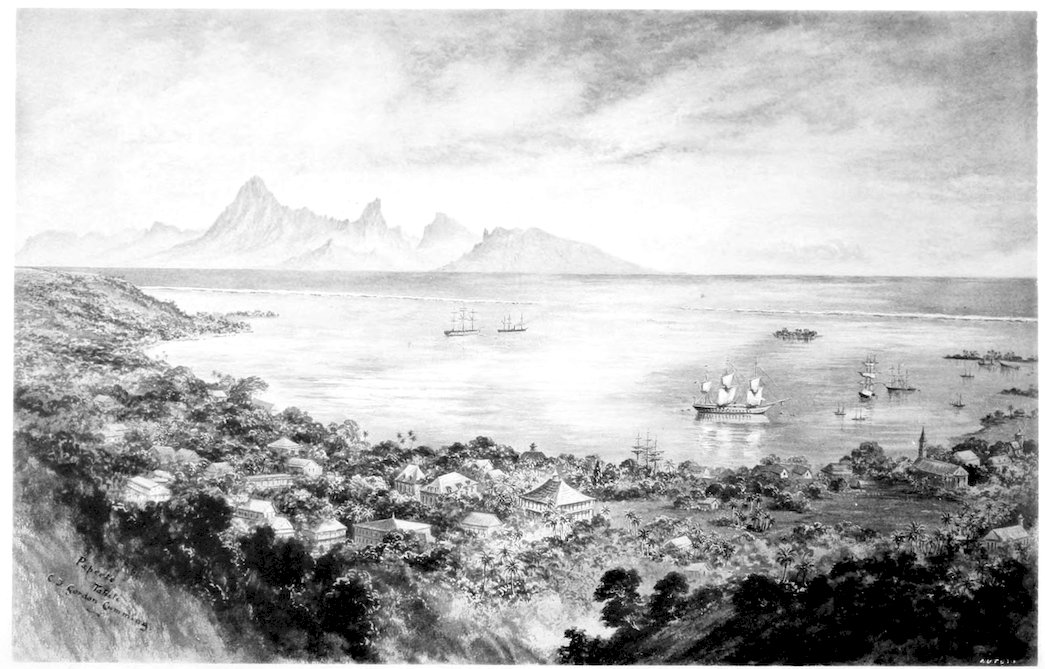

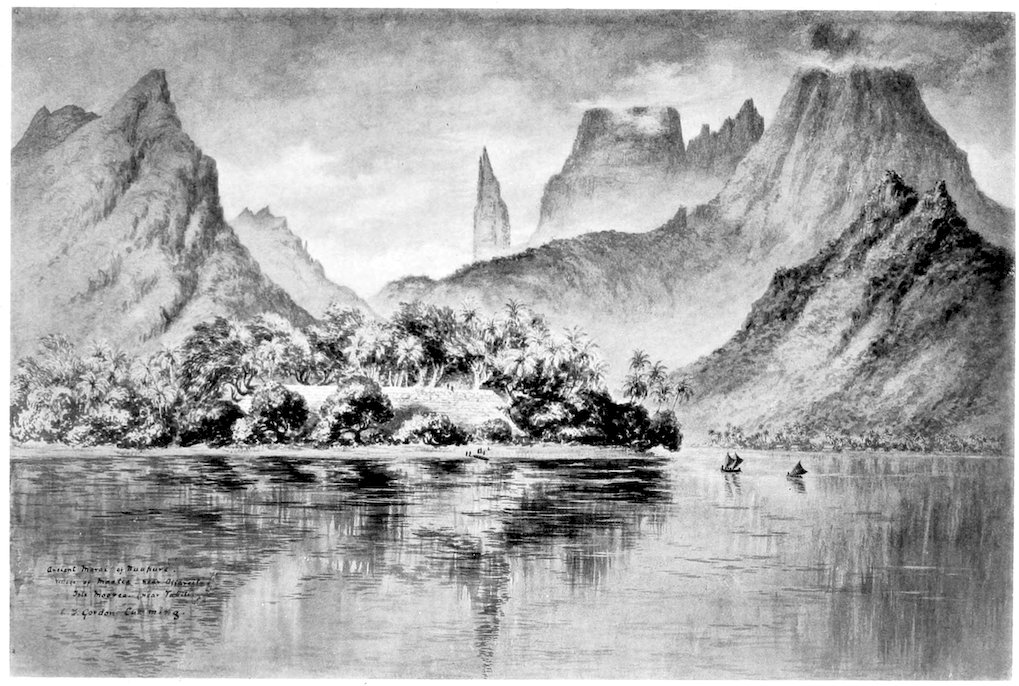

PAPEETE. CAPITAL OF TAHITI.

Title: A lady's cruise in a French man-of-war

Author: C. F. Gordon Cumming

Release date: November 27, 2025 [eBook #77356]

Language: English

Original publication: Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1882

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Peter Becker, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

PAPEETE. CAPITAL OF TAHITI.

When, in the spring of 1875, Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon was appointed first Governor of Fiji, I had the good fortune to be invited to form one of the party who accompanied Lady Gordon to that far country.

Two years slipped away, brimful of interest, and each month made me feel more ‘At Home in Fiji,’ more fascinated with its lovely scenery, more content to linger among its isles.

Then a counter-charm was brought to bear upon the spell which held me thus entranced. The chief magician appeared in the guise of a high ecclesiastic of the Roman Church, clothed in purple, and wearing the mystic ring and cross of amethyst; while his coadjutor, a French gentleman of the noble old school, was the commander of a large French man-of-war, which had been placed at the service of the Bishop of Samoa, to enable him to visit all the most remote portions of his diocese. Already this warlike mission-ship had peacefully touched at many points of exceeding beauty and interest, and our visitors had no sooner recognised my keen viappreciation of scenery, and inveterate love of sketching, than they formally and most cordially invited me to complete le tour de la mission, and so fill fresh portfolios with reminders of the beautiful scenes which the vessel was about to visit.

Being duly imbued with a British conviction that such an invitation could not possibly be a bonâ fide one, I at first treated it merely as a polite form; but when it was again and again renewed, in such terms as to leave no possible doubt of its sincerity, and when, moreover, we learnt that the most comfortable cabin in the ship had actually been prepared for the invited guest, and that its owner was thoroughly in earnest in his share of the invitation, then indeed we agreed that the chance was too unique to be lost; and so it came to pass that on the 5th September 1877 I started on the cruise in a French man-of-war, which proved one of the most delightful episodes in many years of travel.

While these pages were passing through the press, I have received details from various sources, which prove that the policy referred to at p. 241 is being actively carried out.

Not content with holding the Marquesas, the Paumotus, Tahiti, and the Gambier Isles, France seems resolved to annex every desirable island lying to the east of Samoa, thus securing possession of every good harbour and coaling station lying between New Zealand and the coast of South America; and also, diverting all the trade of these isles, from Britain’s Australian colonies, to a French centre, which shall command the great commercial highway of the future, when the Panama Canal shall be completed. Raiatea in the Society Isles has recently been formally annexed, and the independence of Huahine and Bora-Bora threatened.

Now a further step is contemplated. The Austral and Hervey groups still remain free. They are self-governed, and Christianity is firmly established among their people.

According to the latest information, a French man-of-war visited their principal isles last August, to command the inhabitants to divert their present trade from New Zealand to Tahiti, assuring them that Great Britain had undertaken not to interfere with viiiFrench action anywhere to the east of Samoa. The islanders, who had at first received the French vessel with all honour, no sooner got an inkling of the true object of its visit than they became alarmed, and returned all presents which had been made to them by the captain; who thereupon assured them that the French admiral was on his way thither, and would soon bring them to their bearings, and that they would have to accept a French protectorate.

Remembering the history of French protection in Tahiti, the Australs and Hervey Islanders are now justly alarmed for their own independence.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Letter to England announcing start from Fiji—Vague plans, | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Life in a French man-of-war—Convent-life in Tonga—Early martyrs—Wesleyan mission—Roman Catholic mission—Cyclopean tombs at Mua—Gigantic trilithon—Fines and taxes—King George Tupou, | 3 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Sail from Tonga to Vavau—Volcano of Tofua—Wesleyan mission—Two thousand miles from a doctor—Orange-groves—A lovely sea lake—Coral caves, | 24 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Life on board ship—The Wallis Isles—Fotuna—Sunday Isle—Cyclopean remains on Easter Isle—Stone adzes—Samoa—Pango-Pango harbour, | 33 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Boat transit to Leone—Spouting caves—Council of war—Sketch of Samoan history—Night dances, | 48 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A shore without a reef—Samoan plants—Houses—Animals—Laying foundation-stone of a church—School festival—the Navigator’s Isles, | 61 |

| x | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Vanquished chiefs of the Puletoa faction under protection of the union-jack—Convent school—“Bully” Hayes—Postal difficulties—House of Godeffroy—Village of Mulinunu—Vegetables and fish—Advantages of Anglo-American companies, | 74 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Ishmaelites of the Pacific—Injudicious intervention—Fa-Samoa picnic—A torchlight walk—Training college at Malua—Apt illustrations by native preachers—Dr Turner—Mission to the New Hebrides—Escape to Samoa—Of many changes on many isles, | 89 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| A sketch of the Samoan mission—The Rev. John Williams determines to visit the Navigator’s Isles—Preliminary work in the Hervey group—Discovery of Rarotonga—Conversion of its people—They help Williams to build a ship which shall convey him to Samoa—Visit Tonga—Proceed to Samoa—Overthrow of idolatry—Reverence for old mats—Williams’s grave at Apia, | 118 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Leave Samoa—Reach Tahiti—Grey shadows—Death of Queen Pomare—La Loire and her passengers—A general dispersion—Life ashore at Papeete—Admiral Serre and the royal family—Families of Salmon and Brander—Adoption, | 148 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Papeete—Catholic mission—Protestant mission—A christening party—La Maison Brandère—Tales of the past—Evenings in Tahiti—La musique—Plans—Sunday, | 164 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Short sketch of a royal progress round Tahiti, | 177 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The royal progress round Tahiti—Life day by day—Himènes—A beautiful shore—Manufacture of arrowroot flowers—A deserted cotton plantation—Tahitian dancing—The Areois—Vanilla plantations—Fort of Taravao, | 182 |

| xi | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The royal progress round Tahiti (continued)—French fort at Taravou—The peninsula—Life in bird-cage houses—Torchlight procession—Return to Papeete, | 198 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The semaphore—Immutable tides—The coral-reef—Spearing fish—Netting—Catching sharks—A royal mausoleum—Superstitions of East and West—Centipedes—Intoxicating drinks—Influenza—Death of Mrs Simpson, | 210 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The royal progress round Moorea—The Seignelay starts for the Marquesas and Paumotus—Indecision, | 226 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Vain regrets—Some account of the Marquesas and the Paumotu groups, | 236 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Tahitian hospitality—A South Sea store—A bathing picnic—The Marquesans—Tattooing—Ancient games of Tahiti—Malay descent—Theory of a northerly migration, | 267 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Life in Papeete—The market—Churches—Country life in the South Seas, | 286 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Visit to the Protestant mission on Moorea—A sketch of the early history of the mission, | 294 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| A healing tree—Plantation life—Vanilla crops—Cat-and-dog life—A foiled assassin—The tropics of to-day—England in days of yore—Among the crags—Infanticide—Heathen days, | 310 |

| xii | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Life on Moorea—An ancient place of sacrifice—Arrival of H.M.S. Shah—Hospitalities on land and water, | 322 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| The atoll group of Tetiaroa, | 335 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| New Year’s Day in Tahiti—Ascent of Fautawa valley—Of palm salads, screw-pines, and bread-fruit—Packing mango-stones—Return of Gilbert Islanders—Departure of the Seignelay, | 339 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Hurricane at the Paumotus—Mahena plantation—Watching for vessels—Farewell to Tahiti, | 353 |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

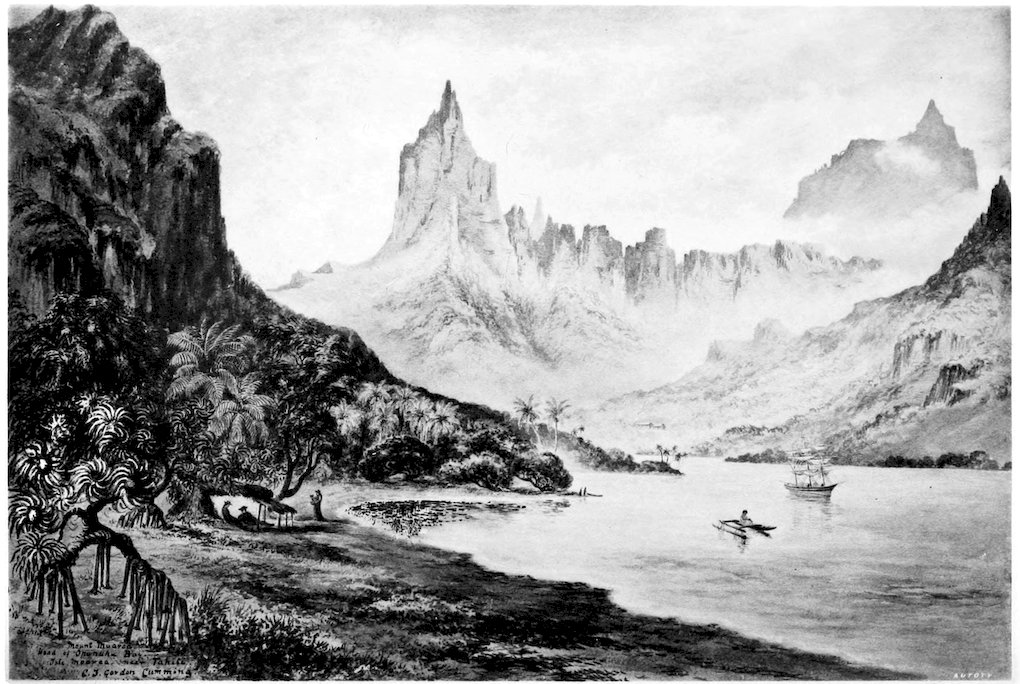

| Papeete—Capital, | Frontispiece |

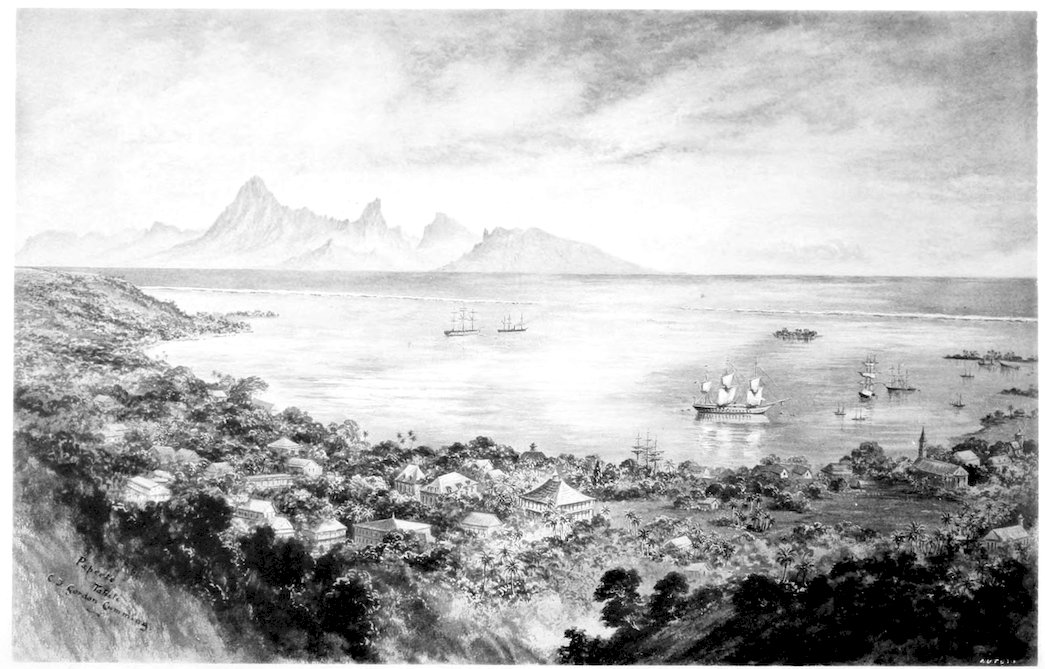

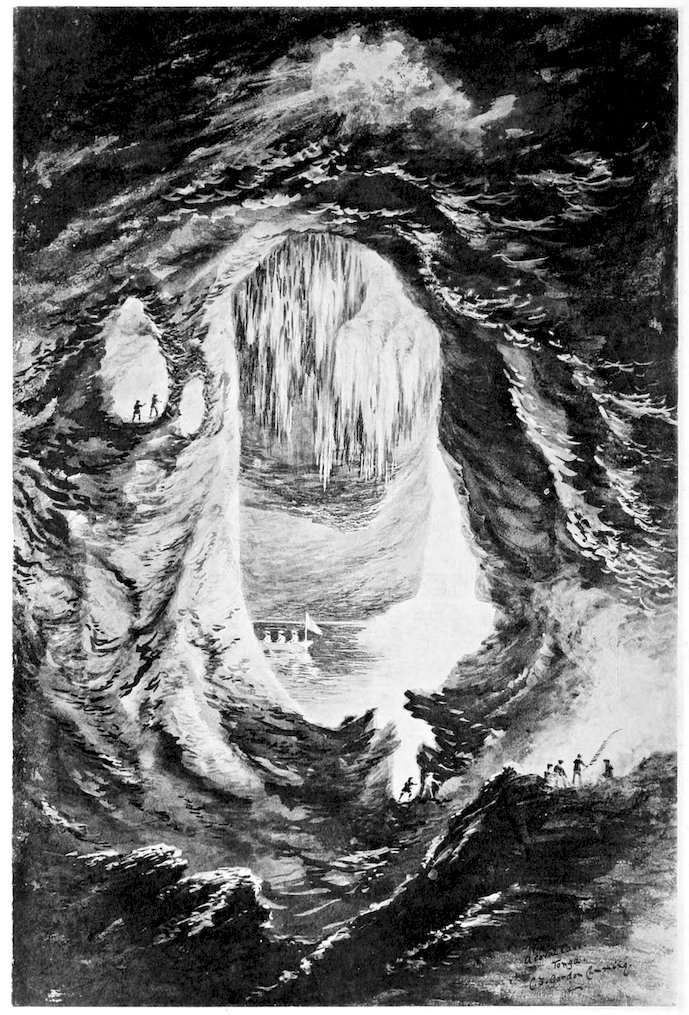

| Trilithon, Tonga, | 18 |

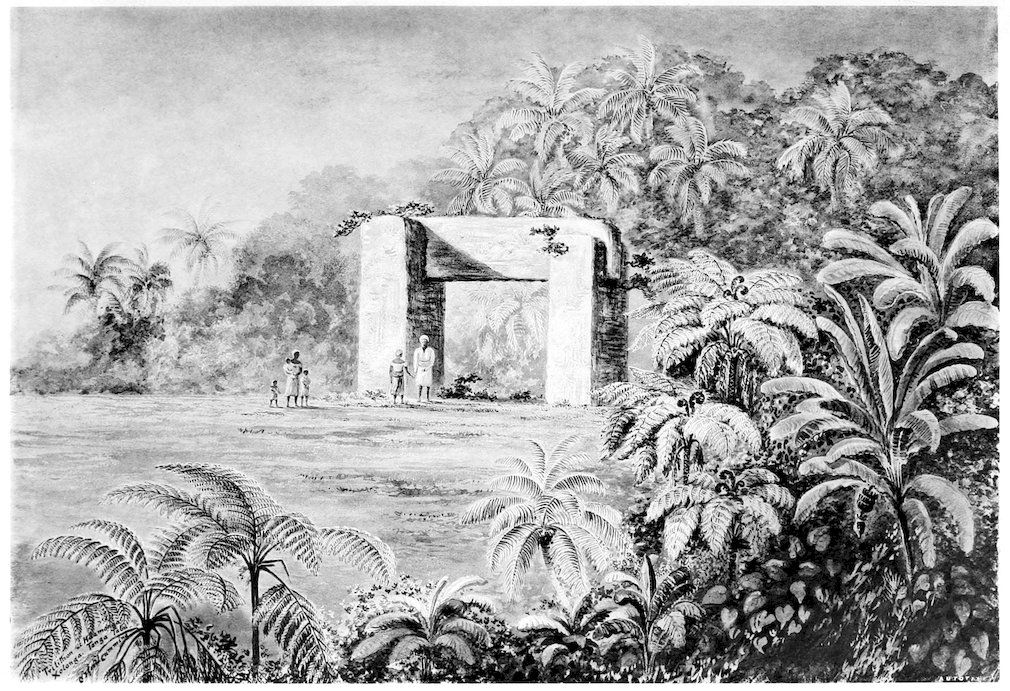

| A Coral Cave, Vavau, | 29 |

| Opunohu Bay, Moorea, | 153 |

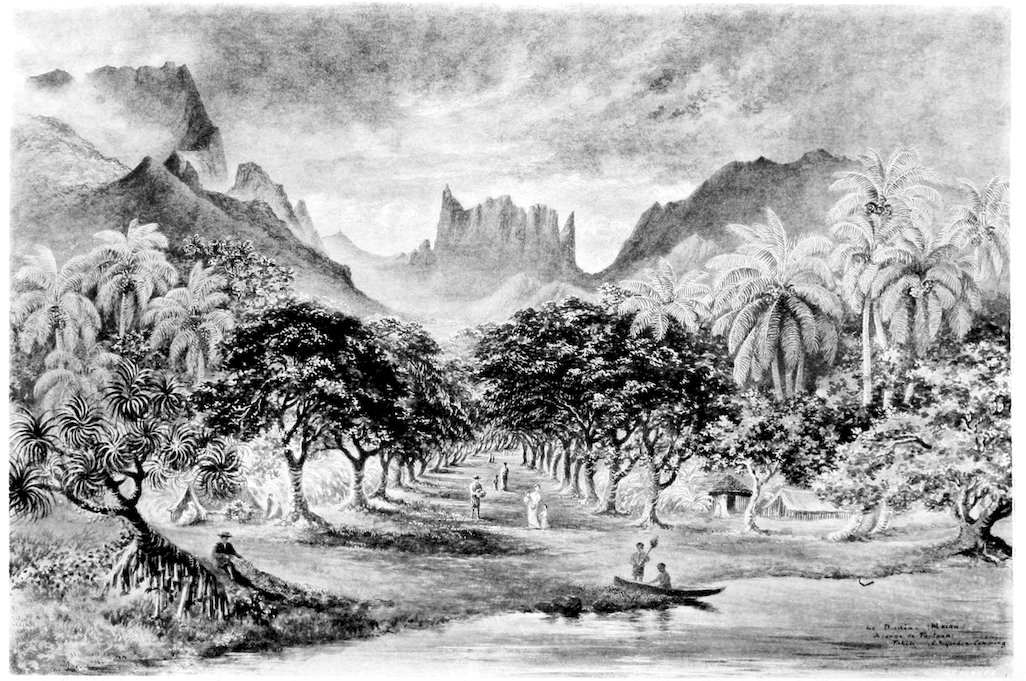

| Le Diadème, | 169 |

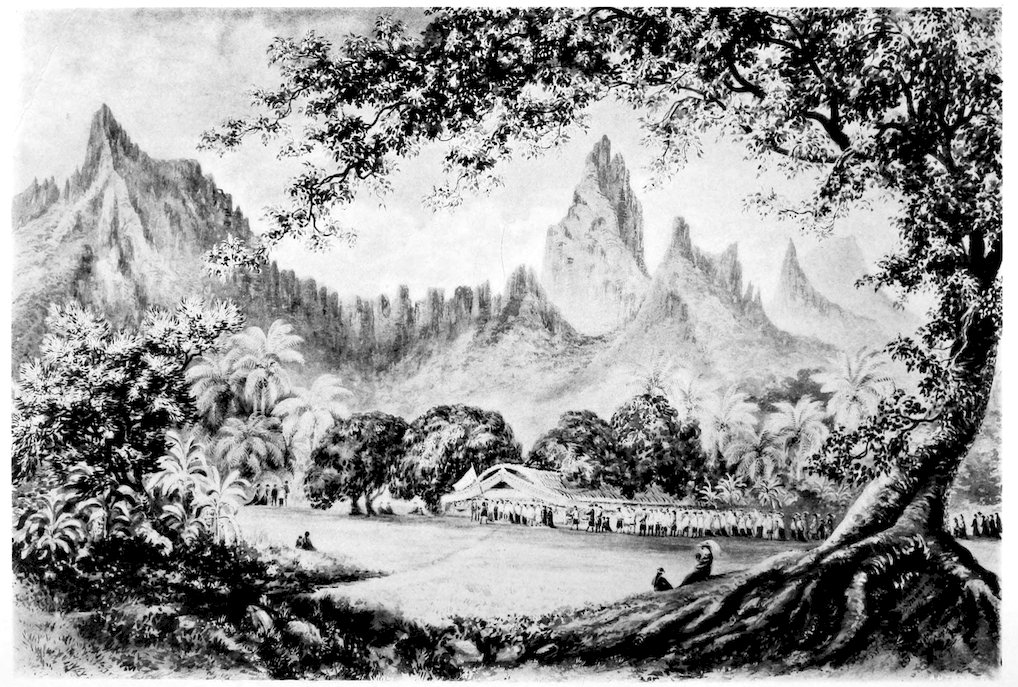

| A Royal Reception, Haapiti, | 229 |

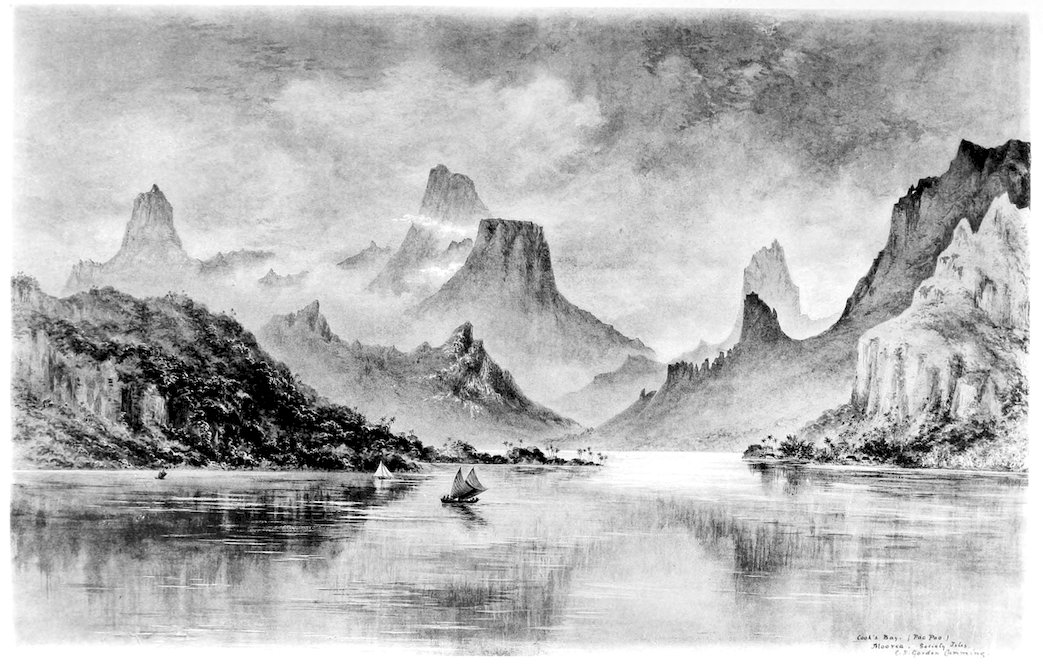

| Pao Pao, or Cook’s Bay, | 230 |

| Ancient Marai, | 324 |

| Map, | At the end |

The “Wa Kalou,”—i.e., “Fern of God,”—introduced on the cover of this book, is a most delicate climbing fern which overtwines tall trees and shrubs in the Pacific Isles, forming a misty veil of indescribable loveliness. When in the state of fructification, each leaf is edged with a dotted fringe of brown seed. In the Fijian Isles its beauty has gained for it the name here given; and in olden days the ridge-poles of the temples were wreathed with it, as those of chiefs’ houses are to this day. It also finds favour for personal adornment, trailing garlands of this exquisite green being singularly becoming to a clear brown skin.

My dear Eisa,—I have only time for a line, to enclose a packet of seed of a lovely shrub which bears clusters of golden bells. Also to tell you that I am just starting for a cruise in a French man-of-war, the Seignelay, commanded by Captain Aube, who is taking Monseigneur Elloi, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Samoa, a round of his diocese. Both are exceedingly pleasant, and have made themselves much liked here. The officers are a particularly gentlemanlike set. Judge of my amazement (accustomed to the rigid regulations of the English navy), when these, as one man, echoed an invitation given to me by the commander, to go for a cruise over half the South Seas, where they purpose touching at many isles, which I could by no possibility have any other chance of seeing. Several of these most kind friends had placed their cabins at the disposal of the captain, that he might offer me whichever he considered most suitable. For the first day or two after this invitation was made, we all treated it as a pleasant joke, never 2imagining that it could be quite in earnest; but when at length we all became convinced that it really was so, we agreed that there really could be no reason for refusing so rare a chance of an expedition, which will be to me most delightful.

So I am actually to embark this afternoon, Lady Gordon and dear little sailor Jack, and Captain Knollys, accompanying me on board, to see me fairly started.

This evening we sail for the Friendly Isles (Tonga), and thence proceed to the Navigator’s Isles (Samoa), where there have been serious disturbances, and where my friend Mrs Liardet, wife of the British Consul, has for some time had about thirty chiefs living in sanctuary in her house. I have long promised to visit her, should an opportunity arise, so this is an admirable one. I shall probably take a return passage thence in a German ship, and rejoin Lady Gordon at Loma Loma, a point in this group, about one hundred miles from here.

My French friends urge my going on to Tahiti, the loveliest isle in the South Seas; but the utter uncertainty of how to get back thence, either here or to Tasmania, where Lady Gordon hopes to spend Christmas, makes me hesitate. If I could reach the Sandwich Isles, I should then be on the direct line of the Pacific mail-steamers; but Tahiti is utterly out of the world, and till the Seignelay arrives there, she will not receive her further orders, and may perhaps be sent to Valparaiso, which has no attractions for me. So my line of march is at present somewhat undecided. I think I shall almost certainly return here from Samoa; but as B. long ago said, of my wandering propensities, that I was just like a knotless thread, I may perhaps slip through, and you may hear of my vanishing into space!

This place is looking lovely. It has improved wonderfully in these two years, and has become so very homelike and pleasant, that I quite grudge leaving it, with even the vague feeling of uncertainty which attaches to any long journey; and though we all expect to return here, after a winter in Tasmania, still, so many contingencies may arise, that one always feels a home in the colonies to be a very insecure tenure.

3Now I must finish my packing, which requires a good deal of consideration in case it should turn out that my locomotive demon urges me onward, and that I do visit the Hawaiian Isles, and then Tasmania, ere returning here.

I wish you could see my room here, now. It really is a museum—the walls covered with trophies of all the strange Fijian things I have collected during the last two years. I have just finished a series of about sixty studies of Fijian pottery, representing a hundred and fifty pieces, all different, and made without any wheel, by the wives of the poor fishermen. Some of the forms are most artistic, and the colour is very rich. No time for more. I will write next from Tonga.

Dear Lady Gordon,—I may as well begin a letter at once, in case of a chance of posting it by some stray ship, but as yet there is none even on the horizon.

Is it possible that it was only last Wednesday afternoon when you and Jack left me on board the Seignelay to try an entirely new experiment in ship-life—only three days since we ate our first méringues in that charming little dining-room, of which I now feel such a thoroughly old inhabitant? I can scarcely believe it.

Still more wonderful, is it scarcely a fortnight since I first met the amethystine bishop, and this extraordinarily kind captain, who both seem like real old friends, as do, indeed, all the people on board, from the officers and quartermasters, down to Antoine, the Italian maître d’hôtel, who takes me under his especial charge, and 4is as careful as any old nurse? I know that if I were sick he would insist on coming to the rescue, but as yet he has not had the smallest chance of showing me such attentions; for though we had one really rough day, the ship is so very large and steady, that you scarcely perceive any motion. You did not half see her; she really is a noble vessel, and all her machinery is so beautifully kept—such a display of polished brass and steel—brighter than on most English men-of-war. Of course I have been duly lionised over every corner of her, and I think the most novel sight of all, is serving out rations, and seeing wine pumped up from huge vats, to fill the small barrels, each of which represents eight men’s daily allowance. What immense supplies must be laid in when such a ship starts on a long cruise! They are sufficiently startling on board such vessels as the Messageries Maritimes, where every soul on board drinks vin ordinaire at every meal, and where there is daily consumption of about two hundred bottles, and the store laid in at Marseilles has to suffice for the voyage to Yokohama, and back to Marseilles.

The little cabin assigned to me is charming—so full of natty contrivances to make the most of space, and all so pretty. I believe that several of our kind friends on board have contributed to make it so. One lent a beautifully carved mirror, another a pin-cushion of pale-blue silk and lace. Fixed to the wall are fascinating flower-vases of black Chilian pottery, brought from Lima, and most delicate little kava bowls from the Wallis Isles, now utilised to hold soap, sponge, and matches. I find a whole chest of drawers empty, and various shelves, which I know can only have been cleared at great inconvenience. A small bookcase contains a very nice selection of French and English books—for my especial host, M. de Gironde, has travelled a good deal in England and in Scotland, and reads English well, as do several of the others. Having so generously given me his cabin, he has taken up his abode in the chart-room on the bridge, and declares he likes it far better; that it is much cooler, and that he never was so comfortable, &c. In short (in common with all the others), he tries to make me really feel as if I were conferring a huge obligation 5on the whole party by having come. Never were there such hospitable people. I have had a good deal of spoiling in the course of my life, but I never had it in such perfection as now. Every creature on board is so cordial, that it would be quite impossible not to feel so in return. I think my French is improving! I can now distinguish the Brétons from the Provençals, and both from the Parisians.

The officers are a pleasant, well-informed set, who have travelled with their eyes open, and their relations with their fine old captain are those of cordial sons with a father. It would be difficult for any one accustomed to the rigid stiffness of the British navy to understand such a condition. Even the frank kindliness with which sub-officers and men are addressed, sounds to me as unusual as it is pleasant. Life on this ship seems that of a happy family, with the filial and paternal affections unusually well developed, and M. Aube is generally the centre of a cheery group, chatting unreservedly on whatever topic may arise.

At least two of the officers are daily invited to breakfast, and two others to dinner in the captain’s little cabin, all coming in their turn. And six or eight generally come in to evening tea, a ceremony which, I suspect, has been instituted specially out of deference to my supposed English habits. Besides the bishop and myself, M. Pinart is also the captain’s guest, and I find him pleasant and very ready to impart his information, which, as you know, is considerable, on all scientific matters. The others have little jokes at his expense, and declare that he is more of a Yankee than a Frenchman. I can only say the combination is good.

The feeding is excellent, beginning with early chocolate. Breakfast is at 9 o’clock, and ends with coffee and liqueurs, especially most delicious Chartreuse, which some of us in an irreverent whisper call “La meilleure œuvre des moines.” Dinner, with similar ending, is at 5 o’clock, and tea at 8. Antoine has orders to give me luncheon at 1, with due respect to English habits; but I find this quite superfluous; so that ceremony falls through. By the by, tell A. that his champagne-cup produced quite a sensation. It was generally set down as being de l’hydromel, and the greatest 6curiosity prevails concerning its ingredients, which I, unfortunately, am not able to satisfy.

We are now about 250 miles east of Fiji, and sighted land this afternoon; we have just anchored off Tonga, which certainly compares unfavourably with our beautiful Fijian isles. This is the dullest, flattest land I have yet seen—a low shore, fringed with long lines of cocoa-palm, which, seen from the sea, are singularly monotonous. The king’s town, Nukualofa, consists of a long row of more or less ugly villas, stores, and barracks, built of wood and painted white: one is bright-green. The houses are roofed with zinc or shingle, and the general effect is that of a new English watering-place. King George’s palace is a rather handsome wooden building like a hotel, and is reserved for his guests. The Government offices occupy another wooden building, and just beyond them is the printing-office, in which a few books, a magazine, and an almanac, are printed in the native tongue. A large Wesleyan church, painted white, and with a very small steeple, stands on a green hill on the site of an old fortification, and close to it is the house of Mr Baker, Wesleyan missionary.

About a mile and a half along the shore is another village called Maofanga, where there is another Wesleyan church, but it is chiefly a Roman Catholic settlement; and near a neat thatched chapel of the true Tongan type, I see a long pleasant-looking bungalow, which I am told is a convent, the home of a society of French Sisters. To-morrow morning I hope to go ashore and see everything.

You see my experiences are rapidly enlarging. I have to-day made my very first acquaintance with conventual life, and am greatly interested by it, and by the exceedingly ladylike kind women who, at a hint from the bishop, invited me to stay with them as long as the ship is in harbour, and have given me this clean, tidy wee room, which, though not luxurious, is some degrees 7more so than their own simple cells. I have a table, a chair, and a tiny bedstead.

There are only four Sisters. The eldest, Sister Anna, is a very old lady, but most courteous and friendly. Sœur Marie des Anges is a cosy middle-aged woman, who has lately come from the convent at Samoa to take care of Sœur Marie des Cinq Plaies, a sweet, pretty young woman, with a terrible cough, and evidently fast dying of consumption. The fourth sister, Sœur Marie-Jésu, is Irish. All are most gentle and kind, and seem deeply interested in their schools and the care of a large number of nice-looking women and children. I think myself most fortunate in having been invited to stay here, instead of finding quarters in the ugly, pretentious town of foreign houses, which, whatever advantages they may possess, are quite opposed to all our predilections in favour of native architecture.

The surroundings here are calm and quiet. Through a frame of tall palms, with ever-waving fronds, we look to the blue harbour, where the friendly big ship lies mirrored—a ship which, to these good Sisters, is a link to that dear home-land, la belle France, which they do so love, but to which they have bidden a long farewell, in devotion to their mission work in these far isles. The schoolroom is under the same roof, and full of bright intelligent girls. At sunset there were vespers in the church close by, and, as the delicate sister was ordered to stay at home, and do her part by ringing the Angelus, we sat together and listened to the singing, which was very good,—the Tongan rendering of Canticles and harmonised Litanies being excellent. The harmonium is played by Père Lamaze, who is a good musician. Another father, a fine old Bréton priest, is the architect of a handsome wooden church now in process of erection. (When the Seignelay touched at the Wallis Isles on their way to Fiji, the bishop consecrated a really very fine new church there; and as the Roman Catholic Mission in those isles is very strong, there seem to have been wonderful rejoicings on the occasion. Among the offerings of the people were 150 pigs, which are being gradually consumed by the crew.)

This morning, soon after breakfast, Captain Aube landed me, 8in charge of M. Berryer and M. Pinart, to explore the hideous town. The shore-reef is so wide that at low tide there is a broad expanse of slimy mud and sharp coral; so it was with some difficulty that we effected a landing, just below the king’s house, whence floated the flag of Tonga, which is red, with a white cross on one corner. King George has a guard of two hundred men, some of whom are arrayed in scarlet, and a detachment of these were on duty, expecting a formal visit from the captain and the bishop,—which, however, did not come off till the afternoon, when there was much saluting—twenty-one guns fired from the ship, and twenty-one returned.

We naturally made for the highest point of this very flat town—namely, the Wesleyan church, which, though it only stands about fifty feet above the sea, commands a good bird’s-eye view of its surroundings—thatched roofs just seen through luxuriant bread-fruit trees, cocoa-palms, and large-leaved bananas, with scarlet hybiscus and rosy oleanders to give an occasional touch of colour.

Close to the church is the grave of the commander of an English man-of-war, who, forty years ago, allowed his valour to overcome his discretion, and himself led an armed force to assist the present King George in asserting his claim to the throne. In charging a stockade he and several of his men were killed, and an English gun was captured, which still lies at the village of Bea, about four miles from here.

Another very sad memory clings to this place—namely, that of the barbarous massacre in the year 1799 of three of the very first missionaries who ever landed in the South Pacific. A party of ten men were sent to Tonga in 1796 by the London Mission, and for three years they contrived to hold their ground, till, on the breaking out of a civil war, three of their number were murdered, and the others were compelled to fly, and conceal themselves as best they could. On this occasion, as on almost every other when the lives of Christian teachers have been sacrificed, the action of the savages was distinctly due to the influence of wicked white men. The culprit at Tonga was an escaped English convict, who, having won the ear of the king, persuaded him that these men 9were wizards, and that an epidemic, which was then raging, was due to their malignant sorceries. So, at the bidding of this scoundrel, the poor savages murdered their true friends.

That any should have escaped was due to the most providential and unlooked-for arrival of a ship captured in the Spanish war and brought to Tahiti—whence a member of that mission undertook to navigate her to New South Wales, on condition she might call at Tongatabu, to see how it fared with his brethren in the Friendly Isles. Thus happily were the survivors rescued, and the mission abandoned, till the Wesleyans ventured to reoccupy the dangerous ground, with what success we well know, seeing that to the aid given by their Tongan converts was due much of their wonderful progress in Fiji. On the green hill of Nukualofa are the graves of those early martyrs, shadowed by dark, mournful casuarina trees.

Leaving the church, on the little grassy hill, we descended to the dead level, and passed long rows of thatched houses embowered in flowering shrubs, with banana and pine-apple gardens. These are the homes of the mission students and their families,—all very tidy, and with well-kept grass paths and green lawn all round.

All the native houses here are oval in form, having both ends rounded. They have the same deep thatch as the Fijian houses, generally of reeds or wild sugar-cane. The walls are of plaited cocoa-palm leaves or reeds interlaced. The houses have no stone foundation to raise them above the damp earth, and in many of the poorer huts the floors are merely strewn with dried grass instead of having neat mats, such as the poorest Fijian would possess. Only in the wealthier houses did we see coarse mats, made of pandanus. In the majority, however, there is an inner room screened off to form a separate sleeping corner; and we noticed that the Tongan pillow closely resembles that of Fiji, being merely a bit of bamboo supported by two legs. The cooking is generally done in a hut by itself, built over an oven in the ground; but a good many ovens are al fresco, and the daily yams, or the pig of high festivals, are baked quite in public.

10Mr Baker,[1] who is the head of the mission here, was absent, but we called on his wife, who received us kindly, and made me a present of a pretty Tongan basket and combs. She regretted that she could not offer to take me for a drive, her carriage having come to grief. There are all manner of vehicles here—wonderful in our eyes after having so long looked with reverence on the engineer’s wheel-barrow as the only wheeled conveyance in Fiji! There are also a number of horses, descendants of those left here by Captain Cook, A.D. 1777, which the Tongans ride at a hard gallop, with a tether rope round their necks in lieu of a bridle. Finding that Nukualofa was utterly lacking in picturesque incident (at least so it appeared to eyes satiated with Fijian beauty of scenery), we followed a broad grass path which runs along the shore and intersects the isle. Like everything else here, it is in apple-pie order. King George is too wise to waste the labour of his subjects, albeit convicts; so instead of useless stone-drill or treadmill, all Tongan criminals labour for the good of their brethren, eminently to the improvement of the isle. How often, in India and Ceylon, when unable to close my ears to the monotonous word of command of some police sergeant, “Take up—put down,” “Take up—put down,” I have watched the cruel waste of human strength expended on lifting a heavy stone, carrying it so many paces, and putting it down—and then doing the same thing again, and again, and again, in the stifling heat of a tropical sun! Would that our prison disciplinarians might borrow a hint of wisdom from this once savage Tongan king!

Following the pleasant path, beneath the shadow of greenest bananas, with the sunlight streaming in mellow gold through the tall palms far overhead, we reached the village of Maofanga, where we found the bishop at the house of the Fathers.

Père Lamaze then brought me here to the good Sisters, who received me with open arms. The delicate one immediately slipped 11out to do a little preliminary milking, that she might give me a cup of delicious fresh milk, and with it she brought me some lovely blossoms from the little garden in which the Sisters cultivate tall French lilies and a few other flowers to mingle with the abundant pink oleanders, in their church decorations.

After vespers, the day’s work being done, they came to my cell, and we all sat down on the mats and had a pleasant little gossip. I think that a breath from the outside wicked world cannot quite have lost all charm, and two at least of these ladies have evidently lived in good French society. Now they have gone to their cells, and there is not a sound in the quiet night. My door opens on to a verandah leading into the garden, and just beyond lies a peaceful burial-ground—neatly kept graves of Christian Tongans, some marked with simple crosses, and overgrown with flowers.

Now I must say good-night, as to-morrow will be a long day.

On Sunday morning I was awakened before dawn by hearing the Sisters astir. They were lighting their own tiny chapel, where, at sunrise, they had an early celebration, in order that they might not be obliged to remain fasting till the later service.

At 7.30 they brought me café au lait in my cell, and at 8 we went together to high Mass in the large native church. Of course there was a very full congregation, as, the better to impress the native mind, all the French sailors were paraded, to say nothing of all the officers, who, dressed in full uniform, were ranged in a semicircle inside the altar-rails, on show—a very trying position, especially to the excellent captain, who, though a thoroughly good man, would scarcely be selected as a very rigid Catholic. Indeed I cannot think that devotion to the Church is a marked characteristic of this mission-ship.

Accustomed only to see the good bishop in his ordinary garb of rusty black and faded purple, it was startling to see him assume the gorgeous Episcopal vestments of gold brocade with scarlet linings—the mitre, which was put off and on so frequently at different parts of the service, and all the other ecclesiastical symbols. The 12friendly priests, too, were hard to recognise in their richly brocaded vestments; and I confess that to my irreverent eyes the predominance of yellow and scarlet, and a good many other things besides, forcibly recalled the last gorgeous ritualistic services I had witnessed in many Buddhist temples in Ceylon, and on the borders of Thibet. Such impressions tend to wandering thoughts, and mine, I fear, are apt to become rather “mixed.” Anyhow it was a relief when the scarlet and gold vestments were replaced by purple, with beautiful white lace. All the accessories were excellent. A native played the harmonium well, and Tongan enfants de chœur chanted the service admirably. Altogether the scenic effect was striking.

Chairs had been provided for all the foreigners present, and of course I sat with the Sisters, though it would have seemed more natural to curl up on a mat beside the native women, as we do in Fiji. These Catholic Tongans so far retain their former customs, that they continue to sit on the ground, although the polished wooden floor, which has replaced the soft grass and mats of old days, is not exactly a luxurious seat.

In the Wesleyan churches, which are here built as much as possible on ugly foreign models, regular benches are the rule. I trust it will be long ere our simple and suitable churches in Fiji are replaced by buildings of that sort. I grieve to say that this is by no means the only point in which the natives here have departed from primitive custom. Not content with the noble work of utterly exterminating idolatry and cannibalism, the teachers in these isles are afflicted with an unwholesome belief in foreign garments, and by every means in their power encourage the adoption of European cloth and unbecoming dresses; consequently many of the Tongan men glory in full suits of black, while some of the girls appear in gaudy and vulgar hats, trimmed with artificial flowers. Imagine these surmounting a halo of spiral curls!

Is it not strange that this admirable mission, which has done such magnificent work in these isles, cannot be content to allow its Tongan converts the same liberty in outer matters as its wise representatives in Fiji allow their congregations? Here the “gold ring and goodly apparel” are promoted to the foremost stiff benches. 13There the distracting “care for raiment” is reduced to a minimum, and all the people kneel together devoutly, on the soft accustomed mats, in houses of the same type as their cool pleasant homes, without a thought that a building of a European type, with hard uncomfortable seats, and unbecoming foreign clothes, can render their prayer and praise more acceptable to their Father in heaven.

Nothing astonishes me more, in reading any of the early missionary records of grand work done in these seas, than the frequent laudatory allusions to the general adoption by the converts of some fearful and wonderful head-dress, in imitation of the hideous bonnets of our grandmothers, and worn by the wives of the early missionaries. Immense praise was bestowed on the ingenious females who, under the direction of those excellent women, succeeded in manufacturing coal-scuttle bonnets of cocoa-palm leaves. Still more startling was the same monstrous form, when cunningly joined pieces of thin tortoise-shell were the materials used to imitate the brown silk bonnet of England! We may well rejoice that these horrors are no longer an integral feature of Christianity in the South Seas! It is sufficiently dreadful to see the ultra “respectable” classes donning coats, waistcoats, and trousers.

Immediately after service I returned to luncheon on board, to be ready to start with Monseigneur Elloi for Mua, which is the principal Roman Catholic station here, distant about twelve miles. A large man-of-war boat with twelve rowers carried the bishop’s party, which consisted of two Fathers, and four of the ship’s officers. Several others got horses and rode across the isle. A party of Tongan students filled another boat. Wind, tide, and current being against us, the journey took three hours. It is a dreary coast, everywhere bound by a wide expanse of villanous shore-reef, which makes landing simply impossible. The approach to Mua is by a channel which seemed to me several miles long, and is like a river cut through the reef, which edges it on either side. Here we rowed against a sweeping current, and the men had hard work to make way.

On reaching Mua we found the riders awaiting us, and a great procession of priests, headed by Père Chevron, a fine grey-haired 14old man, who has been toiling here for thirty-five years. Scarlet and white-robed acolytes and others, carried really handsome flags and banners. Their chanting was excellent. They escorted the bishop to the beautiful Tongan church, which is a building of purely native type, with heavy thatch, and all the posts, beams, and other timbers are fastened together without the use of a single nail. All are tied with strong vines from the forests, and plaited over with sennit—i.e., string of divers fibres,—of hybiscus, cocoa-palm, pandanus, and other plants, ranging in colour through all shades of yellow, brown, and black. These are laid on in beautiful and most intricate patterns, and form a very effective and essentially Polynesian style of decoration. The altar, which is entirely of native manufacture, is really very fine. It is made of various island woods, inlaid with whales’-tooth ivory and mother-of-pearl. All the decorations in this church are in excellent taste, and bespeak most loving care. Here, as at Maofanga, comfort is sacrificed to appearance by the substitution of a polished wooden floor for the accustomed mats. I cannot say I think this an improvement, as it is a hard seat during a long service.

However, on this occasion I did not experience its discomfort, for, shocking to say, in view of the example to the natives, none of us attended the service, but all went off at once, guided by M. Pinart (whose antiquarian instincts had already led him thither), to the tombs of the Toui Tongas, the old kings of Tonga. They are formed of gigantic blocks of volcanic rock, said to have been brought to these flat isles from the Wallis group. They are laid in three courses of straight lines, like cyclopean walls, and lie at intervals through the bush. They are much overgrown with tangled vegetation, especially with the widespreading roots of many banyan trees, and though wonderful, are not sketchable.

In olden days, when the Toui-Tonga was here laid to his rest, his favourite wife and most valued possessions were buried with him. All his subjects, young and old, male and female, shaved their heads and mourned for four months. Those engaged in preparing his sacred body for the grave were obliged to live apart for ten months, as being tabu or sacred.

15When the corpse had been deposited on this great burial-mound, all the men, women, and children assembled, and sat round in a great circle, bearing large torches made of dried palm-leaves. Six of the principal men then walked several times round and round the place of burial, in sunwise procession, waving the blazing torches on high; finally, these were extinguished and laid on the ground. Then all the people arose and made the sunwise circuit of the royal tombs, as has been done from the earliest days, by men of all nations and colours,[2] and then they, too, extinguished the emblematic torches, and laid them on the earth, in memory of him whose flame of life had passed away for ever from the poor dead clay. This ceremony was repeated on fourteen successive nights.

The mystery in all antiquities of this sort lies in the problem, how a race possessed only of stone adzes could possibly have hewn these huge blocks in the first instance, and how they then transported them on their frail canoes across wide distances of open sea. Tombs of the same character were common to all these groups, and were called marais. They combined the purpose of mausoleums of the chiefs, and of temples where human and other sacrifices were offered.

Some of them were of gigantic dimensions. Captain Cook described one at Papara in Tahiti, which consisted of an immense pyramid, 267 feet long by 87 wide, standing on a pavement measuring 360 feet by 354. On its summit stood a wooden image of a bird, and a fish carved in stone, representing the creatures especially reverenced by that tribe.

The pyramid was, in fact, a huge cairn of round pebbles, “which, from the regularity of their figure, seem to have been wrought.” It was faced with great blocks of white coral, neatly squared and polished, and laid in regular courses, forming eleven great steps, each of which was 4 feet high, so that the height of the pile was 44 feet. Some of these stones were upwards of 3 feet in length and 2½ in width. The pavement on which the pyramid was 16built was of volcanic rock, also hewn into shape, some of the stones being even larger than the coral blocks, and all perfectly joined together, without mortar.

As Captain Cook found no trace of any quarry in the neighbourhood, he inferred that these blocks must have been carried from a considerable distance; and even the coral with which the pyramid was faced, lies at least three feet under the water. The question, therefore, which puzzled him, as it does us this day, was, how did these savages, ignorant of all mechanical appliances, and possessing no iron tools, contrive to hew these wonderful marais, which were the temples and tombs of every Polynesian group? The majority were pulled to pieces by the natives when they abandoned idolatry, but happily for the antiquarian, some of the tombs of the mighty dead escaped these over-zealous reformers; and though the coral altars are no longer polluted by human blood, the grey ruins still remain, now overgrown by forest-trees, and more solemn in their desolation than when those hideous rites were practised by the poor savages at the bidding of ruthless priests.

In the course of our walk we saw some lovely little pigeons, bright-green with purple head, and a number of larger ones, green and yellow. Also many small bats skimming about the cocoa-palms, darting to and fro in pursuit of the insects which make their home in the crown of the tree. Towards dusk a multitude of fruit-bats with soft fur appeared, flapping on heavy wing, and feeding on the flowers of various tall trees. We also noticed a number of tree swifts, reminding us forcibly of our own swallows: like them they skim airily about the houses, but instead of resting under the eaves, they seek a safer home in the tall palms.

Returning to the village, we lingered beneath the fine old trees known as Captain Cook’s, till summoned by the Fathers to supper at their house, which stands close to the church. They gave us the best they had,—namely, salt-junk and villanously cooked cabbage, whereat their naval guests secretly groaned, and bewailed the excellent cuisine they had left on board; but to these good ascetics such fare seemed too luxurious, so, although it was Sunday, and a 17great festival, they would taste nothing but a few slices of yam. I find them most interesting companions, having been so long in the isles, that they are familiar with all details of native manners and customs. The old Père Chevron is particularly pleasant. He has worked here for several years longer than our good old friend Père Bréhéret of Levuka, to whom he bade me send his loving greetings, which I hope you will deliver.

After supper with the Fathers, a kind Scotchwoman, Mrs Barnard, the only white woman in the place, came to take me to her house for the night, where she made me most comfortable, though I could not but fear that she and her husband had given me their own room. He is agent for a merchant’s house in the colonies. I found my hostess was a Cameron from Lochaber, who has retained her pure Gaelic tongue, and speaks both it and English with the sweet intonation ascribed to the Princess of Thule. Great was her delight when she learnt the real name of her guest, and many a pleasant reminiscence she had to tell of certain of my own nearest kindred.... We talked of mutual friends in the dear old north and on the west coast, and many a touching memory was reawakened for us both. Verily the ends of the world are bound by tender human links!

My hostess was herself astir long before dawn, to prepare breakfast for her countrywoman, as I was to make an early expedition with my French friends to Haamonga, distant about eight miles, to see a wonderful trilithon. The Fathers lent us their dogcart, but had no horse. However, they succeeded in borrowing one, which M. Pinart volunteered to drive. It proved a brisk trotter, and we sped along cheerily. Most of the others rode, escorted by two kanaques—a word which, though it simply means “a man,” is used by the French as a generic term for all manner of islanders in North and South Pacific.

It was a lovely morning and a delightful drive, over a good broad grass road—the bush on either side fragrant with jessamine, and the trees in many places matted with such tangles of large, brilliantly blue convolvulus as I have seen nowhere else but in the Himalayas. The lilac marine ipomæa abounds everywhere, and we 18passed dense masses of the large-leaved white sort. From these lovely hiding-places flashed green pigeons and blue kingfishers, startled by our approach. Tall sugar-cane, wild ginger with scarlet blossom, and blue clitoria, with here and there a clump of glossy bananas or quaint papawa, kept up the tropical character of the vegetation.

We had no difficulty in finding the great dolmen of which we were in search. It stands on a grassy lawn, surrounded by bush, and is certainly a remarkable object. It differs from all other trilithons I have seen or heard of, in that the two supporting pillars are cut out at the top to secure the transverse capstone, which is hewn.

The height above ground is 15 feet, length 18 feet, and the width 12 feet. Nothing whatever is known concerning its origin, and the natives have apparently no tradition concerning it.

This is the only rude stone monument I have seen in the Pacific, but I am told that others have been observed in different groups, though on a smaller scale; for instance, in the Society Isles, where the great altar of the principal marai on Huahine is a large slab of unhewn stone, resting on three boulders. Around it are the rock-terraces which formed the rude temple.

At Haamonga the cyclopean trilithon stands alone. All others known to us, such as those at Stonehenge, at Tripoli, Algeria, and in Central America, are found in connection with circles of huge stones, to which they have apparently been the gateway; but here there does not appear to have been any circle, not even a detached dolmen.

In its weird solitude it most resembles the cromlech of Byjnath in Bengal; but what may be its story none can possibly guess. One thing only is certain, that these grey stones were brought here by some long-forgotten race, who little dreamt, when they raised this ponderous monument, that a day would come when it should survive as the sole proof that they ever existed.

TRILITHON ON TONGATABU

FRIENDLY ISLES.

We have been told that within the memory of persons now living, an enormous kava bowl stood on the horizontal stone, and that most solemn and sacred drinking festivals were held here. It 19is very probable that this may have been the case, as the people would, in heathen days, very naturally retain some tradition of reverence for the trilithon, as the peasants of Brittany, and, I may say, of Britain, do for similar erections to the present day, assembling for annual festivals at “the stones,” though the origin of Carnac, Stonehenge, and Stennis, is as unknown as that of Haamonga.

Returning to the village we saw that the church was crowded, and that there were a number of candidates for confirmation. Judging that the service would occupy some time, and being anxious to see as much of the neighbourhood as possible, we drove along the coast to a particularly fine banyan, noted in Captain Cook’s chart, and beneath its shadow we rested awhile, and enjoyed a very pleasant half-hour overlooking a calm, beautiful sea.

We reached Mua just as the congregation was dispersing, and were troubled with some qualms on the score of our bad example, but the considerate bishop gave us full absolution. I regret to say that a considerable proportion of the people were like hideously-dressed-up apes, masculine and feminine—many of the former in seedy black clothes, and some of the latter attired in gay flimsy silk gowns, inflated with large crinolines, and with baby hats, trimmed with pink and blue flowers, stuck on the top of their fuzzy heads. Hitherto, as you know, my ideas of Tongans have been derived only from the stately men and women who have settled in Fiji, and there, like their neighbours, have retained the graceful drapery of native cloth. Here the influence of certain persons interested in trade is so strong, that the manufacture of tappa is discouraged by every possible means; and a heavy penalty attaches to making it on any, except one, day in the week. It seems that this law was passed in King George’s absence, and I am happy to learn that he was exceedingly angry—though, as yet, the law stands unrepealed, and the manufacture is doomed to cease altogether this year.

Whoever is to blame, the system of taxation and fines is something astounding. A woman who is found without a pinafore, even in her own house, is fined two dollars, no matter how ample 20is her petticoat. Should she venture beyond her threshold minus this garment, she is liable to a fine of three dollars. If caught smoking, she is fined two and a half dollars, and one and a half dollar costs. Imagine such legislation for a people whose highest proof of reverence in olden days was to strip themselves to the waist in presence of their king, or on approaching a sacred spot, and who still consider any upper garment as altogether superfluous—a people, moreover, whose very nature it is to be for ever rolling up minute cigarettes for themselves and their friends!

The most atrocious of all the regulations is one inflicting a fine of ten dollars on any man found without a shirt, though wearing such a sulu (kilt) as would in Fiji be considered full dress, either at church or Government House. One of the lads told us he had actually been made to pay this fine a few days ago, having put off his shirt while fishing. Wet or dry they must wear the unaccustomed foreign clothing, instead of the former coating of oil, which made these people as impervious to water as so many ducks. But whether by compulsion or for vainglory, the hideous foreign clothes are worn during the burning heat of the day; then, under the friendly veil of night, comfort and economy are consulted by dispensing with superfluous garments; and so the heavy night-dews act with double power, and chills produce violent coughs, which too often end in consumption and death.[3]

21These people, like most kindred races when brought in contact with civilisation, are fast dying out. I believe there are now only about 9000 in the Tongan group, 5000 on Happai, and 5000 in Vavau district. They certainly are a very fine well-built race, with clear yellowish-brown skin and Spanish colouring; they also resemble Spaniards or Italians in their animation of expression,—the muscles of the forehead working in a most remarkable manner, especially to express wonder or interest. They have fine faces, well-developed forehead, strong chin, and features generally like those of an average good-looking European. Not the slightest approach to the “blubber lips and monkey faces” of negro races, or of the isles lying nearer to the equator. On the contrary, the mouth is well formed, and shows beautiful teeth. The eyes are invariably dark brown, generally large and clear. The beard, moustaches, and eyebrows are allowed to retain their natural glossy black; but, as in Fiji, the hair is dyed of a light sienna by frequent washing in coral-lime, and encircles the head with a yellow halo, strangely in contrast with the dark eyes and eyebrows. Like that of the Papuan, rather than the pure Polynesian races, it takes the form of a mop of innumerable very fine spiral curls, of which each individual hair twists itself into a tight corkscrew. It is crisp and glossy, and very elastic; and if you draw it out full length, it at once springs back to its natural form. Some of the women now allow their hair to grow quite long. Both men and women march along with a proud overbearing gait that always gives one an impression that they look on all other races with something of contempt.

22Our morning’s work had given us such keen appetites that we did more than justice to the breakfast which awaited us at the Fathers’ house, though it must be confessed that the fare was of the coarsest; it was, however, the very best they had to offer, and was evidently considered quite a feast. My comrades congratulated one another that such viands did not often fall to their lot!

Immediately after breakfast we started on our return journey with a high tide. Wind and current being in our favour, we flew down the river-like passage through the wide coral-reef, which we had ascended with such toil, and less than two hours brought us back to the good ship, and to cordial greeting from her genial captain. He had invited King George of Tonga and his grandson to dine on board, to meet the bishop and the Fathers, and I was invited to join the party. The king, who ought properly to be called Tupou or Toubo, which is the surname of all the royal family, was received with a salute of twenty-one guns—the ship dressed and yards manned, with sailors shouting “Vive la République!” (an institution to which, I fancy, that most men on board are profoundly indifferent—in fact several are declared royalists, and faithful adherents of Henri V.)

The Tongans were duly conducted all over the ship, and examined machinery, guns, men’s quarters, and every detail, with apparent interest. A long dinner followed, from which I escaped as soon as I conveniently could.

The king is a very fine old man, in height about 6 feet 2 inches. He was dressed in a general’s full uniform, and his grandson in that of an aide-de-camp—cocked-hat, &c. I confess I think that Thakombau and Maafu, in their drapery of Fijian tappa, are far more imposing figures. The king’s son, Unga, is at present seriously ill. His three sons govern the three groups into which this island-kingdom of Tonga divides itself—namely, Tongatabu, Happai, and Vavau. There are only about sixty isles in all, and their area is about 600 square miles; so this is a small matter compared with the 7000 square miles of Fiji. I am told that here the land all belongs to the king, so that any one wishing to settle can only do so as a tenant, leasing land from his Majesty.

23The feast being over, le Roi kanaque departed amid blue and green lights, one of which was reserved for us—i.e., the ecclesiastical party—returning to the priest’s house and to the convent, where the pleasant Sisters awaited me with kindest welcome; and we all sat on the mats in my cell and chatted for a while.

Now I am so very cold that I must go to bed. I think this climate must be far more trying than that of Fiji. The heat in the daytime feels to me greater, and every night is bitterly cold, necessitating piles of rugs and blankets; while the dew is so drenching that the roofs always drip as if there had been heavy rain. I do not wonder at the delicate little Sœur Marie having fallen into consumption. It carries off many strong natives.

Wasn’t it just cold when I left off writing! I lay awake shivering for two hours, though wrapped up in blanket, cloak, and big tartan plaid. I find that the island of Tongatabu is known all over the group as the cold isle, and I am ready to endorse the title.

I devoted this forenoon to a sketch of this hospitable cottage-convent, and in the afternoon went alone to see Mrs Baker, who took me to visit the queen—a fine old lady, but very helpless, having dislocated her hip by a fall eight years ago. She was sitting on the bare boards in a wretched little room of a small house close to the large villa or palace in which King George receives his guests, but in which he never lives, preferring that his home should be faka-Tonga—i.e., adhering to native customs so far as is consistent with keeping up appearances. But here, again, we were struck by the uncomfortable substitution of a hard wooden floor for the soft mats of a truly native home. As civilised houses are glazed, the poor old queen, though much oppressed with heat, sat beside a glass window, shaded by a filthy tattered rag which had once been a curtain, but which in its palmiest days had been immeasurably inferior to a handsome drapery of native cloth: indeed the only symptom of comfort in the place was a curtain of Fijian tappa.

24The king and his chiefs were in council over church matters in a small room adjoining the queen’s, so we had to talk in whispers. Various female relations were grouped round the door, making the hot room still hotter. I am much struck by the fact that these proud Tongans make use of no titles. The Fijians always prefix the word Andi—i.e., Lady—to the name of a woman of rank; but here the name is used bluntly, whether in addressing a princess or her handmaid.

Hearing of the grave assembly of the chiefs to discuss the affairs of the Wesleyan Church, brought back vividly to my mind all that I had heard in former days of this very King George, and of the prominent part taken by him in rousing these islanders to abandon their gross heathenism and cannibalism. So effectual has been his work, that now not one trace of these old evils remains, and these islanders are looked upon as old-established Christians.

I had a pleasant walk back in the twilight, along the broad grass road which runs parallel with the sea, and am now spending my last evening in this peaceful convent. I am truly sorry that it is the last, for it will feel like leaving real friends to part from these kind Sisters, who make much of me, and do enjoy coming to sit with me in the evenings for a little quiet chat. They bring all my meals in here, as it is against their rules to allow me to feed with them in the refectory. In this respect they are far more rigorous than the Fathers, who, as you know, have invited me to supper and breakfast at their house.

Here I am once more safely ensconced in my favourite niche, which is the carriage of a big gun. Filled with red cushions, it makes a capital sofa, and is a cosy, quiet corner, and a capital 25point of observation, whence, without being in the way, I can look down on the various manœuvres on deck—parades, gun practice, fire-parade, and so forth. We embarked this morning early, the four Sisters, by special sanction of the bishop, coming to see the last of me, and to breakfast with M. Aube;—an outrageous piece of dissipation, they said, but almost like once again setting foot in France. Four of the priests likewise escorted the bishop, and we had an exceedingly cheerful ecclesiastical breakfast-party, after which came a sorrowful parting, and then we sailed away from Tonga, taking with us the Père Padel, a fine old Bréton Father.

We are now passing through the Happai group, and hope to-night to catch a glimpse of the volcano of Tofua, or, as it is also called by the natives, Coe afi a Devolo (the Devil’s fire). It is a perfect volcanic cone 2500 feet in height, densely wooded to the edge of the crater. Strange to say, though the isle simply consists of this one active volcano, there is said to be a lake on the summit of the mountain. It is not stated to be a geyser; but the Tongans who visit it bring back small black pebbles, which they strew on the graves of their dead.

The Happai group consists of about forty small isles, some purely volcanic, and others, as usual, combining coral on a volcanic foundation. About twenty of these are inhabited.

The volcano proved to be quiescent. Not even a curl of luminous smoke betrayed its character. The sea, however, made amends by the brilliancy of its phosphoric lights. It was a dead calm, and from beneath the surface shone a soft mellow glow, caused, I am told, by vast shoals of living creatures, as though the mermaids were holding revel beneath the waves, and had summoned all their luminous subjects to join in the dance. I know few things in nature more fascinating than this lovely fairy-like illumination. Its tremulous glow and occasional brilliant shooting flashes are to me always suggestive of our own northern lights—a sort of marine aurora.

26Our course this morning was very pretty, steaming for many miles through narrow and intricate passages between the richly wooded headlands of Vavau, the great island, and many outlying islets. Finally, we anchored in what seemed like a quiet landlocked lake, at the village of Neiafu.

The bishop went ashore at once, and was reverently welcomed by two priests, one of whom, Père Bréton, has been here for about thirty years, living a life so ascetic as to amaze even his brethren, so completely does mind appear to have triumphed over matter. We sinners all agree that having each been intrusted with the care of an excellent animal, we are only doing our duty by feeding and otherwise caring for it to the best of our ability. So the ascetic example is one which we reverence, but have no intention of following, cold water and yam, day after day, being truly uninviting. But the old man has not forgotten how to be genial and kind to others, and is a general favourite.

The Roman Catholic flock here is small, as is also the church, which, however, is very neat. The Wesleyan Mission flourishes here, as it does throughout these Friendly Isles. In the three groups—namely, Tonga, Happai, and Vavau, it has 125 chapels, with an average attendance of 19,000 persons, of whom 8000 are church members. Four white missionaries superintend the work of 13 native ministers, upwards of 100 schoolmasters, and above 150 local preachers. At the Tubou Theological College—so named in honour of King George Tubou—there are about 100 students preparing for work as teachers or pastors.

I landed with M. Pinart, and a half-caste Samoan woman, who could talk some English, acted as our interpreter with the widow of the late “governor,” a large comely woman, who invited us to her cool Tongan house, where friendly, pleasant-looking girls peeled delicious oranges faster than we could eat them. This whole village and district is one orange-grove; every house is embowered in large orange-trees—the earth is strewn with their fruit, the air fragrant. What an enchanting change after Tonga, where there are no orange-trees, and where a sense of stiffness and over-regulation seemed to pervade life!

27The present “governor” is a fine tall young chief, rejoicing in the name of Wellington. He is acting for his father, Unga, King George’s illegitimate son, whom he has declared heir to the throne, but who is at present in very bad health. The young chief seems inclined to hold the reins firmly and well. But at present the Vavau chiefs are in some disgrace with King George, as they are suspected of plotting against Unga, in favour of Maafu.[4]

Having eaten oranges to our hearts’ content, we continued our walk to the Wesleyan Mission, and on our way thither met the Rev. —— Fox on his way to the ship, to see if we had a doctor on board. The latter having already gone ashore, we returned together to the house—a quiet pleasant home, but for the present saddened by the serious illness of the young wife, who, a few weeks ago, gave birth to her first child. As Vavau can furnish neither nurse nor doctor, the wife of the missionary in Happai had, at great personal inconvenience, come thence in an open canoe to officiate on the occasion. She had, however, been compelled to return soon afterwards to her own nurslings, leaving the young mother and her baby in charge of native women. A very slow recovery, accompanied with some unfavourable symptoms, had produced such depression and alarm, that just before our arrival, the poor husband had actually been making arrangements for his wife’s return to Sydney for proper medical care. But, to get there, involved, in the first instance, a journey of about 200 miles in an open canoe to reach Tonga, whence she would have to proceed alone, in a wretched little sailing vessel, on a voyage of upwards of 2000 miles (as the crow flies)—a serious undertaking for a woman in robust health, but a terrible prospect for an invalid with a young baby.

Happily the timely arrival of the Seignelay dispelled this nightmare. M. Thoulon, the good kind doctor (himself père de famille), at once vetoed the rash arrangement, and his well-applied wisdom, and kind encouraging words, have already restored heart to the 28dispirited young wife; while a congenial talk with M. Pinart on the subject of Polynesian dialects and races, has helped to cheer the husband, who, later, took us to see his schools, pleasantly situated on a wooded hill, commanding a lovely view of the landlocked harbour. Then strolling back through the orange-groves, we returned on board, where I am now writing. The captain and several of the officers have gone off duck-shooting, and expect good sport.

Yesterday morning, after a very early breakfast, I went ashore at 6.30 with M. Pinart and Dr Thoulon. Mr Fox was waiting at the pier, and returned with us to the mission-house, where we found the patient already on the mend. I acted the part of interpreter for the doctor, who was happily able to supply, as well as prescribe, all needful remedies and tonics. So when we returned this afternoon to say good-bye, the young mother looked like a different creature—so bright and happy. Truly a blessed skill is that of the kindly leech!

The previous evening Mr Fox had undertaken to borrow some horses, and escort us to the summit of “The Pudding,” a wooded hill, commanding a splendid map-like view of the strangely intersected land and water on every side of us. The isles lie so close, one to the other, that we could scarcely believe we were looking on the ocean, and not rather on a network of clear calm lakes and rivers. All the isles appear to be densely wooded, but at intervals along the shore we could distinguish villages nestling among the trees. One small island has recently been ceded to the Germans as a coaling station, and there seems some reason for anxiety lest this small foothold should be taken further advantage of.

A CORAL CAVE. VAVAU.

Our ride in the early morning was exceedingly pleasant. I had insured my own comfort by bringing my side-saddle ashore. By some mistake we found that the stirrup had been left in Fiji; but happily, on such a ship as this, to want a thing is to have it, and I hear that a new stirrup and strap are to be ready for me ere we reach Samoa. On the summit of the hill we found breakfast all 29ready, a party of natives from the mission having made an early start with tea, yams, ham and eggs—all of which had been cooked gipsy-fashion. To this foundation we added the contents of a hamper, which the thoughtful captain had directed his maître d’hôtel to send with us. So we had a royal feast, and then I settled down to do a bird’s-eye sketch of the strange world outspread below, while gentle and rather pretty brown girls, with sienna hair, sat by, peeling oranges by the dozen, with which they fed us all incessantly.

It is the part of true hospitality to peel oranges for a guest, as their thick green skins contain so much essential oil, that the mere act of removing them makes the hands very oily and uncomfortable. Woe betide the rash and thirsty stranger who puts the green fruit to his lips to suck it, as he might a golden orange in Europe. For many hours the burning pain of almost blistered lips will remind him of his folly.

Returning to the village, we found a large ten-oared boat waiting for us, the captain having most kindly placed it at our disposal, to enable us to explore the coast. Mr Fox guided us to a truly exquisite cave, about five miles distant. Never before, in all my wanderings, had my eyes been gladdened by such an ideal fairy grot. We rowed along the face of beautiful crags, which we had passed on the previous day without a suspicion of the wonderful hiding-place within them. Suddenly we steered right into a narrow opening, and found ourselves in a great vaulted cavern like a grand cathedral—a coral cave, with huge white stalactites hanging in clusters from the roof, and forming a perfect gallery along one side, from which we could almost fancy that white-veiled nuns were looking down on us.

The great outer cave is paved with lapis-lazuli, at least with water of the purest ultra-marine, which was reflected in rippling shimmers of blue and green on the white marble roof. For the sun was lowering, and shone in glory through the western archway, lighting up the mysterious depths of a great inner cavern, which otherwise receives but one ray of light from a small opening far overhead, through which we saw blue sky and green leaves. 30No scene-painter could have devised so romantic a picture for any fairy pantomime. The French sailors were ecstatic in their delight. They collected piles of old cocoa-nut fibre and dry palm-leaves and kindled bright blazing fires, whose ruddy light glowed on the dark crevices, which even the setting sun could not reach, and blended with the blue and green reflected lights, and both played on the white coral walls, and the white boat, and white figures—(for of course, in the tropics, the sailors all wear their white suits). Soon these active lads contrived to reach the gallery, and glided behind the stalactite pillars, making the illusion of the nuns’ gallery still more perfect. Altogether it was a scene of dream-like loveliness.

All this coast is cavernous, and most tempting to explore. Very near my fairy cave lies the one described by Byron, in “The Island,” which can only be reached by diving—

A huge rock, about 60 feet high, rises from the sea, with nothing to indicate that it is hollow; but at a considerable depth beneath low-water mark, there is an opening in the rock through which expert divers can enter, and find themselves in a cave about 40 feet wide and 40 in height—the roof forming rude Gothic arches of very rich and varied colour, and the whole incrusted with stalactites. The clear green water forms the crystal pavement, but two lesser caves, branching off on either side, afford a dry resting-place to such as here seek a temporary refuge. The place is quite unique in its surpassing loveliness; and the brilliant phosphoric lights which gleam with every movement of the water, and which are reflected in pale tremulous rays, that seem to trickle from the stalactites and lose themselves among the high arches, give to the whole a weird ghostly effect, quite realising all one’s fancies of a spirit-world.

This home of the mermaids was first discovered by a young Tongan, who was diving in pursuit of a wounded turtle. Filled 31with wonder and delight, he lingered a few moments in admiration, then, recollecting how valuable such a hiding-place might prove in days of ceaseless intertribal war, he determined to keep his own counsel. So when he returned to the surface he held his peace, and all his companions were filled with wonder and admiration at the length of time he could remain under water.

Not very long after this, his family incurred the anger of the great chief of Vavau, and one and all were disgraced, and in continual danger of their lives. But the chief had a beautiful daughter, who loved this bold young islesman, and though under any circumstances he was of too lowly birth to dare to claim her openly in marriage, he persuaded her to forsake her father’s house and come to that which he had prepared for her in the romantic grotto.

Here she remained hidden for several months, only venturing to swim to the upper world in the starlight, and ever on the alert to dive to her hiding-place on the slightest alarm. Of course her simple bathing-dress of cocoa-nut oil and garlands did not suffer much from salt water; or if it did, trails of sea-weed quickly supplied fresh clothing. Her love brought constant supplies of fruit, to add to the fish which she herself provided: and so the happy weeks flew by, till at last the companions of the young man began to wonder why he left them so often, to go away all by himself, and especially they marvelled that he invariably returned with wet hair—(for the Tongans have the same aversion as the Fijians to wetting their hair, and rarely do so without good cause). So at length they tracked him, and saw that when his canoe reached the spot where he had stayed so long under water in pursuit of the turtle, he again plunged into the green depths, and there remained. They waited till he had returned to the land, suspecting no danger. Then they dived beside the great rock-mass, which seemed so solid, though it was but the crust of a huge bubble—and soon they too discovered the opening, through which they swam, and rising to the surface beheld the beautiful daughter of the chief, who had been mourned as one dead. So they carried her back to her indignant father—but what became of her hapless lover history does not 32record. Doubtless he was offered in sacrifice to the gods of Vavau.

We peered down through the crystal waters to see whether we could discern the entrance to the lover’s cave, but failed to do so. Except at very low tide, it is difficult for average swimmers to dive so low. We only heard of two Englishmen who had succeeded. One was the early traveller, Mariner, who was present at a kava-drinking party of the chiefs in this cool grot; the other was the captain of an English man-of-war, who, in passing through the low rock archway, injured his back so seriously, that the people of Vavau believed him to have died in consequence.[5] It appears that the passage into the cave bristles with sharp projecting points, and it is exceedingly difficult to avoid striking against them. A native having dived to the entrance then turns on his back, and uses his hands as buffers to keep himself off the rocky roof.

Our row back to Neiafu was most lovely—sea, isles, and sky, vegetation and cliffs, all glorified in the light of the setting sun. As we were returning to shore, to land Mr Fox, Captain Aube hailed us, and bade us invite him to dinner with him. I thought this very courteous, as of course, on such an essentially Roman Catholic mission as this, there is just a little natural feeling that it may not be discreet to show too much honour to the Protestant minister, who, however, met with a most cordial reception, and we had a very pleasant evening.

This morning I was invited to accompany a party who started at daybreak to shoot wild duck on a pretty lake at some distance; but as I had the option of returning to the grotto, I chose the latter. So the captain again lent me the ten-oared boat, and we made another pleasant party to the beautiful cave: but it lost much of its beauty by being seen in the cold shadow of early morning, instead of being illumined by the level rays of the evening sun. We repeated the palm-leaf bonfires, but felt that we were not exhibiting our discovery to the best advantage. However, I got a sketch, which has the one merit of being totally unlike anything else I ever attempted.

We returned too late for breakfast in the captain’s cabin, so had 33a cheery little party in the ward-room, then went ashore to say good-bye to our friends, and carry away last impressions of the fragrant orange-groves of Vavau. Then the bishop and the Fathers returned on board, and we sailed away from the Friendly Isles.

My dear Nell,—I have asked Lady Gordon to send you a long letter to her, which I hope to post at Apia, so that I need not repeat what I have already written. We are having a most delightful cruise, with everything in our favour, and the kindness of every one on board is not to be told.

To begin with, Monseigneur Elloi, Evêque de Tipara, is a host in himself, so genial and pleasant, and so devoted to his brown flock. He is terribly unhappy about all the fighting in Samoa; and I think the incessant wear and tear of mind and body he has undergone, in going from isle to isle, perpetually striving for peace, has greatly tended to break down his own health, for he is now very far from well, and every day that we touch land, and he has to officiate at a long church service, he is utterly exhausted. It is high time he returned to France, as he hopes to do, at the end of this cruise.

His title puzzled us much when he arrived in Fiji, as we supposed him to be Bishop of Samoa. But it seems that a Roman Catholic bishop cannot bear the title of a country supposed to be semi-heathen, so they adopt that of one of the ancient African churches, which are now virtually extinct.

To-day, being Sunday, the bishop called together as many of the 34sailors as wished to attend, and held “a conference”—which meant that he sat on deck, and they sat or stood all round, quite at their ease, no officers being present, while he gave them a very nice winning little talk, ending with a few words of prayer. There was no regular service. There is always a tiny form of morning and evening prayer, said on parade by one of the youngest sailors, which is very nice theoretically, but is practically nil. At the word of command, Prière, a young lad, rapidly repeats the Ave Maria and Nôtre Père qui êtes aux cieux; he gabbles it over at railroad speed in less than a minute; then, as an amen, comes the next thing, Punitions, followed by a list of the various little trespasses of the day, and the penalties awarded.

At each point where the vessel has touched, she has taken or left some of the French priests, many of whom have been working in these isles for so many years, that they know every detail concerning them, and are consequently very pleasant companions. One of my especial friends is a dear old Père Padel, a cheery Bréton, who has been working in the Wallis group for many years, with the happy result of seeing its savages converted to most devout Catholics. He is now going to Samoa.

Much of the charm of this voyage is due to the kindly, pleasant relations existing between the captain and all his officers, from the least to the greatest—all are so perfectly at ease, while so thoroughly respectful. They are all counting the hours for their return to la belle France, where several have left wife and family; and their two years’ absence apparently seems longer to them than the four years of our English ships would seem to be to less demonstrative Britons.

Nothing astonishes me more than the freedom of religious discussion on every side. Of course to the bishop and the numerous pères, personally, every one is most friendly and respectful, as well they may be; but as a matter of individual faith, c’est toute autre chose.