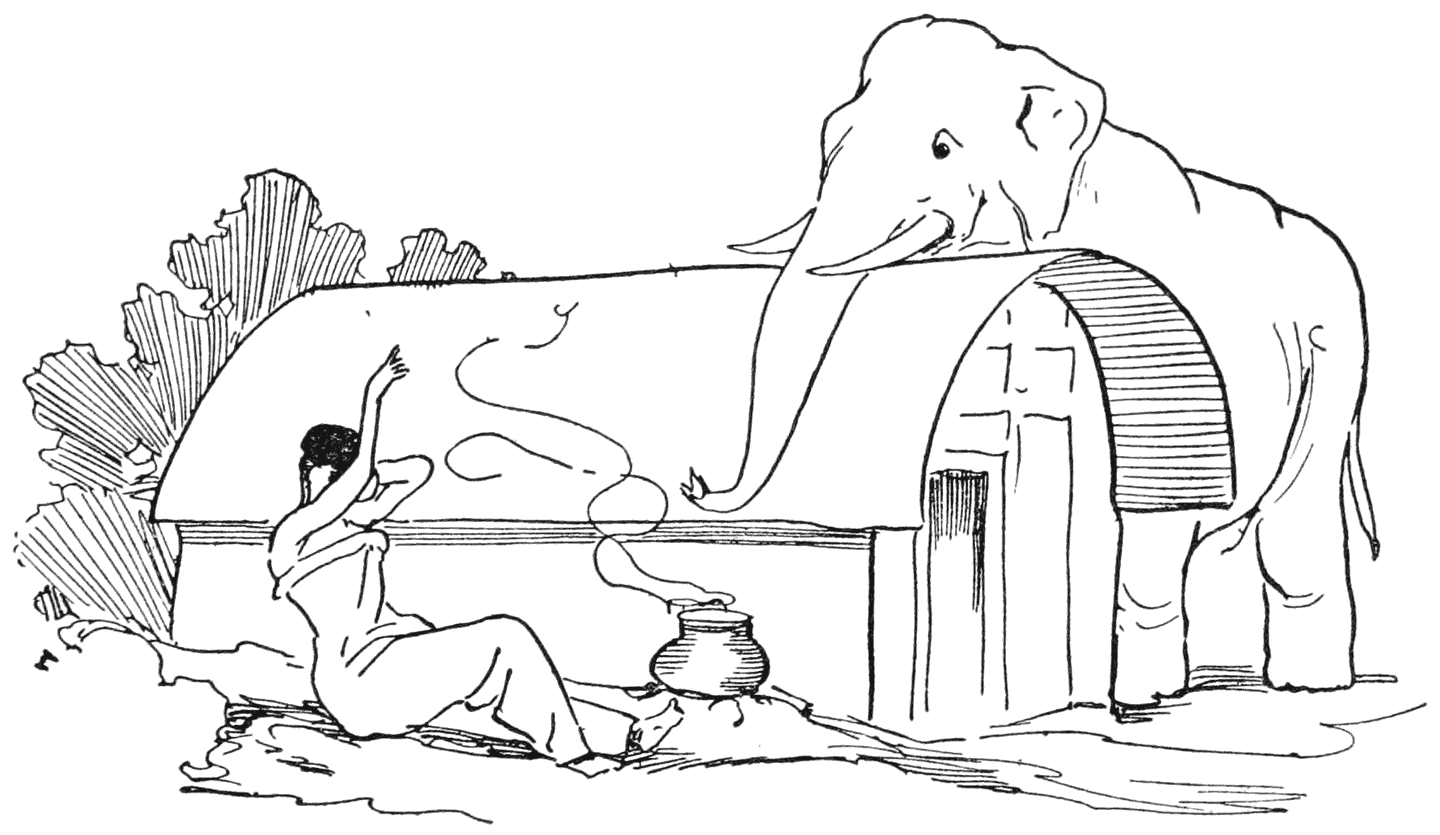

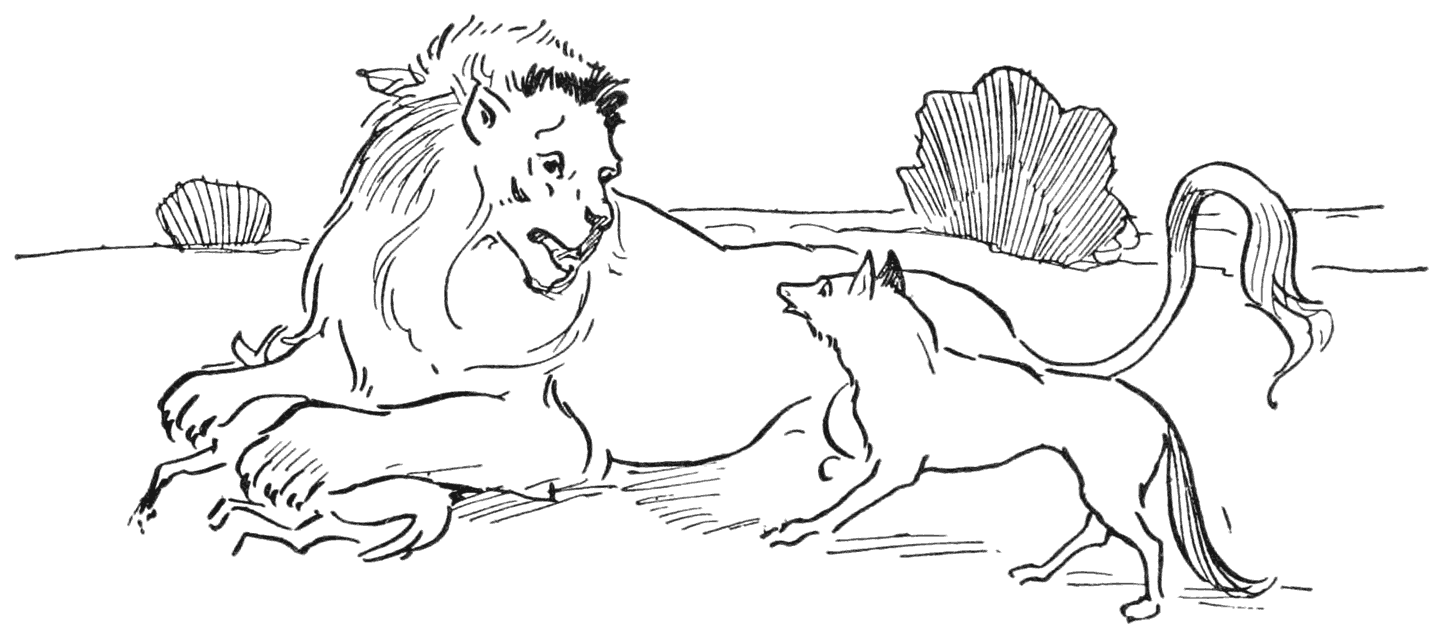

arle was a very pretty girl who lived with her father and mother and two brothers

in a hut by the side of an African river.

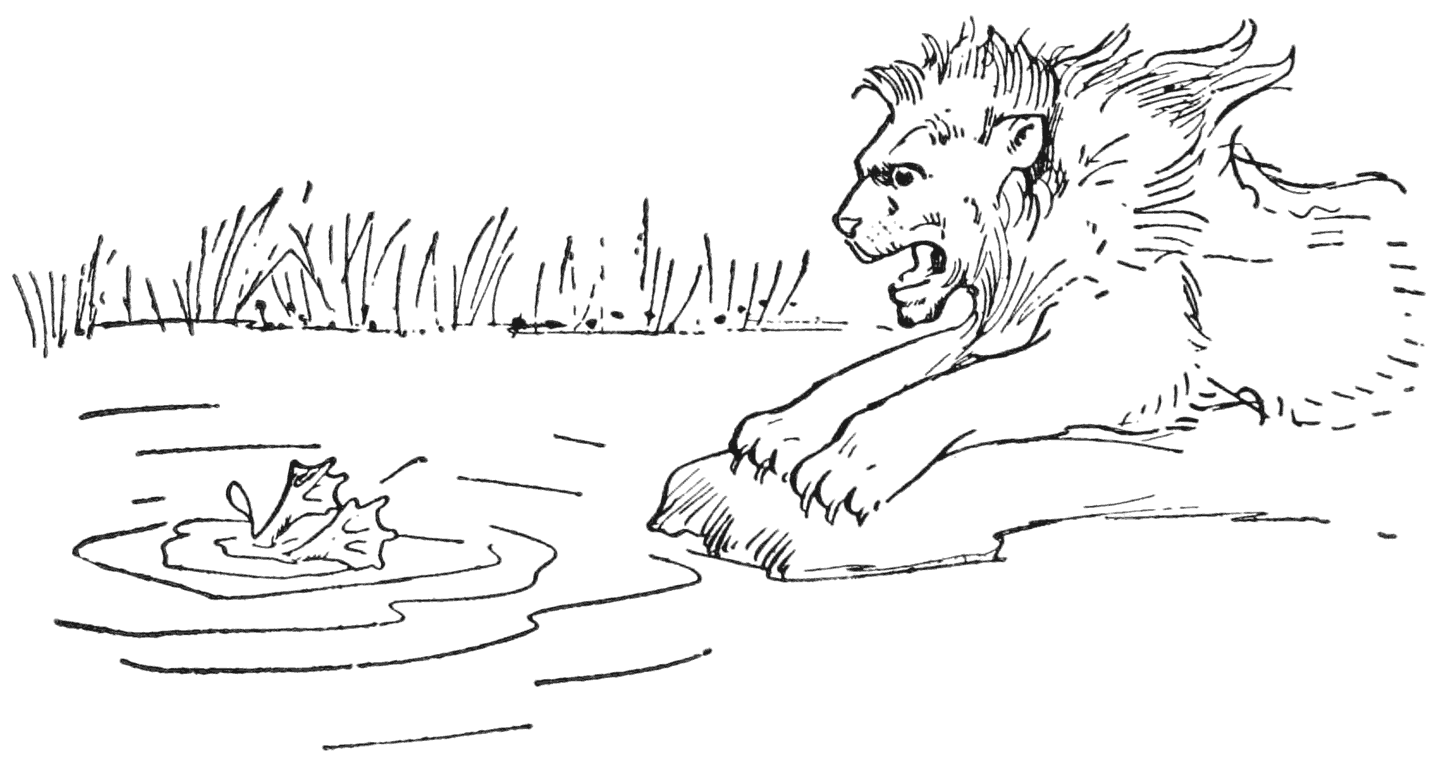

It was not a pleasant river at all, for it was brown in color, and flowed through

a dark and gloomy forest of great trees and closely woven vines. There were crocodiles,

[14]too, in the ugly black river, and Parle was afraid to bathe in it.

Although one would hardly believe it, Parle grew up very happily in this little clearing

by the river, and never had a real grief until her two brothers left home to go hunting,

and would not take her with them.

“You will see the moon rise and set many times before we come back,” they said, “but

when we come, we will find you a good husband, and we will dance merrily at your wedding.”

“Let me go with you, and hunt the elephant,” she pleaded. “I don’t want a husband;

I want to go with you.”

“The cooking-pot is better than the spear for girls,” said the older brother decidedly,

“and you must stay at home.”

“But I want to go so much,” still pleaded the girl, “for you may find the great river

Ramil has told us about so often.”

“What river is that?” they asked.

“Why Ramil says the first men who were [15]ever made, lived by the side of a great river—up there,” she answered, pointing vaguely

towards the north.

“She says the men were all black; but some of them swam across to the other side,

and the water washed them white. Since then the white men are always stretching out

their hands and calling to the blacks to come across to them.”

[16]

“Oh, that Ramil is full of silly stories,” said the older brother. “I don’t believe

them.”

“But the white men do come from over there,” persisted Parle, gazing northward as

if she could see the river in the distance. “I should like to swim across and be washed

white, too!”

The younger brother thought this the most foolish speech he had ever heard. “Well,”

he said, “there is no accounting for some people’s tastes!”

Then the brothers rubbed their spears with some kind of grease which they believed

would kill elephants, and as they did so they sang:

“When mine enemy thou shalt see,

Black and tall like an ebony-tree,

Sing softly, softly, little spear,

As to his heart thou drawest near.”

Early the next morning the two brothers started on the expedition, leaving their sister

behind. In her loneliness, she visited the witch-doctress, Ramil, oftener than she

had ever done before, and led her [17]on to talk of the river far away beyond the forest, and the white men on the other

side of it.

“The best thing for you to do,” said Ramil, “that is, if you really want to go there,

is to marry my son. Then he can carry you on his back through the forest.”

“I should be too heavy,” said Parle, shaking her pretty head; “and besides, I don’t

want to marry anyone.”

“You could not be too heavy for my son,” replied the witch. “His legs are as thick

as tree-trunks, and he stands twelve feet high at least.

“As for not wanting a husband,” continued Ramil; “that is what all girls say, but

they don’t mean it.”

“I wouldn’t want to marry a giant,” said Parle.

“Oh, he isn’t a giant. He is—but never mind—wait till you see him,” replied Ramil

mysteriously, for she was determined to marry Parle to her son, if possible.

So that evening, when the moon was shining softly through the trees, she stole away

to the place [18]where her son was usually to be found at night, and by and by she came across him

at the edge of a swamp, where he had been rolling about in the muddy water.

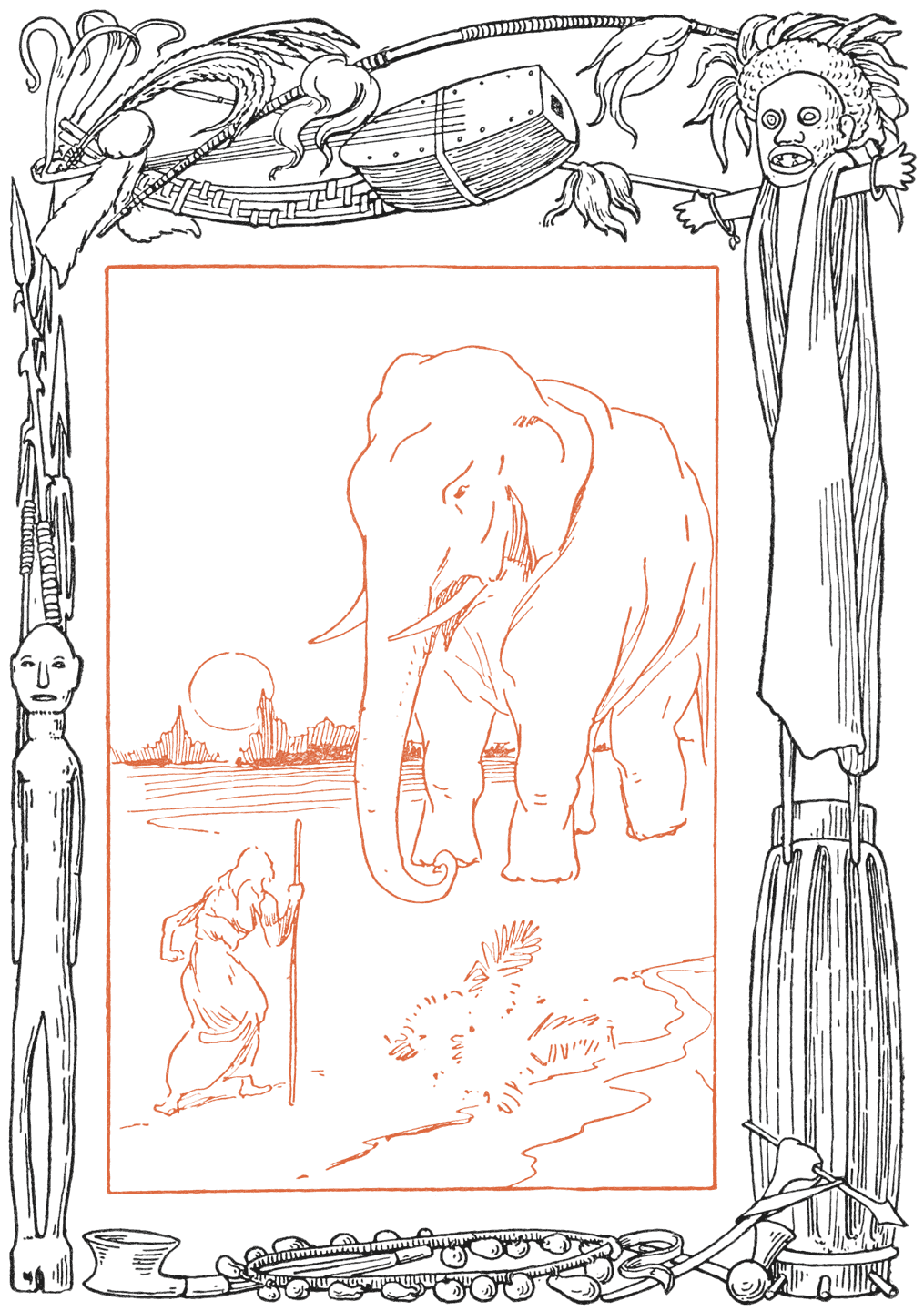

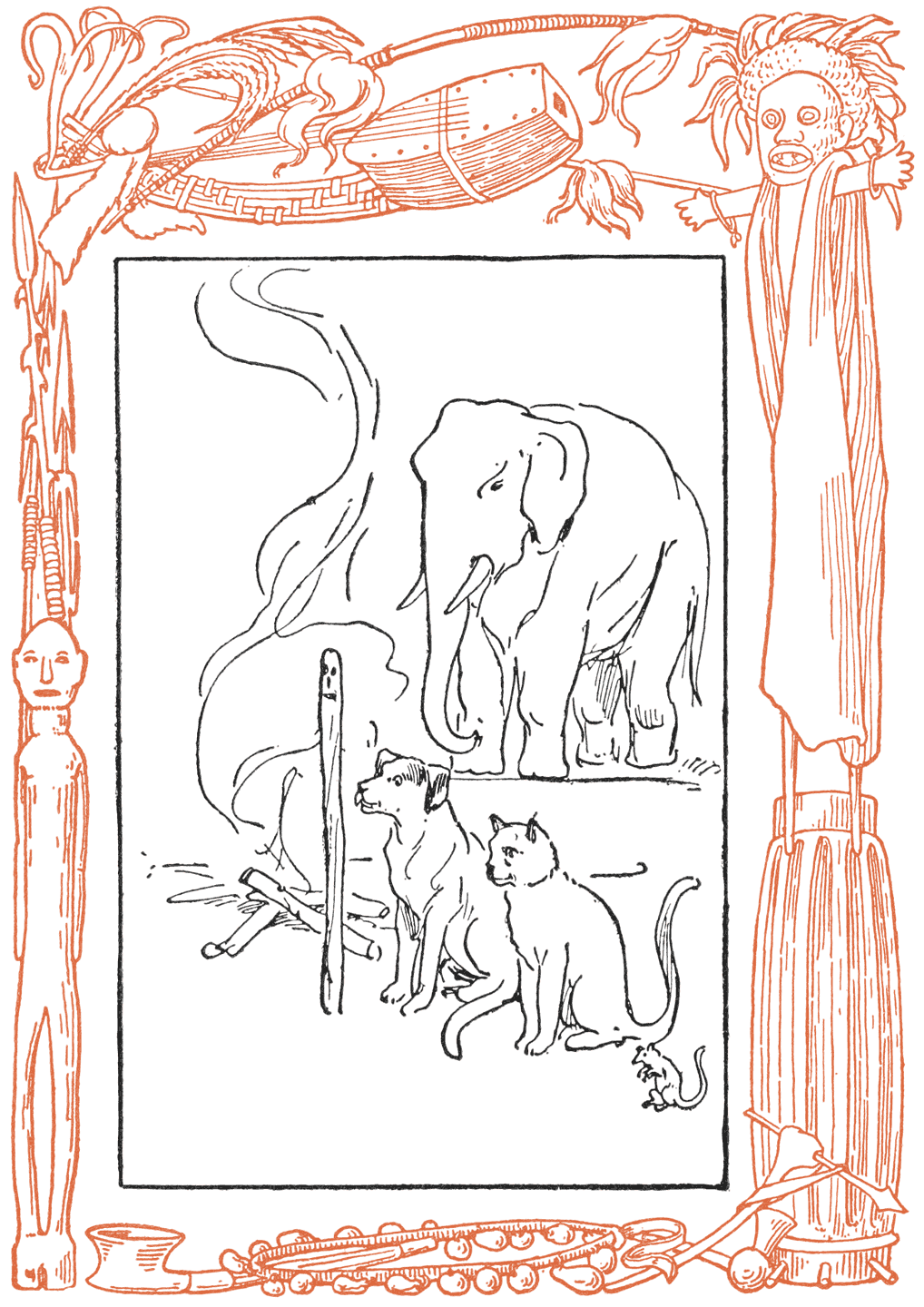

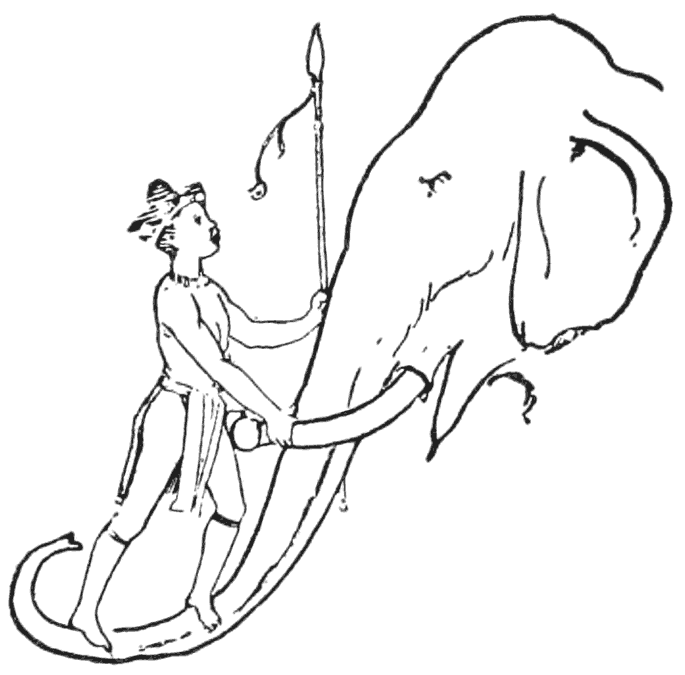

He was twelve feet high, and had legs like tree-trunks, as she had said; for Ramil’s

son was nothing more nor less than a big black elephant, and that very day he had

nearly been killed by Parle’s brothers.

“What do you want of me now, little mother?” he asked, rubbing himself gently against

a tree.

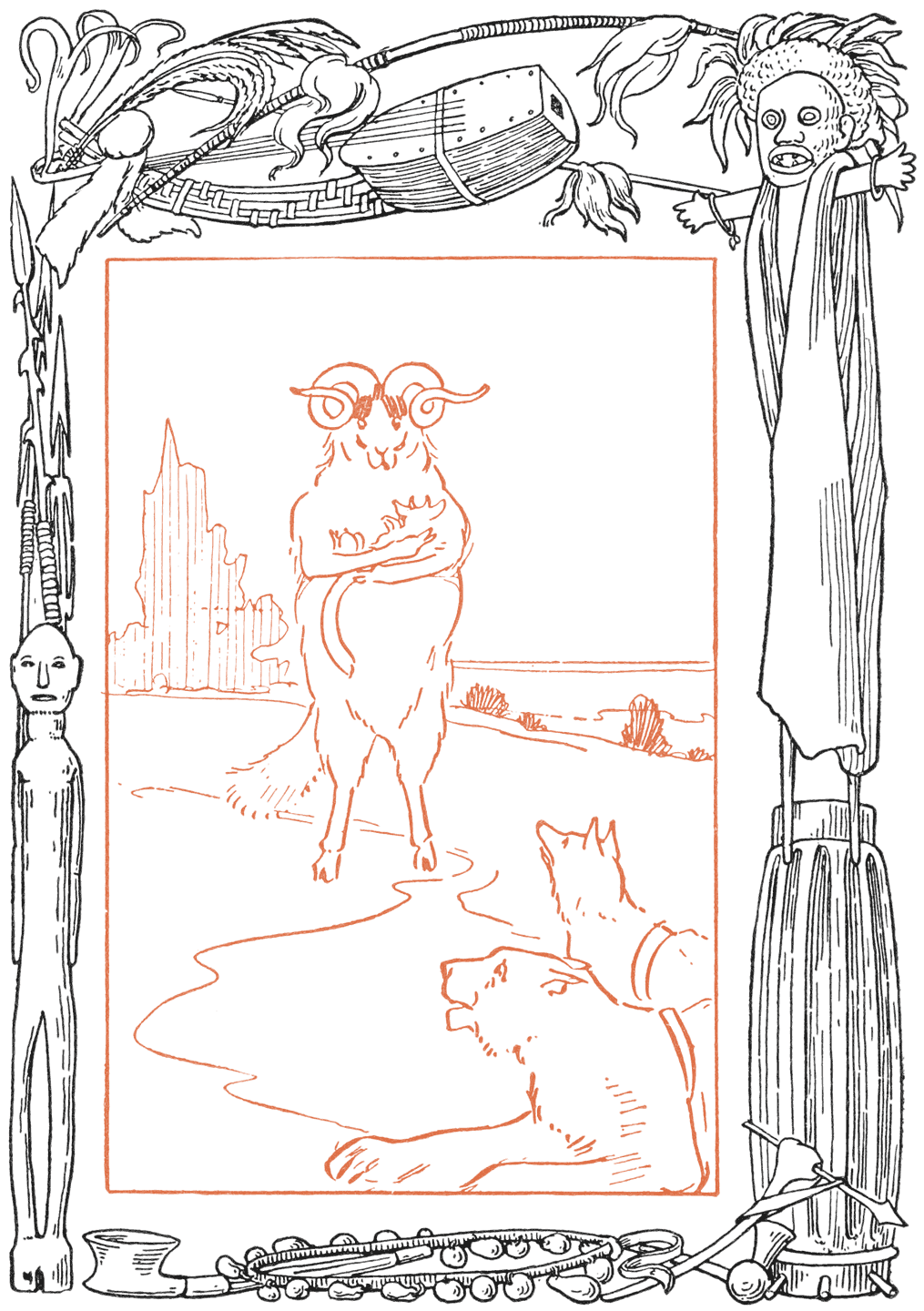

“It is time you had a wife,” she replied. “I have found the prettiest little wife

for you, but she will never consent to marry an elephant. You will have to let me

turn you into a bushman for a little while.”

“How will you do it? and why is it necessary?” asked her son suspiciously. You see,

he knew his mother was a witch.

“If you eat one of these,” replied his mother, showing him some leaves she had picked

on her way through the forest, “you will become a handsome [21]young bushman, who can woo the girl and marry her.

[19]

[21]

“Then when you have carried off your bride, you can eat another leaf, and then you

will be changed into an elephant again.”

“Can she cook fish and make cakes?” asked the elephant; “and is she really a pretty

girl, my mother?”

“Indeed she is pretty,” said Ramil, noticing that her son’s eyes twinkled. “She is

as sweet as the wild mango blossoms when they fall to the ground in the spring.

“And as to her cooking,” she went on; “I have tasted her baked fish and her broth.”

And Ramil rolled her eyes, remembering how good they had been, and pleased to see

a look of satisfaction stealing over her son’s face.

“I do get so tired of plantain leaves,” said the elephant plaintively.

“No wonder. That’s because your mother wasn’t an elephant. Well, she will need a big

[22]cooking-pot! One baked fish will never satisfy you.”

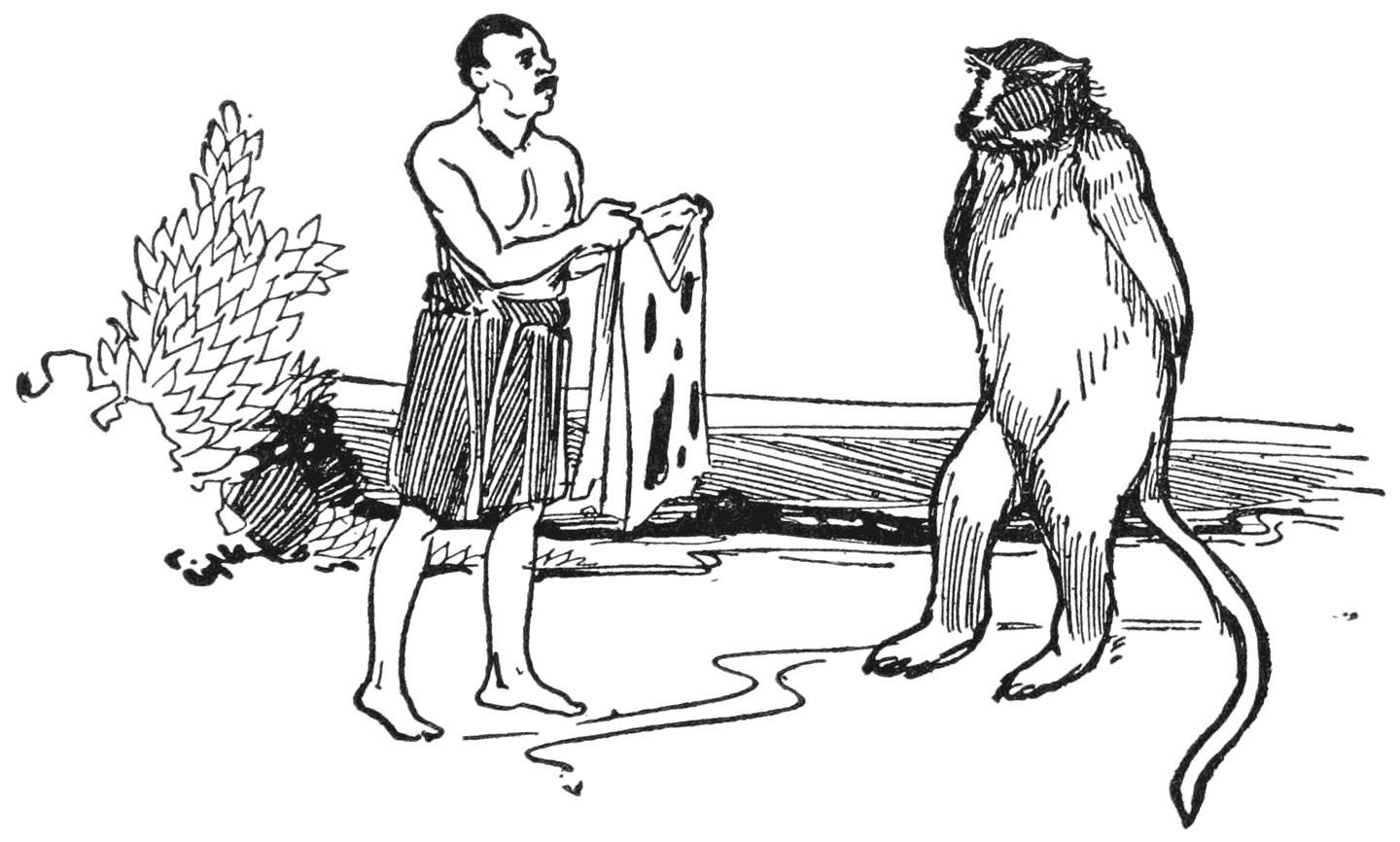

So Ramil persuaded her son to eat one of the leaves, and as soon as he had done it

his four legs became two, and his clumsy body changed into that of a tall, well-made

young bushman.

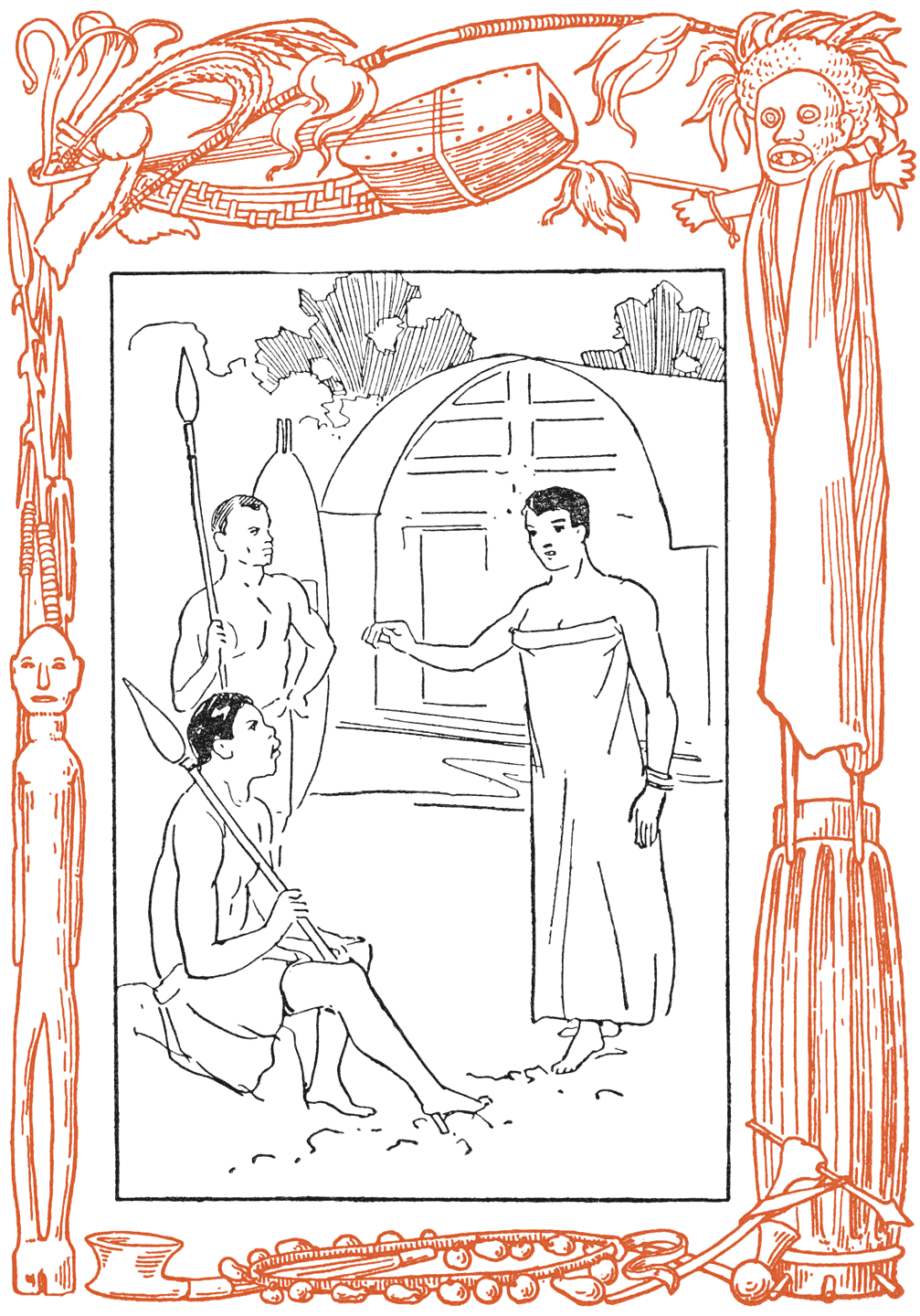

Then he took a spear in his hand and went with his mother to the door of Parle’s hut,

who thought he was the handsomest young man she had ever seen.

“But you said he was twelve feet high, and that his legs were like tree-trunks,” she

cried.

And the cunning old woman answered, “That was because he was under a spell. He is

cured now.” So Parle promised to be his wife, and after they were married he took

her away with him into the forest.

But they did not travel north as he had promised, towards the great river which washed

black people white. Instead, they went south, always south, towards the plains where

the elephant hunters were [23]few, and where her husband thought he might live in peace with his wife.

By and by they came to a beautiful country covered with green grass and flowers, for

it was early spring, and there he built her a hut. “Now I will go fishing,” he said,

“and you shall cook my supper when I come back.”

When he came back, he brought with him thirty fish; and when Parle saw them, she said,

“three would have been enough.”

[24]

“I want them all cooked,” replied her husband. “Thirty will not be too many.”

“But see how large they are!” insisted his wife.

“That makes no difference. Do as I tell you!” he answered sternly.

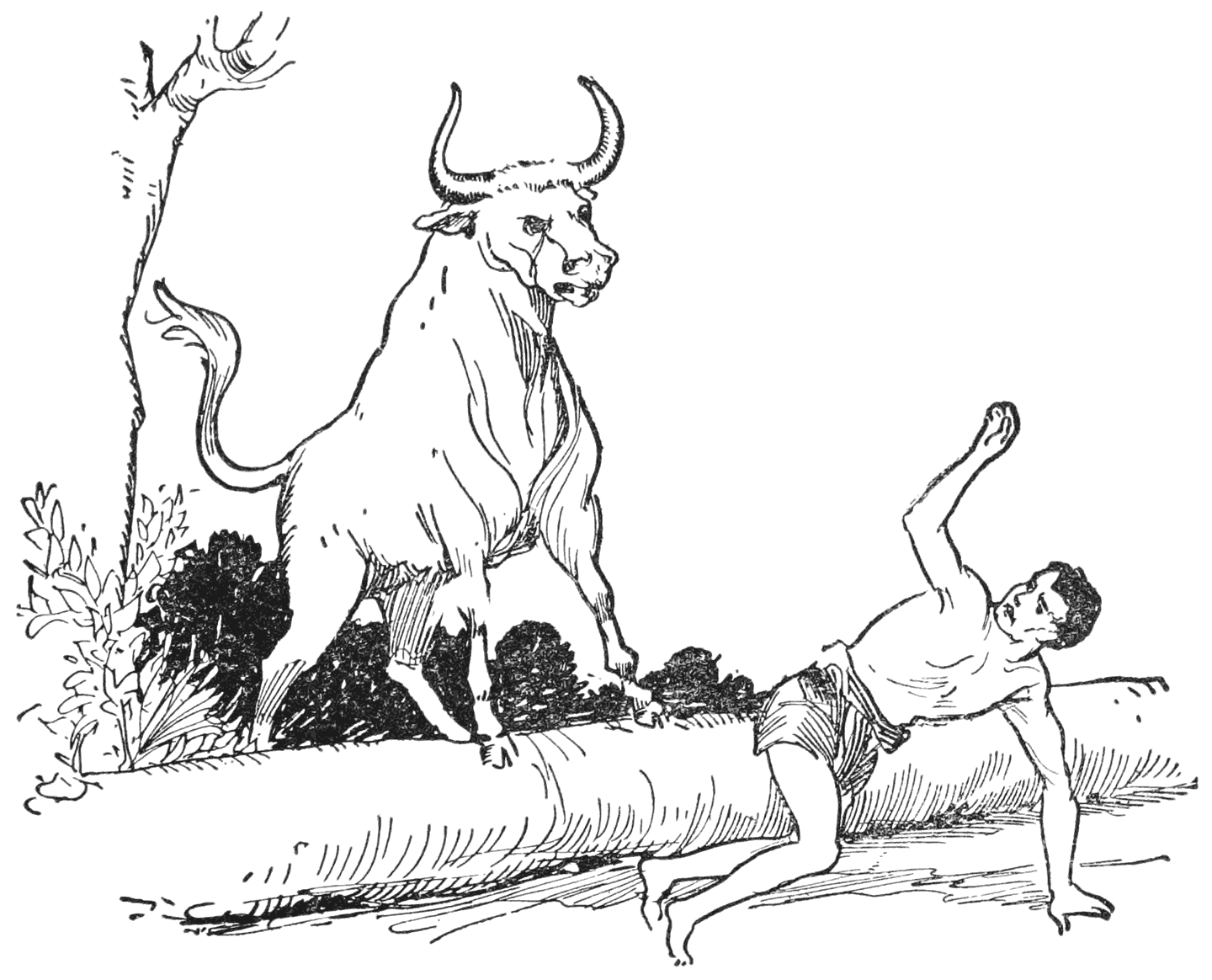

So Parle began to cook them, while her husband went behind the hut and ate the second

leaf his mother had given him.

And as soon as he had done this, his nose grew into a trunk and his teeth into tusks,

while his body changed into that of a huge elephant, standing four feet above the

roof!

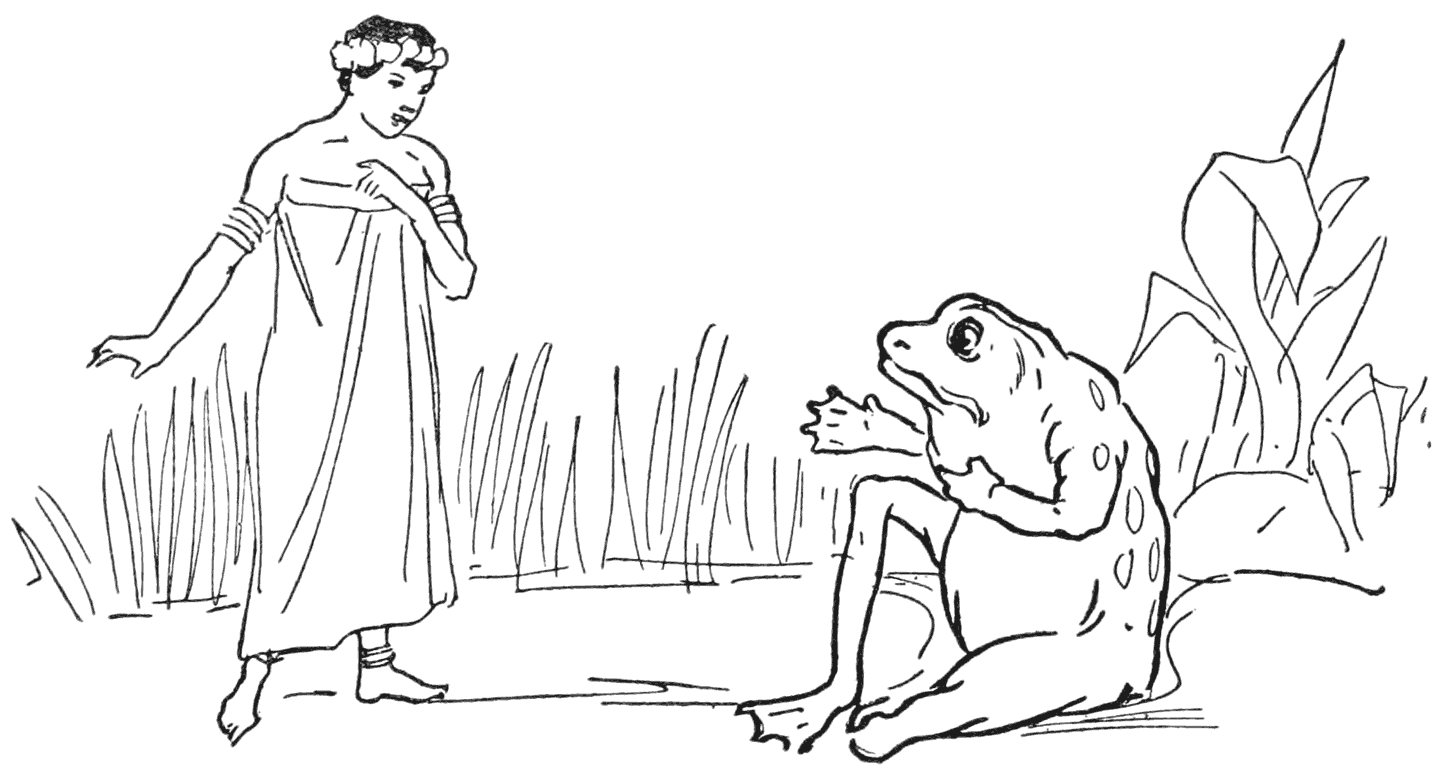

Parle looked up from her cooking and gave a scream. “Oh, Lomi! Lomi!” she called out.

“Save me from the elephant!”

“I am Lomi, your husband,” he replied, talking to her across the roof of the hut.

“Don’t be frightened.”

“But I am frightened!” cried the poor girl, crouching on the ground and holding her

face in her hands, while her husband told her the story of the trick he had played

on her.

[25]

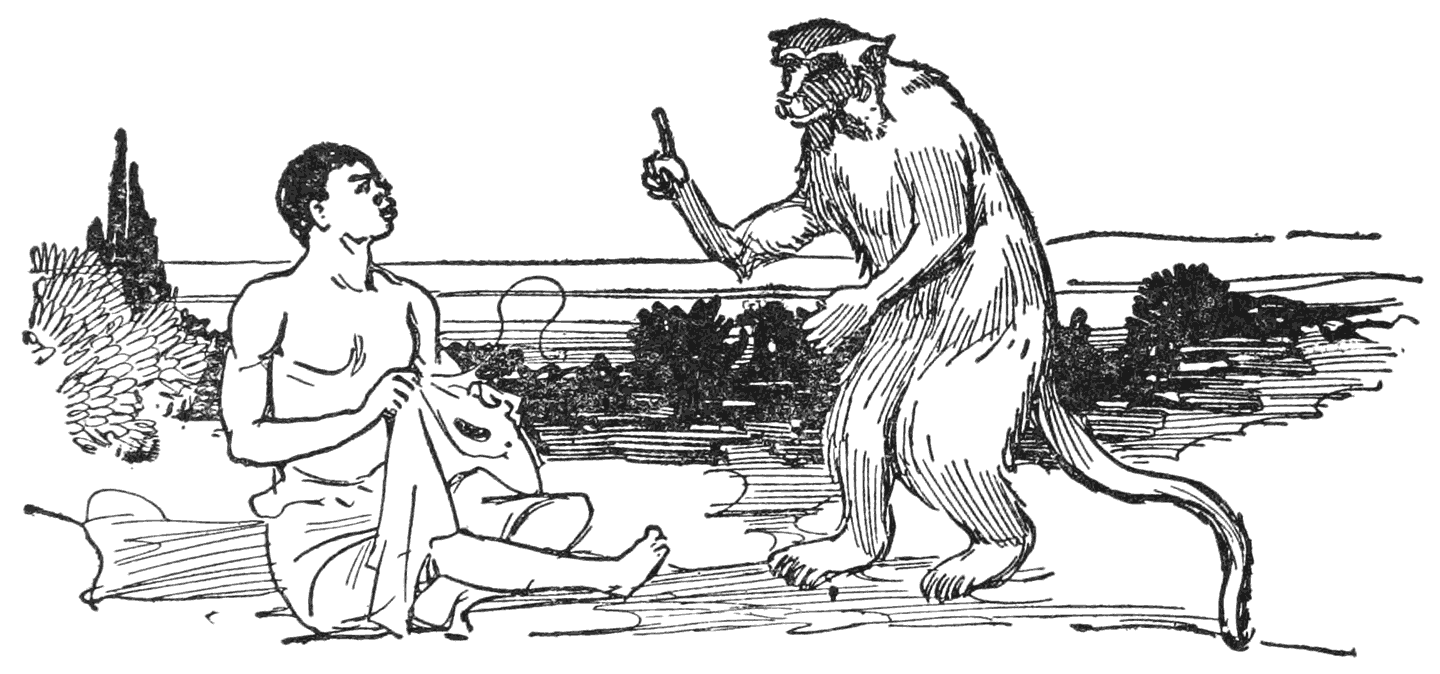

“Now all you have to do is to please me,” he went on, “or it will be the worse for

you.

“I am tired of elephant food, and want broth, baked meat, plenty of fish, and all

the good things bushmen eat. I will go and hunt for them, and it will be your business

to see that they are properly cooked.”

So poor Parle had to cook from morning until night to satisfy her husband’s appetite.

He brought home springbok and gemsbok—small deer [26]which roamed about the plains—and she made broths and stews of them, as her mother

had taught her.

How she did have to work! Instead of running out in the morning to gather flowers,

she had to go fishing, or to collect eggs to put into the soups. She grew so ill and

thin that none would have known her for the same pretty girl who had left home with

the young bushman.

[27]

But every day, when she came out of her hut, she shaded her eyes from the sun, and

looked across the plain to see if there were any travelers coming from the north.

“Some day my brothers may find me,” she thought.

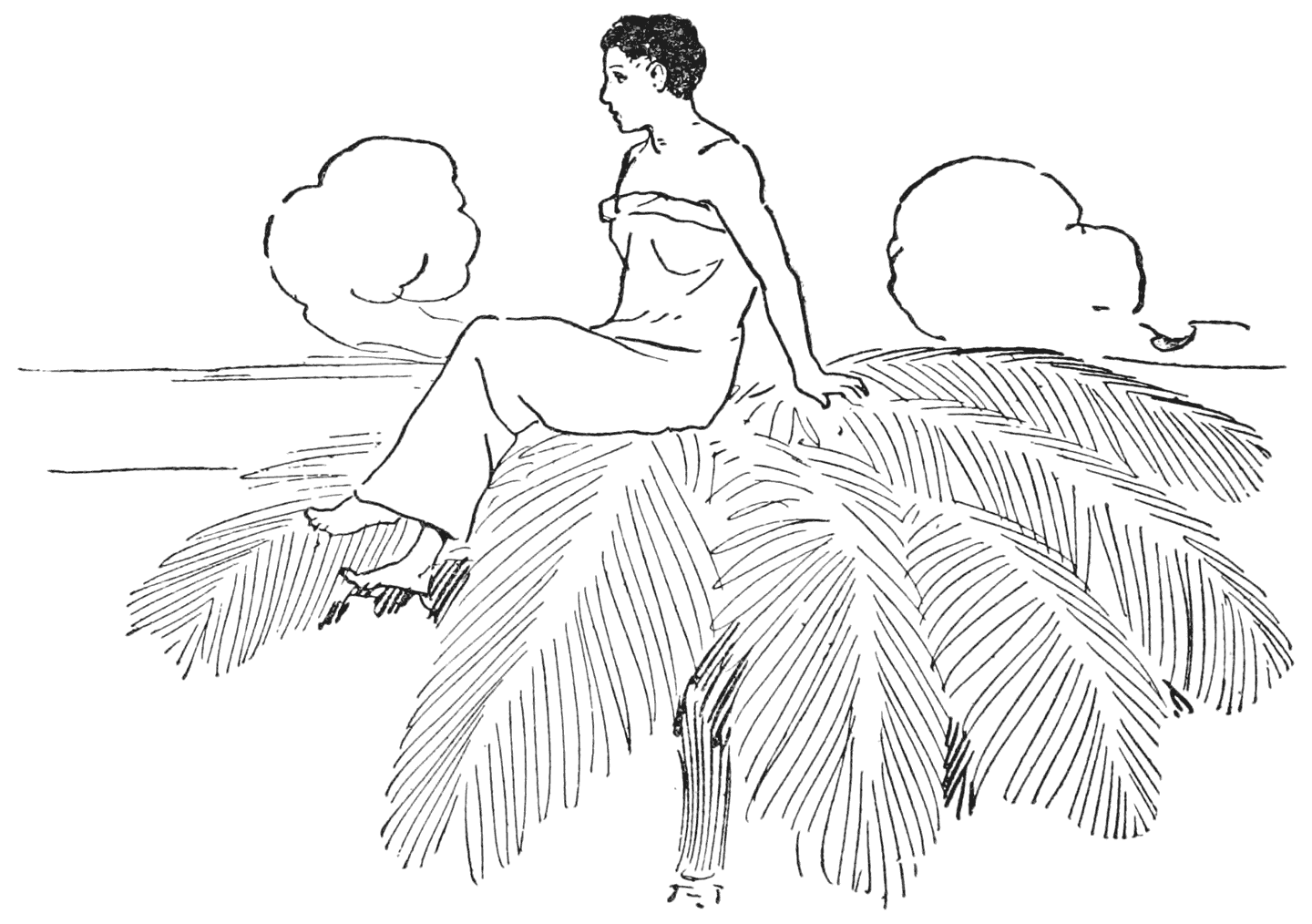

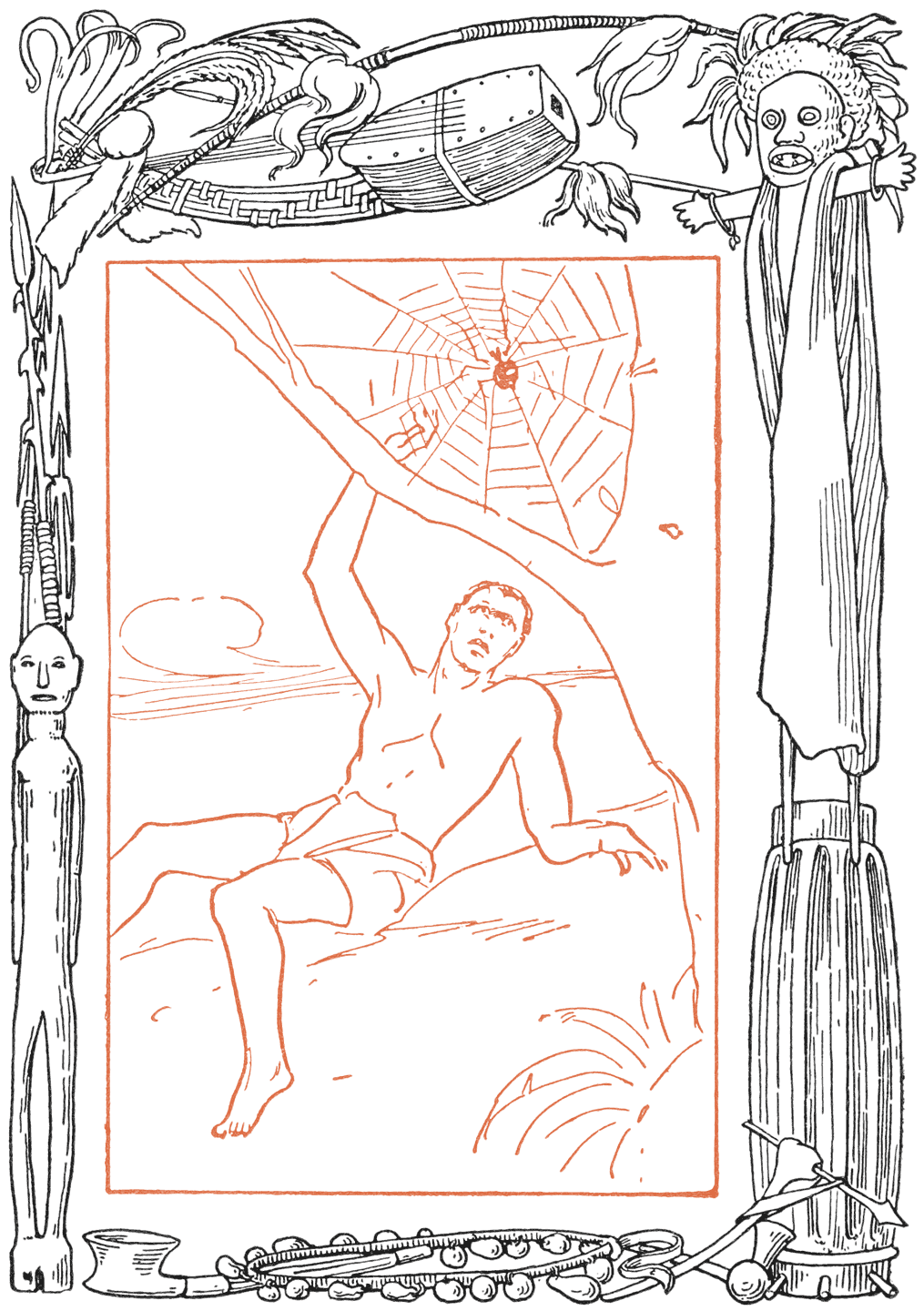

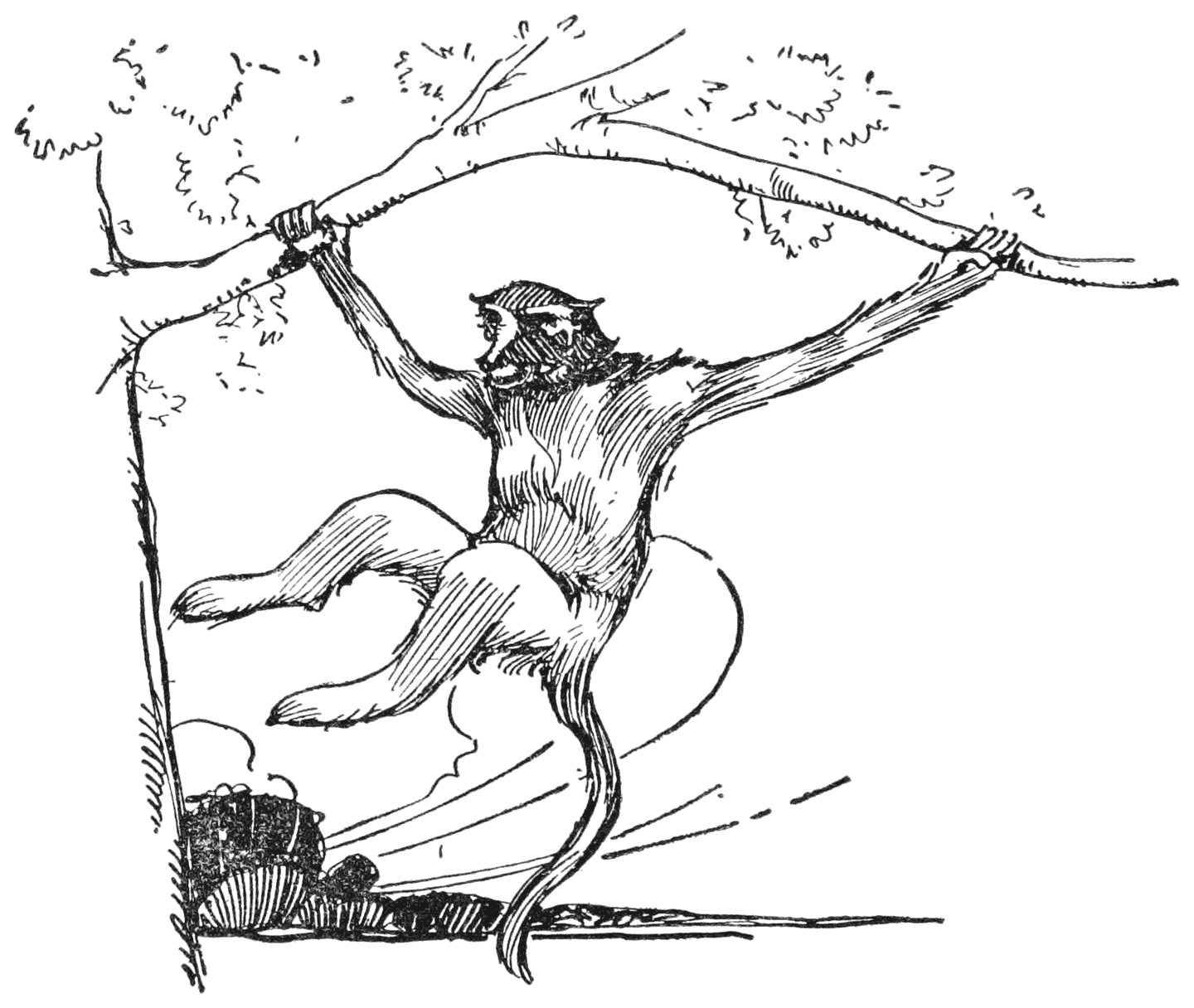

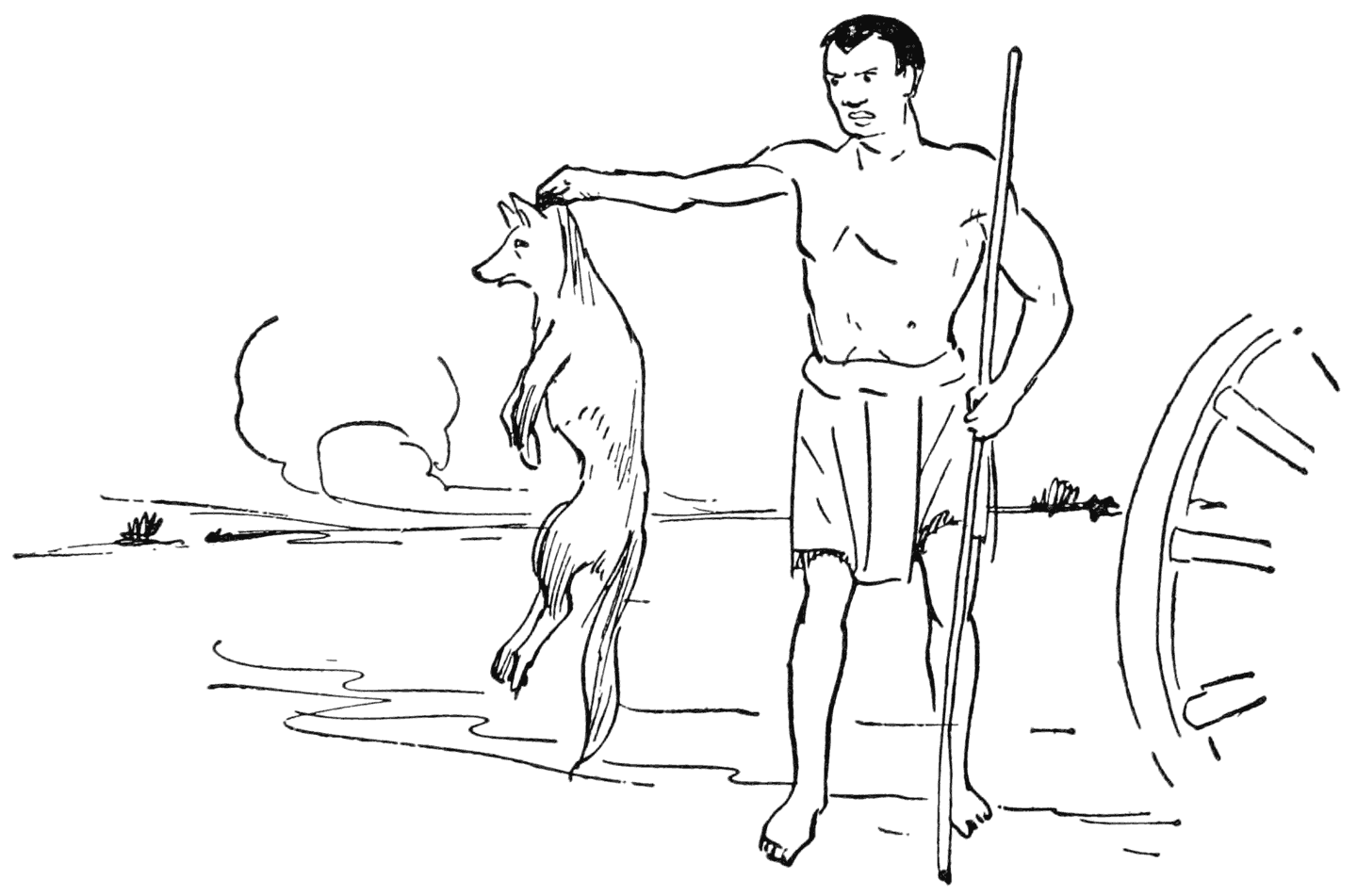

So the days went on until one morning her husband’s breakfast did not please him,

and he was so angry that he snatched her up in his trunk and put her right up on top

of a tree which grew near the hut. “You shall stay there until I come back,” he said.

It was not much of a punishment, and his wife did not mind it at all, for it was rather

pleasant than otherwise. There was no cooking to be done up there, and she could see

much farther over the plain from the top of the tree.

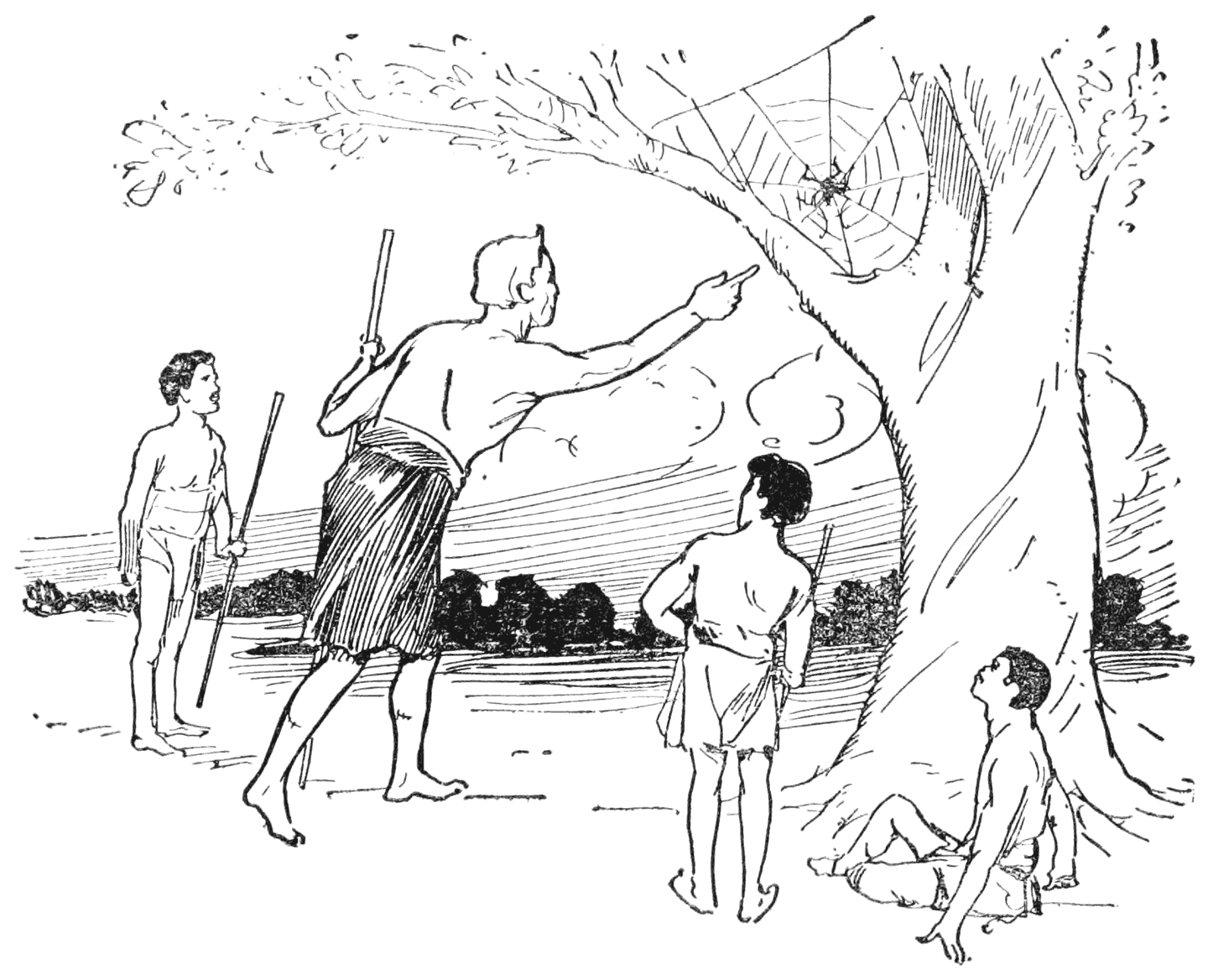

So Parle looked and looked, always to the north, all the morning, but in vain. At

last, about noon, two black dots appeared on the line where the plain met the sky,

and Parle forgot how hungry she was as she watched the dots grow larger and larger.

“I wonder if they are lions,” she thought. “No, [28]they are men!” she cried aloud. In an hour she could see that they were bushmen, coming

swiftly across the plains; and in a little while she recognized her brothers, who

had traveled all this way to find her and hear if she was happy.

It did not take long for the oldest brother to climb the tree and bring her down.

And then how glad they were to see each other! Parle cooked [29]them some food and while they were eating it she told them how unhappy she was, and

made them promise to take her away.

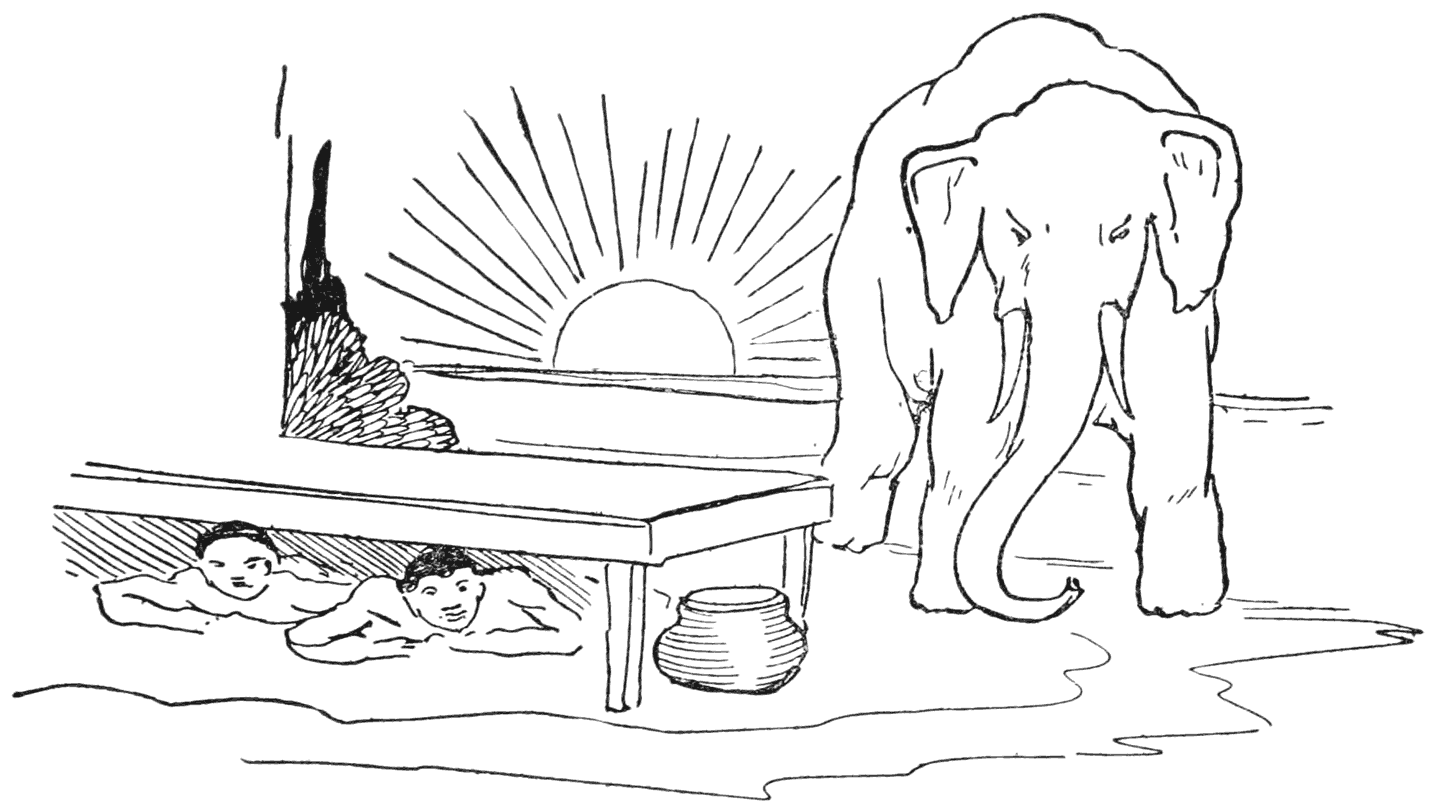

Then they planned how to get away. “We must wait until night, or Lomi will catch us,”

she told them. “I will hide you until it is safe to start.”

There was a raised wooden platform behind the hut, and underneath it Parle kept firewood,

rugs to sleep on, and all kinds of things for which there was not room in the hut.

So she stowed away her brothers in there; and when Lomi came home, [30]although he sniffed suspiciously around the hut, he did not catch a glimpse of them.

Then at midnight when Lomi was fast asleep, his wife roused her brothers, and they

prepared to leave. “We are going to kill the elephant,” whispered the older brother.

“Indeed, you must not,” replied Parle decidedly.

“If you won’t let us kill the elephant, you must let us take his cattle, at least,”

said the younger brother.

So they set out, driving the cattle before them; but Parle left behind one cow, one

sheep, and one goat, telling them to make as much noise as they could during the night.

Lomi waked several times after they had gone, but when he heard the noises the cow,

the goat, and the sheep made, he concluded that all his cattle were safe, and went

to sleep again each time.

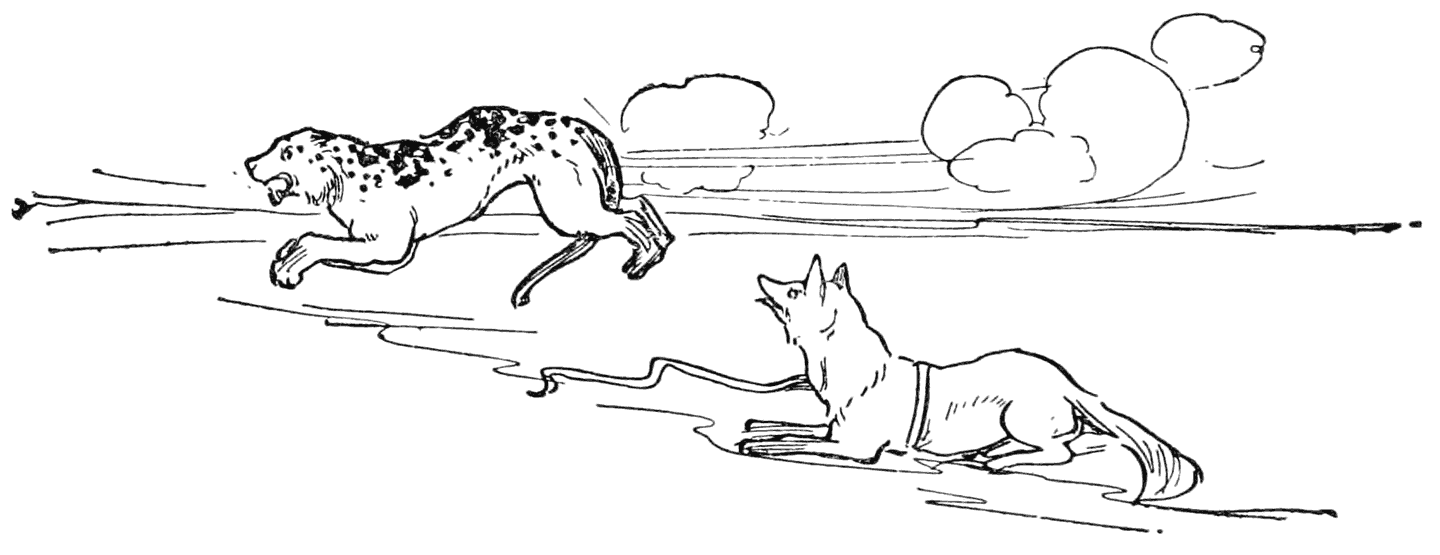

Early in the morning he found out his mistake, but by this time Parle and her brothers

were far away across the plain. Soon he was in pursuit of them, and how fast he did

tear over the ground!

[31]

[33]

Driving the cattle before them, Parle and her brothers flew on and on; but the terrible

elephant got over the ground much more quickly than they could, and at last was only

a half a mile away.

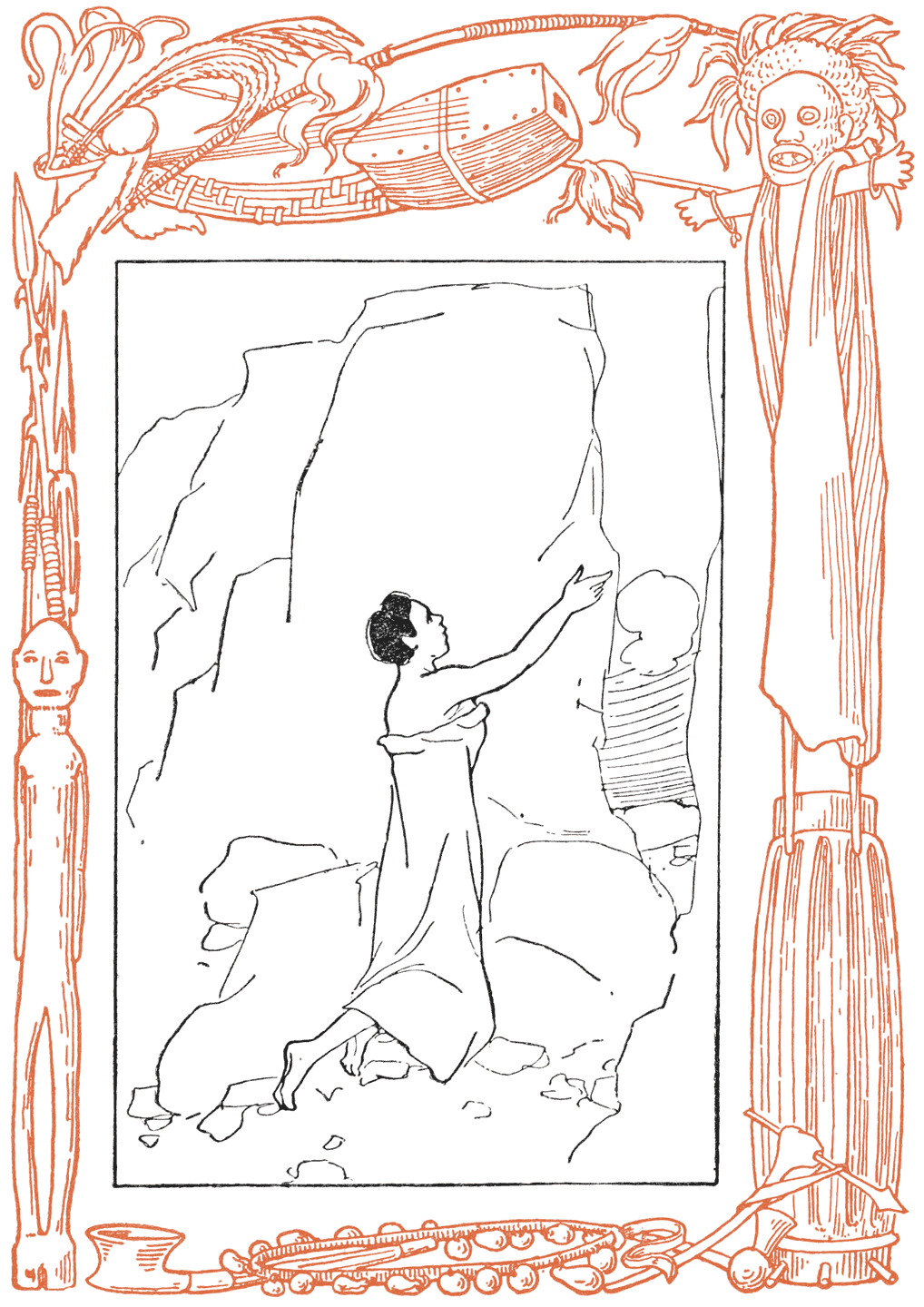

And as if to make it worse, right ahead of them were great rocks, too steep to climb,

and so high they seemed to touch the sky. Then they gave themselves up for lost.

But just then Parle remembered a spell which Ramil, the witch, had taught her, and

cried out:

“By the lilies which grow

On the still lagoon,

All silver-white

Under the moon,

Stone of my fathers,

Divide! Divide!

Let us pass through

To the other side.”

As the words ceased, the rocks opened, and Parle with her brothers and the cattle

went safely through.

[34]

And how angry Lomi was when he saw the rocks close behind them!

On the other side there was a beautiful lagoon shining in the silvery moonlight, with

white lilies floating on the water, and it looked so beautiful that Parle ran, with

a cry of joy, to bathe her face and hands in it.

“I wonder if Ramil’s spell brought it here? Or was it here all the time?” she cried

in bewilderment.

So Parle and her brothers rested there for a time, and then went on again to try and

find the river of which Ramil had told them so often. It would be nice to know whether

they found it or not, and were washed white in its waters, but you will have to decide

that for yourselves.

There is one thing quite sure, however, and that is, Lomi never saw Parle again, which

served him quite right.

[35]