Title: Codes

Author: Romaine Lowdermilk

Arch E. Giddings

Release date: November 2, 2025 [eBook #77172]

Language: English

Original publication: Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Co, 1924

Credits: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

The world of the telegraph man is strange to many a man in the street, but offers romance and excitement to those who know it.

The fellow, DeMars, blew into the operating room of the National Consolidated Telegraphs at Los Angeles late one autumn afternoon. He talked two minutes with the chief operator, and went to work that night on second Chicago, a wire conceded generally among the operators as the fastest in the house.

DeMars, dark and slender, had a penchant for fine raiment. He wore his stylish suits and haberdashery in a distinctive manner not often found, among drifting “ops” and wire-men, whose working hours are spent amid the deafening din of the operating room with the fingers of the right hand steadily hammering a telegraph key and the fingers of the left simultaneously “marking off” messages with a pencil. DeMars wore a small mustache, up-curled in a foreign style. He could easily have passed as a Frenchman of wealth. But his speech was distinctly American.

“Say, girlie; how about a show tonight?” he had addressed June Harmon, typist to McPhail, the chief operator, on his second day. “I’m new to this town, and I’d like to see some of the life. They say there’s a keen orchestra at the Cinderella.”

June Harmon was accustomed to turning down proffered entertainment, and took no offense at DeMars’s rather precipitate invitation. She only smiled and shook her head. “I don’t go out nights,” she said decisively.

“Of course you don’t,” scoffed DeMars. “None of you girls do.”

“Some of us don’t.” And she bent over her work.

“Oh, well, there’s plenty that will,” he answered defensively.

“Indeed there are,” June had replied pleasantly.

DeMars shrugged and turned back to his own desk.

June Harmon, modish and pretty, carried beneath her outward softness a sophistication gained in the six years since the death of her father who had once been chief in that very room. With a younger brother who, until the last few years, had been dependent upon her, and a sweet mother at home, June had managed the family finances and affairs. It had not been an easy task and now, though barely twenty-four, she was a woman capable of taking care of herself in any kind of company and still maintaining her poise. June Harmon was straightforward, companionable and honest, always ready with a smile for the newest messenger-boy, or the loan of carfare to some over-spent old operator.

From her vantage point as McPhail’s typist she could cast an appraising eye over every operator in the room. Of them all she would have preferred any before Hugo DeMars as a companion to her brother Ralph, who had but lately graduated from the student class into the way wires. But, like the usual run of ops who drifted into the National Consolidated, DeMars had made rapid acquaintances among his fellow workers. His was an attractive personality, and he a liberal spender. Gradually his circle had narrowed until Ralph Harmon remained as his especial crony. They usually lunched together at the little dairy counter downstairs, and were often together nights.

June cautioned her brother about it. “Ralph,” she said, “I wish you wouldn’t run with DeMars so much. He isn’t doing you any good. Besides, I don’t like his--well, his looks.”

“Well, I do,” retorted the boy impatiently. “You’re always butting in on who I go with and who I don’t. Hugo DeMars is all right. He’s been all over the world, and he knows more about the telegraph business in a minute than old Andy McPhail or any of the rest of ’em in a week. And that’s not all. I’m going with his sister now; that’s where I was last night. Hugo introduced me to her. She’s just about my age, and she’s a pippin.”

“Oh, how romantic.” June elevated her brows in mock wonder, and she eyed her eighteen-year-old brother humorously. “And so it is an affair of the heart?”

“Aw-w-w, you don’t know nothin’,” Ralph grumbled. “Mignonne DeMars has it all over most girls for looks. She doesn’t know anybody in this town and she’s lonesome.”

“I see,” remarked June thoughtfully, but with a twinkle. “And you’re the lucky one. Her brother Hugo has been looking the boys over for someone with the class to be worth while introducing to her and he has picked you.” June dropped her bantering tone and became friendly, almost motherly. “I’d like to see her myself, sometime. Can’t you bring her around to the house sometime when mamma and I can fix up a little party? We can have some of our crowd in and we’ll make Mignonne feel more as if she were among friends.”

Ralph’s reply was unenthusiastic, but he warmed toward his sister. June’s little parties always turned out pretty well, but he wasn’t just sure how Mignonne De Mars would like a cozy home party. Mignonne seemed rather to prefer a good show or a lively dance orchestra. Ralph was trying to create an impression with her, that he was older than he looked; a man of much worldly experience. And he felt that one of June’s parties, given in their own home with his mother present, would serve to break down that illusion.

“Mignonne is the prettiest girl I’ve ever seen,” he told June, by way of evading direct reply as to when he could bring his divinity to a home party, “and she’s just the kind of a girl a fellow can pal around with. She works at the Mutual Trust--she’s a steno--and she knows money doesn’t grow on bushes and doesn’t try to spend a fellow like some of these girls. All she wants is a good friend she can trust.”

“That’s fine,” June encouraged him. “I’m sure we’ll all love to meet her.”

“I’ll say you will,” Ralph prophesied, leaving the time for the meeting rather vague. For somehow he felt that maybe, after all, Mignonne was a year or two--well, maybe three or four, his senior. And both June and his mother always preferred that he go with girls his own age or younger.

DeMars’s entry into the Los Angeles telegraph office was followed two weeks later by that of another newcomer. The new man was plainly a “boomer.” Two shifts and everybody knew all the places he had worked, the positions he had held, and what kind of tobacco he liked. He was a stalwart, genial young man, and “flagged” under the name Clyde Winship. He had come out from the Chicago office when the winter began to settle over the lake. The old-timers looked up from their keys out of faded watery eyes and harked back to the days when they, too, were young and followed the whims of itinerant fancy, booming on to warmer climes when winter threatened.

The young operators on the job took Winship in tow and showed him the joint where he could get good roast beef for a quarter and took him to the Seneca Hotel “where all the boys stay.” From the first Winship seemed to take an especial interest in DeMars, and also in Ralph Harmon. But the two, DeMars at first, then later, Ralph, avoided his advances as though their own acquaintance was enough and they considered the newcomer an interloper. Gradually Winship’s attention began to center about June Harmon, and he took to sidling over to her desk at every opportunity. Two weeks after his entry in the big office he asked for a date.

“There’s a good show out at the Stadium,” he addressed June diffidently. “It’s a big pageant, the Wayside Cross, and they all say it’s worth seeing. I’d like to see it and I wish you’d go with me?”

June shook her head. “I--I don’t go out much,” she said kindly.

Winship’s face fell. “Well,” he countered, “you’ll go sometime--with me--uh, some place, won’t you?”

June had to smile at that. “Possibly.”

“I hope so,” he said earnestly.

The next day he again approached her. “Maybe you’ll let me come up to your home some evening and see you?”

“Oh, you see enough of me right here.” June Harmon did not care for friendships formed upon short acquaintance. She had seen too many such affairs end disastrously.

“I don’t see enough of you,” he insisted stubbornly.

But her only reply was a bright smile as she turned back to her desk. He went soberly to his own. At noon Winship contrived to meet Ralph alone in the cloakroom as they went out on their twenty-minute “short” for lunch.

“Ralph, I’ve been wanting to tell you something,” he began quietly. “Briefly it’s this: That fellow DeMars is too fast for a young fellow like you to try to follow. Take my advice and lay off of him. You’re liable to contract expensive habits.”

“Aw, what’d you know about it?” frowned Ralph. “Where’d you butt in on who I go around with, I’d like to know?”

“Oh, I just didn’t like to see a youngster like you hitting too fast a gait.”

“Well, don’t worry yourself sick about my gait,” Ralph sneered, as he grabbed up his hat and coat. He shot from the place bound for the little cafe where he and Mignonne cozily lunched each day.

Every op was indignant when Winship got canned. He had been with them barely a month, but in that short time had won a place in the hearts of all. That is, all but DeMars.

Winship was accused of “padding” his numbers. He had been working on Seattle the morning previous and the records showed that ten whole numbers were missing. It was paltry dishonesty, this skipping of numbers to increase an average, though many an operator has done it with safety for the reason that the laborious checking makes discovery unlikely. But cheating to gain the few cents bonus for the greater number of messages handled is disdained by all save those of lesser character. It did not seem that Clyde Winship would be one of these, but on the face of the charges he was. The men knew Winship had worked on Seattle but part of the morning, and that when he had been changed to another circuit DeMars had taken over the key.

“It’s DeMars,” they charged. “He framed you; and you don’t seem to mind it. Why don’t you order McPhail to investigate?”

“Oh, I don’t mind,” was Winship’s easy rejoinder. “Maybe I did it myself. There’s lots of jobs as good as this.”

Later when he stood at June’s desk to receive his pay his eyes held a quizzical look. “Aren’t you going to do anything to clear yourself?” she demanded. “All of us are sure it was DeMars. Can’t you prove that it was?”

Winship’s demeanor was unruffled. “What’s the use? Jobs are easy to find. One’s as good as another.”

“You’re a sheep like all the rest, Winship,” June said in a disappointed tone. “I thought you might be--different. But I guess I was mistaken.” She handed him his pay and held out her hand. “Well, good-by and good luck.”

He took her hand gravely, held it a moment and then went out through the swing doors. One of the ops coming in later said he had met Winship on the street and that the latter had told him he was bound for El Paso. The ops shook their heads over their desks. Another good man gone wrong, they said to themselves. That night his room at the Seneca was occupied by a new man. Winship had left no address.

Noise was indispensable to Fred Hess, the night money clerk. Behind the woven steel inclosure of the Money Transfer Department he labored to its rhythm with almost fanatical zeal. The main office of the National Consolidated Telegraphs teemed with business at six o’clock in the evening, and Fred Hess teemed with business behind his steel wicket. Night letter traffic poured in, and from every part of the brilliantly lighted lobby came an intermittent babble of conversation.

Detached, yet a part of all this racket, and dignified almost to the breaking point by the title of money-transfer clerk, Fred Hess, his round head on its long neck arching from his collar like some weird bent-over toadstool, concentrated on his work. Apparently miles away, submerged to the ears in a stack of work on the desk, it seemed impossible that anything short of a fire alarm or an after-dinner earthquake could interrupt him. Yet suddenly he straightened, and pressed his face against the meshed grill-work. A shrill whistle came from his puckered lips and he beckoned awkwardly to someone in the crowded lobby.

Ralph Harmon answered the summons. Ralph had been lounging in a seemingly aimless manner in the lobby, but Fred, apparently so engulfed in his labors, had spotted him at once.

“Say, Ralph,” Fred began as soon as the boy came within speaking distance, “got time to take my place a few seconds while I go out in the alley and take a smoke?”

“Sure,” Ralph replied obligingly. It was not the first time he had so favored the night money-transfer clerk.

Fred slipped from his stool and snapped the bolt on the little door at his side. Young Ralph Harmon stepped in and took the stool, while Fred shot out at the rear into the alley where the messengers congregated.

On this night Ralph Harmon had not come aimlessly into the lobby and Fred’s range of visibility. He wanted Fred to ask him to substitute. He had been in the lobby all the previous evening hoping to gain entry to the money-transfer desk, but Fred had not called him. Tonight luck had been better.

Now that he was actually seated at Fred’s desk. Ralph glanced carelessly about to see that he was not being especially observed. Disinterestedly, and with an air of its being only a part of his work, he pulled open the upper right hand drawer of the desk where change and the code are kept. There was not a large amount of cash, as large sums would be in the safe. The change drawer carried only a small amount.

But there was the code.

The code, printed on a white sheet and affixed to a piece of cardboard by means of clips, bore the code-words for amounts from one dollar to ten thousand. Though the intervening numbers were not represented, the units were, and from them any amount could be coded.

Ralph’s errand was to pick out the words coding the amount, $9852. In his mind ran the words he had been remembering the past three days; “Nine-thousand word, eight-hundred word, fifty-two word.” Rapidly he ran his eyes over the sheet. There was “NULLIFIED,” the nine-thousand word; “OVERTHROW,” the eight-hundred word; “DEBAUCH,” the fifty-two word. “Nullified Overthrow Debauch,” he repeated to himself. “Nine thousand, eight hundred and fifty-two bucks! Whew!” Then at the bottom of the sheet were the “Vigilant” and “Caution” words for each separate day of the week, each one different, yet each one meaning pay--key words denoting the manner of payment, and fully as important to the moneygram as the code words for the amounts. But Mignonne had told him there would be no need for those all-important words, as she did not intend to use the code against the Telegraph Company. And Ralph was convinced that a moneygram without the pay word could exercise no swindle upon the company, as none save those in charge of the code knew a word of it, and at that, the pay words changed each day.

Mignonne DeMars had young Ralph Harmon well under her supple white thumb. Indeed, she was the type who could put many a full-grown man under control. So the handling of Ralph had been but a bit of uninteresting side play. Still, some of Mignonne’s work had been so realistic that Hugo DeMars had waxed exceedingly jealous, but the dainty Mignonne reminded him that his keeping his temper down and his mouth shut meant a trifling difference between twenty thousand plasters and nothing. With this conclusive reminder DeMars managed to control his emotion and continue to accord young Ralph Harmon all due cordiality.

And then one night, from a strategic place upon the sofa of the little library of the DeMars apartment, Mignonne confided to Ralph that she was lonesome and unprotected and that she longed for a nice home down in Florida or Havana or somewhere, with a nice young man like him. His heart swelled with a desire to accompany her to Arcady and, with all the lights turned out but the big piano lamp in the other end of the room, she let Ralph tell her of his love. He thrilled at the tears which glistened in her dark eyes, and nearly fainted when her slender, rounded arms went about his neck in complete admission of her own love.

After that, Ralph Harmon was ripe for anything that promised easy or rapid money with which to fulfill their dreams. And Mignonne suggested the way. Twenty thousand dollars would be about the right amount for a starter, she explained, and all he had to do was get the code words, and she would do the rest.

“You see,” Mignonne explained to him, “when we get the code words I’ll spring a faked-up moneygram on some crooked race-gamblers down at Tia Juana who cheated my poor dear father out of every cent he had once. I’ll just be getting my own father’s money back, and nobody but the crooked gamblers will lose a cent. It won’t be wrong to gyp a crook, will it, dearie?”

Ralph Harmon was dubious. “But the Telegraph Company--you’re sure they won’t lose? Won’t the code work back onto them?”

“Silly, of course not! Only those racetrack gamblers,” Mignonne had purred, “I promise that. And then, why, to you and me it will be a fortune.”

With her slim form cuddled in his arms young Ralph Harmon agreed that it would, and she rewarded him with a kiss that caused Hugo DeMars, his eye glued to the key-hole, to double up in anguish.

And now Ralph had done as Mignonne instructed. He had secured the code words. He replaced the code-sheet, closed the change drawer and was contentedly holding down Fred Hess’s stool when that worthy returned from his cig. in the alley.

“Much obliged,” said Fred.

“Much obliged,” returned Ralph. Arcady seemed very close now. And, with the code words fresh in mind, he hurried straight to Mignonne.

When Clyde Winship left the employ of the National Consolidated under cloud of having padded his numbers he had not gone to El Paso as he contrived to leave word that he had. Instead, after a quiet interview with the superintendent and a brief talk with the traffic chief, he went straight to the wideawake agent of the apartment house where the DeMars had rooms, stating he desired a room for one month or longer. Vacancies, the agent assured him were a positive rarity. However, by a stroke of great good fortune one small apartment had been vacated. Winship accepted it eagerly, paying the required deposit. He left the place whistling happily.

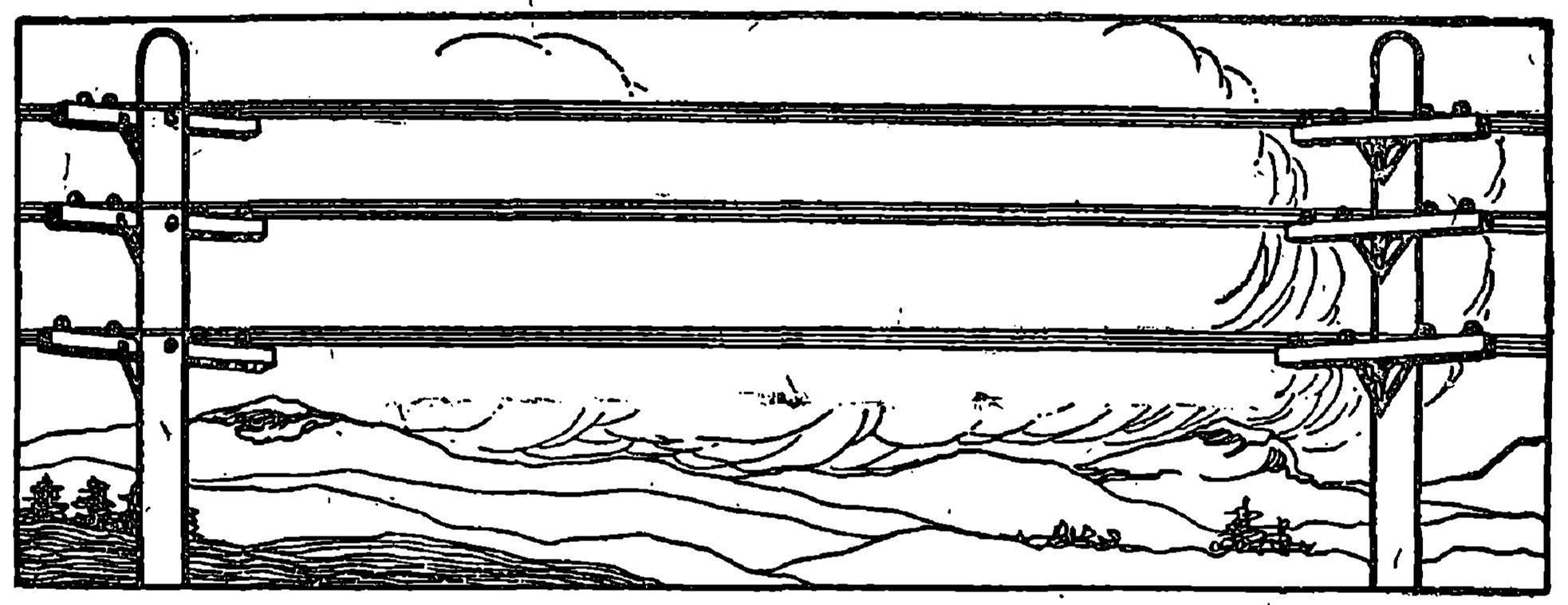

Telephones had been more than just telephones to Clyde Winship ever since the National Consolidated Telegraphs had been converted to the use of pony telephone circuits for communication between the main and the branches. Originally all office communication had been in Morse, but the company had learned that it could hire a telephone operator for less than a Morse op, and all messages for local delivery were routed out to the branches via phone if they could be more expeditiously delivered in that manner. To make the business more efficient the National Consolidated had secured a newly patented and extremely sensitive telephone transmitter much superior to the ones in general use. Winship, whose experience with the company covered a wide range, had made an especial study of the new phone, and the little trick of connecting his apartment with that of the DeMars was as simple as chewing gum.

So, when he went to his new apartment, one of his bags contained, like the black bag of many a famed detective, appliances and tools for tapping in on Apartment D. His first act was to equip the small wallphone in his own room with an extension cord to an easy chair. Next he stole down the hallway to the DeMars door. From somewhere on the floor came the whine of a vacuum cleaner and the banging of furniture. For a full minute he tried key after key. The preliminary grindings of the elevator as it started upward came from the shaft, and he darted back to his room. After what seemed an eternity he heard the elevator go down and a door slam on the floor above. Back at the DeMars door he finally found a key in his collection that turned the catch. He slipped inside.

A bottle and some whisky glasses on the library table was the first sight to greet his eyes. A door leading to the bedroom was ajar. He glanced through the crack. It was empty, the bed tousled, and numerous cigarette stubs littered the floor. Clearly Mignonne was a slattern in the art of housewifery. The wall-phone was the same pattern as his own. He removed its transmitter, substituting the more sensitive one supplied him by the traffic chief, trusting that the DeMars used the phone so little as not to notice the difference in shape of the transmitter.

Five minutes later he had a duplex wire under the DeMars carpet leading back through their apartment and out into the hall, through a hole bored beneath the rear door sill and along the hall carpet to his own room.

For two days, whenever the DeMars apartment was occupied, Winship was at the other end of the wire.

Long is the list of those who have attempted to defraud the National Consolidated Telegraphs Company through the medium of their money transfer service. But brief is the tally of successful ones. Every safeguard is in use, every loophole watched. The lid is ever ready to drop on the sharper who thinks he can match his wits against the system. Winship, with his phone, was but a part of the system. Sent out from Chicago on the trail of the dapper DeMars whom the company suspected of having turned a fraudulent trick at New Orleans, he had taken a position as an operator and, finding that was not the place from which to put his finger on DeMars’s game, had padded his numbers, received apparent discharge and seemingly left the town for El Paso. But with his phone, and in close communication with the superintendent, he lay in wait, the coils of the law and the system gradually closing about Hugo DeMars and only awaiting concrete evidence of attempt to defraud.

Ralph Harmon pecked away at his typewriter amid the din of some three hundred instruments in the long operating room and fumed at the slowness of the sender in Pasadena. It was barely two o’clock, and with two hours to go it was irritating to copy the painfully deliberate sending of some old lady afflicted with telegrapher’s cramp, and who should have been superannuated a decade ago. With a good fast man on the other end the work would be bearable, but now Ralph’s thoughts flew to the time when he and Mignonne could get away from the tedium. Havana, Paris----

“Bk.” The word came in over the Pasadena wire. Mechanically Ralph ceased his typing, for “bk” meant “break,” or in other words, “don’t put this down.” Then the Pasadena op laboriously thumped out, “I’m going to copy for a while. Hand’s getting tired. Want to change over?”

Ralph looked over at the hook and saw there were perhaps two dozen messages to be sent. A good hour’s work with her as receiver. Oh, well, she wasn’t such a bad scout. She couldn’t help her cramped sending. He touched the key and tapped out his “ok.”

He changed over to the chair next to him and caught the handful of messages off the hook. Before he was midway through the first someone tapped him on the shoulder. It was Hugo DeMars.

“Mignonne’s out in the hall, kid,” DeMars told him. “Wants to see you about something. Here, I’ll take your key till you get back.”

Ralph drew a breath of relief. His nerves had been at high tension the past few days, and he was thankful for a few moments away from the wire. He couldn’t imagine what Mignonne wanted to ask him, but it thrilled him to know she was near. He pointed out to DeMars the place he had left off, and went out into the hall. As he would be gone but a moment he did not trouble to explain to the chief that DeMars was sitting in on Pasadena. It did not occur to him that there was always the chance for a substitute to send through a faked message for which the blame could be laid at the door of the original operator.

Ralph, like other young operators, thought the company’s check system unbeatable. He knew that each message bears a sending number and, after being sent, goes to the checking room to be audited for omissions or duplications, all a part of the telegraph company’s aim for accuracy. Sometimes a number is omitted. An operator may have sent message No. 44 and then sent No. 46. If the error is not detected by the receiving operator at the time, the checking room catches it, and sends through a message: “This represents our No. 45 to you.” Consequently Ralph felt perfectly safe in leaving DeMars in his place while he was talking to Mignonne. For he never once considered the other capable of duplicity.

But DeMars had a plan of action laid out. A plan he had successfully worked before. Finishing the message Ralph had begun, DeMars began on a moneygram as the next one. This he composed from memory while his eyes were on the authentic message for which he was substituting his fraudulent one.

He had the code-words. Mignonne had supplied them, but these without the pay word of the day were worthless. But throughout the day he had watched the money transfers that passed through his hands. Four of them carried the pay word RANKLE. Only one had SIMMER as the pay word. From this he gathered that RANKLE was the payword for the day representing “identification waived” transfers, as the greater majority are sent that way to avoid the delay occasioned by the rigid care exercised by the company in paying vigilant and caution transfers.

So, with message No. 44 before his eyes, he composed and sent the following moneygram from memory in place of it:

REPRESENTING MUTUAL TRUST COMPANY RANKLE MARIE IRVINE PASADENA NULLIFIED OVERTHROW DEBAUCH UNITED LUMBER AND SHIPPING COMPANY.

He then marked off the real No. 44 as having been sent. He went on with the sending, a satisfied smile on his face for, during Ralph’s twenty-minute lunch relief which the boy had stretched to nearly half an hour at the cozy cafe where he and Mignonne were accustomed to lunch together, DeMars had contrived to take Ralph’s place that day. On the Hollywood line he had sent out a moneygram, the duplicate of the one he had just sent to Pasadena. So Mignonne, within the next two hours would visit both the Hollywood and Pasadena offices with letters and other identification from the Mutual Trust where she worked as a stenographer. She would collect the money, practically twenty thousand dollars on the two orders, and the fraud would not be discovered until the moneygrams were checked back to the originating point which was given as “Po”, Portland, Oregon.

When Ralph returned to his key he found DeMars tapping out messages to the Pasadena office. He took his place, and the other went back to his own desk. Out in the streets Mignonne stepped into a taxi, and whirled away toward the Hollywood office to collect the first of the two moneygrams.

A little more than an hour later word came into the superintendent’s office that Mignonne DeMars alias Marie Irvine, had been apprehended at the Pasadena office as she attempted to cash a faked moneygram. She was now en route to Los Angeles in the custody of the special officers who had witnessed her receiving money at the Hollywood office and later followed her to Pasadena as directed to do by Clyde Winship, the company’s representative.

The whole affair had occupied barely thirty minutes of the superintendent’s time. And the DeMars case was entering its zero hour.

Shortly thereafter Clyde Winship slipped into the superintendent’s office and, in response to the official’s nod, took a chair. The superintendent, with a smile at Winship, pressed a buzzer.

The door opened and Ralph Harmon entered, followed by the chief operator. The boy’s face wore a grim look, plainly worried, but with no manifestation of fear. Winship’s opinion of June Harmon’s brother went up considerably.

“Why, hello, Winny,” Ralph greeted Winship surprisedly. “You back looking for a job again?”

Before Winship could reply the superintendent turned on Ralph abruptly. “Your name is Ralph Harmon, is it not?”

“Yes, sir.”

“How long have you been with this company?”

“I was a messenger three years while I finished school, then was on as student operator. I’ve been working here as an operator for a year.”

“What wires did you work today?”

Something of his assurance left the boy’s face at this question. He hesitated, fingering a button on his coat before replying. “Well,” he began slowly, “I worked on El Paso and Tucson this morning. Then I worked some of the way circuits, after lunch, and after that----”

“That’s enough. You say you worked way circuits. What wires were they?”

A look of fear crept into the boy’s eyes. He glanced wonderingly at the official, and then at Winship and the old chief operator. “I don’t remember. I--oh, yes, I was on Redlands and San Bernardino and Pasadena----”

Instantly the superintendent whipped a telegram from his desk and held it before the boy’s eyes.

“And you sent this?”

Ralph examined it, his face drawn. It was the moneygram Hugo DeMars had sent. As Ralph read the code words that he himself had given Mignonne his eyes sought the door. His mind flashed to the moment DeMars had taken his place on the Pasadena wire. Mignonne had been in the hall waiting to tell him that she and her brother Hugo were expecting to go down to Tia Juana that evening after work and be gone for two days. She had said they were going to collect the money from those crooked gamblers. Ralph recognized that he could scarcely prove that it had not been he who sent that moneygram, so cleverly had DeMars’s work been planned.

Suddenly he determined not to try. Ralph pictured Mignonne in prison as a result of his having obtained the code words for her. Somehow it seemed to him that had he not secured the code from Fred, Mignonne would still be innocent of crime. He sought only to protect her.

“What have you to say?” the superintendent demanded sharply.

“Yes. I--I sent it,” Ralph faltered.

The superintendent was unrelenting. “Portland never sent such a message,” he went on severely. “Harmon, you’ve committed a fraud against the company, and if you get off with less than ten years you’re lucky. Do you confess to sending this message, and the one to Hollywood?”

Ralph caught his breath. That another such message should have gone to Hollywood was beyond his belief, but he thought of the code and again of Mignonne.

“Yes,” he repeated mechanically, “Yes, I sent them.”

The superintendent leaned back with a sigh of relief. He eyed the youth appraisingly. “You’re a liar,” he said good naturedly. “Young man, I’m mighty glad to tell you that you’re a liar.”

Ralph broke down completely. He sobbed and buried his face in his arms.

“You’ve been in bad company, young man,” the superintendent said. “You’ve had a good record with us, but that woman and her husband--” He paused to let the full significance of this information sink into the boy’s stunned consciousness. “Her husband, Hugo DeMars, took occasion to substitute for you and sent these two wires.

“Thanks to Mr. Winship, he knew of the plan, and now we’ve got the pair, along with evidence enough to send them up for twenty years. We don’t blame you for trying to shield the woman--you’re a young fool like most young men. But we can’t risk having you here. We know how you filched the code words under the impression they could not be used to defraud the company. But you see it didn’t work. And we can’t take chances on you here. You’re fired. And you’re lucky we don’t send you to the pen along with your--your friends.”

When the superintendent had finished Ralph looked up. “It’s a lesson I’ll remember all my life,” he choked childishly. “I’m glad they didn’t get to rob the company, and I p-promise never t-to do anything wrong again. I d-don’t know how to th-thank you.”

“The company holds no ill will toward you,” the superintendent went on impressively. “Only, we can’t afford to keep weak sisters on the job. But I’ll give you a tip. We’re putting in a new manager out at the Pasadena branch, and he is looking for an assistant. He says he will take you in charge, and guarantee to keep you in line. He is a man we have faith in, and if he’s willing to take the responsibility we’re going to let him.”

Ralph straightened perceptibly. A steadier light came into his eyes.

“Just tell me where I can find that new manager. I want that job. I want a chance to show the company that I can go straight. All I want is another chance to----”

“Well, you’ll get it,” Winship interrupted kindly. He rose and held out his hand to the boy. “I’m taking over the Pasadena branch, and you’re hired. Come along, let’s go out and look it over.”

A week later Ralph invited his new manager home to dinner. June was having some of her friends in, and the little dinner was assuming the air of a gay party.

“You’ve only been around Los Angeles two months?” one of them spoke to Winship. “And do you think you will like it here?”

“I think I’m going to,” Winship replied hopefully, and his glance strayed across the table to June. Her larkspur blue eyes met his own.

“Yes, I know darn well I am,” but his words were lost in the chatter of glad voices about him.