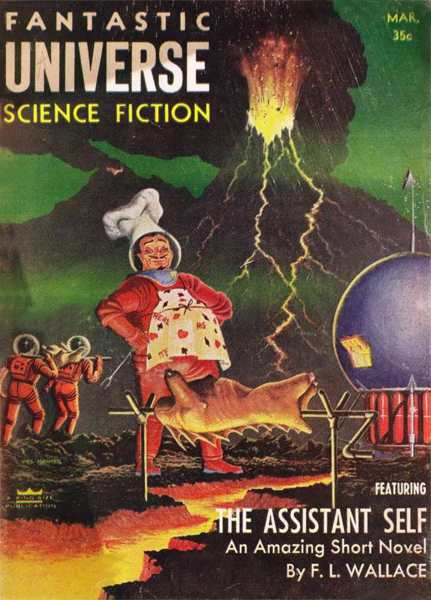

Title: Testing

Author: Sam Merwin

Illustrator: Mel Hunter

Release date: November 27, 2025 [eBook #77357]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: King-Size Publications, Inc, 1956

Credits: Sean/IB and Tom Trussel

by Jacques Jean Ferrat

The patriarch had the strength and courage of a young man. But only the wisdom of the very old could prevent a terrible war.

The ebullient author of NIGHTMARE TOWER and WHEN THE WHITE RAIN CAME has done it again—achieved a near-miracle of reporting in the wondrous bright purlieus of tomorrow. We’ve often wondered whether Jacques Jean Ferrat actually travels into the future to observe its liveliest attributes or simply peers through one of those remarkable “peepholes in Time” which open up occasionally. Whatever his technique, the results are delightful.

A terrestrial journalist once described the plight of a space pilot on a solo interstellar trip as being similar to that of a flea on one of the great stone dogs of Planet VI, Betelgeuse. All that vast expanse to plunder and no way of getting at it.

To Echelon Leader Hannibal Pryor, the simile was apt. It was aggravated by the fact that he was an unwilling flea. If his chief and sponsor, Star Marshal Stefan Lopez, had not backed the losing side in the last Sirius IX plebescite, Pryor would have been piloting the immense star-battleship Erebus, from which the planet-buster was to be dropped. Instead, he had been assigned this miserable chore of checking Rigel IV, the planet scheduled for blasting.

It was a job that should have gone to a mere ensign, not a veteran echelon leader with three comets on his breast. There was nothing to do. His survey route had been plotted in advance by the calculators that crammed the deck below and precision instruments did all the checking. If Rigel IV were habitable or inhabited, it would not have been selected for the test.

The flying laboratory in which he sat would circle it twice, then return under automatic control to the dot in space, 3,000,000 kilometers away, five o’clock vector, where ships of half the inhabited planets were gathering to watch the test.

Wellington Smith, the new chief star marshal, had his own pet pilot for the big job. Hannibal Pryor, as one of Lopez’ top men, was out of the big picture.

Flying the preliminary milk run! It made acid flow in his veins. And he was getting fat from punching out weird gastronomic combinations on the food-board. There was nothing to do but eat—and swill up the non-intoxicating drinks available through the dispenser.

The way things stood, Pryor knew he’d be lucky if he made wing chief in ten years Earth-time. Once you were out of the big picture, it took a miracle to pull you back into focus.

Idly, Pryor lowered his long dark-skinned body into the observer’s bucket, and watched the small golden dot that was Rigel IV swiftly enlarge itself on the screen. It took on a bluish tinge and acquired the fuzzy halo that denoted an atmosphere.

The scientists, prodded by the political leaders of Sirius Sector, had selected for the sake of thoroughness a planet known to be habitable, though uninhabited, at least by human beings. The planet-buster had already been tested on the airless satellites of one of the dark stars.

Without much interest, Pryor watched Rigel IV fill the screen, gradually become convex. He had landed on far too many worlds to be frightened by the effect of its falling upon him as he neared it. Half-subconsciously, he noted that the star-brakes were working perfectly.

He felt the faint jar as the atmosphere engines took over from the star-drive. The little lights on the panel flared and flickered in proper sequence as the flying laboratory began its first circuit of a world that was soon to be blasted to stardust.

Later, he realized that he must have dozed off. At any rate, he missed the flicker of green light at the left of the panel and it took the rasping electronic voice that unexpectedly called, “Pilot control, pilot control, pilot control,” to awaken him.

He muttered, “Diamede!” in sheer disbelief, as he pushed the button that turned off the voice and took over the controls. It couldn’t possibly have happened and yet—the instruments were never wrong.

Rigel IV was inhabited—by humans!

As he brought the ship in along an ever-slowing parabola, Pryor pulled the outspeaker over in front of his mouth and said, “Lab Able calling Erebus, Lab Able calling Erebus. Locator shows humanity on Rigel Four, locator shows humanity on Rigel Four. Over.”

He held course and watched the seconds tick by on the call chronometer. Eleven, twelve, thirteen ... thirty-five, thirty-six ... A burst of gibberish emerged from the inspeaker until he tuned the unscrambler and heard, “I hear you, Lab Able. Check for inhabitants and arrange immediate evacuation, check for inhabitants and arrange immediate evacuation. Report when assignment complete, report when assignment complete. Time is of the essence, time is of the essence. Over and out, over and out.”

Pryor wrestled with temptation. If he put another message through, unscrambled, stating the situation, Interstellar Control monitors would inevitably pick it up. Interstellar Control was death on any interference with inhabited planets. Interstellar Control was already on record as being against the planet-buster test on a usable world. And not even the new chief star marshal was strong enough to buck IC.

Pryor smiled and hummed a little Antarean tune as he slowed Lab Able to hovering speed. If he handled the situation adroitly, he should be able to get Marshal Lopez out of the doghouse—and, quite as important, one Echelon Leader Hannibal Pryor back in the big picture.

According to the instruments, the humans on Rigel IV lived in a single small settlement in the south temperate zone of the planet, surprisingly close to the forbidding antarctic ice-cap.

Pryor cut in distance-detail vision and blinked unbelievingly at a cluster of thatched roofs about a strangely familiar structure with a tall white pointed spire. The fields about the settlement, where they did not show cultivation, bore an odd pale purple hue. Beyond the village lay a long, narrow, twisting body of pale blue water.

Pryor spotted a level spot that looked suitable for landing, clear of the tilled fields. His mocha colored fingers played the panel-buttons like the fingers of an organist ringing in stops, as he prepared Lab Able for its descent.

Emerging from his ship, Pryor discovered that the pale purple fields were actually covered with a sort of low, tough shrubbery. It covered the sparsely-treed hills beyond the lake and seemed to fade into the deep misty blue of the afternoon sky.

Although he had never seen a landscape like it, in all his roving over scores of planets, Pryor found it pleasant. A strong, cool wind whipped his weatherproof coverall against the backs of his legs. After the artificial atmosphere of Lab Able, the fresh air stung his nostrils pleasantly. And the smell of the pale purple shrubbery was sweet.

He scrambled over a low barrier of uncut gray stone that marked the boundary of the field in which he had landed and found himself on a narrow road of ochre-hued dirt. He trudged along it, toward the village, and around a dipping bend met two men riding in a surface car of fantastically ancient vintage. If Pryor had not seen similar vehicles in his histofilm course at the academy, he would scarcely have known what it was. It actually ran on wheels with plastic rims.

It pulled to a halt alongside him and the red-bearded patriarch sitting next to the young man at the controls, leapt spryly out and said in odd thick accents, “Welcome to Leith on Nevis, sir.”

The older man had to repeat the greeting before Pryor found words. There was so much that was astonishing about him. First, his clothing. It consisted of stout shoes of what looked like real leather, long woven socks in brilliant diamond checks, a brief black jacket and a sort of skirt woven in a complex pattern of blue-and-green checks and kept from flaring in the wind by a heavy pouch of some sort of fur.

A sort of blanket that matched the skirt was slung over his left shoulder and an odd-looking flat black bonnet, turned up on one side by an elaborate metal clip, had a headband of the same bright material.

Second, his beard. For centuries, all male human children were given facial depilation shortly after birth, and as a result, the old man’s luxurious red growth looked both alarming and unsanitary. Third, his skin. It was like that of the young man engaged in turning the vehicle awkwardly about, a pale reddish pink that made Pryor conscious of his own dark normality.

When he had recovered from his surprise at encountering such a strange specimen, Pryor returned his greeting and asked to be taken to the chief or leader of the community.

The younger man, who had pulled up alongside again but facing the other way, said, “You’re speaking to the Dominie now, sir.” His accent was as alien and thick as that of the man with the beard. And his costume was similar save for minor details.

On the way to the village, they had to halt while a flock of baaaing gray sheep, tended by a husky-looking youngster and a long-haired black-and-white dog, crossed the dirt road. Pryor, who had never seen anything like them before, asked what they were, what they were for.

The older man smiled and said, “Their wool supplies us with the clothing we wear. Their hides provide us with light leather. Their flesh provides us with meat for the table.”

Pryor nodded, wishing he hadn’t asked. The idea of eating the flesh of living creatures—or recently living creatures—appalled him. He had an idea he wasn’t going to enjoy his dinner.

The village, with its stone houses and thatched roofs reminded Pryor of a village in a fairy tale vidarfilm. He noted with growing amazement that all the inhabitants seemed to be fair of hair and skin, all wore the gay skirts and bonnets, regardless of sex. He was asked to alight in front of the largest house, one close by the stone church with its white wooden spire.

The Dominie led him into a room of wholly unexpected comfort and applied flame to a pile of cut logs in a wide stone fireplace.

This done, he produced two earthenware mugs and a stone bottle and said, “I doubt not but that your mission to Leith on Nevis is important. It is only fitting we indulge in a drop before we come to such matters.”

The Dominie drained his mug without changing expression, but the innocent looking amber liquid made Pryor gasp. It seemed to burn his gullet and, seconds later, start a warming fire in his veins. When he could talk, he gasped, “What was that, Dominie?”

“That,” said the older man, smiling through his beard, “is uisquebaugh, the water of life, known to the less ancient as whiskey.”

“I’ve heard of it,” Pryor managed. He wondered if he weren’t dreaming the whole business, and shook himself mentally in an effort to awaken in the prosaic surroundings of Lab Able. But nothing changed.

“I’m afraid,” he said, “I’ve brought you a problem, Dominie.” He wondered what the word meant. “I’ve got orders from headquarters, Sirius Sector to have this planet evacuated at once.”

Courteously, the older man refilled Pryor’s mug, then poured more liquid fire into his own. He said, “And what is the alternative?”

“There is no alternative,” Pryor replied bluntly. “In a matter of thirty-six hours, Earth-time, this little world is going to be blown to smithereens.”

“I’ll say one thing for you, young man,” said the Dominie. “You don’t believe in beating about the bush.” He drained his mug once more, and added over its rim, “Is the universe at war?”

“Not at present, I’m happy to say,” said Pryor.

“Then I fear your errand is wasted,” said the other. “If there is no war, then we shall not evacuate. Even if there were, I should hesitate to uproot my people. They would have to leave so much of what they have wrought and love behind them.”

“I assure you,” said Pryor, wondering just how stupid the patriarch was, “that you will receive ample compensation.”

“Can you then arrange ample compensation for human hearts?” the old man asked.

Pryor braced himself and drained his mug. To his surprise, the whiskey or whatever it was, went down smoothly. He said, “I’m afraid you don’t understand the situation, sir. This planet, Rigel Four, is the subject for testing of the deadliest new bomb ever made. The experiment is already under way. You and your people must evacuate. Of course, if our plotters had known of your existence—”

“They’d have selected another world to blow up,” the Dominie finished for him. “I fear they’ll have to make the change anyway. Our title to this planet is quite clear and above-board. Allow me to show you.”

He rose, crossed to a lovingly carved and polished cabinet, and withdrew not a vidiroll but some actual ancient documents, handed them to Pryor.

Pryor looked at them with growing excitement. It was a planet charter, beyond question, granted some two centuries before by Interplanetary Control, the predecessor of Interstellar Control. It stated that Arnold MacRae, Ian Stephenson and Alexandra Hamilton had purchased, in goods, cash and services, the full rights to Rigel IV, hereafter to be known as Nevis. It added that the rights were to run in perpetuity, save only in the case of interstellar war and then only during the existence of a state of war.

Somebody had slipped when Marshal Wellington Smith selected Rigel IV for his planet-busting test. Pryor suspected the listing of this world under Nevis, among the titled planets, rather than as Rigel IV among the untitled, plus the antiquity of the deal and the small size and isolation of the settlement, had caused the error.

He stood up, noting that the floor seemed to slant where it had been level when he entered. He said, “There’s been a serious error, I fear. Can you have me driven to my ship at once? I must report it while there is still time.”

“Certainly, young man,” said the Dominie, rising.

Back in Lab Able, Pryor ran his hands over his face, which felt unreasonably hot. He punched in the outspeaker, called the Erebus and explained the situation. At its conclusion, he added innocently, “Shall I call in Interstellar for checking and aid? Over.”

He had to wait almost half an hour, Earth-time, for the reply to come through. In the meantime, he could picture the consternation among the smug brass hats on the flagship. He hummed the Antarean ditty again, feeling strangely relaxed and comfortable.

Finally it came through. When he got it unscrambled, it was orders to sit tight while higher authority dealt with the situation. He signed off, chuckling, and went back outside to the ancient surface-car, where the young man and a young woman were waiting for him. He had left the message recorder on, resolved to return in two hours for further orders. If there were none, he was going to call in IC. Come what might, he was back in the big picture with a vengeance.

When they reached the Dominie’s house, the girl said, “When you’re through eating, perhaps you’ll come to the kirk vestry. We’ll be having a small dance.”

He looked at her more closely and, in spite of the rosy and unnatural whiteness of her skin, noted that she was comely. He resolved to visit the kirk vestry as soon as politeness would permit, whatever a kirk vestry might be.

He drank more of the Dominie’s uisquebaugh before dinner and found himself asking, “Pardon me, sir, but would you answer one question?” And, at the older man’s nod, “Why are you so few?”

“We are few by choice,” was the reply. “Our forefathers long ago left Earth for Proxima Centauri Seven, in one of the earliest migrations, to escape overcrowding. My people and I like room to breathe in, room to roam and work without restriction. When PC Seven grew too crowded, we pooled our resources and purchased this world. In those days, planets such as this were cheap enough. The Control was glad to have them settled. Since then, we have limited our numbers to avoid a repetition of what went before.”

Thinking of a life spent in the crowded cities of crowded planets or in the cramped quarters of starships, Pryor understood. It had been in search of space and freedom that he had joined the service—only to exchange urban jamming for the prisons of strict discipline and limited space.

“You’ve created a dream,” Pryor said.

The Dominie put down his empty mug and said gravely, “Don’t think it’s been easy. Adapting to the most hospitable alien world is a backbreaking job. But we’ve never been afraid of work.”

“I can see that,” said Pryor, feeling oddly useless. He wondered how he would fare without buttons to push, circuits to serve him.

The Dominie’s wife, a tall, handsome woman with the frame of a percheron, appeared and announced that dinner was ready. Thanks to the whiskey, or perhaps to his absorption in his exotic surroundings, Pryor found himself actually eating meat—and actually enjoying it. The mutton was crisp and black on the outside, tender and pink in the center, and the vegetables and fruits served with it constituted a rich new experience.

During the meal, the Dominie’s wife said, “Tell me, Mr. Pryor, if the universe is not at war, why do they wish to blow up our planet?”

Pryor explained as best he could—and, unexpectedly, he seemed to be thinking and expressing himself more clearly than ever before. He told them about the rise of the aggressive elements in Sirius Sector, about the plebescite that had put Wellington Smith in power.

“They’re fretting under the restrictions of IC,” he said, “and they’re seeking to gather sufficient strength to obtain concessions. As long as they remain within IC limits, they can’t be touched.”

The Dominie said quietly, “It’s the same dreadful story, Mary. Too many people, too many unhappy people, restlessness, conspiracy, war. This time the whole universe will suffer.” Then, to Pryor, “But if your Star Marshal obliterates an inhabited IC planet, he’ll be in trouble, will he not?”

“If he should dare do such a thing—and I feel sure he won’t,” said Pryor, “he’ll be as good as ruined.” For some reason he added, as an afterthought, “That is, if IC hears of it.”

“I see,” said the patriarch, nodding thoughtfully.

His wife said, “There’s a dance in the kirk vestry this evening, Mr. Pryor. I hope you’ll be in attendance. Naturally, you’ll honor us by being our guest overnight.”

Pryor found the kirk vestry without trouble. It was an extension of the big building with the white spire and less than fifty meters from the Dominie’s house. He intended merely to get someone to drive him to his ship and get his message out. But when he heard the shrill, rhythmic combination of bagpipes and fiddle, something stirred deep in his ancestral memory and he forgot about all else.

He danced with the girl of the surface-car and she showed him the steps of the strange dances and his feet had magic in them. He laughed with the men and drank more of the whiskey and the night became a golden whirl of primitive excitement such as he had never known. He needed the help of two of the young men to get him back to the Dominie’s house, where he was undressed and put into a soft warm object they called a bed.

He knew no more until the concussion of the explosion brought him sharply out of his drunken slumber. Although his tongue was thick with fur and his head rattled as if it were filled with dried pebbles, he woke up sober.

Through the bedroom window, he saw the flickering brilliance of the exploded bomb mounting slowly toward the stars. He turned and, with a strange sickness in his stomach, scrambled into his clothing. Outside, he could hear the little community coming to life.

He hadn’t believed they would do it. When he got out of the vehicle, he saw an odd little mound of molten metal where Lab Able had stood in silver serenity a few minutes earlier. Silently, he cursed the ruthless militarists who were going to blast Rigel IV to dust, and cursed his own irresponsibility for not sending the message that would have put a halt to their plans.

Somebody said in the odd accent that was already becoming familiar, “What happened, Mr. Pryor?”

Pryor thought fast though his head ached badly. He said, “I fear the drive fuel reached critical mass. It happens once in a hundred thousand times.” It hadn’t, it couldn’t, but how could he tell them they were as good as dead?

And himself with them, of course. But he didn’t waste time thinking about that.

When he got back to the Dominie’s house, the wife greeted him gravely. She wore a soft wool robe, and her hair was in odd wisps of paper, and he could tell by the way she looked at him that she knew.

“Where can I find the Dominie?” he asked.

“He’s in the basement of the kirk,” she said in her soft untroubled voice. “He asked me to ask you to join him there.”

“Thanks, ma’am,” Pryor replied. There was nothing more to say.

The light was dim in the basement. The place smelled of age and dampness. But there was machinery there, a vast pile of it, and the Dominie was fussing around it, wearing a frown.

“Ho, there, Pryor,” he said. “So they blew up your ship?”

“They blew her up,” said Pryor grimly. “I never thought they’d dare. If only I hadn’t made an idiot of myself at the dance, I’d—”

The Dominie cut him off with, “It’s a bit late for regrets, young man. Come see if we can get this blasted communicator working.”

Pryor’s heart leapt. For a moment, he thought he was gaining a reprieve. Then he saw the age and condition of the old set—it was at least a century old—and realized they’d be lucky to get a message out at all before the big one blew them to nothingness.

“Come on, Dominie,” he said, “let’s have that wrench.”

They worked through the short night and into the morning that followed. The Dominie’s wife brought them a strange herb brew she called tea, that reinvigorated them. She said, to Pryor, “Sheila and the other girls are very excited. They believe you’ll be staying a while now. You’ll be the first stranger in many years.”

Pryor wiped his brow grimly and said, “Well, I’ll be here as long as any of them, I guess.”

“Then there’s no hope?” the Dominie asked quietly over his tea.

“Oh, we’ll get a message out to the IC,” said Pryor. “We’re almost ready to send. But it will be too late. The bomb is already on its way.”

“Come on then,” said the Dominie, handing his tea back to his wife. “Let’s waste no time.”

They got the message out, before the reddish sun reached the Meridian. And Pryor said grimly, “That makes their second mistake. They should have blasted the town last night, not just my ship. Their first mistake was in selecting this planet.” He looked about him at the placid, happy scene, and suppressed a heaving sob.

The Dominie put a firm hand on his shoulder and said, “Perhaps it’s best this way. Perhaps this is why we are here, to prevent the most terrible war of all. After all, there aren’t many of us against those who would die if your marshal got his way.”

Pryor said, his eyes shining with admiration, “You’re a great man, Dominie—and a brave one.”

“Let’s just say an old one,” said the patriarch. “And now, since we have so little time, let’s you and I walk to the edge of the loch and look at the hills on the other side. It’s a lovely view.”

This etext was produced from Fantastic Universe, March 1956 (Vol. 5, No. 2.). Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

Obvious errors have been silently corrected in this version, but minor inconsistencies have been retained as printed.