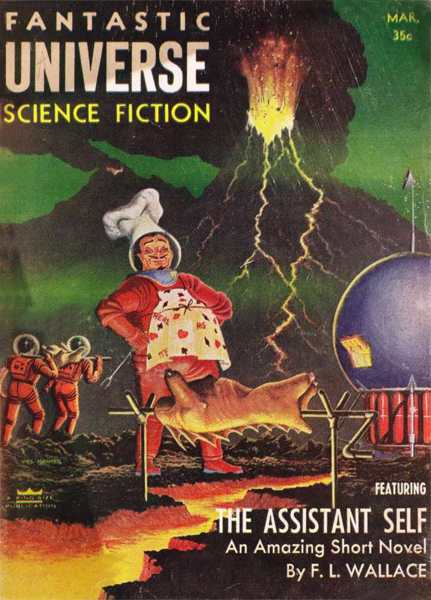

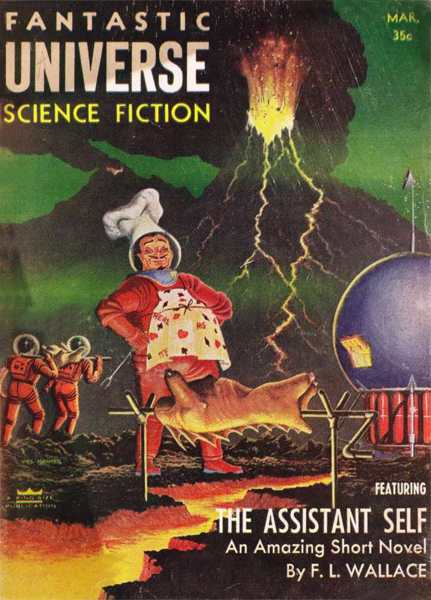

Title: Memorium

Author: Basil Wells

Illustrator: Mel Hunter

Release date: November 24, 2025 [eBook #77316]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: King-Size Publications, Inc, 1956

Credits: Sean/IB and Tom Trussel

by Basil Wells

An old man’s memories may be filled with bitterness. But faithfully recorded, they may change the future of mankind.

Did you ever wonder what would happen if the thoughts of every man, woman and child on Earth were set down in black and white for future historians to read? Or even present-day historians—or your next door neighbor? Could you endure having all of your thoughts laid bare, from the cradle to the grave? Wait before you answer. Basil Wells may persuade you to change your mind.

“Tell me about Gramr, Granthr,” the thin-faced little boy demanded. “You promised to tell me about my three Gramrs.”

Vance Norall’s attention snapped reluctantly back to his visitor. It was perhaps not surprising that he should have dropped off for a moment. At a hundred and thirty such a lapse was understandable ... His eyes cleared.

“Ah, yes. Your great, great grandmothers, Ronnie. First of all there was Elsie. A lovely woman. Tall she was—taller than I, and dark. She rode well, swam well—even played championship golf. There was nothing she could not do.”

Including lying, his mind wanted to add. After her death, when in a fit of anger she had driven too fast and crashed into a nest of highway posts, her memorium tapes had been brought to him in the hospital where he was recuperating. And from the tapes he learned what he had never really suspected—that her affections were as unstable and as unpredictable as her golf game was accurate.

She had loved him. The tapes, at five year intervals, had confirmed that. But in the fifteen years of their life together she had had many regrettable episodes to recall—times when anger or loneliness had driven her to seek other companions.

“We were happy, Ronnie. I was teaching in an upstate college and your Gramr Elsie was touring the world collecting trophies. I remember seeing her on television talking with kings, prime ministers and presidents...”

It had been a miserable, lonely life for Elsie. The tapes told the real truth of those years. Her gay letters home had been mainly untruths. Yet a hard core of ambition, of a hunger for adulation, had driven her on. His first hurt anger at what her memories had revealed had changed to sympathy and pity as he came to understand her better.

While the second boy, Arthur, was being born he had resigned from his instructor’s position and gone into business. And Arthur’s birth had left Elsie in poor health. Her globe-trotting days as an athlete and a golfer ended. And in rebellion she had struck back at him blindly and secretly—childishly.

The last wild ride that had taken her life, had almost cost him his own, and the will to suicide had colored all of her thinking in the last long period before that tragic event.

“Of course, Ronny, Gramr Elsie remained at home after your great granthr was born. And after she was killed in an automobile crash all her trophies were put into a case at the Country Club.”

“And after that you married Gramr Vivian, and became very wealthy, and you built this living dome here in Antarctica near the mines.” Ronnie smiled gravely. “That part I know very well.”

Yes, that part Ronnie knew very well. But Ronnie had not known the austere efficient nurse, his second wife, who had cared for him after the accident. She had been a dutiful and thoughtful wife—a perfect mother to Elsie’s two sons and their own three daughters—but always there had been a feeling of reserve between them. Even in their most intimate moments she had seemed self-sufficient and respectful ...

Only after her death in her sleep, when he was sixty and Vivian was fifty, had he learned that she had a rheumatic heart, and should have slackened her headlong pace years before. And from her memory tapes, sent to him by the memorium proctors six months after the burial, he learned how distorted and cramped had been her philosophy of life.

She had hated and disliked all men—a silly, slightly sordid romance in her girlhood was her mental excuse for this attitude. Inwardly she shrank from any sign of affection, or any physical contact with him. Yet she desired marriage for the social status and monetary independence it afforded. Bitterly she had paid the price ...

“Gramr Vivian was an unusual woman,” Norall told Ronnie, an ironical tone to his surprisingly strong old voice. “After she died I did not plan to remarry. I spent all my time in Antarctica building subterranean highways and developing mines...”

“Until Gramr Eldris Arovvack,” Ronnie rolled the Arovvack on his tongue, “came down to visit her son in one of your camps.”

“I think you know all this better than I do, Ronnie,” Norall said, laughing. “Maybe I should tell the proctors to destroy my memory tapes after I am gone. You will not need them.”

“Oh, no, Granthr! It is against the law. Only after a hundred years without a withdrawal from the files can a memorium tape be destroyed. I wish to keep in touch with you—it will be like talking with you again.”

“I see the proctors are doing a good job of indoctrination in the schools, Ronnie.” Norall sighed. “When I was your age, back in nineteen-fifty, the universal recordings of all citizens’ memories was not even imagined.

“That came in the seventies. The Communists developed the system of brain stripping and recordings to weed out subversives and disloyal party members. They adapted it from our own process of clearing a disordered brain, in our mental institutions, and giving the individual a fresh start with a blank memory.

“By the Twenty-first Century all the major nations were keeping mental checks on their citizens, and eventually even the party leaders, much to their horror, were checked and removed from office.”

“I know all that, Granthr,” Ronnie cried impatiently. “We have it in school on ever so many edutapes. They say that the memorium is the greatest deterrent to crime and vicious thinking.

“But I want to hear about the olden times—when there were wars and singing commercials and big ugly cities.”

“It was not so wonderful, Ronnie. Today is much nicer, and safer. When I was a boy we worshipped cowboys and pirates. Today it is the G.I. and the city gangster.”

“Tell me about how you and Gramr Eldris Arovvack were caught in the vehicular subway for three days after that earthquake, Granthr.”

“You know that by heart, Ronnie,” Norall protested, “but if you insist...”

Eldris Arovvack was in his mind’s eye even as his voice went on speaking. Eldris, so slight, so daintily feminine and so girlishly blonde and beautiful despite her forty years and her grown engineering son. They had been trapped together for three days in a subway shuttle and he had fallen in love despite the twenty-five years between their ages.

For her, he had realized, this was a marriage of companionship and luxury. She had always known poverty. His two previous marriages had given him an insight into why women marry, but so deep was his love for Eldris that he wanted to be with her under any conditions.

And they had been happy. Despite the continual gnawing realization that only his money and position had drawn them together, Norall had enjoyed a long sixty-three years of life with Eldris.

She had died but two years before...

“Granthr, I think I liked Gramr Eldris better than either of my other gramrs,” Ronnie was saying. “Of course she’s the only gramr I knew.”

Norall squeezed the little boy’s shoulder, hard.

It had been harder to accept the memorium tapes of Eldris than it had been to see her body disappear into the crematorium. For days he had refused to open the small sealed packets and insert the tapes into the reproducer. He felt that he could not endure to contact that beloved mind and feel there hatred, distaste and hidden foulness that humans too well know.

And when, in his great loneliness, he finally did renew contact with the recorded memories of Eldris, he was astounded—and humiliated.

For Eldris, through all the years of their marriage, had loved him. Her first marriage had ended in hatred, yes, and in pity for a weakling, but for Norall there was only a deepening respect and sincere affection.

And he had returned that love with a never-ending mistrust and cynical suspicion of her motives!

But he was happy now. After Ronnie left he would be alone again with her memorium tapes. Together they would relive the long happy years of their marriage. He would share her sadness as she felt that Norall did not care enough and he would feel her joy as their grandchildren, and their children, came to visit and to be married in the old family dome.

He must have been napping for the fraction of a second...

“I must go now, Granthr. You are tired. Mother says I am not to tire you.”

“Come again tomorrow. And Ronnie!” His bony arm reached out for the boy’s gay blue tunic. “After I am gone and you are old enough to withdraw my tapes from the memorium library and contact them—”

He paused, his frail old fingers tightening on the fabric.

“Do not think too harshly of me and of your other granthrs and gramrs. When we were young we could not know that after death all our thoughts would be laid bare. Our parents and our nations did not know, and we were fed untruths that colored all our lives.”

The little boy’s thin face was puzzled.

“Run along,” Norall said softly. “Some day you will understand.”

He sent the wheelchair buzzing over toward the memorium tapes and the soft gray helmet for his head even as the door closed behind the boy.

This etext was produced from Fantastic Universe, March 1956 (Vol. 5, No. 2.). Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

Obvious errors in punctuation have been silently corrected in this version.