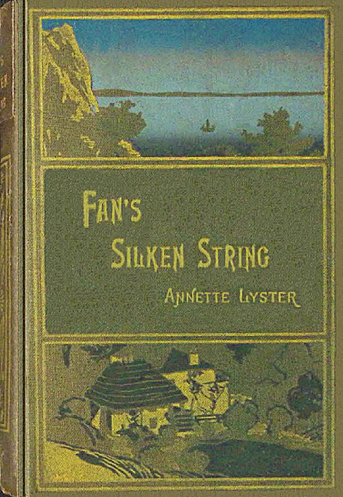

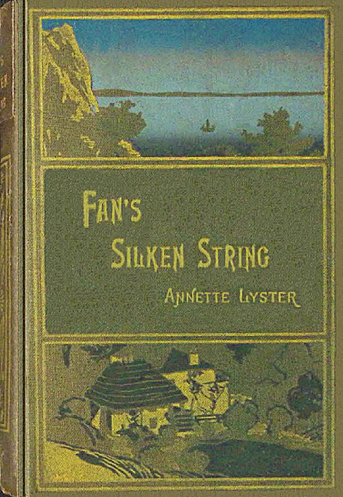

Title: Fan's silken string

Author: Annette Lyster

Release date: November 16, 2025 [eBook #77248]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1879

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

[Frontispiece.

"WILL YOU GIVE ME A DAY'S WORK, SIR?"

BY

ANNETTE LYSTER

—————————————

PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE COMMITTEE

OF GENERAL LITERATURE AND EDUCATION APPOINTED BY THE

SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE.

—————————————

LONDON:

SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE

NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE. W.C.;

43, QUEEN VICTORIA STREET. E.C.

BRIGHTON: 129, NORTH STREET.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

II. HOW BEN CARRIED OFF HIS SISTER

V. HOW BEN'S SIN FOUND HIM OUT

VII. HOW FAN SPUN A SECOND SILKEN THREAD

FAN'S SILKEN STRING

BEN FAIRFAX'S WALKING TOUR.

MANY years ago, on one of the loveliest of summer days—a day which seemed made on purpose to enable farmers to save their hay—there was a great haymaking going on in a large field belonging to a farm in one of the midland counties of England. It was so long ago that haymaking machines, if indeed they existed at all, were not common; and so that prettiest of country sights, a haymaking in the old style, was still to be seen.

A long irregular line of men and maidens, each armed with a fork or rake, passed slowly across the sunny field, gathering the hay into ridges, which looked not unlike the waves of the sea after a high wind, when they come in on the shore in long undulating swells, one after another. Then, the other side of the field being reached, the line turned and passed back again, this time leaving the ridges broken up into little haycocks. Ah, how pretty it was! The lumbering, rattling, awkward machine will never look half so pretty; and as I am not a farmer, bound to remember the reasons for preferring the machine (reasons which I know are many and good), I may perhaps be allowed to breathe a sigh for the beautiful past; for the fair sights and sweet scents, the human interest, which made the beauty of many a haymaking which I can remember; aye, and to pity those younger than myself, whose only notion of haymaking will be connected with a great, hideous, fussy, oily-smelling,—"useful" machine.

Well, to return to the hayfield in question.

It had been rather a wet summer so far. And although this was a glorious day, it did not look very settled, and the weather-wise, as represented by two aged men who had just walked down the lane to encourage the farmer by promising him more bad weather, were not very cheerful. And so the farmer, Mr. Heath, a stout, elderly man who was leaning over the gate watching his haymakers, was naturally anxious to get as many hands to work as he possibly could, and so save his hay before the rain came on again. Very likely, if good farmer Heath is still alive and still farming, he has a machine or two at work on such occasions, and considers it a great improvement.

He was just about to open the gate and go in to encourage his men and maidens to work hard, and perhaps to aid them in their task, when a voice behind him said—

"Will you give me a day's work, sir?"

The voice was rough and sharp, but the accent was not that of the part of the country to which farmer Heath belonged. And so when he turned to look at the speaker, he half expected to see a gentleman, who had made the inquiry in fun. However, what he did see was a ragged, stoutly built lad, with a tangle of curly fair hair, peeping out through the slits in a tattered straw hat, and a pair of very roguish-looking blue eyes, shining impertinently out of a good-looking, dirty face. The lad wore a faded blue shirt, and a pair of trousers so much too long for him that he had rolled them up half-way to his knee, and secured them with a highly ornamental piece of knotted rope. A leather belt kept his garments together, and on his arm he carried a coat which looked as if he must have robbed some unprotected scarecrow. He also carried a pair of strong, heavy shoes, comparatively new, and his well-formed feet were naked and dusty. But farmer Heath knew that this lad did not belong to that part of the country, and his appearance rather excited his suspicions, though he could not have said exactly why. He stared hard at the stranger, who awaited his leisure with great composure.

"A day's work, did you say?" asked farmer Heath, slowly.

"Yes, sir. I'm strong and active, and my work has been about horses, so I should know something about hay, too. And if you give me work, I think you'll be pleased with me."

"You don't think small beer o' yerself, young man."

"No more will you, sir, when you've giv' me a try and seen me at work," remarked the youth, with great coolness.

"What's your name, boy?"

"Ben Fairfax, sir."

"And where do you come from? Have you a good character from your last place?"

Ben Fairfax grinned broadly, showing a splendid set of white teeth. He had laid down the heavy shoes, in order to carry on this conversation more at his ease, but now he stooped and lifted them, saying as he did so—

"I've always heard tell that the folks hereabout were slow in their ways, but I couldn't have believed they was quite as slow as this here! Thirty acres of hay down—the sun shining splendid, and a nice breeze blowing—not hands enough to get it saved before night and the weather not to be depended on—and you stopping to ask questions of a stout fellow like me, as only asks for a day's work! No, sir, I've no character, good or bad. I never was in service at all. My father's a shoemaker, and he made these shoes. I don't belong to these parts."

"You're a free-spoken lad," said the farmer, severely.

"They mostly are, where I come from. I'm taking a walking tour for the good of my health, and I'd be glad of a job just now; I don't deny it. But I suppose I should have to get the Queen and Prince Albert to write a line for me, before 'you'd' believe that I wouldn't run off with a hay-fork in one pocket, and a rake in t'other."

Jokes were not plenty at the Lee farm, and this seemed to farmer Heath a most excellent joke. He burst into a hearty fit of laughter.

"You are a cheeky young monkey," he said; "and if I did right by you, I'd give you a hiding; but all the same, what you say about the weather is no more than the truth, and if you'll call it three-quarters of a day, you may go into the hayfield, if you like."

"All right, sir; I'm your man. I suppose my great-coat and Wellingtons will be safe, if I leave them here?"

"Your great-coat and Wellingtons," said the farmer, opening his eyes.

"That's what 'I' calls 'em. You can give 'em any name you like—'twon't alter 'em," replied the imperturbable Ben, as he rolled the thick shoes up in the ragged jacket, and put them in a corner near the gate.

He then followed his new employer, who was still grinning and chuckling over that joke about the line from the Queen. He led the way to where the haymakers were at work, and having provided Ben with a hay-fork, he desired him to "get to work, and let us see what you are made of."

Ben soon proved himself a strong, handy fellow. His sharp, saucy way of speaking amused the farmer. And as the fine weather lasted for several days (in spite of the cheerful prophets), he was allowed to remain among the labourers during the day. What became of him at night nobody inquired, but he had made himself very comfortable. He had contrived to creep into the stable loft through a window, to which he climbed by means of a great pear tree which was trained against the wall. And in this loft he slept, and also smoked his short, well-blackened pipe, regardless of the terrible risk he ran of setting fire to the hay.

By this time you will have decided that Ben Fairfax was not an exemplary member of society by any means; and truly, I fear, you are quite right. Yet there were excuses for poor Ben; and moreover, he was not "all" bad, as you will presently acknowledge.

He was the son of a shoemaker in a small village in Kent, not very far from London. He had learned a little shoemaking from his father, and a great deal of other things, not quite so innocent. He was a sharp, clever lad, and, for reasons of his own, his father was not desirous of his presence at home, as he grew older and more observant. So he got him a place as stable boy in the employment of Mr. B—, who had a great training stable not far from F— (the village where the Fairfaxes lived). It was not a place which any careful father would have chosen for his boy, but Ben's father was very far from being careful. The wages were good, and the boy could get home often; and if he did learn to swear and gamble and drink, ay, and to be dishonest and untruthful, it must be confessed that he could have learned it all quite as well at home.

At these stables, horses for racing and hunting were trained and kept for sale, and Ben, being fearless and active, was often selected by his master to ride such as required a light weight—a task in which the boy naturally delighted, and took great pride. In fact, he was in a fair way to get on in the world, when, unfortunately (or fortunately), he lost his place through a piece of most reckless carelessness. He and a younger lad, being entrusted with two valuable horses to exercise on the heath, finding themselves out of sight, had a race for their private diversion, and Ben's horse, a beautiful creature, worth many hundred pounds, got a bad fall, and was so much injured that he had to be destroyed. It then came out that Ben was in the habit of getting up races whenever an opportunity occurred, and he was at once dismissed in disgrace.

When he went home, his father beat him severely, and that not for having done wrong, but for being found out. Ben ran away from home the next morning, and swore that he would never return, nor see his father again. But there was a silken thread, one end of which was held by a very weak pair of small hands in that deserted home, while the other end was made fast somehow in his own wild heart; and this thread had drawn him home many a time already, and might do so again, let him wander as he would.

He had gone to London, where he spent what remained to him of his wages in amusing himself; and then, having by degrees parted with all his good clothes, he suddenly determined to leave off his foolish courses, and try his luck in the country. I would not be quite sure that the silken cord had nothing to do with this resolution.

It was pleasant weather, and there was no hardship for Ben in sleeping in the open air. He had a few shillings, and eked them out by what he called "picking up a meal" here and there, not always in the most scrupulously honest manner. However, he enjoyed his "walking tour" very much, and it ended in his falling in with farmer Heath.

While the haymaking lasted, Ben worked at that. And before it was over, the farmer had taken a fancy to the lad, who was so bright and quick, and gave him many a hearty laugh. "London Ben," as they called him, was, indeed, a general favourite, and the farmer promoted his stable lad to a better place, and set Ben to take care of the horses. This suited Ben admirably, and old Dobbin, and Jack, and the rest of the stud, soon looked so glossy and sleek, that their master hardly knew them again.

Ben thought he ought to be very happy now, and he almost made up his mind to remain at the Lee farm "for good," and to forget the delights of a wandering, idle life, which he had not led long enough to find hard and full of privation at times. Moreover, he felt a little grateful for the kindness of his master and mistress, and meant to behave well, and to serve them faithfully.

These were good resolutions, but, alas! as the fruit ripened in the garden behind the stables, the temptation was too great for poor Ben. Many a night did he desert his lair in the fragrant hay, and visit that garden, gathering his hat and pockets full of strawberries, gooseberries, or cherries. Mrs. Heath, poor woman, was "terrible put about," to use her own phrase, at these nightly raids upon her fruit, but Ben managed so cleverly that he never was suspected. Indeed, he was supposed to sleep at a village a mile or so distant, as he had not been able to get a bed nearer to the farm, and there was no room for him in the house.

Every evening when work was over, he took care to be seen setting off down the lane, and across a couple of fields, by a path which led through a strip of plantation, and then across other fields, to the village in question. But he never went beyond the plantation, except when he needed a new store of tobacco; on other evenings he remained in the little wood, watching the birds and beasts which lived there—an old and favourite amusement of his. Then, as soon as he thought he could do so unperceived, he crept back, and climbed up into the hayloft. As it was now his duty to get down the hay for the horses out of this loft, no one else ever came there, so the piles of gooseberry skins in one corner did not betray him.

Mrs. Heath tied up the big dog, Tearem, in the garden. But Ben had made friends with Tearem; and whoever he might tear, he never tore Ben, but fawned on him lovingly. No doubt he would have been found out in time, and probably been thrashed as well as dismissed by the indignant farmer, but, as it happened, he left to please himself, though not exactly pleased to do so at the moment.

It was all because of that tiresome little silken string, which kept tugging at his heart occasionally. He refused to think of it for a time, and laughed and joked with the other lads about the place, but it really troubled him for all that, and at last it gave one such terrible pull, that he gave up and made up his mind that he must go home, and "see what end of little Fan."

It was partly his mistress's doing, though nothing could be further from her intention. One day in August she asked her husband to leave Ben with her, to help in the churning, which she said was too much for her and her pretty daughter Alice; and Molly, their one servant, was gone home for a holiday.

So Ben remained with his mistress, and learned how to churn, and did churn manfully; and the butter having "come," he helped to dash in a little water, to make it "go together," as Mrs. Heath called it. And then the butter was taken out of the churn, and Ben stood by, highly interested in the whole process, and saw it thumped, and washed, and thumped again, to free it from drops of buttermilk; after which it was salted, and made into golden bars, each weighing one pound, and packed into a basket with green leaves and damp snowy cloths, ready to be carried off to market the next day. And while this was being done, the following conversation took place.

"Well, Ben Fairfax, you 'are' a handy lad! I must say that for you. You must have been well used to help your mother. You're not like most lads—all thumbs and no fingers."

"Never helped my mother in my life, ma'am. It's native genius—that's where 'tis, as my old master said when I took to riding so easy."

"Your old master!" said Mrs. Heath, surprised, for she fancied she had been told that he had never been in service before.

Ben perceived his slip, and said carelessly—

"I called him so, but it was only an odd job I ever got from him."

"You have a mother, haven't you, Ben?"

"A sort o' mother; and not a nice sort neither," said Ben, with a shake of his curly pate. "Do you see this dint in my nob, ma'am? That's her handiwork. She did that with a saucepan lid when I was only a small chap."

"Laws, child! She might ha' killed you, strikin' you on the head like that."

"And if the coroner wouldn't object, ma'am, 'she' wouldn't; nor my father either."

"What is your father's business, Ben?"

"He's a shoemaker, ma'am. He made these shoes on my feet." Ben often said this, but he did not add, as he might have done, that the shoes had not been intended for him, but that he had helped himself to them as he left the house the morning he ran away. "And he trains dogs and ferrets, and sells rats, and—"

"Rats!" screamed Mrs. Heath. "And for mussy's sake, Ben Fairfax, who wants to buy such vermin as rats?"

"Gents buys 'em for dogs to kill, ma'am. They get up matches, with bets, so much on each dog, to see which will kill most rats in the time named. And then they buy the rats, so much a dozen."

Ben had a very strong suspicion that his father had other means of "turning an honest penny," to use Mr. Fairfax's favourite expression, but he said nothing about that. Mrs. Heath, you see, being a woman of small experience, might not have thought the penny an honest one.

"And do you mean to say that any one can make a livelihood out of the like of that?" inquired Mrs. Heath.

"Father does—along with shoemaking in a small way. A very good livelihood too. They always seem to get along pretty comfortable, as far as eating and drinking goes."

"But, Ben," said Alice Heath, looking up from her tub of butter, "if you had a comfortable home and plenty of food, why did you come tramping through the country for work? And so shabby as you were, too, till mother gave you Ned's old clothes."

"I didn't live at home; couldn't stand the way they licked me."

"I dare say you deserved it," said Alice, laughing.

"Maybe I did, sometimes, but I didn't like it any the better for that. So I—ran away at last."

"And are there no more in family, Ben? Have you any brothers and sisters?"

"One brother, a baby, and the ugliest thing you ever saw in your life, ma'am; and such a one to squall. And one sister, little Fan."

"How old is she?"

"Well, she must be eight or nine, but she's very small for that. She can't be so old, surely; and yet—yes, she must be. Poor little Fan!"

"Is she pretty, Ben?" asked Alice.

"Well—no, miss; I don't think you'd say so. But—she's better nor that. She's the lovingest, tenderest-hearted little thing—"

He broke off abruptly and remained silent for some time. At last he said half angrily—

"Why did you make me talk of Fan? I didn't want to talk of her."

"Well, but what harm, lad?"

"If harm comes of it, 'twasn't of my seeking, any how. There's the master now with Dobbin and Jack, mud up to their blessed noses! Where on earth have they been? I'd better go and see after them, ma'am, if you don't want me any more."

And he ran out of the cool, dark dairy in a great hurry. But the thought of little Fan, his only sister, the only being in the world who loved him, or whom he loved, was not thus to be got rid of. Once fairly roused, it refused to be left behind in the dark dairy. By hard work, rough play, smoking many pipes, and sleeping sound after his midnight diversions in the fruit garden, Ben had almost succeeded in stifling the thought of Fan until now. Not quite, however; and now this talk about her had given his memory a jog, and oh, how that string began to pull at his heart!

Little Fan, gentle, timid, good little Fan, left to bear all unaided the blows and bad words of an unkind mother, and the neglect of a worthless father; to carry the ugly baby until she was ready to drop, and then punished when it squalled, which it did frequently; left to have her food seasoned with unkind words and scoffs at her frightened face and want of strength; left, in fact, to battle with her wretched life without the occasional visits of her only friend and protector, "our Ben," as she fondly called him—visits which had long been the one happiness of her life. He could not get Fan out of his head.

He resisted long. For nearly a week, he fought against his longing, and he called innocent Mrs. Heath every bad name he could think of, and I can assure you they were not few; he raged at himself for his folly; he thought of the oath he had taken never to go back; he asked himself what good he expected to do to Fan or anyone else. But it was all in vain. Fan's pale little face, looking even sadder and more forlorn than when he last saw it, was ever before him. He seemed to see it change, and become full of the brightness of joy, and he heard her voice saying,—

"Why, it's our Ben," as he had often heard it in reality.

Finally, one night he jumped up from his comfortable bed in the hay with a shout. "I must go, I suppose. Bother the woman! Why must she go and talk of Fan? It's not a bit of real good to her; and yet I must go and see after her, and let her know I'm all right. She do love me so, poor little Fan! And she must think 'twas hard of me to go away and never look after her, when I know I'm the only comfort she has in the world."

He pulled on his clothes, not very handsome ones, unless by comparison with those he had been wearing when he first came to the farm. Having dressed himself and made up all his possessions in a bundle, he climbed down by the pear tree, and looked about to ascertain what hour of the night, or rather morning, it was. His mind being now made up to go home, he determined to be off without giving notice to any one, partly for the fun of the thing, but partly also for the following reasons. He had been paid his week's wages the day before, seven shillings; and of these he owed two to another lad about the place, whom he had been teaching to play at pitch and toss for halfpence. And he also owed a few shillings to the woman of the little shop in the village, for tobacco. Moreover, Tom Digges, his comrade, not having been present when the master paid the wages, Ben had offered to take his for him, and to give them to him the next day, which he doubtless would have done, as he had several times done it already, but for this sudden determination to go away. Tom's wages were higher than his, because Tom went home for his meals, and Ben lived at the farm.

Seven shillings was very little to begin the world on, and so Mr. Ben marched off with poor Tom's ten shillings also, without, I am sorry to say, the least compunction. Also, as he crept along the line of farm buildings, which ended in a large drying green, he saw something dangling on a clothes' line; and on drawing nearer, he perceived that it was a blue cotton frock, belonging to Mrs. Heath's little grandchild, Etty Spence, who was staying at the farm to recover from whooping cough. The frock had either been overlooked the night before, or (which was more likely) was believed to be quite safe in so honest a neighbourhood. It was just the right size for Fan; for though she was much older than Etty, she was so very small for her age; and it was so pretty and neatly made. Fan had never had such a frock in her life, and how kind she would think him for bringing her one; and oh, how Mrs. Heath would squall and search about for it when she missed it. So, with a chuckle, Ben twitched the frock down from the line, and it was quickly stowed away in his bundle, which contained some shirts, socks, etc., all presents from kind, unsuspicious Mrs. Heath.

Being now fairly off, Ben's spirits rose with every step he took, and he ran lightly down the lane and past the gate where he first met farmer Heath, without giving himself time to think; and having now reached the high road, quite out of hearing even if any one at the farm was awake, he began to whistle a tune—very sweetly, too, for he had a quick ear for music.

Now Ben Fairfax was a clever lad, as I daresay you have discovered by this time; and yet, setting aside all ideas of right and wrong, what a stupid thing he was doing! Here, for the first time in his life, he had an opportunity of gaining really good and respectable friends (for I cannot say that his first patrons had been either the one or the other), and, by his bright ways and quick intelligence, he had made them all like him. Had he gone to farmer Heath and told him that he must go home and see after his little sister, the farmer might have grumbled a little (farmers generally do grumble), but he would certainly have let him go, and promised to take him back when he returned.

But instead of this he went off, leaving the proofs of his evil doings to be seen by all at the farm, and carrying off things to which he had no right, so that, instead of friendly feelings, every one would be filled with anger and disgust. But, clever as he was, Ben never thought of this; never reflected that good friends are not always to be picked up; nor remembered that he might chance to meet some of these people again, when their good word might be of consequence, and their bad word fatal to him.

In fact, the idea of meeting any of them again never entered his head; here were they in Derbyshire, while he was going to London, on his way to his old home, and he was too young to know how small the world is after all, and how certain we are to meet again with people we have known. So he departed gaily—it would undoubtedly sound better if I could describe him as depressed by a sense of wrong doing, but truth compels me to state that he felt very jolly, something like a young horse which has slipped its head out of the halter and gone off for a frisk. Life at the Lee farm was certainly dull and monotonous—the old employment was far pleasanter, and perhaps Mr. — would have forgiven him by this time, and would take him back. Now that the plunge was made, Ben wondered how he had borne the quiet life so long.

"What would Sam Hadley" (the other party in the fatal race), "say, if he knew that I'd gone in for a respectable life without a bit of fun from week's end to week's end? He 'd never believe it, that's one thing."

And Ben laughed aloud at the notion of Sam's face if asked to believe this tale; thereby startling a most respectable elderly blackbird who was half asleep in the hedge by the road's side, so that he fled with a long wild cry, and startled Ben in his turn.

It seems, does it not, as if the silken string had pulled Ben out of safety and into danger this time. Yet, was it really so? Was Ben really safe at the Lee farm, deceiving his kind employers, stealing their fruit, and teaching their ploughboy to play pitch and toss all Sunday? The answer must depend upon our idea as to what Ben wanted to be saved from.

Before even the early hour at which Mrs. Heath's cheery call roused her household to their daily tasks, Ben Fairfax was several miles on his way to London. He had a long tramp before him, for he did not wish to diminish his small store by paying railway fares, preferring to keep it to begin the world upon.

Mrs. Heath called her family at her usual time—half-past five, and at half-past six they were all seated at breakfast in the clean and cosy kitchen. All, that is, except "London Ben;" where was he? He had not come, as he generally did, to tie up the wicked old cow for Alice to milk her, nor had he run in to aid red-armed Molly to draw water for the day's washing, nor had he carried off little Etty to see Dobbin and Jack munch their oats. All these things Ben was wont to do, for he was thoroughly good-natured and pleasant in his ways. But to-day he had done none of them.

And after breakfast a search was set on foot, and in process of time all Ben's delinquencies came to light. It was first discovered that he had been in the habit of sleeping in the hayloft, and the strong smell of tobacco betrayed the fact that he had also been in the habit of smoking there. Secondly, the gooseberry skins and strawberry stalks flung into a corner accounted for the nightly robbery of the garden.

Thirdly, poor Tom's lamentations made every one aware that Ben had gone off with his week's wages, and also with "Two shillin' wich he owed I, he did!" But when Tom, in his indignation, made known how the said two shillings had been lost and won, farmer Heath registered a solemn vow to "trounce Ben Fairfax well" if he ever had the opportunity, for introducing a taste for gambling among his farm boys.

Finally, the blue calico frock was missed, and the impression on Mrs. Heath's mind was that Ben had taken it. But, to do her justice, she grieved more over the ingratitude and dishonesty of the lad she had liked so much, than over the loss of the blue frock, or even over the fruit.

"He'll come to a bad end, will Ben Fairfax," she said, to her pretty daughter Alice. "He's none of your dull fellows, to be content wi' such small pickins' as he's made here. He's too clever by half, poor boy! And you mark my words, Alice Heath, he'll come to the gallows yet, or get sent to Botany Bay at the very least."

By this speech you may judge how far behind the times Mrs. Heath was; for it is many a long day since thieves were sent to Botany Bay, and as to hanging, we all know that it is really very difficult to get hanged nowadays, even for murder. And poor Ben with all his faults, was not likely to murder any one, for he was not a cruel boy. He was kind to those who were weaker than himself, and animals were safe with him, even from teasing. Tearem quite missed him, and stupid old Dobbin kicked at the lad who succeeded him in his stable duties, while as for the wicked brindled cow, she became (Mrs. Heath declared) "that rampagious that no one but a fairy could milk her at all," so she had to be sold at the next fair.

HOW BEN CARRIED OFF HIS SISTER.

BEN FAIRFAX did not hurry himself on his journey. The weather was fine, the nights warm, and the country beautiful; and to this beauty poor reckless Ben was by no means insensible. He was a keenly observant lad, too, and would stand absorbed for half an hour, watching a flock of rooks following the plough, and swooping down into the freshly turned furrow, cawing with such an intelligent sound that it was easy to fancy that they were speaking.

To many people that long march would have been extremely dull, and their only thought to get over it as quickly as possible; it was the old story of "Eyes and no eyes," in fact. Nothing escaped Ben's bright, observant eyes, no sound eluded his quick ear, and nothing he saw or heard was forgotten. He knew all about the rooks, for instance—knew that they never fail to post sentinels who watch while the flock feeds, knew that they hold meetings occasionally, apparently to talk over their affairs. He had even witnessed a trial by jury among them, followed by instant execution of the well-watched and terrified criminal, who was fallen upon and pecked to pieces in half a minute, without the least mercy, and with a horrible noise.

Ben had a great respect for the rooks, but they were not the only birds he knew something of. He could tell at a glance what kind of bird had built a new-found nest—how many eggs the little hen would probably lay, and how long she would sit there, patiently warming her children into life, and looking at him when he peeped at her, with bright, half-defiant, half-frightened eyes. Many a young thrush or blackbird had he put back into the nest when the ugly awkward creature had tumbled out, to the great distress of its affectionate parents.

Nor was he without four-footed friends. In that strip of plantation of which I have spoken, he had made acquaintance with divers funny, fluffy little rabbits, and had spent many a pleasant evening hour watching them washing their faces, and whisking their fat persons round in that sudden and slightly unaccountable fashion to which rabbits are addicted. Hares, too—he had watched them at their weird, graceful play—half a dozen together, scampering, turning, sitting bolt upright in the most gravely quizzical fashion, or jumping over each other, like boys playing leap-frog, until, in an unlucky moment, something betrayed his presence—a misfortune which the least movement occasioned—when back went all the long, soft ears, and away sped the hares in every direction, almost too swiftly for his eyes to trace their flight.

It was in that plantation, too, that he met with an adventure which pleased him very much—more than any one not gifted with a love of nature can well imagine. One evening he had been standing very quietly and silently for a considerable time just behind a gap in the hedge which bounded the plantation. He was listening to the evening song of the thrush, and watching a few rabbits frisking about, when the rabbits suddenly fled to their holes with great precipitation; nor did they sit down just inside the mouth of their dwellings, and look-out cunningly as was their usual practice, but disappeared utterly.

Ben stood still, wondering what the little things had seen, heard, or suspected, when behold! In the gap, walking softly and looking very tired, appeared no less a person than Mr. Reynard, the fox himself. I do not know what this elderly gentleman had been about. It was not the hunting season, but perhaps Tearem and a few friends had been having a little hunt for their own diversion, or perhaps food was hard to get, or perhaps he had been to visit a friend at a distance. But at all events, there he was, footsore, spent, and weary, and thinking only of getting home as fast as he could; though I don't mean to say that he could not have delayed a moment to pick up a fat rabbit, though his drooping brush showed that he was very tired.

Ben held his breath to have a good look; never had he met a fox face to face before. The weary creature raised his head and saw him. Too much startled to run, he simply stood and stared as hard as Ben stared at him. This lasted while you might have counted ten; then Reynard, without removing his gaze, quietly, silently, hardly stirring the daisies on which he set down his feet, glided through the gap, and—was gone; and Ben never got a sight of him again.

To one capable of deriving pleasure from such things as these, it was delightful to linger on this journey, during which he could indulge his taste to the uttermost. Yet still Ben kept going on; sometimes, indeed, feeling the greatest reluctance to face his old acquaintances again, but always, willing or unwilling, going to "see after little Fan."

So he reached London at last, quite sorry that his journey was so nearly over. From London he went by rail to F—, his native village.

Leaving the railway station, which was a little way out of the village, Ben walked briskly along the well-known road, which soon was merged in the small and mean-looking street of the village. Just outside the village, he saw some one coming towards him, and recognized his comrade, Sam Hadley, the companion with whom he had ridden that unlucky race.

"Well," thought Ben, "I fancied the railway folk looked at me queerly, but Sam can't look down upon me for getting dismissed, for he's not a bit better himself—not that he looks as if he 'd been dismissed, somehow. Hulloh, Sam!" he continued aloud, "here you are; how goes the world with you, Sam? Has Mr. — taken you on again? Somehow you look as if he had."

"Yes, he has," Sam replied, curtly. He did not seem delighted to see his old friend by any means. "And where have you been, Ben?"

"Oh, I've been taking a walking tour for the good of my health," said Ben, carelessly. "Well, I wonder at Mr. —. When he wouldn't take me back, I wonder he took you; for, no offence to you, Sam, I'm a better groom than you."

"But you see, I belong to respectable people," said Sam, primly.

"You be civil, young fellow, or maybe you'll find that I have not forgotten how to give you a licking. I wonder would the master take me back?"

"Well, I don't know, Ben. You see, your horse was killed, and mine was none the worse after a day or two; and the other fellows told him 'twas you led me into it. And now there's this about your father."

Sam spoke in a much milder voice since that remark about the "licking," and seemed to choose his words carefully.

"What about my father?" asked Ben.

"Why, bless me, Ben! Han't you heard on it? Your father's in trouble, Ben. They've suspected this long time that he was mixed up with the poachers on Lord —'s place, but some weeks ago he was ketched. 'Twas in the middle of the night, he and Simon Pettitt and Long Joe, the man that we knew up at the stables, was ketched with a kivered cart full of game, going up to London; and they're all in jail, committed for trial. And what's more, Ben," continued Sam, looking round nervously, and drawing a little nearer to his companion, "I believe the police are on the look-out for you, thinking as you may know summat of it."

"Well, they're wrong then. I never knew anything about such doings."

This was true enough; for though Ben had long felt convinced that his father had some means of making money of which he said nothing, care had been taken that he should know nothing positively. Fairfax had often hinted that some day he would admit his son to a valuable secret, but that he was too idle, and too fond of talking as yet, to be depended on.

"Tell that to the marines, Ben," remarked Sam, jocosely. "A sharp chap like you not know what his own father was up to!"

"Well, I didn't, I tell you. But if they nabbed him in the act, with the cart and all, what do they want of me?"

"Why, you see, your father swears he knew nothing of what was in the cart, and was only taking a walk in consequence of having had words with his missus—and as he surely had words, and more than words, with her that night, poor woman—and Simon and Joe won't split on him; you see, they want more evidence badly."

"They'll get none from me, anyhow. Let them ask Mrs. Fairfax; if there's any mischief going, she's sure to have a hand in it."

"Why, Ben! Surely you know—Laws, Ben, here's a policeman. You'd best be getting on."

And Sam hurried away, not anxious to be seen in conversation with poor Ben, under the circumstances.

Ben jumped over the hedge at the side of the road, ran along the field he had thus entered, and made his way to the cottage where his father lived by various short cuts best known to himself. As he ran, he thought to himself that it would never do for him to be taken by the police, for many reasons. First, how account for his long absence, without running the risk of being brought to book for his dishonesty at the Lee farm? And secondly, if Mrs. Fairfax also was in jail (as he fancied Sam had been about to tell him), what would become of poor little Fan?

At last he stood in the street, close to his father's house. The shutters were closed, but the door was a little open; and, in spite of many fears that a policeman might lurk inside, Ben ran quickly past the door of the next house, not caring to ask news even of good-natured Mrs. Simmonds, and entered the kitchen of his old home.

There was no one there, no fire on the hearth, and the room was partially darkened. Ben stood, and looked round, and listened. The furniture was all in its place, but it was dusty and unused; the ugly baby's cradle lay upset in a corner. There was an inner room which looked to the back of the house; the door was shut, but Ben presently fancied that he heard some one crying softly in the room. He opened the door and looked in. There were the beds, just as usual, but at first he thought there was no one there. Then he heard that feeble moan again, and surely the voice was little Fan's.

"Fan!" he cried, softly. "Little Fan—are you here?"

Something in one of the beds moved, and then a white, white face appeared, with great, big, scared-looking eyes, and short hair sticking out straight from the poor head, which "wobbled from side to side," as Ben afterwards described it, as if it were much too heavy for the feeble neck. But when the eyes lighted upon him, such a flash of gladness brightened them; such a relieved, comforted smile parted the pale lips, that the face was transformed even before the ghost of Fan's voice murmured, hoarsely—

"Why, it's our Ben! And so I'm safe."

Ben went over to her. Her poor, thin arms—Fan had never been what you could call fat, but now a skeleton was what she most resembled—were soon clasped round his neck, and her cold lips pressed to his. And he felt, somehow, so big and strong and rough, in contrast with her feebleness, that he was almost ashamed of himself.

"You've been ill, Fan darling, and I not here to nurse you."

"Oh, so ill, Ben dear! We've all been ill, and—oh, Ben, go away—I oughtn't for to touch you. The doctor says it's 'fectious, and I've had it very bad. Oh, go away, Ben! And when I'm well (if I ever get well), come and see me in the workhouse."

"In the workhouse! You shan't go to the workhouse, Fan. I'm sure you don't want to go?"

"Want to go! Why, Ben, I'm near dead with fretting! But they said I must go, for that I'd starve here by myself. But when I thought they'd take me to the house, and keep me locked up, so as I'd never see you again, Ben, I thought I'd die on the spot. And I didn't want to die before I'd said good-bye to you, Ben. But now I've seen you—and you'll know where I am—and oh, Ben! Do go away, dear!"

"Not a step, Fan. Fever or no fever, I don't leave you. But where's all the others, Fan?"

"Why, don't you know? Poor father's took away to prison, and mother—Oh, Ben, I thought you'd have heard that! She's dead. She died of this fever, and the baby, too—poor little Tommy!"

Ben was shocked—too much shocked even to think that the baby, at least, was a good riddance.

"Dead!" he repeated. "Why, Fan, how could I know it? It's an awful thing—and I've been away in the country, miles and miles away. I only came back this very day, to see after you."

"To see after me," the child said with a happy smile. "You're always so good to me, Ben. And maybe, if you really won't go away, maybe they won't take me to the poorhouse. You'll see after me till I die or get better. The doctor says I'm over the fever, but that very like I may die of the weakness. But now that you are here, I don't think I shall."

"To be sure you won't, child. I'll take care of you, and no one shall take you from me. Who was going to take you, dear?"

"The police. You know they took father, and Simon Pettitt, and Joe Harris, and they came next day for mother, but she was ill, and then it turned into the fever (for at first, Ben, it was only a thump father gave her), and they said, after she died, that they'd take me to the poorhouse as soon as I could be moved."

"And who has taken care of you, Fan?"

"Mrs. Simmonds. She's so kind to me! She comes in constant, though Jack Simmonds had the fever, and little Billy's in it still. Every one's been having it. Mrs. Simmonds never forgets me. She's like the righteous, Ben, 'you' know—'I was sick, and ye visited me.'"

Suddenly the eager voice broke out with a cry—

"Oh, Ben Oh, Ben!"

"What's the matter, Fan dear?"

"It's just the weakness. Oh, dear! I think, Ben—I'm going—this time. I ain't afraid. 'He' died—and I've seen you again—Ben, dear."

And Fan closed her eyes and fainted dead away. Whereon Ben, big, stout-hearted fellow as he was, lost his presence of mind so completely that he raised a roar of mingled grief and fright, which soon brought a very untidy but kind-looking young woman running in through the empty kitchen with all speed.

"'Sakes, Fan!" exclaimed the new comer, "How could you, that's weaker than any new born baby, rise such a—Laws! It's Ben come back. And she's fainted with joy! Don't be scared, Ben; she's been like this more than once, and I'll bring her to in a moment. It was just too much for her, seeing you. Your name is never off her tongue."

Mrs. Simmonds soon made good her words, and Fan opened her eyes again, and smiled feebly when she saw her brother.

"There, now she'll be all right again. And I've made a cup of tea and a bit of toast for her, and now I'll run back to my own place for it, and feed her. And don't you let her talk much, Ben, for indeed she's too weak for it, and I can answer all your questions while she has her tea."

And away she ran.

"I shouldn't have let you talk, you see," said Ben, "but I'm in such a maze, Fan, that I don't know what I'm doing, nor where I am. Here's Mrs. Simmonds again. Well now, Mrs. Simmonds, you're something like a neighbour; and if ever I get the chance, I'll remember this cup of tea to you."

"'He' will, anyhow," Fan murmured, half to herself. "Even if 'twas only a cup of cold water, instead of lovely tea. 'He' don't forget anything."

"Ain't she a queer child?" said Mrs. Simmonds confidentially, to Ben.

"No, I ain't a queer child," said Fan, half fretfully. "There's nothing queer about it. And I'm glad He never forgets," they heard her mutter sleepily, "for most likely I shall never be able to do anything for her."

"Who is it she's talking of?" said the woman in a whisper.

"Blest if I know," Ben answered carelessly. This was not strictly true, for it was not the first time he had heard Fan talk thus.

"The little creature! She's dropping off into a doze. So much the better, poor lamb! I'll draw the blanket over her—there. She's stronger to-day than I've seen her yet, but I'm afraid it will go hard with her when they take her away."

"But they need not take her now, Mrs. Simmonds. Look here, ma'am; you've been so kind to her that I'm sure you'd take a little trouble for her sake. I'll tell you fair and true how the matter stands. I could care for Fan right well, for I'm as good a shoemaker as father, and a good hand about horses too; and I'd work hard and keep her better and make her happier than she ever was in her life, if I could only see my way out of this hobble. They would never take her to the house if they knew all this, but there, you see, I can't stay and tell them so. It seems they think I could give evidence against father—and besides, I've reasons of my own for not wanting to have words with them."

"And what do you think I could do, Ben?"

"If you'd tell them that you'll keep Fan, and just take her home with you until I can venture back here. I'll work hard, ma'am, and pay you for her keep."

"Are you sure she's sound asleep, Ben? Ah yes, she is, poor little thing! But watch that she does not wake up and hear us, for she only dozes for a minute or so, mostly. And I've kept the truth from hers because she's such a soft, tender, little thing, that I'm afraid it would really harm her to know. I don't know that it is to the workhouse they'll take her, Ben, though I've told her so. You see, they know that she can prove that those two men have been in the habit of coming here and bringing game with them, and packing it here. They say she's seen it often, but if she did, not a word did she ever say about it; unless, mayhap, she told you," she added inquiringly.

"She never did. I didn't know anything, whatever I may have suspected. Fan's a strange child! Little as she owes to father or Mrs. Fairfax in the way of kindness, she 'd obey them as strict as strict. If they said 'Don't tell,' tell she never would."

"I'm afraid they'll never believe that you didn't know about it, Ben. And they are to come for Fan to-night."

"To-night! Well, what am I to do?" cried poor Ben, distractedly.

"I'm sure I don't know. They left her in my care, because the poor thing fainted when they tried to move her, but they said they'd bring a stretcher to-night when it is dark, and take her away. They want to keep her under their own eyes, until she's given evidence against her father. It is a hard-like thing, too; to make an innocent child like that help to hang her own father; ain't it, now?"

Ben was about to explain to Mrs. Simmonds that to the best of his belief, poaching is not a capital offence, but he had only time to say, "It won't be so bad—" when a scream from poor Fan made them turn to look at her.

There she was, sitting up in the bed, holding out her poor, thin arms to Ben, and crying wildly—

"Oh, take me away, Ben! Hide me! Don't let the police get me. Oh, I didn't think people could be so cruel! I didn't know 'twas wrong to catch birds and hares. And to think that they'd get me to tell about it, and then hang father for doing it. And I did see them, Ben. I couldn't say I didn't. And oh, poor father! What would become of him if they hanged him?"

In spite of the poor child's terror and agony, Ben laughed aloud at this question. It seemed to him very easy to imagine what would become of his father in that case.

"They won't hang him, Fan, never you fear. It's not a hanging matter."

"It is, though," said Mrs. Simmonds, emphatically. "My husband's mother's grandfather was hung for poaching. There now, that's as true as that you're standing there. Many a time I've heard her tell the story, as her father told it to her, and he could remember being taken to the jail to bid him good-bye."

This terrible piece of family history somewhat alarmed even Ben; and as to Fan, she looked quite wild, and cried out again—

"Oh, what will become of poor father if they hang him?"

"Why, child, if they hang him, he'll be dead; and that's all about it."

"And afterwards?" cried Fan, wringing her hands like one distracted. "Oh, Ben, where would he go? Poor father, you know he is not—Oh, Ben, you were always good to me. Help me to put on my clothes, and take me away and hide me; for if they make me tell about father, I don't think I could live any more. Dear, dear, good Bennie, do hide me from them."

"I declare, hang or no hang, Fan's about right," said Mrs. Simmonds. "If you two were safe out of the way, Ben, they would, maybe, never be able to prove anything against your father. And my advice to you is to wrap her up well and carry her off as soon as it gets a little darker, but don't wait too long, or the police may come before you're off. And I'm not to know a word of it, mind you! My man would be very angry with me. I'll be struck all of a heap when I miss Fan, and I know nothing of her since I gave her some tea, and saw her fall asleep after taking it. I'll go home and begin my mangling; it's little I'll hear of your doings with the old mangle screeching and groaning in my ears, even if you rise a howl like the one that brought me in."

"Right you are, Mrs. Simmonds. Only I don't know where to take her. To London, I suppose. No one could track us there."

"Only mind the railway people don't remark you."

"I won't get in here; I'll carry her to —" (another station, a little further from London). "But with the child to carry about, I really don't know where to go. It won't be easy to find a lodging."

"I can help you in that," Mrs. Simmonds replied. "I'll give you the address of an old woman who lived over in the part of the country I come from myself. And when I was a girl looking for a situation, I used to stay with her. She's honest, but she's very cross. And don't you say anything about the fever, or she'll be afraid to take you in."

"All right. You get me the address. I'll never forget your kindness, Mrs. Simmonds, you see if I do."

Mrs. Simmonds ran off to her own cottage, and soon returned with a somewhat dirty scrap of paper in her hand.

"Here it is, Ben; and if you take my advice, you'd call yourself by some other name for a time. Take care of the little one—and now I'm off, and know no more about you."

She vanished again, and was soon heard next door, turning her heavy old mangle with tremendous energy.

Poor Fan had scarcely heard all this talk, which was well for her peace of mind, as the duplicity would have shocked her greatly. Terror and weakness, however, had rendered her quite passive.

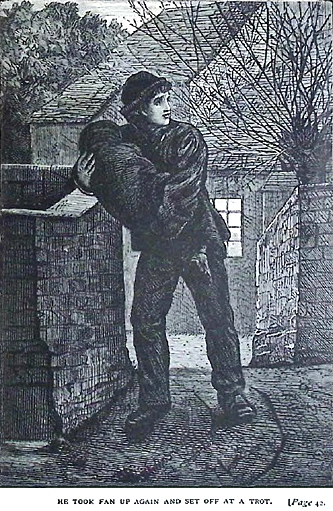

Ben dressed her as well as he could, and made up a bundle of clothes for her, as much as he thought he could carry. Then he waited nervously until it was tolerably dark, when he wrapped her closely in a big brown shawl which had belonged to the poor dead woman, lifted her in his arms, and carried her into the outer room. Here he set her down on a chair while he peeped out, and looked up and down the street. No policeman, nor, indeed, any other person, was to be seen, so he took Fan up again and set off at a trot.

The shock of the fresh air was too much for poor Fan, who at once fainted away, but Ben did not find this out until he was nearly a mile out of the village. Having seen her in that state before, he was not so much frightened, and soon managed to get some water and bathe her hands and face, having laid her down on the grass by the road's side.

He then took her up and went on again. His first object was to reach a small railway station, where he was not known. It was a fine night, and he was strong, and Fan very light, so in due time they reached the station, and took their places in a third-class carriage of the next train for London.

HE TOOK FAN UP AGAIN AND SET OFF AT A TROT.

Ben was very tired before he found the street and the house to which Mrs. Simmonds had directed him, but he did find them at last. The old woman had one single attic unoccupied, which Ben engaged for a week; and very glad was he to lay his burthen down on the bed. Fan did not seem the worse for her journey; and having been fed with some bread and milk, she fell fast asleep.

Then he went downstairs and had a little conversation with his landlady—a very cross-looking old lady she was, too. He informed her that his sister had been "like that" for many months—a kind of decline, the doctors called it; and he didn't think she 'd trouble him long. Poor Ben! It was a pity that he should try to make himself appear worse than he was, for really he was bad enough. But it was not true that Fan was a burden of which he longed to be rid. On the contrary, her death would have nearly broken his heart. Besides this tale concerning Fan, he, having a fine turn for fiction, gave her a flowing account of his reasons for coming to London, in which there was not one word of truth from beginning to end.

Ben was very anxious to find work by which he might provide for himself and Fan. His small store of money was running out faster than was pleasant, and something must be done to get more. He could not depend on what he might "pick up," now that Fan was dependent on him, even if he had not felt very sure that she would not altogether like his method of "picking up" things. He made up his mind to remain where he was until she was stronger, doing odd jobs (his landlady put him in the way of several), and then, if nothing better had turned up, he would set forth on another "walking tour," never doubting that in the country he would always find employment.

WANDERINGS.

BEN'S plans for remaining in London were all brought to nothing by half a dozen words from a policeman. And the best of the thing was, that the policeman knew nothing of Ben and was by no means thinking of him when he spoke. He was looking idly down into the area window of a house he was passing, just as Ben came by on his way home after a good day's work, unloading a waggon at a shop door. Something the man saw in the kitchen he was peeping into, made him raise his head and exclaim aloud, looking apparently at Ben, "I'm blessed if that ain't—"

What, Ben did not want to hear, for, feeling certain that the next words would be "Ben Fairfax, the poacher's son," he took to his heels and ran.

The policeman looked after him with a curious grin.

"That fellow thought I knew him!" said he.

Ben did not venture to go home for some hours, and he made up his mind that, if possible, Fan and he must get away soon. He was very late, of course, when he returned to his lodgings, and there a very unpleasant surprise awaited him. When his usual hour for coming home passed, old Mrs. Harris, with more good nature than her appearance promised, went upstairs to see the sick child; and having asked Fan if she wanted anything, and Fan having said "no thank you, ma'am," she remarked—

"You're not hungry, eh? Some is, and some ain't. I've know 'd them as was in a decline that you couldn't keep them in food. They 'd eat all day, and all night too, if they could get it. And then I've known others as was like you, child—didn't care if they never saw bit nor sup at all. It's queer the differences there is in decline."

"But I'm not in a decline, ma'am," said innocent Fan. "I had a fever that lots of people had where we lived, and mother and baby died of it. But I'm getting on nicely now, thank you, ma'am."

Whereupon the old woman flew into such a passion that she very nearly frightened Fan into a fit. She used very strong language, and threatened to "throw her out into the street that moment!"

Fan clasped her hands and said her prayers half aloud, in the extremity of her terror. But Mrs. Harris did not touch her, and presently went downstairs, grumbling and muttering. But she kept a bright look-out for unlucky Ben. And he, running in, hungry, tired, and frightened, was surprised and disgusted by a salute from a pail of dirty soap suds, thrown over him by his hitherto obliging landlady.

"Hulloh, missus what's this for?" cried he.

"You young rogue! Coming here telling me a pack of lies. Decline, indeed! 'I'll' decline you. Nice decline she has!"

The old woman hissed out her words in a kind of half whisper, half cry; she did not care to call the attention of her other lodgers to the dispute, lest they should take fright, and leave her house.

"If it wasn't that I pity that poor child upstairs, I'd have given you a tidy warming, young man," she went on. "I'd have got them to help me as would teach you to tell lies—" (Ben might have assured her that this was quite unnecessary, but the impudence was washed out of him for the moment)—"bringing the like of that into my house. But I won't hurt you, for she has no one else to look to—only out you go. This moment, now. Go upstairs and fetch the child and march out, or I'll raise the house on you—I will! And just wait till I catch Nancy Simmonds—sending you here."

Ben was tired, hungry and somewhat frightened, not by any means as good a match for his enemy as he would generally have been. He tried to deprecate her wrath, but she wouldn't be deprecated. He tried to bully her, but she had the best of him at that game. Lastly, he tried to coax her into letting him stay in the house until morning, but she would not hear of it.

"But, ma'am, I really don't know where to take poor Fan. So late at night, too!"

"Just take her to wherever you brought her from, and don't go spreading fever where people have enough to bear without it. But wherever you go, get out of my house this moment, or I declare I'll call a policeman and tell him the trick you've played me."

This threat decided the matter; Ben flew upstairs in haste. The old woman, whose bark was worse than her bite, cooled down a little when she found that she had routed the enemy; and she even listened for his step on the stairs, meaning to allow him to remain until morning. But she never heard him go, and when at last she went up to have a further parley with him, she found the room empty. In the hurry of departure Ben had forgotten to pay his rent.

Ben, flying upstairs with the soapy water dripping from his garments, rushed into the miserable attic where he had left his sister, and found the poor child in a terrible state, between terror of the old woman and fright at his long absence. She had contrived to dress herself, though still weak, and had her poor little hat ready in her hand as she lay trembling and quaking on the bed.

"Oh, is that you, Bennie, darling? Oh, Ben, what kept you? I've been so frightened, dear. The woman called me such dreadful wicked names, and said she 'd put me out of the house. I dressed myself for fear she would really do it. But you're all wet, Ben. I feel water on your jacket. Is it raining?"

"No, dear, no; but that old beast threw a lot of dirty water over me. How did she find out that it was fever you had, Fan?"

"Why, I told her. She thought I was in a decline."

"Well, you are a little donkey," Ben said, half laughing. "I ought to have warned you to hold your tongue. Never mind, though; we must be off out of this. But we must have gone soon at all events, for I met a policeman to-day that seemed to know me—that's what kept me so late. I would much rather have you in the country, too. See now, I'll wrap the big shawl round you, and carry you as safe as anything."

"And where are we going, Ben?"

"Blessed if I know," answered Ben. "But she won't even let us stay until morning! I say, Fan, is there any bread left? For I'm awful hungry."

Fan gave him a piece of bread, and he quickly devoured it, while she fumbled about in the dark, getting their few possessions together.

"There's some milk in the tin cup, Ben. I left some for you."

"Thank you, little one. And the cup's a handy one; I'll put it in the bundle."

"But it belongs to the old woman, Ben, dear," objected Fan.

"Oh, she gave it to me for a keepsake," Ben answered, with a laugh.

"Then she was not so very angry? I'm glad of that."

"She was angry enough. Now, are you ready? Are you well covered up? You carry the bundle, and I'll carry you: that's the way we'll divide the work between us."

Fan's soft little laugh at this joke, and her arms clinging round his neck, made the big, rough boy feel inclined to cry, he did not in the least know why.

"Now, hold your tongue and don't let her hear us, or perhaps she'll send another pail of water after us. I'll carry my shoes till we are out of the house."

So down he crept, silently, and they were soon in the street.

"Nicely sold Mrs. Harris will feel when she goes up to drive us out," chuckled Ben, as he pulled on his shoes, having set Fan down for that purpose.

"Look, Ben, I can walk quite well now."

"Well done, Fan. You're a long sight better than when I saw you first. Why, you couldn't keep your head from wobbling about that evening; and here you're walking like a grenadier."

But Fan would have made a poor grenadier, I am afraid; and very soon Ben took her up again. Tired and anxious, he soon began to feel very weary. Fan was considerably heavier than when he had carried her off from F—. Besides, he had no object in view, and was beginning to wonder what he had better do. In order to think this over more at his ease, he looked out for a deep doorway, and into this shelter they both crept, and made themselves as comfortable as they could. Fan was warm and snug, wrapped in the woolly shawl, but Ben's damp clothes made him very chilly, and in spite of the piece of bread, he was still hungry. Perhaps these unpleasant sensations recalled the warmth and plenty of good Mrs. Heath's house, for he sighed and said—

"If I could only go back to the Lee farm, what a good thing it would be."

"That's where you were working, and where you saw the birds and rabbits? Oh, Bennie dear, let's go there. I'm sure I could walk most of the way now; and it must be such a nice place."

"I couldn't go there, Fan; more's the pity."

"Why not? They were good to you, weren't they?"

"They were," said Ben, slowly. "But I made a mistake or two the night I came away. I can't go back, so say no more about it. I was a fool for my pains."

Ben's will was law to his little sister, so she asked no questions.

"But, Ben," she said after a time, "isn't there other places out in the country besides F— and the Lee farm? If we went quite a different way, the police would maybe never find us at all. I think it would be a real good thing if we went away into quite a strange, new place."

"I think so, too. But the question is, how to you get there; for as to your walking, my dear, you wouldn't do many miles in the day just yet. Once we were in the country, we might get on, because we needn't hurry. We could rest when we liked."

"Can't we go in the railway, Ben?"

"Well, yes; but, you see, it costs a lot of money. Let me think a bit, Fan."

Fan was silent, and amused herself by looking up into the tiny patch of blue-black sky over her head, and at the one bright little star which seemed to be winking at her.

Presently Ben said—

"I have it, Fan! I know how we'll manage. I was helping all day to unload a big waggon that came in with pears, and apples, and nuts, from the country, to a shop not very far away from this; and the man told me he meant to set off for home again to-night. And he came from the direction we had better take; he seemed a good-natured fellow, and I daresay he 'd give us a lift out into the country. Should you be afraid to be left alone while I look for him? He's brother to the man that owns the shop, so he's sure to be there to the last moment."

"No," said Fan, "I shan't be alone, you know. He'll mind me, for He's my Shepherd and I'm His lamb, you know. Miss Alice taught us all that. Why, Ben, He didn't let the poor cross old woman hurt to-day! I was 'so' frightened for a moment, but then I remembered Him, and I knew 'twas all right."

"Ah, well; no one will meddle with you if you keep far back—no one could see you, in fact. You're a queer child, Fan! See now; I'll tuck the shawl round you—so; and lay your head on the bundle, like that. There; get a nap if you can. I shan't be very long away."

Fan lay quite quiet. Once a policeman passed by, but he did not see her; and she laughed gleefully when he was out of hearing. Many a child in a pretty, comfortable nursery, tucked up snugly in a warm bed, did not feel as peaceful and secure that night as did little Fan, lying on a doorstep, all alone. Yet not alone! Because Fan knew and loved One, about whom many children never think, because they cannot see Him.

But Fan, poor ignorant child that she was in many ways, having never been allowed to attend school regularly, had been happy in one thing: her parents were rather glad to have her out of their way on Sunday mornings, and she had, therefore, gone to Sunday school regularly enough. Her teacher, the "Miss Alice" of whom she sometimes spoke, had a wonderful gift for telling great truths in simple language: her Bible stories were always listened to with earnest attention; and the verses she taught the children in connection with the stories were not easily forgotten. Thus Fan knew many verses perfectly, though she could scarcely read, and could not write at all. Fortunately for her, her small size caused her to be reckoned younger than she really was, and so she had been left in her dear Miss Alice's class longer than she would otherwise have been.

Many a box on the ear had the child got at home, for talking of things learned from Miss Alice, or for singing a hymn to quiet the baby: and Mrs. Fairfax often declared that Fan was "only half-witted." A few weeks before her illness, Miss Alice had given her a present which she valued highly—a small New Testament. This precious book, which she could hardly read, unless when, as she said herself, "she happened on one of Miss Alice's verses," was in the pocket of her frock, safe and tidy, wrapped up in a piece of paper. It was the only thing in the world that Fan called her own.

Ben, returning after some time, found his small sister fast asleep, and, stooping over her, touched her gently on the cheek and said—

"Wake up, Fan; I've found the man, and he will give us a lift. A great waggon with two horses! You'll travel like a queen—and he'll take us fifty miles into the country if we like to go so far."

"Fifty miles!" cried Fan, with sleepy admiration. "Why, shan't we be at the end of the land before that?"

"Yes; and then we'll swim a bit," said Ben, laughing. "Rouse up, child! You're just like a young bird in the nest, always nodding its head, and going off asleep the moment it leaves off being fed. Now, mind, Fan, not a word of the fever to this man; for he 'd turn us out as fast as ever Mrs. Harris did."

"Would he, Ben? But why?"

"Why? For fear he 'd take it, of course. So, mind now—not a word. And don't forget this either, Fan. We'll call ourselves some other name—Robson will do; it's better not to say Fairfax, because of father."

Fan was silent, considering within herself whether this double deception were right or not, but surely Ben must know better than she could. She meant to ask him, but before she had quite shaped her question to her liking, they had met the great waggon, and Ben was putting her in. There was a glorious heap of clean straw in the waggon, and it was so comfortable under the awning, and in spite of the jolting, Fan was soon fast asleep.

Before she woke again, the sun had risen and they were out of London, to her great delight. London was so black, so noisy, and so ugly! The big good-natured driver laughed kindly to see her so happy, and lifted the awning in front that she might look about at her ease.

"Oh, Ben dear! It is so 'lovely' green, and pretty, and sweet. And the bigness of it, after that little room, you know. And oh! I see a flower, a yellow flower, over there. Don't you see it, Ben—and 'would' you get it for me? Since I had—since I was sick, I have not seen a flower. It won't be stealing, will it? For you see it is inside the hedge."

At this Ben and John Ellicott, the driver, laughed until their eyes were full of tears. Ellicott stopped the waggon, and gathered the flower (a big dandelion). He brought it to Fan, as she sat peeping out of the waggon, and brought her also a blue flower, and a straggling spray of late flowering woodbine.

"That's a dandelion, that is," said he, evidently fancying that she had never seen one before. "Main good for a pain in the side, my old mother du say—they're plenty down tu Devonshire, though yew seem to prize her so. And that's the 'devil in a bush,' child, but though her has a ugly name, her 's a pretty flower, and in colour somewhat like your own eyes. And smell to this, little 'un; there's sweetness tu ye."

"Oh, thank you, sir! It does seem so long since I saw flowers. Miss Alice used to give me a rose sometimes, but—"

Suddenly a bird—a linnet, I think it was—began to sing clear and sweet in the hedge close by. Fan turned quite pale—listened in a kind of dumb ecstasy, and when the song ceased, she burst into tears. And she was still so weak, poor child, that having begun to cry, she could by no means leave off, and Ben had to lay her down again in her cozy bed, and let her cry herself to sleep.

The next time she awoke, the waggon was standing still, while the horses ate a feed of oats out of their nosebags; and Ben was at her side with a plate of bread and butter, and a huge mug of milk—such milk as Fan had never tasted before, so rich and yellow was it.

"Here's the stuff for you, Fan! Here's what would soon put a little flesh on your poor little bones, and set you growing. Milk, Fan—here, drink some."

"Milk! And such milk! Well, I never saw milk like that, Ben. Don't you think there's eggs in it?"

"You never got any but skim milk, you see, but I told the people here that you were poorly, and they gave me this fresh from the cow. Taste it now—you won't be able to leave off once you begin, it's so good."

"Have you had plenty, Ben?"

"Oh, I've had my breakfast—bacon and eggs."

Thus assured that she might safely drink the milk, Fan tasted it, stared into the mug, and tasted again. It was very nice, but to the last, she kept a look-out for egg-shells!

While she was eating her breakfast, her little tongue wagged freely. The boys about F— would have told you that Ben Fairfax was "a roughish customer," but he could never have been rough to Fan, for though a timid child, she had no dread of him, but prattled away happily.

"And while I was going asleep, Ben, that time you left me, I kept wondering and wondering why the stars wink and tremble so. But I think I see why, now. It's blowing up there, very like, and there's no glasses over the stars, as there is over the gas lamps. One gas lamp we passed had a broken glass, and it was winking and shaking very much like the stars. It's a wonderful thing the stars don't get blown out! They would, I suppose, only God watches them. He knows them all and calls them by their names, and knows where they ought to be."

Ben laughed incredulously.

"That's a likely notion, Fan. Why, there's hundreds and hundreds of stars, and some of them no bigger than a pin's head; and as to names, and counting them over, no one could do that, child."

This was Ben's objection, you see, to a revealed truth; and I don't know that it was more silly than a good many other objections that I have heard.

"He can do it, for the Bible says so. 'He knoweth the number of the stars, and calleth them all by their names.' That's a verse in the Bible, Ben. Miss Alice taught us that. Oh, Ben, that little bird—Miss Alice has a little pet bird, and one day it sang, when I was at the rectory with a message—and it sang just like that; and I wonder, shall I ever see Miss Alice again? Wasn't it good of God to make birds and flowers for us?"

"We'll see prettier flowers than those by-and-by," said Ben, pointing to the blue scabious and the dandelion; the woodbine had fallen to pieces, unfortunately.

"But these are pretty too. I'm sure I could walk now, Ben. I have not felt so strong since I was ill."

"But you are very snug here, in the waggon. Why do you want to leave it?"

"It is very nice, but I want to ask you—Bennie darling, you won't be vexed with me? Don't you think it's very near telling a lie not telling the man that it was the fever had?"

"Lie or no lie, it must not be told. He 'd just bundle us out neck and crop. Mrs. Harris would never have let us in only I told her it was decline that ailed you, and you went and let out the truth, you little donkey. There, don't fret, dear; it did not really matter much, because, as I told you before, I met a policeman that seemed to know me, and so we must have left London soon. Why, what are you crying for, child?"

Poor Fan! She was indeed crying bitterly. Never, in all her short and somewhat sad life, had her tender heart been so sore as now. Her father and mother told lies, and did many other things that were not right, but Ben had been so little at home that he had not been tempted to say or do anything in her presence which would have betrayed to her his true character. Loving him as she did, and always finding him kind and affectionate, the poor child had believed him to be nearly as good as Miss Alice herself, and this was, therefore, a terrible blow to her.

"Stop crying, Fan! Don't fret, dear," said Ben, kissing her.

"Oh, Ben dear! Don't you know you must not tell lies? Oh, whatever shall I do, my own darling good Bennie? I'm so sorry for you."

"Don't be a little fool," he answered, kissing her again. "'You' shan't need to tell any; I'll say all that's wanted, and you need only hold your tongue."

"But—but it hurts me that you should do it, Ben. Wait a moment, and I'll tell you why."

She thought for a moment, knitting her brows with the effort to remember something.

"It is a hard verse, and I forget part; it's about the New Jerusalem—that's heaven, you know. Now listen."

She did not remember the words very correctly, and Ben listened with a half smile, as she stumbled through them; but the last verse she knew very well, and it came out clear and distinct, making him start slightly.

"'Neither whatsoever worketh abomination, or maketh a lie.' So you see, Ben dear, we must not tell lies, or the gates of pearl will be shut, and never let us in at all."

What Ben might have said, I do not know, for at that moment John Ellicott lifted the awning close to where Fan sat, and said, gruffly—

"I'm going to start now so give back those cups and plates."

Out jumped Ben, returned the articles in question, paid for the breakfast, and helped to put the horses to. Very soon they were jogging along the road again, but the pleasure of the drive was over for poor Fan.

For about four miles they went at a steady pace, Ellicott keeping by his horses' heads, and saying never a word. But at last they came to a cross-road. Here he stopped the waggon, and addressed Ben, who was sitting in front with Fan on his knee.

"Now, yu young fellow," he said, quietly, "get ye out o' thot. I was alongside of ye this morning longer than ye thought for, and I know that it was fever the child had, and that you're hiding from the police. P'raps I did ought to give yu up to the police, for it's my belief you're a bad sort, but I can't do it, 'cause of the innocent child there. You see yon road? I'm going straight on, and you take that road, and don't cross my path no more, or I'll make you wish you had kept out of it, with your tricks and your lies. There's your bundle: good-bye, child, and I wish yu a better caretaker nor he."

"There couldn't be a better," Fan exclaimed, with tearful emphasis. "He's so good to me, sir, you don't know."

Not a word did poor Ben say. His face was crimson, and he could not look his accuser in the face, as he jumped out of the waggon, and set off along the road pointed out to him, with Fan trotting tearfully at his heels.

At last, he slackened his pace, remembering her weakness, and Fan stole up to his side.

"Oh, Ben! Wasn't he angry?" she ventured to say. "I was so frightened. Were you frightened, Ben?"

"Frightened! Not I. Hard words break no bones. Never mind, Fan; we'll do well enough now. We're a good way out of London. Only you see for yourself, now, that it won't do to tell everything to every one."

Fan said nothing, but her heart was very heavy. She was soon tired, too, poor child; and then Ben took her on his back, and carried her a few miles, but that soon wearied him. Then they came to a little village, where they bought bread and milk and a lodging for the night. In the morning, Ben went all over the place seeking for work, but it was a very small place, and no one wanted a strange lad: there was no haymaking at that time of the year, and the harvest work was very light, as it was a grazing district. So the forlorn pair journeyed on, in hopes of reaching some place where they might find work.

Now, although Ben put a bold face on the matter, he was beginning to get frightened, for the few shillings he possessed were melting rapidly; and though Fan was certainly gaining strength every day, she could not walk very far yet, and a few days of insufficient food would probably kill her. The nights, too, were getting cold, so that it was no longer a good joke to sleep under a hay-rick, or in a dry ditch, and these were the only beds they could now afford.