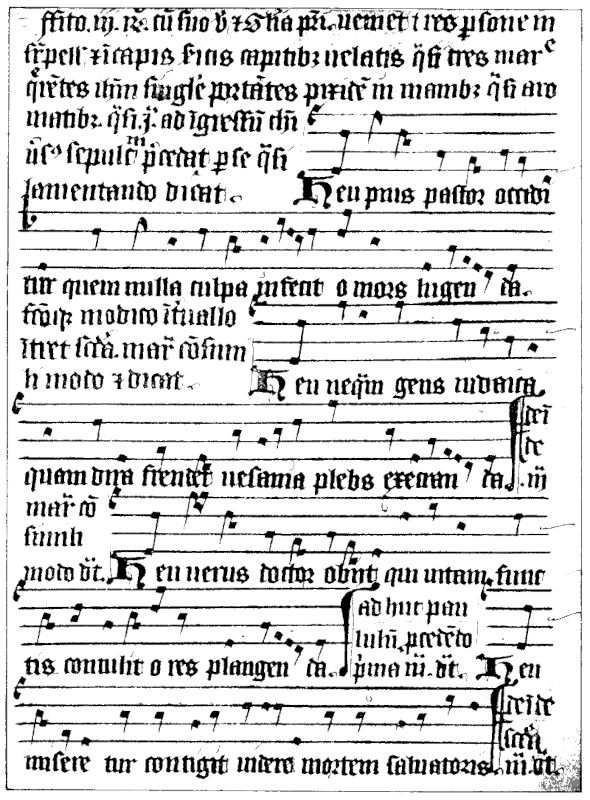

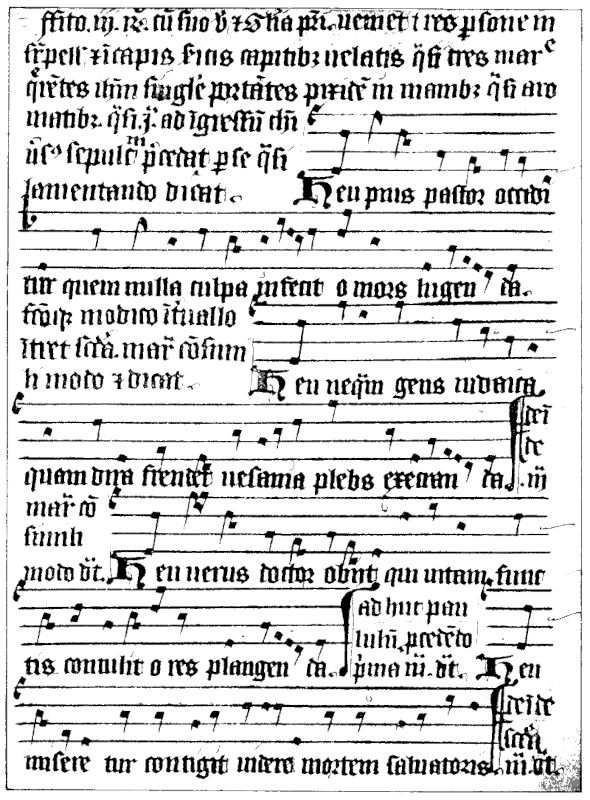

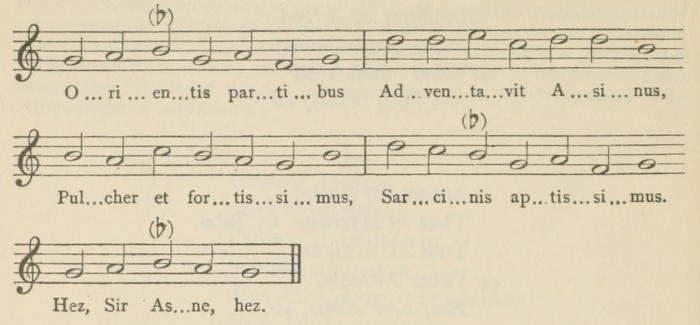

BEGINNING OF DUBLIN Quem quaeritis,

FROM BODLEIAN RAWLINSON LITURGICAL MS. D. 4

(14TH CENTURY)

| MusicXML]

Title: The mediaeval stage, volume 2 (of 2)

Author: E. K. Chambers

Release date: November 23, 2025 [eBook #77310]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Oxford University Press, 1903

Credits: Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected. Variations in hyphenation and accents have been standardised but all other spelling and punctuation remains unchanged. The first volume is available as Project Gutenberg eBook #73000. Only the references within this volume are hyperlinked.

BEGINNING OF DUBLIN Quem quaeritis,

FROM BODLEIAN RAWLINSON LITURGICAL MS. D. 4

(14TH CENTURY)

| MusicXML]

[i]

BY

E. K. CHAMBERS.

VOL. II

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

M.CMIII

[ii]

Impression of 1925

First Edition 1903

This impression has been produced photographically by the

Muston Company, from sheets of the First Edition

Printed wholly in England for the Muston Company

By Lowe & Brydone, Printers, Ltd.

Park Street, Camden Town, London, N.W. 1.

[iii]

| Volume I | |||

| PAGE | |||

| Preface | v | ||

| List of Authorities | xiii | ||

| BOOK I. MINSTRELSY | |||

| CHAP. | |||

| I. | The Fall of the Theatres | 1 | |

| II. | Mimus and Scôp | 23 | |

| III. | The Minstrel Life | 42 | |

| IV. | The Minstrel Repertory | 70 | |

| BOOK II. FOLK DRAMA | |||

| V. | The Religion of the Folk | 89 | |

| VI. | Village Festivals | 116 | |

| VII. | Festival Play | 146 | |

| VIII. | The May-Game | 160 | |

| IX. | The Sword-Dance | 182 | |

| X. | The Mummers’ Play | 205 | |

| XI. | The Beginning of Winter | 228 | |

| XII. | New Year Customs | 249 | |

| XIII. | The Feast of Fools | 274 | |

| XIV. | The Feast of Fools (continued) | 301 | |

| XV. | The Boy Bishop | 336 | |

| XVI. | Guild Fools and Court Fools | 372 | |

| XVII. | Masks and Misrule | 390 | |

| Volume II | |||

| BOOK III. RELIGIOUS DRAMA | |||

| XVIII. | Liturgical Plays | 1 | |

| XIX. | Liturgical Plays (continued) | 41 | |

| XX. | The Secularization of the Plays | 68 | |

| XXI. | Guild Plays and Parish Plays | 106 | |

| XXII. | Guild Plays and Parish Plays (continued) | 124 | |

| XXIII. | Moralities, Puppet-Plays, and Pageants | 149[iv] | |

| BOOK IV. THE INTERLUDE | |||

| XXIV. | Players of Interludes | 179 | |

| XXV. | Humanism and Mediaevalism | 199 | |

| APPENDICES | |||

| A. | The Tribunus Voluptatum | 229 | |

| B. | Tota Ioculatorum Scena | 230 | |

| C. | Court Minstrelsy in 1306 | 234 | |

| D. | The Minstrel Hierarchy | 238 | |

| E. | Extracts from Account Books | 240 | |

| I. | Durham Priory | 240 | |

| II. | Maxstoke Priory | 244 | |

| III. | Thetford Priory | 245 | |

| IV. | Winchester College | 246 | |

| V. | Magdalen College, Oxford | 248 | |

| VI. | Shrewsbury Corporation | 250 | |

| VII. | The Howards of Stoke-by-Nayland, Essex | 255 | |

| VIII. | The English Court | 256 | |

| F. | Minstrel Guilds | 258 | |

| G. | Thomas de Cabham | 262 | |

| H. | Princely Pleasures at Kenilworth | 263 | |

| I. | A Squire Minstrel | 263 | |

| II. | The Coventry Hock-Tuesday Show | 264 | |

| I. | The Indian Village Feast | 266 | |

| J. | Sword-Dances | 270 | |

| I. | Sweden (sixteenth century) | 270 | |

| II. | Shetland (eighteenth century) | 271 | |

| K. | The Lutterworth St. George Play | 276 | |

| L. | The Prose of the Ass | 279 | |

| M. | The Boy Bishop | 282 | |

| I. | The Sarum Office | 282 | |

| II. | The York Computus | 287 | |

| N. | Winter Prohibitions | 290 | |

| O. | The Regularis Concordia of St. Ethelwold | 306 | |

| P. | The Durham Sepulchrum | 310 | |

| Q. | The Sarum Sepulchrum | 312 | |

| R. | The Dublin Quem Quaeritis | 315[v] | |

| S. | The Aurea Missa of Tournai | 318 | |

| T. | Subjects of the Cyclical Miracles | 321 | |

| U. | Interludium de Clerico et Puella | 324 | |

| V. | Terentius et Delusor | 326 | |

| W. | Representations of Mediaeval Plays | 329 | |

| X. | Texts of Mediaeval Plays and Interludes | 407 | |

| I. | Miracle-Plays | 407 | |

| II. | Popular Moralities | 436 | |

| III. | Tudor Makers of Interludes | 443 | |

| IV. | List of Early Tudor Interludes | 453 | |

| SUBJECT INDEX | 462 | ||

[1]

[Bibliographical Note.—The liturgical drama is fully treated by W. Creizenach, Geschichte des neueren Dramas (vol. i, 1893), Bk. 2; L. Petit de Julleville, Les Mystères (1880), vol. i. ch. 2; A. d’Ancona, Origini del Teatro Italiano (2nd ed. 1891), Bk. 1, chh. 3-6; M. Sepet, Origines catholiques du Théâtre moderne (1901), and by L. Gautier in Le Monde for Aug. and Sept. 1872. The studies of W. Meyer, Fragmenta Burana (1901), and C. Davidson, English Mystery Plays (1892), are also valuable. A. W. Ward, History of English Dramatic Literature (2nd ed. 1899), vol. i. ch. 1 deals very slightly with the subject. A good popular account is M. Sepet, Le Drame chrétien au Moyen Âge (1878). Of older works, the introduction to E. Du Méril’s Origines latines du Théâtre moderne (1849, facsimile reprint, 1896) is the best. The material collected for vol. ii of C. Magnin’s Origines du Théâtre is only available in the form of reviews in the Journal des Savants (1846-7), and lecture notes in the Journal général de l’Instruction publique (1834-6). Articles by F. Clément, L. Deschamps de Pas, A. de la Fons-Melicocq, and others in A. N. Didron’s Annales archéologiques (1844-72) are worth consulting; those of F. Clément are reproduced in his Histoire de la Musique religieuse (1860). There are also some notices in J. de Douhet, Dictionnaire des Mystères (1854).—The texts of the Quem quaeritis are to be studied in G. Milchsack, Die Oster- und Passionsspiele, vol. i (all published, 1880), and C. Lange, Die lateinischen Osterfeiern (1887). The former compares 28, the latter no less than 224 manuscripts. The best general collection of texts is that of Du Méril already named: others are T. Wright, Early Mysteries and other Latin Poems (1838); E. de Coussemaker, Drames liturgiques du Moyen Âge (1860), which is valuable as giving the music as well as the words; and A. Gasté, Les Drames liturgiques de la Cathédrale de Rouen (1893). A few, including the important Antichristus, are given by R. Froning, Das Drama des Mittelalters (1891). The original sources are in most cases the ordinary service-books. But a twelfth-century manuscript from St. Martial of Limoges (Bibl. Nat. Lat. 1139) has four plays, a Quem quaeritis, a Rachel, a Prophetae, and the Sponsus. Facsimiles are in E. de Coussemaker, Histoire de l’Harmonie au Moyen Âge (1852). A thirteenth-century manuscript from Fleury (Orleans MS. 178) has no less than ten, a Quem quaeritis, a Peregrini, a Stella in two parts, a Conversio Pauli, a Suscitatio Lazari and four Miracula S. Nicholai. Two later plays and fragments of three others are found in the famous thirteenth-century manuscript from Benedictbeuern (Munich MS. 19,486, printed in J. A. Schmeller, Carmina Burana, 3rd ed. 1894, with additional fragments in W. Meyer, Fragmenta Burana, 1901). This is probably the repertory of travelling goliardic clerks. The twelfth-century manuscript which preserves the three plays of Hilarius (Bibl. Nat. Lat. 11,331, printed in J. J. Champollion-Figeac, Hilarii Versus et Ludi, 1838) is of a similar character.—The tropes are fully dealt with by L. Gautier, Hist. de la [2]Poésie liturgique au Moyen Âge, vol. i (all published, 1886), and W. H. Frere, The Winchester Troper (1894). I have not been able to see A. Reiners, Die Tropen-, Prosen- und Präfations-Gesänge des feierlichen Hochamtes im Mittelalter (1884). Antiquarian data are collected by H. J. Feasey, Ancient English Holy Week Ceremonial (1897), and A. Heales, Easter Sepulchres, in Archaeologia, vol. xlii. I have printed an important passage from the Regularis Concordia of St. Ethelwold (965-75) in Appendix O. The Planctus Mariae are treated by A. Schönbach, Die Marienklagen (1874), and E. Wechssler, Die romanischen Marienklagen (1893). W. Köppen, Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Weihnachtsspiele (1893), and M. Sepet, Les Prophètes du Christ (1878), contain valuable studies of the evolution of the Stella and the Prophetae respectively. The relation of dramatic to iconic art in the Middle Ages is brought out by P. Weber, Geistliches Schauspiel und kirchliche Kunst (1894). A rather primitive bibliography is F. H. Stoddard, References for Students of Miracle Plays and Mysteries (1887).—Authorities for English facts given without references in the present volume will be found in Appendices W and X.]

The discussions of the first volume have often wandered far enough from the history of the stage. But two or three tolerable generalizations emerge. The drama as a living form of art went completely under at the break-up of the Roman world: a process of natural decay was accelerated by the hostility of Christianity, which denied the theatre, and by the indifference of barbarism, which had never imagined it. If anything of a histrionic tradition survived, it took the shape of pitiable farce, one amongst many heterogeneous elements in the spectacula of disreputable mimes. For the men of the Middle Ages, however, peasants or burghers, monks or nobles, such spectacula had a constant attraction: and the persistence of the deep-rooted mimetic instinct in the folk is proved by the frequent outcrops of primitive drama in the course of those popular observances which are the last sportive stage of ancient heathen ritual. Whether of folk or of minstrel origin, the ludi remained to the last alien and distasteful to the Church. The degradation of Rome and Constantinople by the stage was never forgotten; nor the association with an heathenism that was glossed over rather than extinct: and though a working compromise inevitably tended to establish itself, it remained subject to perpetual protest from the austerer spirit in the counsels of the clergy.

It is the more remarkable that the present volume has to describe a most singular new birth of the drama in the very bosom of the Church’s own ritual. One may look at the [3]event as one will, either as an audacious, and at least partly successful, attempt to wrest the pomps of the devil to a spiritual service, or as an inevitable and ironical recoil of a barred human instinct within the hearts of its gaolers themselves. From either point of view it is a fact which the student of European culture cannot afford to neglect. And apart from its sociological implications, apart from the insight which it gives into the temper of the folk and into the appeal of religion, it is of the highest interest as an object lesson in literary evolution. The historian is not often privileged to isolate a definite literary form throughout the whole course of its development, and to trace its rudimentary beginnings, as may here be done, beyond the very borders of articulate speech.

The dramatic tendencies of Christian worship declared themselves at an early period[1]. At least from the fourth century, the central and most solemn rite of that worship was the Mass, an essentially dramatic commemoration of one of the most critical moments in the life of the Founder[2]. It is [4]his very acts and words that day by day throughout the year the officiating priest resumes in the face of the people. And when the conception of the Mass developed until instead of a mere symbolical commemoration it was looked upon as an actual repetition of the initial sacrifice, the dramatic character was only intensified. So far as the Canon of the Mass goes, this point needs no pressing. But the same liturgical principle governs many other episodes in the order of the mediaeval services. Take, for example, the ritual, of Gallican origin, used at the dedication of a church[3]. The bishop and his procession approach the closed doors of the church from without, but one of the clergy, quasi latens, is placed inside. Three blows with a staff are given on the doors, and the anthem is raised Tollite portas, principes, vestras et elevamini, portae aeternales, et introibit Rex gloriae. From within comes the question Quis est iste rex gloriae? and the reply is given Dominus virtutum ipse est Rex gloriae. Then the doors are opened, and as the procession sweeps through, he who was concealed within slips out, quasi fugiens, to join the train. It is a dramatic expulsion of the spirit of evil. A number of other instances are furnished by the elaborate rites of Holy week. Thus on Palm Sunday, in commemoration of the entry into Jerusalem, the usual procession before Mass was extended, and went outside the church and round the churchyard or close bearing palms, or in their place sprigs of yew, box, or withies, which the priest had previously blessed[4]. [5]The introduction of a Palmesel might make the ceremony more dramatic still[5]. Some of the texts used were of a prophetic character, and the singer of these was occasionally dressed as a prophet[6]. At the doors of the church the procession was greeted by boys stationed upon the roof of the porch, and certain French uses transferred to the occasion the dedication solemnity of Tollite portas just described[7]. The reading of the gospel narratives of the Passion, which on Palm Sunday, on the Monday or Tuesday, and the Wednesday in Holy week and on Good Friday preceded the Gospel proper, was often resolved into a regular oratorio. A tenor voice rendered the narrative of the evangelist, a treble the sayings of Jews and disciples, a bass those of Christ himself[8]. To particular episodes of these Passions special dramatic action was appropriated. On Wednesday, at the words Velum templi scissum est, the Lenten veil, which since the first Sunday in Lent had hidden the sanctuary from the sight of the people, was dropped to the ground[9]. On Good Friday the [6]words Partiti sunt vestimenta were a signal for a similar bit of by-play with a linen cloth which lay upon the altar[10]: Maundy Thursday had its commemorative ceremony of the washing of feet[11]; while the Tenebrae or solemn extinction, one after another, of lights at the Matins of the last three days of the week, was held to symbolize the grief of the apostles and others whom those lights represented[12].

These, and many other fragments of ceremonial, have the potentiality of dramatic development. Symbolism, mimetic action, are there. The other important factor, of dialogued speech, is latent in the practice of antiphonal singing. The characteristic type of Roman chant is that whereby the two halves of the choir answer one another, or the whole choir answers the single voice of the cantor, in alternate versicle and respond[13]. The antiphon was introduced into Italy by St. Ambrose of Milan. It had originated, according to tradition, in Antioch, had been in some relation to the histrionic tendencies of Arianism, and was possibly not altogether uninfluenced by the traditions both of the Greek tragic chorus and of Jewish psalmody[14]. [7]At any rate, it lent itself naturally to dialogue, and it is from the antiphon that the actual evolution of the liturgical drama starts. The course of that evolution must now be followed.

The choral portions of the Mass were stereotyped about the end of the sixth century in the Antiphonarium ascribed to Gregory the Great[15]. This compilation, which included a variety of antiphons arranged for the different feasts and seasons of the year, answered the needs of worship for some two hundred years. With the ninth century, however, began a process, which culminated in the eleventh, of liturgical elaboration. Splendid churches, costly vestments, protracted offices, magnificent processions, answered especially in the great monasteries to a heightened sense of the significance of cult in general, and of the Eucharist in particular[16]. Naturally ecclesiastical music did not escape the influence of this movement. The traditional Antiphonarium seemed inadequate to the capacities of aspiring choirs. The Gregorian texts were not replaced, but they were supplemented. New melodies were inserted at the beginning or end or even in the middle of the old antiphons. And now I come to the justification of the statement made two or three pages back, that the beginnings of the liturgical drama lie beyond the very borders of articulate speech. For the earliest of such adventitious melodies were sung not to words at all, but to vowel sounds alone. These, for which precedent existed in the Gregorian Antiphonarium, are known as neumae[17]. Obviously the next stage was to write texts, called generically ‘tropes,’ to them; and towards the end of the ninth century three more or less independent schools of trope-writers grew up. One, in northern France, produced Adam of St. Victor; of another, [8]at the Benedictine abbey of St. Gall near Constance, Notker and Tutilo are the greatest names; the third, in northern Italy, has hitherto been little studied. The Troparia or collections of tropes form choir-books, supplementary to the Antiphonaria. After the thirteenth century, when trope-writing fell into comparative desuetude, they become rare; and such tropes as were retained find a place in the ordinary service-books, especially the later successor of the Antiphonarium, the Graduale. The tropes attached themselves in varying degrees to most of the choral portions of the Mass. Perhaps those of the Alleluia at the end of the Graduale are in themselves the most important. They received the specific names, in Germany of Sequentiae, and in France of Prosae, and they include, in their later metrical stages, some of the most remarkable of mediaeval hymns. But more interesting from our particular point of view are the tropes of the Officium or Introit, the antiphon and psalm sung by the choir at the beginning of Mass, as the celebrant approaches the altar[18].

Several Introit tropes take a dialogue form. The following is a ninth-century Christmas example ascribed to Tutilo of St. Gall[19].

‘Hodie cantandus est nobis puer, quem gignebat ineffabiliter ante tempora pater, et eundem sub tempore generavit inclyta mater.

[9]

Int[errogatio].

quis est iste puer quem tam magnis praeconiis dignum vociferatis? dicite nobis ut collaudatores esse possimus.

Resp[onsio].

hic enim est quem praesagus et electus symmista dei ad terram venturum praeuidens longe ante praenotavit, sicque praedixit.’

The nature of this trope is obvious. It was sung by two groups of voices, and its closing words directly introduce the Introit for the third mass (Magna missa) on Christmas day, which must have followed without a break[20]. It is an example of some half a dozen dialogued Introit tropes, which might have, but did not, become the starting-point for further dramatic evolution[21]. Much more significant is another trope of unknown authorship found in the same St. Gall manuscript[22]. This is for Easter, and is briefly known as the Quem quaeritis. The text, unlike that of the Hodie cantandus, is based closely upon the Gospels. It is an adaptation to the form of dialogue of the interview between the three Maries and the angel at the tomb as told by Saints Matthew and Mark[23].

This is the earliest and simplest form of the Quem quaeritis. [10]It recurs, almost unaltered, in a tenth-century troper from St. Martial of Limoges[25]. In eleventh-century tropers of the same church it is a little more elaborate[26].

Here the appended portion of narrative makes the trope slightly less dramatic. Yet another addition is made in one of the Limoges manuscripts. Just as the trope introduces the Introit, so it is itself introduced by the following words:

As M. Gautier puts it, the trope is troped[27].

In the Easter Quem quaeritis the liturgical drama was born, and to it I shall return. But it must first be noted that it was so popular as to become the model for two very similar tropes belonging to Christmas and to the Ascension. Both of these are found in more than one troper, but not earlier, I believe, than the eleventh century. I quote the Christmas trope from a St. Gall manuscript[28].

[11]

‘In Natale Domini ad Missam sint parati duo diaconi induti dalmaticis, retro altare dicentes

Quem quaeritis in praesepe, pastores, dicite?

Respondeant duo cantores in choro

salvatorem Christum Dominum, infantem pannis involutum, secundum sermonem angelicum.

Item diaconi

adest hic parvulus cum Maria, matre sua, de qua, vaticinando, Isaias Propheta: ecce virgo concipiet et pariet filium. et nuntiantes dicite quia natus est.

Tunc cantor dicat excelsa voce

alleluia, alleluia, iam vere scimus Christum natum in terris, de quo canite, omnes, cum Propheta dicentes:

Puer natus est.’

The Ascension trope is taken from an English troper probably belonging to Christ Church, Canterbury[29].

I return now to the Easter Quem quaeritis. In a few churches this retained its position at the beginning of Mass, either as an Introit trope in the strict sense, or, which comes to much the same thing, as a chant for the procession which [12]immediately preceded. This was the use of the Benedictine abbey of Monte Cassino at the beginning of the twelfth century, of that of St. Denys in the thirteenth[30], and of the church of St. Martin of Tours in the fifteenth[31]. Even in the seventeenth century the Quem quaeritis still appears in a Paris manuscript as a ‘tropus[32],’ and Martene records a practice similar to that of Monte Cassino and St. Denys as surviving at Rheims in his day[33].

But in many tropers, and in most of the later service-books in which it is found, the Quem quaeritis no longer appears to be designed for use at the Mass. This is the case in the only two tropers of English use in which, so far as I know, it comes, the Winchester ones printed by Mr. Frere[34]. I reproduce the earlier of these from the Bodleian manuscript used by him[35].

[13]

‘Angelica de Christi Resurrectione.

Quem quaeritis in sepulchro, Christicolae?

Sanctarum mulierum responsio.

Ihesum Nazarenum crucifixum, o caelicola!

Angelicae voces consolatus.

non est hic, surrexit sicut praedixerat,

ite, nuntiate quia surrexit, dicentes:Sanctarum mulierum ad omnem clerum modulatio:

alleluia! resurrexit Dominus hodie,

leo fortis, Christus filius Dei! Deo gratias dicite, eia!Dicat angelus:

venite et videte locum ubi positus erat Dominus, alleluia! alleluia!

Iterum dicat angelus:

cito euntes dicite discipulis quia surrexit Dominus, alleluia! alleluia!

Mulieri una voce canant iubilantes:

surrexit Dominus de sepulchro,

qui pro nobis pependit in ligno.’

In this manuscript, which is dated by Mr. Frere in 979 or 980, the text just quoted is altogether detached from the Easter day tropes. Its heading is rubricated and immediately follows the tropes for Palm Sunday. It is followed in its turn, under a fresh rubric, by the ceremonies for Holy Saturday, beginning with the Benedictio Cerei. From the second, somewhat later Cambridge manuscript, probably of the early eleventh century, the Holy Saturday ceremonies have disappeared, but the Quem quaeritis still precedes and does not follow the regular Easter tropes, which are headed Tropi in die Christi Resurrectionis[36]. The precise position which the [14]Quem quaeritis was intended to take in the Easter services is not evident from these tropers by themselves. Fortunately another document comes to our assistance. This is the Concordia Regularis, an appendix to the Rule of St. Benedict intended for the use of the Benedictine monasteries in England reformed by Dunstan during the tenth century. The Concordia Regularis was drawn up by Ethelwold, bishop of Winchester, as a result of a council of Winchester held at some uncertain date during the reign of Edgar (959-79); it may fairly be taken for granted that it fixed at least the Winchester custom. I translate the account of the Quem quaeritis ceremony, which is described as forming part, not of the Mass, but of the third Nocturn at Matins on Easter morning[37].

‘While the third lesson is being chanted, let four brethren vest themselves. Let one of these, vested in an alb, enter as though to take part in the service, and let him approach the sepulchre without attracting attention and sit there quietly with a palm in his hand. While the third respond is chanted, let the remaining three follow, and let them all, vested in copes, bearing in their hands thuribles with incense, and stepping delicately as those who seek something, approach the sepulchre. These things are done in imitation of the angel sitting in the monument, and the women with spices coming to anoint the body of Jesus. When therefore he who sits there beholds the three approach him like folk lost and seeking something, let him begin in a dulcet voice of medium pitch to sing Quem quaeritis. And when he has sung it to the end, let the three reply in unison Ihesu Nazarenum. So he, Non est hic, surrexit sicut praedixerat. Ite, nuntiate quia surrexit a mortuis. At the word of this bidding let those three turn to the choir and say Alleluia! resurrexit Dominus! This said, let the one, still sitting there and as if recalling them, say the anthem Venite et videte locum. And saying this, let him rise, and lift the veil, and show them the place bare of the cross, but only the cloths laid there in which the cross was [15]wrapped. And when they have seen this, let them set down the thuribles which they bare in that same sepulchre, and take the cloth, and hold it up in the face of the clergy, and as if to demonstrate that the Lord has risen and is no longer wrapped therein, let them sing the anthem Surrexit Dominus de sepulchro, and lay the cloth upon the altar. When the anthem is done, let the prior, sharing in their gladness at the triumph of our King, in that, having vanquished death, He rose again, begin the hymn Te Deum laudamus. And this begun, all the bells chime out together.’

The liberal scenario of the Concordia Regularis makes plain the change which has come about in the character of the Quem quaeritis since it was first sung by alternating half-choirs as an Introit trope[38]. Dialogued chant and mimetic action have come together and the first liturgical drama is, in all its essentials, complete.

I am not quite satisfied as to the relations of date between the Concordia Regularis and the Winchester tropers, or as to whether the Quem quaeritis was intended in one or both of these manuscripts for use at the Easter Matins[39]. But it is clear that such a use was known in England at any rate before the end of the tenth century. It was also known in France and in Germany: the former fact is testified to by the Consuetudines of the monastery of St. Vito of Verdun[40]; the [16]latter by the occurrence of the Quem quaeritis in a troper of Bamberg, where it has the heading Ad visitandum sepulchrum and is followed by the Matins chant of Te Deum[41].

The heading of the Bamberg version and the detailed description of the Concordia Regularis bring the Quem quaeritis drama into close relations with the Easter ‘sepulchre’[42]. They are indeed the first historical notices of the ceremony so widely popular during the Middle Ages. Some account of the Easter sepulchre must accordingly be inserted here, and its basis shall be the admirably full description of St. Ethelwold[43]. He directs that on Good Friday all the monks shall go discalceati or shoeless from Prime ‘until the cross is adored’[44]. In the principal service of the day, which begins at Nones, the reading of the Passion according to St. John and a long series of prayers are included. Then a cross is made ready and laid upon a cushion a little way in front of the altar. It is unveiled, and the anthem Ecce lignum crucis is sung. The abbot advances, prostrates himself, and chants the seven penitential psalms. Then he humbly kisses the cross. His example is followed by the rest of the monks and by the clergy and congregation. St. Ethelwold proceeds:—

‘Since on this day we celebrate the laying down of the body of our Saviour, if it seem good or pleasing to any to follow on similar lines the use of certain of the religious, which is worthy of imitation for the strengthening of faith in the unlearned vulgar and in neophytes, we have ordered it on this wise. Let a likeness of a sepulchre be made in a vacant part of the altar, and a veil stretched on a ring which may hang there until the adoration of the cross is over. Let the deacons who previously carried the cross come and wrap it in a cloth [17]in the place where it was adored[45]. Then let them carry it back, singing anthems, until they come to the place of the monument, and there having laid down the cross as if it were the buried body of our Lord Jesus Christ, let them say an anthem. And here let the holy cross be guarded with all reverence until the night of the Lord’s resurrection. By night let two brothers or three, or more if the throng be sufficient, be appointed who may keep faithful wake there chanting psalms.’

The ceremony of the burial or Depositio Crucis is followed by the Missa Praesanctificatorum, the Good Friday communion with a host not consecrated that day but specially reserved from Maundy Thursday; and there is no further reference to the sepulchre until the order for Easter day itself is reached, when St. Ethelwold directs that ‘before the bells are rung for Matins the sacristans are to take the cross and set it in a fitting place.’

In the Concordia Regularis, then, the Depositio Crucis is a sequel to the Adoratio Crucis on Good Friday. The latter ceremony, known familiarly to the sixteenth century as ‘creeping to the cross,’ was one of great antiquity. It was amongst the Holy week rites practised at Jerusalem in the fourth century[46], and was at an early date adopted in Rome[47]. But the sepulchre was no primitive part of it[48]; nor is it [18]possible to trace either the use which served St. Ethelwold as a model[49], or the home or date of the sepulchre itself. It is unlikely, however, that the latter originated in England, as it appears almost simultaneously on the continent, and English ritual, in the tenth century, was markedly behind and not in advance of that of France and Germany[50]. St. Ethelwold speaks of it as distinctively monastic but certainly not as universal or of obligation amongst the Benedictine communities for whom he wrote. Nor did the Concordia Regularis lead to its invariable adoption, for when Ælfric adapted St. Ethelwold’s work for the benefit of Eynsham about 1005 he omitted the account of the sepulchre[51], and it is not mentioned in Archbishop Lanfranc’s Benedictine Constitutions of 1075[52]. At a later date it was used by many [19]Benedictine houses, notably by the great Durham Priory[53]; but the Cistercians and the Carthusians, who represent two of the most famous reforms of the order, are said never to have adopted it, considering it incompatible with the austerity of their rule[54]. On the other hand it was certainly not, in mediaeval England, confined to monastic churches. The cathedrals of Salisbury[55], York[56], Lincoln[57], Hereford[58], Wells[59], all of which were served by secular canons, had their sepulchres, and the gradual spread of the Sarum use probably brought a sepulchre into the majority of parish churches throughout the land[60].

There are naturally variations and amplifications of the sepulchre ceremonial as described by St. Ethelwold to be recorded. The Depositio Crucis, instead of preceding the Missa Praesanctificatorum, was often, as in the Sarum use, [20]transferred to the end of Vespers, which on Good Friday followed the Missa without a break[61]. The Elevatio regularly took place early on Easter morning before Matins. The oldest custom was doubtless that of the Regularis Concordia, according to which the cross was removed from the sepulchre secretly by the sacristans, since this is most closely in agreement with the narrative of the gospels. But in time the Elevatio became a function. The books of Salisbury and York provide for it a procession with the antiphons Christus resurgens and Surrexit Dominus. Continental rituals show considerable diversity of custom[62]. Perhaps the most elaborate ceremonials are those of Augsburg and Würzburg, printed by Milchsack. In these the Tollite portas procession, which we have already found borrowed from the dedication of churches for Palm Sunday, was adapted to Easter day[63]. But the old tradition was often preserved by the exclusion or only partial admission of the populace to the Elevatio. In the Augsburg ritual just quoted, all but a few privileged persons are kept out until the devil has been expelled and the doors solemnly opened[64]. A curious light is thrown upon this by a decree of the synod of Worms in 1316, which orders that the ‘mystery of the resurrection’ shall be performed before the plebs comes [21]into the church, and gives as a reason the crowds caused by a prevalent superstition that whoever saw the crucifix raised would escape for that year ‘the inevitable hour of death’[65].

A widespread if not quite universal innovation on the earlier use was the burial, together with the cross or crucifix, of a host, which was consecrated, like that used in the Missa Praesanctificatorum, on Maundy Thursday. This host was laid in a pyx[66], monstrance[67], or cup[68], and sometimes in a special image, representing the risen Christ with the cross or labarum in his hands, the breast of which held a cavity covered with beryl or crystal[69]. Within the sepulchre both the host and the crucifix were laid upon or wrapped in a fine linen napkin.

The actual structure of the sepulchre lent itself to considerable variety. St. Ethelwold’s assimilatio quaedam sepulchri upon a vacant part of the altar may have been formed, like that at Narbonne several centuries later, by laying together some of the silver service-books[70]. There are other examples of a sepulchre at an altar, and it is possible that in some of [22]these the altar itself may have been hollow and have held the sacred deposit. Sometimes the high altar was used, but a side-altar was naturally more convenient, and at St. Lawrence’s, Reading, the ‘sepulchre awlter’ was in the rood-loft[71]. The books were a primitive expedient. More often the sepulchre was an elaborate carved shrine of wood, iron, or silver. If this did not stand upon the altar, it was placed on the north side of the sanctuary or in a north choir aisle. In large churches the crypt was sometimes thought an appropriate site[72]. Often the base of the sepulchre was formed by the tomb of a founder or benefactor of the church, and legacies for making a structure to serve this double purpose are not uncommon in mediaeval wills. Such tombs often have a canopied recess above them, and in these cases the portable shrine may have been dispensed with. Many churches have a niche or recess, designed of sole purpose for the sepulchre[73]. Several of these more elaborate sepulchres are large enough to be entered, a very convenient arrangement for the Quem quaeritis[74]; a few of them are regular chapels, more than one of which is an exact reproduction of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem, and is probably due to the piety of some local pilgrim[75]. Wood, metal, or stone, permanent or movable, the sepulchre was richly adorned with paintings and carvings of the Passion and the Resurrection, with Easter texts, with figures of censer-swinging angels and sleeping knights[76]. A seal was, at least [23]at Hereford and in Hungary, set upon it[77]. A canopy was hung over it and upon it lay a pall, also a favourite object for a pious legacy. Similar legacies might meet the expense of the ‘sepulchre light,’ which was kept burning from Good Friday to Easter morning, and was only extinguished for a few minutes on Easter Saturday to be re-lit from the freshly blessed ‘new fire[78].’ Or the light might be provided by one of the innumerable guilds of the Middle Ages, whose members, perhaps, also undertook the devout duty of keeping the two nights’ vigil before the sepulchre[79]. This watch was important. The Augsburg ritual already quoted makes the possibility of arranging it a condition of setting up the sepulchre at all[80]. The watchers sang psalms, and it is an example of the irrepressible mediaeval tendency to mimesis that they were sometimes accoutred like the knights of Pilate[81]. After the Elevatio, the crucifix seems to have been placed upon a side-altar and visited by processions in Easter, while the host was reserved in a tabernacle. The Sarum Custumary directs that the empty sepulchre shall be daily censed at Vespers and removed [24]on the Friday in Easter week before Mass[82]. Naturally there was some division of opinion at the Reformation as to the precise spiritual value of the Easter sepulchre. While Bishop Hooper and his fellow pulpiters were outspoken about the idolatrous cult of a ‘dead post[83],’ the more conservative views which ruled in the latter years of Henry VIII declared the ceremony to be ‘very laudable’ and ‘not to be contemned and cast away[84].’ The Cromwellian Injunctions of 1538 sanctioned the continued use of the sepulchre light, and by implication of the sepulchre itself. The Edwardine Injunctions of 1547 suppressed the sepulchre light and were certainly interpreted by Cranmer and others as suppressing the sepulchre[85]. The closely related ‘creeping to the cross’ was forbidden by proclamation in 1548; and in 1549, after the issue of the first Act of Uniformity and the first Prayer Book of Edward VI, the disallowance of both ceremonies was legalized, or renewed by Articles for the visitation of that year[86]. Payments for the breaking up of the sepulchre now appear in many churchwardens’ accounts, to be complicated before long by payments for setting the sepulchre up again, in consequence of an order by Queen Mary in 1554[87]. In the same year the crucifix and pyx were missing out of the sepulchre at St. Pancras’ Church in Cheapside, when the priests came for the Elevatio on Easter morning, and one Marsh was committed to the Counter for [25]the sacrilege[88]. The Elizabethan Injunctions of 1559, although they do not specifically name the sepulchre, doubtless led to its final disappearance[89]. In many parts of the continent it naturally lasted longer, but the term ‘visiting sepulchres’ seems in modern times to have been transferred to the devotion paid to the reserved host on Maundy Thursday[90].

I now return to the Quem quaeritis in the second stage of its evolution, when it had ceased to be an Introit trope and had become attached to the ceremony of the sepulchre. Obviously it is not an essential part of that ceremony. The Depositio and Elevatio mutually presuppose each other and, together, are complete. For the dramatic performance, as described by St. Ethelwold, the clergy, having removed the cross at the beginning of Matins, revisited the empty sepulchre quite at the close of that service, after the third respond[91], between which and the normal ending of Matins, the Te Deum, the Quem quaeritis was intercalated. The fact that the Maries bear censers instead of or in addition to the scriptural spices, suggests that this Visitatio grew out of a custom of censing the sepulchre at the end of Matins as well as of Evensong[92]. But the Visitatio could easily be omitted, and in fact it was omitted in many churches where the Depositio and Elevatio were in use. The Sarum books, for instance, do not in any way prescribe it. On the other hand, there were probably a few churches [26]which adopted the Visitatio without the more important rite. Bamberg seems to have been one of these, and so possibly were Sens, Senlis, and one or two others in which the Quem quaeritis is noted as taking place at an altar[93]. However, whether there was a real sepulchre or not, the regular place of the Quem quaeritis was that prescribed for it by St. Ethelwold, between the third respond and the Te Deum at Matins. It has been found in a very large number of manuscripts, and in by far the greater part of them it occupies this position[94]. In the rest, with the exception of a completely anomalous example from Vienne[95], it is either a trope[96], or else is merged [27]with or immediately follows the Elevatio before Matins[97]. The evidence of the texts themselves is borne out by Durandus, who is aware of the variety of custom, and indicates the end of Matins as the proprior locus[98].

No less difficult to determine than the place and time at which the Easter sepulchre itself was devised, are those at which the Quem quaeritis, attached to it, stood forth as a drama. That the two first appear together can hardly be taken as evidence that they came into being together. The predominance of German and French versions of the Quem quaeritis may suggest an origin in the Frankish area: and if the influence of the Sarum use and the havoc of service-books at the Reformation may between them help to account for the comparative rarity of the play in these islands, no such explanation is available for Italy and Spain. The development of the religious drama in the peninsulas, especially in Italy, seems to have followed from the beginning lines somewhat distinct from those of north-western Europe. But between France and Germany, as between France and England, literary influences, so far as clerkly literature goes, moved freely: nor is it possible to isolate the centres and lines of diffusion of that gradual process of accretion and development through which the Quem quaeritis gave ever fuller and fuller expression to the dramatic instincts by which it was prompted. The clerici vagantes were doubtless busy agents in carrying new motives and amplifications of the text from one church to another. Nor should it be forgotten that, numerous as are the versions preserved, those which have perished must have been more numerous still, so that, if all [28]were before us, the apparent anomaly presented by the occurrence of identical features in, for instance, the plays from Dublin and Fleury, and no others, would not improbably be removed. The existence of this or that version in the service-books of any one church must depend on divers conditions; the accidents of communication in the first place, and in the second the laxity or austerity of governing bodies at various dates in the licensing or pruning of dramatic elaboration. The simplest texts are often found in the latest manuscripts, and it may be that because their simplicity gave no offence they were permitted to remain there. A Strassburg notice suggests that the ordering of the Quem quaeritis was a matter for the discretion of each individual parish, in independence of its diocesan use[99]; while the process of textual growth is illustrated by a Laon Ordinarium, in which an earlier version has been erased and one more elaborate substituted[100].

Disregarding, however, in the main the dates of the manuscripts, it is easy so to classify the available versions as to mark the course of a development which was probably complete by the middle of the twelfth and certainly by the thirteenth century. This development affected both the text and the dramatic interest of the play. The former is the slighter matter and may be disposed of first[101].

The kernel of the whole thing is, of course, the old St. Gall trope, itself a free adaptation from the text of the Vulgate, and the few examples in which this does not occur must be regarded as quite exceptional[102]. The earliest additions were taken from anthems, which already had their place [29]in the Easter services, and which in some manuscripts of the Gregorian Antiphonarium are grouped together as suitable for insertion wherever may be desired[103]. So far the text keeps fairly close to the words of Scripture, and even where the limits of the antiphonary are passed, the same rule holds good. In time, however, a freer dramatic handling partly establishes itself. Proses, and even metrical hymns, beginning as choral introductions, gradually usurp a place in the dialogue, and in the latest versions the metrical character is very marked. By far the most important of these insertions is the famous prose or sequence Victimae paschali, the composition of which by the monk Wipo of St. Gall can be pretty safely dated in the second quarter of the eleventh century[104]. It goes as follows:

Originally written as an Alleluia trope or sequence proper, a place which it still occupies in the reformed Tridentine liturgy[105], the Victimae paschali cannot be shown to have made its way into the Quem quaeritis until the thirteenth century[106]. But it occurs in about a third of the extant versions, sometimes as a whole, sometimes with the omission of the first three sentences, which obviously do not lend themselves as well as the rest to dramatic treatment. When introduced, these three sentences are sung either by the choir or by the Maries: the other six fall naturally into dialogue.

The Victimae paschali is an expansion of the text of the Quem quaeritis, but it does not necessarily introduce any new dramatic motive. Of such there were, from the beginning, at least two. There was the visit of the Maries to the sepulchre and their colloquy with the angel; and there was the subsequent announcement of the Resurrection made by them in pursuance of the divine direction. Each has its appropriate action: in the one case the lifting of the pall and discovery of the empty sepulchre, in the other the display by the Maries of the cast-off grave-clothes, represented by a linteum, in token of the joyful event. It is to this second scene, if the term may be used of anything so rudimentary, that the Victimae paschali attaches itself. The dialogue of it is between the Maries and the choir, who stand for the whole body of disciples, or sometimes two singers, who are their spokesmen[107]. A new scene is, however, clearly added to [31]the play, when these two singers not only address the Maries, but themselves pay a visit to the sepulchre. Now they represent the apostles Peter and John. In accordance with the gospel narrative John outstrips Peter in going to the sepulchre, but Peter enters first: and the business of taking up the linteum and displaying it to the other disciples is naturally transferred to them from the Maries. The apostle scene first makes its appearance in an Augsburg text of the end of the eleventh century, or the beginning of the twelfth[108]. It occurs in rather more than half the total number of versions. These are mainly German, but the evidence of Belethus is sufficient to show that it was not unknown in twelfth-century France[109]. The addition of the apostle scene completed the evolution of the Easter play for the majority of churches. There were, however, a few in which the very important step was taken of introducing the person of the risen Christ himself; and this naturally entailed yet another new scene. Of this type there are fifteen extant versions, coming from one Italian, four French, and four German churches[110]. The earliest is of the twelfth century, from a Prague convent. The new scene closely follows the Scripture narrative. Mary [32]Magdalen remains behind the other Maries at the sepulchre. The Christ appears; she takes him for the gardener, and he reveals himself with the Noli me tangere. Mary returns with the new wonder to the choir. This is the simplest version of the new episode. It occurs in a play of which the text is purely liturgical, and does not even include the Victimae paschali. A somewhat longer one is found in a Fleury play, which is in other respects highly elaborate and metrical. Here the Christ appears twice, first disguised in similitudinem hortolani, afterwards in similitudinem domini with the labarum or resurrection banner. The remaining versions do not depart widely from these two types, except that at Rouen and Mont St.-Michel, the Christ scene takes place, not at the sepulchre but at the altar, and at Cividale in a spot described as the ortus Christi[111].

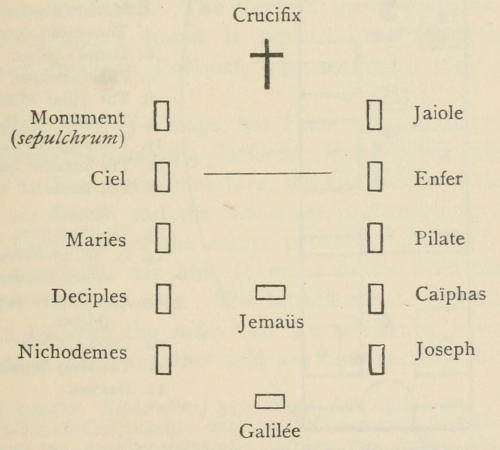

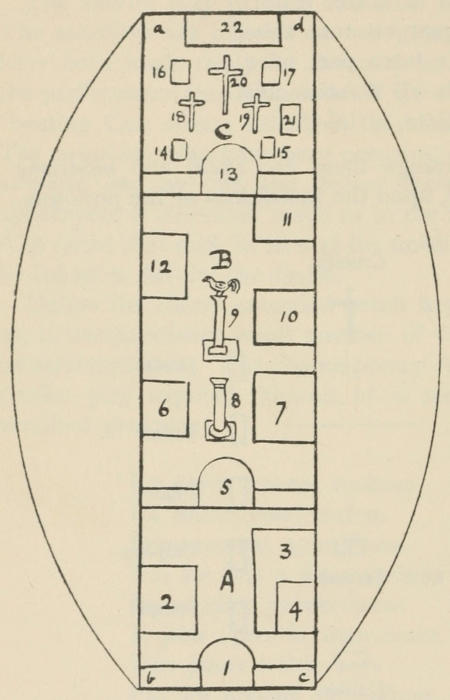

The formal classification, then, of the versions of the Quem quaeritis, gives three types. In the first, the scenes between the Maries and the angel, and between the Maries and the choir, are alone present; in the second the apostle scene is added to these; the third, of which there are only fifteen known examples, is distinguished by the presence of the Christ scene. In any one of these types, the Victimae paschali and other proses and hymns may or may not be found[112]. And it must now be added that it is on the presence of these that the greater or less development of lyric feeling, as distinct from dramatic action, in the play depends. The metrical hymns in particular, when they are not merely choral overtures, are often of the nature of planctus or laments put in the mouths of the Maries as they approach the sepulchre or at some other appropriate moment. These planctus add greatly to the vividness and humanity of the play, and are thus an important step in the dramatic evolution. The use of them [33]may be illustrated by that of the hymn Heu! pius pastor occiditur in the Dublin version found by Mr. Frere and printed, after a different text from his, in an appendix[113]. This play has not the Christ scene, and belongs, therefore, to the second type of Quem quaeritis, but, in other respects, including the planctus, it closely resembles the Fleury version described above. Another planctus, found in plays of the third type from Engelberg, Nuremberg, Einsiedeln, and Cividale, is the Heu nobis! internas mentes[114]; a third, the Heu! miserae cur contigit, seems to have been interpolated in the Heu! pius pastor at Dublin; a fourth, the Omnipotens pater altissime, with a refrain Heu quantus est dolor noster! is found at places so far apart as Narbonne and Prague[115]: and a fifth, Heu dolor, heu quam dira doloris angustia! is also in the Fleury text[116].

Another advance towards drama is made in four Prague versions of the third type by the introduction of an episode for which there is no Scriptural basis at all. On their way to the sepulchre, the Maries stop and buy the necessary spices of a spice-merchant or unguentarius. In three thirteenth-century texts the unguentarius is merely a persona muta; in one of the fourteenth he is given four lines[117]. The unguentarius was destined to become a very popular character, and to afford much comic relief in the vernacular religious drama of Germany. Nor can it be quite confidently said that his appearance in these comparatively late liturgical plays is a natural development and not merely an instance of reaction by the vernacular stage.

[34]

The scenic effect of the Quem quaeritis can be to some extent gathered from the rubrics, although these are often absent and often not very explicit, being content with a general direction for the performers to be arrayed in similitudinem mulierum or angelorum or apostolorum, as the case may be. The setting was obviously simple, and few properties or costumes beyond what the vestments and ornaments of the church could supply were used. The Maries had their heads veiled[118], and wore surplices, copes, chasubles, dalmatics, albs, or the like. These were either white or coloured. At Fécamp one, presumably the Magdalen, was in red, the other two in white[119]. The thuribles which, as already pointed out, they carried, were sometimes replaced by boxes or vases representing the ointment and spices[120]. Sometimes also they carried, or had carried before them, candles. Two or three rubrics direct them to go pedetemptim, as sad or searching[121]. They were generally three in number, occasionally two, or one only. The angels, or angel, as the case might be, sat within the sepulchre or at its door. They, too, had vestments, generally white, and veiled or crowned heads. At Narbonne, and probably elsewhere, they had wings[122]. They held lights, a palm, or an ear of corn, symbolizing the Resurrection[123]. The apostles are rarely described; the ordinary priestly robes doubtless sufficed. At Dublin, St. John, in white, held a palm, and St. Peter, in red, the keys[124]. In the earliest Prague version of the Christ scene, the Christ seems to be represented by one of the angels[125]. At Nuremberg the dominica persona has a crown and bare feet[126]. At Rouen he holds a cross, and [35]though there is a double appearance, there is no hint of any change of costume[127]. But at Coutances and Fleury the first appearance is as hortulanus, indicated perhaps by a spade, which is exchanged on the second for the cross[128].

It must be borne in mind that the Quem quaeritis remained imperfectly detached from the liturgy, out of which it arose. The performers were priests, or nuns, and choir-boys. The play was always chanted, not spoken[129]. It was not even completely resolved into dialogue. In many quite late versions narrative anthems giving the gist of each scene are retained, and are sung either by the principal actors or by the choir, which thus, as in the hymns or proses which occur as overtures[130], holds a position distinct from the part which it takes as representing the disciples[131]. Finally the whole performance ends in most cases with the Te Deum laudamus, and thus becomes a constituent part of Matins, which normally comes to a close with that hymn. The intervention of the congregation, with its Easter hymn Christ ist erstanden, seems to lie outside the main period of the evolution of the Quem quaeritis. I only find one example so early as the thirteenth century[132]. [36]It is in quite late texts also that certain other Easter motives have become attached to the play. The commonest of these are the whispered greeting of Surrexit Christus and the kiss of peace, which have been noted elsewhere as preceding Matins[133]. At Eichstädt, in 1560, is an amusing direction, which Mr. Collins would have thought very proper, that the pax is to be given to the dominus terrae, si ibi fuerit, before the priest. The same manuscript shows a curious combination of the Quem quaeritis with the irrepressible Tollite portas ceremony[134]. Another such is found at Venice[135]. But this is as late as the eighteenth century, to which also belongs the practice at Angers described by De Moleon, according to which the Maries took up from the sepulchre with the linteum two large Easter eggs—deux œufs d’autruche[136].

Besides the Quem quaeritis, Easter week had another liturgical drama in the Peregrini or Peregrinus[137]. This was established by the twelfth century. It was regularly played at Lichfield[138], but no text is extant from England, except a late transitional one, written partly in the vernacular[139]. France affords four texts, from Saintes[140], Rouen[141], [37]Beauvais[142], and Fleury[143]. The play is also recorded at Lille[144]. In Germany it is represented by a recently-discovered fragment of the famous early thirteenth-century repertory of the scholares vagantes from the Benedictbeuern monastery[145]. The simplest version is that of Saintes, in which the action is confined to the journey to Emmaus and the supper there. The Rouen play is on the same lines, but at the close the disciples are joined by St. Mary Magdalen, and the Victimae paschali is sung. The Benedictbeuern play similarly ends with the introduction of the Virgin and two other Maries to greet the risen Christ. But here, and in the Beauvais and Fleury plays, a distinct scene is added, of which the subject is the incredulity of Thomas and the apparition to him. It is, I think, a reasonable conjecture that the Peregrini, in which the risen Christ is a character, was not devised until he had already been introduced into the later versions of the Quem quaeritis. Indeed the Fleury Peregrini, with its double appearance and change of costume for Christ, seems clearly modelled on the Fleury Quem quaeritis. But the lesser play has its own proper and natural place in the Easter week services. It is attached to the Processio ad fontes which is a regular portion, during that season, of Vespers[146]. The Christ with the Resurrection cross is personated by the priest who [38]normally accompanies the procession cum cruce. At Rouen the play was a kind of dramatization of the procession itself[147]; at Lille it seems to have had the same position; at Saintes and Beauvais it preceded the Magnificat and Oratio or Collecta, after which the procession started. In the remaining cases there is no indication of the exact time for the Peregrini. The regular day for it appears to have been the Monday in Easter week, of the Gospel for which the journey to Emmaus is the subject; but at Fleury it was on the Tuesday, when the Gospel subject is the incredulity of Thomas. At Saintes, a curious rubric directs the Christ during the supper at Emmaus to divide the ‘host’ among the Peregrini. It seems possible that in this way a final disposal was found for the host which had previously figured in the Depositio and Elevatio of the sepulchre ceremony.

A long play, probably of Norman origin and now preserved in a manuscript at Tours, represents a merging of the Elevatio, the Quem quaeritis, and the Peregrini[148]. The beginning is imperfect, but it may be conjectured from a fragment belonging to Klosterneuburg in Germany, that only a few lines are lost[149]. Pilate sets a watch before the sepulchre. An angel sends lightning, and the soldiers fall as if dead[150]. Then come the Maries, with planctus. There is a scene with the unguentarius or mercator, much longer than that at Prague, followed by more planctus. After the Quem quaeritis, the soldiers announce the event to Pilate. A planctus by the [39]Magdalen leads up to the apparition to her. The Maries return to the disciples. Christ appears to the disciples, then to Thomas, and the Victimae paschali and Te Deum conclude the performance. A fragment of a very similar play, breaking off before the Quem quaeritis, belongs to the Benedictbeuern manuscript already mentioned[151].

It is clear from the rubrics that the Tours play, long as it is, was still acted in church, and probably, as the Te Deum suggests, at the Easter Matins[152]. Certainly this was the case with the Benedictbeuern play. In a sense, these plays only mark a further stage in the process of elaboration by which the fuller versions of the Quem quaeritis proper came into being. But the introduction at the beginning and end of motives outside the events of the Easter morning itself points to possibilities of expansion which were presently realized, and which ultimately transformed the whole character of the liturgical drama. All the plays, however, which have so far been mentioned, are strictly plays of the Resurrection. Their action begins after the Burial of Christ, and does not stretch back into the events of the Passion. Nor indeed can the liturgical drama proper be shown to have advanced beyond a very rudimentary representation of the Passion. This began with the planctus, akin to those of the Quem quaeritis, which express the sorrows of the Virgin and the Maries and St. John around the cross[153]. Such planctus exist both in Latin and [40]the vernacular. The earliest are of the twelfth century. Several of them are in dialogue, in which Christ himself occasionally takes part, and they appear to have been sung in church after Matins on Good Friday[154]. The planctus must be regarded as the starting-point of a drama of the Passion, which presently established itself beside the drama of the Resurrection. This process was mainly outside the churches, but an early and perhaps still liturgical stage of it is to be seen in the ludus breviter de passione which precedes the elaborated Quem quaeritis of the Benedictbeuern manuscript, and was probably treated as a sort of prologue to it. The action extends from the preparation for the Last Supper to the Burial. It is mainly in dumb-show, and the slight dialogue introduced is wholly out of the Vulgate. But at one point occurs the rubric Maria planctum faciat quantum melius potest, and a later hand has inserted out of its place in the text the most famous of all the laments of the Virgin, the Planctus ante nescia[155].

[41]

The ‘Twelve days’ of the Christmas season are no less important than Easter itself in the evolution of the liturgical drama. I have mentioned in the last chapter a Christmas trope which is evidently based upon the older Easter dialogue. Instead of Quem quaeritis in sepulchro, o Christicolae? it begins Quem quaeritis in praesepe, pastores, dicite? It occurs in eleventh- and twelfth-century tropers from St. Gall, Limoges, St. Magloire, and Nevers. Originally it was an Introit trope for the third or ‘great’ Mass. In a fifteenth-century breviary from Clermont-Ferrand it has been transferred to Matins, where it follows the Te Deum; and this is precisely the place in the Christmas services occupied, at Rouen, by a liturgical drama known as the Officium Pastorum, which appears to have grown out of the Quem quaeritis in praesepe? by a process analogous to that by which the Easter drama grew out of the Quem quaeritis in sepulchro[156]? A praesepe or ‘crib,’ covered by a curtain, was made ready behind the altar, and in it was placed an image of the Virgin. After the Te Deum five canons or vicars, representing the shepherds, approached the great west door of the choir. A boy in similitudinem angeli perched in excelso sang them the ‘good tidings,’ and a number of others in voltis ecclesiae took up the Gloria in excelsis. The shepherds, singing a hymn, advanced to the praesepe. Here they were met with the Quem quaeritis by two priests quasi obstetrices[157]. The dialogue [42]of the trope, expanded by another hymn during which the shepherds adore, follows, and so the drama ends. But the shepherds ‘rule the choir’ throughout the Missa in Gallicantu immediately afterwards, and at Lauds, the anthem for which much resembles the Quem quaeritis itself[158]. The misterium pastorum was still performed at Rouen in the middle of the fifteenth century, and at this date the shepherds, cessantibus stultitiis et insolenciis, so far as this could be ensured by the chapter, took the whole ‘service’ of the day, just as did the deacons, priests, and choir-boys during the triduum[159].

If the central point of the Quem quaeritis is the sepulchrum, that of the Pastores is the praesepe. In either case the drama, properly so called, is an addition, and by no means an invariable one, to the symbolical ceremony. The Pastores may, in fact, be described, although the term does not occur in the documents, as a Visitatio praesepis. The history of the praesepe can be more definitely stated than that of the sepulchrum. It is by no means extinct. The Christmas ‘crib’ or crèche, a more or less realistic representation of the Nativity, with a Christ-child in the manger, a Joseph and Mary, and very often an ox and an ass, is a common feature in all Catholic countries at Christmas time[160]. At Rome, in particular, the esposizione del santo bambino takes place with great ceremony[161]. A tradition ascribes the first presepio known in Italy to St. Francis, who is said to have invented it at Greccio in 1223[162]. But this is a mistake. The custom is [43]many centuries older than St. Francis. Its Roman home is the church of S. Maria Maggiore or Ad Praesepe, otherwise called the ‘basilica of Liberius.’ Here there was in the eighth century a permanent praesepe[163], probably built in imitation of one which had long existed at Bethlehem, and to which an allusion is traced in the writings of Origen[164]. The praesepe of S. Maria Maggiore was in the right aisle. When the Sistine chapel was built in 1585-90 it was moved to the crypt, where it may now be seen. This church became an important station for the Papal services at Christmas. The Pope celebrated Mass here on the vigil, and remained until he had also celebrated the first Mass on Christmas morning. The bread was broken on the manger itself, which served as an altar. At S. Maria Maggiore, moreover, is an important relic, in some boards from the culla or cradle of Christ, which are exposed on the presepio during Christmas[165]. The presepio of S. Maria Maggiore became demonstrably the model for other similar chapels in Rome[166], and doubtless for the more temporary structures throughout Italy and western Europe in general.

In the present state of our knowledge it is a little difficult to be precise as to the range or date of the Pastores. The only full mediaeval Latin text, other than that of Rouen, which has come to light, is also of Norman origin, and is still unprinted[167]. In the eighteenth century the play survived at Lisieux and Clermont[168]. The earliest Rouen manuscript is of the thirteenth century, and the absence of any reference to [44]the Officium Pastorum by John of Avranches, who writes primarily of Rouen, and who does mention the Officium Stellae, makes it probable that it was not there known about 1070[169]. Its existence, however, in England in the twelfth century is shown by the Lichfield Statutes of 1188-98, and on the whole it is not likely to have taken shape later than the eleventh. Very likely it never, as a self-contained play, acquired the vogue of the Quem quaeritis. As will be seen presently, it was overshadowed and absorbed by rivals. I find no trace of it in Germany, where the praesepe became a centre, less for liturgical drama, than for carols, dances, and ‘crib-rocking[170].’

Still rarer than the Pastores is the drama, presumably belonging to Innocents’ day, of Rachel. It is found in a primitive form, hardly more than a trope, in a Limoges manuscript of the eleventh century. Here it is called Lamentatio Rachel, and consists of a short planctus by Rachel herself, and a short reply by a consoling angel. There is nothing to show what place it occupied in the services[171].

The fact is that both the Pastores and the Rachel were in many churches taken up into a third drama belonging to the Epiphany. This is variously known as the Tres Reges, the Magi, Herodes, and the Stella. It exists in a fair number of different but related forms. Like the Quem quaeritis and the Pastores, it had a material starting-point, in the shape of a star, lit with candles, which hung from the roof of the church, and could sometimes be moved, by a simple mechanical device, from place to place[172]. As with the Quem quaeritis, [45]the development of the Stella must be studied without much reference to the relative age of the manuscripts in which it happens to be found. But it was probably complete by the end of the eleventh century, since manuscripts of that date contain the play in its latest forms[173].

The simplest version is from Limoges[174]. The three kings enter by the great door of the choir singing a prosula. They show their gifts, the royal gold, the divine incense, the myrrh for funeral. Then they see the star, and follow it to the high altar. Here they offer their gifts, each contained in a gilt cup, or some other iocale pretiosum, after which a boy, representing an angel, announces to them the birth of Christ, and they retire singing to the sacristy. The text of this version stands by itself: nearly all the others are derived from a common tradition, which is seen in its simplest form at Rouen[175]. In the Rouen Officium Stellae, the three kings, coming respectively from the east, north, and south of the church, meet before the altar. One of them points to the star with his stick, and they sing:

[46]

They kiss each other and sing an anthem, which occurs also in the Limoges version: Eamus ergo et inquiramus eum, offerentes ei munera; aurum thus et myrrham. A procession is now formed, and as it moves towards the nave, the choir chant narrative passages, describing the visit of the Magi to Jerusalem and their reception by Herod. Meanwhile a star is lit over the altar of the cross where an image of the Virgin has been placed. The Magi approach it, singing the passage which begins Ecce stella in Oriente. They are met by two in dalmatics, who appear to be identical with the obstetrices of the Rouen Pastores. A dialogue follows:

‘Qui sunt hi qui, stella duce, nos adeuntes inaudita ferunt.

Magi respondeant:

nos sumus, quos cernitis, reges Tharsis et Arabum et Saba, dona ferentes Christo, regi nato, Domino, quem, stella deducente, adorare venimus.

Tunc duo Dalmaticati aperientes cortinam dicant:

ecce puer adest quem queritis, Iam properate adorate, quia ipse est redemptio mundi.

Tunc procidentes Reges ad terram, simul salutent puerum, ita dicentes:

salve, princeps saeculorum.

Tunc unus a suo famulo aurum accipiat et dicat:

suscipe, rex, aurum.

Et offerat.

Secundus ita dicat et offerat:

tolle thus, tu, vere Deus.

Tercius ita dicat et offerat:

mirram, signum sepulturae.’

Then the congregation make their oblations. Meanwhile the Magi pray and fall asleep. In their sleep an angel warns them to return home another way. The procession returns up a side aisle to the choir; and the Mass, in which the Magi, like the shepherds on Christmas day, ‘rule the choir,’ follows.

In spite of the difference of text the incidents of the Rouen and Limoges versions, except for the angelic warning introduced at Rouen, are the same. There was a dramatic advance [47]when the visit to Jerusalem, instead of being merely narrated by the choir, was inserted into the action. In the play performed at Nevers[176], Herod himself, destined in the fullness of time to become the protagonist of the Corpus Christi stage, makes his first appearance. There are two versions of the Nevers play. In the earlier the new scene is confined to a colloquy between Herod and the Magi:

‘[Magi.] Vidimus stellam eius in Oriente, et agnovimus regem regum esse natum.

[Herodes.] regem quem queritis natum stella quo signo didicistis? Si illum regnare creditis, dicite nobis.

[Magi.] illum natum esse didicimus in Oriente stella monstrante.

[Herodes.] ite et de puero diligenter investigate, et inventum redeuntes mihi renuntiate.’

The later version adds two further episodes. In one a nuntius announces the coming of the Magi, and is sent to fetch them before Herod: in the other Herod sends his courtiers for the scribes, who find a prophecy of the birth of the Messiah in Bethlehem. Obviously the Herod scene gives point to the words at the end of the Rouen play, in which the angel bids the Magi to return home by a different way.

At Compiègne the action closes with yet another scene, in which Herod learns that the Magi have escaped him[177].

‘Nuncius. Delusus es domine, magi viam redierunt aliam.

[Herodes. incendium meum ruina extinguam[178].]

[48]

Armiger. decerne, domine, vindicari iram tuam, et stricto mucrone quaerere iube puerum, forte inter occisos occidetur et ipse.

Herodes. indolis eximiae pueros fac ense perire.

Angelus. sinite parvulos venire ad me, talium est enim regnum caelorum.’

In a Norman version which has the same incidents as the Compiègne play, but in parts a different text, the armiger is the son of Herod, and the play ends with Herod taking a sword from a bystander and brandishing it in the air[179]. Already he is beginning to tear a passion to tatters in the manner that became traditionally connected with his name. Another peculiarity of this Norman version is that the Magi address Herod in an outlandish jargon, which seems to contain fragments of Hebrew and Arabic speech.

The play of the Stella must now, perhaps, be considered, except so far as mere amplifications of the text are concerned, strictly complete. But another step was irresistibly suggested by the course it had taken. The massacre of the Innocents, although it lay outside the range of action in which the Magi themselves figured, could be not merely threatened but actually represented. This was done at Laon[180]. The cruel suggestion of Archelaus is carried out. The Innocents come in singing and bearing a lamb. They are slain, and the play ends with a dialogue, like that of the distinct Limoges planctus, between the lamenting Rachel and an angelic consolatrix.

The absorption of the motives proper to other feasts of the Twelve nights into the Epiphany play has clearly begun. A fresh series of examples shows a similar treatment of the Pastores. At Strassburg the Magi, as they leave Herod, meet the shepherds returning from Bethlehem:

[49]

This, however, is not taken from the Pastores itself, but from the Christmas Lauds antiphon[181]. Its dramatic use may be compared with that of the Victimae paschali in the Quem quaeritis. In versions from Bilsen[182] near Liège and from Mans[183], on the other hand, although the meeting of the Magi and the shepherds is retained, a complete Pastores, with the angelic tidings and the adoration at the praesepe, forms the first part of the office, before the Magi are introduced at all.

The Strassburg, Bilsen, and Mans plays have not the Rachel, although the first two have the scene in which the nuntius informs Herod that the Magi have deceived him. A further stage is reached when, as at Freising and at Fleury, the Pastores, Stella and Rachel all coalesce in a single, and by this time considerable, drama. The Freising texts, of which there are two, are rather puzzling[184]. The first closely resembles the plays of the group just described. It begins with a short Pastores, comprising the angelic tidings only. Then the scenes between the Magi and Herod are treated at great length. The meeting of the Magi and the shepherds is followed by the oblation, the angelic warning, and the return of the [50]messenger to Herod. In the second Freising text, which is almost wholly metrical, the Pastores is complete. It is followed by a quite new scene, the dream of Joseph and his flight into Egypt. Then come successively the scene of fury at court, the massacre, the planctus and consolation of Rachel. Clearly this second text, as it stands, is incomplete. The Magi are omitted, and the whole of the latter part of the play is consequently rendered meaningless. But it is the Magi who are alone treated fully in the first Freising text. I suggest, therefore, that the second text is intended to supplement and not to replace the first. It really comprises two fragments: one a revision of the Pastores, the other a revision of the closing scene and an expansion of it by a Rachel.

As to the Fleury version there can be no doubt whatever[185]. The matter is, indeed, arranged in two plays, a Herodes and an Interfectio Puerorum, each ending with a Te Deum; and the performance may possibly have extended over two days. But the style is the same throughout and the episodes form one continuous action. It is impossible to regard the Interfectio Puerorum as a separate piece from the Herodes, acted a week earlier on the feast of the Innocents; for into it, after the first entry of the children with their lamb, gaudentes per monasterium, come the flight into Egypt, the return of the nuntius, and the wrath of Herod, which, of course, presuppose the Magi scenes. Another new incident is added at the end of the Fleury play. Herod is deposed and Archelaus set up; the Holy Family return from Egypt, and settle in the parts of Galilee[186].

I have attempted to arrange the dozen or so complete Epiphany plays known to scholars in at least the logical order of their development. There are also three fragments, which fit readily enough into the system. Two, from a Paris manuscript and from Einsiedeln, may be classed respectively with the [51]Compiègne and Strassburg texts[187]. The third, from Vienne, is an independent version, in leonine hexameters, of the scene in which the Magi first sight the star, a theme common to all the plays except that of Limoges[188]. I do not feel certain that this fragment is from a liturgical drama at all.

The textual development of the Stella is closely parallel to that of the Quem quaeritis. The more primitive versions consist of antiphons and prose sentences based upon or in the manner of the Scriptures. The later ones, doubtless under the influence of wandering scholars, become increasingly metrical. The classical tags, from Sallust and Virgil, are an obvious note of the scholarly pen. With the exception of that from Limoges, all the texts appear to be derived by successive accretions and modifications from an archetype fairly represented at Rouen. The Bilsen text and the Vienne fragment have been freely rewritten, and the process of rewriting is well illustrated by the alternative versions found side by side in the later Nevers manuscript. With regard to the place occupied by the Stella in the Epiphany services, such manuscripts as give any indications at all seem to point to a considerable divergence of local use. At Limoges and Nevers, the play was of the nature of a trope to the Mass, inserted in the former case at the Offertorium, in the latter at the Communio[189]. At Rouen the Officium followed Tierce, and preceded the ordinary procession before Mass. At Fleury the use of the Te Deum suggests that it was at Matins; at Strassburg it followed the Magnificat at Vespers, but on the octave of Epiphany, not Epiphany itself. Perhaps the second part of the Fleury play was also on the octave. At Bilsen the play followed the Benedicamus, but with this versicle nearly all the Hours end[190]. I do not, however, hesitate to [52]say that the Limoges use must have been the most primitive one. The kernel of the whole performance is a dramatized Offertorium. It was a custom for Christian kings to offer gold and frankincense and myrrh at the altar on Epiphany day[191]; and I take the play to have served as a substitute for this ceremony, where no king actually regnant was present.