THE VIRGIN OF THE ROCKS

Title: Six lectures on painting

delivered to the students of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, January, 1904

Author: George Clausen

Release date: November 24, 2025 [eBook #77311]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Methuen & Co, 1904

Credits: deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

DELIVERED TO THE STUDENTS OF

THE ROYAL ACADEMY OF ARTS

IN LONDON, JANUARY 1904

BY

GEORGE CLAUSEN

A.R.A., R.W.S.

PROFESSOR OF PAINTING IN THE ROYAL ACADEMY

WITH NINETEEN ILLUSTRATIONS

THIRD EDITION

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

Originally published by Mr. Elliot Stock April 1904

Second Edition September 1904

First Published by Methuen & Co., Third Edition 1906

| I. | Introductory—Some Early Painters | 1 |

| II. | On Lighting and Arrangement | 23 |

| III. | On Colour | 45 |

| IV. | Titian, Velasquez, and Rembrandt | 67 |

| V. | On Landscape and Open-air Painting | 89 |

| VI. | On Realism and Impressionism | 113 |

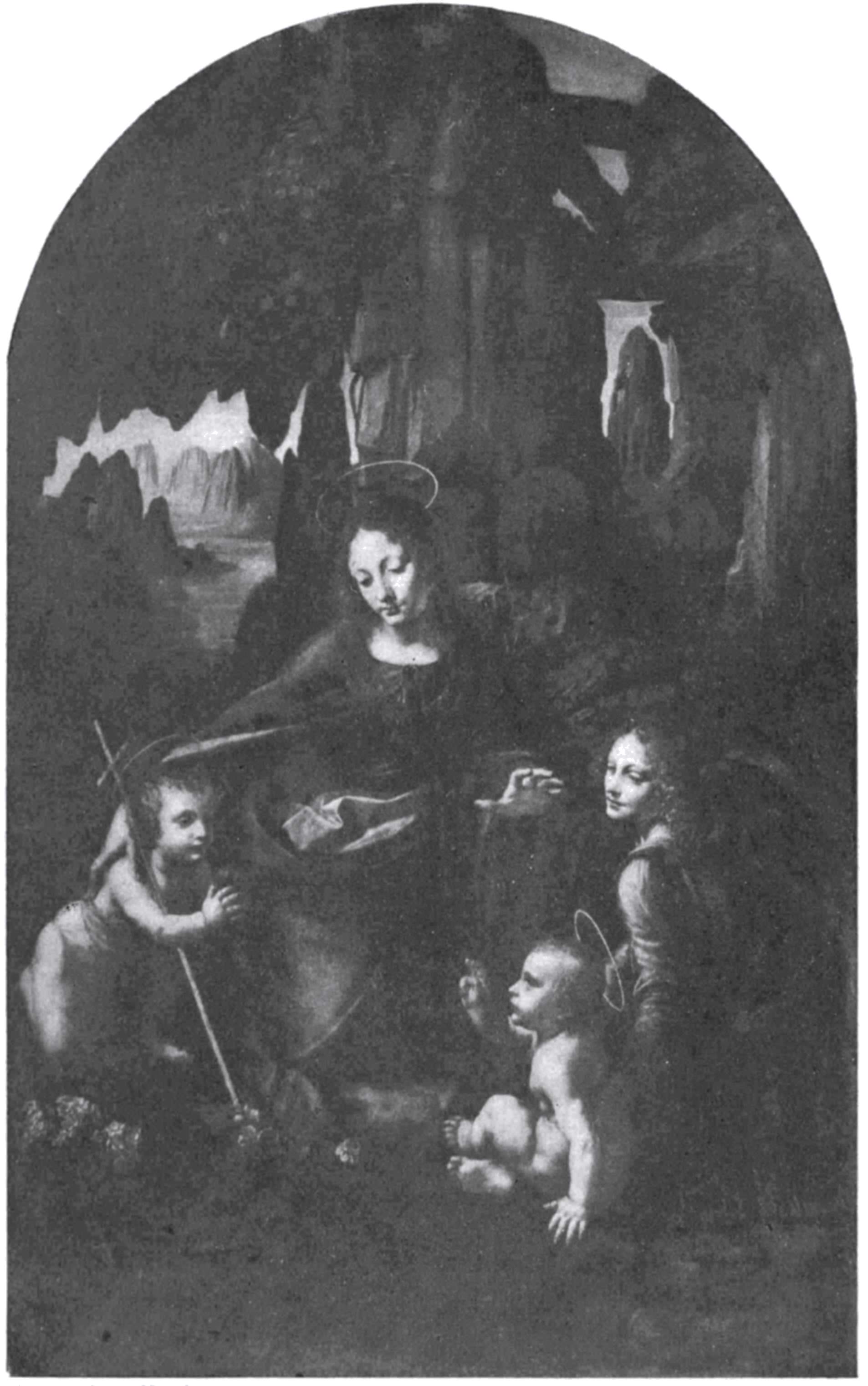

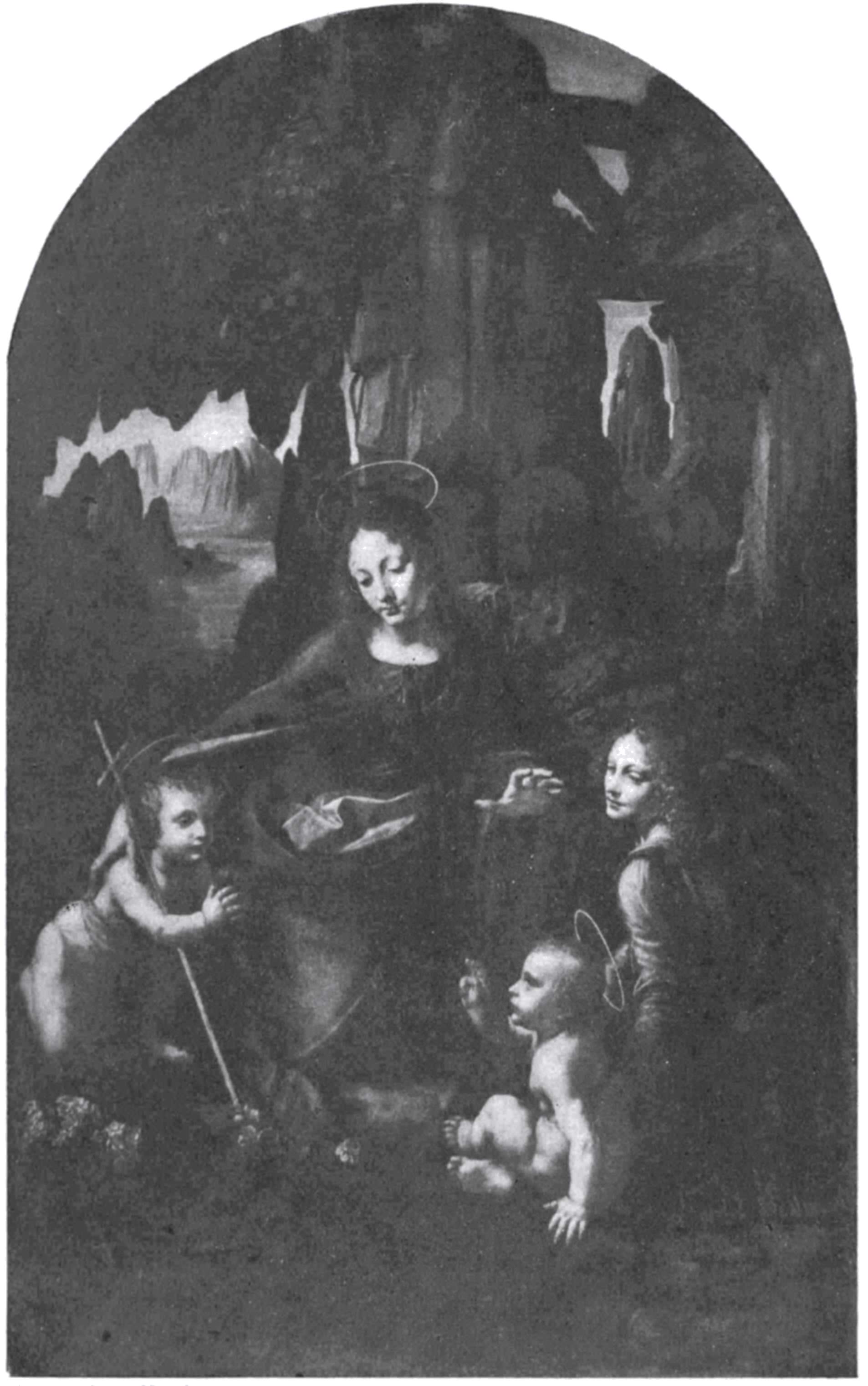

| The Virgin of the Rocks | Leonardo da Vinci | Frontispiece | |

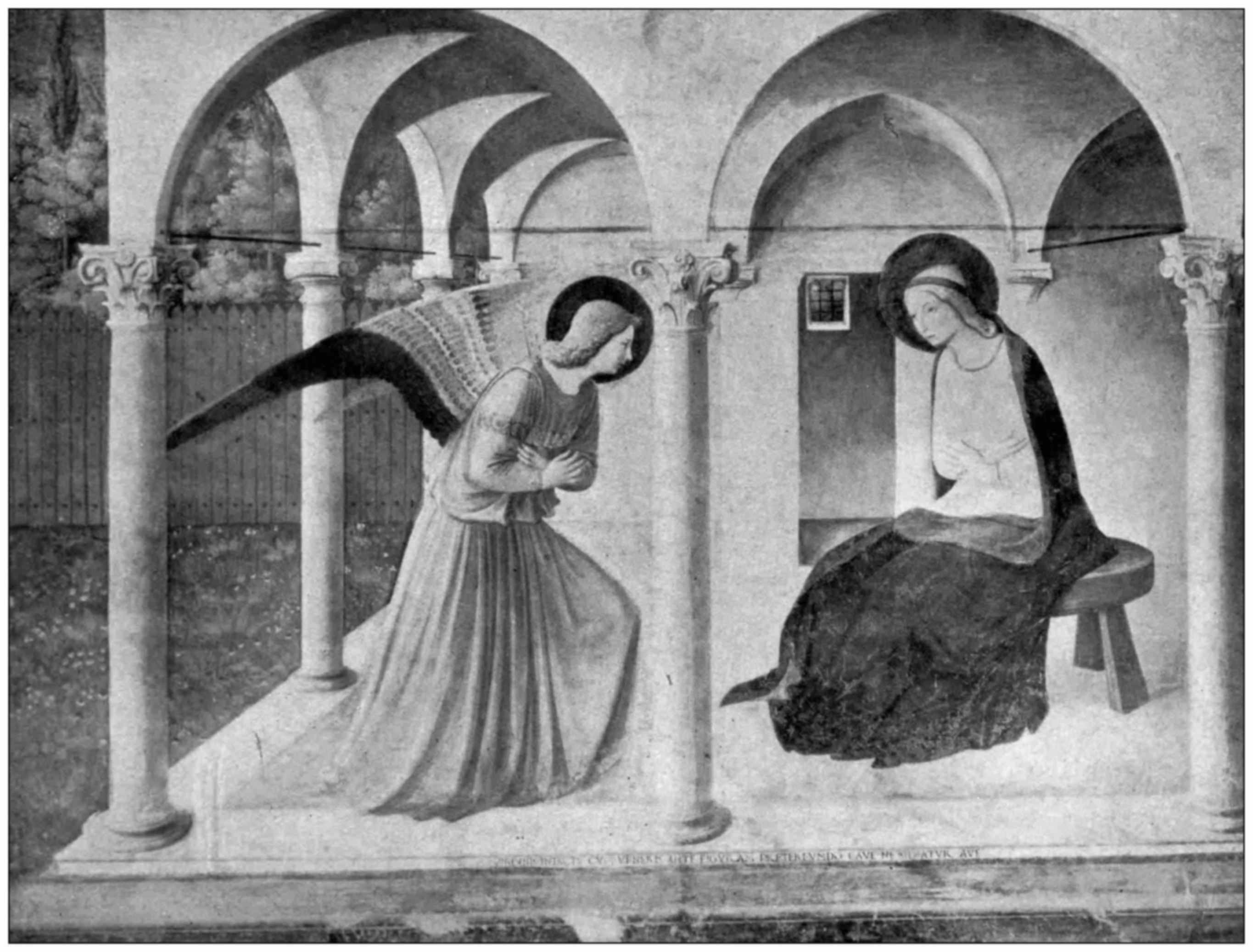

| The Annunciation | Fra Angelico | 14 | |

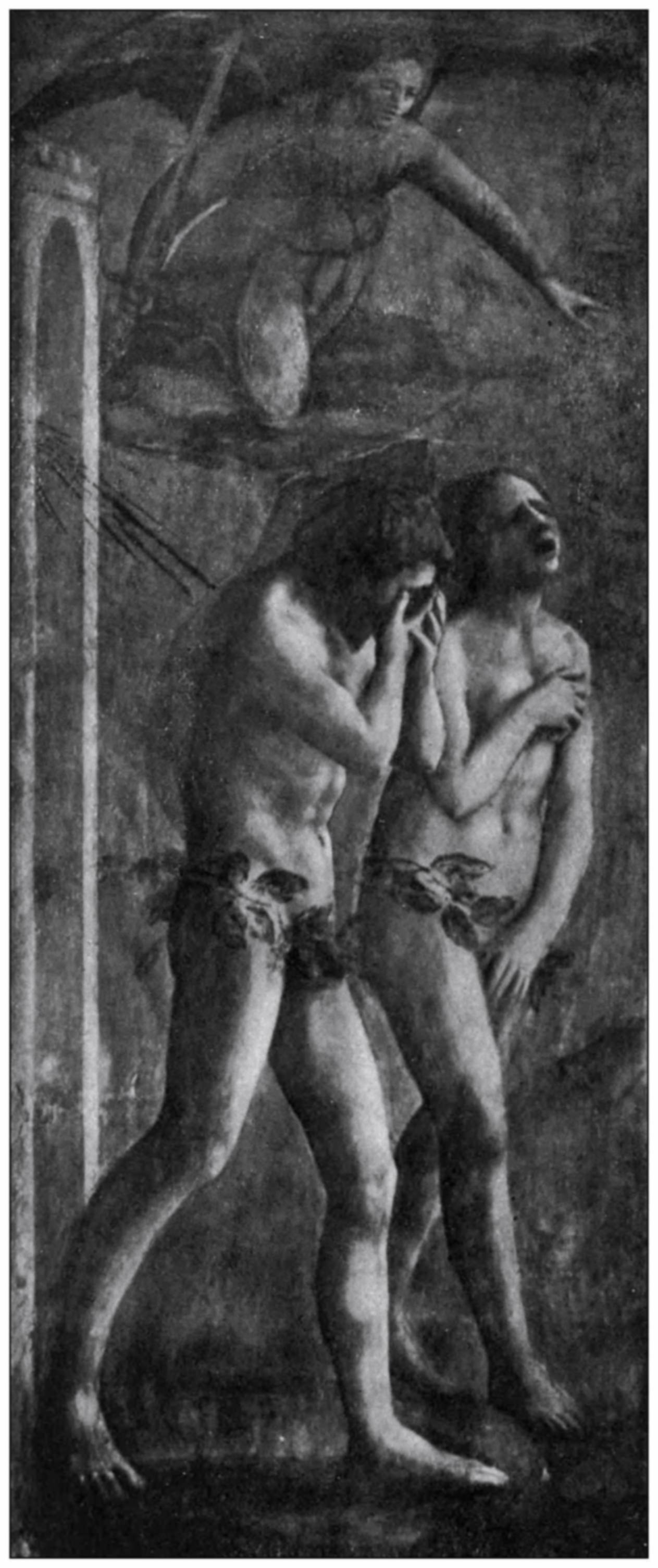

| The Expulsion from Paradise | Masaccio | 15 | |

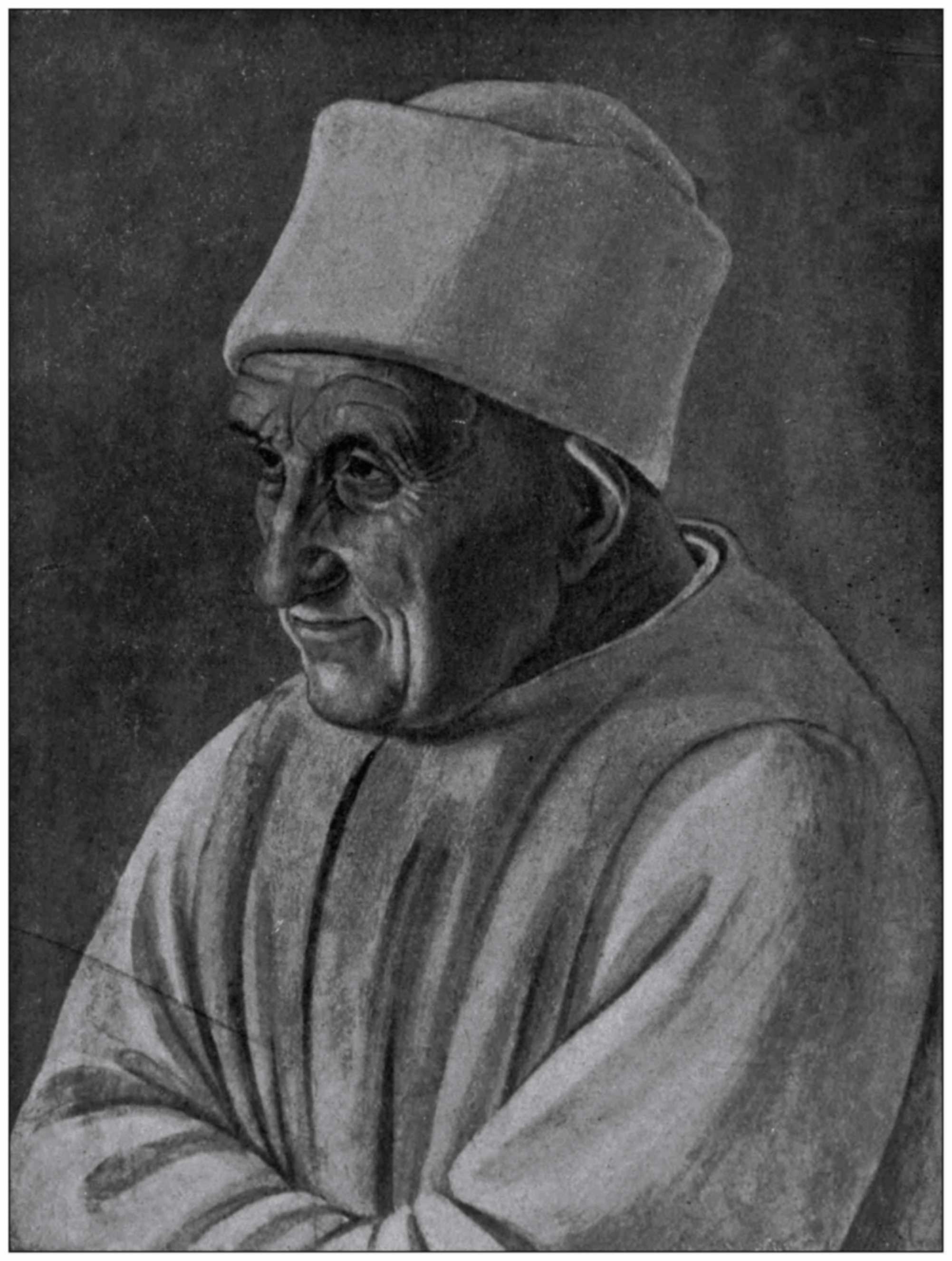

| Portrait of an Old Man | Masaccio | 18 | |

| Diagram of Composition | Corot | 33 | |

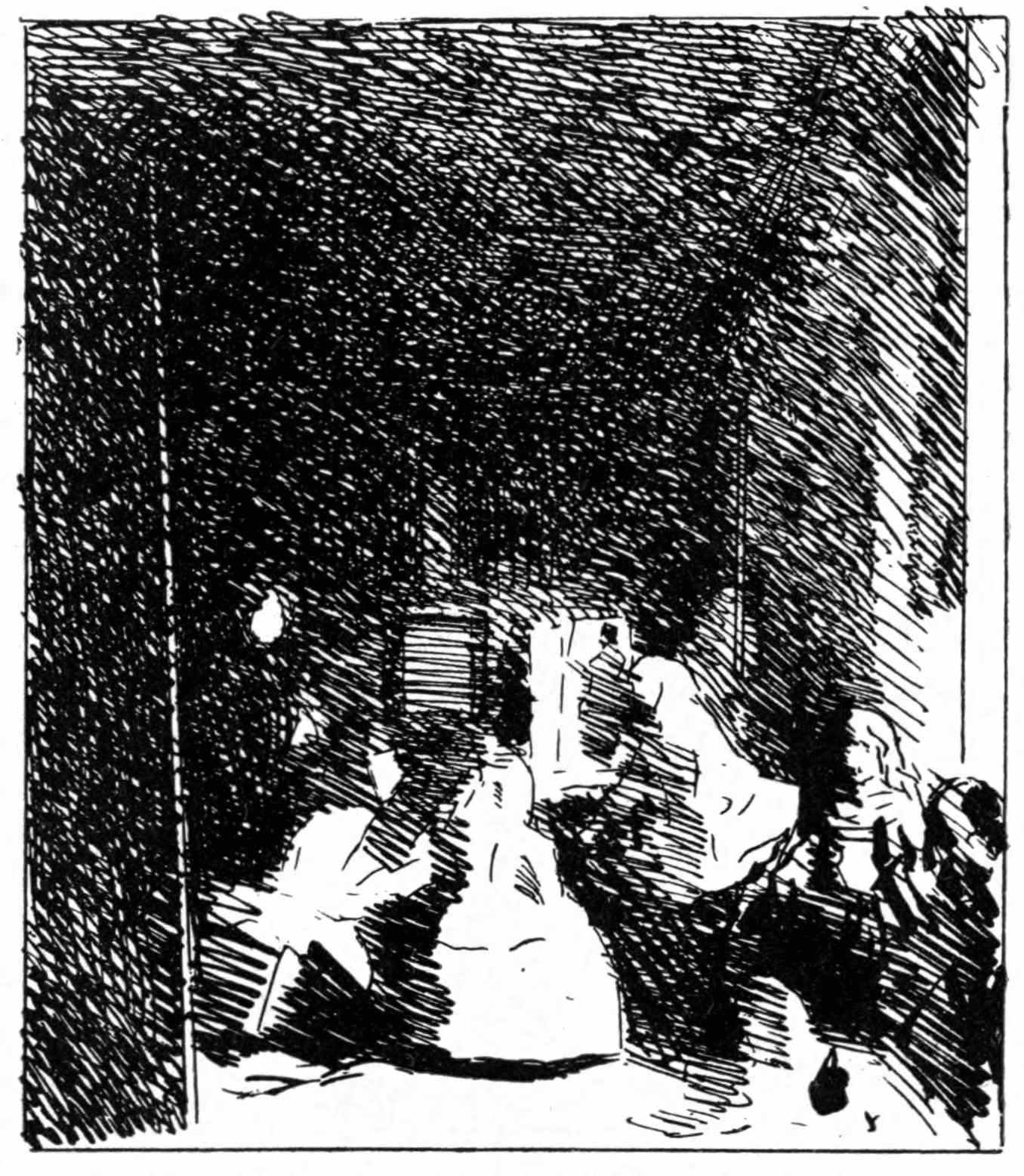

| Diagram of Composition | Velasquez | 33 | |

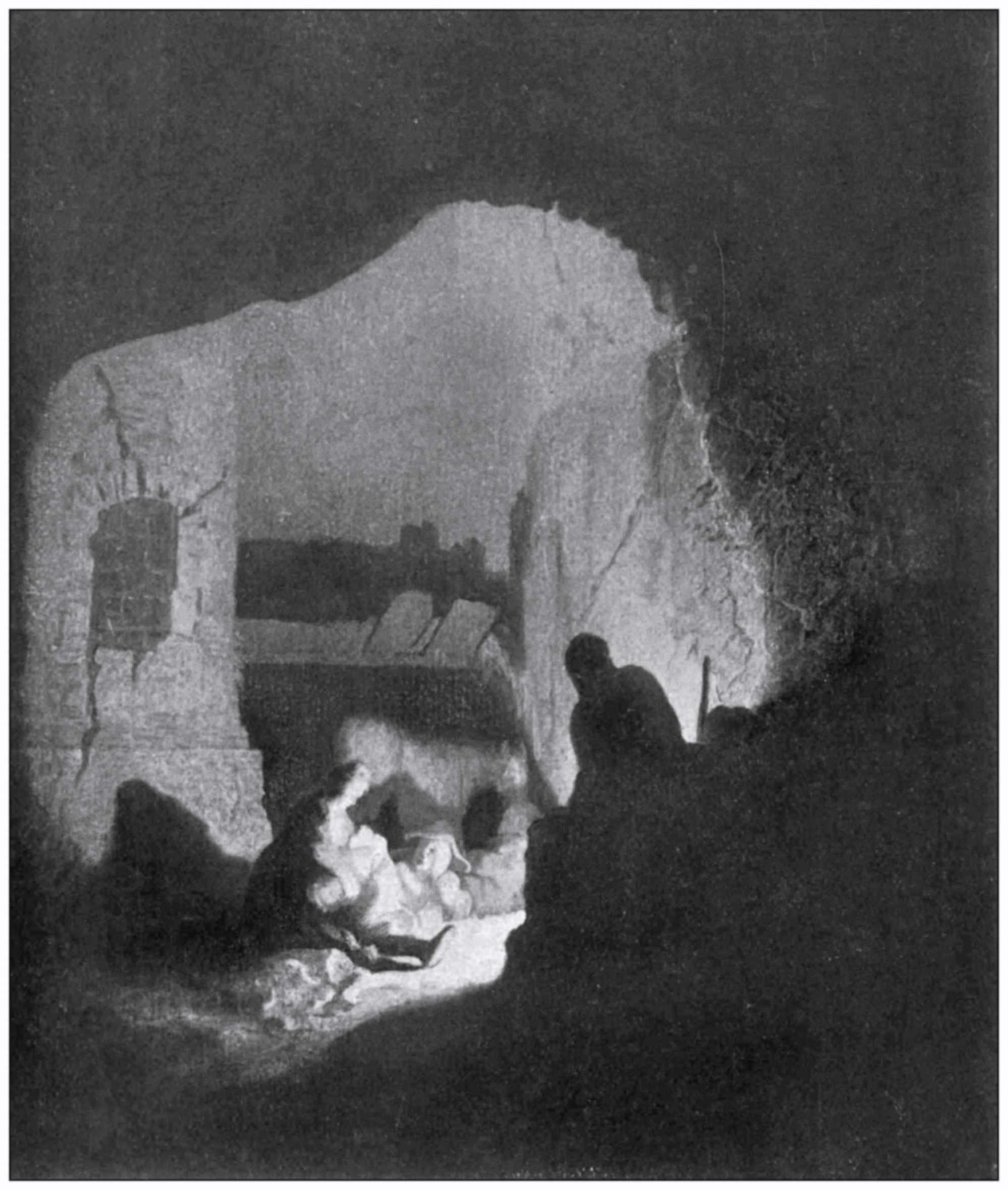

| The Repose in Egypt | Rembrandt | 39 | |

| The Entombment | Titian | 72 | |

| The Surrender of Breda | Velasquez | 79 | |

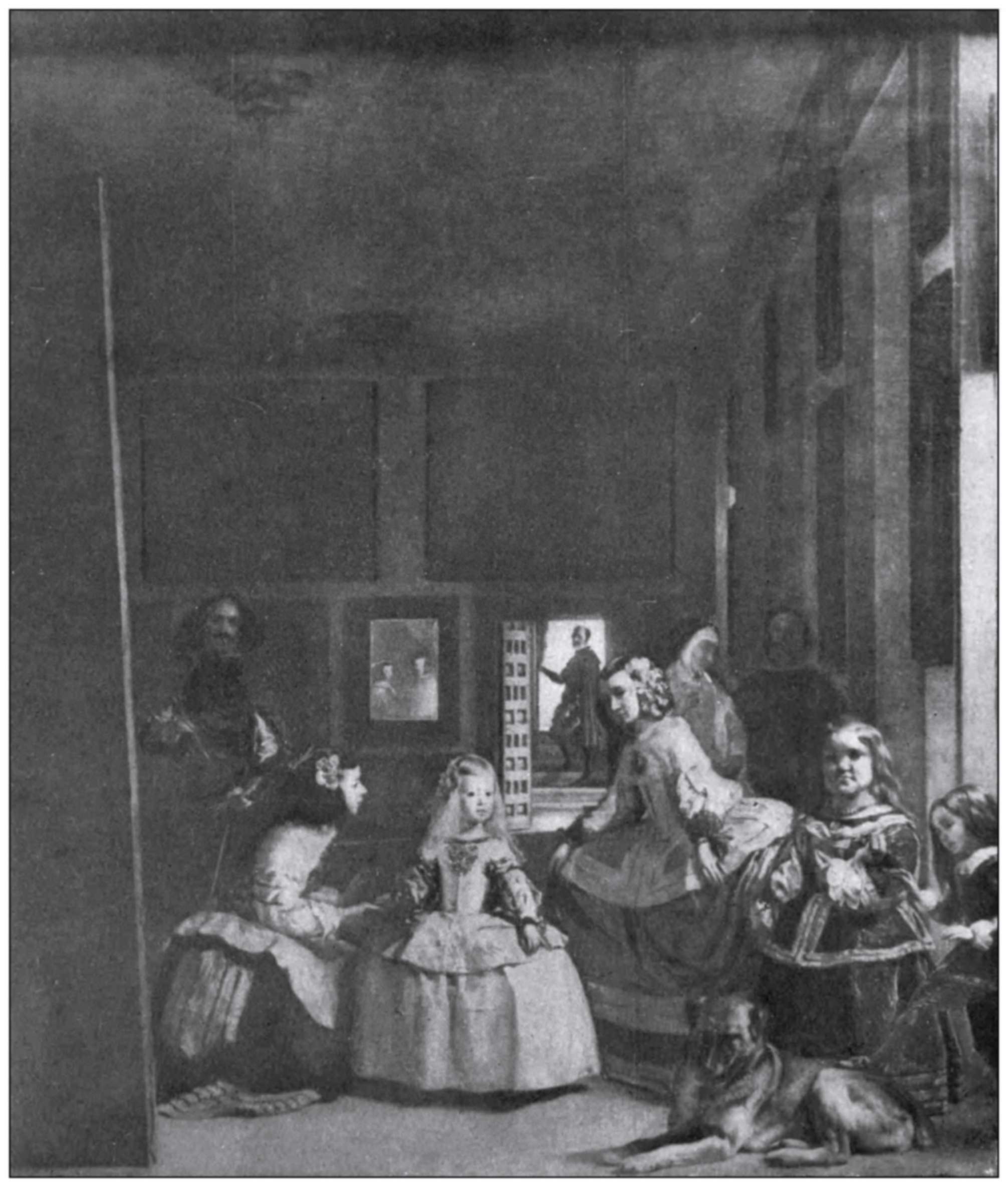

| Las Meniñas | Velasquez | 80 | |

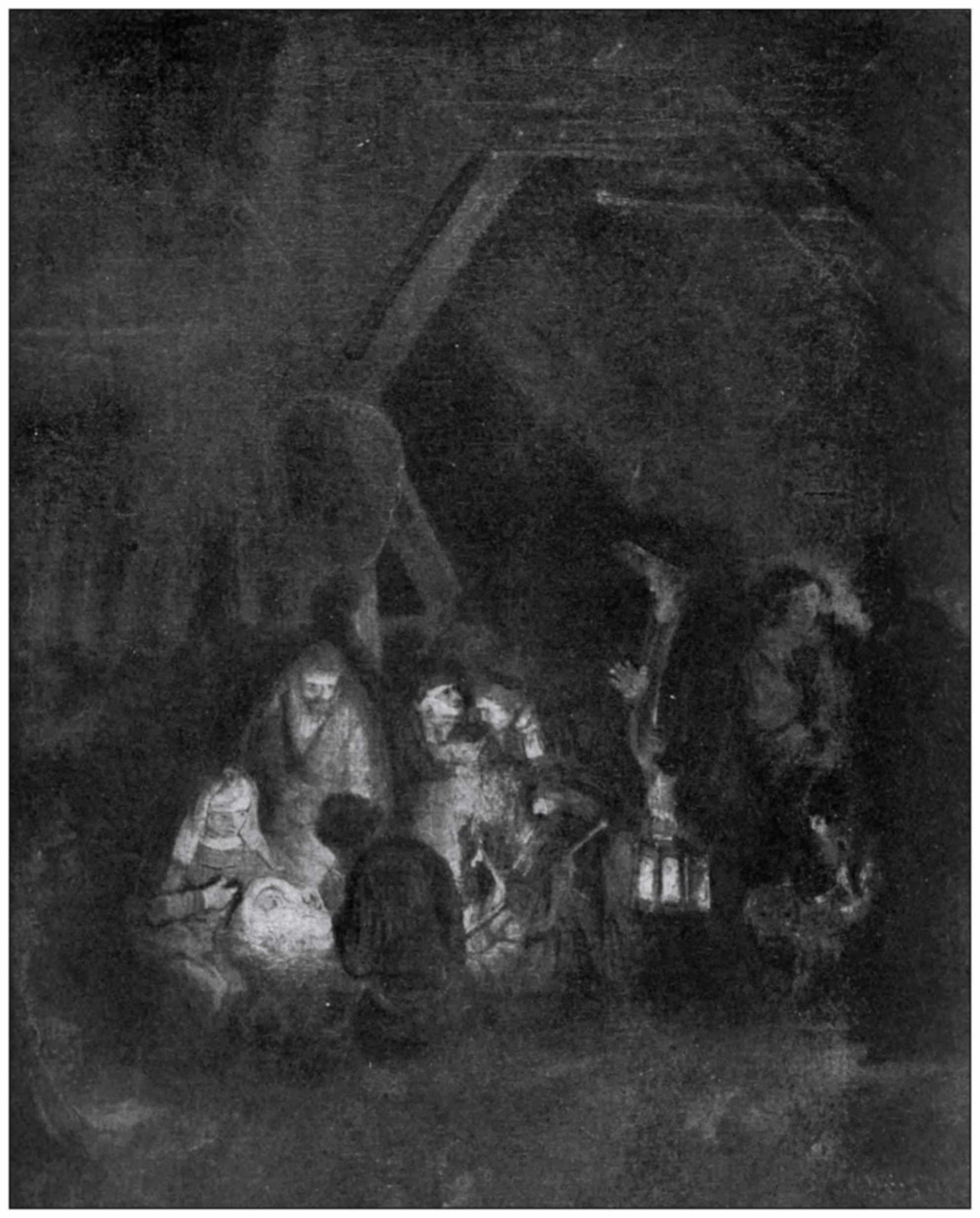

| The Adoration of the Shepherds | Rembrandt | 83 | |

| Joseph consoling the Prisoners | Rembrandt | 84 | |

| Zacharias and the Angel | Rembrandt | 86 | |

| The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba | Claude | 98 | |

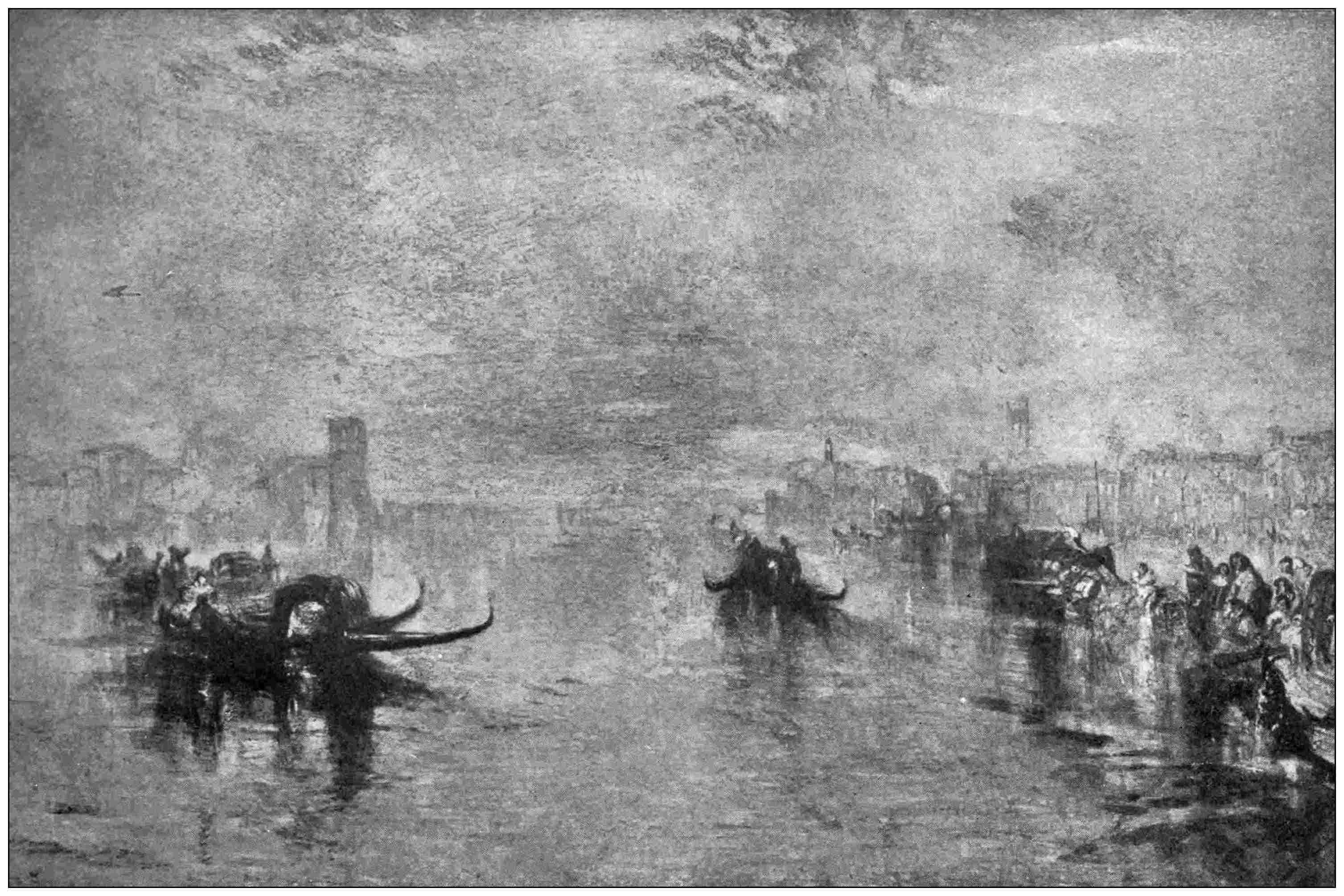

| Approach to Venice | Turner | 99 | |

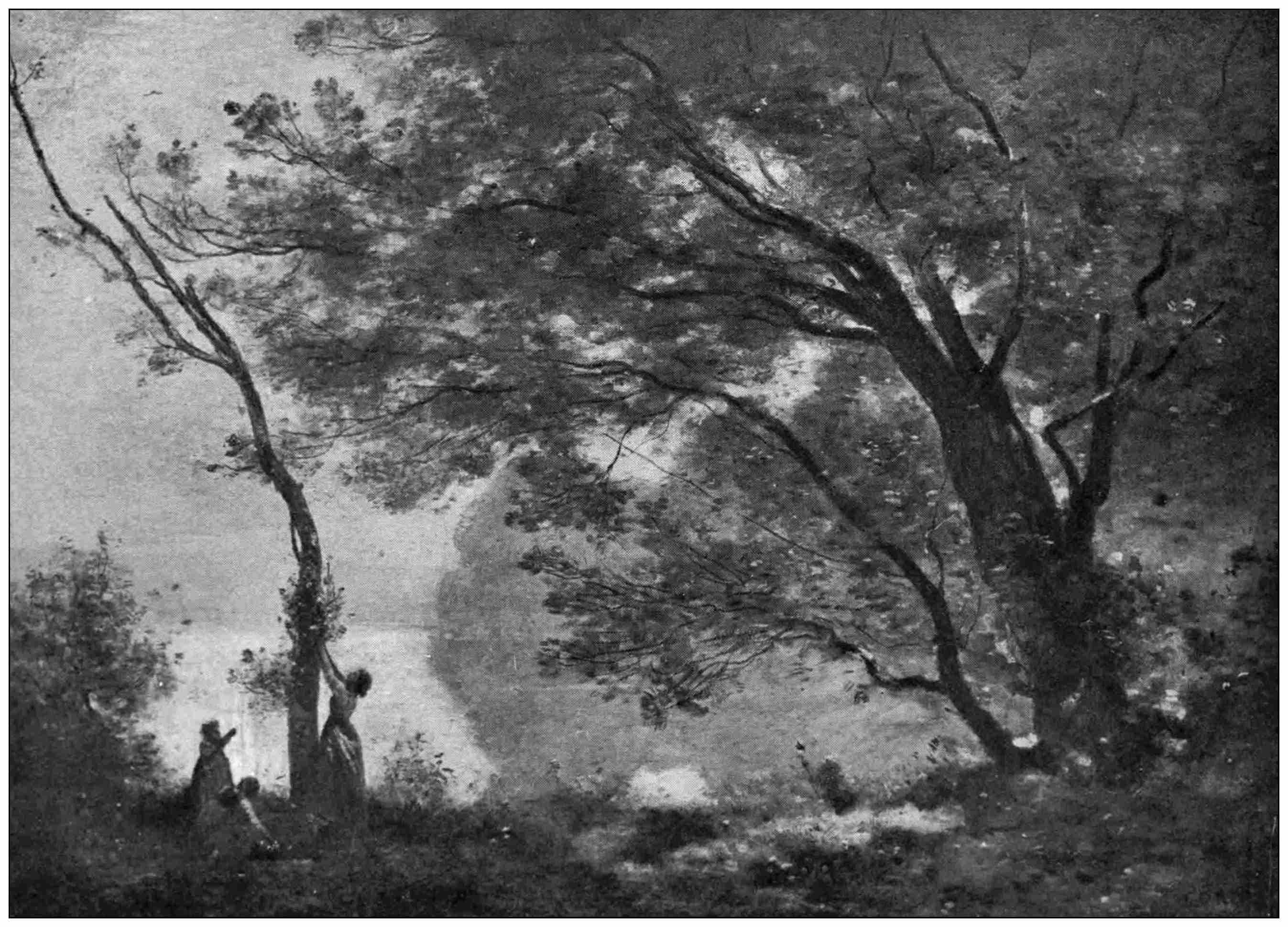

| Souvenir de Morte-Fontaine | Corot | 102 | |

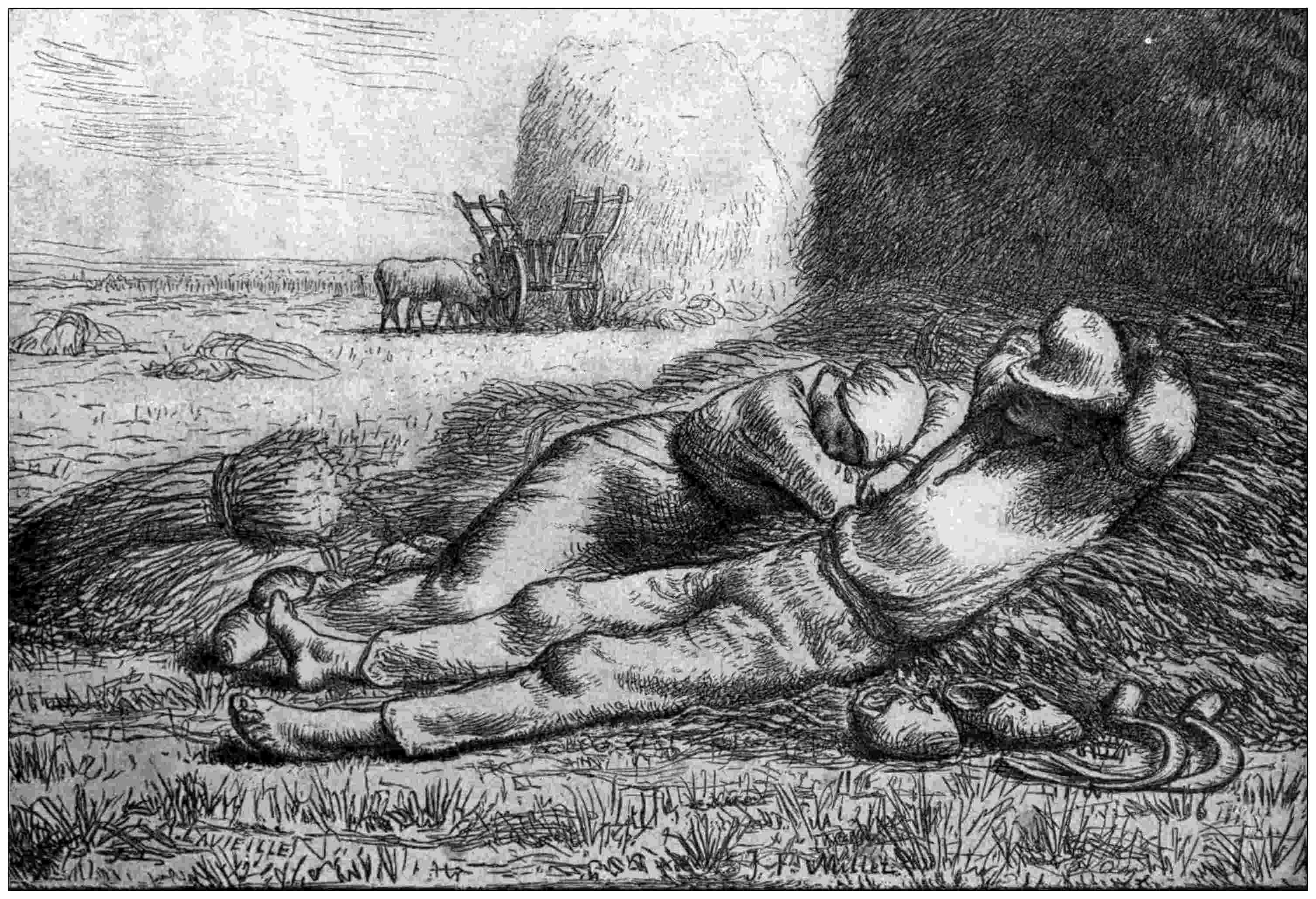

| Noon | J. F. Millet | 106 | |

| Les Foins | J. Bastien Lepage | 108 | |

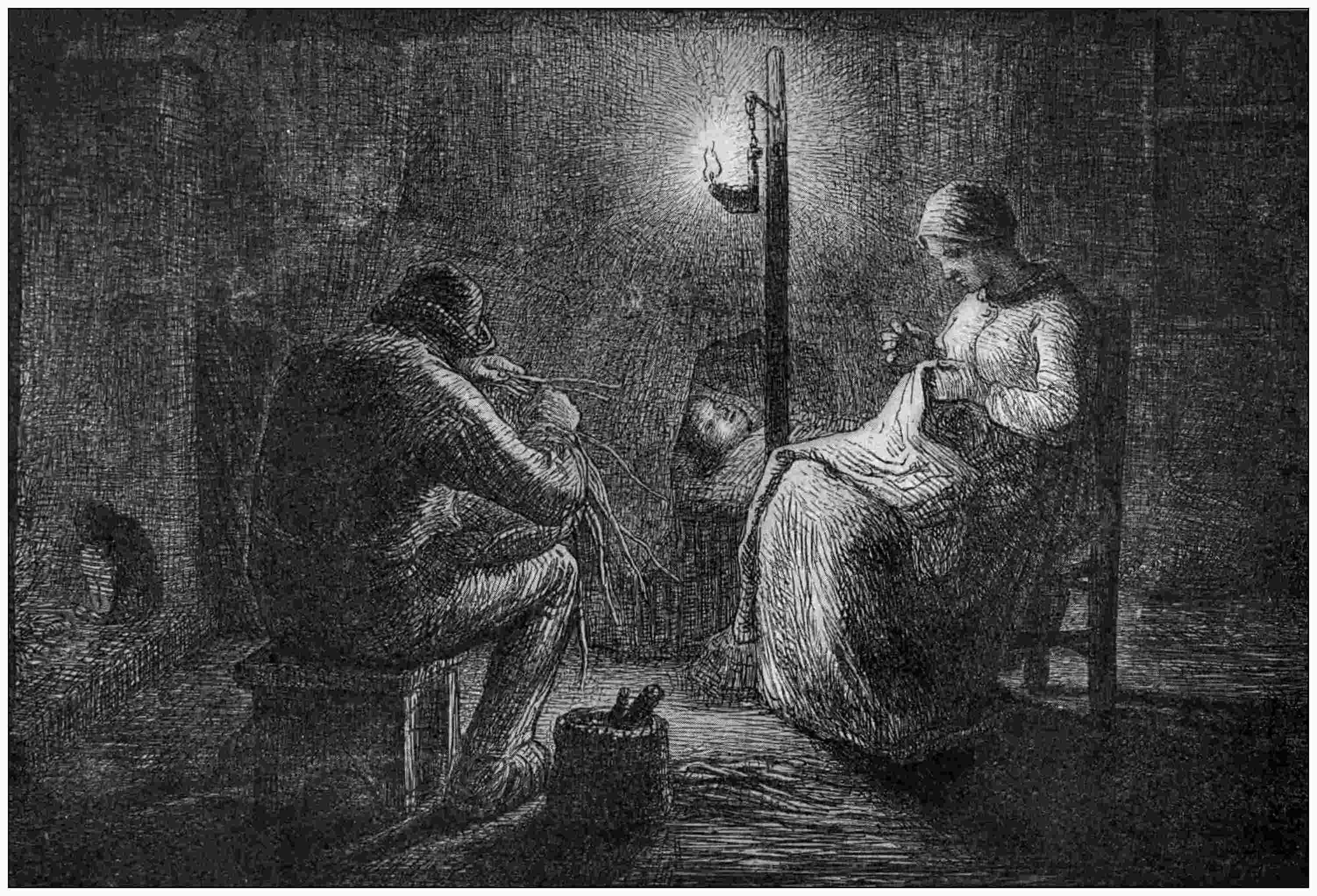

| Night | J. F. Millet | 109 | |

[vii]

NOTE

These Lectures are not printed exactly as they were delivered; in preparing them for publication, some slight alterations in their form have been made.

G. C.

[3]

So much has been achieved in painting, so much is to be learnt, that no artist, occupied as he must be with his own work, can have the necessary detachment of mind and the leisure to review impartially, and with proper appreciation, the history and practice of painting to the present day. The field is too wide. At most, he can give such rough conclusions as his own work, and the study of others’ work, has led him to form.

In the time of Sir Joshua Reynolds and for long after, hardly a painter earlier than Raphael was considered seriously; but now, and speaking roughly, since the days of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, which did so much for our art, we have learnt to know and to appreciate the great work of the earlier painters.

[4]

I think we may consider that extraordinary genius, William Blake, who was once a student of these schools, to be the real forerunner of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Writing in 1809, he draws attention to the clearness and beauty of the early Italian pictures, praising their precision and hardness, which he contrasts with the art of Rubens, Titian, and Rembrandt, whom he calls smudgers, blunderers, and daubers.

At about the same time, too, as the Pre-Raphaelite movement came the invention of photography, which has, I think, exercised a disturbing influence on our art; and a little later the art of the Japanese became known among us. So many theories are in the air to-day, so many courses are open to us, that it is more than ever difficult for the student to find his way; and though, knowing my own shortcomings, I feel strongly my inadequacy, I will do my best to give you such help as, were I a student in your place, I should wish to receive.

I imagine the intention of the Royal Academy in establishing this Chair was to supplement the teaching of the schools—the life class, which is a[5] training of the hand and eye, the tools of the artist, so to speak—with some direction of the mind also, so that the student should be not only equipped with sound technical skill, but be put on the track of some direction, or at least given indications, which would help him to decide how he should apply his skill when he goes out into the world. For the artist’s education does not finish in the life class; it begins there.

In the old days, when there was the constant relation of pupil to master, theory and practice went hand in hand. The training was thorough, the best obtainable, but limited. An artist knew at most what a few others were doing round about him, and was, as a rule, content to develop himself on the lines of the traditions and with the instruction he had received. And so arose the “schools” of one place and another.

But to-day we are at once worse off and better. We have lost all tradition—almost the tradition of fine workmanship. With the exception of the Pre-Raphaelite painters, no moderns have attained the wonderful, almost miraculous, perfection[6] and delicacy of execution which we find in the best old paintings—not achieved once or twice only, but steadily and consistently for a long period. But we are better off in that we have before us, brought into the open light of discussion and criticism, the whole practice of painting, for our admiration and guidance—and confusion; for our wider knowledge has brought uncertainty, and every man is a law unto himself. We are also under the disadvantage—if it is a disadvantage—of there being practically no direct commands for pictures, such as the Church or the great patron furnished in former days, which allowed the artist full liberty of expression under the restraint of a given idea.

We have long been without this; in fact, the varied developments of painting in the last century are owing to the freedom which artists enjoy, or I might say to the necessity which every artist feels himself under, to express his own feeling; and this accounts for the somewhat chaotic and confused impression which our big exhibitions produce, as a whole, in spite of so much excellent work.

[7]

Portraiture, which is vigorous and flourishing, and wall decoration, in which, thanks to the initiative of the late Lord Leighton, some essays are being made, are the only branches of our art that rest on the simple basis of direct demands. It is to be hoped that those who have the power will do all that is possible in the direction of encouraging fine decorative painting; for the conditions of decorative work are such as necessarily to develop the best faculties of the artist and the finest qualities of painting.

But I don’t want to paint my picture too black, or to imply that our painting is in decadence, for I think it is advancing; and although we live in times when everything is in the melting-pot, including the Fine Arts, we know that the instinct for beauty, and for its expression in the Fine Arts, is as natural and as necessary to our being as any other of our instincts, and that the cry of decadence is as old as the world itself. There is a comforting little story told by Lanzi in his book on Italian painting, of Orcagna the Florentine artist, who was living somewhere about 1320, at the very beginning of Florentine art. He gives[8] it on the authority of a contemporary writer, Sacchetti, that one day Orcagna proposed as a question, Who was the greatest master, setting Giotto out of the question? Some answered Cimabue, some Stephano, some Bernardo, and some Buffalmacco. Taddeo Gaddi, who was in the company, said: “Truly these were very able painters, but the art is decaying every day.” And I think that Michelangelo said that in his time the arts were not much considered. So we may conclude that the relation of the artist to the world in general was always much the same as it is now. As in other departments of human activity, painters have done well or ill, as it has been given them to do; succeeding generations of artists have cherished their memories, or have forgotten them, according to the estimation in which they held their work.

And so, when we find ourselves in the presence of great works of the past—in the presence, one might say, of the thought of great men made visible to us, it is well that we should put aside, as far as we can, our own preoccupations and theories, and try and read their thought, and see how far[9] we can gain from them confirmation, strength, and support for ourselves.

For one result of the wider appreciation of the older men is that our own work is brought sharply up against them; and when we find that a work of our own time may lose its freshness and interest in a few years, while the older works still hold us with an increasing charm, must we not see that we may have something to unlearn as well as to learn? There is no doubt that greater knowledge only serves to confirm and to extend our admiration for the work of the past, and this must lead every thoughtful student to question much that is practised to-day. We should try to reach some firm ground, some fixed principles that we can hold in common with the old painters.

I wish to direct your attention to-day to some of the Early Italian painters, but I do not propose to take you systematically through the history of any of the different schools. Some knowledge of the kind is very necessary, and no doubt in early days it was the duty of the painting professor to give this instruction. But we must remember that in those days communication between[10] nations was difficult. There were no national collections, and there was little or no literature on artistic subjects generally available; while to-day we have readily accessible to us, not only—thanks to the Royal Academy—our Old Masters Exhibitions, but an enormous and admirable body of literature, covering the whole field of painting, which, as I have reminded you, is now very fully explored. Indeed, I almost think that too much attention is given nowadays to the minutiæ of criticism; but still, we should be very grateful to those writers whose learning and patient enthusiasm are devoted to the service of our art, who have done so well a necessary work, which practising painters could never be expected to do. It is a hopeful sign of the interest taken in the Fine Arts to-day that it is not only possible, but profitable, to produce such works, and I earnestly recommend you to make as much use of them as you can.

But I should advise you not to go to work systematically, and to take it as a task; not to grind through the different schools, and then thank goodness you’ve done with it; not to puzzle yourselves[11] too much in trying to reconcile contradictory excellences, for things will make themselves clear to you as you go on. I should recommend you to go through a picture-gallery as one seeking the face of a friend in a crowd, and to let yourselves be led on by your sympathies. If you admire the work of a man, find out all you can about him; see his work as much as you can, especially his beginnings,—always look out for beginnings,—and try to get at his drawings and studies, which you can readily see either in photographs in your library, or in the Print Room at the British Museum, where there is a magnificent collection of original drawings. So I must leave the detailed study of the Old Masters to your own goodwill.

But there are problems in painting—the main points of pictures—which appeal only or mainly to artists, and on this ground I hope that my remarks may be of some service to you.

Painting, as we know it, may be said to begin with the Early Italians, for but little remains of the painting of the ancients, and we have no example of their finest work, though we may[12] infer, from the merit of such works as the Græco-Egyptian mummy-portraits of the second century A.D.—ordinary journeyman painters’ work, no doubt, and of no pretension—that the ancients were as great in their painting as in their sculpture. There are several of these portraits in the National Gallery. But, for us, the Italian Primitives are the starting-point. We do not perhaps realise how great were the earliest men of all—Giotto and the other inventors, the men who took the first steps forward, who discovered perspective and foreshortening, realising not only length and breadth, but depth in their pictures, and giving nature in its three dimensions—the men who first expressed form by the use of shadow. Although these things are commonplaces to us, we can still learn much from the study of the early men; but I do not propose now to do more than touch on the work of two early painters—not of the earliest time, but still of the beginning—Fra Angelico and Masaccio, an idealist and a realist. They both lived in Florence (Angelico from 1387 to 1455, Masaccio from 1401 to 1446), and rank among the great artists of the world.

[13]

Angelico painted in Florence, in Orvieto, and in Rome. There are a number of his frescoes in the monastery of St. Mark, in Florence, little pictures on the walls of the cells and passages. They are remarkable, apart from the directness and simplicity of their execution, for their deep religious feeling. It seems as if Angelico must have had a distinct vision of the scene he was painting in his mind, for his paintings convey to us the feeling or sentiment of his subject more strongly than anything else. We are not concerned with the people of his pictures as individuals, nor with their dresses, or the general setting of the scene, except so far as it serves to express the subject. And it is, I think, because of his preoccupation with the subject that his execution is so straightforward and expressive. There is no cleverness, but he does just what he wishes to do, with beautiful and expressive drawing and very simple, clear colour. The sentiment of his landscape is, like that of all the early painters, very serene; like the clear light before sunrise in summer.

There is no trace of posing in his figures; they[14] have an unstudied grace, and there is even in their movements something of the little awkwardnesses that we notice in the movements of children. And, though they are very human and touching, there is something about them different from ordinary people—something remote and apart from the world. They seem to exist for the picture only, and to have had no past history, no experience of life.

His pictures affect one as do things seen in a dream, and we accept his visions without questioning details which, if they were not somehow wrapped in his sentiment, would make us smile at their childishness. The little arcade under which the Virgin sits, in the picture of the Annunciation (one of the most beautiful of his works), is so low that she could hardly stand upright in it; but it does not matter, nor do the little toy trees and towns and towers that we find in his pictures. They are symbols only, and we do not question their details; nor are we conscious, in Angelico’s work, of the model as an individual.

But in the work of Masaccio we are conscious of the individual models throughout, and of the[15] interest of portraiture. He was one of the first, if not the first, to get beyond the early conventions of drawing and of light and shade, and to understand drawing in the sense in which it is understood to-day. We can see this in his frescoes in the Church of the Carmine, in Florence. The figures of Adam and Eve, for example, are drawn with an accuracy and truth to nature—to the nature of his models—which is convincing. And there is a portrait of an old man by him, in the Uffizi, drawn with the most absolute assurance and accomplishment. The modelling is so close and true that a sculptor could model a bust from it. This portrait is, like the paintings in the chapel, executed in fresco; and, as we know, this means that the work must be done rapidly, and with certainty, as no alterations are possible. It seems to me that these works of Masaccio are as well done as they could possibly be.

These frescoes of his in the church were felt to be so far in advance of anything till then done, that they became the school and pattern for all the young Florentine artists, and Masaccio’s chapel is one of the starting-points of the Renaissance.[16] Raphael and Michelangelo both studied there, and one may trace there the origin of the composition of some of Raphael’s cartoons, and even some of his figures, as the St. Paul, are taken bodily from these frescoes. Masaccio’s work shows interest in expression of form and character rather than in sentiment. One can imagine that one kind of subject would come as readily to him as another, but one cannot imagine Angelico painting anything but his own visions.

What is the charm of the early artist’s work—a charm which fuller knowledge only strengthens—in those who have once felt it? It is, I think, partly owing to the impression which these pictures give us of a simpler state of life. We see good, honest, simple souls taking part, without excitement or surprise, in miraculous events. We feel with perhaps a little touch of envy that man was a little nearer to the angels than he is to-day; it is very doubtful if he actually was, but that is the impression. Then there is their great charm as paintings: their wonderful simplicity, and untroubled ease of execution. We never can admire too much the delicate, clear[17] lighting, and it is doubtful if in any later work, with all our added knowledge, the sense of tranquil daylight—not the illusion of daylight—is given as well as in these early works. There are no cast shadows—when painters began to see shadows their troubles began—to take our attention from the sensitive, firm, and expressive lines of their drawing. How beautiful is their broad, simple modelling, and their masses of fine colour and beautiful plain spaces, enhancing little passages of extreme richness! One can go again and again to them with increasing wonder and delight. And when we come to the later generation—to the painters who were living just before the year 1500—we reach a period that to me is the most interesting and beautiful of Italian painting, although its highest development was yet to come. But think of the men then working! Da Vinci, Botticelli, Pollajuolo, Piero di Cosimo, Pinturicchio, Signorelli, Mantegna, Bellini, Crivelli, and a host of others.

The technical perfection of the early work is one of its great beauties. Much of it was in fresco, which from its conditions requires—to[18] take one quality alone—very fine draughtsmanship. And in tempera painting, which was employed for panels and small work, the same preliminary planning as in fresco had to be gone through, although it was, I believe, possible—I have had no practical experience of tempera painting—to work more than once over the same surface. But, as a rule, and as we can see by studying these works, the colour was put on sweetly and quickly, and the draperies were painted, often with one plain tint of colour over a preparatory monochrome, and this accounts for the beautiful quality of the paint; for we know that when the colour is put down clearly and untouched, it is fresh and untroubled.

Until the time of Masaccio, no attempt was made to gain richness or relief by the opposition of light to dark. All was in an even light, and richness was obtained by the local colours of draperies, ground, sky, etc. It is a style of painting admirably suited to the decoration of buildings, because of its clearness and formality.

But I think that the older painters’ ideal was always the representation of nature—even, if[19] possible, to the point of imitation or illusion; and we know that the invention of oil painting was welcomed as giving, in this direction, a greater range to the artist. And yet one may feel that the unconscious and naïve representation of nature by the older men was better—in that it was truer to the spirit of nature—than the self-conscious imitative work of later times.

I should like to touch on the question of the picture as a decoration; in our times a distinction is made between painting which is decorative and painting which is pictorial, which is, I think, an unfortunate distinction, and one which should not exist: for all pictures should decorate the walls or places on which they are placed. That this distinction should exist is perhaps our own fault, in forgetting, as we do sometimes, that a picture should be agreeable to the eye in its colours and masses; the good old painters never forgot that. And a picture that has only cleverness of execution, or interest of anecdote, will soon cease to charm; while a picture may be feeble, and even childish, in its execution, yet[20] if its masses and colours are well arranged, it will always give pleasure to the eye.

But I do not think it is possible to draw the line, and say at what point of imitation or of realism a picture ceases to be decorative and becomes pictorial; for when a picture was painted on a wall, it was intended to bring the scene into the presence, if possible, of the spectators in the room.

In the House of Livia, among the ruins on the Palatine Hill, are some rooms with the painted decorations still on the walls. One room is painted with architectural openings in the walls, through which we see landscapes and figures, the intention being to give the idea of space outside.

And there are many other instances to be seen, especially in Italian churches, where we find paintings in which the real architectural features of the building are imitated in paint, and continued into the picture, to make a scene for it, as in the small refectory of the monastery of St. Mark in Florence. This is a vaulted room. At one end is a painting of the Last Supper,[21] by Ghirlandajo. A bay of the vaulting is continued in perspective into the painting, and the colour of the vaulting is matched, so as to suggest that the scene passes in our presence. The same device is employed by Leonardo in his Last Supper. And the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is planned in this way. Michelangelo has joined painted mouldings to real ones,—one cannot tell where,—and has built up in paint from them a great structural framework into the ceiling, and on this he has placed his figures.

And we see the same plan carried on until, in later times, it falls into the worst possible taste, as in those decorations where a ceiling will be covered with painted flying figures, with the leg of the nearest one actually modelled in relief, and projecting over the enclosing moulding! And the lamentable part of it is that it is very skilfully done.

We can, I think, draw a little generalisation from this. It seems as if in the artist’s mind the desire to express his subject and the desire to display his skill are conflicting tendencies. When these are in perfect balance we get the[22] finest work. When the desire for expression is the stronger, we get sincere and beautiful, but imperfect and immature work, as in the case of the early Primitives. But when the desire for the display of skill is the stronger, we get cleverness, affectation, and decadence.

[25]

The difficulties encountered in painting a picture lie, not so much in the actual painting of each portion of the work (though this is full of difficulties) as in the control of the whole canvas, in determining what part of the picture is to be given prominence, and in what way this is to be attained.

To draw a figure, to paint a head, a piece of drapery, a sky, a tree—this we can all do to some extent if we have the actual object before us; but as it is not in the nature of things that a group or a scene—even if we are so fortunate as to see it once so arranged as to make us wish to paint it—can be reconstituted every time we get to work on our picture, we must learn to retain its main points, or get some general design—some image in our minds of[26] what we want to accomplish, before we begin our work.

The wonderful range which is possible, and which has been attained in painting, has been attained by the study and analysis, not only of nature, but of the way in which things are shown to us in nature by light and shade, by warm and cold colour. These are the simple elements of every picture (drawing, of course, included). It is the appearance of nature that has to be observed and analysed, the object being to present or suggest an illusion. The painter studies, not facts, but appearances, being helped in the direction of his vision by the works of those who have gone before him.

As I have already pointed out, the aim of the early artists was to imitate nature; and although they had not then learned to give by light and shade the illusion of nature, their fine taste led them to produce great work by other means. They were—the best of them—very true to nature in drawing, in strong characterisation, and very expressive in sentiment. Their decorative sense and imagination were not held in restraint[27] by the necessity of being literally true throughout, and their works, though in them the actual force of lighting in nature was not attained, often not even attempted, yet have, in other ways, a beauty and charm as great as any later works possess.

We will follow a little the development of painting towards realism. This is, of course, only a partial view, but there is some interest in following it. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), in his treatise on painting, says that “the first object of a painter is to make a simple, flat surface appear like a relievo, and some of its parts detached from the ground. He who excels all others in that part of the art deserves the greatest praise. This perfection of the art depends on the correct distribution of lights and shades. If the painter, then, avoids shadows, he may be said to avoid the glory of the art, and to render his work despicable to real connoisseurs, for the sake of acquiring the esteem of vulgar and ignorant admirers of fine colours, who never have any knowledge of relievo.” I think Leonardo was a little too hard on the Primitives; he does not seem to appreciate their[28] beauty. He was the first to record, if not the first to practise, the study of light and shadow as we understand it now. For we see also in the work of a contemporary, Melozzo da Forli (1438-1494) the study of light and shade in nature; there are two of his pictures in the National Gallery—“Music” and “Rhetoric.” Those of you who do not know Leonardo’s treatise on painting would do well to read it. It is full of wisdom and fresh observation. His clear intelligence raises problems, many of which painters still discuss. I will read a few extracts. He says on “gradation”: “What is fine is not always beautiful or good. I address this to such painters as are so attached to the beauty of colours that they regret being obliged to give them almost imperceptible shadows, not considering the beautiful relief which figures acquire by a proper gradation and strength of shadow.” Again: “Do not make the boundaries of your figures of any other colour than that of the background on which they are placed; that is, avoid making dark outlines. The boundaries which separate one body from another are of the nature of mathematical lines,[29] not of real lines. The end of any colour is only the beginning of another; and it ought not to be called a line, for nothing interposes between them except the termination of the one against the other, which, being nothing in itself, cannot be perceivable.” Again: “Those shadows which in nature are undetermined, and the extremities of which are hardly to be perceived, are to be copied in your painting in the same manner, never to be precisely finished, but left confused or blended. This apparent neglect will show great judgment, and will be the ingenious result of your observation of nature.” Again he says: “It is a great error in some painters who draw a figure at home by any particular light, and afterwards make use of that drawing in a picture representing an open country, which receives the general light of the sky, where the surrounding air gives light on all sides. This painter would put dark shadows where nature would put none at all, or, if any, so faint as to be almost imperceptible; or he would throw reflected lights where it is impossible there should be any.”

He recommends the painter to compare his[30] own work with nature in a small mirror, “which,” says he, “being your master, will show you the lights and shadows of any object whatever.” And, indeed, all through the book we get constant reference to nature. “If you do not rest on the good foundation of nature, you will labour with little honour and less profit.” “Whoever flatters himself that his memory can retain all the effects of nature is deceived, for our memory is not so capricious. Therefore, consult nature for everything.”

These words were written four hundred years ago; they might have been written to-day. One feels how very modern he was in spirit. It is, of course, a question what he means by “nature”—whether that ideal which Sir Joshua Reynolds called the general idea of nature, or nature in its variety and imperfection as we see it. I think Leonardo meant the latter, in the sense that the persons in a picture should look what they profess to be—not, of course, in the sense that he would take the first woman he met as model for a Madonna. There, where he had to represent the highest type of woman, he chose the most beautiful[31] person he could, as we see in “The Virgin of the Rocks” in the National Gallery.

There is a passage of his on lighting that seems to bear on this picture: “The light admitted in front of heads situated opposite side-walls which are dark will cause them to have great relievo, particularly if the light be placed high. And the reason is that the most prominent parts of these faces are illumined by the general light striking them in front, which light produces very faint shadows on the part where it strikes; but as it turns toward the sides it begins to participate of the dark shadows of the room, which grow darker in proportion as it sinks with them.

“Besides, when the light comes from on high, it does not strike on every part of the face alike, but one part produces great shadows on another, as the eyebrows, which deprive the whole sockets of the eyes of light. The nose keeps it off from a great part of the mouth, and the chin from the neck, and such other parts. This, by concentrating the light upon the most projecting parts, produces a very great relief.”

I have given these passages from Leonardo to[32] show that we are justified by tradition and good precedent in examining nature as closely as we can.

The effect of light colours in a picture is the same as that of actual light in nature—to attract the eye. Therefore painters have naturally always striven to give that object to which they wish first to direct attention the greatest light. There is an old precept that there should never be two principal lights in a picture. It means that the spectator’s attention should not be distracted.

Now, if a scene is represented as taking place in a room, it is possible, by arrangement of objects, to bring the principal things into prominence naturally and with most beautiful effect, as in the “Maids of Honour,” by Velasquez. I am sorry to say I have not had the privilege of seeing this picture, but only the sketch, which was in the Old Masters Exhibition a year or two ago; but the picture is, I should think, the greatest achievement in painting of true ordinary lighting in the world. There is no doubt that the effect in this picture is exactly as in the room; everything is[33] accounted for naturally. It is worth remarking how the picture is arranged—divided diagonally into light and dark, with a strong dark on the light side, and a little light taken into the dark. This is a very effective arrangement, and a very natural one. Pictures arrange themselves that way unconsciously, or perhaps the eye finds something agreeable in this arrangement—in its interchange. It is common in landscape, as in the picture by Corot in the Louvre; and Whistler’s portraits of his mother, and of Carlyle, are arranged in the same kind of pattern.

In connection with the arrangement of a picture, it is worth while inquiring why it is that principal masses or objects, although they should be placed near the centre of the picture, should not be placed exactly in the centre, or why any absolutely symmetrical arrangements are unpleasant to the eye, and should be avoided. I think it may be a purely physical reason, connected with the fatigue experienced by the eye in looking at regular forms and spaces, and that this may also account for the fact that such things as the true surfaces of machinery, and the straight lines or[34] monotonous regularity of buildings, fail to charm the eye; while unexpected variety of form does, as we see in old buildings, ruins, mountains, and generally in all that is called picturesque.

If a scene is represented as being in the open air, the difficulty arises that the light of the sky, being so great, will dominate everything, and, instead of the figure being the principal, the landscape interest will predominate, and the figure take the second place. It is not, however, always so. There are effects of light, such as when one is looking with the light at figures facing the sun—especially in evening light, or when there is a cloud behind them—when the figure receives most light, and tells beautifully. I think Titian studied and used this effect a great deal, and his picture “The Entombment,” in the Louvre, gives very finely the impression of that effect.

“The Surrender of Breda,” by Velasquez, is also arranged looking with the sunlight, and the group is built up and united by shadows from the figures, and from clouds on the figures in middle distance. The shadows tie the picture together.

It is possible to avoid the difficulty of the sky[35] by leaving it out, or by using a high horizon and showing very little; and when this is done, figures can be painted up to the strength and the lightness of nature, as in Bastien Lepage’s picture of “Les Foins” in the Luxembourg. But if much sky were added to this, the brightest light we could use would only look like paper, because the relative intensity of the light on figures and on sky would not be correct. It could be “managed”—if the middle and distance were painted dark, as in shadow—to have a larger sky; and the sky is so beautiful, and can be made to convey so much, that a picture gains if it can be used. And this compromise was used largely by the great Venetian painters, simply, I feel sure, through knowing well what effects are possible in nature.

For you will find, if you are in the habit of constantly observing nature, and on looking on all things as if they were or might be pictures, that such arrangements and variety of lighting of figures as one sees in Velasquez, in Rembrandt, in Titian, Veronese, Tintoret,—figures in shade against figures in full light, and all in the open air,—that these arrangements are strictly founded[36] on nature, and result from observation. On a windy day in summer, when clouds are passing, one constantly sees, but for a moment only, such effects—of figures in sunlight relieved against a deep background of shadow, or of near figures dark in the shadow of houses or trees, with others in the light beyond; one sees no end of beautiful things, but only for a moment. There is no time to do more than make a mental note, but they give one a clue which one may follow, and perhaps be so fortunate as to learn to develop—a clue to the fine scheme of lighting which these great artists have mastered and used.

We, in our work, lay too much stress on the superficial qualities, the imitative ones, and are unable to grasp these great generalisations. They won’t pose for us, but they wouldn’t pose for Velasquez or Titian either. Then we may feel when we look at great pictures such as I have mentioned, and such, for instance, as “The Marriage of Cana,” by Veronese, in the Louvre, how very great and thorough was the knowledge of the possibilities of light in nature which enabled them to plan and execute their great works. It[37] is told of Veronese that when someone objected to his putting some figures in shadow, and asked him why he did it, “A cloud is passing,” said he.

But it may often be against the intention of the painter to draw attention to the sky, and we find that some—especially portrait painters—have adopted the artifice of frankly painting the sky background darker than it would naturally be, as in the portrait of Lord Heathfield, by Reynolds, where he stands against an intense black background, which in a little while we realise is intended for the smoke of the cannon down on the left.

This is a frank convention. Now, don’t let us despise conventions, but try and understand them. All conventions rest on some truth. The convention may have grown so as to obscure the fundamental truth. Our conception of truth widens with our experience. The student’s is, as a rule, narrowed down to the particular one he happens to be struggling with. He is so much engrossed with the difficulty of imitation that he is apt to think this the main truth. But he should not confine his observation to the life[38] class, or to the time when he is actually painting. Let him try and notice, as one can, at all times, how things look at unpremeditated moments, and he will find as he becomes familiar with the great men’s work that they did so too. He will come upon their tracks.

It is well, then, when in a good picture we see some passage we think false or conventional, to try and understand the intention of the painter in using it. Almost always it will be found to have been adopted for the purpose of concentrating attention on the principal things. The painter, by his artifice, seeks to attract our attention, and so produce the same effect as, were we ourselves in presence of the scene, our consciousness would produce in us.

We may copy a scene as truly as we can with regard to values, and all the rest of it, and find, after all, that it does not give us the effect of the actual scene. The reason is that we copy with an eye looking equally and dispassionately on everything, as would the lens of a camera, forgetting the main thing—the human element of attention, or attraction to some particular part. A convention by which we would sacrifice subordinate[39] parts for the sake of accenting the essential is truer to the effect of nature. For all painting is a partial statement—a reading or rendering of nature—rather than an inventory. And the different temperaments of artists show in the particular qualities which each one feels most impelled to select; but the desire for literal truth is always in conflict with this, and every artist must make a compromise for himself.

There are two extremes in the way artists see light in nature. One is to half close the eyes. This takes away a certain quantity of light, joining all the darks together, and leaving the high lights as spots. This seems to have been the way of Rembrandt. He makes the whole picture lead up to his point of light. There is a little picture of his—a “Repose in Egypt”—in one of the German galleries, which shows very clearly his love of the beauty of light. The arrangement is typical of many pictures: a central mass of light, surrounded and led up to by dark. It is the common arrangement of portraits and still-life pictures; also of many of the old landscapes.

Turner, in his long career, began by seeing[40] nature in the same way as Rembrandt,—by concentrating on the light,—but he studied and assimilated Claude, and ended by surpassing him. In his picture of “The Shipwreck,” you will see the same arrangement of a central light surrounded by dark.

The other way of looking at nature is with the eyes wide open, as we see in Claude’s pictures, such as the “Queen of Sheba” in the National Gallery. In this picture the difference in value between the sun and adjoining sky is very slight; but if in nature we look at the sun only in such a position, we realise that it is impossible to get the difference in brightness between it and the sky. If we half close our eyes so that we can look at the sun, we find that we cannot see anything else. But if now we look with open eyes on the whole scene, we realise that not only the whole sky, but everything else, except the actual shadows, is governed by, and is part of the sun’s light. The shadows tell out as spots of colour. This is, it seems to me, the truer way of looking at nature, and I think Claude was the first to realise it.

[41]

Turner, in his later manner, painted in the same way, as we see in his “Approach to Venice,” where he has completely left his old manner of vision, and has realised the infinite gradations in light.

But this difference between the earlier and the later manner of Turner is one which is noticeable in every artist’s work. The tendency, with increased knowledge, is to broaden and to lighten. Rembrandt himself shows a difference between his earlier and later work. It is the growing perception of the beauty of light.

In connection with lighting, there is a point of comparison between the Flemish and the Italian work generally which is, I think, worth noticing—that is, that the Northern painters, as a rule, seem to have been more attracted to the surfaces and textures of things, and to have studied their models at a closer range than did the Italians. In some of Dürer’s portraits, for example, one can discern that the high light of the eye shows the panes of his studio window. And in the portraits of Holbein, too, we see that everything must have been studied at extremely close range.[42] That wonderful work, “The Ambassadors,” in the National Gallery, is all painted in a clear, even light with the utmost precision and minuteness, over every square inch of the panel, apparently without effort. It is beautiful in colour and harmonious, and at its distance everything seems in its place. Yet the figures do not quite hold the spectator, perhaps because they are placed so far away from the centre; partly, too, owing to the lack of atmosphere, which is almost inseparable from the close point of view necessitated by minute realisation. If we go from this picture to Velasquez’s “Admiral,” in the next room, we see the difference, for in this picture atmosphere is realised and detail suggested. It seems impossible to combine these different qualities—at anyrate, on a large scale, though it can be done on a small scale, as we see in the work of Van Eyck and some of the later Dutchmen.

Holbein’s “Duchess of Milan” is finer as a portrait than “The Ambassadors,” for there is nothing to distract the attention from the face. But one finds this difference in the way of seeing, all through the work of the Flemish and Italian[43] schools. It may be due, I think, partly to the tradition of the antique, which had never been entirely lost in Italy. And it may be due also partly to the difference of climate and light in the two countries. The clear air of Italy would enable things to be seen plainly at a greater distance than we can see them here. But I think the main reason is that the Italian artists were accustomed to design and paint large spaces, and that they studied their figures and groups at a distance sufficient for the eye to take in the whole group. At this distance, surfaces and smaller details of modelling would be lost, and only the broad structural features and masses of colour remain.

I have mentioned the disturbing influence of photography on painting. It is hardly necessary to recall that, until the invention of photography, there was only one way of seeing things—through the human eye. And all the fine things have been accomplished by men whose minds were trained to perception of beauty in nature through the eye. Now, as Leonardo pointed out, nature does not define everything,[44] and the triumph of painting has been that it has realised this, and presented things in degrees of emphasis corresponding to that in which they are presented to us in nature. But the minutely searching lens of the camera presents everything with indisputable accuracy, only not as we see it. How cruel and searching are the majority of portrait photographs! Yet the painter, for a time, tried to rival the camera in minuteness and detachment, forgetting that it is just this human quality of attention and selection that makes a painting a work of art. Photography itself now seems to admit the pictorial falseness of its own ideal, and we find photographers occupied to-day in arranging the tones and concentrating the lights of their pictures—in fact, using clumsily all the conventions discovered by the masters. But photographs, especially snapshots of nature, are most interesting and suggestive to look at. I do not think, though, that photography can in any other way be an aid to a painter. You cannot make that yours which the camera chooses to give you. You must make your own selection from nature.

[47]

One may say broadly that if drawing is the intellectual side of art—it is understood that I refer to the art of painting—colour is the emotional side. This is not a hard and fast distinction. It is impossible to make one where the two qualities are so intimately connected; but colour has an effect in echoing or waking our feelings that drawing alone has not. This is perhaps because colours themselves, even if placed in simple tints without definite form, suggest to us correspondences with the colours and effects of things in nature. Thus blue suggests the sky; white and yellow, light; red, fire or blood; green suggests the fields and trees; and dark colours the night. One feels this emotional correspondence with some aspect of nature, or something recognisable in nature, in every tint of the palette.

[48]

The rules of drawing are fairly definite, and we may claim to know what constitutes good and accurate drawing; but it is not at all easy to define in what good colouring consists. One cannot go further than say that it must be harmonious, and that it must convey the impression of truth to nature. One can tell bad colouring at once—that the colours are untrue or discordant; but the limits within which good colour is possible are as wide as the range of emotion or temperament in man. Any artist will paint things as he sees or feels them. If he has succeeded in expressing some truth or beauty, it will be recognised and felt by some among the many who will in time see his work.

Nothing in nature is actually the colour that we see it. It only appears to us at a given moment as a particular colour in relation to other apparent colours which surround it. Thus we may walk out on a rainy evening when the sky and everything is grey, and come indoors and light the lamp, and immediately the sky which we see through the window appears as a beautiful and tender blue, though there was no[49] trace of blue in the sky a minute before, when we were outside. The change is produced in our senses by the colour of the sky taking its place in relation to a range of warm colours in the lighted room. In the same way the presence of a man with a lantern, or a light in a window, will apparently change the colour of things in its neighbourhood, and a mass of any strong colour, such as red, blue, or orange, will suggest its complementary colour in surrounding objects. (There is a curious exception to this in the case of lilac or bright violet, which, instead of suggesting its complementary colour in surrounding things, appears to diffuse its own colour over them, so that we seem to see a suspicion of violet in all other neighbouring colours.)

We must realise, then, that each combination of colours we see presents and forms a problem of its own. I think this was a difficulty not present to the older painters, who—perhaps wisely—seem to have ruled out, or not troubled about, many subtleties that worry us.

The range of colour that we possess—from white to black—has been proved sufficient to[50] express the utmost range of colour or light in nature, from the sun itself in the sky to the deepest gloom. Yet our range of pigments is nothing like as wide as the range in nature from light to shadow. It is wide enough to enable us to paint, to the point of absolute illusion, an object receiving light in a room; but not with actual light added. For example, one might paint the portrait of a man, with a white shirtfront in full light, which would be white, or nearly so. But if he wore a diamond stud, the light from this—a reflection of the sky—would be much too bright for our colours. In such a case it would become necessary to sacrifice the stud, or to paint the man and the shirt down to it. It would become a question for the painter which thing he considered the most important, and in this way either a light or a dark version of the man might be true, and both might be equally beautiful, but on different grounds. One may imagine this difference of point of view between Millais and Whistler in their portraits. The same kind of question arises if we paint a landscape—whether to sacrifice the ground for[51] the sky, or the sky for the ground, or both for figures, if we introduce them; and the solution is the same—that the colour of the particular part one wishes to be the principal must determine the colour of the secondary things.

We can consider the tints of our palette to be like the notes on a keyboard, and, in looking at nature, try and resolve its appearances into a series of tints in some correspondence with what we know from experience our colours will produce. Thus, in looking at a scene, one would say: “The general tone of the whole is so-and-so—warm, or cold, or whatever it may be; the highest light is so-and-so, and the darkest dark is so-and-so,” and having made up our mind on the general aspect and limits of our problem, get to work on it in detail.

This is the ordinary way one would begin in studying from nature in colour. Now we go on. The scale of colour may be divided into warm and cold colours, and all colours we see in nature incline either to warm or cold—I am presuming we are making a study from nature—not only in themselves, but according to the degree[52] in which they are influenced by light. We shall, I think, never find light and shadow on an object equally warm or equally cool. This would be a monochrome, like an etching or an engraving, which suggests colour, but does not give it; and those engravings best suggest colour which are printed in black or neutral tints, and not in a positive colour, for our imagination supplies the colour if the gradations are right. But in ordinary daylight in a room the lights are cool, and the shadows are warm in colour. So, out of doors in warm sunshine, we get the lights warm and the shadows cool, even to the point of absolute blue or violet. This brings me to one of the difficulties of outdoor painting—the tendency, especially if sunlight be attempted, to paint in too cold a key, so that a study which, at the time we were engaged on it seemed absolutely true, should afterwards, when brought into the even light of a room, fail to give the impression of warmth that the original scene gave. We often see pictures of sunshine painted which give us no impression whatever of warmth.

I think the reason of this is that we do not[53] realise how warm the colour of the light is, being enveloped in it, perhaps even having it on our work—at anyrate, having our eyes filled with it. We are struck by the sharp contrast of the cool shadow, and paint that, it being obviously cool. But if we concede that the light is warm, we can get the opposition of the cool shadow, and get it to look blue, or almost so, even though as pigment it may be umber and white, or grey. A difficulty of the same kind is felt with regard to the blue of the sky, which, under some effects, appears as blue as one can possibly make it—bluer, even—and at the same time warm. We may pile on our brightest blue as much as we like, we cannot get it blue enough, and we cannot at the same time get it warm. Now, we know that the bright blues of our palette, when we look at them in a room, are bright enough to give the sense of any conceivable blue; so we may conclude that the fault does not lie in our paints, but in ourselves, as not knowing how to manage them, and that we must try and make the blue look more blue by accenting the complementary colours and painting the ground and surroundings[54] warmer—i.e. by painting the whole picture in a warmer key.

There is the danger, of course, of going over to the other extreme, but of the two it is better to err on the side of warmth than of coldness; and I think that probably one reason of the fineness of colour of the Venetians is that they had the possible blue of the sky in their minds, if not in their pictures, as a key and point of contrast with their other colours. But doubtless the main reason was the situation and importance of Venice, and its relations with the East; which gave its artists the finest possible opportunities of studying colour. People of all races were there, dressed in fine and varied colours, and moving among beautiful buildings, with the sea and sky for background; and the Venetian artists had this fine show daily before their eyes, under all conditions of lighting. All the possibilities of colour would become familiar to them, and we can understand how the influence of their surroundings led them to their great results.

If we aim at getting the utmost fulness of colour in the lights, as the Venetians did, the limited[55] range of our colours makes this impossible in the darks. It becomes necessary, then, to keep all the darks together, treating them very broadly. You will find the old painters were never afraid of strong darks or dark shadows. Sir Joshua Reynolds advises that in a picture the shadows should be all of one colour; or, at least, he says, they should appear to be of one colour, meaning that the eye should not rest on nor question them. And though the old pictures impress one as being darker than nature,—and so, in the sense of the general colour of nature, untrue,—yet in themselves and within their conditions they give a true impression of nature.

We have not the opportunity of studying fine colours that the old painters had; our life goes on in more sombre dress. Still, there is fine colour to be seen wherever the sun shines, here as elsewhere, and of late years the search for the fulness of colour, with light, has led artists to the furthest limits of the palette, and the most violent means, in endeavouring to get the range and force of colour in the shadows as well as in the lights, so that we find pictures painted in spots of pure[56] pigment placed side by side, the intention being that they should fuse together in the eye of the spectator. But the result is not successful; it is distressing to the eye, and, I think, shows that something must be sacrificed at one end of the scale or the other. And yet, if we paint in a very high key, in simple tints, I question if we are not in some danger of starving our colour for the sake of keeping our pictures light. White paint will not of itself express light, but only by contrast with dark.

To get colour and light is the great thing. The difficulty is to get them both. Turner, in his Italian landscapes, enhanced the colour of his sky by a dark pine-tree in the foreground, sacrificing the colour of the tree for the sake of accenting its value and warmth; and the old landscape painter’s device of a brown tree is used for the same end—to make the blue of the sky and distance more luminous and beautiful. This is also the reason for the dark-brown foreground usual in old landscapes; and our eye is not arrested by the tree or the dark foreground, but goes past it to the point of the picture.

[57]

Rembrandt, in his colouring, seems to have avoided blue altogether, gaining the sense of it by the opposition of golden-brown to grey. The secret of his wonderful colour is difficult to read. A passing impression of one of his pictures is of a work all in golden-brown, with fine reds and strong blacks. But when one has looked long enough at it to get into the picture, as it were, this sense of a particular colour disappears, and we feel ourselves in presence of the actual scene, with its air, colour, and light.

I do not think we should try and imitate the colour of the old painters, though we can, by study, see in nature the indications of, and perhaps the reasons for, their method of work. It would be hopeless, for instance, for anyone to try and imitate Rembrandt’s colouring; and probably Rembrandt himself would be unable to explain his method, but would simply say, “I saw it so,” or “I wished to express a particular sentiment.”

There is the question of quality of colour—another difficult thing to define, though we recognise it readily. It does not seem to depend on[58] truth of relations, or even on truth of colour, for a picture may be true in colour and yet the paint itself may be bad in quality—opaque, heavy, or showing much labour. But there is fine quality of colour in works differing as much from each other in method as Rembrandt and the Primitives, as Raphael and Franz Hals, as Velasquez and Titian. It means that the work impresses one as having clearness, freshness, and that, in short, the impression is produced of nature, and not of paint.

There are two methods of painting, and good quality of colour can be achieved by either. One method is that of simple and direct painting—that we put down the right colour at once with fresh, untroubled paint, as in a sketch, and we know how often there is greater charm in a sketch than in a finished work. This is the method of Hals, of Velasquez, of Moroni, and of most moderns. The other method is the elaborate one of preparing an underpainting, more or less of the nature of monochrome, with reference only to the drawing and massing of light and shade, and then painting by thin glazes, or by working over[59] thin glazes with the right colours, the under colours showing through, and giving a richness and transparency. I think we see this in the work of Rubens and of Titian, though, of course, we nearly always see both direct and glazed colour in the same work, as in that most marvellous head by Rembrandt, of himself as an old man, in the National Gallery. The object of underpainting and glazing is, of course, to retain the freshness which is so easily lost in oil painting, if the same colour is painted over and over; especially as when half-dry, or if much medium is used, it becomes muddy: stiff colour stands fairly well.

Another object of underpainting is the determining of the design in light and dark. All paint changes a little, lowers a little, with time; and if a picture has no strong arrangement of light and dark, but depends for its beauty on subtle delicacies and differences of value, these are often lost in a few years through the flattening down of the paint; while if there is a strong backbone, as it were, of light and shade beneath the colour, the picture will always be effective, and the main features remain, in spite of any little changes.

[60]

The painter has to make the quality of his paint in oil-colour. If you compare oil- with water-colour you will see what I mean; for if you put a simple wash of colour on paper it is always beautiful, because of its transparency, and it is difficult to lose this quality in water-colour; but it is difficult to get it in oil, and still more difficult to retain it throughout a work.

Good quality is a measure of the painter’s perception. Two men will paint a plain blue sky, using, perhaps, the same pigment. One man will give you the actual sense of the sky and the air, and the other nothing but blue paint. The difference between them is that one man had perception of the quality of the sky, and the other had not. So, when we see a good quality in paint, we know that it means not only niceness of hand and perception, but great knowledge and judgment in the artist. It all comes back to the same old story—that we must work, and cultivate our perceptions.

I have spoken of the emotional power of colour—i.e. the power which colours in themselves have in inducing a mood—as an important element in painting. The sad, golden tone of Rembrandt[61] seems to strike the keynote of his sentiment, and to bring us into his frame of mind before we realise his subject. In the same way, the rich reds and warm colours of Titian, Rubens, and Reynolds produce in our minds the sense of activity, richness, and splendour, quite irrespective of the drawing or modelling of their figures, or their meaning.

If they had painted their figures as they would look in the cold light of a studio, this effect would not have been produced.

The picture of Admiral Keppel by Reynolds, in the present Old Masters Exhibition, is painted in a clear grey key of daylight—a realistic effect, as anyone might see it; and one may infer from this that in those instances where Reynolds darkened down his pictures with rich warm glazes, it was done designedly, in order to produce an effect by the means of colour.

I think, then, that we may conclude in these cases—I may mention as an example an “Adoration of the Magi,” by Filippino Lippi, in the National Gallery, where red and gold and other rich colours are pushed to their extreme power—that[62] painters deliberately employed the emotional power of colour, as colour, quite apart from any immediate resemblance to nature, in order to produce an effect on the mood of the spectator. And it must be the most difficult thing of all in painting, to do this so as to include general truth of resemblance.

But these paths are outside the track of most artists to-day. Our efforts are not so much directed to imaginative subjects, as to actualities, and our endeavour is to find and express the beauty which exists among us. We are more literal, less imaginative; and this enhancing of nature by the power of colour is beyond us. We feel that it may be possible to paint with our first and main reference to nature as we see it around us, and, while trying to understand what has been done, to claim still that beauty of colour may be found also in the plain aspect of visible things even to-day.

It is for this reason, I think, that the art of Velasquez specially appeals to us. In it the ordinary aspects of nature are found to be not inconsistent with the finest art. There is nothing conventional in his colour. It is simply like that[63] of nature, and I think that none but artists, or those who have studied the appearance of nature, can quite understand the intense admiration his work excites. It is not, as in the case of Titian and the colourists, an emotion produced by colour, as colour, taking us beyond our ordinary sensations; but it gives us something of the pleasure of a surprise, in finding and recognising that such beautiful modulations of colour are apparent under ordinary conditions. Velasquez is sometimes, perhaps rightly, called unemotional, because his colour is not prearranged to influence us, but is, as it were, an impartial statement, as contrasted with the work of those painters who pushed the emotional power of colour to its extreme limit.

As I hope to consider the work of Velasquez later, I will not touch further on it now, but may mention one or two men of kindred spirit. Chardin, the French painter, gives us very beautiful colour in his still-life paintings in the Louvre, and there is one in the National Gallery. We are shown, not what beautiful things are painted, but how beautiful they appear under the influence of[64] light. The effect of one colour on another, the harmony of the different tints produced by light on a few simple things—these things may be seen in his work; as also in the work of Edouard Manet, who had much the same feeling as Velasquez for the beauty of colour in simple, cool lighting, and expressed it with a directness of vision and execution (being able by a true eye to strike the tint at once) that gives his colour a very great charm.

The splendid work of Sir John Millais—the “North-West Passage” and the “Yeomen of the Guard,” for example—appeal to us in the same way, as fine painting and fine colour, apart from the interest of the subject. And that great artist who died recently—Mr. Whistler—has not only given us the example of a fine and simple method in painting, but has shown us more fully than any other artist the modulations of colour by light. In his portraits, with their fine realisation of the effects of atmosphere on colour, and in his pictures of twilight and of night, he has recorded effects which no artist before him had attempted. We can all see these things now, and how beautiful they are, but Mr. Whistler was the one who showed[65] us. He was, I think, the one artist since Turner who has extended the range of the artist’s vision in the direction of revealing to us the beauty of colour as it appears in nature.

I have already spoken of the painter’s main difficulty—in determining the proper relation of parts to the whole—in the matter of lighting and arrangement of his picture. This is also the main difficulty in colouring, and the only solution I can give you is that you should, at least once, endeavour to have the scene you are painting—if it is of such a nature that you can do this—actually before you, and to consider it as a whole, taking in the whole scene as comprehensively as possible; and so you can judge the effect of one colour against another, and see which colour strikes you most unmistakably, and so gives the keynote to the rest. We should study in the same way anything we happen to see that strikes us as having the material for a picture.

Truth or beauty of colour is the main thing in a picture. It is, in fact, the only thing that gives a picture a high place among the masterpieces. A picture that is well drawn and modelled[66] only will interest, but will be passed by in favour of colour. For colour touches us more deeply; its sense is more instinctive. A child will be excited by colours, but indifferent to form. We all, artists or not, have some latent memory or mental image, which is called forth in us when we look at a picture, and recognise, or fail to recognise, nature in it; not, I think, so much by our memories of form, as by our memories of the colour and general appearance of nature.

We can only see what we have learned to look for. An uneducated person will consider a face in a picture beautiful if it has bright eyes, pink cheeks, and red lips; or a landscape beautiful if it also presents him with the obvious facts. It will be enough for him; it is as much as he sees in nature. But Nature does not reveal her beauties unsought, and the study of paintings by those who are not artists is not only an education, but an added pleasure to their lives, enlarging and directing their minds, so that they learn to detect and appreciate beauties in nature to which they would otherwise have been blind.

[69]

In speaking of these great artists, the greatest masters of painting that the world has seen, I do not propose to do more than make a rough comparison of their main qualities, with the idea of indicating the points of agreement and of difference between them. It seems almost an impertinence to speak at all of men who are above discussion or praise, whose names alone suggest the finest painting, and each of whom in his own way has reached the limits of achievement. One might discuss all the problems of painting by reference only to what each has done. I am not qualified to do this, but can only give my own, perhaps superficial, impressions of their work.

It seems to me that the differences which divide Italian painting into schools are of much less[70] account than are the great qualities these schools had in common—a noble simplicity of form, broad lighting, and rich, full colouring. Indeed, to my mind there are only two schools of Italian painting—Michelangelo is the one, and the rest of the Italian painters all come together in the other. The great ceiling of the Sistine Chapel stands apart from, and beyond, all other work; but of all the other Italians, Titian most fully represents the finest painting. By his great genius he brought together the theories of his predecessors, and carried on their practice to a degree of completeness which cannot be surpassed. Velasquez said, “It is Titian who bears the banner”; whether in subject pictures or portraits, his work is perfect in all the qualities of painting, and it may almost be said that he has done with colour all that can be done.

He is the meeting-point of the old and the new. His work combines minuteness and freedom. His early training must have given him the power he possessed of treating detail with the most dainty fineness, yet keeping it always in its place, never letting it appear laboured or[71] obtrusive. There is a “Madonna” of his in the Vienna Gallery—an early work—that has the clearness and simplicity of the Primitives, with a greater fulness. It is carried to the finest point of realisation, with seemingly the greatest ease. It is one of the most beautiful things in the Gallery.

Titian chose, as a rule, a simple mode of lighting—a warm daylight, or evening light, upon his figures; not concentrating the interest on one main point of his picture by suppression of minor things, but controlling it from one end to the other, and including everything in his attention. His effect was produced by devices of composition which he invented, or developed, from his own observation of nature. I have already indicated how, by relieving figures in light by figures and objects in shade, or by uniting figures and groups by shadows—on the ground, on or from trees and buildings—he constructed his pictures, using these momentary effects of contrast which we may notice for ourselves in nature. These devices, besides enabling him to make his picture by placing his principal[72] objects in prominence, give us the sense of living and moving nature; of man not merely posed against a background of landscape or building, but in the scene, and part of its setting, so that one influence is felt throughout. And in this use of landscape, as well as in his treatment of landscape as a mood of nature, and not a transcript of nature, Titian was the first and one of the greatest of landscape painters.

His method was usually to keep the principal parts of his picture warm and light, and this warmth was enhanced by the blue of the sky, which he frequently used in his background; and the colours of his principal figures were made to tell out strongly, as well as separated from the background, by masses or spaces of shadow in the middle distance; as we see in the picture of the “Entombment” in the Louvre. We may notice, too, in this picture how the central light is packed round with various colours—rich reds and dark greens—in the dresses of the supporting figures.

When we endeavour, in cold blood, as it were, to gauge the actual colour of his work by comparing it with white, its richness and depth are[73] amazing. It seems, indeed, to go beyond the power of the palette as we know it, but, of course, it cannot be so; and it is recorded that Titian used few and very simple colours to produce his fine harmonies. I doubt if his work owes much to the mellowing of age. It must always have been fine and rich, and I think, as I have said, that the Italian painters were led in the direction of warm and glowing colour through feeling strongly the beauty of blue; for, as we know, it is only by keeping the whole tone of a picture warm that the beauty of blue can be expressed. How this richness was produced, this depth without darkness, has been again and again discussed. It is called the “Venetian secret,” and certainly no other painting is so full of colour; and is considered—I think rightly—to have been produced by first painting a solid monochrome in tempera, on which the picture was finished, in its colours, in oil. But we need not trouble much about the method, for whatever it was, great knowledge, and that only, was the secret of Titian, as of all the other masters. This is brought home to us when we see a number of fine pictures[74] of different schools hanging side by side, as in the Salon Carré of the Louvre, where there are on the same wall, works by painters as different in their methods as Rembrandt and Giorgione, Da Vinci and Velasquez, Raphael and Holbein, all agreeing together like good brothers. Their methods are as various as may be, but great knowledge was the basis of them all.

When in presence of one of Titian’s pictures we are conscious of their being true to a noble vision of nature,—i.e. that particular elements have been chosen and put before us,—and we feel, although we are not always conscious of it, except by comparison with other men’s work, a sentiment, which by means of colour alone he has conveyed to us. I think the sentiment of his pictures is communicated but little by form or expression, and almost entirely by the emotional power of their colour. His figures have the natural grace and gravity of their race, with an air of nobility, and, as Reynolds says, of senatorial dignity, of his own; but to me they seem to go through their actions as in a formal pageant, without interest, with something even of an air of[75] indifference. There is in them nothing of the familiar, passionate human interest—of insight, almost, one feels, into the very souls of his subjects, that we find in Rembrandt; which moves us so deeply, and makes us—at anyrate, I find it so—to hold Rembrandt nearer to our hearts than any other artist. Titian’s power is in the beauty of his colour, and this is the special power of the painter. By his command of colour he imposes his mood upon us without our knowledge, making us look at nature through his eyes.

Titian was greatest as a portrait painter, as Reynolds has said. In arrangement, and in painting, and in character also, although he does not give so searching a reading as Rembrandt, they are as fine as can be. We have none in our National Gallery, but there is a very fine portrait in the Louvre, the “Man with the Glove.” This work is beautifully drawn and modelled, the head very simply and broadly, so that everything seems left out, but everything essential is there. The head is not forced out into the highest light, as is the usual practice now, but is kept lower in tone than the linen,[76] which is the brightest light, and each colour tells in its natural degree. I should imagine that his painting-room was not lighted in our ordinary way, from the north, but probably from the south, with a veiled light, and that he painted or studied sometimes out of doors; for the lighting of his pictures could, I think, only have been arrived at by studying in sunlight, or perhaps by artificial light. His portraits seem to me to have very much the effect, both in colour and modelling, of people as seen by the light of a candle, where the light is reflected from the bright colours only, and is absorbed by the dark ones.

The influence of Titian can be traced in the work of all succeeding painters. Both Velasquez and Rembrandt owe something to him; Velasquez more than Rembrandt, as he was better acquainted with his work. But the influence of Titian, of Rubens, and of Tintoret on Velasquez only supplemented, and did not lead him away from, his own frank and straightforward view of nature.

We know, now that we have his whole life’s[77] work before us, that Velasquez had the surest eye and the truest hand of any artist who has ever lived, or at least that he was the equal in this respect of any other artist; but if we look at his early work in the National Gallery, we find that it is not “clever” in any sense. It is most uncompromising, somewhat heavy-handed, one may almost say common, in its execution; suggesting not brilliant ability, but clear insight and determination. We may notice in this picture—the small still-life group with figures, called “Christ in the House of Martha”—how everything is set down relentlessly and thoroughly; and in another early work, the “Dead Warrior,” we see the same thing—everything is painted deliberately and apparently without alterations. It is only those who try to paint who know how much knowledge, how much determination, this implies.

But so much is said of the freedom of Velasquez’s painting, and so often is his name used to justify careless and sloppy work, that one may be allowed to draw attention again to the old truth—that this freedom was only gained at the[78] price of labour, greater than most of his worshippers seem willing or able to undertake; and that the charm of his painting is that, with all its freedom, it is so careful and so beautifully drawn. He having, by great labour, learnt what to do, practice gave him a ready means to his end. It is surely, then, a mistaken idea for an artist to think that he can begin in Velasquez’s later manner, where he left off. If he will follow this great master, let him begin as the master began, and tramp the whole road.

The work of Velasquez seems to reveal the temperament of a dispassionate observer, with an eye so keen and so thoroughly trained that nothing escapes him; but he does not show us his own feeling towards his sitter. In other painters’ work, we get at least some hint of the artist’s feeling towards the persons he brings before us, but we do not get this in Velasquez. He is a perfect mirror. His attitude is that of one apart, or aloof, from his fellows, understanding, but without appearing to show sympathy or enthusiasm. These feelings seem to be reserved for the painting itself, though in some[79] of his pictures, such as the “Surrender of Breda,” where, I fancy, the Italian influence can be seen, and in some of his dwarfs, there is, I think,—I have not seen the pictures themselves, and only know them from photographs and copies,—a little nearer approach to his persons, a little less detachment than usual.