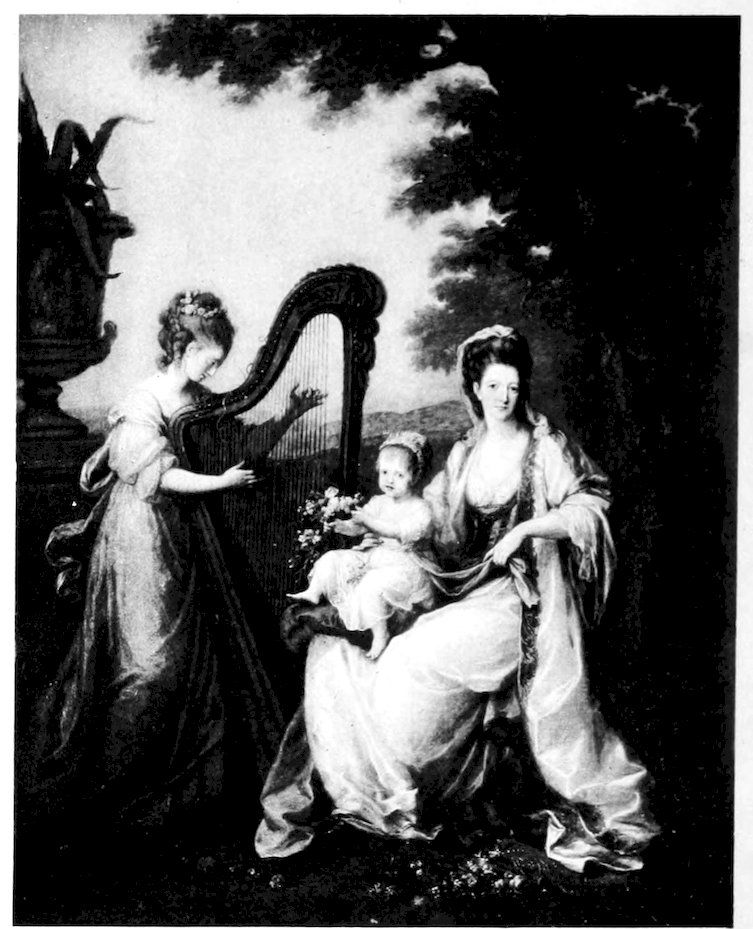

Engr. by J.J. Washington 2a

The beautiful Duchess of Argyll with her daughters Lady Augusta and Lady Charlotte Campbell

By Angelica Kauffman.

Title: Memories

Author: C. F. Gordon Cumming

Release date: November 22, 2025 [eBook #77294]

Language: English

Original publication: Edinburgh: Blackwood, 1904

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Peter Becker, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Engr. by J.J. Washington 2a

The beautiful Duchess of Argyll with her daughters Lady Augusta and Lady Charlotte Campbell

By Angelica Kauffman.

I have mentioned many pleasant things that have been mine by inheritance.

But I have suffered much from one heritage of a very trying nature, namely, the total inability to recognise general acquaintances when meeting them unexpectedly; or even real friends, whom mentally I know very well indeed, but quite fail to identify when we are suddenly brought face to face.

This grave social disability I inherit from my father, to whom the same failing was a life-long trial. Moreover, it is one for which, unfortunately, the sufferer does not always get sympathy from those whom she has failed to recognise. I mention this chiefly in the hope that it may meet the eye of some to whom I am told that I have thus occasionally most unwittingly given offence.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| INTRODUCTORY | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| ALTYRE—DUNPHAIL—NUMEROUS KINSFOLK—CORNISH RELATIONS—GRANTS OF GRANT—EPISCOPAL CHURCH | 3 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE ALTYRE GARDENS—HOME INTERESTS—OUR MOTHER’S DEATH—EARLY INFLUENCES—THE MORAY FLOODS | 34 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE ALTYRE WOODS—BANKS OF THE FINDHORN—CULBYN SANDHILLS—COVESEA CAVES | 52 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| GORDONSTOUN—A GLORIOUS PLAYGROUND—THE GREAT PICTURE—THE DUNGEONS—THE CHARTER-ROOM—OLD LETTERS—ECCLESIASTICAL CENSURES—SUCCESSIVE LAIRDS—WINDOW-TAX | 72 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| MY ELDEST SISTER’S MARRIAGE—LIFE AT CRESSWELL—SCHOOLDAYS IN LONDON—FIRST SEA VOYAGES—ROUALEYN’S RETURN FROM SOUTH AFRICA | 102 |

| viiiCHAPTER VI. | |

| MY FIRST LONDON SEASON—MY FATHER’S ACCIDENT—BEGINNING OF THE CRIMEAN WAR—DEATH OF CAPTAIN CRESSWELL—DEATH OF MY FATHER—WE LEAVE ALTYRE | 122 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| LIFE IN NORTHUMBERLAND—MY SISTER ELEANORA’S WEDDING—ALNWICK CASTLE IN 1855 AND 1892—SERIOUS ILLNESS—DEATH OF OSWIN AND SEYMOUR CRESSWELL | 140 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| AT HOME ON SPEYSIDE—THE LAST CALL TO ARMS OF CLAN GRANT—A DOUBLE FUNERAL—MACDOWAL GRANT OF ARNDILLY—ABERLOUR ORPHANAGE | 159 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE “HOME-GOING” OF THREE BROTHERS | 173 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| MARRIAGES OF MY SISTER EMILIA AND MY BROTHER WILLIAM—WE LEAVE SPEYSIDE AND SETTLE IN PERTHSHIRE—MY VISITS TO SKYE AND INDIA | 191 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| RETURN TO ENGLAND—VISIT CORNWALL EN ROUTE TO CEYLON FOR TWO HAPPY YEARS | 205 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| START FOR FIJI—LIFE IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND—DEATH OF THE REV. F. AND MRS. LANGHAM | 216 |

| ix | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| CRUISE ON A FRENCH MAN-OF-WAR—TONGAN ISLES—SAMOA—TAHITI—CALIFORNIA—JAPAN | 227 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

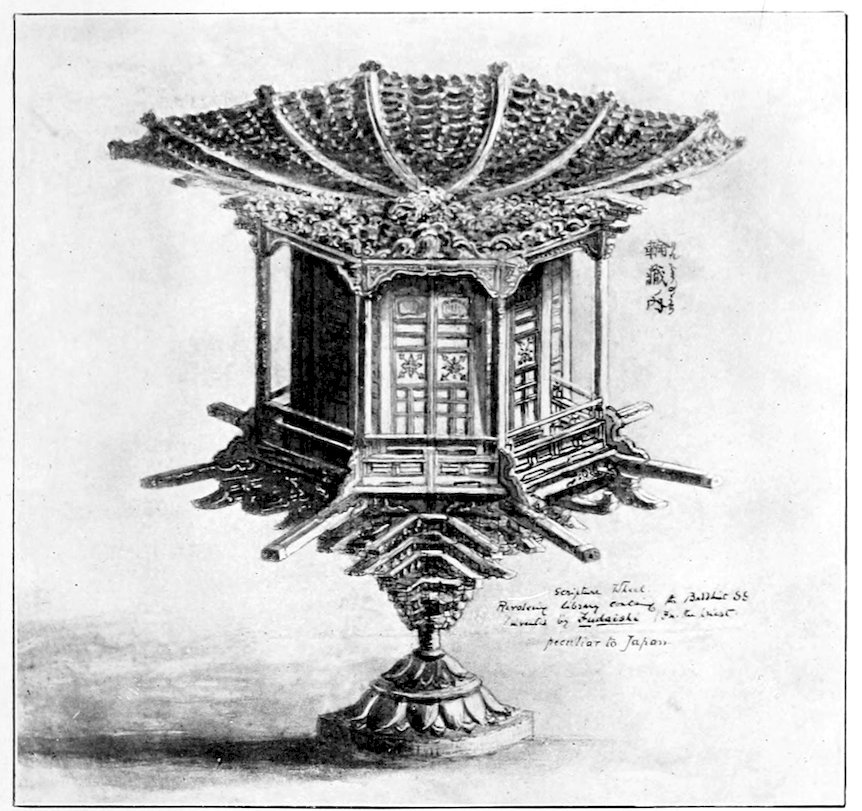

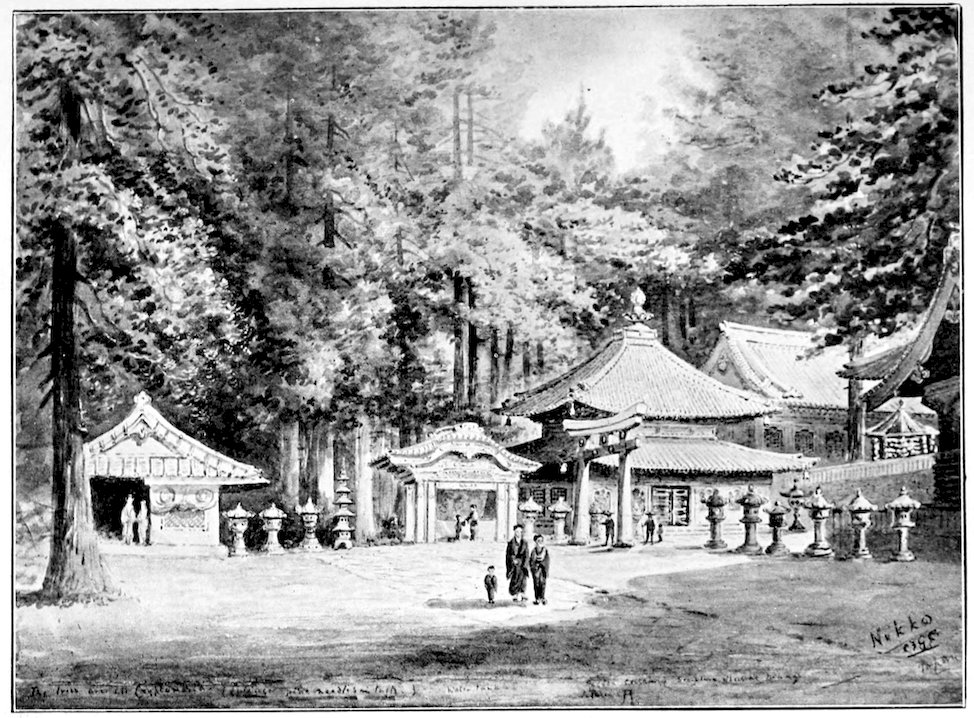

| JAPANESE BURIAL-GROUNDS—CREMATION IN MANY LANDS—SACRED SCRIPTURE WHEELS—BUDDHIST ROSARIES | 245 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| MYTHOLOGICAL PLAYS—JAPANESE THEATRES—THE FORTY-SEVEN RÔNINS—FLOWER FESTIVALS | 270 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| WAYSIDE SHRINES—THE FOX-GOD—OLD DRUGGISTS’ SHOPS—PUNISHING REFRACTORY IDOLS | 288 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

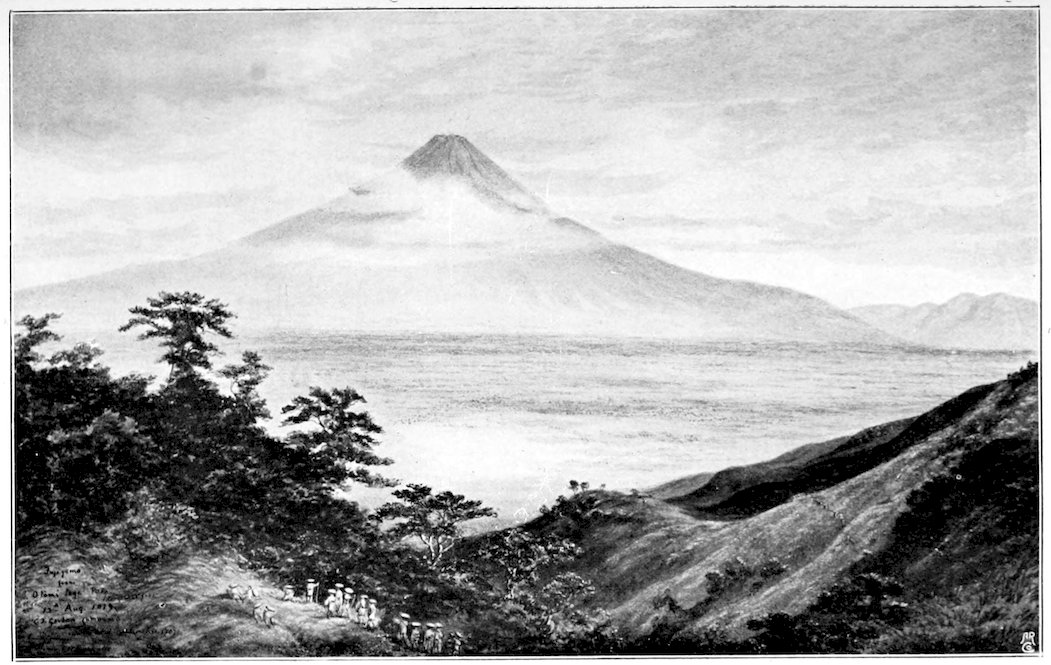

| ASCENT OF FUJIYAMA—ITS CRATER—VIEW FROM THE SUMMIT—TRIANGULAR SHADOW—NUMEROUS VOLCANIC ERUPTIONS | 307 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| THE PEOPLE ENTERTAIN THE MIKADO AND GENERAL ULYSSES GRANT—RETURN TO SAN FRANCISCO | 334 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| IN THE HAWAIIAN ISLES—SPIRITUALISM IN BOSTON—RETURN TO BRITAIN—INVENTION OF THE SYSTEM OF EASY READING FOR BLIND AND SIGHTED CHINESE | 347 |

| x | |

| APPENDIX. | |

| NOTE | |

| A. THE WOLF OF BADENOCH | 379 |

| B. THE LOWLANDS OF MORAY | 381 |

| C. A LEGEND OF VANISHED WATERS | 403 |

| D. ELGIN CATHEDRAL AND THE CHURCH OF ST GILES | 427 |

| E. ANNE SEYMOUR CONWAY | 442 |

| F. CONDITIONAL IMMORTALITY | 443 |

| G. INTERCESSORY PRAYER | 454 |

| H. CHANGE IN SOCIAL DRINKING CUSTOMS | 460 |

| I. USE OF THE ROSARY | 464 |

| J. HAIR OFFERINGS | 467 |

| K. ON THE MEDICINAL USE OF ANIMALS IN CHINA AND BRITAIN | 468 |

| L. MAGAZINE ARTICLES | 477 |

| INDEX | 481 |

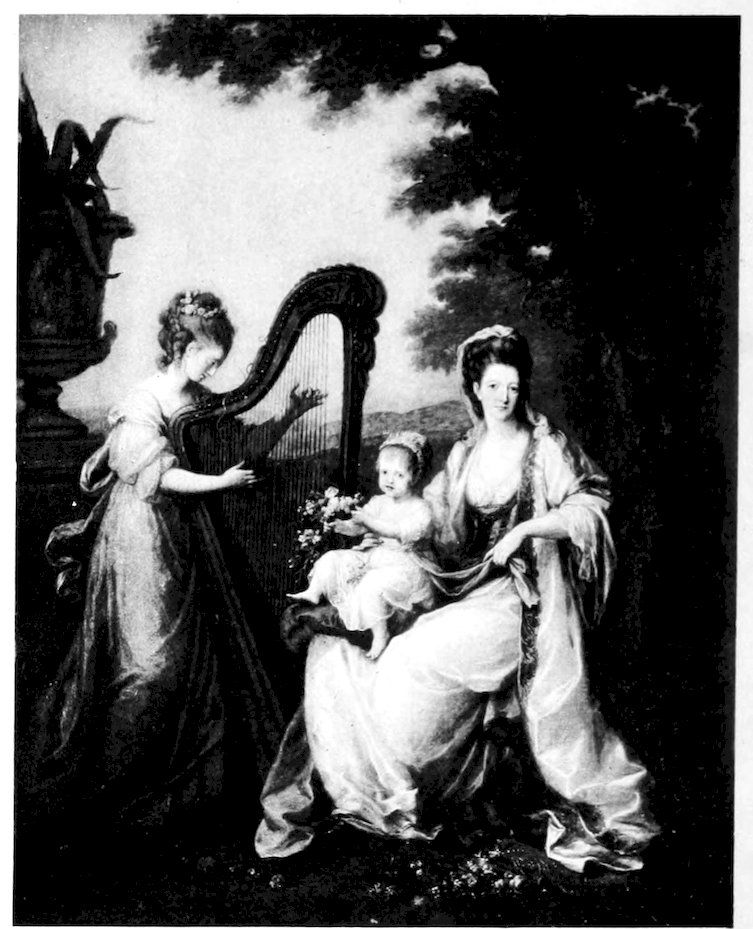

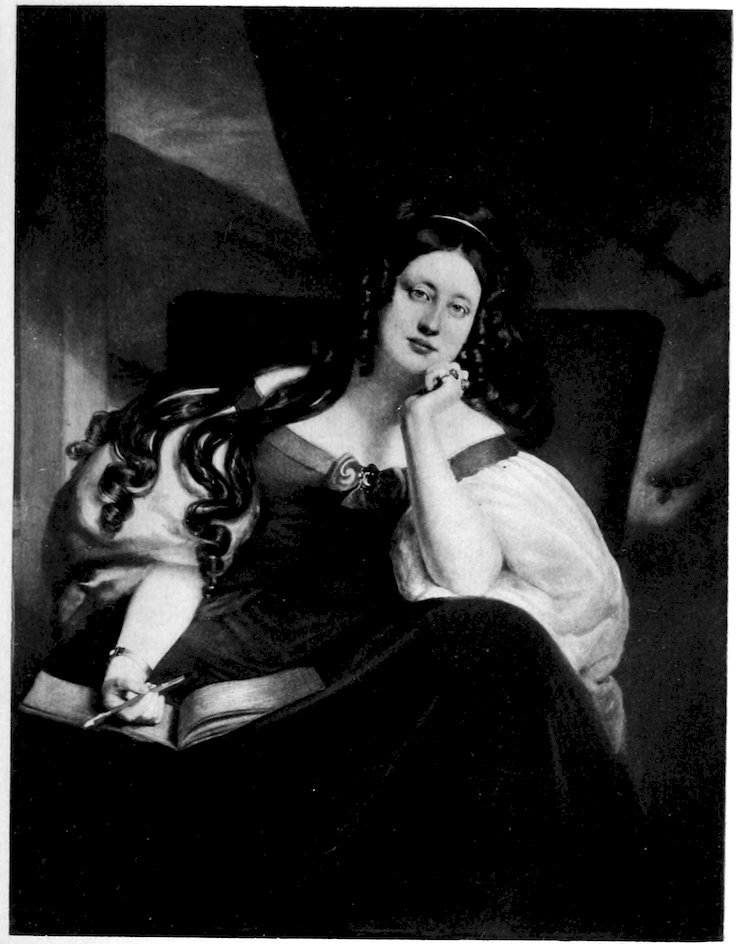

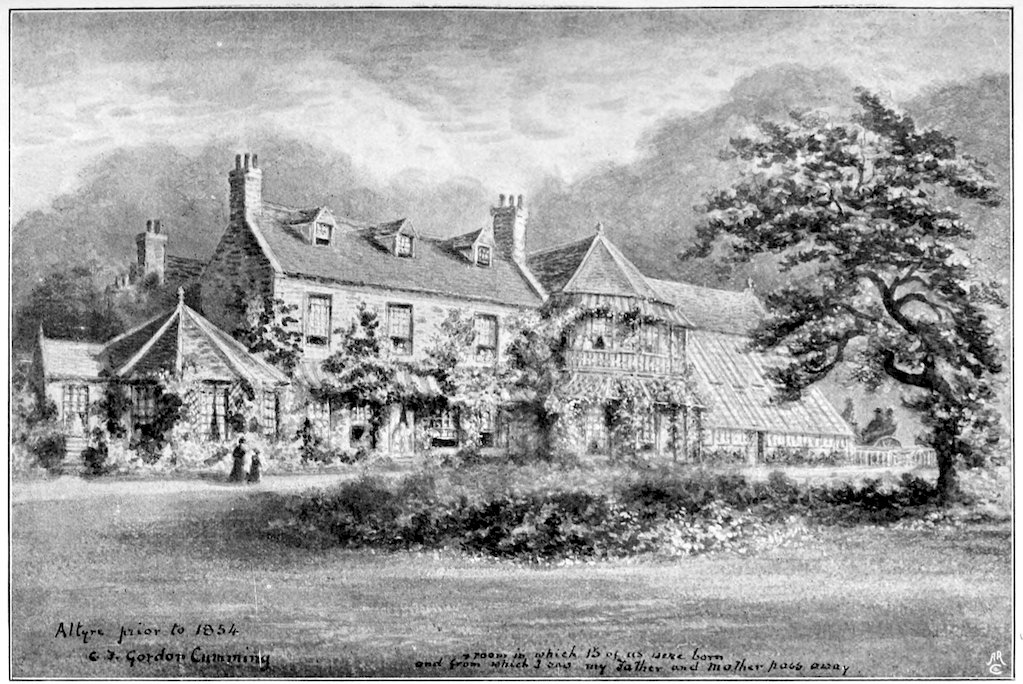

| PHOTOGRAVURES. | ||

| PAGE | ||

| THE BEAUTIFUL DUCHESS OF ARGYLL, WITH HER DAUGHTERS LADY AUGUSTA AND LADY CHARLOTTE CAMPBELL | Frontispiece | |

| By Angelica Kauffman. | ||

| LADY CHARLOTTE CAMPBELL | 16 | |

| ELIZA MARIA, LADY GORDON-CUMMING OF ALTYRE | 38 | |

| By Saunders about 1830. | ||

| ANDROMACHE BEWAILING THE DEATH OF HECTOR (THE BEAUTIFUL DUCHESS OF HAMILTON AS HELEN OF TROY) | 76 | |

| By Gavin Hamilton. | ||

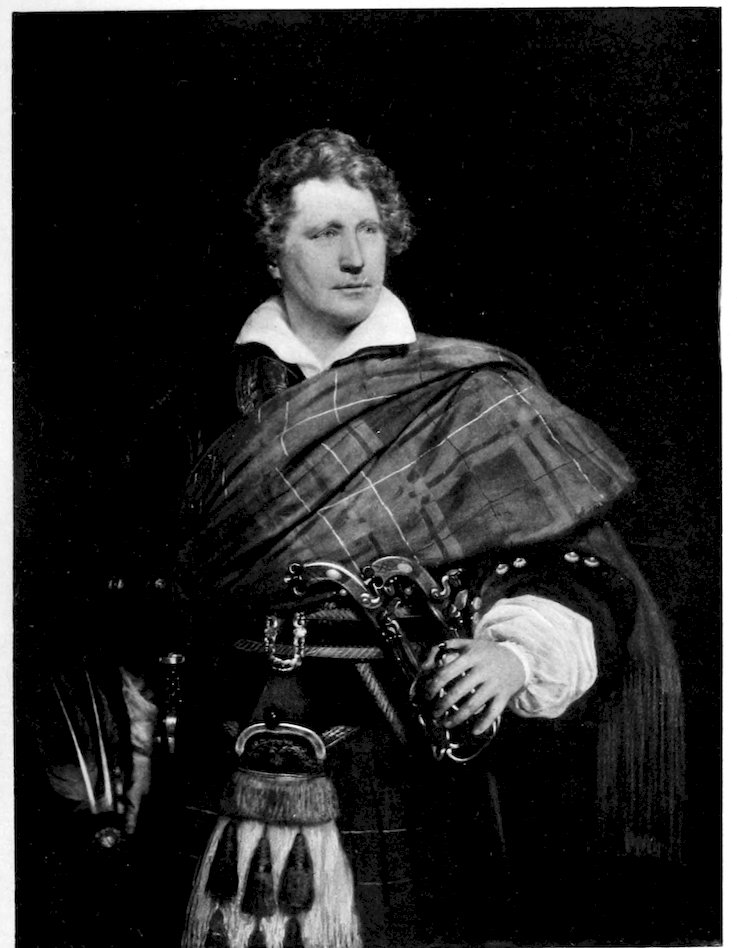

| SIR WILLIAM GORDON GORDON-CUMMING | 136 | |

| By Saunders about 1830. | ||

| ELIZABETH GUNNING, DUCHESS OF HAMILTON, AS HELEN OF TROY | 158 | |

| By Gavin Hamilton. | ||

| ROUALEYN GEORGE GORDON CUMMING IN 1851 | 176 | |

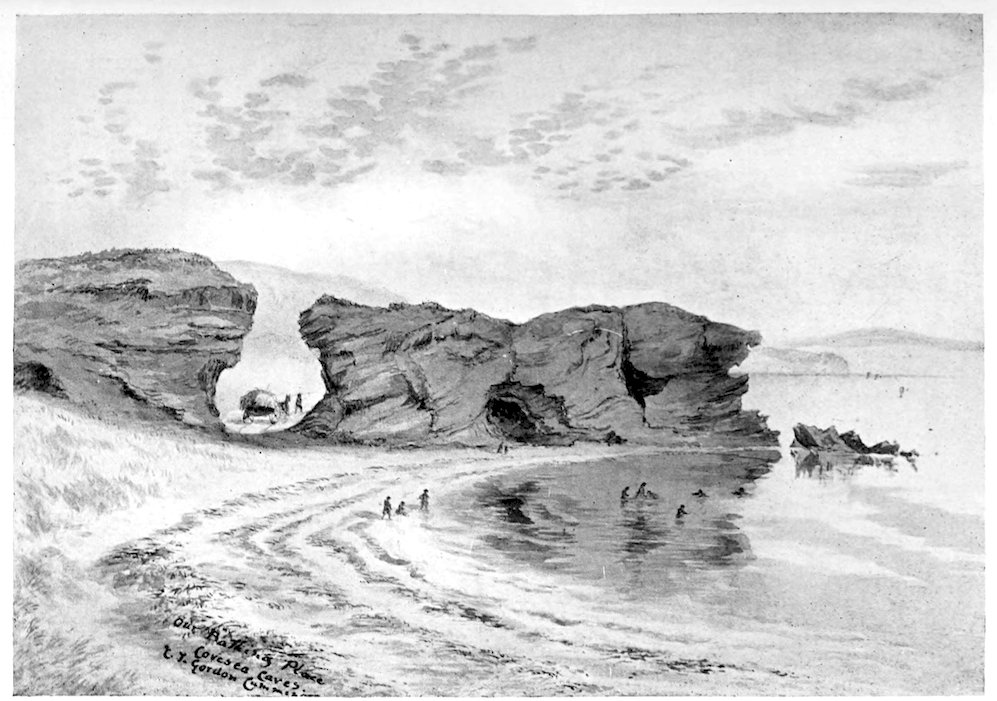

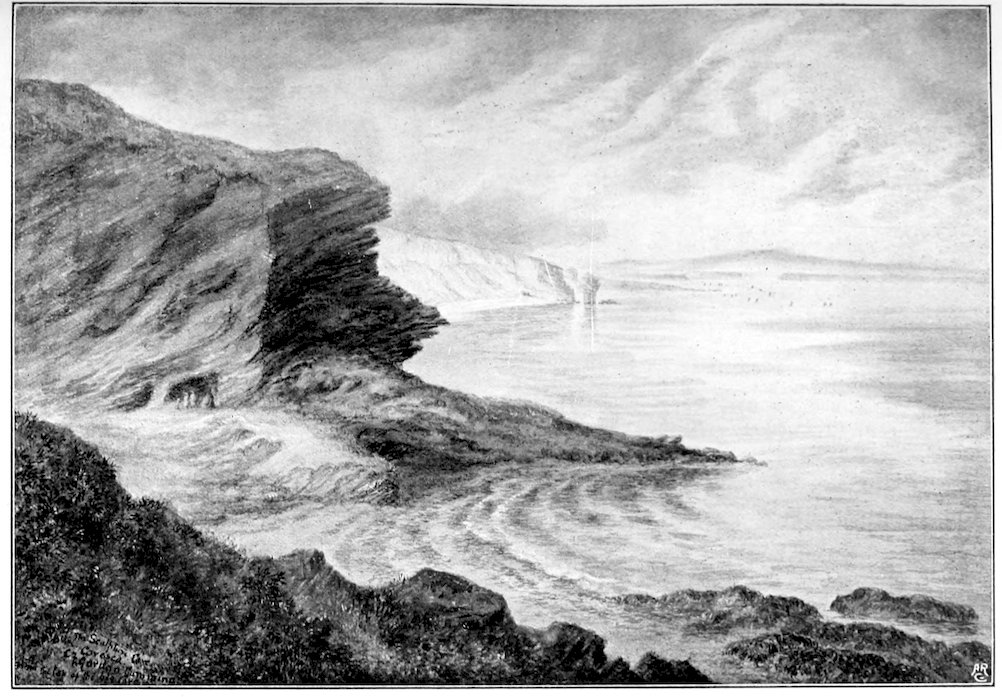

| ALTYRE PRIOR TO 1854 | 52 | |

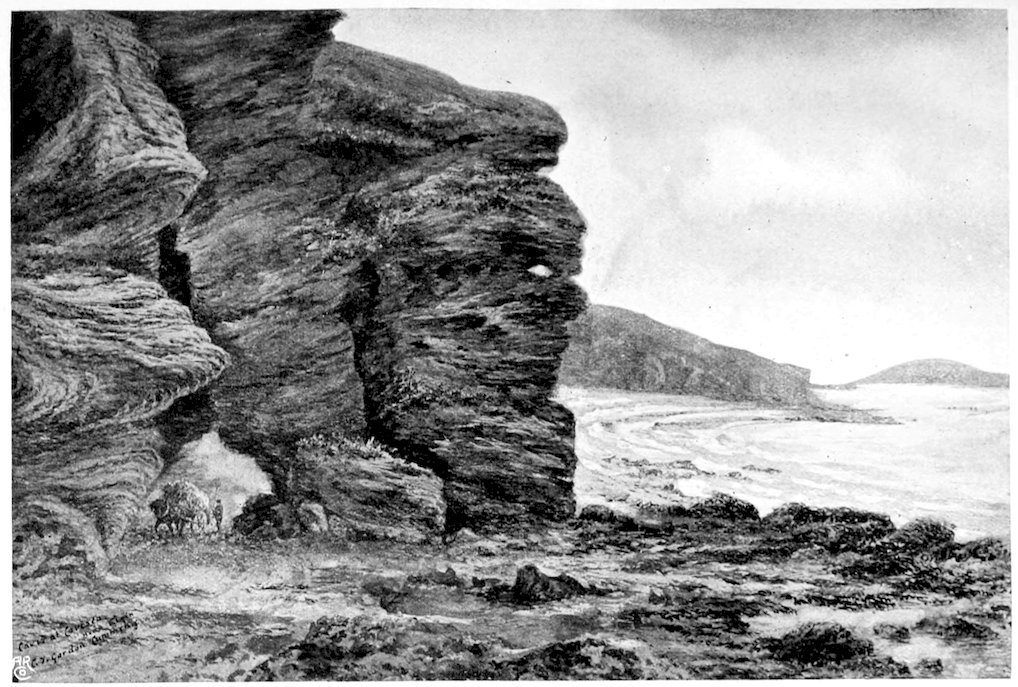

| THE BATHING-PLACE, COVESEA | 58 | |

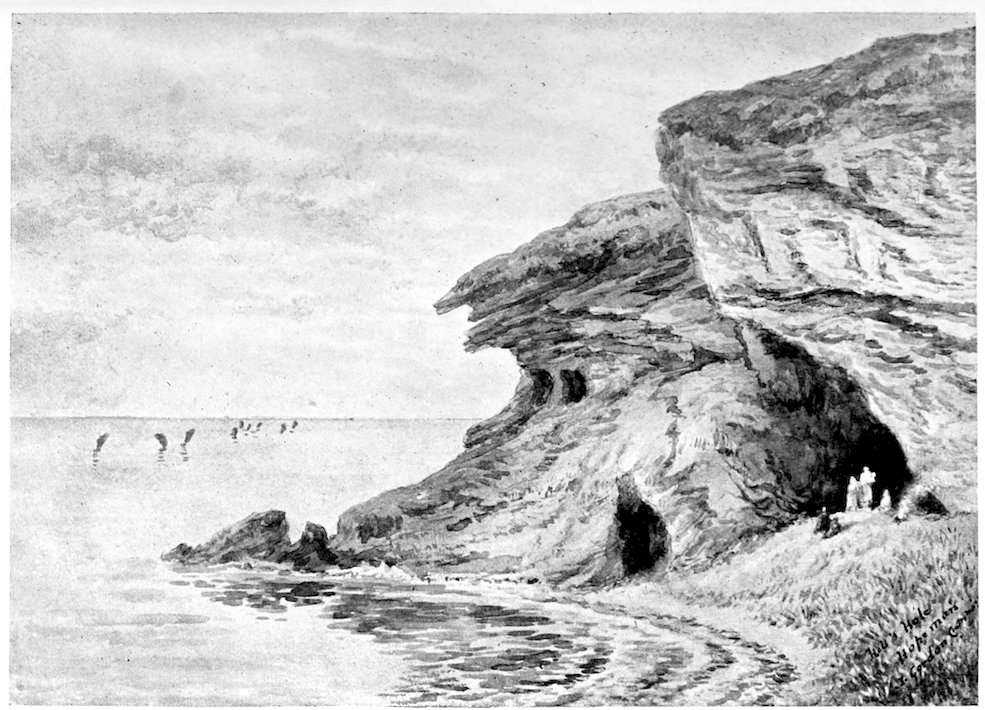

| HELL’S HOLE, HOPEMAN | 62 | |

| THE SCULPTURE CAVE, COVESEA | 68 | |

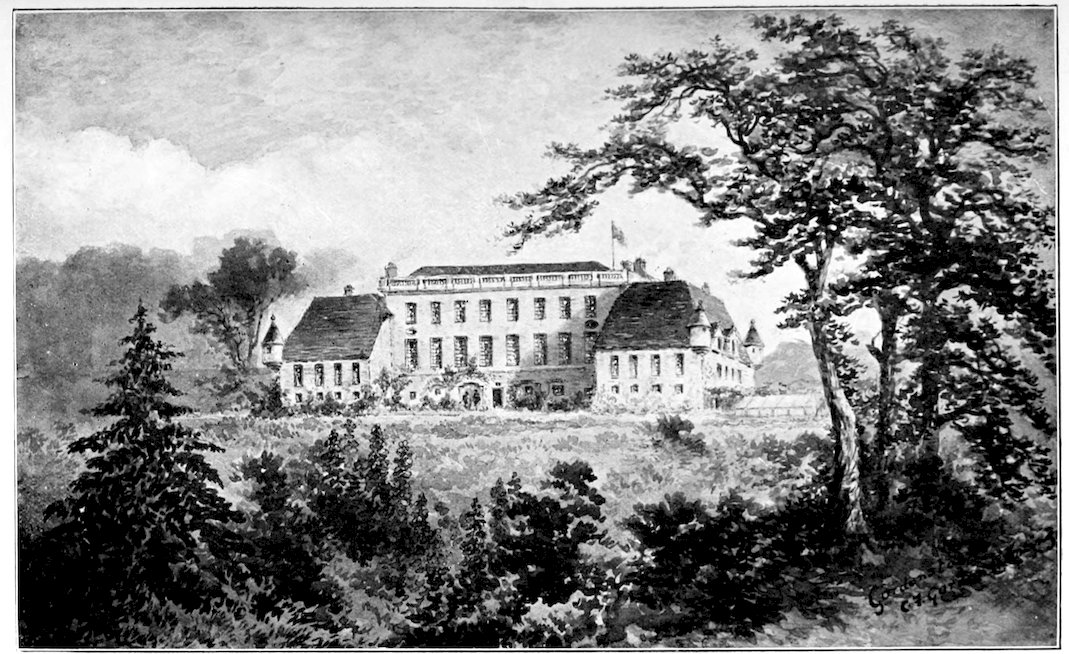

| GORDONSTOUN PRIOR TO 1900 | 72 | |

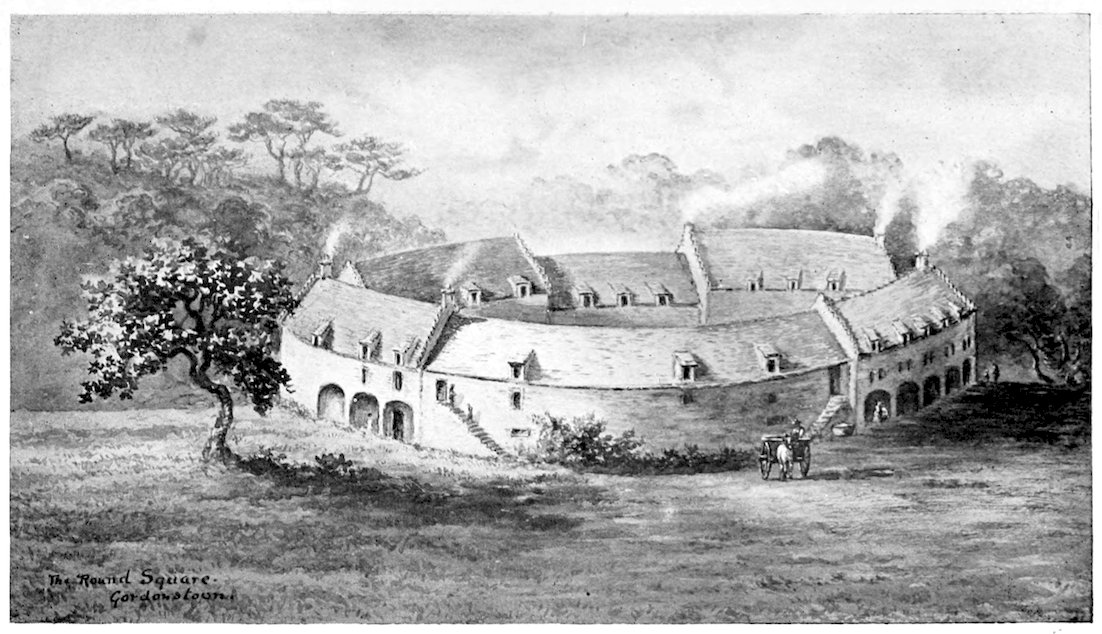

| THE ROUND SQUARE, GORDONSTOUN | 74 | |

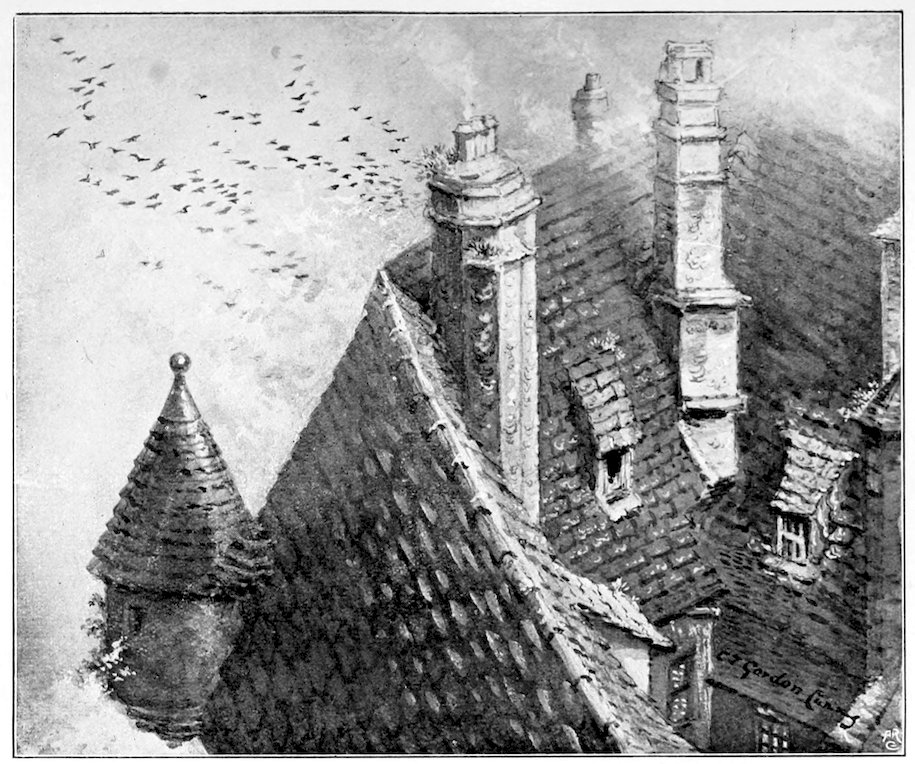

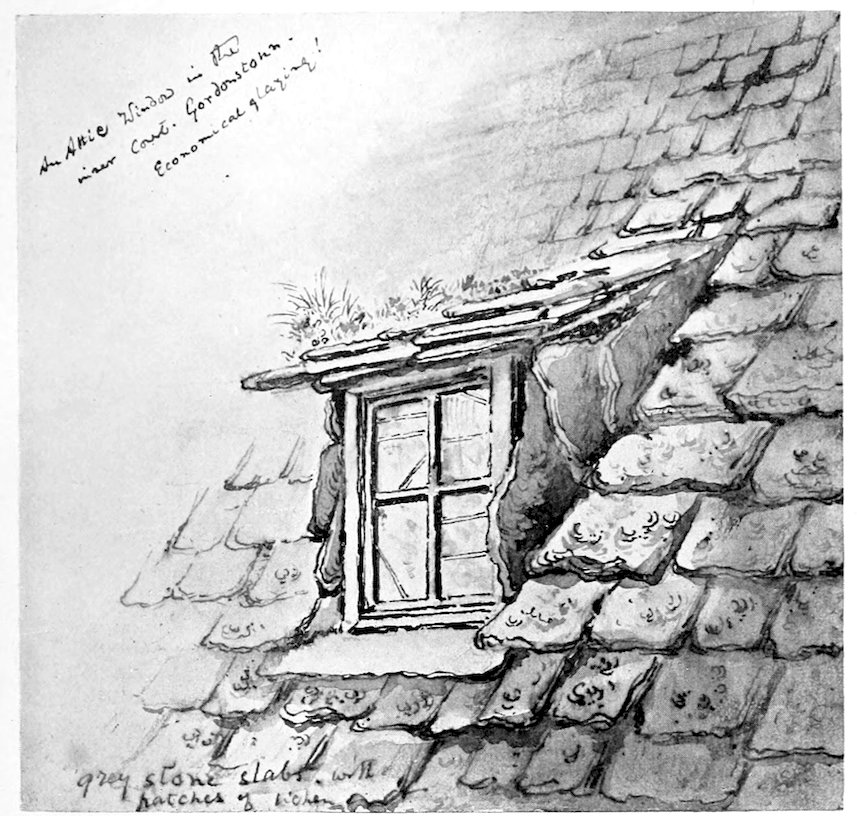

| xiiA CORNER OF THE OLD ROOF, GORDONSTOUN | 86 | |

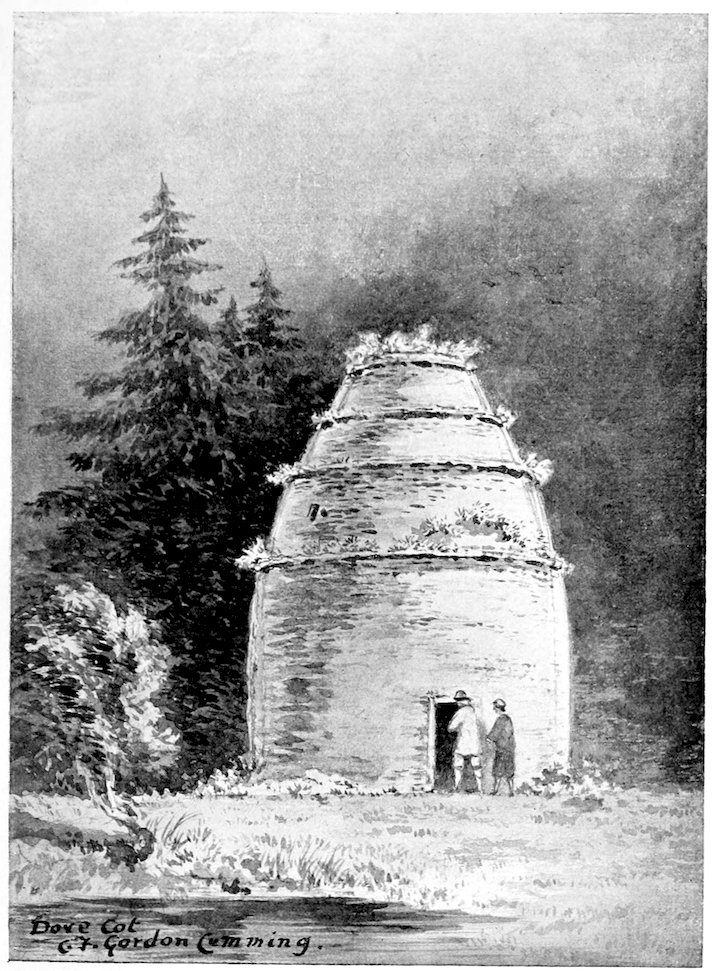

| OLD DOVE-COT AT GORDONSTOUN | 96 | |

| AN ATTIC WINDOW IN THE INNER COURT | 100 | |

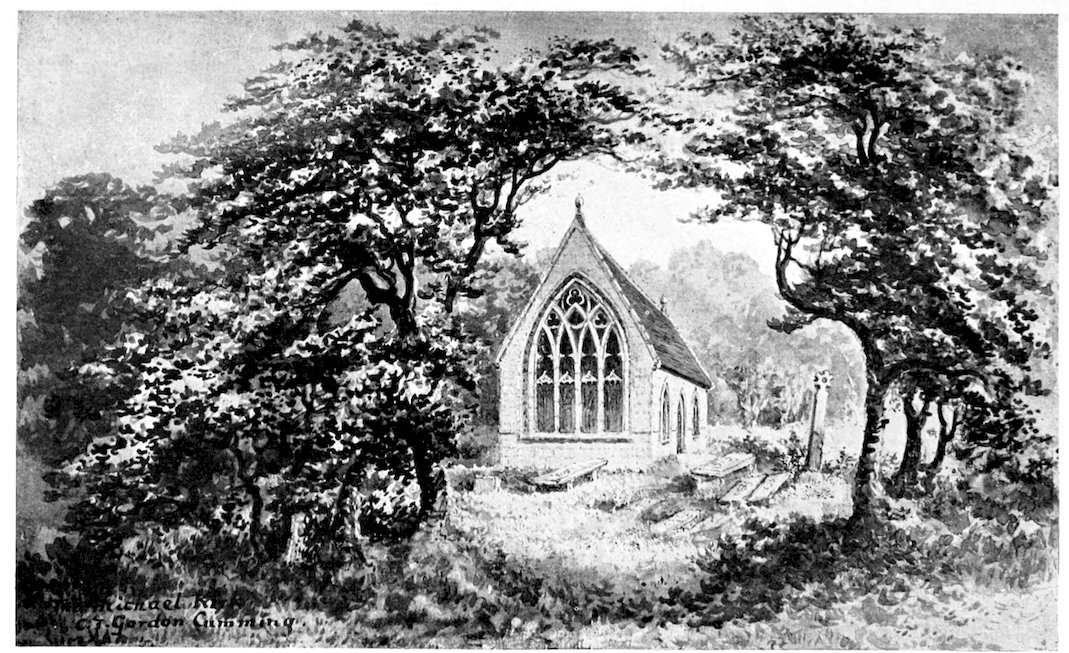

| THE OLD MICHAEL KIRK, 1866 | 188 | |

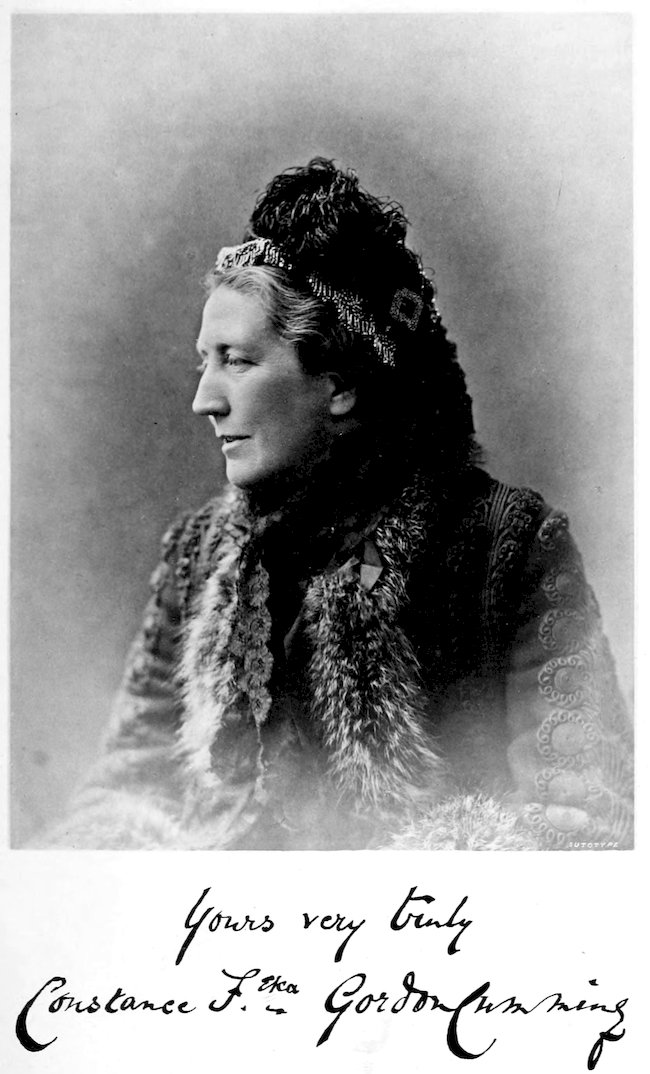

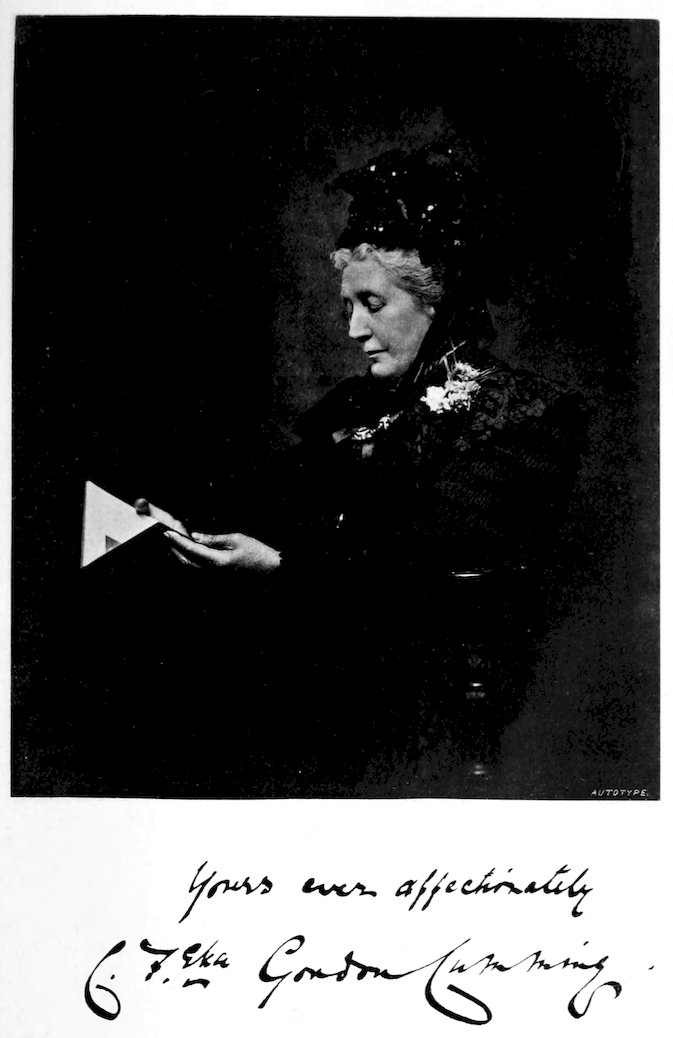

| MISS C. F. GORDON CUMMING IN 1887 | 196 | |

| SCRIPTURE WHEEL | 254 | |

| SHRINE CONTAINING THE SCRIPTURE WHEEL AT NIKKO | 258 | |

| FUJIYAMA FROM THE OTOMITONGA PASS | 308 | |

| MISS C. F. GORDON CUMMING IN 1904 | 372 | |

| A CAVE AT COVESEA | 402 | |

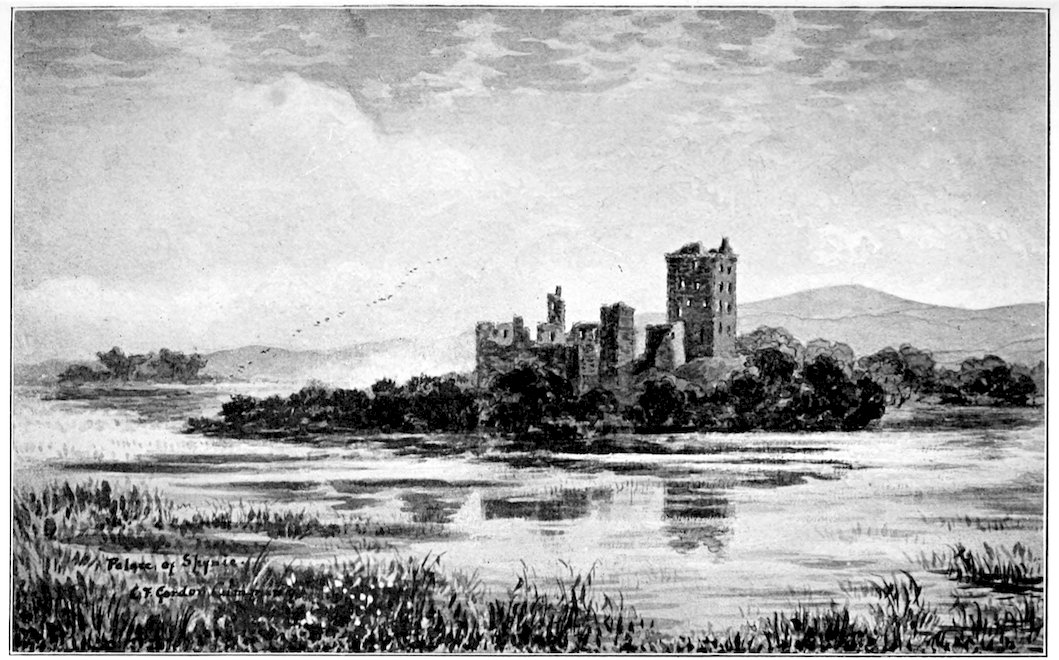

| THE PALACE AT SPYNIE, 1860 | 412 | |

In the rush and hurry of this twentieth century, the present generation find themselves so fully occupied with their own contemporaries, that for the most part they can take little or no interest, even in their own immediate predecessors, still less in their progenitors of old generations.

But we, who were born before life’s unsatisfying rush became so great, still like to gather up the traditions of bygone years, and in fancy see our own “forbears” as we know them to have been long ago.

As a daughter of the Chief of Clan Cumming, my home was, of course, at Altyre, in Morayshire, i.e. at headquarters—a goodly heritage in truth, and yet a mere fragment of the vast possessions of the Clan in the days of its power. With regard to antiquity, it is said that the Cummings of Altyre are directly descended from the Counts de Comyn who were directly descended from Charlemagne. Robert, who was fifth in descent, was created Earl of Northumberland by his cousin, William the Conqueror. He was killed in Durham in January 1069. Besides broad lands in Northumberland, his family held estates in Yorkshire and Wiltshire. From him the old knights of Altyre (who were also Lords of Badenoch) prove direct descent in the male line.

In the reign of Alexander III. the Comyns were also Earls of Buchan, Earls of Menteith, Lords of Galloway, and Lords of Lochaber, owning vast tracts of country. 2And besides these great barons, there were then thirty landed knights in the Clan.

Of the Red Comyn who (while alone at prayer in Greyfriars Church in Dumfries) was stabbed in sudden passion by Robert Bruce and murdered by Kirkpatrick, it is recorded that sixty belted knights, with all their vassals, were bound to follow his banner. But in that sacred and unguarded hour, only his uncle, Robert Comyn of Altyre, was near, and shared his fate.

The spelling of surnames in ancient documents is always liable to variation, but probably no other has lent itself so largely to the fancy of scribes. In one old charter of the Altyre family it is spelt in five different ways. Cumeine, Chuimein, Commines, Cumyn, Comyn, Comin, Coming, Cumin, Cummine, Cuming, and the modern form of Cumming, are among these varieties.

The Clan is spoken of by various old writers as the most potent that ever existed in Scotland; and a quaint old atlas, published in Amsterdam in 1654 by Jean Blaeu, quotes a somewhat older Latin work by Sir Robert Gordon of Stralloch, concerning

“Altyr, qui appartenoit à ceux de la maison de Cumines qui estoit, il y a plus de trois cens ans, la plus riche, et la plus puissante de l’Ecosse.”

How it came to pass that this powerful family should, so quickly after the accession of Robert Bruce, have been reduced to the comparatively small proportions of later years, is one of the unsolved mysteries of Scottish history.

Altyre—Dunphail—Numerous Kinsfolk—Cornish Relations—Grants of Grant—Episcopal Church.

Many a time I have been asked by friends who have found pleasure in reading my notes of travel in divers countries to write a record of my early home-life and of various matters of local interest.

Having rarely kept a journal, except when travelling, I felt that I had insufficient materials from which to compile such a record; but after a while I bethought me of one friend (Miss Murray of Polmaise), with whom for more than forty years I had corresponded regularly, and as I had preserved most of her letters, it was possible that she might have done the same by mine. So to her I applied. The answer was, “Why did you not write a month sooner? I have been setting my house in order, to minimise trouble for my survivors, and have just burnt all my old letters, including yours.” A few weeks later she entered the Larger Life, and for a while the thought passed from me.

But now that I am rapidly nearing the appointed term of threescore years and ten, and have far outlived thirteen of my fifteen brothers and sisters—i.e. all save one of my brothers, and one half-sister—it seems well to thread together such scattered details as may prove of interest to some of my numerous friends, known and unknown, many of whom I can never hope to meet face to face, but who have gladdened me by kind letters, telling me how the records of my wanderings have beguiled weary hours of suffering 4and weakness (one of these, which gave me special pleasure, was from the author of the celebrated Book of Nonsense).

So for such sympathetic friends, I will now note some early memories of those happy days—

And if such notes are apt to appear egotistic, may I be forgiven, for assuredly the records of the first fifty years of my life are those of some one quite different from my present self in every respect, both of personality and of surroundings. Indeed, I received a hint of this about twenty-five years ago, when on my return from wandering in far countries, I was told that an old family servant was anxious to see me again after an interval of about fifteen years. I went to her house, and was received with the cold glare of non-recognition. I said, “Don’t you remember Miss Eka?” “Miss Eka,” she said beamingly, “Oh, fine do I mind her, but,” doubtingly, “surely you are no her? Eh!! and ye WERE so good-looking!” I like to treasure that tribute to a forgotten past.

Though I cannot say that I remember the 26th of May 1837, I do vividly remember my father’s assuring me that early on that morning he had found me in the heart of a fine large cabbage; so I greatly respected the tall cabbages, from beneath which I retrieved deliciously sweet, small pears, which fell from a large overhanging tree—one of the countless joys of the most delightfully varied series of gardens that ever gladdened the heart of happy children, and their elders of all ages.

In looking back and considering lives and characters, I often think how little weight we give to the inestimable advantages which have enfolded some of us from our birth to our grave. Ay, and long, long before our birth, in the unspeakable blessing of healthy, well-conditioned ancestors, who have transmitted to their descendants well-balanced minds in healthy bodies, naturally cheerful dispositions, and many another pleasant inheritance; all natural gifts 5which we accept as our birthright, quite as a matter of course, yet the lack of which are to so many life-long drawbacks for which all the world’s wealth cannot compensate.

And when to these personal gifts there is added the charm of being born and brought up in singularly lovely and delightful homes, nurtured in simple, practical faith and reverence for all holy things, and enfolded in the love of a large and attached home-circle, and the wider friendship of very numerous kinsfolk, equally happy in their surroundings, such an one is truly of the number of those “to whom much is given.”

Such has been my own experience of life, always surrounded by good influences.

My mother was the very embodiment of health and beauty, bodily and mental. In physical stature, tall and stately, but above all, great in soul and intellect. My father, Sir William Gordon-Cumming, Chief of Clan Comyn or Cumming, was as splendid a Highlander as ever trod the heather, only excelled in beauty and stature by his own second son, Roualeyn, who was certainly the grandest and most beautiful human being I have ever beheld.

My mother, Eliza Maria Campbell of Islay and Shawfield, had eight brothers and sisters, twenty-one nephews and nieces, and ever so many grand-nephews and nieces. My father had fifteen brothers and sisters (of whom seven died young), twenty-nine nephews and nieces, and thirty-four grand-nephews and nieces.

So I started in life with fifty first cousins, about twice as many second and third cousins, and collaterals without number, for the family tree had roots and branches ramifying in every direction; and as each group centred around some more or less notable home, it followed that England and Scotland were dotted over with points of family interest, in those good old days when it was held that “blood was thicker than water,” and kinship, however much diluted, was fully recognised.

Looking back to those numerous centres of cheery and 6hospitable welcome, I realise that they now exist only in memory. At best the old friends are replaced by a second or third generation, but too often the old homes have changed hands; iniquitous death-duties have done their malignant work in ruining the old landowners and dispersing the many retainers who for generations had worked on the estates, in healthy, peaceful country homes.

On the death of my grandfather, Sir Alexander Penrose Gordon Comyn, my father, then a minor, succeeded to the great estates of Altyre and Dallas, Gordonstoun, and Rose-isle, all in the county of Moray.

Although the Comyns have held Altyre for certainly seven hundred—probably a thousand years—(it was Sir Robert Comyn of Altyre who, on 10th February 1305, came to the rescue of his nephew Sir John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, commonly called the Red Comyn, when he was stabbed by Bruce in the Greyfriars Church at Dumfries, and who was himself slain by Kirkpatrick)—they seem to have lived about seven miles from Altyre at the castle of Dallas (which for a while was called Torchastle), on a bleak, uninviting moorland. The very ruins of this have now disappeared, and a luxurious modern house has been built as a shooting-lodge.

At what date the original house of Altyre was built is uncertain, but contracts of marriage were there signed about 1581 and 1602 (the latter between James Cuming and Margaret, sister to Symon, Lord Fraser of Lovat). That old house was inhabited till A.D. 1789, when my grandfather, finding it too small for his sixteen children, bought Forres House, at Forres, from the Tullochs of Tannachie. On his death it became the dower-house of his widow, who died there in 1832. For a few years after their marriage, they had lived at Cothall, close to the river Findhorn, a very pleasant situation in a green meadow enclosed by old trees. Only a fragment of ruin now marks the spot.

My father’s intention always was to build an entirely new 7house on a hill about a mile from old Altyre. At great cost, he levelled the summit of the said hill, making an excellent carriage road, winding gently round to the proposed site, from which there is a wide, beautiful view, overlooking the Altyre and Darnaway woods, with a distant view of the pretty little town of Forres and of Findhorn Bay, and across the Moray Firth to the faint blue distant hills of Ross, Sutherland, Caithness, and Cromarty. It is a delightful spot, known to this day as “the Situation,” and for many years building thereon was the dream of my father’s life.

Close to the Situation, another heathery, fir-crowned hill has from time immemorial been known as the “Gallows Hill,” whereon any one who had the misfortune to incur the wrath of the knights of Altyre was ruthlessly hanged in the “good old days,” when it is related of one awe-stricken wife that she urged her unwilling husband to go quietly to his doom and “dinna anger the laird.”

As it was not convenient to begin at once building on the new site, my father and mother decided that for a while they would continue to live in the old house; and then began the laying out of those great, beautiful gardens and shrubberies of which comparatively little now remains—sacrificed to the changing taste of successive generations. They also laid out many miles of romantic woodland paths, which made the whole place a dream of delight. And so they became more and more disinclined to leave the home they had made so fascinating; and as their family increased they occasionally added a few rooms to the old place, which thus gradually developed into a picturesque patchwork, covered with climbing roses, honeysuckle, and jessamines, and beloved by the happy children, to whom it was indeed an earthly paradise, the profusion of flowering shrubs so lavishly planted in every direction adding their fragrance to that of the sweet woods.

Moreover, in those halcyon days, we were allowed to breathe the pure air as God created it for us, unpolluted by 8the fumes of tobacco, which assuredly can have no place in any paradise—certainly not in the Celestial! Only as years went on did my brothers yield to the new temptation, and venture to smoke a pipe in the kitchen when all the household were safe in bed. As to smoking-rooms, they were not invented in any houses within our ken.

Among the many incongruities in that dear old home, not the least was the importation from abroad of three large fixed baths, which, with an abundant supply of hot and cold water ready to hand, were a luxury by no means common eighty years ago.

But far more attractive to the younger generation was a wooden enclosure, built across a pool in a delightful rivulet on the further side of the lawn, which, by means of a sluice, could be deepened at pleasure; and there we could bathe to our hearts’ content in the clearest and softest brown water, with trees and sky overhead, only one corner being roofed as protection in case of rain.

All the water-supply for washing purposes came from one of these brown rivers, and sometimes after heavy rain its colour was so dark as greatly to surprise guests from the south, unused to peat regions; but all confessed that no crystal streams could yield water so delightfully soft.

Though the entailed lands necessarily passed to my father, Sir Alexander’s love centred on his second son, Charles Lennox, to whom he left the lovely estate of Dunphail, on the romantic banks of the river Devie, just above its junction with the Findhorn, which is by far the loveliest river in Scotland, and which divides the fascinating woods of Altyre from those of Darnaway Castle, one of the Earl of Moray’s many estates. Dunphail, which had formerly belonged to the Cummings, had fallen into other hands. Sir Alexander bought it back for his favourite son.

Of all legends of the north, none is more gruesome than that which tells how, about the year 1340, Randolph Stuart (who had been created Earl of Moray by his uncle, King 9Robert Bruce) besieged Alexander de Comyn, the old knight of Dunphail, and five of his six sons in their strong castle. For long they held out, till at length Randolph discovered that night after night the eldest son, Alastair Bhan (i.e. the fair), contrived to bring them food.

Soon he tracked him to his hiding-place, Slaginnan, a well-concealed cave in a thickly wooded ravine beside the river Devie. His followers closed the entrance to the cave with piles of heather and brushwood, and to his prayer to be allowed to come out and die “like a man,” fighting for life, they replied, “No, you shall die like a fox,” and so they fired the brushwood and smoked him to death. Then they cut off his head with its masses of golden hair, and threw it over the castle wall to the unhappy father, crying “There is beef to your bannocks.”

Starvation soon compelled surrender, and the besiegers ruthlessly beheaded all their prisoners, carrying off the heads as trophies, but burying the seven headless bodies in one grave at the foot of the castle rock; a grave always known as that of the Seven Headless Comyns. It was opened in the last century, I believe, by order of Major Cumming-Bruce, and the truth of the story was fully confirmed.

This Randolph Stuart was very nearly akin to that other miscreant, Alexander Stuart, known as the “Wolf of Badenoch,” son of King Robert II., who bestowed on him the lordship and lands of Buchan and of Badenoch, wrested from the Comyns, and who was distinguished only for his savage brutality. In the year 1390 he swooped down from his castle of Lochindorb and burnt first the town and church of Torres, and a month later did likewise by the stately cathedral of Elgin, the parish church of St. Giles, and other ecclesiastical buildings, as well as a great part of that city.

I feel bound to mention this detail, because I have so often heard it asserted that the cruel “Wolf” was a Comyn, 10whereas our forbears were then in the position of the unjustly maligned lamb.[1]

Many and glad were the happy weeks we so often spent among the lovely ferny and birch-clad glades and glens on every side of beautiful Dunphail, which to us was just as much home as Altyre itself. These homes were connected not only by a first-rate carriage road, but by miles of skilfully led footpaths along the beautiful, craggy banks of the Findhorn, the Devie, and the Dorbach, through the estates of Altyre, Logie, and Relugas, all the estates of Cumming cousins,[2] who were of one heart and one mind in all that tended to open up their lovely estates, and make their beauty accessible to themselves and others.

But as both my father and his brother had a curious talent for instinctively hitting on the very best line for constructing roads and footpaths through dense and well-nigh untrodden brushwood, the task was altogether left to them, resulting in the excellent paths, most of which remain to this day as their abiding memorial. Others (extending for miles up the Altyre burn—“by the sweet burnside”—and through one specially lovely glade known as “the Sanctuary,” where stately silver pines cast their cool, deep shade over a carpet of greenest moss) were demolished when the ruthless railway was led down that glen, and many more have now been closed, but enough remain to earn the gratitude of successive generations.

Perhaps the loveliest, and certainly the most unique stretch of river-hewn rock, is the half mile of the Findhorn on the estate of Relugas, just above its junction with the Devie, where at one point the whole volume of brown waters rushes through a cleft so deep and narrow, that on one occasion when Randolph, Earl of Moray, was closely pursued by foes, he actually leaped from crag to crag and so escaped. 11This spot, known as “Randolph’s Leap,” is naturally the chief attraction to visitors who drive from afar to carry to more prosaic homes a memory of the dreams of beauty, which by the generosity of all the lairds in the glen have for the last three generations been made so easy of access.

Very sad to say, the continuity of these beautiful paths has recently been destroyed through the selfish policy of the late non-resident proprietrix of this most fascinating estate. In order to make her own walks more attractive to summer tenants, by ensuring their own privacy while taking unrestricted enjoyment of all walks and drives on the neighbouring estates, she for some years past only allowed the public access to this specially attractive half mile on one day of the week, while quite excluding them from other lovely river-paths. So that the most interesting point on the beautiful Findhorn is now the one blot; which sends many away bitterly disappointed, because their only opportunity (perhaps in a lifetime) of visiting the district (or of revisiting the haunts of their youth) was not on the day so arbitrarily fixed. Remonstrances and representations on this subject have hitherto proved all in vain.

At the time when I can first remember lovely Relugas, it was the scene of a curious instance of a man gaining his heart’s desire. Young Mr. Mackilligan started from Elgin to carve his fortune in Ceylon, then comparatively unknown to planters. As he left Scotland, he confided to a friend that his ideal of all possible bliss would be to own Relugas (then the property of Sir Thomas Dick Lauder), and to be the husband of Eliza Marquis, a very handsome and winsome girl.

Strange to say, on his return, having made his pile, he found that Relugas was for sale, and that he was still in time to woo and win the maiden. Thus was his double ideal fulfilled. But alas! his health was shattered, and his wife proved equally delicate, so it was truly pathetic to visit them, and find each confined to a sofa, only able 12to enjoy the beauty which they could see from the windows.

After his death, his widow deemed it best for her children to sell the place, which was bought by the George Robert Smiths, who proved the kindest of neighbours. To them a special attraction was the near neighbourhood of Dunphail (only a mile by a lovely river path) the home of their dear friends, the Cumming-Bruces.

My uncle, Charles Lennox Cumming, had married Mary, the grand-daughter and heiress of Bruce the famous Abyssinian traveller, from whom she inherited the estate of Kinnaird near Falkirk, and the old house containing many valuable sketches and all manner of travel treasures from Abyssinia, the Hawaiian Islands, and other regions, to visit which, in his days, had been a matter worthy indeed of a great explorer. Of course the heiress retained her own name, hence the family of Cumming-Bruce.

Even in the beginning of the nineteenth century, the difficulties of travel were still so great that my Uncle Charles was deemed quite a hero on his return from wanderings in Turkey, Greece, and Italy. To the latter he took his bride—a honeymoon commemorated by the Italian character of the picturesque house which they built at Dunphail on their return, also of the little Episcopal Church in Forres. The very ornamental farm buildings at Altyre were a similar tribute to Italy by my father.

To students of old Scottish story, it is worthy of note that this was the very first occasion since the murder of our ancestor the Red Comyn by King Robert Bruce that the two clans had intermarried. Curiously enough, the combination was repeated in the next generation, their only child, Elma Cumming-Bruce, having married James Bruce, Earl of Elgin. She died in Jamaica, leaving one infant, Lady Elma Bruce, who inherited the estates of her grandparents. She married Lord Thurlow, but her children decided to bear their clan names. Her eldest son, “Fritz” Cumming-Bruce, 13was killed when gallantly leading his 42nd Highlanders in the deadly charge at Magersfontein, and a younger son, Sigurd, died of enteric almost at the same time.

The eldest brother now surviving is the Rev. Charles Cumming-Bruce, who is establishing much-needed Seamen’s Institutes at many points between Vancouver and Portland (Oregon), where he ministers to seamen of many nationalities and tries to protect them against sharpers of the worst type. We may be excused a little pardonable pride in him and his good work as, so far as we can trace, he is the only relation bearing our name who in recent centuries has entered holy orders. In fact two Forbes and two Dunbar cousins are apparently our only ecclesiastical representatives in any branch of the family.

But it is satisfactory to know that twelve hundred years ago Cumming the Fair held the Bishopric of the Isles, as seventh bishop of Iona; and in his memory the Highlanders still call Fort Augustus on Loch Ness “Kil Chuimein,” “the Cell of the Cumming.” Now the grey fort has in its turn been demolished, to be replaced by St. Benedict’s Abbey, and a large Benedictine monastery.

To return to the beginning of the nineteenth century. It was not only continental travel which was difficult in those days. Many a time have I heard my father describe his early experiences of being sent from Morayshire to England and back for his holidays by a slow sailing-smack, a mode of transit which, besides being wretchedly uncomfortable, cut largely into the holidays; as in foul weather the voyage to London might take three weeks or even four. When Sir Robert Gordon brought his family from London to Gordonstoun, the voyage took them forty days. It was not till 1822 that the first steamer of any importance appeared in the Moray Firth, and several years later ere sufficient trade was developed to make it worth while to establish a weekly steamer between Inverness and Leith, calling at intermediate ports.

14In common with several of our kinsfolk, my grandfather availed himself of his right to send my father to be educated at Winchester College, being “Founder’s kin” to William of Wykeham. Hence our early familiarity with the good old Wykeham motto, “Manners maketh man,” and with that curious old picture, a life-sized copy of which hung in the kitchen at Altyre, showing the “Trusty Servant,” with the swift feet of the deer, the long ears of the patient ass, the snout of a pig “not nice in diet,” and the padlocked mouth, which proved how safe in his keeping were his master’s secrets.

In their early days my father and his brother Charles travelled together in Italy, where the handsome Highland dress, which the former always wore in the evenings, attracted much admiration and curiosity. On one occasion he observed that two Italian ladies, who were sitting beside him, were deep in the discussion of some question, and that his neighbour edged nearer and nearer to him. At last a gentle finger suddenly touched his knee, and its owner rapidly retreated with an expression of disgust, exclaiming to her companion, Carne da vero![3]

The gay Cumming tartan of scarlet and bright green, crossed with narrow lines of black and white, has generally been reserved by the men of our family for evening wear, the dark green and purple, with narrow yellow stripe, of the Gordons being preferable for day wear. Of course, as chief of the Clan, my father wore the symbolic three eagle’s feathers in his broad blue bonnet.

Of our two Clan badges, the Gordon evergreen ivy leaf, with its pretty motto, Je meurs où je m’attache, has naturally been more popular than the saugh, or broad-leafed deciduous willow, known in Scottish song as “the frush” i.e. brittle saugh-wand. Our family mottoes, Sans crainte of the Gordons, and Courage of the Cummings, have undoubtedly proved inspirations.

15It was in Italy that the brothers first made the acquaintance of my beautiful grandmother, Lady Charlotte Campbell of Islay, and her lovely daughters.

Here I must record a curious detail of fortune-telling. Shortly before that memorable meeting, Lady Charlotte and some of her daughters visited an Italian lady, who expressed a wish to tell Eliza’s fortune. The girl objected, but the lady insisted. She told them that political troubles were even then brewing, and that within a few days complications would arise which would make their position in Florence very uncomfortable. But just in the hour of need two fair-haired Scotsmen would come to their rescue, and that she would marry the elder of the two.

Strange to say, all came about exactly as the lady foretold. Sir William and his brother did arrive in Italy just when political complications had arisen, and hearing that some of their countrywomen were in difficulties, they at once went to offer themselves as their escort to Switzerland. And so it came to pass that in September 1815, in the little Church at Zurick, Eliza Maria Campbell, aged seventeen, became Lady Comyn-Gordon, for so the order of the double surname was then arranged, and the old spelling was not finally given up till later.[4]

My mother’s sisters, as also her two brothers, were not long in following her example. Beaujolais (so called after the Comte de Beaujolais,[5] who was a special friend of Lady Charlotte) married the Earl of Charleville. Julia married 16Mr. Langford Brooke, of the Mere in Cheshire. (She had the anguish of seeing him drowned before her windows while skating on his own lake.) Emma married William Russell, son of that Lord William who was murdered by his own valet, Courvoisier. Constance Adelaide married Lord Arthur Lennox. (Her daughter Constance married Sir George Russell of Swallowfield.)

It was of Eleanora, the loveliest of all, that Harriet, Countess Granville (see her Memoirs) wrote: “She is decidedly the girl I should prefer Hartington’s marrying. She is beautiful, and dans le meilleur genre, with the sweetest manners I ever met with. She is really quite enchanting.”... She goes on to speak of her own little Granville as “a delightful little companion, so full of natural tact and instinctive civility, which prevents his ever being de trop.”

Curiously enough, when the little son grew up, he was equally attracted by Eleanora’s beautiful niece Castalia, daughter of Uncle Walter, and they filled the same rôle of ambassador and ambassadress as his parents had done before him.

Aunt Eleanora was my mother’s favourite sister, and it was in the pretty sitting-room at Altyre that, in 1819, she was married to the Earl of Uxbridge. Her life was very brief, and in an album of my mother’s I find the verse quoted as relating to her:—

Her son succeeded his father as Marquis of Anglesea; and of her beautiful daughters, Ellen married a son of Sir Sandford Graham, and Constance married the Earl of Winchelsea.

Emery Walker. ph. sc.

Lady Charlotte Campbell.

Of the brothers, Walter Frederick, owner of Islay and Shawfield, married his own first cousin, Lady Ellinor 17Charteris, who died, leaving only one son, John Francis, the well-beloved Ian, whose home, Niddry Lodge, near London, was for so many years the central gathering-point, not only for all the family, but for all sorts and conditions of men with whom his great mind found congenial interests in all the countries where he wandered, sketching and studying geological and other problems. His book on the action of Fire and Frost made a considerable mark, as did also his Tales of the West Highlands, four volumes of old Celtic legends collected by himself from Highlanders and Islanders, whose hearts opened wide at the sound of their own Gaelic tongue, a birthright which likewise proved a key to sympathy wherever the old Celtic races still survive.

Uncle Walter married secondly Katharine, daughter of Lady Elizabeth Cole, a sister of Lord Derby. She had one son, Walter, and four daughters, Augusta, Eila, Violet, and Castalia, who married respectively, Mr. Bromley-Davenport, Sir Kenneth Mackenzie of Gairloch, Henry West, and Earl Granville.

Alas! two bitter sorrows early overshadowed the life of this dear aunt. First when Uncle Walter discovered that the princely fortune, which had been deemed inexhaustible, had, in some totally unaccountable manner, melted away in the hands of his agents, and that when, in the terrible years of famine caused by the potato-blight, he was supplying his starving islanders on Islay with shiploads of grain imported from America, it was being paid for with borrowed money. (The islanders, of whom to-day there are only seven thousand, then numbered twenty thousand.)

It is said that any man of business would have put the whole matter into the hands of trustees, who could have put all right in two or three years. But his only instinct (in which Ian implicitly agreed) was at once to get rid of the disgrace of being in debt to any one, and so all the properties were at once thrown on the market. No sooner were they sold than minerals were discovered on the estate 18of Shawfield, which would have cleared off all deficits, and which have built up the great wealth of the Whites, as represented by Lord Overtoun.

The terrible sorrow of leaving beloved Islay was doubtless in a great measure responsible for the still greater loss which shortly followed—namely, that of sight. Doubtless there had been some constitutional weakness latent, but inability to restrain the bitter tears that would keep on flowing, even more in sympathy for her adored husband than for her own great sorrow, was apparently the immediate cause of this terrible loss, which for fifty long years threw the shadow of darkest night over one hitherto so joyous and so blest.

Ere long came the crowning sorrow, when her noble husband was taken from her; but then as a pillar of strength came the life-long devotion of her step-son, who thenceforth made it the chief concern of his life in every way to minister to her in her darkened lot, and to be at once father and brother to her children—children of whose beauty she heard on every side, but whom she was never to see.

In all my memories none are more pathetic than those of delightful summer afternoons in the pleasant shady garden at Niddry Lodge, with all her own strikingly handsome family and their husbands gathered round her, sometimes to watch a game of chess with Lord Granville, which was her special delight, and as she turned her large grey eyes on one or other of us, and made some comment concerning friends whom she had recently “seen” and how they looked, it was difficult to realise that to her all was total darkness.

Ere she once more entered into Light, one great joy was granted to her in the form of a true romance of the nineteenth century. Naturally the very name of Mr. Morrison—the purchaser of her beloved island home—was to her abhorrent. But once again, as in the days of the Capulets and Montagues, deepest love was born of her only hate. A 19third generation grew up, and Hugh Morrison wooed and won the love of Lady Mary Leveson-Gower; and when he brought sweet Mary Morrison to her ancestral home on Islay, the joy of the Islanders at this return of the beloved old race was unbounded.

Of my mother’s other brother John and his wife, I have no recollection, only that they left a son, Walter, and a bright, pretty daughter, Edith, who married Mr. Callander of Ardkinglas, near Inveraray, and died leaving two sons.

Now I must go back to the previous generation to tell of the mother of all these beautiful sons and daughters, namely my grandmother, Lady Charlotte Campbell. She lived till I was quite grown up, and even in old age she was stately and fair to see, notwithstanding the lamentably free use of red and white paint. Even in very advanced years she always sat rigidly upright, and sorely disapproved of the lounging habits of the younger generations, which she described as “sitting on their spines”—a most undignified position.

Latterly she was known to the world as Lady Charlotte Bury, having unfortunately contracted a second marriage with the Rev. Edward Bury, which was in no way conducive to her happiness. Amongst other iniquities, he stole and sold to a publisher her private journals, kept during the years when she was the faithful attendant of Queen Caroline. She never discovered the theft till they appeared in print as the Diary of a Lady of Quality. The book was promptly suppressed “by authority,” and the social annoyances which ensued were painful to a degree.

By her second marriage she had happily only one daughter, Blanche, who married Mr. Lyon, and died childless.

In her old age, Lady Charlotte always kept a lovely portrait of herself standing on an easel beside her, of which the dear old lady used complacently to say, “It is the only picture that ever did me justice!” It was just head and 20shoulders, with the strikingly picturesque head-dress which so well became her, namely a band of black velvet above her fair hair, and above that, fluffy lace, surmounted by a tall pale pink or blue satin cap. I think it was by Sant, and that it was in crayon. (One such remains in the family, but not the one of which I speak.) Shortly before her death it disappeared, and none of the family have ever been able to trace it. Possibly some reader of these pages may be able to afford a clue to its fate.

She died on Easter Day (31st March) 1861, the same month in which my father’s sister Sophia, “Saint Cecilia,” received her promotion to the Celestial Choir.

Lady Charlotte was a daughter of John, fifth Duke of Argyll, who, in 1759, married Elizabeth, the lovely young widow of the sixth Duke of Hamilton, one of the three beautiful Miss Gunnings, whose combined loveliness set first Dublin and then London crazy.[6]

21Maria married the Earl of Coventry, and Kitty, who, from their portraits, must have been the loveliest of all, preferred a quiet country life, and married Mr. Travers.

Elizabeth (or, as she was generally called, “Betty”) was as winsome as she was fair. Curiously enough, her two sons by each marriage succeeded to their respective fathers, so that she had the unique distinction of having been wife of two dukes and mother of four! Her only daughter by the first marriage, Lady Betty, married the Earl of Derby, and of her Campbell daughters, Lady Augusta married General Clavering, and Lady Charlotte married “Beautiful” Jack Campbell of Shawfield and Islay.

He was one of a family of thirteen, of whom Margaret married the Earl of Wemyss; Glencairn (or “Aunt Glen,” as she was called by my older sisters) married Mr. Carter; Hamilton married Lord Belhaven (for many years they acted the part of King and Queen at Holyrood at the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland); Mary 22married Lord Ruthven; Kate married Sir Charles Jenkinson (their daughters Ellen, Catherine and Georgiana married respectively the Duke de Montebello, Mr. Guinness and Mr. Nugent); Elizabeth married Mr. Threipland, and Harriet married Mr. Hamilton of Gilkerscleuch, whose daughter Ellinor married Hamilton of Dalzell.

Of all these, the one who held the largest share in my personal affection was Mary, Lady Ruthven, whose talent for water-colour painting, for music, and her intense appreciation of everything good and beautiful, together with her large-hearted welcome for a wide circle of friends, made a visit to her favourite home at old Winton Castle in East Lothian (one of her own beautiful properties) an ever-recurring pleasure. Some of her own best pictures were of temples in Greece, where she had travelled much in her early married days, about the year 1819, when such travel was a great event.

Lord Ruthven died in his prime, but she lived to the great age of ninety-six; and very pathetic it was to see this aged lady every night place beneath her pillow a beautifully painted miniature of a handsome young man, the love of her youth. In the picturesque old churchyard at Winton is the tall Celtic cross which she erected to his memory, bearing for inscription these words from Dan. X. 19: “O man, greatly beloved, peace be unto thee.”

She was the owner of large mining property, and took the keenest interest in personally visiting the families of her villages with creature comforts for the sick and sympathy for all. As years advanced, she was sorely tried by ever-increasing blindness and deafness, while her heart and mind were active as ever, and longing for information on the politics and literature of the day. In order in some measure to satisfy these cravings, her butler had every morning to read a large part of The Times in a stentorian voice, and in the afternoon one of the footmen read lighter literature. Hence her anxiety to be told of “good novels, 23which will not hurt John’s morals.” But she used to complain pathetically that invariably when they reached the most interesting point, John would close the book and say, “I must stop now, my lady, the butler wants me to clean the silver”—the poor man’s lungs being probably exhausted.

But the most touching incident of the day was the invariable assembling of the large household for family worship, when in a deeply reverent, and perfectly modulated voice, she would recite a chapter of the Bible, of which she knew more than fifty chapters and a great many Psalms by memory, and then offer prayer and praise from the depths of her own heart. Those family prayers were very real.

Very impressive also to me was the unfailing regularity with which the dear old lady invariably marched off to the parish church. If her guests excused themselves on the score of weather, she would say to me, “My dear, we are not made of sugar, and we are not made of salt, so we will go.” And go we did.

I referred to the beautiful modulation of her voice in prayer or in reciting the Scriptures, or poems. Unfortunately as deafness increased, she lost all control of voice in ordinary conversation, and often her newly introduced young guests have been electrified by her deeply resonant tones telling some one else what an excellent parti the young man or the heiress was, and how suitable a match he or she would be for the other!

But such little details as these were but the infirmities of extreme old age of one who, from her birth in 1789 to her death in 1885, lived under four sovereigns, taking a keen interest in all political and national events, from the days of Pitt, and the battle of Waterloo; who had been the chosen friend of Sir Walter Scott, and frequently his guest at Abbotsford; who was intimately acquainted with Rogers and Thomas Moore, Wilson, Lockhart, and a 24multitude of other poets and literary men, including Byron, and most of the leading artists of that long period.

Of my grandfather’s brothers, Robert inherited the estates of Skipness, and Colin those of Ard Patrick. Walter was a naval officer, father of Lady Chetwynd and Lady Trevelyan.

Robert’s son Walter, who was quite an ideal Highlander, wrote various capital books on Indian sport, My Indian Diary and The Old Forest Ranger, by which name he himself came to be generally called. His eldest daughter, Constance, married Macneal of Ugadale, whose delightful home in the Mull of Cantyre overlooks the most magnificent waves and most beautiful sands and golf-links to be found in Scotland.[7]

The two youngest sons, whom I vividly remember as merry, sunny-haired mites, chasing the butterflies among tall lilies and roses in the old garden, are now the Rev. Archibald Campbell, Bishop of Glasgow, and the Rev. Alan Campbell, Episcopal clergyman at Callander. The latter, alas! became blind soon after his ordination, but seems to have found that sore affliction no great hindrance to the success of his ministerial work, so that for several years (ably seconded by his widowed sister, Mrs. David Ricardo) he continued his work among rough dock labourers on the Thames, with whom his influence seemed to be enhanced by his sore affliction.

The Campbells of Ard Patrick also represent an extensive branch of our kinsfolk—the one who has entered most largely into our lives being Ellinor, who married Michael Hughes, who for many years rented Huntly Lodge, and made it a centre of hospitality so long as they lived.

Almost all these thirteen grand-uncles and grand-aunts married, and the majority left children, and children’s children, to further extend the family connections.

25These were equally numerous on my father’s side, his Grandfather, Alexander Cumming or Cumyn, having in most romantic fashion, when semi-shipwrecked off the coast of Cornwall, wooed and won Grace Pearce, niece and heiress of John Penrose of Penrose, who was the last heir male of that ancient family. On the lovely estate of Penrose close to Helston, the young couple abode; and in the old charter-room at Gordonstoun are preserved some quaint letters concerning Cornish customs,[8] especially the value of the many wrecks, which were commonly spoken of as God’s blessings. In the same old charter-room there is also a brief memoir of his father by the eldest son, Alexander Penrose, in which he tells of his father’s start in life as a midshipman on board H.M.S. Trafford, whence he was transferred to H.M.S. Kent, and sent to the West Indies.

On the voyage he deemed himself insulted by a lieutenant, so on arriving at Port Royal in Jamaica he called him out, wounded and disarmed him. But as such a breach of discipline as a middy fighting a lieutenant would have made his life in the navy a burden, he resigned his naval career, and enlisted as a grenadier in Harrison’s Regiment, till he was able to buy his commission, and distinguished himself at the storming of Boccachica.

At Jamaica, he was stricken with fever; thence the regiment was ordered to Ostend, which was then held by the Austrians and besieged by the French. The siege lasted for three years!

After a brief interval at Portsmouth, the regiment was ordered to Ireland in transports, but these were compelled by stress of weather to seek refuge at Falmouth, where all the regiment was disembarked and remained in cantonments for some time till the damaged ships could be repaired.

At a ball in Falmouth, the young heiress of Penrose graciously signified her willingness to dance with any of 26these shipwrecked officers with the exception of “that ugly Scotchman,” Captain Cumyn, who, however, was not long in finding favour with the lady; and being for some time encamped at Penrhyn, he made such good use of his opportunities, that when the regiment again set sail for Ireland, Captain Cumyn and his bride were happily settled at Penrose.

In due time they were blessed with six sons and three daughters, most of whom married county neighbours. Hence our kinship with the Rashleighs, Veales of Trevayler, Fitz-Geralds, and Quickes of Newton St. Cyres.

Alexander survived his wife, and died at Penrose in 1761. That estate was subsequently sold to make provision for the eight younger children, apparently in total ignorance of the valuable tin mines on the estate, which are said to have sometimes yielded more in one year than the total price paid for the whole property.

Their eldest son, Sir Alexander Penrose Comyn, who was born at Helston in May 1749, assumed the name of Gordon, when, on the death of Sir William Gordon of Gordonstoun, and in right of his ancestress, Dame Lucy Gordon, he succeeded to that property[9] with its delightfully quaint old house, a mile from the sea, and from the enchanting coast of broad yellow sands stretching on either side of sandstone cliffs and large caves of very varied form, 27which extend along the shore for a couple of miles, forming at low water the most fascinating rock scenery I know of in Britain or elsewhere, and a truly entrancing playground.

Gordonstoun is only sixteen miles from Altyre, but is in every respect as complete a contrast as could well be imagined: the one a simple old Scotch house, with patchwork additions, all embowered in greenery and blossom, and the other a stern, uncompromising, large grey mansion, with steep-pitched roofs, slabbed with grey and lichened stone, and turrets at all corners. Only when inside does the explorer discover traces of the successive generations which have produced it—the extraordinary dungeons, the secret stairs and quaint hiding-places in the thickness of the walls, behind cupboards, or under floors. Surely no children ever possessed more delightful homes!

My grandfather did not go far afield in search of a bride. At Castle Grant, which had for at least eight hundred years been the headquarters of the Chiefs of Clan Grant, he found his bride Helen Grant of Grant, one of the six daughters of Sir Ludovick Grant of Grant by Lady Margaret Ogilvie-Grant, eldest daughter of James, Earl of Findlater and Seafield. Sir Ludovick was a fine specimen of the true Highland chief of the best type, and while not neglecting the estates, he represented the County of Elgin as M.P. for twenty years, from 1741 to 1761. He died at Castle Grant 18th March 1773.

His only son succeeded as Sir James, whose sons, Lewis 28and Francis William, successively became Earls of Findlater and Seafield. Thus “Dame Helen”—my grandmother—was aunt to the fifth and sixth, and grand-aunt or great-grand-aunt to the seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth, and eleventh earls. Was ever succession so rapid in any other family?

Of my five grand-aunts, Hope Grant married Dr. Waddilove, Dean of Ripon, and Penuel married Henry Mackenzie, author of The Man of Feeling, a volume very much admired in its day. One of their sons, John Henry, was an eminent lawyer, and was raised to the bench as Lord Mackenzie, generally called “of Belmont” to distinguish him from two later law lords, who each took the title of Lord Mackenzie.

He married the Honourable Helen Anne Mackenzie of Seaforth.

Sir Alexander and Dame Helen had fourteen children besides MY FATHER, and Uncle Charles Cumming-Bruce. Their Daughter Helen Penuel married Sir Archibald Dunbar of Northfield and Duffus; the latter, which is the family home, being only one mile from Gordonstoun, the Dunbars have ever been our very closest kinsfolk. That couple were blessed with ten children, one of whom married Mackintosh of Raigmore, near Inverness, and became the mother of some of our dearest relations.

Her eldest son Eneas, generally known in our family as “the Beloved,” was the very incarnation of genial hospitality, and many a joyous gathering have we all held under his elastic roof, especially at the annual great Highland meeting every September. Never was the fine old proverb

better illustrated, for when the utmost possibilities of packing seemed to have been attained, there was always some corner found for an extra guest.

He married a sister of Sir Robert Menzies of Menzies, and thus began our life-long close intimacy with Perthshire, 29and especially with Sir Robert’s beautiful wife, née Annie Alston Stewart, and her sisters, two of whom owned Killiecrankie Cottage, overlooking the famous Pass. Many a happy week have I spent in that exquisite nest, and at Urrard on the opposite bank of the Garry.

Another of Aunt Helen Dunbar’s daughters married Rawdon Clavering, and another, Mr. Warden.

The eldest and third sons, Sir Archibald and Edward, lived till January 1898, when they passed away within a few days of one another, Sir Archibald in his ninety-fifth, and Edward in his eighty-first year.

Then we were all electrified when the newspapers informed us that the cousin whom we had always distinguished as “Young Archie” was actually verging on threescore years and ten! His mother was Keith Alicia Ramsay of Barnton, and his wife was Isabella Eyre of Welford Park. His father married, secondly, Sophia Orred of Tranmere Hall, in Cheshire, and in 1890 they celebrated their golden wedding in the same year as the younger couple celebrated their silver wedding.

Sir Archibald, senior, was always a fragile invalid, in pathetic contrast with my stalwart brothers. But he was wont to say, “A glass box will last as long as an iron one, if you take care of it.” And he did take such care of his glass box, that he outlived all save one of my brethren.

Both he and his cheery brother Edward were storehouses of learning on all points concerning old Scotch lore, especially on local subjects, and they were the last survivors of those to whom we could refer any disputed questions. Edward’s delight was in puzzling out quaint letters in the old family charter-rooms, many of which he published in three volumes, entitled, Social Life in Former Days and Documents Relating to the Province of Moray.

His elder brother’s chief delight was in his gardens, and in proving how excellent is the soil and climate of “the Laich” or lowlands of Moray for the growth of fruit, 30especially pears, apples, plums, and small fruits. Great was his satisfaction when some of his pears took the first prize at Chiswick, in days when most folk south of the Tweed still believed Scotland to be a land where a semi-civilised race lived on oatmeal! How anxiously he watched the ripening of the first fruits of new varieties, and then at the exact right moment he brought the precious fruit, divided into sections that we might each give our verdict of its merits.

These two dear old brothers lived about twelve miles apart, Edward’s home being at Sea Park, about a mile from Findhorn Bay, and their great pleasure in later days was an occasional visit of one to the other. Both retained all their mental faculties perfect to the very end, and were only laid aside by bodily illness for a brief period. When, on 6th January 1898, Sir Archibald passed away, Edward being unable to attend his funeral, telegraphed to his son the Rev. John Archibald, to come from London to take his place. Obedient to his summons, the son reached Sea Park on 11th January, just in time to witness his father’s death ere attending his uncle’s funeral, returning thence to make the necessary arrangements for that of his father.

To return to my father’s numerous sisters. Margaret married Major Madden of Kellsgrange, in County Kilkenny, and from her descend our Mortimer cousins. Edwina married Mr. Miller of Glenlee, the eldest son of Lord Glenlee, the judge, and her son succeeded to the baronetcy. She was one of the kindest-hearted women that ever lived, but she was sorely tried by the number of grandchildren who accumulated around her. One of these having died, a friend called to express polite regret, and was somewhat startled at the truthful, though unconventional reply, “Oh! my dear, do not condole with me. There is much more room for it in heaven than in my house!”

Louisa married Lord Medwyn, who, like Lord Glenlee, was what is known in Scotland as “a law lord,” the wife not 31sharing his title, but being simply Mrs. Forbes of Medwyn. Her eldest son, William, married Miss Archer Houblon. Their daughter Louisa married Sir James Ferguson, and Mary married Lord Mar and Kellie.

The second son, Alexander, became the saintly and greatly beloved Bishop of Brechin. He was greatly helped in church-work by his sisters Helen and Elizabeth (commonly called “Buffy”). Helen, under the name of “Zeta,” published many lovely songs—in fact all this branch of the family have been specially distinguished for musical talent.

Their sister Louisa Forbes married Colonel Abercromby, eldest son of Lord Abercromby, whose delightful home, Airthrie Castle, lies at the foot of the Ochils, between romantic Stirling and Bridge of Allan. Her only daughter, “Monty,” married the Earl of Glasgow.

In those days party politics ran so high as to mar many a happy courtship, and as all the Forbes and Cumming connection were uncompromising Tories, Louisa’s engagement to the son of a staunch Whig family aroused much opposition. Nevertheless love carried the day, but her mother’s parting counsel on the wedding day was delightfully characteristic: “Well, daughty” (i.e. dearie), “you’ll sometimes hear something good about the Tories, and I’ll tell you what to do then. Just go to your own room and lock the door, and have a bit dance by yourself!”

Four of my father’s sisters who did not marry, namely Jane, Mary, Emilia, and Sophia, lived together with their mother, Dame Helen, in her dower-home, Forres House, three miles from Altyre; and on her death, they rented Moy on the other side of the river Findhorn, and were familiarly known as “the Moy Aunts.”

The eldest of the four, Miss Jane, was considered the cleverest, and she certainly was the managing partner, much given to having a finger in every pie, in a fashion which did not tend to make her popular with her younger relations. She was noted for her ready wit, of which, however, only 32one instance now occurs to me. There had been a dispute between several of the neighbouring proprietors concerning certain boundaries, and they were disposed to carry the matter to the law-courts. At last one not interested (I think it was MacPherson Grant of Ballindalloch on the Spey) stepped in, and decided the matter to the satisfaction of all concerned, whereupon the disputants resolved to present him with a thankoffering, and what could be so useful as a silver hot-water jug for the brewing of the toddy (whisky with boiling water and sugar), which invariably ended every dinner, no matter how great had been the variety of wines consumed, and of which every lady present accepted a wine-glassful from the tumbler of the gentleman next to her, doled out with a silver ladle.[10]

But now the question arose what would be a suitable inscription, and here again much discussion ensued, when happily Miss Jane entered the room, and all agreed to refer the decision to her. Without a moment’s hesitation she replied, “Presented to Ballindalloch to keep him in hot water, for keeping his friends out of it,” a neat solution of the difficulty, which was accepted with acclamation.

The handsomest sister, Emilia, was beloved by Charles Grant, who afterwards became great in law, and assumed the title of Lord Glenelg. But her kinsfolk refused to sanction her marriage to a young Whig barrister, so they were compelled to part, but each remained constant to the memory of the other till death reunited them.

Sophia, a fair-haired, gentle little soul, was an exquisite musician, and was accounted a sort of Saint Cecilia. There was a charmingly mellow old organ in the dining-room at Altyre, on which she was wont to play divinely. My brother Henry likewise delighted in it. After my father’s death, it was transferred to the Bishop of Brechin’s Church at Dundee.

In common with all the family, all these sisters were 33great pillars of the Episcopal Church in Forres, that singularly inconvenient cruciform chapel which was built in 1841. (Prior to that date there seems to have been no Episcopal service in the town since 1745.) Many of the congregation drove very long distances every Sunday; and it must have been bad weather indeed when the Cumming-Bruces from Dunphail were missing, though they had to drive eight miles, and others came from still further.

For some time there was no parsonage, and the first incumbent, the Rev. Alexander Ewing, afterwards Bishop of Argyll and the Isles, lived at lovely Logie on the Findhorn, the property of our cousins, the Cummings of Logie. He was a charming personality, and continued one of our dearest friends till the day of his death.

His first wife was a daughter of General Stewart of Pittyvaich, in the valley of Mortlach, in Banffshire. Her sister Elizabeth married my brother Henry, and Clifford married Canon Robinson of Norwich Cathedral, who is also Master of St. Catherine’s at Cambridge. She was one of the best-loved women in either city, and one of Dean Goulburn’s most pathetic utterances was his address in Norwich Cathedral on the occasion of her funeral. To the grand teacher, whose motto was “Detest affectation” (how often I think of him when I see women raise their elbow at a right angle when they shake hands!), her perfectly natural, genuine sweetness and cordiality to every one especially appealed.[11]

Mr. Ewing was succeeded at Forres by the Rev. Hugh Willoughby Jermyn, who was afterwards Bishop of Colombo in Ceylon, and when driven back to the home-land in shattered health, was appointed to succeed my cousin, Alexander Forbes, in the Bishopric of Brechin, and elected Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland.

On my birth (26th May 1837), within six hours of that interesting event, I was sent to Moy to the care of my father’s four unmarried sisters (generally known as “the Moy Aunts”), because scarlet fever reigned at Altyre; my brother Walter Frederick and my sister Constance had just died of it, and Eleanora lay in imminent danger, so a carriage was in readiness to take away the precious baby and her wet-nurse as quickly as possible. Thus my travels began early, though thirty years were to elapse ere opportunity offered for going further afield than Great Britain. It was to the death of this brother and sister that I owe my name, Constance Frederica; but though my mother wished to keep both names, she shrank from using either, and so took the sound of the end of the second name, and called me Eka, the only name by which I have ever been known in my own family. It was not till school days that the more dignified Constance came into use.

My memories of the next five years are necessarily very 35limited. I recollect my mother’s glorious masses of hair falling in clustering ringlets far below her waist. I remember her lovely songs and her joy in the great beautiful gardens of her own creation, and those stands of “dusty millers”—large very varied auriculas—which were the gardener’s special pride, and above all, the greenhouse on one side of the house, which was the very first greenhouse in Morayshire. Among its delights was a fragrant mimosa-tree covered with sweet yellow blossom, and a large white jessamine with shining leaves, clustering round upper windows, which, looking into the greenhouse, had the full benefit of all its sweetness.

How she joyed in every new variety of favourite flowers, the splendid fuchsias, the large blue aquilegia (Brodie Columbine), and the bright blue salvias, whose store of honey too often proved as irresistible to her naughty child as to her friends, the bumble bees—a friendship shared with the fat, ugly toads which the gardeners cherished.

To my mother the staff of under-gardeners were not merely “hands.” She took the keenest interest in providing them with all the best books on botany and horticulture, and many successful gardeners scattered over the world owed their start in life to her encouragement. A conspicuous example was that of Jamie Sinclair, who, during the Crimean War from 1854 to 1856, was found in charge of Prince Worenzow’s beautiful gardens, and who rejoiced to tell the British officers of his start from the Altyre gardens.

I find an interesting reference to him, and to my mother’s care for her employés, in a paper in The Cottage Gardener (dated about 1856), by Mr. D. Beaton, head gardener to Sir W. Middleton at Shrubland Park. He tells how he himself had his earliest training in the gardens at Beaufort Castle, whence he passed to Altyre. “The collection of plants there,” he says, “was immense, and I was at the head of them in less than a twelvemonth. I had access to all the books and periodicals on gardening.

36“Here I first began crossing, budding plants, and bulbs, three favourite pursuits with Lady Gordon-Cumming, who after many years sent seeds of her crossed rhododendrons to Shrubland Park at my instance.”

I have a letter to my mother from her second daughter, Ida, telling as a great secret of her hopes and persevering efforts to obtain a blue geranium by crossing the wild crane’s bill with a very pure white pelargonium. The result, however, is not recorded.

Mr. Beaton goes on to say: “The great African lionhunter, Sir William’s second son, was then learning his lessons in books and horsemanship; he was the handsomest boy in all Scotland, and so fond of fun and dancing, that we could have a ball and supper any night in the year, through his influence with ‘Mamma.’ Jamie Sinclair, the garden-boy, was a natural genius, and played the violin. Lady Gordon-Cumming had this boy educated by the family tutor, and sent him to London, where he became well known for his skill in drawing and colouring.

“Mr. Knight, of the Exotic Nursery, for whom he used to draw orchids and new plants, sent him to the Crimea to Prince Worenzow, where he practised for thirteen years. He laid out those beautiful gardens which the Allies so much admired; had the care of a thousand acres of vineyards belonging to the Prince; was well known to the Czar, who often consulted him about improvements, and who gave him a ‘medal of merit’ and a diploma, or kind of passport, by which he was free to pass from one end of the Empire to the other, and also through Austria and Prussia. He was the only foreigner who was ever allowed to see all that was done in and out of Sebastopol and over all the Crimea.”

Throughout her brief, bright life, my mother’s influence was always exerted for good, as beseemed one who was a reverent student of the Holy Scriptures. She and most of her sisters were keenly interested in the subject of prophecy, and eagerly studied every new book that appeared thereon. 37Both she and my father were careful to train their children in reverent love for the “Holy Book,” and in the practice of learning by heart at least one verse every day. I think the very first which I thus learnt was the Psalm from which, at the beginning of these “Memories,” I have quoted a verse in the past tense, which sixty-five years ago she taught me in the future tense.

When her favourite son, Roualeyn, on his deathbed, surprised us all by his knowledge of the Holy Scriptures, he told us that through all his stormy life he had never been parted from the Old Book given him by his mother, so that his mind was like a well-built fire, ready to respond to the Divine spark, which at last kindled it so effectually.

Natural as was the worship with which her sons regarded their beautiful mother, it was doubtless accentuated by her keen personal interest in all their pursuits; and amongst minor details, I can remember the skill with which her firm, capable hands tied those beautiful salmon and trout flies which beguiled so many bonnie fish—an art in which her sons became equally adept; and no more acceptable gift could reach them from far countries than gay feathers with which to try new experiments.

Perhaps some fishermen may like to know a little secret confided to me by my brother Roualeyn, which was, that when the fish were sulky, refusing his best flies (N.B. Fish invariably means salmon) he would let them rest a while. Then, tying a bit of tackle off a common rook’s feather on to a common bait-hook, he would let it float down stream, and almost invariably captured some inquisitive fish which came up to look at it.

To me, to whom sewing in any form is as hateful as having to do the simplest sum in arithmetic, it seems somewhat remarkable that, notwithstanding the very varied occupations of my mother and elder sisters, they all excelled in needlework, both useful and ornamental. They would gather a handful of graceful flowers, and then and there, 38with coloured silks, reproduce them on red cloth stretched on an embroidery frame. Some of these are still in the possession of daughters or grand-daughters, and are so fine that each would seem as though it must have taken months of toil.

All my mother’s daughters were endowed with much of her own artistic talent, and delighted in painting both in oil and water-colour, fired thereto by frequent visits from such artists as Sir Edwin Landseer, Sir William Ross, Saunders, Giles, and others.

Among the early details which most impressed themselves on the memory of the “Baby” of the home was the wonderful “Birthday Chair,” which on the 26th of May was always prepared for her use at all meals. Early in the morning the elder sisters went out and presently returned laden with boughs of delicious lilac and graceful golden laburnum. Tall willow-wands, tied to a high wooden armchair, formed the light framework to which were fastened this wealth of fragrant spring blossoms—a lovely bower wherein the happy child sat in truly regal state.

This pretty custom was kept up till my ninth birthday, and the lilacs never failed us. Nowadays I doubt whether a solitary spray would be found in blossom in the North, just as in those days all the girls reserved their daintiest muslins to wear at the Inverness Games in September. Now wisdom and comfort alike demand warm tweeds. And as to the delicious ripe peaches which we used to gather on the open wall, the modern gardeners hear of them with polite incredulity. Are we returning to a glacial epoch?

Emery Walker, ph. sc.

Eliza Maria, Lady Gordon-Cumming of Altyre.

Painted by Saunders about 1830.

Among my vivid memories of about 1840 were certain evenings when my mother returned from distant expeditions escorted by several gentlemen, whom I now know to have been Sir Roderick Murchison, Hugh Miller, Agasis, and other eminent geologists, who at that time were deeply interested in the newly discovered fossil fish in the Old Red Sandstone in Ross-shire, on the other side of the Moray 39Firth. Similar fossils had just been found in the Lethen-bar Lime Quarries, on the other side of the Findhorn.[12] These were a source of keen interest to my mother, and it was to search for more that the geologists were invited to Altyre.

Evening after evening there was great excitement in carefully lifting from a dogcart the spoils of the day, namely grey nodules which, when gently tapped with a hammer, split in two, revealing the two perfect sides of strange fossil fishes, with the very colour of the scales still vivid. Day by day my elder sisters patiently made minutely accurate water-colour studies of these, and the best specimens were sent to the British Museum, where they still remain, and where certain fishes hitherto unknown, were called after my mother.

The poorer specimens were deposited in rows under the verandah, and there remained as familiar objects of our early days.

On other evenings there was the home-bringing of various game, furred and feathered, or of bonnie speckled trout from the Altyre burn, the Loch of Blairs, or Loch Romach (the latter a curious, long, narrow loch in a ravine between densely wooded hills); but the special excitement lay in the silvery salmon caught in the Findhorn by my father, mother, and brothers, all of whom were skilful fishers. The keepers loved to tell of one day when my mother caught, played, and landed eight fine fish to her own rod. Those who know the rocky bed of the beautiful river, hemmed in by steep banks, can appreciate the difficulty of such fishing-ground for a lady, especially one of goodly proportions. In those days it was very exceptional for ladies to venture on salmon fishing.

On one occasion she had a very narrow escape of being washed away by one of those tremendously rapid spates which now and then occur after very heavy rainfall in the upper districts, when the river, without any notice, comes 40down in a gigantic flood-wave. She was standing in midstream, quietly fishing, when suddenly a thunderous roar of waters, effectually drowning the ordinary sound of the rushing, swirling river, warned her of something unusual. She leapt from rock to rock, back to the bank, and had scarcely time to scramble up the steep footpath ere a seething torrent, more than eight feet in depth, was dashing over the spot where she had been standing.

Most delightful of all to the little, fair-haired child with the long, yellow ringlets was the joy of delightful drives, sitting “bodkin” between the indulgent parents who so patiently endured the bumping up and down of the odious brat who tried to keep time with the postillion.

At that time postillions were the fashion, and the extra men to be entertained when the house was full of company (and Altyre always was full) must have been considerable—and visits were wont to be indefinitely prolonged. When Colonel (afterwards sixth Earl of Seafield) and Mrs. Grant of Grant used to come down from Castle Grant they always had four horses and two postillions, two outriders, valet, and lady’s-maid. So that entertaining one couple meant also five men, a maid, and six horses.

Every year there was a season of sore bereavement for us children, when our parents and older sisters started on the long drive of six hundred miles from Altyre to London for the season, posting all the way. Occasionally their journey was continued to Paris, and several large excellent copies at Gordonstoun of pictures in the Louvre tell of the special permission to paint there, granted to them by personal favour of Louis Philippe, in days when such permits were not easily obtained.

Among my treasured relics are several letters to me from my mother, written during her last absence, when I was just four years old. With these precious letters there are several locks of exquisitely fine yellow hair, like spun glass, each folded in the gilt-edged paper, which was then the 41correct note-paper. They are marked in my mother’s writing as being my own hair at three weeks old, and the idolised brother and sister who died when I was born. One lustrous lock is marked by my father as that of his beautiful boy “Roualeyn,” “Robh Ailean,” two Gaelic words of which, curiously enough, no one can tell us the connected meaning. Robh would be pronounced row, like “to row a boat,” and “ailean” means white. It is possible that my mother took the name from Rowallan Castle, three miles from Kilmarnock, which was built about 1270, in the reign of King Alexander III. of Scotland, by the son-in-law of Sir Walter Comyn of Rowallane. But that would not account for my father spelling his son’s name as above. It is a grand name, but its owner was generally known in the family as Zoe.

By the time of my birth he was a beautiful lad, captivating all hearts, and worshipped by the people, in whose eyes he could do no wrong. I am not sure, however, that his tutors always shared this view of the case. One in particular was a young theological student, so exceedingly minute that when he stepped down from the gig which had been sent to meet him, and my father perceived the infinitesimal mortal who had come to take charge of his stalwart sons, he could not resist the joke, but catching him up in his arms, carried him to the room where my mother and other ladies were sitting, and set him down exclaiming, “Eliza, here’s the new dominie!!”