Title: The run

Author: John Hay

Illustrator: David Grose

Release date: October 17, 2025 [eBook #77074]

Language: English

Original publication: Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc, 1959

Credits: Steve Mattern and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE RUN

[Pg 1]

Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Garden City, New York

1959

[Pg 2]

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 59-11598

Copyright © 1959 by John Hay

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

[Pgs 3-4]

To my father and mother:

Clarence Leonard Hay

and

Alice Appleton Hay

[Pg 5]

This book mirrors an attempt to go farther afield, from one man’s center. Its writing represented a kind of migration in itself. We all undertake them, whether we like it or not, near or far. To follow on the track of fish, birds, or any other animals, might be both discovery and repetition, because it might mean to go exhaustively into the nature of being alive. The alewives helped to open the world for me, although the outcome of their circling was always beyond knowing.

Above all this book is about one race which has an equal status with us in the great motions of this planet. Men may be highest, or so men say, but they cannot be complete without granting equal dignity to the unsurpassed uniqueness of other forms of life. One ought to be able to say: “Here is a life not mine. I am enriched.”

Not a great deal has been written specifically about alewives, but the three published works I found most useful as an introduction were: Fishes of the Gulf of Maine, by Bigelow and Schroeder, published by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service; A Report on the Alewife Fisheries of Massachusetts, by David Belding,[Pg 6] published by the Massachusetts Department of Conservation in 1921; and Factors Influencing the Migration of Anadromous Fishes, by Gerald Collins, Fishery Bulletin No. 73 of the Fish and Wildlife Service. I also received some helpful information from the Fisheries Research Board of Canada; and the Department of Sea and Shore Fisheries of the State of Maine, as well as its Department of Inland Fisheries and Game. Maine has been undertaking an important research and educational program with a view to rehabilitating the alewife fisheries.

I am greatly indebted to Hal Turner of Woods Hole, Dr. David Belding of Welfleet, and John Burns of the Massachusetts Department of Natural Resources, Division of Marine Fisheries, for answering my questions so readily and courteously; and of course, much thanks to Harry Alexander. He guards a good run.

[Pgs 7-8]

| Foreword | 5 | |

| I | Waiting Weather | 9 |

| II | Arrival | 19 |

| III | Dried Fish: an Informal History | 27 |

| IV | The Reproductive Urge | 45 |

| V | The Nature of an Alewife | 53 |

| VI | Puzzles and Speculations | 63 |

| VII | Port of Entry | 75 |

| VIII | The Common Night | 83 |

| IX | The Hunt | 89 |

| X | Transition: Salt and Fresh | 99 |

| XI | Up the Valley | 111 |

| XII | The Imperfect Ladder | 121 |

| XIII | Persistence | 129 |

| XIV | Spawning: the Dance | 141 |

| XV | The Return | 151 |

| XVI | The Young Follow After | 161 |

| XVII | The Power of Fragility | 175 |

| XVIII | Going Out | 183 |

[Pgs 9-10]

[Pg 11]

It was in March, in comparative ignorance about their lives and habits, that I started looking for the alewives. This is the time of year when a few forerunners usually come in from the sea, in spite of the cold airs and waters that still grip the narrow land of Cape Cod. I had seen these migrant fish before, during a previous season, but from the road, so to speak. I had never followed them as if they challenged communication.

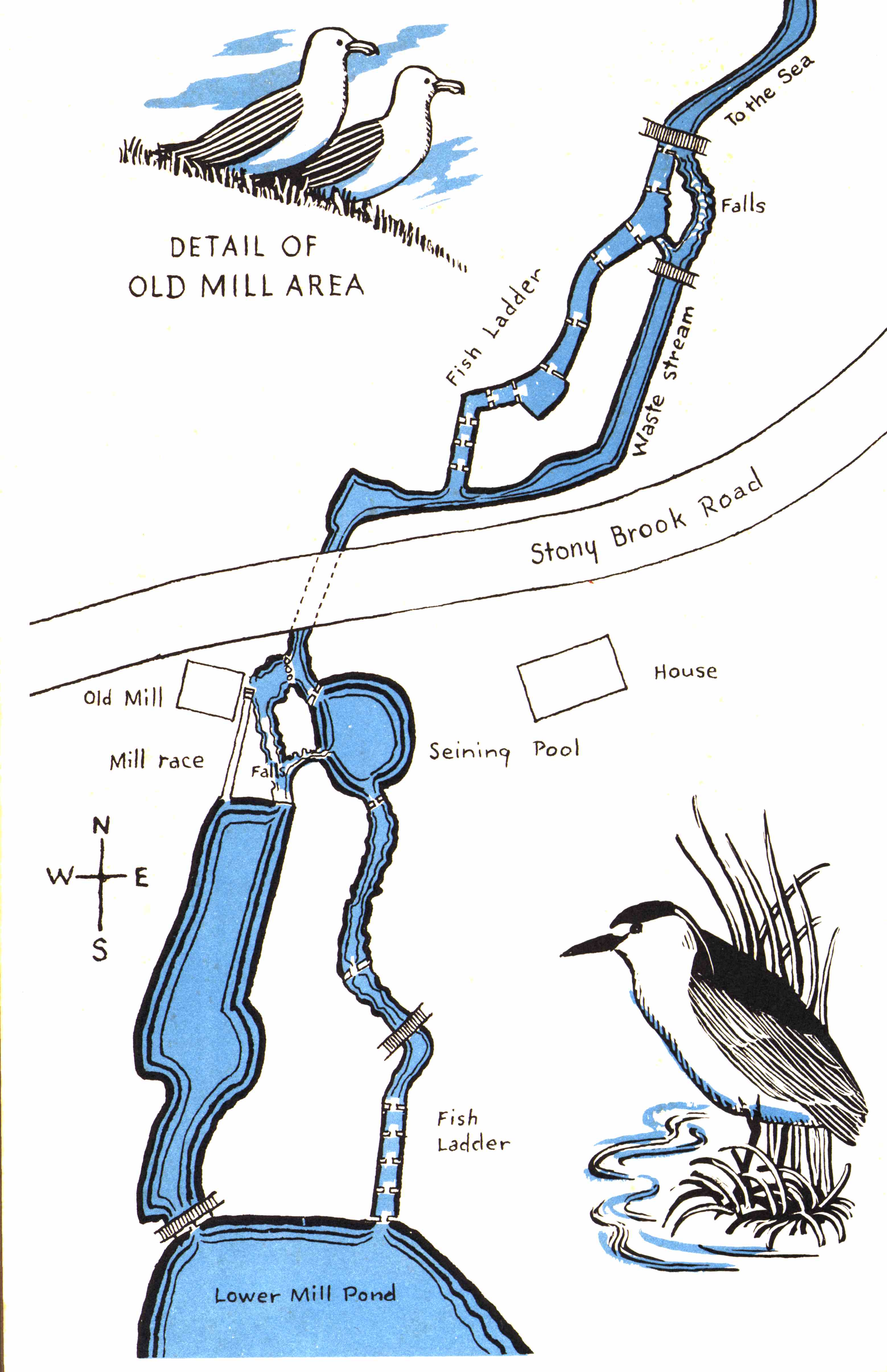

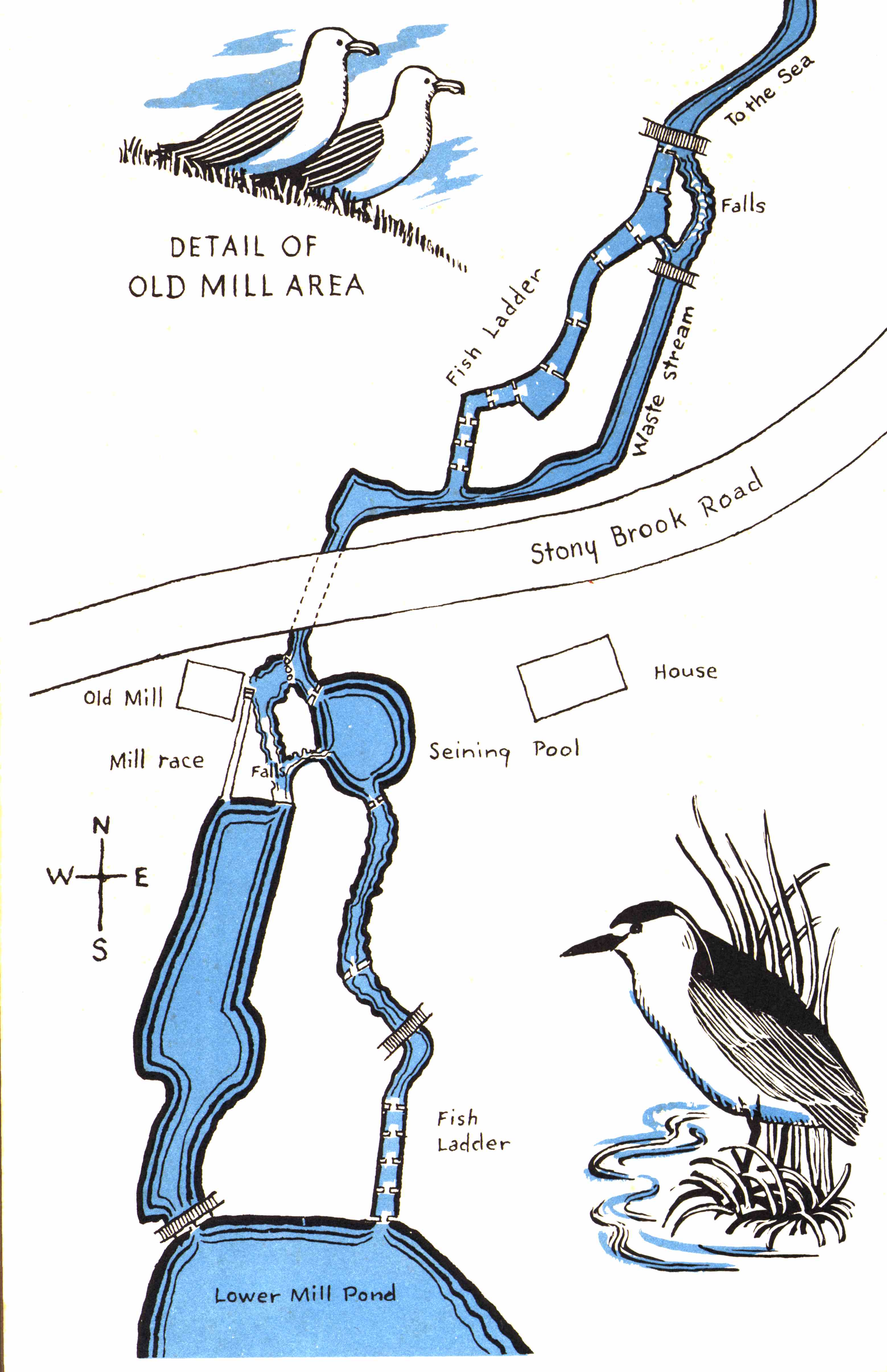

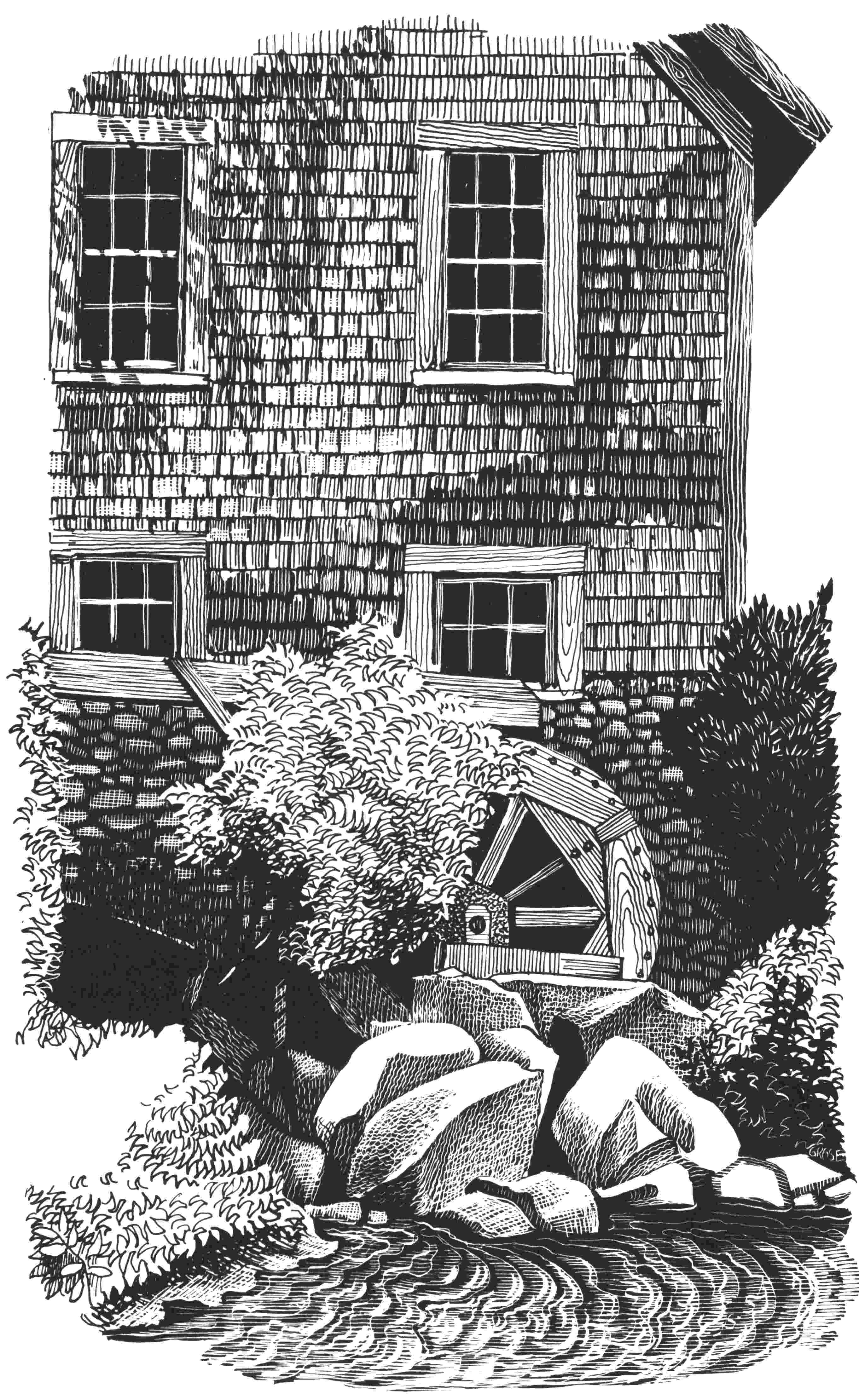

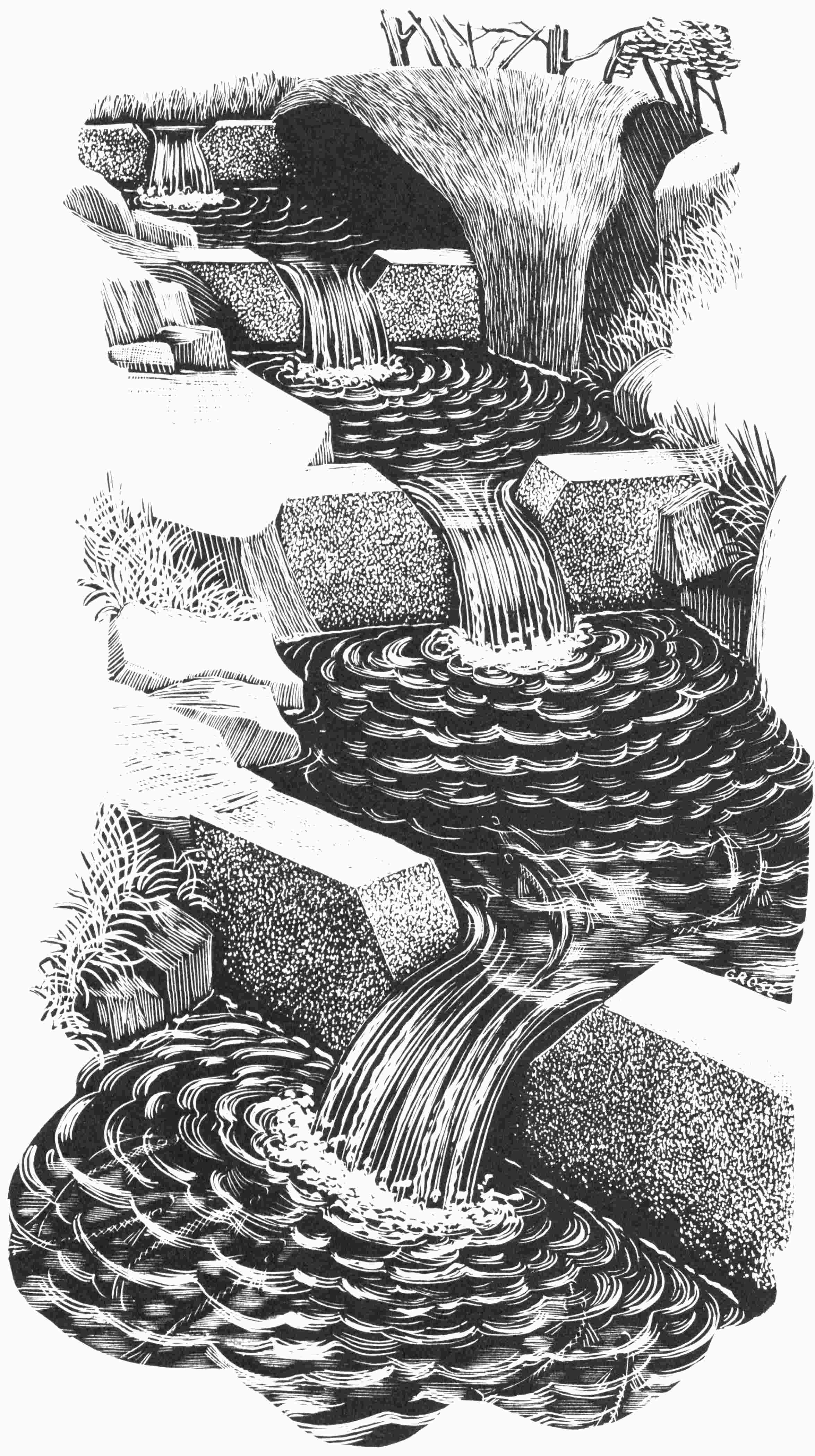

The place I started from was the Herring Run in the town of Brewster, part of a little migratory inland route by which the alewives travel up from Cape Cod Bay to the inland ponds where they spawn. At the Herring Run the waters of Stony Brook pour down from an outlet north of these ponds—three of them, all interconnected: Walkers, Upper Mill, and Lower Mill. The flow then goes over a one-and-a-half-mile stretch, first over the fishway, a series of concrete ladders and resting pools built through rocks and high land, the area of the Herring Run, then through a valley of abandoned cranberry bogs bounded by low[Pg 12] hills; and finally it elbows through tidal marshes to Paine’s Creek, its mouth on Cape Cod Bay. This little river was called Sauquatuckett by the Indians and was subsequently known as the Setuckett River, Mill Brook, and Winslow’s Brook. At its falling headwaters the first water mill in this region was built, and one of the later mill buildings is still standing—it has an old water wheel that is still in working order and is used to grind corn as a tourist attraction. By the time the mass of tourists arrive the alewife migration, aside from the “fry,” hatched in the ponds and returning to salt water, has about run its course. They can still take pictures of the old mill in July or August, but they have probably missed a more vital antiquity.

The initial facts about the migration are these: each year, close in time to the vernal equinox when the sun crosses the equator and day and night are of equal length, this member of the herring family begins to enter innumerable inlets and tidal estuaries down the length of the Atlantic coast, from Newfoundland to the Carolinas. Scientifically known as Pomolobus pseudoharengus (also, under an older classification, Alosa pseudoharengus, along with species of shad), the alewife is an “anadromous” fish, meaning that like the salmon and shad, but unlike its relative the sea herring, it grows in salt water but leaves it as a three- or four-year-old adult, to spawn in fresh. A “catadromous” fish, like the eel, does just[Pg 13] the opposite, growing up in fresh water and spawning in the sea.

The alewives, I learned, were due to come in from the Bay when the temperature of the brackish water that flowed into it was warmer than that of the salt water. In fact, a local resident had already noticed a group of eight or ten alewives of apparently large size that had appeared in the brook a few days before. Their arrival was a token that the land, though still cold, was warming up more quickly than the sea—just about the time a few male red-winged blackbirds showed up too, in advance of housekeeping. But if some began their migration in March, the first big run was not likely to come until the middle of April or later, depending on how long and cold a winter it had been. During an exceptionally cold season the alewives might not appear in volume until the first days in May. Where were they now, and what were they doing? Schooling somewhere offshore, and waiting to move in?

I stood on the beach and the sea still looked and felt and smelled as raw and cold as winter—iron-gray, massive, keeping its counsels—although, as I understood it in an incomplete way, the waters were undergoing seasonal adjustments at varying depths in the shallow coastal areas. Spring changes would begin to take effect. Perhaps I knew them, smelled them, on the sea wind. I was impatient. I wondered what specific combination of length of life, biological[Pg 14] responses, currents, tides, the composition of the sea water, might impel one roving school of fish to leave the sea and start inland.

March, that season of the whole air hesitating and blowing back and forth, the circuit of the compass, especially in low-wooded seaside lands, is a time of hesitation, preparation, and violence. It is waiting weather.

The tempo had changed—it was late in February I had felt it. The winter fist began to unclench a little. Before another day of frost, sleet, or wet snow, spring rain might bucket down in the evening, or freak lightning might crack the sky. The days were gray and raw more often than not, but when the sun shone it was sheer grace. One night there were wands of light shuddering against great, shimmering, flushed curtains on the sky wall over Cape Cod Bay—being the legendary northern lights, grandly named aurora borealis. The following day was cold, dull, and obdurate again.

Then when the temperature began to ease up occasionally from the thirties to the forties, as March went on, a surprise snowstorm came howling in. Poles snapped; wires broke, and the resulting power failures lasted for several days, during which some people rediscovered fate. The radio, before communication was entirely cut, sounded off about the inexorable as cars and trains were stopped and men died after shoveling snow. In that whole weather always cast beyond complaint or prediction, this storm[Pg 15] only represented a temporary arrest. Our primal agent the sun still had the season’s growth in hand, more various than fate; which is not to minimize the tragedies along the way. Some days after the storm I found four or five male bluebirds in spring plumage all huddled dead in the bottom of a birdhouse—a pathetic brilliance. The entrance had probably been blocked by wet snow after they had taken refuge there.

As the growing sunlight played a steady tune, so the alewives, perhaps less affected by local storms than we, were due to come in, if only in small numbers. Where were they? I stopped by the Herring Run where the brook was full of loud cold water, but empty of fish. All the same, Harry Alexander, the alewife warden, was there, giving a display of public confidence. He had taken up his annual stance on Stony Brook Road, which bridges the run, and with a truculent punch of his lips against his pipestem, he made ready for the coming season.

In a world era, this is a local man. He has the cast and sense of place about him and some of its accumulated age. I have seen it in other men who have spent their lives in the same country environment. He is heavy, ruddy, thickset—an old boat in a Cape port. During his tenure on the alewives committee he seems to have developed a proprietary attitude about the run which probably exceeds his authority, but very few people object.

He certainly makes more of the job than the small[Pg 16] wages he gets from the town; and in years past the alewives have had a defender in him at Town Meeting, when discussion came up about the amount of money allotted to the Herring Brook. From a naturalist’s point of view, he can hardly be said to have much sentiment in him about these fish as part of the living community. Too many of them would stink the place up, or so he affirms. I remember him at a hearing, speaking to a public official in this wise, “Ever see my brook? Our brook, I mean. No dirty, stinking mess up there!”

So, in his special way, he keeps the area clean, and is the herring’s defender and interpreter. I think he likes to conceive of himself as a kind of rascal. To those who ask him about the fish he is liable to dispense information that is an outrage to the innocent. Two Connecticut schoolteachers were once directed to the run, and came away saying the alewives were often so plentiful that the Cape Codders shingled their houses with them. (This is part of what he has called “My fight with the public.”)

So, a “Cape Cod character,” personification of an old locality ... but I don’t think he would like me to write too well of his character. That day as I lingered at the run he gave me a lowering look. What was I interested in the fish for? Well, if I’d take the information from him, we could make ourselves a pile of money by selling the story to Collier’s magazine.[Pg 17] Did I ever hear about the Indians shooting these fish from the trees?

Facts, Harry. Facts.

“Well, naow, I’ll tell you. With the shore wind blowing on the long flats out there and the water ruffling up like that, the fish don’t come in much. But they’ll be along. Yes-yes.”

So was there nothing to do but take tentative steps and wait? The scene, the place, the weather—an emergent weather in me perhaps—was more compelling than that. The wind blowing, brook roaring, sun shafts through the steely sky, all urged an opening. I walked down to the south side of the road, by the tall lilacs, under high willows and maple trees. Here the waters of the brook divide between the concrete fishway and a side or “waste” stream which rejoins the other some fifty feet farther on, dropping precipitously over rocks that foam with water too high for the migrating fish to leap.

I walked down a path at the edge of this narrow waste stream. Where the water was running swiftly, lithely, between the high rock foundations of the road on one side and a low dirt bank with grass hummocks on the other, I saw the brown head of a muskrat leading across the stream not more than twenty feet away. The sleek, dark little animal swam over to a stone across from me and sat there eating something with quick, legerdemain little gestures, a fast shuttling between its paws and its whiskered face.[Pg 18] Apparently it couldn’t see me. The east wind was blowing across us, and the fresh waters were roaring. Then it stopped and nosed back into the stream, swimming across to a tussock not more than twelve feet from where I stood. It plucked out, quickly, a sizable bunch of grass and swam back with it to the same eating place and chewed it up. Then it returned to the shallow water, swimming close to the bottom, where I could plainly see it going easily against the current with its two hind legs stretched out, propelling it, and the long flat tail acting as a scull.

It emerged to disappear in a few rock crevices and then came out, its glossy, questioning head sniffing for danger before it dropped down again. Finally it swam out of sight into the cruel brilliance of sun-reflecting waters that ran full out, full tilt. Pools of plenty were continually releasing and boiling as if they were the strength and source of all motion.

The muskrat’s eyes were black as rock recesses and its pelt as dark and glistening as a mud bank. It was at home, with all its food around it—grass, minnows, salamanders, fresh-water mussels—in an adaptation, a closeness to the place, arrived at through both random and inevitable forces. It knew its small world and needed no outside instruments to set its course by. I might wonder about the next event, the coming storms, but here was this animal swimming away as if it said, “Come on in. The universal water’s fine.”—in a stream as yet too cold for me.

[Pgs 19-20]

[Pg 21]

A week or so later, early in April, I finally saw my first alewife of the season. It had the brook to itself where I caught sight of it—a cloudy form running upcurrent—and when I went closer I could see it probing the rippling, beating waters, with all that fish articulation of separate fins together, fanning slightly, waving, threading, and steering, the fixed eyes staring on, its whole body weaving with the flow. It is a surprisingly large fish, seen for the first time in a narrow stream. Its length may be anywhere between ten and thirteen inches, and it has a heavy look for those who are used to sunfish and minnows.

An alewife was no novelty to me, but this one seemed to decide the year’s direction. It started things out. I saw it for the first time, as child or genius does who finds some whole deep image in the air, or radiant clarity in the water. I had the feeling too that I was looking at a professional from an old water world, a new agent of old assurance, deserving profound respect. After all, it had been coming back here thousands of years before me, in the migrant history of[Pg 22] its race, and by this time must have mastered its passage. And as a natural event, a part of the spring’s development, it seemed to announce that bud scales on shrubs and trees would start to crack and fall away to let the inner shoots out that unfold as leaves and feed on the sun. It said that flies and wasps and spiders would come out of winter hiding and sleeping, that the song sparrows would begin to sing in the willows and viburnum bushes along the banks of Stony Brook.

There is something exciting and strange about the sudden appearance of new life in the spring, coming from another region, another climate. The terns or plovers that appear along the shore bring an unknown experience with them. They seem to start in or to assemble according to some tremendous demand which is in no way restricted to seasonal lags. They recur; they are recognizable; and yet they bring in endless tides and vivid journeys, being a part of that remarkable projection of nature in which a multitude of lives use their skill in navigation, their plumage, their scales, fins, and various senses, their particular drives toward fulfillment.

Migration is universal. That which prompts animals to emerge from their burrows, or to start moving over the ocean floor, to fly north, to swim into brackish or fresh water from salt, or even, like a ladybird beetle, to move a short distance from a forest floor to a meadow, must have a world-wide energy to it, with[Pg 23] lines of communication that reach everywhere ahead and invite the human drive for knowledge. But in a strict sense there are two accepted definitions of migration for the animals. There is return migration, of which the alewives provide an example. Fish or birds in this category travel seasonally from one area to another, usually coming back to some home region after varying lapses of time. Otherwise, there is emigration, in which animals leave their home base but never come back again, lemmings and locusts being good examples. Both definitions, I should think, can prove that home stretches farther than we know.

Why had this pioneer of an alewife, and the others that had come before it, arrived so soon? It is possible that they had migrated up Stony Brook before. All mature alewives—a majority seem to be four years old—are moved by sexual development and swim inshore when the temperature of the fresh or brackish water has turned warmer than the salt water from whence they came. The earliest comers often appear to be larger in size. This suggests, at least, that they may be older and that they have spawned in that run before. The latest to come seem to be the smallest, and therefore the youngest. Alewives, like other fish, seem to have a tendency to keep growing, though there may be a maximum size reached in their fifth or sixth year. The only conclusive way to tell their age is by microscopic examination of their scales,[Pg 24] which reflect each spawning year and its physical changes.

Work done by Keith Havey on alewives in Maine shows a minimum of alewives spawning at three years of age and the largest number in the four- or five-year-old range. No scales were found which reflected more than two spawnings. As to size, he gives a sampling of their length in inches which graduates up from 11.25 inches in the three-year-old fish to 11.80 in the four-year-olds, 12.35 in five-year-olds, and 12.80 in the six. The female alewife, incidentally, is a little larger than the male.

Possibly then, these early alewives at Stony Brook were the oldest, and because of that they might have been the most practiced at finding their way. I am told that, with new fish ladders, observers have noticed the earliest arrivals seeking and passing through them more readily on the second year after construction than on the first, which leads to the belief that they have been through before. Age may improve the alewife in prowess, though it is a fish of crowds, and not one to strike out much on its own. The “homing instinct,” still unfathomed, but about which I will try to say more later on, brings them back to their streams of origin with almost united force.

So my lone alewife marked the greatness it preceded, though it was early, in early and still undecided weather. At first the sleet, hail, flurries of wet snow came in profusion, stabbing between the sunshine,[Pg 25] as though nature, before making its next terms known, was full of passionate unease. Then wings of warm rain would beat in over the Cape, to slash and curve and follow along trees and houses, through inland ponds, across the ridges and hollows, and the wind poured behind in great gusts, trying, it seemed, to shake a tight world loose. Underneath the struggling air many things waited for more chances in the sun, but under the stars, on foggy evenings or bright days, the singing of peepers in pools, ponds, or boggy land would swell and widen everywhere.

Then as the month kept advancing, that which came out began to stay, and to expand, in variety, flexibility, and strength. The wheels of the world seemed to turn more brightly. I felt a suggestion in each changing tree, in the loosening ground, the kinetic light and air, of new unfoldings, kaleidoscopic discoveries. The formality, and power in the coming on of spring surprised me, as if it had never come before.

More winds began to blow from the southwest, the prevailing wind during late spring and summer. Yellow fingertips of bloom showed on the whip-long branches of the forsythias. The temperature edged toward the fifties, and there were deep new meetings between the moles and the worms. One day many tree swallows began to flit and dive low around the Herring Run. They skimmed along the surface of the water, then sailed up again. Their bellies were as[Pg 26] white as a frog’s or horned pout’s, dark wings and tails trimly cut, backs almost a tropical blue in the light above the water, reflecting green at some angles, or a green-blue-purple the color of mackerel. Their flight dipped with the up and down flying insects they were chasing. When some insect, unseen to me, spiraled straight up along the banks, a swallow would leave its water gliding, twist suddenly, beating its wings, and almost spiral after.

That original source of energy the sun, which men might still worship in good faith, was bringing out new facets to shine abroad. The web of life was stretching to its light. Birds, insects, plants, and fish were beginning to move to its changing measure; though if some days were warm with a budding, fringing, easing expectation, others were still raw, wet, and contracting, bringing winter back to flesh and fiber. We kept looking for the alewives. Cars would slow up at the Herring Run. The drivers peered down to see the curving, dark forms of a few fish holding up against the current. Then they drove on. Or they got out, saw nothing, and went away in disappointment. But suddenly one morning toward the middle of April the crowd of alewives had so increased as to cause an inescapable excitement in the vicinity. The water was thick with fish, their fins showing on the surface. It was almost as it had been a hundred years before when the whole population would cry out at their coming, “The herring are running!”

[Pgs 27-28]

[Pg 29]

“The herring are running!” must have been a great cry once, for men, women, and children over the whole Cape. There was a deep meaning in this seasonal event, since the fish were a part of the local livelihood the year around. Nowadays, so far as commerce is concerned, the alewives lack their former importance. In Massachusetts, although they come into a number of streams and rivers few alewives are taken for the market. I understand that in recent years only the runs at Brewster and Middleboro have been open for commercial use, the fishing rights having been sold to the highest bidder.

For all that, it still seems a live, high, and social morning when you wake to the gabbling of gulls in the distance and know that the alewives have finally arrived. The sun spreads down new warmth. There are cool sweeps of breeze, broad runs of blue in sky and sea past the gray and white houses, with those silver hordes starting to enter inland veins in a bold reminder of perpetuity.

This season the rights to fish the stream had been[Pg 30] bought from the town by a firm that wanted them for lobster bait. On the eighteenth day of the month a big red truck had pulled alongside the seining pool and the old mill. Three men were down in the pool, with their rubber boots on, putting a wide net in place. It was rimmed with cork floats and roped at the center to a hoist fixed to a small dock on the bank. A little wire gate was closed at the stream entrance on the upper side of the pool, so that the fish could go no farther. The run was officially on; and until it thinned out two months ahead, the fish would be hauled from the pool four days a week, thrown into barrels, and trucked away to be sold as lobster bait.

A sign was posted at Stony Brook, reading: “No herring may be taken or molested in Stony Brook on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays in accordance with state law. Residents of Brewster are entitled without charge to one dozen herring daily on Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays during the open season, and should obtain them from J. B. Salvadore, Jr., who has purchased the Herring Fishery Rights for this year, or may take them from the brook on these days if he is not present.” It was signed by the selectmen of the town of Brewster.

On the down side of the road a bunch of children were celebrating the coming of the fish. The alewives, crowding, resting, circling, and slipping up through the pools and falls of the fishway—their bodies a fretted-lavender brown in the bubbling waters—were[Pg 31] now fair game for the inland world they had come back to. Three boys were competing for a crab net they were dipping into the water, scooping after the fish, and as often as not heaving it up empty. One of them was professionally pinching the belly sides of a fat, gleaming alewife to see if it was a female and would emit some of its roe. Then he flung it back into the water with furious energy; and it slapped hard when it hit, and he cheered.

Were they under the law, these predators? Well, this play, or hunt, this spring jubilation had been going on for several hundred years.

“Let the kids play around there, I say,” said Herring Harry. “We were kids too. We didn’t start out old.”

In barer, colder, perhaps simpler days, days when men lived closer to their natural surroundings and were more dependent on them than they think they are now, the alewives meant food and revenue, an abundance returning to your own back yard. They came under the heading of useful acquaintances. But now the roe, or fish eggs, is the only part of the alewife that is highly considered locally. It is a very bony fish and most people reject the idea of eating it, forgetting the days of “good salt herring” when the children ate them on sticks like candy. So the Brewster resident gets his allotment for the roe, to be fried in butter. An ambitious gardener can bury the rest under his corn plantings to serve as fertilizer, if the cats[Pg 32] permit, though it is still a very good way to make corn grow tall in unreceptive soil. A hundred years ago or more, when it was done extensively, it resulted in rich yields. I have heard that one acre set with a thousand fish would produce three times as much corn as an acre without them. It is a practice that we inherit from the Indians, although the Indian agriculturist was likely to be plagued by wolves instead of cats.

Cape Codders, even so comparatively short a time ago as fifty or sixty years, would not have liked to hear this farming method belittled. Some of them may even have regarded it with delight. I recently talked with a man who was a boy in the 1890’s and remembers walking behind a wagonload of “very dead” fish in a field made ready for corn. A man in the wagon pitched out a forkful of herring into each prepared hole as they creaked along, while another, walking behind, shoved dirt over them and planted the seed. He can remember a relative cocking a keen ear one night and saying, “Listen! You can hear it growing. By God, when their feet hit that stinking mess don’t they start up and go!”

Although to know them may have been to understand their worth, I find one early writer, Marshall McDonald Douglass, in his North America, 1740, who does not give the tribe much credit. “Alewives,” he says, “by some of the country people are called Herrings. They are of the Herring tribe but much larger than the true Herring. They are a very mean,[Pg 33] dry and insipid fish. Some of them are cured in the manner of white Herrings and sent to the sugar islands for the slaves, but because of their bad quality they are not in request: in some places they are used to manure the land. They are very plenty, and come up the rivers and brooks into ponds in the spring.” None the less, they used to be smoked or pickled in brine and shipped out in barrels to the West Indies, and whether or not the quality was bad the demand was enough to make the trade in them into one of great volume, part in fact of the famous swap for molasses, later turned into New England rum, which was so important in our early history.

Before I try to defend these fish against any further imputations, I should explain their name. “Herrin’” is the name and pronunciation on Cape Cod. I don’t call them alewives just to defy such Cape Codders as might be fussy about it, but to differentiate them from their more famous cousins the sea herring, which spawn in salt water. Cape Cod has its alewives committees, and it may be that the fish were called alewives here before they were called herrin’.

You can still read statements to the effect that the original name “alewife” is a corruption of the Indian word “aloofe,” which meant bony fish. In 1871 a gentleman named J. Hammond Trumbull tried to scotch this bit of etymology by pointing out—in a government publication on Sea Fisheries, that the Narragansett and Massachusetts Indians called the[Pg 34] alewife and herring “Aumsu-og,” as had been noted by Roger Williams. In any case, whichever Indianism we choose, it seems more likely that the name stemmed from English dialect. “Allizes,” not at all like aloofe, was one of the names applied to it in company with the allice shad. To quote Mr. Trumbull again: “The modern English ‘allis’ was in old French and old English ‘alouze’ or ‘aloose,’ nearer than the modern form of the name to the Latin ‘alausa.’” The latest in this chain of spellings is of course Alosa, the scientific handle now applied to the shad, and in some texts to the alewife.

To the English colonists an alewife was also an alehouse keeper. A Dictionary of Americanisms quotes a volume printed in 1675 which said: “The alewife is like a herrin’, but it has a bigger bellie, therefore called an alewife.” (Let that quotation be of some comfort to the proponents of herrin’. The name has a formal heritage.) The writer was surely not making a direct physical analogy between a woman and a fish. The original alewife he probably has reference to is a shad, but Pomolobus pseudoharengus does have a deep body and is heavily built forward, so perhaps a comparison with a hearty alewife of sixteenth- or seventeenth-century England would not be too far-fetched.

The poet Skelton described an alewife, Eleanor Rummying by name, who lived in the time of Henry VIII. She brewed a “hoppy ale,” and “her face was[Pg 35] wondrously wrinkled, lyke a rost pigges eare bristled with here”—at which point I will let the analogy go on its merry way.

The alewife has had a variety of local and common names, the kind that indicate touch and sight, the handing on of natural meetings—the signposts of its contacts with man and his history on the eastern shores of this continent. It is known as “sawbelly,” for example, referring to the fine sharp little notches or teeth on the midline of its belly; and for the large eyes, set on each side of its small head, it has been called “wall-eyed herring,” “big-eyed herring,” or “blear-eyed herring.” It is also the “spring herring,” “branch herring,” “river herring,” or “fresh-water herring.”

This old New England name of alewife has its modifications in “Ellwife” and “Ellwhop” on the Connecticut River, and there were variant pronunciations in other regions. In the state of Rhode Island alewives were called “buckies” and in Maine “cat-thrashers.” In Canada the name is “Gaspereau,” sometimes “Gasparot.” The term “alewife” is uncommon in the maritime provinces. There seem to be three Gaspereau Rivers, two in New Brunswick and one in Nova Scotia, in addition to a town of that name in New Brunswick, and a lake in Nova Scotia. Apparently the place name derives from the fish, and not the other way around. In its 15th Report, for 1917, the Geographic Board of Canada says “after a fish,”[Pg 36] in explaining the name of the Gaspereau River. Another Canadian term for alewife is “kyak” or “kyack,” which sounds like a derivation from northern Indians. Mr. A. H. Leim of the Biological Station at St. Andrews, New Brunswick, writes me that he has only heard “one or two fishermen call them ‘kyacks’; one of these was an old poacher on the Shubenacadie River in Nova Scotia who always used this name. I assume the word is of Indian origin.”

Finally the alewife is called “grayback,” a name that distinguishes it from a close relative often confused with it, which is called the “blackback,” “blueback,” or “glut herring” (Pomolobus aestivalis). The blueback shows up in a late spring run, and seems to spawn in the lower reaches of a stream, instead of migrating up to its headwaters. It has smaller eyes than the “grayback” and as its name indicates its back is dark blue, instead of greenish gray, but as colors fade at death, this is no sure test. The two species of alewife can only be told apart conclusively by dissection. The lining of the blueback’s body cavity is black instead of pink or gray.

These names are also indicative of the range of the alewife, all the way from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Carolinas. In the spawning season they come inland by way of sandy inlets, great tidal bays, fresh-water river mouths, or creeks only a few yards wide. Most of the streams by which they are still able to swim up have their local history of fishing alewives,[Pg 37] either with traps, weirs, dip nets, or even pails. In the fisheries of Maine it is known as “alewife dipping.” This is an important “food fish,” even though it may never have approached the sea herring in numbers, nor been as famous as the cod.

If the English sailor, Captain Bartholomew Gosnold, had been ashore in the springtime instead of on his ship when he gave the Cape its name, it might now be called Cape Alewife.

Though they are only part of a multitude of other lives that nurtured the American past, the alewives should be given high and special credit. William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation testifies to their vital importance in the Pilgrims’ first year. After the Mayflower left in early April of 1621, Squanto, that greatly helpful Indian, showed them “that in the middle of April they should have store enough come up the brook by which they began to build, and taught them how to take it, and where to get other provisions necessary for them.” This brook ran, as it still runs, through the town, so that the Plymouth inhabitants were lucky to have their supply of alewives close at hand—they seemed to have depended on them primarily for plantings, also taught them by Squanto. The fish came in “fat and fair” and amazingly plentiful after a lean winter full of apprehension. At first apparently each inhabitant took freely of the fish in the brook, but this seems to have resulted in “injuring the property of those near the place of[Pg 38] taking.” As a result the Town Brook became town responsibility after a few years, and the fishing was regulated. The cost of a weir was distributed among the inhabitants and the fishing put under the charge of town officers, with fines set for taking alewives without permission. Innumerable fish laws were passed after that, from the Colony of Plymouth to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The fish ran comparatively free for a while, but through the progression of these laws you might watch, in town after town, the gradual growth of human population plus human concern for a valuable product. In 1709 a general law provides: “That no wears, hedges, fishgarths, stakes, kiddles, or other disturbance or encumbrance shall be set, erected or made, on or across any river, to the stopping, obstructing, or straitning of the natural or usual course and passage of the fish in their seasons, or spring of the year, without the approbation and allowance first had and obtained from the general sessions of the peace in the same county....” An Act of 1741, to “prevent the destruction of the fish called alewives, and other fish,” might indicate that the colonists were beginning to notice a decline in their numbers and to be apprehensive about it, although it is hard to judge. A History of Barnstable County, published in 1890, has this to say: “Early in the last century the supply of herring so far exceeded the demand for fish food that the surplus was used to fertilize the fields, and the growing[Pg 39] custom of using them in each hill of planted corn was checked in 1718, the town fathers [of Bourne] ordering that none should be taken in the future to ‘fish corn.’”

Apparently the alewife population did start to decrease a long time ago. Fishermen along the Merrimack River noticed a diminishing in numbers as early as the mid-eighteenth century; and somewhat later they thought it might be due to the number of small ponds which had been dammed up. These ponds had access to the river and so provided spawning grounds. Certainly the alewives, through man’s agency, began to suffer great setbacks in the old use of their runs. Some of the first culprits were the woolen mills, and corn or grist mills such as the one at Brewster—they blocked up many of the runs, in spite of the fish laws. Then a tremendous industrial expansion put cities and factories along all big rivers and many large streams, adding more mill dams across the runs. The resulting sewage and manufacturing wastes polluted the waters, destroying many fish, and making some rivers completely unfit for migration. Extensive deforestation also resulted in the drying up of a number of streams and the lowering of water levels. The nineteenth century was a notorious plunderer.

Alewives in any large number now coincide with undeveloped areas, which happen to be comparatively few along the Atlantic coast. As a result of industrialization the original heavy runs were so[Pg 40] reduced that the only important, commercial runs are now in the southern part of the alewife range, notably the Chesapeake, or north of Rhode Island. Although the fish still have much less access to their ancient, natural routes, the existing runs are probably less carelessly protected by law. State laws put the responsibility of keeping the fishways clear on the localities through which they run, but the state supervises their condition, and if a run is too depleted the state can forbid the sale of its fishing rights. Whatever may be said about their decline in the long run, it is quite likely that state supervision has helped to increase the alewife population during comparatively recent years. It certainly seems to be true that the number of fish at the Brewster run has increased since the fish ladders were built in 1945. The new fishways made the rocky, often clogged stream easier of access, and cut down on fish mortality as they ascended. They can, in other words, be brought back; although there are fishermen in Maine who estimate that the alewife population is only a third as large as it was some fifty years ago, and there are those who say the decline has been even greater in Massachusetts.

A great many of the old alewife fisheries lost their vitality because there was no longer any local dependence on them nor any general call for the product. A recent article in the Maine Coast Fishermen said this: “A few weeks ago in Wareham, Mass., the local selectmen refused to auction off the fishing[Pg 41] rights, feeling the bids were too low. An old timer of the town, who has watched these migrations since he was a boy, recalled that the alewife rights to the stream in question once brought as much as $12,000 a year.” In the smaller run at Brewster, incidentally, the bid taken during the last spawning season was $450.

Control is still local. Where there are still good-sized runs, the towns appoint alewives committees, whose members are re-elected annually at Town Meeting. In Brewster, on a salary of some twenty-five dollars a year, plus small wages for time spent, it is their job to keep the Herring Run area neat; to post regulations; see that no individual gets away with more than his allotted portion of fish; and keep the stream free from obstruction so that the fish can proceed to their spawning grounds, as well as into the nets of the concessionaire. The town sells annual rights for the privilege of fishing the stream in season, four days a week. On the other days the alewives are allowed to go ahead and propagate their kind. The five hundred barrels or more of fish that have been taken yearly from Stony Brook happen to have been used recently for lobster bait.

To some extent, incidentally, their use and commercial value depends on their condition and flavor. An alewife’s flesh is best when it has been taken directly out of salt water. The ocean flavor is progressively lost as the fish migrates through inland streams.[Pg 42] So they have their highest value where the runs are located close to the sea, or tidal rivers such as the one at Damariscotta, Maine.

The West Indies trade is over, as well as the days of “good salt herring.” The most likely place to see indications of alewife now is on the stupendously bountiful shelves of a chain store, in the form of a can with a picture of a cat on it. And the future of the alewife, in human hands at least, seems to depend on a wider demand for it. It is valued neither for sport nor edibility, but is used for cat and dog food, fish meal, and pickled fish, with some, as at Brewster, being taken for lobster bait. Apparently there is an innate prejudice among some New Englanders against using a traditional food fish for other purposes, and a belief that selling it for meal or cat food is less profitable. Put this down to thrift, or respect for old ways, still it stands against the fact that the alewife’s latest value comes from its status as a processed, rather than edible, food. “Reduction” is what they call it when the alewives are turned into fish meal, and in a sense perhaps they have been reduced, at least in our personal esteem. They now belong to a technical age with the rest of us.

With modern methods of handling, packing, and transportation the old fisheries may have been left behind, but it should be said that, because of its new status in commerce, ignominious or not, the alewife may stand a better chance. The State of Maine, for[Pg 43] example, has been undertaking thorough study of the alewives in order to find out how old runs can be brought back, or new ones created. They are a fish that are very responsive to management. When barriers are removed and open fishways are made, they take their opportunity.

All is not well with the traditional ways, though the alewives may be perfectly ready to go beyond them. In the old days on Cape Cod there was hardly a seafaring man who did not take his salt herring aboard with him, and on land, after being salted, dried in the sun, and smoked, they were strung on sticks and sold for ten cents a stick. There were many smokehouses on the Cape, and in the wintertime dried fish hung on the barn rafters above the haylofts. I have a comment on those days from Mr. Alexander: “None of your First National Stores then,” said he. “We lived off the earth ... potatoes and smoked herrin’. That’s why some of us old goats lived so long.”

It is hard to find smoked herring these days. It is a skill that seems to have almost gone; and I am told that there used to be a good deal of variation in the product. Smoked fish are now easier to find in Maine than on Cape Cod. I bought a pair recently in a small general store in Maine at the excessive price of fifteen cents. A dried alewife was handsomer than I had suspected, and the smell not unpleasant, although I might not say as much for a barnful. The head and eye sockets were encrusted with salt, and the hard[Pg 44] thin body was colored a bronze and smoky gold as though heat still roamed the scales. I was reminded for some reason of a metal bowl I had once seen that came from the land of the Incas. I peeled off the scales and chawed a toast to our ancestors.

[Pgs 45-46]

[Pg 47]

The fishing operation near the old grist mill was in full swing after the twenty-third of April. The Salvadore crew was hauling in their net with the aid of a winch. It was loaded with fish, enough to fill four or five barrels. The victims were flipping and flashing with a whirring violence, a high sound going up in the gray morning air, a beautiful iridescence in their white-silver sides. The whole dripping net was heavy and alive with their shivering, thrashing, and dying. Heads butted through the mesh and gills caught, in their frantic, vibrating despair ... and all for lobster bait, worth six dollars a barrel.

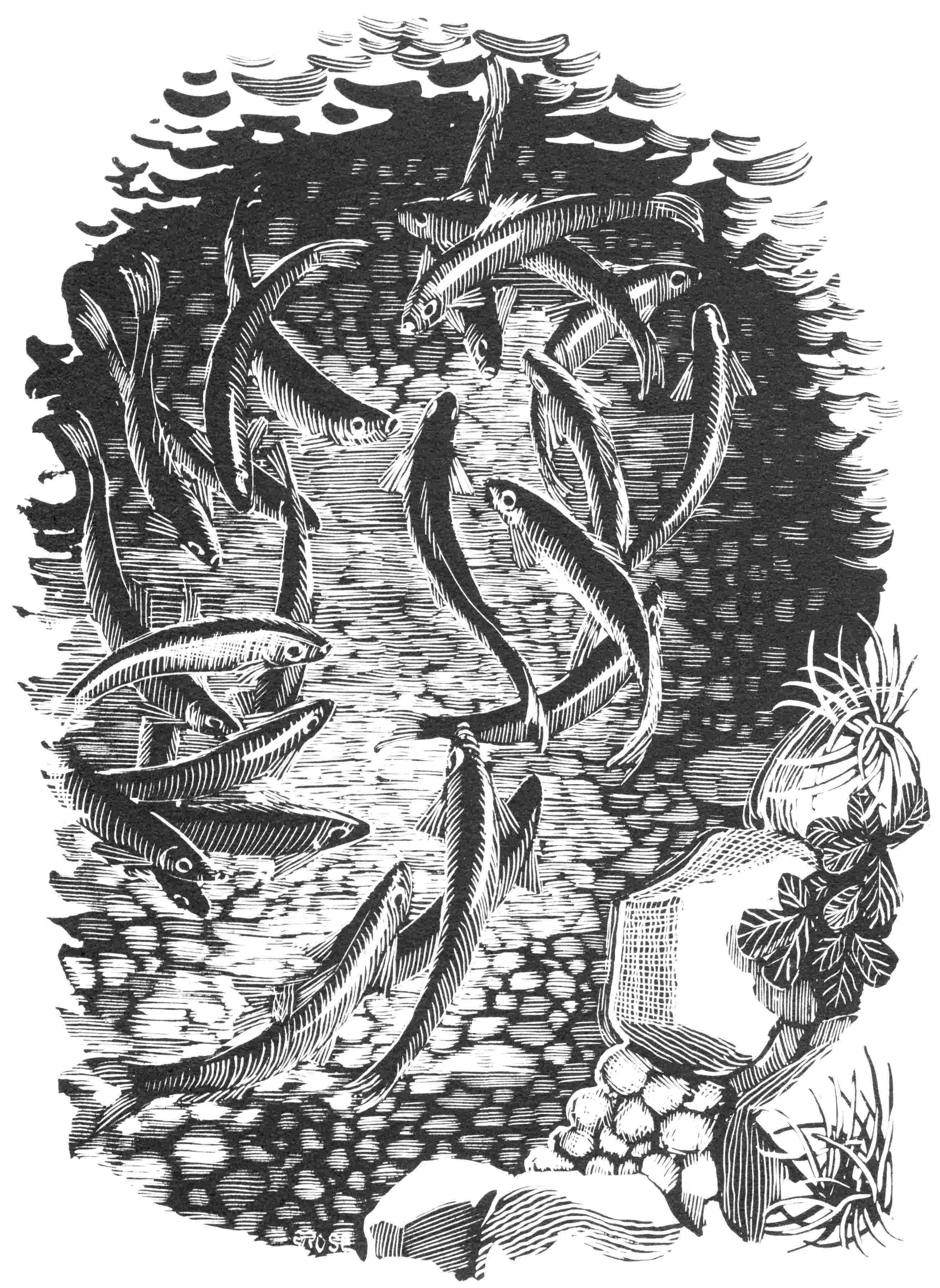

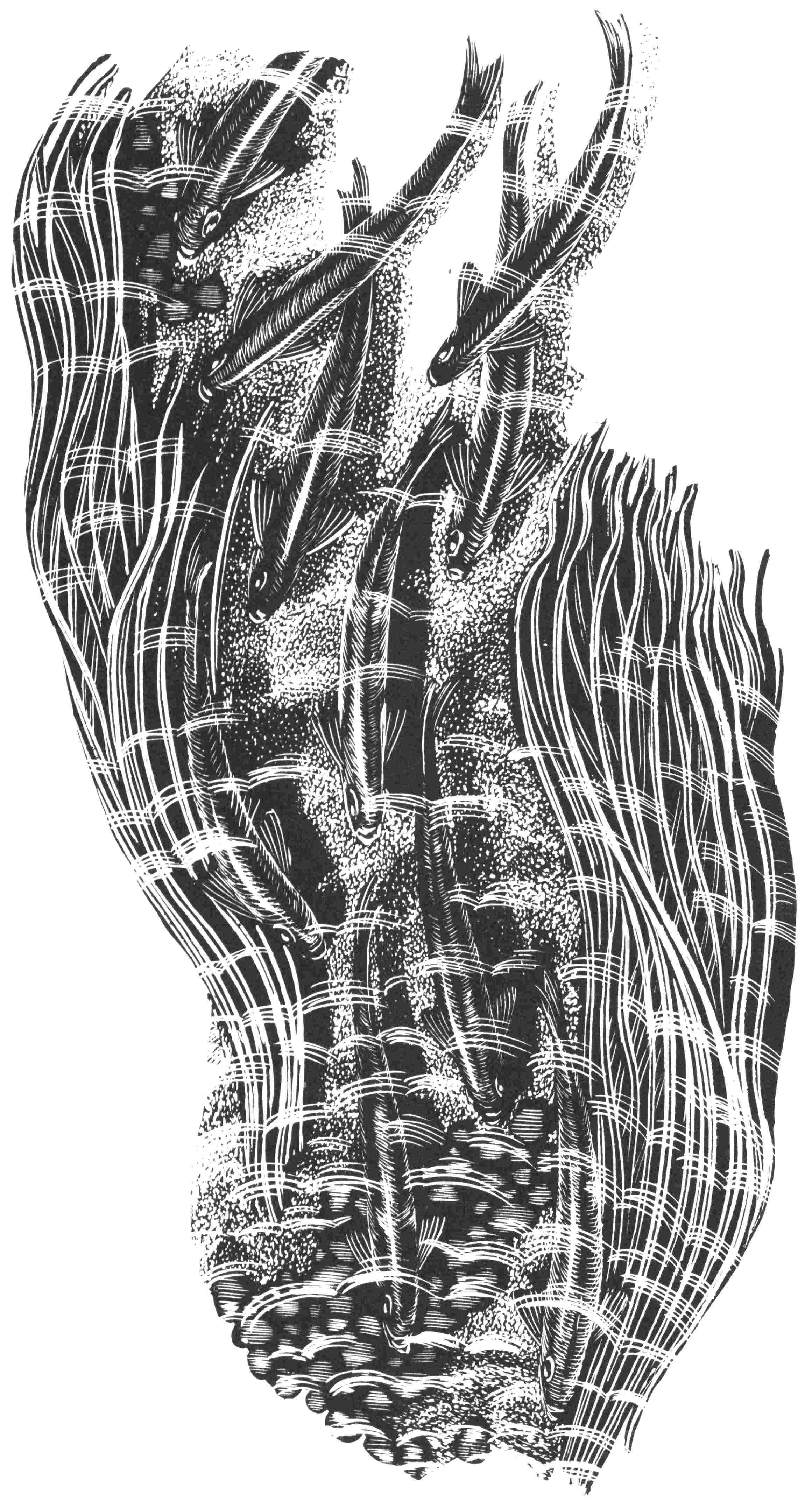

The early colonists spoke of alewives coming up their streams in “incredible” numbers, and so it still looks, though Stony Brook, for one, is narrow in its upper reaches, and when the fish are forced into it they are crowded beyond all proportion. The inland stream, with its fresh-water grasses, insects, and small fish is suddenly host to a large and almost foreign form of life, except that they are both closely joined to the sea.

[Pg 48]

On the whole, it had been a rainy month. The brook below the seining pool was roaring and foaming down. Such was the teeming crowd of alewives trying to swim up through the ladder, through the violently heavy flow, that there was a constant falling back, a silver slapping and flapping over the concrete rims of the pools. Farther down, where the waste stream tumbled over a small mountain of rocks, too high for the fish to jump (their limit, on a vertical leap, seems to be not much over two feet), there was a scene to force the heart. Always a certain number of fish, dividing from those that swam the main stream toward the ladder, would attempt the impossible at this place. Ordinarily, when an alewife meets obstacles in its advance upcurrent it will quickly go forward into it, then leap in short dashes over rocks and the lip of fishways. I had seen them go up without apparent rest where the stream falls down the inclined ladder at the pond outlet above. They were dancing and flipping up those waters, which were rushing and bubbling down, like kites in a fast wind.

Yet here, for all their instinctive valiance, was the unsurmountable. Now, as they had done for thousands of years, they tried and failed. White tons of water smashed down over the rocks, but time and time again one fish after another made a quick dash into it and almost flew, hanging with vibrant velocity in the torrent until it was flung back. Many were exhausted and found their way back to the main[Pg 49] stream, circling and swimming slowly, and a large number were smashed against the rocks to turn belly up and die, eaten later by young eels, or gulls and herons, as they were taken downstream by the current. Some were wedged in the rocks and could be seen there for days as the water gradually tore them apart until they were nothing but white shreds of skin.

A wooden bridge crosses over Stony Brook at this point. A neighbor of mine, a mother of children, was standing there watching when I came up, and I heard her say, “Terrible!” I guessed that she knew what she saw, besides death and defeat. It was the drive to be, a common and terrible sending out, to which men are also bound in helplessness.

We are astonished by this fantastic drive. “What is the point? What makes them take these suicidal chances? Why?” It is as if we were trying to get back, or down, to an explanation in ourselves that we had lost sight of. But somewhere in us, through this feverish, undecided world, we still know.

Are they stupid? There is no measure in the world of nature more excellent than a fish. It may be comparatively low in the evolutionary scale of complexity, but no animal is more finely made, or better suited to its own medium. All the same, the unvaried blindness their action seemed to show would sometimes strike me as hard as did their ability in the water.

Stony Brook was black with them. There was no[Pg 50] open patch of stream bed to be seen. And with the excessive crowding, the general procession, so steadily insistent on its own time, was hurried up to some extent. Their motion became almost ponderous and tense, while individual fish leaped like dolphins, pewter- and gold-sided, over and through the dark herd. Others circled in and out or kept pace with the rest, staring ahead.

They had a synchronized momentum of their own. If I dropped a stone in the middle of them, they would separate at that point and then close in to fill the gap. There could be no nullifying or breaking their united persistence. Their onwardness, their desperate dashing against the rocks, had its own logic—a logic which had nothing to do with hope, reason, or choosing another alternative. No way out, in other words. Slavery to the reproductive urge. These alewives are more dumb than sheep. If you were to press your own sympathy hard enough, you might feel a terrible lack of variety in them, or, paradoxically enough, of daring. The lidless-eyed and plunging multitude seems brutally driven, without a chance. This is “togetherness” with a terrible vengeance.

Perhaps there is something here that we know too, as fellow animals, and lose sight of. At the risk of making one of those vaguely anthropomorphic assumptions against which the objective scientists are constantly warning us, I would guess that the self-motivation in this onward mass of fish might be[Pg 51] compared to those human crowds that take action under stress, independently of the individuals that make them up. Suddenly a crowd, hitherto a random combination of people, takes on a frightening rhythm and purpose of its own. It is governed by laws which go back infinitely farther in the history of life than the immediate goal of its anger or exultation.

I have explained nothing. I can only say that when I first saw these fish I was moved in spite of myself. Instinct is no more blind than wonder. To have the human attributes of mind and spirit and the race’s ability to control its own environment does not give me the wit to beat the infinitely various will of life at its own game. All I could wish for would be to join it.

I walked on down the banks of Stony Brook, past the Herring Run area with its neat paths, bridges, and fish ladders, my shoes squashing in the mud. The stream turns a slight angle at this point, gets broader and shallower and begins to run through the little valley that ends in tidal marshes and the Bay. The alewives, for a hundred yards at least, were running up against the downward currents, massed almost stationary, not in ranks, but ordered mutuality, with a long waving like water grasses or kelp, and curving, twisting, swirling like their medium the water as they moved very gradually ahead. There was no indiscriminate rushing ahead. It was done to measure; but it seemed to me that through their unalterable[Pg 52] persistence I saw the heaving of crowds of all kinds, of buffalo, cattle, sheep, or men. I had seen as much motion in crowds pouring out of a subway entrance or massing through a square. History was in their coming on, without its shouts and cheers. They could not speak for themselves; but who knew how deep the silence went?

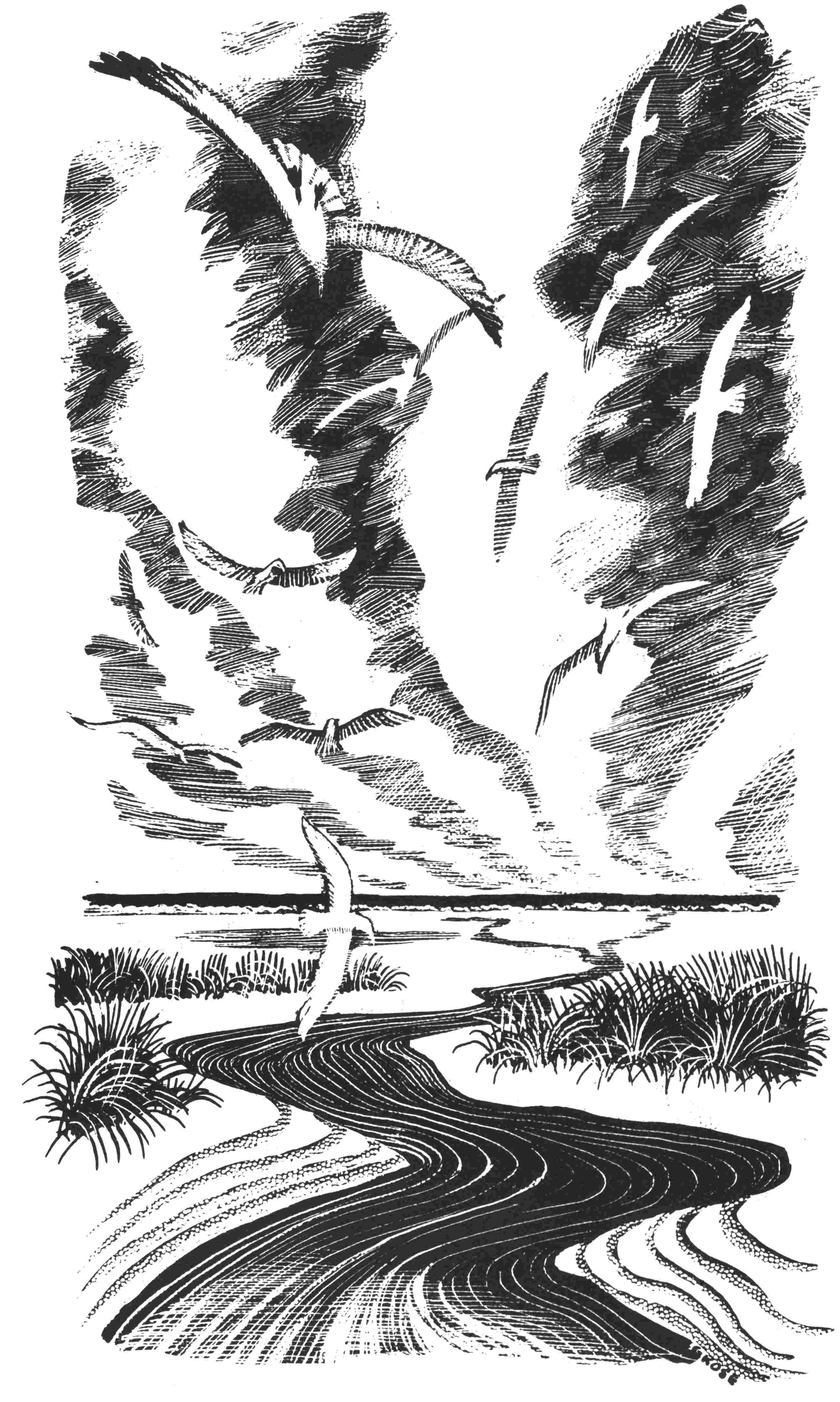

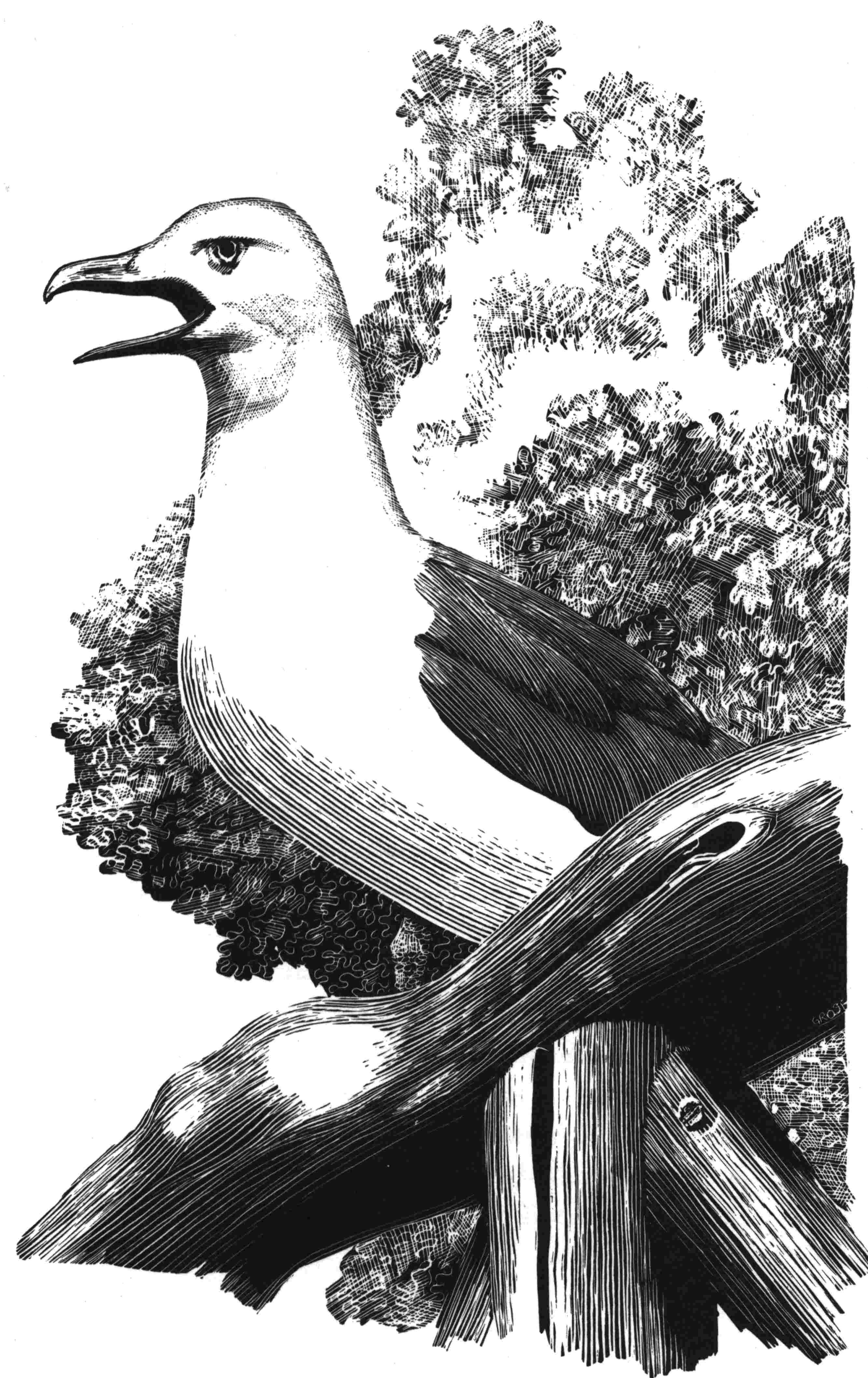

Ahead of them there was a net; behind, down the broader reaches of the brook, the greedy herring gulls dropped down into the water after them, or stood along the bank in apparently glutted satisfaction, while others screamed and sailed overhead. In spite of their slow gliders’ grace and local lethargy compared with swift sea birds like the terns, gulls travel the rims of the world. They had always made me think of far-distance, voyages unending. Many of them had congregated on a bald hill that overlooks the run and were standing like white sentries under the shafts of the northern sky beyond. From far off they sometimes suggest rows of military crosses, and I have heard them compared to a field of flowers. Soldiers, flowers, graves ... all these they might suggest on the heights of fate, by their pure bold greed and unmatched design. They stood on a wide stage.

[Pgs 53-54]

[Pg 55]

The fish kept moving up. I watched them swinging back and forth with the current, great-eyed, sinewy, probing, weaving, their dorsal fins cutting the surface, their ventral fins fanning, their tails flipping and sculling. In the thick, interbalanced crowd there would suddenly be a scattered dashing, coming as quickly as cat’s-paws flicking the summer seas. They may have moved by “reflex” rather than conscious thought, but what marvelous professionals they were in that!

The cold raw winds of April had heeled back, and May swung on. There were an increasing number of days with the wind from the southwest, smelling of sunny springtime. The local paper had it that the temperature averaged a high of 66.6 degrees Fahrenheit and a low of 44.2 in the week between the second and the ninth of May. The following week the average rose a little, going to between 67.5 and 47 degrees. The first reported striped bass, a three-and-a-half-pounder, was caught on the Cape the eighth of the month.

[Pg 56]

The willows that hung over the Herring Run were budding and flowering out, lacing and fringing with many beads, a yellow-green; and leaves of the red maples began to unfold, a light coppery russet color, hanging like limp claws—and elsewhere, on higher ridges and other roads, the oaks in their leafy variety of pink, yellow, gray and pale green, were starting their fires with tenderness. Clouds of the shad-blow’s lacy white blossoms came out everywhere between pitch pines and oaks, to last only a few days and be replaced by beach plums whose flowers burst out of their sheaths like popping corn.

The procession, down the brook and around its bend, made other rushing sounds above the noise of the flow itself. The gulls in the valley were crying out with “ho!” and “ha!” and “yi!” The shadow of a gull flying high over us fell across the water and the alewives rushed to the side. The backs of some of them were cruelly gashed. There was a dead one on the bank, stiff and dry, flatly reflecting the blue in the sky like an unpolished knife blade.

They were close-packed going up through the ladders, herding, slipping, slanting, struggling in relation to each other. I grabbed one out with my hands. It shuddered, was almost still for a second or two, like a man with his wind knocked out, then plunged in my hands and slipped out onto the bank. It thrashed there in the grass, a twelve-inch fish, with a gray-green back, and silver sides and belly that[Pg 57] reflected the magnificent surfaces of May, with grass, sun, and blue sky intruding through the overhanging leaves and the brown earth. It shone with violet, yellow-green, white and brown, pink and blue. It had an inclusive majesty, a great natural art.

Its silver scales are large, like iridescent reflecting coins: and in the water the alewife is able to alter the pigmentation of its skin so as to blend with the background. It is able to do this very quickly, so that it changes in color as it moves up the stream to correspond with a darker or lighter bottom ... part of the whole various pattern of adaptation which the fish show to the water around them.

During the course of evolution brain development among the fishes has been slow. What brain power they have is closely related to their sense organs, concentrated on their whole bodily co-ordination; in which, so far as water action is concerned, they are man’s superiors. An alewife’s body is marvelously fitted to situation—peace or turbulence, light or dark, flood and ebb, ripple or rile. This inhabitant of the sea weaves up through the overhanging springtime, and seems a part of it, experienced as to its flowering.

For it is a salt-water fish, as I sometimes had to remind myself later between the ponds and the Bay, although there is a landlocked variety; and as such it is part of a prodigious tribe. As a member of the herring family—the Clupeidae, it is related to the sea herring, sprats, shads, pilchards, and menhadens. The[Pg 58] sea herring is one of the most important food fish in the world. In Europe whole societies were affected by its shifts in abundance. Loss of control over herring fisheries was instrumental in the breakup of the Hanseatic League. In 1881 Thomas Henry Huxley said: “Man, in fact, is but one of a vast co-operative society of herring catchers.” The yearly catch is enormous. One school of herring may run not into millions but billions of individual fish; though Huxley may have exaggerated the capacity of the herring population to keep its level in the face of human demands.

To mention another important relative of the alewife, the common or American shad is also a food fish, being something of a delicacy, prized highly for its flesh and roe. It is a larger fish, weighing between six and nine pounds; but it is not so abundant as the alewife.

The menhaden fishery is the largest in the country in terms of weight. Some 800,000,000 pounds of this fish are harvested annually from the Atlantic and Gulf coasts; its present fate is to be turned into fish meal, scrap, and oil. In addition many tons of ground-up menhaden, or “pogies,” are used by salt-water anglers to attract bluefish, tuna, or mackerel.

All these herring species are similar in appearance, with silvery scales, easily rubbed off, thin, deep bodies, and tails quite deeply forked.

The alewife belongs to a group of great age in the earth’s history, and one which has survived, for one[Pg 59] thing, by reason of its numbers, and not by any skill in speed or individual pugnacity. It depends on the crowd rhythm for perpetuation. Its salt-water whereabouts are comparatively unknown, although it is thought it may not go very far afield; but in a run of alewives you might sense not numbers only, but something of the sea’s capacious demands that made these fish to measure. Green, gray, silver, they wear its colors, and seem built to nose into its space, or be carried with its moods.

Are there no individuals among them? It is perhaps no term to apply with so manifestly united a company. In any case we are deceived if we try to translate ourselves, our ability to choose, our eyes for pattern and variation, into an animal that can see us at best as an occasional, strange, blurred image appearing above the bank, and to whom everything but the water world is unknown. In a sense we know too little, and so do they, to discuss the matter.

Yet anyone, with a slipping, plunging alewife in his hands, knows it in some degree for its uniqueness. This green-backed, silver-sided water animal, smooth, supple, and muscular, with a sail-like fin on its back is definite enough. Its body is convex-sided, coming to a thin edge at the belly, shaped like shellfish, seeds, or Indian artifacts. From its undershot jaw to its tail, it is clearly a tough fish, and in our experience an adaptable one that knows its way.

This is the “sawbelly” all right. You can very easily[Pg 60] feel the serrations, or little teeth, with your fingers—it is one good way of telling alewives from sea herring in the dark. But the name “big-eyed” is perhaps most dramatically true of the alewife. Its black, round, shining eyes are very prominent in proportion to its small head and small mouth. They are large black disks like certain water-worn rocks, or they are great bubbles coming up from a dark depth. I fancied, seeing a tiny image of myself in the alewife’s eye, that I was reflected in a deep, impenetrable well.

It is known that a fish’s eye is somewhat like ours in that it has a lens, an iris, a cornea, retina, and optic nerve; but that it is designed to see under water, which ours is not. In J. H. Norman’s History of Fishes, he writes: “The eye, as is well known, acts after the manner of a photographic camera, the two essential parts being the screen or retina at the back, and the lens at the front, which projects an image of the outside world on the screen. The lens of a land vertebrate is somewhat flat and convex on both sides, but in the fish it is a globular body, the extreme convexity being a necessity under water because the substance of the lens is not very much denser than the fluid medium in which the fish lives. The space between lens and retina is filled with a transparent jelly-like substance, the vitreous humor. The transparent outer wall of the eye, the cornea, is somewhat flatter in fishes, and the space between this and the lens is filled by the watery, aqueous humor. In land vertebrates the iris of the eye[Pg 61] is capable of great contraction, and, acting like the diaphragm of a camera, regulates the amount of light allowed to enter the eye. In fishes it generally surrounds a rounded pupil, and has comparatively little power of contraction.”

I should add that an alewife’s eye is somewhat fixed, and not capable of much movement.

Back of the eyes and mouth are the gill covers that protect the gills underneath, which are weak and blood-filled, dark-red overlapping layers, like petals, four on each side. As the fish’s gill covers open and close, water passes over the gills, taking oxygen into the blood stream. The alewife’s heart, which pumps blood to the gills, is located directly below them.

This is a plankton eater, although it will eat shrimp, small fish, or young eels, on occasion. It has no teeth, or such a semblance of tiny, weak ones, back in its mouth, that they are of little use. The particles of food that come through its mouth are strained through a device known as gill rakers, which act as sieves or filters, in the form of fine hairlike growths mounted on the gill arches, the bony structures on which the gills are also arranged.

A female alewife can be recognized fairly readily by its size. On the average the males run from ten to eleven inches and the females from eleven to twelve, and the males are of course lighter. The proportion of males to females on the inland run seems to be about fifty-fifty.

[Pg 62]

Alewives weigh anywhere between eight and ten ounces. Part of the weight of both sexes during their spawning migration is accounted for by the roe; in fact, their ovaries and testes may become so enlarged as to fill up a large part of their bodies. The egg sacs of the female vary in color from pink to yellow or yellow-orange, depending on their stage of development. The milt, sometimes called soft roe, of the male, is white and pink.

To sketch a fish so generally is scarcely to know it, but even if I were able to give a good account of its complex skeleton down to the last bone, or discuss all the actions of its nervous system as known so far, I would not have done enough. Our bodies may have chemicals in common with them, but we will never know the fish.

The alewife I took from the water eluded me. Cold-blooded fish, warm-blooded man, the water’s triumph caught by the alien air. It slipped my hand and knowledge. “An aquatic vertebrate?” A mystery, though I recognized a life that shone with vibrant persistence, one of nature’s particularized energies, a wild texture as old as the animal world, a food that was the beneficent matter of all struggle and greed.

Were there more connections between us that needed exploration? How much fright, how much nerve-threaded darkness, how much throbbing electric quickness might not be receiving me in the distance of that fixed eye? Perhaps we strangers all meet somewhere in each other’s sight.

[Pgs 63-64]

[Pg 65]

The Herring Run area, small center of commerce and history, had been my starting point, but I had hardly begun to follow the alewives on their whole migratory route between salt water and the ponds above. First of all I had some background of local hearsay to bring into question. Did the herrin’ really go all the way down to South America in the wintertime? Was it true that each fish returned to the stream it was born in? Did they come inland on their spawning journey and then die, like the west coast salmon? I overheard a man say, “Poor fish! All that work just to die!” But that was one interpretation I could dispose of early, having seen them go back to salt water the year before. Did they only come in from the Bay at night or on foggy evenings? To find out would take more watching and waiting than I had done so far.

You might deduce this much to start with: the alewives, only a few at first, started to come inland in the spring when the brackish waters from the Stony Brook outlet were warmer than the Bay into which[Pg 66] they flowed, if only by a few degrees. They responded with sensitivity to the temperature. If the earliest fish were the oldest, it was possible that the later runs also corresponded to age groups, guessing by their size, and that the youngest came last of all. Evidently schools of alewives stay together during their ocean life according to the years when they were spawned. Yet why, between March and June, any given schools would come in when they did would be hard to tell.

There are places where you can watch the alewives approach, at the junction between tidal and inland waters. At Damariscotta, Maine, they swim up a wide tidal river until a fresh-water stream flows into it from a height above. I was told that the fish are seen massing and circling, sometimes for days, at this point, until by some communicated decision, or joint response—perhaps to pressure of numbers, combined with the right temperature conditions—they start going up. A cold snap may make them drop back to tidewater. In the same way, cold weather may discourage their coming in from Cape Cod Bay.

You can also see them schooling in the Cape Cod Canal at the entrance to the Bournedale run, but not at Stony Brook where the outlet flows into the Bay through low sand dunes, or sand flats at low tide. Whatever the local topography may be, the alewives are evidently attracted to the warmer currents and the lack of salinity in a stream where it flows into salt water.

[Pg 67]

In general the cause of their moving in together from the offshore depths is their sexual development. I have heard the speculation that this is affected by the increase in light at this stage of the season, but unfortunately know no more about it. In any case at the age of four, or sometimes three, they are ready to spawn, to follow out the new force that is in them, on an old track. Their timing, when to migrate, is a question of generation, a decision that has to be made once again in the earth’s timeless schedule. Perhaps there is a comparison to be made once more with the weather, in which the element of surprise is constant during the usual course of the season, the intangible variant still plaguing prediction. The turns to storm or sunshine have their own order in the years beyond the immediate one. Who knows when anything will happen? Suddenly the cicadas start to sing in the August trees. Why that day or hour? Because “conditions are just right”? Perhaps, if we could ever track down all the conditions. Natural acts may be repetitive, but no flight, or song, or new growth has ever existed before at exactly the same time, pitch, or ratio. They are part of the indefinite context of generation.

What about the alewives during their years in the sea? Very little seems to be known. According to Fishes of the Gulf of Maine by Bigelow and Schroeder: “The alewife is as gregarious as the herring, fish of a size congregating in schools of hundreds of individuals (we find record of 40,000 fish caught in one[Pg 68] seine haul in Boston Harbor) and apparently a given school holds together during most of its sojourn in salt water. But they are sometimes caught mixed with menhaden, or with herring. Alewives, immature and adult, are often picked up in abundance in weirs here and there along the coast, and it is likely that the majority remains in the general vicinity of the fresh-water influences of the stream-mouths and estuaries from which they have emerged, to judge from the success of attempts to strengthen or restore the runs of various streams.... But it is certain that some of them wander far afield, for catches up to 3,000 to 4,000 pounds per haul were made by otter trawlers some 80 miles offshore, off Emerald Bank, Nova Scotia at 60 to 80 fathoms, in March 1936.”

They also say, with circumspection: “It seems likely from the various evidence that the alewives tend to keep near the surface for the first year or so in salt water, and while they are inshore when older. But practically nothing is known of the depths to which they may descend if (or when) they move offshore, there being no assurance that those taken by trawlers were not picked up, while the trawls were being lowered or hauled up again.”

The view that most of the alewives stay in coastal waters near the fresh waters where they were hatched seems to be generally accepted, though the proof is sometimes hard to find. They occur at various depths in the sea as well as considerable distances offshore.[Pg 69] They are as likely to be found in deep as in shallow waters. I am told there are recorded views that landlocked alewives winter in the deep waters of Lake Ontario, and that shad, a close relative, have been found with near-bottom animals in their stomachs. I also have the information that during the summer of 1956 draggers in Passamaquoddy Bay were catching a large quantity of alewives and that “it looked as if they were near bottom.” Despite some having been picked up in weirs close to the shore at various times during the year, they have not commonly, if at all, been taken by draggers on the continental shelf except when approaching the shore during the spawning season. In other words their oceanic whereabouts have not been pinned down. All we can say, still presuming stocks are local along the coast, is that mature alewives move in from deeper waters offshore in the springtime, progressively later from south to north.

What might seem to be a curious exception to the rule is a run in St. John Harbor, New Brunswick, that occurs in the dead of winter. Alewives are taken there in late January and early February; but I find that this may not be so peculiar a phenomenon as it sounds. To begin with, St. John Harbor is joined with the Bay of Fundy, and when the fish move into it they are still at sea. The reasons for their move at that time is not clear, but as there appears to be winter seining of alewives farther down the coast along the shores[Pg 70] of neighboring Charlotte County, it is at least not unbelievable. The alewives then start through the harbor and move up the St. John River to their spawning grounds in the usual migratory months of April and May. I am told by the St. Andrews Biological Station that: “The inflow of the St. John River, particularly in April and May, dilutes the harbor water, especially at the surface. Whether it attracts alewives to the harbor or carries them there by deep circulation is a question.” This last point brings up the problem, quite beyond my powers to understand, of how the alewives orient themselves, how they find or are attracted to the waters in which they spawn. We may know very little about their life at sea, but their ability to find a particular stream or river may be an even greater mystery, which is not lessened by the probability that they have been there before. Whether as first-year spawners or repeaters the alewives seem to come back to the streams from which they migrated during the first summer and fall of their lives—when they were not more than a few inches in length. Not consistently—a certain amount of shifting between schools and change of locale may go on. Many go astray like migrating birds, or men out of crowds perhaps, but in general they do tend to return to their home streams. As a proof of this, ponds that were empty of alewives have been stocked with them, and the spawn returned as adults in three or four years’ time. This is the “parent stream” theory. With salmon[Pg 71] it has apparently been shown to be a fact; although it is not so much the stream they were born in to which they return as the stream in which they grew up. Salmon eggs have been taken out of one river, moved to another, and then the hatched fry were tagged. They migrated to the sea and returned to spawn in the second river where they had their growth.

So what is to account for the alewives being able to find a “parent stream” that might be only a few yards wide, out of all the great stretches of the Atlantic coastline? They left it when they were no more than one and two-fifths to four inches long, but somehow, growing up in the sea, they must always have been oriented to that home base. They may have stayed reasonably near by, but even so this ability is hard to fathom.

Disregarding the question of how they arrived at that point, how could they tell one stream from another? They enter innumerable rivers, streams, inlets, some of them in close proximity. One theory has it that they are able to find their home waters by their characteristic odor, their special composition, to which they were conditioned when young. Even so, how did they get there? How can fish way offshore in waters of a consistent temperature, without any landmarks, tell which direction will take them to their home street? It is quite likely that they would be able to detect the outlet waters where they merged with the sea, but a stream may not reach very far, perhaps[Pg 72] a few hundred yards or more at low tide, before being totally absorbed. All the way along the coasts, rivers and streams pour in fresh water, mixed in the estuaries so that it is brackish when it reaches the sea. The sea water increases in salinity as it gets deeper over the continental shelf. An alewife may detect very slight differences in salinity comparatively far out, but we are still not much closer to realizing how it finds its way.

What it amounts to is that no particular factors seem to be able to explain this directional ability of theirs. Not the response to changing currents in the spring sea, not the perception by fish of varying pressures in salt water, or of differences in salinity, nor their possible ability to use the sun as a reference point in navigation ... none of these approaches have yet solved the great mystery. Do they have some special sense, some perceptiveness, about which we know nothing? Scientists have measured and probed their reactions for a long time, but so far have not found any evidence of a special sensory ability. Biologically, fish do have several unique characteristics. For example, they have an “air bladder” by means of which they are able to adjust themselves to changing densities in the water. They also possess a “lateral line” organ, consisting of a tube or canal under the skin filled with mucus and connected to the nervous system. This sense, closely associated with hearing, enables them to detect vibrations of a very low[Pg 73] intensity in the water and to avoid obstacles, such as an approaching bank or another fish. Aside from that, fish can smell, they have sight, and they have a sense of touch and taste.

These known senses are what scientists count on in investigating the migratory behavior of fish. They test their responses to different stimuli. On that basis, one of the most recent directions to be explored centers around the environmental factors which the fish are subjected to, such as currents, temperatures, the physical and chemical nature of the waters through which they swim. These factors are supposed to guide them successively on their migrations and to be so consistent year after year that the responsive fish return to their streams of origin because they never got off the track. Different schools, or age groups, of alewives would go to separate streams, because they responded differently, as Gerald B. Collins puts it in his study of alewives at Bournedale, “to the existing patterns of environmental stimuli.” Homing, from the environmentalists’ point of view, is neither a matter of memory nor mystery.

I do not have enough knowledge behind me to discuss such a method or approach, but it does seem to have the advantage of comprehensiveness, of taking the whole journey in. It does not depend on any single factor to explain migratory behavior, and it provides a good long track of exploration, step by step.

Whether the migrant fish behave as mechanically[Pg 74] as this suggests, or whether the factors involved are separately either as consistent as they are supposed to be, or amount in the aggregate to as much as they should, remains to be seen. We are still in the realm of theory, however rationally expressed, and do not know yet how the fish find their destination.

Can a fish judge its course by the sun, or by the circulation of the waters of which it is so much a part? Can we talk about a homing instinct, or orienting ability, in connection with it? What are we defining? I don’t think I beg the question by finding it pertinent that civilized human beings have to some extent lost their ability to find their way in the woods, or no longer rise and sleep with the sun, or that they are not aware of the changing tides. Some old directional knowledge may still be innate in us, though we seem to think we have no need of it. Our puzzle, or lack of definition, may lie with ourselves as much as the alewives. In any case, what we try to find out by fact or abstraction is already known to the fish.

They are still ahead of us. So much of their motion seems to be a part of the race as a whole, synonymous with its great water world, that it is almost as if they found their way like the wind and tides, elemental forces that we find it hard to evaluate. We try to pin down that which expands immeasurably beyond us.

[Pgs 75-76]

[Pg 77]