"If Miss Bee is willing I can drive her to the Towers."

Title: Beatrice of Old York

Author: E. A. Taylor

Illustrator: L. A. Govey

Release date: November 26, 2025 [eBook #77341]

Language: English

Original publication: Toronto: The Musson Book Company, Limited, 1929

Credits: Al Haines

"If Miss Bee is willing I can drive her to the Towers."

BY

E. A. TAYLOR

Illustrated by

L. A. GOVEY

TORONTO

THE MUSSON BOOK COMPANY, LIMITED

COPYRIGHT, CANADA, 1929

THE MUSSON BOOK COMPANY, LTD.

PUBLISHERS TORONTO

PRINTED IN CANADA

T. H. BEST PRINTING CO., LIMITED

TORONTO, ONT.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. How Bee Goode of Boston, came to England

II. The Man who Preached in Noah's Ark and Some of His Hearers

III. A Voyage to Canada in 1812

IV. How Ned came to York (Toronto)

V. How the Americans came to York, April 27, 1813

VI. How Ned Lost His Good Name and Vere His Soul

VII. How Ned Planned to Justify Bee's Faith in Him

VIII. How Ned Had Many Adventures, and Bee becomes a Woman

IX. How Ned Won the "Bubble Reputation", at the Cannon's Mouth

X. How Vere came to Newark, and Bee consented to be Betrothed to Him

XI. Kawque takes a Hand in the Game

XII. How Bee was Abducted—and the End

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

"If Miss Bee is willing I can drive her to the Towers." ... Frontispiece

"Miss Bee," exclaimed Ned, "are you hurt? What is the matter?"

"Dropped noiselessly overboard and swam ashore."

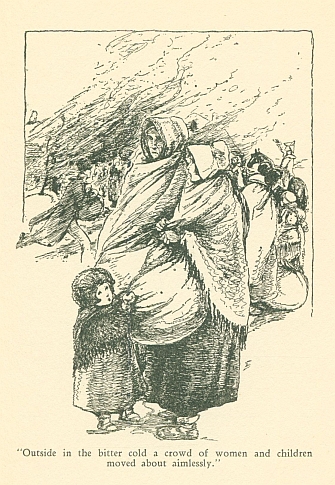

"Outside in the bitter cold a crowd of women and children moved about aimlessly."

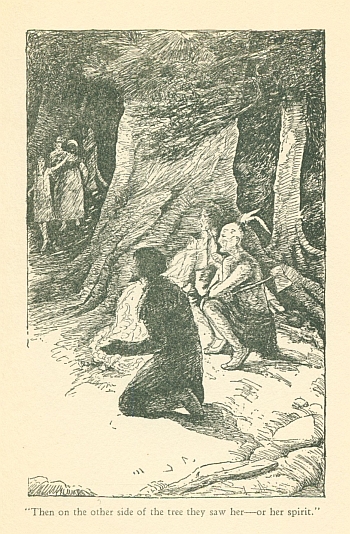

"Then on the other side of the tree they saw her—or her spirit."

BEATRICE OF OLD YORK

Beatrice of Old York

The stage coach from Plymouth to London had left two passengers at Liddon, a little manufacturing town in a dimple of the great chalk downs of Dorsetshire. Dobson, the coachman with the big carriage from Haslem Towers looked at them perplexed. His orders from his master, Colonel Sir John Haslem, were to meet the stage. Vere Haslem, Sir John's fifteen-year-old grandson and heir, had gone to Plymouth to meet his cousin, Beatrice Haslem, from York, in the mysterious far-off Canadas. But Vere was not to be seen, and there only alighted from the coach an enormous negress with a scarlet and orange turban and a small white girl whom Dobson did not notice for a minute. He was wondering in horror if this awful-looking savage could possibly be his master's granddaughter. He knew that Mary Haslem had made a runaway marriage with an unknown American twenty years before, and that her father had sworn never to forgive her. But she and her husband were dead, and he had consented that the Canadian guardians of her youngest child, Beatrice, should send her to him, and call her by her mother's name of Haslem.

Dobson had a vague idea that all Americans were Red Indians, and thinking that this black woman might be a variation of the race, he touched his cap in some trepidation, saying questioningly: "Miss Beatrice Haslem?"

"I am Miss Bee Goode, of Boston," said the child by the side of the woman, in a composed, distinct voice. Dobson looked at her; a slip of an eleven-year-old girl, pale-faced beside the rosy English children, and wearing the miniature woman's dress which was the fashion of the day—a green stuff gown, short-sleeved and cut low at the neck, with its waist-line under her arms, and a straight, narrow skirt. On her yellow curls she wore a very large straw bonnet trimmed with flowers, and tied under her chin with huge bows of ribbon. Long black lace mitts and a handbag of gay flowered chintz completed her costume.

"She's Haslem all right—furren too, though," thought Dobson embarrassed by her unchildlike, shrewd, gray eyes. Then he said aloud, "I was to meet Mr. Vere, and Miss Beatrice Haslem, Miss."

"I do not like my cousin Vere," said the child calmly, "and he stayed behind at Plymouth. Also my name is Goode, and unless you call me by it I will not go with you to see my grandfather."

Dobson looked helpless, and a boy came forward from among the interested spectators of the little scene. He looked about fifteen, with a sturdy figure, and honest, good-tempered face. He wore a tall black silk hat, and a man's suit of bright blue cloth, the coat with long flapping tails and a very high stiff collar. "Dobson," he said, "I have the pony here, and if Miss Bee is willing I can drive her to the Towers, while you take her maid and the baggage. And Dobson, you needn't mention Mr. Vere not being here." Then turning to Bee he added formally, "I am Ned Edgar, at your service, Miss Bee, I think you may have heard of me."

Ned had thought Bee very homely till he spoke to her; then he saw her eyes grow soft in an instant, and her cold little face flashed with smiles that made her fascinating, if not lovely. "Oh, I know your father," she exclaimed, "He is Mr. Edgar, fur-trader, of York in Upper Canada. I love him and Mrs. Edgar, your step-mother. I have lived with them since my mother died; and I was hoping to meet you when I came here."

So Ned drove Bee through the narrow streets of the town, pointing out the old house in its big garden, where he lived with Dr. Brown, his dead mother's father. "He is a Friend," said Ned, "but as the Friends have no meeting house here we go to the Methodist chapel—that's it there—we call it Noah's Ark."

"I know Mr. Edgar went to Canada when you were born and your mother died," said Bee. "But he never said you were a Methodist; he don't like them at all."

"I'm not a professor yet," Ned answered, then had some trouble to explain to Bee what it meant. The woollen workers of Liddon were almost all Methodists, while out of the town the gentry and their farmer tenants went to the Church of England, the two classes living entirely separate lives. Ned went to school with Vere Haslem, and a friendship had grown between the boys, partly because it was discouraged by the elders on both sides. To Sir John, Ned was a tradesman's son, brought up in the unspeakable religion of the Quakers, and a most unfit companion for a Haslem, all of whom were "soldiers and gentlemen". While in straight-laced Liddon to become a professor—to profess conversion—was the one aim in life. They took their religion very seriously; classes, preachings, and quarterly meetings were their only dissipations, and many heads were shaken over Ned's friendship with handsome, idle Vere, brought up to think a gentleman's business was war, his amusements heavy drinking and hunting, and his only religion a soldier's code of honour. And Liddon groaned over Sundays at the Towers, spent in cock-fighting, hunting or cards, winding up with the dinner, where often every man, including the parish rector, got drunk.

Ned wondered how bright, odd, Bee would get on with her autocratic grandfather; then asked how it happened Vere was not with her.

"I detest the creature," said Bee decidedly. "He laughed at my name, and went with some horrid boys to a cock-fight. And as it was time for the stage to start I came on with Mammy Chloe and left him."

"Vere generally wriggles out of his scrapes," said Ned, "and I expect he posted up after you, but Sir John will be very angry with him if he knows he didn't obey him and come with you."

"I don't tell tales," said Bee contemptuously; then she exclaimed in delighted wonder, for they had left the town, and driven through great gates into a wooded park.

It was Haslem Towers, Ned told her, and Bee forgot to keep up her air of American indifference to all things English as they drove up the long winding avenue of glorious oaks and elms. Large-eyed deer moved among the trees, and Bee exclaimed again as she saw a flash of water. They came out by a little lake where white swans sailed, and beyond it, flanked by pleasure gardens, rose a stately pile of white stone—the Towers.

"The three towers are two hundred feet high and the newest part of it is three hundred years old," said Ned. "I don't know when a Haslem didn't live here."

"Cousin Vere said he would have it all when grandfather dies," said Bee. "It's too good for him. Who will have it when he dies?"

"Oh, he'll grow up and have children most likely, but just now the next heir is Captain Percy Haslem. His wife, Mrs. Betty, is staying at the Towers, and he is visiting there, for his regiment is marching from Ireland across England, and is camping to-night in this neighbourhood."

They went through the great doors into a vast hall, where Bee was welcomed by Sir John, a militant looking old gentleman, sharp-tongued, rather thick-headed, and very soft-hearted where his own were concerned. With him was Betty Haslem, a very pretty young woman, with affectedly languid manners, and dressed in a high-waisted, narrow-skirted Empire gown of flowered muslin. Her fair hair was piled on the top of her head, and ringlets hung down on either side.

They were both prepared to be very kind to a nervous child, but Bee was not at all shy. She said she had let Ned bring her because she knew his father, and no one asked after Vere. Betty's afternoon "dish of tea" was brought in, with more solid refreshments, which Ned found he had to sit down to with Bee. He refused to touch the fruit pie which was pressed on him, then the sweet cakes too, while he felt himself growing furiously red under Betty's disdainful eyes.

"I protest, uncle," she said to Sir John, "I never knew a boy to refuse everything sweet before. What ails the creature?"

"He is a Methodist, Betty," said Sir John dryly, "and I believe that it's one of the articles of their faith not to eat sugar."

"A Methodist! I hear of them everywhere," exclaimed Betty. "But I shall die of curiosity if someone doesn't tell me at once why the creatures won't eat sweets."

"It is only sugar that Friends and many Methodists won't eat, Mrs. Haslem," said Ned flushing. "We are pledged not to taste sugar or rum till slavery is abolished in our West Indies. We use honey for sweetening."

"Then you can't make pastry or light cakes," said Betty; "honey would make them soggy."

"I have never tasted pie in my life, Mrs. Haslem," smiled Ned.

"You can when you go to your father in Canada," said Bee, "for there they get their sugar out of maple trees, and anyhow Canada abolished slavery in 1797."

Sir John asked Bee about her voyage, and she answered directly, "We had a very quick one, sir, only twenty-seven days. We left Quebec on July 14 and reached Plymouth on August 10. There were forty-two ships in our convoy, with the warship 'Primrose' to guard us from the wicked French."

Sir John chatted with her, so pleased with her intelligence and fearlessness, that when at last she boldly said that she must be called by her father's name, he only laughed. "She's too fine for rough handling," he thought.

"A little thoroughbred all through," he told Mrs. Betty later, "and a few years of proper English living will make her ashamed to own that she had such a scoundrel father. I'll wager that she's all Haslem, not a low drop of blood in her. Queer too, when her father was one of that crew of pirates and matricides who, with less morals than savages, fought us under Washington, and made most of our American colonies into an infernal Republic. Ay, and now in 1810, when we're fighting single-handed with that crowned hyena Bonaparte, all their sympathy is with those French assassins."

Meanwhile Betty talked to Ned, dropping her scorn and affection. The boy's simple manliness had won her respect, and when he left she shook hands with him, though Sir John raised his eyebrows. "It's no kindness, Betty, to give the lower class ideas above their station," he said. "Ned will do well unless he thinks he ought to be better than his birth made him, then he'll go wrong, mark my words. He's being educated too much as it is."

"La, uncle," yawned Betty, "it's easy to see you were born long before the French Revolution; since that upset nobody really believes in anything. I'm an atheist in politics as well as in religion."

"Don't, Betty, before the child. I'm thankful you are a lady-born."

"And so can't go wrong, eh? Well, I was taught that as long as a man's not a coward or liar, everything can be excused, and I really think Methodism is as excusable as some things I have been required to overlook in fine gentlemen. A boy who refuses sweets for conscience' sake, and won't give way even when a woman ridicules him can never be a coward or tell a lie. And if I were Vere's guardian, I should encourage his friendship with Ned Edgar."

Sir John frowned, but before he could retort, Vere, a very handsome boy, came in. He was followed by Percy Haslem in his captain's uniform, who, like Betty, his wife, spoke and moved with affected langour.

Sir John spoke irritatedly to Vere. "How is it, sir, that you left your cousin to be brought home by that doctor's boy?"

"Oh, Ned's all right, sir. He met the coach and claimed Bee because his father was her guardian in Canada, so I rode over to meet Cousin Percy."

"Insolence," growled Sir John. "To think he had such assurance, and I was blaming you for running off and letting him do it. Mark my words, it would be a kindness to give that boy a lesson that would break his proud spirit, otherwise he'll end on the gallows."

"Don't uncle, before the child!" mimicked Betty. "You'll frighten her."

"I'm not ever afraid of white men," said Bee calmly. "I'm only afraid of Red Indians when they have war paint on. I hate them; and I despise white men who tell lies."

"Haslem all through," chuckled Sir John, but Vere flushed angrily. He knew by instinct that Bee would not tell tales, but he hated her for her contempt of him, as he had never hated anyone before.

Sir John was talking to Percy who had just returned from unhappy south Ireland to whom England then was too busy to show justice, much less mercy. His regiment had been recruited there, and the country was in such dangerous ferment that all Irish soldiery had been withdrawn, and English sent there. Sir John denounced all Irish, "Traitors and papists!" he growled. "A heavy hand and the cat o' nine tails is the only way to keep them down."

"This regiment isn't all Papists, sir," put in Vere. "A little soldier spoke to me, saying he was a Methodist, and asking if there were any 'serious people' near. I told him that Liddon was the prize serious town in England, and that it had a Methodist chapel called Noah's Ark, because only those who go to it can be saved. I made him think I was 'serious', and he told me—Cousin Betty, you'll die of laughing when you hear—he, a private in the ranks, and Irish at that, preaches, yes preaches, in the streets, and in Methodist chapels when the regiment halts over Sunday near one. He'll be trying to speak in Noah's Ark to-morrow."

"Impossible," said Sir John angrily. "Percy, do you know what Vere means?"

"Very much what he says, sir. The man is George Ferguson, north Irish, born in Derry. He worked there in a muslin factory till a year ago, when the hard times caused by the war threw him out of work. There was nothing to do anywhere, he had a young wife, and finding she would be taken on the strength of the regiment if he enlisted, he did so, to save them both from starving. He is a strong Methodist, with a taste for preaching, and the regiment, who are nearly all Catholics, nick-named him the Swaddler Priest."

"The what?" exclaimed Betty.

"Swaddler, my dear. The first Methodist preacher who went to Ireland in the days of Mr. Wesley, preached his first sermon on the text, 'She brought forth her firstborn Son, and wrapped Him in swaddling clothes', and Irish Methodists are always called Swaddlers."

"And whenever did you become an authority on Methodism?" exclaimed Sir John.

"Ferguson has been my servant, sir, and while I am an infidel myself, I find him interesting. He can read and write, but he must have a hard life. He probably thought that entering the ranks would only mean the irksomeness of a discipline he had never been accustomed to, and the possible dangers of war. He didn't realize he would have to live in the closest companionship with men of, unfortunately, our lowest class, and their brutish tastes must hurt his self-respect. Yet I have never known him anything but serenely cheerful. He not only keeps himself above his surroundings, but he does it as if the effort were enjoyable, and tries to preach somewhere each Sunday."

"I should have thought it impossible for a north Irish Protestant to live in a south Irish regiment," commented Betty.

"I don't usually know much of what happens in barracks," said Percy, "but I was told—not by Ferguson—that when we were in Dublin he joined some Methodists who were preaching on the streets, and they gave out he would speak in their chapel the next Sunday. His comrades told him they would whip him if he did, but of course he went, and coming back, lay down on his cot and went to sleep quietly. No one disturbed him; the man who told me said they thought they might find themselves up against something bigger than they liked if they did. I think that men of our people, no matter if they are unsaintly themselves, respect a saint. Ferguson lives a strictly correct life, never touches drink, always does his duty, and is always cheerful and ready to do a kind act for a comrade."

"What does the fellow preach about?" growled Sir John.

"I heard him once speaking just outside the barracks to a crowd of soldiers and passers-by, and he spoke so strongly against swearing, that I refrain from profanity in his presence, fearing that he might think it his duty to reprove me if I did."

"What's England coming to," shouted Sir John, "when a private soldier is allowed to set himself up as a teacher? The end will be like when she let cobblers and tinkers usurp the place of ordained clergymen, and under that man whose name shall never be spoken in Haslem Towers while I live, dipped sacrilegious hands in the blood of her sainted king, Charles I. And when you allow a man to go as far as this Ferguson does, Percy Haslem, you are a traitor to your king."

"My dear uncle," said the unruffled Percy, "when Mr. Wesley began his work many thought as you do, but since then, the Supreme Being, or Fate, put a full stop to that period of the world's history by the French Revolution. Now no one is sure when our dear lower classes may not demand our heads; but we are quite sure that we would rather have a revolution of Bible readers than of atheists, so we let men like Ferguson alone."

* * *

So Bee spent her first evening at Haslem Towers, and on the Sunday morning went with the family to the beautiful old parish church, which only lacked a preacher and congregation to make it a perfect place of worship, for in the pulpit a curate dashed through the magnificent liturgy, and the congregation was a handful of farmers and the Towers' servants.

Bee sat in the great square pew trying to follow the service as she had learned to in York with Mrs. Edgar, while Betty lolled in a corner with a novel, and Vere was studying out a trick with a pack of cards. Sir John worshipped by doing nothing whatever, and only Percy, good-humouredly, thinking Bee might feel alone, looked at his prayer book when he remembered it.

In the afternoon Vere slipped off to the Methodist Sunday School, which he attended sometimes when his grandfather forgot to forbid it. He brought home the news that Ferguson had come to the school and been asked to speak, which he did so well, that it was announced he would preach that evening. "I was with Ned," said Vere, "when one of the elders asked Ferguson. Dr. Brown was there too; he looked odd in his drab coat and broad-brimmed hat by the soldier's scarlet. Ferguson seemed taken aback. He said, 'How do you know that I am not an impostor?' And the elder said directly, 'You would be the very first I ever met in the army; a hypocrite could never stand it there. He would be in torment indeed if he tried to wear a mask as a soldier among soldiers.' Then Dr. Brown asked him to have a dish of tea with them. Methodism is awfully upsetting. Think of even a Quaker, who is a doctor, asking a private soldier, the lowest class of all, to sit down with his wife!"

"Vere," said Betty, "you shall take me to this ridiculous Noah's Ark to-night. I am dying to hear this Ferguson creature. We will take Bee too, and Percy can come to keep us out of mischief."

Noah's Ark was a big, bare building, frigid in its lack of adornment or grace. Two things only made it fit for a place of worship—one who preached and those who listened. The woollen workers of Liddon with their drab-gowned, prim-bonneted women, filled the hard benches, women and young children on one side of the house, and men and boys on the other. Percy and Vere were seated with Ned and the doctor, with Betty and Bee just across the broad aisle. They were fashionably late, and the whole congregation were singing, without a touch of instrumental music to lead the hard strength of their voices—

"Let the house of the Lord be filled with glory, Hallilujah."

Three times they sang the line, their voices swelling in a harsh exaltation that was almost menacing.

"Let the preacher be filled with Thy love,

Hallilujah.

"Let the members be filled with Thy love,

Hallilujah".

Ten verses in all they sang, each consisting of the triple repeating of one line. Betty listened with the distaste of an educated music lover, yet she was oddly fascinated by the strength that showed in every note of the shouted hymn. These Methodists hurled their joy and confidence in God like a gauntlet of defiance at some unseen foe, and Percy's blood tingled. He recalled a morning on the hills of Spain, before the battle of Vimiero, when he had been with Wellington's army. There was the same intense sense of many men held together for one thing, and swayed absolutely by one man's words; but here, both the Commander and Enemy of these Methodists were of the other world, and according to Percy's arid philosophy, probably did not exist. He had fed his mind on Rousseau and Tom Paine, till he believed the miraculous and supernatural were scientifically impossible, and he felt irritated at the very tangible faith of these people in intangible possibilities.

The congregation were seated again, and George Ferguson in his regimentals, a splash of scarlet in that hall of grays and drabs, stood at the preacher's desk. He was a slightly built man, about twenty-four, and in no sense an orator, but he had a good voice and delivery, and believed so intensely in what he said that his simple words had a certain power.

He was telling his own story—"I was born August 1, 1786, in Derry, Ireland. My parents were respectable and in comfortable circumstances, but though members of the Church of England, had no knowledge of spiritual things. I was allowed to follow my own inclination and became very wicked and profane. The one exception to the godlessness round me was an aunt—a Methodist—who grieved at the way I was growing up, and would talk to me of my soul. So I became anxious, fearing to lie down to sleep lest I should wake in hell. I would lie awake groaning and sobbing, 'Oh, God, have mercy on me.' I went whenever I could with my aunt to class meetings and preachings, and at one I wept openly, saying when spoken to—'I am so wicked. I am not washed in the Blood, and I am afraid I shall be lost. May God have mercy on me.' The preacher and class prayed with me, and then he said, laying his hand on my head, 'George, you will yet go to preach the Gospel to sinners.' So I obtained grace, and resolved to turn from my sinful manner of life, being then seven."

The last words came as a shock to Percy, who wondered what kind of sinful life could be lived by a boy under seven in a respectable home. But the congregation saw nothing incongruous in it; they shouted "Amens" and "Hallilujah" as the speaker paused, then listened, many groaning aloud as he went on to tell of his "fall from grace". His parents moved from Derry into the country where there were no Methodists, and he drifted with other boys into attending cock-fights, and horse races on Sundays. At sixteen he was bound out for three years to learn his trade at a muslin factory. The hours there were long, and the work and confinement very hard to a boy accustomed to the indulgence of home. "I felt like Israel in Egypt in bondage under taskmasters," he said quaintly, "but in my dungeon I saw the Cloud, the Pillar, the Rock, the quails and the manna that I had rejected, and I hungered for them. I joined the Methodist Society as a probationer, I read the Bible daily on my knees, I retired for prayer seven times a day, I fasted entirely every Friday, and kept close watch over my words and conduct, hoping to find peace with God. The persecutions of my shopmates were hot and heavy, but I was convinced I must be singular, I felt it was life or death—death to live after the flesh. Mental distress and severe fasting reduced me to a skeleton, and my master kindly sent me home on a visit, but it was my soul that was suffering, I felt I had sinned beyond the mercy of God. I was tempted to give up. If God could not pardon me I had better know the worst of my case at once, by putting an end to my miserable life. I took a rope to an old warehouse one night, fixed it to a beam, and made a noose."

He paused dramatically, and his audience leaned forward with excited faces. All the colour and passion that raised their lives from grayness was in the unseen world. The excitement that outsiders sought in theatre and lurid novel, in war and gambling for high stakes, the early Methodist found in these soul-conflicts with the Enemy.

In a wonderfully soft voice Ferguson continued, "As clear as if spoken I heard the words, 'Pray first'. I instantly fell on my face, crying to God for Christ's sake to have mercy on me—on vile and wretched me. In a moment the rock was smitten, and I rested on Christ. I threw myself in the Blood of the Atonement crying—'Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity and cleanse me from my sin.' In a moment hope took the place of despair. I had peace with God. I loved God above all things. Christ was the altogether lovely."

Ferguson's voice had risen to a shout, he stamped his feet and clapped his hands in an ecstasy, as his words rang above the tumult of the congregation, who were now jumping up and down in their seats, weeping, singing, shouting "Hallilujah", clapping their hands, while some fell on the floor where they lay rigid as if in a trance. Betty half rose, then sat very still. Bee was rather too astonished to be able to think, and Percy was studying Ferguson's face. Its features showed the Scotch blood that is the backbone of Ulster, and a stainless life with much fasting and prayer, had given it an intense refinement. There was as little sign of mental as of moral weakness in it. Percy told himself the man was self-deluded; but in his heart he was not quite sure of it.

The congregation quieted enough to hear the preacher again, and Ferguson resumed, "I returned to work a new creature. I thought I was out of Babylon—that the Enemy had done with me; I expected this 'time of singing birds' to last the whole year. But the Enemy said to me, 'You are young, if you tell of this wonderful change people will not believe you. Keep it to yourself till you see if you can hold out. If you don't you may hurt the cause of God'. So—

'I was brought into thrall, I was stript of

my all,

I was banished from Jesu's face.'"

The audience intent on every phase of this soul-drama, groaned deeply as they swayed to and fro in their seats, and Ferguson lingered over the details of his next three months of mental agony. "But on June 11, 1805, I secured peace at last. Though I was in the shop I began at once to praise God aloud, and my shop mates said, 'The matter is decided at last, George is quite crazy.'"

Again the joyful tumult rose, and Percy felt irritated. He lived above the low moral standards of his day, and he thought it preposterous to preach that nothing saved a man but this converting. How could Ferguson with his intelligence believe that without salvation he was as low in the sight of God, as the vilest man on earth? Then he looked at the boys by him. Ferguson and the elders were shouting Bible promises above the "blessed disorder", and urging penitents to come forward. Ned, white-faced, and trembling with excitement, but with determination in his eyes, rose and held out his hand to Vere. Percy saw in his cousin's face a reflection of the whirl of feeling round him, and had a vision of himself breaking the news to Sir John that the heir of the Haslems had knelt at a Methodist penitent bench. Then he wondered if this mad religion might not give Vere the moral strength he knew he needed. On the spur of that thought, he whispered to the wavering boy, "Ferguson's a straight man, if you believe what he says, go forward."

But Ned went up alone. All that was good in Vere clung to Ned, and whatever sense of peace and strength he knew, he had met only in Dr. Brown's home, but he felt he could not face his grandfather's anger, nor give up in a moment his habits of idleness, and his drifting into doubtful pleasures rather than seeking them.

After the meeting the boys stood together, Ned quivering with the thought that he had pledged every fibre of his strong young body forever to the service of the Lord who had died for him. Vere said eagerly, "I feel as you do, Ned, but I can't go forward. If you were in my place—if my grandfather were yours, you would keep your religion to yourself for a little while."

And Ned, as was his habit, excused Vere and believed him. So the boys parted, Ned joining his grandfather who pressed five guineas into Ferguson's hand, as he bade him good-bye, saying, "If ever thee passes this way again, George, remember my house is also the home of all weary pilgrims on the road to Canaan, no matter what the colour of their coats may be."

The young soldier listened with bowed head, until he went off, and it was six months later that a messenger brought Dr. Brown and Ned a thick letter from Battle Barracks, Sussex, where Ferguson's regiment was quartered. Ned's letter was mainly advice to young Christians, mixed with bits of the writer's experiences. "In a crowded, noisy room," Ferguson wrote, "I have learnt the secret of lying on my cot so shut away in spirit from my surroundings, that I can hear the voices that speak to my soul as distinct as if I was in a solitude."

Ned was walking just outside the town as he read the letter, and then he met Vere, who exclaimed excitedly, "Glorious news, Ned! Sir John's going to get me a commission as soon as I'm sixteen—next month, and I'll be off to see life in his Majesty's service."

In spite of his up-bringing in a Quaker home Ned felt half-envious of his friend's future, and Vere went on impulsively. "What are you going to be, Ned? You don't want to spend your life taking pills to old women. Of course you couldn't expect your grandfather to help you to be a soldier, yet it's the only life for a gentleman. Why don't you write to your father and tell him you want to enter the army like me? That little cat, Bee, talks as if he was quite well off—almost a gentleman."

Ned did not answer, he really knew nothing of his father. Certainly very interesting and valuable presents came to him every year on his birthday, from far-off York, where Mr. Edgar lived with the second wife he had married and her three little boys; but he seemed to have given his eldest son entirely up to his grandfather.

So Vere went away, but Ned was far too loyal to his grandfather to ever think of appealing to an unknown father against him. Nevertheless, now that Vere's departure had broken off all his connection with Haslem Towers, he began to feel that life at Liddon was very dull. He saw Bee sometimes when she rode out with Betty; she was growing up into a tall girl, but she still smiled at him with a child's frank friendship. Betty decidedly refused to forbid this very slight intercourse, when Sir John grumbled at it, so he said no more, for Bee had grown very dear to him. He was content to give her her own way in calling herself by her father's name, but he was resolved that some day she should marry her cousin, Vere, and be mistress of Haslem Towers. Her refinement of spirit and high courage, he thought, might save the unhappy boy, who in the temptations of an idle garrison life was showing many signs of moral and mental weakness; Sir John refused to believe the worst. "Boys will be boys," he said impatiently to Betty. "Of course I'll pay his debts again, and ask no questions; if he sows all his wild oats now, he'll make all the better husband for our little maid later. She'll steady him fast enough, never fear—Bee Goode, as the minx insists on calling herself, not bad, eh! She shall be his wife on the day he is twenty-one, and she will be seventeen."

Betty felt a womanly reluctance to think of Bee thus sacrificed, yet she went on helping to train Bee in the ignorance of life that should make her unable to resist when those she loved and trusted pushed her skilfully into marriage. Betty, though a good woman, was warped by the artificial world in which she lived; she knew that Bee's parents had left her nothing; her brother, Eli, five years older, was with relatives in Boston, but Bee, when seven, had been adopted by the Edgars, who had given her up unwillingly to Sir John. Betty could not imagine any lot for a girl but marriage; and surely, she honestly believed, luxury in England, even with the lowest of husbands, was better than exile in some howling wilderness.

Bee had not forgotten her American brother, or her Canadian friends, but she never heard from either, and she believed Sir John when he blamed French privateers for the destruction of the Atlantic mail. She still wrote sometimes, but as none of her letters went overseas, her friends there naturally thought she had forgotten them in English luxury. Vere, who knew his grandfather's plan, hated Bee with all his mean little soul, but never dreamed of refusing to obey; and Bee, who had not the faintest idea that she was destined by her kin to be her cousin's wife, still despised him. Conditions of thought round her, however, were gradually bringing her to feel that it was the bounden duty of the relatives of the heir of Haslem Towers to make any sacrifice to save him.

In the big world outside Liddon much was happening. England, with her industries crippled, her commerce half-strangled, and seeing the carrying trade slipping into American hands, passed the unfortunate Orders-in-Council proclaiming any ship that did not touch an English port the lawful prey of her men-of-war. The answer of the United States was an immediate threat of war, should the order not be rescinded. England, fearing to lose Canada, whom she could not then defend—she did not imagine that Canada could defend herself—rescinded the orders, all of which did not prevent the States from declaring war on June 18, 1812.

The post that brought the news to Liddon also brought a letter for Ned from his father—"Upper Canada will be invaded before this reaches you," Edgar wrote. "We have a population of 70,000—both the Canadas have only 225,000, against the eight millions of the States, but we mean to keep the old flag flying. We have 1,500 miles of frontier to defend, and only 4,000 English regulars to help us do it. We have appointed our Governor, General Isaac Brock, as Commander, and are calling out every man between eighteen and forty-five. I am going, and I began this letter meaning to command you, as my son, to start for Canada at once, and add one more man to our little army. My friend, Surgeon Tam, at the Isle of Wight, would arrange for your passage out. You may refuse to obey me; I know you belong to a religion that teaches a man that he can enjoy the protection of the laws of a country, and grow rich there, but he must not fight in its battles. It is a 'sin' for him to go to war, but quite right to accept the safe living that other men are dying to defend. I cannot compel you to obey me, but, oh my son, won't you give up your religion and come to be my comrade? I have a wife, whom you would love if you knew her, and three little boys; won't you be near to give them a protection if I fall? No one can doubt the righteousness of our cause. I don't deny England has often sinned and blundered, but no land on earth has sinned and blundered so seldom as she, and her flag is the only one that shall ever wave over Canada—so help us, God! The American people have been excited by exaggerated stories of England's claiming the right to search their ships for deserters from her navy, but the President and Congress wish to take our country—our Canada. Will you come to be a soldier, to help me, your father?; or is your honour less to you than this Methodist salvation?"

Silently Ned laid the letter before his grandfather; the Quaker doctor read it, looked at the boy keenly, and said quietly—"Thee means to go, I see, but what of giving up thy faith?"

"Grandfather, I am a Methodist, not a Friend. I know some of our people think with you about war, but others are like Ferguson, whom you call a good man. I must go, to show my father that I can; I must keep my religion, yet fight bravely beside him. Don't you think I ought to go? Don't you think Canada is in the right?"

The Quaker looked at him wistfully. Ned was nineteen, and careful rearing, and the habits of self-discipline that his rigid faith taught him, had given both his body and mind the strength of tempered steel. Dr. Brown had planned he should be a healer of wounds and a saver of life, like himself, and now all this splendid young manhood must be offered to the Moloch of war. But he said—"In many ways I admire thy father, but he is over-hasty in judgment; yet I am free to think he does right in fighting in this war, and certainly thee must go as he says. I know thee will never forsake the rules of thy faith."

* * *

Ned, wandering off by himself to say good-bye to his old life, was amazed, in his loneliness, to find Bee. She also was alone; sitting on a stone, in tears.

"Miss Bee," exclaimed Ned, "Are you hurt? What is the matter?"

"Miss Bee," exclaimed Ned, "are you hurt? What is the

matter?"

She stood up; a tall slender girl in a purple serge riding habit and a plumed hat; not a beauty, but fast developing into a woman who would have the elusive flaire of charm. "I came out here by myself—ran away in fact," she said impulsively. "I could not bear servants or friends or anyone near me—I had to cry alone. You are a Friend; why isn't everybody like you? Why do they make these awful wars? Do you know that Sir John has got the War Office to take him off the retired list and he is going to Canada, and Vere with him? And we think Cousin Percy is going too, and he will take Betty and me. They are going to fight, and Eli, my brother, I know, will fight too, on the other side; it is the most miserable war that ever was."

"Perhaps your brother won't want to fight," said Ned trying to comfort her. "I should think many Americans would see they were in the wrong—."

"You know nothing about it," she interrupted with flashing eyes. "We only hear one side here, but I know there is another. Sir John and Cousin Betty would be so angry if I said such a thing at home, and I love them—and I love Eli too." Under her breath she added, "and I am an American."

She stopped, suddenly realizing her impulsiveness in confiding in a young man who was almost a stranger. "But he is one of those odd people," she thought, "who think women should preach, and rule, just like men; and that a man mustn't do anything that a woman shouldn't." So much Bee had heard, and she thought Ned's ideas must be foolish, and rather improper, but interesting. Ned said nothing, but caught her horse, which was grazing near.

"Thank you," she said, rather shyly as she mounted, "for listening to me. I feel better now."

She galloped off, and Ned looked after her—"What an odd girl," he thought. "But she is rather interesting."

The Isle of Wight with its white chalk cliffs, and the semi-tropical vegetation of its valleys, is a paradise among islands; though in August, 1812, when Ned landed there and was met by Ferguson, the babel of screams and howled curses he heard made him think of an inferno.

Ned had parted with his grandfather at Southampton, where the Surgeon, Dr. Tam, a bluff Scot, looked him over, and told him shortly that he was to go out, forward, on the troop ship "Lightfoot", with eight hundred men, which was all that England could spare to send Canada—and General Brock had said that ten thousand was the smallest number with which he could possibly defend the brave colony.

Ned was too delighted that Ferguson was one of the eight hundred to mind anything else, but he looked at his friend startled, as they came into the deep water harbor of Ryde, and heard the sound of women shrieking as if death itself had gripped them. Ferguson's face paled, "God pity them," he said. "Only a few women can go with the regiment to Canada. They have been chosen by lot—my wife by the good providence of God drawing a full number—and you can hear the ones who drew blanks."

They went on board H.M.S. "Lightfoot", a fine bit of the "wooden walls of old England." There, all seemed confusion. The Irish womens' screams were heart-rending as they were, as gently as possible, forced back on shore. Ned was glad to follow Ferguson below, first to the cramped "married quarters", where he was introduced to a neat, quiet little woman with a baby—Mrs. Ferguson. Opening off this smaller cabin was a wide space "between decks", where the men's hammocks were hung so close, that a man who left one when they were all slung would have to perform an acrobatic feat to get out, and dress on his knees on the floor under them.

As Ferguson showed Ned how to sling his hammock, and told him what he would have to do, rough voices round them called mockingly on the "Swaddler". Ferguson took no notice until big, brown-faced Dr. Tam, in his uniform, appeared beside him. He nodded curtly to Ned, and said gruffly to Ferguson—"Ye'll have to keep your Swaddling talk to yourself this trip, man. We are going to have some trouble with this crowd—they're Papists, too, and we can't have any religious fights. So you see you keep your mouth shut. Our new colonel hasn't any use for preaching soldiers."

Ned was too bewildered by the astounding unexpectedness of his new surroundings to be able to think clearly for the moment, but Dr. Tam shrugged his shoulders as he went aft to his quarters; Edgar was his friend, and Edgar had insisted that Ned should be sent out with the men of this regiment. "The best of them," growled Dr. Tam to himself, "are Irish rebels whom England doesn't dare to send to the Continent, for fear they might go over to the French. As to the worst of them, the regiments that threw them out weren't saints, but there are a few things that a man can't stand, and keep the least scrap of decency. And to think of that boy, who is as innocent as a girl, being compelled to live among them for a month! But it's his own father's doing, and I suppose it was the only thing to do."

Dr. Tam was a friend of Edgar's, and like him believed that a man whose religion condemned war must be a coward; and when he also held remarkable views on the equality of women, it showed he was effeminate. It was to cure Ned of his supposed weaknesses in one rough lesson, that he was reconciled to his making the voyage as he did.

Ned, who had the cheerful temper that goes with perfect health, decided that his new companions would probably improve when he got to know them better, and in any case he had a good comrade in Ferguson, so he stayed on deck, enjoying the novelty of everything.

By now everything was in perfect order. Screaming women and howling men had been put out of hearing and sight before the captain and the officers' ladies who were cabin passengers, came on board. Ned saw Chloe's broad black face, a good foil for the patrician loveliness of Betty beside her; Bee was with them, and Ned thought—"Vere's as ass to call her ugly, or even plain; she's not a beauty like Mrs. Haslem, but she's sparkling, and radiant. When she's grown up no one will call her plain."

Then Ned saw some one in whom he was more interested than in any girl—Vere, with whom he still corresponded, and whom he still liked; for all that was good in Vere showed itself when he wrote to or met Ned; he valued Ned's good opinion more than any one's, and if any influence could ever save Vere, from himself, it would be the quiet strength of young Ned Edgar.

Vere saw Ned at last, and went to him amazed—"What on earth are you doing here?" he exclaimed.

Ned explained, and though the sudden coldness with which Vere turned away hurt him a little, he was not surprised, nor much disappointed in his friend, for he understood that now less than ever, among his present companions, would Vere be able to meet him openly as a friend.

* * *

They were off now. At a word, sail after sail had unfurled, and beautiful under her enormous spread of white canvas, the "Lightfoot" "trod the waters like a thing of life." Ned was fascinated at this manifestation of drilled power. Every man on the ship had moved as a part of one great machine, and his imagination took fire. It seemed audacious that men should show such strength.

Ferguson seemed to have guessed his thoughts, for later when the shores of England were fading from view, he said—"Look ahead now, Ned."

Behind them the sun was shining, but before them the Atlantic rolled, a mighty heaving waste of gray waves, under a heavy sky piled with lowering storm clouds. A heaved-up ridge of water caught the "Lightfoot", she rose on its height, and slid down as it passed—a plaything of the sullen sea. Suddenly she seemed small to Ned, a winged insect fluttering in the grasp of the terrible ocean.

"The sea is His, He made it," cried Ferguson in mingled awe and exaltation, "I am afraid when I think of His infinite power, yet this awful God is mine—my Lord and my Lover," and his voice sank to a thrilling softness as he said the last word.

By night Ned had forgotten Ferguson and everything. With most of the unhappy soldiers he was horribly seasick, faintly wishing that some enemy might in charity sink the "Lightfoot" with all on board her. Even this, however, finally passed. He felt an interest in living once more and even in eating again. A few men, Ferguson among them, remained sick and stayed so all the voyage, crawling shakily about when the sea was very smooth, and collapsing at a hint of rough weather.

Every morning each man received his rations for the day, cooked meat—salt beef or pork—pease-pudding, some rice or porridge, sea biscuits, a little sugar and butter, a pint of hot cocoa, some rum, and three quarts of drinking water. The fare was coarse, but it was wholesome and abundant, and Ned enjoyed it.

Sells, a ruffianly looking man whose hammock hung next to his, swore at everything.

"Dog's food, that's what it is," he growled, "And do you know what they're eating aft? Every morning there's a dish of chocolate or coffee, with cakes and biscuits, and all the butter they like. Then biscuit and cheese at noon, and a high class dinner at night with fresh fowls and meat—they've live sheep, and pigs, and chickens on board for themselves—and potatoes, and pickles, and plum-pudding, with porter and wine. Then they have a supper of coffee and cake, and preserves, and more wine. Curses on all rich, I say."

He closed with a stream of profanity which brought Ferguson, pale and shaken, to his feet with a stern—"Thou shalt not take the Name of the Lord thy God in vain."

With an ugly oath Sells knocked him down, and Ned sprang to his assistance, for mal-de-mer had left Ferguson too weak to defend himself, and Sells was beating him savagely. The crowding men round them, cursing all "Swaddling interferers", struck at the two Methodists, yelling the war cries of persecuted, bitter, Papist Ireland. Ferguson and Ned were only saved from serious injury by the prompt interference of the sergeants, who, however, told Ferguson that the next time he "preached" and caused a riot they would report him.

His bruises, and anxiety as to Ferguson, kept the boy awake for some time that night. When he slept, at last, he was almost immediately awakened by a confusion of frightful sounds. The shriek of the winds and the pounding of the sea showed that "no small tempest was upon them." Frantic voices cried that a mast, or spar, had fallen, that the captain was killed, the boats were all swept away, and that the ship was sinking. Eight hundred fear-crazed men, with a score of women, all penned in the pitchy dark, under fastened hatches, screamed, cursed, and called on the saints, while the ship seemed to roll nearly over, and Ned shuddered as he clung to his hammock and tried to pray. Then through a lull in the tumult he heard a woman singing—

"Jesus, Lover of my soul, let me to Thy

bosom fly,

While the nearer waters roll, whilst the

tempest still is high."

"It's the Swaddler's wife," Ned heard Tim Kelly, an ignorant Irish giant, groan, "Sure, it's hitting him has brought this on us. A man that hits a woman or a priest never has no luck. Mary! save us all, we're going now. Boys, ask the Swaddler to pray. Sure, a heretic priest, if he's a good living man, is better than none, when it comes to dying."

A hundred voices called to Ferguson, and men were silent, while between the roars of the wind the Methodist spoke, the perfect calmness of his voice reassuring the terrified people. Bit by bit he shouted the story of the Man who walked on the sea of Galilee, and who slept in its wildest storm, only waking at the prayer of His frightened companions, to still winds and waves with a word.

"The "Lightfoot" weathered the storm—thanks to Ferguson's prayers, Kelly and his mates believed, and they treated him with the rough respect which the south Irishman, lovable and unreasonable, superstitious and chivalrous, gives to his women and priests. They tried not to swear in his presence, and took his reproofs meekly when they forgot themselves. Sells and the few like him who were really thorough blackguards dared not say a word.

"You see, Ned," said Ferguson, "how God can change the lion into a lamb, and cause enemies to become friends."

Ned smiled, thinking—"The old Greeks were right when they said the gods help those who help themselves."

There was now a dead calm. For several days the "Lightfoot" lay idle on the sea. The soldiers' rations were reduced, and as the calm continued, reduced again. The drinking water became unspeakably foul. It was a time of considerable anxiety for the officers—eight hundred men, illiterate and coarse-minded, the class that thinks most of what it eats, were now only half fed. Every hour they looked for trouble, ready to meet it with the utmost severity—yet it did not come.

"I don't understand," said the colonel over his wine after dinner. "Here's a mob of Irish recruits who are probably all rebels in their hearts, and a few score English blackguards. What's making them behave?"

"A Swaddler named Ferguson from Ulster, I think, sir," said Dr. Tam. "In some utterly incomprehensible way he has managed to mesmerize a crowd of south Irish into imagining he is a priest. He is suffering still with sea-sickness, and he lives on air and saying prayers, but he is always cheerful, makes jokes on his own privations, and is so tactful with his religious talk, that the men are ashamed to complain before him."

"Hum, I don't believe in Methodists and these preaching soldiers, but this seems to be an exceptional case. But why isn't he in hospital having proper food, if he is as sick as you say?"

"I wanted him to go, sir, but he didn't."

"Are you in the habit, Doctor, of letting your patients decide whether they shall obey your orders or not?"

"As you said, sir, Ferguson is an exceptional case. Under the circumstances I thought it best to let him have his way."

"Hum, yes, but we can't have a man like him sacrificed to keep a rabble in order. I'll go and see him myself."

So the colonel stood with Percy and Dr. Tam by the Methodist's hammock. Ferguson was too weak to rise, but he answered the colonel's inquiries very cheerfully—"Thank you, sir, but I have everything I need and more. I don't have to depend on food to sustain me while I have the Book which says 'man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceedeth from God'."

"Er, that is, of course the Bible is a very good book," blurted the Colonel, somewhat at a loss, "but if you require anything, mind and let the doctor know."

As they returned to the deck he said abruptly—"What's that man's record before he joined us? What's he doing in the ranks after three years service?"

"His record's all right, sir," answered Percy, "but he is a Methodist first and a soldier afterwards. He has spent the bulk of his time as an officer's servant, preferring that to being a sergeant, as it gives him more liberty and more time, to go out and preach."

"And suppose I object to this regiment being made a convenience for the Methodist itinerancy?"

"Seeing the Methodist itinerancy in the shape of Ferguson is being a great convenience to us, sir, I don't see the reason for your objection."

"Well, well, we will see. Doctor, don't let that man starve himself outright, while he is shaming the others into not complaining."

Then the welcome wind came, rations were increased, and on September 17, Ned saw Canada—Halifax, with the deep green of the all-embracing forest round her, and the vivid scarlet of the British flag still above her forts.

The regiment with its officers, and the soldiers' wives were packed on the "Herald", a little 70-gun warship. They sailed up a mile-wide river, Ned straining his eyes to see a line of distant hills clothed with the same unbroken forest. Then the hills were blotted out by dark driving clouds, and sheets of rain. The waves rose, and the "Herald" plunged through a night of storm and great discomfort to all on board. Sunshine came with the morning, but the ship stopped off a rocky mountainous spot, with no sign of human habitation. Orders were given, the men took their arms and knapsacks, the women their children, and all were landed with much difficulty.

There was no sign of a road anywhere. They climbed a rugged slope only to descend on its further side, and find another and steeper one before them, many of the men having to get up the worst places on their hands and knees. Mrs. Ferguson was being helped by Dr. Tam, and Ned took her child on his back as they scrambled up the second hill and slipped down it into a wide deep bog.

"Sure, and I don't see why we don't present this country to the Yankees as a gift," grumbled Tim Kelly. "It's not fit for a decent Christian to live in. I don't wonder it hasn't any people. Murder! there's my shoe gone, and I daren't swear with the little Swaddler so near."

"Forward," said a voice, and with demoralized ranks the regiment crawled out of the mud, leaving many more shoes behind it. Night came, but there was no halt till it seemed to Ned that he had spent weeks falling over bushes and into creeks. At last, however, the worn-out men were allowed to rest, and soon forgot their fatigues as they ate their suppers round huge fires of logs, and then bivouaced by them.

"I wonder where we are, and if the enemy is anywhere near?" said Ned as he lay down by Ferguson, "I guess you are pretty done up."

"I certainly feel the need of being under the grace of God," said the Methodist, "to lay the rough path of my peevish nature even, and open in my heart a constant Heaven."

The next day they marched back to the ship, and soon reached Quebec, the excursion being an official idea to "break-in" fresh troops to campaigning in Canada. The fortress city on the cliff with the many priests in her streets, and French spoken everywhere, seemed very foreign to Ned.

"I thought Canada was English," Ferguson said to him as they went out together.

"And so she is, stranger," said a fine looking man, who after watching them closely, stepped up beside them. His speech and manners showed education, though he wore a hunting shirt of buckskin, and blue cloth trousers with fringes on the seams. A skin cap, beaded moccasins, and a silver-handled hunting knife in his belt completed his costume. He went on talking in the same frankly friendly manner, telling of the first invasion of Canada, across the Detroit River, by General Hull, with twenty-five hundred American troops.

"He sent us a proclamation—'To the People of Canada'—telling them to choose between the 'peace, liberty, and security' he'd give them if they'd hurry in and be annexed, and the 'war, slavery, and destruction' they'd get if they didn't.' Canada didn't seem to want his 'peace and liberty', especially after he had given us a sample of them by raiding on the Canadian side. Then Brock left York with three hundred regulars, four hundred militia, and five guns, and near Detroit he met Tecumseh with seven hundred Shawanese."

"Excuse me," said Ned, "but we don't know who these people are."

"The Ohio river Indians—they've been scrapping with the Yankees all along, and Tecumseh, their chief, thought if we were fighting them too they might as well join hands with us."

"I've heard of the Ojibways and Mohawks," said Ned. "My father is a trader in York, and he wrote me that Upper Canada would raise six thousand militia, and her Indians could send in four thousand men as well."

"Canadian Indians are all right," said their friend. "They're under our government and laws, but Indians don't fight like white men, and as the Shawanese are only our allies, we mayn't always be able to control them. But it will be all right as long as Brock's at the head of things. On August 15, with only fourteen hundred men, half of them Indians, he moved to attack Detroit, and Hull with twenty-five hundred in a strong fort, capitulated."

"He was a coward," exclaimed Ned.

"Not so fast, son. He had Detroit with its women and children to think of. He knew what it would mean if it was stormed by Indians. In his place I'd have surrendered to any decent white man."

"Well, that's one victory for us," said Ned.

"We would have had more, but Sir George Prevost, the Governor-General, made an armistice with the Yankees. He hoped to make peace, but they wouldn't meet him, and only used the time to arm their ships on the lakes. And now, I suppose I may introduce myself, I'm James Edgar, of York, and I'm down here to meet Ned, my son."

* * *

After a joyous greeting, Ned was hurried off by Edgar to the little steamer "Accommodation", the first of her kind on Canadian waters. For nineteen shillings she took them to Montreal, giving them food, and letting them "berth" with their blankets among her piles of freight. At Montreal a score of bateaux—broad, heavily-built boats—were waiting, and Ned was surprised to find his father in command of the Indians and white men in buckskin shirts who manned them. They were loaded with ammunition, and meant to run the gauntlet of the guard the Americans kept on the river between Montreal and Kingston, blockading Upper Canada—now Ontario.

Ned was standing, nervously alert, his hands gripping the long rifle that still seemed strange to them. Before him was a strip of water, and all round him was forest—the gorgeous colored autumn trees of the Thousand Islands. The Canadians were travelling by night and hiding by day, for the two American warships that kept the lake sent their boats out searching constantly. Ned had been set as sentry by Tahata, the Mohawk, who was Edgar's lieutenant, and he was very afraid of failing to see some one of the little things which are important on watch duty.

He stared at a boulder jutting out in the shallow water. A minute ago bushes had screened its shore side, now they were certainly further along. With a remembering of the trees that marched to Macbeth's castle, Ned gave the bird call Tahata had taught him for an alarm, and instantly two lithe brown men appeared at his side. The suspected bushes stirred, showing part of a deerskin clad man, and all the Indians' alert savagery vanished. Muttering, "It is Kaanah," Edgar's Indian name, they lounged back to their places.

Edgar stood up, taking the branches out of the loops in his garments, and walking lightly, he passed Ned with a smile, and came to Tahata. "The Long Knives' (Americans) ship has passed," he said. "We will go on at dark. And what of the boy?"

"He has lived with men who did not know how to see," answered the Indian, "but he will learn, for he does not make the same mistake twice."

"I wanted to see if you would notice me," said Edgar to Ned later. "I did not think you would be so quick."

There was pride and affection in his voice, and Ned almost worshipped the father who, a few weeks before, had been a stranger to him. So they journeyed on, escaping a hundred dangers through Edgar's careful leadership, for he was indeed just such a man as would be a hero to any boy; and finally reached Kingston with their cargo—Kingston with all her flags drooping at half-mast.

Edgar hailed a red-headed young man on the deck of a smart schooner—the "Susan". "What's happened, Archy?" he called.

"Pretty bad news, Mr. Edgar. Them blamed Yankees got across Niagara river before daylight on October thirteenth. While our boys were beating them off at Queenston, a lot more sneaked up the mountain, took our battery there, and dug themselves some real smart trenches, then fired down on us. The York 'Gazette' said they were 'villainous aggressors', and there were a thousand of them."

"You red-headed blockhead," shouted Edgar. "Do you mean to say we're half-masting our flags because we're invaded?"

"Now don't get mad, Mr. Edgar," said the imperturbable Archy. "We're not invaded. General Brock started up to rout them out, but the firing was too hot. It's durned difficult to run up a mountain with sharpshooters firing at you from behind logs and earthworks. He went back, but only to try the other side with a lot of redcoats. He passed our boys, and he said, 'Forward, York Volunteers', and you can bet them volunteers did go forward."

"I see," said Edgar with sarcastic resignation. "We won Queenston Heights, and then put all our flags at half-mast."

"I meant, Mr. Edgar, that General Brock was shot dead as they charged the second time, and the boys had to go back. That's why the Yankees are calling it their victory, though General Sheaffe took command. He had fifteen hundred men, half of them Mohawk Indians, and they went up the heights in three parties, and smashed the Yankee lines. The 'Gazette' said 'Our unprincipled neighbours were totally defeated', but we hereabouts are only thinking that General Brock is dead."

* * *

So Ned heard the story of Queenston Heights, a fight which the American histories record as a "frontier skirmish of no importance but on the whole in favour of the Americans," while Canada lauds it as her great victory, on each 13th of October raising the flags on her schools and telling her children how Brock died. His ringing last command, Toronto has taken as her watchword—"Forward, York Volunteers!"

And in reality, the American invasion was little more than a reconnoitre—a test of the strength of the enemy, and its repulse was nothing in comparison to Canada's loss in Brock's death at that time. Yet we do well to count it a victory, for that tall granite shaft—Brock's monument on Queenston Heights—overlooking the gorge of wild Niagara, is Canada's declaration of independence. When our gray-coated militia charged up the heights beside the scarlet-clad English regulars, we affirmed that this North American continent was large enough for the growth of two nations and the flying of two flags.

Edgar and his party went on board the "Susan", and Ned was surprised again to find his father here also in command. The voyage had its excitements, as Archy explained to Ned. "Them blamed Yankees have ships all over the lake. We have some too, but we haven't, and can't get, a gun heavier than twelve and eighteen pounders, while theirs are twenty-four and thirty-two pounders, which means they can send a heap heavier shot. I was captured with the 'Susan', going to Kingston this time."

"How did you get away?" said Ned, hoping for a story.

"I left Niagara just after the battle to run to Kingston, to meet you, and to take General Brock's papers and stuff there. There was a bit of a blow, and the 'Susan' was caught inshore with a Yankee waiting to blow us out of the water as we came 'round. Course, I surrendered. Says the Yankee. 'What ship's that, and what's your lading?' Says I, 'Susan', Niagara to Kingston, with General Brock's papers and things'. 'Pass,' says the Yankee, 'General Brock was all right, and I'm real sorry he's dead'. And he dipped his flag to me. That Yankee was a gentleman and I've known others like him. I don't like this having to fight with them."

"But you wouldn't let them take Canada?"

"No, sir, you can bet your sweet life that Canada won't let no Yankee boss her into changing her flag. They're too blamed interfering, and old Upper Canada'll fight while she's got a man left to hold a gun. Maybe they'll remember not to come in here again. That's York."

Ned saw a narrow peninsula, curving round to form the harbor. It was the promontory that has since become Toronto Island. The entrance was on the west, between Gibraltar Point (Hanlan's), with its lighthouse and blockhouses, and on the mainland, Fort Toronto, and Western Battery. These consisted of earthworks and massive log barracks, armed with a few small cannon, where the present fort now stands.

The "Susan" sailed past the forts down a placid sheet of water. On the right Ned looked across the low sandbanks of the peninsula to the lake stretching away to the horizon. On the left was open ground where cows grazed, and beyond, the long wall of the forest. Then they were abreast of Half-moon Battery (Bathurst Street), where stood the Governor's "Palace", a big log house in the form of a half square, with verandahs round its inner sides, and a garden shaded by stately oaks. There too were the quarters, with their magazines and storehouses.

Then came more pasture and the "Susan" stopped at the wharves, (John Street) east of which lay the little town of York, with its nine hundred population, and three straggling streets—Palace Street (Front), which had houses only on its north side; King Street, and Lot (Queen)—then came the bush again. Yonge had wheat fields on either side, and was only known because it ran north into the bush where it became an Indian trail ending at Georgian Bay, and down which the natives came with their furs each spring. All the buildings were of logs except the two brick houses of parliament, of which York was inordinately proud. They stood on open ground by the mouth of the Don.

Edgar was now wearing his uniform and sword as a militia major; Tahata was in elaborately fringed and beaded buckskin, with silver mounted tomahawk and scalping knife—and a tall black silk hat! Ned in the clothes his father had given him, wore a fine cloth suit and starched much-frilled shirt, with silk stockings and silver shoebuckles. He was realizing that Edgar, militia major, wealthy trader, and member of the Upper Canada Legislature, was a man of importance.

As the "Susan" stopped, a pretty woman, in lavender silk, with a huge bonnet trimmed with flowers and green gauze, came on board, and Ned was introduced to his stepmother, with his half-brothers, three small boys, between ten and three. Ned and Susie Edgar liked each other at first sight, and were glad to leave together for shore, where Edgar, Tahata and Ned were to go to the "Palace". It was only a log house carpeted with skins, but all the formality of a petty court was observed within.

"General Sheaffe, whom Brock's death has made our governor, is a Swiss," Edgar told Ned. "He entered the English service when his country was over-run by France, and being bred in a Republic, he seems afraid of not being formal enough in his position here. Still a deal of ceremony is good policy with the Indians. A lot of the trouble they have had in the States is because the Indians have imagined an insult in some informality in council."

After Edgar had made his report to the coldly formal Sheaffe, and they were going home, he said to Ned. "Of course you will join the militia now, in the ranks. You may wonder that I don't buy you a commission. I would promise you that I will in one year, only I know by then you will have earned it."

Still talking Edgar reached his great store, crammed with goods for Indian trading. Ned was getting his first sight of the spirit of the new world, the ignoring of class distinctions, and the determination to rise.

"This isn't England," Edgar said. "Here the people own the land and pretty soon will have the ruling power, and the men whom they will choose for leaders will be those who have worked beside them, yet risen by their own work."

Ned felt chilled. He of all people felt no shame in humble beginnings, but his father's standards of value depressed him. He wondered what he would think of his Methodism.

Then Ned was taken into the house, built of logs. It had hall and living-room, the last with open fireplace, brass andirons and fender. Tall brass candlesticks stood on the mantel, the rugs were of fur, and the furniture rough made, but the sideboard held a fine array of silver plate, which society then demanded of every one who would hold position. Army officers dragged it through the bush with them, and wealthy traders proved their station by the amount they owned. There were books too in the parlor, which made Ned feel more at home. He followed his father past the four smaller bedrooms, and the big guest chamber, furnished with bunks round its walls, into the great kitchen, where the family ate and spent most of their time. Ned noticed a jug of whiskey with a cup on a small table, for any one to help himself. Then he sat down to supper.

The table was loaded with broiled venison, ham, homemade bread and butter, cheese, fruit pies, tea for Susie and the children, and whiskey for the men. On duty Edgar never touched anything but water, but now he frowned as Ned refused the whiskey black Bob handed him. At that time almost all the house servants in Canada were negroes, and Susie kept two, Bob and Fanny.

"Don't be a Methodist, Ned," said Edgar.

"I am one, sir."

"Was one," said Edgar coolly. "I let you come out forward to knock the nonsense out of you."

Ned wisely said nothing, and the next day he put on the dark gray uniform of the Canadian militia, took the oath to serve the king and obey his officers, being pleased to find that his captain was Archy, his father's employee. He enjoyed his new life and threw himself with such zest into his six hours of hard drilling a day, that Edgar gave him half grudging approval, but he was still unreasonably sore at his son's steady refusal to drink "like a man."

The war was still going on. Though American attacks on Lower Canada and Kingston had been repulsed, and 1812 closed with Canadian soil still free from the enemy, and the English flag over Detroit. Yet with their splendid naval victories the Americans were confident of conquest. It was the good seamanship shown in these fights which caused dismay in England, and filled the new republic with thoughts of its own naval supremacy. Canada took the news stoically; England's hands were too full in Europe for her to send out further ships. Certainly England would conquer Napoleon some day, and till then Canada would "hold the fort".

In January, 1813, an American force marched two hundred miles through a wilderness to retake Detroit. They were defeated, and Proctor, the English general, was unable to keep his savage allies from butchering many of the prisoners who had surrendered to him. All over the States this caused justly bitter feeling. Forty dollars was offered for the scalp of any Indian fighting in the British ranks.

"Don't speak of that at home," Archy told Ned. "Women folks are awful easy scared, and it'll hit your pa." For the English, to keep their Indian subjects under better control, had given Indian military rank to the white men, who like Edgar, had been elected sub-chiefs.

* * *

Ned found Susie interested in other things than war, when he went home that March evening. "General Sheaffe is back, Ned," she exclaimed, "with Bee and her grandfather, and two companies of regulars. There's going to be the ball of the season at the Palace, and I must find out if the fashions have changed much."

"They always change the same way, Sue," said Edgar, "less dress and more bonnet. It's Bonaparte's wife that starts them, and if I were he I'd suggest that she tie her dress round her head, and dress the rest of herself in her bonnet, for a change."

Then a small whirlwind, and Bee was in the House, in Susie's arms, laughing and exclaiming over the little boys, and Edgar welcoming his old friend, Dr. Tam. The surgeon handed Ned a letter. "From your Methodist friend, Ferguson," he said, and Ned hid himself in the lofts above the store, to read it without interruption.

"After you left us," Ferguson wrote, "we were ordered to St. Johns, near Montreal. We had to leave our families behind and had a severe and tedious march. The country and people and almost everything seemed strange, and not one of those I travelled with knew Canaan's language. But blessed be God, though I was a stranger and a pilgrim marching through the 'enchanted ground', I could now and then snatch a cluster of pleasant grapes, and see the end of my toils.

"On February 3, we marched to the Isle of Maux on Lake Champlain, where there has been some skirmishing with the enemy."

Ferguson went on with many quotations from his only reading—the Bible, Hymn Book, and John Bunyan, going rather fully into his examination of his own conscience, as to how a man could be a soldier and yet "love his enemies".

"I need to consult the Divine Oracle daily," he wrote, "for it is the soul's geography, which will show me the path I must needs take."

As Ned finished the letter, he saw his father and Dr. Tam come up into the next room which Edgar had fitted up as a "den", and sit down to drink together.

"Come in, and take your glass with us," ordered the half-tipsy Edgar, as Ned tried to pass the door unseen.

"Yes, come," said Dr. Tam, "even if you are a Methodist. Lots of them take their glass, its only their preachers and saints that set up to be so extra good. Come, you'll never be a man till you drink."

"You're no Methodist," roared Edgar, as Ned sat down unwillingly. "What do you mean by writing to them? Give me that letter that you got from one of them to-day, or I'll break your neck."

Ned obeyed, though his eyes flashed. Edgar read the letter, then burst into a torrent of oaths. "The canting coward," he shouted, "to take the king's pay and dare to talk of loving his enemies! And what's this gibberish about picking grapes in a Canadian forest in mid-winter? See here, you'll give me your word right now to drop this Methodism, or I'll flog it out of you to-night."

Ned sprang to his feet. "You can do what you like to me, sir," he said sternly, "for you are my father, but if you do touch me, I shall leave your house and never enter it again."

"Steady, man," said Dr. Tam, with his hand on Edgar's arm. "The laddie's threatening to disinherit you, instead of waiting for you to do it to him. Now, listen, I'm an officer in Ferguson's regiment, and no matter what he puts in private letters, which are none of my business, I want to tell you something. Down at Lake Champlain the Governor-General, Prevost, visited us. We were to make an attack on the Yankee camp, and the night before I heard Ferguson preaching to the men. He told them that being ready to die made a man more fit to live. A Christian soldier can do his duty more calmly and bravely and be more true to the king and obedient to his officers.

"He was standing on a box by a camp fire, with the men all 'round him listening in deep silence. I saw the colonel come up with Governor Prevost, who seemed surprised at a soldier's preaching. The colonel said to Captain Haslem, who was there—'What kind of man is Ferguson? Does he do his duty?'. The captain said—'He is always ready for any call; all I ever heard against him is his preaching, and reproving the men for swearing.' The Governor said—'I think we will let him go on then. The army needs some chaplains.'

"The Yankees were gone when we went the next day. Our men plundered the farms quite a bit. I kept my eye on Ferguson, and saw that he not only never touched a thing, but kept the men near him better behaved than they would have been. Now, you let the lad be till the lake opens. There'll be stiff fighting then, and if he does his duty let him have what religion he likes."

Edgar nodded grumpily, and as Ned left the room, he added, "If he fails I'll send him off. I've worked too hard to make a name here to have it disgraced by a Methodist coward."

He said very little to Ned during the next two months. On the twenty-fifth of April, the ice had cleared from Toronto Bay, and Bee, in her serge habit and plumed hat, sat very upright on her horse as she rode by Sir John along the muddy water front to the wharves.

"They are very slow with those ships," she remarked, with the air of a naval expert. "Major Edgar says there is too much red tape."