Title: Sea, spray and spindrift

Naval yarns

Author: H. Taprell Dorling

Illustrator: N. Sotheby Pitcher

W. Edward Wigfull

Release date: November 18, 2025 [eBook #77262]

Language: English

Original publication: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1917

Credits: Chuck Greif, hekula03 and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

CONTENTS.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

FOOTNOTES.

SEA, SPRAY AND SPINDRIFT

WORKS BY “TAFFRAIL”

CARRY ON!

Naval Sketches and Stories.

1/- net, PEARSON.

STAND BY!

Naval Sketches and Stories.

1/- net, PEARSON.

MINOR OPERATIONS

Naval Stories.

1/- net, PEARSON.

OFF SHORE

Naval Sketches and Stories.

1/- net, PEARSON.

PINCHER MARTIN, O.D.

A Story of the Navy.

(CHAMBERS.)

NAVAL YARNS

BY

“TAFFRAIL”

AUTHOR OF

“CARRY ON!” “PINCHER MARTIN, O.D.”

ETC., ETC.

With Eight Full-page Illustrations by

W. E. Wigfull & H. Sotheby Pitcher.

Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company

London: C. Arthur Pearson Ltd.

1917

Printed in England

These stories were not originally written with a view to their ultimate reappearance in book form, and most of them were written some while ago. “Tubby’s Dhow” was first published in Herbert Strang’s Annual for Boys; “The Stranding of the Hoi-Hau,” “The Salvage of the Cashmere” and “The Luck of the Tavy,” in the Scout; “The Gunner’s Luck,” in the Weekly Telegraph; “The Inner Patrol,” in the Royal Magazine; “Horatio Nelson Chivers” and “The Escape of the Speedwell,” in the British Boys’ Annual (Messrs. Cassell & Co., Ltd.), and “The Gun-runners,” in the St. George’s Magazine. I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness to the respective Editors who have so kindly allowed me to republish my work in book form.

It is needless to remark that all my characters are fictitious.

“Taffrail.”

1917.

“Oh, blow this Arabic!” exclaimed the midshipman petulantly, shutting up the phrase book on the table before him with a bang and leaning back to stretch himself.

“What’s the matter now, Tubby?” asked a small officer called Travers, who, by reason of his rather shrill voice, always went by the name of “Squeaker.”

“Tubby,” otherwise Midshipman Arthur Geoffrey Plantagenet, Royal Navy, mopped his face for a minute before replying. It must be admitted that he fully deserved his nickname, for in appearance he was short and very rotund, and was the proud possessor of a bright red face, a crop of freckles, and a shock of sandy hair. His tout ensemble was not prepossessing, but his even white teeth and blue eyes saved him from being absolutely ugly, particularly when he laughed.

“What was that you said, Squeaker?” he said at last.

“I asked you what was the matter.”

“It’s this heat,” Tubby complained. “One can’t do any work while it’s like this!”

Their ship—H.M.S. Clytia, light cruiser—was in the Gulf of Oman, and it certainly was over-poweringly hot; for the pitch bubbled in the seams on deck, while the awnings overhead seemed to collect rather than mitigate the heat from the blazing sun above.

“But why d’you want to learn Arabic?” asked Travers after another pause.

“Because I want to know the language, silly!” retorted Plantagenet. “I know all you fellows jeered at me when I took it up, but though I’ve only been at it six months I know quite enough to make myself understood ashore.”

“But—— ” the other was about to protest.

“Be quiet, you two!” growled a drowsy sub-lieutenant from a deck chair. “Can’t you let a fellow get to sleep?”

It was a “make and mend” afternoon, which in other words meant that all the midshipmen had a half-holiday. It followed, therefore, since the ship was at sea and they could not get ashore, that the greater number of them followed the usual custom of the Service and spent it in sleep. The small curtained-off inclosure on the upper deck, serving for the time being as the gunroom, since the heat down below was quite unendurable, was full of young officers stretched out on forms and deck chairs in various stages of drowsiness and deshabille. Tubby and Travers, in fact, the latter of whom had been industriously writing up his journal, were the only two members of the little community who were awake.

“I say, Squeaker,” whispered the former, glancing round to see if the sub-lieutenant was asleep, “you know we’re anchoring off one of the villages at daylight to-morrow?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I heard the skipper telling the commander that all the officers who could be spared could go ashore for a run, snotties as well. It ’ud be rather a good idea if you and I took our guns. We might get Molyneux to come too,” he added, referring to one of the other midshipmen.

“I’m all for it,” agreed Squeaker; “but is there anything to shoot?”

“I dare say. I had a look at the chart this afternoon, and about five miles along the coast from where we’ll anchor there’s some cover a short way inland. It’s not far from a village. I vote we go in that direction.”

“All right,” said Travers; “but d’you think it’ll be quite safe?”

“Of course, it will; why shouldn’t it be?”

“I’ve heard that all these villagers are in league with the gun-runners we’re trying to catch,” explained the other. “It would be rather a bad look-out if we got caught.”

“Oh, that’s all rot,” put in Tubby. “They won’t hurt us. You’ll come, I suppose?”

“You bet.”

“All right. That’s fixed up. I know Molyneux’ll be keen.”

To understand the exact nature of the operations in which the Clytia was taking part, it is necessary to refer to the map. The native dhows carrying arms and ammunition usually left different places on the Oman and Pirate coasts of Arabia, their{12} destinations being the small bays and creeks between Lingah and Charbar on the Mekran coast. On being disembarked, the weapons were loaded on camels and taken inland to Afghanistan, where, subsequently, they were used by the tribesmen against the British forces on the northern frontier of India.

To guard against this gun-running, so prejudicial to British interests, the Oman and Pirate coasts and the Mekran coast of Persia were being patrolled by cruisers, while further inshore a ceaseless watch was maintained by the boats of the Squadron.

For two weeks the Clytia had been cruising slowly up and down between Charbar and Jask, this being the portion of coast she had been detailed to watch, while her four largest sailing boats, carrying Maxim guns, and with their crews fully armed, had been sent away in charge of her lieutenants. They were each responsible for about thirty miles of coast, and had orders to search all the inner anchorages and small bays, and to overhaul and examine all the native craft they came across.

Each week the ship met her small fry at previously determined rendezvous, and on these occasions she received their reports, replenished their stock of water and food, and, if necessary, relieved the crews. But though the watch had been carried on with tireless vigilance, nothing had happened and no dhows with arms on board had been seized.

The men were beginning to weary of the ceaseless monotony. There was no excitement to keep them going, and for a lieutenant, several seamen,{13} a signalman and a native interpreter to be herded together in a small undecked boat about 28 feet long, was not altogether comfortable. They had to live, eat and sleep as best they could, and though sometimes they did get ashore on a barren stretch of sand, where they would amuse themselves in the cool of the evening by kicking a football about, they were getting sick of it. The weather, too, was not always fine, for at times the boats would be compelled to anchor off the coast to ride out a strong “Shamal,” or north-westerly gale. This was always a most trying experience, but the only other alternative was to land up some creek, and this, as a rule, was too hazardous to be attempted, for the inhabitants were generally hostile, and would not hesitate to attack if they had the least chance of success.

Tubby’s proposed expedition, therefore, was not quite so safe as he imagined.

Early the next morning the Clytia anchored off a small village on the coast some distance to the eastward of Jask. She was to remain till the following morning, and all the officers and men who could be spared from duty, including the midshipmen, were sent ashore to stretch their legs.

Directly they landed, Tubby, Travers and Molyneux set off to the eastward along the coast. They were burdened with their guns, cartridge bags and water-bottles, and on account of the great heat soon found progress very trying. The{14} route led them across large tracts of dry powdery sand, into which they sank up to their ankles, through occasional patches of thick scrub, which were difficult to negotiate, and by the time they neared their destination they were all three tired out, hot, and very thirsty, in spite of the copious draughts of water they had swallowed on the way. There was not a tree in the place under which they could sit for protection from the sun, and they all wanted rest badly.

“What d’you think we’d better do, Tubby?” asked Molyneux, stopping to lace up his boot. “I feel like a spell in the shade, but there’s not a tree in sight anywhere.”

“I’m tired of marching about like this,” agreed the young officer addressed. “What do you think about it, Squeaker?”

The youth looked round for some moments without replying. “I think,” he remarked at length, “we might go on to that village and see if they’ll let us sit down in one of their houses for a bit. The place’ll smell like fury, but it’s either that or no spell.” He pointed to the small collection of mud hovels about half a mile ahead.

“Um, yes,” agreed Tubby. “I suppose that’s what we’d better do. Come on!”

They tramped forward, but had not advanced more than two hundred yards when they saw a man advancing along the beach towards them. He was clad in a dirty white burnous and, coming forward, raised his hand in a sort of military salute, and showed his teeth in a grin.

“You shoot?” he asked in English.

“Yes,” answered Tubby.

“I good guide, tell where you get plenty big bird,” said the new-comer, tapping himself on the chest and then pointing inland.

“We want to sit down for a bit,” explained Molyneux. “Have you a house in that village?”

“I got good house; you come see,” said the man, pointing over his shoulder. “My name Takadin. Engleesh call me Jack Robinson. Very good name. I been Bombay, Aden, and plenty big town. I know plenty Engleeshman. I very good man.”

“Where did you learn English?” Tubby asked.

“I sailor B.1 boat, long time,” answered the Arab.

“What d’you think?” Tubby asked his companions. “Shall we go with him?”

“I vote we do,” they both said at once, for they were very tired; and led by their new friend, they were soon in what was evidently the main street of the village.

It was really nothing more nor less than a narrow passage-way between two rows of very tumbledown-looking one-storeyed mud hovels, and the advent of Europeans was evidently regarded by the inhabitants as something quite out of the ordinary. Half-a-dozen mangy-looking curs sniffed suspiciously at their heels, while tribes of small brown children, clad in the sketchiest of garments, gazed at the foreigners open-mouthed with amazement. Numbers of men, dressed in dirty white robes, eyed them with evil, scowling faces, and it was quite obvious that whatever feelings for the British Mr. “Jack Robinson” had, these Arabs were none too friendly. There was something insolent in the way they laughed, and{16} in their glowering, sullen glances, and one or two of them, Tubby noticed, spat on the ground after the little procession had passed.

The boy felt nervous, for there was no mistaking the hostility of the natives; but it was too late to draw back now, nor, for the time being, could he impart his fears to his companions. He was thinking how sorry he was not to have taken the advice of people who knew better than he did, when their guide suddenly stopped before a low doorway.

“This my house!” he exclaimed with an air of pride. “Very good house!”

The midshipmen did not think much of it, for it was distinctly on its last legs, but followed him inside. The room they found themselves in contained little in the way of furniture, but asking them to sit down on a kind of couch running along one side of the wall, the Arab pushed aside a mat hanging across the doorway leading into the inner room, and disappeared inside. Judging from the shrill cackle that went on as soon as he entered, the ladies of the establishment were within, but the noise was rather welcome, for it gave Tubby a chance of talking to his friends without being overheard.

“I say, Molyneux,” he said in a whisper, “I vote we clear out of this village as soon as we can. Did you see how those fellows looked at us as we came along?”

“Yes, I did,” answered the other rather nervously. “D’you think they mean any harm, though?”

“No, I don’t think so; the ship’s too close. I wish we hadn’t come, for all that. Whatever{17} you do, keep your guns loaded, and don’t let go of them.” He noiselessly slipped a couple of cartridges into the breech of his weapon.

“Look out!” hissed Travers. “The Arab’s coming back!”

“Mum’s the word then,” whispered Tubby; “but we’ll clear out as soon as we can, and for goodness’ sake don’t let’s get separated!”

There was no time for further conversation, for just at that moment the mat was pushed aside and Takadin came in with a tray, on which there were several small bowls filled with dates and a few nasty-looking native cakes.

“Please to eat,” he said with a deprecatory smile. “I poor man; Engleesh my friend.”

The food did not look very appetising, but now it had been brought the boys could not very well refuse to eat for fear of being thought uncivil, and selecting some dates, as being the most harmless, began to nibble at them. The sandwiches out of their haversacks, however, were far more to their liking, and giving one or two to Takadin in return for his hospitality, they had soon made a satisfactory meal, which they washed down with water from their bottles. Having eaten, Tubby felt more cheerful, and was beginning to forget his fears, when a figure appeared in the doorway leading to the street outside.

Their host instantly rose to his feet and made a low obeisance to the new-comer, a tall, fine-looking, white-bearded Arab clad in the inevitable burnous. He was evidently of better class than the other men they had seen, and judging from Takadin’s behaviour that he was a notability{18} of some kind, the boys stood up and bowed. Their salutation was returned.

“Peace be unto thee, my son,” said the new arrival, addressing Takadin.

He spoke in Arabic, but Tubby had little difficulty in understanding his words.

“Peace be unto thee, my father,” returned their host, bowing again.

“What do these dogs of infidels under thy roof?” demanded the Sheikh, for such he was, and casting a piercing glance from his black eyes at the three boys.

“They come, my father, from the war vessel anchored off the coast. They came seeking shelter from the sun.”

“Dogs!” hissed the old man. “Spawn of the devil! May their eyes be blasted with the fire which never languishes! By the Beard of the Prophet, my son, thou didst a good stroke of business in sheltering them!”

Tubby gave a start of surprise which nearly betrayed him.

“But I came, O Takadin,” he went on to say, “to have a word with thee. ’Tis only for thine ear.”

“Speak on, my father; my women are out of hearing, and the unbelievers have no knowledge of our tongue.”

Tubby, half beside himself with apprehension and excitement, listened intently, trying hard not to let his face betray the fact that he understood most of what was being said. But the Sheikh was talking again.

“The dhow from Oman with the rifles my son, when does she arrive?”

“Seven days from now, my father, at the spot close by the watch tower. The camels will be ready, thy servant has seen to that, and the nakhuda[A] has orders to land them four hours after the setting of the sun.”

“It is well. I like not these dogs of hillmen in our midst. They strip us bare like a flock of locusts. I like them not, they and their camels. I shall give thanks to Allah when they depart.”

“Even so, my father,” agreed Takadin. “They are carrion fit only for vultures.”

“Speak no word to any man of what we have said,” ordered the Sheikh.

“Thy servant’s lips are sealed, my father.”

“But these unbelievers, my son, who have fallen into our hands. A ransom will not come amiss.”

“Their war vessel is very close, my father, and our village will surely be laid in ruins if they should be harmed.”

The Sheikh made a gesture of annoyance. “Thou art my servant, O Takadin!” he exclaimed angrily. “What I have said I have said!”

“Even so, my father,” said the other, with a cringing bow.

“’Tis well. Delay them here till I return; I go to seek my men. The infidels shall be detained. By Allah! Would that I had the opportunity to sear their flesh with red-hot pincers! To make them food for the vultures of the desert!” With which terrible wish the Sheikh disappeared.

For a second or two Tubby was absolutely nonplussed by what he had heard. Takadin would certainly carry out his orders if he could, and in a{20} minute or two the chief would probably return with his men. The boy racked his brains for a way out of the difficulty. To escape through the village was an obvious impossibility, for they would have to run the gauntlet of all the inhabitants. Then the boy’s memory came to his assistance. He suddenly recollected the topography of the place, and how, when walking down the street, he had seen a little strip of blue sea at the end of it. He remembered, also, that when they were approaching the village he had noticed a low wooden pier with a boat made fast alongside it. Here was a solution. The house they were in could not be more than two hundred yards from the water. They must make a dash for the boat. All these thoughts flashed through his mind, but what had to be done must be done at once.

“I say, Molyneux!” he said in an excited whisper, “be ready to make a dash as soon as I do!”

“Whatever for?” asked the other, “what’s all the——?”

“I can’t tell you now,” hissed Tubby, “but it’s jolly serious. Be ready to make a bolt for the sea; you too, Travers.”

The other two looked at each other in amazement, for they could not conceive what had happened, but they both followed Tubby’s example when he stood up with his gun.

Takadin noticed what was going on. “You no go,” he said with a treacherous smile, “you stay my house. I very—— ”

But he got no further, for Tubby, making a sudden spring, hit him full on the point of the jaw.

The Arab was quite unprepared for the sudden attack and staggered backwards, and another severe punch laid him flat on the ground.

“Run!” yelled the assailant to his companions, “run for all you’re worth!”

He dashed out of the door followed by the others, and as he emerged he caught a hurried glimpse of the Sheikh and half-a-dozen men coming down the street from the right. The latter shouted and promptly started off in pursuit, but the boys made for the sea at full pelt, the din behind making them run all the faster.

Every second Tubby expected to hear a bullet whistling by his ears, but, though he did not know it till later, the Arabs carried no firearms. Still, the situation was quite bad enough, for though nobody tried to intercept them in their flight, they could hear their pursuers padding along close behind.

On and on they flew until, after what seemed an eternity, they reached the end of the lane and saw the open sea before them, and the wooden jetty, with the boat still made fast alongside it, a short distance to the left. Tubby’s breath came in great gasps, his head throbbed, and he felt as if his heart would burst, but he tore on with the others close behind.

By the time they reached the shore end of the pier, however, the leading Arab, who was some distance ahead of his friends, was barely three feet behind Molyneux, the last of the three. The man suddenly nerved himself for a supreme effort, and springing forward seized the boy by the shoulder. Molyneux promptly swerved in his stride, but tripped, and before he quite knew what had{22} happened had fallen headlong on his face. The Arab, unable to stop himself, still came on, and catching his foot in the prostrate boy’s body, gave a loud yell and disappeared over the edge of the pier into the water.

Tubby, hearing the commotion, glanced round to see what had happened, and, stopping himself suddenly, turned round and dashed back to his fallen friend. Travers also checked himself, not knowing what to do.

“Get into the boat!” Tubby yelled to him, noticing his indecision. “Get in and cast her off!”

The small midshipman clambered on board and began to fumble with the painter, while Tubby put back the safety catch of his hammerless gun and held it ready. The other Arabs, meanwhile, had just reached the shore end of the pier, and to the boy’s relief he suddenly noticed that none of them carried firearms.

“If you come any further I’ll fire!” he shouted breathlessly in their own language. “Get up, Molyneux!” he added in English. “Get down into the boat and cover ’em with your gun!”

Molyneux sprang to his feet and joined Travers in the boat.

The Arabs had halted when they heard Tubby’s hail, and were now talking excitedly among themselves, but then one of them drew a long evil-looking knife and made a step forward.

Tubby promptly covered him. “Drop that or I fire!” he commanded. To his intense surprise the man obeyed his peremptory order.

“Thou son of a pig!” bellowed the enraged Sheikh. “Wouldst thou obey the command of an{23} infidel? Seize him, I say! Seize him!” But the men did not like the look of the gun muzzles confronting them, and still hung back.

“Come on!” shouted Travers at length, “I’ve cast her off!”

“Have you got ’em covered?” asked Tubby.

“Yes,” cried Molyneux, squinting along his weapon.

Tubby walked backwards until he came to where the boat lay, and then jumped on board.

“By Allah! Thou craven sons of pigs!” yelled the Sheikh. “They would steal the boat! At them!”

The men came panting along the low jetty, but it was too late, for by the time they reached the end the boat was a good half-dozen yards away. They could do nothing; there was no other boat in which they could give chase, and they had to content themselves by throwing strange curses at the three boys who had outwitted them.

“By George!” remarked Tubby breathlessly, tugging at one of the clumsy oars, “that was a jolly narrow squeak! I thought they had us!”

“I regarded it as a dead cert!” said Molyneux gravely.

A gentle south-westerly breeze had sprung up, and five minutes later, as the discomfited Arabs were leaving the pier, the sail had been hoisted, and the boat was bowling along the coast towards the spot where the adventurers had landed.

As soon as he recovered his breath, Tubby told his companions of the conversation he had overheard, and their eyes opened wider and wider with astonishment as he went on.

“Well, what d’you propose to do?” queried Molyneux, when at length the tale was told.

“Tell the commander,” said Tubby. “But I say, you fellows, not a word of this to anyone else!”

“Right O!” they both agreed.

There is no necessity to describe the homeward journey, or how, after sailing about three miles along the coast, they landed, left the boat on the beach, and finished the journey on foot.

But that evening Tubby summoned up his courage, and in an interview with the commander told him all he had heard. But that officer, though he promised to inform the captain, did not realise how much Arabic the boy really knew, and at any rate it was quite obvious that he did not believe his story.

Three mornings later, when the Clytia had resumed her weary patrol of the coast, a messenger suddenly burst into the place where Tubby was endeavouring to work out a sight under the direction of the naval instructor.

“Beg pardon, sir,” said the man, “but is Mr. Plantagenet ’ere?”

“Here I am,” said that young officer. “What is it?”

“Please, sir, th’ capten wants you on th’ bridge at once.”

Tubby dashed off, and on reaching the bridge went up to the captain and saluted. “You sent for me, sir?” he asked.

“Yes, Mr. Plantagenet. The commander tells me you know Arabic. Is that so?”

“I know a little, sir,” Tubby modestly answered.

“Enough to understand conversations when you hear ’em, eh?” asked the captain with a twinkle in his eye.

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, be ready to leave the ship in ten minutes’ time. The native interpreter in the third cutter,” he waved his hand to where the boat they had just met lay alongside, “is down with fever, and you’ll have to go instead of him. I do not, Mr. Plantagenet, approve of your going visiting native villages when you go ashore, you must understand, but I suppose you remember whereabouts this one was?”

“Perfectly, sir,” said Tubby.

“So much the better, then. You may perhaps be able to bring back that dhow you heard the men talking about. Hurry up now, collect what you want, and then report yourself to Mr. Thompson, who is in charge of the boat.”

The midshipman dashed off to his chest, without stopping even to tell his messmates of what had occurred, and hurrying back on deck again reported himself as ordered.

Five minutes later the ship had left them and was steaming off to the westward, and the cutter, hoisting her sails to the light off-shore breeze, resumed her work of watching the coast.

“But are you quite certain of what you’ve just told me?” asked Thompson, rather incredulously, when, an hour later, Tubby imparted his secret.

“Yes, sir, quite,” said the boy. “I told the commander directly I got on board, and he told the skip—the captain, sir. He evidently believes it, sir. I’m quite certain myself, too,” he reiterated.

“Well, we’ll have a try at this dhow of yours, and if we do get her, it’ll be a bit of a feather in your cap, young man.”

Tubby looked very pleased.

“Luckily,” continued the lieutenant, “the watch tower you mention is on our beat. Just to the east’ard of the village where you went. You say they were to land the stuff four hours after sunset four days from now. Is that correct?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, at that time, close on midnight, I should think it ’ud be, this boat’ll pull into the bay by the watch tower, and, with any luck, granted of course that this yarn of yours is all right, we’ll collar ’em red-handed.”

Tubby sincerely hoped they would. He did not want to be made a fool of.

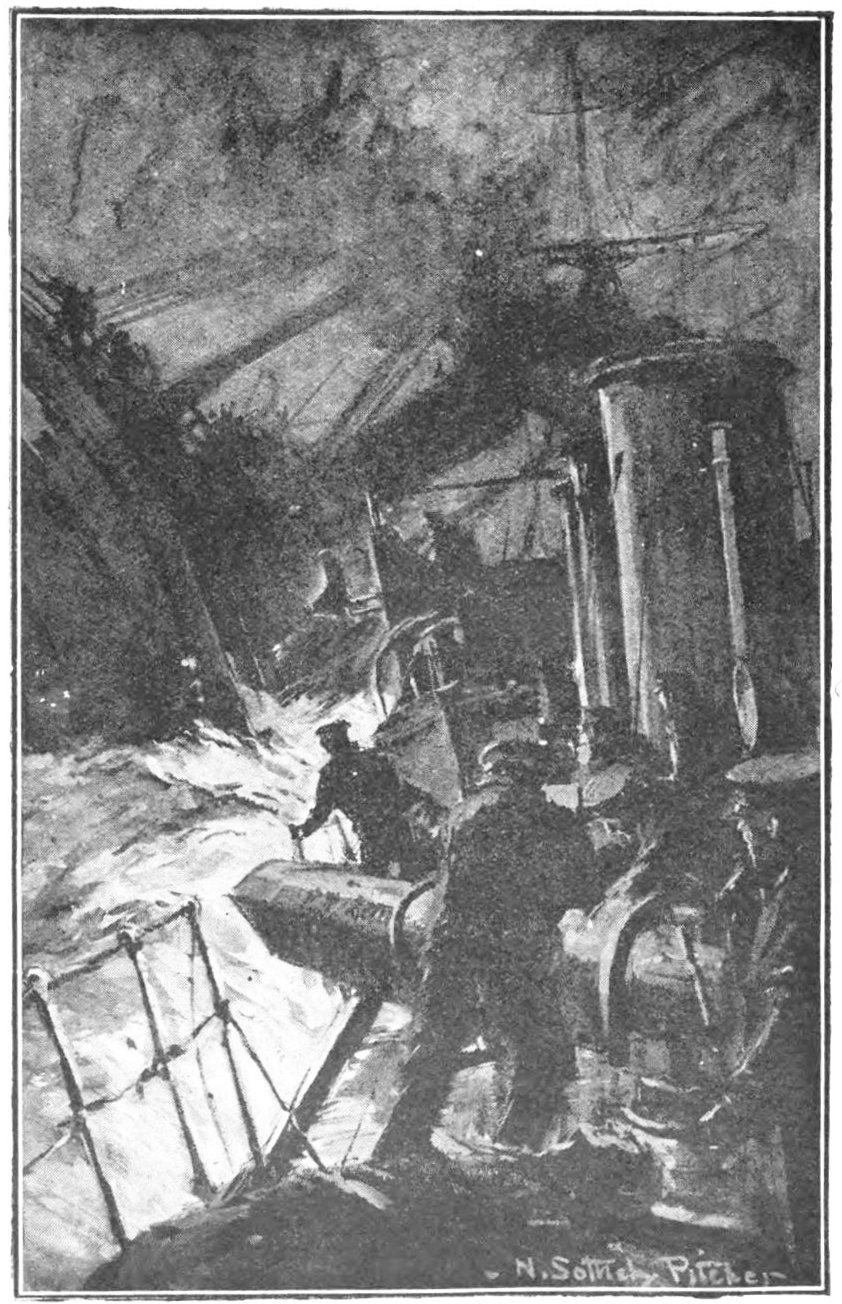

The night was very dark with no moon; hardly a ripple disturbed the glassy surface of the water, and silently, for her oars were muffled, the cutter crept on.

“There’s the watch tower!” said Thompson in a whisper, pointing away to the port bow where a dim shape could just be seen against the blue of the sky.

Tubby took his watch out of his pocket and held it close to the shaded lantern in the stern of the boat. “By Jove!” he ejaculated.

“What’s the matter?” Thompson inquired.

“It’s nearly one o’clock, sir,” the boy replied anxiously. “She ought to be here by now.” Then a sudden horrible thought flashed through his mind. “I clean forgot!” he exclaimed in an agitated whisper.

“Forgot what?”

“That when the Arabs chased us I talked to ’em in Arabic, sir. They’ll know that I understood what was said about the rifles, and they may have been able to tell the dhow to go somewhere else. Suppose—— ” but he was interrupted by the coxswain.

“I thought I seed somethink over there, sir,” whispered the man excitedly, pointing to starboard. “A sort o’ shadow like—— Yessir,” he suddenly broke off, “there’s somethink there right enough!”

“Hard-a-port! Steer straight for it!” ordered the lieutenant, seeing what the man was pointing at.

Before they had gone fifty yards in the new direction the shadow resolved itself into the familiar outline of a dhow heading in for the land. The wind had dropped, but those in the cutter could hear the creaking of her sweeps as she approached. Nearer and nearer she drew. Three hundred yards—two hundred—one hundred. Tubby unbuttoned the holster of his revolver and waited; the seconds seemed interminable. Then, quite suddenly, the Arabs became aware that they were not alone, for a loud hail came out of the{28} darkness. “Is that thou, O Takadin?” yelled a voice in Arabic, its owner probably thinking that a boat must have come out from the village to guide them into the anchorage.

“Tell ’em to heave to!” ordered Thompson.

Tubby did so.

“Name of Allah!” shrieked the voice in alarm. “Arm yourselves, my brothers! The Kafir dogs are upon us!”

A spit of flame broke out from the black shape ahead, and a bullet sang off into the darkness.

“Give ’em a round or two from the maxim!” cried Thompson.

“Pop, pop, pop—pop, pop,” went the little weapon.

A chorus of yells and shrieks came from the dhow, and the movement of her oars ceased abruptly as the crew sprang for their weapons. No further shots were fired, but a few sturdy strokes brought the cutter alongside, and boating their oars the bluejackets endeavoured to board. But the vessel’s high bulwarks were lined with armed Arabs, who slashed and hewed with their swords whenever a head appeared over the gunwale. Twice were the sailors driven back into their boat by sheer weight of superior numbers, and for a time the result hung in the balance, for even with their cutlasses and revolvers they could not gain a footing on the enemy’s deck.

Thompson, however, summed up the situation, and noticing that the greater number of the enemy were busy repelling the attack from the stern of the boat, suddenly leapt forward and clambered on board the dhow from there, before anyone{29} could arrive to resist him. He was followed by three men, and the instant they were seen, all the Arabs came forward to drive them back. This diversion gave the others the opportunity they wanted, and before he quite understood what had happened, Tubby found himself scrambling on board followed by the men. Rushing forward, with a revolver in one hand and a drawn cutlass in the other, he instantly found himself confronted by a tall Arab armed with a curved sword. The man made a wild slash, his keen blade whistling within a couple of inches of the midshipman’s shoulder, but before he could recover himself Tubby’s revolver spoke, and the man collapsed in a heap. Another assailant came at him with a pistol, and while the boy was still fumbling with his weapon, for it was very dark, there was a spit of flame, a loud report, and he felt a burning sensation in his left arm. He dropped his revolver with the pain, but before his attacker could do further damage, a bluejacket had felled him with the butt of a rifle.

It was a ghastly business, for the Arabs were desperate, and the British had their work cut out. The sharp reports of rifles and revolvers, the dull thudding of falling blades, the shouts of the sailors, and the wild yells of the enemy, converted the peaceful night into a seething pandemonium of sound. But it could not last for very long, for at last only three Arabs remained, and these, fighting desperately, had been driven into a corner.

“Ask ’em if they’ll surrender,” panted Thompson. “Tell ’em they won’t be killed.”

Tubby did so, and the men dropped their{30} weapons with a clatter. It was the last thing he remembered, for, overcome by the pain of his wound, he suddenly collapsed in a heap on the deck.

Thompson sprang forward to his assistance. “What’s the matter, Plantagenet?” he asked, not knowing the boy was wounded.

But Tubby had fainted.

. . . . . .

The next day the captured dhow, which was found to have on board 2500 rifles and many thousands of rounds of ammunition, met H.M.S. Clytia. The wounded, for by some miraculous chance none of the boat’s crew had been killed, were transferred to the ship, and Tubby, who was only slightly wounded, at once found himself a regular hero, and the subject of envy from all his messmates. He pretended to hate this notoriety, especially when the captain sent for and congratulated him personally, but his cup of happiness was not yet full.

About six months later, when the ship was at Colombo, Tubby was again ushered into his commanding officer’s presence.

“Mr. Plantagenet,” said the captain, “I have been directed by My Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to inform you that your name has been noted for early promotion to the rank of lieutenant on your passing the necessary examinations.” He looked up with a twinkle in his eye to see how the boy took it.

“Sir!” gasped the midshipman, hardly able to believe his ears.

The captain handed him the paper he had been reading. “Read it yourself,” he said.

Tubby stared at the typewritten sheets in amazement. He had had no inkling of this. He, Arthur Geoffrey Plantagenet—oh, really it was too much. He burst out into a delighted chuckle.

“Pirates!” laughed the mate. “Of course there are. Why d’you ask?”

“I was reading in a book this afternoon that there were no such things nowadays,” replied the boy. “But tell me,” he queried anxiously, “do they still kill people, and make them walk the plank, and all that sort of thing?”

“Don’t think they make ’em walk the plank,” answered the mate, cutting himself another slice of bread. “But nearly every Chinese fisherman is a pirate at heart, and some of ’em ’ud think nothing of attacking a ship if they had half a chance.”

“Do they come out to sea, then?” asked Jim excitedly, for the subject fascinated him.

“No, there are too many gunboats and cruisers knocking about, but if a junk full of Chinamen came across a defenceless ship they’d attack her all right, and kill every soul on board if they resisted. They’re born thieves when there’s any loot to be had—aren’t they, sir?” he asked, turning to the captain.

“Aye, that they are,” agreed Captain McCaul.{33} “I’ve heard of a good many cases where they’ve done it.”

“Is that why we’ve got those rifles on board, then?” asked Jim, who remembered having seen half-a-dozen weapons in a rack in the chartroom.

The mate and skipper nodded together.

The three of them, Captain McCaul, Mr. Dowell, the mate, and Jim McCaul, the captain’s son, were sitting at supper in the saloon of the steamer Hoi-Hau, now steaming up the Yellow Sea on her way from Shanghai to the North China ports with a general cargo.

The Hoi-Hau was rather an old tub, and though his owners had offered Captain McCaul the command of one of their larger vessels, the gruff old Scotsman had preferred to remain where he was. His wife and family lived in Shanghai, and as the ship was engaged in the North China trade, he saw more of his home than if he were in command of a passenger boat.

Jim McCaul, his eldest son, a boy of fifteen, was at school at Shanghai, and with the idea of giving him a change the skipper frequently took him to sea when the holidays came round.

The boy naturally looked upon his occasional sea trips as a great treat, for besides giving him the opportunity of seeing all sorts of strange places, Mr. Dowell took a great interest in him, and it was really due to the officer’s coaching that Jim had become quite a good seaman.

Supper was soon over, and, accompanied by his son, Captain McCaul left the saloon and clambered up on to the bridge. The sun had set, and overhead the stars were beginning to twinkle in the{34} sky, while there was hardly a breath of wind to mar the smooth surface of the sea.

“By George!” exclaimed Jim, “it’s a ripping night!”

“Don’t know so much about that,” growled the skipper, sniffing the air. “I’d rather have a little breeze. With calm weather like this we may find ourselves in for a fog off the Shantung Promontory. What d’you think about it, Martin?” he asked the second mate, who happened to be on watch.

“Don’t like it at all, sir,” replied that officer.

The captain grunted.

“Well,” he said, “we ought to be rounding the Promontory at about three o’clock to-morrow morning. I’ll turn in now, as I shall be on deck at midnight. Call me at once if it comes on thick.”

McCaul, accompanied by Jim, left the bridge.

“Good night, my son,” he said, halting outside his cabin by the charthouse. “To-morrow I’ll take you for a run at Chifu. I’ve to go ashore to see the agents.”

“That’ll be grand,” said Jim, pleased at the idea. “Good night, father.”

The skipper disappeared into his cabin, and Jim went below and turned in. For an hour he lay reading, but then his weariness overcame him, and blowing out his candle he fell asleep with the regular throb of the propeller sounding in his ears.

The captain’s prophecy about fog turned out to be correct, for shortly after he went on deck at midnight, the clear horizon ahead of the ship became blotted out. By one o’clock the stars{35} were barely visible through the pall overhead, while half an hour later it was thick fog.

The skipper accordingly eased the engines until the vessel was travelling at six knots, and began pulling the syren lanyard every two minutes in making the prescribed fog signal.

The hoarse braying of the powerful instrument woke all the sleepers, but Jim felt too lazy to get up, and after getting used to the dismal sound, rolled over and fell off to sleep again.

Soon afterwards, Dowell, clad in a greatcoat over his pyjamas, went up on to the bridge.

“Hullo,” said the captain. “What’s brought you up here?”

“Syren kept me awake, sir,” the mate explained, “and I came up to see if you wanted any soundings taken.”

“Thanks. I think you’d better get the machine going,” said the skipper.

Dowell went aft to the poop with two of the Chinese crew, and before long the wire of the sounding machine was released, and the lead descended to the bottom. He noticed that it took a much shorter time than it should have, for the ship ought to have been in sixty fathoms, and winding up the wire as fast as he could, he anxiously compared the glass tube with the graduated scale. To his horror the depth was no more than seventeen fathoms!

He began to run forward to report the fact to the bridge, for it was quite obvious that the ship was too near the shore, but hardly had he taken two steps when the vessel gave a quivering shudder, and he could feel her grinding and bumping over some object far below the waterline.

Presently the engines stopped with a jar, and all movement ceased. The ship had struck a ledge of submerged rock, and was fast ashore.

Dowell, with the second mate and Jim, the two latter having been awakened by the shock, all arrived on the bridge at much the same moment, while the native crew, terrified out of their senses, had turned out of the forecastle, and were clustered on deck chattering loudly.

“What’s happened, sir?” asked Dowell breathlessly, although he well knew what the answer would be.

“We’re ashore,” replied the captain. “You’d better get the boats turned out, provisioned, and ready for lowering, Martin,” he went on, addressing the second mate. “Go round with the chief engineer and see what damage has been done, and then report to me.”

The boats were turned out and provisioned, and presently Parton, the chief engineer, came on to the bridge to make his report.

“Well, captain,” he said, “I don’t think there’s much damage.”

The skipper heaved a deep sigh of relief.

“From what I can see she’s leakin’ a bit under number one and two holds, but the pumps are keeping the flow down quite easily.”

“Thank goodness for that!” ejaculated McCaul. “There’s no reason why we shouldn’t float off at high water, then?”

The fog was still very thick, but soon after daylight, when the effect of the morning sun began to make itself felt, the outline of land became visible, and when at length the mist had com{37}pletely dispersed it could be seen that the steamer was ashore on a ledge of rock within a stone’s throw of the coast.

To the right, the shore was one uninterrupted line of cliff, but a mile or so to the left of where the vessel lay, these abrupt slopes gave way to a shallow, sandy bay in which were anchored several Chinese junks.

At the head of the bay was a straggling native village, and on looking at it through his glasses the captain could see the inhabitants clustered on the beach gazing with obvious astonishment at the stranded steamer.

An hour passed without incident, the pumps managing to keep down the flow of water, but towards eight o’clock the nearest junk weighed her anchor, and with her brown sails bellying out in the breeze drew near the Hoi-Hau.

She approached rapidly, and when within a hundred yards of the steamer hove to. Soon afterwards a native sampan put off from her side, and came to the steamer, while a big, dark-skinned Chinaman, clad in loose blue coat and trousers, clambered up the rope ladder, and appeared on deck.

“Steamer makee go ashore, cap’n,” he remarked in pidgin English. “Velly much damage, wanchee help, eh?”

“No, thanks,” answered McCaul. “Ship no b’long damage. Can get off at high water.”

“Have got plentee coolie makee help,” repeated the visitor. “Plentee stlong coolie.”

“No wanchee,” repeated the skipper, who did not like the look of the man. “No wanchee, savvy?”

“All light,” said the Chinaman, with an evil grin. “S’pose you wanchee coolie, I bling.”

The visitor descended to his sampan, and returned to the junk, which presently weighed her anchor and returned towards the neighbouring village.

“Those fellows are up to no good, sir,” observed Dowell. “That chap had a revolver under his coat, I saw the bulge it made. And look,” he continued, pointing towards the village, “something’s evidently in the wind; you don’t see Chinamen crowding together like that for nothing. I expect that fellow came aboard to have a look round, and now he’s gone back to tell the others how many of us there are. His talk about coolies was only a blind.”

“Well, I hope not,” answered the captain. “He’ll have seen there are only six Europeans aboard, counting Jim here. We can’t trust our native crew to fight.”

“What d’you propose to do, sir, if they do attack?” asked the mate.

“Prevent ’em boarding as long as possible, and then if they do get aboard, we’d better barricade ourselves under the poop. There are scuttles in the saloon there, and we can fire through them on to the deck.”

An hour later three of the native craft anchored off the village hoisted their sails, and after weighing their anchors came towards the steamer. One of them, filled with brown-skinned men, circled round, lowered her sails, and secured to the steamer’s side. Immediately she did so, the man who had been aboard before, followed by several others, began to climb the ladder.

This was the last thing Captain McCaul wanted, and going to the top of the ladder he waited till the first man’s head appeared.

“No wanchee,” he said. “Wilo”—go away—“no wanchee coolie!”

The man, however, persisted in trying to come aboard, and not liking the look of affairs the captain pushed him backwards, intending to force him down the ladder.

The Chinaman, however, slipped, and, tumbling backwards with a yell, suddenly disappeared from view, sweeping several of his friends off the ladder as he fell. They all descended with a crash on to the deck of the junk, the other occupants of which gave a series of unearthly howls as the human avalanche descended.

At this moment the mate put his head over the side of the ship to enjoy the fun, but a second later he drew it back in haste, for a shot rang out, and a bullet whistled close by his head.

Within a second or two an irregular volley broke out from the other junks. The enemy were armed with modern weapons.

The shots were ill-aimed, for though several bullets struck the superstructure close to where the officers and Jim stood, the greater number pinged harmlessly through the air overhead.

At the first discharge, the Chinese crew of the steamer fled in terror, and shut themselves up in the forecastle, leaving the six Europeans alone to defend the ship.

“They mean business!” shouted the captain, dashing to the chartroom and seizing a rifle. “Cut the ladder adrift, someone!”

The mate whipped out a knife and sawed at the{40} rope lashing, but the blade was blunt and the rope tough, and before he was half-way through one strand, a yellow face, with a long, evil-looking knife between its teeth, appeared at the ladder top.

But the stroke never came, for the rope suddenly parted with a crack, and the man disappeared backwards.

There was no time for further talking, for the enemy had now opened a furious fire, while the Europeans, having armed themselves with rifles, were lying on the deck emptying their magazines at their assailants. They succeeded in dropping a good many, but the defenders were outnumbered by more than twenty to one.

The second mate suddenly sat up with a muttered word.

“They’ve got me, the devils!” he remarked, clenching his teeth with pain. “Lucky it’s only through the left arm, so I can still use a rifle.”

He bandaged the injured member with his handkerchief and calmly went on shooting. But the enemy’s fire was becoming more accurate, and at last a bullet went through the mate’s cap and sent it flying.

“We must take cover!” exclaimed the captain, noticing what had happened. “Down on the upper deck, everyone, and take shelter behind the bulwarks!”

They got up one by one and dashed down the ladder leading to the deck, with the bullets flying round them like hail, but they all succeeded in reaching their haven of refuge without being hit.

Once behind the bulwarks they were comparatively safe, for no bullet could penetrate the stout{41} steel, and they only had to expose their heads to fire.

The fight went on for a quarter of an hour without any advantage to either side, when suddenly Jim, happening to glance round, saw a blue-clad figure with a rifle in its hand slinking along underneath the bridge.

The boy wheeled in an instant, brought the weapon to his shoulder, and fired. The shot went wide, but it served its purpose, for the man vanished.

“They’ve boarded us forward, father!” he exclaimed.

As if to prove the truth of his statement, two more pirates suddenly appeared in the direction he pointed out.

“We shall have to barricade ourselves aft,” ejaculated the captain to the others. “Come on, there’s no time to lose!”

No sooner said than done. Within two minutes the defenders had entered the saloon, and after barricading the door with such movable furniture as they could find, they took up their positions with their rifle muzzles pointing through the portholes opening out on to the deck.

For some time nothing happened, and Jim’s eyes grew tired from the glare of the strong sunlight outside. He waited, however, with rifle ready, and at last the head and shoulders of a pirate appeared round the corner of the superstructure.

He watched intently, and was just about to fire, when there came a wild yell, and fully twenty pirates came running along the superstructure deck.

“Bang—bang! Bang, bang, bang!” went the rifles, and several of the blue figures fell headlong.{42} But some of them reached the deck untouched, and taking up a position behind the hatchway coaming, opened a heavy fire.

Their bullets struck the steel bulkhead with a series of loud clangs, while Jim at his porthole had a narrow escape, a bullet whistling past his cheek and shattering a mirror the other end of the saloon. It rather unnerved him, but still he went on loading and firing, loading and firing, like a veteran.

Several more of the enemy had been hit, but before long the second engineer dropped his weapon with a clatter and clutched at his right shoulder, through which a bullet had passed.

His place at the porthole was taken by the second mate, who, though wounded, could use his rifle, and while the captain bandaged the engineer, the firing continued.

The pirates now tried rushing towards the bulkhead, but the defenders’ steady, accurate fire upset their calculations, and time after time they were driven back with loss.

For another hour nothing further happened, and though wild yelling could be heard in the fore part of the ship, there was no more firing.

“I expect they’re trying to loot the foremost hold, sir,” remarked Dowell. “They’ll have a tough job, though,” he remarked, with a grin. “All the cargo’s in big cases, and they won’t shift them in a hurry.”

The captain was just about to reply, when Jim, who happened to be taking a breath of fresh air at one of the portholes in the ship’s side, suddenly gave a yell of delight.

“What’s the matter?” asked his father.

“There’s a ship out at sea,” exclaimed the boy excitedly.

They all crowded round and gazed in the direction in which he pointed, and there, sure enough, was a small white vessel steering a course to round the point of land some distance astern of the steamer.

So far the Chinese had been too intent upon their loot to notice her, for there were no signs of movement on the part of the junks.

“I wonder if she’ll spot us?” queried the skipper anxiously. “Can’t we think of something to attract her attention?”

They all looked at each other anxiously, for this was a difficulty they had not considered.

But Jim came to the rescue.

“Father!” he said suddenly, “from her colour I believe she’s a man-of-war. Why shouldn’t we signal to her?”

The captain looked at his son.

“But how d’you propose to do it?” he asked.

“Signal to ’em by the Morse code,” said Jim.

No sooner said than done. Round the saloon were the cabins of several of the officers, and going to all of them in turn Jim purloined all the walking sticks he could lay his hands upon. He found eight in all, and lashing them together, succeeded in forming a fairly stout pole about ten feet in length. Then, tearing a large piece off a white tablecloth, he secured it to one end, and going to one of the portholes thrust his improvised flag through it, and began to wave it to and fro in a series of longs and shorts.

it went, spelling out the word HELP time after time.

But the Chinese had spotted the flag, and before Jim had been at work for two minutes he heard wild yells, and an instant later the rifles of his comrades were once more hard at work.

H.M. Sloop Lucifer was proceeding towards the Shantung Promontory at a steady twelve knots.

On her bridge the lieutenant on watch leant listlessly against a stanchion, slowly sweeping his telescope from side to side as he gazed through it at the land on the port bow. He was doing it more from pure force of habit than anything else, but he suddenly gave vent to a low exclamation, and, bracing himself up, held his glass perfectly steady.

“Great Cæsar’s ghost!” he remarked to himself, “there’s a steamer ashore there with some junks alongside her, and someone’s waving something white from one of her ports. Short short short short, short, short long short short, short long long short,” he read out. “Great Scott!” he exclaimed, “the fellow’s spelling out HELP!”

He left his position and went amidships, and, leaning over the bridge, gave an order to the man at the wheel below.

“Starboard, three points!”

The helmsman put the wheel over, and while the Lucifer swung round until her bows were pointing directly towards the stranded vessel, a messenger was sent to the commander to inform him of what had been sighted, and, before a minute had passed, he was on the bridge gazing intently at the stranded ship through his binoculars.

“It’s my opinion,” he remarked at length, and seeing the white flag waving to and fro, “that the Chinamen from those junks are giving the fellows on board that steamer a pretty rotten time. She probably ran ashore in that fog early this morning, and they’re looting her.”

He walked across to the engine-room telegraph, and jammed it on to “Full Speed.”

“Travers,” he resumed, turning to the officer of the watch, “get a gun’s crew up and load one of the foremost 4-inch guns.”

The lieutenant saluted, and a few minutes later the quickfirer had been cleared away, and its lean muzzle was pointing in the direction of the steamer.

It was not until the sloop was within a couple of miles of the wreck that the pirates noticed her, but the minute they did so they were flung into a state of frantic confusion, for they could be seen tumbling over each other in their haste as they clambered down the sides of the steamer and aboard their junks.

By the time the Lucifer was within half a mile the clumsy native craft had hoisted their sails and were speeding back towards the village.

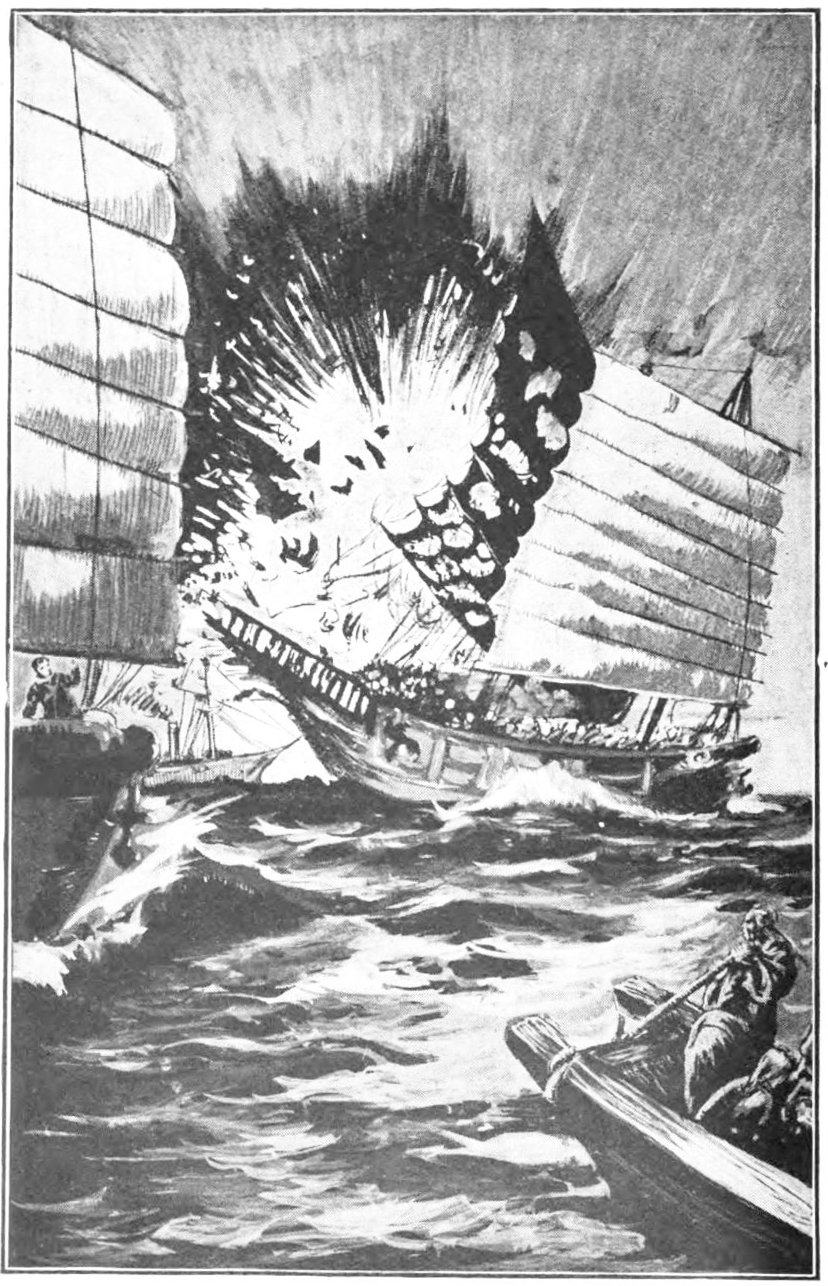

The commander slowed his engines, and at the same moment hailed the officer on the forecastle. The gun muzzle quivered until it was pointing full at the leading junk, now well clear of the Hoi-Hau, and a second later there was a sharp report, a sheet of blinding flame, and a four-inch shell screeched its way through the air.

. . . . . .

Aboard the Hoi-Hau things had not been progressing very satisfactorily.

Again and again the Chinese had attacked and had been repulsed, but finally the sheer weight of numbers had told, and when at last the ammunition of the defenders had dwindled to an alarming degree, the pirates had succeeded in reaching the bulkhead.

Once in this position, the British could not fire without exposing themselves, and the enemy began to beat down the door to get at those inside.

Captain McCaul and his officers had made up their minds for the worst, when Jim suddenly stopped waving his flag.

“Hurrah!” he yelled. “She’s coming this way!”

The welcome announcement put new heart into the defenders and they nerved themselves for a desperate resistance, for the entry of the Chinese was now a matter of minutes.

A short time later events took quite an unexpected turn. The enemy, seeing the approaching man-of-war for the first time, suddenly abandoned the attack and retreated to their junks, while the defenders, too thankful to speak, made their way out of the saloon and went on deck.

Closer and closer came the little sloop, until, when the junks were all clear of the steamer and had hoisted their sails, she opened fire. The first shell struck up the water a hundred yards short of the leading junk, and flew off into the air with a savage whine.

The pirates redoubled their efforts to escape, shrieking and yelling as they plied the sweeps to assist the sails. But it was too late, and their efforts were in vain, for the four-inch gun barked

again, and this time the projectile hit the leading junk full in the stern.

Jim had a fleeting glimpse of a sheet of flame; he saw the masts of the native craft falling, whilst masses of debris were flung skywards by the force of the powerful explosive.

When the smoke cleared away the junk was barely recognisable, for she lay low in the water like a derelict, and already the flames were licking at her battered timbers.

Another sharp report came from the sloop, and this time the shot pitched into the water under the bows of a second enemy.

The Chinese then realised that the game was up, for, lowering the sails, most of them jumped overboard and began to swim for the shore, while before very long the Lucifer’s boats, filled with armed bluejackets, were taking possession of the abandoned craft.

Soon afterwards the commander of the sloop came aboard the Hoi-Hau.

“Good morning, captain,” he said, advancing towards McCaul, and glancing round the decks in astonishment. “You seem to have been having a pretty bad time.”

“If you hadn’t come,” said the skipper gratefully, wringing his visitor’s hand, “they’d have broken down the door and murdered the lot of us.”

“By the way,” remarked the commander, “Who was that fellow of yours making signals to us?”

“Here he is,” replied McCaul, pushing Jim forward. “He’s my son.”

“It’s lucky you made that signal, youngster,” said the naval officer. “We’d spotted you all right, but if you hadn’t waved your flag we might{48} have been too late. Where did you learn your Morse, by the way?”

“I’m a Scout, sir,” Jim explained, blushing furiously.

“Just as well you are, my boy,” said the officer with a twinkle in his eye. “You ought to be proud of your son, captain,” he resumed, turning to McCaul.

“Proud!” laughed the skipper. “Proud! Of course I am!”

. . . . . .

When the tide rose, the Hoi-Hau floated off the rocks with but little damage, and before long was once more on her voyage to Chifu.

The bluejackets of the sloop succeeded in capturing the greater number of the pirates, and it was subsequently found that they belonged to a notorious band who had preyed on the defenceless trading junks for some time past.

Jim, as may well be imagined, has never forgotten his one and only brush with pirates.

(The following story is not mere fiction, for the events therein described actually occurred during the South African War.)

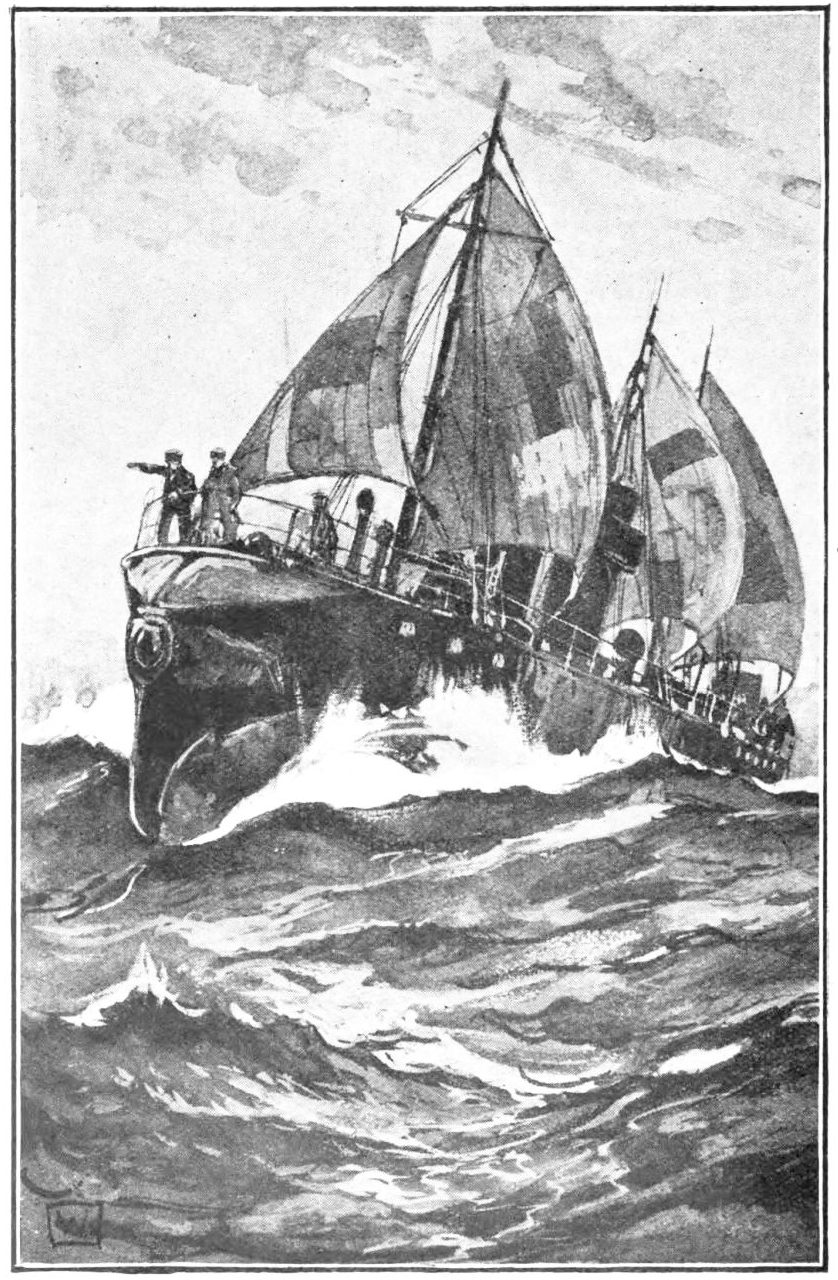

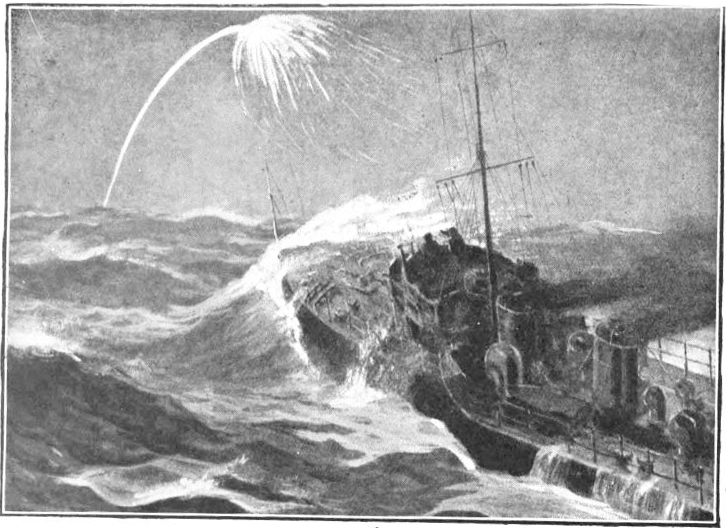

H.M. Torpedo-boat Number 60 was pursuing her way northward along the western coast of Cape Colony at a steady ten knots. As a matter of fact the exact course was N.N.W., and this took the little craft along parallel to the coast and some fifteen miles off it, while Robben Island, thirty miles to the northward of Capetown, had been abeam at noon, so the ship was well on her way up the coast in the direction of Cape Castle.

It was a beautiful afternoon, with a clear blue sky, unflecked by the least vestige of cloud, while the sun overhead converted the sea into one vast expanse of shimmering light. There was a gentle breeze from the south-east, but it was not sufficient to raise a sea, and the great ocean was only disturbed by a slight swell rolling in from the westward, over which the little torpedo-boat rode with an easy movement.

It was 1901, when the South African War was at its height and the whole of Cape Colony and Natal was one great military camp. The daily{50} arrival of transports had come to be looked upon as a mere matter of routine, for the war had been going on for eighteen months. The Navy, too, was not idle, for many men belonging to the Cape of Good Hope Squadron had been at the front with their guns, fighting side by side with their soldier comrades, while the coasts of Cape Colony and Natal had also to be patrolled.

There were at that time comparatively few ships on the Cape station, and as many hundreds of miles of coast had to be covered, all the torpedo-boats in reserve at the naval base at Simonstown had been requisitioned for this service, and though hardly suitable for the task, they performed their work with a thoroughness which left nothing to be desired. Through lack of lieutenants the greater number of them were commanded by gunners, and No. 60, the little vessel with which we are concerned, was in charge of Mr. Samuel Hyne, a warrant officer of this rank.

Small as she was, he was proud of her, and though her 65 tons displacement, her 127½ feet of length, her 15 men, and her armament of four 14-inch torpedo tubes, besides one three-pounder Hotchkiss and a solitary 45-inch maxim, made her a very puny and insignificant little craft, she was, in Hyne’s eyes, quite the smartest thing afloat flying the White Ensign. He was proud of her, for his pennant flew at her masthead, and though in 1886, when she first saw the light of day, she could do her 20½ knots with her single screw, and now could steam no more than, as he himself would call it, “eighteen and a kick,” he revelled, like many others, in the delights of his first independent command.

Close alongside the after torpedo tubes, and near the hatch leading to the stuffy wardroom, the skipper sat on a camp stool having a friendly yarn with the chief engine-room artificer, Watson, who, though only a chief petty officer, was the engineer of the ship. It was hardly possible to tell the chief E.R.A. from his commanding officer, for both were clad in nothing but trousers and singlets open at the neck. It was noticeable, though, that the engineer never omitted the “Sir” when addressing his senior, even though the two men were close friends.

“It’s all very well for you to say I’m lucky to have this job,” the gunner was saying. “I dare say I am, but lucky or not, I’d far sooner have had a chance of getting to the front!”

“Yes,” nodded the chief E.R.A., reaching for his tobacco pouch, “but if you ’ad, sir, maybe you’d a got a bullet through you, same as Mister McFiggis, o’ the Doris, did up at Graspan. ’E was full o’ beans when ’e left the ship, but ’e nearly pegged out in ’orspital. Lor’ bless me ’eart an’ soul, ’e didn’t want no more soldierin’. Lor’ lumme, no!”

“I wouldn’t mind running the risk of that,” answered Hyne, “if only I had the chance of doing something. They’ll get medals and bars, and distinguished service orders, and goodness only knows what, and I’m busted if we’ll get so much as a bloomin’ ‘thank you’ for patrolling this blessed coast. Not so much as a thank you,” he reiterated mournfully, glancing at the dull purple serrated edge of the mountains away on the starboard beam. “I’m sick of it all!”

“Well, it’s not your fault, sir,” went on the chief E.R.A. “You can’t do more’n obey your orders, an’ if you don’t get your chance you don’t, and that’s all about it.”

The gunner laughed, and both men relapsed into a silence which was only broken by the gentle ripple of the water as the torpedo-boat forced her way through it.

The afternoon wore on, and at four o’clock Hyne went forward to relieve the coxswain on watch. The orders were turned over, and the petty officer went aft to his little cupboard of a mess, and was soon busy with his tea, which meal consisted of stale bread, fried eggs of doubtful origin, and well-stewed navy tea with no milk, for in those days condensed milk was not served out by a paternal Government.

It was about one bell in the first dog-watch (4.30 p.m.) that the gunner, who was gazing abstractedly at the distant land, felt a sudden tremor from the after part of the ship. At first he paid no attention to it, for the little ship always vibrated badly, but when there came an awful bump, followed by a jarring grind, and then a fearful clatter from the neighbourhood of the engine-room, he realised something serious had happened, and commenced to run aft.

He was just in time to see the chief E.R.A. disappear down the engine-room hatch like a shot rabbit, while the coxswain, with an anxious face, was climbing up the ladder from his mess.

“What’s happened?” cried Hyne.

“I don’t rightly know, sir,” answered Naylor, the coxswain. “Me an’ th’ chief was sittin’ in th’ mess when we ’ears a bump an’ then a grindin{53}’, an’ then th’ engines start ’eavin’ round fit ter bust!”

Descending the greasy ladder, the gunner went below into the engine-room. Seeing a group of perspiring men in the after part of the little compartment, he went up to them.

“What’s the matter?” he asked.

“Shaft’s gone clean in half, sir,” said Watson, looking up.

“Lord help us!” gasped the skipper. “Is it possible to do anything to it?”

“No, sir,” replied Watson, wiping his perspiring face with a bit of dirty oily waste until it was streaked with black. “It’s a proper dockyard job I’m afraid, it’s gone clean across!”

“Are we making any water?”

“Don’t think so, sir,” said the other. “If we had a’ been it ’ud found its way for’ard by this time. It’ll have strained the stern gland a bit, but the broken part of the shaft’s still there, and I expect I can keep the flow under with the ejectors.”

“I hope you can,” remarked Hyne, “but let’s go aft and have a look.”

They left the engine-room, and going aft along the upper deck visited all the stern compartments in turn.

“There’s no damage to speak of,” said Watson, when the survey was completed. “Th’ gland’s weeping a bit more’n usual, an’ one or two rivet heads are sheared off an’ one or two plates a bit buckled. We can keep the water under all right, an’ I’ll get th’ ejectors workin’ at once. But we can’t steam another inch, of course.”

He vanished below, and while he set the pumps{54} to work Hyne thought over the situation. He was placed in a most unenviable position, for No. 60, having, like the majority of the older torpedo-boats, only one screw, was absolutely helpless with her tail shaft fractured. Even if they had a spare length of shafting it could not be placed in position. He grew pale as he thought of what might happen. The mighty Agulhas current would carry the disabled ship to the northward, and though he had food and water sufficient for perhaps a week’s consumption if he put the men on half rations, affairs still looked pretty desperate, unless some passing steamer gave the torpedo-boat a tow into harbour. She was, however, out of the track of steamers running to Capetown, and her size did not make her a very conspicuous object.

The one small dinghy the little vessel carried would not accommodate more than eight of her men at the very outside, and if the ship had to be abandoned the other men would have to be towed astern in life-buoys, while their progress would naturally be slow, and their chance of reaching the coast, twenty miles distant, doubtful in the extreme. Even allowing that it was possible, the sea was infested with sharks, so Hyne dismissed the idea as impossible almost as soon as he thought of it.

Going aft he was met by the coxswain.

“Get the ship’s company aft, Naylor,” he ordered.

“Aye, aye, sir.”

Soon afterwards the little crew had been collected, and, stepping forward, the petty officer reported, “Ship’s company present, sir,” in his best battleship manner.

“Men,” began Hyne, getting on to the after torpedo tube, “I’ve not brought you up here to spin a long yarn. You all know what’s happened, and that we’re practically helpless twenty miles from land, and out of the track of shipping. We’ve got three days’ grub on board, say four with what we’ve got in the wardroom, so, in case of accidents, we’ll pool the lot and put everyone on half whack!

“It’s a poor look out, I don’t mind telling you,” he went on to say, “but still we’ve a chance. The weather’s fine, and though we can’t steam, we can sail....

“Yes,” he said, noticing that the men were looking at each other in surprise, “I daresay sailing a torpedo-boat sounds strange, but it’s got to be done! Saldanha Bay’s the best place to make for, it’s about thirty miles nor’-east of us, and as the wind’s freshening every minute and going round to the southward, we’ll have it on the starboard quarter. We must buckle to, and rig up a couple of extra masts—bearing out spars’ll do—and we must cut up every bit o’ canvas in the ship, and make it into sails. Four hours at the outside must see us under way, and though we shan’t go very fast, I hope we’ll make Saldanha Bay some time to-morrow. That’s all I’ve got to say, and now I want you to buckle to and rig up the masts and make the sails.”

The men cheered as he dismissed them, and before long they were hard at work furling the awnings while the storerooms were burgled for every inch of canvas they contained. Presently those of the men who could use a sail-maker’s palm and needle were busy sewing the lengths together, while others placed and stayed the spars to serve{56} as main and mizzen masts, for the torpedo-boat only carried one stumpy mast forward.

By eight o’clock, when the sun sank to rest beneath the western horizon in a blaze of scarlet and gold, everything was ready except the sails.

“Come on, lads! Bear a hand!” shouted Hyne cheerfully to encourage the men sewing, and noting with satisfaction that the breeze from the southward was momentarily freshening. “We must get sail on her as soon as we can!” The bluejackets worked with a will, and half an hour later a small jib and triangular trysail were set on the foremast. They were anything but well cut or shapely, for they had been made out of the awning, but still they served their purpose, for as soon as they were hoisted the wind bellied them out, and the little vessel heeled over and began to move through the water.

“Steer east-nor’-east!” said Hyne to the coxswain, as the latter ran forward to take the wheel, and, as the rudder went over, the skipper saw with satisfaction that the ship answered her helm.

By nine o’clock it was pitch dark, and the stars had begun to twinkle in the dark blue of the sky overhead, and soon afterwards the other sails were ready, and were set on the spars serving as main and mizzen masts. The torpedo-boat slipped still faster through the water, until she was making about four knots, while the men, highly satisfied with their work, had their frugal supper of stale bread and bully beef.

The hours dragged wearily by, but by midnight the breeze had developed into a strong wind, which still blew from the same direction. The sea, however, had got up, and the little ship wallowed

heavily as she crawled along at her leisurely gait, but as the stars still shone it did not appear as if the weather was going to get any worse. The gunner and coxswain spent the whole night on deck, and at five o’clock the next morning the first signs of dawn appeared over a serrated band of obscurity on the horizon which could only be land. Hyne, exhausted as he was, felt quite cheerful when he saw it, and when daylight came he saw, to his inexpressible relief, that the entrance to Saldanha Bay was in sight a short distance to the northward.

Two hours later the crippled torpedo-boat crawled into the harbour, and passing several steamers and sailing craft at anchor, whose crews broke into ironical cheers as she crept by, finally dropped her anchor off the settlement.

“Well, sir,” remarked the chief E.R.A. to Hyne, as the latter went aft towards the wardroom hatch, “you’ve had your chance all right, if you’ll excuse my saying so, sir, and I reckon the Admiral’ll have something nice to say to you when we get back to Simonstown.”

“Nice!” sniffed Hyne. “Nice indeed! I expect he’ll order me to be court-martialled on the spot because the shaft broke. Endangering one of His Majesty’s ships, and all the rest of it!”

“I ’ope not!” declared Watson, dropping his h’s in his nervousness. “Hindeed! I ’ope not!”

“Well, we’ll see,” said the gunner, going down the ladder; “but meanwhile I’m going to send a wire reporting what has happened.”

. . . . . .

A week later H.M. Torpedo-boat No. 60 arrived at Simonstown behind the second-class cruiser which had been sent to Saldanha Bay to tow her back. The news of her vicissitudes was already common property, and as she passed by, the men-of-war on her way to the dockyard, a string of coloured bunting crept to the masthead of the flagship and fluttered out in the breeze. An instant later the sides and rigging of the war vessels were black with men, and as No. 60 passed cheer after cheer rang out across the water.

“What the deuce do they want to make all that shindy about?” growled Hyne, who, if the truth must be told, felt rather relieved at the reception.

“I expects you’ll find out orl rite when yer reports yer arrival to the Admiral, sir,” murmured the coxswain.

An hour later the gunner was reporting his arrival to the Admiral on board the flagship. The Commander-in-Chief got up from the table at which he was writing.

“I’m glad to see you back, Mr. Hyne,” he said graciously, shaking hands. “I’m glad you came out of it all right. Let me hear all about it; your wire didn’t give me much news beyond the fact that you’d broken down and had ... er, sailed your torpedo-boat into Saldanha Bay.”

The story was soon told, and when the narrative was complete the Admiral rose from his chair.

“Mr. Hyne,” he said, “I congratulate you. I knew when I appointed you to No. 60 you’d do well, but I never expected this. I shall forward a report of your conduct to the Admiralty.”

“Thank you, sir!” gasped the astonished Hyne, his face turning the colour of a beet.

“And,” continued the Commander-in-Chief, “I shall be very pleased if you will come and dine at Admiralty House to-night. My wife will be interested in your story, and I’m afraid you’ll have to tell it all over again.”

. . . . . .

Six weeks later Hyne was sitting on the deck of his little command, which was on the torpedo-boat slip in the dockyard, after having been fitted with a new screw shaft. It was a hot day, and he was half dozing in his chair with his pipe between his teeth, when he was roused by the sound of shouting from forward. Presently the signalman came running aft with a signal pad in his hand.

“What’s all the noise about forward?—tell ’em to stop it at once,” said Hyne.

“Signal, sir,” said the man, “just come from the flagship. Reads ‘Admiralty informs me that Mr. Samuel Hyne, gunner, has been promoted to the rank of lieutenant. I am sure that all officers and men under my command will congratulate this officer on his well-merited promotion.’”

“Good Lord!” gasped the newly-made lieutenant, hardly able to believe his ears. “Are you quite certain it is all right? Perhaps someone’s pulling my leg.”

“No, sir, they ain’t,” declared the signalman, breaking into a grin, “an’ th’ signal goes on to say: ‘Chief Engine-room Artificer Jeremiah Watson is advanced to the rank of Artificer Engineer!{60}’”

“What’s that?” said a voice, as the chief E.R.A.’s head appeared on deck. “Let’s have a look. Are you sure it ain’t a ’oax?”

“’Oax, ’oax!” exclaimed the man; “beggin’ yer pardon, sir, the Admiral ain’t goin’ ter pull yer leg!”

He handed the signal pad across as he spoke.

“It’s all right,” said Hyne breathlessly. “I congratulate you, Mr. Watson.”

“Same here, Lieutenant Hyne,” said the other. “Didn’t I say, sir, as how they wouldn’t forget you? Aren’t you a jolly sight better off than Mister McFiggis, who got a bullet through ’im at Graspan?... Lor’ save us, though!” he added, “I didn’t know as I ’ad done anythink!”

“No, but I did, though,” said the new lieutenant, as he went below to figure out how much it would cost him to send a lengthy cable home to his wife in England.

“Well, Mister Mate,” remarked Captain Sims, rubbing his hands with satisfaction, “the noon sights give her an average of ten and a half knots since noon yesterday. Pretty good goin’!”

“Good!” replied the mate. “I should think it was, sir! This old hooker isn’t exactly in her childhood.”

The master laughed. “Well,” he said, “I’ll go below and get my dinner, and after that I shall be in my room. I’ve a lot of work to get through.”

The mate nodded and smiled, for he knew well that the captain’s “work” was done lying down on his bunk with both eyes shut, and with an accompaniment of something which sounded suspiciously like snoring.

“Keep her goin’ sou’-sou’-east,” concluded the “old man,” moving down the poop ladder, “and let me know if you sight anything.”

“Aye, aye, sir!” said Meryon, as the skipper disappeared.

The steamer Evelyn MacDonald was pursuing her leisurely way southward through the North Atlantic, on a voyage from London to Sydney,{62} via the Cape of Good Hope. She carried a valuable general cargo, and up to the present the voyage had been eminently successful, for no contrary gales or heavy seas had retarded her progress. The vessel, a steam tramp of elderly build and sluggish demeanour, was surpassing herself, for though nine and a half or ten knots was her usual speed, the patent log dial on her taffrail was now registering no less than 10·5.

The weather was certainly beautiful, and, though there was hardly a cloud overhead in the sky to dim the brilliancy of the sun, the welcome breeze, ruffling the surface of the sea until it looked like a vast spread of sapphire-coloured velvet, mitigated the fierce rays from above. Life on board, therefore, even though the ship was only a few degrees north of the equator, was bearable, and even pleasant.

It had gone one bell in the afternoon watch, and the crew had finished their midday meal and were lolling about on the forecastle in various lethargic attitudes. Some were smoking and talking, but others had dropped off to sleep with their pipes between their teeth.

“What I likes about this ’ere ship,” one of them remarked to a friend, “is that we ’ave no bloomin’ dagoes aboard. We’re hall Henglish, leastways British, an’ I reckon there’s precious few other ’ookers flyin’ th’ Red Duster as can say that!”

“That’s so, mate,” replied another seaman, whose red hair had earned for him the inevitable nickname of “Ginger.” “I reckon we’ve struck ile this trip orl rite.”

“’Allo, there’s ’Oratio!” observed the first{63} speaker, as the cook’s boy came out of the galley amidships and flung a bucket of dirty water over the ship’s side.

“’Allo, ’Oratio, me son,” cried Ginger, “’ow are ye gettin’ on dahn there? ’Ow’s th’ ole water spoiler inside?” The “water spoiler,” needless to remark, was the cook himself, Horatio’s immediate superior.

The boy—Horatio Nelson Chivers, to give him his full name—had been signed on as assistant and general bottle-washer to the cook at the last moment before the ship left England. The mate, seeing him loafing round the quay before the Evelyn MacDonald sailed, had taken him on out of pure compassion, rather than with the idea that he would be of any use; and, if the truth must be told, Horatio Nelson was about as scraggy and as weedy a looking individual as it is possible to imagine.