the Purchase or more. As if some Compositer have (to affront a Press-man) put a Wisp of Hay in the Press-man’s Ball-Racks; If the Press-man cannot well brook this affront, he will lay six Pence down on the Correcting Stone to purchase a Solace of twelve pence upon him that did it; and the Chappel cannot in Justice refuse to grant it: because it tends to the Good of the Chappel: And being granted, it becomes every Members duty to make what discovery he can: because it tends to the farther Good of the Chappel: And by this means it seldom happens but the Agressor is found out.

“Nor did Solaces reach only the Members of the Chappel, but also Strangers that came into the Chappel, and offered affronts or indignities to the Chappel, or any of its Members; the Chappel would determine it a Solace. Example,

“It was a Solace for any to come to the King’s Printing-house and ask for a Ballad.

“For any to come and enquire of a Compositer, whether he had News of such a Galley at Sea.

“For any to bring a Wisp of Hay, directed to any of the Press-men.

“And such Strangers were commonly sent by some who knew the Customs of the Chappel, and had a mind to put a Trick upon the Stranger.

“Other Customs were used in the Chappel, which were not Solaces, viz. Every new Workman to pay half a Crown; which is called his Benvenue: This Benvenue being so constant a Custome is still lookt upon by all Workmen as the undoubted Right of the Chappel, and therefore never disputed; yet he who has not paid his Benvenue is no Member of the Chappel nor enjoys any benefit of Chappel-Money.

“If a Journey-man Wrought formerly upon the same Printing House, and comes again to Work on it, pays but half a Benvenue.

“If a Journey-man Smout more or less on another Printing-House and any of the Chappel can prove it, he pays half a Benvenue.

“I told you before that abusive Language or giving the Lye was a Solace: But if in discourse, when any of the Workmen affirm any thing that is not believed, the Compositer knocks with the back corner of his Composing-stick against the lower Ledge of his Lower Case, and the Press-man knocks the handles of his Ball-stocks together: Thereby signifying the discredit they give to his Story.

“It is now customary that Journey-men are paid for all Church Holy days that fall not on a Sunday, Whether they Work or no: And they are by Contract with the Master Printer paid proportionably for what they undertake to Earn every Working day, be it half a Crown, two Shillings, three Shillings, four Shillings, &c.

“It is also customary for all the Journey-men to make every Year new Paper Windows, whether the old will serve again or no; Because that day they make them, the Master Printer gives them a Way-goose; that is, he makes them a good Feast, and not only entertains them at his own House, but besides, gives them Money to spend at the Ale-house or Tavern at Night; And to this Feast they invite the Correcter, Founder, Smith, Joyner, and Inck-maker, who all of them severally (except the Correcter in his own Civility) open their Purse-strings and add their Benevolence (which Workmen account their duty, because they generally chuse these Workmen) to the Master Printers: But from the Correcter they expect nothing, because the Master Printer chusing him, the Workmen can do him no kindness.

“These Way-gooses, are always kept about Bartholemew-tide. And till the Master-Printer have given this Way-goose, the journey-men do not use to work by Candle Light.

“If a Journey-man marry, he pays half a Crown to the Chappel.

“When his Wife comes to the Chappel, she pays six Pence: and then all the Journey-men joyn their two Pence apiece to Welcome her.

“If a Journeyman have a Son born, he pays one Shilling.

“If a Daughter born, six Pence.

“The Father of the Chappel drinks first of Chapel Drink, except some other Journey-man have a Token; viz. Some agreed piece of Coin or Mettle markt by consent of the Chappel: for then producing that Token, he Drinks first. This Token is always given to him who in the Round should have Drank, had the last Chappel-drink held out. Therefore when Chappel-drink comes in, they generally say, Who has the Token?

“Though these Customs are no Solaces; yet the Chappel Excommunicates the Delinquent; and he shall have no benefit of Chappel-money till he have paid.

“It is also customary in some Printing-houses that if the Compositer or Press-man make either the other stand still through the neglect of their contracted Task, that then he who neglected, shall pay him that stands still as much as if he had Wrought.

“The Compositers are Jocosely called Galley Slaves: Because allusively they are as it were bound to their Gallies.

“And the Press-men are Jocosely called Horses: Because of the hard Labour they go through all day long.

“An Apprentice when he is Bound pays half a Crown to the Chappel, and when he is made Free, another half Crown to the Chappel; but is yet no Member of the Chappel; And if he continue to Work Journey-work in the same House, he pays another half Crown, and is then a Member of the Chappel.

“The Printers of London, Masters and Journey-men, have every Year a general Feast, which since the re-building of Stationers Hall is commonly kept there. This Feast is made by four Stewards, viz. two Masters and two Journey-men; which Stewards, with the Collection of half a Crown apiece of every Guest, defray the Charges of the whole Feast; And as they collect the Half-Crowns, they deliver every Guest a Ticket, wherein is specified the Time and Place they are to meet at, and the Church they are to go to: To which Ticket is affixed the Names and Seals of each Steward.

“It is commonly kept on or about May-day: When, about ten a Clock in the Morning they meet at Stationers Hall, and from thence go to some Church thereabouts; Four Whifflers (as Servitures) by two and two walking before with White Staves in their Hands, and Red and Blew Ribbons hung Belt-wise upon their left Shoulders. Those go before to make way for the Company. Then walks the Beadle of the Company of Stationers, with the Company’s Staff in his Hand, and Ribbons as the Whifflers, and after him the Divine (whom the Stewards before ingag’d to Preach them a Sermon) and his Reader. Then the Stewards walk by two and two, with long White Wands in their Hands, and all the rest of the Company follows, till they enter the Church.

“Then Divine Service begins, Anthems are Sung, and a Sermon Preached to suit the Solemnity: Which ended, they in the same order walk back again to Stationers Hall; where they are immediately entertain’d with the City Weights and other Musick: And as every Guest enters, he delivers his Ticket (which gives him Admittance) to a Person appointed by the Stewards to receive it.

“The Master, Wardens and other Grandees of the Company (although perhaps no Printers) are yet commonly invited, and take their Seats at the upper Table, and the rest of the Company where it pleases them best. The Tables being furnish’d with variety of Dishes of the best Cheer: And to make the entertainment more splendid is usher’d in with Loud Musick. And after Grace is said (commonly by the Minister that Preach’d the Sermon) every one Feasts himself with what he likes Best; whiles the Whifflers and other Officers Wait with Napkins, Plates, Beer, Ale, and Wine, of all sorts, to accommodate each Guest according to his desire. And to make their Cheer go cheerfuller down, are entertained with Musick and Songs all Dinner time.

“Dinner being near ended, the Kings and the Dukes Healths is begun, by the several Stewards at the several Tables, and goes orderly round to all the Guests.

“And whiles these Healths are Drinking, each Steward sets a Plate on each Table, beginning at the upper end, and conveying it downwards, to Collect the Benevolence of Charitable minds towards the relief of Printers Poor Widows. And at the same time each Steward distributes a Catalogue of such Printers as have held Stewards ever since the Feast was first kept, viz. from the Year of Christ 1621.

“After Dinner, and Grace said, the Ceremony of Electing new Stewards for the next Year begins: Therefore the present Stewards withdraw into another Room: And put Garlands of Green Lawrel, or of Box on their Heads, and White-wands in their Hands, and are again Usher’d out of the withdrawing Room by the Beadle of the Company, with the Companys Staff in his Hand, and with Musick sounding before them: Then follows one of the Whifflers with a great Bowl of White-wine and Sugar in his Right Hand, and his Whifflers Staff in his Left: Then follows the Eldest Steward, and then another Whiffler, as the first, with a Bowl of White-wine and Sugar before the second Steward, and in like manner another Whiffler before the Third, and another before the Fourth. And thus they walk with Musick sounding before them three times round the Hall: And in a fourth round the first Steward takes the Bowl of his Whiffler and Drinks to one (whom before he resolved on) by the Title of Mr. Steward Elect: And taking the Garland off his own Head puts it upon the Steward Elects Head. At which Ceremony the Spectators clap their Hands, and such as stand on the Tables or Benches, so Drum with their Feet that the whole Hall is filled with Noise, as applauding the Choice. Then the present Steward takes out the Steward Elect, giving[13] him the Right Hand, and walks with him Hand in Hand, behind the three present Stewards another Round about the Hall: And in the next Round, as aforesaid, the second Steward Drinks to another with the same Ceremony as the first did; and so the Third Steward, and so the Fourth, and then all walk one Round more Hand in Hand about the Hall, that the Company may take notice of the Stewards Elect. And so ends the Ceremony of the Day.

“This Ceremony being over, such as will go their ways; but others that stay, are Diverted with Musick, Songs, Dancing, Farcing, &c. till at last they all find it time to depart.”

Ancient Names of Cities and Towns. See Names.

Anglo-Saxon. See Saxon.

ANTEPENULTIMATE.

The last syllable but two of a word.

APOSTROPHE.

An apostrophe, marked thus ’, is used to abbreviate or shorten a word: as, ’tis for it is; tho’ for though; e’en for even; judg’d for judged. Its chief use is to show the genitive case of nouns: as, “A man’s property; a woman’s ornament.”—Murray.

Authors frequently, in the hurry of writing, abbreviate their words and use the apostrophe; but a compositor, however his copy may be written, should never abbreviate any word in prose works, except he be particularly ordered so to do.

The apostrophe is also used in printing to close an extract, or to show where it finishes; and in dialogues, frequently, to close each person’s speech; in both cases it is usually put close to the end of the word, without any space before it, except where the word finishes with a kerned letter, and then a hair space, or one just sufficient for their preservation is used; when it comes after an ascending letter, a hair space should also be put between them. See Quotation.

The apostrophe is not used for abbreviation in the Holy Scriptures, nor in Forms of Prayers; but every thing there is set full and at length. To this even the Latin law language had regard, and did not shorten the word Dominus, when it had reference to God; whereas Dom. Reg. is put where our Lord the King is understood.

Applegath, Augustus. See Machines.

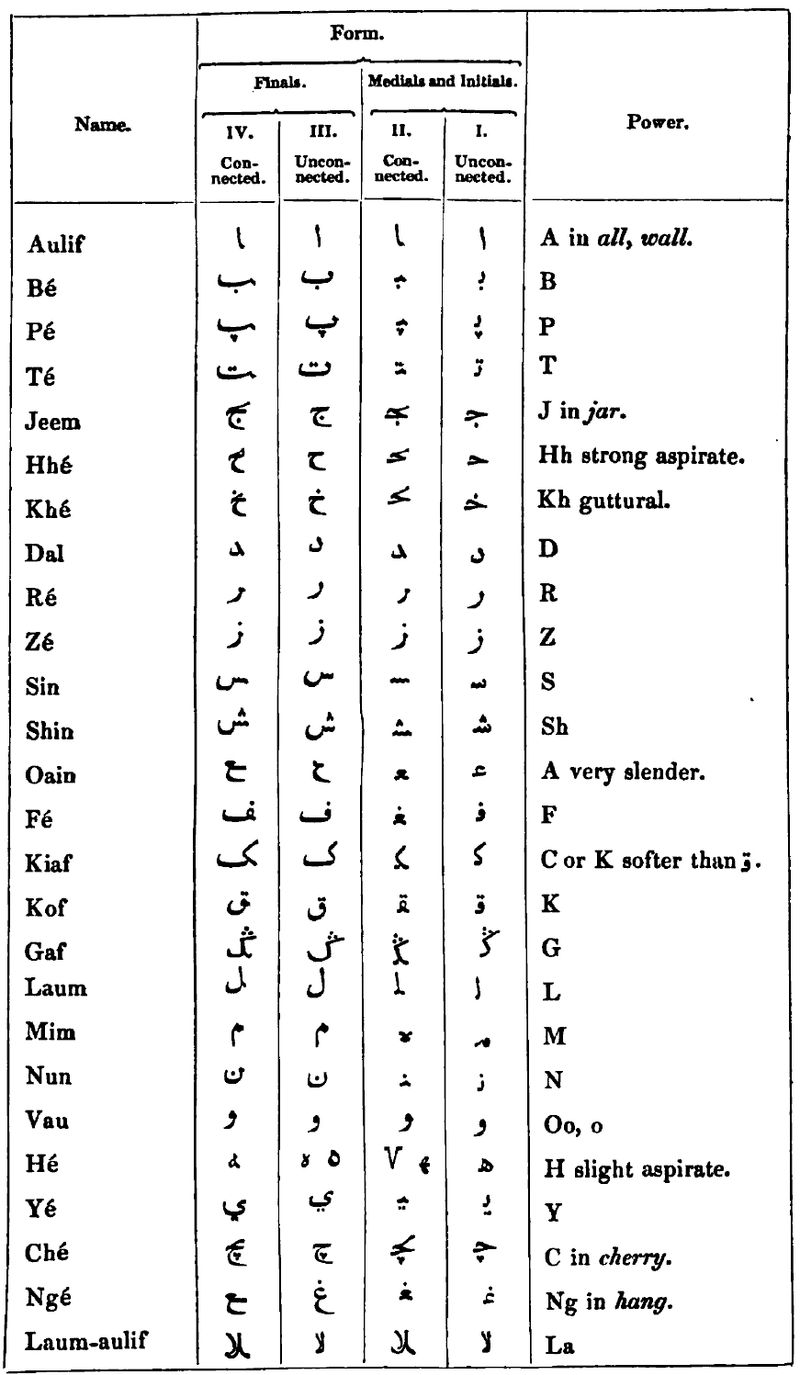

ARABIC.

Arabic is read from right to left. The method of composing it is upside down, and after the points are placed at the top of the letters it is turned in the composing stick.

Mr. Astle says, “The old Arabic characters are said to be of very high antiquity; for Ebn Hashem relates, that an inscription in it was found in Yaman, as old as the time of Joseph. These traditions may have given occasion to some authors to suppose the Arabians to have been the inventors of letters; and Sir Isaac Newton supposes, that Moses learned the alphabet from the Midianites, who were Arabians.

“The Arabian alphabet consists of twenty-eight letters, which are somewhat similar to the ancient Kufic, in which characters the first copies of the Alcoran were written.

“The present Arabic characters were formed by Ebn Moklah, a learned Arabian, who lived about 300 years after Mahomet. We learn from the Arabian writers themselves, that their alphabet is not ancient.”

Seven different styles of writing are used by the Arabs in the present day. Herbin has given descriptions and specimens of them in an Essay on Oriental Caligraphy at the end of his “Développemens des Principes de la Langue Arabe Moderne.”

The alphabets are copied, and the following observations are translated, from Baron De Sacy’s Arabic Grammar, 2 vol. 8vo. Paris, 1831.

7. It was long thought that the written character which the Arabs most generally use at the present day, and which is called neskhi, was invented[14] only about the commencement of the 4th century of the Hegira; and, indeed, it appears that the Arabs, before this epoch, used another character which we call Cufic, or Coufic, from the town of Coufa, where, doubtlessly, it first was brought into use. This character has so great a resemblance to the ancient Syriac character called Estranghelo, that it is extremely probable that the Arabs borrowed it from the people of Syria. Nevertheless, even the name of Coufic, given to this character, proves that it is not that which the Arabs of the Hedjaz made use of in the time of Mohammed, the town from which it takes its name having been founded only in A. H. 17. Some papyri lately discovered in Egypt have apprised us that the character which the Arabs of the Hedjaz made use of in the 1st century of the Hegira, differed little from that which is called neskhi. Moreover, in the time of Mohammed, writing was, among these Arabs, if we may believe their historic traditions, an invention very recent, and its use was very circumscribed. But it was otherwise, according to all appearances, among the Arabs, whether nomadic or settled, of Yemen, of Irak, and perhaps of Central Arabia; for, although we do not know the characters which the Arabs made use of in very ancient times, and the few traditions which Mussulman writers have handed down to us on this subject throw but very little light on this point of antiquity, it is scarcely possible to imagine that all the people of Arabia should have remained without a written character until the 6th century of the Christian era. The Jewish and the Christian religions were widely diffused in Arabia; the Ethiopians, who professed the latter faith, had even conquered Yemen, and retained its possession for a long while: another part of Arabia had frequent political relations with Persia, and it is found at many times in a state of dependence, more or less immediate, on the kings of the Sassanian dynasty. Under these circumstances, can it be reasonably supposed that the Arabs were ignorant of the use of writing? Is it not more likely that what history tells us of their ignorance in this respect is true only of some tribes, of those, for example, who were settled at Mecca or in the neighbourhood of that town; and that the character which these received from Mesopotamia, a short time previous to Mohammed, having been employed to write the Kurán, soon spread over all Arabia with the Mohammedan religion, and caused the other more ancient sorts of writing to fall into desuetude? It is true, no vestige of these characters remains, but if one may be permitted to hazard a conjecture, they did not materially differ from that ancient alphabet, common to a great many nations of the East, and of which the Phœnician and Palmyrenian monuments, as well as the ruins of Nakschia-Roustam and of Kirmanschah, and the coins of the Sassanides, have perpetuated the knowledge even to our own days. Perhaps another sort of writing, peculiar to Southern Arabia, was only a variety of the Ethiopic.

8. The Arabs of Africa have a character differing slightly from that made use of by the Arabs of Asia. I do not comprehend, among the Africans, the inhabitants of Egypt, for they use the same character as the Asiatics. For the sake of comparison I have shown the manner in which the Jews and Syrians employ their peculiar character when they are writing in the Arabic language.

I do not speak here of the character called talik تعلیق or nestalik نستعليق, because it is peculiar to the Persians. I may say as much of the different kinds of writing proper to the Turks or to the people of India, among whom the Mussulmans of Persia have introduced their characters with their language and religion.

Arabic Alphabet.—The Neskhi Character.

Key to Column Headers—

OL - Order of the letters.

NL - Names of the Letters.

U - Unconnected.

JP - Joined to the preceding Letter only.

J - Joined to the preceding and following Letter.

JF - Joined to the following Letter only.

PL - Powers of the Letters.

NV - Numerical Value.

| OL | NL | Figures of the Letters. | PL | NV. | |||

| U | JP | J | JF | ||||

| 1. | Elif | ا | ـا | .... | .... | A. | 1. |

| 2. | Ba | ب | ـب | ـبـ | بـ | B. | 2. |

| 3. | Ta | ت | ـت | ـتـ | تـ | T. | 400. |

| 4. | Tsa | ث | ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | Ts. | 500. |

| 5. | Djim | ج | ـج | ـجـ | جـ | Dj. | 3. |

| 6. | Ha | ح | ـح | ـحـ | حـ | H. | 8. |

| 7. | Kha | خ | ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | Kh. | 600. |

| 8. | Dal | د | ـد | .... | .... | D. | 4. |

| 9. | Dzal | ذ | ـذ | .... | .... | Dz. | 700. |

| 10. | Ra | ر | ـر | .... | .... | R. | 200. |

| 11. | Za | ز | ـز | .... | .... | Z. | 7. |

| 12. | Sin | س | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | S, Ç. | 60. |

| 13. | Schin | ش | ـش | ـشـ | شـ | Sch. | 300. |

| 14. | Sad | ص | ـص | ـصـ | صـ | S, Ç. | 90. |

| 15. | Dhad | ض | ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | Dh. | 800. |

| 16. | Tha | ط | ـط | ـطـ | طـ | Th. | 9. |

| 17. | Dha | ظ | ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | Dh. | 900. |

| 18. | Aïn | ع | ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ’A | 70. |

| 19. | Ghaïn | غ | ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | Gh. | 1,000. |

| 20. | Fa | ف | ـف | ـفـ | فـ | F. | 80. |

| 21. | Kaf | ق | ـق | ـقـ | قـ | K. | 100. |

| 22. | Caf | ك | ـك | ـكـ | كـ | C. | 20. |

| 23. | Lam | ل | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | L. | 30. |

| 24. | Mim | م | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | M. | 40. |

| 25. | Noun | ن | ـن | ـنـ | نـ | N. | 50. |

| 26. | Hé | ه | ـه | ـهـ | هـ | Hé. | 5. |

| 27. | Waw | و | ـو | .... | .... | W. | 6. |

| 28. | Ya | ي | ـي | ـيـ | يـ | Y. | 10. |

| Lam-élif | لا [#] | ـلا | .... | .... | La. | ||

Harmonical Alphabet, Arabic, Hebrew, and Syriac.

| Arabic. | Hebrew. | Syriac. | |

| Elif | ـا | א | ܐ |

| Ba | بـ | ב | ܒ |

| Ta | تـ | ת | ܛ |

| Tsa | ثـ | תֿ | ܛ |

| Djim | جـ | ג̱ | ܓ |

| Ha | حـ | ה | ܗ |

| Kha | خـ | ךֿ כֿ | ܟ |

| Dal | ـد | ד | ܕ |

| Dzal | ـذ | דֿ | ܕ |

| Ra | ـر | ר | ܪ |

| Za | ـز | ז | ܙ |

| Sin | سـ | ס | ܣ |

| Schin | شـ | ש | ܫ |

| Sad | صـ | ץ צ | ܨ |

| Dhad | ضـ | ץֿ צֿ | ܨ |

| Tha | طـ | ט | ܬ |

| Dha | ظـ | טֿ | ܬ |

| Aïn | عـ | ע | ܥ |

| Ghaïn | غـ | גֿ | ܓ |

| Fa | فـ | ף פ | ܦ |

| Kaf | قـ | ק | ܩ |

| Caf | كـ | ך כ | ܩ |

| Lam | لـ | ל | ܠ |

| Mim | مـ | ם מ | ܡ |

| Noun | نـ | ן נ | ܢ |

| Hé | هـ | ח | ܗ |

| Waw | ـو | ו | ܘ |

| Ya | يـ | י | ܝ |

Observations on the Alphabet.

9. The letters of the Arabic alphabet have not always been arranged in the order in which they are at the present day. The Arabs themselves have preserved the remembrance of a more ancient order, and the value which they give to the letters when they are employed as figures, confirms the existence of this order, which they term aboudjed, in like manner as we call the alphabet a be ce.

The twenty-two first letters of the Arabic alphabet, thus arranged, are the same, and follow the same order, as those of the Hebrews and Syrians. It is very probable that the Arabs, as well as the others, had only these twenty-two letters originally, and that the other six were added afterwards, though it is not possible to determine precisely the time at which this addition took place.

10. The lam-elif لا is not a character per se, but only a junction of the lam ل to the élif ا.

12. The alphabet is divided into eight columns: the first contains the numbers which indicate the order of the letters; the second, the names of the letters; the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth show the different forms of which each letter is susceptible when it is, first, entirely isolated; second, joined only to that which precedes it; third, joined to that which precedes and also to that which follows it; and, fourth, joined only to that which follows it. There are several letters which are never joined to those which follow them: this causes the blanks in the fifth and sixth columns. It is as well, however, to observe, that when the د, the ذ,[17] the ر, the ز, and the و, are found followed by ه, at the end of a word, they may be joined together.

13. Many letters differ from each other only by the absence or addition of one or more points. These points are called by the Arabs نُقْطَةٌ; we call them diacritical points, a term derived from the Greek, signifying distinctive.

30. The elif ا, when marked with the hamza ء, is not a vowel. The sound may then be compared to the h not aspirated in the French words habit, histoire, homme, Hubert.

The elif, without the hamza, has no pronunciation of its own; it serves only to prolong the vowel a which precedes it; sometimes this vowel and the elif which follows, take a strong sound approaching to the French i.

31. The ب answers to B, and the ت to T. In Africa the pronunciation of ث is often given to the letter ت.

32. The ث answers to the English th, as in the word thing; and it cannot be rendered in French better than by the two letters TS. The greater part of the Arabs make no distinction between the pronunciation of this letter and that of ت; some indeed regard as vicious the pronunciation here indicated. The Persians and the Turks pronounce the ث as the French ç; I render it ordinarily by TH.

33. The ج represents a sound similar to that of the Italian g, when followed by an i, as in giardino, and may be expressed by the letters DJ. This pronunciation, which is most used, is that of the people of Arabia and Syria; but in Egypt, at Muscat, and perhaps in some other provinces, the ج is pronounced as g hard followed by an a or o, as in garrison, agony.

34. The ح indicates an aspiration stronger than that of the French h in the words heurter, héros, and similar to the manner in which the Florentines pronounce the c before a and o. At the end of words, this aspiration is still more difficult to imitate. For example, the word لُوح is pronounced as louèh.

35. The خ answers to the ch of the Germans when it is preceded by an a or an o, as in the words nacht, noch.

36. The د answers exactly to D.

37. The ذ represents a sound which is to that of د very nearly as the ث is to that of ت. It is expressed in French by the two letters DZ or DH. Most nations who speak the Arabic language make no difference between this letter and the preceding; they pronounce both as our D. Some others, as the Arabs of Muscat, pronounce the ذ as the French Z, and such is the usage of the Persians and Turks.

38. The ر answers exactly to R; and the ز to Z.

39. The س answers to the sound of s, when it is at the beginning of words. When this letter is found, in Arabic words, between two vowels, it may be rendered by ç, that its pronunciation may not be confounded[18] with that of z, which takes the sound of s, in similar cases, in French words.

40. The sound of ش is exactly rendered by the French CH, (sj Dutch, sch German, sh English). Many French writers render it by the three letters SCH, in order that foreigners may not confound its pronunciation with that of خ, which is the custom I generally follow.

From the manner in which the Arabs of Spain transcribed Spanish in Arabic characters, there is reason to believe that they pronounced the ش as an s strongly articulated, and the س as the ç or z.

41. The ص answers to our S, but it ought to be pronounced a little more strongly than the س, or with a sort of emphasis. It appears that the pronunciation of the two letters has often been confounded, as may be seen in the marginal notes of some copies of the Kurán, in the books of the Druses, and in modern Egyptian manuscripts.

42. The ض answers to D pronounced more strongly than the French d, or with a sort of emphasis. The Persians and Turks pronounce it as the French z, other nations, as DS. In rendering Arabic names into French, in order to express the ض, the two letters DH ought to be used.

43. The ط answers to the T articulated strongly and emphatically. If a person should wish, in writing in French, to distinguish it from ت, it may be rendered by TH.

44. The ظ differs in no respect, in pronunciation, from ض, and they may be rendered in the same manner. These two letters are very often confounded in manuscripts. It ought to be observed, however, that in Egypt the ظ is often pronounced as a Z, emphatically.

45. The peculiar pronunciation of ع cannot be expressed by any of the letters used among the nations of Europe.

The manner in which the Piedmontese pronounce the ñ appears to me to approach something to the sound ع. Examples: cañ chien, boñ bon, boña bonne.

46. The غ represents a sound which partakes of both r and g. Some writers have rendered this letter by rh, others by rg, and others by gh; but as the sound of the r ought to be almost imperceptible, I have thought it better to employ, in rendering the غ, the G alone or the two letters GH.

47. The ف answers exactly to F.

48. The ق indicates a sound very nearly like that of the French K, but it ought to be formed in the throat, and it is very difficult to imitate it well. Many Arabs, those of Muscat, for example, confound the pronunciation of this letter with that of غ, and this pronunciation is common in the states of Marocco. In a great part of Egypt, the ق is only a strong and quick aspiration, and it appears that this sound, very difficult to imitate, was the distinctive characteristic of the Arabs descended from Modhar.

49. The ك also answers to K, but it is not pronounced from the throat as the preceding letter. The Turks and many of the Arabs give[19] it a softened pronunciation, analogous to that of q in the French words queue, qui; and it may be rendered by putting an i after k. Some Arabs pronounce the ك and the ق as an Italian c before i, as in the word cio, a sound expressed in French by the letters tch.

50. The ل is perfectly rendered by L, and the م by M.

51. The ن is susceptible, according to the Arab grammarians, of many pronunciations. When it is followed by a vowel, it is pronounced always as N in the French word navire, but when it is followed immediately by another consonant the pronunciation varies.

52. The و is pronounced as OU in French, in the words oui, ouate. It can also be rendered by W pronounced in the manner of the English. The Turks and Persians pronounce it as the French V.