Title: The Russian road to China

Author: Jr. Lindon Bates

Release date: October 19, 2025 [eBook #77082]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1910

Credits: Alan, deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

A MAID OF OLD MUSCOVY

(From a painting by Venuga)

THE RUSSIAN ROAD

TO CHINA

BY

LINDON BATES, Jr.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1910

COPYRIGHT, 1910, BY LINDON BATES, JR.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published May 1910

CONTENTS

| I. | The Path of the Cossack | 1 |

| II. | The Great Siberian Railway | 25 |

| III. | In Irkutsk | 71 |

| IV. | Sledging through Transbaikalia | 114 |

| V. | In Tatar Tents | 173 |

| VI. | The City of the Reborn God | 220 |

| VII. | Russia in Evolution | 273 |

| VIII. | The Story of the Hordes | 322 |

| IX. | China | 364 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

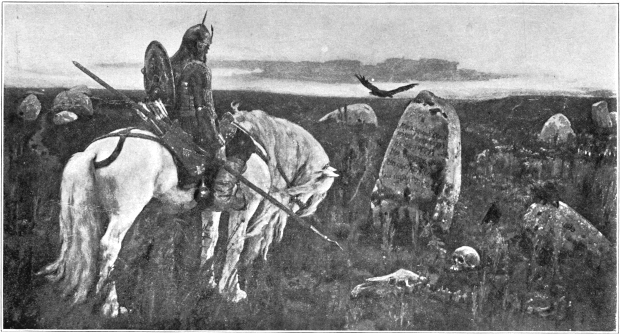

| A Maid of Old Muscovy From a painting by Venuga |

Frontispiece |

| Yermak’s Expedition to Sibir, attacked by the Tatars From a painting by Surikova |

8 |

| Church of St. Basil, Moscow Ivan the Terrible blinded its architect that he might never duplicate the masterpiece |

20 |

| Bridge over the Irtish | 38 |

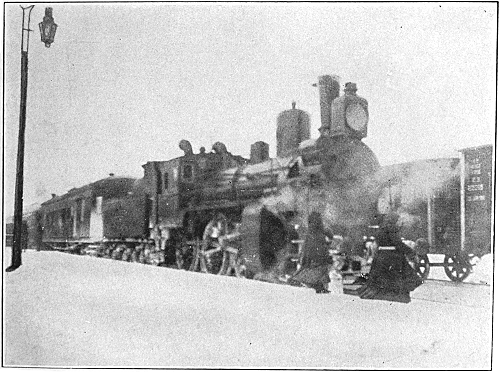

| Along the Trans-Siberian Railway | 38 |

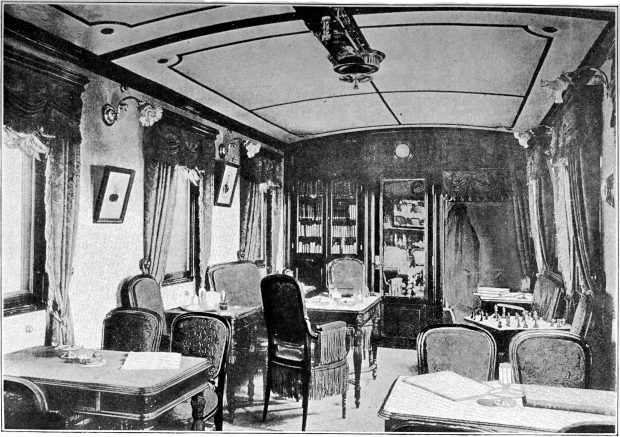

| Dining-Car Saloon—View of the Library | 46 |

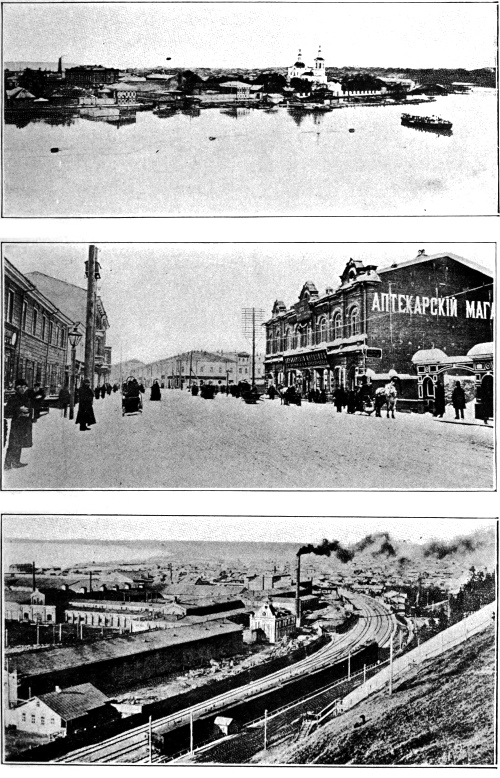

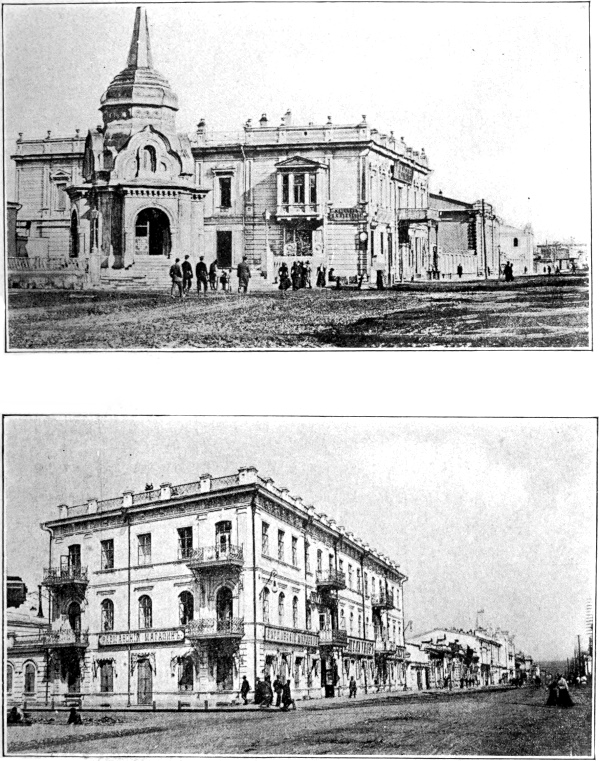

| Cities of New Russia—Tiumen, Tomsk, Perm | 50 |

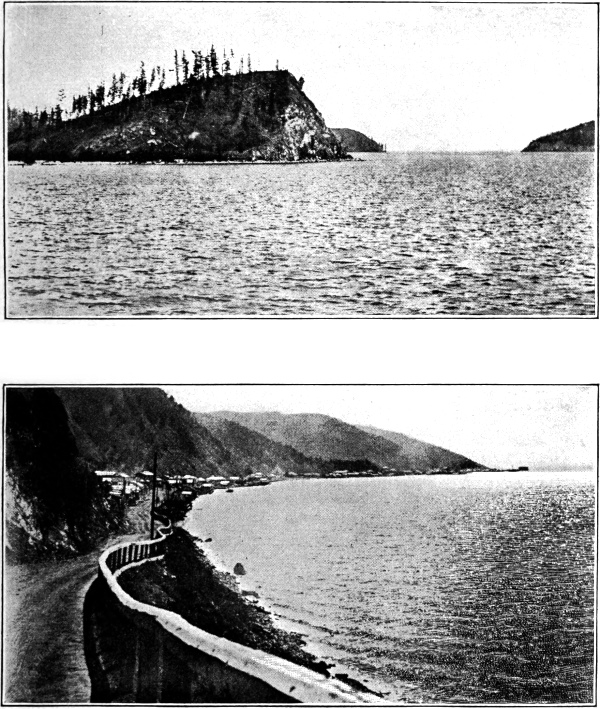

| Island of Kaltigei, Lake Baikal | 68 |

| Village of Listvianitchnoe, Lake Baikal | 68 |

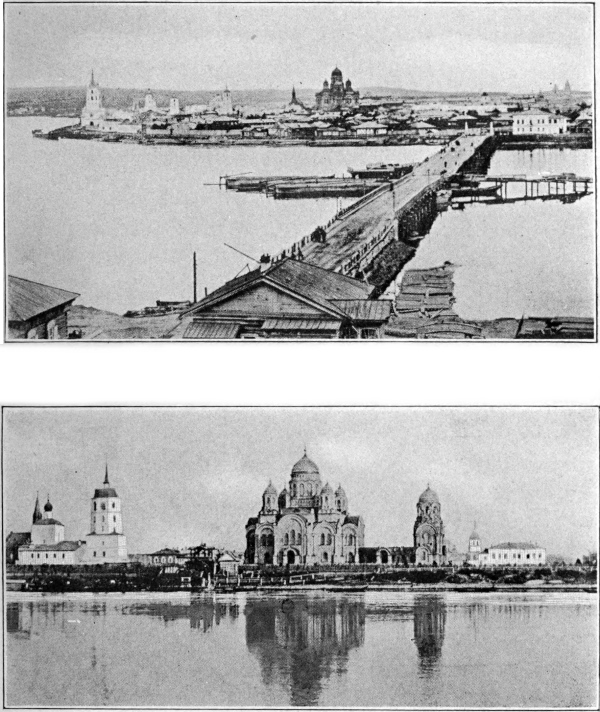

| The Angara River, Irkutsk | 76 |

| The Cathedral, Irkutsk | 76 |

| A Chapel in Irkutsk | 86 |

| Bolshoiskaia, Irkutsk | 86 |

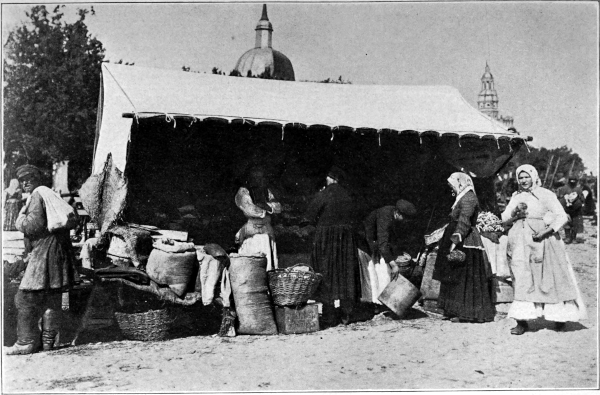

| The Bazaar, Irkutsk | 90 |

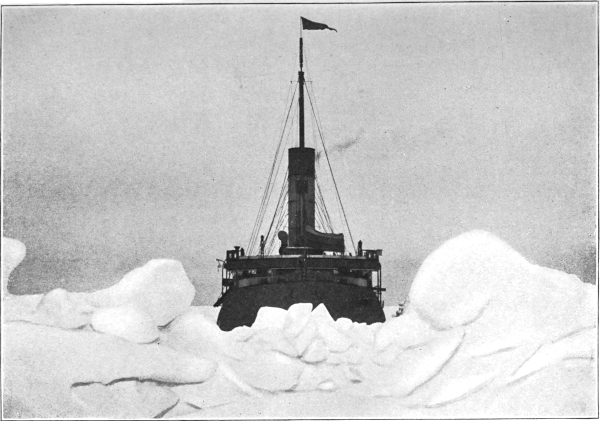

| The Ice-Breaker, Yermak—Lake Baikal | 98 |

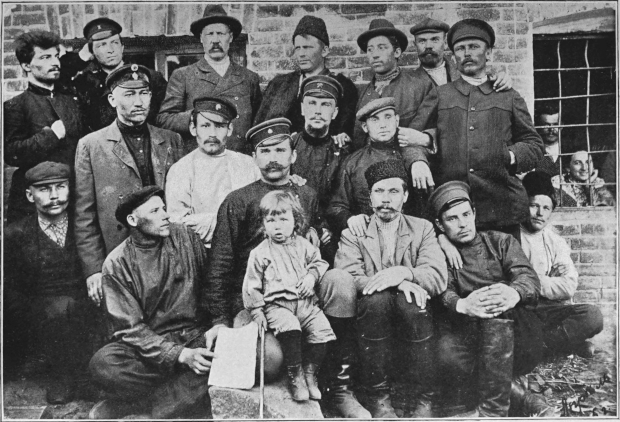

| The Organizers of the Chita Republic | 108 |

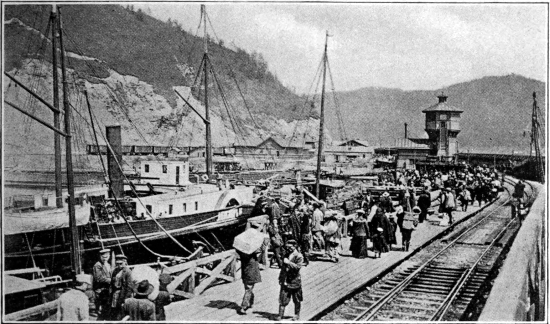

| Baikal Station | 116 |

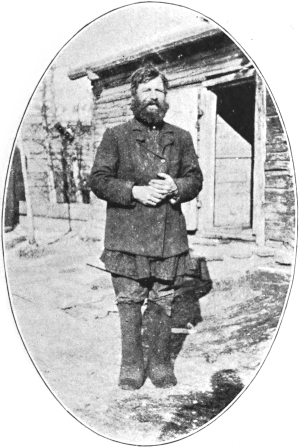

| The Highlands of Transbaikalia | 116 |

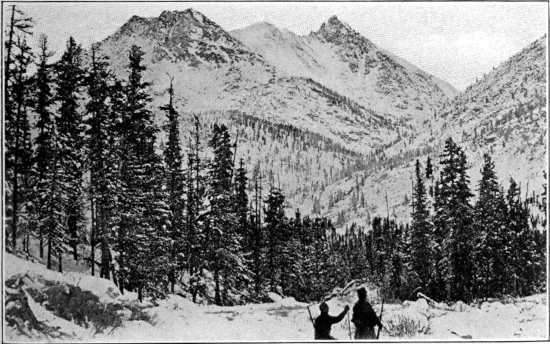

| Sledging Southwards | 126 |

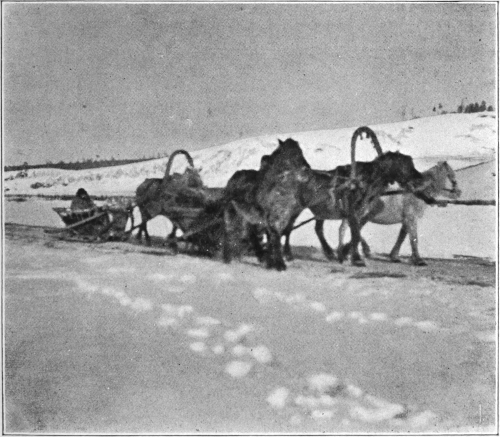

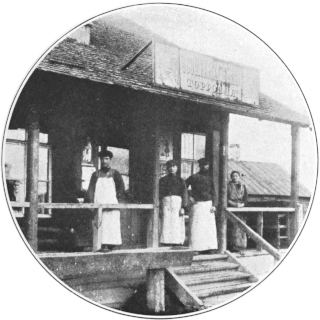

| Siberian Types—Peasant, Village Storekeeper | 136 |

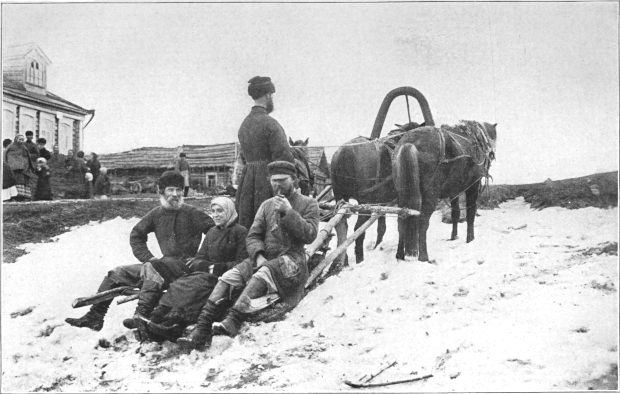

| Peasant Types | 150 |

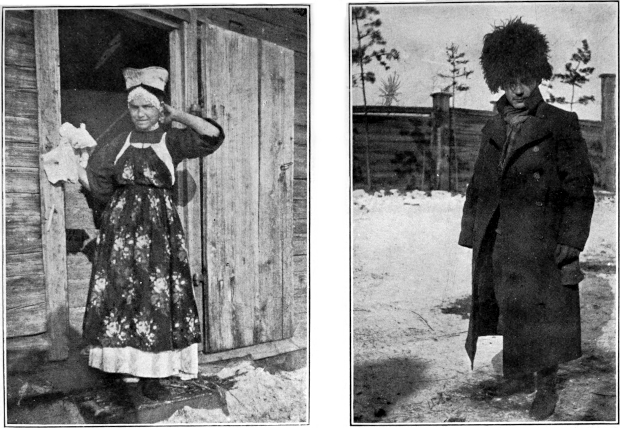

| A Chickoya Girl | 164 |

| A Troitzkosavsk Student | 164 |

| A Wayside Temple | 178 |

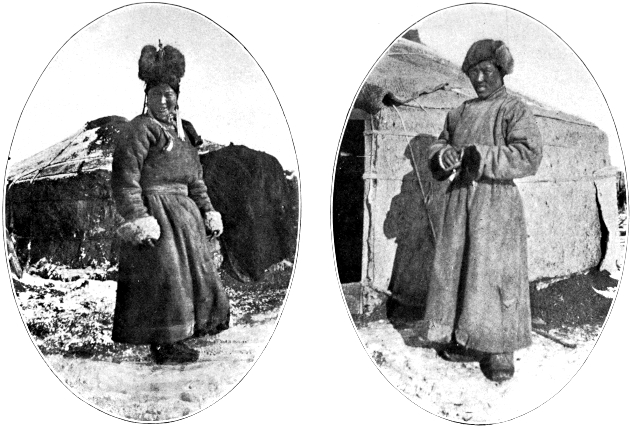

| A Mongol Belle and her Yurta | 186 |

| A Zabaikalskaia Buriat | 186 |

| A Mongol “Black Man” | 206 |

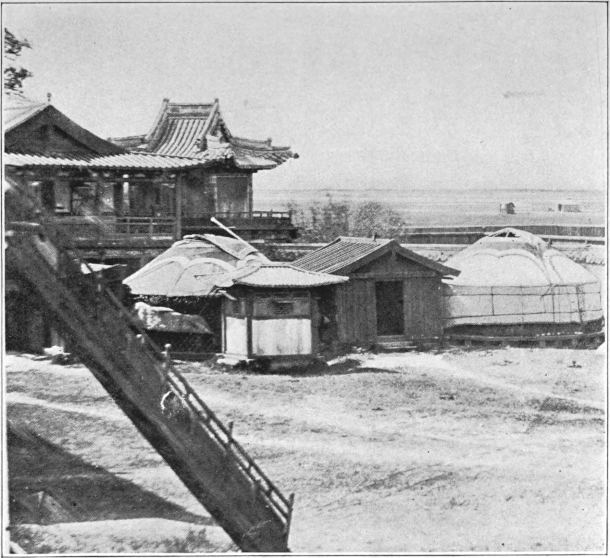

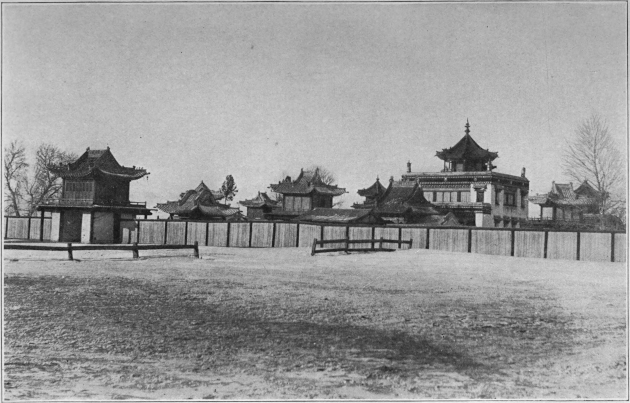

| Temple of Gigin, Urga | 222 |

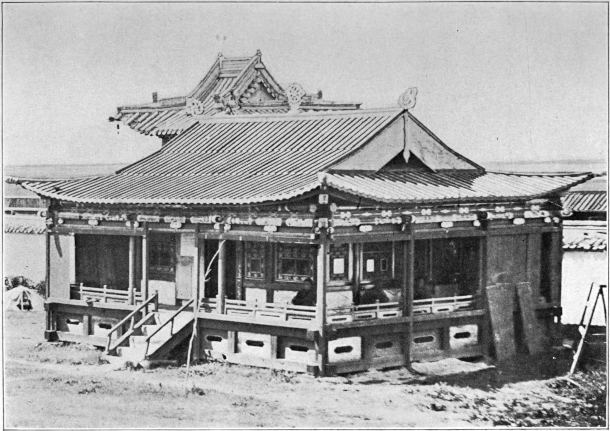

| Temple in the Urga Lamasery | 228 |

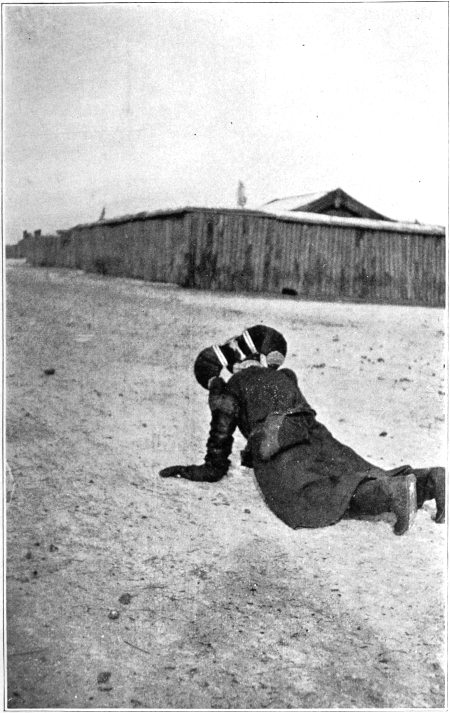

| A Prostrating Pilgrimage | 234 |

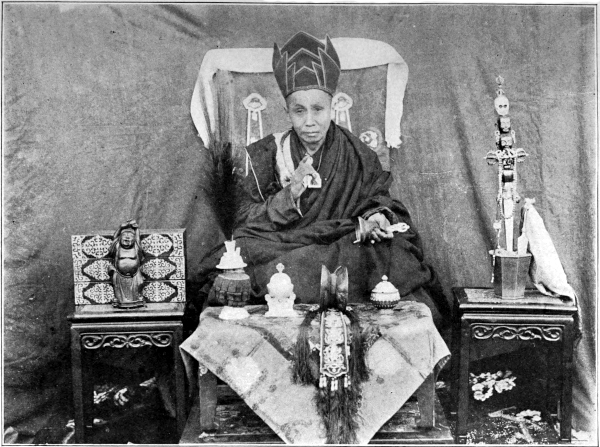

| A Grand Lama | 244 |

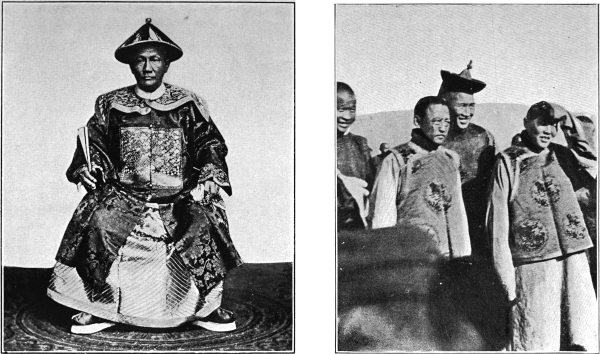

| Chinese Mandarin | 256 |

| Gigin, the Living Buddha | 256 |

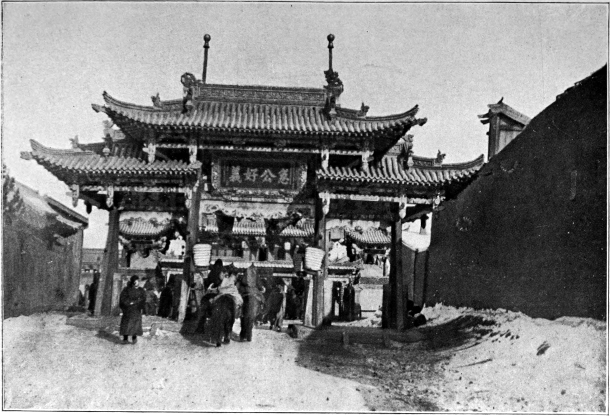

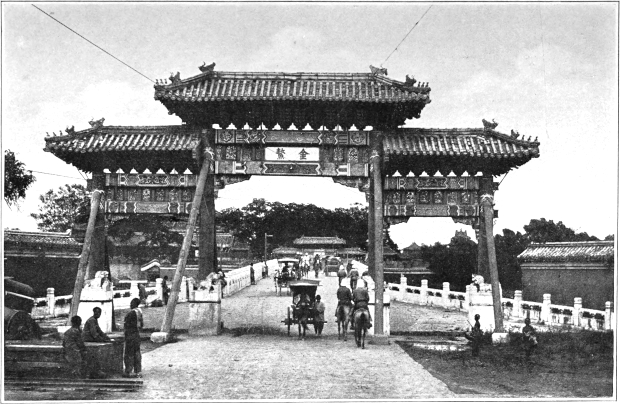

| Chinese Archway, Urga Maimachen | 262 |

| The Great Wall | 270 |

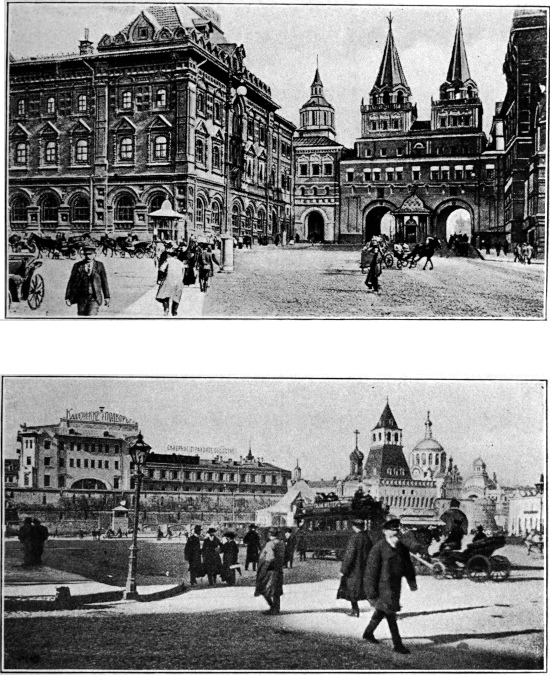

| The Kremlin, Moscow | 282 |

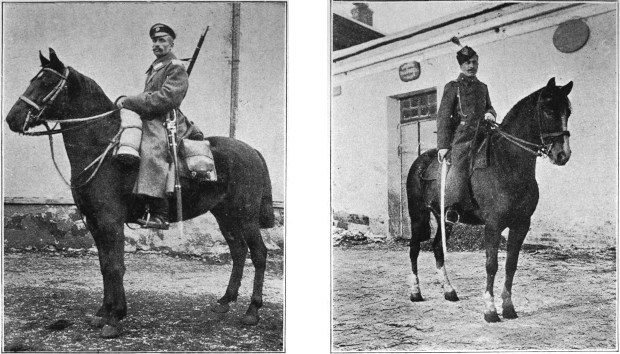

| Russian Types—Dragoon, Constable | 292 |

| Street Scenes in Moscow (The Tverskaia Gate, Loubianskaia Place) |

302 |

| Russian Types—Peddler, Policeman | 316 |

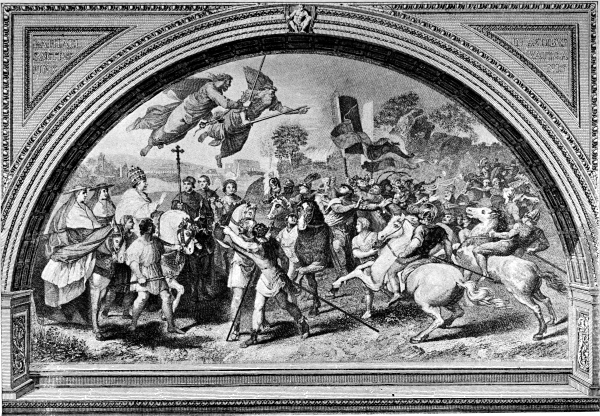

| The Miracle of Attila’s Repulse (From the painting by Raphael in the Vatican) |

332 |

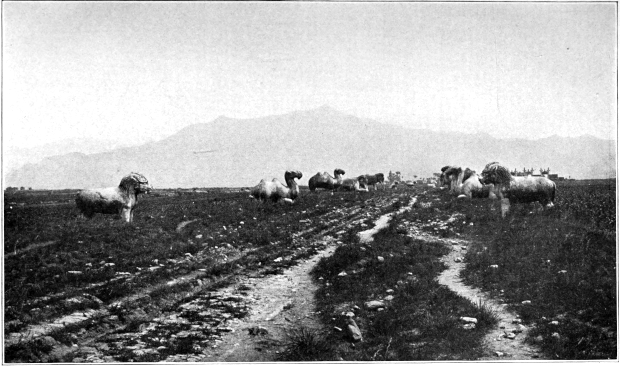

| On the Road to the Ming Tombs | 342 |

| The Glory is departed | 360 |

| The Bridge and Tablets in Pei-hai | 368 |

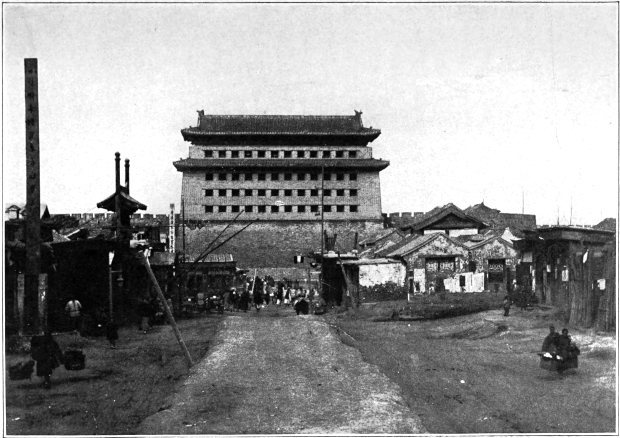

| Hsuen-wu Gate, Peking | 374 |

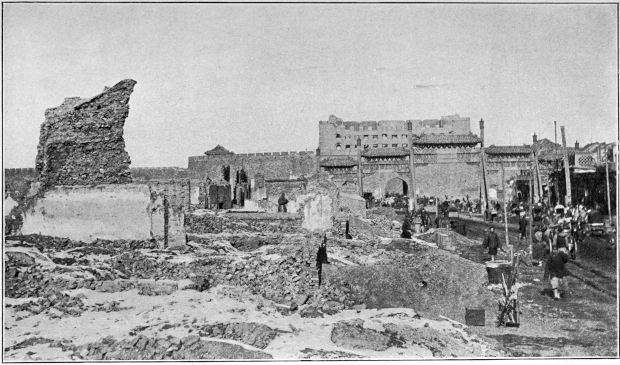

| Peking, where the Allies’ Main Assault was made | 380 |

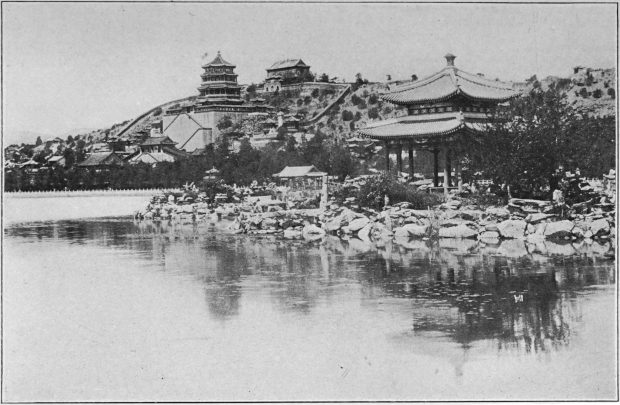

| Summer Palace of the Emperor | 388 |

| Map of Asia, showing Route from Moscow to Peking | 392 |

[Pg 1]

THE RUSSIAN ROAD TO

CHINA

THE PATH OF THE COSSACK

AN ancient way leads across northern Asia to the Chinese borderland. The steel of the great Siberian Railroad harnesses now the stretch which mounts the Urals, pierces the steppes, winds through the Altai foothills, and by cyclopean cuts and tunnels girdles Lake Baikal. From Verhneudinsk southward, it has remained as an ancient post-road leading through the Trans-Baikal highlands to the frontier garrison town of Kiahta. Over the Mongolian border at Maimachen, it has narrowed into a camel-trail threading the barren hills to the encampment of the Tatar hordes at holy Urga. Thence it strikes across the sandy wastes of Gobi, and passes the ramparts of the Great Wall of China, on its way toward Peking and the Pacific.

Through five centuries this road has been building. Cossacks blazed its way; musketoon-armed Strelitz, adventuring traders, convicts condemned for sins or sincerity, land-seeking peasants, exiled dissenters, voyaging officials—all have trampled it.[Pg 2] Hiving workmen under far-brought engineers have pushed the rails onward, bridging the chasms and heaping the defiles. Following it eastward, unpeopled wastes have been sown to homesteads, hamlets have grown into cities. To the very gateway of China it has led the Muscovite. It is the path of Slavic advance.

The way scarcely passed Novgorod in the early sixteenth century when the great family of the Stroganovs, a “kindred in Moscovie called the sonnes of Anika living neare the Castle of Saint Michael the Archangel,” began the fur-trade with the Samoied tribesmen from Siberia, who paddled down the Wichida River to barter peltries with the Russians. The prudent merchant Anika, looking to a more permanent source for those valued furs than the irregular visits of the aborigines, planned to anticipate his brother traders in their purchases. He sent east with a band of returning Samoieds some of his own henchmen carrying, for traffic with the inhabitants, “divers base merchandise, as small bels, and other like Dutch small wares.” The agents returned to report what impressed them most. There were no cities. The Samoieds were “lothsome in feeding,”—even a Russian frontiersman might shrink from the cud of a reindeer’s stomach as food,—and knew neither corn nor bread. They were cunning archers, whose arrows were headed with sharpened stones and fishbones. They were clad in skins, wearing in summer the[Pg 3] furry side outward and in winter inward. They willingly gave sable-skins for Dutch bells.

A series of trading expeditions began, which made the Stroganovs so enormously wealthy that “the kindred of Anika knew no ends of their goods.” Indeed, they gained so much by this exploitation that they began to fear the application by the Czar’s agent of a monetary test of patriotism. So, by a stroke of finance not unknown in modern days, there was arranged the Russian equivalent for carrying five thousand shares of Metropolitan. A block of small wares for the account of the Czar’s brother-in-law, Boris, was added to the stock in an especially important expedition among the Samoieds and Ostiaks. The adventurers got far inland. They saw men riding on elks, and sledges drawn by dogs. They returned with wonderful tales of marksmanship, and, more important, brought back enough furs to give Boris a dividend, in gratitude for which he secured to the Stroganovs the grant of an enormous tract of land along the Kama River and a monopoly of the trade with the aborigines.

The Stroganovs grew and thrived. They scattered trading-posts and factories along the river-highways and sent many parties into the interior to barter. In the half-century following old Anika’s expedition, they had carried the Slavic way to the Urals.

In the summer of 1578, when Maxim Stroganov was ruling over the family estates along the Kama,[Pg 4] one Yermak, heading a fugitive band of Cossacks, tattered and spent, with dented armor and drooping ponies, straggled into camp and offered service. With great delicacy Maxim forbore pressing too closely his inquiry into their antecedents. It might have wounded Yermak’s susceptibilities to avow that his chief lieutenant, Ivan Koltso, was under sentence of death for capturing and sacking a town of the Nogoy, and that the immediate cause of his advent was an army of Imperial Strelitz, which had driven his band from the Volga District for piracy and highway robbery.

The situation on the far side of the Urals, where the skin-hunting tribes had been conquered by a roving horde of Tatars under Kutchum Khan, was at this time interfering sadly with the Stroganovs’ fur business. Eight hundred Cossacks, furthermore, of shady character and urgent needs were undesirable neighbors. So the prudent Maxim, not particularly solicitous as to which of the two might be eliminated, offered Yermak a supply of new muskets if he would go away and fight the Tatars. They were not pleasant people for the Cossacks to meet, these former masters of Moscow. But behind were the soldiers of Ivan the Terrible. With a possible conquest before, and the Strelitz behind, Yermak gladly chose to invade the Tatar territory, which is now western Siberia.

Up the Chusovaya River the little expedition started in 1579, damming the stream with sails to[Pg 5] get the boats across its shallows. Penetrating far into the mountains, the band reached a point where a portage could be made across the Ural water-shed. Then they headed down the Tura River into Siberia. Here the invaders met the first army of the Tatars under Prince Yepancha, and with small loss drove them back. Yermak made his winter camp on the site of the present city of Tiumen.

Next year the advance began once more. The Khan of the Tatars, Kutchum, was alive to the seriousness of the incursion, and prepared to ambush the Cossack flotilla as it descended the Tura. At a chosen spot chains were stretched across the stream, and bowmen were stationed on the banks to await the coming of Yermak and overwhelm with arrows his impeded forces. The Tatar sentries above the ambuscade signaled the coming of the boats; all eyes were turned intently upstream. Then Yermak’s soldiers fell upon them from the rear, to their total surprise and his complete victory. Straw-stuffed figures in Cossack garments had come down in the boats; the men themselves had made a land-circuit and had struck the enemy unprepared.

In defense of his threatened capital, Sibir, the old Khan rallied once more. He assembled a great army, thirty times that of the Cossacks. For the invaders, however, retreat was more perilous than advance. Yermak went on, and in a great fight on the banks of the Irtish, again prevailed. With his forces reduced by battle and disease to some three[Pg 6] hundred effectives, he entered Sibir on October 25, 1581. A few days later the Ostiak tribes, glad to escape their Koran-coercing masters, proffered their allegiance, and the Cossack saddle was on Siberia.

But how precarious was their seat! Southward were the myriads of the unconquered hordes of Tatary; only one of the score of their khans had been vanquished. As thistledown is blown before the wind, so could Yermak’s oft-decimated band have been swept away had once the march of the Mongols’ main division turned northward. Girding him round were the self-submitting Ostiaks, loyal for the moment to those who had won them freedom from the old proselyting overlord, but not long to be relied upon once the weight of Cossack tribute—the fur-yassak—began to be felt.

But what the Tatar hordes had not, what the Ostiak hunters had not, the three hundred Cossacks had—a man. This man, starting his march as the hunted captain of a band of outlaws, could conquer half a continent. Then over the heads of his employers, the mighty family of Stroganov, over the heads of governors of provinces, of boyars, of ministers to the throne, he could send by his outlaw lieutenant, Ivan Koltso, loftily, imperially, as a prince to a king, his offer of the realm of Siberia to Ivan Vasilevich.

Ivan the Terrible, Czar of all the Russias, he who had blinded the architect of St. Basil, lest he plan a second masterpiece; he who had tortured and slain[Pg 7] a son, hated less for his intrigues than for his unroyal weakness, responded imperially. Over the long versts Ivan’s courier carried to Yermak a pardon, confirmation as ruler of the newly-won realm and the Czar’s own mantle, an honor accorded only to the greatest, the boyars of Muscovy. Following the messenger eastward there plodded three hundred musket-armed Strelitz to bear aid to the Cossack garrison. Sorely now were these reinforcements needed, for the Ostiak tribes flamed into rebellion against King Stork. With Kutchum’s Tatars, they returned to the attack and besieged Sibir. Once again, though hemmed about by the multitude of his enemies, the valor of Yermak saved his cause. In a totally unexpected sally, in June, 1584, the Tatar camp was surprised, a great number massacred, and the besiegers scattered.

The whole country, however, save only the city of Sibir, was still in arms. Engagements between small parties were constant. Ivan Koltso, striving to open a way for a trader’s caravan, fell with his fifty, cut down to the last man. Yermak, marching out to avenge him, was himself surprised near the Irtish. With Ulysses-like adroitness, he and two followers escaped the massacre and reached the river-bank, where a small skiff promised safety. Leaping last for the boat, Yermak fell short, and, weighted with his armor, sank in the river that he had given to Russia. The two Cossack soldiers alone floated down to their comrades.

[Pg 8]

One hundred and fifty, all that were left of them, started their long homeward retreat. Far from Sibir, they met a hundred armed men sent by the Czar. Great was the spirit, not unworthy of the dead leader, that turned them back, to march to a site twelve miles from Sibir, where they built their own town, now the city of Tobolsk.

In the years that followed, their nomad enemies drifted south, leaving those behind who cared not for their old khan’s quarrels. The phlegmatic Ostiaks returned to their hunting and to their feasts of uncooked fox-entrails. The long fight had rolled past, leaving the Slavic way undisputed to the Irtish.

Well it was, for no more of the Strelitz marched to the aid of the garrisons. Russia was in the throes of civil war and invasion,—the long-remembered “Smutnoe Vremya,” time of troubles. Boris Godunov, once favorite of Ivan the Terrible, became the real ruler in the reign of the weak Feodor. On the death of this prince, with the heir-apparent Dimitri suspiciously slain, he had mounted the empty throne, and a pretender, claiming to be Dimitri miraculously escaped, had risen up in Poland, gained the support of the king, and marched against Boris. Though the Polish army was routed, Boris succumbed shortly after to a poison-hastened demise.

YERMAK’S EXPEDITION TO SIBIR ATTACKED BY THE TATARS

(From a painting by Surikova)

(click image to enlarge)

Dimitri attacked the new czar, captured Moscow, and was crowned in the Kremlin by the Poles. [Pg 9]A revolution followed within a year, in which the pseudo-Dimitri was slain. Meanwhile the Poles were devastating Russia more cruelly than had the old Tatar conquerors. At length Minim the butcher of Novgorod led a popular revolt, which in 1613 carried to the throne Michael, the first of the Romanovs.

Through all these years, despite the fact that anarchy and chaos rioted over Muscovy, despite the fact that no troops came to aid in the advance, the Cossacks still pressed their way, contested by the scattered bands of Tatars, and farther on by the Buriats, the Yakuts, the Koriats. After these fighters and conquerors came the traders and colonists, with their families, following along the road that had been won. The valleys of the great Siberian rivers, which so short a time before had been the grazing-grounds of the Tatars, became dotted now with the farms of the new-come settlers. The advance guards of the fur-traders, with blockhouses guarding the portages, and clustering wooden huts and churches, pushed south and east as far as Kuznetz, at the head of navigation on the River Tom, and to the foot of the Altai Mountains. North and east the trade-route was advanced to the Yenesei, twenty-two hundred miles inland. As many as sixty-eight hundred sables went back to Russia in 1640, together with great quantities of fox, ermine, and squirrel-skins.

The quaint volumes of “Purchas his Pilgrimes,”[Pg 10] published in 1625, tell of some of the early explorations. A band of Cossacks dared the upper Yenesei, which “hath high mountains to the east, among which are some that cast out fire and brimstone.” They made friends of the cave-dwelling Tunguses in this region, who were themselves stirred to explore, and went on far eastward to another river, less than the Yenesei but as rapid. By faster running the Tunguses caught some of the inhabitants, who pointed across the river and said “Om! Om!” The old chronicler diligently records the speculation as to what “Om! Om!” could mean. Some thought that it signified thunder, others held it a warning that the great beyond teemed with devils. These unfortunate slow-running natives died, “probably of fright,” when the Tunguses, in a spirit as naïvely unfeeling as if they were collecting curios, were taking them back to be exhibited to their friends the Cossacks. How far these Tunguses had pierced cannot be told. In one of the dialects of the Yakuts who live beyond Baikal, “ta-oom” or “tanak-hoom” means “greetings.” Had the Tunguses and the Cossacks who followed them arrived at the Yakuts’ country? Or was the river on which passed “ships with sails” and beyond which was heard the booming of brazen bells the Amur? Were those the junks and temple-gongs of the Manchus? Ni snaia,—who knows?

In 1637 the Cossacks reached and established themselves in Yakutsk. In 1639 by the far northern[Pg 11] route they pierced to the Sea of Okhotsk. In 1644 a party reached the delta of the Kalyma, and curiously speculated upon the mammoth tusks which they found. In 1648, on the Cellinga River beyond Lake Baikal they built Fort Verhneudinsk. Had their tide of conquest now rolled southward, up the Cellinga Valley, the Russian Eagles might to-day be flying over Peking. Only the Kentai Mountains were between them and prostrate Mongolia, enfeebled by the internecine warfare of her rival khans. From Mongolia, the road, worn by so many conquerors of old, leads fair and clear to the Chi-li Province and the heart of China.

But they passed this gateway by, those old Cossack heroes, as the railway builders have passed it by, to press with Poyarkov to the Pacific; to conquer, with Khabarov, the Amur; to meet in desperate conflict the whale-skin cuirassed Koriats of the coast; to battle with the Manchu in conflicts where “by the Grace of God and the Imperial good fortune, and our efforts, many of those dogs were slain”; to fight until but an unvanquished sixty-eight were left of the garrison of eight hundred in beleaguered Albazin.

The current of conquest passed by this door to China, but the swelling stream of commerce searched it out. In 1638, the Boyar Pochabov, crossing Baikal on the ice, broke the first way to Urga, the capital of the Mongolian Great Khan, and gained the friendship of the monarch. In the[Pg 12] interests of trade, the deputies of the Czar Alexei Michailovitch followed up the opening with an embassy in 1654 to the Chinese Emperor himself. Over steppe and mountain and desert the mission wound its weary way to Kalgan, the outpost city beside the Chinese Wall, and then on to Peking, bearing to the Bogdo Khan, the Yellow Czar, the presents of Chagan Khan, the White Czar.

From the Forbidden Palace at Peking were started back, four years later, return presents, including ten puds of the first tea that reached Russia. With the presents came a message that drove flame into the bearded cheeks of the Czar and set his Muscovite boyars to grasping their sword-hilts. “In token of our especial good-will we send gifts in return for your tribute.” Thus, the Chinese Emperor.

The answer of the Czar started another legation plodding across a continent, and the retort was thrown at the feet of his Yellow Majesty. It was a summons forthwith to tender his vassalage to Russia. The Czar’s gauntlet had been hurled across Asia. But all it brought was beggary to the traders who had begun to press along the newly-opened route to a commercial conquest of the East.

Soon Russia regretted the fruitage of her challenge. In 1685 Golovin’s embassy left Moscow, and, arriving two years later at Verhneudinsk, opened negotiations with Peking. A Chinese commission then made its way north, and at Nerchinsk, August 27, 1689, was signed the famous treaty[Pg 13] closing to Russia her Amur outlet to the Pacific, purchased with such desperate valor at Albazin, but granting to a limited number of Russian merchants trading privileges into China.

A lively traffic at once sprang up. Long caravans, silk- and tea-laden, crossed the Mongolian deserts, the Siberian steppes and hills, and the forested Urals, taking the road to Europe. A little Russian settlement was founded at Peking, and a traders’ caravansary was built. The church constructed by the prisoners of Albazin, who had been so kindly treated by the Manchus that they at first refused the release which the treaty brought, gave place to a larger edifice erected by popes from Russia.

Soon, however, the Russians again offended the Celestial Emperor. In their riotous living, the quickly enriched merchants disquieted the sober Chinese. The Siberians over the frontier gave asylum to a band of seven hundred Mongol free-booters, whom it was urgently desired to present to a Chinese headsman. So commerce was forbidden anew, and most of the reluctant merchants left their compound. Some stayed and assimilated with the Chinese, retaining, however, their religion; and for years a mixed race observed in Peking the rites of Greek Orthodox Christianity.

It may seem strange that rulers so energetic as Peter the Great and some of his successors took no steps to resent by force of arms the arbitrary acts of the Chinese Emperor. But much was going on in[Pg 14] Russia; Peter was occupied with his invasion of Persia, and Catherine was without taste for a distant and doubtful campaign. The garrisons scattered over the enormous area of Siberia were numerically too weak and too poorly equipped to do more than hold their own. So, when commerce was once more interdicted and the merchants banished, recourse was had to diplomacy. In 1725 the Bogdo Khan relented enough to receive Count Ragusinsky with a special embassy from Catherine the First, which arranged the second great agreement with China, called the Treaty of Kiahta.

By it the frontier cities of Kiahta in Siberia, and Maimachen, facing it just across the line in Mongolia, were established as the gateway to Chinese trade. The treaty provided for the extradition of bandits and for a perpetual peace and friendship between the high contracting parties. Ever since, the citizens of Kiahta have alternately blessed and blamed Ragusinsky,—blamed him because, in the fear lest any stream flowing out of Chinese into Russian territory should be poisoned, he settled the boundary city beside a Siberian brook so inadequate that Kiahtans have suffered ever since for lack of water, with the river Bura only nine versts away in China; blessed him because of the great prosperity the treaty brought to their doors.

The tea carried by this highway became Russia’s national drink. Great warehouses arose, built caravansary-wise around courts. Endless files of[Pg 15] two-wheeled carts rolled northward, bearing each its ten square bales of tea, or its well-packed bolts of silk. The merchants grew wealthy in the rapidly swelling trade.

A great Chinese embassy, headed by the third ranking official of the Peking Foreign Office, made its way to Moscow to keep permanent the relations of the two empires. Similarly, a Russian embassy was established in the rebuilt compound in Peking, where a new church arose, whose archimandrite gained a comfortable revenue by selling ikons and crucifixes to the many Chinese converts he had baptized.

Catherine the Second’s edict opened to all Russians the freedom of Chinese trade. Its volume, large before, became now even greater. In 1780 the registered commerce at Kiahta had risen to 2,868,333 roubles, not to mention the large value of the goods taken in unregistered.

Tea, a pound of which, if of best quality, cost two roubles in those days, silks, porcelains, cottons, and tobacco, went north, exchanged for Russian peltries, for cloth, hardware, and, curiously enough, hunting-dogs.

An English merchant, who had penetrated to Kiahta in that year, gives an amusing account of the mutual distrust with which the barter was conducted. The Russian going over the frontier to Maimachen would examine the goods in the Chinese warehouse, seal up what he desired, and leave two[Pg 16] men on guard. The Chinese merchant would then come to Kiahta, and do the same with the Russian’s wares. When the bargain was struck, both together carried one shipment over the border with guards and brought back the exchange.

In growing prosperity, undisturbed, the Kiahta caravans came and went, while elsewhere history was warm in the making.

Napoleon marched to Moscow, to Leipsic, to Waterloo. The Kiahta caravans came and went. The St. Petersburg Dekabrists rose for Constantine and the Constitution. The Kiahta caravans came and went. The Crimean War saw the Russian flag flutter down at Sevastopol. Even as the Malakoff was stormed, a Russian army marched into Central Asia to seize the Zailust Altai slope, which points as a spear toward Turkestan and India, and a Russian navy sailed under Muraviev to occupy the forbidden Amur. The Kiahta caravans came and went.

At length a railroad, pushed year by year, reached the Pacific. One branch cut across the reluctantly-accorded Manchurian domain to Vladivostok; another struck southward to Dalny and Niu-chwang. The Russian Eagles perched at Port Arthur and nested by the far Pacific.

The camel-commerce of the old overland road across Mongolia shrank now as shrinks a Gobi snow-rivulet under the burning desert sun. The meagre Kiahta caravans became but a gaunt[Pg 17] shadow of the mighty past. Only an intermittent wool-export and a dwindling traffic in tea to the border cities remained of the great tribute of the Urga Road. As trade vanished from their once busy warehouses, the Chinese merchants were troubled. Perhaps to prayer and sacrifice the God of Commerce would relent? So a scarlet temple rose on the hill by Maimachen. Prosperity came suddenly once again, a new trade rolled north over the historic way. The Mongol cart-drivers returned from far Ulasati. The camel-trains, that had scattered south to the trails beyond Shama, gathered back as antelopes herd to a new spring in the desert.

The God of the Red Temple, the God of the Caravan, had sent the Japanese. As the Amban’s executioner strikes off a victim’s hand, so had the Nipponese lopped away the railroad reaching down to Dalny and Niu-chwang—the road that was breaking the camel-trade a thousand versts beyond, on the old route by Maimachen and Kiahta. Against the Russian control of the Pacific the Japanese had hurled all their gathered might. By battle genius and efficiency the Island soldiers won, and athwart the front of Slavic empire they set their desperate legions. Far more was lost to Russia than men and squandered treasure, far more than prestige and power of place. The enormous stakes, even in the port of Dalny, in the forts of Port Arthur, in the East China Railway, were but incidents. The real tragedy of the war was that the vital terminus[Pg 18] of her continent railroad was alienated, and that her civilization was barred back indefinitely.

The soldiers and statesmen who carried Russia’s power across a savage continent had sought out many inventions. But by whatever means each successive territory was won, its maintenance had been by the warrant that the Slavs had gone not lightly, adventuring to conquest, but as an earnest host clearing a way for the homes and the hearths of their race. The colonist had followed the Cossack; cities and villages, railways and telegraphs, had risen behind the armies. The dawn of the twentieth century saw a mighty expanse of Siberia redeemed from a desolate waste to a land of farms and villages, of mines and industries; a native population, once hardly superior to the American Indian, not, like him, displaced and exterminated, but raised side by side with the settlers to a more equitable place than is held by any other subject people in Asia. The Russian advance had brought the establishment of the volunteer fleet plying from far Odessa to Vladivostok, and the completion of the greatest railway enterprise the world has ever seen. It had opened from Europe to the Far East a land-route more important to more people than the water-route discovered by Vasco da Gama. The fruition of a nation’s hope was lost when the Eagles went down at Port Arthur.

For those who feast at Russia’s cost the reckoning is long. Predecessors not unfamed are worthy of[Pg 19] remembrance: the Tatars who lorded it four hundred years, the Poles whose kings caroused in the Kremlin, the great Emperor, with his Grande Armée, whose stabled horses scarred the walls of St. Basil, the Turks, the Swedes,—all conquerors of yesterday. But long years must take their toll of life and gold before Russia can carry the entrenched lines along the Yalu, and reënter the redoubts hewn in the sterile hills around Port Arthur. The spoils to the victors for the present are unchallenged. The Russian way to China is not now through Manchuria.

But the ancient road of the Kiahta caravans is still unblocked. Here is the shortest route from Europe to the East. Here, through the defiles and the broken foothills of the Gobi Plateau, lies the future redemption of the great unfettered land-route to North China. The Chinese are themselves advancing to anticipate it. They have already built into Kalgan. To this trading-centre across the pale, a Russian railway may yet pass and her colonists make fruitful the unpeopled wilds of Mongolia.

In the cycles of progress old paths are reworn. Pharaoh’s canal from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea was swallowed up under the sands of three thousand years when the Genoans won a way across the Isthmus. Their track was left unsought when the Portuguese showed the route for ships around the Cape. Yet to-day the Strait of Suez is thronged with reborn commerce.

[Pg 20]

The first American highway to the Western Reserve was superseded by the better avenue of the newly built Erie Canal, yet came to its own again beneath the tracks of the Baltimore and Ohio. So, far to the westward of Japan’s outpost, the age-old caravan road, with a shadowy fantastic history dim as its dun trail across the desert, may rise to a resurrected glory as a new road to China.

Its greatness is of yesterday and of to-morrow. Unto to-day belongs the quaintness of the cavalcade that passes to and fro along its track. Over the frozen snows of winter and the rocky trails of summer there plod horse and ox and camel, sleigh and wagon and cart,—a broken line of men and beasts. Russian posts thunder past with galloping horses, three abreast. Bands of Cossacks convoy the guarded camel-trains of heavy mail for China. One meets troops of boyish recruits, singing lustily in chorus on the tramp northward, and Mongol carts and flat-featured Buriats on their little shaggy ponies, sleepy wooden villages, forests, steppes, swamps, frozen river-courses, mountain passes.

Through the kaleidoscope of races and peoples one moves in a world-forgotten life, a procession of the ages.

CHURCH OF ST. BASIL, MOSCOW

(Ivan the Terrible blinded its architect that he might never duplicate the masterpiece)

On the threshold of Siberia the traveler has turned back in manner, in ways of thought, in government, in everything, to the past. Go into one of these cities,—you are in the Germany of 1849, with the embers still hot of the fire lighted [Pg 21]by the republican movement of the young men and the industrials. The seeming chance of victory has passed them by. The iron hand is over all. One hears of Siberian Carl Schurzes, fugitives to America and to Switzerland, of the month-lived Chita Republic, of the row of gallows at Verhneudinsk, of the bloody assizes at Krasnoyarsk.

It is as if one lived when citizens gathered in excited groups in the Forum to discuss the news from Philippi; or as if, from the broken masonry of the Tuileries, there stepped out into breathing actuality the five hundred Marseillaises “who know how to die,” fronting the red Swiss before the palace of Louis, the King. Here is the reality of friends in hiding, of files of soldiers at each railway-station, of police-examined passports without which one cannot sleep a night in town, of arms forbidden, meetings forbidden, books forbidden,—all things forbidden. Here as there men thought that the new could come only by revolution. Yet one can see, despite all, the germs of improvement and the upward pressures of evolution.

Move further toward the frontier towns, where the relayed horses bring the weekly mail,—you have gone back a hundred and fifty years. You are among our own ancestors of the days of the Stamp Act. Did the General Howe who governs the oblast from his Irkutsk residency overhear the school-boys of Troitzkosavsk as they chant the forbidden Marseillaise, he, too, might say that freedom[Pg 22] was in the air. These Siberian frontiersmen shoot the deer with their permitted flint-locks as straight as the neighbors of Israel Putnam, and with spear and gun they face the bear that the dusky Buriat hunters have tracked to its lair.

Our Puritans are there, rugged, red-bearded dissenters, “Stare’ Obriachi,” Old Believers, they are called, who came to Siberia rather than use Bishop Nikon’s amended books of prayer. Yankee-like, outspoken, keen at a trade, are these big Siberian sons of men who dared greatly in their long frozen march. The grants to Lord Baltimores and Padroon Van Rensselaers are in the vast “cabinetski” estates of the grand-ducal circle, engulfing domains great as European kingdoms.

Go into one of the villages of the peasants transplanted in a body by the paternal Government. Here are the patient, enduring recruits for the army, brothers to the toilers over whose fields the Grand Monarch’s wars rolled back and forth. Though steeped in ignorance and overwhelmed by the incubus of communism, they are capable of real and splendid manhood, and will show it when their world has struggled through into the century in which we others live.

Go to a mining-camp in the Chickoya Valley. It is California and the days of ’49. Histories as romantic as those of the Sierras are being lived out in its unsung gorges,—tales of hardships, of grub-stakes, of bonanzas in Last Chance Gulches.

[Pg 23]

When the bumping tarantass rolls across the Chinese frontier into Mongolia, it enters a kingdom of the Middle Ages flung down into the twentieth century. Feudal princes, lords of armies weaponed with spear and bow, tax and drive to the corvée their nomad serfs. A hierarchy of priests whose divine head lives in a palace at Holy Urga, sways the multitude of superstition-steeped Mongols, and receives the homage of pilgrims wending their way from Siberia, from the Volga, from Tibet, from all Mongolia, to their Canterbury of Lamaism. In prostrate devotion the penitents girdle the Sacred City before whose hovels beggars dispute with dogs their common nourishment, and in whose compounds princes of the race of Genghis Khan, with armies of retainers, live bedless, bathless, lightless, in the felt huts of their race. Squalid magnificence and good-humored kindly hospitality are linked to utter brutality. Sable-furs and silks cover sheepskins worn until they drop from the body. Here and there among the natives a Chinese trading caravansary, alien, walled, peculiar, stands as of old the Hansa-town, with merchant guilds and far-brought caravan goods.

A way of adventure and strangeness, where the years turn back, is this old road of the Golden Horde, leading down past the ancestral homes of the Turks to the Great Wall.

The Cossack sentries at Kiahta look Chinaward. They have become an anomaly, this hard-riding,[Pg 24] fierce-fighting soldier class. The plow has metamorphosed into myriad farms the plains along the Don where once their ponies grazed. Mining-cuts score the hills in the Urals where once they hunted. Villages of Slavonic peasants rise along the Amur. The sons of the old warriors grow into peaceful farmer-folk, differing in name alone from their blue-eyed neighbors. Soon they must disappear in all save picturesquely uniformed Hussars of the Guard, and as a memory, chanted by young men and girls in the Siberian summer evenings when Yermak’s song is raised. The task of the Cossack, to lead in the conquest of kindred native races and to weld these through themselves into Russia’s fabric, is nearly done.

Down the ancient road lies a last avenue of advance. Eastward is Manchuria, where artillery and science grappling must decide the day with Japan. Southward is India, where England’s guarded gateway among the hills can be opened only from behind. But into Mongolia Fate may decree that the yellow-capped Cossacks, drafted from Russia’s Mongol Buriats, shall lead once more the nation-absorbing march of the White Czar. For another memorable ride, the Cossacks, who on their shaggy ponies led the long conquering way across the continent, may yet mount and take the road to China.

[Pg 25]

THE GREAT SIBERIAN RAILWAY

HOW long to Irkutsk? Seven days now, seven years when last I came.” The bearded Russian standing in the doorway of the adjoining compartment in the corridor-car of the Siberian Express gazes thoughtfully at the fir-covered slope, whose dark green stands in sombre contrast to the winter snows. The train is slowly climbing the Ural Range, toward the granite pyramid near Zlatoust, on opposite sides of which are graven “Europe” and “Asia.” Neighbors with easy sociability are conversing along the wide corridors, exchanging stories and cigarettes, asking each other’s age and income in naïve Siberian style.

Regarding the burly occupant of the next stateroom one may discreetly speculate. From sable-lined paletot and massive gold chains you hazard that he voyaged with the traders’ slow caravans in the days before the railway—that he was a merchant.

“A merchant? Optovi? No, I did not come with the caravans.”

From the triangle of red lapel-ribbon, the rank-bestowing decoration, you venture a second guess.

“Perhaps the gaspadine made the great circuit[Pg 26] to oversee the local administrations? He was a government inspector—Revizor?”

“Chinovnik niet navierno,” he answers. Most decidedly he was not an official. The suggestion causes him to smile broadly. “I was with the convicts,” he says.

Beside the line of rails curves the old post-road winding like a ribbon through the highlands.

“It was by that road we marched. Seven years of my life lie along it.”

The train swings through a cleft hewn in the living rock, steep-sided as if the mountain had been gashed with a mighty axe. It rumbles around the base of an overhanging crag while you look clear down over the white valley, with the miles of rolling green forest beyond.

“Was not seven years a long time for the march?” you venture.

“For a traveler, yes; for convict bands not unusual. We went back and forth, now northward a thousand versts as to Archangel, now west as to Moscow, now south as to Rostov. Again and again our troop would split, and part be sent another way. New prisoners would be added, from Warsaw, Finland, Samara. New guards would take charge. Some groups would go to the West Siberian stations, some east to the Pacific and Sakhalin. I, who was written down for ten years at the Petrovski Works beyond Baikal Lake, with a third commuted for good behavior, had finished my term before I got there.”

[Pg 27]

“Why did they wander so aimlessly?”

“It seems truly as a butterfly’s flight, but you others do not know the way of Russia. Very slowly, very deviously she goes, but surely, none the less, to her goal. We each came at last to our place.”

A match flares up and he lights another cigarette.

“Shall we not go to the ‘wagon restoran’ for a glass of tea?” you ask.

Along the broad aisles you walk, past the staterooms, filled with baggage, littered with bedding, kettles, novels, and fur overcoats. Everything is in direst confusion, and the owners are sandwiched precariously between their belongings. On the little tables which are raised between the seats, they are playing endless games of cards, sipping tea and nonchalantly smoking cigarettes the while. You pass the stove-niches at the car entrances, heaped to the ceiling with cut wood. The fire-tenders as you pass give the military salute. You cross the covered bridges between the cars, where are little mounds of the snow that has sifted in around the crevices; and a belt of cold air tells of the zero temperature outside. At length the double doors of the foremost car appear ahead, and crossing one more arctic zone over the couplings, you can hang your fur cap by the door and salute the ikon that with ever-burning lamp looks down over the parlor-car. Now you can sit on the broad sofa set along the wall, or doze in the corner-rocker under the bookcase, or sit tête-à-tête in armchairs over[Pg 28] a miniature table. Ladies here, as well as men, are chatting, reading, and smoking, for this combination parlor, fumoir, and dining-room is for all, not a resort to which the masculine element shamefacedly steals for unshared indulgences.

“Dva stakan chai, pajolst” (two glasses of tea, please), your friend says to the aproned chelaviek, a Tatar from Kazan.

“Stakan vodka,” you add; for you are willing to contribute twenty kopecks to the government revenues if this beverage will help out the memoirs of your friend, the convict.

“Say chass,” replies the waiter, which means, literally, “this hour,” figuratively, “at once,” actually, whenever he chances to recall that your party wants a glass of tea and another of vodka. When at length the refreshments have come, your companion gets gradually back to the reminiscences.

“Were your comrades many on that march?”

“Twenty-six from my school in Odessa,” he says. He tells of the tumult in the Polytechnic Academy, when he was a boy of sixteen studying engineering; of the barricade which the students threw up; of the soldiers sent against it; of an officer wounded with a stone, and the sentence to the mines. He tells of the journey, day after day, the miserable company trudging under the burning suns of summer and shivering under the biting cold of winter, ill-fed and in rags. He recalls how this friend and that friend[Pg 29] sickened and died; how a peasant-woman gave him a dried fish; how one of the criminals tried to escape and was lashed with the plet until he fainted beneath its strokes.

“We were a sad procession. First came the Cossacks on their ponies, with their carbines and sabres. Then the murderers for Sakhalin, and the dangerous criminals in fetters; a few women next; then we, the politicals; last, more soldiers marching behind. Far to the rear came carts and wagons with the wives and families of the prisoners, following their men into exile. Slowly we went, scarcely more than fifteen versts a day, with a rest one day out of three, for the women. In winter we camped in stations along the road.”

From the comfortable leather armchairs they seem infinitely distant and dream-like, these tales from the dark ages of Siberia. The speaker seems to have forgotten his auditor and to be talking to himself, and soon he relapses into silence. He sits holding his glass of lemon-garnished tea, like a resting giant with his shaggy beard and mighty chest. The drag of the brakes is felt through the train. “Desiet minute stoit” (ten minutes’ stop), somebody calls out. Suddenly, with an effort, the man across the table rouses from his reverie, and looks about the car, when the broad smile comes back and he says earnestly:—

“You must not think of that as the true Siberia. It was all long ago—thirty-five years. And you[Pg 30] see I who became a kayoshnik, a gold-seeker, have prospered, and work many mines. I am glad now that they sent me to Siberia. And many others prosper who came with the convicts. The old dark Siberia dies, but our new Siberia of the railroad lives, and grows great.”

He rises resolutely and shakes your hand with a vise-like grip.

“De svidania!” (Till we meet again.)

You rise with the rest, draw on your fur cap and gloves, work into the heavy fur-lined overcoat, and clamber down to the platform. A little wooden station-house painted white is opposite the carriage door. It has projecting eaves and quaint many-paned windows. In front of it is a post with a large brazen bell. On the big signboard you can spell out from the Russian letters “Zlatoust.” This is the summit station of the pass that crosses the Urals. Around are standing stolid sheep-skinned figures, bearded peasants just in from their sledges, which are ranked outside the fence. Fur-capped mechanics, carrying wrenches and hammers, move from car to car to tighten bolts and test wheels for the long eastward pull. Uniformed station attendants are here and there, some with files of bills of lading. As you walk down the platform among the crowd, you come upon a soldier, duffle-coated and muffled in his capote, standing stoically with fixed bayonet. Forty paces further there is another, and beyond still another, all the length of the platform, and far[Pg 31] up the line. What a symbol of Russian rule are these silent sentries! And what a mute tale is told in the necessity for a guard at every railroad halting-place in the Empire!

You stroll along toward the engine. Huge and box-like are the big steel cars, five of which compose the train. Two second-class wagons painted in mustard yellow are rearmost, then come the first-class, painted black, next the “wagon restoran” and the luggage-van, where the much advertised and little used bath-room and gymnasium are located. The engine is a big machine, but of low power, unable to make much speed; and the high grades and the road-bed, poor in many places, additionally limit progress. It is apparent why the train rarely moves at a rate greater than twenty miles an hour.

At first you do not notice the cold. But now that you have walked for a few minutes along the platform, it seems to gather itself for an attack, as if it had a personality. You draw erect with tense muscles, for the system sets itself instinctively on guard. The light breeze that stirs begins to smart and sting like lashes across the face. The hand drawn for a moment from the fleece-lined glove, stiffens into numbed uselessness. As you march rapidly up and down the platform, an involuntary shiver shakes you from head to foot. A fellow passenger, remarking it, observes:—

“It is not cold to-day, in fact, quite warm. Ochen jarko.”

[Pg 32]

You walk together to the big thermometer that hangs by the station-door. It is marked with the Réaumur Scale, and your brain is too torpid for multiplications. But the slightly built official, known as a government engineer by green-bordered uniform and crossed hammers on his cap, is inspecting the mercury also.

“Eight degrees below zero Fahrenheit,” he says. “Quite warm for January. It is often thirty-five degrees below zero here in the Uralsk.”

It gets colder at the suggestion. The three starting-bells ring, and everybody scrambles into the compartments.

The express rolls onward down the Urals. You stroll back to the warm dining-room and idly watch the groups around. Across the way is an elderly mild-looking officer, whose gold epaulettes, zig-zagged with silver furrows, are the insignia of a major-general. He smokes endless cigarettes in company with another officer lesser in degree, a major, decorated with the Russo-Japanese service-medal, smart of carriage and alert of look. By the window beyond is a young German, gazing meditatively at the hills and the snow through the bottom of a glass of Riga beer. A rather bright-mannered dame, with rings on her fingers and long pendants in her ears, chats vivaciously in French with a phlegmatic-looking personage in a tight-fitting blue coat which buttons up to his throat like a fencer’s jacket. A quietly-dressed gentleman, evidently in civil life,[Pg 33] is reading one of the library copies of de Maupassant.

Outside, cut and tunnel, hill, slope, and valley, green forest, white drifted snow, and bare craggy rocks, the Urals glide past. The little track-wardens’ stations beside the way snap back as if jerked by a sudden hand, and the telegraph-poles catch up in endless monotony the sagging wires.

The Tatar waiter goes from place to place, clearing off the ashes and the glasses, and getting ready for dinner. There is a table-d’hôte repast, the Russian obeid, a meal which starts with a fiery vodka gulp any time after noon, and tails off in the falling shadows of the winter sunset with tea and cigarettes. Or, if one wishes, he may press the bell, labeled in the Græco-Slavonic lettering, “Buffet,” and dine à la carte.

“Il vaut mieux essayer le repas Russe,” says the quiet reader of de Maupassant, joining you.

He is duly thanked for the advice, and we beckon to the aproned waiter. At once the latter passes the countersign kitchenward to set the meal in motion, and puts before us the little liqueur-glasses and the bottle of vodka. While we still gasp and blink over this, he has gotten the cold zakuska of black rye-bread and butter, sardinka, salty beluga, and cold ham, and has started us on the first course. Then comes in, after the omni-inclusive zakuska, a big pot of cabbage-soup which we are to season with a swimming spoonful of thick sour cream. The[Pg 34] chunky pieces of half-boiled meat floating in it are left high and dry by the consumption of the liquid. The meat becomes the third course, which we garnish with mustard and taste.

“Voyons!” the Frenchman observes. “Of the Russian cuisine and its method of preparing certain food-substances one may not approve. Frankly it calls for the sauce of a prodigious appetite. But contemplating the obeid as an institution so evolved as to fit into the general scheme of life, it finds merit. The Russian meal is a guide to Russian character.”

“What signifies this mélange of raw fish, eggs, and great slices of flesh, and mush of cabbage-soup?”

“Not that the Russian has no taste. It is that he sacrifices his finer susceptibilities to his love of freedom. A regular hour for meals would seem to him a sacrifice of his leisure and convenience to that of the cook. The guiding principle of the national cuisine is that all dishes must be capable of being served at any time that the eater feels disposed.”

This is a problem to put to any kitchen, we allow. Napoleon’s chef met it by relays of roasting chickens. But one cannot keep half a dozen fowl going for each household of the one hundred and forty million inhabitants of Russia. Thus sturgeon is provided, and sterlet, parboiled so that it tastes like blotting-paper; and the filet that is called “biftek,” and the oil-sodden “Hamburger,” that is[Pg 35] dubbed “filet.” These can be started at nine in the morning, and be removed at any time between that hour and nine at night, without any appreciable change in taste or texture. The cook of the restaurant, like his brethren of the Empire, has laid his professional conscience sacrificially upon the national altar of unfettered meals. If the obeid is not a triumph in culinary art, it is at least a signal example of domestic generalship.

We have advanced without a hitch to roast partridge, with sugared cranberries, which our friend washes down with good red wine from the Imperial Crimean estates. We get through a hard German-like apple-tart, and reach the last item of cheese.

When the mighty meal is over, we order tea, light cigarettes, and lean back in the armchairs to chat and note how our neighbors are getting through the time.

At the far end of the room a Russian has joined the French lady and her escort. They are celebrating some occasion that requires heaping bumpers of champagne. The babble of their conversation is in the air. It seems to refer to the comparative appreciation of histrionic talent in Rouen and Vladivostok!

Somebody is being treated to a dressing-down in the latest Parisian argot. “Ces sont des betteraves là-bas!” one hears scornfully above the murmurs.

Across the way some Germans are engaged with beer-schooners. One of them gets excited and brings[Pg 36] his fist down upon the table. “Arbeit in Sibirien nimmer geendet ist; they always want more advice about their gas-plants.”

In the lull that follows the explosion, a gentle English voice floats past from the seat behind us. “And so I told him that the station had nearly enough funds, but we needed workers, more workers.” It is the English medical missionary on his way to Shanta-fu, discussing China with the American mining-engineer, bound for Nerchinsk.

The piano, under the corner ikon with its ever-burning lamp, tinkles out suddenly, and a man’s voice starts up—

He misses a note every now and then, which does not embarrass him in the least. Caroling gayly to his own accompaniment, he forges ahead. The crowd in the armchairs around the room, consuming weak tea or strong beer, and smoking, all join with an untroubled accord and versatile accents, French, English, and Russian, in the blaring chorus, “The man that broke the bank at Monte Carlo.”

The train rocks faster on the falling grade; little by little the mountains drop away; gradually the mighty forests become dwarfed into scattered clumps of straggly birches, and the great trees dwindle into bushes; lower and still lower fall the hills, until all is flat. As far as the eye can see are the snow-covered[Pg 37] wastes, treeless, houseless, lifeless. The lowest foothills of the Urals have been passed. It is the beginning of the great steppes.

Slowly the daylight wanes. The gray darkness deepens steadily; it seems to gather in over the gliding snow, and the peculiar gloom of a Siberian winter’s night closes down. At each track-guard’s post flash with vivid suddenness the little twinkling lanterns of the wardens of the road. Involuntarily conversation becomes less animated and voices are lowered; the spell of the sombreness is over all.

Soon the electric lamps are lighted, and from brazen ikon and sparkling glasses flash reflections of their glitter. Curtains are drawn, which shut out the enshrouding blackness. The piano begins tinkling again; the waiters come and go with tea and liqueurs; the babble of conversation rises; and the idle laughter is heard anew. Darkness may be ahead, behind, and beside, but within there is light—enjoy it.

The train slows for a halt. Station-lamps shine mistily through the brooding night. Lanterns bob to and fro on the platform as fur-capped train-hands pass, tapping wheels and opening journal-boxes. At each door a fire-tender is catching and stowing away the wood which a peasant in padded sheepskins is tossing up from his hand-sled below. It is Chelliabinsk, whose old importance as the clearing-house of the convicts has been passed on to the new city of the railroad. Here the just completed[Pg 38] northern branch, linking Perm to Petersburg, meets the old southern line from Samara and Moscow.

A short stop and the train moves on again. The day is done and gradually each saunters into his own warm compartment, which the width of the Russian gauge makes as large as a real room. One can read at the table by the window, under the electric drop-light, or, propped in pillows, one can stretch out luxuriously on the easy couch that is nightly manoeuvred into an upper and lower berth. Practically always after crossing the Urals, the number of passengers has so thinned out that each may have a stateroom to himself.

Presently you push the bell labeled, “Konduktor.” A uniformed attendant appears standing at the salute. “Spate” (sleep) is sufficient direction. The sheets and pillows are dug out and the transformation of the couch into a bed is effected. “Spacoine notche” (good-night) he says, and you fall asleep to the rhythmic throb of the engine.

During the following hours the train enters the Tobolsk Government, the oldest province of Siberia, whose 439,859 square miles of area, nearly four times as large as Prussia, extend roughly from the railroad northward to the Arctic Ocean, and from the Urals eastward so as to include the lower basin of the Ob-Irtish river system. This ancient province has seen much of Siberia’s history, whose predominant features have been two, growth and graft.

BRIDGE OVER THE IRTISH

ALONG THE TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILWAY

[Pg 39]

Out of evil, somehow, in a marvelous way has been coming good. In the earliest days, with what smug satisfaction did the Stroganovs find that the native inhabitants would trade ermine for glass beads! Yet the fruit of their sharp dealing and purchased protection and special privilege was the expedition that won Sibir, founded Tobolsk, and opened to Russia the way into northern Asia. The imperial commissioner who came to Tobolsk shortly after Kutchum Khan’s overthrow, to collect the yassak tribute of ten sable-skins for each married man and five for each bachelor, was detected culling the choice skins for himself, and substituting cheap ones for his master. But his agents had sought out the paths and extended the Russian Empire far into the northern forests.

By despotic oppression the inhabitants of Uglitch town, condemned for testifying to the murder of Dimitri, the Czarevitch, came here into exile in 1593, carrying with them the tocsin-bell that had tolled alarm when the Czar wished silence. But they, together with the deported laborers settled by the same arbitrary will along the Tobol River, started the permanent settlement of the new realm.

A succeeding functionary called on the natives for a special tribute of ermine for the Czarina’s mantle. He collected so many bales of it that the taxed began to wonder at the stature of the “Little Mother,” and sent a special deputy to Petersburg. The legate discovered that the Empress was as[Pg 40] other women, and on his disclosures the official was unable to save his own, let alone the ermines’ skins. Yet while the governor was plundering the fur-merchants of Tobolsk, the frontiers were extending, until by 1700 they reached eastward to Kamchatka and Lake Baikal, southeast to the Altai foothills at Kuznetz, and north to the Arctic Ocean.

At Tobolsk in 1710 Peter the Great established the capital of his reorganized province of Siberia. Prince Gagarin, whom he appointed its first governor, found here a systemless extortion unworthy of an efficient statesman. With the thoroughness of genius he built up in the unhappy province a regular organization of rascality. His pickets patrolled the roads into Russia, to prevent the escape of those who might carry the tale of his oppression. He arranged with high officials at Court that any petitioners who evaded this frontier net should be handed over to an appropriate committee. Thus fortified, he began collections of as much as could be wrung from his luckless subjects. Every traveler paid Gagarin’s tariff, every farmer sent him presents of stock, every trapper forwarded the best of his catch. The fur-trader’s donations and the merchants’ loans were assisted into Gagarin’s warehouses by thumbscrew and thonged knout.

While these things passed in Tobolsk there came periodically to Petersburg delegations of outwardly contented citizens attesting the wisdom of their governor. They brought to the Czar and the Grand[Pg 41] Dukes, in addition to the punctiliously rendered tax yassak, gifts of especially fine furs. Such was the completeness of Gagarin’s control that not an echo of the true state of affairs reached the ears of the astute Peter.

At length, in 1719, Nesterov, the Minister of Finance, was privately approached by some Tobolsk merchants and was supplied with evidence sufficient to hang half the officials in Siberia. In a dramatic presentation the Minister furnished this to the Imperial Senate, showing so bad a case that Gagarin’s own agents in the ducal circle rose up against him. The Czar sent Licharev, a major of the Guard, to Siberia, to proclaim in every town and hamlet that Gagarin was a criminal in the eyes of the Emperor. As this messenger approached Tobolsk, official after official came out to turn state’s evidence, trying to assure his personal safety. The highways to Russia were guarded by Peter’s own troops, with orders to seize all outgoing travelers who might be transporting Gagarin’s accumulated spoil, which with commendable prudence the Czar had allocated to himself.

When Peter was in England he had remarked casually to an acquaintance, “In my realm I have only two lawyers, and one of these I intend to hang as soon as I get back.” It was particularly unfortunate for this ex-governor that the remainder of the legal profession did not feel himself called upon to explain to Peter the Gagarin campaign contributions. No one ever needed an attorney more. He[Pg 42] was under trial before an imperial judge who did not know a technicality from a tort, and whose preliminary procedure was to order a reliable gallows.

For some score of years subsequent to Gagarin, the governors of Siberia were, in any event, moderate. The province grew apace, increased by exiles, by land-seeking colonists, by raskalniks,—nonconformists of the Greek Church, self-called “Old Believers,”—who preferred to come to Siberia rather than follow Peter’s orders and shave off their beards.

Then Chicherin the Magnificent came. His life was a round of celebrations. Wonderful stews he concocted for his sybaritic revels. At obeid an orchestra of thirty pieces supplied the music. Artillery in front of the residency saluted him with salvos when he drove out. In Butter-Week all Tobolsk drank the spirits which their governor bountifully provided. It is hardly necessary to say that the money for these entertainments did not come from Chicherin’s private purse: the city merchants groaned over forced loans and benevolences; and at last their cry reached the throne, and Chicherin too was removed.

With his passing, the Tobolsk Province fell to less spectacular rulers, but under good and bad it grew steadily, until in 1860 there were a million inhabitants within its borders, a population which at the present time has risen to a million and a half. Some forty thousand of these are exiles; some eighty[Pg 43] thousand raskalniks; and forty thousand Tatars, who feed the flocks where their ancestors once bore sway, living peacefully side by side with the Russians. Some fifteen thousand are descendants of the Samoieds and Voguls with whom the first Stroganov from the adjoining Russian province of Archangel traded his wares. Some twenty thousand are Ostiaks whose forebears were alternately allies and enemies of Yermak.

The capital city, Tobolsk, on the Tobol River hard-by its junction with the Irtish, has grown from a precariously held camp of two hundred and fifty fugitive Cossack soldiers to a city of thirty thousand. Tiumen, the easterly city on the Tura River, another of Yermak’s camps, has grown into a great distributing-centre for produce brought by the river-highways. From the railway line northward as far as the city of Tobolsk extends a farm-belt, a continuation of the black-earth region of great Russia. The fertility of the land may be judged by the number of villages met as the train speeds on, and the large proportion of enclosed fields on both sides of the track. Some of the finest agricultural soil in the world lies here, such soil as composes the prairies of Minnesota and Dakota. Three million head of live stock graze in the district, which has a yearly production of ten million hundredweight of wheat alone, four million of rye, and nine million of oats. Five million more settlers may live and thrive, and the harvest will feed the ever-growing[Pg 44] cities of Europe when Siberia comes to be the new granary of the old world. The stress and turmoil of Tobolsk are passed. Happy the people who have no annals!

Gradually, as the train rolls eastward beyond the Ishim River Valley, the farm country opens out into the unfenced prairie of the Great Steppe. The clustered wooden villages that flanked the line through Tobolsk appear less and less frequently, till at last we seem to glide over an immense white sea, frozen into perpetual calm and silence. Here and there a gray thicket of stunted trees and bushes, here and there a grove of naked-limbed birches, mutely exhibit Nature’s desolation.

As the sullen landscape bares itself, one thinks of the prison caravans tramping these wastes; of the early neglected garrisons which Elizabeth’s favorite General Kinderman proposed to victual on crushed birch-bark and relieve the Crown of their expense; of all the misery and the wrong that the steppes of Siberia have symbolized. No sign of man’s handiwork or of Nature’s kindliness is seen,—only the cold snow and the bare birches, while regularly as the ticking of a clock the telegraph-poles and the verst-spaced stations snap back into the wastes. The dominant reflection is not, how great is the achievement which has mastered these steppes! but, how infinitesimal is all that man has done in this ocean of untrodden snow! Hour after hour we are driving on. Yet never is there passed a landmark[Pg 45] to conjure into imagination a picture of progress. One moves as in a nightmare, where he runs for seeming ages, hunted forward, yet can never stir from the spot. The horizon-bounded circle of vision is as the ever-receding rim of a giant dome, the rails ahead and behind bisecting its white immensity. Above, the vast bowl of the blue sky dips and meets it, imprisoning us. Where are the fields and villages; the bustling activity of human life that tells of man’s mastership? Hour after hour passes without a change in the drear monotony of the landscape; for miles on miles not a trace is seen of human dominion. Grim Nature spreading her shroud over plain and pasture is despot here, and Winter is ruler of the Siberian Steppe.

One could ride due south a thousand versts, through Golodnia the “hunger steppe” to the borders of Turkestan, and find the same monotonous plain, snow-covered save where the dryness of the south has thinned its fall. One could ride from the Caspian Sea due east to China, with each day’s march a counterpart of the rest. Five hundred thousand square miles of area are covered with grass and gaudy flowers in the spring, with low brush and green reeds where the salt swamp-lakes receive the tribute of snow-fed streams. In midsummer the growing grass scorches under a heat of 104°. In winter snow is everywhere,—in feathery flakes that the midday sun does not soften during whole months of a cold which is a ferocity. Thirty to forty degrees below[Pg 46] zero is not unusual, and the land is swept by bitter winds that pierce like daggers through doubled furs and felts. Yet there dwell on the central plateau of Asia a million people, and one million cattle and three million sheep are scattered over the tremendous range. As the herds have become hardened through the centuries and survive in measure despite the severity, so also have the men. From the train-windows now one may chance to see infrequent straggling herds of long-horned cattle, lean and gaunt, scratching away the snow in search of food. Mounted on little shaggy ponies are figures buried in skins, who keep guard over them.

One detects a new type among the crowds at the stations,—flat faces, round eyes, square thickset bodies. Here on the borderland, the old race has fused with the Slav and has become metamorphosed. The sons of the Tatars, whose very name was distorted into that of a dweller in Tartarus by those who feared their fierce valor, have become shopkeepers, train-hands, waiters, and butchers, who come to sell meat and milk to the chef of the wagon restoran. Sometimes, at the stops, figures, gnome-like in enveloping red capote and grotesquely padded furs, hold their ponies with jealous rein, staring curiously at the locomotive and passengers.

DINING-CAR SALOON, VIEW OF THE LIBRARY

Looking long from the windows at this steppe, a drowsy hypnotism steals over the mind—a dull stupor of unbroken monotony. It is better to do as the Russians—pay no attention whatever to the [Pg 47]landscape outside, but make the most of the life within the moving caravansary,—cards and cigarettes and liqueurs, tea and endless talk, with yarns that take days for the spinning.

The uniformed judge, passing by, joins you. He is traveling to a new appointment with his swarming family of children, shawl-decked females of unknown quality and quantity, the household bedding, and the ancestral samovar, all crowded into one stifling compartment. He discusses volubly the confusions of the Code, and propounds a unique theory of his own as to Russian jurisprudence, to the effect that all the best laws of other nations have been adopted, with none of the old or conflicting enactments repealed. The general drops into the circle. He is interesting when one has pierced the crust, but dogmatic. At every station the soldiers of the garrison, not on sentry-duty, jump to one side, swing half-around, and stand at the salute until he passes, to the huge inconvenience of the porters. He would undoubtedly vote the Democratic ticket to repay Mr. Roosevelt for putting Russia under the alternative of stopping the war perforce, or forfeiting sympathy, when Japan was said to be breaking under the strain.

“Russia was beaten this time. What of it? Nietchevo!” says the general.

“Nietchevo,” we echo, as we sip our tea.

“But the Japanese are wily insects,” observes his companion, the young service-medaled major. “I[Pg 48] was in Vladivostok when our prisoners came back. They tried to get money for the checks the Japanese had given them. That was how the big mutiny began. You know, when our men were taken captive, the Japanese treated them very well, much good food, vodka, let them write home all about it, and gave them enormous pay, six yen, three dollars a month, charging the expense all up to the Czar for after the war. When at last the prisoners were to be released, the Japanese promised every man double pay, twelve roubles. But they gave them the money? No, the insects gave them each an order payable by the Russian commander in Vladivostok. So the transports came, and these men were sent ashore with these checks in their hands, and they went up to the commandant of the city, and asked for their cash that the Japanese had promised. What money did the commandant have for them? What could he do? He ordered them to go away. So they stood and discussed on the street-corners. And more men still came from the transports. Then they said, ‘We will ask the general of the forts.’ So they marched to the forts in a big crowd, and the general he also told them to go away. For a long time they talked and they persuaded the sailors to help them. So they went again to the forts, and the sailors shot at the forts, and the general ordered the artillery to shoot. But the artillery would not, so the men broke in and killed the officers and got arms and went back to the city commander. Him,[Pg 49] too, they killed, and all Vladivostok was in mutiny for two weeks. Not an officer dared show himself. General Orlov persuaded them to let him into the town. Then many were shot, but at last the city was quiet. The Japanese are very sly insects.”

His story ends and the two officers go back to join their families. The train throbs on across the steppe.

The German gas-plant drummer, with his new Far Eastern outfit, is gathering from the missionary doctor details of treaty-port life, which are being treasured up as valuable reference data. The French fur-merchant dips back into his library copy of de Maupassant.

The rigor of the outside scene seems at length to be changing. A few scattered houses appear, and trees and fenced fields, and villages, with curling smoke rising from the chimneys. Men and children are walking about, and finally we come to the Irtish River, over which the train rumbles on a half-mile bridge. Spires and gilt domes are visible, dark wooden houses, and bright white-painted churches with green roofs. Droshkies and carts are passing in the streets, and presently we draw up to the station of Omsk, the second city of Siberia.

The junction of the Trans-Siberian Railway with the Irtish River, which is 2520 miles long and open from April to October, would of itself make Omsk a centre of great strategic importance. But in addition to this main river-highway, which is navigated by some hundred and fifty steamers, there are affluents[Pg 50] by which one can sail from the Urals to the Altai, from the Arctic Ocean to China, and these lines of communication centre here.

From Omsk, following the Irtish down past Tobolsk, one can steam by the Obi to Obdorsk, within the Arctic Circle. Indeed, a regular grain-export service was planned via the Kara Sea to London by an ambitious Englishman. It failed after some promise of success, because of the ice-packs in the Gulf of Obi. From Omsk, following the Irtish upstream, steamer navigation extends as far as Semipalatinsk, in the Altai foothills. Smaller craft may go nearly to the Chinese frontier.

By the Tobol and Tura rivers, Tiumen, in the Ural foothills, may be reached, four hundred and twenty miles from Semipalatinsk. By ascending the Obi, a boat may go fourteen hundred and eighty miles east from Tiumen to Kuznetz on the Tom; through a canal from an Obi confluent the Yenesei River System may be entered, and from it by a short portage the Lena System. In all twenty-eight thousand miles are navigable by small craft, and seven thousand miles by steamer. Omsk is the pulsing heart of this mighty interior waterway system.

CITIES OF NEW RUSSIA

Tiumen

Tomsk

Perm

The train leaves the station, which is at a distance from the town, and once more we are en route. The eye rests gratefully upon the ribbon of cultivated fields which follow the Irtish down. But we reënter the steppe, and again the desolation settles [Pg 51]over all. In hours of looking, not a habitation is seen, not an animal, not a tree,—only the same white billows. This Barbara district in the Tomsk Government has an area of fifty thousand square miles. Kainsk, some seven hundred versts from Chelliabinsk, is the centre. The section, though covered with the fertile black earth of the adjoining regions, is, owing to lack of drainage and adequate rainfall, arid and almost untilled.

The round-faced civilian from the compartment further up, whose familiarity with the country has made him a welcome accession, joins us at the window. He looks out over the level plain of the Barbara Steppe with manifest satisfaction.

“You admire the landscape?” we ask satirically.

He smiles. “We got big money when the line went through here. I made my first fortune then.”

He sighs at the memory of old times, and tells of the railway-building days when the Czar had given the order for a road across the continent, and the soldiers of fortune, of whom he was one, had gathered to the task.

“Not a kopeck had I when the Dreyfus brothers made their big speculation in Argentine wheat and went down, leaving us young clerks stranded in Kiev. You know Kiev? Great pilgrimages come there to see the bodies of Joseph and his brethren, all preserved just as when they died. We heard by accident of a grading job under a big contractor out here. None of us knew anything about construction,[Pg 52] but three of us grain-clerks wrote a letter saying we would put the work through, and started. We had just enough money to get to Samara. In Samara was a merchant much esteemed, whom I went to see. He went on our bond, never having seen us before, and gave us enough money to come. So it was in the old days. The country was flat as a board. We had but to lay down the ties and spike the rails. Thirty versts we made of this line. It cost us thirty thousand roubles a verst, but we got fifty thousand. Would that we might do that now again.”

The contractor, his round jolly face glowing with the recital and his eyes shining through gold-rimmed glasses, is entertaining a growing company, for the judge has stopped to gossip, and the railroad official.

“I took my money and bought an estate in the country of the Don Cossacks,” the contractor is saying. “I paid ten per cent to the Government for taxes when I bought the land. I had to pay no more taxes then all my life, but my heir would pay taxes, or, if I sold, he who bought would pay. So it was done in the Hataman Government.”

“It is just,” says the judge. “Why should they, who get the property, not pay taxes?”

The contractor shrugs his shoulder and continues: “For five years I farmed, and though I had a German overseer, I did not prosper. So I went to one of the cities of Russia and thought to put in a tramway. The men of the city said, ‘Are all the horses dead? He of the spectacles is mad.’ Yet by importunity[Pg 53] I got them to give me the right to make a tramway. There were in Petersburg then many Belgians, with much money, wishing to give it away. So I went to them and said, ‘Here is a great franchise, but who will build the line and gain the riches?’

“‘We will, we will,’ said the Belgians.

“From them I got a hundred and eighty thousand roubles clear, and an interest. I sold the interest quickly to other foreigners, Frenchmen, and went away. Yes, the tramway was built, and the people crowded to ride on it as I had said. But when it was going well, and the profits were yet to come, the people said, ‘Shall foreigners oppress our city?’ So the town bought the tramways for what they said was the cost, and the Belgians went away. And they did not come back to Russia. Thus were many railways and tramways built and taken. The foreigners will not come back now, and Russians too do not enter these pursuits, lest the Government come after them later. It is hudoo (bad).”

“But is it not worse that these men should make a tramway and draw vast money from the people?” says the railroad official. “For me, I think the Government should do it all.”

“Ni snaia, I don’t know,” says the contractor. “But I who bought stocks with the Belgians’ money (foolishly thinking that the business which I knew not was safe, while that which I knew was shaky), I will not give again to the stock-people the money[Pg 54] I shall make from the oil-fields of Sakhalin, where I go now.”