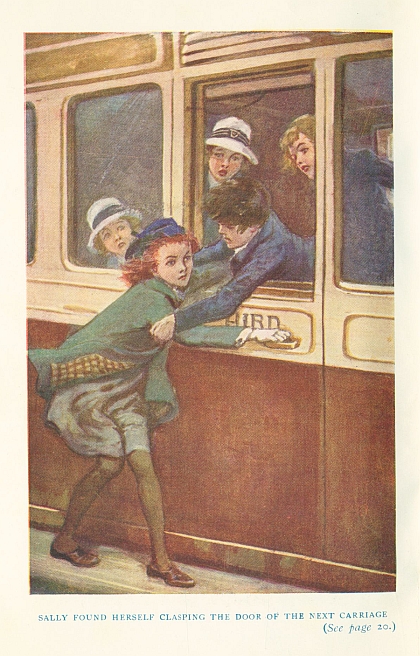

SALLY FOUND HERSELF CLASPING THE DOOR OF THE NEXT CARRIAGE (See page 20.)

Title: Sally Cocksure

A school story

Author: Ierne L. Plunket

Illustrator: Gordon Browne

Release date: October 24, 2025 [eBook #77119]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Oxford University Press, 1929

Credits: Al Haines

SALLY FOUND HERSELF CLASPING THE DOOR OF THE NEXT CARRIAGE (See page 20.)

A SCHOOL STORY

By IERNE L. PLUNKET

ILLUSTRATED BY GORDON BROWNE

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON : HUMPHREY MILFORD

REPRINTED 1929 IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

BY JOHN JOHNSON PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. Sally at Home

II. On the Way to School

III. Unpopularity

IV. A Cold Shoulder

V. Sally is Taken Up

VI. An Escapade

VII. Penalties

VIII. A Rift in the Lute

IX. A Broad Hint

X. The Breach Widens

XI. A Night Adventure

XII. Sally at the Fair

XIII. "Just Silliness"

XIV. Autolycus

XV. Will She Come?

XVI. Disillusionment

XVII. The New Term

XVIII. The Blotted Essay

XIX. Mischief

XX. Games and Toffee

XXI. Autolycus Gives Trouble

XXII. Autolycus is Lost

XXIII. The Portholes

XXIV. Reconciliation

XXV. Rescue

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

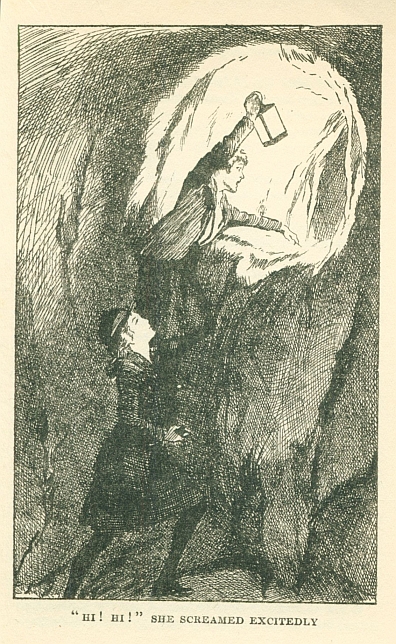

Sally found herself clasping the door of the next carriage (see page 20) ... Frontispiece

Sally felt herself swung off her feet

The policeman pursued for a few yards

"Hi! Hi!" she screamed excitedly

The hall-door bell rang violently. Sally Brendan, seated on the schoolroom hearthrug with a volume of Shakespeare on her knees, gave an expressive whistle and, dropping the book, ran to the window and leaned out as far as she could without losing her balance. In this way it was just possible to catch a glimpse of the front-door steps.

"Mrs. Musgrave! I guessed as much," she said, her head reappearing at last. "I can tell you one thing, St. Martin, she is in a thundering temper."

Her governess sighed. "You have no reason to say that, Sally: and at any rate this is lesson-time, and Mrs. Musgrave's call is intended for your mother. It has nothing to do with you."

"Hasn't it, though? Bet you a bob it has; and, as to her temper, vicars' wives are worse than most people because they have to keep them under so much. You should have seen her umbrella almost jumping in her hand with rage, and then the bell! You heard it yourself, and you can't deny it was like the noise telegraph boys make; and..."

"Sally, I must insist that you sit down and don't talk any more."

With a grunt Sally flopped on to the hearthrug, where she placed her ear to the floor, scout fashion, before re-opening her Shakespeare.

"Only wish I could hear through a carpet," she muttered discontentedly. "Bet your life she has come to tick me off to Mother. She looked mad, just like a cow that sees red."

Sally was quite right about Mrs. Musgrave's temper. The vicar's wife was very angry indeed. With a curt "No," she waved aside a cup of tea and declined a chair, striding the length of the drawing-room and back before she came to a halt beside Mrs. Brendan.

"Tell me whose writing this is! Be honest, Eva!" she demanded, tapping a square of white cardboard that she placed in the other's hands. On the cardboard was scrawled in pencil, between inverted commas,

"Two are Company."

"It ... it looks like Sally's writing," said Mrs. Brendan unhappily. "What do you say, Cecilia?"

A tall fair girl who had been standing by the tea-tray came over, picked up the card, and throwing it down impatiently answered, "It is Sally's writing, of course. What has she been doing now, Mrs. Musgrave?"

The vicar's wife almost choked as she said, "Insulting my husband, making him the laughing-stock of the parish. She is a wicked, unnatural girl."

"No, no; not unnatural or wicked," murmured Mrs. Brendan deprecatingly. "High-spirited, too high-spirited now and then, I admit, but she is so clever."

"I am glad no one ever called my daughters clever then." Mrs. Musgrave's voice rose almost to a shriek. "Cleverness of that sort is criminal and will only lead to prison."

"Of what sort?" asked Cecilia. "Do tell us, Mrs. Musgrave."

The vicar's wife glared at them both almost as if she did not see them, then sank down on the sofa.

"You know our weekly lectures under the Diocesan Mental Improvement Scheme?" she said. "I mean my husband's lectures in the Parish Room on Fridays. They are not well attended, but so few people care to improve their minds nowadays."

"Cecilia has a singing class in Clinton," interposed Mrs. Brendan hastily; "it is the only day Signor Corsi can run down from town, and I have been so tired lately, the doctor said 'Rest in the afternoons.' He did, didn't he, Cecilia?"

"Everyone has some reasons for not going, of course," said Mrs. Musgrave sourly. "I did not come to criticise yours. I have no doubt that if you and Cecilia are busy, for others Herbert's learning is too profound, too out of date in this respect, to please a superficial younger generation. Last Friday, at any rate, it was raining; raining quite heavily."

Mrs. Brendan's face brightened. "That was it, Alice. I remember I had my boots on intending to go out and then it rained and Cecilia said 'Don't go.' No, I forgot, Cecilia was in Clinton, so it must have been Amy, the housemaid. She takes such care of me."

"Indeed!" Mrs. Musgrave thrust out a hand for silence. "Your going or not is beside the point, Eva, and I must beg you to let me speak without interrupting me. As a matter of fact I had a cold and did not attend myself. When Herbert reached the room there was no one there at all except ... except..."

"Except...?" said Mrs. Brendan agitatedly. Surely Sally, unless dragged by force, would not have gone to a lecture on the Cuneiform Writings of Ancient Babylon?

"Except a goat," said Mrs. Musgrave slowly and impressively; "an evil-smelling goat of Farmer Reed's, tied to the front row of chairs."

"And ... and you mean it had this round its neck?" asked Cecilia pointing to the card, with its mocking "Two are Company."

In spite of heroic efforts her voice trembled with laughter, and Mrs. Musgrave bounced up from the sofa, pointing her finger at her.

"Laugh!" she said. "Laugh if you can, thoughtless girl, but your sister, by her rudeness, her cleverness if you will, has undone years of Herbert's patient work in the parish. Some of the choir boys were peering through the window, giggling, and as he returned home they dared to call out 'Giddy Goat' after him down the street. 'Giddy Goat!' Think of it! To Herbert." At this point she collapsed on the sofa and began to weep.

"I ... I didn't mean to laugh. It was horrible of Sally," said Cecilia, conscience-stricken, while Mrs. Brendan went over and laid her hand on Mrs. Musgrave's shoulder.

"We have been friends for years, Alice," she said. "Don't let this come between us. I am ashamed of Sally."

"You have cause to be. You will have more cause," said the vicar's wife bitterly between her sobs. "She is a dreadful child, without heart or conscience."

"She is my daughter, Alice, so I can hardly agree with you," interrupted Mrs. Brendan, in what, considering her mild temperament, was almost the heat of anger. "Sally has plenty of heart, but she is thoughtless."

"She is thoroughly spoilt, Mother," broke in Cecilia; "first while you were in India, by Uncle Frank and Aunt Antoinette, and now at home. I am sure we owe it to Mrs. Musgrave to acknowledge this. Sally is just a spoilt little beast."

"Thoroughly spoilt and selfish," agreed their visitor, drying her eyes and beginning to pull on her gloves. "All I can say is, Eva, that if Sally remains in Hartcombe Vale and is allowed to break away from her governess and play tricks like a street urchin, I shall consider it a direct insult to Herbert."

"I will speak to her, of course," murmured Mrs. Brendan, and Mrs. Musgrave, now standing by the door, laughed scornfully.

"You mean, my dear Eva, that Sally will speak to you, and will prove in a few brief words how right and correct—clever and high-spirited, I should say—her conduct has been. No, Cecilia, do not interrupt me. I owe it to Herbert and the parish to enter my protest at least."

At this moment violent sounds were heard overhead, the crash of something heavy on the floor, a scream, more things falling, and then a girl's clear, ringing laugh.

"The schoolroom, I believe?" said Mrs. Musgrave, "and another exhibition of Sally's high-spirited cleverness, I suppose?"

As she opened the door she sniffed and shrugged her shoulders. "Let me see you off," returned Cecilia coldly. She was very angry at the way their visitor had spoken to her mother, the more that she felt the underlying reproach was true. Sally was an odious child. There was no use blinking the fact.

In the hall Mrs. Musgrave bade her come no further. "I am quite capable of seeing myself off; besides, I might be tempted to say more than I should wish in my last words." After which she added, "It seems you are needed to restore order in the schoolroom."

To judge from the continuous noise upstairs, loud laughter mingled with the barking of an excited dog, this was likely to be true.

"Oh, St. Martin!" rang out a girl's voice. "What rotten bad luck! but I can't stop laughing; you do look so funny."

At this point Mrs. Musgrave closed the front door, and Cecilia, rage in her heart, ran up the stairs two at a time.

In the schoolroom she found even greater chaos than she had expected—a bare table, an inkpot emptying itself amongst a heap of books in the grate, and on the floor someone struggling wildly to free herself from the table-cloth, while a fox terrier plunged at her protruding feet.

"Oh, mighty Cæsar! Dost thou lie so low?" chanted a small, thin girl with a mass of red hair framing her freckled face; as, seeing her sister, she drew herself up into a theatrical attitude and pointed to the recumbent figure.

Cecilia told her sharply to be quiet, and having turned the fox terrier out of the room, knelt down and extricated the governess; but when she tried to help her to her feet Miss Martin refused to do more than struggle into a sitting posture.

"Will you kindly ask Sally to bring me scissors?" she said, her voice trembling, and the tears rolling down her cheeks. "She has sewn my skirt to the carpet."

"Sally!"

Cecilia's eyes blazed, but Sally only laughed. "She had been reading to me, yards and yards of Shakespeare, and I was fed up, so I said I would only listen if I might sit on the rug, so St. Martin said, 'Right oh.'"

"I never said 'Right oh'," exclaimed the scandalised Miss Martin. "I said you might remain there if you were quiet."

"Well, I was quiet, once I found the darning wool, and St. Martin has such a long skirt that I button-holed her down by it, and then when Mary came to say tea was ready in the dining-room I truly and honest Injun forgot I had done so and..."

"And I rose from my chair," said Miss Martin, "and I put my foot into my skirt and..."

"It was a mistake to clutch at the tablecloth as you fell, all the same," interposed Sally gravely. "I simply shouted, 'Don't clutch,' and you clutched, and there you are."

"Sally, go to your bedroom," said Cecilia sharply, as she cut the darning wool and pulled the governess on to her feet. "Miss Martin, I am so sorry; it was abominable of her."

"It was unpardonable," said Miss Martin, pulling the frayed ends of wool out of her skirt with trembling fingers. "I am afraid I must ask to see your mother at once, Miss Brendan."

"You mean you won't come back again?"

Sally was still standing in the doorway.

"I do mean that. It is impossible to teach you anything."

"Sally, did you hear me say go to your bedroom?" broke in Cecilia impatiently, but the girl still lingered.

"Let me speak to St. Martin alone," she said.

Miss Martin shook her head. "I have no wish to do that, Sally. It is too late if you think an apology can cover all your rudeness; and now, Miss Brendan, may I see your mother?"

As they went downstairs together Sally watched them from the landing, a derisive smile at the corner of her lips, that marked, however, a certain regret. It was a pity that St. Martin insisted on going. Of course, she wept too easily, but all the same she was a bit of a sport, and had forgiven and forgotten many little scenes scarcely to her pupil's credit. In addition, she had always admitted that Sally was clever, and Sally liked people who were ready to do this.

"Clever people aren't like other people; they have got to have outlets for their energy and originality," was her argument for silencing various twinges of conscience; and she at once put it forward when Mrs. Brendan sent for her to the drawing-room as soon as Miss Martin had gone home.

Cecilia was there to strengthen her mother, and said angrily, "If only you didn't think yourself so clever."

"Know—not think," said Sally sweetly. It was no use losing your temper with a sugar-plum like Cecilia.

"I am so clever you know, frightfully clever," she continued, "and Miss Martin was such an ass, quite a nice ass, of course, not a goat like the vicar and his double."

This diverted the conversation from the schoolroom to the lecture, and as Sally recorded afterwards in her diary, "The floodgates opened," but even Cecilia admitted that the ensuing deluge fell like water off a duck's back where the culprit was concerned.

"I really truly am sorry if I made Mrs. Musgrave horrid to you," was the nearest confession to which the sinner could be won; and when she had been sent to bed, and carried off a choice of library books for company, Mrs. Brendan admitted that this was not enough.

"She will have to apologise to Mrs. Musgrave and Miss Martin, Cecilia. I must talk to her alone to-morrow."

"She will have to be sent away," returned the elder sister. "I was at school at thirteen, and why not Sally, who is nearly fourteen?"

"She is the youngest," said Mrs. Brendan weakly, "and you know she has been away from me so much."

"I admit Aunt Antoinette did her no good, except to teach her French, and as to Uncle Frank, why you ever left her with them like that for months and months on end I can't imagine."

"You see, your Uncle Frank was so devoted to her as a small child, while your father and I were still in India, and then when your father died and I came back he wanted to keep her, and as I had you and the two boys, and he had been so good to Sally, I didn't like to refuse. I fear I did wrong, however, very wrong; I am sorry now."

Mrs. Brendan usually repented of the few decisions she was prevailed upon to make, and now she shook her head sadly.

Cecilia laughed somewhat maliciously. "Uncle Frank was sorry too. He had enough of her after a bit, and packed her off home."

"My dear, that is ungenerous. It was not till his boy was born, remember, and then there would have been the difficulty of maintaining a nursery and a schoolroom at the same time, as Sally was nearly eleven. He always said she was clever and offered to pay for her education."

"He said, 'Send her to school,' didn't he?"

Mrs. Brendan was silent. This was perfectly true. She could remember her brother-in-law's face quite well when he gave this advice.

"School will do her a world of good, teach her to find her own level, you know," he had said, and when Mrs. Brendan had asked anxiously, "You think her clever?" he had answered:

"Abominably, the makings of a first-class prig, and may I be forgiven for training her."

Undoubtedly Uncle Frank was right. Sally was clever beyond the average girl of her age both in games and work, fearless and quick, with a boundless ambition that made her strain every nerve to excel in whatever she undertook.

"Let me; I can do it," had been her earliest watchword, and a proud uncle had delighted in the pluck and endurance that had backed this assertion.

"All right, kiddie, I will show you," he would say good-naturedly, whether it was a case of arithmetic or cricket, and so put Sally through a strenuous and valuable apprenticeship.

"That child will get somewhere," he would say delightedly, while Aunt Antoinette, who was earlier disillusioned as to her spoilt niece's charms, shrugged, and murmured:

"It may be ... yes ... but I ask you ... where?"

By the time Sally was thirteen her elder sister had no doubts at all as to her future destination.

"It will be a reformatory, Mother. Either we must take steps to discipline her, or the magistrates will, and we shall all be disgraced. There's nothing but school. You won't get another governess who will be an angel like Miss Martin."

"She never knew how to manage Sally."

"You can't manage a wild cat except by shutting it up, and Sally is about as easy to control."

"She is so like her father." Mrs. Brendan sighed, then added hastily, in an attempt to appease Cecilia's angry silence, "I mean she always knows her own mind. He did, you know. It has been such a responsibility without him."

Still there was silence, and the elder woman, feeling its weight and intensity, yielded at last.

"Oh, very well, my dear. I expect you are right. She shall go to school."

"Seascape House, next term, the summer one, and you must tell her she will jolly well have to stop."

"Of course!" said Mrs. Brendan, "of course," but she looked troubled.

"I shan't stop at school a minute longer than I want."

Sally was saying good-bye to Mrs. Brendan, and that good lady could only find courage at the minute to murmur:

"But, my dear, of course you will remain. I beg you, Sally."

There were tears in her eyes, and the girl answered gruffly, but so low that Cecilia in the doorway could not hear, "All right. I'll try, Mum."

Then she threw her arms round her mother's neck, gave her a wild hug, and joined Cecilia in the hall, laughing rather loud as she banged the drawing-room door behind her.

"You will have to be quieter at Seascape House, Sally."

"Shall I?"

"I should hope so. Why, the prefects will turn you down at once for that."

"Blow the prefects, and blow their doors tight too!"

Cecilia smiled, offensively Sally considered, as she clambered into the taxi beside her.

"Hang the whole lot of superior idiots to weeping willow trees for all I care," she persisted. "You needn't think I'm going to let school or prefects upset me."

"You are so sure, cocksure even, on things you don't know anything about, aren't you?"

"I am usually right, you see. I don't care what anybody says, so they can't worry me."

"Oh, shut up and don't be silly, Sally."

"Shut up yourself."

The quarrels between the sisters, frequent in spite of Cecilia's good temper, usually degenerated into a kind of puppy's barking, and then trailed off into silence. Now the two sat moodily while the local train crawled from Hartcombe to Clinton, and there disgorged its passengers.

"We should see Violet Tremson here," said Cecilia at last, breaking the silence. "I wonder if she is one of that group. They all have the Seascape House hatband."

"I don't want to see her. Mrs. Musgrave's pet lambs are not in my line."

Now Mrs. Musgrave, repenting of some of her animosity towards Sally as soon as she heard that she was really being sent to school, had recalled the existence of a young cousin at Seascape House.

"Of course, Violet is older than you—fifteen, I think—but such a nice quiet girl, and so clever, without being affected."

It had been an unfortunate recommendation, and Sally had merely scowled in response. Whoever she chose as her friend she was determined from that minute it should not be Violet Tremson.

"Beastly sort of prig. Mother's darling business, I expect." She had discouraged Mrs. Brendan when the latter suggested asking Violet over from Clinton during the Easter holidays, and now she said sharply to her sister:

"Look here, I'm not going near that lot, they've got a mistress with them."

Hurriedly grasping up her new yellow-brown suit-case, she led the way along the platform, and tumbled into a carriage already containing five girls. Four of them were established in the corners, but seeing the grown-up Cecilia with a foot on the step, one of them politely moved. "Are you coming in?" she asked.

Now was Sally's opportunity to show off before the sister who declared she would be awed by the inmates of Seascape House as soon as she came in contact with them.

"No, she's not, but I am, thank you," and she coolly took the corner seat.

There was hushed silence in the carriage while the girls stared at her round-eyed, and Cecilia blushed at her impudence.

"You needn't stop, Cissy; I'm all right."

Sally's voice was as calm and even as usual, but she was glad when Cecilia took her at her word, and with a doubtful glance at the five said, "I do hope you will be all right," and vanished.

"Oh, my Empress of India!" said one of the girls rather shrilly, and the others giggled; they were about Sally's size, a healthy, cheerful-looking set, and they stared at her as though she were an interesting object from the Zoo.

"Shall we shift it?" demanded another, edging near the new girl; but at this minute, when Sally was preparing to defend her corner with tooth and nail, a distraction arose. "Olive's going to be left behind. There's Proggins trying to shove her in, and the guard with the whistle to his lips."

"Proggins ought to be in here, herding us."

"She'll have to sprint then. Good old Proggins."

"Oh, hurrah! Olive has seen us. Come on, Olive."

All the five, leaning out of the window or kneeling up with their faces to the glass, yelled aloud; then cheered as a dark-haired girl of fourteen tumbled into the carriage, hatless.

Squeezed in her corner, Sally could see the mistress, evidently the so-called "Proggins," fumbling for Olive's dropped hat and umbrella. She retrieved them and made a run towards their carriage, but the train had already begun to move, and the guard, opening a door further back, unceremoniously pushed her in and banged it.

The six burst into uproarious mirth.

"Good old Proggins; not quite her centre forward style, I think?"

"A bit slow on the ball," said Olive, throwing herself back on the seat beside Sally and fanning herself with a newspaper. "Anyhow, it wasn't a good pass on my part. School hats aren't weighted right."

"She'll be jolly mad with you when we get to Parchester."

"Sufficient unto the day..." and then Olive stopped and began to stare at Sally.

"A new kid," she said, "with a head like a golliwog illumined by a sunset. My child, yours is not the tidy sort of poll we expect at Seascape House, especially on Sundays. Old Cocaine will put a tax on it."

Sally raised her eyebrows, then opened her magazine with a yawn. "Is your hair generally admired?" she asked. "It looks painted on like a wooden doll's."

This pleasantry was received in dumbfounded silence. If Sally intended to make a sensation she had undoubtedly succeeded, and smiled to herself at the result. It was one of her maxims to carry war into the enemy's country on the least provocation.

Now there was a pause, suspended hostilities, while the six whispered in corners. Olive was being told of the new girl's dramatic entry into the carriage; so much Sally could guess from her round-eyed stare and the agitated way in which she ran her fingers across her dark, smooth-clipped head.

"What's your name?" she demanded.

"Sarah Brendan."

"And your age?"

"Thirteen and a half."

Sally was proud of this, for she knew she had done very well in her entrance examination, so well that even Cecilia had gasped. It amused her now to see the looks of satisfaction on the faces of the six, especially when Olive said languidly:

"Quite a small kid, which accounts for your lack of manners. We shall have to teach you."

"I fear you will hardly be in that position."

"What do you mean?"

"That we are not likely to be in the same form, or are you all mistresses?"

"We are all 'Lower Fourth' here except Susy, who is in the 'Upper Fourth.'"

"Exactly." Sally smiled; it was an offensive smile and led the girl called Olive to seize her magazine out of her hand and throw it on the floor.

"You horrid little scrub!" she said. "What are you driving at?"

"That I am in the Remove—which is above the Fourths, isn't it?—and so I am not likely to see much of you children. As to your manners, give me back that Pearson's."

"Get it yourself."

Taken unwarily, Sally bent down to do so and found herself pitching forward on her nose, while with a shout of delight Olive seated herself in the corner. It was dirty on the floor, and Sally's temper was in shreds by the time she had picked herself up.

"Move at once, you beast," she said, her face white with passion; but unlike her family, who had been taught by Mrs. Brendan to propitiate rather than exasperate her when in one of her black moods, the six girls crowed with joy at her discomfort.

"Go and wash your face, darling," cried one; and another: "Here's a seat," pulling at Sally roughly and then sliding across the vacant place before she could sit down.

For the next ten minutes pandemonium reigned, and for once, though she was undoubtedly the cause, Sally had not created it for her own pleasure. The tears rose to her eyes, but at the general offer of handkerchiefs and a bucket she forced them back.

"I'll make you pay, you horrid little beasts," she said, clenching her hands on the ledge of the open window behind her, but the threat only evoked shouts of: "For she's a jolly smart fellow," to which the accompaniment was a tattoo of as many feet as could reach the new suit-case.

"Its mother won't know it soon," said Olive, examining the no longer shiny surface, when the singers at last paused, exhausted.

"You have nearly knocked a hole in it. I shall tell Miss Cockran." Sally's voice trembled with rage.

"If you do, you will be a dirty little sneak, and sent to Coventry by the whole school."

"I don't care."

There was more laughter, and once more the six began to sing, and Sally hated them while she stood there helpless, the more that they seemed to have forgotten her very existence.

"Will you leave my suit-case alone? and give me back my seat?"

She pulled at Olive's sleeve, but though she repeated her questions twice that young lady only looked at her lazily and laughed.

"In both cases the answer is in the negative," she returned and, leaning back, closed her eyes.

"Very well," said Sally quietly. Her anger had died down into a cool fury that was none the less intense, yet what could she do? She looked out of the carriage window and realised from other journeys that the train was nearing Southampton, and Southampton was the first stop after Clinton. She could, of course, get out there, but the exit would be undignified, and in imagination she could hear her tormentors laugh, and see them kiss their hands to her in exultant farewell at her discomfiture.

Now Sally liked her entrances and exits to be dramatic, not undignified, and in a flash of inspiration the suggestion of how to achieve this came. Just before Southampton there was a tunnel, and when the train plunged into it, while everyone's eyes were growing accustomed to the gloom, she would open the door and step along the footboard to the next carriage.

"That will give them a fright," she said grimly to herself, and as usual did not pause to consider her own folly in risking her life for a matter of wounded pride. Besides, she was used to climbing and had once played follow my leader with her brothers on a local train to the same tune.

With a shriek the train plunged into the tunnel, and Sally, whose fingers had been clasped on the handle, slid open the door and felt for the step; the next minute she was swinging on the footboard, while the hot air beat her face and blew her mop of hair across her eyes. Her hat she had lost on the floor during her struggle in the carriage.

As the train emerged once more into the day, with a glint of sunlight across the harbour, Sally found herself clasping the door of the next carriage while a girl, leaning out, grasped her by the shoulders.

"You young fool; what made you do such a thing?"

There was a group round Sally now on the platform, including Proggins, her face deathly white, and all the elder girls from neighbouring carriages; above their heads she could see the anxious expressions of her fellow travellers of the Fourths. Certainly she had impressed them.

"Why did I do it?" she said jauntily, and in a loud voice. "Why, I couldn't get a decent seat where I was, and it was so stuffy."

At this a few of her audience laughed, though some merely stared, while Proggins grasped her firmly by the shoulder.

"You will sit with me," she said.

"May I have my suit-case and magazine, if you have quite finished with them?"

This was the moment of Sally's triumph, for as she turned and looked up at Olive the latter meekly handed down her property through the open window with never a gibe or scowl.

"I said to Cecilia that I could look after myself," the new girl complacently told herself, as she settled down to read. She was not unconscious that her companions, including Proggins, were regarding her with curiosity.

Sally Brendan ended her first week in the Remove at the top of the form. What was more, she kept her place there easily during the ensuing three, to the disgust of her nearest rival, the fifteen-year-old Dorothy Baker.

"Never mind, I shall be out of your way in the Lower Fifth next term," said Sally kindly, when the class list was read. The effect of these words was naturally far from soothing.

"Oh, go and put your head in your desk; I didn't ask you to patronise me," was the furious response, but Sally only laughed.

What was the use of propitiating these silly rabbits, as she had christened her present form companions, any more than the kids of the Lower Fourth who had teased her in the railway carriage? With the Lower Fifth, whom she soon expected to be her future classmates, it was different, and Sally would dearly have liked to make friends with one of their number at least, a dark-haired girl, Trina Morrison, nicknamed "Peter" by her intimates for reasons long forgotten.

"Peter" was rather old for the Lower Fifth, a lazy but far from stupid girl of seventeen, who spent much time and ingenuity annoying those in authority while her other talents ran to seed.

"School is such a bore," she would drawl to the group of her admirers. "It's really too silly, all these old rules; let's pitch some of them overboard!" and Sally, hovering on the outskirts, would laugh with the rest as some new evasion was expounded, and try to catch her idol's eye. So far she had not succeeded, though Peter, she felt sure, was one of those who had noticed the incident of the railway carriage.

This incident created quite a sensation for the moment at Seascape House, though when Olive Parker's version of the affair was broadcast it had not tended to make the new girl popular.

"Cheeky little beast!" was the general opinion, chiming in with a prefect's comment, "Stupid little ass. She deserved to break her neck."

Thus the school as a whole decided to ignore the incident.

Only one girl mentioned it to Sally, and that more by way of introduction than in admiration or blame.

"I'm Violet Tremson," she said, coming up to Sally in the large playroom that evening. "I'm sorry you didn't have much of a time on the journey. I was keeping a place amongst our lot, but I didn't see you at Clinton."

"Thanks."

Sally, with remembrances of Mrs. Musgrave, spoke sulkily, though she could not help being attracted by the tall fair girl's friendly smile.

"I tried to wangle your sleeping in our dorm., but I don't seem to have succeeded."

"Oh, I shall be all right; I can sleep anywhere."

"That's good!" Violet Tremson was smiling broadly now and cast a hasty glance over her shoulder before she went on. "You see that fat girl over there, Pilladex we call her, because her name's Decima Pillditch?"

"The one with no eyebrows and pig's eyes?"

Violet Tremson stiffened slightly. "She's quite a good sort when she's awake, if she's not beautiful," she said a little resentfully, "and you'd better be careful, for she's Upper Fifth and in the running for a prefectship. Anyhow she is head of your dorm, and sleeps with her mouth open and snores; adenoids, I suppose."

"I shall put soap in her mouth," said Sally. "I did once to my brother Fred and he was frightfully sick."

"Well, I wouldn't try it on the Pilladex, if you want to lead a quiet life. You have never been at school before, I expect?"

"No, why on earth should I?"

Something in Violet Tremson's voice made Sally feel angry. It was almost like hinting, "You are barely out of long clothes"; and she added, "I know a good deal more than most schoolgirls I have met."

"Indeed? I hope you won't begin to lose intellectual ground here."

It was intolerable. This tall fair girl with her bland smile was actually laughing at her, and Sally hated laughter when she couldn't see the joke.

"Anyhow it's no business of yours," she said, and turning her back walked off.

Violet Tremson did not come near her again, and Sally told herself she was glad.

"A superior ass like any cousin of Mrs. Musgrave's was bound to be," she wrote to her mother, and scowled to think that the superior ass was in the Lower Fifth. "Of course, she's nearly fifteen," she added when she gave this information, but it did not make her feel much better.

These were bad days for Sally Brendan, almost a nightmare when she looked back on them afterwards, and only her half-muttered promise to her mother kept her from doing something outrageous that might lead to her being expelled.

"I'm unpopular just because I can do things, but I don't care," she wrote home, and secretly cared a great deal. Hitherto in her life she had mixed chiefly with grown-ups who spoiled her or tolerated her shortcomings because her daring amused them, and this latter had been the case with her schoolboy brothers.

"Sally is a regular sport," they would say, and forgive her vanity because she could bowl and swim and climb, was never afraid, nor complained when she was hurt. Younger children too had been willing to take a daring leader at her own valuation, and it was only now when she was brought into contact with numbers of girls of her own age that Sally realised she could be seen and not admired, also that her wit might fail to hit so many targets.

In school hours things were not so bad. Sally easily kept her first place, enjoyed her lessons, and liked Miss Castle, her form mistress, who was always ready to help her and praise her work.

"Well done, Sally," she would say, pausing by the new girl's desk, and sometimes, "Why don't the rest of you use your brains like Sally Brendan?" Occasionally she found fault. "Don't be so certain you are right, remember pride before the fall; you are too cocksure," and this led to Sally's nickname in the form, "Miss Cocksure," and a rhyme chalked on the board one morning before school:

"Miss Cocksure

Is a bore,

I'm quite sure

She won't score."

"Won't I just?" muttered Sally to herself and smiled calmly on the class, as calmly as Miss Castle told the girl nearest to the board to clean it, before the literature lesson began.

"They are jealous because she likes me," was Sally's inward conviction, and there was some truth in this. It was the fashion in the middle forms of Seascape House to "adore" Miss Castle because she was young, rather pretty, very friendly, and could read poetry aloud with just the right amount of expression.

"Not woodenly like old Cheeserings (Miss Cheeseman) or pouring out yards of sob-stuff like Smutts (Miss Black)," was the general verdict, and when Miss Castle stage-managed Shakespeare plays there was dramatic fervour throughout the school.

Certainly it was annoying for the Remove that Miss Castle should accept this conceited new girl as one of their bright stars, give her principal parts in Shakespeare scenes, and read large portions of her essays aloud. That she might really like Sally for her hard work and enthusiasm, and most of all perhaps because she did not bore her with languishing glances and sentimental attentions, did not occur to Dorothy Baker or her friends.

"Horrid little cad," they denounced Sally, adding, "Won't we take it out of her in games!"

They did. The new girl was not even asked if she knew how to pitch a straight ball, but was sent to join the junior game.

"You had better be a Shrimp," said Miss Rogers (Proggins), the games mistress, who had not admired Sally's exploit on the train and thought she needed keeping in her place. She added sharply, "Go at once; Olive Parker will tell you what to do."

Olive, who was captain of the Shrimps (junior cricketers at Seascape House were divided into Shrimps and Sardines), was only too ready to undertake the task, though after the new girl had bowled her three times over in practice at the nets she did not give her the opportunity of doing so again.

"You'd better go out boundary or long stop," she would say, and yell at Sally to "Get a move on" or "Throw the ball up, can't you?" whenever she had the chance.

"You think yourself so jolly superior, don't you?" she said indignantly when the younger girl sulked, only to grow red with anger herself at the quick retort:

"I am superior to this sort of play anyway."

It was true, and Olive Parker knew it. She was being horribly unfair, but at the same time she and the rest of the juniors disliked Sally so much that she could not do anything right in their eyes.

When she had been batting one day and was bowled second ball (she usually made a very creditable score) there were cheers from all the Shrimps and derisive laughter. Sally had learned to make her face very wooden, but there were tears smarting under her lids as she walked back to the row of seats, ostentatiously filled up as she approached. No one spoke to her, though Edith Carter, a girl in the Upper Fourth, said something about "What price ducks' eggs?" and laughed. Then there was silence, and looking up Sally saw Miss Rogers standing beside her, and a big girl, Doris Forbes, the school captain.

"You don't generally get out so quick, do you?" asked Miss Rogers abruptly.

Sally shook her head. She could not trust herself to speak because of the lump in her throat.

"I thought not. You hold your bat well. Did your brothers teach you?"

"I have played a lot with them." Sally was beginning to recover. After being ignored so much, even casual interest was pleasant, but at this minute the last wicket fell and her side went out to field.

Sally was put boundary as usual, and except that Olive was less hectoring and more business-like owing to the presence of her exalted audience, the game dragged on its usual slow course.

Suddenly there was an interruption.

"Let Sally Brendan bowl now," called out Miss Rogers, and she walked across the pitch and began to umpire.

Sally felt her heart beat very fast, but she looked quite calm as she took her place behind the wickets and picked up the ball. She had had no practice lately in bowling, but her eye was good, and every nerve alert with the consciousness that now or never was her opportunity.

Her first ball, a fast one, went wide, her second pitched too short, but the third rooted Edith Carter's middle stump almost out of the ground.

"Now I've got the right length," said Sally to herself exulting, and the wickets began to fall rapidly before her onslaught.

"What I want to know, Olive Parker," said Miss Rogers as the last of the batting team withdrew with a scowl and a duck's egg, "is why you never mentioned Sally Brendan as a bowler when I asked you last week about any promising Shrimps?"

"Don't know!" muttered Olive sullenly.

"Hardly keeping your eyes open, was it?" suggested Doris Forbes, the cricket captain, and then Miss Rogers said decidedly:

"We'll talk about that afterwards, and you, Doris, settle what you like about Sally."

"Yes, Miss Rogers."

As the mistress turned away Doris beckoned to Sally. "You can come and bowl to me at the nets," she said.

Sally enjoyed the next half-hour more than any she had spent at Seascape House; not that her bowling remained unpunished, but that it aroused all her energy and skill. Soon she had forgotten the crowd round the nets and was absorbed in her task, not even hearing the school bell ring out seven o'clock till her batter called to her to stop.

"H'm! You're keen enough," said Doris Forbes.

"It's the first real play I have had since I have been here."

"All right, you can come and try your luck with the Eagles to-morrow," she said. "Now trot away."

Sally Brendan went back across the playing fields all alone, but for once unconscious of her isolation. She was to play with the Eagles, the group of senior cricketers from whom the first and second elevens were chosen, and Olive Parker and her Shrimps would torment her no longer. While she changed for supper visions of herself captaining the first eleven and telling everyone what to do passed before her eyes.

"I said I'd score," she laughed to herself triumphantly, and when Violet Tremson separated herself from the crowd in front of the dining-room door and congratulated her on her play at the nets she answered coolly:

"Oh, that's nothing. I never got a chance before at this place."

Some of the girls round sniggered, and Sally rather wished she hadn't been so lofty. After all, it was decent of Violet, who wasn't in the Eagles at all, but the middle sort of game of the Bears and Wolves.

"I'll give you some practice if you like," she added, and heard someone say:

"What frightful cheek! Leave the little bounder alone, Violet. Her head's been turned so that it's simply reeling."

It was Doreen Priestly, another of the Lower Fifth, whom Sally had secretly admired but henceforth hated. She had not meant to be superior in her offer, merely friendly, and though Violet answered quite gratefully: "Thanks. I'd like to but I'm no use at all at batting," she suspected secret laughter at her expense.

"Anyway, I'll be too busy for a bit," she said in a rough voice and pushed her way into the dining-room.

"What beasts they all are at Seascape House," she decided, "except, of course, Doris Forbes and Miss Rogers—oh, and Miss Castle!"

By half term Sally had played with the Eagles for some weeks and won herself a place in the Second Eleven.

"I should be in the First, but that there is so much jealousy amongst the Seniors, who are a rotten lot," she wrote home to her mother; and Mrs. Brendan sighed as she read out this characteristic message to Cecilia, who said:

"Still as offensive as ever, it seems! I suppose her impudence is chronic now."

This was exactly the verdict of Seascape House, from Olive Parker, who was henceforth driven to satisfy her dislike of the new girl by muttered jeers in the passage, to Doris Forbes, the Sixth Form Cricket Captain.

"Look here, kid! If there is any more cheek on your part you will have to go back to the Shrimp pool. I am sick of complaints of the way you give unasked advice to your elders, and put your oar in on every occasion. You are not a cricket coach."

Sally looked sulky, but for once did not answer back. She loved the Eagles game, while the thought of a return to shrimping, as it was called, made her feel sick at heart.

"Why do you do it? ... 'bound' so much, I mean?" went on Doris gruffly. She was a good-natured girl with a secret liking for her recruit's pluck, and yet she could not but admit that the child, apart from her play, was a prize beast of the worst order.

Sally flushed resentfully.

"I ... I don't bound," she said. "It's just that I know about cricket, style, I mean. My uncle who taught me played for Yorkshire for years, and when some of them are holding their bat all wrong they get mad because I'm a lot younger than they are, and..."

"I suppose if you weren't such a kid you would know it was wise to hold your tongue and be less objectionable," broke in the elder girl. "I hear they call you Miss Cocksure, and if I were you I would live that name down as quickly as you can."

"I didn't give it to myself."

Doris Forbes laughed and laid her hand on the other's shoulder.

"Don't gobble with rage or I shall christen you Miss Turkey Cocksure," she said; and then, with a sudden return to the dignity of her office, "Anyhow I sent for you not to argue with you but to give you some wholesome advice and a warning. Control your tongue and manners or you may find yourself scrapped. See?"

She turned on her heel and walked away without waiting for an answer; and Sally clenched her hands to prevent herself running after her with the usual, "I don't care."

For once she did care, and when Olive Parker, who had been trying to listen to the conversation from a distance, called out in jeering tones, "Scrapped, are you, Cocky?" she turned on her savagely, instead of passing her by as usual with her nose in the air.

"No! You half-baked shrimp. If you are able to read, look on the board and you will see that I am down to play against Borley Club next Saturday."

This was quite true, and Sally Brendan, like the rest of the Second Eleven, had been counting the days to the match; for it was to be played, not on the home ground, but at Borley, and this meant a char-a-banc ride with lunch and tea at the other end.

"Such a scrumptious feed too," said Cathy Manners of the Upper Fifth, who had played in the match last year. "Why, we had chickens and salad for lunch; I don't mean beastly oil and vinegar stuff, but fruit and cream with ices after tea."

Those of her audience who would not be going groaned; and one of them, Mabel Cosson, put an end to further descriptions by saying:

"Bet you anything you like the match is off! Patty Dolbey is in the San. with a temperature and headache; and Frisky, who is in her room, told me she was spotty all down her neck, only Matron said she wasn't to spread it about."

"That is why you are both keeping so quiet about it, I suppose?" suggested someone, while another voice chimed in:

"Spread what? Small-pox? I am jolly glad I have just been vaccinated. It makes absolute pits in one's skin, I hear."

After this, conversation degenerated into a medical discussion ranging over complaints varying from the Black Death to epileptic fits. Sally Brendan, standing on the outskirts of the group, took no part, for though, having had both measles and chicken-pox, she felt in a position to contradict each of the speakers in turn, she had learned that it was waste of breath to attempt this. Either her remarks were ignored, or someone took her by the shoulders and pushed her away out of earshot.

She would not indeed have remained so close but that she wanted to hear more about the match. This match, she had decided, would give her a chance to distinguish herself before an unprejudiced audience.

As she lay awake that night, with only Decima Pillditch's snores to distract her thoughts, she pictured the captain of the Borley eleven congratulating her on her bowling, and saying:

"We all think that you must be really First Eleven, aren't you?"

That would be a heavy score against Doris Forbes and other snobs of the Upper Fifth and Sixth. Sally turned over on her side with a satisfied smile on her lips, and hopes soon became merged in dreams, not merely of pulling off a hat-trick, but of bowling the entire Borley eleven in as many balls.

"The only runs they made were in the overs that I wasn't bowling," she wrote home in an imaginary letter; and woke with a start to find the sun shining, and a bell ringing violently at the end of the passage.

The first information that greeted her was vouchsafed by Milly Grubb, the captain of the Second Eleven.

"Match off!" she said, and made no answer to Sally's twice-repeated "Why?"

"Beast!" muttered the girl; but during breakfast learned from general conversation that Mabel Gosson had been right in her prophecy. Patty Dolbey had developed measles, and Frisky Harrison, her chum, was also in the sanatorium under suspicion.

"Little cads!" said one of the Second Eleven of these unfortunates. "Why couldn't they have smothered their faces in flour or something until after the match was over?"

"Just imagine if Old Cocaine had caught them powdering their noses!"

"I suppose we shall all be shut up like maniacs for the rest of the term? Sort of thing one expects during Lent, but in the summer it is awful."

There was a general groan, and then Sally heard Peter's drawl:

"I had the afternoon off to go and see my cousins at Springley Manor, this side of Parchester, you know. I suppose they will have all had measles, so I can turn up there all right as arranged. They are none of them children."

However, it was not all right. Miss Cockran made it quite clear that the entire school was in quarantine until further notice; and its inmates must content themselves in consequence with the school boundaries, unless taken for crocodile walks by a mistress. On Saturday afternoon, as there was no match, there was to be a picnic tea on that part of the shore reserved for Seascape House.

"A regular school-treat!" said Peter scornfully, her temper ruffled by a private interview with Miss Cockran, in which she had obtained no more than leave to write a note to her cousins explaining that she would be unable to go and see them.

"Why it's just a bribe to get us to be good little girls, and yet when we sit down to tea there will only be bread and butter mixed with sand and seaweed instead of eating it at tables like ordinary Christians."

The rest of the school was more resigned. After all, the shore was quite an interesting place, with rocks and pools and shells to occupy the attention, and a meal out of doors, even mixed with sand and seaweed, had its exciting side. Saturday, too, proved a perfect day, so calm and sunshiny that bathing prefects did not feel bound to send everyone out of the water after a three minutes' dip.

Sally swam well, just as she excelled in other sports; but she found it dull enough bathing alone, for, as usual, she was sent to Coventry, except for blustering threats of putting her under the water and keeping her there. These latter, of course, came from her enemies of the Fourth, led by Olive Parker.

"Let us drown the little beast," she shouted. "Here, you others, get in a ring and don't let it escape while Susy and I wash its face for it."

Without waiting for the attack, Sally plunged under water, and gripping Susy, who was the biggest of her tormentors, by the ankle pulled her after her. The next minute she was the centre of a struggling group of excited girls, who shot water over her in handfuls as she came gasping to the surface, and tried to push her down again.

"Stop it! Do you hear, kids, stop it! or I shall call Edith Seymour."

Even with this threat, it was not until she had ducked Olive Parker and shaken her that Violet Tremson succeeded in restoring some measure of order.

"You are to leave Sally alone, you little beasts, see!"

"Well, you ducked me," said Olive Parker sulkily.

"I didn't make a plan of it as if I were plotting a dirty assassination. Five to one, aren't you, and all bigger than your victim?"

Olive glared, but the rest of her friends had scattered, evidently somewhat conscience-stricken; and she herself, looking back on it, did not feel so proud of her idea as when she had first suggested it.

"I was only fooling," she said, and her furtive glance at Sally might have been construed into an apology. She was obviously ashamed.

"I have never seen you not being a fool," flew to her victim's lips, and as the words were uttered all hopes of reconciliation vanished.

"Next time I get the chance of doing you in, there will be no fooling about it, I promise you," shouted the other angrily, as she splashed off to join her fellows, leaving Sally and Violet Tremson alone, the former up to her shoulders in water.

"Why do you say those things?" asked the elder girl; "they may be smart and to the point, but they are so ... so hopeless for getting on, I mean, and making friends ... having a good time here, you know. Olive isn't at all a bad sort if you wouldn't always tread on her toes so heavily. She is older than you, remember."

"Yes, but she is junior to me in school, and at any rate she went for me first. I didn't attack her ... fact is I didn't want to have anything to say to that lot."

"She meant just now that she was sorry, Sally, and then you went and spoilt it all by saying what you did."

"I shall say what I like. I didn't ask you to rescue me, did I?"

This time Sally really despised herself for her rudeness. It had been decent of Violet to save her, but she was feeling sore over the cancelled cricket-match and all her vanished dreams of notoriety. That was why the words slipped out, and before she could mutter "Sorry!" Violet had answered with an aggravating sound of laughter in her voice:

"No! You didn't ask. You were mostly under water. Hardly in a position to do so, were you?"

"Then get out and go where someone does want you!"

In sudden flaming fury the younger girl scooped up a handful of water and flung it in her companion's face. Then she dived through a smoothly-rolling wave and came up a few yards off. Let Violet Tremson chase her and duck her if she liked; it would be no disgrace from someone so much taller. Violet, however, did nothing of the sort, but merely swam away leisurely towards a group of seniors gathered round a projecting rock.

Tea was eaten picnic fashion on the beach, at four o'clock, and Sally wandered away with hers to a flat ledge of rocks, half-way up the cliff. Above her head were the two large, almost circular openings, known as the "Portholes."

Glorious hiding-places, these caves looked; but the rock descended sheer, some six feet below them, and beneath this again was a slope of broken shale and sand that offered no sure foothold, even to the most intrepid climber. The slope was surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, with a notice affixed, forbidding anyone to try to pass it.

Sally, as she earnestly studied the lie of the land, wished that she could think of some rapid way of mounting to the caves: it would cause a new sensation, and bring her once more into the limelight that she craved. Something of this desire was evident in her expression, for a derisive voice demanded suddenly, "Going to jump up there, or fly?"

It was Mabel Gosson, of the Lower Fifth; rather a stupid giggler, but a kind-hearted girl, and a friend of the daring Peter.

"No—hardly—but I could easily climb inside, if I were let down on a rope from the top. It's no distance."

Her tone was so earnest that Mabel ceased to jeer, and even looked a trifle alarmed.

"Look here, kid, don't go trying any fool games like you did on the train. Take my word for it, that the only entrance to those caves is from Borley Chine."

"That's nearly a mile along the coast?"

"Not quite, but out of bounds, at any rate. The Chine used to be a smuggling bay, you know, and it is said there are some kegs of brandy stored under Old Cocaine's study, and that she has a private staircase down to them, concealed in her cupboard." Mabel giggled as she spoke.

"You mean there are rooms underground, all the way from the Chine up here?"

"Passages with ledges, more likely—I don't know. We have never been allowed to go there since a boy is supposed to have got walled up there, some years ago, by falling rock, and lost. He was wanted by the police, so I expect myself that he went to America instead."

"It would be rather interesting to unearth the skeleton."

"Beastly," said Mabel, shivering a little. "You are an unpleasant child."

It suddenly occurred to her that it was really beneath her dignity to chatter with a new kid in this familiar way; but to hold her tongue was almost beyond Mabel Gosson's power, if she could find a listener.

"Well, I suppose you mean to start hunting at once?" she sneered, with a sudden assumption of superiority, and prepared to walk off.

"Why not?"

"To-day?"

Sally shrugged. She was playing her usual game of creating a sensation; but her coolness was a trifle overdone, and the other girl sniggered mockingly.

"Peter," she called, "Peter, just come and listen to this. You will die of laughing."

Sally's heart beat fast, as Trina Morrison rose languidly and strolled over towards them. At last, this almost grown-up girl, whom she was determined to make her friend, had been induced to notice her; but the acknowledgment, when it came, was scarcely flattering.

"Oh! it's only the Cocky-doodle. What is she crowing for now? Made the sun rise, eh? I'm sure I don't want to talk to her."

Unexpected tears sprang to Sally's eyes as her romantic day-dreams were shattered.

"I—I didn't ask you to come," she said, with more humility, however, than defiance in her voice; and Peter threw back her head and laughed:

"No—or I guess I shouldn't have arrived. What is it, Mabs?"

"Why, the young ass over there says she is going to climb into the Portholes to-day."

"Oh, she says that, does she? Little liar—her name ought to be Matilda."

Now Mabel Gosson's version had not been exactly what Sally said, but wounded pride made her forget this.

"I am not afraid," she returned hotly.

"Oh, nor are we, for you, so don't hesitate to begin on our account. If you slip, and fall in a jammy mass, the school will hardly mourn or order funeral wreaths out of its pocket money—eh, Mabs?"

Mabel Gosson giggled. Peter often had a cruel tongue, and her slower-witted friend was afraid of it.

"She wouldn't be such an ass as to go," she said uncomfortably.

Sally glared. "I am going to get into those caves, all the same," she said; "so you needn't be so beastly superior."

"Climb on, MacDuff, and we will 'wait and see'—a case of pride and the fall, I prophesy."

Peter seated herself on the ledge of rock as she spoke, and picking up the remains of Sally's unfinished tea, munched it calmly, while Mabel sank down giggling by her side.

"Buck up, kid," she said. "Hop it, or fly; I bet you stick on the barbed wire and have to be plucked off by a prefect."

"I am not going to get in by climbing, you see."

At this there was derisive laughter from Peter, and Sally, in one of her sudden furies, caught her by the shoulder, and shook her.

"I won't kill myself just to amuse you, so there—but there is another way into the caves, and I mean to find it."

Trina Morrison was on her feet now. At first she had looked amazed and furious at the onslaught; but then, to Mabel's surprise, she merely smiled and freed herself.

"It will be out of bounds, you know," she said, in her usual drawl; and Sally nodded.

"You mean I shall be expelled, if I'm caught—Much I care! I loathe this place, and wouldn't be sorry if I never saw a single soul in it again."

"Quite so! Then you intend to commit educational suicide by trotting off to Borley Chine—do you?"

"That's my business."

"Admitted—but take a word of advice. Don't do anything so dull as to explore caves. If you must run risks in order to crow about them afterwards, just trot into Parchester, and buy me some chocolates."

Sally's breath came in a choke; her temper vanished.

"I—why, of course I will, with pleasure, if you will only ask me decently; and I have money of my own too."

She almost whispered the words; and in her eyes was entreaty—something of the look of a dog, accustomed to kicks, who would give his world for a little kindness.

Trina Morrison studied her for a few seconds, beneath narrowed lids, then she laughed, but this time without jeering. She had a very pretty laugh.

"Bless us! If the kid hasn't got a soft side, like a hedgehog unrolled," she exclaimed. And then to Sally, "Of course I will ask you decently, I might even give you a kiss, if you chose the chocolates I like."

Sally went very red. "I hate kissing," she muttered; "but I'll go. Which do you like—soft? Or hard, with nuts?"

Mabel, who had been watching the pair in amazement, now interposed, "Oh, Peter! You oughtn't to send her. She is only a new kid."

"Shut up," said Sally. Then to Trina Morrison, "Well, I'm off. No one will miss me till supper, and that's not till eight. Anyhow, I don't care if they do see me."

The elder girl smiled, catching her by the wrist, as she turned to go.

"A wrinkle from an old hand at the game you are playing," she said. "Leave your school hat-band behind the first hedge."

Sally nodded. "I shan't take it—I brought a cap of my own from home, just for this kind of occasion," she said, airily; and then, kissing her hand to the dismayed Mabel Gosson as she called out "Good-by-ee," she clambered over the rocks towards the steps.

In the school garden she met no one, though she could hear the mistresses having tea and playing tennis on the other side of the big hedge. Servants were moving in the house, but no one saw her as she crossed hall, ran up the stairs and down the corridor to her own room—No. 9.

It was empty, for the girls were forbidden to enter their dormitories during the daytime; and Sally knew that if she were caught, all chance, even of starting on her adventure, would be at an end. Feverishly she hunted through her chest of drawers for her purse, jumping guiltily, as though she were committing a theft, when a clock in the hall clanged five. Some coppers tumbled out on to the floor as she pulled the purse towards her, and Sally had only just time to gather them up in her hand when she heard footsteps coming leisurely down the passage.

Where could she hide? Not under one of the five iron bedsteads, that, without valances, and with the curtains of the cubicles well pulled back, left the floor fully exposed to view. The only other chance was the cupboard behind her, hung thick with dressing-gowns and coats; and into this Sally forced her way, kneeling doubled up, successfully concealed for the moment, it is true, but a prey to cramp, and almost suffocated by her shelter.

The someone whose footsteps she had heard entered the room, tip-toed across the floor, and stood listening; then moved a bed, and half opened a window.

"It's the Matron, bother her!" muttered Sally angrily.

This Matron was already one of her chief enemies at Seascape House; for tidiness, with Mrs. Brendan to spoil her daughters by clearing up their rooms after them, had not been enforced at home: and at school it was one of the few things in which Sally did not seek to excel. "I thought putting things in order was your business, not ours," she had said rudely, when first called to account for a bed heaped with odds and ends of ties, handkerchiefs and gloves; and Miss Budd's heavy figure had heaved with indignation, while her cheeks purpled at this piece of impudence.

"Any more disobedience or rudeness, and I report you at once to Miss Cockran," she had said with finality; and Sally guessed that now that moment had come. She did not look forward to the interview, for Old Cocaine, though small and pinched, had penetrating grey eyes, which she did not care to meet, unless there were some big piece of mischief that she could brazen out, and so, perhaps, arouse astonishment or interest in their depths, instead of pity or contempt.

Very carefully she shifted her position, and tried to part the coats and dressing-gowns, so as to give herself a little air, and view the room. Unfortunately, in doing so, she forgot the coppers clasped in her hand: as she caught at the coat in front of her, they fell in all directions; one or two inside the cupboard, but the rest on the floor outside. It seemed to Sally weeks before the last halfpenny struck a wall, and subsided noisily under a chest of drawers.

"So that's over—and the fat hag has caught me finely," she told herself, and pushing the clothes aside, stepped out with a sullen frown, into the room.

"My good child, are you trying to play hide-and-seek? And if so, whom with? You will never get to Parchester at this rate." It was Trina Morrison's drawl, and with a gasp of relief, Sally realised that she was the intruder.

"I—I—made sure that you were Matron," she said limply.

"We may both thank our stars that I am not; but on this occasion I will let that insult pass. Tell me—were you really intending to go into town, or only bluffing?"

"I was going, of course—I mean, I am going. You see, I have a ten-shilling note Mother gave me before I left, besides my pocket money. I will buy you some really decent chocolates."

"Nice kid!"

Peter's voice was at its softest, and her hand, laid lightly on the other's shoulder, became a caress.

"I am not going to try and stop you, but—

"It's no use trying to stop me—I told you."

"Well, let me make a suggestion, then—it is this. Why shouldn't I come too?"

Sally clasped her hands tight, and her eyes shone.

"Together, we might astonish the school," she said solemnly. "I have always felt it, and longed to know you."

Trina Morrison laughed. "Quaint kid, would that be a great deed?" she asked. Her twinkle, and the derision in her tone, pricked the bubble of Sally's vanity, making her all at once feel very young and silly.

"Why are you going, then?" she demanded a little sullenly, and again the other laughed.

"Not to astonish the school; that's certain. Why, my dear young ass, don't you realise that if we are expelled we shall not be allowed to contaminate the rest of Seascape House, even as a ten minutes' variety show?"

Sally glowered, as her vision of creating a super-sensation in the hall or class-room faded.

"Anyhow, I'm going..." she began.

"Well, for goodness' sake get a move on, then, and don't argue about the why or wherefore. Isn't it enough to want to do a thing to make it worth while? We had better separate, I think, and meet at the third elm by the corner of the road, opposite Marston's cottage. I shall go by my own private road, and wait five minutes, to see if you've been caught or not..."

Sally nodded. "Right oh!" she said carelessly. "I shall be there."

But beneath her studied lack of enthusiasm was a joy she had not felt since she left home. Once again she had triumphed, and the only girl whom she admired out of this horrible school had chosen her for a friend. Fortified by the idea of this companionship, she left the dormitory boldly, and ran downstairs, concealing herself behind the large hall door just before Miss Cockran swept through it from the front drive.

After this, hours passed, it seemed, though in reality it could only have been a few minutes, while the Head-mistress sorted her letters from amongst the newly-arrived post on the table, and disappeared, reading them as she went.

Sally made a face at her vanishing back, fled across the hall, as she heard Miss Rogers' voice in the garden, entered the dining-room, at this time deserted, dropped out of one of the open windows on to a flower-bed, and took refuge in the shrubbery across the nearest path. To negotiate the grounds after this was simple—merely a doubling backward and forward to shelter her movements with bushes and undergrowth—and then a bold walk out through the gates on to the high road.

Trina Morrison was seated in a dry ditch, leaning against an elm, at the corner of the road, opposite a thatched cottage.

"I was just giving you up," she drawled, looking at her wrist watch. "I made certain Matron had got you this time."

"Not she.... I dodged Old Cocaine too, and Proggins ... you would have laughed."

And Sally launched at once into her favourite subject of her own prowess; but only to break off angrily, as she noticed Peter yawn and pause to pick some ferns.

"Why, you are not listening!"

"I am not amused.... Like Queen Victoria, we never listen when we are not amused—I didn't know you were such a kid."

"I am not a kid—in brains, I mean. Why, I am top of the Remove—easily, too. I shall be in your form next term."

"You might become top of that, and still be a boresome child."

Sally stared at her blankly, and the retort "What rot!" died on her lips. Perhaps Trina Morrison was right. Sally knew that she was nearly bottom of the Lower Fifth, and yet, compared with Cecilia, who was grown up, she was a woman of the world.

"How am I such a kid?" she mumbled at last; and there was real humility in the question.

"You boast like a five-year-old—and do nothing but talk about yourself, when, Heaven knows, the world is full of more interesting subjects. Then you have no self-control, but if any one laughs at you, your temper blows up like a powder magazine."

The directness of this attack, and the cool indifference with which it was delivered, left the younger girl dumbfounded. Cecilia had often levelled the same accusations, but they had never before struck Sally's inner consciousness with any conviction of truth.

"You ... you aren't being fair to me," she muttered; and then relapsed into complete silence, as she realised Trina Morrison did not care in the least if she were fair or not—nor whether her words hurt her listener. Quite unconcerned as to the effect of her speech, she strolled along with her hands in her pockets, until they came to some cross roads, when she took a turning to the right.

Sally caught her arm, and pointed to the sign-post.

"Why, Peter, look, it says straight on to Parchester,"

"Well, I'm not going to Parchester, you see."

"Then where are we going? I don't understand."

"I happen to be going to call on my cousins at Springley Manor. They asked me to tea to-day."

She may have laid a slight emphasis on the "I"; Sally, at any rate, found herself flushing, as though she had been guilty of thrusting her company where it was not wanted.

"I had better leave you, then," she said gruffly. "My way is in the other direction." She turned back, with her shoulders rather humped, and her mouth curved in sulky lines. This friendship was not developing as she had hoped.

The next instant a hand rested on hers, and she heard the soft drawling voice she found so full of attraction.

"Silly kid," it said. "Why, of course, you are coming with me. We will wangle some chocolates out of my cousins, instead of stealing your ten shillings."

After this, the walk was bliss for the younger girl, though she found it hard work to refrain from boasting or talking about herself. One thing she did relate, and that was the story of the goat that she had tied up in the parish schoolroom.

Trina Morrison shouted with laughter: indeed, they were both making so merry over the recital that a car, following them up the side road that had now become a mere country lane, nearly ran them down.

"Why the dickens can't you two girls look where you are going?" shouted an angry male voice, and then broke off abruptly, while the car, which had slowed down, stopped.

"My stars! If it isn't Trina. I understood from the mater that you were laid low, fair cousin—veiled in spots, in fact."

"Not yet; so I decided to look you all up as I got bored with playing at Margate, or Blackpool, on the shore this afternoon. You are just in time to give me a lift, Austin."

"With pleasure."

He opened the door beside him, and then looked hesitatingly at Sally. "Who is the kid?" he whispered. "Where does she come in?"

"Why, behind, of course; that is, if she is not afraid of your driving. Let me introduce Miss Sally Brendan—my cousin, Austin Ferrars, who has nearly killed us. Sally was trudging into Parchester to buy me some chocolates, so I brought her here instead, as I know you always have a supply."

"One of your slaves, eh?" he half-whispered, lifting his eyebrows and smiling; and Sally, who overheard him, found her heart beating fast, as she listened for Trina's answer. Yesterday she would have been furious at the insinuation, but now she waited for an acknowledgement, even, of her existence.

The answer was, as usual, unexpected.

"No—not my slave—merely a friend," Peter said smoothly. Then, "Do get in quick, kid—we shall only have about half-an-hour we can stop, as it is."

It seemed to Sally that the car flew over the ground, and soon they were the centre of a group of people drawn from the neighbouring tennis court by the honk of the motor as it slowed up in front of a low ivy-covered house. On all sides there were exclamations of astonishment, and some mild scoldings from an elderly lady, whom Trina called "Aunt Edith."

"Why, child, I don't understand this. I only got a note this morning saying that you were unable to come."

"That was dictated by Miss Cockran. This is my own answer."

There was a roar of laughter from the younger members of the party at this impudent assurance; but Aunt Edith shook her head.

"I am always glad to see you, Trina, as you know; but I don't always approve of your behaviour," she said, with some severity—on which her niece put her arms round her and kissed her.

"Love me, even if you don't approve of me," she said lightly, and then to Austin—"What about some chocolates?"

She disappeared after him into the house; and Sally, who had dismounted from the car, was left standing forlornly in the drive, until an old gentleman took pity on her and suggested that she might like some tea.

She agreed, and was soon seated near the tennis court, enjoying iced cake and strawberries and cream.

"So you are a pair of runaways?" said the old gentleman at last, fixing his pince-nez, and staring down at the girl beside him.

"Yes—you see it's so dull at school. Peter, that is Trina, you know, had been growing bored stiff this term, and I'm just the same."

"H'm! Trina is a very wild girl, I'm afraid."

There was condemnation in his tone, and Sally answered indignantly, "She is an absolutely wonderful person—you couldn't expect her to behave like ordinary people."

She did not realise that it was almost the first time she had praised anyone else whole-heartedly and without condescension; she only knew her anger was rising steadily as her companion continued with a shrug:

"Oh, she has charm all right, I grant you—but she's selfish, confoundedly selfish—so if you haven't found it out already, be warned, my dear, by one who has known her since she was a baby."

"She isn't selfish—not a scrap. Why, she wouldn't let me go into Parchester this afternoon and buy her chocolates."

The old gentleman smiled at the vehemence of this reply.

"Dear me! Dear me! Wouldn't she let you do that?" he murmured. "It was very thoughtful of her;" then added drily, "but she seems to have got some chocolates—all the same."

As he spoke, Trina Morrison appeared on the tennis lawn with her cousin and some of the other young members of the party. She was munching sweets out of a box and talking excitedly. Sally thought how pretty she was, and admired the ease with which she parried the jokes of the teasing group round her.

"A flying visit, I fear, Uncle Tom," she said, coming up to the old man. "Austin is going to run me back in his car."

"By rights I should go too, and inform Miss Cockran that we have been no party to your misdeeds."

His tone was grim, but his niece merely laughed.

"Dear Uncle Tom," she said lightly, "picture your awful half-hour, while Old Cocaine told you my faults, till you rose in righteous anger at an attack on the family and defended me. Besides, you wouldn't be a spoil-sport."

He turned away with an impatient movement, as Austin broke in eagerly:

"Dad thinks as we do—that it's jolly plucky of you. But, I say, must you go yet?"

"I'm afraid so. Lend me your big coat, do—and I will drive. Good-bye, Uncle Tom—good-bye, Aunt Edith. Next time I'll come for a night, if you will arrange a dance."

Sally thought that the grown-ups near her were not exactly pleased at this casual farewell. Indeed, one lady said discontentedly, "Why, it's too bad!—Austin going off again like that. He promised to make up a set directly he returned from the station."

"He seems to have forgotten that," returned someone else. But by this time Sally was running over the lawn, towards the car, whose engine had begun to throb.

"Aren't you going to take me?" she called; and those standing round laughed—including Trina, who answered calmly:

"Of course, but I had forgotten you for the moment, kid. Here, hop in behind, and have some chocolates."

"She had better put on this coat."

It was Uncle Tom speaking, and as he helped the young girl into its ample folds, he whispered, with a jerk of his hand towards the driving-seat—"Don't trust her too much, child, or she may lead you into Queer Street."

"She landed me here," said Sally coolly; and in spite of the shock caused by this rejoinder, Uncle Tom burst out laughing.

"Bless me! I believe you can look after yourself all right, and I needn't have worried," he said, as he slammed the door; and he turned back into the house without waiting to watch them go.

"What was it Uncle Tom said to you just now?" asked Trina sharply, as they turned a corner of the drive that shut out the house from view; and when Sally told her of his warning and her own rejoinder, she laughed so much that the car swerved, and nearly carried away a gate-post at the end of the drive.

"Poor old Bean!" she said. "Did you hear that, Austin? He must have had the shock of his life."

Her cousin, who was trying to take the steering-wheel from her, did not look altogether amused.