Title: Stopping the leak

Author: Madeline Leslie

Release date: October 19, 2025 [eBook #77089]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Graves and Young, 1865

Transcriber's notes: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

BROOKSIDE SERIES.

BY

AUNT HATTIE.

[Madeline Leslie]

BOSTON

PUBLISHED BY GRAVES AND YOUNG

No. 24 Cornhill.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1865, by

GRAVES AND YOUNG,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

DEDICATION

——————

TO

HARRY AND GEORGE COLVIN,

SONS OF MY ESTEEMED FRIENDS IN BALTIMORE,

I dedicate this Volume,

TRUSTING IT MAY HELP THEM TO AVOID THE FOIBLES AND

EXCESSES WHICH DESTROY FORTUNE AND CHARACTER,

AND TO CULTIVATE INDUSTRY, ECONOMY, AND

THOSE KINDRED VIRTUES

WHICH DISTINGUISH THE WISE AND GOOD.

THE AUTHOR.

CONTENTS.

LADY-BIRD

THE RECONNOISANCE

DAYS OF YORE

WHO IS MISTRESS?

FARM VERSUS RUM

A RAY OF SUNSHINE

POLICE AND CRIMINALS

DETECTION AND ARREST

A PLUG IN THE LEAK

A STEP IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION

ONE LEAK STOPPED

A SECOND LEAK STOPPED

FAILURE FROM LEAKS

HOME VERSUS OYSTER SALOON

AFFIDAVIT

THE RESTORED HOME

DANGER AND COURAGE

LEAKS ALL STOPPED

STOPPING THE LEAK.

LADY-BIRD.

"THERE'S a leak somewhere!" was the emphatic exclamation of Mrs. Mercy Lovell. "I, of course, have my own opinion where it is, but that's neither here nor there. 'Tisn't my way to state my opinions in a hurry."

Mrs. Lovell had reached the house of her nephew the evening previous to that day on which I have so unceremoniously introduced her to my reader, and having been invited to a tour of reconnoisance through the spacious mansion, had, on her return to the dining-hall, given expression to the prudent remark,—

"There's a leak somewhere!"

Mrs. Everett, wife to her nephew, stood daintily holding up her nicely-embroidered morning wrapper, gazing in the old lady's face with an air of solicitude and wonder.

"What do you know of the servants, child?" inquired Aunt Mercy, condescending to smile as she saw with what reverence her opinion had been received. "Very little, except that the cook makes splendid coffee and muffins. She has only been here three days, and breakfast is the only meal we have taken at home."

"Goodness sakes! Why, I should be crazy with so much going abroad. Once a month is as much as I ever go out to take a social cup of tea with a neighbor, but that don't stop the leak. Who's that finikin-looking creature that handed round the coffee this morning? Is she honest and faithful to her business?"

"I suppose so. She waits on the table beautifully. She's been here ever since we commenced keeping house, and she was the one who recommended the new cook. Mamma says we must try and keep her, she does up my dresses so nicely."

"Well, what kind of a cook did you have before?"

The young bride laughed merrily.

"Oh, such a funny-looking woman,—nearly as broad as she was long. Lawrence insists she fatted on our butter; for loads of it were brought into the house; and yet she was always coming to me with the complaint, 'There's no butter, ma'am.' I declare," with a heavy sigh, "I had no idea being married brought so much care."

"What did you say to her? Did you insist on knowing what she had done with it?"

"I insist!" There was a merry peal of laughter like the tinkling of silver bells. "Oh, Aunt Mercy, you're not in earnest! I told her to send Tom to the grocer's for more, and not trouble me."

"And who is Tom?"

"Now I can tell you. He's a boy, or man I suppose he'd call himself, since he sports mustachios, whom papa found at some out-of-the-way place. He had been taken up for stealing bread, because he was so very hungry, you know; and papa pitied him, and paid the fine, and took him home, where he's been ever since till I was married; and then mamma gave him up to me. I must have somebody to do errands, you know; and mamma could spare him because the coachman is good-natured and is willing to do such things."

"Have you any more servants?"

"No; Lawrence laughed at the idea of three being necessary to wait upon two of us, but mamma thought I ought to have a woman for myself."

"A woman! What for, pray?"

"Why, a dressing-woman, of course. A French woman is best,—one who can dress hair, and is skilful about the toilet."

"If you can't dress your own hair, you are not as smart as I am. I never had anybody touch a comb to my head since I can remember," said Aunt Mercy, decidedly.

Lily glanced at the stiff pug on the back of the old lady's head, and again the peal of music echoed through the rooms. Laughter is always contagious; and Mrs. Lovell's risibles were not proof against the appeal, even though she shrewdly suspected herself to be the object of it.

"Well," she said, pursing her mouth, "I think we shall come at the bottom of the leak by and by. I may as well go to my chamber and get my knitting,—I suppose you have some work,—and we can talk the subject over."

Lily colored a very little as she answered,—

"I scarcely know how to sew. I mean to learn by and by. Lawrence was so surprised when he asked me to sew a button on his shirt that I rang for Ann to do it. He said he thought girls learned to sew as soon as they could walk."

The old lady stopped short and gazed at her niece over the top of her glasses as if she were a new and curious specimen of the animal kingdom that ought to be critically examined.

"For mercy's sake, child, do tell what you can do with yourself from morning till night!"

Lily threw herself into a chair laughing till the tears stood in her eyes.

"Why, you see," she answered, when she could speak, "I only left school two months before I was married; and then my time was all taken up with French and Italian and music. I finished the regular course a year before, but mamma wanted me to be very learned,—" another laugh,—"and then I had Monsieur Follywasher three times a week for my dancing-lesson."

"Goodness! If I'd been your ma, I wouldn't have trusted you with a man who had such a heathenish name for nothing. Pray, what did you want of a dancing-master? You float round anyhow just like one of the fairies I've read of."

"Monsieur Follywasher would say I owed it to him if I move gracefully. He's a Frenchman, though his grandfather was a German, as his name denotes. He's the sweetest, dearest man, with such cunning little whiskers, perfumed up so nicely. All the girls were in love with him."

"Were you?" The gaze was almost stern this time.

"I! Oh, no, indeed! Why, Lawrence had been waiting on me a year; besides, I don't mean exactly in love, only they admired him excessively. He's so handsome and graceful!"

"I don't see how you ever fell in love with Lawrence. I always thought he was the plainest-featured of any of my nephews; and none of 'em would be taken for Apollo."

"Oh, Aunt Mercy, you're too funny! Why, I think Lawrence is splendid. He's got such great black eyes, and such a heavy, curling beard,—I'm very proud of his beard,—and then when he smiles, he shows his elegant teeth. The girls used to wonder I was not afraid of him,—and he is sober, but he always smiles for me. I had ever so many beaus," she rattled on. "Papa is rich, you know, and I'm his only child; and then I'm not particularly ugly, I suppose," she added, with a pretty tinge of rose coloring her lily cheek, "but I never liked anybody till I saw Lawrence."

The old lady gazed at the pretty creature for a moment in silence, and then, recalling the subject with which they began, remarked, gravely,—

"I suppose you carry the keys."

"What keys, Aunt Mercy?"

"Why, the keys to the store-closet where the sugar and raisins and eggs are kept, and the keys to your bureau where you put your laces and rings, and all such finery."

Lily's eyes were opened wider than ever. She arched her delicate eyebrows as she inquired, eagerly,—

"What should I want of keys to the store-room? I don't even know whether there are locks on the doors. If there are, I suppose cook and Tom attend to them. Ann, of course, puts away my jewels; and she is responsible for their safekeeping."

"Well, well," was the horrified exclamation, "I'm beat now! Why, the biggest fortune in Europe—and they say the Rothschilds' is the biggest—couldn't hold out no time against such goings-on!"

Here the old lady, fearing she should say something she ought not, hurried to her room for her knitting. In a few minutes there was a loud peal at the bell, and, peering through the closed blinds, Mrs. Lovell saw an elegant carriage, two prancing black mares, and a liveried driver at the door. An elegantly dressed lady sat within the carriage, giving directions to the footman, whom she had sent to the door.

"Mrs. Everett is at home," the old lady heard him say as he let down the steps for her to alight.

"Mamma, come up to my room, please," called Lily, over the balusters.

"So that's Mrs. Percival," said the old lady, with a sigh. "Why, she's dressed out like a duchess! And what a carriage! Two servants, too, as respectable-looking men as there are in our town. I should think they'd be ashamed of themselves, spending their lives so. Just look now at that great popinjay getting up behind. Well, well! It does beat all. Little I thought, when I used to give Lawrence a piece of short-cake for bringing in wood, that he'd cut such a dash as this."

Her reverie was cut short by a quick knock at her door. And Lily, with a tiny hat shading her beaming face, hastened in to say,—

"What will you do with yourself, Aunt Mercy? Mamma has called to take me out for a drive, but I'll be sure to come home before Lawrence leaves the store. He pretends, foolish fellow, that he likes to have me open the door for him."

Oh, how the light sparkled from her eyes as she said this! Then she added, thoughtful of her duties to her guest,—

"Will you ring the bell and order lunch whenever you wish it? I shall stop with mamma to see a friend."

"La! Don't you worry about me," returned Aunt Mercy, much pleased to be even thought of under the circumstances. "I'll find enough to do; I shall hunt up Lawrence's stockings, and darn the holes. I'll take care of myself, never fear."

Lily bent down and pressed her rosy lips to the old lady's cheek. It was a trifling, every-day act, but somehow it made Aunt Mercy's eyes grow dim.

"She's a sweet, beguiling creature," she repeated to herself, rising and walking to the window to see the last of them, "but she's no more fit than a new-born babe to be trusted with a house."

Lily ran lightly down the steps, nodding pleasantly both to the coachman and footman, who were old family servants, and then followed her mamma into the carriage. Mrs. Lovell lost not one motion until the carriage rolled away from the door, and then she sat down to her knitting to compose her thoughts.

"Well, well," she said to herself, "no wonder Adam ate the apple, if Eve gave it to him with a smile like Lily's! She's pretty as a picter, but that don't make her fit to keep house."

THE RECONNOISANCE.

AUNT MERCY'S thoughts kept her busy for an hour, her stocking, meanwhile, growing visibly. Then she started up for a visit to the kitchen.

"I wonder who ordered dinner," she said to herself, as she went down the broad staircase.

The table was spread in the kitchen with cold ham, spring chicken, an egg omelet, and hot coffee. And around it sat cook, Ann, Tom, and a hugely-whiskered stranger, partaking of the highly-seasoned viands with great relish.

To say that Mrs. Lovell was surprised would but feebly express her feelings, as, with one quick glance, she took in the whole scene. But she was far too shrewd to allow this to be perceived, and merely saying to the cook, "Mrs. Everett will dine at home to-day," passed on through the kitchen to a large pantry beyond.

She had already visited this apartment once, in company with her niece, but now everything wore a different aspect. Cook joined her instantly, her cheeks glowing like fire.

"It's not what I'm used to," she began, in a loud tone, "to have company intrude on my apartments. If ye want lunch, I'll send Tom with it to yer order. Mrs. Everett is the mistress here; and I'll not have two to dale with!"

Aunt Mercy had already spied an elegant damask napkin protruding from a drawer under the dressers, and deigning no answer to this harangue, except a momentary stare over her glasses, deliberately proceeded to make a more thorough search of the premises than she had thought it prudent to do in the presence of her niece. Pulling open, therefore, the broad, deep drawer, she found the napkin used to enfold half a dozen of the delicate muffins admired so much at the breakfast-table; underneath it were two long, damask table-covers of the finest quality, soiled and stained with fruit, four damask towels, one fine linen pillow-case, the delicate lace ruffle torn from contact with a nail in the drawer, and lastly a loaf of frosted cake.

Without one word of comment, and proceeding as calmly as if the inspection were an every-day affair, Mrs. Lovell throw one after another of the soiled articles across her arm, as totally unmindful of the abuse and coarse invectives Bridget was heaping on her head as she would have been of the buzzing of a fly.

By this time Ann and her associates had pushed back their chairs from their disturbed luncheon, and were waiting to see what would follow. The muffins were placed on a plate in the dresser, and a net cover put over them, the frosted cake carefully deposited in a tin box standing empty on a chair, and then the old lady said, calmly,—

"Ann, wont you get me a small tub? I'll show you how to take the stains from these table-covers while cook prepares my luncheon."

Turning to the latter, who stood, her arms akimbo, casting defiant glances first at her and then at her companions, she said,—

"Make me a cup of tea,—oolong, if you have it; one spoonful will do, and send it up on a tray with a slice of ham and the muffins you'll find in the cupboard."

"Sure as yer alive, the old critter's deaf!" murmured the stranger, in a low voice, to Ann.

"Look here!" said Mrs. Lovell, carefully gathering all the stains into her hand and laying them in the tub. "Pour boiling water on the spots, and repeat as often as it cools. Then dry them, and they'll be ready for the wash."

Casting her eyes to the table, she saw that one of the best covers had been used, and she said, coolly,—

"You'd better do that cloth at the same time. I see it has strawberry stains on it."

She waited until Ann brought the large kettle from the range and poured on the water, and then, with another glance around the room, walked up-stairs, taking the box of fruit-cake with her.

"Well, well!" she thought. "Sure enough, I've begun to find the leak. 'Twould take more than the Rothschilds' money to support such extravagance. 'Twill be the ruin of Lawrence before he's a year older. Goodness sakes! How that woman did rave! Frosted cake, coffee, and jellies! I'm beat now!"

She sat waiting in the dining-room for her lunch to be served, and might have waited a month, but for a step in the hall, and a voice, calling,—

"Lily, my Lady-bird, where are you?"

"Lily's gone out to ride," explained Aunt Mercy, hurrying to the door. "She'll be terribly disappointed though; she calculated on being at home before you came."

It was evident the husband was keenly disappointed, but he made an effort to conceal it.

"I hurried through my business," he said, "to come home and lunch with you both. Have you ordered anything?"

"Yes,—a cup of tea and some cold ham. There is coffee and muffins below, and chickens, if they are not all eaten up."

He rang the bell with a quick jerk.

"Bring up lunch for two," he said, as Tom made his appearance,—"the best you have."

Ann came at once to lay the table.

"You may set the teapot by my plate," said Mrs. Lovell. "I'll pour out and wait on my nephew, so you can go on with your work."

She spoke pleasantly, but Ann looked sullen, and made no reply. The old lady had determined to improve the opportunity to enlighten her nephew in regard to the want of proper management in the kitchen department. As soon as they were alone, he opened the conversation at once.

"Well, Aunt Mercy, how do you like my Lady-bird?"

"I think she's the sweetest, dearest, most beguiling creature I ever did see!" responded Mrs. Lovell, warmly. "Why, only think! She came to bid me good-by when there was the beautifullest carriage waiting for her,—and she actually kissed me too!"

"That was because you'd been praising me, I suppose," he answered, laughing.

"No, I told her you were thought to favor me; that you were the homeliest of all my nephews, but she wouldn't agree to that. It's no kind o' use to repeat what she did say, 'cause she makes no secret of it I take it. I've been a-wondering whether Eve was any like her; 'cause if she was—"

"You think I'd eat the apple," he said, interrupting her. "Well, I see she's made a convert of you, and I'm glad to see my two best friends understand each other. I never shall forget what you've been to me, Aunt Mercy. I've told the story to Lily, and she's all ready to love you as well as I do."

The old lady coughed and choked. Not all Bridget's invectives had moved her as those simple words did. But the meal was almost finished, and she had not yet hinted at the subject she wished.

"I wonder what Mrs. Percival could be thinking of, to let her daughter be married till she'd learned how to manage a family. Why, Lily, pretty as she is, knows no more about what's going on in the house than a china doll."

"I suppose I must take the blame of that," returned Mr. Everett, while a little cloud rested on his brow. "I thought she'd learn better when she saw the necessity for it, and so she will with a few hints from you. She's as light-hearted as a bird, and I would not have her otherwise for all the money in this rich city. But, as I wrote you, housekeeping is a ruinous business to a young man."

"There's a dreadful leak somewhere!" she remarked, gravely. "And it must be stopped."

"Yes," he continued, "I'm convinced that it costs us more than it need to, even to live in style, but how to manage is the question. My Lady-bird knows absolutely nothing about economy, and how she is to learn it without troubling her pretty self is a problem I should like to see solved."

"It's plain there must be a head to such an establishment as this, Lawrence."

She then proceeded to give him, in brief, the result of her morning reconnoisance.

He bit his lip with anger, rose and paced the room, saying,—

"I shall be ruined if we go on at this rate. Say, Aunt Mercy, what can be done?"

"I've thought it all over," she said, "while I was waiting here by myself. 'Tisn't very convenient, but if it's duty, it must be done. I've set out to find the leak, and when I do, I think I can contrive to stop it. I'll write home to Caroline to shut up the house and go back to her mother's, and I'll remain and right things up, but first I must have authority from you and Lily, so that the servants will obey me."

He answered by ringing the bell.

"Tom," he said, when the youth appeared, "my aunt, Mrs. Lovell, will give you directions for the future. You will go to market under her instruction, and you may repeat what I say to Bridget and Ann."

The old lady had her eye on Tom when the order was given. She was convinced that her first opinion of him was correct.

Mr. Everett sat a few moments talking with his aunt, then wandered restlessly to the parlor, to see whether Lily was net in sight. Though absent from her but a few hours, he longed for a glimpse of her bright face. He ran up to her chamber, and presently called at the stairs,—

"Aunt Mercy, come up here!"

It was the old lady's first peep into that sanctuary, and, for a moment, she stood at the entrance, her keen eye glancing quickly from one object to another.

The house was built by an old nabob on his return from a long sojourn in the Indies, and this room was especially fitted up for his young bride. On one side of the apartment the floor was raised about a foot and covered with marble of different colors set in mosaic. Upon this platform stood the bedstead covered with elaborately-wrought lace depending from a gilded scroll fastened to the ceiling. Curtains of lace and delicately-tinted rose damask partially concealed the windows. Chairs and lounges stood inviting the weary to repose; a costly mirror, reaching nearly to the ceiling and resting on gilded brackets, was flanked on each side by gilded statues holding lights for gas, while the toilet-table and its belongings were wonders of art. The young husband stood in the doorway leading to the dressing-room, a complacent smile hovering over his features as he witnessed Aunt Mercy's gaze of astonishment, and then said,—

"Come in here; it was to show you this I called you."

"It is very, very beautiful. It is like a fairy tale," she murmured, slowly advancing, "but—"

"I know what you would say," he exclaimed, interrupting her, "and it is a question I sometimes ask myself: Can I, ought I, to start in life so luxuriously? Lily has been used to all this from her birth, and scarcely notices it. I do not believe she depends on costly surroundings for happiness, but I love to see her in the midst of beauty, and I think I can afford it. One thing is certain: I have not run in debt. Your teachings have proved too powerful for that. Now rest in that chair, and let me show you something."

He lifted a book bound in velvet from the table and raised the clasps with reverence. There was a worked book-mark carefully laid in at the twelfth chapter of Exodus, and to this he turned.

"This was my bridal gift to my Lady-bird," he said, speaking her name tenderly,—"the one she says she prizes most. Dear little girl! Among all her gay accomplishments, she had never been taught the Bible's blessed truths. I told her how I loved this book, and what I hoped it had done for me; that the warnings I found here had saved me from becoming what most of all she loathes,—a profligate; that its invitations had led me to One better than any earthly friend, because his love bestows all blessing. 'If you will learn to love the Bible,' I said, 'our affection, begun in this world, will go on ripening through all eternity.'

"She looked full of wonder as she exclaimed, 'I always thought the Bible would make one gloomy.'

"'But you don't call me gloomy,' I said, smiling.

"'Oh, no, indeed! I will read it and love it, if it will make me like you.'

"Since that, she has never left her room in the morning till she has read a chapter. See, this was what she read this morning. All the time I was dressing, she was talking to me about it. I can't help thinking that the Spirit of God is moving on her heart; and oh, what a Christian she would make! So full of enthusiasm and soul! Do you wonder now, Aunt Mercy, that I thought it not too soon to remove her from the atmosphere of worldliness which surrounded her at home, and have her here, where I could turn her thoughts to high and noble views of life?"

The old lady's dim eyes answered him sufficiently.

"I am glad you told me this," she murmured, her voice trembling. "I thought she was different from other gay girls. Have you ever taught her to pray, Lawrence?"

He colored a little as he said, hurriedly,—

"I never thought to tell these things; they seem too sacred. But you have been a mother to me, and—yes, I will tell you.

"The morning after we were married, I took my pocket-Bible and read as usual. I noticed that she looked sober, but I didn't know what foolish fears were filling her little heart. Then I knelt in the closet, beckoning her to come, if she wished, and kneel by me. She did not, but stood leaning against the door. I offered my petition silently, as I had been accustomed to do, and when I arose, my poor, frightened Lady-bird threw herself into my arms.

"'Are you going to die, Lawrence, that you pray?' she asked, quickly.

"I noticed that her eyes were moist and her lips tremulous, but I didn't understand her fears.

"'No, darling,' I said, seating her for the first time on my knee. 'I was thanking our good Father for my beautiful, loving wife; and then I asked him to teach me to care for your best comfort, so that you might never regret you had left your father and mother, and come to live with me.'

"I wish you could have seen her face brighten. She put her cheek close to mine, and said, softly,—

"'I would like to thank him too, but, Lawrence,' she added, in a moment, 'I thought,—I always heard, people prayed to God when they knew they must die, so that they could go to heaven, you know. I thought God was angry with us, and wanted us to be sober all the time, and not at all loving and nice.'

"I was really frightened to see how ignorant she was, even of the simplest Bible truths, and thought our morning could not be better spent than in telling her what glorious news was contained in its pages.

"I began with the Garden of Eden, sketching briefly the stories of the creation and fall, so familiarly known to every Sabbath-scholar.

"She was greatly excited and sometimes laughed heartily. Eve she condemned totally, but for Adam's sin she found some excuse, exclaiming, with a tear in her eye,—

"'He loved her so well, you know, Lawrence.'

"From this point, I went rapidly on to the birth of the Saviour, when she frequently interrupted me by asking,—

"'Is it true, Lawrence,—is this all true? Oh, why did nobody ever tell me of it before? And you say he's been loving me all this time?'

"Her head sank lower and lower on her breast, until I lifted it with a kiss. 'When you kneel again,' she asked, hiding her face in my neck, 'will you ask him to forgive me?'

"'Yes, darling, I'll ask him now.'

"This time we knelt together, and I implored the forgiveness and mercy of God for us both, and asked that our love for each other might increase, as it certainly would, if we obeyed the rules given us for our conduct in the sacred word.

"I never saw such a holy light on her face as beamed there when we arose. I gathered her in my arms, and vowed while life lasted to do all in my power for her happiness."

DAYS OF YORE.

AUNT MERCY stealthily wiped a tear from her eye, and finding she had no voice to answer, was hastening from the room, when a sweet voice in the hall arrested her steps.

"Oh, I'm sorry I stayed so then! Where is he?" was the hurried exclamation.

Lawrence started forward, laughing, and caught her in his arms.

"Here I am, my truant bird, ready to hear you defend yourself. Why were you not here to open the door for me?"

"Are you really sorry?" she asked, after a searching glance in his face. "I wish I'd been here, for I had a tedious ride, after all. Mamma's friend wanted to shop; and I was so tired of hearing silks and tissues and laces discussed I—What do you think I did?"

"Sat in the carriage and thought of me, of course."

She laughed merrily, exclaiming, as she glanced archly at Aunt Mercy,—

"Did you ever see such a man?"

"He always was a little vain," was the old lady's remark.

"I did, I did!" she exclaimed. "I thought what a kind, patient husband you are, and how hard I would try to be worthy of you."

A softened light beamed in his eyes as he whispered fond words of endearment in her ear.

It was not a light task Mrs. Lovell had undertaken, when she promised her nephew that she would do her best to find and stop the leak. Whenever she stepped her foot into the kitchen, it was the signal for cook, Ann, and Tom to maintain a profound silence. If she asked a question, they either did not answer at all or pretended profound ignorance of the subject in question. The drawers and dressers were thoroughly overlooked, but there the work of reform seemed to stop. The servants took pleasure in misunderstanding her orders. And every day proved the want of a systematic overseer in the household.

One day, after the old lady had delivered a lecture in the kitchen on economy, the dinner was served up in so meagre a style that Mr. Everett, who had brought home guests, ordered it back to the kitchen, and sent Tom to a hotel near by for means to serve a decent repast. It was no time for the old lady to explain, but she made a resolve either to take the whole care of the household, and hire new servants, or to give up interfering with them. She was rather amused to see that Lily did not feel at all involved in the disgrace of having a poor dinner for her husband's guests, but was engaged in watching what he would do in such an emergency. She had not yet learned that it is a wife's duty to see that the money a husband provides for the use of his family is properly expended.

The next morning Lily awoke feverish and languid, with a severe soreness in her throat. Mr. Everett was greatly alarmed, and wished at once to summon the doctor, but she told him she was subject to such attacks, and she thought with some simple remedies, such as Ann knew how to apply, it would soon pass away. She promised to lie quiet, let Ann bring her coffee to the bed, and then try to sleep.

Unfortunately, Mr. Everett had a business engagement which would occupy most of the morning, otherwise he would not have left her. But he sent for his breakfast to be brought to his chamber. Then he sat by the bed and read the account of Christ healing the sick, after which he prayed the good Physician to bestow healing mercy on the dear afflicted one.

"Now," he said, cheerfully, "as I cannot be with you, I shall get Aunt Mercy to come, and tell you some of my pranks when I was a boy; she is very eloquent on that subject."

Lily was delighted; and her husband did not leave her until the old lady was duly installed in her arm-chair near the bed, her knitting in hand, and her glasses exactly on the end of her nose, ready to dilate on her favorite theme.

"Did Lawrence ever tell you," she began, "how I came in the place of a mother to him?"

"He told me quite a romantic story connected with it," answered Lily, her eyes sparkling with pleasure at the thought of hearing it in detail.

"You will laugh, I suppose," the old lady commenced, "at the idea that I was ever called handsome, but there was a time when my cheeks and lips were rosy, my eyes bright, and my hair black and abundant. I was very lively, too, in those far-off days; for the world looked very fair and lovely to me.

"My father was the richest man in the place, being the owner of the large factories that supplied half the village with work. I was, therefore, always kept at school, and was considered quite a prodigy in learning. One winter (how well I remember it!) I was sent to the academy in Leicester. It was at that time the most popular school in the State. It was to be my last term, and I resolved to do my best.

"The teacher, whose name was Everett, was a graduate from Harvard, and was just commencing the study of law. He was dependent on his own exertions for support; and as he loved teaching, he had obtained this school, studying at intervals in the office of Squire Wellington, of Leicester."

For a few moments Aunt Mercy seemed wholly absorbed in her knitting, but suddenly rousing herself, went on.

"It is strange for me to tear away the curtain of time from those early days for you, so much of a stranger, to look in. But I will say, in brief, that young Everett paid me marked attention, which woke an interest for him in my heart. At last, he told me he loved me, and asked me to be his wife. I consented, with the proviso that my parents approved. One Saturday afternoon, he drove to the door of my boarding-house in the handsomest sleigh the town afforded, to take me home, in order to gain my parents' consent. This was not difficult; for he had brought letters of recommendation from men high in rank, whom my father could trust.

"That was a happy Sabbath,—the happiest, I said to myself, that I had ever known; and I looked forward to the future with bright anticipations of many such days. There was only one circumstance which lessened my pleasure, and this was the absence of my only sister, who had gone to pass a few days with our grandmother.

"We returned to Leicester the next morning in season for school, feeling that earth contained no two persons with prospects of happiness fairer than ours.

"I had a new incentive to study,—for I wished my teacher to feel proud of his choice,—and at the end of the term graduated with the highest honors of the school, having received the prizes both for composition and deportment from the trustees, with the chairman of whom I had boarded.

"I went home directly after this, and Mr. Everett returned to Harvard to complete his studies. He couldn't expect to have a home for me for several years, but I was young, and willing to wait.

"Though I had left school, I did not give up my studies. I pursued a course of reading under the direction of my teacher; and much of our correspondence, during two years, was on subjects which interested me, connected with my reading. During the second year of our engagement, I accepted an invitation to visit a schoolmate near the college, and remained there six weeks, seeing Mr. Everett more frequently than I had ever done before. I used often to compare him with other young gentlemen who called, and had no hesitation in pronouncing him superior to them all.

"The next year I had the small-pox, which left some few marks on my face. I have often since wondered that I did not feel more mortification on account of this disfigurement, which, to be sure, every one told me was slight and would entirely disappear in time. But I knew that if my friend was pitted so that nothing of his former complexion could be seen, it would only increase my affection for him, or rather increase the manifestation of it. I would not allow to myself that I could love him more.

"At last, he wrote me that he had been admitted to the bar, that he had opened an office in the pleasant village of W—, and that he wanted me to fulfil my promise to be his. I laid the letter before my parents. My trunks were already filled with preparations for housekeeping. My father had long ago informed Mr. Everett that five thousand dollars lay waiting in the county bank for my benefit; so that nothing remained but to prepare dresses suitable for a bride.

"I wrote an answer that I would be ready in a month. How happy I was then! Three times a week I received long epistles from my lover, full of assurances of his undying affection. Ah, how trusting I was! But the time was hastening when I was to be undeceived.

"I had but one sister, four years younger than myself, a sweet, confiding girl grown suddenly to womanhood. I had from a child been called the beauty of the family, while Charlotte, or Lottie, as we lovingly called her, was plain, but years had improved her complexion as it had marred mine. She was of a happy temperament, flirting from room to room, singing, oh; so merrily!

"Strange enough, she had never seen Mr. Everett, but she often gazed admiringly on a miniature he had sent me, wondering how it would seem to have a brother.

"He came at last, two days before the time appointed for the wedding; for we were to leave directly after the ceremony, and there were many arrangements to be made. There was a stage-coach which passed our house twice in a day. It was by this in the afternoon of Tuesday that I expected him. In the morning, therefore, Lottie and I went out to make calls at the houses of some poor friends whom I might not see again for years. She grew tired, and I urged her to return, while I took a longer route home."

The old lady suddenly caught off her glasses; and Lily could see bright drops standing in her eyes.

"Can't you guess, child, what happened then?" she asked, the words coming with an effort.

"No, Aunt Mercy; Lawrence never told me you had been married twice."

"I thought I had forgotten all that weary sorrow," she murmured. "I thought that I could tell what followed without the dreadful pain at my heart which never left me for years afterward. I reached home soon after noon. Mr. Everett had been there for hours talking with Lottie,—sometimes of me, but more of herself. Why had not I told him, he asked, of her charms?

"Then I made my appearance with the scars on my face brightened by my long and tedious walk. He received me politely, but I saw the change. How I lived through that day and the next, I cannot tell you. He avoided being alone with me until Thursday morning, until within a few hours before the time our friends would assemble, when he demanded an interview. He told me to hate him,—to forget him; his affection had changed. He loved my sister.

"Pride came to bear me up; and when he saw how coldly I received this announcement, he charged me with not loving him as I ought,—that it was well for both of us that the engagement be broken. I did not try to undeceive him. I bowed assent, and went out,—anywhere to be alone,—anywhere that I might rouse myself from this dreadful dream. I thought I had the nightmare; that it could not be true. Only a short time before, and I was so happy! Now what was I? A poor, crushed, despised creature thrown aside as worthless.

"The company came and went. I was missing, and the ceremony could not go on. Mr. Everett went too, but not before he had told Lottie his love.

"My father was a man of easy temper, bound up in his children. I was afterwards told that they found me in an arbor at the bottom of the garden, lying on the ground insensible. The first I can remember I was in his arms, as he carried me to my chamber. I had never before seen him angry, but when I was laid on a couch, and had swallowed some ammonia and water, I heard him use words that made me tremble. He called Everett by every vile epithet he could think of. He summoned Charlotte into the room, and threatened her with being disinherited if she ever dared to speak or write to that black-hearted villain. He seemed to have an idea that all this would soothe me,—would avenge my sorrows.

"It was a long, long time before I could venture forth into the fresh air. I felt that I was disgraced forever. I avoided company; and at last, my health was greatly affected. Our physician advised change of scene; and I went to the West with a cousin for a long visit. There I became acquainted with Dr. Lovell, who knew my sad history from my cousin. He tried to win me to brighter views of duty; and finally, I consented to be his wife. I was to go home for a month, where he would follow me and the wedding would take place immediately. The week before I returned, I received a letter from home, with the startling announcement that, during a visit to a friend in the city, Lottie had been privately married to Mr. Everett.

"The couple then wrote my parents, begging forgiveness, but father returned the letter in a blank envelope. He made a will the next day, leaving every cent of his property to be divided between mother and myself. By one proviso, mother was to forfeit half hers if, as the clause read, she gave anything to her lost daughter. He never seemed to imagine that I should feel any disposition to forgive them."

"But you did,—I know you did!" murmured Lily, the tears running down her cheeks. "You gave her a home, and took care of her boy."

She caught the old lady's hand and pressed it to her lips.

"Well, dear, since you know the rest, I'll end my long story."

"No, please tell me. I do so want to know everything."

"Perhaps you can't understand it, Lily, but as soon as my respect for my old teacher was gone, all my love died out. Dr. Lovell was a very kind husband, and as, by my father's request, he removed from the West, I seemed to have every wish gratified. But sorrow came soon. By a most singular coincidence, my father and Mr. Everett were on a train of cars when there was a collision. Father was not supposed to be seriously hurt, but my brother-in-law was killed instantly.

"Now we hoped father would relent, but he did not. He refused to hear a word in poor Lottie's behalf; and soon disease was developed in consequence of his injury which, after five months, terminated his life.

"I instantly sent for my sister to come to his funeral, but Lawrence was only three weeks old, and she was not able. Dr. Lovell visited her at my request a week later; and she returned with him, a feeble, heartbroken woman. It is sufficient to say that she had not found the happiness in her marriage which she expected. Mr. Everett's temper was seriously affected by their troubles. He was greatly prospered in business for a year or two, but there was a leak somewhere. Poor Lottie knew nothing about housekeeping; and the money he gave her for family purposes was not well expended; and this made him cross. I don't know exactly how it was, but they were always in trouble,—he constantly throwing the blame on her, and she retorting bitterly, until, by his sudden death, she was left penniless."

WHO IS MISTRESS?

IN a day or two, Lily was entirely restored to health. The story of Aunt Mercy had made a deep impression on her mind, causing a shade of thought to rest on her fair features. The old lady she treated with great attention, notwithstanding sundry hints thrown out by Ann that she was a fidgety, fussy, meddling woman; that visitors had better keep in their own rooms, and not interfere with what didn't belong to them.

It was Mrs. Lovell's method to go into the kitchen at the most unexpected hours. Sometimes she arose early and took a general survey of the premises before any one was stirring; and then again she would wait till they had retired for the night; or, she would appear in the midst of the preparation for dinner. Finding she paid no attention to their sullen disregard of her wishes, cook and Tom grew more insolent than ever, and on one occasion bolted the door in her face. To be sure, she might at any minute have caused their dismissal by reporting their conduct to her nephew, but she reasoned that the next set might prove no better; and she was convinced that there were some underhand dealings in the kitchen which, if she could prove upon them, would be a lesson of warning to poor, unsuspecting Lady-bird.

From the first she had suspected Tom. Ever since he could remember, he had lived in the street, from which he had been rescued by Mr. Percival after being detected in petty larceny only to be placed in circumstances of far greater temptation. Besides, his looks were greatly against him. He had a low, retreating forehead, and never could be made to look you full in the face. Many times the old lady had noticed a glance toward his fellow-servants, low, cunning, and malicious, such as had for an instant appeared on his face when notified by Mr. Everett that he was to go to market under the direction of his aunt.

On several occasions, Aunt Mercy, whose eyes were wide open, had noticed glances of warning when she suddenly entered the kitchen; and then the cook had hurried away to the pantry, where she was apparently busy at work when Mrs. Lovell entered. Keeping her suspicions entirely to herself, she became every day more convinced that, aside from the great waste of every article of provision, flour, coffee, tea, sugar, butter, etc., there was a most mysterious disappearance of these articles, especially the latter.

Setting her wits at work, she tried to contrive some method of detecting the plot. Sometimes she resolved to go in person to the grocer and look at the books, but though she might thus ascertain how much butter, for instance, had been ordered, she couldn't say it had not all been used in the family. The more she saw of the servants, the more she was convinced that, unless this terrible leak in her nephew's expenditures could be stopped, he would be ruined.

She had been in the house nearly a month, when her nephew came one morning to her chamber holding a paper in his hand. His face was very grave as he seated himself by her, saying,—

"I have just received the grocer's bill, which I ordered to be sent once a month. It is nearly three, and it has swelled to such an amount that I am frightened. Why, at this rate, our mere living will cost us between four and five thousand dollars a year!"

"More than that, as I have calculated it," eagerly answered Aunt Mercy. "Beside the shocking waste, I'm convinced there's dishonesty in your kitchen."

She related facts on which she had founded her suspicions until he grew very angry.

"I can do no good here," she added. "As you are now situated, I am only one against three; for I feel confident they are all implicated. There must be a thorough overturn,—new servants, new rules. Some one who can be trusted must keep the keys to the store-room, and deal out the articles as they are needed. I wish Lily—"

"Don't expect Lily to undertake such business," he answered, almost petulantly. "The drudgery and confinement would crush her; and then if such an arrangement be proposed, her mother would insist that we should break up housekeeping, and take rooms at some of the fashionable hotels. No, that wont do at all."

He rose and walked back and forth across the room, his brow knit with anxiety. At length he said,—

"It isn't this one bill that worries me. I can pay this easily enough, but it's the idea of living at such a rate of extravagance. I wish you had come to us at first, Aunt Mercy, before these wasteful creatures were established."

A low, timid knock interrupted them, and Lady-bird appeared looking as sweet and happy as though no cares ever intruded themselves into her mind.

"I heard your voice in here," she said, smiling upon her husband. "Are you getting up a conspiracy against me that you look so sober?"

"Yes, darling, a conspiracy to make you more happy," he answered, for the time throwing all his care to the winds.

The next day, Mrs. Lovell noticed that when Lily came to dinner, her eyes were red with weeping. It was so unusual a circumstance to have even a cloud shadowing her beaming face that she would have spoken instinctively of it, had she not met a warning glance from her nephew. A ride was planned for the afternoon, and Lawrence devoted himself to her comfort, as he told her, for the rest of the day.

As he was passing his aunt's room while Lady-bird was preparing for the drive, he looked in and said, hurriedly,—

"No more interference with the servants; let them go on as they please. I will explain when I can."

"'Tisn't right, Lawrence!" She spoke decidedly.

"Hush!" he said. "Lily will hear you. It's only a matter of dollars and cents, which is nothing in comparison with her comfort."

Before she could say more, he had shut the door softly, and was gone. It was not till evening that she saw him again. They had gone to her father's to tea, and returned with some friends, who were to pass the night with them. When the company were talking gayly in the parlor, he slipped away and knocked on his aunt's door.

"I came," he began "to explain what I said this morning. Instead of meeting me with smiles at the door, as Lily generally does, Ann came and informed me that her mistress wished to see me in her chamber. I found her weeping bitterly. Failing to get rid of your interference, I have no doubt it was a plan of the three to appeal to her.

"First, cook rushed to her room, and gave notice of an intention to quit, professing that she 'could live to the end of her days with so swate a mistress as herself, but she couldn't stand interference, and niver could.'

"Then Ann made a pretext of carrying an armful of dresses to the room, and echoed the same story. She was willing to do her best, and thought nothing too much trouble when she could plaze so kind a mistress, but everything was different from what it was when she was hired. She made a great favor of consenting to stay till her lady was supplied.

"Lily had scarcely recovered her breath before there came a request for Mrs. Everett to step to the hall, and spake to poor Tom, who was suffering because he was going away,—back to Mr. Percival's. 'Sure my auld mistress never said a word about my being under any one but yourself, ma'am; and though I'm a poor bye, I values my character too much to stay where I'm not wanted.'

"Ann came back and found her crying, and told a doleful tale of your suspicious looks, etc., ending with,—

"'Feth, ma'am, it's enough to make honest folks rogues to be watching 'em in that fashion, and so I can't risk myself nohow; for I couldn't tell what I'd become with the likes of Miss Lovell put over my head.'

"My poor Lady-bird was terribly grieved by all this, and began to think trouble had come upon her in earnest, but I made light of it. I told her you were a thoroughly good housekeeper, and that I had requested you to look a little after kitchen affairs during your visit, but that it was an awkward job for you, and you'd be glad to be relieved of it. Still she looked very sober, and presently it all came out.

"'Are you sure,' she said, shyly, 'that you are not sorry you took such a useless little girl to be your wife? I'm afraid I'm very, 'very' ignorant about housekeeping. I know Aunt Mercy thinks so, though she is so kind, and I love her so dearly.'

"'You can learn,' I said, encouragingly. 'In time you will become used to care. You are very young yet.'

"'But,' she said, with fresh tears, 'it does seem dreadful to have to think about servants from morning to night, and to keep the closets locked up, as Aunt Mercy says I ought, and give out the sugar and eggs; besides, I never could learn how many were needed for all the puddings and cake that cook makes so nicely. Oh, Lawrence, you can't tell how much I dread to do it!'

"What could I say but that I would arrange it with cook and the rest to stay? I sent for them to the dining-room, and gave each of them a five-dollar bill, charging them to let me hear no more of their going to their mistress with stories of leaving. I saw they thought they had triumphed, and I hated myself for giving them the occasion, but there was no other way."

"You will live to regret it, Lawrence. Lily cannot be happy while neglecting positive duties. How long do you imagine either the cook or Ann will remain content to be servants when they can be mistresses? You have only begun to see the trouble they will give your wife, setting aside all their waste and extravagance."

"I know, I know," he answered, reddening, "but it can't be helped now."

"I shall start for home to-morrow," she added, after a moment's pause. "You will need me more by and by."

There was a most affectionate parting between Aunt Mercy and her niece. Lily kissed her repeatedly, and begged her to come again, not a suspicion entering her mind that the old lady's visit had been abruptly terminated in consequence of what had occurred; while Mrs. Lovell in her turn thanked her young hostess for the pains taken to make her stay agreeable, and reminded her that there was always a home for them in her house.

FARM VERSUS RUM.

LET me introduce you, dear reader, to a tall, stalwart man just opening the gate leading through a potato-patch to an humble cottage. This is his home, and through the open windows he hears the hum of merry voices. There is a smile on his face, and yet not a glad smile. It might have said,—

"They seem happy notwithstanding our misfortunes."

It is a most kind provision of Providence that the young are blessed with buoyant spirits. Troubles come, and are keenly felt, but the cloud soon passes away, and all is bright again.

It was particularly fortunate for Mr. Allen that his children, who were neither few nor far between, were possessed of cheerful, happy dispositions; else on this bright morning, instead of hearing half-suppressed bursts of laughter and joyous exclamations, he might have listened to the notes of sorrow. He entered the open door, and looked within. Even he was surprised at the busy scene.

The room was the largest in the house, used in winter both for a kitchen and sitting-room. At this moment it was littered with split-cane, bundles of which lay in one corner, and from which Lizzie, the oldest girl, had just taken a quantity, which she was slowly weaving into a chair for the benefit of the eager lookers-on. John, Mary, Bell, Carrie, and ever so many more, of all ages, from fifteen downward, were pressing as near as possible to the frame, while the baby, springing in its mother's arms, was trying to catch the end of one of the canes as it was alternately woven over and under the others.

But I cannot expect my reader to understand why the heart of Mr. Allen was filled with remorse and sorrow, instead of pleasure, as he silently gazed on the noisy group, or why the pale, careworn face of his wife smote him with a sharp pang of regret.

Mary Walbridge, own cousin to Lawrence Everett, was the fairest of all the maidens in the village of N—. She had scores of admirers; indeed, there was scarcely a young man, either in her own or the neighboring towns, but would have thought the gift of Mary's hand the richest boon he could ask. But, though the young girl was kind to all, her smiles were given alone to Joseph Allen, son of their nearest neighbor; and her parents approved her choice.

Joseph was an only son, the heir to his father's broad acres, extending full two miles on the banks of the beautiful C— River. He was a merry youth, always welcomed by young and old, prepossessing in appearance, moral and upright in character. Beside all this, he loved Mary with all the strength of his manly heart. He could not remember the time when he did not love her; and so they stood together before the white-haired clergyman who had married their parents, and had known them from their infancy, and gladly took the solemn vows which made them one.

Only two years did the young wife minister to the parents of her husband,—for she went at once to live at the farm. At the end of that period, Mr. Allen died; and as his wife soon followed him to his quiet resting-place beneath the willows, Joseph became possessor of the whole property.

Mary's prospects of happiness were now very fair. Her little daughter Lizzie, named for her husband's mother, was the picture of childish beauty, and she had but to name a wish in order to have it gratified.

Joseph, or Mr. Allen, as he was now called, had always attended school in the winter until two years before his marriage. He had quite a gift at speaking, which he was very fond of improving, and often astonished the old settlers by an earnest appeal at the town-meeting for money to be granted for a new and improved school-house.

When Mary had been married five years, she had four children. She had grown quite matronly in form; there was a richer bloom on her cheeks, and a deeper, holier light in her eye than on her wedding-day.

Mr. Allen was considered one of the most rising men of the town. He already had been chosen a member of the school committee, and had the pleasure of giving the land for the new and commodious building where his little Lizzie commenced her education. But, alas, all these bright prospects were to pass away! The glorious morning was to be shaded with clouds, and would rise to a tempest long before the sun reached the zenith.

Having abundant means, Mr. Allen did not feel it incumbent on him to labor,—at least, not as his father had done. He hired men, and bought patented machines with which to work his farm. His own time, he thought, could be more profitably spent for the good of the town. Committee meetings, caucuses, and State conventions, roused his abilities, and kept his mind at work. He was thoroughly alive at such times, and liked the excitement. As his family rapidly increased, instead of sharing the care and responsibility with his wife, he grew more and more ambitious of town offices,—more and more fond of meeting his neighbors at public dinners.

It was a long, long time before poor Mary would own to herself that her beloved husband had begun to crave the drink which intoxicates, but at last, the evidence became too conclusive. Once, in the depths of winter, he came home at midnight too much lost to reason to know that he was not sleeping in his bed. His wife, who for hours had been listening to every sound, heard the sleigh-bells as the horse turned into the barnyard.

After waiting nearly an hour for him to come in, she aroused her oldest boy, and they went together to the barn, their hearts throbbing with an unknown dread.

The faithful horse had returned to his home, and gone directly into the open door, where he was patiently awaiting attention, while his master lay in the bottom of the sleigh in the deep slumber of the drunkard.

The united efforts of mother and son could not rouse him, or drag him farther than the floor of the barn, where they made a bed of hay for him, and having led the more sensible beast to his stall, retired to weep over this new and dreadful affliction.

From this hour, Mr. Allen's path was downward, till, when Lizzie was fifteen years old, they were turned out of their loved home by the man whose rum had been exchanged for it, and removed to the small cottage in which we find them with barely furniture enough to render it habitable.

Mrs. Lovell witnessed the gradual downfall of the husband of her niece with deep solicitude. Many and many a time, the pecuniary assistance she gave was all that kept them from actual suffering. A little time before their removal, the poor inebriate had a short return of consciousness. He really desired to reform, and, with many sighs, promised Mary, if Aunt Mercy could be induced to buy the mortgages held by the rumseller, and give him a chance to earn them back, he would sign the pledge of total abstinence.

But the old lady had no faith in his perseverance. She encouraged him to show his penitence for the past by giving up, at once and forever, that which led to his ruin. She reminded him that his intemperate habits more than his years had made an old man of him; that he had a large family dependent on him for support,—children that might grow up an honor to society, but whom his evil example might corrupt; and she urged him to stop the leak in his fortune by vigorous efforts to reform.

At this time, too, Lizzie, his favorite child, persuaded him to accompany her to a lecture on temperance. He listened to accounts of those who had been sunk in degradation far below him, but who had broken the bonds of their evil habits, and come forth from the gutter restored to their manhood. He resolved to add one to their number. His daughter watched him, while tears unconsciously stole down her cheeks. At the close of the lecture, he arose in response to the speaker's invitation, and walked slowly up the aisle, while Lizzie bowed her head on her hands and wept tears of joy.

When Mr. Allen left his home, therefore, he did it with the full consciousness of all he had lost,—that he had sinfully wasted the patrimony bequeathed him by his parents; had deprived his wife of the comforts he had taught her to expect, and his children of the means to acquire an education.

When Aunt Mercy saw that the reformation was lasting,—that her nephew acted like a sober, penitent man, she offered to assist them to stop the leak he had made in their fortune. It was by her advice they moved to the town of G—, where work for himself and the children could be obtained. She herself placed Lizzie where she could learn the art of seating chairs, and then supplied money to purchase a quantity of the material. This would furnish employment for the girls and the second boy. For John, the eldest, named for her husband, she had other plans. She wished, however, to ascertain more of his capabilities for business, and it was for that purpose, on her return from the city, that she rode twenty miles out of her way to visit her niece in her new home.

The change from the princely mansion of Lawrence to the lowly cottage of his cousin was as great as could well be imagined, but Aunt Mercy enjoyed herself quite as well in the hut as in the palace. To be sure, it sounded strangely, while sitting in that uncarpeted room, the filthy walls of which the new inmates had felt most happy to be able to cover with sixpenny paper, to talk of the style and splendor of Lawrence's appointments, of Lily's luxurious chamber and costly dress, and feel that the near relation of cousins united them.

The children's fingers flew rapidly over their allotted tasks as, hour after hour, the old lady described the sweet Lady-bird her nephew had won for his own, or told of the terrible leak in their housekeeping.

"I'm just as sure how it will end," she exclaimed one day, laying aside the garment she was patching for her niece, "as I was when Joseph began to stay out late to those public meetings and caucuses, etc.! 'Twouldn't take a prophet to see it either. The difference between his case and yours is, the money's running out of his leak, while you've all undertaken to stop yours."

Mr. Allen had been so fortunate as to obtain regular employment in a nursery near his home. But still, with all their economy, Mrs. Allen could see it would be difficult to provide food and clothing for so many little ones. She had been so accustomed to have milk, butter, eggs, and cheese from the farm, besides vegetables, grain, and pork, that she scarcely knew how to cook, when every one of these must be bought with scanty means at the grocer's. There were five girls and four boys, beside herself and her husband, to provide with clothing. The house, poor as it was, with the little strip of land by the side of it, rented for eighty dollars; and then fuel and lights were to be bought for the approaching winter.

Mrs. Lovell was scarcely surprised that Mr. Allen should often be plunged in despondence. He went regularly to work, struggling day after day against the craving of appetite for drink, but seldom smiled. The sad contrast between the present and the past rose continually before his mind, while conscience, with a voice like thunder, seemed ever echoing in his ears,—

"This is your work!"

A RAY OF SUNSHINE.

AS I have before said, Mr. Allen was naturally mirthful; and the change in his temperament would have cast a gloom over all the family, had it not been for Lizzie, whose merry face and sunny smiles chased away many an hour of despondence.

Aunt Mercy was a shrewd observer of character. As she had before talked in the plainest terms to her nephew of the sin of pursuing a course which was not only ruining his own soul, but the peace of his family, so, now that she saw he was striving to amend, in her own frank way she strove to encourage him. Entirely ignoring his silence on all such occasions, she persevered in consulting him regarding the children. Lizzie, she said, as soon as times were a little more prosperous with them, must be sent to a Normal school, and prepared for a teacher.

"There is a vacancy now," she added, hopefully, "in our district. I wish she were ready, for she would be good company for me."

Joseph would not glance toward the bright eyes he was sure were asking his consent, but answered, in a hard tone,—

"Wife couldn't spare Lizzie; and money wouldn't tempt me to let her go back to N—, where she would be pointed at as the drunkard's daughter."

"That would not be true now, husband," murmured his wife, softly laying her hand on his shoulder.

"I have a plan for John too," the old lady went on, "but it is a secret as yet. There is no need of haste; he must get a better education first."

"Bread and butter is the first object with us," was the bitter retort. "You forget that we are poor."

"I know as well as you do that your money has all run away," she answered, smiling, "but I know, also, that you are all taking hold in earnest to stop the leak. And, as I have a little money lying idle in the bank, I suppose there is no one to forbid me the pleasure of helping those who are trying to help themselves."

Mr. Allen's chin quivered. "Wife and Lizzie will thank you," he said, in a subdued tone, "but my feeling is all gone."

"Not quite, father!" exclaimed Bell, throwing her arms around his neck. "For I heard you telling Mr. Grey last night that you would bear your own lot without a murmur, if your family need not suffer, and the tears glistened in your eyes."

Mrs. Lovell often noticed that Mary, when her husband entered the room, glanced shyly at him, to see whether the boisterous mirth of the children was likely to annoy him. They kept steadily at their task of seating chairs until near the hour in which he returned from his work, when they bounded out of doors, chasing each other all over their small enclosure, and making the air ring with their laughter.

She well remembered the time when, in the earlier years of their married life, Lizzie, John, and Bell used to run down the road as soon as they heard their father's carriage-wheels, when he good-naturedly stopped the horse and took them all in. Now for many years he had been so fretful and capricious under the influence of liquor that they had avoided him as much as possible, quietly stealing from the room when he was in it, so that Jamie and Fred., the younger boys, were almost strangers to him.

Aunt Mercy took occasion one day to call up the old reminiscences, and afterwards told her niece that she was quite sure it would please Joseph to be welcomed by the children as of old.

Lizzie, who was old enough and wise enough to be taken into the family counsels, entered into this proposal with her usual enthusiasm. Jamie, Fred., and even Baby Nelly, after this, each had his or her lesson, and the next afternoon, when the unsuspicious father came walking gloomily down the road, they all set out to meet him.

"See, pa!" cried Fred., reaching up, and pulling his father's coat to attract attention. "See what I've got for you!" And he held out a prettily-arranged bunch of wild wood flowers.

"Nelly, too!" lisped the baby, reaching her arms out toward him.

Jamie presented his offering with a quiet smile. He was the image of his mother in her happier days, and his upturned face reminded the husband so forcibly of her that, when he tried to speak, the words choked him.

"What does it mean?" he asked, presently, turning to Lizzie, whose kindling eye expressed volumes.

"Only that we have been telling the little ones how we used to run out and meet you, and they want to welcome you too."

He leaned forward and kissed her, saying, softly,—

"If I ever do become a good man, Lizzie, you will be the means of it."

"That is because I pray 'for Christ's sake,'" she answered, in the same tone.

Mrs. Allen was greatly delighted to see her husband come across the potato-patch with baby sitting on his shoulder. She stood in the doorway, with a smiling countenance, to receive him, Aunt Mercy and John pressing up behind her.

The meal which followed was the most cheerful one they had enjoyed since they came to G—, Mr. Allen exerting himself to talk, and telling them more about his business than they had ever known before.

BRIGHTER DAYS.

The next morning at breakfast, Aunt Mercy said, "I wish you had a barn, Joseph; for I think I could find you a cow. The little ones would grow fatter if they had plenty of milk."

"I like milk!" exclaimed Jamie, warmly.

"And we could make our own butter," said the practical John.

"I know Mr. Burrel, where I work, would be glad to let us pasture a cow with his, if one of the boys would drive both of them," added the father, "but we have no barn; so it is of no use to talk about it."

"I'll build one with the first money I earn teaching school!" exclaimed Lizzie, laughing, and there the subject was dropped.

But Mr. Allen thought of it again, as he walked back to his work. He thought, also, of a remark he had that very morning overheard his employer make to a neighbor in regard to himself, and this was,—

"He's the most faithful, energetic man I ever knew. If he only had more enthusiasm in his nature, I'd advance him at once to be head gardener; for I see he's well informed."

The neighbor answered, "He owned a fine piece of property once, I've heard, but was unfortunate, and lost everything."

For the first time, a feeling that there might be hope for him in the future quickened his steps, and almost brought a smile to his lips.

"If I could get that situation," he soliloquized, "I should have the pretty cottage on the grounds, and Mary could have the cow at once. A dozen quarts of milk in a day does make a vast difference in the expense of living."

Mrs. Lovell lengthened her visit from week to week, because she saw she could be a help to her niece. A few dollars well expended made a sensible improvement in the comfort of the family, and a few more bought cloth, which Aunt Mercy's own hands made into garments greatly needed.

Then the thoughtful old lady had begged a number of articles from Lawrence, which she had foreseen would help replenish the wardrobe of Mr. Allen against the coming winter, and enable him to accompany his wife to church; for it was her earnest desire that the whole family should be under the influence of faithful religious teaching. But at last, the alterations necessary in these were completed, and Mrs. Allen could find no excuse for urging her aunt to prolong her visit. Mrs. Lovell's trunk was packed, and she only waited for a letter she expected that morning from Lawrence before she started for home.

At last Jamie, the news-carrier, as he called himself, came in sight, holding up an envelope, and shouting,—

"It's for you, Aunt Mercy; the letters are always for you!"

Though the old lady did not read it to the eager lookers-on, but mysteriously folded and placed it in her pocket, we will take the liberty to peruse it.

"DEAR AUNT,—If the boy is what you describe, I will give him a start,

as you call it, but he must be very honest, active, and go-ahead,

in order to succeed here, where there are so many competitors for

fortune. He ought to be well grounded in arithmetic, and have a general

idea of bookkeeping, though he may never advance beyond a runner, or

errand-boy. I think well of your keeping him with you for the winter.

"As to our own affairs, I suspect I made a mistake when I gave the

reins so completely into the hands of our kitchen functionaries. To

speak within bounds, they are four times as extravagant as when you

left. Indeed, the way they manage to treat their own guests, and cheat

ours of everything that is eatable, would furnish abundant material

for a modern novel-writer to publish a book entitled 'High Life below

Stairs.' Where all this tends, I am beginning seriously to inquire.

In the mean time, Lady-bird is just as sweet and beguiling as ever,

singing and smiling in the most delightful unconsciousness that

everything is not proceeding in the most approved manner. It is barely

possible that I may be obliged to go to France for a month or two in

the winter. If I do,—but I will write you further at another time.

"Yours most gratefully,

"LAWRENCE EVERETT."

POLICE AND CRIMINALS.

"OH, Lawrence, what do you think has happened?" exclaimed Lily, one day in early autumn, running to the door, as she heard his familiar ring.

"Perhaps I can guess," he answered, with a sad smile.

"Did papa tell you? I have been waiting so impatiently to ask you about it! To think of mamma being willing to start off in such a hurry, and then to sell the house and furniture! She thinks we had better take the carriage and servants, since ours are beginning to be troublesome, but it is all so strange and sudden, it quite takes away my breath."

He took her hand and led her to the sofa. Then, carefully closing the doors, he seated himself beside her, and said,—

"Don't excite yourself, Lily, and I will tell you why it is necessary that either he or I should go. I would have told you before, only that I hoped the news by yesterday's steamer would have been such that all danger to our firm would be averted. Your father, you know, has had dealings with a large house in Paris for many years. We sold goods for them on commission, and a very profitable business it has been for both. Last month we heard that they were greatly embarrassed, but hoped, in a few weeks, to be relieved by the payment of large sums due them from India. Yesterday the news was so far from encouraging that it becomes necessary for one of the partners to be in Paris at once to prevent immense loss."

Mr. Everett spoke calmly, but with deep seriousness, and Lily, who was closely watching him, said,—

"And was it this which prevented you from sleeping last night, and made you look so very sober?"

"Yes, darling, I cannot deny it. I fear a great crisis is before us."

"Why don't you go yourself then? Papa says he confides greatly in your judgment."

"He proposed it, but he is better acquainted with the business there than I am; and then I could not leave you, Lily. I might be detained six months or a year. We talked it over last night, but it was not fully decided till this morning."

"But why does papa sell his house? He can never get another that he will like so well, and the beautiful furniture that mamma has taken so much pains to select."

He drew her closer to him, as he said, "Because it is certain that our loss will be great, though we hope to save something from the wreck. It is a terrible misfortune that has come upon us, darling. I look to you to help me bear it patiently."

Oh, what a beaming smile she gave him! But he sighed deeply, as he said to himself,—

"Poor child, she little knows the trials before her!"

"If all happens in Paris that you fear, shall we be very poor?" she asked, innocently.

"Yes, Lily; we shall have to leave this beautiful home. I can no longer surround you with luxuries, or buy you freedom from care. I shall have to begin life anew, and how will you endure the change?"

He leaned his head on her shoulder, that brave Christian man, and sighs that not all his trouble had caused, now made his breast heave as he thought of her.

For a moment, the news was overpowering. Lily had, from her birth, been surrounded by every elegance that wealth could create. She could not quite realize what all this change would be. But she was a true wife, and the first thought, after the stunning blow, was pleasure that she had it in her power to comfort her husband. She looked in his face with a smile, though her lips were tremulous and her eyes dewy, and said, softly,—

"But you will have your Lady-bird still, and I can learn to work and help you."

Oh, how he pressed her to his heart, and told her she was worth more to him than a thousand fortunes! How he thanked her for bearing it so nobly!

"You have stolen away my burden," he said again and again. "My greatest fear was for you."

They talked a long time, unmindful of the repeated summons to dinner, and then Lily, who had been trying to comprehend the detail of business, whispered,—

"I read yesterday how the disciples, when they sorrowed, went and told Jesus. I thought it so beautiful! Wouldn't he hear us if we told him now, and asked him to help us do right?"

They knelt together side by side, while the husband poured their sorrows into the ear of a sympathizing Saviour. Then they arose and were comforted.

"Can you spare time to go round through the square with me?" inquired Lily, as they arose from the mere form of eating. "I must be with mamma all I can before she goes."

"Yes, Lily, but before that, I propose Aunt Mercy should come back and help you get rid of the servants. She is a great manager. If I had taken her advice, I should have been some richer than I am now."

"I will write a note asking her."

He nodded assent, and brought her portfolio from the library, waiting with some curiosity to see what she would say. The note began:—

"You will wonder, Aunt Mercy, when you read this. Lawrence and I are

no longer rich. We are quite poor. We are to leave this house, but

it is not decided where we shall live. Mamma goes with papa to Paris

immediately, to try to save some of the money there. Will you come

and help me learn to be economical? I cannot be grateful enough that

Lawrence has told me all about it, and lets me comfort him. I feel very

happy, but Lawrence says it is because I don't realize what is before

me. We shall see who is right. Please come as quickly as you can. Your

loving niece,

"LILY."

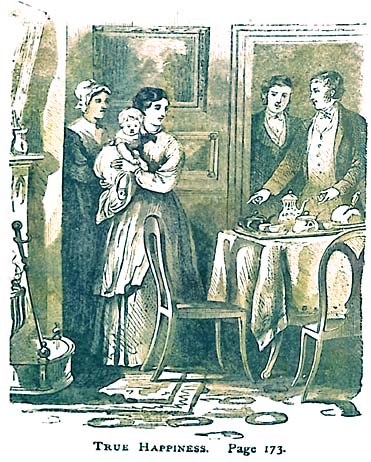

In twenty-four hours after receiving the above, the old lady landed at her nephew's door. She was received with open arms by Lady-bird, who, excepting that she was pale from a headache the previous day, looked bright and cheerful as a May morning.

Presently Lawrence came in with a clouded brow, and, after saluting his aunt with a kiss, exclaimed,—

"There is some rascality in this! Here is another bill from the grocer's. We have never consumed this amount! Aunt Mercy, I wish you had shipped the whole pack when you were here before."

"I don't imagine Tom was overjoyed to see me," she said, quietly. "He scowled when he opened the door."

"We must get rid of them all at once, but take off your bonnet, and we will talk about our arrangements. Mr. and Mrs. Percival sail to-morrow, leaving me to dispose of their house, furniture, horses and carriages, to the best advantage the times will allow. I suppose the whole may bring thirty thousand dollars,—perhaps a third or quarter of what they cost; and that is every cent they will have to live upon, unless our affairs in France terminate more favorably than we dare to expect."