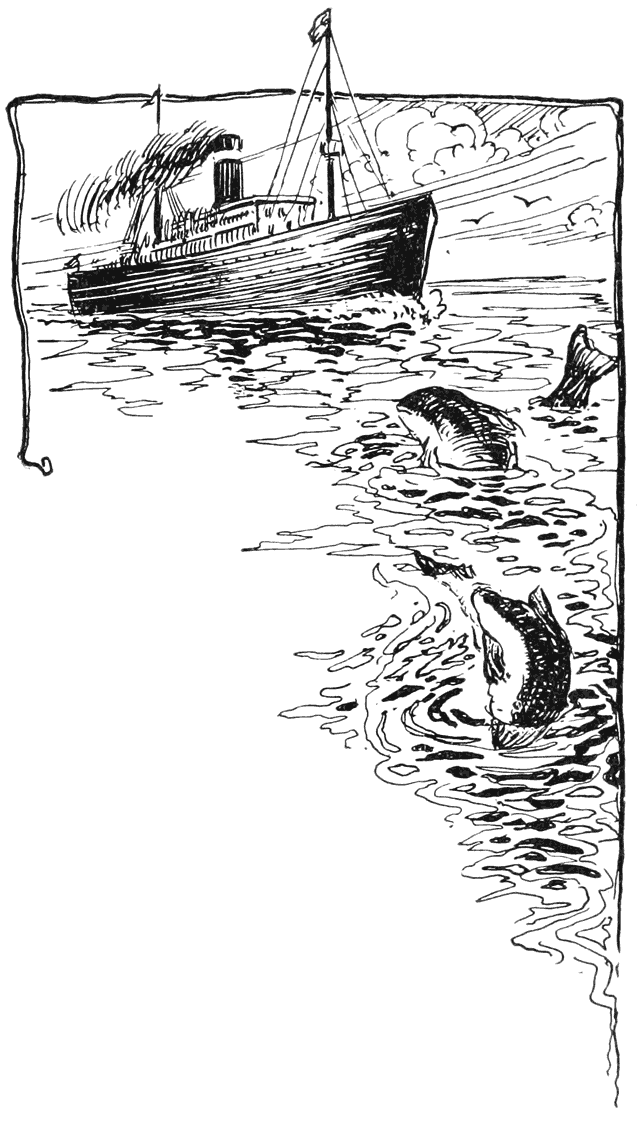

Early one morning, after a stormy night, the workmen in a great seaport found a little

girl upon the shore. She was lying with nothing on but a little shirt, dripping wet

upon the sands, and gave no sign of life. At some distance from the beach they saw

the top of a mast rising from the water. A large ship had gone down with all on board,

and the waves had brought to land only this one little girl.

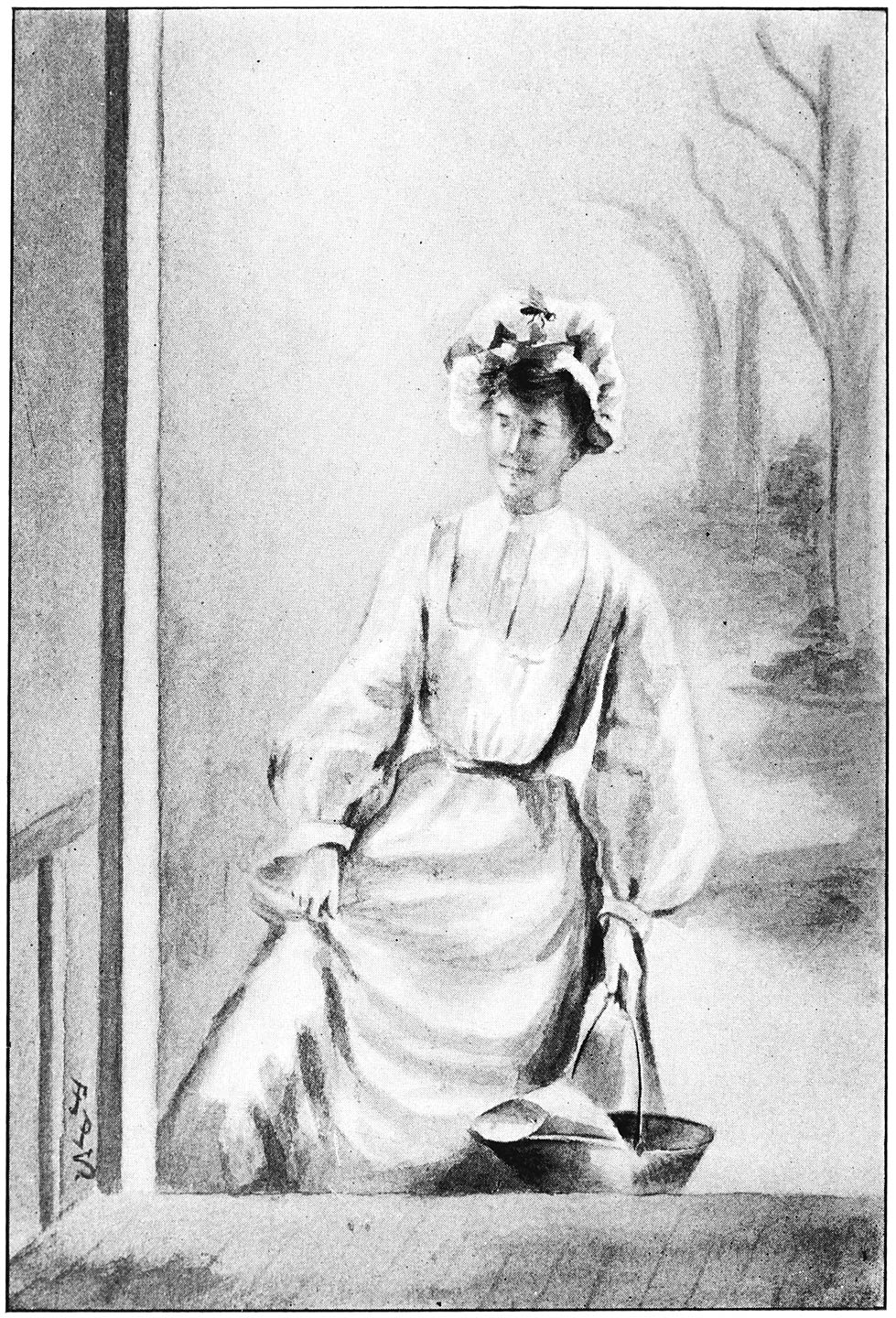

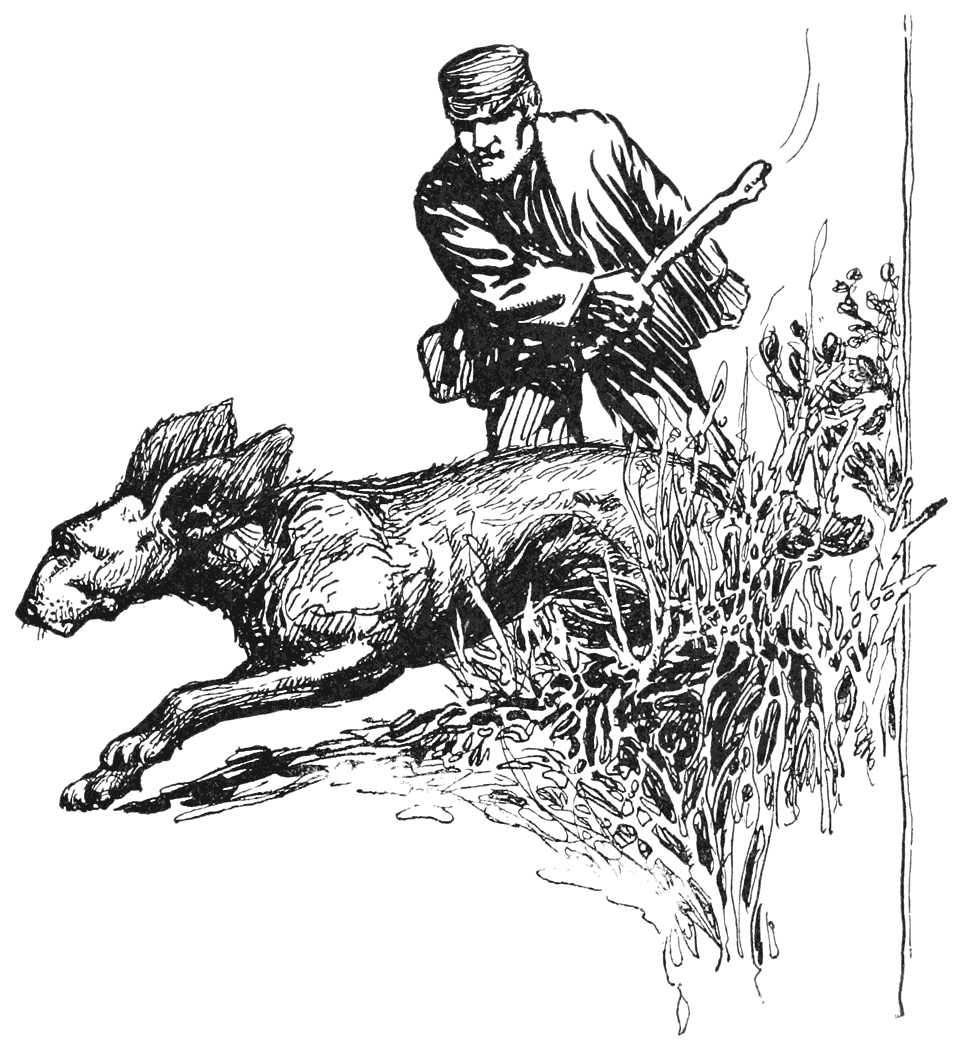

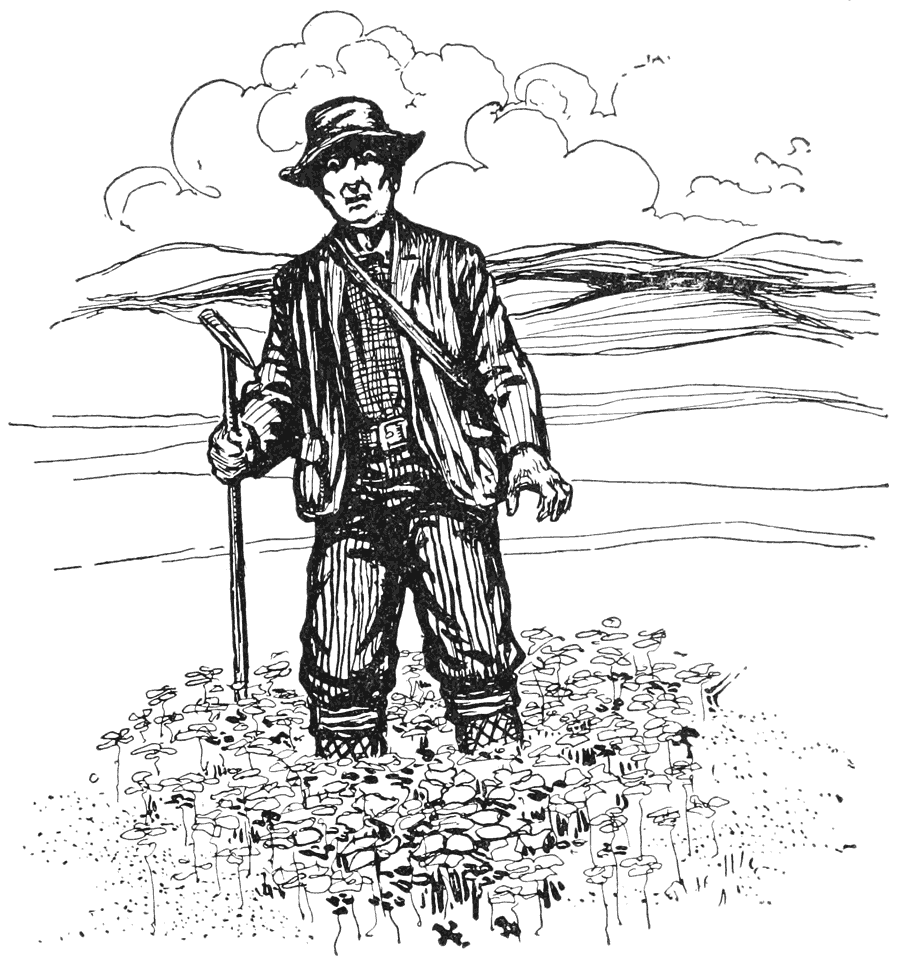

A compassionate laborer took her up, wrapped her in his cotton blouse and carried

her quickly to the neighboring office of a tidewaiter, where her wet shirt was removed.

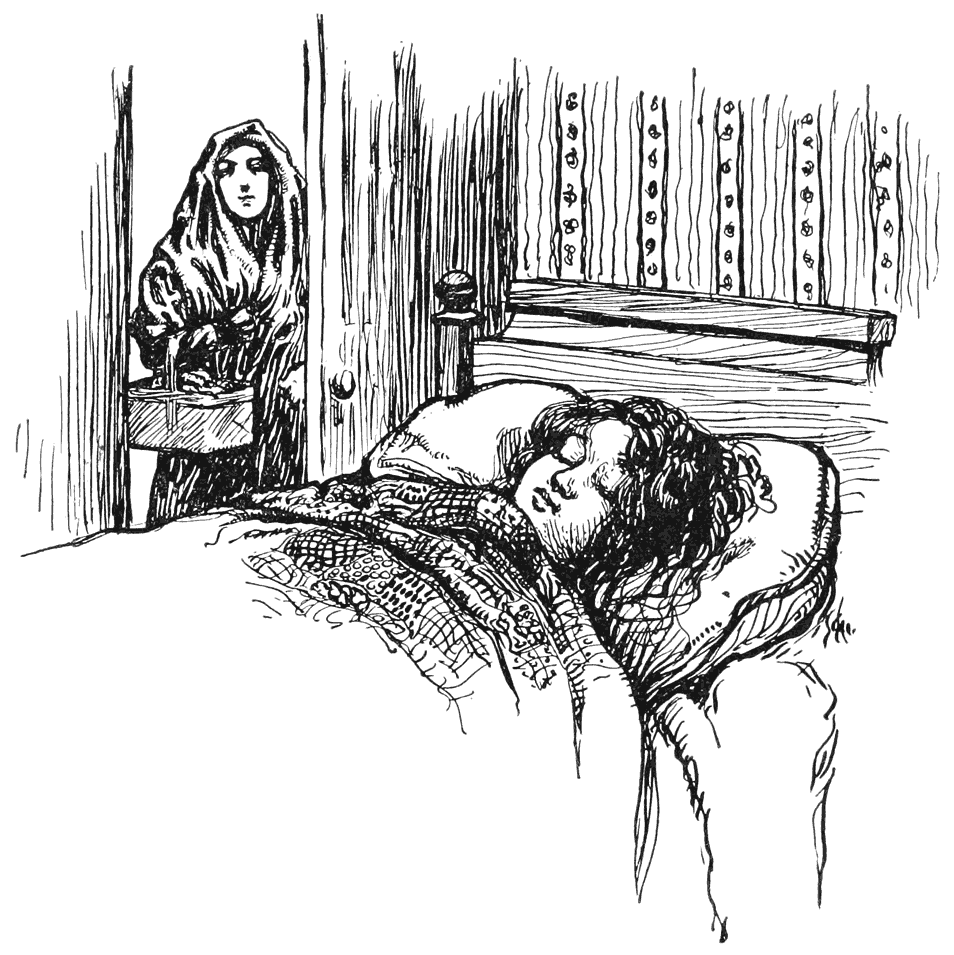

She was laid on a bench and covered up. As soon as she grew warm, she opened her eyes,

and began to cry.

Everybody in the office admired the child’s delicate form, beautiful little rosy face,

big blue eyes, and fair silken curls. The little shirt was made of the finest cambric,

and embroidered with a gold coronet. Even without this mark it was evident that the

child cast by the shipwreck on a foreign shore was of aristocratic birth, and had

been carefully tended.

When the baby cried, the men standing around were [304]very sorry, but they did not know what to do, for they did not understand how to take

care of little children; and, besides, they did not have on hand what was necessary

to satisfy its wants. The child had not yet cut all its teeth, and could only stammer

a few words in an unknown tongue.

The men consulted together, and soon agreed that the baby must be hungry and need,

first of all, food and clothes. There was nothing in the office except some horrible

brandy. But close by there was a sailors’ tavern, where they could get some milk and

biscuits, which the little girl ate readily. When she had had some food, she stopped

crying and fell asleep.

The tidewaiter was obliged to attend to his duties and could not stay with the child.

The kind laborer who had carried her into the office also had to work, for he was

a poor man, and if he lost a day’s work, he and his family would have nothing to eat

the next day. Yet he could not make up his mind to leave the lovely little girl. Rolling

up the wet shirt, he put it carefully in his big blue calico handkerchief, and slipped

it into the wide pocket of his trousers. Then he again wrapped the poor, naked little

creature in his blouse and in a woollen blanket, which the tidewaiter lent him, and

went home with his precious burden in his shirt sleeves, though he did not consider

it quite the proper thing for a respectable workingman and the father of a family.

“Hitherto you have given me children,” he said to [305]his wife, as he placed the little one in her hands, “now I will give you one.”

The woman gazed at the present with astonishment and no special pleasure; she thought

that her own five children were enough. But when her husband told her how he had found

the little girl, her mother heart was touched with pity and she said: “Where five

are fed, a sixth can eat too. We will keep the little one, if no one claims her.”

So the little girl was adopted into the workman’s family, and the next Sunday he went

to report it. The magistrate pondered over the name that should be given to the stranger

child. A gale from the north had driven her ship on the shore. It had probably come

from the north. Yet the child might have been born in the south. So he called her

by a name half Greek, which is a southern, and half Danish, which is a northern language,

Margarita Bölgebarn, that is, Pearl, the child of the waves, and urged her foster-father

to take great care of the little shirt, with the tiny embroidered gold crown, in which

she was found, as with its help perhaps the child’s relatives might some day be discovered.

Many ships had been wrecked during that stormy night, and it was never known which

one had carried the child. No one appeared to claim it, so it remained with the workman

and grew up with his children. Rita—as they called Margarita to shorten her name—grew

finely, although she did not fare well with him. It was [306]very hard for the man to support himself and his family. They were often on short

commons, and when there was not enough to eat for all, Rita had to wait until the

others left something for her, and frequently went without entirely. Her foster-mother

was not a bad woman, but poverty had made her hard, and her own flesh and blood came

nearer to her than the foundling whom she had adopted. She did not grudge her a little

place in the miserable home, but she was not allowed to cost anything; for the father’s

scanty earnings did not permit it.

Rita slept in the same bed with the two youngest children, who pulled the scanty coverlets

over them and left Rita half uncovered, so that in the winter nights she was bitterly

cold, and nestled closely to her foster-sisters to get some warmth from their bodies.

She turned over often, because this was the only way she could warm her right and

left side in turn; but this disturbed her bed-fellows, and they cuffed and kicked

her. She bore it, and only wept secretly, because it was still dark, and no one could

see her. She was dressed in the clothes of her foster-sisters, after they could not

or would not wear them any longer. So she usually went barefoot, and wore shabby,

patched, shapeless garments. But though she looked like a scarecrow, every one who

saw her noticed her remarkable beauty. Her little bare feet, though sunburnt and soiled

by the mud of the streets, were as exquisite in form as if chiselled [307]by the hand of a skilful sculptor; her face was fair, rosy, and lovely; her large

blue eyes were soft and dreamy, and her silken curls, carelessly as they were arranged,

seemed like sunbeams playing around her beautiful head. Wherever she went, people

stood still in the streets and looked after her. They thought she must be some aristocratic

girl, who, for a whim, had disguised herself as a beggar child.

This did not escape the notice of her foster-sisters, and they envied her for her

beauty, and because she attracted attention wherever she appeared. They made her feel

more and more plainly that she was a foundling living on their charity. Everybody

vied in giving her orders, and required her to obey them. Everybody made her serve

as a maid-servant waits upon strict employers. She had to sweep the rooms, and once

a week scrub and polish the floor. She had to light the fire in the kitchen every

morning, and every evening, until late at night, clean the shoes of her foster-parents,

her four foster-sisters, and even her foster-brother. She was obliged to do all the

errands, and if there was no money in the house, let herself be scolded because she

did not pay the debts and beg them to let her have still more on credit. She was so

scantily dressed that the neighbors took pity on her and gave her all sorts of things,

some shoes, another a skirt, a third a waist, a fourth a shawl, each one what she

had and could spare. She went hungry, too, and when they saw it, people secretly gave

her in [308]the houses, the shops, and at school, a bit of bread and end of sausage, an apple,

or a piece of Dutch cheese. As she was always gentle and kind, never spoke in a loud

voice, never quarrelled, never uttered an improper or a coarse word, her foster-sisters

jeered at her and scornfully called her the princess. For they all knew that she was

found in a fine little shirt with a small gold crown embroidered on it; they had seen

the pretty garment themselves, though their father kept it carefully wrapped in paper

in a drawer, and did not often bring it out to show any one, and when they thought

that perhaps Rita really was a royal child, they were provoked, yet at the same time

it gave them a spiteful pleasure to have a princess subject to the children of a plain

workman, and obliged to do the most menial tasks for them.

From the time Rita was old enough to understand her position, she, too, thought constantly

about her origin, and busied herself waking and sleeping about the secret of the little

gold crown embroidered on her shirt. She had an eager longing to see and touch the

dainty linen; but she did not dare to ask, for once, when she did so, her foster-father

roughly refused, saying harshly, “Don’t think about it; it would only fill your head

with silly notions.”

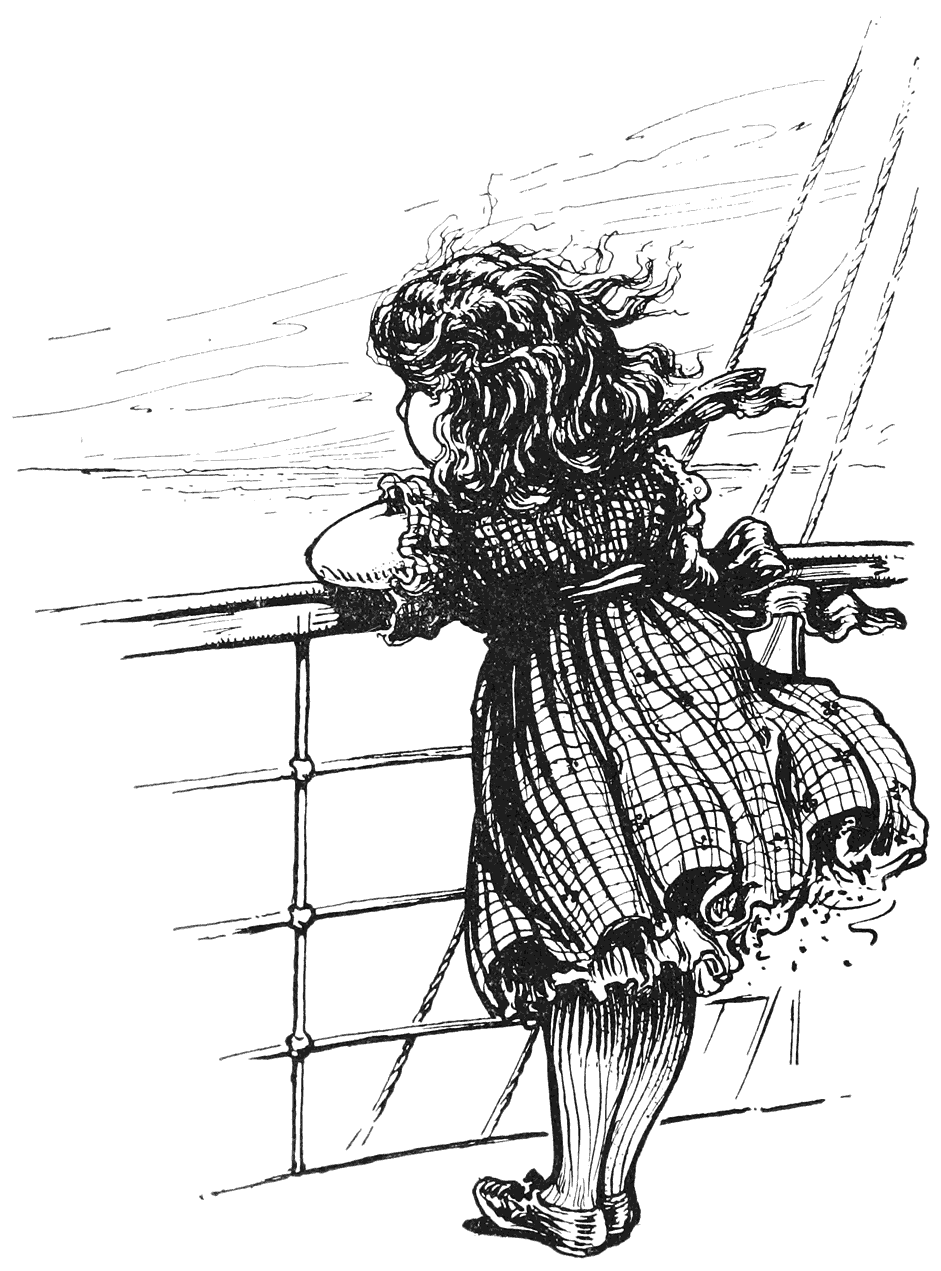

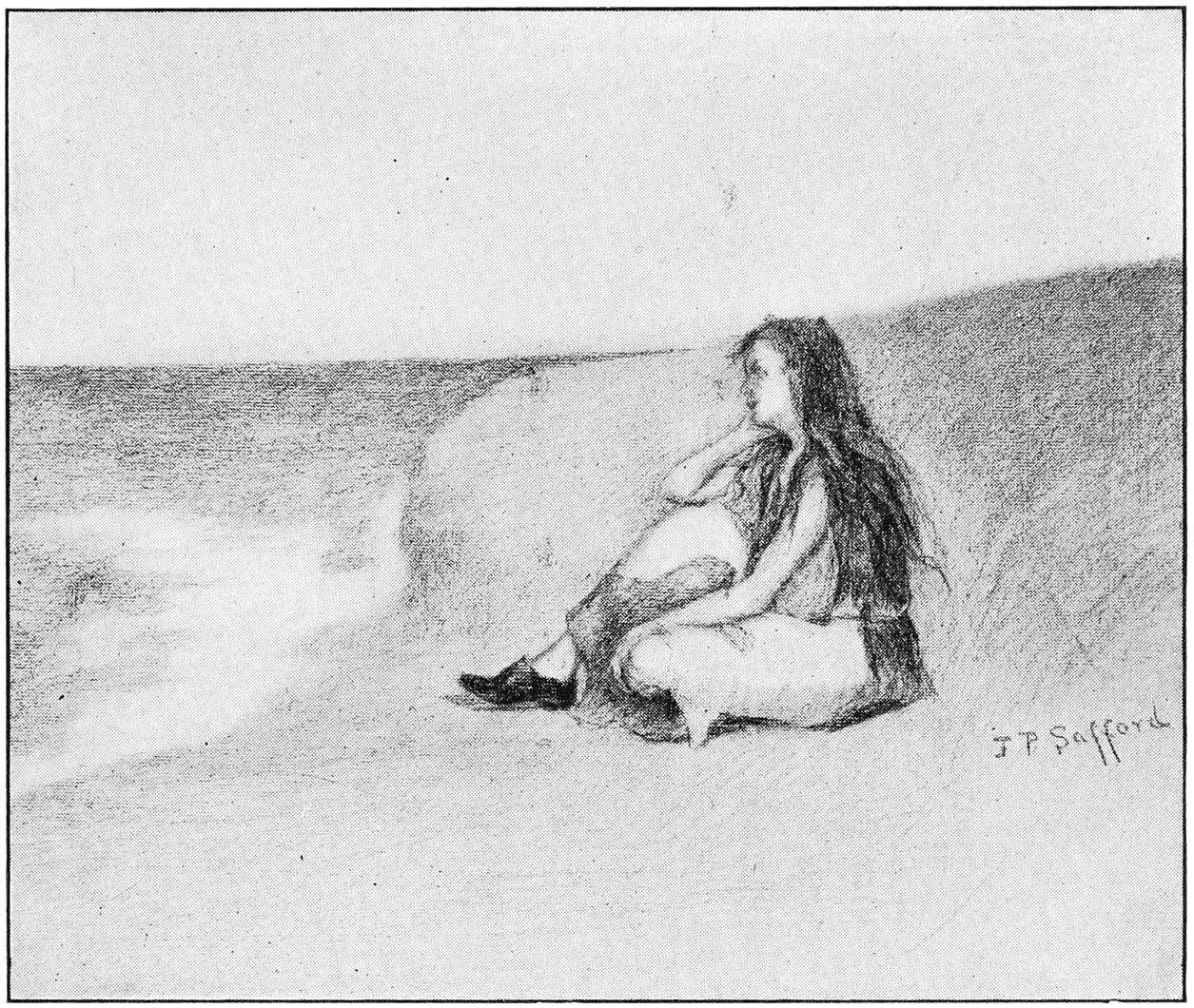

She had gradually learned where she had been found, and often went to the shore, sat

down on the sand, and gazed out over the sea to the spot where the ship which had

brought her here had sunk, and where perhaps her [309]parents were resting at the bottom of the water. Then deep sorrow overwhelmed her,

and tears filled her eyes. She felt as if she must plunge into the waves, go down

into the depths to her own kindred, and never return to her poverty and toil. She

did not long for wealth and splendor, only for a mother’s love. How wonderfully delightful

it must be to be embraced by a mother’s arms, allowed to kiss and caress her, and

know that she was her own little girl! This joy she had never known, and she envied

her foster-sisters who, in other ways, had so little for which to be envied.

When she was fourteen years old she had to begin [310]to earn something. At first she sewed jute coffee-bags, but after a few days the superintendent

herself said to her, “Rita, this labor is too coarse for you, you can do something

better,” and without consulting her foster-family she sent her to a milliner, where

Rita liked her work very much, for there she had to make, of fine straw or lace, pretty

hats for women, with velvet and silk, ribbons, flowers, and feathers, which she had

much natural taste in arranging. They tried the hats on her for customers to see,

and as everything was becoming, and the most expensive the most so, the ladies bought

them very readily. She soon received good wages, which she took home honestly to her

foster-mother, who in return treated her somewhat more kindly.

Rita was reserved and always liked to be alone. Her foster-sisters and her companions

in the workroom thought this was pride, and resented it. She was only absorbed in

her own thoughts, because her mind was constantly dwelling upon the little gold crown,

the ship at the bottom of the sea, and those who were drowned in it. On Sundays and

holidays she either stayed in a corner of the room, dreaming, or went to walk alone,

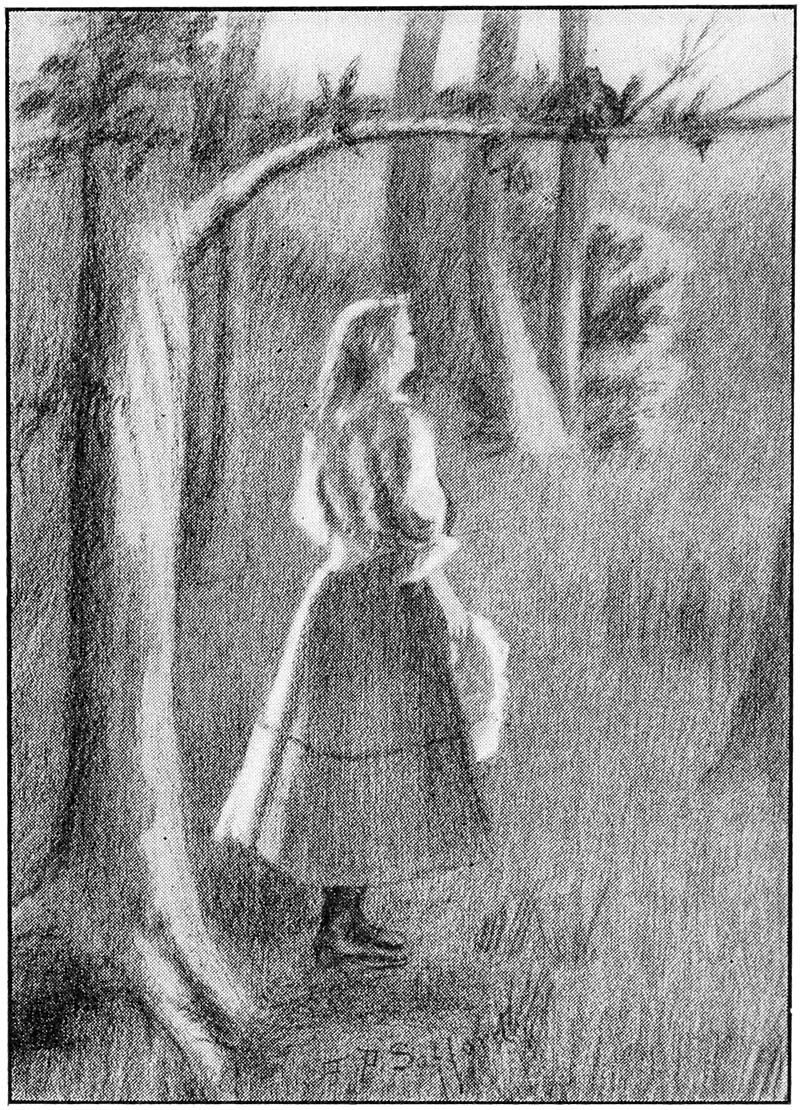

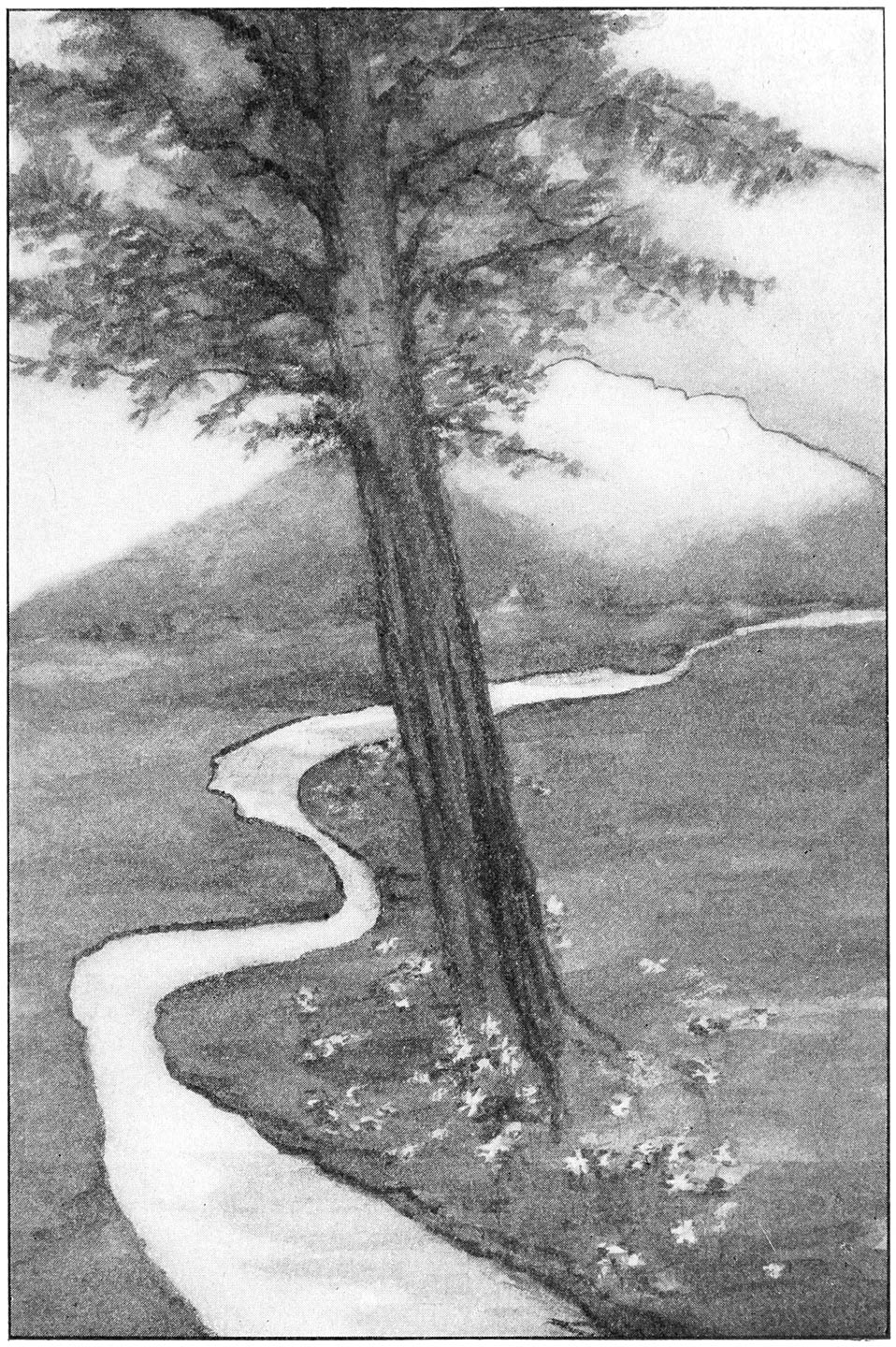

usually on the shore, but often, too, in a little wood not far from the city. The

other members of the family did not trouble themselves, but took their pleasure without

her, and this suited her exactly.

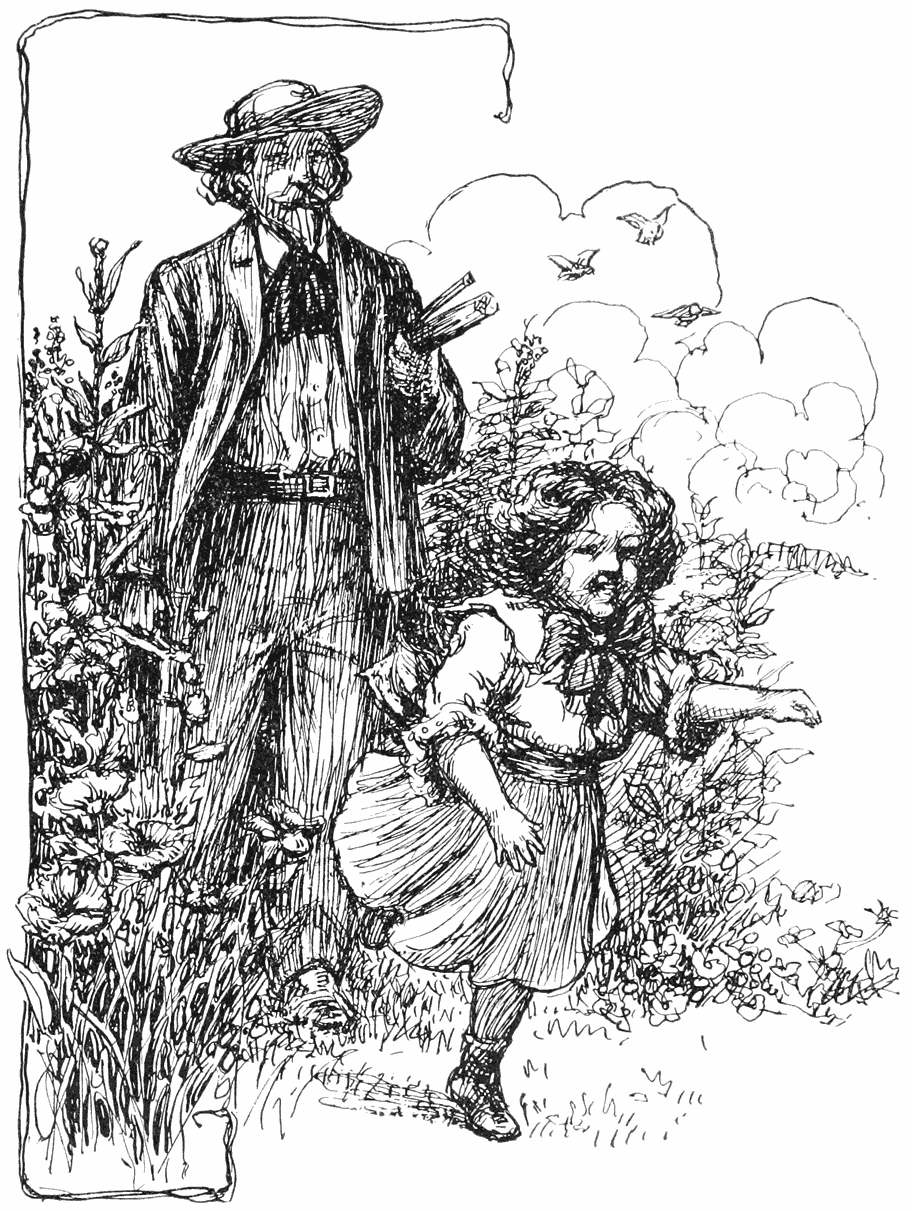

One Sunday, soon after Easter, she again went into the wood to enjoy the early spring.

A short time after [311]leaving the road and passing under the trees, she saw a squirrel playing merrily in

the top of a tree, jumping from branch to branch, peeping at her with its bright eyes,

and then leaping to the next tree. Rita followed, that she might enjoy his graceful

sport longer. The little creature sprang on before her, Rita pursued, and without

knowing it, still led by the squirrel, reached the middle of the wood, a place where

the trees grew very close together, which she had not yet seen. Suddenly she no longer

saw the squirrel, and searched everywhere for him with her eyes, unable to imagine

where he could be. While turning her head in every direction, she saw at the foot

of a large beech a hole, half hidden by moss and large ferns. Rita cautiously approached

to peep in, when the treacherous covering of plants gave way under her feet, and with

a cry she slipped down the opening. She closed her eyes and thought this would [312]be the end of her. She fell a long, long distance, till it seemed as if she was resting

on a warm bosom, and clasped by loving arms. Rita opened her eyes, and what she saw

astonished her so greatly that she thought she must be dreaming.

She was standing on the threshold of a lofty, spacious hall, more magnificent than

anything she had ever seen or believed possible. The walls were covered with white

silk tapestry, countless chandeliers filled the whole space with brilliant light,

and she did not know which to admire first: the huge mirrors, the gilded chairs with

white silk seats, the tables with mosaic tops inlaid with gems, or the throng of people

in glittering uniforms and magnificent costumes who filled the hall. Rita had no time

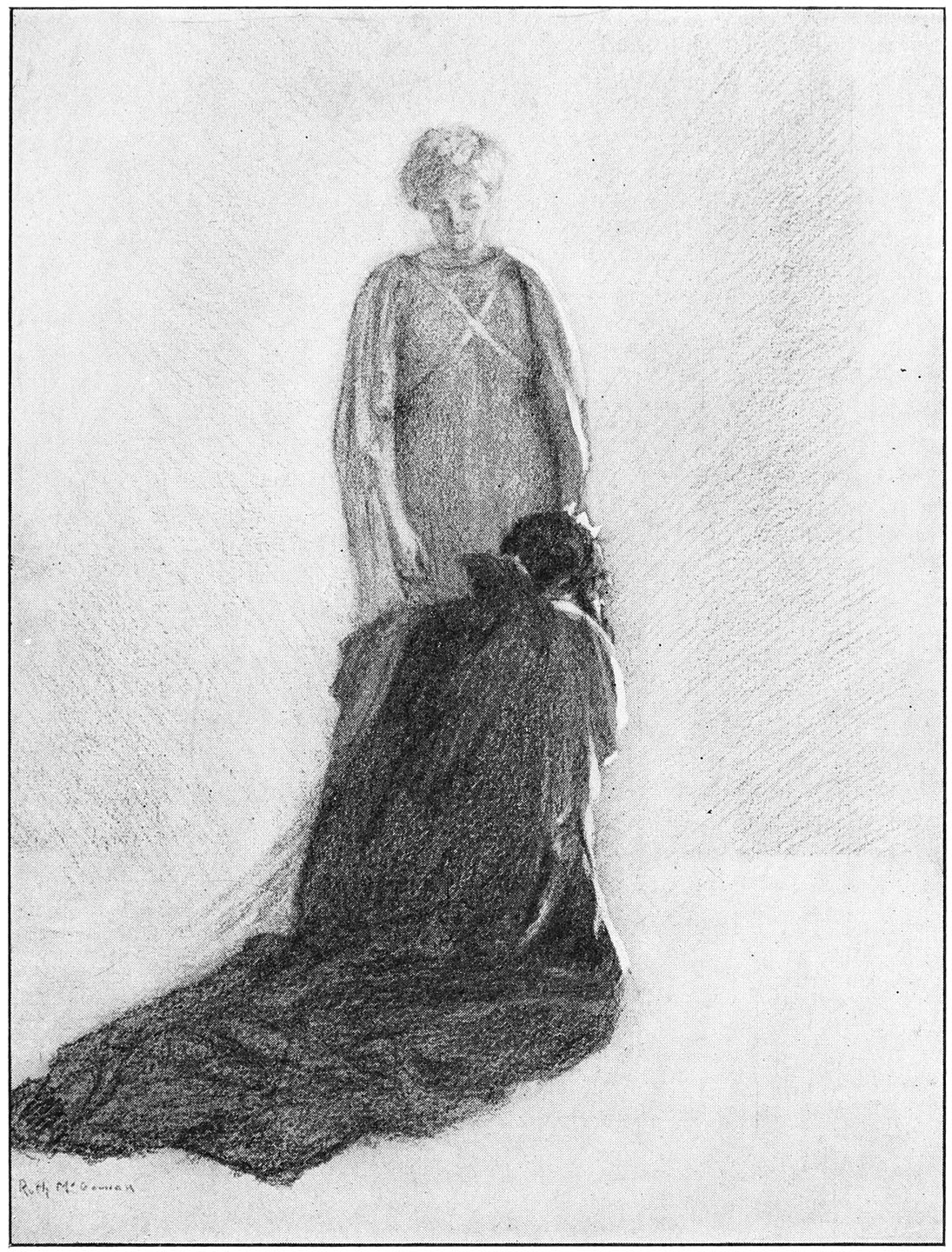

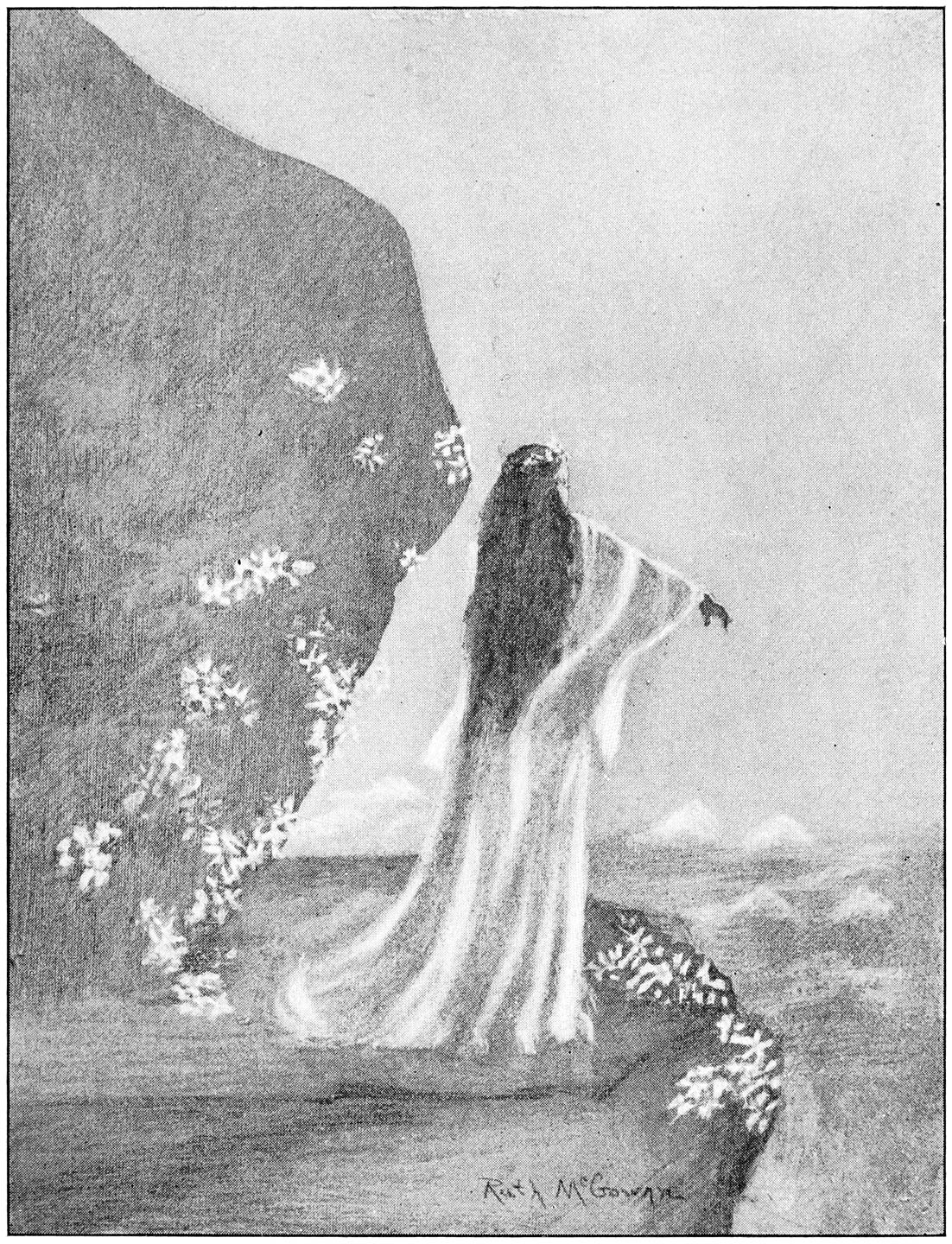

to inspect all this splendor. By her side stood a tall lady with a very proud bearing

and a wonderfully beautiful face, dressed in a white silk gown, embroidered with silver

threads, and a veil fastened with a diadem on her golden hair, which fell over her

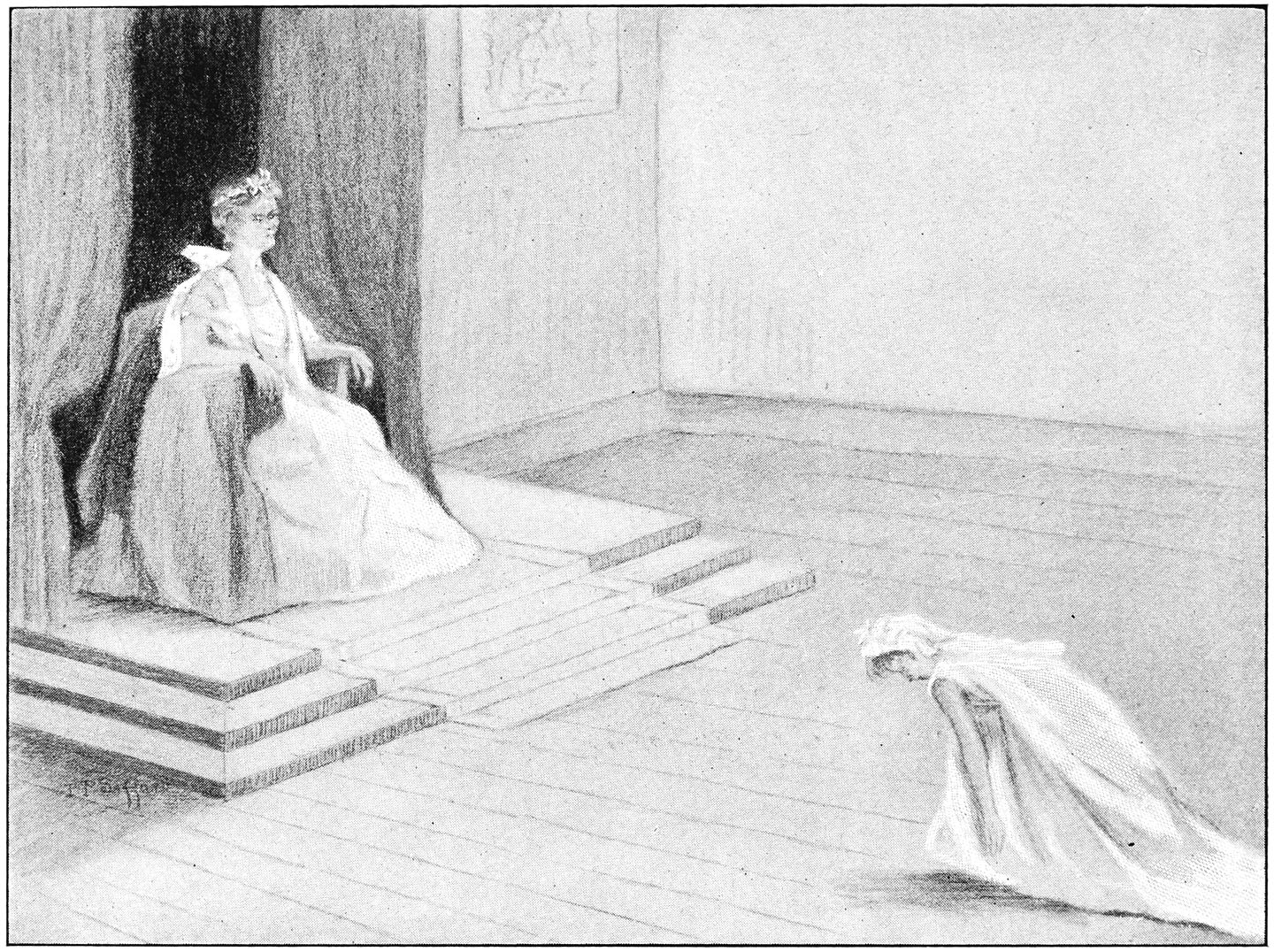

back to the edge of her skirt. This lady had caught Rita in her arms when she fell

into the depths. She bent the knee before her three times in low curtseys, bowed her

head, then rose, took Rita by the hand, and led her into the hall.

[313]

[312]

At the moment she crossed the threshold, solemn music sounded, an officer of gigantic

height uttered a command, halberds were dropped with a loud noise on the polished

floor, and between two ranks of tall soldiers of the guards in splendid uniforms,

who stood like walls, [315]Rita walked slowly with her companion through the whole length of the hall to a golden

throne at the end, which stood on a platform covered with cloth of gold beneath a

purple canopy. The white-robed lady, by a wave of her hand, invited Rita to ascend

the three steps of the platform and seat herself upon the throne. When the young girl

had taken her place, the music ceased, the lady lifted from a small table, which stood

beside the throne, a silk dress, embroidered with silver, which she put on Rita, a

blue velvet mantle, lined with ermine, which she threw over her shoulders, and a crown

of gold and diamonds the size of a pigeon’s egg, which she set on her head. Then,

again bending the knee before her, she said in a voice which sounded like a silver

bell, “Welcome to your kingdom, royal mistress.”

She moved aside, and now ladies in rich court dresses, with long trains and brilliant

jewels, and gentlemen in uniforms covered with gold lace, wearing swords by their

sides and orders on their breasts, approached and paid homage to Rita. The ladies

kissed her hand, the gentlemen pressed their lips to the edge of her ermine mantle.

About a hundred or more ladies and gentlemen greeted Rita in this submissive manner.

For a long time Rita did not dare to open her lips. At last, when the courtiers had

paid their homage, she turned to the white-robed lady standing beside the throne and

asked timidly: “Where am I? What does all this mean?”

[316]

“You are in your kingdom, royal mistress,” replied the lady, “and your loyal subjects

are happy to be permitted to offer you their homage.”

“I don’t understand,” answered Rita, bewildered; “you are mistaken. I am only a poor

milliner—”

“Not so, royal mistress,” said the lady; “whatever you may be considered in a foreign

country does not matter. Here you are our illustrious young empress, and at heart

you know it perfectly well, and have always known it.”

“Then the little gold crown on my shirt—”

“Is the sign of your rank, royal mistress.”

“But explain to me—what does it all mean—who are you?”

The lady made a sign, the guards with clanking steps drew back to the walls of the

hall, the courtiers formed a wide semicircle around the room, the ladies in the front

row, the gentlemen behind them, and in the midst of a deep silence she began:—

“Royal mistress, I am the White Lady, the attendant fairy of your illustrious family,

whose duty it is to watch over all who are of your royal blood. Do not believe that

I have neglected this duty. But foes who are more powerful than I have prevented me

from performing it as I ought and wished to do. Know that you are the daughter of

the emperor and empress of Thule, and their lawful heiress. Here are the portraits

of your noble parents. They welcome from their frames their lovely descendant.”

[317]

The White Lady pointed with outstretched hand to the wall behind the throne. Rita

turned eagerly and saw at the right and left of the purple canopy the life-size portraits

of a handsome man in crown and imperial mantle, and a woman who looked like a being

from the heavenly world. At the sight she began to weep bitterly, and the whole court

sobbed with her. The White Lady waited until she was calm again and then went on:—

“For ten long years your father had reigned gloriously in Thule, like his father,

his grandfather, and thirty-three ancestors before them for a thousand years. Then

one day the King of the Pole, without any cause, declared war against him and with

his army of ugly dwarfs invaded Thule. The Pole King is a great magician, who reigns

over the polar bears and the whales, and when he chooses can produce such cold that

the air freezes and sends thunderbolts from the northern lights, which kill every

living creature. Our regiments could not withstand his thunderbolts and polar bears,

our ships could not resist his cold and his whales. He conquered Thule, and your parents

could do nothing except fly with you, royal mistress, and their court on their last

ship. But even on the sea the wicked wizard pursued them, he conjured up a terrible

storm which struck them here, drove their ship on the shore, and wrecked it. The waves

swallowed all on board, I was permitted by the higher [318]powers to save only you, royal mistress. This is the sorrowful history of your illustrious

family.”

She was silent, and Rita, too, remained silent a long time, for she was much excited

by all she heard and saw. After some time she calmed herself and asked: “What is to

be done now? Will you not take me back to my kingdom of Thule?”

“Alas!” replied the White Lady, “that is not possible. Between here and your kingdom

lie three seas and four broad countries, with soldiers and fortresses on their frontiers,

besides five ice mountains, six burning deserts, and seven raging rivers. And even

if we crossed all these obstacles on the way to Thule, we should find there the King

of the Pole, who would do you some harm.”

“Then must I stay here always?” asked Rita, anxiously.

The White Lady sighed, and the whole court did the same.

Rita did not know what time it was, but she must have been a long while in the throne

room, for she began to feel hungry. At first she was ashamed to ask for anything;

but when the gnawing in her stomach grew greater, she thought, “I am empress, and

have a right to command.” So she said: “Dear fairy, could not I have something to

eat? I am very hungry.”

“Royal mistress,” replied the White Lady, sadly, “we have nothing here.”

[319]

“Not even a bit of bread?”

“Not even a bit of bread. Your courtiers and your guard need no food, nor your attendant

fairy either.”

“Then I must starve to death if I stay here.”

The White Lady lowered her eyes, as if ashamed, and remained silent.

“If this is so,” said Rita, sadly, “I suppose I must leave you.”

As she received no answer, she rose from the throne and slowly descended the steps

of the platform. As her foot touched the polished floor, trumpets blared, shouts of

command were heard, the guard marched from the sides of the hall to the centre, dropped

their halberds with a thundering sound, and formed two motionless ranks, the music

again struck up the solemn imperial march, the White Lady clasped Rita by the hand,

court-marshals with white wands walked before them, court ladies with long trains

followed, and thus the magnificent procession moved toward the entrance. Here all

paused as if spellbound; the White Lady let Rita’s hand fall and made three low curtseys

before her.

“Will you all take leave of me?” asked Rita, anxiously.

“We must,” replied the White Lady.

“What! Will no one go with me? Must I return to my foster-parents all alone?”

“Unfortunately we cannot change things,” answered the White Lady, sorrowfully.

[320]

Rita sighed heavily, embraced the White Lady, who kissed her hair again and again,

while the ladies and gentlemen of the court, kneeling around her, pressed their lips

to the border of her mantle, and said, “Then farewell to you all.” Tears streamed

from her eyes, and she was preparing to pass through the door, which two court-marshals

held open before her. At that moment the White Lady said gently, “Pardon me, your

Majesty,” and lifted the diamond crown from her head. Rita stopped in astonishment,

when she also unfastened the clasp of the ermine-lined blue velvet mantle and removed

it from her shoulders.

“You will not even leave me the signs of my rank?” cried Rita.

“It is the order, and we must obey,” replied the White Lady, removing also the wonderful

gown of white silk and silver, so that Rita again stood in the plain Sunday clothes

of a poor milliner.

“So the magnificence is all at an end,” lamented Rita. “I am no longer an empress,

but the foundling, Margarita Bölgebarn.”

“Not so, your Majesty,” answered the White Lady, quickly. “Empress you are, and empress

you will remain; no one can rob you of your royal rank. True, you will live among

the people of this country unrecognized; but whenever you choose to come here among

your faithful subjects, all the honors due your rank will be shown you, and your own

eyes will convince [321]you that you are our beloved and revered sovereign.”

Rita still lingered at the door. It seemed to her very hard to leave the brilliantly

lighted hall; but she had no choice. Unless she wanted to starve, she must go. So,

summoning all her resolution, she crossed the threshold. At the same moment an invisible

power seized her like a whirlwind and bore her up with the speed of an arrow. A moment

later she was standing under the sunset sky at the edge of the hole at the foot of

the great beech tree, and saw on one of its lowest branches the squirrel, which again

hopped merrily from tree to tree before her, and led her out of the wood.

It was already dark when she reached home. Though usually they did not trouble themselves

much about her, this time they had been anxious, and her foster-mother asked her harshly

where she had been roving about so long. Rita excused her absence with gentle words.

She thought of her royal rank, and could not help secretly smiling at the poor woman,

who, in her ignorance, treated her so rudely. She remembered her throne room, her

courtiers, her body-guard, her diamond crown, and found it amusing that she was obliged

to sit in a poor workman’s room at a table without a cloth, to a scanty meal of cold

sauer-kraut, with peas, black bread, and water, and then go to rest on a straw bed,

which she now had for herself, since she richly earned it.

[322]

After the secret of her birth and rank had been revealed to her, a change took place

in her which even the dull people who surrounded her could not fail to notice. She

was even more quiet and reserved than before, yet kind and cordial to every one in

a way that her foster-family had never seen among the people of her class. At first

her unvarying graciousness vexed her uneducated companions; for they considered it

affectation, and answered Rita’s pleasant words scornfully or roughly. But as this

did not disturb her, and her manner remained equally gentle and kind, the others were

gradually impressed by it and began to regard her with a certain shyness. In the milliner-shop,

too, the workwomen and customers noticed Rita’s dignified manner, and the ladies often

said to the proprietor, half in jest and half in earnest, that there was something

so queenly about the young lady who tried on the bonnets that they scarcely dared

to ask her to wait on them.

Rita no longer, in her leisure hours, went down to the shore where the workmen had

found her when she was a little girl, but into the wood to the old beech tree. Sitting

on the edge of the hole hidden by the moss and ferns, she shut her eyes and let herself

slip down. She knew now that two soft arms would carefully catch her. The solemn imperial

march always sounded at her appearance, and her courtiers welcomed her with joy. She

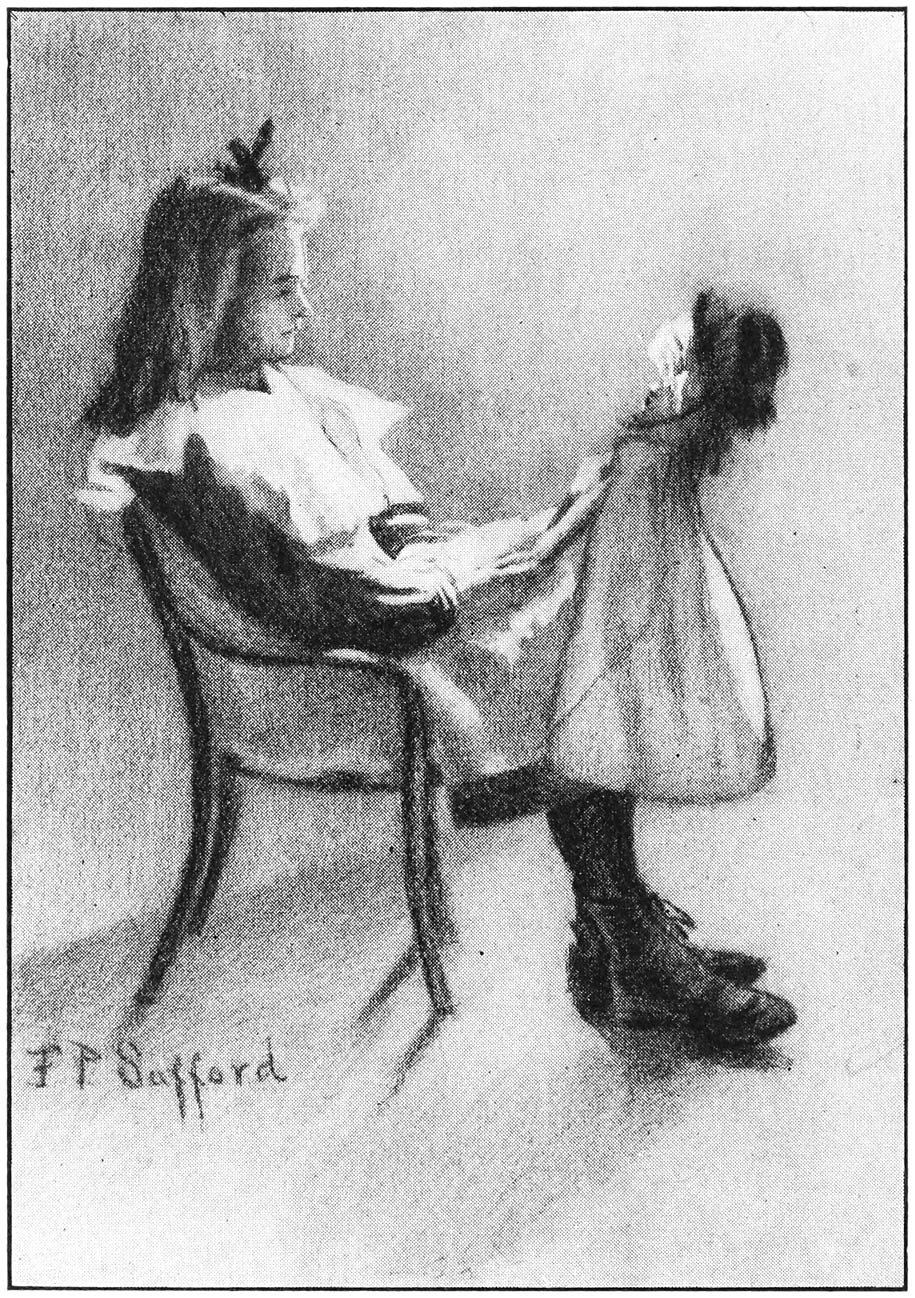

sat in her magnificent robes, with her diamond [323]crown upon her head, an hour or two on her golden throne among her subjects, while

the White Lady told her a thousand things she longed to know: first about her parents,

especially her mother, who had been a princess of Swan Land, then of her ancestors,

of her country of Thule, its people, manners, and customs. The court ladies sang to

her old songs of the greatness of her race, their wisdom in peace and heroic courage

in war. Learned chamberlains repeated to her the history of Thule; she was shown dolls

in the costume of the people, and pictures of her ancestors’ palace, their castles,

cities, and the most beautiful landscapes in her kingdom, till at last she knew everything

about Thule as thoroughly as if she had always lived there and knew nothing else.

It no longer seemed to her hard to leave her throne and return to the city as a poor

milliner. In spirit she always lived in her empire, on Sundays and holidays she was

an acknowledged empress amid the splendor of her court, and she bore with a patient

smile the life she led during the week, when, plainly clad and unnoticed, she lived

among the common people as if she were one of themselves.

Her foster-family gradually remarked that she left them on Sundays directly after

dinner, and did not return until the evening, with a reflection of secret joy upon

her face like one who has been happy several hours. Her foster-sisters put their heads

together and whispered, making all sorts of guesses, which did little [324]honor to Rita. They wanted to find out the secret of her lonely walks, and her foster-brother

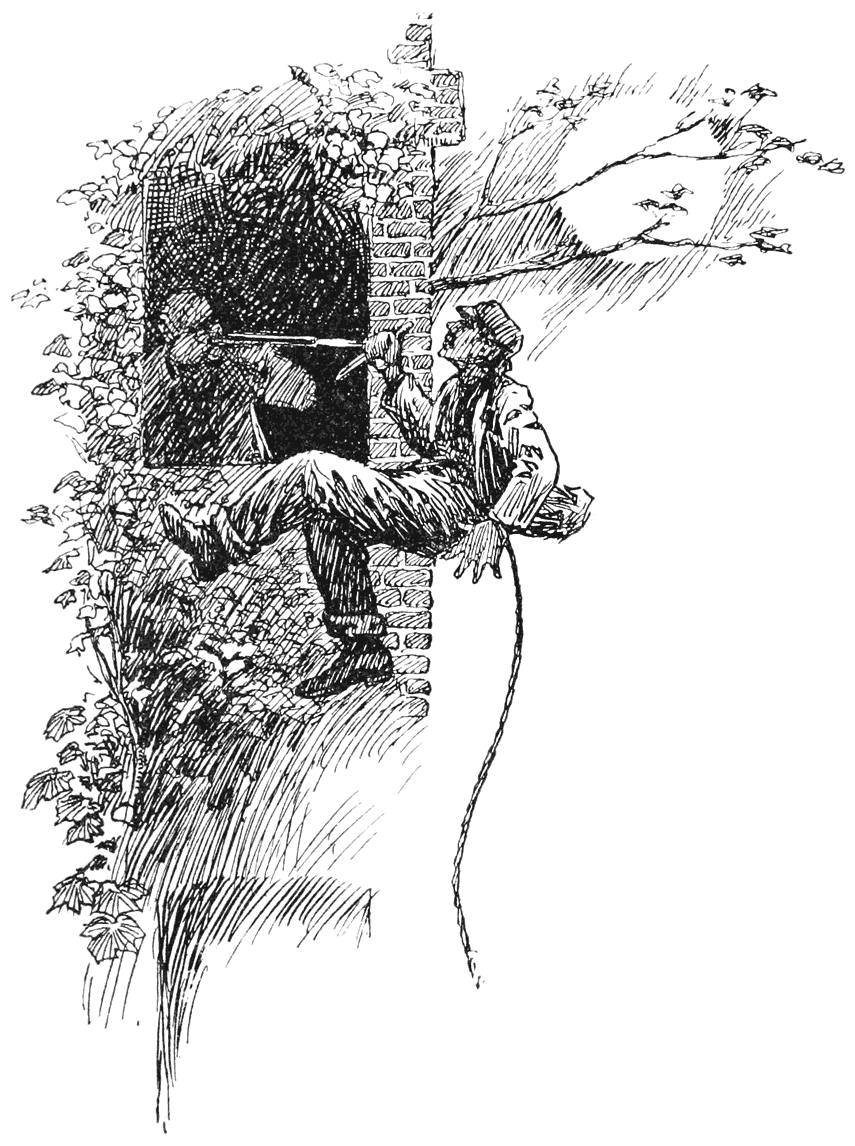

undertook to follow her unseen. He did follow at some distance into the forest as

far as the hole at the foot of the old beech. He did not see the squirrel that sprang

before her from bough to bough, for his eyes were fixed upon Rita. Suddenly she vanished,

and when he came to the place where he had lost her, he discovered the hole under

the moss and ferns. He did not doubt that she had slipped down this hole, but at first

he did not think it advisable to go after her. So he sat down on the moss and waited.

When, however, an hour, then two hours passed, without any sign of life, he plucked

up courage and began to climb down the dark opening. But the sides were very steep,

the clumps of grass and moss to which he clung tore away, and amid a hail of clods

of earth and stones he fell into the depths.

Soiled with dirt, his whole body covered with bruises and bumps, and his clothes torn,

he struck against the door, which flew open at the shock, and rolled into the middle

of the throne room. The commander of the body-guard rushed up to him and ordered his

soldiers to seize the intruder. But Rita, who recognized the fellow, called loudly,

“Halt!”

The marshal of the court explained that he had forfeited his life, but Rita repeated:

“Not a hair of his head shall be harmed! Obey your empress!” Then she said to her

foster-brother, who was rubbing his [325]aching limbs and staring stupidly around him: “It was very impertinent to follow me.

This time I will forgive you. But don’t do it again; my guards would not let you go

a second time.” She motioned to the White Lady, who gave an order to the officer of

the guard. The soldiers seized the youth, flung him out of the throne room, and left

him lying outside of the door. He began with great difficulty to climb up, but the

steep walls of earth gave his hands and feet no support, and he always slid down again.

At last the White Lady took pity on him, and when he made another attempt to climb,

she raised her whirlwind, which seized him and bore him up into the woods.

The youth limped along groaning, lost his way several times, and did not reach the

direct road to the city until twilight was closing in. When he reached home, Rita

had been there a long time. She had told nothing about the adventure, and was somewhat

anxious to hear what he would say of it to the family. When he saw her, he only grinned

and said nothing. Was he unwilling to tell the story in her presence? But his mother

noticed his soiled and torn clothes and the bloody scratches on his hands, and cried

out: “Boy! How you look! What has happened? Have you been fighting?”

“No,” replied the youth, sulkily, “it’s only our dear Rita and her queer taste that

are to blame. I wanted to see where she is always running. Now I know. [326]She goes into the woods and jumps down into a deep hole. This leads into a large cave.

I leaped after her, but she seems to be more skilful than I am. I fared badly. I almost

broke my limbs. The cave appears to get some light through a chink in the rocks on

the top. But it is dark, cold, and damp. Rita walks up and down, talking to herself.

I think she is playing some kind of a farce, in which she is a princess or empress,

and wants no listeners, for they would laugh at her. Don’t worry, Rita, I won’t disturb

you again in your fool tricks.”

“That will be better,” replied Rita, smiling and gentle as ever. So her foster-brother

had seen nothing—neither the magnificent hall nor the courtiers, neither her imperial

robes nor the throne. This surprised her, it is true, but she was glad. It was better

that she should remain unrecognized, since she must earn her living as a poor milliner.

Behind her back, her foster-brother told the others that Rita was evidently a little

crazy, for he had heard her say plainly, in her cave, that she was an empress, had

guards, and similar silly nonsense. The foster-mother replied that it came from the

little gold crown embroidered on her shirt, but as her craziness did not seem dangerous,

they all thought it would do no one any harm if she was allowed to go on with her

folly, and they closed their eyes to her queer fancies.

So Rita lived for several years, during the week a [327]poor workingwoman, on Sundays a great empress, and it did not trouble her at all that

she alone knew her secret. She was just twenty-one years old when one day it happened

that a handsome young man, whom she had often met on her way from the house to her

shop, but without noticing him, came up to her in the street, raised his hat, and

said, “Miss Rita, will you allow me to say a few words to you?”

Rita blushed and answered more sternly than was her custom: “I don’t know you. Leave

me alone,” and continued her way. The young man stood still, looking after her sorrowfully.

She could not help thinking of him all the morning, and though it vexed her that he

should have spoken to her in the street, she would have liked to know what he wanted

to say to her.

When she went home at noon, she saw, to her astonishment, the young man sitting in

her house with her foster-mother. She stood hesitating on the threshold, and the workman’s

wife called to her, while the young man respectfully rose from his chair: “Come in,

the gentleman won’t eat you. He means fairly.”

The young man now spoke. “Miss Rita,” he said, “I have known you for many months.

I have followed you daily, without your noticing it. I ventured to speak to you in

the street, because I thought that would be the easiest way. But you did perfectly

right to reprove me, for it was not proper. I ought to [328]have done first what I did not think of until later; that is, introduce myself to

your parents.”

“But what do you want?” asked Rita, bewildered.

“Miss Rita,” replied the young man, “I love you, and would like to marry you. Will

you give me your hand?”

Rita’s heart beat faster, and she lowered her eyes in confusion. “That cannot be done

so quickly,” she said, “I do not know you at all—”

“Don’t refuse,” interrupted her foster-mother; “the gentleman is a fine man and a

poet.”

“You are a poet?” cried Rita, wonderingly.

“At least I think so,” answered the young man, modestly. “I write poems and have them

printed. People buy them, and tell me that life seems easier and the world more beautiful

to them when they have read them.”

As Rita grew thoughtful and made no reply, he drew a little book from the pocket of

his overcoat and gave it to her, adding: “Please accept this from me, Miss Rita. It

contains my verses. Let them speak for me, and permit me to come to-morrow for your

answer.”

When with a courteous bow he left the room, the foster-mother told Rita that she ought

to accept this handsome and elegant young man; it was a piece of good luck for her,

and she would never find anything better. Rita said she must have time to think over

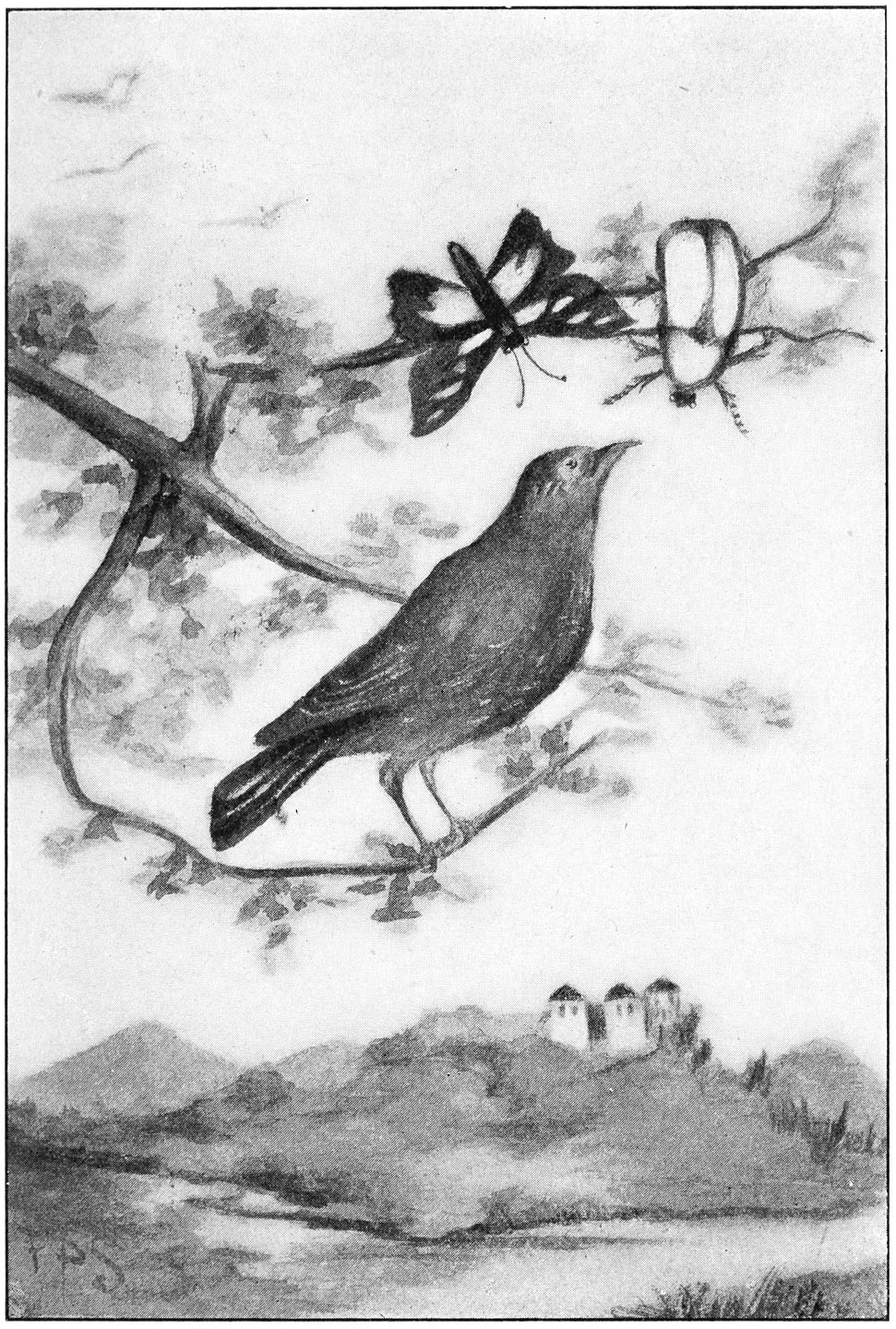

so important a matter, and retiring into a corner began to read the poems. They sang

of spring and sunshine, [329]of blossoming flowers and nightingales, of human beings who loved each other and would

remain faithful in joy and sorrow, of all great and noble things which make the happiness

of good people. And as Rita read on, she fancied she heard the old songs of her court

singers, and the wise words of her White Lady, and her eyes grew dim till at last

she could no longer see the letters plainly.

She thought of the poet all day, and at night she could not sleep. When the next noon

he came for his answer, the others went out to leave the two alone, and Rita said:

“I have read your poems, and I like them very much. You are really a poet. But do

you know who I am?”

“You are the sweetest, most beautiful girl my eyes ever beheld,” he answered warmly,

“and if you would become my wife, I should be the happiest man on earth, and would

never cease to sing and utter my joy in verse.”

“I am a foundling, and no one knows who my parents were.”

“Your parents were what they were, and you are what you are.”

“I am a poor workingwoman, and shall bring you nothing except what I have on my back.”

“You are yourself a treasure, which no gold in the world can outweigh. We will work

and shall not lack the necessaries of life.”

[330]

“Give me a little more time to think,” she said gently. “So important a resolve cannot

be made in an instant.”

“That is true,” replied the poet; “but meanwhile may I at least see you daily?”

“Yes, you may,” said Rita. Then he kissed her hand and gave her a sheet of paper on

which, since the day before, he had written new poems for her, more beautiful than

any of the first ones.

Contradictory feelings were struggling in Rita’s soul. She liked the poet, and it

seemed to her a happy lot to become his wife. But she thought she ought not to promise

him her hand without asking the advice of the White Lady, her only friend in the wide

world, and without telling him her secret. She was so impatient that she could not

wait for Sunday, but went at once to her wood, without even stopping at the shop to

ask permission for an afternoon’s absence. She was in such a hurry that she did not

look around once on the way. So she did not see that the poet, as had been his habit

for months, had come after dinner into the neighborhood of her house to follow her

to the shop and enjoy all the way the sight of her lovely figure. He saw with astonishment

that she did not go toward the shop, and that she was walking much faster than usual,

so he hastily pursued to find out what she meant to do. Thus he tracked her into the

wood, to the old beech tree and the hole half hidden by moss and ferns, where she

vanished from his eyes. When he saw her suddenly [331]disappear down the hole, his only thought was that she had met with an accident, and

with a cry of terror he ran forward and without hesitation leaped after her. He fell

on his feet at the bottom, without doing himself any harm, and saw before him, in

the dim light, tall gilded folding doors, from beyond which he heard the clank of

arms and solemn music. He resolutely pushed open the door and found himself in the

throne room, just at the moment that Rita had taken her seat upon the throne, and

the White Lady was clothing and crowning her as an empress. When he saw this, he rushed

through the ranks of the guards to the steps of the throne, knelt, and touched his

forehead to the floor.

Rita had been unable to keep back a low cry of surprise when she saw the poet. This

time, too, the guards seized him, but Rita waved her hand and commanded them to release

him. Descending the steps, she raised the poet. He did not dare to look at her, and

only murmured: “I always suspected it. You are of royal birth. Graciously forgive

my presumption in having dared to love you.”

“So you see my throne and my crown, my hall and my courtiers?” asked Rita.

The poet looked at her in astonishment, and replied: “Why shouldn’t I? The splendor

dazzles me, it is true, but it does not wholly blind me.”

Rita, turning to the White Lady, said: “He is a [332]poet, and he wants to marry me. What do you advise me to do?”

“Your Majesty,” replied the faithful fairy, “he is of a good race. He has the eagle

eyes, which see secret things. He is an aristocrat, for he is a poet. If you love

him as he does you, marry him.”

Rita blushed deeply and cast down her eyes, the White Lady took her hand and laid

it in the poet’s, the courtiers burst into loud cheers, the music struck up a joyous

march, and the portraits of the emperor and empress of Thule, on both sides of the

throne, began to shine wonderfully. The court-marshal bent the knee before the poet

and said, “Your Highness, by your engagement to our illustrious imperial mistress,

you become Prince Consort, and have a right to the highest honors.” He gave a low

order to a page, and instantly several court lackeys appeared with purple velvet cushions,

on which lay a gold embroidered uniform, the ribbon of an order, a sword, and gold

spurs, and placed them all on the floor at the foot of the throne. Rita asked, smiling,

“Will you put these on?”

“I dare not—the honor is too great—not to-day,” answered the poet in bewilderment.

Then in a lower tone he added, “Your Majesty—beloved Rita—since you are willing to

give me the greatest happiness—since I am your betrothed husband—I will venture to

make one request—”

“What is it?” asked Rita, kindly.

[333]

“Send your courtiers away—let us be a moment alone—that I may embrace you for the

first time as my bride.”

“There is no solitude for an empress,” said Rita; “let us go.”

Rising, she walked, leaning on her future husband’s arm, amid the usual honors, to

the door, left her imperial robes in the hands of the White Lady, and a moment later,

with the poet, was at the entrance of the hole. Here, under the rustling branches

of the old beech, seen only by the faithful squirrel, Rita was clasped in her lover’s

arms and exchanged the first kiss.

The poet was dazed by all he had seen and experienced, but he did not venture to question

his bride. Rita guessed what was passing in his mind, and on their way home told him

all. Only she begged him to keep it secret, for if he repeated the story, people would

merely laugh at them.

The betrothal was celebrated at the foster-parents’, and the wedding soon followed,

with two celebrations,—one in the secret empire, and one among ordinary mortals. Rita

left her work place and opened a milliner’s shop herself, and the poet, in his happiness,

wrote the most beautiful poems and became very famous. During the first year of their

marriage, they often went to the wood, and the young husband found great pleasure

in sitting in his princely robes upon the golden throne, beside his imperial consort.

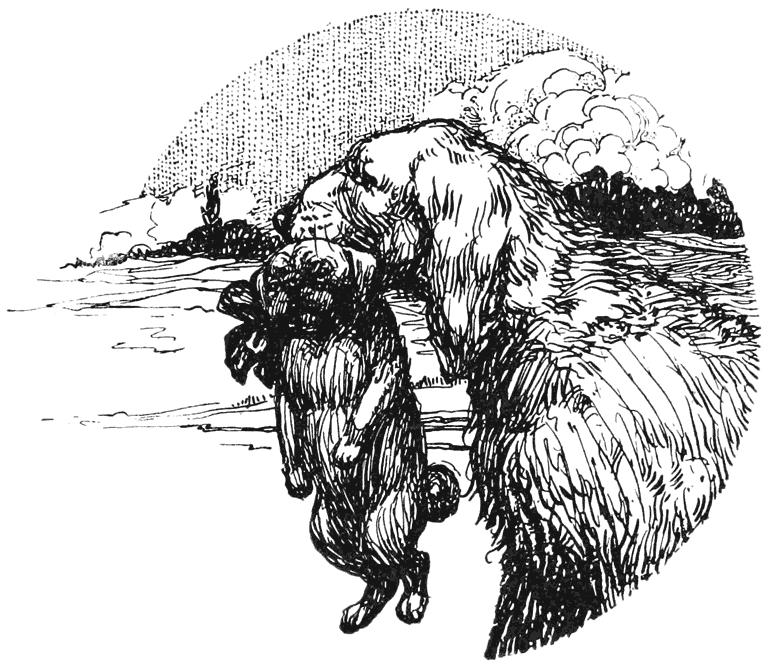

But at the end of a year [334]the stork brought a little child, and for some time Rita could not go out, and her

poet did not know whether he could appear at court alone. After a month Rita went

to the wood again for the first time, taking with her her baby, on which she had put

the little shirt with the gold crown, which her foster-father had given to her on

her wedding day, and descended to the secret empire to present her child to the courtiers.

There was great rejoicing and paying of homage, and the White Lady took the little

one in her arms, caressed it, and whispered ardent wishes for its happiness. When

her faithful subjects had grow calm again, Rita addressed them in a very grave tone:

“Noble lords and ladies,” she said, “we shall see each other to-day for the last time.

My work, my child, my husband, claim all my hours, and I no longer have any half-days

of leisure to spend in your midst. Your loyalty touches me, but unfortunately it is

of no use. Return to Thule, make your peace with the King of the Pole, and remember

me faithfully, as I shall always remember you. And now, farewell.”

The ladies and gentlemen fell upon their knees. All were sobbing. Tears rolled down

the cheeks of even the old guards. The White Lady, weeping softly, clasped Rita in

her arms and would not let her go. She gently released herself, took up her little

child again, gave her hand kindly to all, and slowly approached the door. Here she

cast one last look at the court, the hall, her crown, and her royal robes, kissed

the White Lady [335]for the last time, and in an instant was in the upper world.

At the foot of the old beech, Rita said sadly to her husband: “The sacrifice is made.

The imperial splendor is over forever.”

“No,” replied the poet, bending the knee before her. “To me you are and always will

be the empress, as I felt and recognized you before you had revealed yourself to me

in your magnificence, and so you always will be to your children also, now and forever.”

And so it was. Wreaths were afterward bestowed on the poet, which he laid at the feet

of his wife. They became prosperous and distinguished, had numerous children, reared

them to be excellent men and women, whom they taught that they must be better and

more competent than ordinary people; and though no one of them became an emperor or

an empress, they were all such estimable citizens, that, after many, many years, when

Rita was dead, the grateful city placed a monument on the spot upon the shore where

little Margarita Bölgebarn had been found.

[337]