Title: The olive branch, and other stories

Author: A. L. O. E.

Release date: October 29, 2025 [eBook #77151]

Language: English

Original publication: London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1885

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

THE OLIVE BRANCH.

And Other Stories.

BY

A.L.O.E.

AUTHOR OF "EXILES IN BABYLON," "TRIUMPH OVER MIDIAN,"

"THE YOUNG PILGRIM," ETC.

London:

T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW.

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK.

——————————

1885.

Contents.

II. THE ASS IN THE LION'S SKIN

IV. A PEEP INTO A BACK-KITCHEN

XII. THE BOY AND THE BIRD'S NEST

XIII. SENDING HORSES TO TRAVELLERS

XVII. THE TWO STANDARD MEASURES

THE OLIVE-BRANCH

——————————

THE OLIVE-BRANCH.

"IF you are going for the fodder for our cow, Carlo, what say you to taking our little Rosina with you? It is long since she has been beyond our village, and a ride upon our trusty old Duchessa will do her good."

It was Bice, the wife of an Italian peasant, who spoke these words to her husband, as she stood at her cottage door, with her bright little girl at her side.

"What say you, Rosina?" asked the smiling father. "Have you a mind for a ride?"

The little girl clapped her hands for joy. "Oh, if we are going to the farmer's for the fodder," she cried, "then we will pass by Aunt Barbara's cottage. May I go in and see her, father, and carry her one of mother's little goat-milk cheeses that she always likes so much?"

Rosina saw with surprise a shade of sadness gathering upon her father's sunburnt face. And when she turned to look at her mother, Bice was brushing a tear from her eye.

"You cannot go to your aunt, Rosina," said Carlo; and his voice sounded almost stern to his child.

"Is poor aunt ill?" asked the little girl; for she saw that her mother was greatly distressed.

"Ask no questions, my child," said Carlo. Then, turning to his wife, he went on: "She cannot understand, poor lamb, why a woman should quarrel with an only sister, who never meant to give her cause of offence."

Rosina heard her father's words with increasing wonder. She knew that her Aunt Barbara had a peevish and angry temper, but she could not think how she, or any one else, could possibly quarrel with that gentle mother who had always taught Rosina to love and forgive. The child did not, however, venture to ask any more questions, though her heart was sad at the idea that any one could by unkindness bring a tear to her mother's eye.

"Perhaps, after all, Carlo," said Bice, looking up earnestly into the face of her husband, "it might be as well for you to let our little one run in and see her aunt, as you are passing her very door. Barbara has always been kind to Rosina; it might—" Bice's voice dropped to a whisper as she added, "it might do good—it could scarcely do harm."

"It would look like an attempt to make up with her," said Carlo, rather proudly; "and after her insolent conduct to you, I would not choose to take the first step."

"I would take not the first step only, but go the whole way, if I could but win back my sister to love me," said Bice, clasping her hands. "O Carlo, 'Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.'"

"I never knew any one more ready to forget and forgive than you are, Bice," said her husband; "it is all the greater shame to Barbara that she quarrels with such a sister. But she is a woman who would snap at any one who chanced to stand in her light. However, as you wish it, our little Rosina shall run in and wish her aunt good-day; a child should never be mixed up with the disputes of older people."

"And may I carry aunt one of your nice cheeses?" whispered Rosina, standing on tip-toe, and drawing down her mother towards her that she might breathe the words in her ear.

"Alas! Rosina, my darling, she would now accept nothing from me!"

"Not even a 'kiss?'" whispered Rosina.

The mother's heart was too full for reply; for, notwithstanding Barbara's unkindness, she was dear to her only sister. Bice could only lift her darling up in her arms, and half cover her rosy face with kisses.

"Half of these are for your own little girl, half are for auntie," said simple Rosina; and she resolved to be a trusty messenger, and deliver faithfully what she considered to be tokens of love and forgiveness.

Carlo started on his way to the farm, leading the patient and trusty Duchessa, while Fidele, the dog, ran by his side. The day was warm and bright, sunshine lay on the valley and gilded the distant hills, but Rosina sat on her ass more quiet and silent than usual—she had scarcely a word even for her old friend Fidele. Carlo might have missed her merry prattle had not his own thoughts been painfully occupied with the family quarrel. He little guessed what was passing through the mind of the child scarcely four years of age.

Barbara, it is true, had hitherto been always kind to Rosina; the child had seen her angry with others, but had never had a harsh word herself. Yet Barbara's temper was such that Rosina's love for her had always been mixed with some fear. What the child had just heard and seen had increased that feeling of fear to a painful degree. Rosina quite dreaded having to go alone into the presence of her aunt, the stern black-eyed woman, whose unkindness had made even her mother cry. Rosina would far rather have quietly passed the door on her ass; and she knew that a word to her father would be enough to make him spare her what she now felt to be a very great trial of courage. But then her mother's tears and her mother's kisses! Rosina could not forget these, and she ought to deliver them. Besides, her mother had said such beautiful words from Scripture; oh, if Aunt Barbara could but have heard them, surely she would become a peacemaker too, and never be angry or cross any more!

So, while the ass went on at her slow, steady pace, little Rosina was repeating to herself over and over again, "'Blessed are the peacemakers.'"

Her young heart beat faster as Duchessa stopped, as she often had done before, at the vine-covered porch of Barbara's door, over which hung clusters of ripe dark grapes. Rosina felt almost inclined to cling to her father's arm, and beg him to drive on Duchessa, for she dared not go in by herself. But even one as young as Rosina may be guided by conscience, and conscience was whispering to the child that her mother wished her to go, that it was right to go, and that the great God of peace could put kind thoughts into the heart of her aunt.

Barbara was sitting alone in a darkened room: it was dark because she had made it so; she had so choked up her window with thick-growing plants that the light which shone so brightly outside could hardly creep in through the leaves. And so poor Barbara was shutting out the sunshine of love from her home and her heart, and making them both dull and cheerless when they might have been so bright. Do you think that the proud, quarrelsome woman was happy? Ah, no, dear reader; for there never is true happiness with sin. It has been truly said that a little sin disturbs our peace more than a great deal of sorrow. Barbara was in her secret soul vexed at having quarrelled with her sister; she was vexed, but she would not own it, for her heart was full of pride. Barbara had resolved never to confess herself wrong, and rather to live all her life unloving and unloved than to bend her haughty spirit to make friends with her younger sister.

There sat unhappy Barbara, with no companion but bitter thoughts. She felt terribly alone in the world, but it was her own pride and temper that had made a desert around her. She could not help thinking of the happy days of childhood, when she and her sister had been merry playmates together. Barbara's eyes chanced to rest on a little olive-plant in her window; and the sight of that plant had brought back to her memory days of old. She recollected how Bice, then a rosy-cheeked child, had once asked her what shrub or tree she would choose for her own especial favourite.

"I would choose the laurel," had been Barbara's proud reply; "for that is the plant of which wreaths are made for those who conquer in war."

"I would choose the olive," little Bice had said; "for it was the leaf of the olive that was brought by the dove to Noah; and it always seems as if the plant, with its juicy fruit and silvery hue, made one think of gentle peace."

So from that day the olive had always been connected in the mind of Barbara with the thought of her gentle sister.

"I'll throw that plant away; I'll pull it up," muttered Barbara; "I don't care to keep anything now to remind me of her."

The proud woman had hardly uttered the words when a soft—a very soft—knock was heard at the door.

At Barbara's rough "Come in," the door slowly opened, and a little child appeared, so like to what Bice had been at her age that Barbara could almost fancy that she was looking again at her earliest playmate.

Rosina crept in timidly at first, for she thought that her aunt looked terribly stern.

"Why do you come here?" asked Barbara, with a little softening, however, in her tone.

"I have something to give you from mother," said the child.

"I will take nothing from her," replied Barbara; "I'll return it, whatever it be."

"Will you?" cried Rosina, suddenly running up to her aunt, and opening wide her little arms. The next moment the arms were clasped tightly round Barbara's neck, and the soft little lips were printing kisses on her cheek.

Barbara was a proud, ill-tempered woman, but she still had a heart, and a heart that might be conquered by love. She would have spurned a gift, but she could not refuse a kiss. Barbara could not help pressing her sister's child to her bosom, and a strange choking sensation appeared to rise in her throat.

"Those are mother's kisses—dear mother's kisses—and you promised to return whatever she sent," cried Rosina. "Give me the kisses back for my mother!"

And if Barbara did give the kisses, and if her proud eyes were moist as she did so, who can wonder? She would have mocked at words of reproach; she would have retorted insult or scorn; but the kiss, the fond kiss, sent through the little child, subdued both her anger and pride.

Barbara rose from her seat, and slowly walked to the window; perhaps it was partly to hide her eyes that she did so. She broke off a large branch from the olive, and suddenly turning round, held it out to her little niece.

"Take this to your mother from me, Rosina," she said, "and tell her to remember our early choice. The laurel, I have found, bears but a poisonous berry; the fruit of the olive is good—I will cultivate it from this day."

If Rosina did not fully understand the message, she understood the smile which followed it, which looked so pleasant on a face so lately furrowed with gloomy frowns.

And when Rosina, bearing the olive-branch in her little hand, ran out to her father, and told him all that had passed, his look of amusement and pleasure more than rewarded the child for the effort she had made.

"Brava, my brave little messenger!" exclaimed Carlo, giving Rosina a hearty kiss as he lifted her up to Duchessa's back. "Brava, little peacemaker! So you made her give back the kisses again! That bit of olive will bring as much joy to your mother's heart as if it were made of silver, with blossoms of pearl and leaves of gold."

Very joyful was the return of Rosina to her home. The fodder which Carlo procured from the farm, and heaped high on the patient Duchessa, looked like a little throne for the child, who, as she saw her mother standing at her door to welcome her, merrily waved her branch of olive, the token of joy and success.

Carlo planted the olive-twig in his garden, where it took root, and in time grew up to be a goodly tree with blossoms and fruit. Barbara, who was often a guest at her sister's cottage, watched the growth of the olive with peculiar interest; and Rosina always on her aunt's birth-day bore to her a little spray from the tree.

And when Rosina herself had grown up to be a woman, and married, and had little children of her own, their favourite spot for play was under the shadow of what was called "the peacemaker's tree."

Dear children, plant in the gardens of your own little hearts the olive-branch of peace.

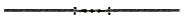

THE ASS IN THE LION'S SKIN.

AN ass finding the skin of a lion, put it on, and in the disguise of the king of beasts soon sent the more timid animals scampering in terror before her. The fox alone showed no fear.

"What!" brayed the ass. "Are you not frightened? Do you not dread the lion's terrible jaws?"

"Ah, my good friend," said the fox, "creatures at a distance may be alarmed at sight of the tawny hide of the lion, but I have come near enough to hear the bray and spy the long ears of the ass!"

THE ASS IN THE LION'S SKIN.

Those who try to inspire respect by false pretences are sure to betray themselves in the end.

————————

FALSE PRETENCES.

"You say that your father keeps a butler and footman, why that's nothing!" exclaimed Master Tom Talkaway in a pompous tone to one of the group of schoolfellows amongst whom he had come for the first time. "'My' father keeps six men and two boys," added the young boaster, looking round him with an air of triumph.

"I say!" exclaimed Jack, one of the boys whose mother could only afford to have one general servant.

"Oh, you should see how we go on in London!" cried Tom. "You've not a notion of real high life in a poor little village like this. Why," he continued in his swaggering way, sticking his thumbs into the pockets of his waistcoat, "I've seen five, six, seven carriages waiting before father's door, and the most of them had coronets on them."

"I say!" repeated poor Jack; while the other boys exchanged looks of surprise, scarcely knowing whether to believe their companion or not.

Mr. Gilbert, the usher, who had been sitting by the window reading, raised his eyes from his book.

"Tom Talkaway," he quietly said, "I happen to know about your father: he is a respectable haberdasher in London, and, for aught that I know, may keep six men in his shop and two boys to carry his parcels; nor should I be surprised if some of his customers came in carriages even with coronets on them."

Tom was thunderstruck at these words; his thumbs were pulled out of his pockets, he flushed up to the roots of his hair. There was a general roar of laughter from his schoolfellows, and cries of "Look at the great son and heir of the haberdasher!" which increased the boy's confusion.

"Hush!" cried the usher, raising his hand to command silence. "There is 'nothing' to be ashamed of in 'honest' trade, but 'a great deal' to be ashamed of in 'dishonest pretence.' And," he added, looking sternly at Tom, "it is only the 'ass' that puts on the skin of the lion, and he is sure soon to be found out, and to meet the scorn which he merits."

NEVER MIND SCOFFS.

"I'LL splash that duck all over! I'll make it as wet as a sponge in the water! I'll soon take out all the shine from its green and glittering neck!"

So cried little Guy, as with both hands he flung water at the beautiful bird. But calmly the duck swam on; its rich plumage was dry, not a drop would rest upon it, and bright as ever in the sunlight shone its green and glittering neck.

"I shall pelt it with water from my squirt!" cried Guy. "I shall certainly wet it at last, and make its feathers like those of the dead pigeon which I found yesterday in the brook!"

THE BOY AND THE DUCK.

Yet calmly the duck swam on; its rich plumage was dry, not a drop would rest upon it, and bright as ever in the sunlight shone its green and glittering neck.

Why was the duck never wet, though the boy in his malice threw so much water upon it? Because Nature has given it oil on its feathers that throws off the moisture at once. Even when the bird dives in the stream, it rises unwetted and unstained.

When we are pelted with scoffs and words of unkindness, let the "oil of patience" keep our temper unruffled, and then they have no more real power to harm us than water to injure a duck. There are those who laugh and mock at others for refusing to join them in evil: they pelt them with bitter jests, and try to throw shame upon them. Are not such acting the part of Guy? Let all who are laughed at for doing right go steadily on their way; shame cannot rest upon them, nor dim the brightness of a character that will shine but the more clearly for such vain attempts to blot it.

A PEEP INTO A BACK-KITCHEN.

"WHAT can a little boy of seven years of age do?" I would ask of my young readers. Perhaps they will answer, "He can read, perhaps write in a very big round hand; he can bowl a hoop, toss a ball, spin a top, and fly a kite."

"But can such a child be of any 'real use' in the world?"

Let me answer this question by giving a truthful account of a visit which I paid a few days ago to a family in one of the poorer streets of London.

My ring at the door of a lodging-house for the poor was answered by little Ben, a boy of about seven years of age. The sound of a baby's cry was heard from the back-kitchen, from which he had just come, and which was the dwelling-place of the family.

No wonder was it that the poor baby cried, for I found, on descending the pitch-dark staircase, that Ben was the sole nurse for the time of the sickly infant. That scene in the dark dull kitchen was a strange picture of life amongst the poor. There was Ben, after he had followed me down-stairs, hushing the baby in his little arms, and soon succeeding in quieting it, for he was evidently an experienced and skilful nurse. There were two other children under his care—Polly, about four years old, and Annie, not two. One might almost have said that Ben had "three" babies to look after, but I soon found that Polly was already to be reckoned as his little assistant.

Annie began to cry; Polly went up to her sister, put her hands on either side of her face, and tried, as well as she could, to soothe her. Annie, however, cried still. Ben said a word or two to Polly, and the little nursemaid, "four years of age," hastened to get a cup, into which she poured water from a jar which stood on the ground, and she then brought the drink to her thirsty little sister. The boy had guessed the cause of the crying, and Polly having thus removed it, we had again quietness in the back-kitchen.

Ben, a very intelligent little fellow, entered freely into conversation with me, while he nursed the baby in his arms. That boy had been in sole charge of the three children for two hours, while his poor half-blind mother was out, procuring necessaries for the family.

"Are you happy?" I inquired. The question seemed a strange one to be asked in so gloomy an abode.

"Yes, I'm happy," replied the boy, with an honest smile on his face.

What a lesson for many a pampered, peevish child, grumbling and discontented in a comfortable home!

"Does Polly ever go out?" I inquired, for the low dark room looked something like a prison.

"Yes; I sometimes take her out."

"And does Annie go out?"

BEN NURSING THE BABY.

"Yes, when Polly goes, she goes; I take them in the 'chay.'"

This "chay" was twice mentioned by Ben, which rather surprised me, for I certainly did not suspect that the family kept a carriage. My attention was, however, directed at last to a substantial-looking perambulator, which in the dim light I had not noticed before.

"Father made that," said Ben.

This was almost too much for me to believe. I questioned the boy closely, but he was sure of the fact. I found afterwards, from the mother's account, that the father had bought the wheels and other iron parts, the wreck of a former perambulator, for "ninepence," as they were to be sold as old iron. He had actually made all the rest of the carriage for his little ones, stuffing the cushion with hay. It was a striking proof of the father's ingenuity, that labour of love!

B— must be a very industrious man. He goes to the docks in hope of getting a day's job there, and then, after his return, "cleans his potatoes," as little Ben told me; for when the labours of the day are over, B— is glad to go out at night to sell baked potatoes, that he may thus help by double work to support his almost blind wife, and four little children.

"What do you get for breakfast, Ben?" I asked.

"Bread and butter—no," said the child, correcting himself; "father gets bread and butter, I get bread and drippings. But 'I like the drippings best,'" he added, with a nice feeling which pleased me.

The poor mother soon came in, half exhausted from wandering about for two hours, for in her blindness she could hardly find her way. She was, however, calm and contented.

When I asked her what message she had for a lady who had sent her a present by me, "Tell her that I am in better circumstances," was the pale, thin woman's reply.

As her husband had succeeded in getting four and a half days' work that week, Mrs. B— seemed to feel that she had nothing to complain of. Her greatest trouble was the illness of her babe, as she feared that the little one might die. Very thin and wasted the poor infant looked, but the other three children appeared plump and well-fed. Mrs. B— must be an excellent manager, notwithstanding her blindness, and it is clear that her husband's earnings do not go to the ale-house.

I have reason to hope that she is a God-fearing woman, and that she and her husband pray as well as labour. Ben is to attend the Sunday school. He would go to the weekday school also, which he used to enjoy attending, but so useful a child cannot be spared from his home.

I left that dark back-kitchen with a feeling rather of respect than of pity. Little Ben, brought up in the midst of poverty, with three young children to care for, and an almost blind mother to help, may lead a life of happiness, as he certainly does of usefulness, with hope before him, and love around, and the blessing of God upon him!

THE TWO PATIENTS.

NAY, little Tommy, do not shrink away, as if I meant to do you harm. If a thorn has been left in your finger for days, and if the poor finger is swelled and sore, and cannot get well till the thorn is out, is it wise to cry, and pull back your hand, and not let your mother look at the place? There, hold it out now, like a brave little man; and while I am doing all that I can to relieve you, I'll tell you a tale of a poor dog that was much more hurt than you are.

A doctor found in the street a poor spaniel that had broken one of its legs. The man had a kindly heart, so he took the dog to his home, set its bone, put splinters round it, and wrapped it up in bandages, in hopes that the leg might be healed. I do not think that the spaniel struggled and howled as you did two minutes ago, though the doctor, kind as he was, must have given a good deal of pain.

There, Tommy, the thorn is out; you can see it on the point of my needle, and like a good brave boy you never uttered a cry when you felt the prick. Now, while I bathe and bandage the finger, I will tell you more of the dog.

The spaniel's leg grew quite strong and well. The doctor sent the dog home, as he knew to whom he belonged. But he had not seen the last of his patient.

Some time afterwards the doctor heard a whining and scraping at his door, and when he opened it, who should be there but his old friend the spaniel, and with him a poor lame dog that could hardly limp along. The spaniel jumped and wagged his tail, rubbed his nose against the doctor, and looked up in his face, asking him, as plainly as dog could ask, to do the same kind office for his friend as he had done for himself.

THE SECOND PATIENT.

The doctor could not resist the sensible creature's appeal. He bound up the leg of the second dog both with kindness and skill, and the poor creature, much relieved, limped slowly away with the friend who had so wisely brought him to the place where he himself had found a cure.

Now your finger is bandaged up, Tommy. I have played the doctor's part, and hope in a few days to see that all is as well as ever. And if Mary or Lucy, when gathering blackberries in the wood, manage to run a thorn into a poor little finger, do not let her wait till it fester and swell like your own, but play the part of the wise little dog, and bring her here to the doctor at once.

IT'S VERY HARD.

"IT'S very hard to have nothing to eat but porridge, when others have every sort of dainty," muttered Charlie, as he sat with his wooden bowl before him. "It's very hard to have to get up so early on these bitter cold mornings, and work hard all day, when others can enjoy themselves without an hour of labour. It's very hard to have to trudge along through the snow while others roll about in their coaches."

"It's a great blessing," said his grandmother, as she sat at her knitting—"it's a great blessing to have food, when so many are hungry; to have a roof over one's head, when so many are homeless. It's a great blessing to have sight, and hearing, and strength for daily labour, when so many are blind, deaf, or suffering."

CHARLES AND HIS GRANDMOTHER.

"Why, grandmother, you seem to think that nothing is hard," said the boy, still in a grumbling tone.

"No, Charlie. There is one thing that I think very hard."

"What's that?" cried Charlie, who thought that at last his grandmother had found some cause for complaint.

"Why, boy, I think 'that heart is very hard' that is not thankful for so many blessings."

THE PIC-NIC.

"WHAT a delightful morning for a ride!" exclaimed Mina, as she patted the pretty black pony which her brother Felix was about to saddle for her. "I almost wish that the place fixed on for the pic-nic were three times as far away, that I might have a longer gallop over the common, gay with golden furze, and along the green shady lanes."

"You forget," said Felix with a smile, "that if you have to ride, we have to walk; and that two miles each way is enough to give us an appetite for the chicken-pie and cold tongue which are stowed away in the basket."

BEFORE THE PIC-NIC.

"This is just the day for a pic-nic!" cried Mina. "I am sure that we shall enjoy ourselves much in the wood. There is only one thing that may damp our pleasure," she added; "I almost wish that mamma had not invited Priscilla Grey, and yet it is unkind to say so. It would have been hard on the poor girl to have left her behind."

"She's as ill-tempered a wasp as ever I met with!" cried Felix. "And it seems as if she had an especial spite against you, for no reason that I can think of, except that our parents being richer than hers, you ride on Frisky, while she has to go upon foot."

"I have never willingly done anything to vex her," said Mina.

"You would never vex any creature living!" exclaimed Felix, who was very fond of his sister. "But Priscilla is always on the lookout for some cause of offence, and those who do so can always manage to find one. If you only heard how she was speaking of you the other day! It made me so angry, that if she had not been a girl, I think that I really should have struck her. She said—"

"I don't want to hear what she said, dear Felix," observed Mina, who was a peace-loving girl.

"But I've a bit of good news to give you. Priscilla, after all, will not be at the pic-nic to-day. She slipped her foot yesterday going down-stairs, and has sprained her ankle—not badly enough to lay her up, but enough to make it quite out of the question for her to walk four miles."

It must be owned that Mina's first feeling was one of relief at being rid of the company of so disagreeable a girl. But at that moment the sun, which had been hiding behind a cloud, darted out his glorious beams, lighting up the landscape around, smiling on the weedy waste as well as the beautiful garden. Those rays brought to the mind of Mina part of a verse from the Bible, "'He maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good.'"

Mina remembered what she should do as one of the children of Him who bade us love our enemies, and do good to them that hate us.

"Felix," said the gentle girl, "if Priscilla cannot walk, she can ride."

"Of course, if she has anything to ride upon better than a dog or a cat!" laughed Felix.

"I could lend her my pretty Frisky, and walk with you to the wood."

Felix gave a loud whistle of surprise. "Lend her your pony, and lose your ride! How can you dream of doing such a thing!"

"Indeed, Felix, I feel that I must do it. As you have kindly saddled Frisky, we will go together—it is but a step—and lead him to the door of Priscilla."

"Well, you are wondrously kind," cried Felix. "I could understand your giving up your ride for a sister, or a friend, but to think of your doing so for the sake of such a girl as Priscilla!"

"It is not just for her sake," said Mina; and she thought to herself, it is for the sake of Him who is kind to the unthankful and to the evil.

With a little difficulty, Mina persuaded her brother to yield to her wishes, and they led the black pony to the door of the small house in which Priscilla lived with her mother. Priscilla, who was in worse temper than usual, from being disappointed of her expected treat, caught sight of them through the window.

"Ah, there's that girl Mina!" she exclaimed, with a burst of spiteful passion. "She's bringing that ugly beast that she is so proud of, just to let me see how much better off she is than I am. I wish that it would rain. I wish that a thunderstorm would come and spoil the fun of the pic-nic."

But very different were Priscilla's feelings when Mina ran into the room, inquired kindly after her ankle, and then offered to lend her Frisky that she might ride to the wood. Shame and something like gratitude mingled with pleasure and surprise, and Priscilla owned to herself, what she never had owned before, that it was not only in worldly wealth that Mina was richer than she.

No rain fell, no thunderstorm came to spoil the pleasure of the pic-nic. There were few clouds in the sky, and none over the spirit of Mina. She enjoyed her walk, she enjoyed her feast, she enjoyed seeing and adding to the pleasure of all; but her richest enjoyment came from the whisper of an approving conscience, that she had not been overcome of evil, but had overcome evil with good.

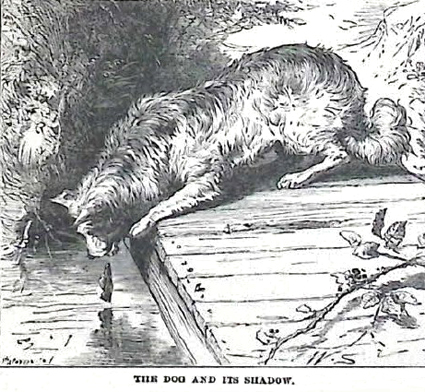

CATCHING AT A SHADOW.

"OH, Alice dear, won't it be fine fun to drive into London and spend the day with grandmamma to-morrow!" cried little Minnie Davis to her sister.

"I hope that you may find it so," was Alice's reply. "As for me, I will not be with you."

"Not go to London!" exclaimed her brother Charlie, looking up in surprise from his book.

"No; I hope to go somewhere further than to London, and have better fun still. What say you to the Crystal Palace?" asked Alice, with a beaming smile.

"You don't mean to say that the Brownes have asked you to drive down there in their carriage to-morrow?" said Charlie eagerly.

"Well, no, not exactly 'asked' me, but I think that they will call for me on the way. Indeed I'm almost sure of it, for when Lizzie told me that they were all going, she smiled and squeezed my hand, just as much as to say, 'I hope you'll be one of the party.'"

"Oh, if you've nothing better to go upon than a smile and a squeeze of the hand," laughed Charlie, "I should advise you to come with us to grandmamma, and not give up a certain pleasure for one so very uncertain!"

"But I 'have' something more to go upon," said Alice, who was not pleased at her brother's laugh. "Mrs. Browne knows that I have never been to the Crystal Palace, and that I long above all things to see it; and a month ago she said to me, 'We must take you there with us some day.'"

Charlie smiled and shook his head. "Alice," said he, "don't you be like the dog in the fable, that when crossing a brook with a bone in his mouth, saw his own reflection in the stream, and was so eager to snatch at what he thought another bone in the jaws of another dog that in the attempt to get it, he dropped his own bone into the water."

THE DOG AND ITS SHADOW.

Alice was a little out of humour at being compared to so foolish a dog, and coldly replied, "If I choose to take my chance of a treat, I don't see that it matters to you."

"Oh, but, Alice dear," said gentle little Minnie, "won't grandmamma be disappointed not to see you, and wouldn't papa like to have you with him, and wouldn't it be such a pleasure for us all to drive up together?"

Minnie was a loving, coaxing little girl, and Alice was very fond of her. Besides, there was reason in what she said, so that it was in a hesitating tone that her sister replied,—

"I don't think—at least I hope that dear grandmamma won't much mind my staying away just this once; I daresay that I'll have another opportunity of seeing her before the winter sets in. You will take her my love, and tell her that nothing but a visit to the Crystal Palace—" ("The 'shadow' of a visit," interrupted Charlie)—"would prevent my enjoying the pleasure of going to her," continued Alice, without appearing to notice the interruption. "As for papa, I have his leave to remain behind if I wish it, and he has allowed me to go with the Brownes."

"That is to say, if they wish to have you," laughed Charlie; "remember the dog and the bone, Alice, remember the dog!"

The morning came, sunshiny and bright: all breakfast-time the children were talking of the coming pleasures of the day. The chaise drove up to the door. Charlie and Minnie were eager to start for London, the only damp on their enjoyment being that their sister was not going with them.

"Oh, Alice darling, do come!" pleaded Minnie. "We shall miss you so sadly, and so will grandmamma: we should all be so happy together!"

"We'll be happy together this evening, dear, when I tell you about all the wonderful things that I shall have seen—the stuffed beasts and the living birds, the huge tree, and the splendid Alhambra court."

"Alice, my girl, I hope that we are to have you with us," said Mr. Davis, coming out of his room with his driving-whip in his hand.

"Dear papa—if you don't mind—I think I'd rather stop behind just this once."

"Well, do as you please," said the father.

But Alice thought that she saw a little shade of displeasure on his face, and she felt much inclined to run after him, and beg to be taken with him in the chaise.

"Alice is changing her mind!" cried Charlie.

It was an unfortunate observation; Alice was foolish enough to pride herself upon never changing her mind, even when she had made a mistake, and she did not choose that Charlie should be able to laugh at her for so doing. She therefore stayed within the gate of her father's pretty little garden at Hampstead, bade good-bye to the party, and saw them drive off towards London.

Alice could not help a feeling of misgiving as the chaise rattled away down the road, but she turned from the gate with the remark, "They will have a pleasant visit, I hope, but nothing to be compared to my treat. I will run and put on my best hat and my new kid gloves, and be all ready to start; for the Brownes are likely to set off at ten, and I wouldn't keep them waiting—no, not for one minute."

But if Alice would not keep the Brownes waiting, it was out of her power to prevent being kept waiting herself. Very impatient she grew as she watched by the gate, counting up to a hundred again and again, to make time appear to pass less slowly.

"Dear me! What can be delaying them so long? What if they should not be going to the Crystal Palace after all—if I should have to stay here the whole day all alone, after disappointing Minnie, and running the risk of vexing dear kind grandmamma, who always gives such an affectionate welcome? There's the sound of wheels—they're coming at last! Oh no, it is only the butcher's cart! What a dust it stirs up! And here comes the great lumbering omnibus."

Alice drew back a little from the gate, to be out of the way of the dust. The omnibus was crowded with passengers within and without—it seemed to Alice as if all the world were going pleasuring except herself, and it was her own fault that she was not at that moment driving through London. Had she been less selfish and self-willed, she would have given up for the sake of others her chance of the much-desired treat.

Scarcely had Alice returned to her post close behind the gate, when she uttered an exclamation of joy, clapped her hands, and could hardly refrain from jumping.

"Oh! Here they are coming at last—I know the blue liveries and the spanking gray horses. There is Mrs. Browne's green bonnet, and there is Lizzie leaning out from the carriage; she sees me—she is smiling—she is kissing her hand—and—"

Poor Alice stopped short in the middle of her joyful sentence, for, alas! the carriage did not stop, the spanking grays did not slacken their pace as they dashed along the road in front of the gate! The smile of eager delight on the face of the poor child changed to a look of blank dismay when the carriage had actually passed, and no one had called to the coachman to pull up, and Lizzie and her party had actually disappeared from view, hastening on their way to the Crystal Palace!

When carriage, blue liveries, and all, could be no more seen, and even the rumble of the wheels could be heard no longer, Alice burst out crying. She could not help it, so bitter was her disappointment, so great her regret at her own folly. She ran into the house, threw herself down on a sofa, and sobbed. She had dropped the pleasure which she might have enjoyed, trying, like the dog, to snatch at another; she had disregarded advice, she had acted a selfish as well as a foolish part, and now all her delightful hopes had ended in disappointment!

Alice cried violently, but she did not cry long. Presently she lifted her head, dried her wet eyes, and began to try to bear her misfortune more bravely.

"This has been a sad lesson for me," said Alice to herself with a sigh. "I should not have minded the disappointment so much if it had been through no fault of my own. What a miserably dull day I shall spend! Papa and the children will not be back till the evening,—I have nothing to amuse me, or take up my thoughts. Oh, that I had gone up to London!"

But Alice was, after all, too sensible a child to give herself up for hours to vain regrets. "What can't be cured must be endured." She had made one mistake which could not be repaired, but to have remained all the day long in dull idleness, fretting over her disappointment, would have been to make another.

"I had better occupy myself about something," thought Alice, rising up from the sofa. "Charlie's garden wants weeding, it is half covered with groundsel and chickweed; shall I give him a surprise by clearing it all nicely before he comes back? Dear little Minnie has her stockings to mend, and I know that she finds darning so difficult; shall I save her the trouble by doing the work myself? Papa asked me yesterday to put his papers in order; here is leisure time in which I can arrange everything as he likes. If I cannot be happy to-day, I may at least be useful: I'll weed, I'll work, I'll sort the papers, and so pass the wearisome hours!"

Alice had this time made a wise resolution, and she found that while her little fingers were so busy, her mind had less time to dwell upon the sad disappointment of the morning. She had almost regained her cheerfulness at last, before she heard the sound of the returning chaise, and ran out to meet the party from London at the gate of the garden.

"Well, Alice, where have you been?" cried Charlie, as he jumped down from the chaise.

"What have you seen?" asked Minnie eagerly, as she followed her brother.

Alice tried to give a good-humoured smile as she made reply—"When you go to your garden, Charlie, and you to your workbasket, Minnie, you will easily find out where I have 'been.' And as for what I have 'seen,' I have seen that it is best to be contented with pleasures within our reach, and that he was a foolish dog indeed that dropped his bone to catch at a shadow!"

GO AND DO LIKEWISE.

"MAKE haste, make haste, or I do believe that the train will be off!" exclaimed Arthur, hurrying with his two brothers along the highroad, towards a small station at which the train was to call at ten.

"I really can hardly keep up with you, Arthur," said Peter. "You rush on like a steam-engine yourself."

"If any of us had only a watch to tell us the exact time. But the train comes so fast, and gives so little notice; and only think, if we were to miss it!"

"What a splendid day we have for our trip!" cried Mark. "Not a cloud to be seen in the sky! I do long to see the Crystal Palace. They say that it is the most beautiful thing in the world!"

"How kind it is in uncle to give us such a treat!" said Arthur, his rosy face beaming with pleasure. "We have never had such a holiday before. Oh, let's make haste—come on, come on!"

"What's that sound?" exclaimed Mark, stopping short.

"Not the railway whistle, I hope," cried Arthur.

"It's a loud cry of distress from the end of that field," said Peter, looking alarmed.

"There it is again," cried Arthur. "Some one is in terror or in pain."

"I daresay," said Mark impatiently; "but you know we've no time for delay."

"I suspect that it is some one hurt by the bull that is kept in that field," cried Peter. "I can see the creature through the hedge."

"Can you see any human being?" said Arthur.

"No, no one; but the voice shows where the person must be."

"We cannot wait any longer," said Mark. "Remember that if we are late for this train we must give up the treat altogether."

"I cannot bear to go with those shrieks in my ears," replied Arthur.

"Then I will go on without you," said Mark. And he ran on, as if to make up for lost time.

"Peter, we should get over that stile, and go to see what is the matter," said Arthur.

"Perhaps we ought; but—but you know that there is the bull in the field."

"He is a very quiet one."

"Yes, generally; but he may be in a savage mood now. I feel sure," added the boy, grasping his brother's arm, "that he must have gored the poor child whose screams we hear."

Arthur looked grave and anxious. His brother was older than he, and Arthur had been accustomed to lean upon his opinion.

"Will you go, Peter?" he said, at last.

"Not I—it would be folly—we will send some one from the station."

"Ah, if they would attend to us boys; and even if they would, help might not arrive for half an hour, and then it might come too late. O Peter, that is a terrible cry."

"I can't bear to stay and hear it!" exclaimed Peter. And so saying, he turned and ran along the road as fast as Mark had done before him.

And did Arthur follow his brothers? No, he did not. He went back to the stile, hastily clambered over it, and with many an uneasy glance at the bull, that was cropping the grass at no great distance—fearful of running, lest it should draw him after him—Arthur made his way to the spot whence the cries proceeded.

Was Arthur less eager than the other boys to enjoy his treat? Was he less afraid of being gored by a bull? By no means, for Arthur was the youngest of the three. He had hardly slept the night before from thought of the coming pleasure, and he was by no means particularly courageous by nature. Why, then, did he turn back and cross the field? It was that the love of God was shed abroad in his heart that he had learned in the Bible to forget self, and that he sought every opportunity, by kindness and compassion to his fellow-creatures, to show his love and gratitude to his heavenly Master.

Resolute, therefore, neither to let fear nor pleasure stop him in the course of duty, Arthur proceeded on his way, though I cannot say that his ears were not anxiously listening for the sound of the railway whistle, or that he did not often fearfully turn to see if the bull were running after him. He neither heard the whistle, however, nor was pursued by the bull, but reached in safety the other end of the field, where he found, lying in a dry ditch, just beneath the hedge, a poor girl of about his own age.

"What is the matter with you?" said Arthur, stooping to help her to rise. "I am afraid that you are very much hurt."

The girl was crying so violently that it was some time before Arthur could make out the cause of her distress. It appeared that she had fallen in getting over the hedge, and had sprained her ankle so severely as to be unable to rise.

"I thought that no one would ever come," sobbed the girl, "though I screamed as loud as I could."

HELP IN NEED.

"But what can I do for you?" said Arthur. "I am not strong enough to carry you away."

"Oh, do you see that little white cottage there, just on the side of the hill? My father lives there. If you would only go and tell him, I am sure that he would come and help me."

"If I go all that distance," thought poor Arthur, "I shall be quite certain to miss the train."

But he looked again at the suffering girl, and thought of the holy history of one who had compassion on a poor injured traveller. He remembered the words, "Go, and do thou likewise"; and determined to give up his own pleasure for the comfort of another. Perhaps only a child can tell how great was the sacrifice to the child!

Arthur ran in the direction of the cottage, arrived there breathless and heated, and found the girl's father standing at his door talking to a baker, who, in his light cart, was going his daily round. A few words from the panting boy explained to the man the accident that had happened to his daughter.

"I am much obliged to you," said the cottager. "I will go to poor Joan directly."

The eye of Arthur fell upon the Dutch clock hanging up near the fireplace. The hour was not quite so late as his fears had imagined, but still it wanted only eight minutes to ten.

"I cannot be in time for the train," said the tired boy sadly, half to himself. "My brothers will be off without me."

"Did you want to meet the train? And have you been delayed by your kindness?" said the baker, leaning from his cart, with a look of interest. "Jump up here beside me. You've a chance of it yet. The train may not be punctual to a minute, and Dobbin trots as fast as any horse in the county."

In a moment the eager boy was up in the cart, and the baker seemed as eager. You might have thought, too, that the horse knew the state of the case, he dashed on at such a fine rate! And the train was five minutes beyond its time. Not till Arthur had sprung down from the cart at the station, and stood thanking the kind baker who had helped him in his need, was the long shrill scream of the whistle heard, and the dark rattling line of carriages appeared. He was in time! Oh yes, he was in time!

Mark and Peter enjoyed their visit to the Crystal Palace, but their pleasure was as nothing compared to that of Arthur. His whole soul was overflowing with pure delight. He felt inclined to go springing and bounding along, his heart was so free from a care! As a good man once said, "How pleasant it is when the bird in the bosom sings sweetly."

If my reader would know what is real happiness, real delight, let him seek it in forgetting self, and following the steps of his Lord. Where there is sorrow which you can cheer, or distress which you can relieve, remember the Samaritan who beheld a wounded stranger and would not pass by on the other side. Do not turn a deaf ear to the voice of pity, but oh, Christian child! "Go and do likewise!"

THE BEST FRIEND.

"HA! Carl Von Orlich; well met!" exclaimed the veteran Strasse, as, on the night after one of the fiercest fights in the Seven Years' War, he suddenly came upon his comrade, and recognized his features by the red light of the watch-fire, over which he was bending.

Von Orlich started up, and wrung the hand of his friend.

"I little thought a few hours since," said he, "to see you or any other man in the land of the living."

"You have much cause to thank Him who has covered your head in the day of battle," observed Strasse, who was one who, in a godless age, did not shrink from openly confessing his faith, and by so doing had drawn upon himself many a scoff, some even from his friend Von Orlich.

"It was hot work," said the officer, wiping his brow.

"When I saw you from a distance dash into the midst of what seemed a circle of smoke and fire, through which one could scarcely catch a glimpse of the flashing swords, I never expected, Von Orlich, to see you come forth alive."

"It was to rescue him—the gallant Helden," said Von Orlich. "I saw him sorely beset; and if I had had a thousand lives, I'd have ventured them all for his sake. I bore him safe out of it all," added the officer, with a proud smile of triumph on his lip.

"Helden is a man who deserves a friend," observed Strasse.

"He does—better than any other man in Prussia!" exclaimed Von Orlich. "Did you never hear what he did when he was a gay young page in the service of our last king, Frederick William?"

THE TWO COMRADES.

"Not I," replied Strasse, seating himself; for he was weary with the struggle of the day, and glad to warm himself for awhile beside the red glowing fagots. "Tell me the tale of his youth. It may serve to while away a few weary minutes; for as my turn for duty will soon come, it is not worth while to lie down and sleep."

"Helden, like most of our Prussian youth of gentle blood, was brought up at a military academy. There he formed a warm friendship with a lad of somewhat lower rank and much poorer family than his own. They were never separated, Carl and he—studies, sports, hopes, pleasures, everything they had in common. Never did brothers cling more closely together than they. When the youths left the academy, their paths divided. Helden, who had relatives of rank, became a page at the court of the king; Carl, who had neither money nor interest, entered the ranks of the army. But the tie was not broken between them, as with most men it would have been. The page, midst the splendours of a court, remained true to the friendship of his boyhood.

"Carl was of a somewhat wild and reckless nature. Perhaps it stung his pride to find himself in a position so much below that of his late companions. Be that as it may, he had not been a month in the army before he got into serious disgrace—overstayed leave, was out of barracks till midnight, and was sentenced to receive a public flogging. You know, Strasse, with what terrible severity that punishment is inflicted in the army. To many it is equal to a sentence of death—to Carl it was far worse than death! The agony might be great, but it was the shame that was intolerable! The very horror of the idea of a public flogging threw the young soldier into a fever, and threatened to turn his brain."

"I do not marvel at that," observed Strasse, as he stretched his hands to the warming blaze.

"Helden heard of the sentence passed upon his friend, and resolved to make every effort to save him. He drew out a simple but touching petition to the king, and ventured himself to present it—a task requiring some courage, for you know the character of Frederick William, and his excessive severity in whatever related to the discipline of his army."

"It was something like presenting a petition to a lion to spare the prey under his paw," observed Strasse, with a smile.

"And the king received it much as the lion might have done," rejoined Von Orlich. "He was roused to one of his storms of fury, tore the petition in pieces, and Helden was fortunate enough to escape with nothing worse than a torrent of abuse."

"So Carl underwent his sentence, of course?" asked Strasse.

"Hear to the end," replied his comrade. "Any one but Helden would have given up in despair all further attempt to rescue his friend, but, true as steel as he was, he resolved to make yet another. Helden drew out a second petition; and on the night before the morning on which the flogging was to take place, he went to the antechamber with it in his pocket, with the intention of presenting it to the monarch."

"He was a bold youth," remarked Strasse. "When we recall how nearly our late king put to death his own son and heir for a very trifling cause, one cannot but marvel at the perseverance of Helden."

"The king," continued Von Orlich, "was engaged, till far into the night, in secret conference with one of his ministers. Helden, full of deep anxiety, remained in the ante-room waiting. So long had he to wait, so weary he grew, less perhaps from the lateness of the hour than the wear upon his own spirits, that sleep overcame the poor youth. The king, happening to come out of his cabinet, found his page in deep slumber in an arm-chair, with what looked like a second petition sticking half out of his pocket.

"'If that audacious young scapegrace dare to pester me again with his petitions, he shall get something sharper than words.' Such, I suspect, was his majesty's thought when, without awakening the page, curiosity made him draw forth the scroll. Perhaps, however, his countenance changed when his eye glanced over the strange petition which it contained. It was very brief, but to the purpose; and was, as well as I can remember, in these words: 'Sire, if the sentence passed on Carl must be executed, I entreat your majesty's permission to suffer instead of my friend.'"

THE KING TAKING THE PETITION.

"A strange petition, indeed," exclaimed Strasse. "What said the king to the offer?"

"Stern and rigid as he was," replied Von Orlich, "such generous friendship, such brave self-devotion, could not but touch his heart. I know not how long Helden slumbered. He was startled from his sleep by the sound of the bell rung by the king in his cabinet.

"'Now for the effort!' thought Helden, as he sprang forward with a beating heart to obey the desired and yet dreaded summons.

"He found the king sitting alone, looking more than usually stern. Helden received some trifling order from the monarch, who then motioned to him to retire.

"'Now, or never!' said Helden to himself. 'The day will soon dawn, and at sunrise poor Carl is to suffer.'

"'Why do you delay?' asked the king very harshly, fixing his freezing gaze on the page.

"'Sire, pardon!' exclaimed Helden, and bending his knee, he drew forth a scroll, and presented it to his sovereign.

"'Will you stand by the consequences?' demanded the king, without touching the paper.

"'I will, sire,' replied the generous friend.

"'Read the contents, then, young man!' said the king.

"Helden opened the scroll, and started to his feet with an exclamation of joyful surprise. The paper contained, not his own generous offer, but a full free pardon for his friend, drawn out and signed by the monarch himself!"

"God had touched the king's heart," observed Strasse.

"Be that as it may," said Von Orlich, "Carl was saved from a punishment which would have driven him mad. And he lived to pay back this day part of the debt of gratitude which he owed to the best of friends!"

"What!" exclaimed Strasse in surprise. "You yourself are the Carl of whom you speak?"

"Ay; I have struggled upwards in life, won honours—" a star was glittering on his breast—"I have gained the wealth and position which are the prizes held out by war. But were the king to make me a duke," continued Von Orlich with emotion, "the pleasure and the honour would be small compared to what I felt to-day in proving my gratitude to the man who once offered to suffer in my stead!"

"It is strange," observed Strasse with a thoughtful sigh, as he looked into the flickering fire, "how apt we are to reserve all our gratitude for our fellow-man, forgetful of the Friend who not only offered to suffer, but actually did suffer in our stead! You braved fire and sword for one who had loved and saved you; shall our love be cold, and our courage faint, only when our debt is infinite, and our benefactor divine?"

Von Orlich made no reply; but as he silently gazed up into the blue starry heavens, almost for the first time in his life, the heart of the war-worn veteran rose in thanksgiving to God!

THE THICKET OF FURZE.

"WHAT a plague lessons are?" exclaimed Rosey, with a long weary yawn, as she bent over her French exercises, wishing from her heart that grammar had never been invented.

"Work on, little one!" said her brother George, who had overheard the exclamation. "Remember that it is doubly your duty to be steady and industrious while mamma is away."

"It is so difficult!" sighed the child.

"Many a duty is difficult," answered the elder brother, "but that is no reason for shirking it. Attending to little duties while we are young helps us to perform great ones when we are old. Do your lessons bravely, dear Rosey, and if they be finished by twelve, you shall have a little story to reward your diligence."

The word "story" called up a dimple upon Rosey's round cheek. She turned with more resolution to her tiresome lesson, and the task was ended by twelve.

"Now for my story," cried the child, bringing her little chair close to her brother, and resting her arm on his knee, as—looking up gaily into his face—she claimed the fulfilment of his promise.

George looked into the fire for a few moments, as if to draw some ideas from the cheerful blaze, stirred it, and then leaning back on his chair, began the following little tale:—

"Methought I lay down and slept, and dreamed; and in my dream I beheld a path through a verdant meadow, along which many a child gaily tripped, gathering the lovely wild flowers that grew on either side. But at one end of the meadow the path was crossed by a thicket of sharp prickly furze, and the name of the thicket was Difficulty. The bushes grew so thick and close, that I wondered whether any child would be able to pass them; and I sat me down to watch how the little travellers would get through the Difficulty in their way."

"I suppose that I was one of the little travellers," laughed Rosey, "and the furze-bushes were my horrid French verbs!"

"There are a great many 'Difficulties' in a child's life," replied George with a smile: "some find it difficult to rise early, some to be punctual or neat, some to control their tempers, others to be generous and kind. There are plenty of furze-bushes in our path, but we must not, like lazy cowards, suffer them to stop us in our onward course."

"Please tell me about the children in your dream," said Rosey.

"The first who reached the thicket was a little girl, with ruddy cheek and curly hair, who had been one of the gayest of the gay, as she went dancing through the flowery mead. But as soon as she came to Difficulty, all the cheerfulness fled from her face, she shrank from the first touch of the prickles as if she had expected that life was to be all sunshine and flowers, and sitting down on the grass by the side of the path, she burst into a flood of tears."

"Oh, the cowardly little creature!" cried Rosey.

"Then there came up to the spot a young boy, whose appearance to me was not pleasing. He never looked straight before him, but had a kind of cunning side glance, which made me fancy him less open and frank than a Christian boy ought to be. He made no attempt to push through the thicket, but went creeping along the edge of it, hoping to 'creep round' Difficulty instead of passing straight onwards. I watched him to see if he would succeed in his aim, but he had not gone many steps before his feet stuck fast in a bog, and it was only by violent and painful efforts that he could struggle out again, to return to the point whence he had started, with his shoes all clogged with clay, his time lost, and his object not gained."

"I suppose that he was a lazy boy," remarked Rosey; "putting off does not help us over our difficulties. I have sometimes tried that plan of creeping round, and I always stuck in the bog!"

"Then," pursued George, "a boy with firm step and resolute air came up to the thicket. I saw something like a smile on his face as he looked at the Difficulty before him. He set his teeth hard together, clenched his hands, and then with bold determination made a dash at the thicket. On he went, that stout-hearted lad, dashing aside the prickles, pushing forward as if he scarcely felt the scratches upon his bleeding hands. Trampling down, struggling through Difficulty, he was soon safe and triumphant on the opposite side!"

Little Rosey clapped her hands. "He was a fine fellow!" cried she. "I think that Nelson and Wellington went dashing through difficulties like that. But I can't do so," added the child more gravely; "I have not that bold, strong spirit. I am afraid that I am most like the little cowardly girl who cried when she saw the thicket."

"Is not that because you do not look upon your childish troubles as a means of testing your patience and obedience; is it not because you do not seek for help from above, even in the little trials of your life?"

"They seem such trifles to look at in that way," said Rosey, gazing thoughtfully into the fire.

"A writer has said that 'trifles form the sum of human things;' and the life of a child, more especially, is made up of what we call trifles. Yet children, as well as those who are old, are required to glorify God; and as they can do no 'great' thing for him, it is by their cheerful obedience, diligence, and sweet temper, that they must show their gratitude and love. And does not this thought, dear Rosey, make the performance of simple daily duties a bright and a holy thing? If what we do, we do as 'unto the Lord,' feeling that His eye is upon us, and seeking in all things to please Him, we find pleasure even in irksome tasks, sweetness in what otherwise would be bitter."

Rosey looked as if she scarcely understood the words of her brother, so, to make their meaning clearer, George went on with his tale:—

"There was one other child whom I saw in my dream advancing towards the thicket Difficulty. I felt sorry for the little girl, for she was feeble and pale, and as she moved over the grass, I saw that she was both lame and barefoot!

"'Alas!' thought I. 'If she can scarcely make her way along the smooth and pleasant path, how will she ever struggle through the prickly furze before her!'"

THE LAME GIRL.

"Perhaps the same thought was in the mind of the little traveller, for she paused before the thicket, and looked forwards with a scared and troubled air. Then she clasped her hands, and raised her eyes towards the soft blue sky above her, and all trace of fear or care left her smiling face. What was my surprise to see two beautiful little wings, glittering like gold in the sunlight, and bright with the rainbow's tints, gradually unfold from her shoulders! The child shook them for a few moments, as if to try their powers, and then rising above earth, and all its thorns, she gently flew over the painful place, and alighting safely on the ground beyond, looked back with a bright and thankful smile on the Difficulty which she had passed."

"Oh!" exclaimed Rosey. "What would I not give to have such beautiful wings!"

"Those wings, dear Rosey, are 'faith' and 'love,' which lift us above the world, which bear us onward in a heavenly course, which make us find our chief delight in doing the will of our heavenly Father."

"I have not these wings!"

George drew his little sister closer to him, and bending down his head towards her, whispered, "'Ask and ye shall receive.' God only can cause those wings to grow, by the power of his Holy Spirit; He can give them strength to bear us unharmed over all the rough places of life; and the waters of the river of death shall not wet even the soles of the feet of those who pass their depths, buoyed up on the glorious pinions of 'faith' and 'love!'"

THE BOY AND THE BIRD'S NEST.

"MARY, my love, all is ready; we must not be late for the train," said Mr. Miles, as, in his travelling dress, he entered the room where sat his pale, weeping wife, ready to start on the long, long journey, which would only end in India.

The gentleman looked flushed and excited; it was a painful moment for him, for he had to part from his sister, and the one little boy whom he was leaving under her care. But Mr. Miles's chief anxiety was for his wife; for the trial, which was bitter to him, was almost heart-breaking to her.

The carriage was at the door, all packed, the last band-box and shawl had been put in.

Eddy could hear the sound of the horses pawing the ground in their impatience to start. But the clinging arms of his mother were round him—she held him close to her embrace, as if she would press him into her heart, and the ruddy cheeks of the boy were wet with her falling tears.

"O Eddy!—my child—God bless you!" she could hardly speak through her sobs.

"My love, we must not prolong this," said the husband, gently trying to draw her away. "Good-bye, Lucy—good-bye, my boy—you shall hear from us both from Southampton."

The father embraced his sister and his son, and then hurried his wife to the door.

Eddy rushed after them through the hall, on to the steps, and Mrs. Miles, before entering the carriage, turned again to take her only son into her fond arms once more.

Never could Eddy forget that embrace—the fervent pressure of the lips, the heaving of his mother's bosom, the sound of his mother's sobs. Light-hearted boy as he was, Eddy never had realized what parting was till that time, though he had watched the preparations made for the voyage for weeks—the packing of those big black boxes that had almost blocked up the hall. Now he felt in a dream as he stood on the steps, and through tear-dimmed eyes saw the carriage driven off which held those who loved him so dearly. He caught a glimpse of his mother bending forward to have a last look of her boy before a turn in the road hid the carriage from view; and Eddy knew that long, long years must pass before he should see that sweet face again.

"Don't grieve so, dear Eddy," said Aunt Lucy, kindly laying her hand on his shoulder; "you and I must comfort each other."

But at that bitter moment Eddy was little disposed either to comfort any one or to receive comfort himself. His heart seemed rising into his throat; he could not utter a word. He rushed away into the woods behind the house, with a longing to be quite alone. He could scarcely think of anything but his mother; and the poor boy spent nearly an hour under a tree, recalling her looks, her parting words, and grieving over the recollection of how often his temper and his pride had given her sorrow. He felt, in the words of the touching lament,—

"And now I recollect with pain

How many times I grieved her sore;

Oh, if she would but come again,

I think I would do so no more!

"How I would watch her gentle eye

'Twould be my joy to do her will;

And she should never have to sigh

Again for my behaving ill!"

But boys of eight years of age are seldom long unhappy. Before an hour had passed, Eddy's thoughts were turned from the parting by his chancing to glance upwards into the tree whose long green branches waved above him. Eddy espied there a pretty little nest, almost hidden by the foliage. Up jumped Eddy, eager for the prize; and in another minute he was climbing the tree like a squirrel. Soon he grasped and safely brought down the nest, in which he found, to his joy, three beautiful eggs!

"Ah! I'll take them home to—" Eddy stopped short; the word "mother" had been on his lips; it gave a pang to the boy to remember that the presence of his gentle mother no longer brightened that home—that she already was far, far away. Eddy seated himself on a rough bench, and put down the nest by his side; he had less pleasure in his prize since he could not show it to her whom he loved.

EDDY AND THE NEST.

While Eddy sat thinking of his parent, as he had last seen her, with her eyes red and swollen with weeping, his attention was attracted by a loud pitiful chirping, which sounded quite near. Though the voice was only the voice of a bird, it expressed such anxious distress, that Eddy instantly guessed that it came from the poor little mother whose nest he had carried away. Ah! What pains she had taken to form that delicate nest!—How often must her wing have been wearied as she flew to and fro on her labour of love! All her little home and all her fond hopes had been torn from her at once to give a little amusement to a careless but not heartless boy.

No; Eddy was not heartless. He was too full of his own mother's sorrow when parting from her loved child to have no pity for the poor little bird, chirping and fluttering over the treasure which she had lost.

"How selfish I have been!—How cruel!" cried Eddy, jumping up from his seat. "Never fear, little bird! I will not break up your home; I will not rob you of your young. I never will give any mother the sorrow felt by my darling mamma."

Gently he took up the nest. It was no easy matter to climb the tree again with it in his hand, but Eddy never stopped until he had replaced the nest in its own snug place, wedged in the fork of a branch. Eddy's heart felt lighter when he clambered down again to his seat, and heard the joyful twitter of the little mother, perched on a branch of a tree.

And from that day it was Edith's delight to take a daily ramble to that quiet part of the wood, and have a peep at the nest, half hidden in its bower of leaves. He knew when the small birds were hatched; he watched the happy mother when she fed her little brood; he looked on when she taught her nestlings to take their first airy flight. This gave him more enjoyment than the possession of fifty eggs could have done. Never did Eddy regret that he had showed mercy and kindness, and denied himself a pleasure to save another a pang.

SENDING HORSES TO TRAVELLERS.

"POOR old Matthew!" said Lucy. "I hear that he is almost dying with cold!"

Ben was amusing himself with spinning on the table four bright half-crowns, with which his grandfather had presented him that morning, but he stopped for a moment to listen to his sister's account of the sufferings of his aged neighbour, and in a tone of pity said, "I'm sure that I wish that he were better off, he is such a good old man!"

"He had nothing but a crust all yesterday," said Lucy.

"Dear me!" exclaimed Ben, balancing his coin between his finger and thumb. "I wish that he had had as good a dinner as I!" Twirl, twirl, went the half-crown, looking like a half transparent ball, as it spun rapidly round; then gradually its shape altered, it sank lower and lower, then rattled down to its old position on the table.

BEN AND THE HALF-CROWNS.

"I wish that some one would help him!" said Lucy, glancing at the money.

"So do I, with all my heart!" replied Ben, in a manner that told pretty clearly that his charity would not go beyond his good wishes.

There was a pause, which was first broken by Lucy. "I read such a funny account, in a book about Thibet," said she, "of a curious piece of superstition, that I put mark in the place, just that I might read it to you; I thought that it would make you laugh."

"Let's have it!" cried Ben, pocketing his half-crowns, for he dearly loved anything funny.

So Lucy opened a volume of Huc's "Travels," and read the following account of the strange ideas of a young student of medicine at Kounboum:—

"One day," writes the missionary Huc, "he proposed to us a service of

devotion in favour of all the travellers throughout the whole world.

'We are not acquainted with this devotion,' said we; 'will you explain

it to us?' 'This is it: You know that a good many travellers find

themselves from time to time on rugged toilsome roads, and it often

happens that they cannot proceed by reason of their being altogether

exhausted. In this case we aid them by sending horses to them.' 'That,'

said we, 'is a most admirable custom; but you must consider that poor

travellers such as we are not in a condition to share in the good work.

You know that we possess only a horse and a little mule, which require

rest in order that they may carry us to Thibet.' He clapped his hands

together, and burst into a loud laugh. 'What are you laughing at? What

we have said is the simple truth; we have only a horse and a little

mule.' When his laughter at last subsided, 'It was not that which I

was laughing at,' said he; 'I laughed at your mistaking the sort of

devotion I mean. What we send to the travellers are paper horses.' And

therewith he ran off to his cell, and presently returned, his hands

filled with bits of paper, on each of which was printed the figure of

a horse, saddled and bridled, and going at full gallop. 'Here, these

are the horses we send to the travellers! To-morrow we shall ascend

a high mountain, and there we shall pass the day, saying prayers and

sending off horses.' 'How do you send them to the travellers?' 'Oh, the

means are very easy. After a certain form of prayer, we take a packet

of horses, which we throw up into the air; the wind carries them away,

and by the power of Buddha they are then changed to real horses, which

offer themselves to travellers.'"

"Ha! Ha! Ha!" laughed Ben, when she had finished. "I never heard anything so odd in my life. We have nothing in England like these paper horses."

"Well, I could not quite say that," observed Lucy; "there was something that reminded me of them just now."

"What was that?" said Ben, glancing up at his sister.

"Sending only 'good wishes' to those to whom we are able to send real help," Lucy replied with a smile. "They go just as far, and are exactly as useful to the poor, as the paper horses to the travellers in the deserts of Thibet."

THORNS AND FLOWERS.

"WHAT can be the difference between Martha and Susan Williamson?" said old Dame Phillips. "They are as like as two cherries—the same rosy cheeks, the same height, the same hair, you could hardly know one from the other."

"No wonder, for they are twins," replied Widow Green.

"And yet, how is it that when one of them comes in, it seems as if a sunbeam were shining into the room; yet, when the other is near, you would think that she brought the cold east wind with her?"

"One lives for others, and one for herself; that's the difference between Martha and Susan," said Mrs. Green, as she poured out her cup of tea.

"Ah! I often think that they are like two travellers, walking through the world with baskets on their arms. Susan has filled her basket with roses, and wherever she goes there's the sweet smell and the pretty flowers to make every one round her glad. Martha has filled her basket with thorns; you fear to come near her for the prickles; she is scattering thorns wherever she passes, and leaves pain behind her wherever she has been!"

"I pity the children when they are left to her care," said the widow.

"Poor little lambs, they have their full share of the thorns. It is a word and a blow with her; and as for poor Albert, with his weak ankles, he may walk on till he drops afore she will take the trouble of carrying him one step.—Why, here she is!" added the old woman, as Martha entered the house with a bold, careless air.

"Good-day, Mrs. Phillips: I've come to borrow your warm new shawl. You see," added she, seeing a look of reluctance on the face of the rheumatic invalid, "I'm going to-morrow in the steamer to Greenwich, and it will be so cold on the water."

"Come to-morrow, then," said the good-natured dame; "why should I be all this cold evening without it?"

"Oh, it is not convenient to come to-morrow!" cried Martha. "I'm off early, so please for it now." And as she stepped carelessly forward to take the shawl from the shoulders of her shivering friend, she knocked down the cup which Mrs. Phillips had just filled. But Martha never said that she was sorry for the mischief done; she never even stopped to pick up the broken pieces; her only thought was ever "self!"

Having got all she wanted, Martha turned to depart, but lingered for a few minutes to talk.

"Ah! Mrs. Green, so your son has gone to sea, I hear. How the wind is blowing, to be sure! I could hardly get up the street. They say there has been a dreadful shipwreck off the Irish coast—every one lost!"

Mrs. Green clasped her hands with a look of terror.

"I hope that the wind will have gone down before I start for Greenwich," said Martha, as she bounced out of the room, forgetting, of course, to close the door. She was gone, but she had left the thorns behind her.

In a few minutes a gentle tap was heard.

"Come in," said Mrs. Phillips; and the bright kind face of Susan appeared.

"Good evening, Mrs. Phillips; I hope that you are feeling better. I have brought you a pair of mittens, which I have knit for you, to keep your poor hands warm in this cold weather.—Mrs. Green, I'm so glad to see you; and will not you be glad to see 'this?'" she added, holding up a letter, and then placing it in the mother's trembling hand, with pleasure almost equal to her own.

"My son's handwriting!" exclaimed Mrs. Green. "How did you come by it, my dear?"

"I knew that you were anxious for letters, so I stepped round by the post-office to ask if there were any for you."

"Bless you!" cried Mrs. Green. "You are always thinking of others."

THE LETTER.

When Susan entered the house, she had found gloom and anxiety there. Before she left it, there were bright looks and smiles of hope and gratitude. She had left the roses behind her.

And can you guess the secret cause of her kindness, of the constant, cheerful benevolence which made her welcome to all? Why did she seem to live for others?—Because she "lived to God!" One sentence spoken by the blessed Saviour seemed ever present to her mind: "'Love one another as I have loved you.'" She knew that the Lord Jesus had "died for all, that they which live should not henceforth live unto themselves, but unto Him which died for them" (2 Cor. v. 15).