Title: Bear and forbear

or, The young skipper of lake Ucayga

Author: Oliver Optic

Engraver: Samuel Smith Kilburn

Illustrator: Reimunt Sayer

Release date: November 4, 2025 [eBook #77177]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1869

Credits: Terry Jeffress and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Books project.)

THE LAKE SHORE SERIES.

OR, THE

YOUNG SKIPPER OF LAKE UCAYGA.

BY

OLIVER OPTIC,

Author of “Army and Navy Stories,” “Great Western Series,” “Onward

and Upward Stories,” “Woodville Stories,” Famous “Boat-Club

Series,” “The Starry-Flag Series,” “Young America Abroad,”

“Lake Shore Series,” “Riverdale Story-Book,”

“Yacht-Club Series,” and “The

Boat-Builder Series.”

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS.

NEW YORK:

CHARLES T. DILLINGHAM.

[2]

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, by

WILLIAM T. ADAMS,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

ELECTROTYPED AT THE

BOSTON STEREOTYPE FOUNDRY,

No. 19 Spring Lane.

[3]

TO

HELEN HAMLIN, FRANK HAMLIN, JARVIS L. CARTER,

EDWARD STETSON, CHARLIE HAMLIN, ISAIAH STETSON,

ADDIE HAMLIN, MARY STETSON,

AND “A THOUSAND AND ONE OTHER BOYS AND GIRLS” OF THE

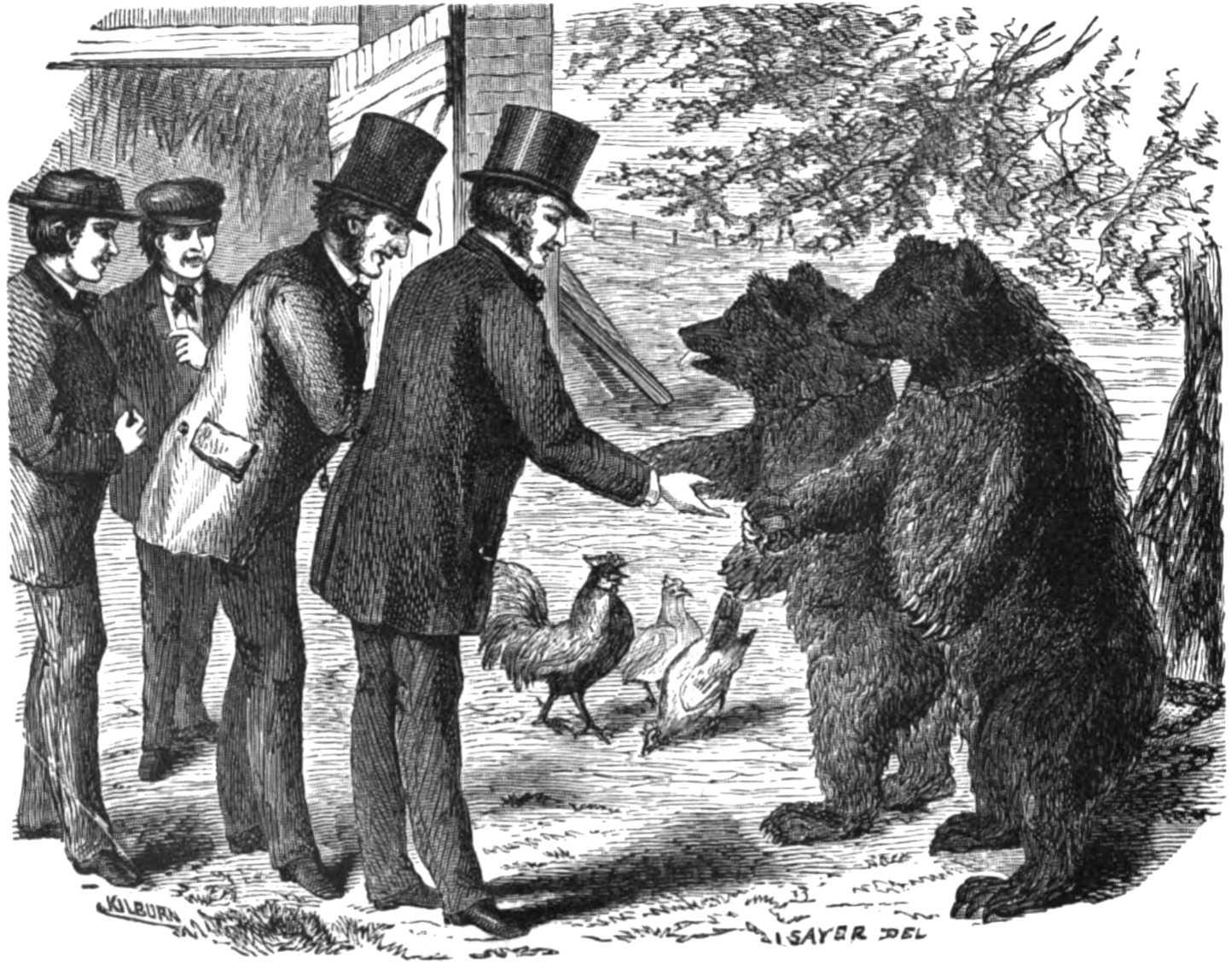

CITY OF BANGOR, WHO SENT ME A BLACK BEAR, IN TOKEN

OF THEIR LOVE AND ESTEEM, ADMONISHING ME

NOT TO EAT HIM, BUT TO INSTRUCT AND

TO PRESERVE HIM FROM THE EVILS

OF THIS WICKED WORLD,

This Book

IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED.

Though I did not eat him, nor any part thereof, and his life was too short to permit him to profit by any instruction I might have been able to give him, yet he is preserved from “the evils of this wicked world” at the rooms of the Society of Natural History, and I hope my readers will profit by the story he suggested.

O. O.

[4]

THE LAKE SHORE SERIES.

[5]

“Bear and Forbear” is the sixth and last of the Lake Shore Series, and was one of the serials which appeared in Oliver Optic’s Magazine. The story itself is complete, and independent of its predecessors, though the characters that have been prominent in the other volumes of the series are again presented, to be finally dealt with according to their several deserts. The writer has endeavored to show that fidelity to duty prospers even in this world, and that evil doing brings pain and misery; and if he has awarded “poetical justice” to each, it will only make the contrast the more evident.

The author has endeavored to make a proper use of the Christian precept which forms the principal title; and he trusts that his readers, both young and old, will be able to deduce the moral from the story, and, profiting by it, be enabled to avoid such disagreeable ruptures as that which threatened the peace of the two communities in the story, but which the “two bears” happily prevented.

[6]

In closing this series, the author desires once more to thank his juvenile and his adult friends for the kind consideration they have always extended to him, and for the increasing favor bestowed upon his efforts to please and to instruct.

Harrison Square, Boston.

June 1, 1870.

[7]

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| On Board the Belle. | 11 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| A new Acquaintance. | 22 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| An angry Guardian. | 33 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Fire on the Lake. | 45 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The rescued Passenger. | 57 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The English Lord and the Drummer. | 69 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Miss Dornwood’s Story. | 82 |

|

[8] CHAPTER VIII. |

|

| The strange Boat. | 94 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Robbery of the Centreport Bank. | 107 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Robbers separate. | 119 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| A little Spark kindles a big Fire. | 131 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The Landing of the Robber. | 142 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Tom Walton wounded. | 153 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Robber takes the back Track. | 164 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Robber in a Trap. | 175 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Showers of Rocks. | 187 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| A Blow with the Boat-hook. | 198 |

|

[9] CHAPTER XVIII. |

|

| At the Cataract House. | 209 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The other Bank Robber. | 221 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The End of Lord Palsgrave. | 232 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| The Adventures of Nick Van Wolter. | 243 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Colonel Wimpleton’s Wrath. | 254 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Major Toppleton explains. | 265 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Bear and Forbear. | 276 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Miss Dornwood’s Guardian. | 287 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| The Young Skipper of the Banshee. | 298 |

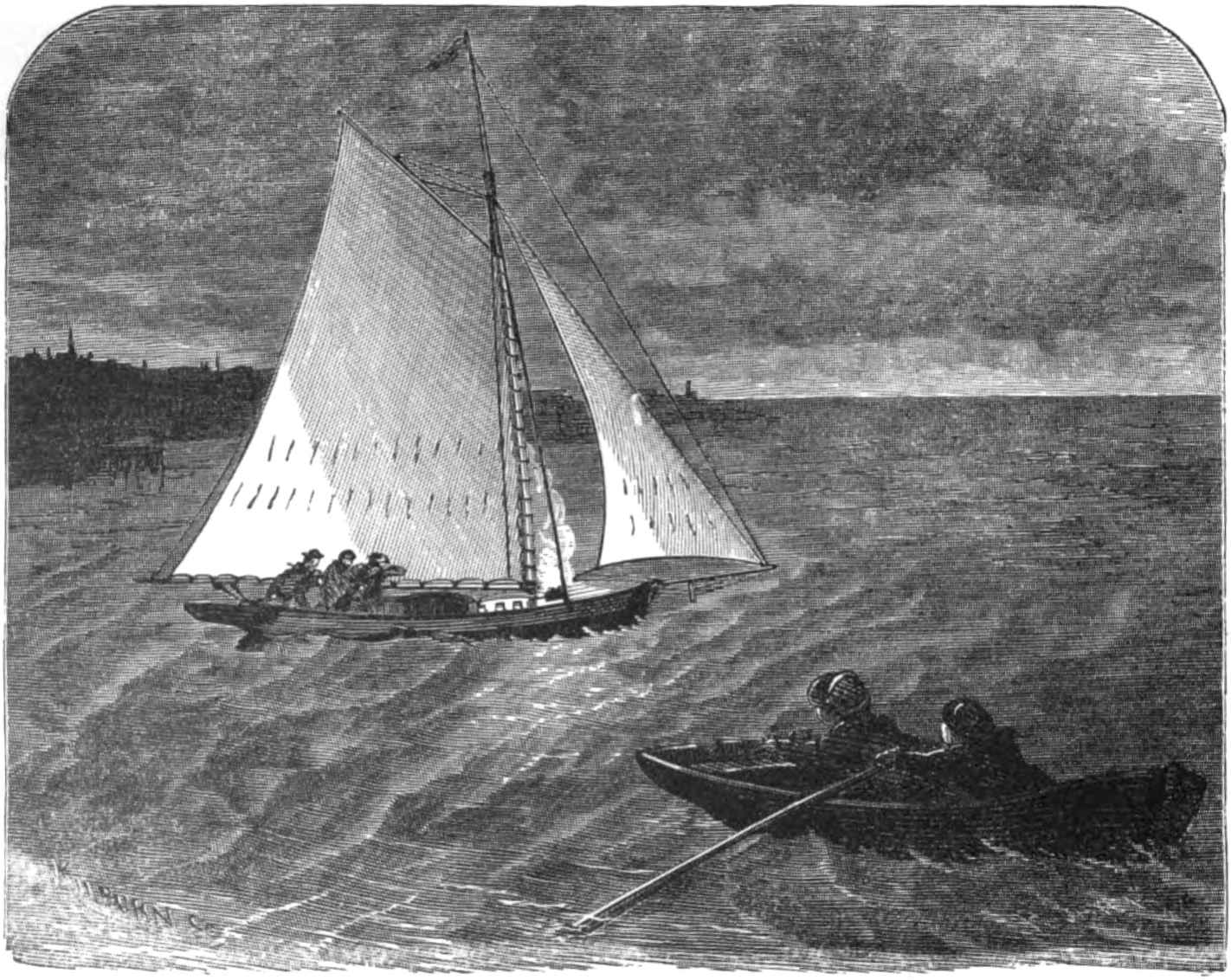

“Wolf, I am about ready to buy this boat, if you are about ready to sell it,” said Tom Walton, as we were sailing up the lake in the Belle.

“I’m quite ready to sell it to you, Tom,” I replied.

“You ought to own her by this time, Tom,” added Waddie Wimpleton, who was one of the party.

We were going up the lake to have a good time; in other words, it was vacation with me. When Tom Walton spoke, I was thinking of the events [12] of the past, as the sail-boat glided swiftly over the clear waters of Lake Ucayga. I was the general agent of the Union Line, which now included the Lake Shore Railroad and the Ucayga Steamboat. The two millionnaires, who had fixed their residences on opposite sides of the lake, at the Narrows, where it is only one mile wide, had been the most bitter enemies for years, taking up the hatchet after a long period of the most intimate and friendly relations. Major Toppleton had built the Lake Shore Railroad as a plaything for the students of the Institute established on his side of the lake, in order to give them a thorough and practical knowledge of railway business. The idea had grown on his hands till the road had become a very important channel of travel. Buying up the stock of the old steamers on the lake, he had obtained the control of them, and ran them in connection with the railroad. This movement gave Middleport, on the major’s side of the lake, a very great advantage over Centreport, where Colonel Wimpleton resided.

Then the two great men became rivals for the business of the lake; and the colonel built a large [13] and splendid steamer, to run in opposition to the railroad, which, by its great speed and elegant accommodations, had carried the day against the railroad. The students of the Wimpleton Institute were formed into a company, and nominally managed the affairs of the steamer, thus obtaining an insight into the method of conducting business in stock companies. I had been a kind of shuttlecock between the rival magnates, and had been successively employed and discharged by each. The war between the two sides of the lake had extended to the families of the principal parties, and the inhabitants of the large towns in which they lived. The two sons of the great men had been particularly hostile; but, having mended their ways, and, from vicious, overbearing, tyrannical young men, becoming kind, gentle, and noble, they buried the hatchet, and their relations were pleasant and friendly. By their indirect efforts, with some help from me, the feud between the fathers had been healed, and they were now warm personal friends. The railroad and steamboat lines had been united, and were now running in connection with each other.

[14]

I am not disposed to say much about my own agency in bringing about this happy state of things, though I had labored patiently and persistently for years to accomplish the result. I was happy in the achievement, and not inclined to apportion the credit of it among those who had brought it about, except to award a very large share of it to the sons of the two magnates. The two lines had been running in connection about two months. As the general superintendent of the united line, I had gone over the entire route daily until everything worked to my own satisfaction, as well as to that of the traveling public. As captain of the steamer, I had been constantly employed all winter, and I felt disposed to play a few days. It was vacation at both the Institutes, and Tommy Toppleton had gone to one of the great watering-places with his father and mother, though the time fixed for their return had arrived. Waddie Wimpleton had accepted an invitation to spend a few days on a cruise with me up the lake. We intended to live on board of the Belle, and spend the time in fishing, sailing, and rambling through the wild region.

[15]

I had bought the Belle at auction, at a time when I was out of employment, having been discharged by Major Toppleton from my situation as engineer on the Lake Shore Railroad. She had cost me a very small sum, compared with her value, and I intended to make my living by taking out parties in her. But, as I was very soon appointed to the command of the steamer, I employed Tom Walton to run her for me; and he paid me a portion of the receipts. He had done well for himself, and well for me, in her. Tom was a very honest, industrious, and capable fellow, and supported his mother and the rest of the family by his labor. I had told him I would sell the Belle to him at a fair price, any time when he wished to buy her. I had been rather surprised that he did not avail himself of this offer, for my share of the earnings of the boat had already paid me double the amount she had cost me.

“I think of going into the general navigation business,” said Tom, with one of his good-natured laughs; “and if I can buy her, I will do so.”

“You can, Tom,” I replied.

“My mother has been sick a good deal for the [16] last two years, and it took about all I could make to take care of the family, or I should have bought her before.”

“I’ll trust you, Tom,” I added.

“I don’t want anybody to trust me, except to keep the folks from starving. I didn’t mean to buy that boat till I had money enough to pay for her. I’ve got a little ahead now.”

“How much have you, Tom?” I asked.

“I haven’t enough to bust the Middleport Bank yet. You’ve used me first rate, Wolf, and I don’t mean to cheat you on this boat. After all, whether I buy her or not rather depends on what you ask for her.”

“You shall have her for what she will bring at auction.”

“What will she bring at auction?”

“I don’t know.”

“I don’t think I can buy her, then, for I know a man in town who will start the bidding at one hundred and fifty.”

“Do you? Well, I had no idea any one would give that for her,” I replied.

[17]

I saw that Tom was troubled, though he still kept his face alive with his usual smile. I would have given him the boat at once, only the offer to do so would wound his pride and hurt his feelings, for, poor as he was, he had the instincts of a gentleman.

“I shall make money by buying the boat, Wolf, and I want her badly, but not enough to run in debt for her,” added he.

“Suppose we do as Major Toppleton and Colonel Wimpleton did on the steamers.”

“What’s that?”

“Mark.”

“I’m willing to mark; but I’m afraid I can’t hit your figures, Wolf, for the Belle is a valuable piece of property. I ought to know that, if no one else does.”

“You write what you are willing to give, and I will write what I am willing to take. If my figures are lower than yours, they shall be the price of the boat, and the trade is completed.”

“Your figures?”

“Yes.”

[18]

“Why not my figures, if they are higher than yours?”

“If you give all I ask, that’s enough. If my figures are higher than yours, we will split the difference,” I continued, handing him a pencil and paper.

“That’s fair, so far as I am concerned; but don’t you cheat yourself, Wolf,” replied Tom, taking the paper and making his figures upon it, after considerable hesitation.

“You needn’t worry about me, my dear fellow. Give your figures to Waddie. He shall stand between us,” I added, as I wrote my own valuation, and handed it to him.

“There is considerable difference in your estimates,” laughed Waddie. “What am I to do?—split the difference?”

“Not unless my figures are higher than Tom’s.”

“They are not, Wolf. Tom’s are a mile and a half higher than yours.”

“Then the boat is sold at my price,” I added.

“Cheap enough!” exclaimed Waddie.

“What are the figures?” asked Tom.

“You marked one hundred and fifty dollars, Tom, and Wolf marked fifty dollars. So the Belle is sold.”

[19]

“So am I,” said the skipper.

“Are you not satisfied?”

“No; I feel just as though I had been overreached. See here, Wolf Penniman; I didn’t mean to have you give me this boat.”

“I haven’t given her to you.”

“I supposed you would ask three or four hundred dollars for her.”

“I am satisfied, Tom. I have made money out of her, and now I get back all she cost me.”

“But don’t you think it’s an insult to the Belle to sell her for fifty dollars?” laughed Tom.

“If she does not complain, you need not.”

“Wolf, I don’t feel exactly right about it. I have a kind of an idea that you have taken pity on me, for a poor, miserable fellow as I am, and given me the boat.”

“No such thing, Tom!” I protested.

“Didn’t I say there was a man in town that would bid a hundred and fifty dollars on her if she was put up at auction?”

“I don’t know him, Tom; and I’m afraid he would not use her kindly. The Belle is yours.”

[20]

“I can afford to give you a hundred for her without busting the Middleport Bank. Don’t you think I’d better do it?”

“Certainly not, Tom. A trade is a trade.”

“But I feel just as though I had stolen her.”

“Don’t feel so, my dear fellow. I will give you a bill of sale when I can get something to write it with. It’s all right now, Tom. ‘Be virtuous and you will be happy,’ and your boat will sail all the faster for it.”

“I am happy, Wolf I have saved up about one hundred and fifty dollars. I thought that would almost buy the Belle. Now I’m just a hundred in. I’m going into the general navigation business, and I want some more boats, to let, and I’m lucky enough to have the capital to invest in them. I shall buy some row-boats, for there are lots of people that want to hire them.”

“I have no doubt you will do a good business letting boats, Tom. Rowing is a great art, and a healthy one. But have good boats. Don’t buy poor ones because they are cheap.”

“Not I, Wolf; my boats shall be first chop, ‘A, [21] No. 1, prime.’ But I suppose you gentlemen want some dinner—don’t you?”

“We do want some dinner, Tom,” I replied. “I make a business of attending to that matter every day.”

“Exactly so, Wolf. That’s just what you thought the last time you thought so.”

“Eating dinner I have always found to be a healthy amusement, and I intend to follow it up as long as I live, and can get any dinner to eat,” I replied.

“You will always get it, Wolf, for you are a rich man now; and you will die worth a million, if you don’t die before you have a million. Now, if you will take the helm, you shall have a beefsteak and some baked potatoes, first chop, A, No. 1, prime, in about half an hour, more or less, but rather more than less.”

I took the tiller, and Tom went into the cuddy to prepare the meal. In half an hour, more or less, we had the beefsteak and baked potatoes, smoking hot, done to a turn, and just as nice as the best hotel in the country could furnish.

[22]

We left Middleport early in the morning, and when we dined, we were above Priam. We intended to land at a point near the residence of my old friend Captain Portman, to enable me to call upon him. We arrived at this point early in the afternoon. Waddie was not acquainted with my friend, and did not care to call upon him; but he decided to take a walk on shore, and we proceeded together till we came to the entrance to Captain Portman’s grounds. He was a wealthy gentleman, who had chosen this wild region for his residence, for he was a genuine lover of the beauties of nature, and enjoyed them as much in the winter as the summer.

The country was exceedingly wild and rugged. The rocks rose in precipitous steeps at times, and [23] there was a profusion of cascades and cataracts. One might follow a stream through the depths of the primeval forests, and find it leaping from the precipices a dozen times in a single mile. In the midst of this magnificent scenery Captain Portman had built his mansion, selecting a rugged steep for its site; and here Nature and Art had joined hands to increase the loveliness of the place. Half a mile from his house, on the road to Priam, was the Cataract House—a hotel which had received its name from a grand and beautiful waterfall in the vicinity. At this house, during the summer, many wealthy people boarded.

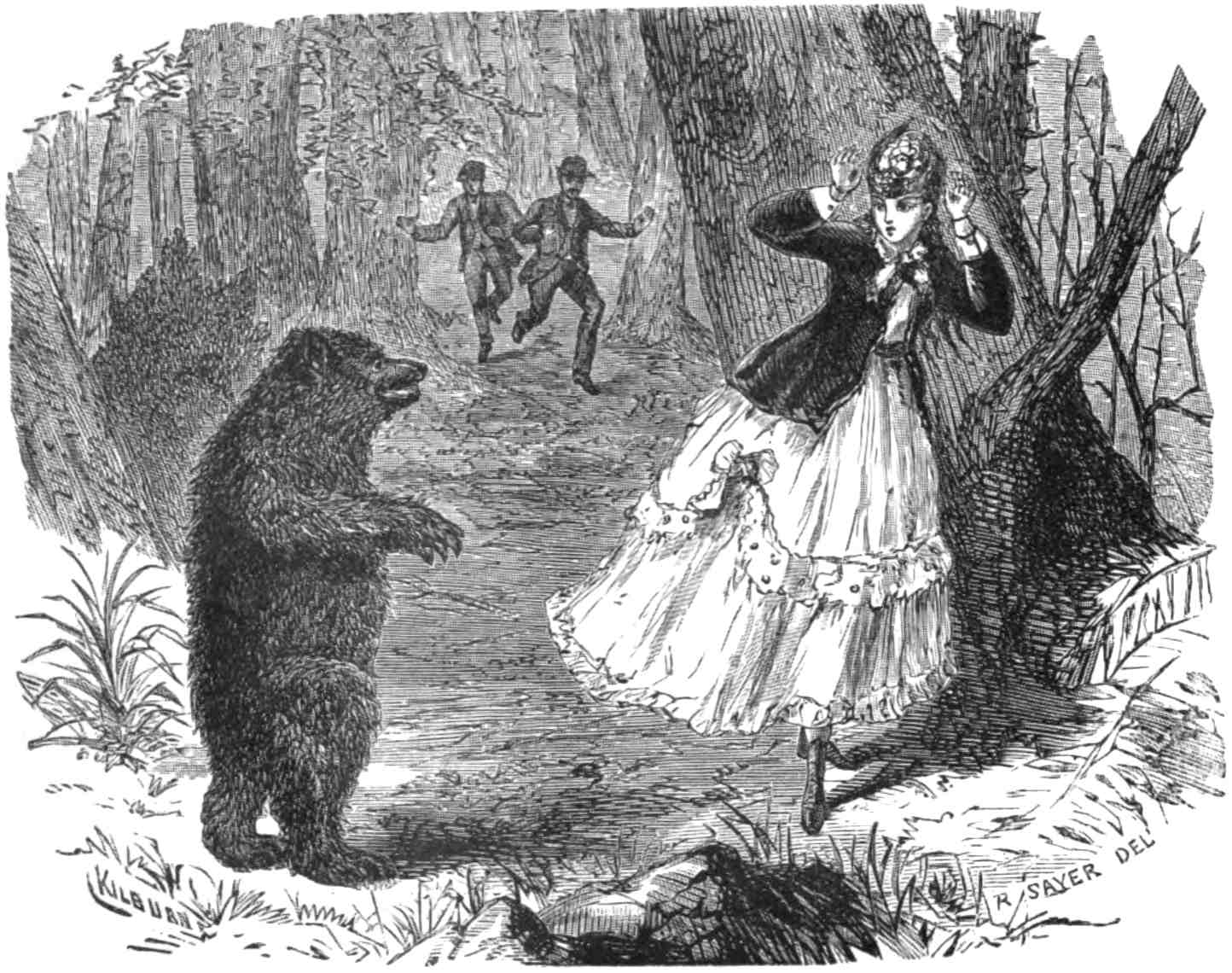

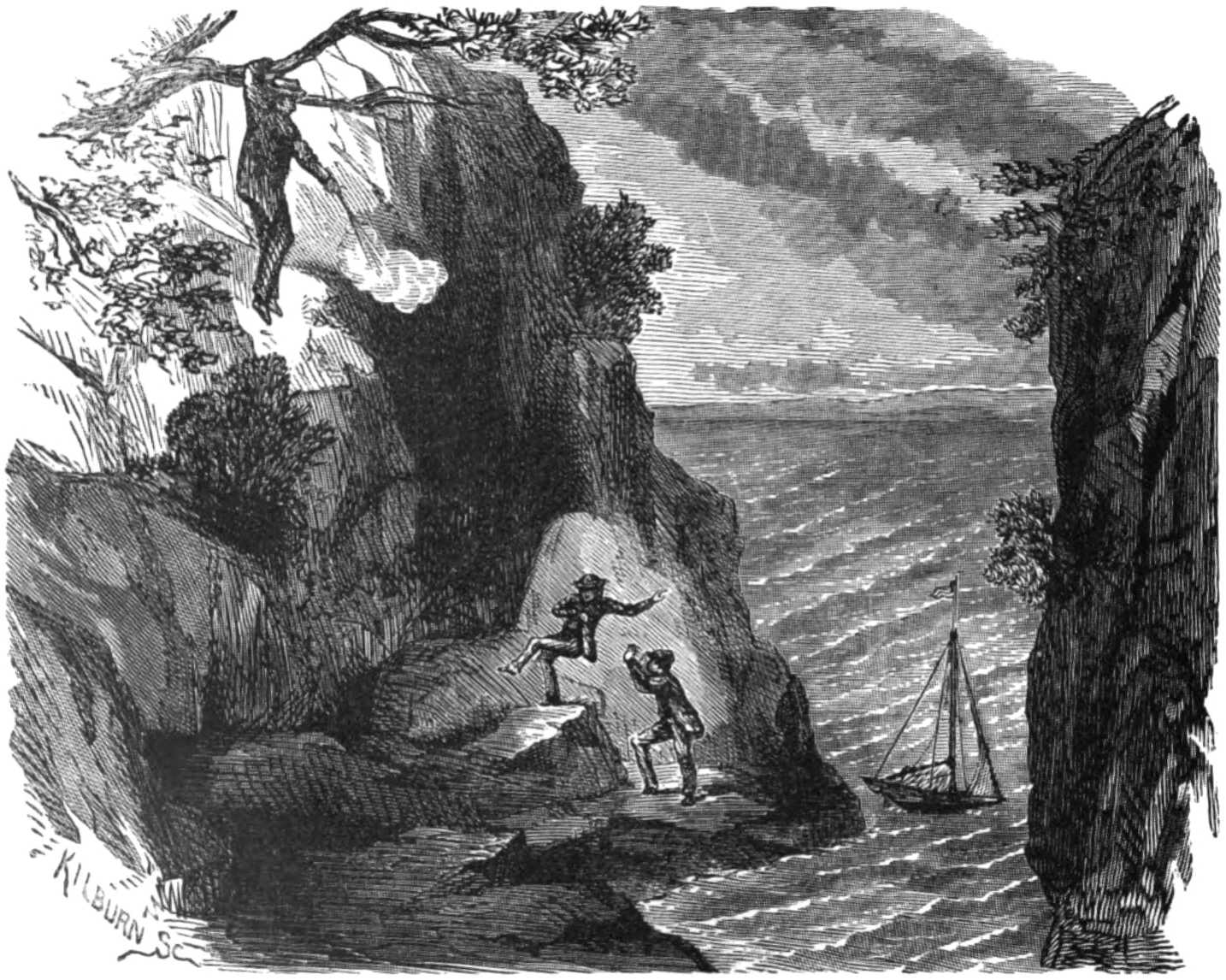

When we reached the road which leads from Hitaca to Priam, Waddie turned to the right and I turned to the left. I was about to enter the rustic gateway which opened into the estate of Captain Portman, when I was startled by a succession of shrill screams. I saw Waddie spring into the woods which bounded the road on the left. The voice of the person in distress—for I supposed no one would scream unless in distress—was that of a female. Of course I was interested; and, turning [24] from the gateway, I rushed down the road, and followed Waddie into the woods.

I had made such good time that I overtook my fellow-voyager before he reached the scene of the adventure. The trees were very large, and the grove had been cleared up on the ground for the convenience of the visitors at the Cataract House, so that we could see some distance; and we soon discovered the person who had uttered the terrific screams. She was a young lady, elegantly dressed, and apparently not more than seventeen years old.

“Help! Help!” she cried, as she stood apparently paralyzed.

But we could see nothing to alarm her, though we discovered a young gentleman in the distance “making tracks” in the direction of the hotel.

“What is the matter with her?” asked Waddie.

“I don’t see anything to frighten her.”

“I do,” added Waddie, as we stepped forward, and discovered a small black bear, which a huge tree had before hidden from our view.

“A bear!” I exclaimed.

The creature stood up on his hind legs, and was [25] reaching forward with his right fore paw towards the young lady, while the left was dropped at his side. For my own part, I do not remember that I had ever even seen a bear before, and I confess that I did not like the looks of him. Whether Waddie shared my feeling or not I do not know; but he quickened his pace, and soon placed himself by the side of the interesting sufferer. Neither of us had a club, knife, or other weapon, and we were not in condition to face a wild beast.

“Save me!” gasped the young lady.

“I will conduct you to the hotel, if you please,” said Waddie, hardly noticing the bear, which still sat upon his haunches, with his right paw extended towards the terrified maiden.

“O, dear me! I cannot move,” sighed she.

Waddie took her by the arm, and supported her. As they moved off, the bear followed.

“He’s coming!” cried the lady; and, afraid that the awful monster would pounce upon her behind, she halted and faced him again.

The moment they stopped, Bruin stood up on his haunches again, and held out his paw as before. I [26] came to the conclusion that if he intended to eat any one up, he would have begun before this time, and I ventured to place myself between him and the lady. This brave movement on my part seemed to afford the lady some relief; but she clung to Waddie as though she expected to be devoured, brown silk dress, laces, ruffles, and all. The bear looked at me a moment, as I stood about a rod distant from him. Dropping upon all fours again, he cantered towards me. I was inclined to beat a retreat, but somehow the animal did not seem to be as ferocious as wild beasts have the credit of being, and, though it required no little resolution on my part, I decided to stand my ground.

The bear was about the size of a full-grown Newfoundland dog, but broader across the back, and much heavier, weighing, I judged, over a hundred pounds. He opened his mouth as though in the act of laughing. I had had no experience with wild animals, but I had an idea that they howled and made a “general row” when they were savage, and intended to do mischief. After the first sight of the bear, my courage gradually increased, and I [27] am happy to say that I did full justice to my valor on this occasion. I did not run away. The bear came close to me, and then erecting himself again, he extended his right paw as before, looking up into my face as pleasantly and cunningly as though he had been a playful child.

The fellow evidently means something by his action; but I was not sufficiently skilled in bear nature to comprehend him. He was not savage, and did not exhibit the slightest intention to use the fine rows of elegant teeth which he displayed. This assurance was very comforting to me. I retreated two or three paces as a strategic movement, in order to develop the further intentions of the enemy, if he was an enemy. The rascal followed me, again stood up, and presented his paw.

“Don’t be afraid, miss. He will not hurt anything,” said I, as the young lady was again alarmed by the last move of the bear. “He is quite harmless.”

“I am afraid he will bite me!” gasped she; and she would not have suffered any more if she had already been bitten.

[28]

“Shall I leave you, Wolf?” asked Waddie.

“Yes, certainly; the bear is as harmless as a kitten,” I replied.

“Allow me to conduct you to the hotel,” added Waddie, gallantly. “I suppose you are staying at the hotel.”

“Yes; I had been walking with Lord Palsgrave, when that awful creature came upon me,” she replied.

“Whom did I understand you to say you were walking with?”

“With Lord Palsgrave.”

“Ah, then you are English people?” added Waddie, who was doubtless duly impressed with the quality of his new acquaintance.

“Lord Palsgrave is English, but I am not.”

“If you will allow me, I will conduct you to the hotel.”

“I am so frightened, I fear I cannot walk so far.”

“You need not leave on account of the bear,” I interposed. “He is as gentle and tame as a baby kitten.”

By this time I had discovered what Bruin meant by his mysterious movement with the right fore paw. [29] When I had worked my courage up to the sticking point, I extended my hand towards him, to see if he would snap at it. If he did, I concluded that I should use a big stone which lay on the ground at my feet. If he wanted to fight, I felt that, in the cause of a terrified maiden,—very pretty, too, at that,—I could afford to test the relative hardness of the bear’s head and the rock.

But I wronged him. The bear had no belligerent intentions. He was evidently a good fellow in his way; and, if bearish in his manners, he was friendly in his disposition. Instead of snapping at my hand, he reached forward his paw, and I realized then that he only desired to shake hands with me. I had learned a sufficient amount of politeness to accommodate him in this respect, and when I took his paw he bowed his head several times, to indicate his pleasure at making my acquaintance. I could not suffer myself to be behind him in courtesy, and I bowed as often as he did.

I heard Waddie laughing heartily, and turning round, I saw that the young lady was beginning to smile at the passage of compliments between me and [30] the bear. I must say that I was delighted with my new acquaintance, he was so very polite and well mannered. But I had not yet measured the depth of his affection for me. He was not satisfied with merely bowing and shaking hands with me, but insisted upon hugging me. First he embraced my arm, and then my body, though I did not yet feel quite well enough acquainted with him to endure the final transport of his devotion. I shook him off, and he tumbled upon the ground. Then he began to roll over, as a dog is taught to do, making the most extravagant demonstrations of affectionate regard towards me. In a few moments I was rolling on the grass with him, and I felt confidence enough in his good intentions to return his embraces. I put my hand in his mouth, but he did not bite; and though his sharp claws were rather trying to the nap of my coat, he used them only in sport.

“Won’t you come up and shake hands with him, Miss—”

“Miss Dornwood,” she added, supplementing my question. “No, I thank you. I thought he was a wild bear.”

[31]

“No, he is as tame as a kitten. He only wanted to shake hands with you. I am sure he would not hurt any one.”

“He is real funny; and I wish I dared to play with him,” added she, shrinking back, as Bruin followed me a little nearer to the place where she stood.

“Don’t bring him any nearer, Wolf,” laughed Waddie. “‘Distance lends enchantment to the view.’”

I sat down upon a rock, and continued to play with the bear, while Waddie and Miss Dornwood watched the sport at a respectful distance.

“I don’t know what I am to do with this fellow, now I have made his acquaintance,” I continued, as I tumbled him over upon the ground when his embraces became a little too ardent. “I see by the looks of his neck that he has been in the habit of wearing a collar.”

“If you will only keep him away from me, I don’t care what you do with him,” said Miss Dornwood. “I don’t think they ought to let such creatures wander about these grounds, for it is almost as bad to be frightened to death as to be eaten up.”

[32]

“Where is the gentleman who was with you?” asked Waddie.

“He went to the hotel after a vehicle, for we intended to take a ride along the lake when we saw this road. We only arrived this morning, and we find it a very beautiful region.”

“There come three men,” added Waddie, pointing into the woods.

I recognized Captain Portman as one of them.

[33]

“How do you do, Captain Penniman? I am delighted to see you,” said Captain Portman, coming up to me, and extending his hand.

As I took his hand, a burst of laughter from Waddie and Miss Dornwood attracted my attention. Turning my head to ascertain what amused them, I saw the bear standing on his hind legs, and extending his paw, as he had done to me, evidently wishing to shake hands with the new comer. Captain Portman took his offered paw, and gave Bruin a warm greeting.

“So, my old rogue, you have got away again,” said he, as he patted the bear on the head.

“You seem to be acquainted with my old friend here,” said I.

“Yes, he belongs to me; but he bothers me sadly,” replied Captain Portman. “Unless we buckle his [34] collar very tight, he slips it over his head; and if it is tight, it worries him and makes him cross. He has got out of my grounds several times, and frightened strangers staying at the hotel. The landlord says he will shoot him, if he finds him loose again.”

“He frightened this young lady,” I added.

“I am very sorry,” said Captain Portman, turning to the lady. “He is entirely harmless.”

“I see he is now, sir; but I supposed he was a wild bear,” replied Miss Dornwood.

“When I knew he was loose, I hastened to find him, lest the landlord should put his threat into execution,” continued Captain Portman, caressing the bear. “He makes so much trouble that I am afraid I shall have to get rid of him; but I do not like the idea of killing him while he makes himself so agreeable. If you will take him, Wolf, I will give him to you, for I know you will treat him kindly.”

“Thank you, sir, I should be delighted to own him,” I answered. “I have a nice place for him at home.”

“You shall have him.”

“He and I will be warm friends.”

[35]

And Bruin, as if he comprehended the new relation between us, gave me one of his warmest hugs.

“How do you happen to be here, Wolf, without calling upon me?” asked Captain Portman.

“I was just going up to your house when I heard this lady scream, and I hastened back to her assistance.”

“Gallant as ever,” said he, laughing. “Then I shall see you again to-day.”

“Yes, sir. I will call at your house in the course of the afternoon.”

“My men will take care of the bear for you till you are ready to return to Middleport, if you desire.”

I assented to this arrangement, and the two men who came with Captain Portman took charge of the bear, though he was very unwilling to be separated from me. I should have gone with the captain, but I desired to see Lord Palsgrave, for whom Miss Dornwood was waiting. I had never seen a live lord, and I was anxious to behold the phenomenon. I supposed he would soon appear with the vehicle for which he had gone.

“I am very much obliged to you for the service [36] you have rendered me, gentlemen,” said she, as the party moved off with the bear.

“Not at all,” replied Waddie. “I am very glad, for one, to have served you.”

“And I have made an excellent friend by the adventure,” I added.

“Do you refer to the bear, or to me?” said Miss Dornwood, archly.

“I confess that I referred to the bear.”

“I hope you will include me.”

“Then I have made two excellent friends.”

“Lord Palsgrave seems to be a long time obtaining the vehicle,” she added, glancing towards the road.

“Is Lord Palsgrave an old gentleman?” I asked.

“Dear me! No,” replied Miss Dornwood, with a blush. “He is only nineteen.”

“Nineteen! Well, I had an idea that lords were always old men.”

“Not at all. Lord Palsgrave is quite a young man.”

“Was it he we saw going towards the hotel when you screamed?”

“Yes; he left me only a few moments before I saw the bear.”

[37]

I came to the conclusion, guided partly by the blush which mantled her cheek when she spoke of him, and partly by the fact that his lordship was only nineteen, that he was a lover; and I was rather sorry that she was already entangled, for I thought Waddie regarded Miss Dornwood with more interest than I had ever before seen him look upon a young lady. She was certainly a very pretty girl, and I did not blame Lord Palsgrave for taking a fancy to her.

His lordship did not come with the vehicle, though an hour had elapsed since his departure, and Miss Dornwood was beginning to be impatient. We did not think it was polite to leave her, and we continued to talk about the bear, Lord Palsgrave, and such other topics as we could find available. While we were thus engaged, I saw a lady and gentleman approaching us. As they came nearer, the latter disengaged himself from his companion, and hastened to the spot where we stood. He was a young man of twenty-five, and looked very cross. I did not like the looks of him, and I saw that Miss Dornwood was very much disturbed by his coming.

“What are you doing here, Edith?” demanded he, [38] bestowing a contemptuous glance upon Waddie and myself.

“I am waiting for Lord Palsgrave,” she replied, her cheek flushed, and her lips trembling.

“Who are these persons?” continued he.

“I do not know who they are, but they have been very kind to me, and I am very grateful to them.”

“No doubt you are!” sneered the gentleman; and I realized that we had encountered another bear, though not so well behaved as the first had been. “Do you pick up acquaintances in this manner without my knowledge?”

“Why, Charles!”

I saw that Miss Dornwood was greatly agitated and deeply grieved at this ungentle treatment, and I did not wonder at it.

“What are you doing here?” he continued, rudely.

“I am waiting for Lord Palsgrave.”

“I don’t wonder that Lord Palsgrave does not come, if he sees you engaged in this manner. Do you put yourself on familiar terms with entire strangers?”

“How rude you are, Charles!” exclaimed Miss [39] Dornwood, struggling to repress her tears at his unkind treatment.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” interposed Waddie; “but there was another bear—there was a bear in the woods here. The lady encountered him, and we came to her assistance.”

“A bear!” sneered the gentleman.

“A bear, sir!” repeated Waddie, with emphasis. “It is true, he was a tame bear, but he frightened the lady, and her screams attracted our attention.”

“If you have rendered her any assistance, I am obliged to you for it,” said the gentleman, coldly. “Edith, go back to the hotel.”

“Lord Palsgrave told me to meet him at the road when he came with the carriage,” pleaded the young lady.

“I insist that you return to the hotel,” added the gentleman, almost fiercely. “I have forbidden your making acquaintances without my knowledge.”

“I couldn’t help it, Charles.”

“Will you return to the hotel?”

“No; I will not, Charles! I will not be treated in this rude manner before strangers,” she replied, [40] bursting into tears, and retreating a few paces from her tormentor.

“So, miss! Do you dare to disobey me?” demanded he, his checks red with anger.

“I will not be treated in this manner before strangers,” she replied, with spirit, as she wiped away her tears.

“What will Lord Palsgrave say when he finds you making friends so easily?”

“I don’t care what he says; but I will not be treated like a little child, Charles Overton.”

“We will see! Will you return to the hotel, or shall I carry you there?” said the brute, stepping towards her.

“Neither, Charles,” she answered, retreating a step or two before him. “These young gentlemen came to my assistance when I needed their help, and I am very grateful to them.”

“I trust you have thanked the young gentlemen for their service.”

“I have.”

“That’s enough, then. Now you will return to the hotel.”

[41]

“I will not, Charles Overton. I have obeyed you in all things; but when you insult me before strangers, and insult them too, I will not endure it.”

“Very fine, Edith! But you will return to the hotel, and obey me now, as you always have done.”

“I shall return to the hotel when I am ready to do so, but not before;” and Edith looked as though she meant all she said.

Behind all this there was evidently a history of which Waddie and I were entirely ignorant. I concluded that the irritable gentleman was the young lady’s guardian, and was doubtless armed with proper authority to command and control her. But she was not less than seventeen, and certainly she was entitled to some consideration from him. As she had suggested, he treated her like a little child, and his conduct was rude and ungentlemanly in the extreme. I sympathized with Edith; but I did not deem it proper or prudent to interfere. I saw that Waddie, who was naturally rash and impetuous, found it exceedingly difficult to restrain himself under the provocation.

“Edith, you shall obey me!” exclaimed Mr. Overton, springing towards her, with the intention of dragging her back to the hotel.

[42]

“I beg your pardon, sir,” interposed Waddie, stepping between the angry guardian and his ward. “I hope you will not use any violence.”

At that moment I heard a kind of clattering noise, and turning, I saw the bear rushing at railroad speed towards us. He had doubtless escaped from Captain Portman’s men, and had come back to renew the agreeable acquaintance he had made. Now, Mr. Overton happened to be the nearest person to him as he approached the group, and Bruin leaped up to him, and placed his paws upon the arm extended to grasp Edith. Perhaps he thought the parties were playing, and he wished to have a hand in the game.

Mr. Overton evidently had not seen the bear till he felt his paws upon his arm. A man who is a tyrant is necessarily a coward; and turning his head, the savage guardian saw the bear, with his mouth open. His expression was one of abject terror, and, starting back, he shook the playful animal from him. Bruin immediately stood up, and extended his paw, as though he were ready to make friends with all mankind. To my surprise, Miss Dornwood grasped the paw with her gloved hand, and shook it warmly. Probably [43] she thought that, between the two bears, he was the less savage and bearish.

“You do not seem to like him any better than I did at first,” said Edith, glancing at Mr. Overton, who had retreated to a safe distance. “I suppose I am forbidden to make his acquaintance, but I shall do so.”

Bruin had doubtless been trained to respect ladies, and did not offer any rough familiarities to her, as he had to me. He stood up before her, and received her caresses with a good-natured grin. Mr. Overton, seeing that the bear did not proceed to eat any of us up, regained his sell-possession.

“If you wish to avoid trouble, Edith, you will go to the hotel at once,” said he, renewing the attack.

“I shall not go,” she replied, earnestly.

“Then I shall lead you there.”

And stepping forward to enforce his threat, the bear, perhaps thinking he meant to have a frolic, sprang upon him with extended paws.

“Take him away! Take him away!” cried Mr. Overton, utterly unable to appreciate the familiar overtures of the bear.

“He will not hurt you, sir.”

[44]

“Take him off—will you?” gasped he, in terror.

“Here, Bruin, come here,” interposed Edith, pulling him by the neck.

The bear turned to her, stood up, and extended his paw to her.

[45]

I began to think my bear was as fickle as human beings, for he seemed to have taken quite a fancy to Edith. Certainly, in this respect, I was willing to believe he was a bear of excellent taste.

He did not offer to hug her arm, or to take other liberties with her, but was very affectionate, while he was very circumspect. Mr. Overton did not again attempt to use force with the young lady while she was thus guarded.

“Let the ugly beast alone, Edith!” growled her disconcerted guardian.

“He behaves very well now, Charles, and I am not afraid of him.”

“Once more, are you going to the hotel, or not?”

“Very soon I am, if Lord Palsgrave does not appear,” she replied, still caressing Bruin.

[46]

“I think, Waddie, I will go up to Captain Portman’s, His men are coming again after the bear, and I will take him along with me,” I interposed. “Come, Bruin, old fellow, don’t you know me?”

I put my hand upon his head, and he leaped upon me, as though he was heartily glad to renew the acquaintance.

“I am going to the hotel, Miss Dornwood,” said Waddie, touching his cap to the young lady, and moving in the direction indicated.

She placed herself at his side, and they started together.

“You are not going with her, sir,” said Mr. Overton, angrily.

“Then she will go with me.”

“You young puppy!”

“Gently, if you please, sir,” added Waddie, quietly.

“Stop, Edith!” commanded the guardian.

“You told me to go to the hotel, Charles, and I am going,” she replied.

“Not with that young man.”

“That shall be as he pleases.”

“No; it shall be as I please. Stop, sir! Do you hear me?” cried Mr. Overton.

[47]

“If I understand the matter, sir, you have no control over me, if you have over this lady,” replied Waddie, turning around to address the guardian.

They continued on their walk, followed by Mr. Overton, who was presently joined by the lady he had left when he came forward to discipline his ward. They soon disappeared among the trees, and I made my way to the mansion of Captain Portman, where I spent a couple of hours very pleasantly. I told him about the adventure we had had with Edith and her guardian.

“I pity the poor girl,” I added; “for this Mr. Overton is a petty tyrant, who must make her very uncomfortable.”

“Doubtless it is very unfortunate for her; but it is one of those cases with which outsiders cannot meddle,” replied my friend.

“I think he would have dragged her up to the hotel by force, if the bear had not interfered.”

“Well, the interference came better from the bear than from you.”

“Do you think one ought to stand by, and see a man abuse a young lady without taking her part?” I inquired, with considerable interest.

[48]

“That’s a hard question to answer, Wolf. The gentleman is her guardian, and has authority over her; but if he were actually abusing her, I am inclined to think I should interfere on my own responsibility. Yet it is not prudent to meddle with things of this kind.”

“I am afraid Waddie will meddle,” I added.

“He seemed to be rather interested in the young lady.”

“He should be very careful what he does.”

“I must go over to the hotel, and see that he does not get into trouble.”

“But you will come and spend the night with me, Wolf.”

“We intended to sleep on board of the Belle.”

“I shall be very glad to see you and Waddie to-night, and I hope you will spend a day with me before your return home.”

“Thank you, sir. I will do so, if possible,” I replied.

I walked to the hotel, and found Waddie on the piazza. He looked very nervous and uneasy, and I was afraid something had happened.

“Where is the young lady?” I asked.

[49]

“She is in the house,” he replied. “I was hoping I should see her again. There is something wrong somewhere, Wolf. A man don’t treat a young lady like that unless there is something wrong.”

“It is hardly proper for us to meddle with the matter,” I suggested.

“I don’t purpose to meddle with it, unless he abuses her before my face. If he does that, I shall feel justified in protecting her; for a man has no right to abuse even his own child. But I should like to know something more about the matter,” continued Waddie, warmly.

“Did she say anything to you on your way up to the hotel?” I asked.

“Not a word. We were talking about the bear all the way. Her guardian followed close to us. I know by her sad manner that she is in trouble all the time. After the brute spoke to her as he did, my sympathies were all with her.”

“I don’t think we shall be likely to see her again. This men is evidently her guardian, and he will take care that she does not come out of her room again to-day.”

[50]

“I would give a good deal to know what the trouble is between them. He must be some relation to her, or she would not call him Charles.”

“Very likely. Did you see Lord Palsgrave?” I inquired.

“Not a lord,” laughed Waddie. “I asked the landlord about him, and was told his lordship had taken a horse and buggy, but had not been seen since. Mr. Overton appears to be a little worried about him; but I don’t believe he has run away.”

“I think we shall have to give up the idea of seeing the show to-night,” I suggested.

“We shall be about here a few days, and we will come up to the hotel again,” replied Waddie. “I am ready to go down to the boat when you are.”

“I don’t think there is anything more for us to say or do here;” and we started for the lake.

Tom had put the Belle in good order during our absence, and caught some fish for supper. While he was cooking them, we sat in the cabin, and told him our adventure in the woods, informing him that he would have a black bear for a passenger on the return voyage.

[51]

“If he only behaves himself, I don’t care what he is,” laughed the young skipper.

“If he don’t behave well, you must bear with him,” said Waddie.

“I’ll do that, for I can’t bear to quarrel with anybody, even if he is a bear,” added Tom.

“It is barely possible that he may help you, for he can bear a hand in an emergency,” I continued.

“Does he wear gloves?” asked the skipper.

“No.”

“How can he bare a hand, then?” grinned Tom. “However he will make a good barometer.”

“He knows weather—it rains or not.”

“By the way, Wolf, is he barefooted?” inquired Tom.

“Yes, and barefaced.”

“Can he sing?”

“Certainly; he is a barytone. But, punning aside, I must go home a day sooner, and build a house for him.”

“Baronial halls!” exclaimed Waddie.

“Forbear!” I added.

“What’s for bear?” asked Tom. “Beefsteak?”

[52]

“Not an ounce; he must have no meat. It would make him savage, and then he would eat up all the cats and kittens in the neighborhood, if not the children,” I replied.

“Don’t make a bugbear of him, Wolf,” added Waddie.

“Fish ready!” shouted Tom. “Bear this dish to the table, if you please.”

“Let the table bear it,” said Waddie.

“The fish smells good, and I think my stomach will bear some of it,” I added, as we seated ourselves at the table.

The odor of the dish before us did not belie its quality, and we ate a very hearty supper. For a vacation, this kind of life exactly suited me. I enjoyed the sailing and the fishing very much, and it was delightful o put in at the various points and ramble on shore, while sleeping in the little cabin of the Belle added a new excitement to the cruise. I had begun to think Ucayga Luke was rather too small to afford full scope for the pleasures of such an occasion; and I thought, when I was able, and had the time, a yacht cruise on the ocean would suit me [53] exactly. But the lake was certainly very pleasant, and I was not disposed to complain.

When we had finished our supper, Waddie and I adjourned to the standing-room, in order to give Tom a chance to wash his dishes and put the cabin in order; for three persons about filled it, so that there was little space for one to move around. It was nearly dark, and there was a fresh breeze on the lake. We enjoyed the scene very much, for certainly there is no more beautiful region in the whole world than that which surrounded us. The hills and the precipitous rocks were in strong contrast with the water. The Ucayga was just passing the point where we lay, though on the other side of the lake. Coming from the opposite direction was a tow-boat, dragging slowly after her a fleet of canal-boats.

Waddie and I continued to pun on the bear till the last glimpses of twilight were fading out behind the hills on the opposite shore of the lake. Tom had made up our beds in the cabin, and we were thinking of playing a game of chess, which I had just begun to learn under the pleasant instruction of Grace Toppleton. The lamp on the foremast burned brightly, [54] and the little cabin looked very cosy and attractive.

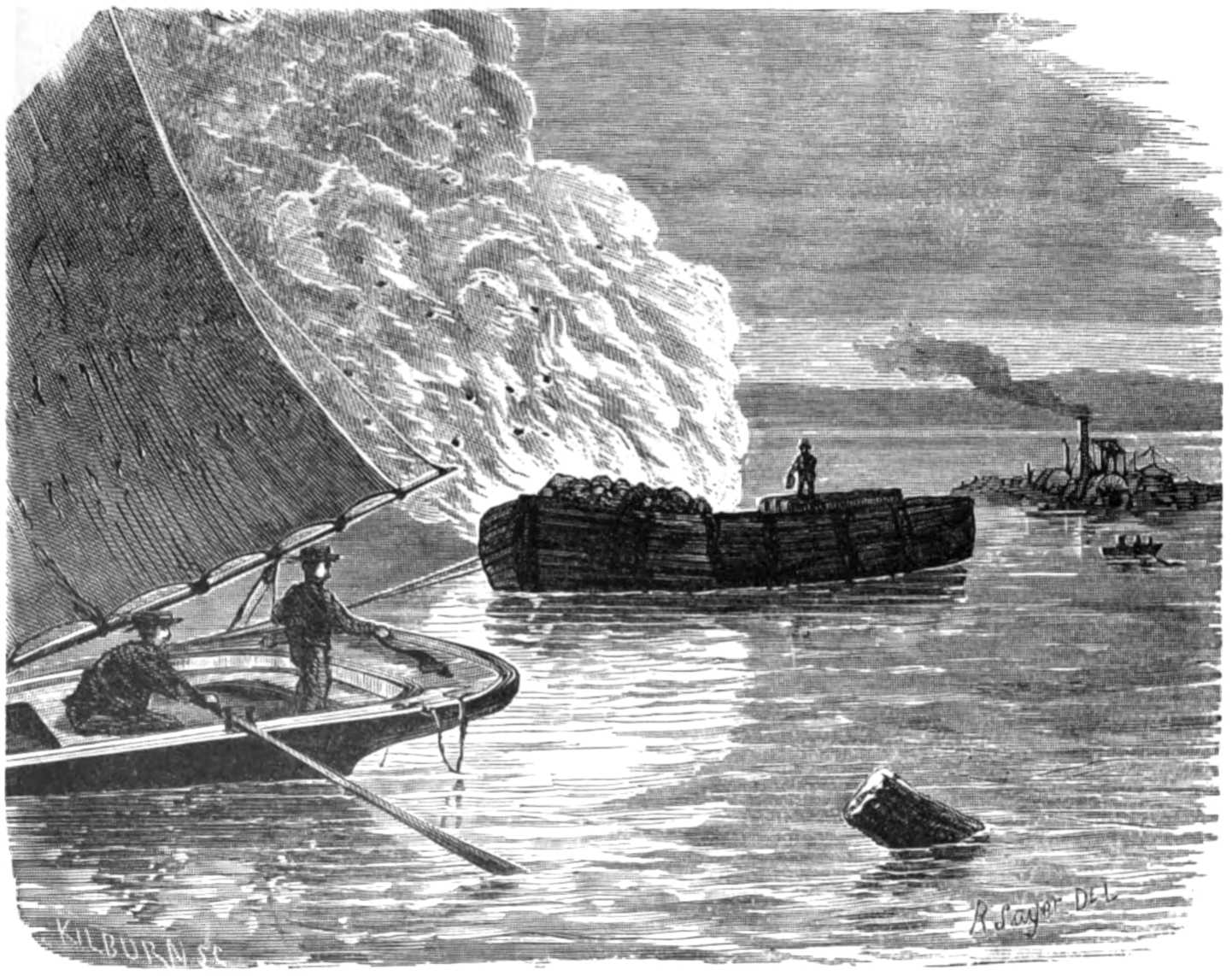

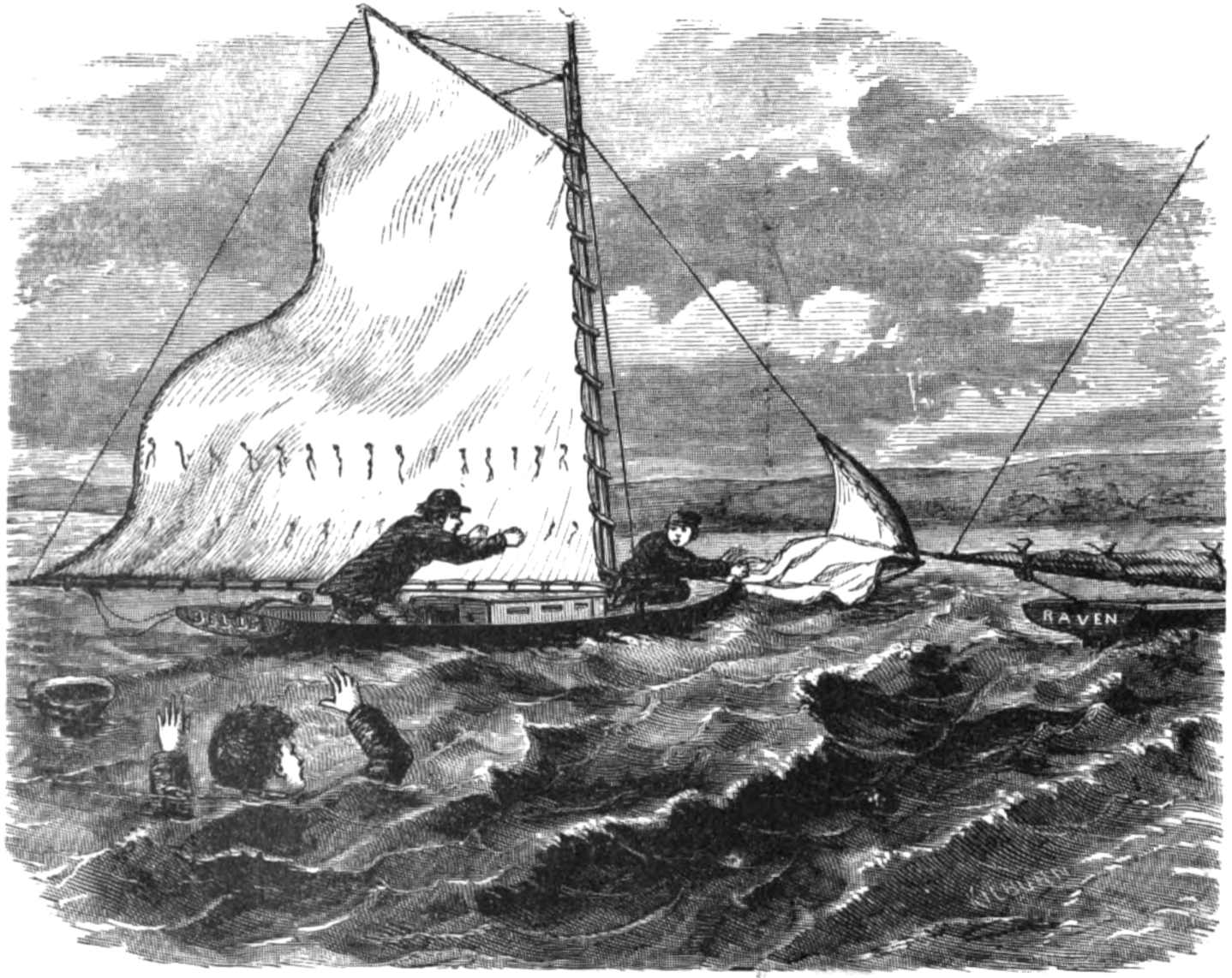

“What’s that?” exclaimed Waddie, suddenly, as a yell from the fleet of canal-beats, which had just passed our anchorage, started us from the quiet of our situation. “By the great horn spoon, one of the boats is on fire!”

“That’s so!” added Tom, nervously. “What shall we do?”

“I don’t know that we can do anything,” I replied, as my companions, by their looks, appeared to appeal to me. “It burns like tinder. I think she must have petroleum, or something of that kind, on board.”

The fire blazed up very suddenly, and it was plain to me that she had some combustible materials on her deck. The hands on the other boats made haste to cast off the fasts which connected the burning craft to their own, in order to prevent the flames from spreading. At the same time, the tow-boat increased her speed to drag the other canal-boats out of the way of their dangerous companion.

“Get up your anchor, Tom. Let us go out there, and see what we can do,” said I. “The thing [55] appears to be drifting this way, and we may be burned up if we stay here.”

“My sentiments exactly,” replied Tom, as he sprang to his cable.

“Stand by the jib-halyards, Waddie,” I added, removing the stops from the mainsail. “Up with it!”

We were all thorough boatmen, and in half a minute we had the Belle under way. As the burning canal boat was dead to windward of us, we had to stand away from her, in order to beat up to her position. As soon as Tom had set the jib, he took the helm, while Waddie and I seated ourselves to watch the progress of the flames. By this time the steamer, having dragged the other canal-boats out of the reach of possible danger, had stopped her wheels, and was getting out a boat to visit the doomed vessel, for such she was by this time, as her deck was covered with one sheet of flame.

“Help! Help!” shouted some one from the boat.

“By the great horn spoon, there is some one on board of her!” exclaimed Waddie, springing to his feet under the excitement of the moment.

“I do not see any one,” added Tom. “Of course [56] those who were on board left her before she cast off from the other boats. They had only to step from one deck to another.”

“Help! Help! Save me!” again shouted the unseen person.

“He must be in the cabin,” I suggested. “The wind drives the flame right over the hatchway, so that he cannot escape.”

“What shall we do?” demanded Waddie, appalled by the prospect of a human being perishing in the flames before our eyes.

“Run up to windward of her, Tom,” said I.

He obeyed, and by the time the Belle reached her bow, I had the cable ready to make fast to her stern.

[57]

The stern of the burning canal-boat was to windward, so that the flames were driven over the entrance to the cabin. I made fast the cable of the Belle to the bow of the burning craft.

“Now, Tom, take the wind on your port beam, and let her drive as hard as she will.”

“I see; you want to sling her round.”

“Yes, Waddie, you and I will help her with the oars, for it will be a hard pull to swing that heavy canal-boat.”

We took the oars; and, when the Belle came up with a jerk, which nearly threw us overboard,—for the wind was quite fresh,—we strained our muscles at the oars.

“Pull, Waddie!” I cried, anxiously, for I felt that the safety of the man in the cabin of the burning [58] boat depended entirely upon the success of our movement.

Tom helped Waddie with one hand, while he steered with the other. Though the burning boat was very long and heavy, it did not require much power to turn her, balanced as she was on the water. The sails of the Belle pulled strong, our efforts at the oars increased the force, and we soon had the satisfaction of seeing that we were accomplishing our purpose. As soon as the vessel began to turn, her inertia being overcome, the work was easy, and we whirled her on her axis like a top.

“Hold on, now!” I shouted, boating my oar. “She will swing the rest of the way without any help. Come about, Tom, and run up to her bow before the fire makes it too warm there to cast off the cable.”

“Won’t you bring my hatchet out of the cook-room, Wolf?” added Tom.

I brought a small hatchet from the cuddy, which Tom used in splitting up his wood.

The canal-boat continued to swing under the impetus we had given her. As soon as she had turned [59] into a position so that the wind struck her broadside, and carried the flames away from the cabin door, we saw a man rush up the steps.

“There he is!” shouted Waddie. “Bear a hand, Tom! Let her drive.”

“She is driving all she will,” replied Tom. “Wolf, we won’t wait to untie that cable; just chop it off with the hatchet when I luff her up.”

“Help! Help!” shouted the man on the after-deck of the canal-boat.

“We will be there in a minute!” shouted Tom. “Keep cool!”

“It’s rather a warm place to keep cool in,” suggested Waddie.

“Now, luff up, Tom, and we will get clear of the cable.”

He put the helm hard down, and, as the boat came up into the wind, the cable lay across the forward deck of the Belle. With one blow of the hatchet I severed it, about thirty feet from the bow of the canal-boat, so that Tom lost only a small portion of his line. The man on deck had seated himself at the extreme end of the boat, with his legs [60] hanging over the water, in readiness to leap into the lake, if the flames were again driven upon him. But the combustible material seemed to be amidships, though the wood-work was now well kindled, and the great volume of the flame was at this part of the boat. Tom ran the Belle around under the stern of the burning vessel, and I fastened the boat-hook to it, as she lost her headway.

“Drop down,” said I to the person above.

He first threw a black leather travelling-bag upon the forward deck, whose contents rattled as though it were filled with old iron. With the assistance of Waddie and myself, he came down himself, and stepped into the standing-room. I picked up his valise, as Tom filled away again, in order that it might not be lost overboard when the Belle heeled over under the pressure of the sails.

“You came out of a warm place,” said Waddie, as the stranger seated himself.

“Not very warm,” he replied. “I was in the cabin, and there was no fire down there.”

“But there would have been very soon.”

“No doubt of that. There are two windows in [61] the stern, but, as I cannot swim, I did not like to jump out into the water,” continued the stranger.

“You take it very coolly,” said Tom, with a grin.

“I don’t know that I was afraid of anything. I supposed those other canal-boats were close by, and as soon as I saw or heard any one, I meant to jump into the water, and let him pick me up.”

“Was there no one with you on board?” asked Waddie.

“Yes, a whole family; but they were on deck when the fire broke out, and had only to step on board one of the other boats by her side. I have been travelling a great deal lately, and I was tired and sleepy; so I lay down in a bunk, and went to sleep. When the fire broke out, the men yelled, and that waked me up. I sprang for the stairs, but a sheet of flame lay right over the cabin doors, and I couldn’t go through. So I shut the doors, and went to the windows. I yelled with all my might, to let the boatmen know where I was; but none of them came near me. Then I tried the doors again, and found the fire was blowing off in another direction.”

[62]

“That was after we had swung the canal-boat around,” interposed Waddie.

“I did not know what did it, but when it was safe to do so I went on deck.”

“How did the boat catch afire?” asked Tom.

“I don’t know. There is half a dozen barrels on deck, and they smelled like petroleum. Very likely some smoker dropped his match into the stuff. I heard something which I took to be the bursting of one of the barrels; at any rate, they made a jolly fire. But now I am out of the scrape, I don’t know that I care.”

“It won’t be pleasant for the owner to have his property destroyed,” suggested Waddie; and I think none of us were pleased with the selfish remark of the stranger.

The person whom we had rescued from the burning boat was a young man, not more than twenty-five. He was very well dressed, and I judged from his air and manner that he had seen the world. He interlarded his narrative with much offensive profanity, with which I do not care to soil my pages. On the whole, he did not produce an agreeable impression upon any of us.

[63]

“Have you got that man out of the cabin?” shouted a man in the boat from the steamer.

“Yes, he is safe,” replied Tom. “Why don’t you bring up your steamer, and put the fire out?”

“No use; we couldn’t put it out now.”

“Haven’t you a fire engine on your tow-boat?” I asked.

“No; it is broke down.”

I was inclined to agree with the speaker, who was the captain of the steamer, that it was useless to attempt to extinguish the fire, for the canal-boat was now one mass of flame. She was drifting rapidly towards the shore, and I was afraid she would set the woods on fire, for the bushes hung over the bank, so that the flame would be blown directly into them.

“Will you go on board one of those canal-boats, sir, or shall we put you on shore?” asked Tom, addressing our passenger.

“I don’t know. I have had about enough canal-boat for one day,” he replied, shrugging his shoulders.

“I will do just as you say,” added Tom.

“Is there any hotel around here?” inquired the stranger.

[64]

“Yes, a first-rate hotel, not far from the falls,” added our skipper, pointing in the direction of the spot.

“Then I will go there.”

“All right,” answered Tom, heading the Belle towards the shore.

“My name is Schleifer,” continued the stranger. “I am a drummer for a hardware house in New York.”

This seemed to be a satisfactory explanation to me of the nature of the contents of his travelling-bag, which had rattled like old iron when he threw it upon the deck, and which I found, when I lifted it, was very heavy.

“I got into Hitaca too late to take the boat down the lake, for I expect to sell some goods at the towns below. I had taken all the orders I could get in Hitaca a few days before; so I had nothing to do, and wanted to get to Middleport. I didn’t like the idea of lying around Hitaca till the next morning; so I thought I would try a canal-boat, just for the novelty of the thing.”

“Well, how did you like it?” asked Waddie.

[65]

“I liked it well enough till the fire interfered with the tranquillity of my dreams; but I did not even get singed; so I have no reason to complain.”

By this time the Belle had reached the shore at the point off which she had been moored before. The burning canal-boat had grounded just above us, on a shoal place. As her combustibles on deck had been consumed, the flames were not so fierce, and did not reach the shore.

“I suppose I’m a lucky dog,” said Schleifer, as Tom lowered his sails, having made fast to a tree on shore. “My life is not insured, and it would have been an ugly investment for any office half an hour ago.”

“Thank God for preserving your life,” I added.

“That’s all very well; but I thank my own coolness that I wasn’t fool enough to rush on deck, where the fire would have made an end of me in a minute and a quarter. Do you happen to have any whiskey on board of this craft?”

“Not a drop,” replied Tom, promptly. “We haven’t any use for the article, and we don’t keep it.”

“They keep it at the hotel—don’t they?”

[66]

“I suppose they do. I never called for any,” added Tom.

“Are you the skipper of this craft?” asked Schleifer, in a kind of contemptuous tone.

“I am; and the craft is a good deal better than the skipper.”

“That may be; and, if you don’t take any whiskey, I should say you were half right, at least. I should think, with so much cold water under you and all around you, you would want a little drop of whiskey, just to help keep up an equilibrium, you know.”

“I find that people who take whiskey find it the most difficult to keep up an equilibrium.”

“Every one to his fancy; but I can’t sell goods without a little whiskey. I generally carry a pocket pistol in my bag; but it got smashed against the hardware, the other day, and I’ve been dry ever since.”

“That was because you did not keep up the equilibrium,” laughed Tom. “What kind of hardware do you sell, Mr. Schleifer?”

“Iron, of course.”

[67]

“Pickaxes and crowbars?”

“Not exactly. I couldn’t carry samples in my bag very well. I think I will try to find that hotel now. Did I understand you to say that you were the skipper of this boat?”

“I have that honor; and I wouldn’t swap it off to be governor of the state,” replied Tom.

“Do you keep her to let?”

“That’s what I keep her for.”

“She is a good-looking boat; but I should like her better if she carried a little whiskey on board,” said Schleifer. “Haven’t you just a thimbleful, say forty drops, in the medicine chest?”

“Not the twentieth part of a drop.”

“How long does it take you to run from here down to Cent— down to Middleport?” asked the drummer.

“That depends on the wind.”

“Well, as the wind is to-night.”

“I could fetch it in four hours. The wind would be fair after I got by Priam.”

“Well, skipper, seeing it’s you, I will give you a five-dollar bill if you will land me in Centre— I mean in Middleport.”

[68]

“Well, seeing it’s you, Mr. Schleifer, I won’t do it.”

“Not for five dollars?”

“No, nor for ten. My boat is engaged to these gentlemen for the rest of the week.”

“We will let you off, Tom,” whispered Waddie.

“I don’t want to be let off.”

“I have an invitation from Captain Portman for Waddie and myself to sleep at his house,” I added.

“Is that so? Then I will take him down to Centreport for ten dollars.”

“Middleport,” said Schleifer. “I will give you five.”

“No; nothing short of ten for a night run down the lake. I like to sleep a little once in a while.”

After some bickering the drummer agreed to give ten dollars for his passage; but he insisted upon going to the hotel first for a “drop of whiskey.”

[69]

“I couldn’t go to sleep to-night without a drop of whiskey, and I must have some,” said Schleifer. “It won’t take me long to go to the hotel.”

“Do you know the way?” inquired Waddie.

“No; but I can find it.”

“We are going up that way. We will show you the road.”

“I don’t need any help. I can snuff a place where they sell whiskey two miles off,” replied the commercial gentleman, coarsely.

He went on shore, taking his bag with him, and made his way up to the road which led to the hotel. Waddie and I walked up to Captain Portman’s house; but he was not at home, though the servant said he would return soon. He had probably [70] gone over to the hotel, which he generally visited in the evening. We did not care to remain if Captain Portman was not at home, and we walked towards the hotel, expecting to meet him there.

“Why didn’t that fellow go to Middleport in the tow-boat, if he wanted to go there?” said Waddie, who had taken a strong dislike to Tom’s passenger.

“I suppose he was afraid of being blown up, or burned up,” I replied.

“He did not even take the trouble to thank us for saving him from the flames.”

“Probably he does not think we saved him from anything but a wet jacket,” I suggested.

“Even that is worth acknowledging.”

“These drummers live on brass, and this fellow is in the hardware line.”

“Waddie! Is that you?” called Tom Walton, as he rushed up to us when we came down the hill from Captain Portman’s mansion.

“Yes, it is I. What’s the matter, Tom?” asked Waddie.

“A young woman just came down to the boat, [71] and said she wanted to see you very bad,” replied Tom, with no little excitement in his manner.

“A young woman! Who is she?”

“I haven’t the least idea; but she has a nobby look, as I made her out in the dark. She wanted you so bad that I told her I would try and find you.”

“Who can it be?” said Waddie.

“Probably Miss Dornwood,” I suggested.

“But she would not be out of the hotel at this hour in the evening.”

“Her relations with her guardian were not very pleasant, you know,” I added.

“Well, we will go down and see her, at any rate;” and we walked towards the moorings of the Belle.

“Waddie, you must be very careful,” said I, not at all pleased with the complications which seemed to be before us.

“Careful? What do you mean, Wolf?”

“If I am not mistaken, the question which we attempted to dodge once before this evening will come up again.”

[72]

“What’s that?”

“When Mr.— What’s his name?”

“Mr. Overton,” added Waddie, supplying the name I had forgotten.

“When Mr. Overton attempted to compel Miss Dornwood to return to the hotel, you stepped between him and her. If the bear had not made a scene just at that moment, there might have been a quarrel between you and the guardian.”

“You are too cautious, Wolf. I wouldn’t stand by and see him abuse the young lady. Why, Captain Portman said he should interfere, and take the responsibility,” protested Waddie.

“I would interfere if there were any real abuse, Waddie; but I think it is better to wait for a pretty strong provocation before you meddle with family affairs.”

“I will be as careful as I can, Wolf; but when I see a young lady persecuted by a cruel guardian, it isn’t exactly my style to take it coolly.”

“We don’t know anything about the facts yet, and you must remember that there are two sides to every story.”

[73]

“I will try to remember it. But I don’t see what she wants with me.”

“Very likely she has had some trouble with her guardian, and wants your assistance.”

“If I can assist her, I shall certainly do so. I think that Overton is a brute, whatever his relations to the lady may be.”

By this time we were near the boat, and I repeated, in a low tone, my caution to Waddie. I saw that he was very much interested in the young lady, and, aware of his impetuous character, I was afraid he would be too forward in rendering assistance to her. Miss Dornwood stood upon the shore near the boat. As we approached her, I saw that she was very much agitated, and I regarded this as altogether in her favor.

“Good evening, Miss Dornwood,” said Waddie.

“I do not know what you will think of me,” she replied, in trembling tones. “I am very much alarmed.”

“What is the matter?” asked Waddie, in a tone which was calculated to assure her.

“I wished to see you very much, for you were so kind to me that I was sure you would assist me.”

[74]

“I should be very glad to assist you, if it is in my power to do so.”

“You said you had a boat. I suppose this is the one.”

“It is not mine, though we came up the lake to-day in her.”

“Do you know where the town of Ruoara is?” asked the young lady, as she glanced around her in terror.

“I do, very well indeed. It is only eight miles from my home,” replied Waddie.

“I wish to go there very much,” continued she, earnestly.

“To-night?”

“Yes, to-night—immediately.”

“That’s very unfortunate, for the skipper has to take a gentleman to Middleport,” replied Waddie.

“O, dear! What shall I do?” exclaimed the young lady. “I must go at once.”

“Perhaps you can go in the boat with the gentleman as far as Middleport, and—”

“Who is the gentleman?” interposed she, anxiously.

[75]

“I don’t know him. He is a commercial agent.”

“I cannot go with a stranger,” said she, shaking her head in a very positive manner.

“Am I not a stranger?”

“No; I learned, after we parted this afternoon, that you were the son of a very influential gentleman, and you were kind enough to step between me and my guardian, when he intended to lay his hands upon me.”

“Who told you this?”

“The landlord. He said your friend was Captain Penniman; and I was sure, after the service you had rendered me, that you would again be my friend, and help me to get to Ruoara.”

“Won’t you sit down in the boat?” added Waddie, stepping on board of the Belle.

“No, I thank you. I do not wish to meet any strangers,” replied Miss Dornwood. “I know you think I am very bold; but I should not have come to you if I had not known who you were.”

“If you will not go with the gentleman, I do not see what I can do for you. There is no other sail-boat here.”

[76]

“I suppose I must return to my prison,” said she, bursting into tears.

“Do not weep,” interposed Waddie, moved by her grief.

“Mr. Wimpleton, I envy the poor man’s daughter who is surrounded by good and true friends,” sobbed she. “I will go back to my prison.”

“What do you mean by your prison?” inquired Waddie.

“My guardian sent me to my room, and then locked me in it. I cannot endure such indignities. I am going to leave him. I am going to work for my daily bread in a factory, in a shop—anywhere that I can earn enough to support me.”

“Is your situation so desperate as this?”

“It is, indeed! If I had no spirit at all, perhaps I could endure it.”

“There comes some one,” interposed Tom Walton, who had walked up to the road, as soon as he understood the case, in order to warn us of the approach of his passenger.

Without another word, Miss Dornwood fled like a frightened fawn in the direction opposite that in [77] which Schleifer was approaching. Waddie, deeply interested in her case, followed her, intent upon assisting her to the extent of his ability.

“There is some one with him,” said Tom, as I joined him, half way between the lake and the road.

“Perhaps you are to have two passengers,” I suggested.

The drummer and the person who was with him halted in the road, and seemed to be engaged in a very earnest conversation. We could not hear a word they said, but it was evident that they had not met for the first time, and that they were not talking about the sale of hardware. It was too dark to see any more than the form of Schleifer’s friend.

“You wait here,” said he, after the conversation had continued a few moments.

“Hurry up,” replied the other person, whose voice seemed to be familiar to me, though I could not identify it.

As the drummer approached, we retreated towards the boat.

[78]

“Hallo, there, skipper!” shouted he.

“Are you ready?” asked Tom, as we stopped, and waited till he came up.

“If it’s all the same to you, I won’t go down the lake to-night. I met a friend of mine at the hotel, and I want to stay with him till to-morrow.”

“All right,” answered Tom.

“A trade’s a trade. I agreed to give you ten dollars for the trip. If you will call it five, and not go, I shall be satisfied,” added Schleifer.

“I don’t want any five, if you don’t go,” replied Tom. “I only want what I earn.”

“But I am willing to compromise.”

“I don’t compromise. We will call it square as it is. If you are satisfied, I am.”

“Well, I shall want your boat another time, and I’ll make it right with you then,” added the drummer, as he turned to leave.

“It’s all right now.”

“That’s lucky for Waddie,” I suggested.

“It works first rate. Now, if Waddie wants to take the lady to Ruoara, the boat is all ready.”

“But where is he?”

[79]

“They haven’t got a great way yet.”

“Probably she will go towards the hotel. You follow them, Tom, and I will go up this way,” I replied, moving in the direction which Schleifer had taken.

I soon discovered the drummer and his friend walking rapidly towards the hotel. I was a little curious to know who the person was whose voice had sounded so familiar to me, and I quickened my pace, hoping the lights in front of the hotel would enable me to obtain a clear view of him. I followed them closely; but before reaching the hotel they turned in at a road which led to the stable in the rear. Before I could come up with them, they had seated themselves in a light wagon, which must have been ordered before, and drove off.

“Who are those gentlemen?” I asked of the stable-keeper, who stood in the yard with a lantern in his hand.

“One of them I never saw till now; the other is stopping at the hotel, and is a big gun,” he replied.

“I know the taller one. Who is the other?”

[80]

“He’s the big gun. He came this morning; but no one found out what he was till after dinner.”

“What is he?”

“He’s the big gun. He’s an English lord. I forget what they call him.”

“Lord Palsgrave,” I suggested.

“That’s the name. He’s a nobby fellow, and spreads his dollars with a looseness.”

“Where is he going now?”

“To Priam, I reckon. He said he should not be back till to-morrow morning; and there is to be a big dance there to-night. But I wonder he didn’t take the young lady with him, who came with his party.”

I walked round the hotel, in order to intercept Waddie and Miss Dornwood; but I saw nothing of them, and I concluded that Tom had already overtaken them. After the information I had obtained from the stable-keeper, my idea of an English lord was considerably modified. He was on good terms with a hardware drummer, which did not seem to be exactly consistent with his exalted position. But [81] it was possible that the drummer was a baron or a marquis in disguise, though the clatter of his hardware samples did not tend to prove it.

I continued my walk towards the lake, and presently met Waddie and Miss Dornwood.

[82]

As soon as I saw and recognized Waddie and Miss Dornwood, they turned out of the road with the evident intention of avoiding me.

“Waddie!” I called to him.

Hearing my voice, they returned to the road, assured that I was not the brutal guardian whom the young lady had so much reason to shun.

“Haven’t you seen Tom?” I asked.

“No.”

“He is looking for you.”

“We heard some one behind us, and turned aside till he had passed,” added Waddie. “What does he want?”

“The drummer has concluded not to go to Middleport to-night.”

“And can you have the boat?” inquired Miss Dornwood, eagerly.

[83]

“The boat is certainly available,” I replied. “But do you really wish to make a trip of thirty miles on the lake in the night?”

“I am afraid of nothing but the tyranny of my guardian,” she responded, promptly.

“Where is Tom?” inquired Waddie. “We will lose no time.”

“I will find him. If he passed you, he must be near the hotel.”

They walked towards the boat, and I returned to the hotel, where I found Tom, and we soon joined Waddie on board of the Belle. We were all ready to start; but I confess I was very much troubled about the circumstances of the voyage. The mainsail was flapping in the fresh breeze; but I was somewhat afraid that Waddie was getting himself, and perhaps me, into a scrape.

“Are you going, Waddie?” I asked, in introducing what I wished to say.

“Certainly I am.”

“I hope you will go with me. I should not feel safe without you,” added Miss Dornwood.

“Won’t you go too, Wolf?” asked Waddie.

[84]

“I should be glad to have you,” continued the young lady.

“I am not perfectly clear in regard to this matter,” I suggested.

“Pray do not stay here any longer,” interposed Miss Dornwood. “If my guardian should discover my absence, I’m afraid he would come down here to look for me. Please to go out upon the lake, and I will tell you all my story. Then, if you will not assist me, we can return.”

“Shove off, Tom,” I replied.

The skipper ran up the jib, and the Belle, gathering headway, stood out into the lake.

“I think you are very cautious, Captain Penniman,” said Miss Dornwood.

“I am sure my friend here does not wish to do anything wrong,” I added.

“I will bear all the blame,” said Waddie, warmly. “I think I can find friends for Miss Dornwood without going so far as Ruoara.”

“Where?” I asked, curiously.

“At my father’s house.”

“I shall not be obliged to trespass upon the kindness [85] of your father’s family, Mr. Wimpleton,” added Miss Dornwood. “My friends in Ruoara will not hesitate to receive me into their house, though they know all the circumstances of my situation.”

“Who are they?” I asked.

“Mr. Pinkerton and his family. Do you know them?”

“Very well indeed. Ben Pinkerton’s father,” added Waddie.

The Pinkertons were of the highest social standing in Ruoara, and I was almost willing to believe that there could be no harm in conveying the young lady to such friends as they were.

“Emily Pinkerton was my schoolmate at the academy, and before my father died, our two families became quite intimate,” continued Miss Dornwood. “Emily was at my guardian’s house last spring with her father and mother, and they know all about the circumstances.”

“Do they think it is proper for you to leave your guardian?”

“Mr. Pinkerton told me himself to come to his house whenever I could not endure my guardian [86] any longer. I should have gone there before if I could have got away.”

“Are your father and mother both dead?” I inquired.

“Both of them. I am going to tell you the whole history of our family. I am seventeen now, and Mr. Pinkerton says I am old enough to think for myself. I believe I am.”

“I should say you were,” I replied.

“My mother was married twice,” Miss Dornwood began. “Her first husband’s name was Richard Overton, and they had one son, Charles Overton, who is now my guardian. His father died when he was only four years old. Two years after his death, my mother was married again, to Edward Dornwood, my father. He was a wealthy man; but he was deformed, and in very poor health. I wish I could tell you how much I loved him, and how devoted he was to me. Even the great hump upon his back was not a deformity in my eyes. But, feeble as he was, my mother was the first to pass away, and died when I was only eight. I hardly remember her. I have no doubt she loved me as a mother should [87] love a child; but I know she used to scold me very severely, and I recollect this more clearly than anything else.

“My father never spoke an unkind word to me. When I did wrong, when I fretted, he looked so sad,—sometimes actually shedding tears,—that it became a positive terror to me to displease him. When he became so feeble that he could not leave the house, I spent all my time out of school with him. His eyes failed so that he could not see well, and, for hours together, I used to read books to him which had not the least interest to me. I can truly say, that I was never so happy as when with him.”

“Where was this Charles Overton all this time?” I asked, as she paused to wipe away her tears.

“He lived near us, and professed a very deep interest in my poor dear father, and in me too, for that matter. His father had died a poor man, and he was a clerk in a store. He used to come in every day, and express so much solicitude for my father and his affairs, that we were all deceived in him. We thought he was a good man, but really [88] all he cared for was my father’s money. By degrees he won his confidence; and, though he had never treated me as a sister when we were children together, I was very grateful to him for the care he bestowed upon his step-father.