Title: Great commanders of modern times and The campaign of 1815.

Author: William O'Connor Morris

Release date: November 19, 2025 [eBook #77267]

Language: English

Original publication: London: W.H. Allen & Co Ltd, 1891

Credits: Brian Coe, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

AND

THE CAMPAIGN OF 1815.

BY

WILLIAM O’CONNOR MORRIS.

Reprinted from the

“Illustrated Naval and Military Magazine.”

“Faites la guerre offensive comme Alexandre, Annibal, César, Gustave Adolphe, Turenne, le Prince Eugène et Fredéric; lisez, relisez l’histoire de leurs quatre vingt trois campagnes; modelez vous sur eux.”—Napoleon.

LONDON: W. H. ALLEN AND CO., LIMITED,

AND AT CALCUTTA.

1891.

(All Rights Reserved.)

LONDON:

PRINTED BY W. H. ALLEN AND CO., LIMITED,

13, WATERLOO PLACE.

| GREAT COMMANDERS OF MODERN TIMES. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PAGE | |||

| PREFACE | v | ||

| INTRODUCTION | 1 | ||

| CHAPTER | I.— | Turenne | 12 |

| „ | II.— | Marlborough | 36 |

| „ | III.— | Frederick the Great | 68 |

| „ | IV.— | Napoleon | 102 |

| „ | V.— | „ (continued) | 125 |

| „ | VI.— | „ (continued) | 157 |

| „ | VII.— | „ (continued) | 186 |

| „ | VIII.— | „ (continued) | 214 |

| „ | IX.— | Wellington | 238 |

| „ | X.— | Moltke | 274 |

| THE CAMPAIGN OF 1815. | |||

| CHAPTER | I. | 315 | |

| „ | II. | 335 | |

MAPS, PLANS, AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Frederick the Great | Frontispiece | |

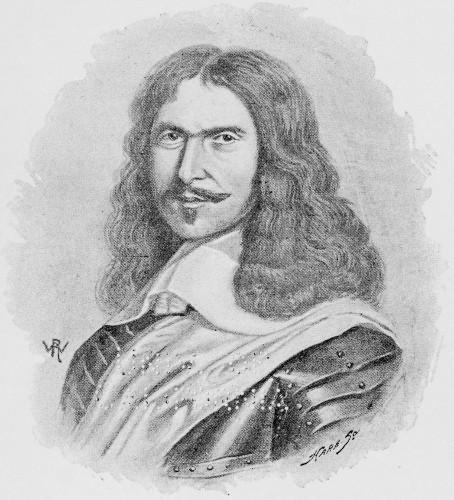

| Turenne | To face page | 12 |

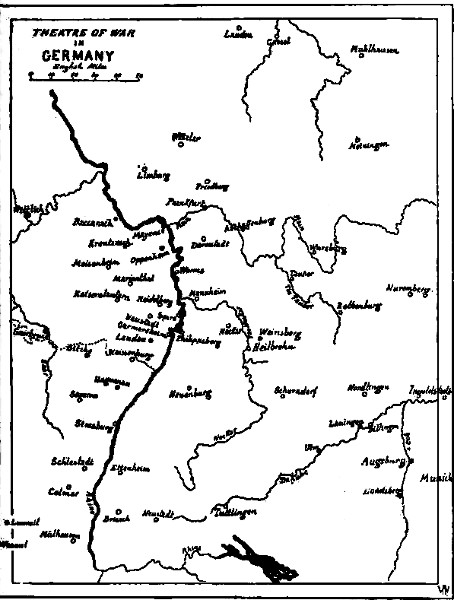

| Theatre of War in Germany | „ | 20 |

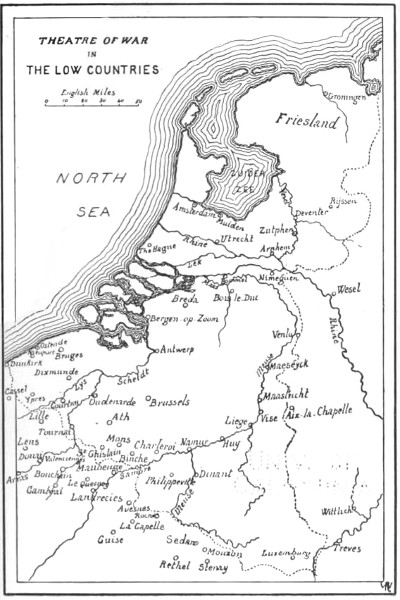

| Theatre of War in the Low Countries | „ | 28 |

| Marlborough | „ | 36 |

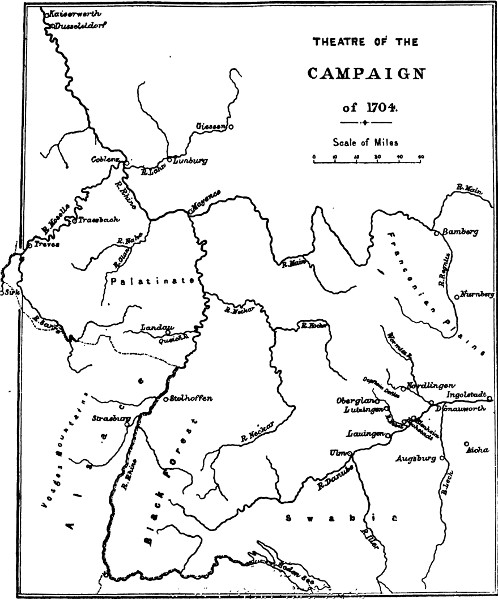

| Theatre of the Campaign of 1704 | „ | 44 |

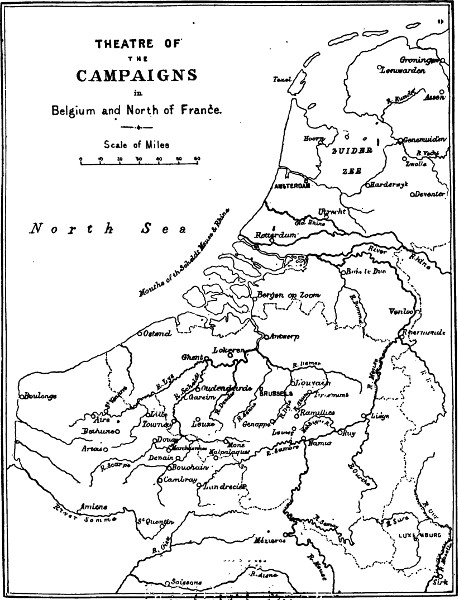

| Theatre of Campaigns in Belgium and the North of France | „ | 54 |

| Theatre of the Seven Years’ War | „ | 76 |

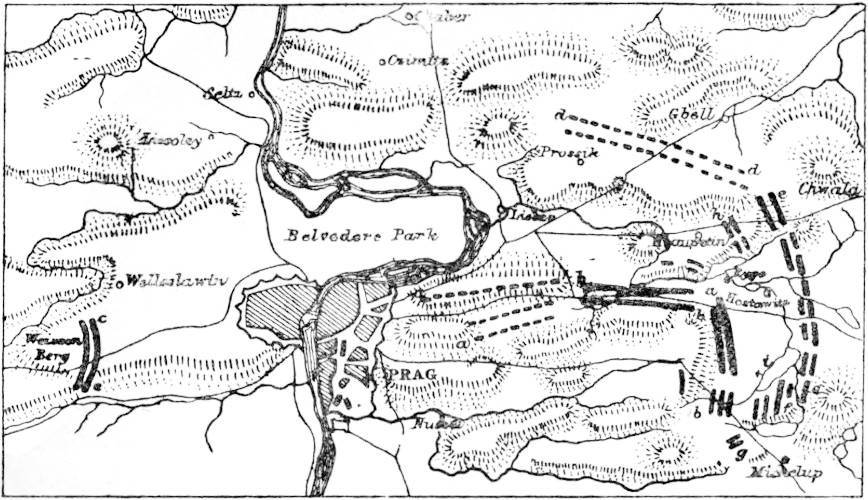

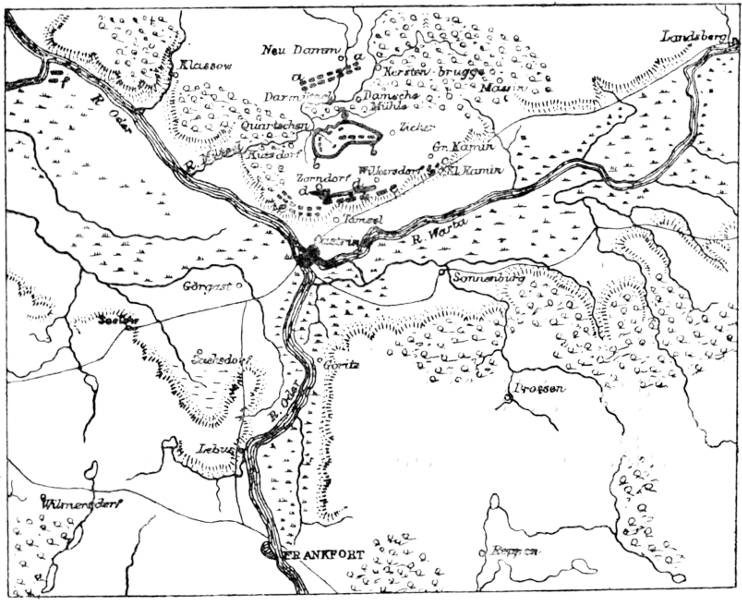

| Battles of Prague and Zorndorf | „ | 78 |

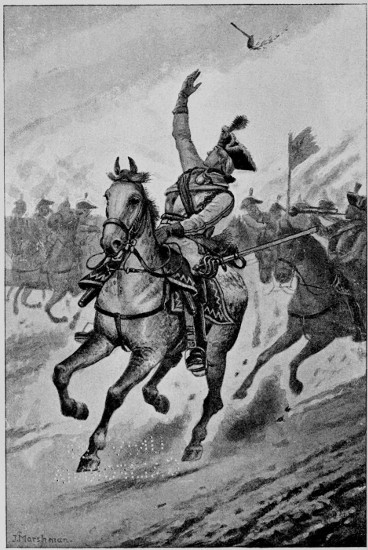

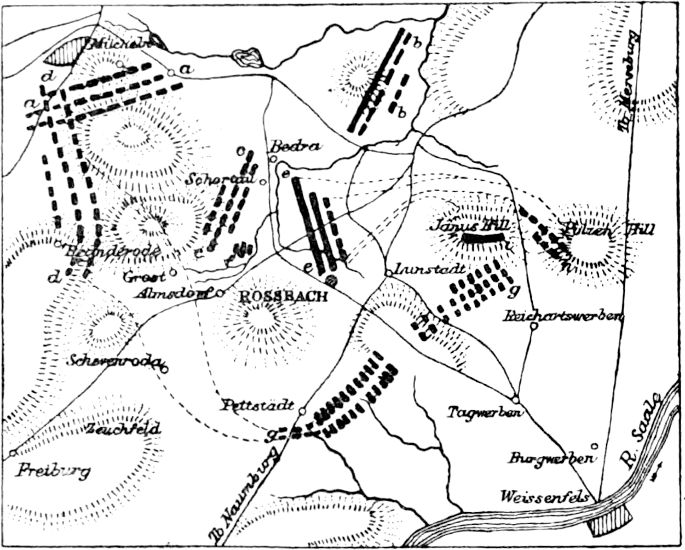

| Seidlitz at Rossbach | „ | 83 |

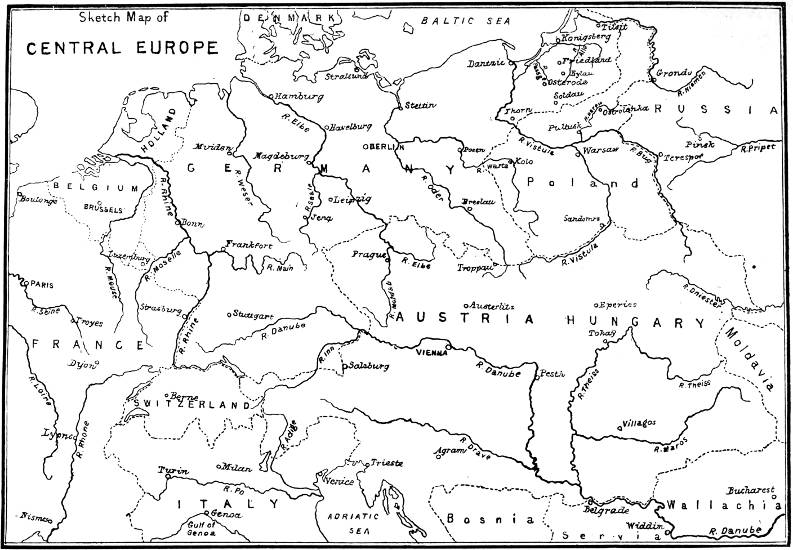

| Battles of Rossbach and Leuthen | „ | 85 |

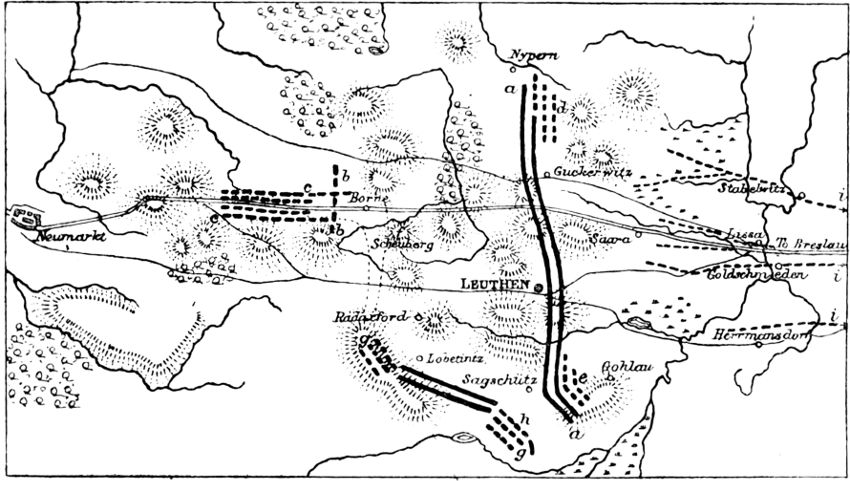

| Theatre of the Campaign in North Italy | „ | 110 |

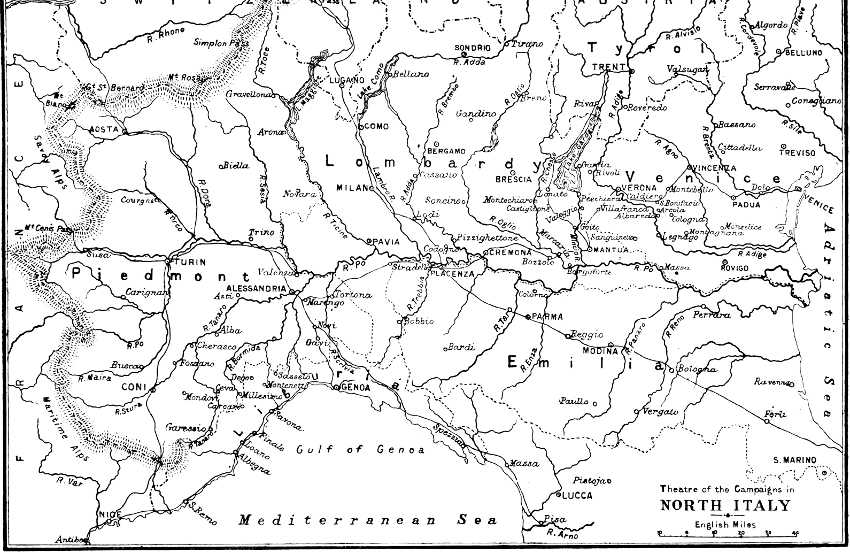

| Sketch Map of Central Europe | „ | 128 |

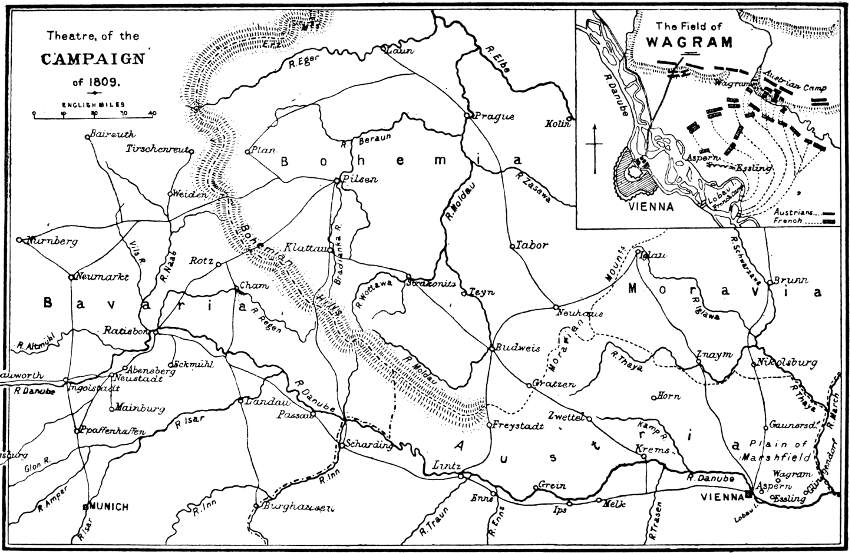

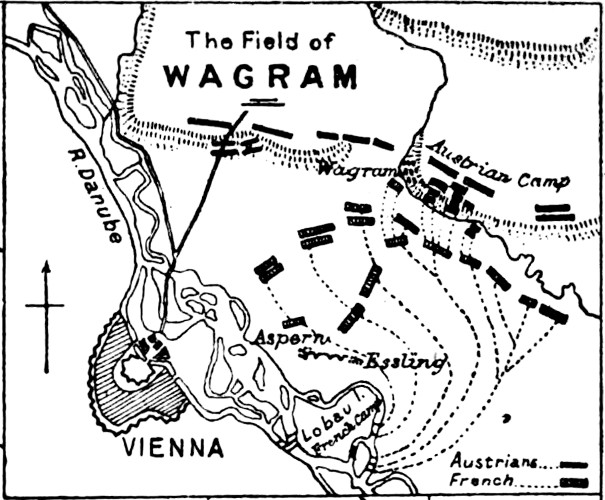

| Theatre of the Campaign of 1809 | „ | 160 |

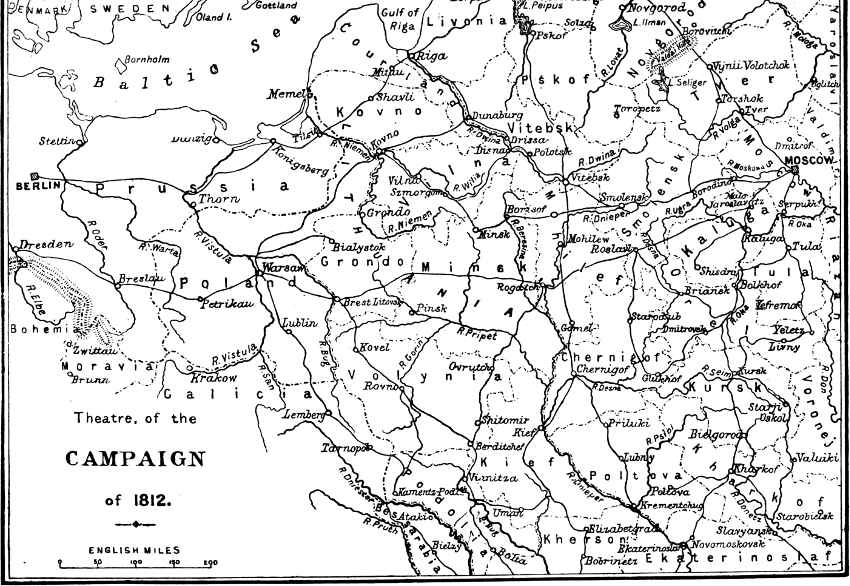

| Theatre of the Campaign of 1812 | „ | 174 |

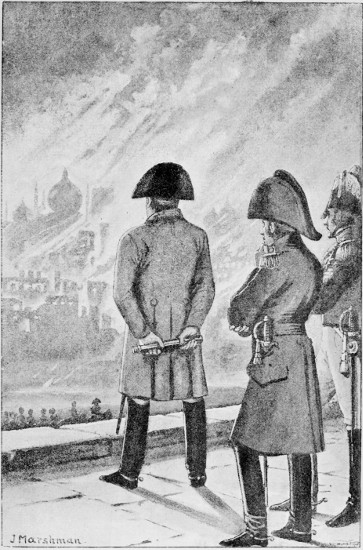

| Napoleon Watching the Burning of Moscow | „ | 178 |

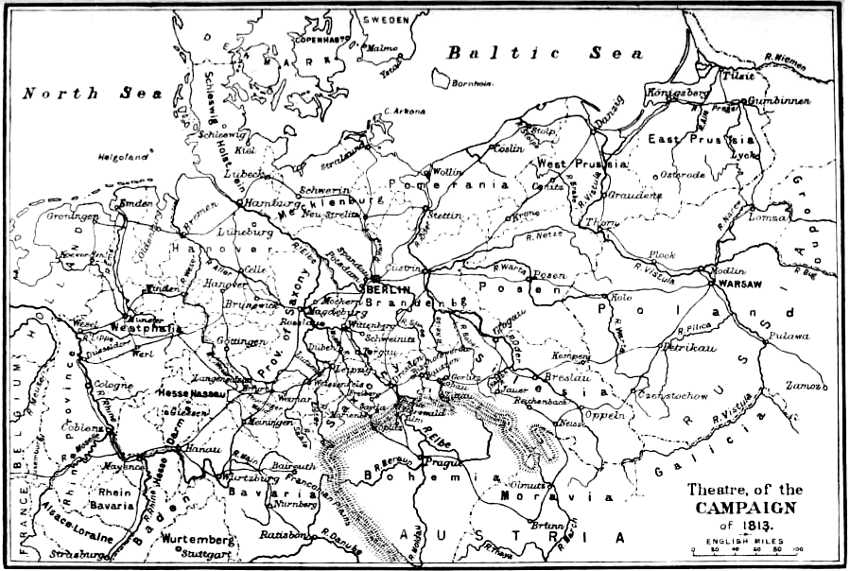

| Theatre of the Campaign of 1813 | „ | 188 |

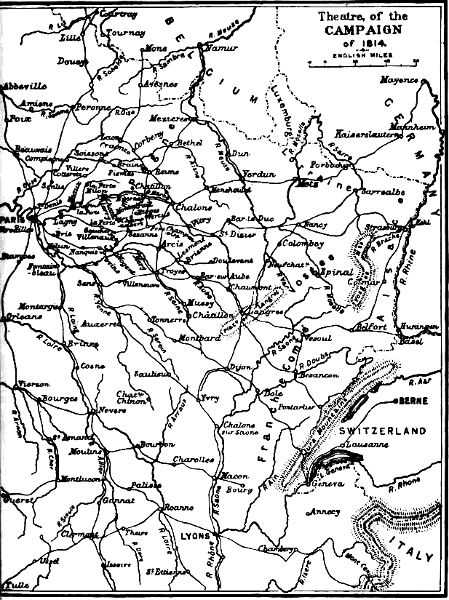

| Theatre of the Campaign of 1814 | „ | 206 |

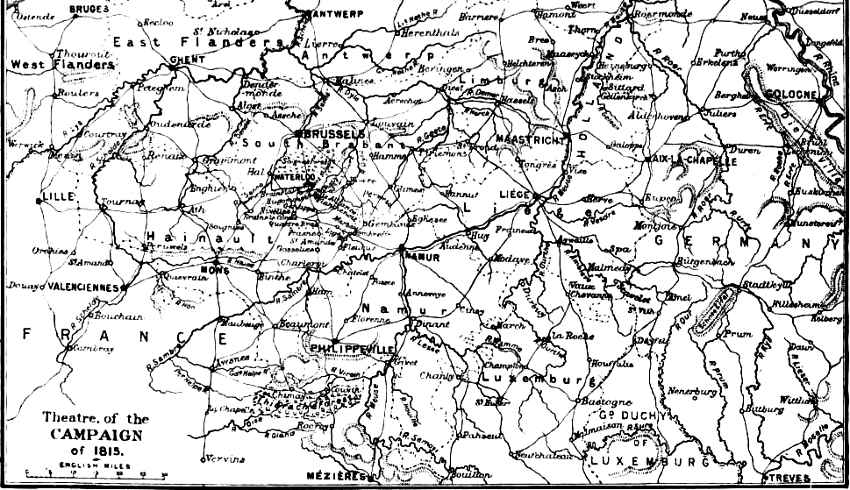

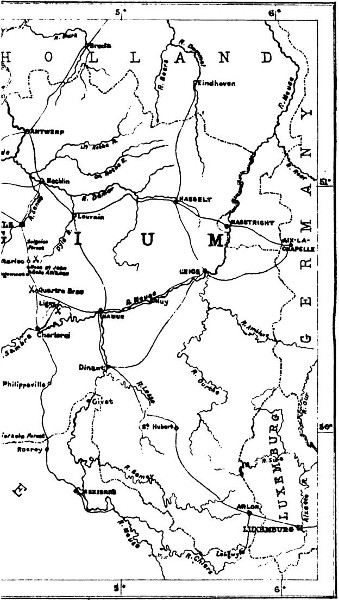

| Theatre of the Campaign of 1815 | „ | 218 |

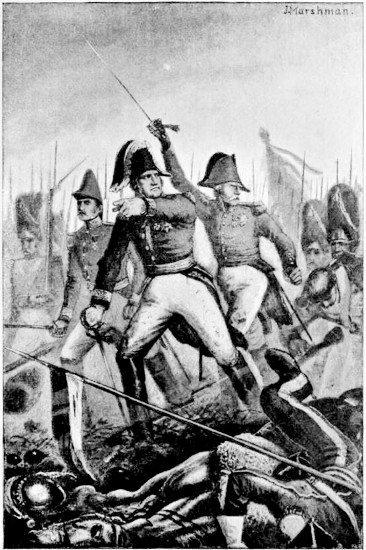

| Ney at Waterloo | „ | 226 |

| Wellington | „ | 238 |

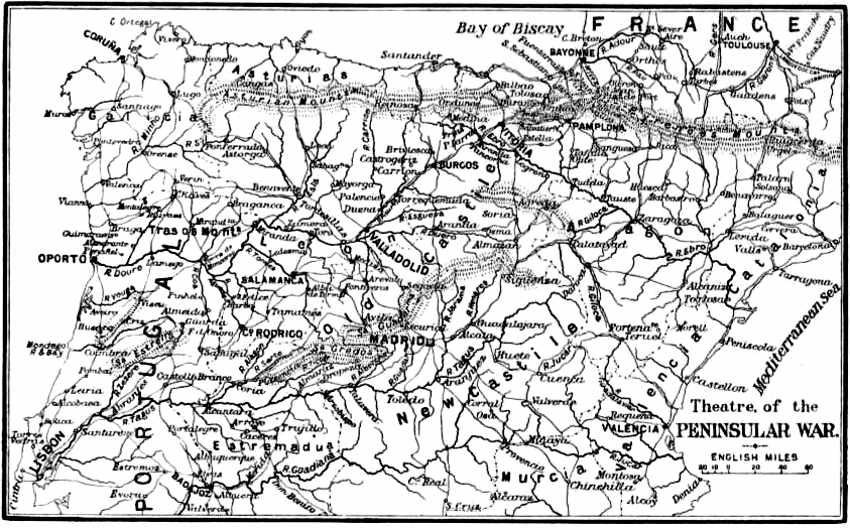

| Theatre of the Peninsula War | „ | 244 |

| Wellington at Talavera | „ | 248 |

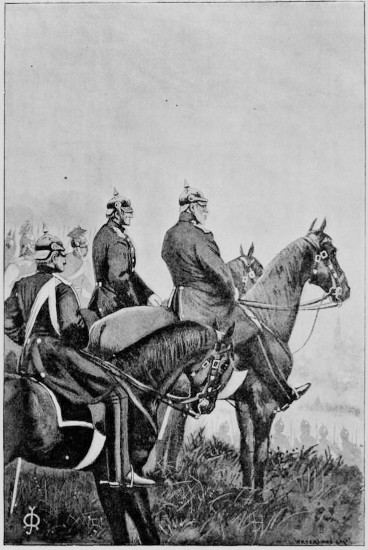

| Moltke and His Master | „ | 274 |

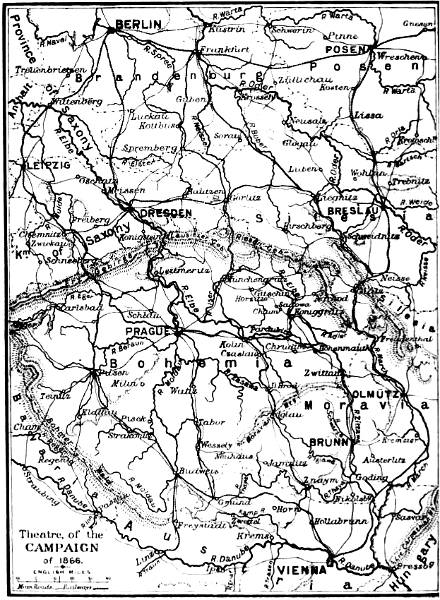

| Theatre of the Campaign of 1866 | „ | 281 |

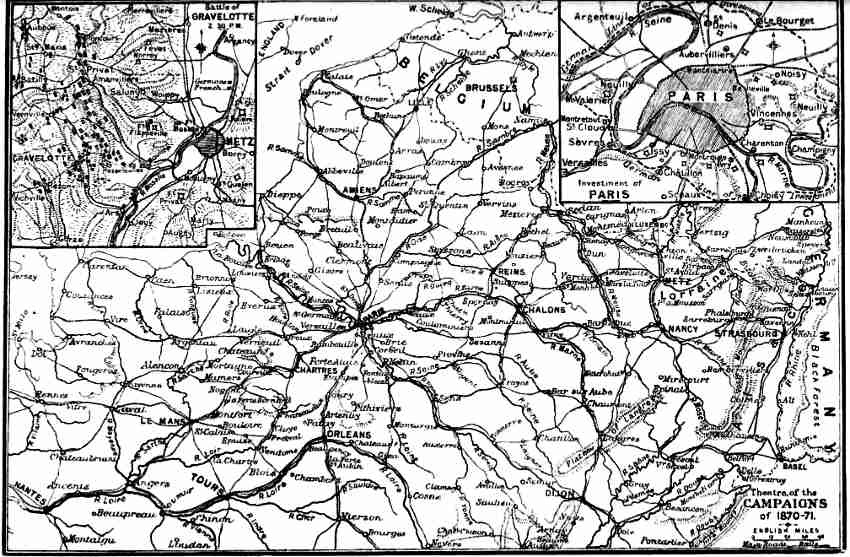

| Theatre of the Campaigns of 1870–71 | „ | 288 |

| Map of Belgium | „ | 315 |

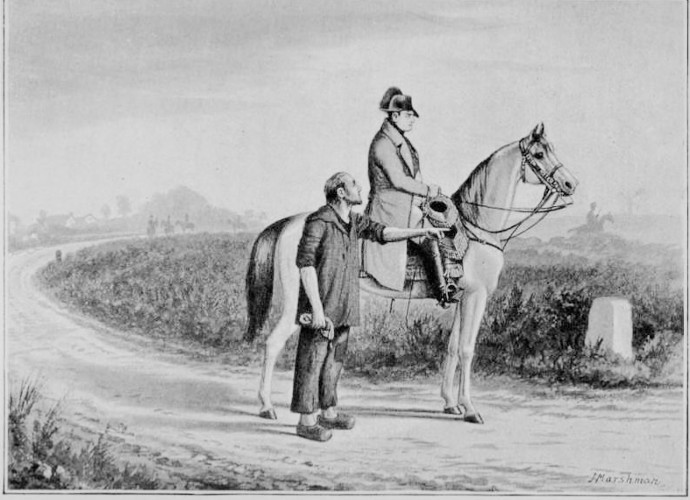

| “The Idol of the Soldier’s Soul” | „ | 320 |

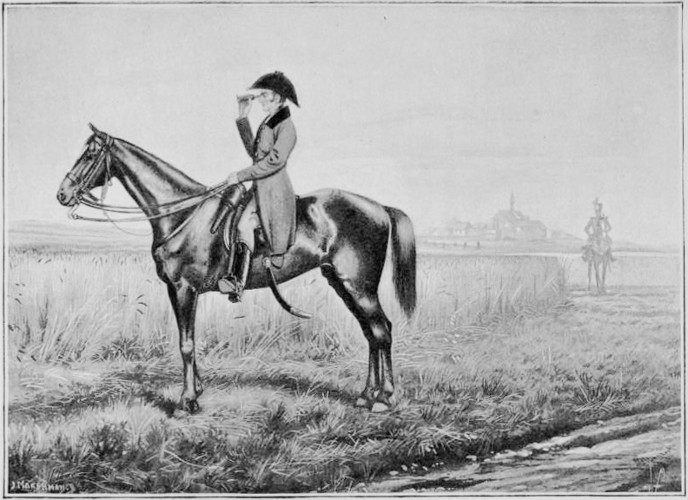

| England’s Hope, 1815 | „ | 324 |

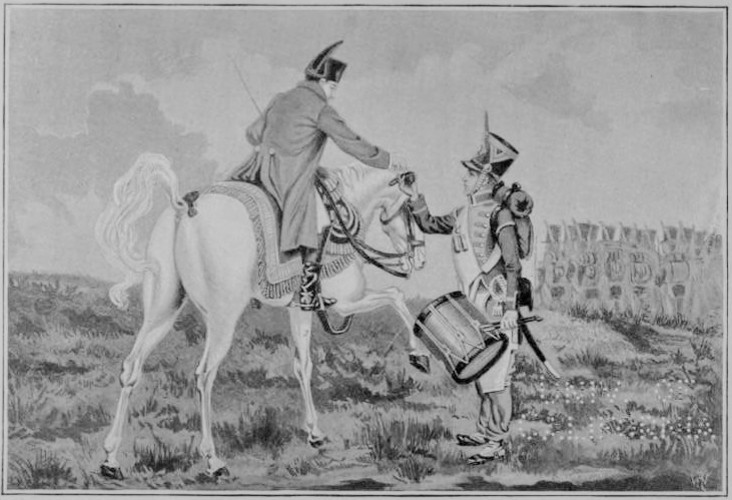

| “Tambour, faites-moi cadeau d’une prise!” | „ | 338 |

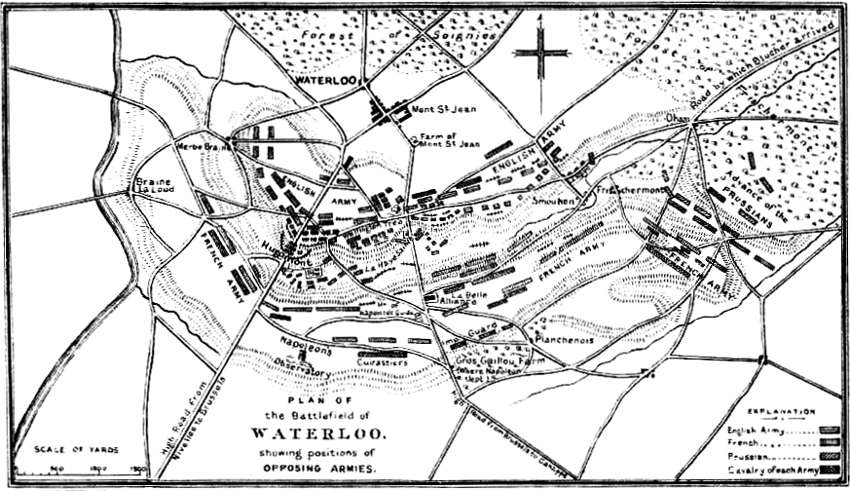

| Plan of the Battlefield of Waterloo | „ | 350 |

[v]

This volume consists of a series of essays on Great Commanders of Modern Times, and of two papers on the Campaign of 1815. I have to thank the Editor of The Illustrated Naval and Military Magazine, in which these studies originally appeared, for thinking them worthy of republication; and my acknowledgments are due to the press for many favourable notices. The text has been revised and slips of the pen corrected; but I have made no substantial change in what I had at first written.

A civilian, who attempts to treat of military affairs, ought to bear in mind the remark of Hannibal to the Greek sophist—“It is pretty, but it is all nonsense.” Yet it is with the art of war as with lesser arts; the unprofessional inquirer can attain knowledge of leading truths, though he may not be able to master technical details. Thucydides was perhaps not a soldier, but he observed this principle, and his narrative of the siege of Syracuse is a masterpiece. An ordinary writer is not worthy to unloose the shoe latchet of Thucydides; but he may, in this matter, imitate the method of the great Athenian; and if he has fair intelligence, works hard, and devotes laborious hours to reflecting on the exploits of great captains, he may become, in some measure, a sound military critic. These essays are not, I trust, wholly devoid of the only merits I claim for them.

[vi]

The papers on the Campaign of 1815, though only sketches, are the least fugitive pieces of any in this volume. I have formed my conclusions after a careful study of nearly every valuable authority on the subject; and I have had the advantage of some special information not yet given to the public. I have described Napoleon as easily superior, as a strategist, to his adversaries; while I have done justice to the great qualities displayed by Wellington and Blücher, as soldiers, I have dwelt on the grave strategic mistakes they committed. This will not gratify national vanity; but, in my judgment, it is the verdict which History will pronounce, nay, is already pronouncing, upon the questions raised by this mighty conflict, after a full and dispassionate investigation of the evidence.

My short account of the Battle of Waterloo may be flatly contradicted, or sharply criticized, in two particulars. I have described La Haye Sainte as having been captured at about 4 P.M. on the 18th of June; and I have left it to be inferred that only one column of the Imperial Guard actually reached the British line. It would take too long to explain why I have made these statements; I shall merely remark that the testimony in their favour seems to me greatly to preponderate.

Gartnamona, Tullamore,

September 1890.

[1]

GREAT COMMANDERS

OF

MODERN TIMES.

It will doubtless appear to some that this is a trite subject whose interest has long ago evaporated, exhausted by the numerous and competent pens which have treated it. The soldier, at all events, will judge otherwise, and conclude that the careers of that small group of demi-gods, commonly known as “great generals,” afford matter for consideration which can never tire, and which gains in interest the more it is analysed. As we vary our point of view, so the prospect grows upon us and the more we admire its details. Again, passing from select readers to the multitude, we have the sanction of a most sagacious observer of mankind for retracing the ground which has been so often trodden aforetime.

This being so, a concise summary like this of the campaigns of the most eminent of these great military leaders will not prove devoid of novelty and interest, as coming from the pen of one whom a civil career has left free from professional prejudice, and the study of law has trained to weigh[2] conflicting evidence. These biographical summaries include the following names:—

If in any particular we are at variance with the writer, it is that he hardly attaches sufficient importance to the influence of Turenne’s predecessor, Gustavus Adolphus, in the development of the military art. We ourselves agree with Gfrörer, his German biographer, that the Swedish king was the father of modern strategy, and the first really great general since Julius Cæsar. As Judge O’Connor Morris points out, many great soldiers lived during this long interval of time, but in our opinion (and it is in accord with Napoleon’s) it was the campaigns of the Swedish hero, and notably the Thirty Years’ War, which first revealed the dawn of that science which in later days was brought to such perfection by his successors. The tactical improvements introduced by Gustavus were extensive, though cavalry still played too exclusive a rôle in his engagements; his reforms in the armament and equipment of his troops were remarkable; nor is the military historian oblivious of his services to good discipline and morality by the Articles of War which he compiled and promulgated.

Gustavus Adolphus, when he ascended the throne at the tender age of seventeen, found his realm engaged in hostilities with Denmark, Russia, and Poland. His successor, Charles XII., curiously enough, was similarly entangled, but promptitude and good fortune in each case enabled the monarch to assail his enemies in succession and beat them in detail. The Danes already occupied the southern provinces of Sweden and, in the spring of 1612, they advanced in two columns, intending to move on Stockholm by the routes east and west of the Wettern Lake[3] which give access to the capital. This afforded the boy-king an opportunity for signalizing his latent military talent. Posting his forces at Jönköping, at the southernmost extremity of the lake, he struck alternately at the divided columns of the Danish army till he thrust them in disorderly retreat back to the sea-coast. Thus early was the leading idea which governed the defence of France in 1814 foreshadowed amid the rocks and lakes of Sweden. Peace with Denmark resulted in 1613, and through the mediation of James I. of England.

Russia was next assailed. Semi-barbarous at the time, that State was in the throes of revolution brought about by the extinction of the House of Ruric; and a project was actually on foot for her dismemberment, one half to go to Sweden, the other to Poland. But Muscovite patriotism defeated its execution. Michael Románoff was, in 1613, elected Tsar. Gustavus at the same time landed in Esthonia, but effected little beyond the capture of Gdoff, and in 1617 concluded peace, again through the good offices of England. The Thirty Years’ War was looming in the distance; the diplomacy of the Protestant Powers tended towards a union against the Papacy. Thus both dynastic and religious considerations recommended an attack on Poland to the judgment of Gustavus. Sigismund III., her king, was both a bigoted Catholic and the rightful though dethroned King of Sweden. Nothing could be effected in Germany leaving such an active and embittered foe in flank and rear. At first the King operated from Riga as a base, with the Dwina as his line of operations; but experience soon taught that, to effect his purpose, he must strike vigorously home at the heart of the adversary’s power. The theatre of war was therefore transferred to West Prussia, then directly subject to Poland, where he proceeded to establish a solid base on the coast, by making himself master of the fortresses of Frauenburg, Elbing, Marienburg, Stuhm, Mewe, Dirschau, and Oliva. Dantzig was besieged to facilitate communication with Sweden and, in this case, the line chosen by him for an eventual advance into the interior was the river Vistula. In all of his campaigns we find Gustavus keeping up his communications with the coast by means[4] of a great river; he lived in times when railways were not dreamt of and even roads could scarcely be said to exist. A commodious port on the Baltic was also necessary for safe communication with Sweden, and to serve as a depôt for stores. Thus his strategy was far in advance of the practice of his renowned successors Charles X. and Charles XII., who, great soldiers as they were, relapsed into pre-Gustavus methods, though they had both the King’s example and that of Turenne before them.

During this “Prussian War,” as the Swedish historians designate the struggle with Poland, Gustavus, involved himself in the Thirty Years’ War by sending troops to succour the hard-pressed garrison of Stralsund, then besieged by Wallenstein. This affront quickly brought a division of 10,000 Imperialists to the fields of Poland. Nevertheless, the belligerents concluded, in 1629, an armistice for the space of six years, which enabled Gustavus to turn his attention to the horrible struggle which was deluging Germany with blood, while securing his recent acquisitions on the Baltic. In one particular, however, he had persistently infringed the rules of conduct which should guide the great Commander: he had recklessly exposed his life during this Prussian campaign. During an action at Dirschau, the Swedes were on the point of victory when a bullet struck their chief in the shoulder, and he was borne insensible from the field. The action was stopped in consequence, and it was this wound which ever afterwards made it irksome for him to wear a cuirass, the absence of which probably occasioned his death on the field of Lützen. On several other occasions he escaped death or capture by a hair’s breadth. But it is only on critical occasions that the leader of a host ought to risk his life. The interests committed to his charge ought to be paramount in his estimation. Cæsar and Napoleon both well knew when such a course seemed necessary.

We now approach the crowning enterprize of this “Lion of the North,” his intervention in the Thirty Years’ War, with the glories which were compressed into the short span of life which yet remained to him: an enterprize which he had long dreamed[5] of in secret, and the fatal termination of which he probably only too plainly foresaw.

He landed on the island of Usedom on the 26th June 1630. Separated from the mainland by a narrow arm of the sea, it was admirably suited for the purpose of a maritime base of operations. Gustavus, the first who leaped ashore, sank on his knees, gave thanks to God, and, this done, seized a spade and began to dig the trenches. The island of Wollin was next subjugated, and the command of the mouth of the Oder by this means secured. Tilly was absent, dancing attendance on the Diet at Regensburg; Torquato Conti, his lieutenant, seemed paralyzed by the emergency; Wallenstein had justly been deposed from the supreme command. Embarking on the Stettiner Haff, the “Snow King,” as his enemies contemptuously nick-named him, seized possession of Stettin in July. In September he invaded the duchy of Mecklenburg, thus extending his area of supply and acquiring a broad and solid base for operating in relief of beleaguered Magdeburg. He drove Schaumburg, Conti’s successor, as far as Frankfort-on-the-Oder, and by the close of the year all the Pomeranian strongholds except Colberg, Greifswald, and Demmin, were in his possession. Thus much to prove how systematic was his system of warfare, and to show how carefully he fortified his base before venturing into the interior of Germany.

It must be noted that Gustavus continued active operations throughout the winter, in contrast to the habits of the age. In January 1631 his troops, clothed in sheep-skins, quitted Stettin, and New Brandenburg, Loitz, Malchin, and Demmin fell to their arms. These successes brought Tilly raging with fury on their track. Traversing Brandenburg amid blood and flame, he captured New Brandenburg by assault. Gustavus had skilfully concentrated his forces to protect the town at Friedland and at Pasewalk, but was informed by his lieutenants that the troops were so demoralized by the idea of encountering Tilly’s terrible bands that they were not to be relied on! In this desperate emergency the genius of the Swede stood by him. While Horn disputed the passage of the Peene and Trebel by the Imperialists, the King[6] ascended the Oder with the bulk of his forces, and, taking post at Schwedt, menaced the enemy’s right and rear so that Tilly rapidly retraced his steps, and, finding the Swedish position impregnable, continued his retreat to Magdeburg. When the field was clear, Gustavus, dashing out of his camp, appeared before Frankfort-on-the-Oder. On the 3rd April the assault was sounded, the gates were blown open by his petards, and the fortress succumbed amid great slaughter. Shortly afterwards Landsberg encountered a similar fate.

In May the fall of Magdeburg startled the civilized world—a disaster to be ascribed to the obstinacy and timidity of the Saxon and Brandenburg electors, who hesitated to afford Gustavus their support. In plain words, the King resolutely declined to advance to the city’s relief till he had safe-guarded his line of retreat in conformity with the maxims of what we now-a-days call strategy, but with him was merely martial instinct. Possession of the fortresses which secured his line of retreat was deliberately withheld from him by these Protestant potentates until too late. But the bestial fury of the Imperialist soldiery robbed Tilly of the fruits of victory. Instead of acquiring a pivot whence to dominate North Germany, he was constrained to slink back into Thuringia and the banks of the Unstruth.

The indignation aroused by this massacre throughout the Protestant world enabled Gustavus to coerce his brother-in-law of Berlin; a treaty of alliance signed and sealed safe-guarded the Swedish rear, and the King was in a position to execute a general advance across the Elbe which placed his strategic front in a direction parallel to his base. Having effected the passage near Tangermünde, he pitched his camp at Werben, near the confluence of the Havel and Elbe, across which he constructed a bridge. Immediately on receipt of the news, Tilly, uniting with Pappenheim at Magdeburg, flew to the assault, but soon experienced his opponent’s mettle. The King surprised the Imperialist advance-guard by night near Burgstall, and destroyed 2,000 of their cavalry. Tilly reconnoitred the works at Werben, but, not liking their aspect, retired to Eisleben. He had lost one quarter of his numbers, but[7] was there raised to 30,000 men by the arrival of troops, liberated from Italy by the treaty of Cherasco, under Count von Fürstenberg, so that he was in a position to enforce the Imperial summons that the Saxon Elector should surrender his army and revenues for Catholic purposes. The insolent demand drove that Prince into the arms of Sweden, and a convention was signed which placed his army together with Wittenburg at the disposition of Gustavus. Leipzig capitulated to Tilly and the Swedes crossed the Elbe, effecting a junction with the Saxons on the banks of the Mulda. Two days later (the 7th September) was fought the battle of Leipzig, which justified all the plans and precautions of the Swedish strategist.

Into the details of that great conflict it is not our business here to inquire. The splendid tactical coup d’œil of Gustavus has never been called into question. Let us rather consider how he profited by this amazing triumph. While the adversary withdrew into Thuringia, Gustavus struck right across his communications with Bavaria, pressing along the “Priest’s Lane,” the rich string of ecclesiastical principalities which then lined the banks of the Main—that march which is mentioned with admiration by the present biographer of Turenne. He thus provided himself with a new and fertile base for operating against the heart of the Empire at the expense of the Catholic party, while the Saxons invested Leipzig and defended the line of the Elbe from the enemy in Silesia. The Swedish King jealously guarded his communications with the sea, which were demarked by the rivers Saale and Elbe. Thuringia was garrisoned by Weimar troops; Halle by those of the Prince of Anhalt; Banér invested Magdeburg, while Tott held Mecklenburg in subjection.

On the 26th September the King’s army, leaving Erfurt, began to ascend the Main, and on the 10th October they took the episcopal fortress of Würtzburg by assault. This calamity drew Tilly in hot haste to the south. Towards the end of October his army, 40,000 strong, was bivouacked along the Tauber, where, on the night of the 23rd, Gustavus again cut up three Imperialist cavalry regiments which had bivouacked in an exposed position.[8] After a futile demonstration against Ochsenfurt, where he lost heart on discovering the Swedes drawn up beyond the Main, Tilly retreated in the direction of Nuremberg, when Gustavus, leaving Horn to observe his movements, sped along that river to Frankfort, into which capital he made his triumphal entry on the 17th November 1631. Meanwhile his antagonist, as if crushed in spirit by the swift ruin which had overtaken his fortunes, raided about Franconia at random, and seemed utterly incapable of arriving at any fixed determination. Finally he imagined the assault of Nuremberg; but a Protestant soldier, applying a slow-match to his store of gunpowder, blew it into the air together with the projects of his chief, who forthwith left Nuremberg and cantoned his troops in winter quarters around Nördlingen. The Swede, however, was more energetic, and crossing the Rhine at Oppenheim in defiance of the troops of Spain, gained possession of the great fortress of Mentz as the reward of his valour and activity. Here Gustavus spent Christmas with his Queen and Chancellor, Oxenstierna, who had come from Sweden to meet him. He was at the high pitch of his prosperity, courted by the petty princes of Germany and by the envoys of more considerable Powers. He was dreaming, it was said, of a Protestant Empire. But France, his ally, had taken umbrage at his successes. Richelieu endeavoured to arrange a pacification, but the sagacity or ambition of Gustavus impelled him to decline these overtures.

Early in 1632, Tilly, advancing from Nördlingen, surprised Horn at Bamberg, forcing him down the valley of the Main till he was supported by the King with 40,000 men. The Imperialists then retreated in their turn, and Gustavus, suddenly crossing the river, nearly succeeded in cutting them off from the Danube and Ingolstadt. Having entered Nuremberg in triumph, he continued the pursuit, and turned the line of the Danube by seizing, at Donauwörth, the only bridge left intact by Tilly between Neuburg and Ulm. Tilly hurried his troops from Ingolstadt to the Lech, in order to dispute the passage of the stream. Dissuaded from attacking by his generals, who urged that Wallenstein’s army in Bohemia was threatening his communications with the Baltic,[9] Gustavus persisted in his intention, replying that a demoralized enemy should be crushed without allowing him a respite for recovery: his own retreat by Donauwörth on Mentz was safe. He was out-voted in council, but acted on his own opinion, and his able dispositions were crowned with perfect success. The passage of the rapid current was forced. Tilly, like Turenne, was slain by an unlucky round-shot. Gustavus did not pursue vigorously—that art seems to have been invented by Napoleon—but Augsburg formed a substantial prize for the victor. Here was the cradle of the Protestant faith, and in days of religious bigotry this solemn entry into the city must have caused rapturous sensations in Lutheran hearts. Munich likewise received him with open gates.

While repressing a revolt of the peasantry the King was suddenly apprised that Wallenstein, having seized the Pass of Eger, had entered Franconia, seeking to force the Thuringian defiles, and opened communication with the Bavarians at Regensburg. This was the contingency foreseen by those who had condemned the passage of the Lech. Wallenstein, careless about his own communications or the interests of the Empire he served, and desirous only of fixing his own authority in North Germany while living at free-quarters, had thrust himself between the Swedes and the Baltic Sea. In June therefore the King, hurriedly retracing his steps, crossed the Danube at Donauwörth in the endeavour to cut off the Bavarians in their march northwards to join Wallenstein. In this he failed, but narrowly. The enemy had given him the slip by requisitioning carts for their conveyance. He entrenched himself at Nuremberg, was followed thither by Wallenstein, and a terrible drama of slaughter, disease, and starvation, which seemed to typify all the plagues of Egypt, was enacted around that city. It resulted in a drawn battle; and the martial reputation of the Swedish king suffered proportionate diminution. He had been withstood successfully; nay, more, he had been the first to withdraw from it. For this his moral nature was perhaps responsible. He could no longer endure the pandemonium of human suffering which was in progress around him, while to the cynical Wallenstein all this was a matter[10] of indifference. Strangely enough the Imperialists retreated north, the Protestants southwards. Wallenstein swept through Saxony with his ravenous, ruthless hordes; Gustavus once more subjected Bavaria to his requisitions. War was to be made to support war; but let us bear in mind that it was the fond hope of Wallenstein to establish an empire for himself in North Germany; while it is surmised that his adversary held not dissimilar views, though with nobler aspirations; at all events his strategic base at this time was the city of Mentz and the fertile valley of the Rhine in its proximity. But the inhuman atrocities of the Imperialists in Saxony were again too much for the sensitive nature of Gustavus; in addition to which, the statesman will note that the Elector, a dubious ally, was likely to make terms with the oppressor, and this would signify a permanent severance from Sweden which could not be acquiesced in. On the 11th October, the King directed his army north viâ Donauwörth in two columns, and by the end of the month was able to review them reunited at Erfurt. Unfortunately his allies, the Saxons and Lüneburgers were still beyond the Elbe, and a flank march in front of the concentrated Imperialists became indispensible in order to effect a junction; for Wallenstein and Pappenheim had judiciously united their forces near Leipzig, while George of Lüneburg had disobeyed the King’s orders, which enjoined him to rendezvous in Thuringia, and the Saxon Elector, as if paralysed by dread of Wallenstein, was still in the depths of Silesia. Grimma was the point indicated for concentration, thus well within striking distance of the enemy; and Gustavus left Naumburg in this direction on the 5th November. On the march, however, an intercepted letter was placed in his hand. He learnt that Wallenstein, deeming the campaign ended for that year, had permitted Pappenheim with 10,000 men to depart on a raid into Westphalia, and had cantoned the remainder of his forces in and around Lützen. At this sudden crisis, Gustavus proved his title to a niche among the “demi-gods” of war. Instantly wheeling his columns to the left, he advanced to the attack across the vast plain which leads to the town of Lützen. But “Man proposes, God disposes,” an adage[11] which is peculiarly applicable to warlike enterprize. The passage of the Rippach stream, strenuously defended by Isolani’s Croats, stopped the Swedes till nightfall, a delay which enabled Wallenstein to assemble his scattered forces; while a dense fog next morning, which did not lift till 11 o’clock, prevented the attack taking place at an early hour, and so afforded time for Pappenheim to return with his troops to the field ere the close of the battle. But by this time the great King had breathed his last, and Pappenheim roamed the field in vain in order to cross swords with him. After a desperate struggle, the Catholics suffered defeat, but the loss of the Protestant champion converted disaster into a victory for their faith.

In the long struggle which followed after his death, and lasted no less than sixteen years, the name of Turenne first became known to fame.

[12]

I remember hearing a soldier of promise remark that war had so completely changed that it was useless to study the campaigns of Napoleon. This foolish paradox represents ideas too common among military men of late; and is about as true as an old notion, rudely exploded on the great day of Austerlitz, that Frederick’s usual method of giving battle was so infallible, under all circumstances, that a long flank march under the guns of an enemy in position is scientific strategy. An opinion is abroad that German genius has wrought such a revolution in the art of war, that all that has gone before is obsolete; that Moltke is a faultless commander, whose exploits surpass those of all chiefs; nay, that mechanism and organization are the best means of assuring success to armies in the field. It is time to expose the perilous errors, mixed with particles of truth, in these shallow statements. The subordinate methods and rules of war have been largely changed, in the progress of the age, and especially through its material inventions; but the higher parts of the art can never vary, for they have their origin in the faculties of man, as grandly developed in Cæsar and Hannibal as in the great captains of modern times; and the exhibition of these, whatever may be the conditions of time and other accidents, will always be matter of fruitful study. As for the “faultlessness” of Moltke, that distinguished man would be the first to admit that, like all generals, he has made grave and palpable errors. Extraordinary, [13]indeed, as have been his achievements, his campaigns in Bohemia and France show that his strategic and tactical mistakes were many; and though he is a real chief of the Napoleonic school, he has done nothing that can be compared to the movements round Mantua in 1796, to the Alpine march that led to Marengo, to the manœuvres that immured Mack in Ulm, to the last swoop on Belgium in 1815. That mechanism and organization count for much, is a truth as old as the days of the Legions; but the genius of leaders in directing armies has always been the chief element of success in war; and, so far from this being less the case at the present day than it has been of old, this influence is now more than ever decisive. It is obvious, in fact, that the powers of the chief will have increasingly greater effect as armies have grown to immense proportions, and military movements have become more complex, more extended, and, above all, more rapid; and if a mere tactician will, perhaps, do less, on a given field, than a century ago, victory in a campaign will, in this age, in the main, depend on superior strategy.

TURENNE.

I purpose, in this and subsequent articles, to endeavour to illustrate the main principles and permanent lessons of the art of war in brief sketches of the lives and the deeds of famous commanders of modern times; and I shall try to dispel the notions that military history before Sadowa is a mere old almanack, and that the exclusive study of modern Prussian routine is the best education of the accomplished soldier. For authority, I need only refer to Napoleon.[1] “Tactics,” wrote that master of war, “manœuvres, the science of the engineer and of the artillerist, can be learned in treatises, like geometry; but knowledge of the high parts of war can be acquired only by study of the history of war, and of the battles of great captains, and by experience.”

I have placed Turenne at the head of my list, not only because he comes first in time, but because the art of war made immense progress during the long career of this illustrious chief, was greatly improved by his powerful genius, and gradually acquired a modern[14] aspect. Before I attempt, however, to sketch his exploits, I would say a word on the condition of the art before it passed into his master hand. The leading maxims of war were fully understood; and great commanders had, in many a contest, shown what the qualities are which ensure success in the strife of opposing armies. That a general in a campaign should have a distinct object, that he should steadily endeavour to carry it out, and that he should so combine his means as to promote his ends, were recognised and approved principles; and the value of intelligence in great movements, of energy and skill in the direction of troops and of careful administration in military affairs, had been illustrated by fine examples. Passing, too, from these universal truths, the principal rules of strategic science had been ascertained in their main outlines, and ably brought to the test of experience; nay, war had exhibited grand instances of strategy, whether of offence or defence, which, founded as it is on the peculiar character and faculties of individual men, had never perhaps more noted champions than Hannibal and the Roman Fabius. The advantage, for instance, of having the possession of interior lines on a field of manœuvre had been clearly perceived by Guébriant, and was repeatedly seen in the Thirty Years’ War; Gustavus had shown what could be accomplished by rapid and well concerted movements against the communications of a hostile army; and Wallenstein had proved how great could be the power of firmness, endurance, and patient skill in resisting even the most able enemy.

The art, however, owing to many causes, had not as yet been nearly developed, and had not even approached its present perfection. Fine movements, indeed, were occasionally made; the march of Gustavus, for example, down “the Priests’ Lane,” which carried him into the heart of the Empire, and some of the marches of Parma, in an earlier age, remain noble specimens of audacious genius. But strategy was still, so to speak, cramped and limited by all kinds of obstacles, and it could not attain the freedom and grandeur which it has exhibited in the wars of this century. On every theatre of war, from Vienna to Brussels, the state of husbandry was backward in the extreme; there were immense wastes of morass[15] and forest; and even the plain country was not half cultivated. The roads, too, were comparatively few, and even the main roads were, for the most part, bad; the great rivers had but few bridges, and minor streams were not bridged at all; and the passes across the chief mountain ranges were mere paths and tracks, intricate and difficult. The natural impediments to the march of armies were, therefore, many and often formidable; and these were greatly increased by the numerous fortresses which had grown up since the feudal age, and which, covering frontiers and main approaches, and barring the way to an invader’s progress, could not easily be passed by even a daring enemy. In addition to this, the means of supply and of transport possessed by modern armies, either did not exist or were very scanty; magazines, trains, and the many appliances that enable troops of this day to live and move, were quite in an embryonic state; and a general was often compelled to rely on plunder and rapine to support his soldiery. In these circumstances, the rapid manœuvres and the grand movements leading to decisive battles which belong to the age of Napoleon and Moltke, could be witnessed only on a small scale, and occurred only in rare instances. War, as a rule, had a contracted aspect; and its ends were often different from those of our time. Beset by impediments, even the greatest chiefs were frequently unable to make long marches, or to attempt anything like audacious strategy; and though Gustavus had fully seen that the main object of a campaign was to cripple an adversary in pitched battles, this was not yet an accepted principle. The art of war still largely consisted in wearing out an enemy in petty combats, in devastation, and wrecking a country, in incursions attended by partial success; and the aim of commanders often was, not so much to defeat a hostile army as to find good quarters in an unravaged province. Campaigns were late, slow, and had small results; as a rule, winter campaigns were rare. Above all, it had become a maxim that before invading an enemy’s country it was necessary first to reduce its fortresses; months, and even years, were taken up in sieges; and the art, it has been said, “seemed to flit around strong places.” In short, owing to the local accidents and peculiarities of the[16] seventeenth century, strategy, though in existence and in a state of progress, was still quite immature and imperfect.

The science of Tactics had at this period made less progress than that of Strategy. It had become recognized that the three arms should act in concert, and support each other; and a distinct unity was seen in battles, unlike the desultory combats of the Middle Ages. But one great principle of modern tactics, that an army should be arrayed on the ground, not according to any unchanging method but so that each arm should turn to account the character and local features of the spot, had scarcely entered the minds of men; it certainly had not been fully established. An army took its position in a settled order: the cavalry always on either wing, the infantry in the centre, and the guns in front. There usually was a considerable reserve; and the importance, for instance, of so placing cavalry that it could fall on an enemy from under cover, or of so distributing guns that they could enfilade infantry, or throw a concentrated or plunging fire, was as yet little, if at all, understood. In these circumstances the marked diversity which is a characteristic of modern battles, which makes no one exactly resemble the other, and in consequence of which the tactical skill of a chief in command is taxed to the utmost, existed only to a small extent. There was a distinct sameness in the battles of the age, and these usually consisted in a contest between the hostile footmen and guns in the centre—a mere partial engagement without manœuvres—until the success of the cavalry on either side enabled it to assail the flank or the rear of the enemy. The tactics, therefore, of this period were very different from those of our own; and this difference was made greater through the change in the relations of the three arms, and in the efficiency and the power of infantry, which has taken place since the seventeenth century. At this period, cavalry was by far the most important and capable arm; it was, in fact, the manœuvring force in the field. The value of artillery was still unknown, for guns were comparatively few and ill served; and footmen, often inferior in numbers to horsemen, were a combined array of musketeers and pikemen, invariably marshalled in dense masses, unequal to[17] quick and difficult movements, and utterly inferior to the infantry of this day in relative strength, in the efficacy of fire, in ability either to attack or defend, and in evolutions and manœuvres in the field.

Under these conditions, a general gave his chief attention to his most powerful arm; artillery and foot played a subordinate part; and, as I have said, the event of battles was usually decided by a charge of horsemen launched against an exposed side of a hostile army. But if the tactics of those days were unlike ours, it is a mistake to suppose that they did not afford full scope to superior skill and genius. The front of battles was comparatively small; a general’s eye could command the whole field, and victory usually depended on the inspiration of the chief, who, with ready design, and at the fitting moment, could direct his cavalry in collected force against a hesitating and already shaken enemy. This was the distinctive gift of the famed Condé, and of that born master of tactics, Cromwell; it was conspicuously proved at Rocroy and Marston Moor; and it is a gift of the very highest order, if it does not exactly resemble the faculties which prepared Ramillies, Leuthen, and Austerlitz. For the rest, an army of this period, considered as a whole, was very different from an army of the nineteenth century; and this, too, affected the art of Tactics. In numbers, it was comparatively small; 30,000 men would be a very large army. It was deficient in unity and combined strength, for it was a mere array of battalions and squadrons; divisions and corps were as yet unknown, and a general-in-chief did not possess the supreme authority now entrusted to him. The discipline, too, and the organization of such an army was still far from good; the troops did not even wear a uniform, and were more akin to a feudal militia than to regular and trained soldiers; the muster rolls were always incomplete, owing to the Falstaffian tricks of officers, as yet subject to little control, and mutiny and insubordination were too common. Such an army, from the nature of the case, would be a weak and uncertain instrument of war; and this alone made the tactics of the day less decisive, as a general rule, in results, than those of later great masters of war.

The art of war at this time, in short, has been happily compared[18] to a bird, which eagerly spreads its wings for a flight, but is held, checked by restraints, to the ground. I pass on to the great captain whose life and career I attempt to illustrate. Turenne was born in 1611, a scion of the princely noblesse of France, his father being Sovereign Lord of Sedan, his mother a daughter of William the Silent, who largely transmitted the high qualities of the House of Nassau to her renowned offspring. As has happened with other famous warriors—with Luxemburg, William III., and Wellington—the future master of war was a sickly child; but from the earliest age he showed strength of character. He was educated with remarkable care; and though, unlike Condé, he was not a precocious genius—he remained heavy and dull in exterior through life—still, even in those years, the assiduous care with which he studied the campaigns of Cæsar, and followed Alexander in his march to the Indus, revealed the natural tendencies of the coming strategist. Turenne entered the service of the Seven Provinces as a private soldier at the age of fourteen; and under the care of his maternal uncle, Maurice of Nassau, and his successor Henry, he took part in the long wars of sieges which marked the conflict with Spain in the Low Countries. He fought his way steadily up from the ranks; he seems to have owed little to birth or to favour; but, though he gained distinction at the siege of Bois-le-Duc, this was not the natural bent of his genius, and the value to him of these essays in arms was probably to teach him the important truth, which he illustrated in many striking instances, that “in war you should march and not besiege,” that you should rather outmanœuvre and defeat your enemy than waste months in attacking fortresses which fall of themselves after success in the field.

In 1630, when twenty years old, Turenne obtained a regiment from Louis XIII. He addressed himself with untiring diligence to the discipline and the training of his men; and, like Wellington—in matters like this he had much in common with our great countryman—he was soon known as a capable officer, and could justify his boast that his “corps was equal to the best troops of the King’s household.” The young colonel, however, made no way at Court; its frivolity and luxury were distasteful to a mind singularly[19] modest and sedate; its licentious recklessness shocked a nature formed by the rigid tenets of Calvin; and while Condé was already a star at the Louvre, Turenne, taciturn and awkward, was scarcely noticed. The future great chief of the armies of France served for many years in a subordinate rank; he passed, in fact, through all inferior grades, though his merits were recognized by good judges; but if this term of probation was unduly long, its experience, he has said, was most precious, for it “fully taught him a soldier’s calling.” Long before the close of the Thirty Years’ War, Turenne was known as an able man, though his great powers had not yet been developed. He was singled out for honours at the great siege of Breisach; he showed remarkable skill and firmness in covering a disastrous retreat from the Sarre; and he had won the praise of La Valette and Saxe Weimar for his singular steadiness and coolness in the field, and for the paternal care he took of his troops, a quality in which his comrades of the noblesse, brave, but unreflecting, were as a rule wanting. The chief point, however, of permanent interest in this early part of the career of Turenne is the evidence it affords of the dawn of those powers for which he was to be proudly eminent. He occasionally had an independent command, and in this position he never failed to display the gifts of a true strategist. In 1636 he made a forced march, by which he surprised and routed Gallas. He captured Maubeuge, combining his movements with those of his chief with remarkable skill. At the siege of Turin, in 1640, he out-manœuvred and baffled his enemy, and kept away the relieving army; in 1643 he made a feint against Alessandria, which deceived his adversary, and enabled him to seize the fortress of Trino.

In 1643, as the Thirty Years’ War was nearing its end, Turenne received the staff of a Marshal of France. His achievements during the next two years will repay a careful reader’s attention; but I can only glance at them in this sketch, for they scarcely reveal his peculiar genius. He took part, under the Grand Condé, in the desperate combats around Fribourg, marked by the daring and vigour of his chief, but, in Napoleon’s judgment, worse than useless; we see proof of his strategic powers in his operations[20] between divided enemies in the Palatinate at the close of 1644; and I cannot doubt but that the fine march of Condé down the Rhine, after the fall of Philippsbourg, which made the French masters of Landau, Mayence, and other cities on the German bank, was due to the inspiration of Turenne. In 1645, having advanced to the Tauber, and overrun the Franconian lowlands, the marshal was surprised and routed by Mercy—a Lorraine chief, little known to fame, but a great captain of the Thirty Years’ War; and we can gather from this and other instances that the genius of Turenne, rather profound than quick, made him less admirable in the sphere of tactics than he was in the higher parts of war. He was soon again under the command of Condé, and he led the left wing of the French army in the terrible struggle around Nördlingen; but though he contributed to the success of the day, the glory of the victory, doubtful as it was, belongs wholly to his renowned chief, whose tenacity, boldness, and insight on the field, plucked safety and even a triumph from danger. The campaign of 1646 distinctly brought out for the first time the special gifts of Turenne in full relief, and to this day is a strategic masterpiece. The Marshal was on the French bank of the Rhine, near Mayence, as the year opened, and Mazarin had directed him to remain in his camps trusting to a pledge that the Duke of Bavaria would not send aid to the Imperial forces. The Duke, however, broke faith and marched against the Swedes, hoping to defeat them as they moved into Westphalia, and to join hands with the Archduke Leopold, advancing in force from Western Austria; and had success attended this operation France would have probably lost her best ally. Turenne made up his mind at once; without waiting for a word from his Government, he broke up from Mayence, moved down the Rhine in a march of astonishing speed for those days, and, having crossed the river as far north as Wesel, he effected his junction with the Swedish chief, Wrangel, on the Lahn, having forestalled his enemy by a movement of singular skill and daring.

THEATRE OF WAR

IN

GERMANY]

Turenne and Wrangel were now at the head of an army of more than 20,000 men; the hostile force, about equally strong, fell back [21]to Friedberg, north of the Main; and the Archduke, clinging to his communications, began to retreat to the Danube by an exterior line, through Schweinfurth and Nuremberg, towards the Bavarian plains. Turenne seized the occasion with the eye of genius; holding the chord of the arc, he advanced through Franconia by forced marches, and attained Dönauworth, and while his adversary was toiling on his eccentric movement, he crossed the Danube, pushed on to the Lech, and boldly assailed the great place of Augsburg.[2] He failed in this siege, having been persuaded by his Swedish colleague to attack Rain, a little fortress of no importance; but his subsequent operations were marked by genius and constancy of the highest order. The Archduke, after weeks of delay, had crossed the Danube and approached the Allies, and he took a strong position from Landsberg to Memmingen, in order at once to cover Bavaria and to threaten the communications of his audacious foes, who had advanced into the heart of Germany, far from the Danube and even from the Rhine. It was now November, and an ordinary chief would have fallen back to seek winter quarters, foregoing the gains of the whole campaign; but Turenne resolved to take the bolder course, and, against the advice of all his lieutenants, he made a feint on Memmingen, and then, moving rapidly, seized the communications of the Archduke at Landsberg and forced him, baffled behind the Inn. This splendid campaign—a game of manœuvres in which decisive success was gained without the risk of a single battle, which shows the highest parts of a master of war, and in which Napoleon, a draconic critic, can detect only a small mistake, the weakening the attack on Augsburg to besiege Rain—detached Bavaria finally from the Imperial cause, and, in truth, all but closed the Thirty Years’ War.

The campaign of 1647, in which Turenne overcame a dangerous mutiny of the German auxiliaries in the French army, is one of the many instances of the strength of his character. That of 1648, the last of the Thirty Years’ War, is a repetition of that of 1646, but scarcely gives proof of equal genius; it is chiefly remarkable[22] as the first occasion in which Montecuculi, a worthy antagonist, and a friend of Turenne in after years, exhibited his capacity in the field. I pass rapidly over the next three years—an unhappy passage in the career of Turenne—for they saw the most illustrious captain of France in arms against the State and the National Government. Strong affection for a despoiled brother, and the artful wiles of a beautiful siren—this was a weak point in the warrior’s nature—caused Turenne to join the rebels of the Fronde; but though excuses may be made for him, history has justly condemned his conduct, and, like Marlborough but much less worthy of blame, Turenne is an instance how revolution can pervert even the noblest faculties. Turenne showed his strategic gifts in the contest; he proposed to advance to Paris and to dictate peace, but he was overruled by his Spanish colleagues, and he was soon afterwards beaten by Du Plessis Praslin, in a pitched battle not far from Réthel, a point of capital importance in the wars of that age. Turenne’s tactics, Napoleon remarks on this occasion, were faulty and slow—this, in truth, was his least perfect part; but Turenne, and even Condé, never displayed that pre-eminence in war when opposed to France which they exhibited when in command of Frenchmen.

Turenne made his peace with Mazarin in 1652. Though naturally distrusted by a Court he had betrayed, he soon made his extraordinary powers felt, and in a few months he obtained the supreme direction of military affairs in the war of the Second Fronde. Civil war is never an attractive subject, but in this contest Turenne was opposed to the Great Condé and the forces of Spain, and events have great and peculiar interest. Turenne’s splendid faculties strategic insight, skill in large manœuvres, judgment and constancy were never perhaps more grandly seen. He proved himself far superior to his brilliant rival, though it is but fair to say that the genius of Condé was repeatedly baffled by Spanish obstinacy, and Turenne was justly hailed as the Saviour of France and of the House of Bourbon when in the extreme of danger. He out-manœuvred Condé at Blêneau, near the Loire, in a passage-of-arms singled out by Napoleon, as a marvellous instance of military skill; and he[23] would probably have brought the war to an end had Mazarin followed his sagacious counsels to march straight on Paris in 1652. When he was compelled to obey the too cautious minister, and to undertake the siege of Etampes—a timid half measure of no avail—he raised the siege at a moment’s notice, with the decision that belongs to great captains only, at the intelligence of the approach of Charles of Lorraine; and the stand he made against the Duke’s army, which prevented its junction with that of Condé, very probably saved the royal cause. Turenne distinguished himself in the murderous fight of St. Antoine, under the walls of Paris, and in the subsequent game of manœuvres with Condé; and his commanding genius was again seen when a double Spanish and Lorraine army marched towards the capital to assist Condé, and threatened the Government with utter ruin. The Regent and Mazarin, in the extreme of peril, wished to abandon Paris, and to fly to Lyons; but Turenne saw that this precipitate retreat would prove fatal to the Bourbon cause. He insisted on keeping his army on the spot, and, standing in the path of his divided enemies, he baffled the Spaniards on the line of the Somme, held the Duke of Lorraine successfully at bay, and prevented either foe from joining hands with Condé. The results of this generalship, not unworthy of the unrivalled captain of 1814, were magical and completely decisive. Condé and his troops were forced to leave Paris; the foreign invaders fell back to the frontier; the young King and the Court entered the capital, to the joy of the citizens; the Government was replaced in its seat, and Turenne read in the nation’s eyes how he had closed the civil war and restored the throne. In this remarkable contest he had given proof, from first to last, of the highest faculties; but those, perhaps, which most deserve notice are his insight in perceiving that Paris was the centre on which to direct all efforts; his firmness in compelling the Court to cling to the capital at any risk, and his astonishing skill in repelling the enemies converging against him in greatly superior force.

Though Mazarin had been replaced in power, Spain, in 1653, was still able to send a larger force into the field than France. Turenne conducted a Fabian campaign on the Oise, baffling the[24] Archduke—his foe in 1646—and taking care to avoid Condé; and he exhibited once more what Napoleon has called “the divine side of the art of war,” in making a stand in a strong position, where Condé had all but brought him to bay, and imposing upon the cowed Spanish chiefs. In 1654 the reviving strength of France began to prevail over Spain in decline. Turenne appeared at the head of a large army, and he successfully raised the siege of Arras, the capital of Burgundian Artois, in a night attack of remarkable daring, in which he surprised the Austrian chief and kept skilfully away from Condé’s lines. This was one of his greatest exploits in the field, and France acquired a marked ascendency over her enemies along her northern frontier. I can only refer to the next three campaigns, in which the strategic gifts of Turenne and his admirable firmness were again made manifest. True to his maxim, then a revelation in war—“always march rather than make sieges”—he gradually advanced to the Scheldt and the Lys, turning their fortresses by operations in the field, and sitting down before them as seldom as possible; and in less than three years he had overcome barriers[3] which hitherto had been deemed invincible, and which had been theatres of war for centuries without great or decisive results, a feat of generalship which astounded Europe. The genius of Condé more than once shone out in his efforts to avert Fate. He destroyed a part of Turenne’s army, in the hands of an incapable colleague, at Valenciennes, in 1656; and he brilliantly raised the siege of Cambray, an exploit marked out for praise by Napoleon.

The arms of France, however, directed by Turenne, made steady progress despite these checks, and the fine campaign of 1658 brought the contest with Spain to a glorious close. By this time Turenne had secured his position in Spanish Flanders, and was formidably strong. The England of Cromwell was in a league with France, and the allies resolved to attack Dunkirk, the strongest place on the seaboard of Flanders, and long a seat of piracy against British commerce. The fortress was difficult in the extreme to master, not so[25] much owing to its works and defences as to the obstacles formed by the sea, the marshes, the woods, and the canals which girdled it round; and it was protected by a large Spanish force in observation not far from Ypres. Turenne crossed the inundation let loose by the garrison, threw lines of investment round the fortress, and blocked up the approaches along the coast. An English fleet closed the port from the sea, and 5,000 of the renowned Ironsides were disembarked to support the French. These operations, rapid in the extreme for the age, surprised and disconcerted the Spanish chiefs, and they hastily advanced to relieve Dunkirk with an army inferior in force to the enemy, and not possessing a single gun. Turenne broke up from his lines to attack; his left, the English contingent, rested on the sea, covered by the batteries of the English squadron; his centre and right formed a semi-circle, extending to the great canal of Furnes; and as his troops advanced, Condé, it is said, exclaimed to the young Duke of Gloucester that “all was lost.” The battle was almost at once decided; Condé, on the Spanish left, did indeed wonders; but the Ironsides, backed by the fire of the fleet—they were praised by Turenne in the highest terms—annihilated the Spanish right in one charge, and the whole Spanish army, deprived of artillery, lost heart and became a mere mass of fugitives. The place fell, and was handed over to England. Turenne, breaking up from his camps, took Bergues and Gravelines, and overran the country, and he only stopped his victorious march at Oudenarde, Spanish Flanders lying as it were at his feet. Napoleon, however, contends that the marshal ought to have done more, and pushed on to Brussels, success which would have brought the war to an end; and this may be an instance, perhaps, in which Turenne’s powerful, but somewhat slow intellect erred on the side of too prudent caution. Yet we must bear in mind that the strategy of the seventeenth could not be that of the nineteenth century. Turenne certainly contemplated this very step, but declared that it was not practicable; and, as it was, the campaign was a splendid triumph which soon brought about the Peace of the Pyrenees.

[26]

During the next twelve years France enjoyed repose, broken only by a brief contest with Spain, caused by the claims of Louis XIV. on the Low Countries in right of his consort. Turenne commanded the royal army, captured Lille, and overran Flanders; but it is unnecessary to dwell on these easy triumphs. The marshal was now the first subject of France and admittedly the first soldier of Europe; and he played a part of no small importance in the able French diplomacy of the time. He gave much attention also to civil affairs, was a disciple of the renowned Colbert, drew up reports on the condition of France which showed real insight and marked sagacity, and proved that he possessed administrative powers of the highest order in provincial government. Like nearly all the highest noblesse of France, he renounced the Calvinist creed of his fathers—the will of the King was supreme in this—but, like the illustrious Villars at a later day he condemned the wrongs already done to the Huguenots, and ventured to utter a weighty protest. His great work, however, at this period, was the reorganization of the military power of France; and though Louvois had a large share in this, Turenne is perhaps entitled to the chief merit. His reforms were thorough and yet practical; he did not change everything, and break with the past; but he so improved what he found existing as to bring it to a high state of excellence, and the French army, in his constructive hands, became a mighty instrument of war.

Turenne’s method was to leave the army still largely in the hands of the noblesse, and to allow it to retain a half feudal character; but he not the less made it the force of the Crown, the disciplined array of an all-powerful monarchy; and he so transformed its institutions and spirit, and increased its strength, as to make it by far the most formidable organization for war in Europe. The noblesse were allowed to retain their charges, and to raise their levies as in former days; but they were subjected to the strictest inspection; incapable officers were summarily dismissed, and “men in buckram” and false returns were no longer permitted to exist. While the feudal militia still remained, every inducement was offered to encourage the men to enter the ranks of the regular troops; the temporary disbanding of regiments ceased;[27] and select corps—need we name the Maison du Roi, the brilliant victors on many a field?—were carefully formed, and inspired the army as a whole with their gallant and martial spirit. These were great reforms if they stood alone, but the process of improvement went much further. The hierarchy of the service had its rules changed; the general-in-chief was made supreme in everything; the three arms and their chiefs were placed under his immediate control in all respects, and discipline and subordination to one head were thus secured for the first time. Unity of command caused unity in lower spheres; the comparatively loose formations, indeed, of battalions and squadrons were not changed, but every regiment was clad in uniform; and care was taken that all weapons should be constructed and fashioned on the same patterns. Strenuous efforts, again, which reveal the strategist, were made to accelerate movements in war; the arrays of trains and carriages were greatly increased; the system of magazines, of depôts of food, and of field hospitals was immensely improved, and the mechanism of the army attained a degree of perfection never witnessed before. Yet the greatest change of all remains to be noticed—a change, Napoleon remarks, which made this period a new era in war. A master of his art, Turenne had perceived that infantry, hitherto kept in the background, was naturally the most important of the arms; it could accomplish more in his wars of marches, even in that age, than the more prized cavalry; and Turenne trebled its force in the French service, reducing horse to much less significance, though cavalry still, no doubt, retained its superiority in the shock of battle. As for artillery, Turenne went with the age; the proportion of guns, though comparatively small as regards the other arms for modern times, was gradually but distinctly increased.

Through these immense reforms, the army of France became, for many years, the terror of Europe; and, except that the changes wrought in formations by the discovery of the bayonet were as yet unknown, it had acquired a really modern aspect. An opportunity arose, in 1672, to prove this tremendous instrument of war. Louis XIV. invaded the Dutch Republic; the French army and[28] that of his allies exceeded 130,000 men, a force never seen since the fall of Rome; and while Turenne and Condé, now restored to France, advanced along the Sambre and crossed the Meuse, the allied contingent under Luxemburg moved down the Rhine by Mayence and Cologne. True to his strategic genius, Turenne insisted, against the advice even of the audacious Condé, on “masking” Maastricht and pressing forward; the operations of the invading host were marked by a celerity hitherto unknown, and in less than two months the hostile armies had crossed the Rhine near the Waal, had attained the Yssel and had moved into the heart of the Seven Provinces. When the victorious French had approached Amsterdam, Condé, always great on a field of manœuvre, entreated the King to seize the dykes, which formed the last defence of the capital of the States; and, had this been done, the fortunes of Europe might have taken a wholly different turn. The golden occasion was, however, lost; time and men were wasted in taking fortresses; and William of Orange, a sickly youth, then for the first time seen on the stage of history, saved the Commonwealth by cutting the dykes and letting loose floods which made Amsterdam an island in the midst of a submerged country, and effectually baffled the French commanders.

THEATRE OF WAR

IN

THE LOW COUNTRIES

This bad generalship was due to Louvois, and, it is said, was inspired by the King, never capable in operations in the field; but Turenne must, at least, have assented, and Napoleon severely condemns the Marshal for giving his sanction to unwise counsels which he scarcely could have approved in his heart. This possibly may be another instance in which Turenne was somewhat slow and too cautious; but probably he shrank from opposing the will of a sovereign, then almost an idol, and a minister already hostile to him; and it is scarcely to be supposed that a chief of his powers, in full possession of the state of affairs, would have committed a palpable strategic error. Be this as it may, he soon had an occasion to exhibit once more his great capacity. The invasion of the States, and the success of Louis, had alarmed Europe and aroused Germany; Austria and Prussia joined hands for the first time in war; and two German armies of superior strength were marched [29]towards the Rhine and threatened Alsace. Louis abandoned Holland and his rapid conquests; Condé was despatched to defend the Rhine, and Turenne was placed at the head of an army intended to confront the Germans on the Main. The Marshal had soon seen through the projects of his foes; he judged rightly that their real purpose was to unite on the Meuse with William of Orange, not to venture alone to enter Alsace, and he took his course with characteristic skill. Moving into the region around Trèves, he established himself in the valley of the Moselle, and when the Germans, as he expected, sought to cross the Palatinate from Mayence, he successfully kept them for weeks at bay, held back the army of the States on the Meuse, and completely frustrated the intended junction. This fine strategy probably saved France from an invasion upon her weakest frontier.

Louvois had now openly broken with Turenne; the King, irritated at the reverse in Holland, took part with the imperious minister, underrating the Marshal’s last achievement, and Turenne found little favour at court. It was impossible, however, to question his genius; he directed the general plan of the campaign of 1673, and he held supreme command on the German frontier. As the Austrians and Prussians fell back from the Moselle, they began to diverge towards the Elbe and the Danube; Turenne saw his advantage, and crossed the Rhine, and venturing on a winter campaign, despite the remonstrances even of the King, he advanced to the Weser, defeated the Prussians, and drove the Austrians far beyond the Main. Prussia abandoned the Coalition for a time, but the Emperor refused to give up the contest, and Turenne, for the first and last time, was out-generalled on the theatre of war by an antagonist not unworthy of him. Montecuculi, at the head of an Imperial army, had advanced into the Franconian lowlands, eluding Turenne, who was on the Tauber; he gained over one of the prince bishops, made a forced march and got over the Main, and then having made a feint on Alsace, he embarked with his troops upon the Rhine, effected his junction with William of Orange at Bonn, and quickly reduced that important fortress. This, Napoleon has said, is “the darkest[30] cloud on the reputation of this great captain;” but the glory of Turenne was not long in eclipse; and he surpassed himself in the campaign of 1674, the most striking instance, perhaps, of his powers. The success of Montecuculi had again roused Germany; Prussia and the Lesser States took part with the Emperor, and France was threatened with a more formidable League than she had ever encountered before. Turenne directed operations once more; with admirable wisdom he neglected the North, and urged the King to invade Franche Comté, an enterprise crowned with complete success; and he took again his station on the Rhine, watching the masses of foes collected against him.

Every movement he made in the contest that followed is a masterpiece of a great strategist. Turenne, crossing the Rhine, advanced to the Neckar, threw himself between the armies converging against him; and, having routed the Austrians near Sinsheim, turned boldly against the Northern Germans, marching from the Elbe and the plains of Brandenburg. To gain time and to check their progress, he ravaged the Palatinate with unflinching sternness; and though history condemns the act, and Turenne only once adopted this course, it was justified by the laws of war of the age—nay, by those of a much later period. The Germans had reached Mayence by the end of August, and before long had entered Alsace; the Imperial army was close at hand, and it was the purpose of the Imperial chiefs to invade France with the combined forces, when the Prussian contingent had come into line. Turenne saw the danger, and did not hesitate; with an energy worthy of the youthful Bonaparte, he fell on his foes before their junction, and he defeated them in a fierce fight at Entzheim, a day memorable if it were for this only—that Marlborough served on the marshal’s staff, and received the thanks of his chief for his conduct. This reverse, however, only checked the enemy; the Great Elector brought up his army. Turenne was obliged to fall back to the Vosges, and a huge wave of Teutonic conquest seemed about to overflow the plains of Champagne. Had the Germans pushed on they might have reached Paris, where confusion and terror already reigned; but they paused at the decisive moment. They seem to[31] have dreaded the strokes of Turenne, who had skilfully taken a position on their flank, and they methodically settled in winter quarters in Alsace, having let a grand opportunity pass. The subsequent operations of their great adversary, in conception at least, were of the highest order. Deceiving his enemy and scorning the hardships of winter among the Alsatian hills, Turenne feigned to retreat into Lorraine; he then counter-marched with remarkable quickness, defiled behind the Vosges with a devoted army which appreciated the admirable skill of its chief, and, having screened the movement by the mountain barrier, broke in through the gap of Belfort on the astounded Germans, and surprised them completely divided and scattered. The effects of this masterly stroke were immense; the Great Elector was routed at Turckheim, Turenne pressed forward and threatened Strasbourg, and the horde of invaders, baffled and humbled, were only too glad to get across the Rhine.

The movement behind the Vosges of Turenne which surprised the Germans and caused their defeat has a certain resemblance, it will be perceived, to the march of Napoleon, screened by the Alps, which after Marengo gave him Italy. Turenne, however, the reader will note, fell on his enemy, when he had reached him, in front, and his triumph though great was not overwhelming; Napoleon descended on the rear of Mélas, and, though he ran many risks, he completely conquered. Turenne, the Emperor insists, would have achieved more had he crossed the Vosges in the middle of the chain, and struck the flank and rear of the Germans; in that event, the invaders, perhaps, would have never been able to attain the Rhine. This criticism is, in theory, perfect; but though Napoleon, in the place of Turenne, would probably have played the more daring game, the Vosges in those days were most difficult to pass; the operation would have been very hazardous, and the two movements, in fact, illustrate the difference between the natures of the two men.

I have reached the last campaign of Turenne, a long game of manœuvre between two great strategists, in which the marshal perished on the very edge of victory. The League[32] against France, though shattered, still held together; and faulty generalship having been the cause of the signal discomfiture of 1674, Montecuculi was sent, in 1675, to cope with Turenne, still upon the Rhine. The Imperial commander, having threatened Philipsburg, crossed the river near Spires and invaded Alsace; but Turenne, instead of attacking his foe, crossed the river near Strasbourg, and, reaching Wilstedt, struck at the communications of the hostile army; and this forced his adversary to recross the Rhine. Turenne, having gained this strategic advantage, and carried the war into German territory, took a position between Strasbourg and Ottenheim, the place where he had bridged the Rhine; but Ottenheim is at some distance from Strasbourg, and the French army was very much divided. Montecuculi approached the Marshal’s camps, and missed a grand opportunity to strike, which, Napoleon remarks, Condé would have seized; Turenne, perceiving the danger, raised his bridge, placed it near Strasbourg, and drew in his forces; and Montecuculi, again baffled, descended the Rhine and occupied Freistett, his object being to cross the Rhine at that point by means of a bridge, to be sent down from Strasbourg—then, it will be borne in mind, an Imperial city—and his ultimate end being to re-enter Alsace. Turenne, however, barred the course of the Rhine, by redoubts and batteries carefully placed; and having thus prevented the passage of the bridge, he, for the third time, out-manœuvred his enemy and kept him bound with his army to Germany. The antagonists now held their camps for some months, each watching the other, and seeking a chance; but Turenne was the first to move. He crossed the Rench by an undefended ford; and this movement compelled his enemy to retreat, for it threatened his communications, and almost reached his flank. Montecuculi, utterly foiled and out-generalled, abandoned at once the valley of the Rhine, and made for the defiles of Würtemberg. Turenne, hanging on his foe, pursued; and, by the close of July, he had attained the Sassbach, assured that he would triumph in a great and decisive battle. Fate, however, withheld from Turenne a victory justly earned by his most able strategy. He was struck[33] down by a shot from a hostile battery, and Montecuculi escaped from the toils which had been admirably laid around him. The Imperial chief, indeed—a remarkable man, and in this campaign he was suffering from disease—when apprised of the death of his renowned adversary, at once boldly resumed the offensive. The French army, deprived of the genius which had led it to victory for many years, was soon in full retreat on the Rhine; and having fallen into the hands of incapable chiefs, it was nearly involved in a crushing disaster. The history of war has few more striking instances of what a commander is to his troops than the reverses which, after the fall of Turenne, followed the course of his steady success before it; and the passionate cry of his defeated soldiery, to the worthless men who stood in his place, “Give us Magpie”—the warrior’s charger—“to lead us!” is only an exaggeration of a substantial truth. Montecuculi’s eulogy on Turenne is well-known; but the offensive return which he made with confidence and victoriously after his great rival’s death is a more expressive and a finer epitaph.

Sorrowing Ilium mourned her mighty shade; the remains of Turenne were borne to St. Denis, and laid in the tombs of the Kings of France, an honour never again conferred on a subject. They were spared even by the Jacobin hands which violated the royal abodes of death in the madness of Paris in 1793; and they now fitly rest beside those of Napoleon. A word on the place of this great man among the masters of the noblest of arts. The peculiar gifts of Turenne were a far-sighted and calm intelligence, sagacity of the finest kind, and admirable constancy and force of character, and these made him one of the first of generals, though he did not possess, in the highest degree, the dazzling imagination, the power of thought and of calculation, and the astonishing energy which distinguish Napoleon and, perhaps, Hannibal. These qualities made him a consummate strategist, few chiefs have ever moved on a theatre of war with the perfect skill and success of Turenne; few have known how to make grand manœuvres with as certain results, and with equal brilliancy; and his great wars of marches, replacing sieges, were an inspiration[34] of most striking genius. As for special illustration of his strategic powers, Turenne has been surpassed by Napoleon alone in the art of reaching the communications of a foe, and of operating between separate hostile masses; and he was safer than Napoleon in these efforts, though he did not accomplish such marvels of war. Considering the state of the art in his time, no chief perhaps has ever achieved more than Turenne by scientific movements; he triumphed in several campaigns by mere marches without fighting a single battle, and yet his success was complete and decisive, as was specially seen in 1646 and 1675. In fact, strategy made little progress for many years after this great captain; and yet Turenne did not quite attain the highest rank among modern strategists, for his intellect was somewhat wanting in quickness, and his nature in what is called the sacred fire; he let grand opportunities slip, and in three great instances, at least, he did not do what probably might have been accomplished by him.

These defects—and genius is never perfect—made him a tactician of the second order only; he had not Condé’s inspired thought on the field; and for a commander of extraordinary gifts, he suffered defeat in many instances. Yet the decision and firmness which were among his qualities stood him in good stead, even in the conduct of troops; no general has ever known better how to make a bold stand, and to impose on an enemy; and it was one of his special characteristics that he could overcome defeat, and that he was most formidable after a reverse of fortune. For the rest, Turenne, like most great captains, had administrative powers of the highest order; he, usually, even in his long marches, contrived to have his army in good condition; he remodelled the military organisation of France, and made it by far the best in Europe; and, as an administrator, he had this distinctive merit—that he was in advance of the ideas of his time. I must add a word on the relations between this illustrious chief and the armies he led. Turenne had a truly chivalrous nature; he was singularly considerate to his lieutenants, and though he could be stern and severe when needful, he made the largest allowance for mere[35] errors, and never blamed others for shortcomings of his own. No general has ever had more devoted officers; and this magnanimous character was admired and recognized by every chief who was opposed to him, by Leopold, Montecuculi, and even the arrogant Condé. As for his troops, Turenne was most chary of their blood, resembling Wellington in this respect; and, like Wellington too—a regimental officer, versed in the details of professional work—Turenne knew their wants and gave much attention to them. As has always happened with real chiefs, Turenne fashioned his soldiers to his own nature; they were not rapid and vehement in in his hands as they were in those of Condé and Villars; but he made them steady, enduring, bold, but tenacious; and their phrase, “our father,” shows how he was beloved by them. Except for one unhappy lapse, the career of Turenne does “honour to humanity,” to quote the words of his ablest adversary and yet sympathetic friend.

[36]