Title: The sunken world

Author: Stanton A. Coblentz

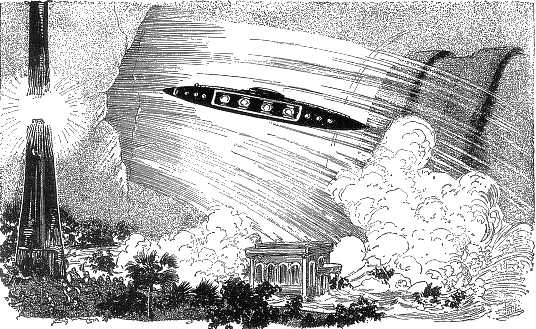

Illustrator: Frank R. Paul

Release date: November 17, 2025 [eBook #77257]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Experimenter Publishing Company, Inc, 1928

Credits: Tom Trussel and Sean/IB@DP

[p. 292]

By Stanton A. Coblentz

FOREWORD

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I – Harkness Explains His Disappearance

CHAPTER II – Untraveled Depths

CHAPTER III – On Unknown Shores

CHAPTER IV – A Tour of Exploration

CHAPTER V – The Mysterious City

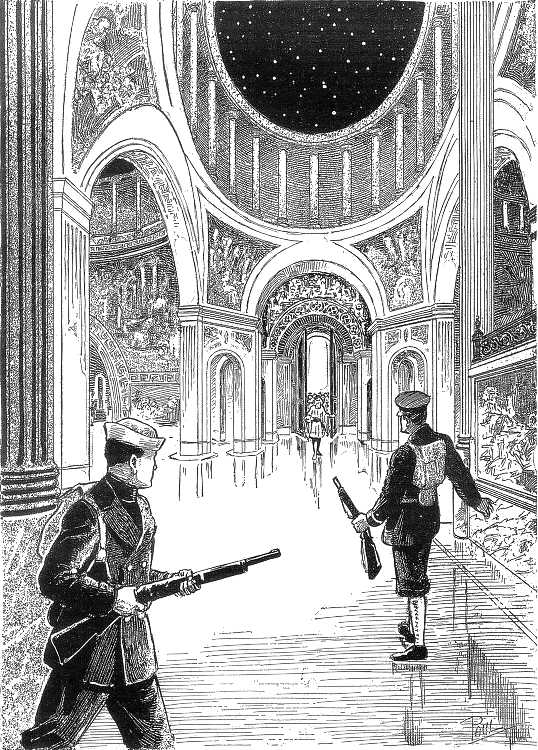

CHAPTER VI – The Temple of the Stars

CHAPTER VII – Trapped

CHAPTER VIII – Sapphire and Amber

CHAPTER IX – The Will of the Masters

CHAPTER X – Discoveries

CHAPTER XI – Questions and Answers

CHAPTER XII – The Submergence

CHAPTER XIII – Trial and Judgment

CHAPTER XIV – The Upper World Club

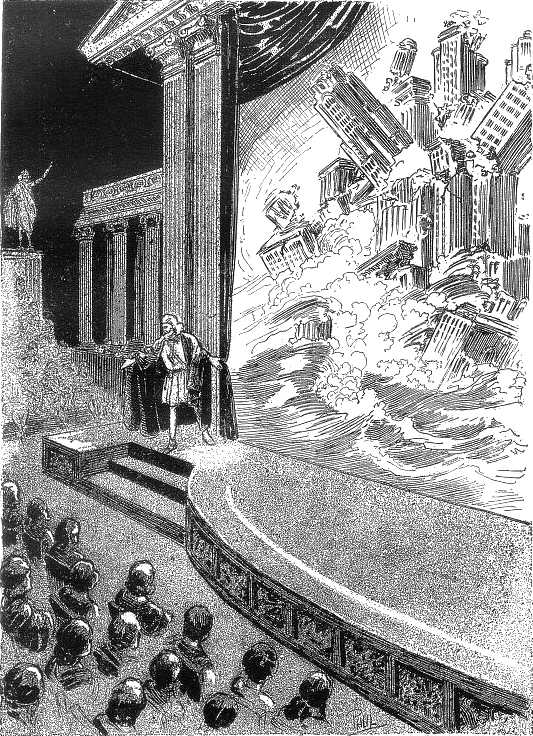

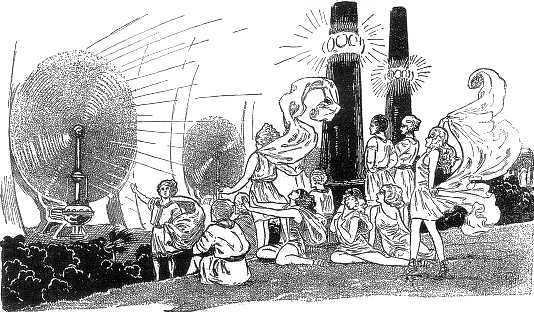

CHAPTER XV – The Pageant of the Good Destruction

CHAPTER XVI – An Official Summons

CHAPTER XVII – The High Initiation

CHAPTER XVIII – The Journey Commences

CHAPTER XIX – The Glass City

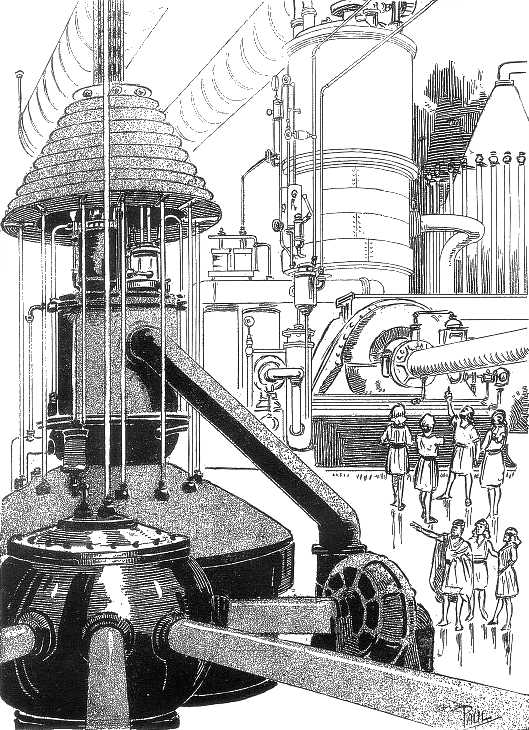

CHAPTER XX – Farm and Factory

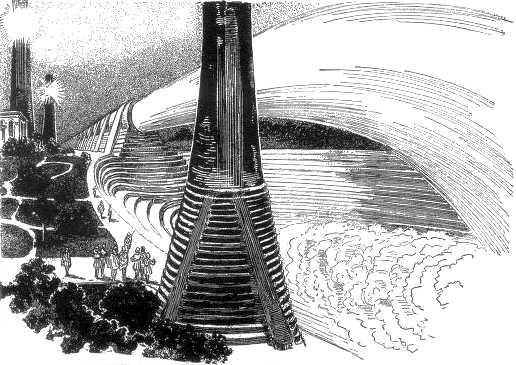

CHAPTER XXI – The Wall and the Wind-makers

CHAPTER XXII – The Journey Ends

CHAPTER XXIII – Xanocles

CHAPTER XXIV – What the Books Revealed

CHAPTER XXV – Duties and Pastimes

CHAPTER XXVI – Curiosities, Freaks and Monstrosities

CHAPTER XXVII – The Warning of the Waters

CHAPTER XXVIII – The Waters Retreat

CHAPTER XXIX – The Party of Emergence

CHAPTER XXX – Crucial Moments

CHAPTER XXXI – “The History of the Upper World”

CHAPTER XXXII – A Happy Consummation

CHAPTER XXXIII – The Flood Gates Open

CHAPTER XXXIV – Swollen Torrents

CHAPTER XXXV – The Return

Transcriber’s note

The world of literature is full of Atlantis stories, but we are certain, that there has never been a story written with the daring and with such originality as to approach “The Sunken World.”

Science is pretty well convinced today, that there was an Atlantis many thousands of years ago. Just exactly what became of it, no one knows. The author, in this story, which no doubt will become a classic some day, has approached the subject at a totally different angle than has ever been attempted before; and let no one think that the idea, daring and impossible as it would seem at first, is impossible. Nor is it at all impossible that progress and science goes and comes in waves. It may be possible that millions of years ago, the world had reached a much higher culture than we have today. Electricity and radio, and all that goes with it, may have been well known eons ago, only to be swept away and rediscovered. Every scientist knows, that practically every invention is periodically rediscovered independently. It seems there is nothing new under the sun.

But the big idea behind the author’s theme is the holding of present-day science and progress up to a certain amount of ridicule, and showing up our civilization in a sometimes grotesque mirror, which may not be always pleasing to our vanity and to our appraisal of our so-called present day achievements.

The point the author brings out is that it is one thing to have power in science and inventions, but that it is another thing to use that power correctly. He shows dramatically and vividly how it can be used and how it should be used.

From the technical standpoint, this story is tremendous, and while some of our critics, will, as usual, find fault with the hydraulics contained in this story, the fact remains they are not at all impossible.

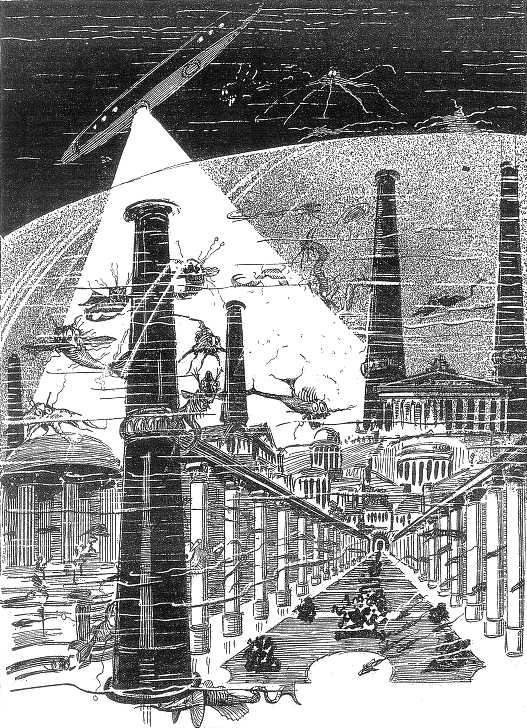

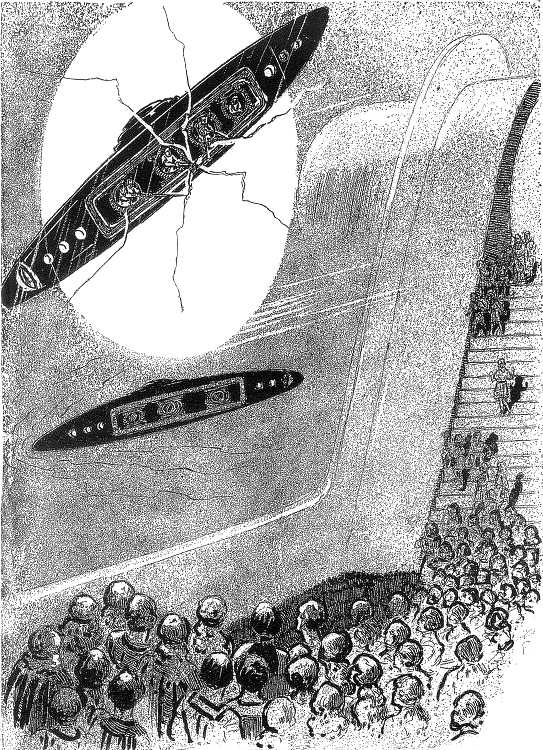

It was in the spring of 1918 that the United States submarine X-111 was launched upon its adventurous career. The German commerce raiders had now reached the height of their effectiveness; almost daily they were taking their toll of luckless seamen and provision-laden steamers; and the United States government, in alarm that was never officially admitted, had resolved upon desperate measures. The result was the X-111. The first of a fleet of undersea craft, this vessel was constructed upon lines never before attempted. Not only was it exceedingly long (being about two hundred feet from stem to stern), but it was excessively narrow, and a man had to be short indeed to stand upright within it on its single deck without coming into contact with the arching ceiling. The ship, in fact, was nothing more nor less than a long pipe-like tube of reinforced steel, able to cleave the water at tremendous speed and ram and destroy any enemy by ramming it with its beak-like prow. But this was only its slightest point of novelty. At both ends and at several points along the sides it was equipped with water-piercing searchlights of a power never before known (the creation of Walter Tamrock, the Kansas inventor who lost his life in the war); and it was provided with a series of air-tight and water-proof compartments, any one of which might be pierced without seriously injuring the vessel as a whole. Hence the X-111 was generally known as unsinkable, and upon it the American officials fastened their hopes of abating the nuisance of the enemy “U-boat.”

The sinking of this “unsinkable” vessel is now of course a matter of history. Close observers of naval events will recall how, in May, 1918, the newspapers reported the disappearance of another United States submarine. All that was known with certainty was, that the ship had been commissioned to the danger zone; that it had failed to return to its base at the expected time, and that the passing days brought no news of it; that wireless messages and searching expeditions alike proved unavailing, and that it was two months before the only clue as to its fate was found. Then it was that a British destroyer, on scout duty in the North Sea, picked up a drifting life preserver bearing the imprint “X-111.” For strategic reasons, this fact was not divulged until much later, and for strategic reasons it was not made known that the missing submarine was of a new and previously untried type; but the mystery of the X-111’s disappearance weighed heavily upon the minds of naval officials, and secretly they resolved upon immediate and exhaustive investigation. All in vain. Not a trace of the lost ship or of the thirty-nine members of its crew could be found; not a scrap of the usual drifting flotsam or wreckage could be picked up anywhere on the sea; and at last it was admitted in despair that the waters would perhaps guard their secret forever.

Seven years went by. Peace had long since returned, and the X-111 and its tragedy had been forgotten except by a few relatives of the unfortunate thirty-nine. Then suddenly the mystery was fanned into vivid life again. A bearded man, with a strange greenish complexion and eyes that blinked oddly beneath wide, colored glasses, appeared at the offices of the Navy department at Washington and claimed to be one of the company of the X-111. At first, of course, he was merely laughed at as a madman, and could induce no one to listen to him seriously; but he was so persistent in his pleas, and so anxious to give proof of his identity, that a few began to suspect that there might be some shadow of truth to his claims after all. Half-heartedly, an investigation was undertaken—and with results that left the world gaping in amazement! The testimony of a dozen witnesses, as well as the unmistakable evidence of finger-prints and handwriting, proved that the wild-looking stranger [294]was none other than Anson Harkness, Ensign on the ill-starred X-111, long mourned as dead. Now, for the first time, the truth about the disappearance of that remarkable vessel was to be made known; and the eager public was treated to a story so extraordinary that only irrefutable evidence could make it seem credible. It is safe to say that never, since Columbus returned to Spain with the news of his discoveries in seeking a western route to the far East, had any mariner delivered to his people a revelation so unexampled and marvelous.

But while numerous accounts of the great discovery are extant, and while the furore of discussion over the newspaper articles and interviews shows no sign of waning, the public has yet to read the tale in the words of Harkness himself. And it is for this reason that the accompanying history, to which Harkness has devoted himself ever since his return from exile, possesses a peculiar and timely interest. Harkness has described, unaffectedly and sincerely, the most perilous exploits which any man has ever survived. Hence the following pages should prove entertaining not only to the student of world events, but to that larger public which finds value in a rare and stirring bit of autobiography.

Stanton A. Coblentz,

(New York, 1928.)

The maiden voyage of the X-111 was ill-fated from the first. Perhaps the new inventions had not yet been perfected, or perhaps, in the haste of wartime, adequate tests had not been made; at any rate, the vessel developed mechanical troubles after her first half day at sea. To begin with, the rudder and steering apparatus proved unmanageable; then, after hours spent in making repairs, the engines showed a tendency to balk under the tremendous speed we were ordered to maintain; and finally, when we had about solved the engine problem, we had the misfortune to collide with a half-submerged derelict, while running on the surface, and one of our water-tight compartments sprang a leak.

Immediately following the accident, we had risen to the surface, for the break was about on a level with our waterline, and the compartment could not be completely flooded so long as we did not submerge. Yet Captain Gavison warned us not to waste a moment, and the men worked with desperate speed to repair the damage, for we knew that we were in the zone of the German U-boat, and that any delay might prove perilous, if not fatal. Unfortunately, the sea was unusually calm and the day was blue and clear, so that even our low-lying hulk could be sighted many miles across the waters.

I do not know precisely at what position we were then stationed, except that it was somewhere in the Eastern Atlantic, and at a point where, according to the warnings of our Secret Service, a concentration of German submarines was to be expected. At any other time we would have welcomed the opportunity to come to grips with the foe; but now, in our disabled condition, we kept a lookout with grave misgivings, and silently prayed that the damage might be repaired before the enemy slunk into view. Yet it was slow work to man the pumps and at the same time to weld a strip of metal across the jagged gap in our side; and hours passed while we stood there working thigh-deep in water, our heads bent low, for there was but two or three feet of breathing space beneath the curved iron ceiling. Suppressed growls and curses came from our lips each time a sudden surge of the waters interfered with the welding. Meanwhile all was in confusion; the men worked with the feverish inefficiency of terror, scarcely heeding the orders of the officers; the chief contents of the compartment floated about almost unnoted. I distinctly remember that several articles, including a life preserver which one of the recruits had unfastened in his fright, were washed overboard.

Still, we did make some progress, and after four or five hours, and just as the blood-red sun was sinking low in the west, we found our task nearing completion. A few more minutes, and the welding would be accomplished; a few more minutes, and darkness would be upon us, leaving us free from fear of attack for the next eight or ten hours.

It was just when we felt safest that the real danger presented itself. A swift trail of white shot across the waters far to westward, and, advancing at full speed, vanished in a long, frothy furrow just in our wake. “A German U-boat! A U-boat two points off the port bow!” frantically cried the watch; and we scrambled from the flooded compartment as the Captain gave the order “Submerge!” Now we heard the rapid churning of our engines as we went plunging into the blackness beneath the sea; now we made ready to launch a torpedo of our own as our periscope showed us the disappearing tip of an enemy submarine; now we were hurled into an exciting chase as our prodigiously powerful searchlights illumined whole leagues of the water, even revealing the dark, cigar-shaped hulk of the foe. Had we not been impeded by the dead weight of a compartment full of water, we would unquestionably have overtaken the enemy, rammed it and ended its career; even as it was, we seemed to be gaining upon it, and we had hopes of shooting up unseen and bullet-like from the dark, and with tremendous impact smiting it in two. Not even the unexpected appearance of a second submarine altered our plans. Handicapped as we were, we would show our superiority to both the enemy craft!

But it was at this point that mechanical troubles again betrayed us. Overworked by our excessive burst of speed, our engines (which were of the super-electric type recently invented by Cogswell) gave signs of slowing up and stopping; and so dangerously overheated were they, that our Captain had to halt our vessel abruptly, almost within striking distance of the foe. Our position became extremely precarious, for at any moment the German searchlights might spy us out, and a few undersea bombs might send us to the bottom.

As our own equipment had purposely been made as light as possible, we were provided with no explosive shells other than torpedoes: hence we were compelled to rise to the surface in order to attack. This, we realized, was a hazardous expedient, since both the enemy vessels were already in a position to answer our bombardment, volley for volley. But trusting to the gathering darkness and to our aggressive tactics to win us the advantage, we unhesitatingly rose to the level, and, with as little delay as possible, discharged a torpedo toward the dim, low-lying form of the foe.

[295]

Whether that projectile reached its goal, none of us will ever be able to say. From the sudden, furious eruption of spray in the direction of the enemy craft, I am inclined to believe that this was among the U-boats later reported missing; yet, the torpedo may merely have struck some floating object and so have lost its prey. Whatever the results, we were unable to observe with certainty, for at the same moment a gleaming streak shot toward us across the dark waters, and the next instant we went sprawling about the deck as a dull thudding crash came to our ears and the vessel shook and wavered as though in an earthquake’s grip. Half dazed from the shock, we gathered ourselves together and rose uncertainly to our feet, staring at one another in dull consternation. And at the same moment one of the seamen burst wildly into the cabin, despair and terror in his maddened eyes. “The central compartment!” he cried. “The central compartment. It’s flooded, all flooded!” And as if to prove his words, we felt ourselves sinking, sinking slowly, though we had not been ordered to submerge; the darkness of the twilight skies quickly gave way to the darkness beneath the ocean.

It was some minutes before we quite realized what was happening. Accustomed as we were to undersea traveling, we did not at first understand that this was an adventure quite out of the ordinary. Even when the waters had lost their first pale translucency and had become utterly black and opaque, we did not realize our terrible predicament. Only after our vessel began listing violently, and we felt the deck sloping at an angle of forty-five degrees, did we recognize the full horror of our position. Although we could see not one inch beyond the thick glass portholes, I had an indefinable sense that we were sinking, sinking down, down, down through vague and unknown abysses; and the stark and helpless terror on the assembled faces gave proof that the others shared my feelings. Not a word did we utter. Indeed, speaking would not have been easy, for a low, continuous roaring was in our ears, a hoarse, muffled roaring reminding me of the murmuring in a sea-shell. At the same time, a strange depression overwhelmed my senses; it seemed as though the atmosphere had suddenly become thick and heavy, too heavy for breathing; it seemed as though an unnatural weight had been piled upon me, threatening to crush and stifle me. Yet I did notice that the vessel quivered violently and lunged upward every few seconds, in a furious effort to right itself and rise to the surface. I did fancy that I heard the buzzing of the engines at times, an intermittent buzzing that was most disquieting; and I found myself, like the others, hanging to the brass railings to steady myself when the ship heaved and shuddered, or to keep my footing when we slanted downward.

Perhaps five minutes passed when the door leading forward was thrust open, and Captain Gavison climbed precariously into the room. All eyes were bent upon him in silent inquiry; but his grim, stoically firm countenance was far from reassuring. It was apparent that he had something to say, and that he did not care to say it; and several anxious moments elapsed while he stood glowering upon us, evidently undecided whether to give his message words.

Yet even at this crisis he could not forget discipline. His first words brought us no information, and his first action was to station us about the room in orderly fashion, assigning each to some specific duty.

“I will not keep the facts from you,” he declared, with slow, deliberate accentuation, when finally we were all in position. “Three of our compartments are flooded. The other compartments seem to be holding out as yet, but the great mass of water in our hold is bearing us rapidly downward, and the engines seem unable to neutralize the effect. At the last reading, we were nine hundred and twenty-seven feet below sea level.”

“Great God! What are we to do about it?” I gasped, in biting terror.

“Suggestions are in order,” stated the Captain, laconically.

But no suggestion was forthcoming.

“Of course, we are in no immediate danger ...” he resumed. But he might have spared his words. Most of us had had sufficient experience of undersea travel to know that the danger was real enough. Barring the remote contingency that the engines would be brought back into efficient working order, there were only two possibilities. On the one hand, we might reach the bottom of the sea, and, stranded there, would perish of starvation or slow suffocation. Or, in the second place, we might continue drifting downward until the tremendous pressure of the water, proving too strong even for the stout steel envelope of our vessel, would bend and crush it like an egg-shell.

Although we could no longer guide our course, our gigantic searchlights were at once brought into play, piercing the water with brilliant yellow streamers. Yet they might have been searchlights in a tomb, for they showed us nothing except the minute wavy dark shapes that occasionally drifted in and out of our line of vision. There was something ghastly, I thought, about that light, that intense unearthly sallow light, which glided slowly in long curves and spirals about the thick enveloping darkness. And the very penetrating power of the rays served only to accentuate the horror. For the illumination ended in nothingness; nothingness seemed to stretch above us, beneath us, and to all sides of us; we were enfolded in it as in a black mantle; it seemed to be stretching out long arms to fetter us, to gather us up, to strangle us slyly.

Slowly, with agonizing slowness, the moments crept by; slowly we continued sinking, down, down, down, ever down and down, with movement gradual and constantly diminishing, yet never ceasing. Never before in history, we told ourselves, had living men been plunged so far beneath the ocean. Our instruments recorded first twelve hundred feet, then fourteen, then sixteen, then eighteen hundred feet below sea level!

And as we sank downward, we became aware that we were not the only living creatures in these depths. Our searchlights made us the center of attraction for myriads of scaly things; whole schools and squadrons of fishes were gathering moth-like in the vivid illumination thrown out by our vessel. Some were long, snaky monsters, with thin heads set with rows of spike-like teeth, and tiny eyes that gleamed evilly in the uncanny light; some were lithe sea dragons, with wolfish mouths and sabre-like bony appendages projecting from low foreheads; some were many-colored, rainbow-hued or streaked with black and golden, or red and azure, or yellow and white; some had chameleon eyes that flashed first green and then blue, according to the play of the light about them; many were flitting to and fro, circling and spiralling and doubling back and forth at incredible speed; and not a few, unacquainted with the ways of submarines, collided full-tilt with the thick glass of our portholes.

But as our depth gradually increased, our finny visitors began to give way to others stranger still. When we were twenty-two hundred feet below the surface, the searchlights were no longer necessary to reveal the denizens of the deep, for the inhabitants of those unthinkable regions carried their own lamps! And how they amazed us and startled us!—how, in [296]our shuddering nerve-racking terror, they appeared to us as ghosts or avenging fiends, or struck our overworked imaginations as approaching foes or rescuers! Suddenly, out of the deathly blackness, a spurt of green light appeared, swiftly widening until it seemed an unearthly searchlight—and, from a narrow focus of flame, two huge burning green eyes would shoot forth, darting cold malice at us through the glass port, until the yellow electric light would seem tinged with an emerald reflection. Or else a tiny flattened disk, softly phosphorescent throughout and marked on one surface by two bright beady eyes, would come floating in our direction like a pale apparition; or, again, a long dark rod, brilliantly white like a living flashlight, would dart curving and gleaming toward us out of the remote gloomy depths. But more terrifying than any of these were the nameless monsters with invisible bodies and lidless, fiery yellow eyes of the size of baseballs,—eyes that stared in at us, and stared and stared, as though all the concentrated horror of the universe were glaring upon us, seeking to ferret us out and mark us for its victims.

And still we were sinking, unceasingly sinking, till the last faint hope had died in the heart of the most sanguine, and in despair and with half-mumbled phrases we admitted that there could be no rescue for us. When we were twenty-five hundred feet below the surface, the fury of expectation had given place to a blank and settled despondency; when the distance was twenty-eight hundred feet, each was striving in his own way to prepare himself for the fate which all felt to be but a question of hours. In our panic-stricken horror, we had all long ago forgotten the positions assigned us by the Captain; and the Captain himself did not appear to notice where we were. Young Rawson, the newest of the recruits, had gone down on his knees, and with tears in his eyes was murmuring half audible prayers; Matthew Stangale, one of the oldest and most hardened of the seamen, was pacing restlessly back and forth, back and forth, in the narrow compartment, clenching his fists furiously and muttering to himself; Daniel Howlett, veteran of many campaigns, contented himself with a suppressed growling and profanity, and his curses were echoed by his companions; Frank Ripley, a college gridiron hero, enlisted for the war, buried himself in a corner of the room, his face covered by his hands, the very picture of dejection, though every once in a while, wistfully and half-furtively, he would let his gaze travel to a little photograph he guarded close to his bosom. And as for Captain Gavison, on whom we had fastened our last fading hope of escape—he merely stood near the porthole with arms clenched behind his back and thin lips tightly compressed, peering out into the black waters as though he read there some secret hidden from the obtuse gaze of his followers.

We were below the three thousand foot level when fresh cause for anxiety appeared. “The holy saints have mercy on us!” suddenly exclaimed James Stranahan, one of the common seamen, as he crossed himself piously. And pointing in awe-stricken amazement through one of the glass spy-holes which led from the deck, down through the bottom of the ship, he called attention to a dim shimmering luminescence far below. Excitedly we crowded about him, almost tumbling over one another in our eagerness and terror, but for a moment we could see nothing. Then, slowly, as we stood straining our eyes to fathom the blackness, we became aware of a vague filmy, widespread sheet of light twinkling faintly beneath us, and remote as the stars of an inverted Milky Way.

A sheet of light beneath us, at the bottom of the sea! In incredulous astonishment, we turned to one another, scarcely able to believe our senses, our horror written plainly in our gaping eyes! And in silence, and with fear-blanched faces, half of the company made the sign of the cross.

“Sure it’s a ghost, a deep-sea ghost!” ventured the superstitious Stranahan.

“It’s where the sea serpents have their home!” put in Stangale, with an abortive attempt to be jocular. “There’s ten million of them down there, with devil’s eyes of fire!”

“Maybe it’s the Evil One himself!” suggested Stranahan, not content with a single guess. “What if it’s the very throne-room of Hell, and them are the flames of Old Nick!”

These words did not seem to reassure the rest of the crew. Several were trembling visibly, and several continued to cross themselves in silence.

Meanwhile the Captain had ordered the searchlights turned downward, and in long loops and curves the cutting light swept the darkness beneath. But not a thing was visible, except for a few flapping fishy forms; and our lanterns served only to conceal the mysterious luminescence.

Yet, when the searchlights were again directed upward, that luminescence became more distinct and seemed to stretch to infinite distances on all sides. But it was still incalculably remote, and still filled us with alarm and foreboding. Whatever it was (and we could not help feeling that it was evil), we knew that it was a thing beyond the reach of all human experience; whatever it was, it was a monstrous thing, possibly malevolent and terrible, and not inconceivably ghostly and supernatural.

But as we continued to sink, I began to doubt whether any of us should live to solve the mystery. The air in our overcrowded compartments was becoming oppressively heavy and vitiated; we were like men locked in sealed vaults, and there was no possibility of renewing our exhausted oxygen supply. Already I was beginning to feel drowsy from the lack of air; my head was aching dully and I had almost ceased to care where we went or what befell us. Today, when I look back upon the racking events of those terrible hours, I feel sure that I was not far from delirium; and when I recall how some of my comrades reclined drunkenly on the floor, with half-hysterical mumblings and wailings, I am certain that there were but few of us, who retained our right senses.

There is, indeed, a blank space in my memory concerning what occurred at about this time; I may have fallen off into a doze or sodden slumber lasting for minutes or even for hours. I can only say that I have a recollection of coming abruptly to myself, as from a state of coma; and, with a sudden jolt of understanding, I realized where I was, and observed with a shock that half a dozen of my comrades were gathered together in a little group, pointing downward with excited exclamations.

Staggering to my feet, I joined them, and in a moment shared in their agitation. The lights beneath us were now far brighter—they no longer formed a vague shimmering screen, but were concentrated brilliantly in a score of golden globes of the apparent size of the sun. “Could it be that the ocean too has its suns?” I asked myself, as when one asks dazed questions in a dream. And looking at those spectral lights that wavered and gleamed through the pale translucent waters, I felt that this was surely but a nightmare from which I should soon awaken. Fantastic fish, with triangular glowing red heads and searchlight [297]eyes projected on slender tubes, darted before our windows in innumerable schools; but these seemed almost familiar now by comparison with those eerie golden lights below; and it was upon the golden illumination that my gaze was riveted as we settled slowly down and down. Soon it became apparent that the great central globes were not the only source of the radiance, for smaller points of light gradually became visible, some of them moving, actually moving as though borne by living hands!—and even the spaces between the lights seemed to wear an increasing golden luster! Yet with the golden was mingled a singular tinge of green, a green that seemed scarcely of the waters; and the mysterious depths were no longer black, but olive-hued, as though the light came filtering to us through some solid dark-green medium.

But a more imminent peril was to distract our attention from the weird lights. For some minutes I had been vaguely aware of something peculiar in the aspect of our compartment; yet, in my stupefied condition, I had not been able to determine just what was wrong. But full realization came to me when Stranahan, pointing upward, wide-eyed with horror, suddenly exclaimed, “Heaven preserve us, look at the ceiling!”

We all looked. The ceiling was bulging inches downward, as though the terrific pressure of the waters were already bursting the tough steel envelope of the X-111. And at the same time we observed that the deck we stood on was bulging upward, and that the bulkheads were being twisted and distorted like iron rails warped by an earthquake.

But now came the greatest surprise of all. “By all the saints and little devils!” burst forth the irrepressible Stranahan, pointing downward and forgetting the aspect of the bulkheads and deck. “There’s a city under the sea!”

“A city under the sea!” we echoed, in stupefied amazement. And from one corner of the room came a burst of hysterical laughter, which wavered and broke and then died out, sounding uncannily like a fiend’s derision.

“But I tell you, there is a city under the sea!” insisted Stranahan, noting the incredulous stares with which we regarded him. “The Lord strike me dead if I didn’t see its streets and houses!”

Though none of us doubted but that the Lord would indeed do as Stranahan suggested, we interpreted his remarks as mere delirious ravings, and continued to stare at him in petrified silence.

“You see, there she is!” persisted the seaman, still pointing downward regardless of our disbelief. And, crossing himself piously, he continued, in awed tones, “May the Virgin have pity on us, if that don’t look like a church!”

Stranahan’s last words had such a tone of conviction that, though our doubts were still strong, we could not forebear to look. And, after a single glance, our scepticism gave place to dumbfounded amazement. For was this not a city staring up at us from the green-golden depths? Or at least the ruins of what had been a city? In outlines wavy because of the dense, shifting waters, and yet as definite of form as reflections in a still pool, half a dozen great yellow-white temples seemed to glimmer beneath the brilliant lights, with massive columns, wide-reaching porticoes and colonnades, and gracefully curving arches and domes.

Was this but a mirage? we asked ourselves. Or [298]were these the remains of some submerged, ancient town? Never had we heard of mirages beneath the sea—but if this were a dead city, then why these vivid lights? And, certainly, no living city could be imagined in these profound watery abysses.

Even as we wondered, we seemed to note a gradual change in our movement. We were no longer sinking; we were drifting with slow motion, almost horizontally; and just beneath us appeared to be an impenetrable but transparent dense, greenish wall, a wall that—had the idea not been too preposterous—we might almost have imagined to be of glass. Beneath this wall gleamed no lantern-bearing, fishy eyes, but the dazzling golden orbs and the smaller scattered lights shone steadily with piercing radiance; and beneath us, at a distance that may have been five hundred feet and may have been a thousand, the vaults and domes and columns of innumerable stone edifices shone palely and with sallow luster. Surely, we thought, this was some unheard-of Athens, doomed long ago by tidal wave or volcano.

Gradually, for some reason that we could not quite explain, our horizontal motion seemed to be increasing; and, caught apparently by some rapid deep-sea current, we drifted with appreciable velocity above those dim realms of green and golden. Palace after magnificent palace, many seemingly modelled by architects of old Greece, went gliding by beneath us; countless statues, tall as the buildings, pointed up at us with hands that were uncannily life-like; wide avenue after wide avenue flashed by, and one or two colossal theatres of old Grecian design; but no living thing was to be seen, or, at least, so it seemed, for though we strained our eyes, we could discern only shadows moving in those uncertain depths, only shadows and an occasional firefly light which zigzagged fitfully among the buildings and which we took to be some strange illuminated finny thing.

Then suddenly, for no apparent reason, fresh terror seized us. Perhaps it was because we realized abruptly the full eerie horror of floating thus above a city of the dead; perhaps it was that the whole unspeakable ghastliness of the adventure had again flashed upon us. Be that as it may, we began to shake and shiver once more as though in the grip of a mastering emotion, or as though obsessed by forethought of approaching disaster; and muttered prayers again were heard, and more than one silent tear was shed.

But the time for tears and prayers was over. Our motion, gradually increasing for some minutes, was suddenly accelerated as if by some gigantic prod; we seemed caught in some mighty movement of the waters, some maelstrom that whirled us about and buffeted us like a feather; a hoarse, continuous thunder dinned in our ears, and we went shooting forward with prodigious speed. Then came a violent jerk, and we found ourselves tossed pellmell to all corners of the room; then another jerk, and we were flung back again like dice shaken in a box; then still another jerk, more vehement than the others, and our terrorized minds lost track of events as our vessel lunged and heaved, then veered and stood almost on end, then began to spin round and round, like a swift gyrating top ... And in that whirling confusion our senses reeled and grew blurred, and darkness came clouding back, darkness and sleep and nothingness ...

How any of us chanced to survive is more than I can say. In the turbulence and vertigo of that last blind roaring moment, I had vaguely felt that we had reached the end of all things; hence it was almost with surprise that I found myself hazily regaining consciousness, and discovered that I could still move my limbs and open my eyes. At first, indeed, I had the dim sense that I was dead and embarking upon the Afterlife; and it was only the definite sensation of pain in my bruised arms and legs, and the definite sight of my comrades tumbled about in ungainly attitudes, which convinced me that I was still on the better known side of the grave.

“Sure, and I thought we went through the very gates of Hell!” came a familiar voice; and Stranahan rose unsteadily to his feet, lugubriously nursing a sprained wrist. “By all the saints in heaven, we must be a devilish lot! The devil himself didn’t seem able to get us!”

Cheered by sound of a human voice, I followed Stranahan’s example, and slowly and painfully arose. I was thankful to learn that, although badly battered, I had suffered no broken bones; and as my comrades one by one staggered up from the deck, I was glad to observe that none were gravely injured.

Our vessel had assumed a horizontal position again, but I felt that our surroundings were strangely altered. While a pale luminescence seemed to transfuse the waters on both sides and above us, yet below us the golden lights were no longer visible, and everything seemed impenetrably black.

Of course, the Captain again ordered the searchlights turned on—and this time with extraordinary results. Just beneath us, actually in contact with the bottom of the X-111, a flat, sandy reach of ground was visible—certainly, the bottom of the sea! But this fact was the least remarkable of all. On both sides of us, at distances possibly of two hundred yards, a high and geometrically regular embankment shot up precipitously, ending in a yellow illuminated patch of water whose nature we could scarcely surmise. The one thing apparent was that we were in a submarine channel, a sort of river bed in the bottom of the sea. This fact was made evident by a current which sent us skimming along the soft sands although our engines had long since ceased to supply us with power.

“I can’t understand it!” sighed Captain Gavison, shaking his head dolefully. “I can’t understand it at all! For twenty-five years I’ve studied the ocean currents, but I’ve never before heard of anything like this!”

Just at this point our searchlights showed us a long, lithe dark form gliding rapidly by through the waters perhaps fifty feet above. It was as large as the largest known shark, but was shaped like no fish I had ever seen, tapering to a slender, canoe-like point at both ends; and, as it passed, the water seemed to foam and bubble strangely in its wake.

“Perdition take me, if it ain’t a sea dragon!” ventured Stranahan, who had to have his say.

“Stranahan, be silent!” snapped the Captain, in high irritation. “You’re always saying the wrong thing at the wrong time!”

“Yes, sir,” admitted Stranahan, meekly, a grave expression in his pale blue eyes.

“If you want to make yourself useful, Stranahan,” continued the Captain severely, although with less asperity than before, “go forward, and find out how far we are beneath sea level.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” agreed Stranahan, remembering to salute.

“How far below were we at the last reading, sir?” I inquired of the Captain, after Stranahan had vanished through the small compartment door.

[299]

“Thirty-seven hundred feet,” returned the officer, abruptly. “But we’ve sunk considerably since then.”

It was at this juncture that Stranahan reappeared in the doorway, a stare of blank, incredulous astonishment on his lean, hardened face.

“Well?” the Captain demanded. “How far below are we now?”

Stranahan mopped his brow as if to wipe off an invisible perspiration. But he answered not a word.

“Stranahan,” growled the exasperated officer, somewhat after the manner of a schoolma’am to an unruly pupil, “do you hear me? I’m asking to know how far below we are now.”

“Well, sir,” drawled Stranahan, saluting mechanically, “wouldn’t I be telling you if I knew? But, saints in heaven, sir, that machine must be bewitched! Else I’m seeing things!”

“Didn’t you notice the reading?” bawled the Captain.

“Yes, sir,” Stranahan replied, humbly. “That’s what the trouble is, sir.”

“Then how far below are we?”

Stranahan hesitated as though he would rather not speak. “Forty-four feet,” he muttered, at length.

A murmur of suppressed excitement passed from end to end of the room. “Forty-four feet!” yelled the Captain. “You mean forty-four hundred!”

“No, sir,” maintained Stranahan, quietly. “I mean forty-four.”

The Captain’s anger became uncontrollable. “Stranahan, you must take me for a fool!” he shouted. “This is not the moment for practical jokes! At any other time I’d have you thrown in the brig!”

“But, sir——” Stranahan started to protest.

“That’s enough!” roared the officer, fairly shaking with fury. And, turning to one of the younger men, he commanded, “Ripley, see how far below water level we are!”

“Aye, aye, sir,” assented Ripley, and left the room.

A moment later he returned with a sheepish grin on his face.

“Well, how far below are we?” demanded the Captain.

But Ripley, like Stranahan, seemed reluctant to speak. He coughed, gasped, stammered out an unintelligible syllable or two, cleared his throat, stood gaping at us stupidly while we looked on expectantly, and finally blurted out, “Forty—— forty-three feet, sir!”

“Forty-three feet!” bellowed the Captain. “Has the whole crew gone crazy?”

And, without further ado, Gavison himself went lunging toward the door, and disappeared in the forward compartment.

It was several minutes before he returned. But when he rejoined us, his face wore a look of undisguised amazement. Furtively and almost shamefacedly he peered at us, like one who fancies he is losing his wits.

“Well, sir, how far below are we now?” I questioned.

The Captain cleared his throat, and hesitated perceptibly before replying. “I—— I really don’t know. I can’t understand—— I can’t understand it at all. If the instruments aren’t out of order, we’re exactly forty-two feet below!”

I gasped stupidly; then suggested, “No doubt, sir, the instruments are out of order.”

“They are not!” denied the Captain. “I’ve tested them!”

Again the Captain hesitated briefly; then abruptly he resumed, “Besides, as you know, there are two instruments. They both record forty-two feet. Surely, they can’t both be wrong in exactly the same way.”

There ensued a moment of silence, during which we stared dully at one another, filled with mute questionings we would not dare to put into words.

“But how do you explain——” I at length started to inquire.

“I don’t explain at all!” interrupted the officer. “We’re simply running counter to all natural laws! According to all estimates, we should be nearly a mile deep by now!”

And the Captain stood stroking his chin in grave perplexity. Then turning suddenly to us all, he remarked, “I can’t see how it can be true, boys; but if we’re only forty-two feet deep, then maybe the engines will have life enough in them to pull us out. At least, it’s a chance worth taking.”

Half an hour later, after a few instructions and the assignment of the crew to duty, we had the pleasure of hearing once more the churning and throbbing of the engines. At first it promised to be a barren pleasure indeed, for the abused machinery gasped and sputtered as though determined upon a permanent strike; but finally after many vain efforts, we were greeted by the continuous buzzing of the motors. Then we found ourselves slowly moving, at first scarcely faster than the current, but with gradually increasing velocity; and by degrees we felt the deck taking on an upward slope as the nose of the vessel was pointed toward the surface of the waters. It was not an easy pull, for our three flooded compartments were powerfully inclined to hold us to the bottom; and in the beginning we made very little progress; several times we felt our hull scraping the ocean floor. Eventually, the engines, waxing to their full power, began to cleave the water at gratifying speed, and we found that we were moving definitely, though slowly upward.

Of course, hope came to us then in a powerful wave, accompanied by black flashes of despair, for what if impassable thousands of feet of water still rolled above us? Impatiently we fastened our eyes on the pressure gauges, and impatiently watched the registered distance dwindle from forty feet to thirty-five, from thirty-five to thirty, from thirty to twenty-five, and from twenty-five to twenty! And now, in a sudden wild burst of joy, we realized that probably we were saved! A pale but unmistakable radiance was seeping in through the glass ports, a radiance far more distinct and reassuring than the eerie luminescence we had noticed before. Certainly, this was the sunlight—and in a few moments we might bask again in the warmth of day!

And as we rose from twenty feet to fifteen, and from fifteen to ten, our hopes found increasing fuel. The light filtering in through the windows brightened at a rate that was more than heartening—and through the clear waters, even without the aid of the searchlights, we could distinguish a steep embankment, perhaps fifty or a hundred yards away. And just above us, almost within grasping distance, we thought we could notice the line where water met air!

But we had no intimation of the surprise that lay in store for us. Today, as I look back upon those events with clear perspective, it seems incredible to me that we could actually have expected to escape at once to the upper world. But hope had doubtless blinded our eyes and suffering blunted our perceptions, so that we could not understand that we were at the beginning, rather than at the end of our adventures.

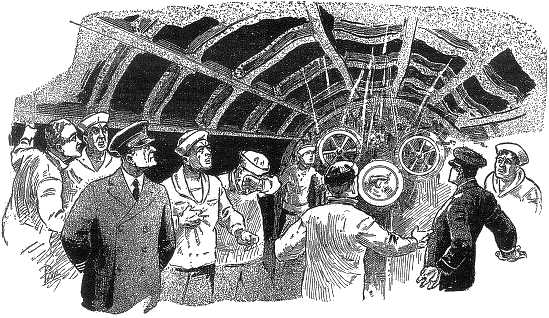

Suddenly, with a furious lunge and an unwonted, violent burst of speed, we found ourselves [300]launched upward toward the wavy, light-shot level that was our goal; and now a blinding brilliance was upon us, and for a moment we had to shade our eyes to shield them from the dazzling change. Then, when by degrees we were able to glance again about us, we found that we were on the surface of the waters, actually on the surface!—but where was this that we had come up? and in what strange and unmapped continent? There was scarcely one of us that could suppress a cry of astonishment—we were afloat, not upon the ocean, as we had expected, but rather on a wide and rapidly flowing river—a river that washed no shores, ever described by human tongue! Altogether, it was one of the weirdest and most magnificent lands imaginable; on both sides of the stream spread a flat plain, dotted with great sea shells and greenish boulders, which in their turn were interspersed with a mossy brown vegetation and pale, graceful flowers like waterlilies on solitary stalks. At measured intervals, as far as the eye could reach, were colossal stone columns, enriched with pastel tintings of pink and blue; and these shot upward hundreds of feet as though supporting some titanic dome, ending, unaccountably, in a dark, green sky from which glared several sun-like, golden orbs, which suffused the scene in a mellow, unearthly luster that was beautiful, yet terrifying and ghostly.

Rubbing our eyes, like children still not half awake, we gazed at this fantastic, lovely spectacle. Not a word did we speak; we could not have found language to voice our amazement. Only the Captain, out of the whole thirty-nine of us, retained some measure of self-possession; and though, as he afterwards confessed, he was so dazzled that he spoke and acted mechanically, he did retain the presence of mind to order our vessel steered to shore and anchored.

It is still a marvel to me that we had the energy to carry out these commands. Somehow we brought the X-111 to land; and somehow, after several false starts, we managed to moor the ship to a large boulder in a sort of miniature bay.

And then Stranahan proved again that he possessed an original mind. Not only was he the first to force himself out of the opening door of the submarine, but he carried out a large American flag, which he planted in the ground among the brown weeds between the boulders, while with sedate and ceremonious gestures, he proclaimed, “In the name of the United States of America, I take possession of this land!”

But the rest of us gave no heed to his words. We were taking deep, refreshing breaths of the pure, clean air, which came to us almost like a mercy from heaven after the suffocating atmosphere of the submarine. And before we had had half the needed time to revive our starving lungs, an astounding phenomenon, as unexpected as the very discovery of this spectral region, was to drive Stranahan from our thoughts at the same time that it flooded our minds with terror. For the golden lights above suddenly flickered, gave out a fugitive spark or two, and with meteor swiftness went out. We found ourselves mantled in a starless and impenetrable blackness, more mysterious and dreadful than the loneliest watery abysses from which we had just escaped.

No sooner was the darkness complete than it seemed to be populated with all manner of weird and terrible things. The disappearance of the light seemed to be the signal for the approach of a host of evil monsters. A chorus of hoarse, unearthly voices, loud as the bellowing of a bull, resounded about us in a deep, continuous bass; and throaty gruntings and savage snorts and howlings echoed and droned as though they issued from ten thousand pairs of giant lungs. Dazed with horror, we stared into the unbroken gloom like doomed men; I had visions of colossal eyes smoldering from the blackness, and jaws that struck and tore, and gnashing teeth that rent and shattered.

But it was not a moment before our dumbfounded inaction was over. Pellmell we flung ourselves toward the submarine, almost failing to find it in the darkness, and tumbling tumultuously over one another in our haste to crowd through the narrow door. Several of the men were shoved accidentally into the water, and Stranahan came in dripping from an unexpected swim; while the Captain walked with a slight limp, newly acquired.

At length, however, we were all safely within the ship, and the doors were barred against the unknown peril. Several of the men, still trembling with terror, were eager to get under way directly; but this idea the Captain emphatically vetoed, declaring that the X-111 was no longer seaworthy. All that we could do now was to try to locate the danger with our searchlights; and accordingly, we wasted no time before switching on our powerful lanterns and revolving them in slow circles that illumined by turns every inch of the boulder-strewn, weedy plain. All in vain. Although the unearthly chorus could be heard even through the closed doors and showed no sign of diminishing, our searchlights revealed nothing that we had not already seen.

For some time we watched and waited—but nothing happened. And at length, turning to us all with a smile, the Captain advised, “Well, boys, we’ve all had a pretty hard time of it. Suppose we just forget about that racket out there and try to take a little rest.”

We were all glad enough to follow the Captain’s suggestion. Several of the men were commissioned to take turns standing watch; and the rest of us were not long in seeking much needed sleep. Within a few minutes, the deep and regular breathing from the nearby bunks informed me that my companions had temporarily forgotten the day’s adventures.

For my own part, exhausted as I was, I could not so readily find relief. The events not only of the past few hours, but of many months, came trooping before my mind in continuous blurred procession; I was obsessed by my own imaginings, and from a dim half-consciousness, I would awaken time after time to a vivid re-experiencing of some almost forgotten episode. And, strangely enough, my reveries were concerned mainly with a single phase of my life—the phase I was now living. My youth and early manhood might almost not have existed, for all that I remembered of them now; but I did sharply recall how, at the outbreak of war more than a year ago, I had decided abruptly upon the action that had plunged me into my present plight. Resigning my position at Northeastern University, where I had been serving as instructor in classic Greek, I had enlisted in the navy, and had promptly been sent to an officers’ training school, from which I had emerged as Ensign. Friends had commended me upon my patriotism, yet it was not patriotism, but rather the greed for adventure, that had motivated my decision; and now, as I looked back, it seemed ironic to me that my previous uneventful days had been so much more pleasant than any of my adventures. There was, [301]however, one factor which had served to make those days enjoyable, a factor without which even the most active life would be barren indeed—and that factor was one which could have no place in wartime. Frequently, as I tossed and struggled fitfully on my narrow bunk, there flashed before me out of the darkness the blue eyes and laughing face of one whom I could scarcely recall without a pang; and I lived again with Alma Huntley those sparkling days among the Vermont hills, when she was to me all that life was, and I won her promise of devotion among the scented pines and to the music of rippling waters ... That day was long past, yet how actually it came back to mind! And how acutely memory brought back a later day, when her cheeks were moist and I held her in a minute-long embrace, and mutual vows and soft murmurings were exchanged, and then there came the sharpness of “Farewell!” and she was gone, lost amid a blur of faces, and I marched sedately on while the world was blotted out in loneliness and grief ... Oh, why had I left her, plunging thus among these unknown horrors?... Fervently, as I lay there listening to the uncanny bellowings from the ghostly world without, I longed to reach out my arms to her, to hold her warmly, to speak to her, and to hear her speak, if only one loved word....

But even the most intense yearning may be blotted out by sleep. And at last, after hours, I lost my memories in unconsciousness—an intermittent unconsciousness, broken by disturbed dreams and vague images of death and disaster....

I opened my eyes to find a bright, golden light pouring in through the unshuttered windows. Surprised, I leapt to my feet, and discovered that the great mysterious golden orbs were shining as before from far above, the boulder-strewn plain glimmered as clearly as at first, the massive columns were still fairy-like in their tints of pale pink and blue, while the hideous bestial noises had unaccountably ceased.

Hastily I dressed and rejoined my companions. I found them gathered about in a little circle, earnestly talking; and they welcomed me gladly into their discussion, the subject of which I at once surmised. For what but our mysterious plight could now occupy our minds and tongues? None of us, as yet, had more than the faintest inkling of where we were or what had befallen us. That we were in some sort of cavern beneath the sea was the belief of the Captain and several of the men, but this region seemed so oddly unlike a cavern that the explanation was not generally accepted; and the more superstitious were inclined to hold that we had been bewitched into some sort of supernatural, goblin realm. For my own part, I could hardly understand how we could be in a submarine cavern without being completely flooded; and much less could I understand how we could be in any known land above seas.

Obviously, the only likely source of information was through exploration. And since it was not possible to conduct any explorations with the aid of the disabled X-111, the Captain took the only other available course—which was to order some of the men to set forth into the Unknown on foot, determine the lay of the land and return as soon as possible with whatever tidings they might gather.

Stangale and Howlett, being the most experienced veterans, were selected to make the initial attempt. In a few minutes, they set off cheerfully together, equipped with firearms and a day’s supply of food and drink, with instructions to return within twenty-four hours at the latest.

Twelve or fifteen hours went by while we waited impatiently; the great golden orbs flashed out as mysteriously as before, and for eight or ten hours we slept; then, upon awakening, we found the lights still shining as brightly as ever, and noted that it was time for the return of our two scouts. We watched in vain for their arrival. Not a moving thing greeted us from the unchanging, bouldery plain; hours went by; excited speculation gave way to more excited speculation, and wild rumor to still wilder rumor; the suspense became tantalizing, and yet there was nothing to do but wait. Had the men lost their way? or had they met with some disastrous adventure? or had the savage inhabitants of these wild realms seized and imprisoned them? To these questions there was no answer, though many were the conjectures. When the darkness had fallen upon us once again, and once again we had slept and awakened to find the golden light restored, we knew that it was time to set out in search of the missing ones.

This time the Captain called for volunteers to invade the Unknown, which, as he warned us, might be dangerous beyond all expectations; and after half the crew had offered themselves for the adventure, his choice fell upon Ripley and Stranahan.

It was with genuine regret that I watched these two gallant seamen set forth amid the reeds by the river’s brink, to disappear at length among the boulders and behind the great stone columns. Somehow, as I lost sight of them, I had a sense that we might not see them again so soon. I was sad as though with a forewarning of disaster; and, as I reflected upon the pitfalls and dangers they might have to face, I experienced more than one twinge of vicarious fear.

Worst of all, my misgivings seemed to be justified by time. Twelve hours passed, and the explorers had not returned; twenty-four hours, and there was still no word from them, though they had been given explicit orders to be back. With grim, set eyes, the Captain stood alone by the river bank, gazing sternly into that wilderness which had already engulfed four of his men; and the rest of the crew stood chattering fearfully among themselves, declaring that this land was “haunted,” “spooky,” and “thick with devils.”

It was curious to note how, in these weird, unknown domains, outworn superstitions were being reborn; how ready the men were to believe in goblins, dragons, sea serpents, werewolves and all manner of fantastic monsters. Even the more enlightened of us seemed about to forget all that civilization had taught us; and, in the failure of all that we had been accustomed to cling to, we were clutching at a savage, terrorizing faith in incredible and ghostly things.

By the time that Stranahan and Ripley had been absent forty-eight hours, the crew was in a state of impatience verging upon madness. The fluttering of a feather would have sent them scampering like frightened horses; the buzzing of a bee might have been the signal for spasms of dread. On one occasion, indeed, the chirping of some cricket-like insect did put half a dozen of the men into a panic; and on another occasion three or four of them turned pale merely upon hearing the swishing and flapping of a small fish in the river.

It was when the excitement was nearing its highest that the Captain called once more for volunteers to search for the missing men. But so deep-rooted and paralyzing was the general alarm that only two of us offered our names—young Phil Rawson and myself. I do not know what strange wave of courage had suddenly emboldened this timorous recruit while less callow men held back. For my own part, I must admit [302]that I volunteered from the mere desire to escape from ennui and the half-frenzied rabble of my comrades. But, whatever our motives, we were promptly to be launched into adventures that were not only to test our hardihood, but to prove interesting beyond anything we could have imagined.

Rawson and I had been gone not half an hour when the aspect of the country began suddenly to change. It was as though we had passed some indistinguishable boundary, for the boulders were rapidly becoming less numerous, and at length disappeared entirely, while at the same time the odd, mossy vegetation became astonishingly rich and profuse. Or, to be precise, it gave place to a different vegetation entirely, an unearthly vegetation, almost too strange for belief. At the risk of being accused of fabrication, I must describe those incredible plants: the creepers with long leaves of lace-like brown, which twined in dainty wreaths and veils about the olive-green boles of limbless trees, the bushes, shaped like starfishes, and of the hue of dried grass, with diaphanous flowers that a breath might have blown away; the cinnamon-brown reeds that rose to double a man’s height, ending in a profusion of cucumber-shaped fruits; the peculiar, abundant growth that looked at a distance like a great earthen jar, but proved upon closer examination to be the hollow container of a species of milk-white down that grew in long and silken strands like untended hair.

So dense was the foliage that we would not have been able to force our way through it, and would not have dared to make the attempt, had it not been for a sharply cut path which wound in leisurely curves and undulations close to the river’s brink. It was not like one of those paths which nature occasionally plans, or which are due to the tracks of wild beasts, for it had a regularity of design and an evenness of width that proved it to be unmistakably the work of man. Yet what man could have penetrated before us into these uncanny sunless depths? At the mere thought that others might have preceded us we involuntarily shuddered; we were half convinced that we were intruders into a tomb closed ages ago. But despite this conviction, we kept a constant, half-terrified outlook for sign of human presence.

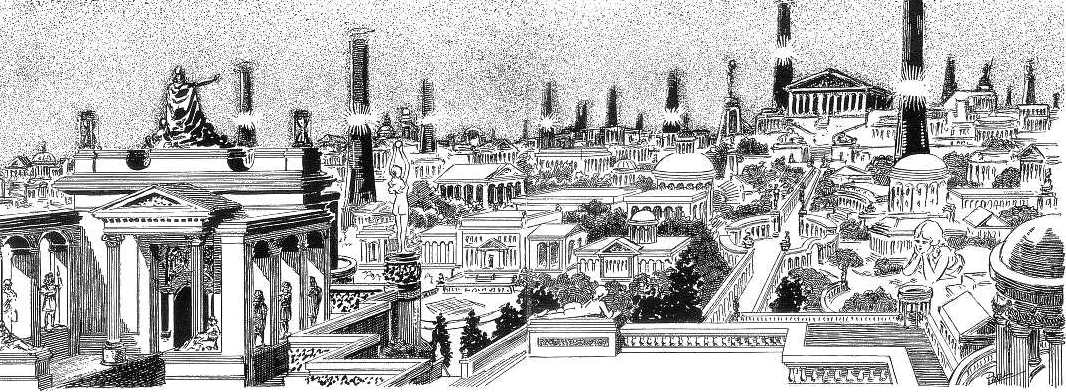

It was not long before our vigilance was rewarded. Abruptly the path before us widened, until it was of the size of a broad highway; and above the dense masses of vegetation, we beheld in astonishment the looming marble pillars of a Grecian colonnade. Toward this the road led in long and graceful curves; and it was but a few minutes before we found ourselves at the entrance of a covered walk or “stoa” that brought back to me vivid memories of “the glory that was Greece.” On both sides of us the palely-tinted Ionic columns rose to a majestic height, daintily ornamented at the base with the acanthus design, and curving in symmetrical proportions that brought to mind the perfection of the Parthenon; while the marble floor on which we walked and the marble ceiling above us were frescoed with figures that seemed drawn bodily from the romance of the ancient world. They were not wholly Greek. I knew these pictures of sportive mermaids and lightning-hurling gods and dragon-slaying heroes and misty caves of twilight and the throbbing lyre; but there was something suggestively Greek about them all; and steeped as I was in the lore of ancient Hellas, I had the singular feeling that the hand of time had been turned backward two thousand years or more.

[303]

This feeling was accentuated when, having followed the covered walk for a distance of several hundred yards, I observed that it led to a magnificent, many-columned edifice which could pass for nothing if not for a temple of the ancient gods. It was a structure of solid marble, white marble artistically varied with veilings of black; its pillars were massive as the trunks of the giant redwoods I had seen in the California forests years before, and like those redwoods, produced an effect of solemnity and awe; but all was so perfectly designed and proportioned that, while the building occupied an area perhaps as large as the average city block, it gave an effect less of magnitude than of artistic completeness and beauty. No living thing was visible about the precincts of this amazing temple, nor would I have expected any living thing in what I had come subconsciously to regard as a realm of the dead; but I was overawed at thought of this abandoned loveliness, and paused at some distance to regard it reflectively, mentally asking whether it was some still undiscovered survival from classical times or whether I was but seeing a vision.

A suppressed exclamation from young Rawson brought me back to reality—or, at least, to the unbelievable thing that passed for reality. In the very center of the swift-rolling river, the banks of which paralleled the colonnade at a distance of a dozen paces, I observed a low-lying, gliding form, gracefully elevated at both extremes, which at the first terrified glimpse I took to be some fabulous monster, but which I soon recognized as some sort of boat or canoe. Before I had had time for a half-composed glance at it, it had gone speeding out of view; but in its fast-moving frame, I thought I could distinguish half a dozen dusky bobbing shapes, and half a dozen pairs of oars that reached out rhythmically, and noiselessly clove the dark waters. Later, when I had had time for reflection, I was to recognize this strange craft as akin to the shadowy apparition, the unknown sea monster which had so terrified us in the submarine; but at present I was overwhelmed by the knowledge that this weird place was actually peopled, peopled by living men whom at any moment we might meet face to face!

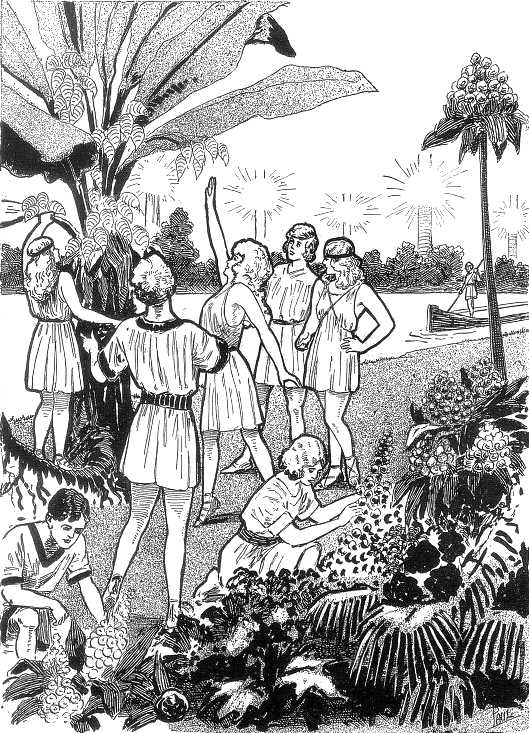

We had scarcely recovered from this surprise when an even greater surprise flashed upon us. Out of the windows of the temple, which we had believed long closed to human sound, a strange, thin music began to float, serenely beautiful and of elfin remoteness and charm.... And while, entranced, we listened to those magical strains, there came the fluttering of a butterfly gown, and from the temple doors issued a shimmering, dancing form, followed by a score of other dancing, shimmering forms—scarcely human, we believed, so ethereal did they seem in the flashing and waving of arms, the swift rhythm of feet, and the play and interplay of pale blue and gold and pink and lavender and white from their flowing and multi-colored robes. A singular iridescence seemed to overspread them, almost a halo such as may envisage a goddess; and, gaping and enthralled, we gazed on them as men might gaze on Venus were she to return to earth. Now down the long colonnade they started, tripping toward us with birdlike gestures and the airy unreality of perfect time and movement; and, fearful to disturb the vision by our gross presence, we hid ourselves behind the great stone columns, peeping out furtively as though they might vanish bubble-like at our gaze. But, apparently absorbed in their dance, they continued gracefully toward us, not glancing to right or to left, and catching no hint of our intrusion—until, as the procession drew more near and the charm of the music more compelling, I peered out too incautiously from behind my marble bulwark, and found myself staring full into the face of the most ravishingly beautiful woman I had ever beheld. There was a quality about her face that seemed to mark it as not of the earth, the Madonnas of old paintings have something of that look; and the most perfect womanly bust that sculptor has ever conceived; but there was also a vividness and an animation that no mere painting or statue has ever shared, together with an air of such innocence, such candor and kindliness of soul that, had I been a believer in angels, I might have gone down straightway upon my knees.

But all this I beheld in the space between two heartbeats. Even as the vision greeted me it vanished; the beautiful clear eyes were distended with terror upon their first contact with mine; there came a scream of fright, followed by a chorus of screams; then a scurrying of fast-retreating feet, and the bright, fairy-like shapes had vanished; and the empty river flowed silently past the empty colonnade and temple.

The next few hours showed us a continuous amazing panorama. The marble temple proved to be but one of a series connected by long and graceful colonnades; and in the central structures, the Ionic and Doric architecture were curiously mingled with a type that seemed scarcely Grecian at all, since it admitted of all variety of arches and curves unknown to the builders of classical Hellas. Most remarkable of all, perhaps, were the gorgeously ornamented vases—some of them six or eight feet in height—which were of a style akin to those excavated from the ruins of old Ilium. But what caught my eye even more strikingly were the statues that occasionally appeared in niches along the marble galleries or in alcoves of the temples—statues that would surely not have been unworthy of a Praxiteles, since even Praxiteles could not have surpassed the symmetry of form and the unstrained reality of pose and expression with which these unknown artists had depicted their wrestling heroes and dancing fauns and stern-browed old men and queenly maidens and gracious youths. For one who had been nurtured on modern art, these busts and marbles were as old paintings would be to him who had known only sketches in black and white; there was none of that snowy coldness or bronze severity of hue which are so common in sculpture today, but all of the statues had been skilfully tinted with the complexion of life, and such was the verisimilitude, that several times I started in surprise on beholding what I took to be a living man but which proved to be only an image of stone. I was interested, moreover, to note that none of the sculptured features had that peculiar hardness and selfish keenness so common among the men I had known, but that all seemed suffused with a clear and tranquil spirituality; and every lyric impulse within me was awakened when I observed on many of the faces of the women that same unearthly Madonna look which had graced the butterfly-gowned dancing maiden.

But, of course, Rawson and I did not allow our pleasure in the statuary to keep our minds from more vital subjects. Above all, we maintained a constant lookout for the inhabitants of these queer regions, for we could no longer suppress the suspicion that unseen furtive eyes were peeping out at us from behind every pillar and wall. For my own part, I had more [304]than one qualm that I did not care to admit, and secretly wished myself back on the X-111; and as for Rawson—I found that youth afflicted with far too much imagination for an adventurer, and repeatedly begged him to keep his fantastic fears to himself.

But there was no repressing the excitable young Rawson. When he was not drawing pictures of the serpents and wild beasts that probably infested the thickets beside the temples, he would be diverting me with the most grewsome ghost stories I had ever heard; and he went so far as to suggest that the dancing girls had been only airy apparitions, while the brilliant golden lights above us had no more reality than a will-o’-the-wisp. Evidently he had been too much nurtured on fiction of the blood-and-terror variety, for only a devotee of the most hectic adventure tales could have imagined, as he did, that our pathway was beset with robbers’ lairs, pirates’ dens, scorpions and crocodiles, head-hunting cannibals, siren women luring us to destruction, and murderous desperadoes of a thousand ilks and guilds.

Fortunately for my peace of mind, I heard not half of Rawson’s ravings, for my interest in the wayside architecture served as a distraction. For two or three hours I was occupied with inspecting the gracefully connecting galleries of five or six temples; and, having passed the last of the group, I was absorbed in my observations of a long, marble colonnade which extended apparently for miles in a straight line amid the gray and brown fantastic vegetation.

And now it was that I made the most startling discovery of the day. At intervals along the floor of the colonnade, which was of a red and yellow mosaic of baked and hardened clay, appeared deeply-graven inscriptions which I paused eagerly to survey. At first I thought that they were in no known language, but it was not long before I had detected a certain resemblance between the characters and those of the ancient Greek. Profiting from my collegiate study of that tongue, I puzzled over the words while Rawson stood by impatiently urging me to be off; and one by one I succeeded in identifying the letters with those of the Greek alphabet! Not every one of the characters, it is true, could be recognized with assurance, but enough of them were unmistakably Greek to give me a clue to the whole; and at length I found myself making a translation that might solve the entire mystery of this extraordinary land.

But the process was a slow and plodding one, and I did not make the progress I had expected. Even though the letters were clear enough, the meaning of the words was not. Evidently this was not the Greek of Plato or Thucydides, in which I had been thoroughly schooled; but rather it was a language that was to classical Greek what Chaucer is to modern English. Still, I was not completely discouraged, for I did manage to make out an occasional word, though not at first enough to give meaning to any passage. All in all, considering the limited time at my disposal, my efforts seemed futile; and I was about to yield to Rawson’s importunities and give up this diverting study for further exploration, when suddenly I made a successful discovery. I must have come upon a passage simpler than the rest, for unexpectedly half a sentence flashed upon me with clear-cut meaning at once so striking and so enigmatical that I stopped short with a little cry of surprise.

“Placed here in the year Three Thousand of the Submergence,” ran the words, which occurred in large lettering at the base of a statue of a strong man trampling down the ruins of what looked like a steel building. “Placed here ...” at this point were several words that I could not make out—“in celebration of the Good Destruction.”

“In celebration of the Good Destruction!” I repeated, after translating the words aloud. “Sounds as if written by a madman!”

“Maybe you didn’t read it right,” commented Rawson.

This suggestion, of course, I ignored. “Wonder what the Submergence can mean,” I continued, meditatively. “That doesn’t seem to make sense, either.”

“No, it doesn’t,” Rawson admitted, with a thoughtful drawl. “Everything down here seems sort of topsy-turvy. Suppose we go on and see what else we can find out.”

I nodded a hesitating assent, and we proceeded on our way in silence. But, though we did not speak, our thoughts were active indeed, for more than ever I was convinced that somehow, unaccountably, we were amid the remains of a Grecian or pre-Grecian countryside. Had Socrates or the radiant Phobus himself stepped out of the grave to greet me, I would not have been surprised; and I more than half expected to catch a glimpse of Athena’s robe from behind the dark shrubbery, or to see the winged feet of Hermes or hear the clear notes of Pan.

But neither Pan nor Hermes nor any of their famed kindred presented themselves upon the scene. And after walking at a good pace for more than an hour along the marble colonnade, I forgot those interesting individuals in contemplation of a scene that left me gaping in greater astonishment than if I had invaded a council of the high Olympian gods. For some minutes a series of huge templed domes and columns, dimly visible through rifts in the vegetation, had attracted my attention and aroused Rawson’s misgivings; but neither of us had had any intimation of the sight that was to greet us when at length we came to the end of the colonnade.

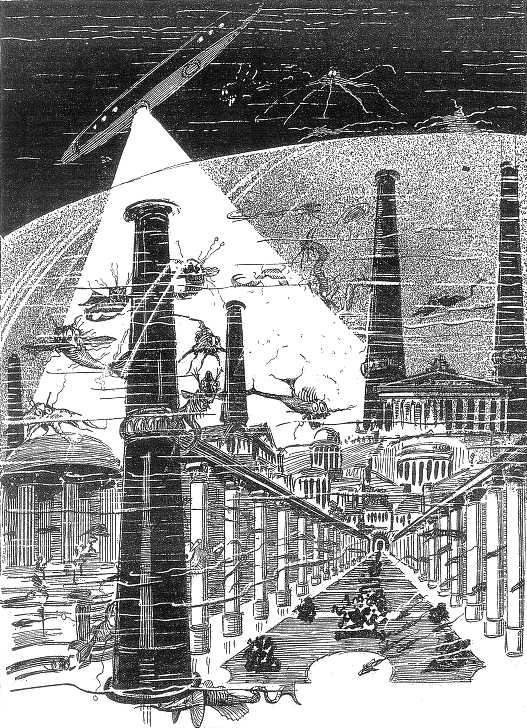

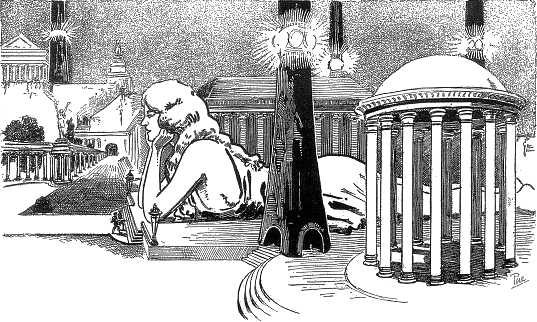

Suddenly we saw a clay road sloping down sharply beneath us, and found ourselves gazing out over a valley more dazzling than we had ever before known or imagined. Through its center flowed the great river, with gentle loops and twinings; above us, as before, reached the dark-green sky illumined with the golden suns; and an innumerable multitude of palely tinted columns, like the tree trunks of some colossal forest, shot upward to that sky as though to support it. But what were truly remarkable were the buildings that adorned the plain. On both sides of the river they stretched, far to the distance and out of sight, palaces of white marble and of black marble, of jade and of alabaster, some with an elegant symmetry of Greek columns, some with a solidity of masonry that seemed half Egyptian, some with an almost Oriental profusion of spires and turrets, of porticoes and balconies and arches and domes. But all alike were reared in perfect taste, and with perfect regard to the style of their neighbors; all alike faced on wide avenues, flowery lanes or lawny and statue-dotted parks; all appeared but parts of a single design which, when seen from above, was like some consummate tapestry patterned by a master artist.

As Rawson and I stood staring at this matchless scene, I suddenly recalled the steeples and towers of that city we had seen beneath us in the submarine. A strange similarity in the outlines of the buildings impressed itself upon me—then in a flash it came to me that the two cities were one and the same! And at that instant I shuddered, amazed and horrified at the abrupt solution of the mystery ... It was as the Captain had suggested; we were indeed beneath the [305]ocean, thousands of feet beneath the ocean, in some cavern inexplicably spared from the waters and haunted by the ghosts and relics of some ancient and vanished race!

Far from echoing the agitation I felt, Rawson seemed actually pleased at the turn of events. It piqued his imagination to think that we should be so far beneath the sea; and he conjured up all manner of alluring possibilities that testified more to his youth than to his common sense. He suggested that we were the discoverers of a great and magnificent empire which we should explore, conquer and then annex to the United States; and he formed his plans regardless of the probability that we should never see the United States again, and almost as though there were regular transportation facilities to the upper world. The sheer scientific difficulties—the apparent impossibility that a cavern free from water could exist beneath the ocean, the even more striking impossibility that human beings could inhabit such a cavern—seemed to make little impression upon the illogical mind of Rawson; and he was convinced that only by the rarest good fortune had we been entombed in these fantastic and dream-like depths.

So intense was his enthusiasm, that he urged me to descend at once with him to the many-templed city. But I did not willingly accede; I pointed out that it would be wiser to hasten back to the submarine, inform Captain Gavison of what we had seen, and return here—if we returned at all—in greater numbers than at present. Besides, as I reminded Rawson, the Captain had ordered us back within twenty-four hours; and, if we dallied, some mischance might delay us until too late.