Transcriber’s Notes

The cover image was provided by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Punctuation has been standardized.

Most of the non-common abbreviations used to save space in printing have been expanded to the non-abbreviated form for easier reading. Abbreviations without clear meanings have been left unchanged.

Most common abbreviations have been expanded in tool-tips for screen-readers and may be seen by hovering the mouse over the abbreviation.

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated with a Transcriber’s Note.

Index references have not been checked for accuracy.

The symbol ‘‡’ indicates the description in parenthesis has been added to an illustration. This may be needed if there is no caption or if the caption does not describe the image adequately.

Footnotes are identified in the text with a superscript number and are shown immediately below the paragraph in which they appear.

Transcriber’s Notes are used when making corrections to the text or to provide additional information for the modern reader. These notes are identified by ♦♠♥♣ symbols in the text and are shown immediately below the paragraph in which they appear.

UNDER THE EDITORSHIP OF

The Rev. SAMUEL ROLLES DRIVER, D.D.

Regius Professor of Hebrew, Oxford

The Rev. ALFRED PLUMMER, M.A., D.D.

Late Master of University College, Durham

AND

The Rev. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BRIGGS, D.D.

Professor of Theological Encyclopædia and Symbolics

Union Theological Seminary, New York

The International Critical Commentary

On the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments

EDITORS’ PREFACE

THERE are now before the public many Commentaries, written by British and American divines, of a popular or homiletical character. The Cambridge Bible for Schools, the Handbooks for Bible Classes and Private Students, The Speaker’s Commentary, The Popular Commentary (Schaff), The Expositor’s Bible, and other similar series, have their special place and importance. But they do not enter into the field of Critical Biblical scholarship occupied by such series of Commentaries as the Kurzgefasstes exegetisches Handbuch zum Alten Testament; De Wette’s Kurzgefasstes exegetisches Handbuch zum Neuen Testament; Meyer’s Kritisch-exegetischer Kommentar; Keil and Delitzsch’s Biblischer Commentar über das Alte Testament; Lange’s Theologisch-homiletisches Bibelwerk; Nowack’s Handkommentar zum Alten Testament; Holtzmann’s Handkommentar zum Neuen Testament Several of these have been translated, edited, and in some cases enlarged and adapted, for the English-speaking public; others are in process of translation. But no corresponding series by British or American divines has hitherto been produced. The way has been prepared by special Commentaries by Cheyne, Ellicott, Kalisch, Lightfoot, Perowne, Westcott, and others; and the time has come, in the judgment of the projectors of this enterprise, when it is practicable to combine British and American scholars in the production of a critical, comprehensive Commentary that will be abreast of modern biblical scholarship, and in a measure lead its van.

Messrs. Charles Scribner’s Sons of New York, and Messrs. T. & T. Clark of Edinburgh, propose to publish such a series of Commentaries on the Old and New Testaments, under the editorship of Prof. C. A. Briggs, D.D., D.Litt., in America, and of Prof. S. R. Driver, D.D., D.Litt., for the Old Testament, and the Rev. Alfred Plummer, D.D., for the New Testament, in Great Britain.

The Commentaries will be international and inter-confessional, and will be free from polemical and ecclesiastical bias. They will be based upon a thorough critical study of the original texts of the Bible, and upon critical methods of interpretation. They are designed chiefly for students and clergymen, and will be written in a compact style. Each book will be preceded by an Introduction, stating the results of criticism upon it, and discussing impartially the questions still remaining open. The details of criticism will appear in their proper place in the body of the Commentary. Each section of the Text will be introduced with a paraphrase, or summary of contents. Technical details of textual and philological criticism will, as a rule, be kept distinct from matter of a more general character; and in the Old Testament the exegetical notes will be arranged, as far as possible, so as to be serviceable to students not acquainted with Hebrew. The History of Interpretation of the Books will be dealt with, when necessary, in the Introductions, with critical notices of the most important literature of the subject. Historical and Archæological questions, as well as questions of Biblical Theology, are included in the plan of the Commentaries, but not Practical or Homiletical Exegesis. The Volumes will constitute a uniform series.

The International Critical Commentary

ARRANGEMENT OF VOLUMES AND AUTHORS

THE OLD TESTAMENT

GENESIS. The Rev. John Skinner, D.D., Principal and Professor of Old Testament Language and Literature, College of Presbyterian Church of England, Cambridge, England.

[Now Ready.

EXODUS. The Rev. A. R. S. Kennedy, D.D., Professor of Hebrew, University of Edinburgh.

LEVITICUS. J. F. Stenning, M.A., Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford.

NUMBERS. The Rev. G. Buchanan Gray, D.D., Professor of Hebrew, Mansfield College, Oxford.

[Now Ready.

DEUTERONOMY. The Rev. S. R. Driver, D.D., D.Litt., Regius Professor of Hebrew, Oxford.

[Now Ready.

JOSHUA. The Rev. George Adam Smith, D.D., LL.D., Professor of Hebrew, United Free Church College, Glasgow.

JUDGES. The Rev. George Moore, D.D., LL.D., Professor of Theology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

[Now Ready.

SAMUEL. The Rev. H. P. Smith, D.D., Professor of Old Testament Literature and History of Religion, Meadville, Pa.

[Now Ready.

KINGS. The Rev. Francis Brown, D.D., D.Litt., LL.D., President and Professor of Hebrew and Cognate Languages, Union Theological Seminary, New York City.

CHRONICLES. The Rev. Edward L. Curtis, D.D., Professor of Hebrew, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

[Now Ready.

EZRA AND NEHEMIAH. The Rev. L. W. Batten, Ph.D., D.D., Rector of St. Mark’s Church, New York City, sometime Professor of Hebrew, P. E. Divinity School, Philadelphia.

PSALMS. The Rev. Charles A. Briggs, D.D., D.Litt., Graduate Professor of Theological Encyclopædia and Symbolics, Union Theological Seminary, New York.

[2 volumes. Now Ready.

PROVERBS. The Rev. C. H. Toy, D.D., LL.D., Professor of Hebrew, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

[Now Ready.

JOB. The Rev. S. R. Driver, D.D., D.Litt., Regius Professor of Hebrew, Oxford.

ISAIAH. Chapters I‒XXXIX. The Rev. G. Buchanan Gray, D.D., Professor of Hebrew, Mansfield College, Oxford.

ISAIAH. Chapters XL‒LXVI. The Rev. A. S. Peake, M.A., D.D., Dean of the Theological Faculty of the Victoria University and Professor of Biblical Exegesis in the University of Manchester, England.

JEREMIAH. The Rev. A. F. Kirkpatrick, D.D., Dean of Ely, sometime Regius Professor of Hebrew, Cambridge, England.

EZEKIEL. The Rev. G. A. Cooke, M.A., Oriel Professor of the Interpretation of Holy Scripture, University of Oxford, and the Rev. Charles F. Burney, D.Litt., Fellow and Lecturer in Hebrew, St. John’s College, Oxford.

DANIEL. The Rev. John P. Peters, Ph.D., D.D., sometime Professor of Hebrew, P. E. Divinity School, Philadelphia, now Rector of St. Michael’s Church, New York City.

AMOS AND HOSEA. W. R. Harper, Ph.D., LL.D., sometime President of the University of Chicago, Illinois.

[Now Ready.

MICAH TO HAGGAI. Prof. John P. Smith, University of Chicago; Prof. Charles P. Fagnani, D.D., Union Theological Seminary, New York; W. Hayes Ward, D.D., LL.D., Editor of The Independent, New York; Prof. Julius A. Bewer, Union Theological Seminary, New York, and Prof. H. G. Mitchell, D.D., Boston University.

ZECHARIAH TO JONAH. Prof. H. G. Mitchell, D.D., Prof. John P. Smith and Prof. J. A. Bewer.

ESTHER. The Rev. L. B. Paton, Ph.D., Professor of Hebrew, Hartford Theological Seminary.

[Now Ready.

ECCLESIASTES. Prof. George A. Barton, Ph.D., Professor of Biblical Literature, Bryn Mawr College, Pa.

[Now Ready.

RUTH, SONG OF SONGS AND LAMENTATIONS. Rev. Charles A. Briggs, D.D., D.Litt., Graduate Professor of Theological Encyclopædia and Symbolics, Union Theological Seminary, New York.

THE NEW TESTAMENT

ST. MATTHEW. The Rev. Willoughby C. Allen, M.A., Fellow and Lecturer in Theology and Hebrew, Exeter College, Oxford.

[Now Ready.

ST. MARK. Rev. E. P. Gould, D.D., sometime Professor of New Testament Literature, P. E. Divinity School, Philadelphia.

[Now Ready.

ST. LUKE. The Rev. Alfred Plummer, D.D., sometime Master of University College, Durham.

[Now Ready.

ST. JOHN. The Very Rev. John Henry Bernard, D.D., Dean of St. Patrick’s and Lecturer in Divinity, University of Dublin.

HARMONY OF THE GOSPELS. The Rev. William Sanday, D.D., LL.D., Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity, Oxford, and the Rev. Willoughby C. Allen, M.A., Fellow and Lecturer in Divinity and Hebrew, Exeter College, Oxford.

ACTS. The Rev. C. H. Turner, D.D., Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford, and the Rev. H. N. Bate, M.A., Examining Chaplain to the Bishop of London.

ROMANS. The Rev. William Sanday, D.D., LL.D., Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity and Canon of Christ Church, Oxford, and the Rev. A. C. Headlam, M.A., D.D., Principal of King’s College, London.

[Now Ready.

CORINTHIANS. The Right Rev. Archbishop Robertson, D.D., LL.D., Lord Bishop of Exeter, the Rev. Alfred Plummer, D.D., and Dawson Walker, D.D., Theological Tutor in the University of Durham.

GALATIANS. The Rev. Ernest D. Burton, D.D., Professor of New Testament Literature, University of Chicago.

EPHESIANS AND COLOSSIANS. The Rev. T. K. Abbott, B.D., D.Litt., sometime Professor of Biblical Greek, Trinity College, Dublin, now Librarian of the same.

[Now Ready.

PHILIPPIANS AND PHILEMON. The Rev. Marvin R. Vincent, D.D., Professor of Biblical Literature, Union Theological Seminary, New York City.

[Now Ready.

THESSALONIANS. The Rev. James E. Frame, M.A., Professor of Biblical Theology, Union Theological Seminary, New York.

THE PASTORAL EPISTLES. The Rev. Walter Lock, D.D., Warden of Keble College and Professor of Exegesis, Oxford.

HEBREWS. The Rev. A. Nairne, M.A., Professor of Hebrew in King’s College, London.

ST. JAMES. The Rev. James H. Ropes, D.D., Bussey Professor of New Testament Criticism in Harvard University.

PETER AND JUDE. The Rev. Charles Bigg, D.D., sometime Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History and Canon of Christ Church, Oxford.

[Now Ready.

THE EPISTLES OF ST. JOHN. The Rev. E. A. Brooke, B.D., Fellow and Divinity Lecturer in King’s College, Cambridge.

REVELATION. The Rev. Robert H. Charles, M.A., D.D., sometime Professor of Biblical Greek in the University of Dublin.

GENESIS

JOHN SKINNER, D.D.

The International Critical Commentary

A

CRITICAL AND EXEGETICAL

COMMENTARY

ON

GENESIS

BY

JOHN SKINNER, D.D., Honorary M.A. (Cambridge)

PRINCIPAL AND PROFESSOR OF OLD TESTAMENT LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE,

WESTMINSTER COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1910

TO

MY WIFE

It is a little over six years since I was entrusted by the Editors of “The International Critical Commentary” with the preparation of the volume on Genesis. During that time there has been no important addition to the number of commentaries either in English or in German. The English reader still finds his best guidance in Spurrell’s valuable Notes on the text, Bennett’s compressed but suggestive exposition in the Century Bible, and Driver’s thorough and masterly work in the first volume of the Westminster Commentaries; all of which were in existence when I commenced my task. While no one of these books will be superseded by the present publication, there was still room for a commentary on the more elaborate scale of the “International” series; and it has been my aim, in accordance with the programme of that series, to supply the fuller treatment of critical, exegetical, literary, and archæological questions, which the present state of scholarship demands.

The most recent German commentaries, those of Holzinger and Gunkel, had both appeared before 1904; and I need not say that to both, but especially to the latter, I have been greatly indebted. Every student must have felt that Gunkel’s work, with its æsthetic appreciation of the genius of the narratives, its wider historical horizons, and its illuminating use of mythological and folklore parallels, has breathed a new spirit into the investigation of Genesis, whose influence no writer on the subject can hope or wish to escape. The last-mentioned feature is considerably emphasised in the third edition, the first part of which (1909) was published just too late to be utilised for this volume. That I have not neglected the older standard commentaries of Tuch, Delitzsch, and Dillmann, or less comprehensive expositions like that of Strack, will be apparent from the frequent acknowledgments in the notes. The same remark applies to many books of a more general kind (mostly cited in the list of “Abbreviations”), which have helped to elucidate special points of exegesis.

The problems which invest the interpretation of Genesis are, indeed, too varied and far-reaching to be satisfactorily treated within the compass of a single volume. The old controversies as to the compatibility of the earlier chapters with the conclusions of modern science are no longer, to my mind, a living issue; and I have not thought it necessary to occupy much space with their discussion. Those who are of a different opinion may be referred to the pages of Dr. Driver, where they will find these matters handled with convincing force and clearness. Rather more attention has been given to the recent reaction against the critical analysis of the Pentateuch, although I am very far from thinking that that movement, either in its conservative or its more radical manifestation, is likely to undo the scholarly work of the last hundred and fifty years. At all events, my own belief in the essential soundness of the prevalent hypothesis has been confirmed by the renewed examination of the text of Genesis which my present undertaking required. It will probably appear to some that the analysis is pushed further than is warranted, and that duplicates are discovered where common sense would have suggested an easy reconciliation. That is a perfectly fair line of criticism, provided the whole problem be kept in view. It has to be remembered that the analytic process is a chain which is a good deal stronger than its weakest link, that it starts from cases where diversity of authorship is almost incontrovertible, and moves on to others where it is less certain; and it is surely evident that when the composition of sources is once established, the slightest differences of representation or language assume a significance which they might not have apart from that presumption. That the analysis is frequently tentative and precarious is fully acknowledged; and the danger of basing conclusions on insufficient data of this kind is one that I have sought to avoid. On the more momentous question of the historical or legendary character of the book, or the relation of the one element to the other, opinion is likely to be divided for some time to come. Several competent Assyriologists appear to cherish the conviction that we are on the eve of fresh discoveries which will vindicate the accuracy of at least the patriarchal traditions in a way that will cause the utmost astonishment to some who pay too little heed to the findings of archæological experts. It is naturally difficult to estimate the worth of such an anticipation; and it is advisable to keep an open mind. Yet even here it is possible to adopt a position which will not be readily undermined. Whatever triumphs may be in store for the archæologist,—though he should prove that Noah and Abraham and Jacob and Joseph are all real historical personages,—he will hardly succeed in dispelling the atmosphere of mythical imagination, of legend, of poetic idealisation, which are the life and soul of the narratives of Genesis. It will still be necessary, if we are to retain our faith in the inspiration of this part of Scripture, to recognise that the Divine Spirit has enshrined a part of His Revelation to men in such forms as these. It is only by a frank acceptance of this truth that the Book of Genesis can be made a means of religious edification to the educated mind of our age.

As regards the form of the commentary, I have endeavoured to include in the large print enough to enable the reader to pick up rapidly the general sense of a passage; although the exigencies of space have compelled me to employ small type to a much larger extent than was ideally desirable. In the arrangement of footnotes I have reverted to the plan adopted in the earliest volume of the series (Driver’s Deuteronomy), by putting all the textual, grammatical, and philological material bearing on a particular verse in consecutive notes running concurrently with the main text. It is possible that in some cases a slight embarrassment may result from the presence of a double set of footnotes; but I think that this disadvantage will be more than compensated to the reader by the convenience of having the whole explanation of a verse under his eye at one place, instead of having to perform the difficult operation of keeping two or three pages open at once.

In conclusion, I have to express my thanks, first of all, to two friends by whose generous assistance my labour has been considerably lightened: to Miss E. I. M. Boyd, M.A., who has rendered me the greatest service in collecting material from books, and to the Rev. J. G. Morton, M.A., who has corrected the proofs, verified all the scriptural references, and compiled the Index. My last word of all must be an acknowledgment of profound and grateful obligation to Dr. Driver, the English Editor of the series, for his unfailing interest and encouragement during the progress of the work, and for numerous criticisms and suggestions, especially on points of philology and archæology, to which in nearly every instance I have been able to give effect.

JOHN SKINNER.

Cambridge,

April 1910.

○ List of Abbreviations

○ Introduction

○ § 1. Introductory: Canonical Position of the Book—its general Scope—and Title

A. Nature of the Tradition.

○ § 2. History or Legend?

○ § 3. Myth and Legend—Foreign Myths—Types of mythical Motive

○ § 4. Historical Value of the Tradition

○ § 5. Preservation and Collection of the Traditions

B. Structure and Composition of the Book.

○ § 6. Plan and Divisions

○ § 7. The Sources of Genesis

○ § 8. The collective Authorship of Yahwist and Elohist

○ § 9. Characteristics of Yahwist and Elohist—their Relation to Literary Prophecy

○ § 10. Date and Place of Origin—Redaction of Jehovist

○ § 11. The Priestly Code and the Final Redaction

○ Commentary

Extended Notes:—

○ The Divine Image in Man

○ The Hebrew and Babylonian Sabbath

○ Babylonian and other Cosmogonies

○ The Site of Eden

○ The ‘Protevangelium’

○ The Cherubim

○ Origin and Significance of the Paradise Legend

○ Origin of the Cain Legend

○ The Cainite Genealogy

○ The Chronology of Chapter 5, etc.

○ The Deluge Tradition

○ Noah’s Curse and Blessing

○ The Babel Legend

○ Chronology of 1110 ff.

○ Historic Value of Chapter 14

○ Circumcision

○ The Covenant-Idea in Priestly-Code

○ Destruction of the Cities of the Plain

○ The Sacrifice of Isaac

○ The Treaty of Gilead and its historical Setting

○ The Legend of Peniel

○ The Sack of Shechem

○ The Edomite Genealogies

○ The Degradation of Reuben

○ The Fate of Simeon and Levi

○ The “Shiloh” Prophecy of 4910

○ The Zodiacal Theory of the Twelve Tribes

Index—

○ I. English

○ II. Hebrew

1. SOURCES (see pages xxxiv ff.), TEXTS, AND VERSIONS.

| E | Elohist, or Elohistic Narrative. |

| J | Yahwist, or Yahwistic Narrative. |

| JE | Jehovist, or the combined narrative of Yahwist and Elohist. |

| P or PC | The Priestly Code. |

| Pᵍ | The historical kernel or framework of Priestly-Code (see page lvii). |

| Rᴱ | Redactors within the schools of Elohist, Yahwist, and Priestly-Code, respectively. |

| Rᴶ | |

| Rᴾ | |

| Rᴶᴱ | The Compiler of the composite work Jehovist. |

| Rᴶᴱᴾ | The Final Redactor of the Pentateuch. |

| EV[V] | English Version[s] (Authorised or Revised). |

| Jub. | The Book of Jubilees. |

| MT | Massoretic Text. |

| OT | Old Testament. |

| Aq. | Greek Translation of Aquila. |

| Θ | Greek Translation of Theodotion. |

| Σ | Greek Translation of Symmachus. |

| Gr.-Ven. | Codex ‘Græcus Venetus’ (14th or 15th century.). |

| G | The Greek (Septuagint) Version of the Old Testament (edited by A. E. Brooke and N. M‘Lean, Cambridge, 1906). |

| Gᴸ | Lucianic recension of the LXX, edited by Lagarde, Librorum Veteris Testamenti canonicorum pars prior Græce, etc. (1883). |

| GA, B, E, M, etc. | Codices of LXX (see Brooke and M‘Lean, page v.). |

| L | Old Latin Version. |

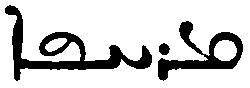

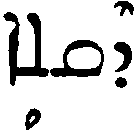

| S | The Syriac Version (Peshiṭtå). |

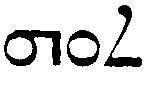

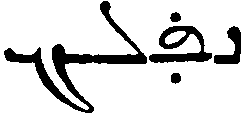

| ⅏ | The Samaritan Recension of the Pentateuch (Walton’s ‘London Polyglott’). |

| Tᴼ | The Targum of Onkelos [2nd century A.D.] (edited by Berliner, 1884). |

| Tᴶ | The Targum of Jonathan [8th century A.D.] (edited by Ginsburger, 1903). |

| V | The Vulgate. |

2. COMMENTARIES.

| Ayles | Herbert Henry Baker Ayles, A critical Commentary on Genesis ii. 4‒iii. 25 (1904). |

| Ba[ll] | Charles James Ball, The Book of Genesis: Critical Edition of the Hebrew Text printed in colours exhibiting the composite structure of the book, with Notes (1896). See SBOT. |

| Ben[nett] | William Henry Bennett, Genesis (Century Bible). |

| Calv[in] | Mosis Libri V cum Johannis Calvini Commentariis. Genesis seorsum, etc. (1563). |

| De[litzsch] | Franz Delitzsch, Neuer Commentar über die Genesis (5th edition, 1887). |

| Di[llmann] | Die Genesis. Von der dritten Auflage an erklärt von August Dillmann (6th edition, 1892). The work embodies frequent extracts from earlier editions by Knobel: these are referred to below as “Knobel-Dillmann” |

| Dr[iver] | The Book of Genesis with Introduction and Notes, by Samuel Rolles Driver (7th edition, 1909). |

| Gu[nkel] | Genesis übersetzt und erklärt, von Hermann Gunkel (2nd edition, 1902). |

| Ho[lzinger] | Genesis erklärt, von Heinrich Holzinger (1898). |

| IEz. | Abraham Ibn Ezra († circa 1167). |

| Jer[ome], Qu. | Jerome († 420), Quæstiones sive Traditiones hebraicæ in Genesim. |

| Kn[obel] | August Wilhelm Knobel. |

| Kn.-Di. | See Dillmann. |

| Ra[shi] | Rabbi Shelomoh Yiẓḥaḳi († 1105). |

| Spurrell | George James Spurrell, Notes on the Text of the Book of Genesis (2nd edition, 1896). |

| Str[ack] | Die Genesis übersetzt und ausgelegt, von Hermann Leberecht Strack (2nd edition, 1905). |

| Tu[ch] | Friedrich Tuch, Commentar über die Genesis (2nd edition, 1871). |

3. WORKS OF REFERENCE AND GENERAL LITERATURE.

| Barth, ES | Jakob Barth, Etymologische Studien zum semitischen insbesondere zum hebraischen Lexicon (1893). |

| Barth, NB | Die Nominalbildung in den semitischen Sprachen (1889‒91). |

| Barton, SO | George Aaron Barton, A Sketch of Semitic Origins (1902). |

| B.-D. | Seligmann Baer and Franz Delitzsch, Liber Genesis (1869). The Massoretic Text, with Appendices. |

| BDB | Francis Brown, Samuel Rolles Driver, and Charles Augustus Briggs, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament (1891‒ ). |

| Benz[inger], Arch.² | Immanuel Benzinger, Hebräische Archäologie (2nd edition, 1907). |

| Ber. R. | The Midrash Bereshith Rabba (translated into German by August Wünsche, 1881). |

| Bochart, Hieroz. | Samuel Bochartus, Hierozoicon, sive bipertitum opus de animalibus Sacræ Scripturæ (edited by Rosenmüller, 1793‒96). |

| Bu[dde], Urg. | Karl Budde, Die biblische Urgeschichte (1883). |

| Buhl, GP | Frants Buhl, Geographie des alten Palaestina (1896). |

| Buhl | Geschichte der Edomiter (1893). |

| Burck[hardt] | John Lewis Burckhardt, Notes on the Bedouins and Wahábys. |

| Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. | |

| Che[yne], TB[A]I | Thomas Kelly Cheyne, Traditions and Beliefs of Ancient Israel (1907). |

| CIS | Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum (1881‒ ). |

| Cook, Gl. | Stanley Arthur Cook, A Glossary of the Aramaic Inscriptions (1898). |

| Cooke, NSI | George Albert Cooke, A Textbook of North-Semitic Inscriptions (1903). |

| Co[rnill], Einl. | Carl Heinrich Cornill, Einleitung in das Alte Testament (see page xl, note). |

| Co[rnill], Hist. | History of the People of Israel (Translated, 1898). |

| Curtiss, PSR | Samuel Ives Curtiss, Primitive Semitic Religion to-day (1902). |

| Dav[idson] | Andrew Bruce Davidson, Hebrew Syntax. |

| Dav[idson] OTTh. | The Theology of the Old Testament (1904). |

| DB | A Dictionary of the Bible, edited by James Hastings (1898‒1902). |

| Del[itzsch], Hwb. | Friedrich Delitzsch, Assyrisches Handwörterbuch (1896). |

| Del[itzsch], Par. | Wo lag das Paradies? Eine biblisch-assyriologische Studie (1881). |

| Del[itzsch], Prol. | Prolegomena eines neuen hebräisch-aramäischen Wörterbuchs zum Alten Testament (1886). |

| Del[itzsch] | See BA below. |

| Doughty, AD | Charles Montagu Doughty, Travels in Arabia Deserta (1888). |

| Dri[ver], LOT | Samuel Rolles Driver, An Introduction to the Literature of the Old Testament (Revised edition, 1910). |

| Dri[ver], Sam. | Notes on the Hebrew Text of the Books of Samuel (1890). |

| Dri[ver], T. | A Treatise on the use of the Tenses in Hebrew (3rd edition, 1892). |

| EB | Encyclopædia Biblica, edited by Thomas Kelly Cheyne and John Sutherland Black (1899‒1903). |

| EBL | See Hilprecht. |

| Ee[rdmans] |

Bernardus Dirk Eerdmans, Alttestamentliche Studien: i. Die Komposition der Genesis. ii. Die Vorgeschichte Israels. |

| Erman, LAE | Adolf Erman, Life in Ancient Egypt (translated by Helen Mary Tirard, 1894). |

| Erman, Hdbk. | A Handbook of Egyptian Religion (translated by Agnes Sophia Griffith, 1907). |

| Ew[ald], Gr. | Heinrich Ewald, Ausführliches Lehrbuch der hebräischen Sprache des alten Bundes (8th edition, 1870). |

| Ew[ald], HI | History of Israel [English translation, 1871]. |

| Ew[ald], Ant. | Antiquities of Israel [English translation, 1876]. |

| Field | Frederick Field, Origenis Hexaplorum quæ supersunt; sive Veterum Interpretum Græcorum in totum Vetus Testamentum Fragmenta (1875). |

| Frazer, AAO | James George Frazer, Adonis Attis Osiris: Studies in the history of Oriental Religion (1906). |

| Frazer, GB | The Golden Bough; a Study in Magic and Religion (2nd edition, 1900). |

| Frazer | Folklore in the Old Testament (1907). |

| v. Gall, CSt. | August Freiherr von Gall, Altisraelitische Kultstätten (1898). |

| G.-B. | Wilhelm Gesenius’ Hebräisches und aramäisches Handwörterbuch über das Alte Testament (14th edition by Buhl, 1905). |

| Geiger, Urschr. | Abraham Geiger, Urschrift und Uebersetzungen der Bibel in ihrer Abhängigkeit von der innern Entwickelung des Judenthums (1857). |

| Ges[enius], Th. | Wilhelm Gesenius, Thesaurus philologicus criticus Linguæ Hebrææ et Chaldææ Veteris Testamenti (1829‒58). |

| G.-K. | Wilhelm Gesenius’ Hebräische Grammatik, völlig umgearbeitet von Emil Kautzsch (26th edition, 1896) [English translation, 1898]. |

| Glaser, Skizze | Eduard Glaser, Skizze der Geschichte und Geographie Arabiens, ii. (1890). |

| Gordon, ETG | Alexander Reid Gordon, The Early Traditions of Genesis (1907). |

| Gray, HPN | George Buchanan Gray, Studies in Hebrew Proper Names (1896). |

| Gu[nkel], Schöpf. | Hermann Gunkel, Schöpfung und Chaos in Urzeit und Endzeit (1895). |

| Guthe, GI | Hermann Guthe, Geschichte des Volkes Israel (1899). |

| Harrison, Prol. | Jane Ellen Harrison, Prolegomena to the study of Greek Religion (2nd edition, 1908). |

| Hilprecht, EBL | Hermann Vollrat Hilprecht, Explorations in Bible Lands during the 19th century [with the co-operation of Benzinger, Hommel, Jensen, and Steindorff] (1903). |

| Ho[lzinger], Einl. or Hex. |

Heinrich Holzinger, Einleitung in den Hexateuch (1893). |

| Hom[mel], AA | Fritz Hommel, Aufsätze und Abhandlungen arabistisch-semitologischen Inhalts (i‒iii, 1892‒ ). |

| Hom[mel], AHT | The Ancient Hebrew Tradition as illustrated by the Monuments (1897). |

| Hom[mel], AOD | Die altorientalischen Denkmäler und das Alte Testament (1902). |

| Hom[mel], Gesch. | Geschichte Babyloniens und Assyriens (1885). |

| Hom[mel], SA Chrest. | Süd-arabische Chrestomathie (1893). |

| Hupf[eld], Qu. | Hermann Hupfeld, Die Quellen der Genesis und die Art ihrer Zusammensetzung (1853). |

| Jastrow, RBA | Morris Jastrow, The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria (1898). |

| JE | The Jewish Encyclopædia. |

| Je[remias], ATLO² | Alfred Jeremias, Das Alte Testament im Lichte des alten Orients (2nd edition, 1906). |

| Jen[sen], Kosm. | Peter Jensen, Die Kosmologie der Babylonier (1890). |

| KAT² | Die Keilinschriften und das Alte Testament, by Schrader (2nd edition, 1883). |

| KAT3 | Die Keilinschriften und das Alte Testament. Third edition, by Zimmern and Winckler (1902). |

| Kent, SOT | Charles Foster Kent, Narratives of the Beginnings of Hebrew History [Students’ Old Testament] (1904). |

| KIB | Keilinschriftliche Bibliothek, edited by Eberhard Schrader (1889‒ ). |

| Kit[tel], BH | Rudolf Kittel, Biblia Hebraica (Genesis) (1905). |

| Kit[tel], GH | Geschichte der Hebräer (1888‒92). |

| Kön[ig], Lgb. | Friedrich Eduard König, Historisch-kritisches Lehrgebäude der hebräischen Sprache (2 volumes, 1881‒95). |

| Kön[ig], S | Historisch-comparative Syntax der hebräischen Sprache (1897). |

| KS | Emil Kautzsch and Albert Socin, Die Genesis mit aüsserer Unterscheidung der Quellenschriften. |

| Kue[nen], Ges. Abh. | Abraham Kuenen, Gesammelte Abhandlungen (see page xl, note). |

| Kue[nen], Ond. | Historisch-critisch Onderzoek naar het ontstaan en de verzameling van de boeken des Ouden Verbonds (see page xl, note). |

| Lag[arde], Ank. | Paul Anton de Lagarde, Ankündigung einer neuen Ausgabe der griech. Uebersezung des Alte Testament (1882). |

| Lag[arde], Ges. Abh. | Gesammelte Abhandlungen (1866). |

| Lag[arde], Mitth. | Mittheilungen, i‒iv (1884‒91). |

| Lag[arde] | Orientalia, 1, 2 (1879‒80). |

| Lag[arde], Sem. | Semitica, 1, 2 (1878). |

| Lag[arde], Symm. | Symmicta, 2 parts (1877‒80). |

| Lag[arde], OS | Onomastica Sacra (1870). |

| Lane, Lex. | Edward William Lane, An Arabic-English Lexicon (1863‒93). |

| Lane, ME | An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (5th edition, 1860). |

| Len[ormant], Or. | François Lenormant, Les Origines de l’histoire, (i‒iii, 1880‒84). |

| Levy, Ch. Wb. | Jacob Levy, Chaldäisches Wörterbuch über die Targumim und Midraschim (3rd edition, 1881). |

| Lidz[barski], Hb. or NSEpigr. | Mark Lidzbarski, Handbuch der nordsemitischen Epigraphik (1898). |

| Lu[ther], INS | See Meyer, INS. |

| Marquart | Josef Marquart, Fundamente israelitischer und jüdischer Geschichte (1896). |

| Meyer, Entst. | Eduard Meyer, Die Entstehung des Judenthums (1896). |

| Meyer, GA¹ | Geschichte des Alterthums (Band i. 1884). |

| Meyer, GA² | Geschichte des Alterthums (2nd edition, 1909). |

| Meyer, INS | Die Israeliten und ihre Nachbarstämme, von Eduard Meyer, mit Beiträgen von Bernhard Luther (1906). |

| Müller, AE | Wilhelm Max Müller, Asien und Europa nach altägyptischen Denkmälern (1893). |

| Nestle, MM | Eberhard Nestle, Marginalien und Materialien (1893). |

| Nö[ldeke], Beitr. | Theodor Nöldeke, Beiträge zur semitischen Sprachwissenschaft (1904). |

| Nö[ldeke], Unters. | Untersuchungen zur Kritik des Alte Testament (1869). |

| OH | Oxford Hexateuch = Carpenter and Harford-Battersby, The Hexateuch (see page xl, note). |

| Oehler, ATTh | Gustav Friedrich Oehler, Theologie des Alten Testaments (3rd edition, 1891). |

| Ols. | Justus Olshausen. |

| Orr, POT | James Orr, The Problem of the Old Testament (1906). |

| OS | See Lagarde. |

| P[ayne] Sm[ith], Thes. | Robert Payne Smith, Thesaurus Syriacus (1879, 1901). |

| Petrie | William Flinders Petrie, A History of Egypt. |

| Pro[cksch] | Otto Procksch, Das nordhebräische Sagenbuch: die Elohimquelle (1906). |

| Riehm, Hdwb. | Eduard Carl August Riehm, Handwörterbuch des biblischen Altertums (2nd edition, 1893‒94). |

| Robinson, BR | Edward Robinson, Biblical Researches in Palestine (2nd edition, 3 volumes, 1856). |

| Sayce, EHH | Archibald Henry Sayce, The Early History of the Hebrews (1897). |

| Sayce, HCM | The Higher Criticism and the Verdict of the Monuments (2nd edition, 1894). |

| SBOT | The Sacred Books of the Old Testament, a critical edition of the Hebrew Text printed in Colours, under the editorial direction of Paul Haupt. |

| Schenkel, BL | Daniel Schenkel, Bibel-Lexicon (1869‒75). |

| Schr[ader], KGF | Eberhard Schrader, Keilinschriften und Geschichtsforschung (1878). |

| Schr[ader] | See KAT and KIB above. |

| Schultz, OTTh | Hermann Schultz, Old Testament Theology (English translation, 1892). |

| Schürer, GJV | Emil Schürer, Geschichte des jüdischen Volkes im Zeitalter Jesu Christi (3rd and 4th editions, 1898‒1901). |

| Schw[ally] | Friedrich Schwally, Das Leben nach dem Tode (1892). |

| Semitische Kriegsaltertümer, i. (1901). | |

| Smend, ATRG | Rudolf Smend, Lehrbuch der alttestamentlichen Religionsgeschichte (2nd edition, 1899). |

| GASm[ith], HG | George Adam Smith, Historical Geography of the Holy Land (1895). |

| Rob. Smith, KM² | William Robertson Smith, Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia (2nd edition, 1903). |

| Rob. Smith, OTJC² | The Old Testament in the Jewish Church (2nd edition, 1892). |

| Rob. Smith, Pr.² | The Prophets of Israel (2nd edition, 1895). |

| Rob. Smith, RS² | Lectures on the Religion of the Semites (2nd edition, 1894). |

| Spiegelberg | Wilhelm Spiegelberg, Aegyptologische Randglossen zum Alten Testament (1904). |

| Der Aufenthalt Israels in Aegypten im Lichte der aegyptischen Monumente (3rd edition, 1904). | |

| Sta[de] | Bernhard Stade, Ausgewählte akademische Reden und Abhandlungen (1899). |

| Sta[de], BTh | Biblische Theologie des Alten Testaments, i. (1905). |

| Sta[de], GVI | Geschichte des Volkes Israel (1887‒89). |

| Steuern[agel], Einw. | Carl Steuernagel, Die Einwanderung der israelitischen Stämme in Kanaan (1901). |

| TA | Tel-Amarna Tablets [Keilinschriftliche Bibliothek, v; Knudtzon, Die el-Amarna Tafeln (1908‒ )]. |

| Thomson, LB | William McClure Thomson, The Land and the Book (3 volumes, 1881‒86). |

| Tiele, Gesch. | Cornelis Petrus Tiele, Geschichte der Religion im Altertum, i. (German edition, 1896). |

| Tristram, NHB | Henry Baker Tristram, The Natural History of the Bible (9th edition, 1898). |

| We[llhausen], Comp.² | Julius Wellhausen, Die Composition des Hexateuchs und der historischen Bücher des Alten Testaments (2nd edition, 1889). |

| We[llhausen], De gent. | De gentibus et familiis Judæis quæ 1 Chronicles 2. 4 enumerantur (1870). |

| We[llhausen], Heid. | Reste arabischen Heidentums (2nd edition, 1897). |

| We[llhausen], Prol.⁶ | Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (6th edition, 1905). |

| We[llhausen] | Skizzen und Vorarbeiten. |

| We[llhausen], TBS | Der Text der Bücher Samuelis (1871). |

| Wi[nckler], AOF | Hugo Winckler, Altorientalische Forschungen (1893- ). |

| Wi[nckler], ATU | Alttestamentliche Untersuchungen (1892). |

| Wi[nckler], GBA | Geschichte Babyloniens und Assyriens (1892). |

| Wi[nckler], GI | Geschichte Israels in Einzeldarstellungen (i. ii., 1895, 1900). |

| Wi[nckler] | See KAT³ above. |

| Zunz, GdV | Leopold Zunz, Die gottesdienstlichen Vorträge der Juden (2nd edition, 1892). |

4. PERIODICALS, ETC.

| AJSL | American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures (continuing Hebraica). |

| AJTh | American Journal of Theology (1897‒ ). |

| ARW | Archiv für Religionswissenschaft. |

| BA | Beiträge zur Assyriologie und semitischen Sprachwissenschaft, herausgegeben von Friedrich Delitzsch und Paul Haupt (1890‒ ). |

| BS | Bibliotheca Sacra and Theological Review (1844‒ ). |

| Deutsche Litteraturzeitung (1880‒ ). | |

| Exp. | The Expositor. |

| ET | The Expository Times. |

| GGA | Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen (1753— ). |

| GGN | Nachrichten der königl. Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. |

| Hebr. | Hebräica (1884‒95). See AJSL. |

| JBBW | [Ewald’s] Jahrbücher der biblischen Wissenschaft (1849‒1865). |

| J[S]BL | Journal of [the Society of] Biblical Literature and Exegesis (1881‒ ). |

| JPh | The Journal of Philology (1872‒ ). |

| JQR | The Jewish Quarterly Review. |

| JRAS | Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1834‒ ). |

| JTS | The Journal of Theological Studies (1900‒ ). |

| Lit[erarisches] Zentralbl[att für Deutschland] (1850‒ ). | |

| M[B]BA | Monatsberichte der Königlich-Preussischen Akadamie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. Continued in Sitzungsberichte der Königlich-Preussischen Akadamie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (1881‒ ). |

| MVAG | Mittheilungen der vorderasiatischen Gesellschaft (1896‒ ). |

| NKZ | Neue kirchliche Zeitschrift (1890‒ ). |

| OLz | Orientalische Litteraturzeitung (1898‒ ). |

| PAOS | Proceedings [Journal] of the American Oriental Society (1851‒ ). |

| PEFS | Palestine Exploration Fund: Quarterly Statements. |

| PSBA | Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archæology (1878‒ ). |

| SBBA | See MBBA above. |

| SK | Theologische Studien und Kritiken (1828‒ ). |

| ThLz | Theologische Litteraturzeitung (1876‒ ). |

| ThT | Theologisch Tijdschrift (1867‒ ). |

| TSBA | Transactions of the Society of Biblical Archæology. |

| ZA | Zeitschrift für Assyriologie (1886‒ ). |

| ZATW | Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft (1881‒ ). |

| ZDMG | Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft (1845‒ ). |

| ZDPV | Zeitschrift des deutschen Palästina-Vereins (1878‒ ). |

| ZKF | Zeitschrift für Keilschriftsforschung (1884‒85). |

| ZVP | Zeitschrift für Völkerpsychologie und Sprachwissenschaft (1860‒ ). |

5. OTHER SIGNS AND CONTRACTIONS.

| NH | ‘New Hebrew’: the language of the Mishnah, Midrashim, and parts of the Talmud. | |

| v.i. | vide infra | Used in references from commentary to footnotes, and vice versâ. |

| v.s. | vide supra | |

| * | Frequently used to indicate that a section is of composite authorship. | |

| † | After Old Testament references means that all occurrences of the word or usage in question are cited. | |

| √ | Root or stem. | |

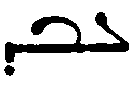

| ׳ | Sign of abbreviation in Hebrew words. | |

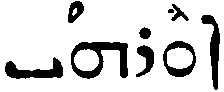

| וגו׳ | = וגומר = ‘and so on’: used when a Hebrew citation is incomplete. | |

The Book of Genesis (on the title see at the end of this §) forms the opening section of a comprehensive historical work which, in the Hebrew Bible, extends from the creation of the world to the middle of the Babylonian Exile (2 Kings 25³⁰). The tripartite division of the Jewish Canon has severed the later portion of this work (Joshua‒Kings), under the title of the “Former Prophets” (הנביאים הראשונים), from the earlier portion (Genesis‒Deuteronomy), which constitutes the Law (התורה),—a seemingly artificial bisection which results from the Tôrāh having attained canonical authority soon after its completion in the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, while the canonicity of the Prophetical scriptures was not recognised till some centuries later.¹ How soon the division of the Tôrāh into its five books (חמשה חומשי התורה: ‘the five fifths of the Law’) was introduced we do not know for certain; but it is undoubtedly ancient, and in all probability is due to the final redactors of the Pentateuch.² In the case of Genesis, at all events, the division is obviously appropriate. Four centuries of complete silence lie between its close and the beginning of Exodus, where we enter on the history of a nation as contrasted with that of a family; and its prevailing character of individual biography suggests that its traditions are of a different quality, and have a different origin, from the national traditions preserved in Exodus and the succeeding books. Be that as it may, Genesis is a unique and well-rounded whole; and there is no book of the Pentateuch, except Deuteronomy, which so readily lends itself to monographic treatment.

Genesis may thus be described as the Book of Hebrew Origins. It is a peculiarity of the Pentateuch that it is Law-book and history in one: while its main purpose is legislative, the laws are set in a framework of narrative, and so, as it were, are woven into the texture of the nation’s life. Genesis contains a minimum of legislation; but its narrative is the indispensable prelude to that account of Israel’s formative period in which the fundamental institutions of the theocracy are embedded. It is a collection of traditions regarding the immediate ancestors of the Hebrew nation (chapters 12‒50), showing how they were gradually isolated from other nations and became a separate people; and at the same time how they were related to those tribes and races most nearly connected with them. But this is preceded (in chapters 1‒11) by an account of the origin of the world, the beginnings of human history and civilisation, and the distribution of the various races of mankind. The whole thus converges steadily on the line of descent from which Israel sprang, and which determined its providential position among the nations of the world. It is significant, as already observed, that the narrative stops short just at the point where family history ceases with the death of Joseph, to give place after a long interval to the history of the nation.

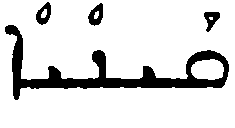

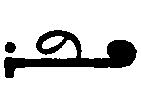

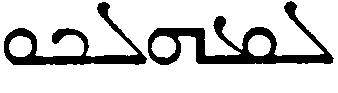

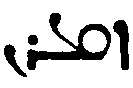

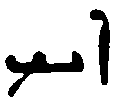

The Title.—The name ‘Genesis’ comes to us through the Vulgate from the LXX, where the usual superscription is simply Γένεσις (LXXEM, most cursives), rarely ἡ γένεσις (LXX⁷²), a contraction of Γένεσις κόσμου (LXXA, 121). An interesting variation in one cursives. (129)—ἡ βίβλος τῶν γενέσεων (compare 2⁴ 5¹)¹—might tempt one to fancy that the scribe had in view the series of Tôlĕdôth (see page xxxiv), and regarded the book as the book of origins in the wide sense expressed above. But there is no doubt that the current Greek title is derived from the opening theme of the book, the creation of the world.²—So also in Syriac (sephrå dabrīthå), Theodore of Mopsuestia (ἡ κτίσις), and occasionally among the Rabbis (ספר יצירה).—The common Jewish designation is בראשית, after the first word of the book (Origen, in Eusebius Church History, vi. 25; Jerome, Prologus Galeatus, and Questions on Genesis); less usual is חומש ראשון, ‘the first fifth.’—Only a curious interest attaches to the unofficial appellation ספר הישר (based on 2 Samuel 1¹⁸) or ס׳ הישרים (the patriarchs) see Carpzov, Introductio in libros canonicos bibliorum Veteris Testamenti page 55; Delitzsch, 10.

The first question that arises with regard to these ‘origins’ is whether they are in the main of the nature of history or of legend,—whether (to use the expressive German terms) they are Geschichte, things that happened, or Sage, things said. There are certain broad differences between these two kinds of narrative which may assist us to determine to which class the traditions of Genesis belong.

History in the technical sense is an authentic record of actual events based on documents contemporary, or nearly contemporary, with the facts narrated. It concerns itself with affairs of state and of public interest,—with the actions of kings and statesmen, civil and foreign wars, national disasters and successes, and such like. If it deals with contemporary incidents, it consciously aims at transmitting to posterity as accurate a reflexion as possible of the real course of events, in their causal sequence, and their relations to time and place. If written at a distance from the events, it seeks to recover from contemporary authorities an exact knowledge of these circumstances, and of the character and motives of the leading personages of the action.—That the Israelites, from a very early period, knew how to write history in this sense, we see from the story of David’s court in 2 Samuel and the beginning of 1 Kings. There we have a graphic and circumstantial narrative of the struggles for the succession to the throne, free from bias or exaggeration, and told with a convincing realism which conveys the impression of first-hand information derived from the evidence of eye-witnesses. As a specimen of pure historical literature (as distinguished from mere annals or chronicles) there is nothing equal to it in antiquity, till we come down to the works of Herodotus and Thucydides in Greece.

Quite different from historical writing of this kind is the Volkssage,—the mass of popular narrative talk about the past, which exists in more or less profusion amongst all races in the world. Every nation, as it emerges into historical consciousness, finds itself in possession of a store of traditional material of this kind, either circulating among the common people, or woven by poets and singers into a picture of a legendary heroic age. Such legends, though they survive the dawn of authentic history, belong essentially to a pre-literary and uncritical stage of society, when the popular imagination works freely on dim reminiscences of the great events and personalities of the past, producing an amalgam in which tradition and phantasy are inseparably mingled. Ultimately they are themselves reduced to writing, and give rise to a species of literature which is frequently mistaken for history, but whose true character will usually disclose itself to a patient and sympathetic examination. While legend is not history, it has in some respects a value greater than history. For it reveals the soul of a people, its instinctive selection of the types of character which represent its moral aspirations, its conception of its own place and mission in the world; and also, to some indeterminate extent, the impact on its inner life of the momentous historic experiences in which it first woke up to the consciousness of a national existence and destiny.¹

In raising the question to which department of literature the narratives of Genesis are to be referred, we approach a subject beset by difficulty, but one which cannot be avoided. We are not entitled to assume a priori that Israel is an exception to the general rule that a legendary age forms the ideal background of history: whether it be so or not must be determined on the evidence of its records. Should it prove to be no exception, we shall not assign to its legends a lower significance as an expression of the national spirit than to the heroic legends of the Greek or Teutonic races. It is no question of the truth or religious value of the book that we are called to discuss, but only of the kind of truth and the particular mode of revelation which we are to find in it. One of the strangest theological prepossessions is that which identifies revealed truth with matter-of-fact accuracy either in science or in history. Legend is after all a species of poetry, and it is hard to see why a revelation which has freely availed itself of so many other kinds of poetry—fable, allegory, parable—should disdain that form of it which is the most influential of all in the life of a primitive people. As a vehicle of religious ideas, poetic narrative possesses obvious advantages over literal history; and the spirit of religion, deeply implanted in the heart of a people, will so permeate and fashion its legendary lore as to make it a plastic expression of the imperishable truths which have come to it through its experience of God.

The legendary aspect of the Genesis traditions appears in such characteristics as these: (1) The narratives are the literary deposit of an oral tradition which, if it rests on any substratum of historic fact, must have been carried down through many centuries. Few will seriously maintain that the patriarchs prepared written memoranda for the information of their descendants; and the narrators nowhere profess their indebtedness to such records. Hebrew historians freely refer to written authorities where they used them (Kings, Chronicles); but no instance of this practice occurs in Genesis. Now oral tradition is the natural vehicle of popular legend, as writing is of history. And all experience shows that apart from written records there is no exact knowledge of a remote past. Making every allowance for the superior retentiveness of the Oriental memory, it is still impossible to suppose that an accurate recollection of bygone incidents should have survived twenty generations or more of oral transmission. Nöldeke, indeed, has shown that the historical memory of the pre-Islamic Arabs was so defective that all knowledge of great nations like the Nabatæans and Thamudites had been lost within two or three centuries.¹ (2) The literary quality of the narratives stamps them as products of the artistic imagination. The very picturesqueness and truth to life which are sometimes appealed to in proof of their historicity are, on the contrary, characteristic marks of legend (Dillmann, 218). We may assume that the scene at the well of Ḥarran (chapte 24) actually took place; but that the description owes its graphic power to a reproduction of the exact words spoken and the precise actions performed on the occasion cannot be supposed; it is due to the revivifying work of the imagination of successive narrators. But imagination, uncontrolled by the critical faculty, does not confine itself to restoring the original colours of a faded picture; it introduces new colours, insensibly modifying the picture till it becomes impossible to tell how much belongs to the real situation and how much to later fancy. The clearest proof of this is the existence of parallel narratives of an event which can only have happened once, but which emerges in tradition in forms so diverse that they may even pass for separate incidents (1210 ff. ∥ 201 ff. ∥ 266 ff.; 16. ∥ 218 ff.; 15. ∥ 17, etc.).—(3) The subject-matter of the tradition is of the kind congenial to the folk-tale all the world over, and altogether different from transactions on the stage of history. The proper theme of history, as has been said, is great public and political events; but legend delights in genre pictures, private and personal affairs, trivial anecdotes of domestic and everyday life, and so forth,—matters which interest the common people and come home to their daily experience. That most of the stories of Genesis are of this description needs no proof; and the fact is very instructive.² A real history of the patriarchal period would have to tell of migrations of peoples, of religious movements, probably of wars of invasion and conquest; and accordingly most modern attempts to vindicate the historicity of Genesis proceed by way of translating the narratives into such terms as these. But this is to confess that the narratives themselves are not history. They have been simplified and idealised to suit the taste of an unsophisticated audience; and in the process the strictly historic element, down to a bare residuum, has evaporated. The single passage which preserves the ostensible appearance of history in this respect is chapter 14; and that chapter, which in any case stands outside the circle of patriarchal tradition, has difficulties of its own which cannot be dealt with here (see page 271 ff.).—(4) The final test—though to any one who has learned to appreciate the spirit of the narratives it must seem almost brutal to apply it—is the hard matter-of-fact test of self-consistency and credibility. It is not difficult to show that Genesis relates incredibilities which no reasonable appeal to miracle will suffice to remove. With respect to the origin of the world, the antiquity of man on the earth, the distribution and relations of peoples, the beginnings of civilisation, etc., its statements are at variance with the scientific knowledge of our time;³ and no person of educated intelligence accepts them in their plain natural sense. We know that angels do not cohabit with mortal women, that the Flood did not cover the highest mountains of the world, that the ark could not have accommodated all the species of animals then existing, that the Euphrates and Tigris have not a common source, that the Dead Sea was not first formed in the time of Abraham, etc. There is admittedly a great difference in respect of credibility between the primæval (chapters 1‒11) and the patriarchal (12‒50) traditions. But even the latter, when taken as a whole, yields many impossible situations. Sarah was more than sixty-five years old when Abraham feared that her beauty might endanger his life in Egypt; she was over ninety when the same fear seized him in Gerar. Abraham at the age of ninety-nine laughs at the idea of having a son; yet forty years later he marries and begets children. Both Midian and Ishmael were grand-uncles of Joseph; but their descendants appear as tribes trading with Egypt in his boyhood. Amalek was a grandson of Esau; yet the Amalekites are settled in the Negeb in the time of Abraham.⁴—It is a thankless task to multiply such examples. The contradictions and violations of probability and scientific possibility are intelligible, and not at all disquieting, in a collection of legends; but they preclude the supposition that Genesis is literal history.

It is not implied in what has been said that the tradition is destitute of historical value. History, legendary history, legend, myth, form a descending scale, with decreasing emphasis on the historical element, and the lines between the first three are vague and fluctuating. In what proportions they are combined in Genesis it may be impossible to determine with certainty. But there are three ways in which a tradition mainly legendary may yield solid historical results. In the first place, a legend may embody a more or less exact recollection of the fact in which it originated. In the second place, a legend, though unhistorical in form, may furnish material from which history can be extracted. Thirdly, the collateral evidence of archæology may bring to light a correspondence which gives a historical significance to the legend. How far any of these lines can be followed to a successful issue in the case of Genesis, we shall consider later (§ 4), after we have examined the obviously legendary motives which enter into the tradition. Meanwhile the previous discussion will have served its purpose if any readers have been led to perceive that the religious teaching of Genesis lies precisely in that legendary element whose existence is here maintained. Our chief task is to discover the meaning of the legends as they stand, being assured that from the nature of the case these religious ideas were operative forces in the life of ancient Israel. It is a suicidal error in exegesis to suppose that the permanent value of the book lies in the residuum of historic fact that underlies the poetic and imaginative form of the narratives.¹

1. Are there myths in Genesis, as well as legends? On this question there has been all the variety of opinion that might be expected. Some writers, starting with the theory that mythology is a necessary phase of primitive thinking, have found in the Old Testament abundant confirmation of their thesis.¹ The more prevalent view has been that the mythopœic tendency was suppressed in Israel by the genius of its religion, and that mythology in the true sense is unknown in its literature. Others have taken up an intermediate position, denying that the Hebrew mind produced myths of its own, but admitting that it borrowed and adapted those of other peoples. For all practical purposes, the last view seems to be very near the truth.

For attempts to discriminate between myth and legend, see Tuch, pages I‒XV; Gunkel, page XVII; Höffding, Philosophy of Religion (Engish translation), 199 ff.; Gordon, 77 ff.; Procksch, Das nordhebräische Sagenbuch, I. etc.—The practically important distinction is that the legend does, and the myth does not, start from the plane of historic fact. The myth is properly a story of the gods, originating in an impression produced on the primitive mind by the more imposing phenomena of nature, while legend attaches itself to the personages and movements of real history. Thus the Flood-story is a legend if Noah be a historical figure, and the kernel of the narrative an actual event; it is a myth if it be based on observation of a solar phenomenon, and Noah a representative of the sun-god (see page 180 f.). But the utility of this distinction is largely neutralised by a universal tendency to transfer mythical traits from gods to real men (Sargon of Agadé, Moses, Alexander, Charlemagne, etc.); so that the most indubitable traces of mythology will not of themselves warrant the conclusion that the hero is not a historical personage.—Gordon differentiates between spontaneous (nature) myths and reflective (ætiological) myths; and, while recognising the existence of the latter in Genesis, considers that the former type is hardly represented in the Old Testament at all. The distinction is important, though it may be doubted if ætiology is ever a primary impulse to the formation of myths, and as a parasitic development it appears to attach itself indifferently to myth and legend. Hence there is a large class of narratives which it is difficult to label either as mythical or as legendary, but in which the ætiological or some similar motive is prominent (see page xi ff.).

2. The influence of foreign mythology is most apparent in the primitive traditions of chapters 1‒11. The discovery of the Babylonian versions of the Creation- and Deluge-traditions has put it beyond reasonable doubt that these are the originals from which the biblical accounts have been derived (pages 45 ff., 177 f.). A similar relation obtains between the antediluvian genealogy of chapter 5 and Berossus’s list of the ten Babylonian kings who reigned before the Flood (page 137 f.). The story of Paradise has its nearest analogies in Iranian mythology; but there are faint Babylonian echoes which suggest that it belonged to the common mythological heritage of the East (page 90 ff.). Both here and in chapter 4 a few isolated coincidences with Phœnician tradition may point to the Canaanite civilisation as the medium through which such myths came to the knowledge of the Israelites.—All these (as well as the story of the Tower of Babel) were originally genuine myths—stories of the gods; and if they no longer deserve that appellation, it is because the spirit of Hebrew monotheism has exorcised the polytheistic notions of deity, apart from which true mythology cannot survive. The few passages where the old heathen conception of godhead still appears (1²⁶ 322. 24 61 ff. 111 ff.), only serve to show how completely the religious beliefs of Israel have transformed and purified the crude speculations of pagan theology, and adapted them to the ideas of an ethical and monotheistic faith.

The naturalisation of Babylonian myths in Israel is conceivable in a variety of ways; and the question is perhaps more interesting as an illustration of two rival tendencies in criticism than for its possibilities of actual solution. The tendency of the literary school of critics has been to explain the process by the direct use of Babylonian documents, and to bring it down to near the dates of our written Pentateuch sources.¹ Largely through the influence of Gunkel, a different view has come to prevail, viz., that we are to think rather of a gradual process of assimilation to the religious ideas of Israel in the course of oral transmission, the myths having first passed into Canaanite tradition as the result (immediate or remote) of the Babylonian supremacy prior to the Tell-Amarna period, and thence to the Israelites.² The strongest argument for this theory is that the biblical versions, both of the Creation and the Flood, give evidence of having passed through several stages in Hebrew tradition. Apart from that, the considerations urged in support of either theory do not seem to me conclusive. There are no recognisable traces of a specifically Canaanite medium having been interposed between the Babylonian originals and the Hebrew accounts of the Creation and the Flood, such as we may surmise in the case of the Paradise myth. It is open to argue against Gunkel that if the process had been as protracted as he says, the divergence would be much greater than it actually is. Again, we cannot well set limits to the deliberate manipulation of Babylonian material by a Hebrew writer; and the assumption that such a writer in the later period would have been repelled by the gross polytheism of the Babylonian legends, and refused to have anything to do with them, is a little gratuitous. On the other hand, it is unsafe to assert with Stade that the myths could not have been assimilated by Israelite theology before the belief in Yahwe’s sole deity had been firmly established by the teaching of the prophets. Monotheism had roots in Hebrew antiquity extending much further back than the age of written prophecy, and the present form of the legends is more intelligible as the product of an earlier phase of religion than that of the literary prophets. But when we consider the innumerable channels through which myths may wander from one centre to another, we shall hardly expect to be able to determine the precise channel, or the approximate date, of this infusion of Babylonian elements into the religious tradition of Israel.

It is remarkable that while the patriarchal legends exhibit no traces of Babylonian mythology, they contain a few examples of mythical narrative to which analogies are found in other quarters. The visit of the angels to Abraham (see page 302 f.), and the destruction of Sodom (page 311 f.), are incidents of obviously mythical origin (stories of the gods); and to both, classical and other parallels exist. The account of the births of Esau and Jacob embodies a mythological motive (page 359), which is repeated in the case of Zeraḥ and Pereẓ (chapter 38). The whole story of Jacob and Esau presents several points of contact with that of the brothers Hypsouranios (Šamem-rum) and Usōos in the Phœnician mythology (Usōos = Esau: see pages 360, 124). There appears also to be a Homeric variant of the incest of Reuben (page 427). These phenomena are among the most perplexing which we encounter in the study of Hebrew tradition.¹ We can as yet scarcely conjecture the hidden source from which such widely ramified traditions have sprung, though we may not on that account ignore the existence of the problem. It would be at all events a groundless anticipation that the facts will lead us to resolve the patriarchs into mythological abstractions. They are rather to be explained by the tendency already referred to (page ix), to mingle myth with legend by transferring mythical incidents to historic personages.

3. It remains, before we go on to consider the historical elements of the tradition, to classify the leading types of mythical, or semi-mythical (page ix), motive which appear in the narratives of Genesis. It will be seen that while they undoubtedly detract from the literal historicity of the records, they represent points of view which are of the greatest historical interest, and are absolutely essential to the right interpretation of the legends.¹

(a) The most comprehensive category is that of ætiological or explanatory myths; i.e., those which explain some familiar fact of experience by a story of the olden time. Both the questions asked and the answers returned are frequently of the most naïve and childlike description: they have, as Gunkel, Genesis übersetzt und erklärt has said, all the charm which belongs to the artless but profound reasoning of an intelligent child. The classical example is the story of Paradise and the Fall in chapters 2, 3, which contains one explicit instance of ætiology (2²⁴: why a man cleaves to his wife), and implicitly a great many more: why we wear clothes and detest snakes, why the serpent crawls on his belly, why the peasant has to drudge in the fields, and the woman to endure the pangs of travail, etc. (page 95). Similarly, the account of creation explains why there are so many kinds of plants and animals, why man is lord of them all, why the sun shines by day and the moon by night, etc.; why the Sabbath is kept. The Flood-story tells us the meaning of the rainbow, and of the regular recurrence of the seasons: the Babel-myth accounts for the existing diversities of language amongst men. Pure examples of ætiology are practically confined to the first eleven chapters; but the same general idea pervades the patriarchal history, specialised under the headings which follow.

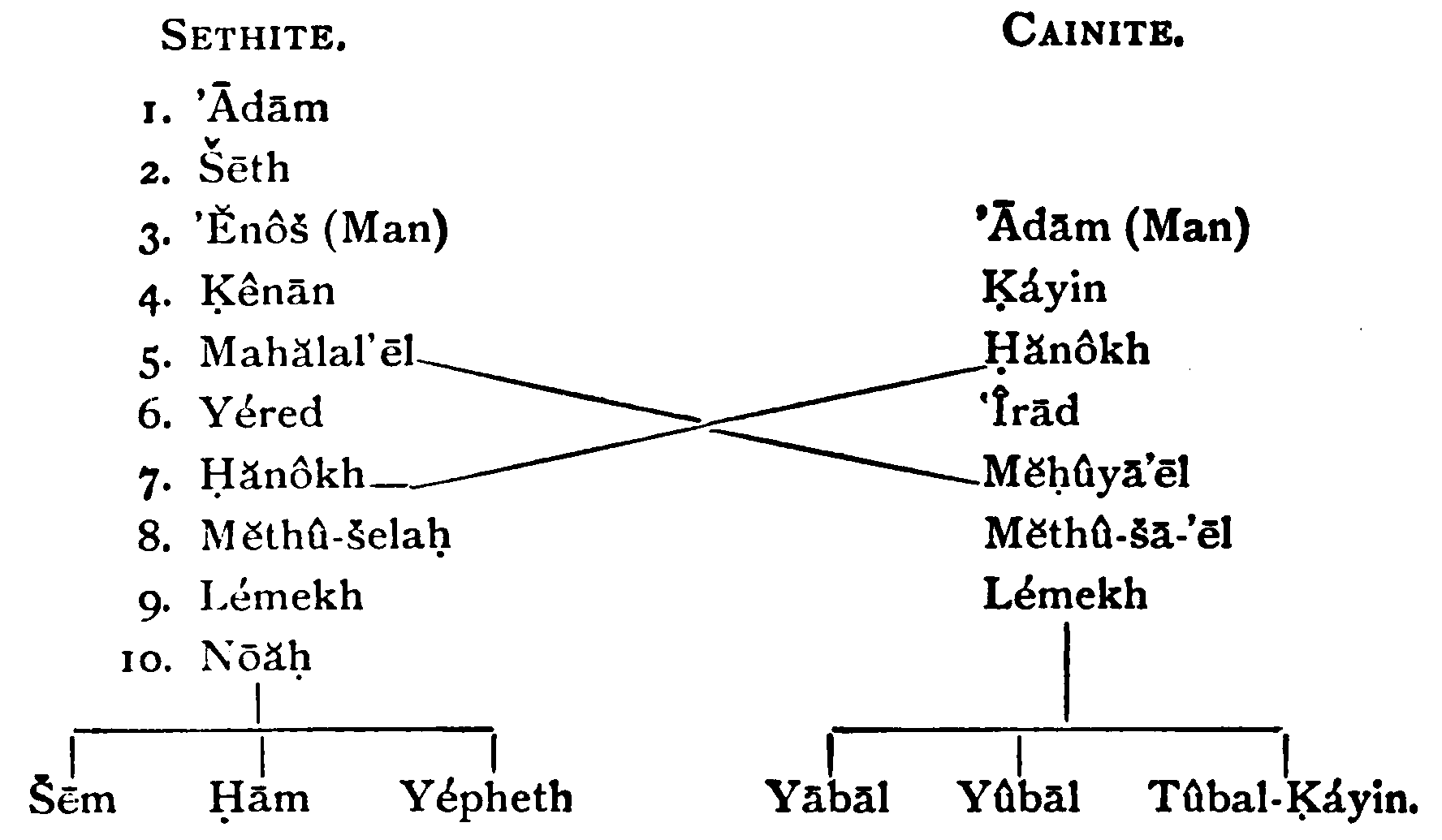

(b) The commonest class of all, especially in the patriarchal narratives, is what may be called ethnographic legends. It is an obvious feature of the narratives that the heroes of them are frequently personifications of tribes and peoples, whose character and history and mutual relationships are exhibited under the guise of individual biography. Thus the pre-natal struggle of Jacob and Esau prefigures the rivalry of ‘two nations’ (25²³); the monuments set up by Jacob and Laban mark the frontier between Israelites and Aramæans (3144 ff.); Ishmael is the prototype of the wild Bedouin (16¹²), and Cain of some ferocious nomad-tribe; Jacob and his twelve sons represent the unity of Israel and its division into twelve tribes; and so on. This mode of thinking was not peculiar to Israel (compare the Hellen, Dorus, Xuthus, Aeolus, Achæus, Ion, of the Greeks);¹ but it is one specially natural to the Semites from their habit of speaking of peoples as sons (i.e. members) of the collective entity denoted by the tribal or national name (sons of Israel, of Ammon, of Ishmael, etc.), whence arose the notion that these entities were the real progenitors of the peoples so designated. That in some cases the representation was correct need not be doubted; for there are known examples, both among the Arabs and other races in a similar stage of social development, of tribes named after a famous ancestor or leader of real historic memory. But that this is the case with all eponymous persons—e.g. that there were really such men as Jerahmeel, Midian, Aram, Sheba, Amalek, and the rest—is quite incredible; and, moreover, it is never true that the fortunes of a tribe are an exact copy of the personal experiences of its reputed ancestor, even if he existed. We must therefore treat these legends as symbolic representations of the ethnological affinities between different tribes or peoples, and (to a less extent) of the historic experiences of these peoples. There is a great danger of driving this interpretation too far, by assigning an ethnological value to details of the legend which never had any such significance; but to this matter we shall have occasion to return at a later point (see page xix ff.).

(c) Next in importance to these ethnographic legends are the cult-legends. A considerable proportion of the patriarchal narratives are designed to explain the sacredness of the principal national sanctuaries, while a few contain notices of the origin of particular ritual customs (circumcision, chapter 17 [but compare Exodus 424 ff.]; the abstinence from eating the sciatic nerve, 32³³). To the former class belong such incidents as Hagar at Lahairoi (16), Abraham at the oak of Mamre (18), his planting of the tamarisk at Beersheba (21³³), Jacob at Bethel—with the reason for anointing the sacred stone, and the institution of the tithe—(2810 ff.), and at Peniel (3224 ff.); and many more. The general idea is that the places were hallowed by an appearance of the deity in the patriarchal period, or at least by the performance of an act of worship (erection of an altar, etc.) by one of the ancestors of Israel. In reality the sanctity of these spots was in many cases of immemorial antiquity, being rooted in the most primitive forms of Semitic religion; and at times the narrative suffers it to appear that the place was holy before the visit of the patriarch (see on 12⁶). It is probable that inauguration-legends had grown up at the chief sanctuaries while they were still in the possession of the Canaanites. We cannot tell how far such legends were transferred to the Hebrew ancestors, and how far the traditions are of native Israelite growth.

(d) Of much less interest to us is the etymological motive which so frequently appears as a side issue in legends of wider scope. ♦Speculation on the meaning and origin of names is fascinating to all primitive peoples; and in default of a scientific philology the most fantastic explanations are readily accepted. That it was so in ancient Israel could be easily shown from the etymologies of Genesis. Here, again, it is just conceivable that the explanation given may occasionally be correct (though there is hardly a case in which it is plausible); but in the majority of cases the real meaning of the name stands out in palpable contradiction to the alleged account of its origin. Moreover, it is not uncommon to find the same name explained in two different ways (many of Jacob’s sons, chapter 30), or to have as many as three suggestions of its historic origin (Ishmael, 16¹¹ 17²⁰ 21¹⁷; Isaac, 17¹⁷ 18¹² 21⁹). To claim literal accuracy for incidents of this kind is manifestly futile.

(e) There is yet another element which, though not mythical or legendary, belongs to the imaginative side of the legends, and has to be taken account of in interpreting them. This is the element of poetic idealisation. Whenever a character enters the world of legend, whether through the gate of history or through that of ethnographic personification, it is apt to be conceived as a type; and as the story passes from mouth to mouth the typical features are emphasised, while those which have no such significance tend to be effaced or forgotten. Then the dramatic instinct comes into play—the artistic desire to perfect the story as a lifelike picture of human nature in interesting situations and action. To see how far this process may be carried, we have but to compare the conception of Jacob’s sons in the Blessing of Jacob (chapter 49) with their appearance in the younger narratives of Joseph and his brethren. In the former case the sons are tribal personifications, and the characters attributed to them are those of the tribes they represent. In the latter, these characteristics have almost entirely disappeared, and the central interest is now the pathos and tragedy of Hebrew family life. Most of the brothers are without character or individuality; but the accursed Reuben and Simeon are respected members of the family, and the ‘wolf’ Benjamin has become a helpless child whom the father will hardly let go from his side. This, no doubt, is the supreme instance of romantic or ‘novelistic’ treatment which the book contains; but the same idealising tendency is at work elsewhere, and must constantly be allowed for in endeavouring to reach the historic or ethnographic basis from which the legends start.

It has already been remarked (page vii) that there are three chief ways in which an oral, and therefore legendary, tradition may yield solid historical results: first, through the retention in the popular memory of the impression caused by real events and personalities; secondly, by the recovery of historic (mainly ethnographic) material from the biographic form of the tradition; and thirdly, through the confirmation of contemporary ‘archæological’ evidence. It will be convenient to start with the last of these, and consider what is known about—

1. The historical background of the patriarchal traditions.—The period covered by the patriarchal narratives¹ may be defined very roughly as the first half of the second millennium (2000‒1500) B.C. The upper limit depends on the generally accepted assumption, based (somewhat insecurely, as it seems to us) on chapter 14, that Abraham was contemporary with Ḫammurabi, the 6th king of the first Babylonian dynasty. The date of Ḫammurabi is probably circa 2100 B.C.² The lower limit is determined by the Exodus, which is usually assigned (as it must be if Exodus 1¹¹ is genuine) to the reign of Merneptah of the Nineteenth Egyptian dynasty (circa 1234‒1214 B.C.). Allowing a sufficient period for the sojourn of Israel in Egypt, we come back to about the middle of the millennium as the approximate time when the family left Palestine for that country. The Hebrew chronology assigns nearly the same date as above to Abraham, but a much earlier one for the Exodus (circa 1490), and reduces the residence of the patriarchs in Canaan to 215 years; since, however, the chronological system rests on artificial calculations (see pages 135 f., 234), we cannot restrict our survey to the narrow limits which it assigns to the patriarchal period in Palestine. Indeed, the chronological uncertainties are so numerous that it is desirable to embrace an even wider field than the five centuries mentioned above.³

In the opinion of a growing and influential school of writers, this period of history has been so illumined by recent discoveries that it is no longer possible to doubt the essential historicity of the patriarchal tradition.¹ It is admitted that no external evidence has come to light of the existence of such persons as Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph, or even (with the partial exception of Joseph) of men playing parts at all corresponding to theirs. But it is maintained that contemporary documents reveal a set of conditions into which the patriarchal narratives fit perfectly, and which are so different from those prevailing under the monarchy that the situation could not possibly have been imagined by an Israelite of that later age. Now, that recent archæology has thrown a flood of light on the period in question, is beyond all doubt. It has proved that Palestinian culture and religion were saturated by Babylonian influences long before the supposed date of Abraham; that from that date downwards intercourse with Egypt was frequent and easy; and that the country was more than once subjected to Egyptian conquest and authority. It has given us a most interesting glimpse from about 2000 B.C. of the natural products of Canaan, and the manner of life of its inhabitants (Tale of Sinuhe). At a later time (Tell-Amarna letters) it shows the Egyptian dominion threatened by the advance of Hittites from the north, and by the incursion of a body of nomadic marauders called Ḫabiri (see page 218). It tells us that Jakob-el (and Joseph-el?) was the name of a place in Canaan in the first half of the 15th century (pages 360, 389 f.), and that Israel was a tribe living in Palestine about 1200 B.C.; also that Hebrews (‛Apriw) were a foreign population in Egypt from the time of Ramses II. to that of Ramses IV. (Heyes, Bibel und Ägypten: Abraham und seine Nachkommen in Ägypten 146 ff.; Eerdmans, Alttestamentliche Studien 52 ff.; The Expositor l.c. 197). All this is of the utmost value; and if the patriarchs lived in this age, then this is the background against which we have to set their biographies. But the real question is whether there is such a correspondence between the biographies and their background that the former would be unintelligible if transplanted to other and later surroundings. We should gladly welcome any evidence that this is the case; but it seems to us that the remarkable thing about these narratives is just the absence of background and their general compatibility with the universal conditions of ancient Eastern life.² The case for the historicity of the tradition, based on correspondences with contemporary evidence from the period in question, appears to us to be greatly overstated.