Title: War paint

Author: Robert Winchester

Illustrator: Ralph Frederick

Release date: October 21, 2025 [eBook #77102]

Language: English

Original publication: Chicago, IL: The McCall Company, 1929

Credits: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

A right diverting tale of sudden love and battle down on the Texas border, by the competent writing-man who gave us “My Deputy” and “No Flyer Ever Lost.”

The two lean-bodied Texas rangers stood on the sidewalk of Wirton’s main street, their thin, bronzed, grave young faces immobile, watching the girl who had pulled up to the curb in a long high-powered roadster that carried a New York license.

“Doggone,” said Sam Earp, plaintively, “I sure wish Ma was along so’s she could see it. Ma’s been reading herself a lot about these new kind of girls, and she don’t believe it a-tall. Hot damn, boy! Look at her puttin’ her war paint on. Reckon she’s goin’ to hold up the bank, Bud?”

Bud Yancey grinned. “She’s a right pretty girl even if she does—my gosh, Sam, maybe-so she heard us?”

The girl calmly powdered a very pretty straight little nose, touched her red hair with a dainty hand in one or two places, looked at the general result in a little mirror, took out a lipstick, worked on her lips for a moment, looked again in the mirror—then snapped her compact shut, got out of the car and walked directly up to the two young rangers.

She wasn’t more than nineteen, and her graceful, exquisitely proportioned slim body, in its silken sheath, was the very heart of youth. Her eyes, dark gray-blue, surveyed the luckless pair, starting at their feet and slowly rising until they reached the eyes of the now much embarrassed Messieurs Yancey and Earp.

They lingered on the heavy cartridge-belts, from which hung the holstered revolvers, then once more came level with theirs, and she asked, sweetly: “When does the rest of the circus come to town?”

They both knew then that there could be no further doubt as to whether she had heard them or not. She had—and was going to give battle.

“Well suh,” grinned Sam Earp, “it aint plumb certain just what time the rest of the outfit does get in, is it, Bud?” Now that active hostilities had started, they both felt better.

“That’s right, it isn’t,” agreed Bud. “You see,” he went on gravely, his keen young black eyes, with the tiny wrinkles at the corners already forming from gazing over the hot shimmering desert, intent on hers, “there was a right bad accident happened to the lion over yonder in Laredo, and it might delay them. Were you waitin’ to see the show?”

“Yes suh,” said Sam Earp, “I don’t figure that lion will ever be the same again, will he, Bud?”

The girl’s beautiful eyes had widened quite a little when they so readily took up the circus gibe, which she had meant as a double-barreled insult, in payment for the words: “I wish Ma was along to see it.”

“Why—I don’t believe there is a circus at all,” she said, “and—”

“What?” interrupted Bud sorrowfully. “Doggone, Sam, this here girl doesn’t believe there is a circus! Don’t you believe in Santa Claus, either?” he asked anxiously.

Miss Elaine Norcross Webb, only daughter of Charles P. Webb, New York and Newport multi-millionaire, with yachts, country-houses and all that goes with them at her disposal, had never been referred to before, at least within hearing, as “this here girl.” But having fighting blood herself, she rallied quickly.

“What happened to the lion?” she asked, just as gravely as Bud.

“It’s a right sad thing,” answered Sam Earp slowly. “He was—what was he doing, Bud? You were around when it happened.”

“It was this-a-way,” said Bud, a look of scorn in his eyes as they dwelt a moment on the uninventive Mr. Earp. “That lion had a right bad habit of trying to climb the tent-pole backwards, and every time he got out, he’d—”

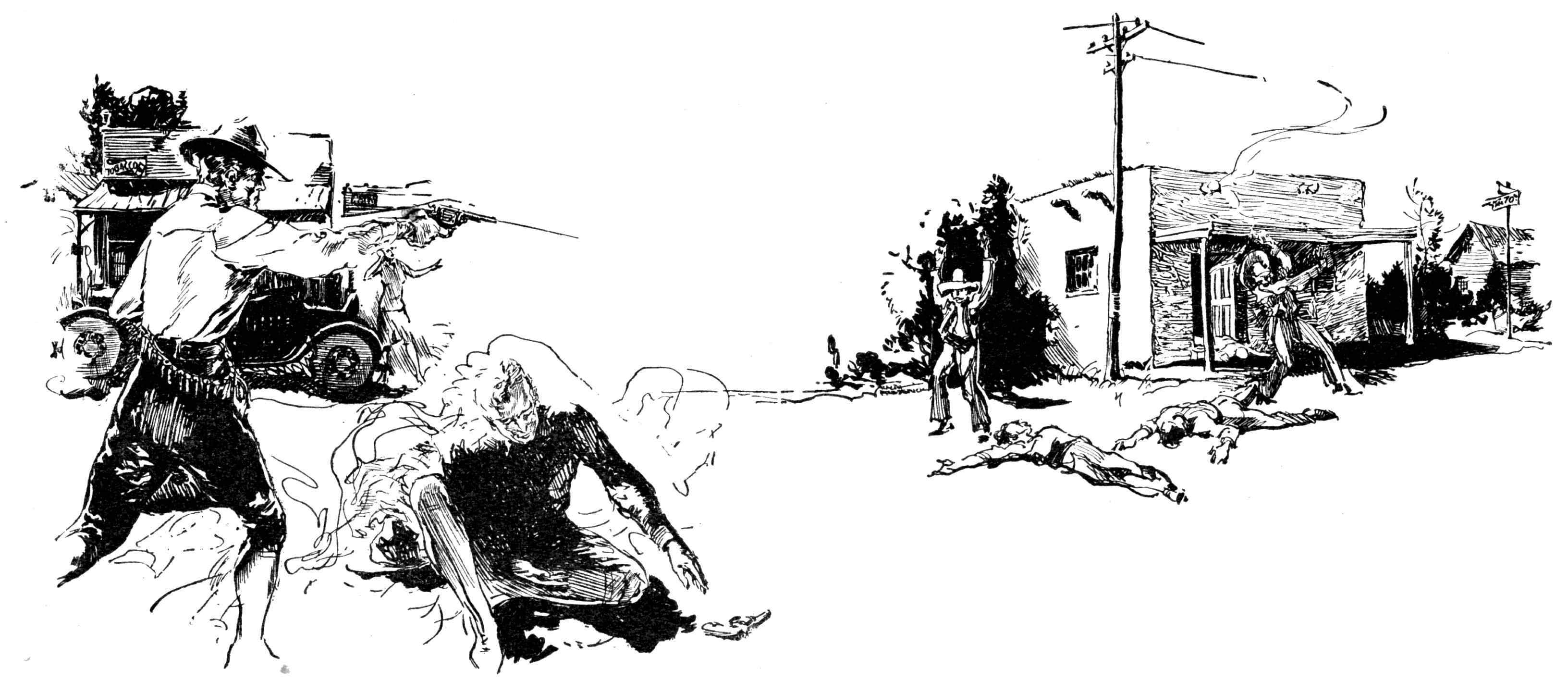

The muffled sound of two shots came from the adobe house next to the bank; the door crashed open, and five Mexicans ran out. They turned at the edge of the sidewalk, and as a white man staggered from the doorway, an old single-action .41 in his hand, they raked the doorway and the windows of the house with a stream of lead. The white man pitched forward on his face, and the Mexicans started to run up the street directly toward Elaine and the two rangers.

She had just time to see the faces of Bud Yancey and Sam Earp suddenly become grim and cold before she felt Bud’s arm close around her waist, forcing her to her knees behind him.

“Lie down,” he commanded, no trace of a drawl now in his voice. Then she saw them run to the middle of the street, guns materializing in their hands as if by magic. There was a quick flurry of shots that came before she could get on her feet, which she promptly did, in spite of the command to get down.

Two of the Mexicans lay in the street; one was retreating toward the corner, firing as he went; one did not attempt to do any fighting but ran swiftly to the corner and disappeared; the other stood still, his hands above his head. Sam Earp was sitting in the dusty street, the right side of his face a blur of blood, his right arm hanging limp, and his left hand reaching for his gun, which had dropped from his hand as a bullet had torn through his wrist.

Bud Yancey stood erect, his heels together, swaying a little as the red splotch on his soft white shirt up near his shoulder widened. Elaine could see the frozen-looking little smile on his lips, and his eyes, now as cold and wintry as northern ice in the gray of dawn. The Mexican fired twice, then as Bud’s weapon rose and fell, whirled around as if hit by a giant fist, his knees gave way and he sank slowly to the ground.

A mild-looking old man had stepped out of the bank next door at the first shot, a revolver in his hand, the butt of which was notched in several places. He watched the fight, making no attempt to get in it. When it was over, he sheathed his gun in a holster under his left armpit and walked over to where already men were bending over Sam Earp and Bud Yancey, now lying across Sam.

The old man talked a moment with the men who were lifting Sam and Bud in their arms, felt gently Sam’s wrist and head, opened Bud’s shirt a little, gave a curt order and started back toward the bank. He saw Elaine standing there, one lovely hand over her heart, and came up to her. “Honey,” he said in a soft disapproving drawl, “you-all mustn’t get up when men-folks are gunfightin’. Next time you-all keep down—like a right good girl should.”

“Next time!” gasped Elaine. “I—it happened so quickly, and—”

“It does that-a-way down here,” the old man said, a twinkle coming in his calm blue eyes, “every once in a while.”

“Are they—is he—oh, he stood there with a smile and—is he badly hurt?”

“If you-all mean that wuthless young Bud Yancey,” answered Ranger Captain Coudray, “no, ma’am, he isn’t. Neither is that scoundrel of a Sam Earp.”

She had been referred to as “this here girl” and had been told to act as “a right good girl” in the course of five minutes, but she decided right then that she would defer for a day or so arriving at the army post where her brother was stationed—at least until she had heard more about the accident to the lion, and—found out that Bud Yancey was not really badly hurt.

“I was going into the bank to get a traveler’s check cashed,” she explained, “and they were talking to me when it happened. I’m Elaine Webb, and my brother is Lieutenant Webb, stationed at Fort Combes.”

“Well suh, I know him right well—and I knew your daddy’s brother when he was soldierin’ down here a long time ago. My name is Coudray, honey. I’m kinda the boss of them two jaspers I caught gun-frolickin’.”

Elaine looked at the famous old ranger captain that her brother had written about when telling of men and ways in Texas.

“Honey, after you-all get through at the bank, I sure would admire if you’d come home with me and meet up with the best lookin’ girl in Texas. Mrs. Coudray don’t get out much nowadays, and she loves young people, specially right pretty ones.”

Elaine smiled. “I’d love to. I didn’t want to go until—are you sure he isn’t hurt very much, Captain?”

“That Bud Yancey isn’t hurt hardly a-tall,” answered the old Ranger. “Honest Injun. You go and ’tend to your bankin’, and then come home with me. Ma’ll take you over to the hospital this evenin’, I reckon.”

“Why, I don’t want to see him,” Elaine hastily declared. “I—just wanted to know that—”

“I know you don’t, honey,” drawled Captain Coudray, a twinkle in his eyes. “There aint a nicer boy in the State. He’s got him a mighty good range, too. Some day he’ll have his company, I bet you.”

“I don’t see why you are telling me,” Elaine said haughtily. “I haven’t the slightest interest in—either what he is or what he has!”

“Yessum,” said Ranger Captain Coudray, stepping aside so that Elaine could precede him in the bank, “I’d bet me a lot of money that you—”

Elaine hadn’t waited to hear the rest of it, but with her patrician little nose well in the air was halfway to the banking counter.

Lieutenant John Webb was standing in front of a long glass frankly admiring the fit of a tunic on which was spread the silver wings of a flyer. “Hey, Lainy,” he said, without turning around, “is that a wrinkle up there by the collar? Come on over and take a look.”

“It isn’t,” answered Elaine lazily from the couch. “I can see from here. Boy, it fits you like the paper on the wall. I can—”

“You can like fun. Get off’n that couch before I come over and trun yez off. This is an important matter.”

“Oh, for Pete’s sake,” said Miss Webb inelegantly. “I’m halfway through this story, and what between you and the rest of the infants around here asking me how their uniforms fit, I’ll never finish it. It isn’t a wrinkle, I tell you.” But she rose just the same and came to the mirror. “See,” she went on, “it fits smooth—except right here.”

“Ouch! Quit it, you darn’ monkey! Gee, you shouldn’t tickle anyone like that without warning. I’ll—”

“Take that in payment for making me get up,” answered Elaine. “Jack, did you ever meet this Bud Yancey I told you about?”

“No, not Bud. I’ve met Jimmy and Wes—they’re his cousins, I guess. All the Yanceys down here are related. Man, you ought to see Jimmy’s sister Betty. She’s one lovely piece of work. I’ve seen ’em under every flag that flies, and she’s the starweno.”

“Yes?” scoffed Elaine. “So you have fallen for a Texas beauty after all your fussiness? Remember who you are, young feller.”

“That’s just it,” answered her brother. “I got as much chance as a jackrabbit, ding it.”

“What! You—a Webb—and you haven’t any chance? Does she know who you are, darling?”

Her brother eyed her suspiciously. “What are you trying to do—kid me?” he demanded. “The Yanceys were cattle barons and governors of Texas back in the days when the Webbs were running around barefooted peddling fish, you poor prune! Money doesn’t count for anything down here. It’s what you weigh and how you can stand up to it in Texas—”

“Down by the Rio Grande,” sang Elaine gayly. “So the proud and haughty Yanceys scorn the poor Webbs, do they? Never mind, Johnny; we’ll make them—”

“I’ve told you nine million times not to call me that,” said her brother hotly. “I’m going to try out that new 5N bus that came in this morning. Want to go along?”

“Not I, my darling,” answered Elaine, stretching luxuriously. “It’s too hot, for one thing; and—”

“I dassen’t, for another,” jeered her brother from the door. “Stay there and get fat, then.”

“Stay here and keep all in one piece, you mean,” called Elaine to the retreating back.

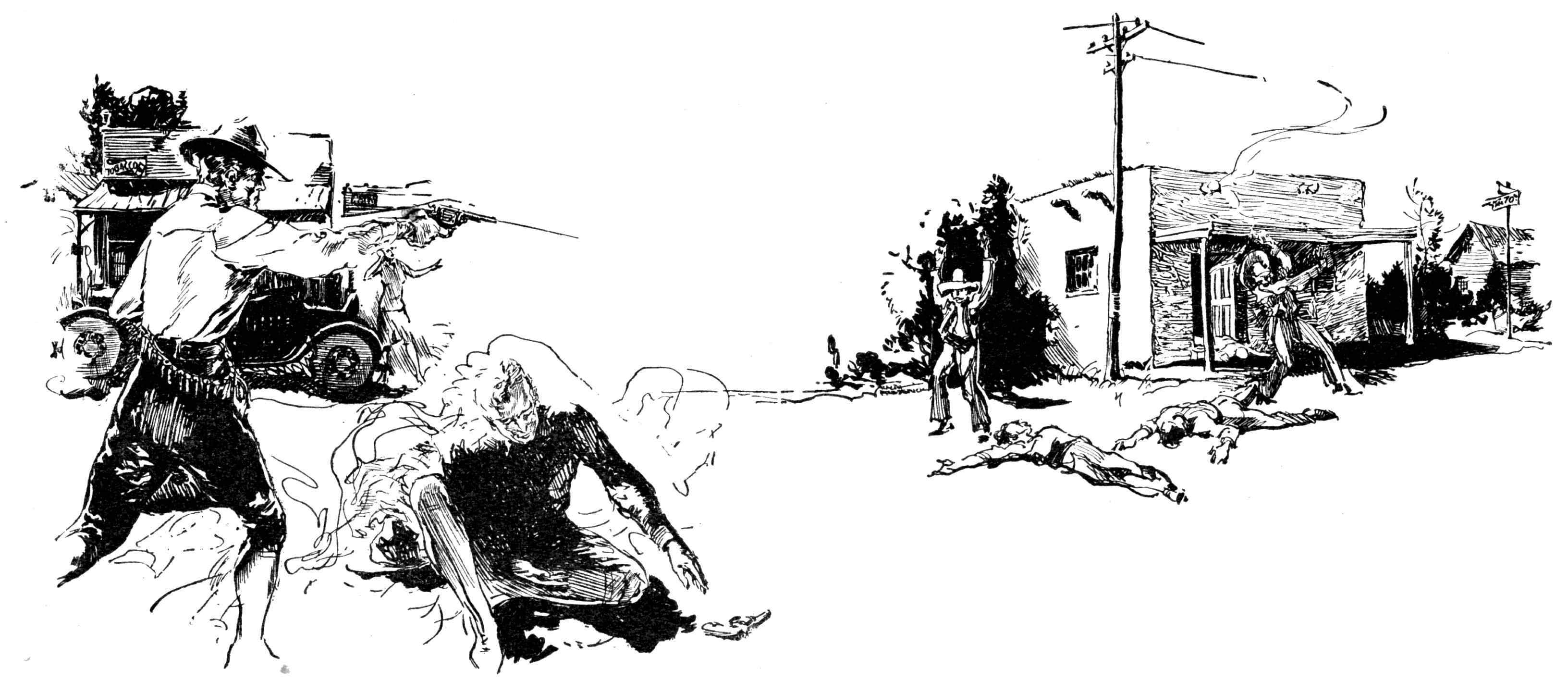

But about an hour later she decided to go down to the flying-field after all and at least watch her brother try out the new 5N. He was in the air when she arrived, watched by quite a group of officers and “kiwi.”

“Hullo,” she was greeted by a young captain. “Come on over here and sit down. That brother of yours is trying to break his fool neck. He’s been doing barrel-rolls and flying on his back while he’s resting. I’ll bet that bird he’s got up with him wishes he’d stayed on the ground. Anyone that would go up with Jack Webb when he’s testing out a crate is as crazy as he is.”

“He asked me to,” said Elaine, sitting down. “Who is it he has up with him? Must be someone that doesn’t know him very well.”

“I dunno,” answered the captain. “I wasn’t here when they started. Some lad said it was a ranger named Yancey.”

“What?” said Elaine, sitting up straight. “What Yancey? Was his—I mean is his name—Bud Yancey, Billy?”

“Whadda you care?” asked Captain William Carter with a grin. “His name will be mud if he monkeys around flyin’ with Jack, very much. Oh, ho! You’re the reason we are honored with the presence of a ranger, are you? How-come Jack wants to kill him? Doesn’t he approve, Lainy?”

“Don’t be any more of a fool than you can help,” answered Elaine crossly. “I just—my goodness, look at him!”

The great plane came roaring down in a tight spiral, to straighten out, skid, then side-slip to reduce the excess speed, the field being a small one. However reckless her brother acted in the air, he was cool enough to make a perfect landing and bring the plane to a stop within ten feet of where Elaine was sitting. As he crawled out of the cockpit, he was followed by Texas Ranger Bud Yancey, whose tanned young face seemed a little paler than usual, although as immobile and grave as ever. “I’m right much obliged to you,” Bud said, holding out his hand to Webb. “That was sure a ride. I reckon from now on, though, I’ll take mine forkin’ a bronc’.”

Elaine arrived, with battle showing clearly in her eyes. “John Webb,” she began, “what do you mean by taking anyone up with you when you’re trying out—”

“Aw, go on,” her brother grinned. “He wanted to go. —Didn’t you, Bud? Tell sis about it.” And he beat a hasty retreat.

“Bud Yancey, you come over here and sit down this minute. The very idea—and you not out of the hospital a week. You should have better sense,” Elaine scolded, leading the grinning Mr. Yancey firmly away to a quiet corner near one of the hangars.

“I always wanted to go up in one of those things,” he protested, as they sat down, “and I’m all right. Last time you-all came to see us, the doctor said that—”

“I don’t care what the doctor said. You shouldn’t—”

“Honey, don’t jump on the old man that-a-way while he’s plumb dizzy. You-all be a good—”

“What did you call me?” demanded Elaine, her lips tightening.

“Darlin’, how can I tell what I’m callin’ anyone, after gettin’ rolled around and around way up yonder?” asked Bud sorrowfully. “Ask me sometime when I’ve right good sense. All I know is that I’m sittin’ here with you. A jasper told me one time that when a man gets as dizzy as the dickens, he always says what he thinks.”

Elaine eyed him with a good deal of hostile suspicion. “You’re a fraud,” she declared, “and—”

“No, I am not,” interrupted Bud. “My head is clearing right fast now, and I remember. I came all the way over to tell you that after you’d been to the hospital the second time, I decided that you were.”

“I was what?” asked Elaine.

“What I called you when I was dizzy,” explained Bud with a grin.

“Well,” said Elaine grimly. “I can still see that you are as dizzy as the dickens, like you say. You better come right up to John’s with me, and let Chi-sui make you something cool to drink. You are still awfully dizzy, Mr. Bud Yancey. Come on.” And she slipped her slender little hand in his, much to the disgust of several young officers hovering around in the background. On the way she asked: “That day in Wirton—what did those men do, that you—were they trying to rob the bank?”

“No, they were some of Garcia’s men from across the line. Reckon they had a deal on with old ’Pache Brown. He’s more or less tied in with those jaspers. I mean he was,” amended Bud, with a grin.

“Then why did they try to kill him?”

“Well suh, I don’t figure they did aim to do that. Maybe-so it was the other way around. Old ’Pache was right apt to reach for a gun if he got fussed up, and it never took much to start him that-a-way. He may have thought they was holding out on him.”

“Well, wont this Garcia try and—and do something to you and Sam Earp, Bud?”

“Yessum,” answered Bud cheerfully, “I reckon he will. He’s been trying to do something to us for a long time. Not only us, but the Border Patrol gents also.”

“You seem to think it’s funny,” said Elaine hotly. “My goodness, don’t you care at all whether you get killed or not?”

“Darn’ right I do,” said Bud promptly. “I don’t want to get killed a-tall. Especially now.”

“Why especially now?” asked Elaine, as they started up the veranda steps. If she had thought to embarrass Mr. Buford Yancey with that question, she woefully failed. Mr. Yancey was always ready to give a direct truthful answer to an equally direct question.

“Because,” he said, halting on the top step and turning so as to face the very pretty little Miss Webb, “I’ve fallen in love with you, and want to live a long time after we are married.”

“What!” gasped Elaine. “You’ve—after we are married! Well, Mr. Bud Yancey, you’ve got a long, long time to live before that ever happens. Why, you’ve only known me about three weeks! How do you know that I—”

“I don’t,” interrupted Bud sorrowfully. “That’s just what is keeping me dizzy. Do you reckon that you—”

“No, I don’t,” said Elaine, interrupting in her turn, “and furthermore, I think you better sit right down here on this step until you get less dizzy, Mr. Yancey.”

“I’ll have to,” said Bud, as faintly as possible. “Better have that Chink hurry with the drink; I’m getting worse.”

“Here he comes now to see if we want anything. I think you are much too dizzy to have anything put in yours, either. You’ll get lemonade, plain.”

“My gosh!” said Bud, sitting down. “I sure wish you hadn’t asked me that question.” Then, being young and gay and happy, they both laughed and Elaine sat down beside him.

Two weeks later Lieutenant Webb, his right arm in a sling, a bandage around his head, looked up from where he was lying on the living-room couch. “Where the dickens have you been?” he demanded as Elaine came in.

“I got here as soon as I could after I heard about it,” she answered, coming over and kneeling by the couch, kissing him. “What happened, Johnny? Are you badly hurt, tell me! Darling, you should be more careful. Did you break your arm?”

“Who, me? I should say not. I keep it this way because it’s cooler and—”

“John Norton Webb, you answer me! What happened, and how badly are you hurt?”

“Aw, I’m not hurt at all. Quit fussin’ at me. I tried out a bus this morning, and when I landed her, the undercarriage came away, and I washed out, that’s all.”

“And got a broken arm and a—is your head bad, Johnny?”

“No, only a scratch, honest and truly, no foolin’. Where you been?”

“Up on the Lazy W Ranch to see Ma Earp. Bud took me up there. I met Betty Yancey, Jack.”

“You did! Isn’t she a bearcat? Listen, Lainy—put in a good word for me, will you? You know, tell her what a noble guy I am, and what a swell husband I’d make, and—”

“I wont—do your own horn-tooting, young feller. Oh, Jack, you’d love Ma Earp. She’s—”

“Where do you get that ‘Ma’ stuff?” demanded her brother.

“Everyone calls her Ma,” defended Elaine. “Bud asked me to.”

“And that reminds me,” said John sternly, “how-come you running around all over the lot with that darn ranger? Hasn’t he got any rangering to do at all? Whenever I asked where in the dickens you were, someone says, ‘Why, she just started with Bud Yancey for Gafoozalum or Doflicker, or some place.’”

“Why, darling,” answered Elaine, trying to look surprised, “I just wanted to see if a Webb could make a Yancey—like them. It was on your account I have been doing it, Jonathan.”

“Yeah? You fool around with these birds down here, and you’ll wake up married.”

Elaine laughed. “Don’t worry, Jonathan; I can take care of myself.”

“That’s what all you darn’ flappers think,” said John, whom enforced idleness had made rather fussy. “But how’d you like Ma Earp?”

“Oh, she’s a duck. She’s about eighty, and she was here when there were Indians and outlaws and everything. She sits up there on the big ranch, Jacky, and bosses them all—all the Earps and the Yanceys and everybody. She’s the prettiest old thing with silver hair, and her eyes are just as black and snappy. You should have seen her look me over when that darn’ fool of a Sam Earp and Bud took me in to her.”

“Why darn’ fool?” lazily questioned her brother. “Go and chase up Chi-sui, will you, Lainy? I want him to find my pipe.”

“It’s right on the couch beside you, dumbbell,” answered Elaine with sisterly candor. “Why, he said, ‘Ma, you-all claimed there wasn’t no such animal like you-all been readin’ about. Me and Bud, here, caught us one down in Wirton and tamed it a lot so we could bring it up here for you-all to look at.’”

“Yeah? What did she say?”

“Well, first she said to them: ‘You young scoundrels, go on away from here right now, you hear me?’ And honest and truly, they both did.”

John laughed. “Then what, Lainy?”

“Why,” Elaine admitted, “she told me to sit down, and she asked me a lot of questions, and—”

“Hard ones?” grinned her brother.

“Some of them,” Elaine confessed. “And then she told me to open my compact and show her how I used the rouge and the powder, and she asked me what I did it for—being a right pretty girl. And when I told her all girls did, she—she just snorted; that’s the best way I can describe it.”

“I’ll bet she did,” said John, delighted.

“Well, anyway, she did—and then we talked some more, and when I was going she called me over and kissed me, and said: ‘Sugar, you’re a right good girl and a smart one; you can’t fool me a-tall.’ And she went on to say,” continued Elaine, with a boyish grin, “that she’d heard a lot about that poor fish of a brother of mine that was shining up to Betty Yancey, and from all she had heard he was—what was it she said? Oh, yes, that you were a no-’count scoundrel of a flyer, and—”

“Go on, now you’re romancing. Go and make me a glass of iced tea, will you, Lainy? Spike it heavy with corn licker.”

“I’ll make the tea and spike it light, if at all. Corn licker and flying don’t go together, me lad.”

“Aw, have a heart,” complained John to a very pretty back disappearing in the direction of the kitchen.

Elaine stopped her car on the comb of a hill and stood up.

“Bud,” she said solemnly, “I think that’s the most beautiful view I’ve ever seen, and I’ve been in Switzerland and—Bud Yancey, are you listening to me?”

“No,” answered Bud, from his seat beside her in the roadster, “I’m watchin’ something.”

“What?” demanded Elaine, sitting down again and turning so that she could see in the direction Bud was looking. “Where? Show me, Bud.”

“Over there on the left. . . . No, follow my finger. See, way over there just the other side of that bunch of chaparral—”

“What, Bud? What is chaparral?”

“Oh, my gosh! That bunch of—see, that thicket over there. That’s the line and—hot damn!”

Elaine saw what he was looking at, just as little white puffs of smoke went floating up from the chaparral.

She saw what looked to be several men on horseback burst out of it, heading south. A moment afterward she could just barely see two men come out on foot, go to where there were two horses, get on them and ride along the west border of the clump.

“That’s Sam and Bill Earp, darn their onery hides!” announced Bud. “Sneakin’ off on me this-a-way!”

“What? How can you tell from here who they are? I can hardly see them. What were they doing? Bud Yancey, you better come out of it and tell me.”

“Shucks,” said Bud, his eyes still on the two men, “I can see them plain enough. Those darn’ jaspers must have got a tip that something was coming across. Wait till I meet up with those polecats, goin’ off like that without me.”

“Did you hear what I said?” demanded Elaine. “I am not accustomed to having my questions totally ignored, Mr. Yancey. What were they doing down there?”

“I just told you,” answered Bud. “Some gents were trying to get across the line, and Sam and Bill Earp stopped them—that’s all.”

“How lucid!” said Elaine hotly. “What a word-painter you are! Some gents were trying to get across the line, and Sam and Bill Earp stopped them, that’s all,” she mimicked. “That tells a lot, doesn’t it?”

“Doggone it,” answered the surprised Bud, “how else can I tell you?”

“It isn’t what you tell; it’s the way you told it. You tossed it out at me like a—like a—the way you would a bone to a dog. Who do you think you are, to talk that way to me? I’m not—”

“For Pete’s sake,” interrupted the still surprised Bud. “I don’t know a thing about it, honest Injun. You asked—”

“Yes, I did,” said Elaine angrily. Her hand went to the gear-shift, and her little arched foot to the starter. “Well, I’m going down there and see just—”

“Hold ’er,” said Bud, sitting up straight. “You can’t go down there. There may be some more that have sneaked over before Sam and Bill got there.”

“What? I can’t! Who are you to tell me what I can do? Are you afraid, Mr. Yancey, and you a ranger?”

“I told you not to,” said Bud. As he spoke, his left foot came against the gear-shift, and he reached over and shut off the ignition.

“You dare!” flared Elaine, who had the full complement of temper that is supposed to go with red hair, and hers was brick red, not bronze nor auburn. “Take your foot away—get out of this car!”

“I wont,” returned Bud, “not any. That’s darn’ dangerous ground down there at the minute, and you’re not going down there, a-tall.”

“I’m not—a-tall,” mocked Elaine, her lips tight. “Well, I am—just as far as I want to go, Mr. Texas Ranger Yancey. Why, you’re afraid to go! You are just as white as—as anything.”

“That’s right,” drawled Bud silkily. “I’m afraid.”

“Get out, then, and wait until I come back,” said Elaine.

“I don’t reckon I can do that,” answered Bud, “because you’re not going in the first place.”

“Well, I am,” asserted Elaine. “Take your foot away, please.”

“Wait a minute,” said Bud. “You don’t sabe, I reckon. If any of those raiders got across before, they’re holed up somewhere. If we ran on to them, I might not be able to stand them off. Then you’d—”

“If we do,” Elaine interrupted, “you can get out and run as soon as you see them—you can see so far.”

Bud Yancey’s face really did go white at this taunt. None of the Yanceys were noted for much of an even temper, and Bud ran very true to type. But his voice never raised above the slow, soft drawl.

“Yes’sum, I could do that—if we got down there. But we aren’t going. You better start back to the Fort, I reckon.”

“Well,” said Elaine bitterly, after one good look at the frosty black eyes of Mr. Yancey, “I’m not big enough to lick you, much as I’d like to; so you can take your foot away. I’ll take you back to the Fort where you’ll be safe, Mr. Yancey; and before I start, I’ll tell you one thing—that is I think you are nothing but a scared cat, and I don’t ever want to see you again.”

“I’m right sorry you feel that-a-way,” courteously answered Bud as he took his foot from the gear-shift. There wasn’t another word said by either of them on the drive to the Fort. When they arrived, and Elaine had stopped in front of her brother’s, Bud got out of the car, took off his wide soft hat, bowed and said, “Thank you very much for a right pleasant ride,” and walked over towards Captain Carter’s quarters.

Elaine sat there at the wheel for a moment with a look on her face that plainly showed she was still angry but not quite as happy as a young lady should have been who had told a young man she hated just what he was.

“Where’s the gent that’s been hanging on to your apron-strings, Lainy?” asked Webb at the breakfast-table sometime later. “He hasn’t hove in sight for a week or more.”

“I don’t know—and I don’t care,” answered Miss Webb shortly.

“What!” he shouted. “Don’t tell me he’s done quit you!”

Elaine looked at her only brother dispassionately. “Do you know,” she stated in a conversational tone, “I always wondered how you managed to slip through at the Point. And now, as I see what you look like when you laugh that way, I wonder more.”

“What do I look like, Lainy?” grinned Webb. “I thought sure as shootin’ that you and Bud—”

“You look like an absolute idiot; and you are not far from being one, at any time.”

“My heavens,” teased Webb, “it must have been a fierce battle! Do you mean to tell me you allowed a Yancey to ruffle the feathers of a Webb this way? Make up, old kid, and do it darn’ quick. I need your help with Betty.”

“Well, you wont get it,” declared Elaine firmly, “and I wont make up with him.”

“Even if you do get a chance,” jeered her brother. “He hasn’t come around lately, has he? Couldn’t you hold—” Webb stopped and looked keenly at her. “What’s the matter, sis?” he asked in an entirely different tone of voice. “Tell old John about—if you can.”

“Certainly I can. It—that day we drove over to see a man Bud wanted to ask something. When we were coming back, I stopped to look at the view, and there was a fight down in the—chaparral, and after it was over I wanted to go down and see it, and he wouldn’t. He put his foot over against the gear-shift, and—”

“Wait a minute,” interrupted Webb. “What went before this foot-putting stuff? You say there was a fight down in the chaparral? You mean a fight in the car, don’t you?”

“No, I don’t—not that kind of a fight, anyway, though there would have been if I’d been big enough. He held it with his foot, and I couldn’t move it.”

“That’s what I am trying to get at. Why did he?”

“Why, he said it was dangerous to go down there, because there might be some more of the raiders, he called them.”

“And you were going, anyway?”

“Yes, I was—or no, I wasn’t really; but after he said I couldn’t, then I—”

“Oh, I see. He said you couldn’t, so you were going anyway. Then he put his foot against the gear-shift and stopped you. Did it ever occur to you that a Texas ranger, in his own country, might know whether a thing was dangerous or not?”

“No, it didn’t; and even if it did, he had no right to stop me.”

“Well, my persecuted race!” said John Webb, in honest amazement. “And you sit there looking at least half-witted. Why, you darn’ little fool, it was his business to stop you! Do you think he would let you go, knowing you’d go into danger?”

“I wasn’t going into danger,” said Elaine furiously, “and if I were, he ought to protect me. He was afraid, and—”

“What? Afraid? Bud Yancey? Now I know you’re goofy. What the heck and high water is the matter with you, Lainy? My gosh, if being in love makes people act that way, I’m darn’ glad I’m—”

“Oh,” said Elaine, getting up from the table, “you make me so—so damn’ mad!”

“Well,” grinned Webb, rising also, “so does Mr. Yancey. . . . H’m—I wonder who the heck that is? Boy, howdy, see him make that turn? Take it easy, boy; Liz wont stand much of that. Holy cats! He’s coming over here!” And Webb ran down the steps to meet the flivver that was charging up to the steps.

A young Mexican jumped out almost before it stopped, and began talking to Webb. Elaine promptly ran down the steps and tried to get what he was talking about. Her Spanish ran about twenty or thirty words, and the very much excited young Mexican was going up around three hundred a minute. Elaine got: “Los Rangeros—mucho malo batalla—” and then was entirely lost trying to follow. Finally, she got: “El Rangero Earp y el Rangero Yancey, muy malos hombres—”

“Jack,” she said, seizing Webb’s arm, “what is it? Tell me!”

“What? Where the—go away, woman.”

“I wont. You tell me.”

“All right, if you want to know, I’ll tell you. Garcia’s gang came across the line to get some rangers that mopped up on some of them a little while ago. This bird says they found the rangers, and there is one bearcat fight going on down near the old Three C ranch. He’s a friendly Mex and has come in to get help. He says that some Earp and Yancey are holding the fort, but they wont last long. He also says that they are very bad men in a battle. Now, you know, go on away. I’m going to phone to Bill Carter to get his doughboys over there pronto.”

“What Yancey?” asked Elaine directly of the Mexican.

“El Senor Budero Yancey y—” He stopped as Elaine whirled around and ran to the house.

“Can cars make it up to this Three C ranch?” Webb asked.

“But no, senor,” answered the Mexican, getting a strangle-hold on what English he had. “These bridge at the valle es debajo del agua—mucho agua.”

“Holy cats—under water! How close can they get?”

“Dos milas. These Garcia—he ’ave muchisimo hombres weeth—”

“Yeah? I’ll get very much men on his tail too, darn’ quick.”

Webb put down the telephone receiver after having been profanely ordered away from it by Captain William Carter, commanding fifty-odd hardboiled infantrymen who were literally spoiling for want of a fight—Carter’s last words being: “Get away from that phone and give me a chance. Don’t you call up anyone else, either, or I’ll bust you wide open.”

“Oh, my sainted aunt!” Webb said as he started away from the telephone. “Every darn’ bus out jazzing around, and me with a busted arm! By gosh, I’ll go with those— Where do you think you’re going?”—to Elaine, who had returned, dressed in flying overalls.

“That Martin bomber is on the line, and I’m—”

“What? That old crate? She’s out of commission—and even if she weren’t, you couldn’t fly her.”

“Major Carnduff said I could fly any bus on this station,” protested Elaine, “and I’m going to. I can fly as well as you can, and—”

“Better,” agreed Webb, “much better. Only you’re not going to, because there is no bus to fly, ding it all. If there were, I’d fly it myself. The oil-line is out of that baby, and—There goes Bill Carter and his gang! Holy smackers, Bill’s copped the old man’s pet car and loaded it to the guard-rails. I’m going with the next load, no foolin’. You stay here, Lainy.”

“My car is much faster than any of theirs,” insinuated that young lady.

“Yeah? That’s right. I’ll take it. Go get it for me, Lainy, like a nice girl. Manuel, you wait here. Go and get something to eat. Mucho dinero coming to you, old kid.”

Elaine brought her car around in front. “You can’t drive and shift gears with one hand,” she pointed out, making no effort to get away from the driver’s seat. “I’ll drive you as far as the bridge.”

Her brother, knowing her full well, looked at her with deep suspicion. “You will? And then what will you do? Holy cats! There go two more cars! I’ve missed the first bunch— All right, you drive me to the bridge. Catch up with Bill Carter if you can. Then you turn around and come back, you hear me?”

“Yes, dear,” Elaine answered meekly, so meekly that Webb looked at her grimly and said: “I mean it, sis.”

Without any further discussion Elaine devoted her attention to the wheel; the roadster not only caught up to Captain Carter’s load of doughboys but passed them, long before the bridge was in sight, and raced on ahead.

The bridge was three or four feet under water. Generally the little stream that came slipping down from the hills was quiet and peaceful, but a cloudburst had made it a roaring torrent. There was a foot-bridge about a mile up, connecting the walls of a narrow deep canon from which the stream issued to the valley below. It wasn’t much of a bridge, being used by men going up in the hills who did not want to circle the valley. The water had not nearly reached it, and as Elaine stopped at the edge of the flood-water, she pointed it out.

“Go right ahead, Mr. Webb. There’s your bridge up there on the right.”

“Fools rush in where angels fear to tread,” chuckled Webb. “I’ll wait for Bill and his cohorts.”

He didn’t have long to wait, for they arrived about two minutes later. Carter smiled cheerfully at Elaine.

“Hullo, Lainy! Going in as Red Cross?”

“No, I am not,” answered Elaine hotly. “I’m going home. This darn’ old brother of mine wont let me.”

“That’s where he shows sense for once. Come on, you terries—show me something! Sergeant Bate, detail four men to stay with the cars. Let’s go!” The other cars had arrived and unloaded.

“Well,” said Elaine bitterly, to anyone who cared to listen, as she watched Captain Carter, her brother and some fifty infantrymen start for the bridge in what looked more like a free-for-all race than an orderly advance, “I’ll never forgive that John Webb or that Bill Carter, either!”

She started her car, turned, waved good-bye to the four disgruntled doughboys left behind, and headed for the Fort.

But instead of keeping on the trail, after she had gone about five miles, she turned sharply to the left. As she did, she said to the wheel: “I’ll bet anything I can get right around in back of the Three C. That’s the old ranch I saw the other day, and—” The trail she had turned on began to narrow and twist, and Elaine wisely decided to put her attention on her driving. About half an hour later, she said aloud: “That darn’ road I came down ought to be around here somewhere. I know I passed that big rock right after— There it is!”

The trail leading off to the left could hardly be called a trail, let alone a “road,” as Elaine named it. It was hardly wide enough for a car, even where it tied in with the one she was on. Now there was a lot of fallen timber and rocks in it. “My heavens,” she said, standing up and looking it over, “I’ll bet that cloudburst has ruined it. I can’t drive over that! I guess I’ll have to go back. Well, I wont, and that’s that. This road leads up in the hills right back of the Three C, and I’m going to find out if—” The last was said as she was getting out, and the wheel,—not deigning to get into an argument with a red-headed young lady,—keeping quiet, Elaine started up the trail on foot. It was much farther than she thought, and after a steady climb for more than an hour, without sighting the hill she was sure topped the old ranch buildings, she decided to sit down and rest.

Just then the sound of shots came down the trail to her; then a moment later, the patter of running feet. The trail, a little above where she was sitting, took a curve around a big boulder, and then another around an outstanding ledge.

Without a second’s hesitation Elaine rolled off the rock she was sitting on and burrowed into the tangled windfall behind it. In doing it, she proved that she was, as Ma Earp had said, “a right smart girl” and worthy of the border, where the old rule still holds good in spots: “If it’s strange, it’s hostile.”

When she stopped, she was under cover, and by pulling a couple of the branches over a little, could still see up the trail. As she did, there were three more shots, and she heard someone wail, “Madre de Dios! Soy muerto!” Then, rounding the curve and running as fast as they could, falling over rocks and windfalls, scrambling up, came four of Garcia’s band, who had tried to ambush some Texas rangers. Their gay serapes were torn and muddy, their heads bare, their mouths open and their faces expressing their one thought, which was to get as far away as possible from whatever was behind them. They came by Elaine’s hole-up so fast they did not even look in her direction.

“My goodness gracious,” she gasped, “they must be—the boys must have ar— Oh! It’s—it’s Bud!” and she pushed her way out.

Coming down the trail, slowly but with grim determination, on foot, with rough homemade bandages on him in several places, a rakish reddened one around his head, almost covering one eye, was Mr. Buford Yancey, Texas ranger. In addition to the above-described decorations, he had firmly held in his right hand an old ivory-handled .45; and around his waist, hanging on one side almost to his knee, was a belt in which most of the cartridge loops were empty. His face and lips looked gray, but his eyes were holding the same look that they did when he stepped into the street that day at Wirton; and on his gray lips was the same little frozen smile. Back of him, about ten feet, came another young man, with about the same number of bandages, the same kind of a gun in his hand—and quite the same kind of a look and smile.

When Elaine rose to her feet from the windfall, Bud stopped and regarded her gravely, a puzzled look taking the place of the cold, bleak one in his eyes. He stood there swaying a little; then he shook his head and closed his eyes for a moment, as if to get rid of a vision. Sam Earp had come up when he opened them. As he did, Bud looked at Elaine and announced gravely: “We’re goin’ to chase those jaspers plumb through to the Guatemala border. You go on home, if you’re real.” And he started down the trail.

“Bud Yancey,” said Elaine, taking the one hop necessary to get in front of him, “you are not! You are not going another step. Why, you are wounded and everything! Bud—you can’t go and leave me here! I’m afraid! Don’t leave me, Bud.”

Sam Earp had stood there, doing more than a little swaying on his own account. “That’s right,” he said solemnly. “It’s your girl, Bud. Can’t leave any woman who’s scared—you stay and I’ll go and get us those hombres.” Mr. Earp, having settled the matter, started out; but on making the first step, he slid to the ground and lay there.

“Doggone!” said Bud, looking down on him. “Sam’s out—and Bill is out—and Capt’n Coudray is full of lead. Reckon it’s up to me to do the protectin’. Come on.”

“Oh, thank God!” Elaine had been standing so that she could see up the trail. As she spoke, Bud tried to turn around. He made it halfway; then as his eye caught the flash of steel and the brown of khaki uniforms, he joined Mr. Sam Earp on the ground at Elaine’s feet.

Lieutenant Webb, a sergeant and twelve or fourteen men, arrived a moment later.

After one look at the rangers, he snapped out several orders that resulted in improvised slings attached to gun-barrels. All the way down the trail until Elaine’s car came in sight, he did not speak to her. Garcia’s men had turned off the trail, heading south before they reached the car, and it was as she had left it. Finally Elaine eased over beside him.

“Jack, do you think that he—that they are badly wounded?”

“I don’t think so. If they had been, they couldn’t have chased those birds up and down hills.” He had fully intended sending Miss Elaine Norcross Webb home to New York with only a few chosen words, but the sight of her woebegone little face and the real tears in her eyes made him change his mind. “We got there just as Garcia was making a final charge with all his outfit. These lads were holed up in the house with two or three more. Boy, howdy, it was lovely billiards! They were so intent on scragging the rangers that we snuck up on ’em. There was enough of them left to make it even. Hot damn, Lainy, old kid, we run ’em ragged! You ought to have seen the ground in front of the house and on the sides where they’d tried before. It was covered with—”

“How did Bud and Sam Earp get—” interrupted Elaine.

“Why, some of them scattered out toward the hill in the rear, and all of a sudden the side door came busting open, and out came those two young hell-cats.” (Lieutenant Webb was all of twenty-four.) “And up the hill they took after them. I jarred loose, thinking you might want to see your dear Bud in the flesh once more, and rounded up these men and came after—Say, that reminds me: just how come you here, madam?”

“Three of them came running by,” Elaine said, ignoring the question, “and then Bud and—”

“Three of them? Holy mackinaw! I wonder if those two got all the rest. This Bud Yancey of yours didn’t act much as if—”

A soldier came back and saluted. “If the Lieutenant pleases, the ranger ahead has come to and is asking for Miss Webb.”

“Go ahead, Lainy,” Webb started to say, but Elaine was already on her way.

She slipped in between the bearers and took firm hold of Bud’s hand.

“Bud, are you all right? Tell me.”

“I am now,” answered Bud, with a grin that was rather a weak one, but a grin just the same. “Darlin’, I knew it was you up yonder, and all the time I didn’t, some way. Honey, you’re a right nice girl, and I love you like—”

“Bud Yancey, you are not to talk. You just lie still. Bud—I’m sorry I said that—”

“Darlin’, you better tell me right quick if you’re going to love me, while I’m not dizzy and—”

“If you don’t keep still,” threatened Elaine, “I wont tell you, ever, that I love you. And—and—I do, Bud.”