Title: Adrift on the Amazon

Author: Leo E. Miller

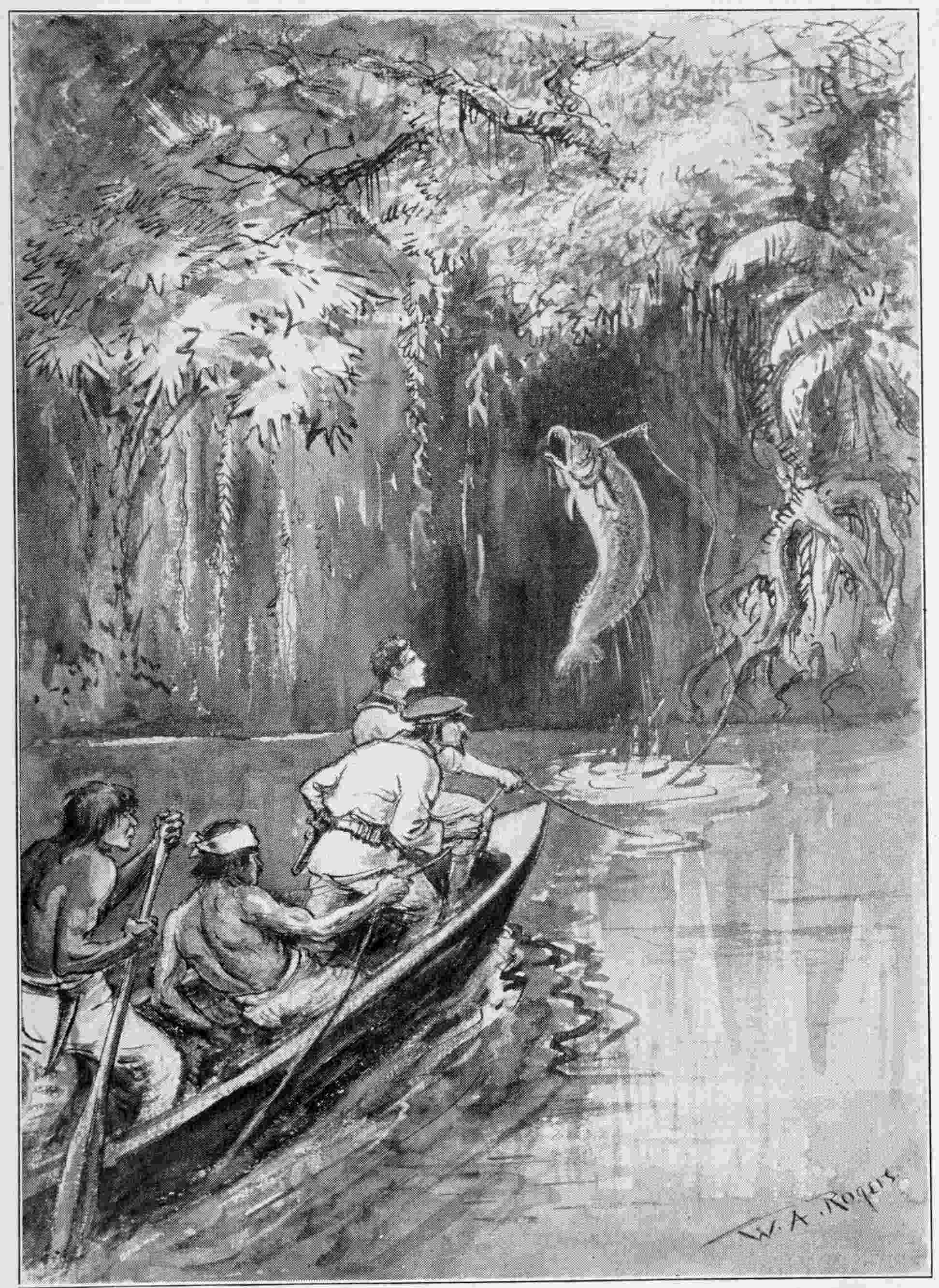

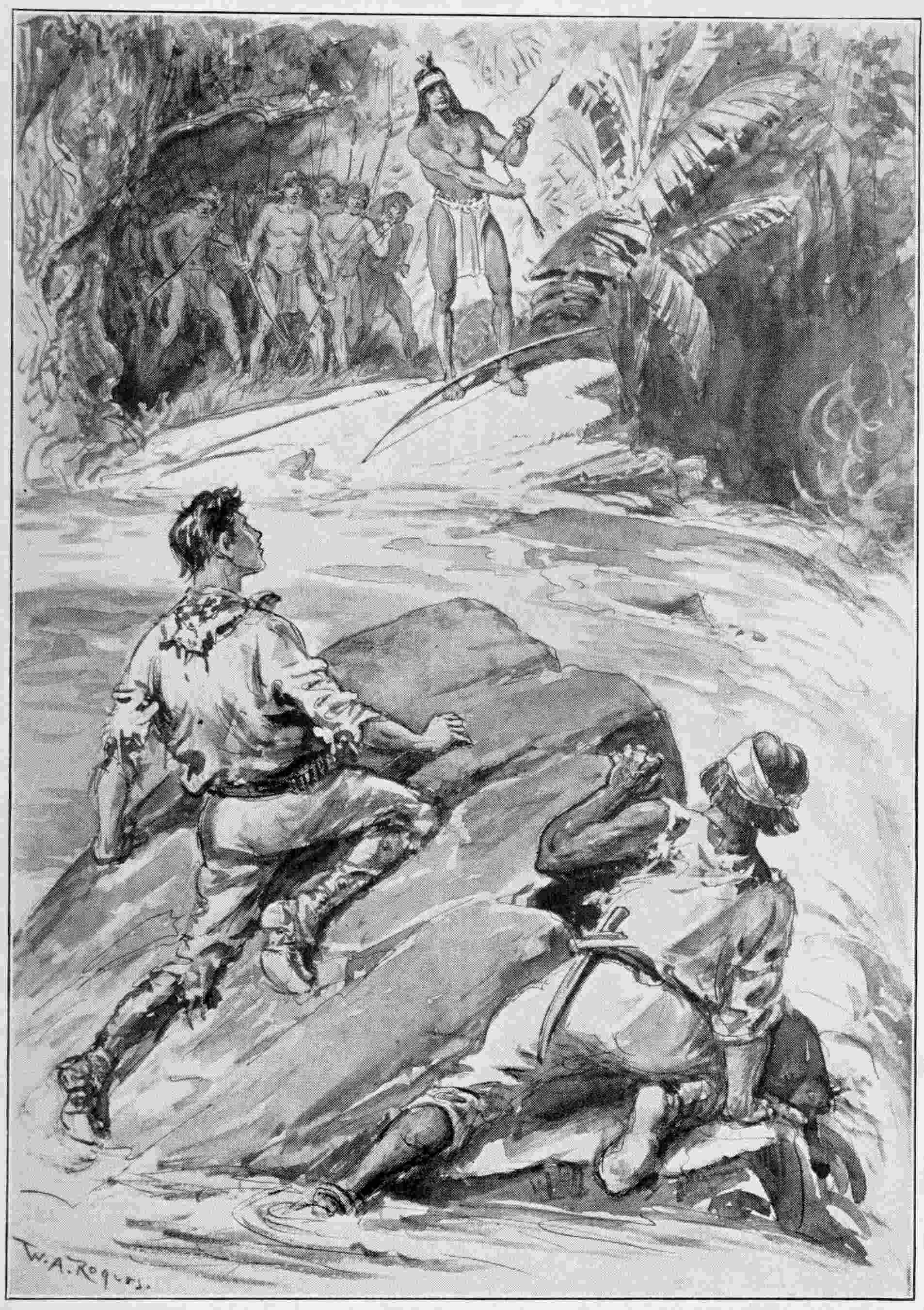

Illustrator: W. A. Rogers

Release date: November 28, 2025 [eBook #77361]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1923

Credits: Chuck Greif & The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

BY LEO E. MILLER

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

ADRIFT

ON THE AMAZON

BY

LEO E. MILLER

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1923

Copyright, 1923, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Printed in the United States of America

TO

ALL READERS

WHO HAVE A WHOLESOME LIKING

FOR STORIES

OF ADVENTURE AND THE GREAT OUTDOORS

The Amazon! Who has not been thrilled at the mere mention of the words? For the name of the world’s mightiest river suggests not only vast expanses of muddy water, but also the jungle-clad shores and wild hinterland where nature seems to have run riot in the development of strange and interesting vegetation and animal life, and of tribes of savages but little known and less understood. There is romance and adventure to be found in each mile of its yellow flood or gloomy thickets. But to only a few is given the privilege of lifting the veil of mystery that hangs over the Amazon country and of exploring its hidden retreats.

“Adrift on the Amazon” is the story of a youth’s struggles against the seemingly insurmountable difficulties that confronted the intrepid wanderer into the Amazon wilderness.

ADRIFT

ON THE AMAZONoi

To David’s friends he was commonly known as “Fighting Jones”; but this name carried nothing of discredit with it; for, though the title had been earned by the not infrequent use of two good fists, the encounters had always been occasioned by a righteous cause—in protection of someone who was unable to defend his or her own interest.

The trouble was that the one higher up, the final authority as it were, had always decided against him. Sometimes words of sympathy, even approbation, had softened the rebuke that invariably followed each altercation; but in the final summing up he had never escaped the penalty.

David was downcast. It seemed as if the bottom had dropped out of everything. And as he mentally reviewed the events of the past ten minutes and speculated upon their consequences he knew that at last he had reached the very end of his tether. He had arrived at the parting of the ways; a break was plainly in sight; and at last he meant to assert himself.

His determined nature began to show itself so long ago as David could

remember and probably before that. But he could recall the first

difficulty in the{pg 1}

{2} kindergarten when one of the older and larger boys

took advantage of his small size to deprive him of some cherished

plaything. He never forgot that fight, nor the punishment he received at

the hand of a stern father.

Later, years later, in high school, there had been the trouble when the principal had rebuked Miss Palmer, the instructor in Latin, before the whole class. The principal was a big, gruff man whose main attributes were to look stern at all times in an effort to instill discipline and to rejoice secretly when others showed signs of fear. He ruled by intimidation. Miss Palmer was meek and frail and when the lordly Mr. Davison assailed her she began to cry. That was too much for David. He calmly arose and informed the surprised Mr. Davison that he would never see any woman mistreated like that and if he did not stop at once and apologize he would knock his block off. Several of his classmates now came to his assistance. That precipitated a row. Result—David as ringleader of the mutiny was dismissed. Discipline had to be maintained.

He worried through school and college somehow or other. Then was forced into business by his father and tried hard to make good and was progressing in a satisfactory, so he thought, if not brilliant manner until——

Wellman, the chief engineer, was passing through the draughting room. David, busy at his board, was not even aware of his presence until he heard a muffled cough in back of him.

“Good morning, Mr. Wellman,” he said pleasantly, turning to greet his chief.

“How are the plans coming along?” the latter said abruptly. “I want to have the blue-prints struck off this afternoon.”

“They will be ready in an hour,” David returned. “I am just finishing the terrace.”

“Let me see!” Wellman adjusted his tortoise shell spectacles. “What scale?”

“Quarter inch.”

“What? Quarter inch?” One would have thought Wellman had been shot, the way he roared. “Didn’t I tell you to make it half inch?”

“I am sorry. I must have misunderstood. I will do them over.”

“Impossible. The superintendent must have the blue-prints tonight.”

“That is impossible too. I cannot do two days’ work in a few hours and do it right.”

“You’ll never know anything.” Wellman bellowed, while all the others in the office turned to see and hear what was going on.

“Now, look here,” David interrupted. “There is no excuse for your acting like that. You passed my table several times both yesterday and the day before and it seems to me as if you should have noticed the mistake then. Besides, I am sure you said quarter inch scale to begin with.”

“That’s right! that’s right! Blame it on me. You think you can do as you please because your father{4} is president of this concern.” The chief was talking louder than ever.

“If it were not for your age I’d thrash you until you took that back.”

“Never mind my gray hair. Never mind my glasses; I’ll take them off. Here I am. Go to it. You are a privileged person around here. Do anything you like.”

Instead of replying, David threw down his drawing instruments and left the room. He headed straight for his father’s office. Arrived there he was told by a secretary to sit down in the ante-room; his father had given orders not to admit him until he should ring for him.

So! He knew about it already! Wellman had forestalled him by using the telephone. It was just as well that he had. His father would have the chief’s version of the affair and be ready to hear the other side of it.

A buzzer sounded and the secretary nodded to him to enter.

For a moment the elder Jones did not notice him. Then he turned abruptly in his chair and faced his son.

“What have you got to say?” he asked, not unkindly and rather sadly.

“Wellman told you what happened, I suppose.”

“Yes. He just called up. I want to hear your side of the matter.”

David gave an accurate account of the occurrence from beginning to end, while his father listened resignedly.

“Wellman is an old and valued employe, but I think{5} this time he went too far. Disregarding the fact that you are my son, I am inclined to believe that you were not at fault—in fact, I am rather proud of the way you handled the situation. Still, that does not settle the issue. That office is too small for you and Wellman; so Wellman will have to go.”

David could not believe his ears and for a moment he was speechless.

“You don’t mean that you are going to fire him?” he asked finally.

“Yes. He went too far. The two of you would always be at odds after this and it would demoralize the whole department. I am sorry, but Wellman will receive his notice today.”

“I don’t want to see him lose his job. He is old and would have a hard time to find another. Why not keep him and let me out?”

“Because I want you to learn this business thoroughly; you may be called upon to take my place some day. You are just starting life. Your welfare is my first consideration.”

David saw his chance at last.

“If that is true,” he quickly interposed, “don’t start me on the wrong track. I do not want to stay in this business. I hate it. I tried to make good only to please you. If you are really thinking of my welfare, let me pick out my own work.”

“What is wrong with this? It offers most unusual opportunities for great and lasting success.”

“I know, but somehow or other I don’t seem to fit in. I dislike the city and all business. I want to go away{6} where there is room to expand and to learn big things of another kind.”

“Remember the possibilities I just mentioned. You might some day erect a building taller than any of today or build a cathedral that would be a monument to your genius.”

“I would rather plow with a tractor and sow wheat; or herd cattle; or raise pigs than build anything no matter how great. I could put my whole heart and soul into that work and enjoy it. I want space to do my thinking and to develop in. I want green grass under my feet and a blue sky overhead. It is too crowded here. There are just as big things to be done in one place as in another.”

“Good gracious! Who put all that into your head? Or did you read it in some book?”

“It has just been growing on me and with me. I must get away from here. Let me work out my own future.”

“Suppose I should refuse to listen any further.”

“Then I am afraid I should go anyway, not right now, perhaps, but at some future time. The thought of all this is bigger than I am, and some day, soon, it would get the better of me and I should be compelled to go.”

“Well, well!” His father was obviously worried. “So you have made up your mind. You refuse to go back to your work here?”

“I should rather not. And, let Wellman stay.”

“I’ll see. Now you go straight home and wait for{7} me there. This thing will have to be settled one way or the other.”

As David left the building his mind was filled with so many things that it was impossible to think clearly on any one of them. Two things kept recurring to him, however, because they had been so unexpected. The first was that his father had taken sides with him in the controversy, had admitted that he was right and that Wellman was in the wrong; he had even gone so far as to volunteer to discharge the old and valued employe. And the second was that for the first time his parent had indicated a willingness to seriously listen to the thing he felt best suited him and for which he was eager to sacrifice his enviable prospects as a man of the business world.

He could hardly wait to tell his mother. She had always been a sympathetic listener and while she had never greatly encouraged him in his ambition she had never discouraged him.

It was, therefore, a source of disappointment to him to find upon reaching home that his mother was not there. She had an appointment for luncheon, the cook informed him, and would go to a club meeting after that. It was impossible to draw any further information from the cook. David suspected that she knew more, but to his casual remark that she must have decided rather suddenly to go, there came no response. Evidently the cook had orders not to talk, so he did not question her further.

The afternoon seemed like a year. He tried to read a magazine; then a book, but after turning a few pages{8} he was forced to admit that he did not know what he was reading about, so he closed it with a bang and calling Spike, his terrier, went for a walk in the garden.

David had just passed his twenty-first year. He was tall, of athletic build, with dark hair and eyes. There was the look of determination in his face that caused others instinctively to respect him. And his regular, pleasant features bespoke intelligence and breeding. If his natural bent could only be diverted into the proper channel, there was no question but that inborn ability and determination would make themselves felt, and in no uncertain manner.

His father and mother returned just in time for dinner. That there was anything unusual about this did not occur to David for, often when his mother chanced to be in the vicinity of the office in the late afternoon she dropped in and the two motored home together.

The conversation during the meal was a conventional one. It was not until later when the three were together in the library that the subject uppermost in David’s mind was broached.

“I have been talking this thing over with your mother,” his father began abruptly. “There is but one thing in our minds. Regardless of how we feel about it personally, we must consent to the course that seems best for your own good.”

David said nothing, but looked expectantly at his mother.

“Are you sure, David?” she asked in a low voice. “Is your mind made up definitely? Is there not the{9} least possibility that you may want to reconsider? Remember you are young. A mistake may mean the loss of years, perhaps, that will never return. Here you have rare opportunities to make both name and fortune. It would be well to think of these things and to try to picture what it will mean to you to give up a certainty for an uncertainty, for you know very little about the course you are favoring.”

“I have thought of all that,” he said uncomfortably, “and I wish I could feel differently, for your sake. But I just can’t help it. I have always wanted to be out in the open where there is room to see and do things.”

For a moment nothing was said.

“Well,” his father finally ventured with a sigh, “then there is nothing for us to do but to give you the chance you think we owe you. Be sure that you are sure. Take a few weeks to think it over in. But you must promise one thing. If we let you go and you don’t make good or find out that you were mistaken after all, you will come back to the office and buckle down to hard work and never mention the subject again.”

“I don’t need the time; my mind is made up now. And, I promise; but I will get along all right and in the end you will be glad you let me try it.”

They insisted on the time for reflection, however, and during the two weeks that followed no mention was made of the matter. David did not go back to the office; he spent the days, and parts of the nights, too, in reading books on agriculture. These consisted mainly of government publications, long possessed and secretly cherished. He had read them so often that{10} he was sure he knew all about farming and ranching; in fact, when he should use all this information together with some ideas of his own that he had worked out, he should greatly improve if not revolutionize the whole farming and ranching business.

When the two weeks had expired there was another council in the library.

“What is the verdict?” his father asked. “Will you go or will you stay?”

“I want to go just as soon as possible.”

“Have you considered the matter fully from all angles?”

“Yes, I have.”

“And you still feel that your calling is out in the country?”

“Be absolutely sure of yourself before you answer,” his mother cautioned.

“I am sure. I feel that when I get away from the noise and hurry and confinement of the city I can accomplish more in a week than I could here in a year.”

“And, if after trying it you find that you have been mistaken?”

“I shall come back at once and do exactly as I promised.”

“That settles it. You shall have your chance and it will be a rare one even though you cannot realize at what cost to us.” He shot a quick glance at his wife; her eyes were glistening.

“The fact that we have known of your ambition for a long time does not make it easier for us, for you will{11} be far, far away. That alone will give you the opportunity to show your mettle. I think it best that it should be so, for you will be thrown entirely upon your own resources. Either you will become discouraged quickly and come back ready to take our advice, or you will do big things.”

“Where?” David asked in an awed voice. “Where am I going?”

“To South America, because there real opportunities exist for the right man.”

“South America?”

“Yes. Dan Rice, a former client of mine, has a ranch in the Argentine. He went down fifteen years ago. He was a born stock man and made a huge success of the venture. I enquired about him and learned that he is opening a new place in Brazil, somewhere in the Upper Amazon country, above the city called Manaos. I shall send you to him. If ever there was a person who could judge men and get the best out of them, Rice is the one. What do you say?”

“I don’t know what to say except to thank both of you for letting me go. It is better than I even dreamed of. It will be wonderful!”

“Good! I only hope you will not be too greatly disappointed when you get there.”

They continued the discussion far into the night; but the thing the elder Jones did not tell his son was that he had already sent cablegrams to Rice in Manaos in an attempt to make arrangements for his coming. A very short time in the steaming and insect-infested tropics would be sufficient to cause a change of heart,{12} he felt sure. The fact that he was in a wild country thousands of miles away from home and among strangers would hasten it and make it more emphatic. And, once his illusions were dispelled, David would be ready to settle down and do as he was told.

As for David, he was too elated for words. “I am going at last,” he kept repeating to himself. “My luck has changed! My luck has changed!”

But David was quite forgetful of the fact that there are two kinds of luck, good and bad; and that the former seldom lasts long, while the latter is inclined to linger with a most disheartening persistency, and then grow worse.

David was so excited over his proposed trip to a real ranch in South America that he found sleep impossible on the night following the momentous decision.

His head felt like a whirling mass that refused to come to a standstill. He thought of a hundred things that he wanted to do all at once, but the thoughts rushed back and forth and around in circles so that he could not disentangle a single one to start with.

He was going to have his wish at last; that much he realized. And South America at that! The very words were awe-inspiring. They suggested mighty rivers, vast jungles where monkeys formed living chains or bridges to span the streams, by clutching one another’s tails; and where giant snakes drooped like garlands from the branches of great trees while myriads of gorgeous birds and shimmering butterflies fluttered among the bright-colored flowers. These sights must be common ones, for had not the geographies pictured them as typical of the Southern Continent?

David did not care, particularly, for some of the things he was sure he should encounter—especially the snakes and the crocodiles. But, of course, a ranch would not be situated out in the jungle; it would have{14} to be in the open where there was grass for the cattle. He tried to picture such a place. A long, rambling building painted white, with a few palm trees in front under which saddled horses were waiting patiently for their riders; more trees, of some kind or other, nearby, in the shade of which men dressed in buckskins, with fringes on their breeches and great, leather gauntlets on their arms, were sprawled on the grass, their wide-brimmed hats lying on the ground where they had been carelessly tossed by their owners.

All about stretched the rolling meadows, miles and miles, dotted with herds of cattle peacefully grazing on the long, green grass.

That was the picture that formed itself in his mind. But the things that did not occur to him, the things the geographies did not mention and that no one had told him about, so far, were the blistering heat of the tropics that could scorch and burn as mercilessly as the blast from a furnace; the insect pests that rendered life all but unendurable; the fevers that sapped one’s vitality; and the monotony of existence in far-away, lonely places with only the treacherous half-breeds and stolid Indians for companions. It was just as well that these unpleasant details and many others of similar nature remained in the obscure background; he would make their acquaintance soon enough.

“Better decide on what you want to take with you,” his father advised the next day. “You will not need anything fancy, and keep the amount down as much as possible. Talk it over with your mother.”

That was good advice and David followed it. But{15} it required nearly one full day to make out the list, go over it carefully, strike out some items, add others, and then start over again with the ever-present suspicion that something of importance had been forgotten.

“I’ll tell you what,” he said finally, “I am not going to take anything except a few clothes to wear on the trip, one khaki outfit and a gun. How do I know what is proper down there? I might take down a lot of things only to find that they are not suitable in that climate. And the other fellows working on the ranch must get their clothes somewhere in the neighborhood, so I can, too, after I find out exactly what I need.”

His mother promptly agreed that that was the sensible thing to do. Only, she added, a few good books might prove not unwelcome companions on such a trip, so David promptly packed his volumes on cattle and agriculture as well as a few favorite others.

The news of his intended journey spread rapidly among his friends and acquaintances. They immediately divided into two factions; one considered him the luckiest mortal in the world while the other thought he was the most foolish person imaginable.

David pitied them all, impartially. No matter how they felt, they were all doomed to remain behind, chained to the treadmill of city existence, while he was the one to go forth into God’s great world with only the horizon to mark the boundary of his vision and activity.

“I cannot understand it,” Mr. Jones announced one evening soon after. “Rice has not answered my cable. Perhaps he has given up the ranch and gone{16} to other parts. I am sorry, but you may not go after all. Too bad, after all the anticipation.”

David’s heart sank.

“Rice or no Rice, I am going just the same,” he announced.

“But where to? If he has gone away there will be no place to which you can go.”

“He couldn’t take the ranch with him, could he? If he has gone someone else must have it. And even if that outfit is out of existence there must be plenty of others. I am not fussy over where I make my start.”

“Very well. So far as this proposition is concerned you shall have your own way. But you cannot blame me for being concerned about your welfare.”

“Of course not. But at the same time, please don’t forget that I am not a baby. I can take care of myself.”

His father bit his lip. His eyes narrowed as he regarded his son. And in that instant an idea came to him.

“Just as you say,” he said quietly. “It will be your chance to show me just what you can do. The Morales sails a week from today and I shall make a reservation for you. In the meantime, I shall send other cables; you may go regardless of whether there are answers or not. Is that satisfactory?”

“It’s splendid. I won’t sleep a wink until then.”

On the eve of the great day the little group around the dinner table was very silent.

“Rice has answered at last,” Mr. Jones said suddenly.

“What did he say?” asked David, eagerly.

“Never mind what he said. You are determined to go, anyway, so it makes no difference.”

“But does he want me to come?” David persisted.

“Suppose he does?”

“I should go, of course.”

“And if he does not?”

“I should go anyway. I am all ready, my ticket is bought and I couldn’t think of backing out. I should never hear the last of it.”

“You are quite right. Everything is arranged, however, and I want you to go. You will do just as you planned.”

David thought he noticed an amused expression on his father’s face, but he was not quite sure. It did seem, though, that his manner had changed remarkably in the last few days. His former reluctance had given way to seeming eagerness. But in the feverishness of his excitement David did not appraise these observations at their proper value and soon forgot them entirely.

At last the memorable day actually arrived. The weeks of waiting had seemed an eternity. But here he was, aboard the great boat; some of the people about him were crying and for a moment he felt a strange feeling coming upon him. Going was not so easy as he had thought. Just then the bell warned all visitors to go ashore and amid the last farewells he was reminded of one thing.

“Do not forget,” his father said, “you may return at any time you like and you will be welcome at home.{18} Even if you stay only a few days, the experience of the voyage will be of value and you will be more content to settle down. Perhaps you will be back soon.”

They went ashore. The gangway was raised and the engines began to throb ever so slowly as the ship backed out of her berth. Not long after that the boat was well out in the bay and the crowd that lined the dock merged into a waving mass in which it was impossible to distinguish anyone.

Those last words filled David with something like resentment.

“Perhaps you will be back soon!” Indeed! What did his father mean by that? Well, they would have to wait a long time before seeing him again. Upon that point he was determined. No matter what happened, he would not return home very soon. He would stick it out in the face of every obstacle and difficulty that might block his path. He would show them that he could make good if he but had the opportunity and the opportunity had come at last.

By that time the ship was well down the harbor, so he sought his cabin to unpack his baggage. Upon entering he found a man several years his senior busily engaged straightening out his own effects.

“My name is Rogers,” said the stranger, extending his hand. “I guess we share this place.”

“Glad to know you. My name is Jones.”

“Well, as we are going to bunk together for a while I suppose we might as well toss a coin for the berths.”

So saying, Rogers fished a dime out of his pocket.

“What will it be?” he asked.

“I’ll take heads,” David replied.

Rogers tossed the coin into the air.

“Tails, you lose, Jones,” he said. “So I will take the lower. Anyway, you are younger and more spry than I am, so you will not mind climbing into the upper.”

The conversation continued while they unpacked their luggage and the older man gave David a good deal of information, having noticed that he had not been to sea before. David rather liked Rogers and felt that this was the beginning of a pleasant friendship.

* * * * *

Dinner in the Jones household was a quiet, solemn affair that night.

“Wellman played his part to perfection,” the father said finally. “Too well, in fact. For a while I was afraid David would agree with me that he should be discharged. But I am proud of the stand he took. He acted just as I would have had him do.”

“Are you sure he does not suspect the plan was pre-arranged?”

“Yes, he thought Wellman was serious in calling him down. He was going from bad to worse—through no fault of his own, I will admit. He tried hard to make good but could not; and he never will until he forgets those ideas with which his head is crammed. Only then will he come back to earth and buckle down to his job.”

“Do you think he will be back soon?”

“Yes, I think so. When he sees what he is compelled to endure in Brazil he will become disillusioned in short order. I know what I am talking about and so I think a short time of it will be all he wants. Three months, at most.”

Mr. Jones spoke with an air of finality. The ability to look ahead and forecast the outcome of things had in a large measure placed him on the pinnacle of success he occupied. But for once, and in spite of carefully arranged plans, he was doomed to disappointment. For the son possessed all the advantage; he was entering with unbounded enthusiasm a field for which he had prepared himself, however slightly, and of which he therefore had some knowledge, while the father was making predictions as to the outcome of affairs of which he knew nothing.

Early the next morning David became aware of the fact that he had embarked on a stormy voyage. The ship rolled and pitched in an alarming manner. He could hear the shrieking and moaning of the wind and feel the vessel tremble as the waves struck the steel sides with a muffled roar.

At first he did not know just what to make of it, so he groped for the switch and turned on the light. Rogers was sleeping soundly in the berth below. There was no one stirring on deck or in the passageway, so he came to the conclusion that a storm was not an unusual occurrence and that everyone took it as a matter of fact, so he snapped off the light.

But it was far from comfortable, this rolling and tossing, and sleep was impossible. Daylight soon came, however, and with it the bustle and sound of voices on deck incident to life aboard ship.

“Going down to breakfast?” Rogers enquired, holding to a hand-rail with one hand while he calmly shaved with the other. He seemed to mind not at all the lurching of the boat.

“I guess not; I don’t feel hungry,” David replied in a weak voice.

“Sick?”

“A little. It’s not so bad while I lie still; but when I try to get up my head spins.”

“Never mind. It will soon pass. Better have a cup of coffee; then you will feel better. I’ll ring for the steward.”

“No, don’t. Please, let’s talk about something else; anything but food. Will the storm last long?”

“It may clear up later. If it gets calmer come out for a walk on deck. The fresh air is a good tonic,” and he strode out of the room.

But the storm did not subside. It lasted two whole days and three nights. By that time David was so ill he was compelled to remain in his berth another full day to recuperate sufficiently to venture out.

The fresh air and the bright sunshine on the upper deck worked wonders. Added to these, long walks back and forth, a few games of shuffleboard and an occasional dip in the ship’s swimming tank soon restored his good health and usual cheerful manner.

“You expect to work on a ranch in Brazil, eh?” Rogers commented one morning as they leaned over the rail to watch the flyingfish startled by the prow of the boat as she cut her way through the glassy water.

“I not only expect to but I am going to,” David returned promptly.

“How long are you going to stay?”

“A long, long time. In fact, I haven’t thought of going back. I had better get there first.”

“Know anything about ranching?”

“Not much; but I can learn.”

“Know anything about Brazil or what you are going to be up against?” Rogers persisted.

“Not a thing.”

“Do you know what I think?”

“I’m not a mind-reader.”

“Well, I think you are foolish to try it.”

“Thank you,” David replied promptly.

“I mean it.”

“I can’t help what you think,” pleasantly. “My head is working overtime figuring out my own things.”

“I would not go where you are going for a thousand dollars a month.”

“Neither would I. I am doing this because I am interested in it and want to learn. Office work, no matter how easy, is unbearable to me because I don’t like it. Outdoor work, no matter how hard, will be fun because I do like it.”

“I went to Manaos once, and that was far enough,” Rogers proceeded. “The heat, the rains, the mosquitoes, in fact everything that makes life miserable was there in too great abundance to suit me. If I were in your place I should go up the river for the sake of the trip. The Amazon country is great—to see from the deck of the steamer. Look at it until you have your fill and then go back to the good position you left. I am telling you right now that you are making a big mistake, and you will regret it.”

“It’s very kind of you to take such an interest in me, but you must think I am a jellyfish. There is no use saying anything more. My mind is made up. I{24} wouldn’t even think of backing out—not for the world,” Jones asserted in no uncertain accents.

“All right. Think it over.” Rogers yawned and went to his deck chair, while David took a small, red volume from his pocket and devoted his time to the study of Portuguese.

The days slipped by pleasantly and quickly. The water assumed a deeper blue color and great rafts of seaweed dotted the surface. The air was balmy and delightful.

There was always something new and interesting to see. The birds in particular attracted David’s attention, especially the man-o’-war birds that soared on motionless, narrow wings hour after hour and, it was said, day after day, in the cloudless sky. They rarely slept or rested but sailed on tireless pinions as if they enjoyed it, bent on some mission none could fathom. Then there were the little petrels or Mother Carey’s chickens, as the sailors called them, fluttering and skipping over the water like huge, black grasshoppers; they appeared in greatest numbers on those rare occasions when the ship passed through a choppy stretch of water.

Some of the barren, rocky islands were fairly teeming with boobies, jaegers, gannets and other feathered lovers of the briny deep. They sat on the shelflike ledges running along the faces of the cliffs like the tiers of beads on an abacus. Other swarms filled the air, fluttering, soaring, circling and wheeling amidst squawks and screams while still other hordes sat motionless on the water.

The jaegers were the pirates of the deep. They waited until the smaller birds returned from their successful fishing excursion, then attacked them until they disgorged their catches which they greedily appropriated to their own use.

These sights fascinated David. How different from the imprisonment of the city! And this was but a taste of what he was to see, a sample of the free life in the open for which he longed.

After nearly two weeks sailing he came on deck one morning to find that the color of the water had changed overnight. Instead of the clear, crisp blue the ship was ploughing her way through a sea of yellow that extended to the horizon on every side. He called the matter to the attention of Rogers.

“That muddy water is discharged by the Amazon,” the latter said.

“But we are not near the river yet,” David remarked incredulously. “There is no land in sight.”

“No, we are not near the river and will not be until some time tomorrow. Even if we were in the very center of the Amazon you could not see the banks, for the river is about one hundred and fifty miles wide at its mouth. The quantity of water it carries into the ocean is so enormous that it keeps its yellow color several hundred miles out at sea before the mud settles and the fresh water is thoroughly mixed with and absorbed by the brine of the ocean.”

The next evening they saw the first indication of land. At first there were only long lines of white far in the distance where breakers were dashing over the{26} low sandbars that checked their onward sweep. Later, they distinguished small, dark tufts, like feather dusters, outlined against the clear sky; these were coconut palms growing on the outlying islands. And before long the first land—dim strips of dark color seemingly suspended between the water and the sky, met their gaze.

At night they entered the river proper. It was too dark to see anything, but David was so excited he could hardly sleep. Here he was, on the mighty Amazon, and it was not a dream either. What tales the silent water could tell could it but talk! What had the stream witnessed, on its journey through many thousands of miles of wilderness and jungle inhabited by savage beasts and equally savage peoples! And what secrets were locked up in that outwardly calm, yellow flood! The very air seemed saturated with mystery, romance and adventure. And here he was, alone and foot-free and eager to absorb his full share of everything this wonderful country offered.

With daylight came disappointment. Instead of the wide expanse of water David had expected to see there was only a narrow channel through which the ship proceeded with caution. Both banks were covered with heavy, deep green vegetation, extending to the edge of the river. Creepers and ropelike lianas dangled from the branches and trailed in the water; climbing ferns and palms and a host of other plants clinging to the boughs and trunks united them into a solid wall of living green.

Here and there a bright-colored flower glowed bril{27}liantly against the darker background and from the interior of the tangled, matted screen came subdued cries and screams. A flock of green parrots, flying low, passed overhead and then dived into the jungle on the other side and disappeared. There were fully a hundred birds in the party, but they flew two by two, with a peculiar fanning motion of the wings, like a duck’s.

One of the branches on the side nearest the steamer stirred and someone shouted “monkeys.” David looked but saw only the swaying vegetation which moved as if agitated by a gust of wind.

“I am sorry I missed them. I have never seen a wild monkey,” he said.

“You will see plenty of them before long; and not only see but get real well acquainted with them,” Rogers volunteered.

“You mean they are tame and come to the camps in the forests?”

“Not exactly. You will have to live on them.”

“What? Eat monkeys?” David asked in dismay.

“Certainly. Everyone does in the bush. The Indians eat everything—monkeys, crocodiles, snakes and lizards. And if you want to live out in the wilderness you shall have to do as they do because there is no other way out of it. You will be thankful for whatever you find whether you like it or not.”

“But the rivers must be full of fish,” David reminded him.

“They are. Catching them is another proposition though. Besides, there is nothing in the world a white{28} man becomes so tired of as fish if he eats it day after day.”

“Why worry?” David said it bravely, but a sigh escaped him. “If that is the custom here I guess I can get used to it.”

The prospect of having to eat monkeys, as he knew them in the zoo at home, was not a pleasant one and the thoughts that were in his mind were reflected in the expression on his face. Rogers gave him a sharp glance, then walked away; he was finding his task a difficult one.

The first stop was at Pará, and as the steamer carried a quantity of freight for that port and was to remain two days there was ample time for sightseeing ashore.

The feel of solid ground under his feet was very welcome to David; and to enter the low-lying city beside the river was like stepping into fairyland.

How different everything was from the life and living conditions of a temperate clime. Instead of the tall buildings and wide streets bustling with humanity there were blocks of low, white structures, narrow, crooked streets lined with drooping, swaying palms; and the people, of every shade from white to black, seemed to take things in a leisurely manner.

It was warm—disagreeably warm at midday and during the early afternoon hours—but David was too interested in his surroundings to take much note of the heat. He tramped the streets and tried to see everything that unfolded itself before his eyes.

The flaming Jacaranda trees that thrust themselves{29} upon one’s notice through the sheer boldness of their beauty fascinated him. Not extremely tall but with wide-spreading branches they looked like enormous bouquets so thickly were they covered with purplish flowers with only an occasional tuft of fern-like leaves to enhance their beauty.

There were palms without number. Some grew tall and stately with crowns of gracefully drooping leaves; others had bent, spiny stems; and still others had shocks of ragged, split leaves perched on the top of thick, ringed trunks.

A curio store just off the main thoroughfare attracted David’s attention and after gazing at the display in the windows for some time he decided to investigate the mysteries inside so forcefully suggested by the objects in front. He had always intended to make a collection of butterflies and other things and here was the opportunity to start it. But the door was locked. He tried the door of the next shop; it, too, was bolted. A passing policeman, observing his actions, volunteered the information that everything would be closed until later in the afternoon because the people were taking a nap during the hottest part of the day. And as David strolled down the street he rejoiced that the curio store had been closed, for what could he have done with the butterflies if he had purchased them? They were too fragile to carry around for months in the wilderness; and he would no doubt have the opportunity personally to collect all he wanted at the ranch.

The afternoon being spent, the wanderer went back to the waterfront and boarded the steamer, and re{30}mained aboard for the night. There followed another day of sight-seeing, confined principally to the numerous little parks, and then the voyage was resumed up the river.

David remained on deck as the steamer headed up the sluggish, muddy stream and enjoyed the changing vistas of broad expanses of water and the dark green of the vegetation that contrasted sharply with it. Then he went to his cabin to wash up for dinner. And there was Rogers examining a number of souvenirs he had purchased in Pará; a medly array of feather flowers, Indian head-dresses and the skins of birds and snakes was spread on the floor and chairs.

“You still here?” David asked in surprise. He had not seen him since saying good-bye the morning they reached the port, as Rogers had stated that he was going no further than Pará.

“Yes, I am going to stick around a while longer—until we get to Manaos, to be exact,” Rogers replied in a matter-of-fact voice.

“Great! But you changed your mind rather suddenly, didn’t you? I hardly expected to see you again.”

“I did intend to go only to Pará, but I found that my affairs had not been settled. So I have to keep on going. But I do not mind. The trip up the river is interesting.”

“Say, Rogers,” David asked suddenly. “What is your business anyway? I don’t like to be inquisitive; that is why I didn’t ask before now. But I am filled with curiosity.”

“It is of a personal nature; sorry I cannot go into greater detail but that would be violating a confidence,” and Rogers looked embarrassed.

“I see,” David said simply, but he could not get the matter off his mind, try as he would. And to make things worse he could see no reason why Rogers’ affairs should cause him any concern.

To spend six days on the mighty Amazon is an event in any man’s life; to David it was the greatest he had experienced. Each morning when the noise of the deck scrubbers awakened him he jumped from his berth and after dressing hastily went on deck to see the sun rise. On no two mornings was the awe-inspiring spectacle that unfolded itself before his eyes the same in all respects. Sometimes the flaming, angry ball of fire shot up as if from some place of concealment beyond the black wall of forest; once it rose out of the yellow flood, at the foot of a wide path of gold and pink light that danced and sparkled on the wave-crests; and again, there were but fleeting glimpses of shafts of bright light that darted through rifts in the cloud-banks whose edges were aglow with burnished silver.

When the forested banks were visible they always loomed up like dark, impenetrable barriers; but as the light grew stronger the blurred outlines of trees, palms and a thousand points of vegetation gradually became clearer and finally revealed their identity.

The forest enchanted the beholder. It exhaled an air of mystery, the promise of adventure; and at the same time it hurled a bold defiance. “Come, ferret{32} out my secrets, search for my treasures,” it seemed to say, “and I will overwhelm you, engulf you and you will be no more. But come, come, if you dare.”

David read both the invitation and the challenge; and with more determination than ever, he accepted them.

Nothing was seen of the wild life with which the jungle must have been teeming. Perhaps it was because the walls of vegetation were so dense they hid the creatures that lurked within their green depths. Then, too, the river was frequently so wide that the banks could scarcely be distinguished, showing only as low, dark lines in the hazy distance.

Occasionally a flock of ducks passed overhead. There were gulls also, and other waterfowls. But far more numerous were the parrots and great macaws, in large, boisterous companies that winged their way heavily across the wide expanse of water. From a distance the parrots resembled the ducks but there was always the easily noticeable difference, that no matter how large their number, they always flew two by two.

“Where are all the crocodiles?” David asked the captain of the ship one day as the latter stopped beside him at the railing. “And the big water snakes and other things you hear about the Amazon?”

The captain looked at him in an amused manner.

“They are here, that is the crocodiles are, but the water is too high to see them,” he said. “During the dry season the sand bars and islands are covered with them. There are plenty of anacondas, too, but they{33} stay around the banks. So you are going into the interior, I hear!”

“Yes, to a ranch that’s just starting up,” David replied.

“Well, you’ll see all the snakes and other vermin you want, and more too.”

“Fine! I have never been here before and I want to see everything there is to be seen.”

“You had better look fast then, because you won’t stay long. They all go back pretty quick.”

“Not I. I am going into the business for good.”

“That’s what they all say. And I carry them back home on the next boat.”

“You will not carry me back on the next boat, nor on the trip after that either.” David was losing patience.

“If you knew what’s in store for you you wouldn’t even go ashore when we get to Manaos; you would come right back home with me on this trip. And that is what I would advise you to do.”

“Thank you,” and David walked away.

They made short stops at the more important towns along the river, to deliver mail and unload freight.

The waterfront in these places always teemed with dark-skinned natives. Long lines of men, stripped to the waist, were carrying bags of produce to barges moored to the banks, waiting for steamers going downstream. Groups of other men lounged on the docks or came to the ship in row-boats, offering fruit for sale.

David was greatly surprised to see the barges of Brazil nuts that were being transferred to a steamer{34} outward bound. The nuts—he had no idea there were so many in the world, were handled just like coal. They were scooped out of the barges in steam shovels and dumped into the hold of the boat, where they disappeared in the seemingly insatiable, black void. Many were spilled overboard and others rained on the deck, but no one cared.

There were cargoes of rubber, too, large, oblong balls, or thick bricks that must have weighed several hundreds of pounds. But David was to see enough of them later and under less attractive circumstances.

On the sixth day they reached the junction of the Rivers Negro and Solimoes.

“This is the end of the Amazon,” Rogers explained as they gazed at the sweep of the mighty streams.

“The end?” David asked in surprise. “I always thought of the Amazon as a river three or four thousand miles long.”

“The Amazon proper is only about one thousand miles long. But the Solimoes continues on a few thousand more and is in reality the Upper Amazon. Here is a map that shows it.”

He drew a folder out of his pocket and they spread it on the foot of a deck chair.

“See?” Rogers said, “Manaos is ten miles up the Rio Negro which comes from the north-west. The Solimoes comes from the west and has its source near Quito, Peru. It is navigable, too, almost the whole of its length in boats of some kind. As I said, though, you have seen all of the real Amazon. Now, are you satisfied?”

“What do you mean?”

“Have you seen enough?”

“Of the river and country? I should say not. I haven’t even started. What I have seen has only aroused my curiosity and a stronger desire for more. I can hardly wait to get into the interior. Think of what is behind those walls of forest!”

“Mosquitoes, snakes and cannibals.”

“Good! They are just what I want to see.”

Rogers sighed but David did not notice it. He folded the map and put it back into his pocket.

In another hour they had reached Manaos.

Manaos is a surprisingly large city for one that is situated in such an out of the way place, but there is nothing bewildering or startling about it. In some respects it is very much like the larger but more backward towns of our own country but in most it is very different.

The first thing to thrust itself upon the visitor’s notice is the intense heat; all the sun’s rays seem to converge in the depression in which Manaos nestles. An inspection of the place, however, reveals compensating virtues in the form of green, shady parks, cooling fountains, and comfortable hotels for the traveller.

David was not particularly interested in the city although he took note of some of the more unusual features; he had seen Pará which had impressed him as being more attractive. He felt that enough time had been spent already in travel and in sight-seeing and he was eager to start work. So he lost no time in going to the hotel where someone from the ranch was to meet him, in accordance with the arrangements that he supposed had been made by cable before he left home.

No doubt Mr. Rice had come to welcome him{37} personally, he thought; and he was more than disappointed to learn that such was not the case.

“Senhor Rice has not been here in weeks,” the proprietor of the hotel told him in answer to his questioning.

“But he was either to be here or to send someone,” David protested. “I am going to his ranch and they were to come for me.”

“Here is the list of patrons. You may read it. Do you recognize any of the names?”

David scanned the page of the register and admitted that the names were all unfamiliar to him.

“I would recognize only Mr. Rice’s name,” he added, “and that is not there.”

“No, the Senhor is not here.”

“Didn’t someone else say he expected me? There must be somebody here who is hunting for me right this minute.”

The Brazilian shrugged his shoulders.

“Oh, I understand now,” David explained, with a smile. “Whoever is coming hasn’t arrived. He might have been delayed accidentally or perhaps he thought the steamer was not due today. I’ll wait and everything will be all right. When I am asked for, remember that I am here. And, if a message or letter comes, give it to me without delay.”

The whole explanation seemed so simple to David. It must be exactly as he had said. It was not in the least remarkable that one should miss connections in a land lacking the elaborate facilities for travel his own country boasted. He wondered how the matter could{38} have caused him concern and why he had not thought of the solution before.

Half an hour later he left his room and in passing through the corridor could not resist the impulse to step into the office to make another inquiry. But the answer was the same. There was nothing new, no message; nor had anyone arrived from the ranch.

“Tomorrow, probably,” he thought, “and if not then, the day after that without fail. I must learn to be patient although they should apologize for keeping me waiting.”

In the meantime, he would see what there was of interest in the city, and by asking questions learn as much as possible about the country of the hinterland.

He had not gone two blocks before he met Rogers. The latter was stopping aboard the ship; he felt sure that he could wind up his affairs during the week the vessel lay in port and had engaged passage for the return journey.

“Hello!” he greeted David cheerfully. “You still here? I thought you might be on your way to the ranch by this time.”

“No, we missed connections some way. I can’t understand why, but they have not come for me yet. But I expect them any minute.”

“Still got the fever, eh? Still want to go as badly as ever?”

“I certainly have got the fever, and the temperature is going up.”

“Say, you know what I said to you before—I think you are one foolish person.”

“Look here, Rogers,” David retorted hotly. “Why are you so concerned over my affairs? I didn’t insist on knowing what brought you here but you keep harping about my business all of the time. Now forget it.”

“If that is the way you feel, I shall not mention it again,” Rogers stammered, looking offended. “But—but just because I do not mention it will not make me feel differently about it. I am sorry you are so set on doing something you will surely regret.”

“Good-bye.” David wanted to fight but he dared not, remembering past experiences and their consequences, so he quickly continued on his way.

Three days passed and still David remained unsought by anyone from the ranch. The fact began to worry him.

He had spent the time alternately waiting in the hotel and tramping the streets. The very sight of the Teatro Nacional, at first so imposing on its built-up pedestal that covers an entire city block; the plazas with their tropical trees, shrubs and dazzling flowers; the hot, winding streets; and the parrots shrieking and squawking from their perches in the doorways of the squat, thick-walled buildings; all began to pall on him. He had not come all that distance to see cities; if that had been his desire he might have remained at home. What he longed for was the great outdoors and the myriad, varied possibilities it brought with it.

Why did not they come or at least communicate with him? he asked himself again and again. He could bear the suspense no longer. He would communicate with them.

The telephone occurred to him first of all as the most rapid means but, of course, there was no service to Las Palmas. Nor was it possible to send a telegram. A letter was the only thing he could think of; but when they called for the letter they would also come for him. So there was in reality no way of communicating with them after all.

In desperation, he went to the owner of the hotel and told him what was on his mind.

“If they knew you were coming and wanted you at Las Palmas, they would have been here,” the latter said. “What do you expect to do there, anyway? My advice would be to go back home, if you asked me. You will be better off there.”

“Good Heavens! This is beginning to look like a conspiracy of some kind,” David started, but checked himself. Again the visions of past experiences loomed up before him. He would endure almost anything rather than take a single chance of spoiling this new and greatest of all ventures. So he turned and walked away.

“I know what I’ll do,” he decided. “I’ll see the American Consul. He will fix me up.”

Just as he turned to enter the doorway beneath the shield that served as the guiding sign to the consul’s office he almost collided with Rogers coming out.

They exchanged greetings and each went his way.

After waiting a few minutes in the anteroom he was admitted to the official’s presence and briefly explained his mission. The consul listened impatiently for a minute and then interrupted the recital.

“You will never get on there,” he said. “It is no place for an American without practical experience. Las Palmas is a particularly bad place and Rice is a terrible person—they call him the viper.”

David was boiling within, but said nothing, so the official continued:

“The ranch is a new one, just being opened up. No one but the natives and Indians can do the clean-up work that is in progress now. You would die in a little while if you tried it. I will fix up your passport and you start back on the next boat.”

“I see,” said David simply, without betraying his feeling. “Thank you for your offer but I cannot accept it just now for I am certainly not going back home. I came to stay.”

“Stay and you will be sorry.”

“That’s up to me. And if Mr. Rogers comes to see you again, give him a passport. I intend to see to it that he leaves the country on the next boat.”

The air in the street lacked the cooling quality necessary to restore David’s ruffled temper. Heat-waves rose from the flag-stones and smote him in the face and the slight eddies that whirled around the corners could have come out of the mouth of a furnace—they were so stifling.

The truth of the whole matter dawned upon David at last. Rogers was the cause of all the discouragements he had met. The business upon which he had come was to try to persuade him to return home. He had been sent for that purpose. He chuckled grimly as he thought how Rogers would have to report failure{42} of his mission. They would see that he was not a quitter. He did not blame his father for guarding his welfare but he would prove to the world that he could look after his own interest in any place and under any circumstances. The newly acquired knowledge made him more determined than ever. So, as he returned to his lodgings a plan formed itself in his mind; he would put it into effect without delay. There was but one other matter that had to be attended to first. He must see that Rogers actually sailed on the departing steamer; with him out of the way, the rest would be easy.

A full hour before the ship was due to leave, David went aboard. And about the first person he met on deck was Rogers.

“I came to see you off,” he said in a friendly manner.

Rogers looked at him with a puzzled expression on his face.

“You are going, aren’t you?”

“Why, yes, I guess so.”

“Seems to me you ought to know for sure. If you don’t, I will tell you. You are. I am on to your game. The best thing for you to do is not to waste any more time. Tell them back home I am all right; and that you did your best to discourage me but—you know the result. I am sending letters on this same boat. Now, good-bye, and have a nice trip. I am going to wait at the dock until you are out of sight.”

For a moment Rogers did not know what to say. Then he extended his hand.

“Good-bye,” he said simply.

“No hard feelings so far as I am concerned. You went to a lot of trouble for nothing.”

“I am sorry, that is all.” Rogers appeared dejected. “And I can only hope that you will reconsider the matter before it is too late. Remember how they feel about it back home.”

David went ashore and waited. It was with a feeling of relief that he saw the ship move out into the river at last, with Rogers at the rail waving a last farewell. When the vessel finally disappeared from view he turned his steps toward that section of the riverbank where a number of launches were tied up, with their crews either aboard or on the bank.

“Where can I hire a boat?” he asked one of the men. “I want to go a short distance up the river.”

“There is the capitain,” the sailor replied, pointing to a man dressed exactly like the others but wearing an officer’s cap on his head.

David repeated the question to the person indicated.

“Where to?” he asked.

“The ranch Las Palmas.”

“Why don’t you go on one of the Las Palmas launches?” the captain asked abruptly.

“I would if I knew where to find one. But I have been waiting a number of days and none of their boats has put in here,” David explained.

“I will show you one. See that gray launch right over there, the Aguila? That belongs to the ranch.”

David could have shouted for joy. They had come for him at last. He hurried to the Aguila. Perhaps Mr. Rice had come in person to greet him. This was{44} luck indeed! Probably he had hurried to the hotel with apologies for the delay; but no need for that inasmuch as he had finally come and the long wait was over. There was the possibility, however, that he was still aboard the launch.

By the time David reached the boat it was almost impossible to suppress his eagerness and excitement.

“The Aguila comes from Las Palmas,” he began, “so they tell me. Is Mr. Rice on board now?”

A sailor who was washing several articles of clothing by beating them on the rocks near the water’s edge looked up.

“No,” he said. “Senhor Rice is not here. He never travels on the Aguila—it is not good enough for him.”

“Doesn’t he ever visit Manaos?”

“Yes, when there is some good reason for it but he always uses the Indio which is larger and much finer; you should see it. The Aguila is for the peons and the cook when they come to buy provisions.”

“Where is the Indio now?” David was becoming somewhat uneasy.

“At Las Palmas.”

“Didn’t Senhor Rice say anything about coming to Manaos in the near future?”

“He never talks to the peons, so I don’t know.”

“You see,” David explained, “I am on my way to the ranch and they were to send for me.”

“Si, Senhor.” The man now stopped washing and listened respectfully.

“Did you hear anything about that?”

“No, Senhor.”

“When do you start back?”

“This afternoon.”

“Today?” in surprise. “When did you arrive?”

“Two days ago.”

“There must be a misunderstanding somewhere. I have been waiting a good many days and this is the first I heard of your coming, and that was by accident. Who is in charge of the boat?”

“The captain. He went with the others to get some rice and other things. He will be back soon.”

“I’ll wait, then.”

“Yes, Senhor,” and the man resumed his washing.

Here was a new predicament he had not counted on. For a while he racked his brain in an effort to disentangle the puzzle, but it was of no avail. He was compelled to give it up. There was certainly a mix-up somewhere and that was all there was to it. By and by it would be all cleared up and he would then laugh at his present anxiety and vexation.

The captain arrived before very long, followed by three men carrying heavy bags on their shoulders. He was a thick-set, burly fellow and one could tell at a glance that he was accustomed to giving orders which others dared not hesitate long in obeying. A stubby beard covered the greater part of his face effectually, concealing his features—all but the eyes—small, black and penetrating. A flat cap with a long peak was perched on the top of his head, the black hair, touched with gray, appearing under the rim in a dense, unkempt ring.

That head-dress, David was to learn later, was typi{46}cal of the masters of the smaller river craft and was their only badge of position and authority for, otherwise, they were dressed exactly like their ragged crews.

David did not like the looks of the swarthy newcomer. But that did not matter. He wanted to get to Las Palmas and the man possessed the means of getting him there.

“My name is David Jones and I am from New York,” he said by way of greeting. “I have been waiting a long time for you.”

“Me? Why have you been waiting for me? What do you want?” the captain asked in surprise.

“I want to get to the ranch. Didn’t Mr. Rice instruct you to bring me out?”

“I don’t know anything about it. Nobody said a word to me.”

“Well,” David tried to conceal his impatience with a laugh, “I am expected at the ranch and I want to get there so soon as possible. I can have my baggage here in fifteen minutes.”

The captain was looking at him sharply, even suspiciously.

“Do you think this is a passenger boat?” he asked. “We don’t carry strangers without a written order from the boss.”

“But this is different,” David protested. “I am not a stranger. They are looking for me. Mr. Rice must have misunderstood the date or he would have been here personally.”

“That is not my fault,” said the captain gruffly.

“But I can go with you, can’t I?”

“No! If you knew the boss you would not ask me to take you. He is awful when anyone does a thing he don’t like. He killed a man for that very thing last week.”

“I am not afraid he’ll kill me.”

“Neither am I. I don’t care what happens to you but I do care what happens to me.”

“How soon is the Aguila coming back to Manaos?” said David in despair.

“Not for six months. Next week she starts on a long trip to carry supplies to the rubber camps upriver.”

“And the Indio?”

“The Indio has a broken propeller. They sent for a new one but it generally takes a year to get anything from abroad.”

“Say,” David was wiping his face in desperation, “I have to get to Las Palmas and that is all there is to it.”

“I have nothing against it. Get there any way you like—but not on the Aguila.”

A sudden idea came to him. Perhaps the fellow wanted money.

“I’ll pay you well. How much do you want?” he asked.

The Brazilian straightened up; his eyes blazed.

“Are you trying to bribe me?” he bellowed, “and right in front of my men? If you are, you’re insulting me. I am paid for my work and I want none of your money. A fine person, you are, to try to buy me to disobey my chief’s orders.”

“I did nothing of the kind,” David returned hotly.{48} “I offered you money to pay my passage because I could hardly ask a stranger to carry me for nothing.”

“Well, I accept your explanation, but you will not go, just the same. That is settled—understand? I am very busy.” This was said in such a manner that David could not fail to grasp its significance.

He was in a quandary. It was just one discouraging thing after another. Would matters ever become straightened out? He must go on that launch, for had not the burly captain told him there would not be another in months? He made one more desperate effort.

“I am going on the Aguila whether you like it or not. And when I get to Las Palmas—” he began, but the captain stopped him.

“Talk all you want to, but if I catch you aboard my boat I’ll throw you into the river,” he threatened.

David looked at the man and knew he would keep his word. His mind worked fast; he thought of one other thing.

“How soon do you start?” he asked.

“In two hours.”

“Will you take a letter for me?”

“Yes, I will take a letter or as many as you want to send, but I will not take you, so don’t ask it again. Las Palmas is no place for a foreigner. It is terrible there—snakes, insects and fevers. And the boss treats us like dogs.”

David ignored these remarks.

“I’ll go to the hotel to write the letter and will bring it to you in less than an hour.”

He hastened back to his room to prepare the missive, and ignoring a first impulse to write all that had occurred during the last hour, he only stated that he had arrived and was eager to reach the ranch, but had no way of doing so.

“When Mr. Rice gets this he’ll ask the captain questions and then he’ll be furious at the way I have been treated,” he thought. “And he’ll make him turn right around and come back for me. Then it will be my turn to show off, just as he did, and it will serve him right. He will soon find out who I am.”

He hastened back to the river to deliver the letter, and as he thought the matter over he was glad he had omitted all reference to the captain, for the latter would doubtless read it and if he found anything too personal he would destroy it.

Bad as it was, his position could have been a great deal worse. It was now a question of only a few days more of waiting. That was a certainty.

But when David reached the river, breathless and perspiring, a new calamity awaited him. The Aguila was gone.

He looked up and down the river; there was no sign of the boat. As he stood on the sand, too stunned to move, a sailor came up to him and spoke sympathetically.

“Are you looking for the Aguila?” he asked.

David subconsciously murmered assent.

“She left over half an hour ago—right after you went away.”

“Thanks.”

David turned and slowly walked away. Try as he would to banish the feeling, there was no denying the fact that his experiences were beginning to dim the glamor of the life he had longed for; and that, too, in the face of the fact that so far he had accomplished absolutely nothing.

He went to the post office and mailed the letter, hoping that somehow or other it would reach its destination.

David felt sure that he was the most luckless of all persons. So far, about everything had gone wrong. But there must be a turning-point somewhere. It was strange how a single misunderstanding could cause so much confusion.

To make matters worse, regardless of what happened he had to accept the situation in apparent good humor, for he dared not assert himself too strongly. If there had been trouble, he would have been blamed, fairly or unfairly; that had been, almost invariably, his experience. Rather than take a single chance at spoiling this opportunity of a lifetime he would suffer in silence. But when the day came, as it surely would, when he had won his spurs, he would demonstrate that he could direct affairs as well as obey the orders of others.

He had wanted to thrash Rogers; and the American Consul should at least have been told that his duties did not include meddling in other people’s business. As for the gruff captain of the Aguila—he should receive his dues when the time came; Mr. Rice would of course make him regret his rude conduct toward his guest.

When David reached his hotel his indignation was still at the boiling point. He must relieve his mind to someone and that person, unfortunately, was the owner of the hotel, for he happened to be the first one he chanced to meet.

He told him the whole episode from beginning to end omitting none of the details. The man listened attentively until the recital was finished. Then he grunted, with an amused expression on his face.

“Hum! I think he did right in not taking you. His orders were clear.”

“Yes, but how about the letter? He said he was leaving in two hours and then went in half an hour.”

“There may have been a reason for the change. If you knew his boss you would not blame him for being careful. Las Palmas is a notorious place. Everyone who can, avoids it. Those who are there are slaves—they are afraid to leave. Rice has the reputation of being the worst character in the country.”

“That’s very interesting,” David retorted. “I am very glad to hear it because I had the idea that all ranch life had become tame and commonplace. It will be great to see a real place—I can hardly wait to get there.”

“And how are you going to get there?” the Brazilian asked with a smile.

“That is the question just now; but, once there, I guess I can look out for myself.”

“You can’t walk. It is many, many kilometers away. And the ranch boats, you say, will not be back in a long time.”

“Right! Still, I will find a way.”

“Let me assure you that you will not. Now listen. You do not know how lucky you are to have escaped that outfit at Las Palmas——”

“And next,” David interrupted, “you will be saying that there is a boat out of here for New York soon and I had better take it.”

The hotel man looked sheepish.

“I thought so,” David continued. “Save yourself any further trouble on my account. You take care of your business and I’ll tend mine. Please remember that.”

Leaving the astonished Brazilian he went to his room and spent the greater part of an hour looking out of the window at the little plaza across the street and—thinking.

“I can’t stay here any longer,” he finally concluded. “If I do I’ll get into a fight and I don’t want to fight. I’ll have to watch my step.”

He packed his belongings, slowly and without paying a great deal of attention to just what he was doing. When he entered the office and asked for his statement the owner of the hotel appeared grieved.

“Why are you leaving now?” he asked. “The boat does not leave until tomorrow.”

David gritted his teeth but smiled.

“I know it. But I am sailing out of here right now. How much is it? I am in a hurry.”

A moment later he stepped out into the street and turned in the opposite direction to which he intended going, knowing that inquisitive eyes were following{54} him. A few blocks away he entered a side street and then came back toward the center of the city. He found one of the smaller inns and secured a room without arousing comment. Now he felt more free to pursue the plan he had formed for, unknown and among disinterested persons, he was more apt to get the help and information he needed. Or at least there would be no interference.

He made no inquiries until late the following morning. Haste or a show of too great eagerness might arouse suspicion. And then, after artfully swinging the conversation he had started with the clerk to hunting and to big game, he casually inquired if it would be possible to hire a launch or boat of any kind for a trip up the river.

Much to his delight he was told that such a thing could be arranged without trouble. There were numerous craft leaving the port daily that would drop him at any of the little colonies or camps situated along the river bank. The clerk even gave him the names of several persons with whom arrangements could be made for such an outing.

To David the future seemed decidedly brighter and not long after he sought the first man on his list. After locating the man—the keeper of a small shop on the Rua Amazonas, and making a trivial purchase, he remarked that he might find it necessary to make a short journey on the river and was looking for a launch he could hire by the hour or day.

The Brazilian was quick to grasp the opportunity.

“My boat is at the disposal of the Senhor,” he said.{55} “It is a good boat, very seaworthy, and does not pitch or roll badly; that is important, for the river is so enormous and storms come up suddenly. Where do you want to go?”

“How much, by the day?” David countered.

“Sixty milreis. I will go with you and run the launch myself.”

David hesitated for a moment, as if pondering the proposition. Sixty milreis equalled twelve dollars.

“Well,” he said thoughtfully, “your price is pretty high but if the boat is extra good I guess I will take it. I want to start tomorrow.”

“How far do you want to go? I must know on account of the provisions.”

“How far can you go in one day?”

“Eighty or a hundred kilometers.”

“We can make it in a day then.”

“I shall be ready tomorrow, at any time you say,” the Brazilian said with finality.

David could have shouted for joy. At last he had found the way.

“I think an early start is best, don’t you?” he said as calmly as he could. “Six o’clock will be all right. So get everything ready today and then there will be no delays in the morning.”

“Very good. Now, exactly where do you want to go?”

Dark clouds again appeared on David’s horizon.

“To one of the ranches along the river,” he replied quickly.

“Yes, but just where? There are several and how will I know which one is the right one?”

“It makes no difference, as I am paying by the day. If it takes a little over one day I will pay you for two whole days.”

“That part of it is all right. But I am compelled to make out papers for the port officials when I carry passengers.”

“Make them when you get back. Then you will know just what to say.” The situation was desperate for David.

“I could do that,” he said thoughtfully, and again David felt elated. But after a moment the Brazilian continued, “There is only one place on the whole river to which I can take no one.”

“What place is that?” with bated breath.

“Las Palmas. That is the one ranch where a landing is forbidden.”

“Why? That is the very spot I am bound for.”

“I am sorry, but as I said, I cannot take you there. The owner is a foreigner. He is very terrible,” the Brazilian explained. “Nobody dares stop there without a written permit. It is all very mysterious and you should hear the tales that are told about the happenings at Las Palmas.”

David tried to laugh; he felt more like crying.

“It is different in my case,” he stammered. “I am expected there. Arrangements were made by cable for them to meet me here but there was some misunderstanding about the date. You will be taking no chances.”

“You do not know that outfit or you would not talk like that. I will not go.”

“I will give you twice your regular price.”

“Not for a million milreis! What good would they do me after I was full of bullets or poisoned arrows?” The shop-keeper was firm.

“Are they really so bad as all that?” David asked incredulously.

“Worse. Much worse. Once the government threatened to send soldiers there to investigate things and they sent back word to come on with the whole army but to bid it good-bye first for they would never see any part of it again. So you see what kind of people you are dealing with.”

“All right,” David assumed an indifferent air. “If you don’t want my money there are others who do.”

“Yes, Senhor. They are welcome to it.”

Seeing that argument was useless, David took his departure and went to the second man on his list.

The negotiations proceeded smoothly as before until it became necessary to disclose his destination. Then the Brazilian absolutely refused to go any further with the matter. Nor could he be swayed from his determination. He would go anywhere, even to Santa Isabel or the Cassiquiare that connects the Rio Negro with the Orinoco—trips of many weeks’ duration. But to Las Palmas? “Never!” most emphatically.

David was more crestfallen than ever as he went in search of the third man. “There is something very mysterious about all this,” he thought. “If it is really such an awful place I had better keep away from it.{58} But I have to see it first. I can leave if I don’t like it—that is, if I ever get there.”

The interview with launch owner number three was shorter than the other two. This man was gruff, even discourteous, and wanted to know first of all where he wanted to go. And when David told him, he simply shrugged his shoulders, said “No,” and walked away.