Title: Paul Harley's dream

Author: A. L. O. E.

Release date: October 19, 2025 [eBook #77088]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Marshall Brothers, Ltd, 1906

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

[AND]

[JOE'S LETTER]

[A New Year's Story]

BY A.L.O.E.

Author of "The Claremont Tales,"

"The White Bear's Den," &c.

MARSHALL BROTHERS, LTD.

LONDON, EDINBURGH.

CONTENTS.

——————

BY A.L.O.E.

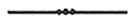

"It stops all fun!" cried Paul.

PAUL HARLEY'S DREAM

A Tale.

——————

PAUL.

"I DO think it, and I will say it!" cried Paul Harley, with impatience. "Of all days in the week, a Sunday is the worst for New Year's Eve. It stops all fun, all larking, all hope of adventure. The New Year steals in like a thief when one is fast asleep in bed; unless, like that stupid fellow James Barton, one goes to some midnight service in church, to pray in the New Year, as he says. As if one had not had enough of that sort of thing all the Sunday!"

"My dear boy—" began his grandfather, Silas Harley, an aged man, who sat with his arm leaning on the table, and his Bible before him.

What Harley was going to say I cannot tell, for his grandson cut him short. Paul had been to school, and had learned many things there, of the knowledge of which he was not a little vain. But one thing, worth more than mere book-lore, he had not learned, which was to honour his father and his mother, which includes grandparents also. Paul was puffed up with pride, as a balloon is puffed out with gas.

He stood erect by the table, grasping the back of a chair, and looking down on the venerable man before him, whose white hair Paul should have honoured, with a saucy look, which seemed to say, "I don't want advice from you!"

"I wish that I could do this year what I did on last New Year's Eve," cried Paul. "A lot of us young fellows got on the top of a coach, and were off to Enfield for a spree at a farm. How the horses plunged through the snow; we were upset as nearly as could be!"

"No great fun in that," observed Harley.

"We had no end of snow-balling each other at Gale's farm, as long as daylight lasted," continued Paul; "and when night came on, we had dancing 'under the misletoe bough.' Ah! That night, what a merry one it was! We were just in the midst of a dance, hands round and down the middle, when the clock struck twelve, and in came the New Year!"

"And Sunday too," observed old Mrs. Harley, who was seated by her husband. "I hope, Paul, that you left off your dancing?"

Paul only, in reply, gave a saucy laugh, which pained his good grandparents. They had brought up the orphan boy ever since he had been a helpless baby, and had now, in return for their loving care, but disrespect and disobedience.

On the year of which I am writing, the thirty-first of December fell on a Sunday, and it was on the evening of this Sunday that Paul stood talking to his grandparents in the little parlour of their home, in one of the suburbs of London.

"We were sorry not to have you with us at church this morning, Paul," observed Harley. The old man and his feeble wife had with no small difficulty made their way to the house of prayer, to praise their Maker for mercies received through the closing year, and to ask for His blessing on the year so soon to open. The New Year to one or both of them, as they thought, was likely to be the last, but neither of them feared to "go home" to the rest prepared for the people of God.

"I don't care to go to morning service," replied Paul, bluntly; "I take my ease, and lie late in bed on Sundays, at least in such freezing weather as this. But I mean to go to-night to seven o'clock service; for I like to see the church all lit up, with the gas-lights flaring on the evergreens and the wreaths with which it is decked. I like, too, the hymn which is to be sung, it has such a pretty tune." And without the least reverence of manner, Paul rather bawled out than sang the first lines of a well-known hymn—

"'A few more years shall roll,

A few more seasons come,

And we shall be with those who sleep

At rest within the tomb.'"

"Hush, my dear child, hush!" cried Mrs. Harley, with a shocked look. "You don't seem to think of the meaning of the words which you are singing."

Paul took no notice of the gentle reproof. "It's time for me to be off to church," said he; "it must be just on seven; I think the bells have stopped their ringing. Don't stay supper for me; I'm going to Uncle Sam's after I've been at church; he's to have lobster salad for supper on New Year's Eve, and I like that a deal better than your porridge. I mean to stop the night at Uncle Sam's, and get some fun with his boys on New Year's morning."

"Take your comforter!" cried the grandmother. "You're not the lad to stand sharp cold; remember that you nearly died of rheumatic fever last March!"

"I'm not going to coddle myself like an old woman!" exclaimed the boy. "Cold only catches those who have to creep like snails!" Paul took down his cap from its peg as he spoke, and went off to church, certainly not in a mood either to praise or to pray.

The church was not full on New Year's Eve, for the weather was so extremely cold that some persons who would otherwise have come, dared not brave the piercing night air. Paul took his usual place in a dark part of the church, where he could see without being much seen. He sat during the prayers, and stared about him. Paul looked at the wreaths and the gas-lights, noticed the fashion of the ladies' bonnets, and amused himself with his own thoughts. There was no reverence either in the posture or in the spirit of Paul. He behaved himself in the house set apart for the worship of the Almighty as he would not have dared to behave in the Queen's palace; nay, as he would not have dared to behave in any gentleman's private dwelling.

Paul's body was in church, but his heart was not there. Now he thought of to-morrow's sports, now of his lobster supper. Then the lad's thoughts took a more evil course. Malice and spite were shown in such reflections as these:—

"I wonder how that James Barton can bear to stay up till midnight in a church! 'Pray in the New Year,' to be sure! That may be well enough for old folk, who are not likely to live many more years, but young chaps like James and me have fifty or sixty before us, and I can't see the use of all that praying. James wants to be thought better than any one else. He has given up playing skittles on Sundays, and has taken, I hear, to keeping a missionary-box. Catch me following his example! I've something better to do with my pennies.

"I don't like James Barton at all. I have owed him a grudge ever since our quarrel in a field three years ago, when he got me into a scrape with a farmer's wife by saying I'd stolen her apples. I've been on the watch ever since to pay him off for that bit of mischievous meddling. If I did take the dame's apples, that was no business of his. Fine fun I had last summer, when I crept up unseen to the neat model of a ship which James had taken weeks to rig out, and tore her sails, and knocked a hole in her keel, while he was wandering about in the brushwood gathering flowers and ferns! I made off as soon as I had done the job, but I'd have liked to have seen the lad's face, when he came to the place where he had left his pretty ship, and found her lying broken and spoiled in the mud! I wonder if he guessed who had played him the trick? He did not see me, I'm sure of that, for I stole away like a fox. I suppose that James has now grown so mighty good that, had I smashed him instead of his ship, he'd have taken it as meek as a lamb. The next time that we meet, I'll try how he likes a box on the ear."

But I will put down no more of the worse than idle thoughts which, even in church, passed through the mind of the boy. I have said quite enough to show that Paul did not for one moment reflect that he was in the presence of his Maker; that the eye of God was upon him; that his secret malice was laid bare unto Him who hath declared in His holy Word, "The thought of foolishness is sin," Prov. xxiv. 9.

Paul only gave over making plans for teasing James when the clergyman gave out the hymn. We have seen that Paul was vain; and of nothing was he more vain than what he considered to be a very fine voice. A loud one it was, without doubt, and Paul took care that it should be heard all over the church.

A lady, speaking of church music, once said to me, "It makes me tremble to hear the children sing." My readers may think these very strange words, but to my mind there was cause for the lady's feeling of fear. Oh, my young friends, have you ever thought how you may displease the Lord, even whilst singing a hymn! "Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain; for the Lord will not hold him guiltless who taketh His name in vain." Is it a light matter to sing of the glory of the Almighty, or the agonies of His dear Son, as carelessly as if you were but shouting out some idle ballad? A dark stain of sin was spreading over the soul of Paul as he boldly sang out, at the top of his voice, even words so solemn as these:—

"''Tis but a little time,

And Christ the Lord shall come

To take His ransomed people up

To their eternal home.

Then, oh, my Lord, prepare

My soul for that great day;

Oh, wash me in thy precious blood,

And take my sin away!'"

Paul's hymn-singing was a mockery; his very prayer was "turned into sin!" What thought he of the great Day of Judgment? What thought he of the "precious blood," of which he dared so loudly to sing?

THE DREAM.

THE hymn was over, and Paul sat down, but not to listen to a word of the sermon. Good and holy words were spoken, which touched most of the hearers' hearts, but they never reached the heart of Paul. The boy fell fast asleep in his dark corner of the church, and there he remained fast asleep till long after the sermon had been ended, and the blessing had been given by the preacher.

Paul not only slept, but he dreamed—a strange and wondrous dream. The place in which he was seemed to widen, the roof to rise, till instead of a ceiling above him were clouds of glory, and beneath him a pavement of gold. There was music, but far sweeter, and more joyful than what Paul had heard in church. Instead of mortal men and women, shining, happy beings were around the dreamer, with starry crowns and waving wings, that glittered like jewels in the glorious light.

But though all that Paul saw in his dream was beauty and gladness, he could not delight in the beauty, he could not share in the joy. Paul's heart felt nothing but dread. He did not belong to the happy band; he could not join in their song; he feared lest one of the shining ones should notice that he was there. Paul would fain have hidden himself, but had no place wherein to hide. Terror seized him when one of the beautiful angels drew near, and said, "What dost thou here?"

Paul was dumb, and could not reply. The proud tongue which had so often repeated holy words without fear had lost all power to utter one now.

Then Paul seemed to hear the sentence, "Thrust him forth into outer darkness!" And the start of terror which he gave awakened the boy from his dream.

Paul found himself indeed in darkness. The lights in the church had all been put out; the worshippers had gone to their homes; no one had noticed the sleeping boy, and he had been locked into the church.

Paul's first feeling was that of great surprise at finding the church so still and so dark; his next was that of alarm. He groped his way to the outer door. How still and dark the place seemed as he moved down the aisle! And, oh, how terribly cold! The clock struck nine just as Paul reached the great door. It was locked. Paul shook it, and shook it again, but had no power to force it open. He called as loudly as he could, but the church stood in the middle of a large churchyard, no house was near, and no one heard the boy's voice.

"Some one will search for me, oh, surely some one will search!" cried Paul.

He thought of his loving grandparents, who, old and feeble as they were, would be sure to brave the piercing cold if they know that their boy was in danger. But then another thought startled Paul. "Grandfather will think that I am at my uncle's; he will fancy me seated at his table beside a blazing fire."

The contrast between his uncle's pleasant home, with its supper and cheerful blaze, made his present dreary position seem worse than ever to the hungry lad. But Paul tried to keep up his courage and warm his chilled frame by walking up and down the part of the church which was nearest to the door, stamping his feet and swinging his arms to keep out the cold.

Ten o'clock struck. Paul counted each stroke on the bell. How loud and solemn was the sound!

"Only ten!" muttered Paul. "I shall have to wait twelve whole hours before this church is opened to prepare for New Year's service! The New Year!" he repeated. "Oh! In how wretched a way I shall begin the New Year! I'll go to sleep in one of the pews, and so try to get over the time. The night grows colder and colder."

Paul did snatch a short sleep, but awoke quite cramped and chilled, and with shoots of rheumatic pain, which frightened him more than anything else. It was one of the bitterest nights that had ever been known in England. The boy dared not sleep again lest he should bring back his dreadful rheumatic fever.

When eleven o'clock struck, Paul's courage quite gave way. His limbs were trembling, his teeth were chattering, his blood seemed turning to ice. He remembered that his grandfather had read in the papers the day before that four persons had been found frozen to death.

"What if I should die before morning!" thought Paul, and it was a terrible thought. "I am not fit to die, I am not fit to go to the beautiful place of which I was dreaming. Hark! What is that tinkling sound which I faintly hear? The bells of St. John's Church are ringing for the midnight service; James Barton will be hastening now to that church to pray in the New Year. Oh, that I could pray too!" It was the first time that such a wish had come into the mind of Paul. He had attended church service hundreds of times, but he had never really prayed in his life.

"I can't pray, I can think of no words," groaned the poor boy, as he swayed his body to and fro; for he was afraid to remain quite still, and yet was almost too stiff and cold to move about freely. "Perhaps that hymn may serve as a prayer; I'll try a verse; it may help me to forget for a few minutes the misery that I am in."

In a very different way from that in which he had sung a few hours before, Paul, with trembling voice, attempted to sing—

"'Then, oh! my Lord, prepare

My soul for that great day.'"

Paul felt that for him the great day might be near. He no longer felt sure of "fifty or sixty years" of life. He knew now that he had need of comfort, of help, of forgiveness. Paul clasped his numbed hands, and tears came into his eyes as he sang the words of entreaty—

"'Oh! wash me in Thy precious blood,

And take my sins away.'"

But how much better was Paul's feeble prayer for mercy, than his late bold, careless singing of words so solemn and holy!

Twelve o'clock struck. The New Year had come! Some in London were praying, many were sleeping, not a few, alas! were drinking in the Now Year. Again Paul tried to get warmth by walking about, but the frost was becoming more intense as the night advanced. The moon had now risen, and dimly shone through the frosted windows. Paul could distinguish some objects near him, such as the reading-desk, on which lay the large Bible, that Bible which had been read so often in his hearing, but to which he had never cared to listen.

"If I live through this dreadful night, I will try to be a very different boy to what I have been," thought Paul Harley. "I will try to be more dutiful to my old grandparents; they have had little comfort in me. What would not I give now to be more like James, whom I despised for being so pious! There is no danger of his being driven into outer darkness. The angels will welcome him, for he loves the Lord whom they love."

The weary, weary minutes stole on. It was now nearly one o'clock. Drowsiness was creeping over Paul, but he knew the danger of sleeping when the cold is intense; if he slept now, he might never waken again, or waken in torture.

"I can only keep myself awake by singing," thought Paul. "I will sing that hymn over again, and try to think of the words, and to make them indeed a New Year's prayer."

Paul sang, and this time loudly, for he was calling on God from the heart, and so threw his whole soul into the hymn.

"Who is singing there—at this hour?" cried a voice from outside.

Paul sprang to his feet with almost a cry of delight.

"I'm Paul Harley—I'm locked in—I'm almost frozen!" he shouted with the utmost strength of his voice.

"Paul Harley!" echoed the speaker without.

"Oh! Run, run—quick as light—and get the key of the church!" cried Paul.

"Trust James Barton for that!" cried the voice, and off rushed the speaker at full speed.

Yes, it was James, who, returning from the church where he had prayed in the New Year, had taken his homeward way through the churchyard of that in which poor Paul was looked up. It was not James' shortest way home, but he had chosen it because St. Mary's church and churchyard would look, he thought, so beautiful in the moonlight, robed in their winter mantle of snow. James had been not a little surprised to hear the sound of Paul's hymn in a spot so lonely and quiet. But for that sound, James would have passed the church without suspecting that any one was shivering and starving within it.

I have not space to describe how James ran, as if for his life, to the house of the clerk of St. Mary's, and rang so furiously at the bell, that the poor man, his wife, and all his family, thought that the place was on fire. It is enough to say that James was trusted with the church key, for his character was known to the clerk, and back he hastened to the church. The big key was turned in the lock, the heavy door swung back on its hinges, the imprisoned Paul was set free; and with what a hearty grasp of the hand did he thank his kind deliverer!

"Come to our home for the rest of the night," said James; "mother will bid you heartily welcome, I'm sure of that. She is sitting up to give me my hot supper on my return from church, and I need not say how glad I shall be for you to share it."

Very thankfully was the invitation accepted. Paul felt as if new life were poured into his frozen veins when he sat by a glowing fire, and drank hot steaming soup. Before he went to rest, he had confessed to James the wrong he had done him by spoiling his ship, and asked forgiveness for that and other acts of unkindness.

"Let bygones be bygones," said James, smiling; "this is New Year's day you know; let us both resolve, by God's help, to begin it well, and make a better use of our time than we ever have done before."

Paul did make the resolve, and earnestly and prayerfully tried to keep it. He was a better and happier being to the end of his life for his adventure on New Year's Eve.

JOE'S LETTER

A New Year's Story

BY A.L.O.E.

Author of "The Claremont Tales,"

"The White Bear's Den," &c.

MARSHALL BROTHERS, LTD.

LONDON, EDINBURGH.

BY A.L.O.E.

"No, Granny, I can't see him."

JOE'S LETTER

A New Year's Story.

——————

"GO again, child, and see if the postman ben't coming down the lane! It's past nine, sure he ought to be here!"

This was the third time that old Janet Jones had sent her little Annie out into the snow, on the last day of the year. It was clear that the cottager was expecting the postman to bring her some very important letter indeed.

"No, Granny, I can't see him," said Annie, as for the third time she came back from the road, shaking the flakes from her hair, and stamping the snow from her boots. "Perhaps our old clock is wrong."

"Everything is wrong, I think," muttered Janet Jones, who was employed in taking some filberts out of a basket, to put in glasses to sell in her window. "Half these nuts are bad, and only fit for the fire!" And into the fire she flung some that were indeed but empty husks.

"Yes," went on the old woman, knitting her brows into very deep furrows, "the old year ends badly enough with me. The pig dead, the potatoes bad, the weather sharp, and the pocket empty. These be very hard times!"

"But Joe, dear Joe, is sure to send you money, Granny," said Annie, who stood leaning against the wall. She did not sit down, for she expected soon to be sent a fourth time to look for the postman.

"Joseph ought to," replied Janet, as sharply as if the child had said that her brother would send not a penny. "He, a great tall fellow, earning good wages, fifteen pounds a year, and everything found, feeding on the fat of the land, and dressed as smart as a goldfinch! It will be hard if he can't spare something for his poor old Granny in her need."

"Joe will—I know that he will. He loves you so much," cried Annie.

"We'll soon see how much," said old Janet, "words without deeds are like husks without seeds." And angrily she threw another rotten nut into the fire.

Annie, to take off her grandmother's mind from her troubles, began to tell her what she had seen the day before at the Hall, when sent up with some work done for the ladies.

"Oh! Granny, I wish you'd been with me yesterday, and seen the Christmas presents which Mrs. Poler has given her nieces! There was a doll, dressed just like a lady, and the prettiest little set of tea-things."

"What do I care about hearing of such trash," cried old Janet. "Mrs. Poler had better spend her money on buying tea for them as wants it, than on giving children tea-cups no bigger than filberts."

Annie was afraid to remind her Granny how kind Mrs. Poler had been in filling her own little apron with apples to carry home to old Janet, or to mention the hundredweight of coals which the lady had sent before Christmas. Annie only remarked, "I suppose that Mrs. Poler gives toys to her nieces because she loves them so much."

"Giving toys when one has lots of money to buy them with is no great proof of love," cried the old woman. "When these little ladies had the smallpox, Mrs. Poler never so much as went near them, for fear of catching it."

"Perhaps Mrs. Poler knew that she could not nurse them; not every one can nurse as you do, Granny," said the child. "What care you took of Joe when he had that bad fall down an area, and broke his poor leg, the very first month that he went into service in London."

"Ah! Poor fellow, he slipped on the steps one cold, frosty day; and his master sent him all the way here to be nursed, for he knew that no one would look after him like his old Granny. Didn't I sit up three nights with my boy when the pain made the fever run high; and didn't I tear up my own handkerchiefs into bandages for his leg, and half starve myself to scrape up money to pay the doctor?"

"Joe will never forget all you did," said Annie.

"I hope that he'll give a proof now that he does not," began Janet, when she caught a sight through the window of some one coming up to the door. "Here's the postman at last!" she exclaimed, starting up from her seat in such a hurry that she knocked over her basket, and sent a good many of her nuts flying in every direction over her cottage floor.

Annie flew to the door, the postman had no need to knock. "Here's the letter—the letter from Joe!" cried the little girl, joyfully, as she returned with the note. "I was sure, quite sure, that he would write soon!"

"I hope that he has done something more than merely write," said Janet, looking very anxious, with mingled hope and fear in her face as she broke open her grandson's letter. When she had taken out the written sheet, instead of reading it, she shook it to see if any money-order would drop out, then looked into the empty envelope, and muttered in a tone of great disappointment, "I made sure of one pound at least! Did I not write to him that the rent must be paid to-morrow, or that we should both be turned out of doors."

"Won't you read Joe's letter, dear Granny?" asked Annie; she was very anxious to hear it.

"You read it to me, child, my eyes are getting dim with old age," said the old woman, giving her the note.

Annie glanced up at her Granny, and saw that the dimness came from something besides age, for the eyes of Janet were brimful of tears which were ready to flow over.

Annie read out as follows:—

"Dear Granny, I am very sorry indeed that the pig is dead, and you in

such trouble, but I hope that things will be brighter soon. I have

hardly a minute for writing, but will soon let you hear again. I wish

you and Annie a happy New Year, and send lots of love to you both; from

your loving grandson, Joseph."

"Is that all?" asked Janet almost fiercely.

"I have not missed a word," replied Annie. She spoke sadly for she was as much disappointed as her Granny could be, though she was not, like her, angry besides.

"Then you may just fling that letter into the fire after the rotten nuts!" exclaimed Janet, trembling with vexation. "After all I wrote to him about the potatoes and the rent, to think of his not sending so much as a sixpence to his Granny, who nursed him when sick, and fed him and cared for him—ungrateful, selfish fellow that he is!"

"Oh! Granny," interrupted the poor little sister, who could not bear to hear such hard words spoken of Joe.

"He 'is' selfish," repeated old Janet. "Did he not buy himself a silver watch last summer, I guess that cost him a pretty bit of money, enough to clear off my debt for rent—and more. Think of his buying himself a watch, and leaving his Granny and his sister to be turned out of doors for want of a couple of pounds! 'Lots of love' he sends us, does he! I'd not give a crooked pin for such love! I like proofs, real proofs of love. I've given him many many such, though now he forgets them all!" Poor Janet put her thin hands before her face to hide the big drops that were now running fast down her wrinkled cheeks.

"Granny, do let us 'trust' Joe," said Annie softly. "Perhaps he could not send any money, he may have spent all before he heard of your trouble."

"He might have written so then," said Janet, drying her eyes. "No, no, in the fine big house in London he forgets all about the poor little cottage which was his home for many a day. While he feasts like a lord with meat twice a day, what does it matter to him if we have not so much as a bit of bacon even on Sundays? He might have thought of 'you,' Annie, my poor child, if my trouble was nothing to him."

"I am 'sure' that Joe loves me," said Annie firmly, her cheeks flushing red at the thought that any one should doubt it.

For Annie remembered the old times before Joe had first gone into service. He had been the kindest of brothers to his little sister, who was many years younger than he. Many a ride had Annie had on Joe's knee, or upon his shoulder. Many a sugar-plum or cake the generous boy had given to his sister instead of eating it himself. What pains Joe had taken to make for Annie a beautiful boat as a parting present! Annie had thought it then the prettiest boat in the world, and after six years she thought so still. There was the boat now on its shelf, always kept nicely dusted by Annie, and almost as good as new, reminding her every day of Joe.

Oh! Young brothers, if you only knew how much power you have by words and deeds of kindness to make your little sisters happy, and win their lifelong love, you would not so often give pain to them when you might so easily give pleasure! Annie had never had from Joe one rough word, far less one thoughtless blow. He would far rather have hurt himself than have hurt his little sister. Annie looked up now at the boat, her brother's keepsake, and could not and would not doubt his love. She was quite able to trust him, and her greatest pain was to see that her grandmother did not.

Perhaps my reader is inclined to think that Janet was a cross, ill-tempered old woman, proud of what she had done for others, and expecting others to do a great deal for her in return. And yet Janet was an honest and kind-hearted woman, one who loved her Bible, and never passed a Sunday without going to church. Janet feared God, and tried to obey His commandments, but she had not yet learned to trust His love. Janet let the wicked thought lurk in her heart that if the Lord really cared for her, He would not leave her to be so poor. And if old Janet thus dared to doubt the love of her heavenly Father, who can wonder if she doubted the love of earthly friends! This want of trust made every trial that came to her doubly heavy to Janet; this made her temper cross, and filled her with bitter thoughts.

There are many who sin like Janet, without half the excuse which she had for her discontented spirit. Janet had had very great trials to bear. Once she had been well-off; she had lived with her good husband in a pretty thatched cottage, and had been as happy and contented a woman as any in the village. But in one year, poor Janet had lost both her husband and her married daughter,—and with an almost broken heart had received her two grandchildren into her home. Even that home was not to be left to her long.

One day as the widow was returning from a distant field in which she had been helping to reap, she saw thick volumes of smoke rising from the direction of her cottage above the trees which hid it from view. With a feeling of fear she rushed forwards, and terrible was the sight which was soon before her eyes. Her pretty cottage was in flames, the thatch was burning fiercely, and though an engine had come from the town, and firemen and neighbours were doing their best to put out the fire, they could not succeed, and what was once a comfortable home was soon but a heap of ashes. Janet Jones was then, not only a widow, but a very poor widow, and hard work she had had to bring up the two orphan children left to her charge. These were no small troubles, and others, in Janet's place, might have been sorely tempted to murmur.

"I wish that 'I' could give poor Granny some proof of love," thought little Annie. "But I have nothing to give, not one penny! To-morrow is New Year's day, and it will be such a sad day to her. Is there nothing that I could do to please her?"

Now when we think hard to discover some way of pleasing a friend, we are pretty sure to find one.

"I remember," said Annie to herself, "that there was a hymn which took Granny's fancy in a book which Mrs. Brown lent us to read last summer. Granny wished that I could write well enough to copy it out fair on the flyleaf of her large Bible. I can write now much better than I could then. I have no New Year's present to give, but I might copy out that hymn; I am sure that Mrs. Brown would lend me the book again if I asked her. But this is such a little, such a 'very' little thing to do for my Granny. Ah! I would do much more if I earned wages like Joe!"

Copying out a hymn was a very little thing, but it was a "proof of love," and a proof that cost Annie some self-denial. She did not like writing at all, and she knew that it would take her hours to copy out six verses quite neatly, taking care not to make one blot. She resolved however to do so, and ran out again into the snow, and went over to Mrs. Brown's to ask her to lend her the book.

Mrs. Brown had a large cheerful home, and four merry little children full of play.

"Oh! Annie, we're so glad you've come!" cried the eldest, clapping her hands as Annie entered.

"I hope you'll stop all day with us," said kind Mrs. Brown, who knew that the girl had a very dull home.

"Oh! Yes,—stop, stop!" cried Charlie Brown. "We're to have roast beef and roley-poley, 'cause it's the last day in the year."

"And grandfather's coming, and he tells us such famous stories,—we'll have games, and all sorts of fun!" exclaimed little Bess.

Annie longed to stop to share the food and the fun. She hesitated, but only for a moment. She had real love for her Granny, and gave a proof of it at once.

"No, thank you so much," she said, "but I cannot leave poor Granny to spend the last day of the year by herself."

Annie soon returned to her cottage with the book containing the hymn. She got down the little bottle of ink, and a pen, and began her copying work, while old Janet sat gloomy and sad by the fire, never speaking a word except to abuse ungrateful Joe.

It was well that Annie had to give much attention to what she was doing, so that she scarcely heard what her Granny was muttering to herself. The verses are so beautiful that they took up Annie's thoughts as she wrote. They are so suitable for the New Year that I will copy them out for my readers, as Annie did for her Granny. I wish that each would learn by heart the loving questions which the Saviour, in this hymn, asks alike of the old and the young:

"I gave My life for thee,

My precious blood I shed,

That thou mightest ransomed be,

And quickened from the dead.

I give My life for thee,

WHAT HAST THOU GIVEN FOR ME?

"I spent long years for thee,

In weariness and woe,

That one eternity

Of joy thou mightest know.

I spent long years for thee,

Hast thou spent ONE for Me?

"My Father's house of light,

My rainbow-circled throne,

I left for earthly night,

For wand'rings sad and lone.

I left it all for thee,

Hast thou left AUGHT for Me?

"I suffered much for thee,

More than thy tongue can tell,

Of bitterest agony,

To rescue thee from Hell.

I suffered much for thee,

WHAT DOST THOU BEAR FOR ME?

"And I have brought to thee,

Down from My home above,

Salvation full and free,

My pardon, and My love.

Great gifts I brought to thee,

WHAT HAST THOU BROUGHT TO ME?

"Oh! let thy life be given,

Thy years for Me be spent

World fetters all be riven,

And joy with suffering blent,

I gave MYSELF for thee,

Give thou THYSELF to Me?"

NEW YEAR'S morning dawned bright and clear; the pure snow gleamed like diamonds in the rays of the glorious sun, but old Janet rose with a heavy heart and a gloomy brow. She thought of the landlord calling for the rent; she thought of her neighbours in their merry homes, and of her grandson living in comfort in London; she thought of everyone being happy but herself. If Janet thought also of God, I fear that it was with little faith, little trust. She was so gloomy and sad that she did not even smile at poor Annie when they first met, or wish her a happy New Year.

Annie watched her Granny as she went up to the table on which lay her large Bible open at the place where the child, as neatly as she could, had copied out the hymn. Annie saw her Granny take out her spectacles, slowly wipe them, put them on, and then sit down to read, as she always read while the water was boiling for breakfast.

"I hope that Granny will be pleased," thought Annie. "I hope that she will like the hymn now as she did in the summer, and know that I copied it out as a little proof of my love. But dear me! What is the matter! Granny is crying—crying over the hymn!"

For as the old woman read the Saviour's questions to her own heart, first her lip trembled, then her eyes dimmed with tears, and she had to take off her spectacles and wipe them before she could read any farther. At last, when she had reached the sixth verse, the poor old woman murmured to herself, "ungrateful sinner that I am!" and fairly burst into tears.

"Oh! Granny, I never meant to write out anything to vex you, I never thought that hymn would make you cry!" exclaimed Annie, quite in distress.

"Is it not enough to make me cry to think that my Lord has done all this for me, sinner that I am," sobbed old Janet, speaking not to Annie, but to herself, "to think that He should have given Himself for 'me,' suffered for 'me,' died for 'me,' and that all the return which I made is to doubt Him now! What proof of love could the dear Lord have given more than He gave! He kept back nothing, not even His life! And I—I have been finding fault with a poor lad for forgetting the little kindness which I have shown, the little trouble which I have taken, while all the while I was ungrateful to the Lord, who has done for me a thousand—thousand times more than ever woman did for a child!"

The words of the beautiful verses had indeed gone straight to the heart of Janet, and awoke in it sorrow and repentance, but other feelings besides. Janet felt love, grateful love to Him who had first loved her; and with love came peace, and hope, and trust, for He who had done so much for her soul would, as she now felt sure, never, never forsake her.

Annie scarcely knew whether to be glad or sorry that she had written out the hymn. But she had soon something else to take up her attention.

"Why, Granny, here's the postman coming again," cried out the child in surprise; for to have letters two days running was a thing which had never happened before to old Janet.

Annie ran to the door to take in the letter, and returned with a face beaming with joy. "It's Joe's hand—he has written again," she cried, as she gave the note to her Granny.

Janet had her spectacles on, and she opened the letter herself, but as she did so, a little paper dropped fluttering to the floor. Annie picked it up, and almost screamed with delight as she saw "three pounds" written on a post-office order.

Janet clasped her wrinkled hands and softly exclaimed, "Thank God!" then with a trembling voice read aloud the following letter.

"Dear Granny, I had not enough money yesterday to get you clear out of

trouble, and did not like to do more than let you know that I had got

your note, till I should find how much my watch would sell for. I am

pleased now to send £3; it is more than you will need for the rent, but

I want you to have a real good dinner on New Year's day,—and please,

with the rest of the money, buy a nice warm cloak for Annie, from me."

Annie kissed her brother's letter again and again; her heart was full of love and joy.

"I hope that it's not wrong," she said, smiling as she examined the post-office order, "but I can't help wishing that I could give such a 'proof of love' as Joe has done."

"Your little hymn has done as much—more for me than this money-order," said old Janet, with a trembling hand taking the paper from the child. "This order shows me that I did wrong to doubt the love of my boy, but the hymn has shown me how faithless and sinful it was in me ever, for one moment, to doubt the love of my Saviour!"