Title: The mid of the maintop

Author: Arthur Lee Knight

Illustrator: Hilda K. Robinson

Release date: October 17, 2025 [eBook #77070]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Ernest Nister, 1900

Credits: Al Haines

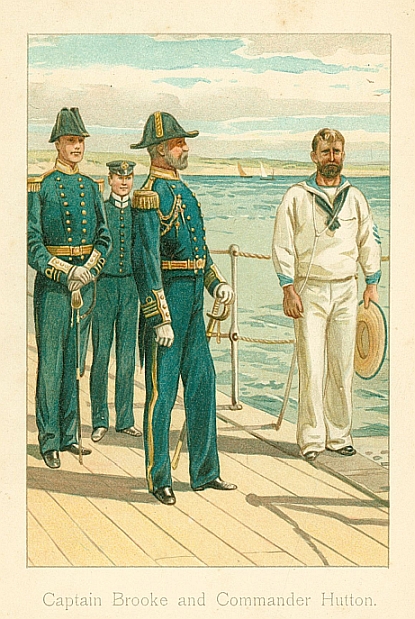

Captain Brooke and Commander Hutton.

By

Arthur Lee Knight,

Author of

"The Young Rajah," etc.

With Pen-and-ink Illustrations

by

Hilda K. Robinson.

London:

Ernest Nister

New York:

E. P. Dutton & Co.

Printed in Bavaria.

651.

THE MID OF THE MAINTOP.

The "Forte" was a fifty-gun frigate employed upon the East Coast of Africa in the suppression of the slave trade. About a week previous to the commencement of our story the ship had been to Zanzibar Harbour, where the rest of the squadron was assembled, and Captain Brooke and his second-in-command, Commander Hutton, had reported themselves on board the flagship, which was a modern man-of-war, and had received instructions from the admiral to sail along the coast, keeping a sharp look-out for slave-dhows, at that time very numerous. On the captain's return the "Forte" at once sailed, and at the time our story opens she was about fifty miles to the eastward of Ras Hafoon, a bold bluff promontory formed by huge sun-scorched rocks, and utterly destitute of vegetation of any kind.

The captain looked anxiously at the barometer in his cabin. It had begun to fall ominously.

There was a hurried knock at the door.

"Come in," shouted Captain Brooke, as he snatched his cap from a peg.

The lieutenant of the watch entered.

"There's a dense fog driving up, sir," he said, "and I think we're in for a bit of a blow as well."

"Take a reef in the topsails," responded the captain promptly, "and turn the hands up."

A few seconds later the order was echoing along the "Forte's" crowded decks, and the bluejackets were streaming up the hatchways, laughing and joking as they went.

The captain unrolled a chart, glanced for a moment at it, and then followed the lieutenant on deck.

A squall had burst upon the ship. The topmen were swarming up the rigging: every man was at his post.

Jack Villiers was one of the smartest midshipmen on board the "Forte," and was a general favourite with everyone. As he was a smart athletic youngster, he had been placed in command of the maintopmen when they were aloft, and was always in the thick of any adventure, which very much endeared him to the bluejackets' hearts.

As soon as the reef was taken in on this occasion, Jack sent his men down from aloft and then prepared to follow himself. The "Forte" was heeling over to the strong breeze, and tearing through the water at the rate of eight knots an hour. The scud and spray were flying over the hammock-nettings, but a dense fog had begun to envelop the ship, and blew in clouds of vapour through her network of rigging and amongst her white sails.

Jack ran down the ratlines as fast as he could.

Jack ran down the ratlines of the rigging as fast as he could now that his duty aloft was done. Unfortunately, at this moment the heavy wet main-sheet was dragged upwards by the straining of the sail, and struck against Jack's feet with such violence as to make him lose his hold of the rigging.

In an instant he was flung upwards and then hurled overboard into the midst of the foaming waves.

Lifebuoys were thrown overboard, the ship was hove-to, and a boat was sent away; but by this time Jack had been lost to sight in the driving mist. When last seen he was swimming rather feebly as if dazed by his fall from aloft.

The coxswain of the cutter searched in vain for the missing boy. No trace of him could be found. The wind howled in fitful gusts, and the fog grew thicker and thicker. It was impossible to see more than a few feet from the boat, but the coxswain shouted again and again in his loudest tones in the hope of being heard by Jack. Very gloomy did the seamen look when no answer came to these repeated cries.

The storm was now very violent, and the cutter was in danger. The "Forte" was of course out of sight, but she now began firing signal-guns.

"The skipper might save his powder," said the coxswain anxiously, "for we can't fetch the old hooker in this lumpy sea. Lay in your oars, lads, step the mast, and set a close-reefed sail. I reckon it's our only chance to escape being swamped."

"And the poor young gentleman," said one of the men, with a sigh; "I'm afraid we'll never see him this side of eternity again."

"It'll break his mother's heart," remarked the coxswain huskily; "but we've our duty to do, mates, and if the Lord calls him we mustn't complain, He being our Commander-in-Chief, so to speak."

The boat under her rag of a sail flew before the wind. The "Forte" continued to fire guns at intervals, but it was impossible to pay attention to them, and soon the sound died away altogether.

For hours the cutter held on her way, the coxswain not daring to alter course for fear the boat should be swamped.

Suddenly the fog lifted and began to roll away over the ocean. At the same moment the gale began to abate in violence and the sea to go down. In eastern climes a sudden storm quickly expends its force.

The cutter's crew gave a shout of joy. Away over the crests of the still agitated sea they perceived the misty outlines of their ocean home, H.M.S. "Forte." She was apparently standing down in their direction.

"Here's a piece of good luck," exclaimed the coxswain; "that's the old hooker, as sure as guns are guns, and, what's more, the wind has veered to the westward, and we can run down and jine company with her in the shake of a pig's whisker."

It was the work of a few moments to alter course and shake a reef out of the foresail.

As the last remnants of the fog disappeared over the eastern horizon, the "Forte" loomed more and more distinctly into view. She had topgallant-sails set and single-reefed topsails. The shades of evening were now beginning to fall, and the lurid sun was shaping his course towards the bleak and barren heights that guard the shores of the Great Dark Continent.

As soon as the "Forte" perceived her boat she hove-to. As the cutter ran alongside, the coxswain and his mates noticed that the hammock-nettings and ports were full of men anxious to learn the fate of their favourite midshipman.

One glance into the boat was sufficient.

The captain and his principal officers stood at the entry-port with pale, set faces. On hearing the coxswain's report, they turned sadly away, and an unbroken silence reigned throughout the frigate for a few moments.

"Hoist the cutter up," ordered Captain Brooke, in a voice broken with emotion, "and then put the ship on her course again."

It was three bells in the first watch when the coxswain of the cutter—whose name was Lobb—went on deck. Some supper and a short sleep in his hammock had wonderfully refreshed him. The gale had entirely blown itself out, and the sky was clear and strewn with brilliant stars, amongst which the Southern Cross and the Centauri glittered like gorgeous jewels set in lapis lazuli of an indigo tint. The breeze still held from the westward, and was strong enough to make the frigate heel over till her shining copper, dripping with salt spray, was visible on the weather side.

Lobb went to the lee entry-port and gazed out over the phosphorescent sea. His heart was heavy as he thought of poor Jack Villiers's sad fate, and mechanically he took off his cap and sought for the pipe that lay snugly therein.

"A bit of baccy is the thing to soothe a chap what's got a fit of the blues," he muttered to himself, as he charged his pipe with tobacco. "I'm jiggered if it wasn't the blackest day in my life when I failed to pick up that youngster—the brightest young fellow in the ship he was, and that there ain't no denying."

His meditations were interrupted by the middy of the first watch, a bright, fair-haired boy, who, eagerly running up to him, exclaimed: "Oh, Lobb, I wanted to see you so much about——" And he hesitated.

"Ah, it's Mr. Thring," said the coxswain, pausing in the act of lighting his pipe. "I'm main sorry for you, sir, I can assure you, for I know right well what chums you and Mr. Villiers were, and it must strike to your very heart, as one may say."

Thring's eyes filled with tears, and he felt thankful that it was too dark for the seaman to observe his emotion. He was quite a youngster, having joined the "Forte" straight from the "Britannia" training-ship only a year before our story opens.

"Tell me all that happened, Lobb," he said at length, in a strained voice. "The captain only gave me a few particulars."

The seaman lit his pipe, and between the puffs told what little there was to tell. It was little indeed, but Thring listened to the recital with breathless interest, soothed by the thought that this rough but soft-hearted sailor was fully in sympathy with him.

"The sea looks so beautiful now," he said, when Lobb had finished his short story. "No one would believe that it could have——I say, Lobb"—gripping the seaman's arm—"is it possible that my chum could have escaped in any way?"

"Nobody could have lived long in that sea," answered the coxswain sadly; "but don't you take on too much, sir, about this unfortunit business. What I says to the crew of the cutter I says to you, and mind you, lay it to heart like a brave youngster: 'We've our duty to do, mates,' says I, 'and if the Lord calls him we mustn't complain, He being our Commander-in-Chief, so to speak.'"

There was a long silence.

"I wish we could come across some slavers," said the middy at length; "I feel as if active service is the only thing that would drive poor Jack's dreadful fate from my mind."

"We ain't had much luck in that way, sir, have we? But I reckon the wheel of fortin will turn by-and-by, and we'll get a haul of prize-money. To-morrow it's like enough we'll be in the latitude of Cape Joo-joo, and the chances are we'll fall foul of some of these swabs what earns their living by trading in human flesh."

"If we do, I only hope the fellows will fight," cried Thring, with flashing eyes.

"I hope so too," said the coxswain, as he knocked the ashes out of his pipe. "I'm always ready for a scrimmage with them Arab gentry, for they're the blackest-hearted scoundrels that walk this earth, there's no mistake about that."

"Four bells, sir!" reported the marine sentry, marching up and saluting the middy of the watch.

"Make it so," answered young Thring briefly. "Good night, Lobb; I must go and examine the bow-lights, and take the corporal of the watch round the decks."

"Right you are, sir. Goodnight, and don't you let your young heart be frettin' too much, for, if you'll excuse me taking the liberty of speech, I can't abear to see that bright face of yourn a-clouded over. Don't forget the Commander-in-Chief when you turns into your hammock at eight bells."

And carefully stowing his short clay away in his cap, Lobb went thoughtfully down the main hatchway in search of his own hammock.

The following day the "Forte" chased several suspicious-looking dhows, but one or two, being smart sailers, managed to make their escape by carrying a press of canvas. The frigate, having lofty masts, was visible to these Arabian mariners from a very long distance, and, as the reader may suppose, the vessels that are employed in the slave trade always keep a sharp look-out for British men-of-war, for well do their captains know that, if captured, the slaves found on board are immediately released from their cruel captivity and the dhows sunk or burnt.

The vessels which could not elude the "Forte" were promptly boarded by the frigate's boats. All these craft turned out to be lawful traders, with the exception of one, which proved to have thirty-five slaves on board. The jolly-boat, having taken possession of her without striking a blow, the wretched slaves, more like walking skeletons than human beings, were transferred to the "Forte," and the dhow was sent to the bottom of the ocean by a few well-directed shots from the frigate's forecastle guns. The Arab captain and his crew were then put ashore upon the arid, desolate strand and left to find their way as best they could to the nearest native settlement.

The wind having dropped very light, the "Forte" was put under steam, and proceeded slowly northwards, keeping the land well in sight upon her port beam. No vessels now remained in view, but a large school of black fish were seen spouting energetically to the north-east, and the sea was alive with shoals of flying-fish and an occasional bonito.

"We're very short of sand for scrubbing decks, sir," said the commander to Captain Brooke during the first dog-watch; "may I send a boat ashore to fetch some? As you know, a river falls into the sea just to the southward of Cape Joo-joo yonder, and there's a deposit of some of the finest sand in the world close to its mouth."

"Well, I see no objection," answered the skipper. "It's a very quiet bit of the coast, and the men couldn't well come to any harm."

The frigate's nose was accordingly pointed in towards the land and her speed increased; but the precaution was taken of placing leadsmen in the chains.

"I should like to send young Thring in charge of the cutter, sir," observed the commander to his chief. "The poor little chap is very much cut up about the loss of his middy chum, and it would be a charity to let him go on the expedition."

"Go he shall, then," said the captain kindly; "he's a promising youngster and likely to do the service credit. At the same time, Hutton, don't forget that the boy has had but little experience. I don't think this part of the coast is inhabited, but warn Mr. Thring that he is not on any account to interfere with the natives if they put in an appearance. Should there be any attempt to oppose his landing, he is at once to return to the ship and report himself."

"Pass the word for Mr. Thring, quartermaster," sang out the commander.

"Our charts of this coast are very imperfect," said the skipper; "I think we had better not venture any nearer in. Do you remember that small bower anchor we lost off Ras Pundoo?"

"I do indeed, sir; we'd better stop the engines and get the first cutter lowered. Her coxswain, Lobb, is a thoroughly reliable man, and will take good care that young Thring does nothing rash. When a middy takes the bit in his teeth there's no controlling him!"

Captain Brooke smiled. "The old spirit isn't dead," he said; "there are always chips of the old block coming to the fore, who think a lot of the honour due to the glorious white ensign. One of my own youngsters is on board the 'Britannia' at this moment learning to be a young sea-dog."

The "Forte" now lay "as idle as a painted ship upon a painted ocean," rolling gently on the heaving land-swell. It was almost a stark calm, but a catspaw here and there played over the surface of the sea and fretted its blue-green surface into little furrows. Screaming seabirds swooped around the ship, and just under the quarter an enormous wily-looking shark kept watch and ward, eyeing greedily some refuse from the cook's galley which was floating towards him.

Young Thring was only too delighted to go in charge of the cutter, and Lobb was equally pleased—though the duty of collecting sand was usually prosaic enough.

There is a saying, however, which again and again has proved itself a true one: "It is always the unexpected which happens."

What Lobb called "the wheel of fortin" revolves rather quickly sometimes.

The light breaths of air that were stirring were moving in the direction of the land, so the cutter hoisted her lugsail and slowly glided towards the African shore.

"Is there no surf on this part of the coast?" questioned Thring, as he buckled on his dirk around his waist. "I don't see it, or hear it."

"There's less here than anywhere," answered the coxswain; "leastways, in fine weather like it is at present. When there's a gale blowing there's some scud and spray flying about, I can tell you."

"The little bay we're making for seems to be protected on the south side by a high, jutting point," said the middy, who was now observing the coast through his telescope.

"Right you are, sir, and that makes it a safe place to land when the south-west monsoon is blowing. That is where the little river Joo-joo runs into the sea."

"You know this part of the coast well, Lobb, evidently."

"Yes, I do, sir. 'Taint the fust time I've landed here for sand, not by a long chalk. On one occasion, when I was in the old 'Ariadne,' we went up the river Joo-joo in the pinnace to get a supply of fresh water."

"And you fell in with some natives I expect, didn't you?"

"Never a soul did we see, sir. There was a lot of mischievous-looking baboons a-cruising about and some flamingoes, but nothing else living did we see. No seaside lodgings to let, nor nothing of that sort." And Lobb laughed at his own joke, his mind reverting for a moment to his own Mary Anne, who let genteel apartments overlooking the sea at the little Dorsetshire town of Swanage.

The words had hardly escaped his lips when the coxswain suddenly gripped the middy by the arm, and pointed in an excited manner in the direction of a jutting point.

"Do you see that mast of an Arab vessel, sir?" he almost shouted, "just over them rocks yonder."

"See it? I should think I did! Now what in the name of fortune is she skulking behind that point for?"

"Why, for all we know, she may be a slave-ship," said the coxswain, with much suppressed excitement in his tones. "Out oars, lads, and we'll soon see what larks that chap is up to."

The middy, in a state of great excitement, turned his telescope upon the stranger.

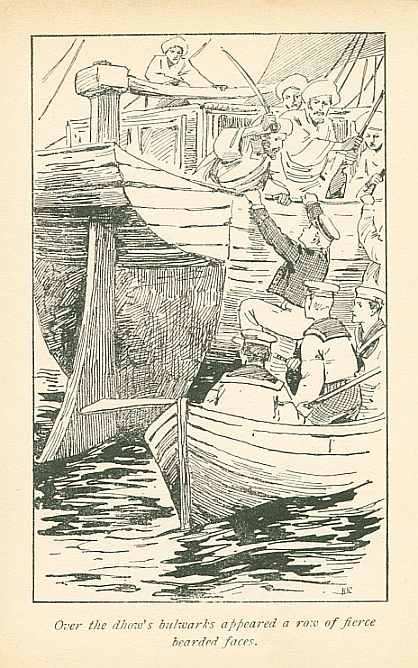

Over the dhow's bulwarks appeared a row of fierce

bearded faces.

"She's a dhow right enough," he said briefly; "but the commander warned me not to interfere with the natives."

"That's right enough, sir, that is," returned the coxswain; "but this is another pair of shoes altogether. A dhow is a dhow, and ain't nothing to do with shore-going loafers."

As it was now a stark calm, recourse was had to the oars, and the cutter slipped along through the water, which was so clear that the fish were visible swimming about in all directions.

"If yonder craft should prove to be a slaver, we ain't got no weapons aboard to fight the swabs with," observed one of the cutter's crew.

"The stretchers will serve our turn, I reckon, chum," said the coxswain grimly, "and there's a shovel or two. We must be careful what we do, though, for this hooker may prove to be a lawful trader, and in that case we can't touch her."

The cutter, urged on by her willing crew, soon doubled the point, and found herself in the mouth of the river. The dhow lay quietly at anchor, and it appeared as if her crew had not as yet caught sight of the man-of-war's boat. She looked a small vessel, and boasted of only one very raking mast and a lofty tapering yard. Over her clumsy stern floated a blood-red flag attached to a bamboo flagstaff.

"Give way, men; we'll soon be alongside her," cried the middy, in sharp, decisive tones. "To my mind she has the look of a regular slaver."

Shouts of alarm now rang out from on board the stranger, and her Arab crew were seen hurriedly rushing hither and thither like a horde of disturbed ants.

"There's a big crew aboard; that's suspicious," murmured the coxswain to himself. "How I wish we had poor Mr. Villiers here! 'Tis just the job he liked to have a hand in, the plucky youngster"—and something very like a tear stood in the seaman's eye as his thoughts reverted for a moment to the sad events of the preceding day.

The crew of the dhow were now seen mustering in the waist of their vessel.

As the cutter drew near, the coxswain, who knew a few words of Arabic, rose in the stern-sheets and shouted out that he was going to board for the purpose of examining the dhow's papers.

The only answer to this was two or three jets of flame which gushed out from over the vessel's taffrail. Some slugs whizzed over the British seamen's heads and splashed harmlessly into the water beyond them.

"I'm jiggered if the sharks ain't slaver-men then," exclaimed the coxswain indignantly. "Stand by to lay in your oars, lads, and follow Mr. Thring and me aboard with shovels and stretchers in your fists."

The cutter dashed alongside the dhow. Over the latter's bulwarks appeared a row of fierce bearded faces, and the sunlight glanced brightly on spears and scimitars. It was an exciting moment.

"Bowmen, hang on there forrard!" shouted the middy, as he drew his little dirk from its sheath—a weapon never intended for active service.

"Grab some of them chaps' weapons as soon as you can, lads," roared the coxswain, as he clambered up the dhow's clumsy side; "and then we'll play 'old Harry' with the swabs."

With a dash and determination which nothing could withstand the cutter's crew followed their youthful leader on board, dealing telling blows with their shovels and stretchers as they did so, but unfortunately one or two seamen were wounded by the spears of the foe before they gained the deck of the slaver.

Now came a fierce hand-to-hand tussle. The Arabs had uttered triumphant shouts of joy when they perceived that the British seamen were without weapons, for they deemed it an easy matter to overcome them. So they thrust with spear and cut with scimitar, fiercely urging each other to drive the enemy back into their boat again. But they soon found they had tough customers to deal with—men who were accustomed to fighting against tremendous odds. The coxswain, an immensely powerful man in the prime of life, soon wrested a scimitar from one of his opponents, and, rushing into the thick of the fray, cut down everyone who opposed him.

Young Thring had not been so fortunate. Having gained in safety the dhow's bulwarks, he thrust with his dirk at an Arab who was opposing his further advance, and by great good luck wounded him in the sword-arm, causing the man to drop his spear over the taffrail, whence it fell into the cutter. The middy was about to spring on board when he received a violent blow on the chest from a clubbed musket and fell backwards into the boat, in the stern-sheets of which he lay senseless for a few moments. The bowmen were unable to assist him, owing to their important duties forward.

Quickly regaining consciousness, however, the youngster, who had never lost his grip of the dirk, threw that almost useless weapon aside, and, seizing the formidable spear which the Arab had dropped into the boat, he once more clambered up the dhow's tall side.

As he did so a hideous chorus of shrieks and screams, which rose high above the sounds of strife, rent the air; and a number of terrified slaves burst open the flimsy bamboo deck and, rushing up in a body, began throwing themselves overboard as if in fear of their lives. Many of these poor creatures, unable to swim, sank at once beneath the surface. The scene of confusion on board the dhow was now indescribable. In the midst of it Lobb, scimitar in hand, ran up to the middy.

"I've killed the captain of these slaver-men," he said excitedly, "and the rest of the beggars was so took aback at the loss of their chieftain that they caved in and laid down their arms. The ship is yours, sir, but we must do our best to prevent these slaves escaping. Mad as March hares, the lot of 'em seems to be, and that's the truth!"

By dint of almost superhuman efforts, the middy and his men succeeded in pacifying the terrified Africans who still remained on board. A good many had reached the shore, and were clambering up the rocks in a wet and dripping state.

The Arabs had been disarmed and the wounded men were being attended to when young Thring and his followers were thunderstruck by hearing a loud and piercing cry from amongst the cliff-like rocks on shore: "Help! help!"

"The voice of an Englishman!" exclaimed Lobb, in the greatest astonishment; "well, that beats everything as——"

He was interrupted by an agonising shout from Thring, who staggered back as if he had been shot: "It's Villiers! it's Jack Villiers!"

There could be no doubt about it. Extraordinary as it may appear, there undoubtedly was the mid of the maintop—supposed to be fathoms deep in an ocean grave—with his arms bound behind him, being hurried away inland by a small party of armed Arabs who had just a few moments before emerged from a cave amongst the rocks immediately above the spot where the dhow lay at anchor. As Thring gazed in a petrified manner at the flying group, he saw to his horror that one of the Arabs had felled his chum to the ground with a blow from the butt-end of a pistol.

Some of my young readers may possibly have guessed that they would hear of Jack Villiers again. "There's a sweet little cherub that sits up aloft and looks after the life of poor Jack," isn't there? Of course there is, but still, one may tempt Providence too far, and I cannot help feeling extremely nervous when I think of the very awkward fix my hero is undoubtedly in, for his Arab captors were very much inclined to assassinate him at this crisis in his fate, as they attributed their misfortune in losing the dhow entirely to his enforced presence amongst them; whereas we know that it was nothing of the sort, the discovery of their vessel having been the result of a pure accident.

When Jack Villiers fell overboard from the "Forte's" main rigging he was partially stunned by the violence with which he struck the water; but, being a strong, athletic boy, and a splendid swimmer, he soon recovered himself, and struck out desperately, in hopes of reaching one of the many life-buoys that he knew must have been flung overboard into the wake of the ship. The sea, however, had become very boisterous, and the great waves dashed over him again and again, drenching him with their stinging salt brine; and the fog had become so dense that he could not see more than two or three feet in front of him. It was a terrible position for a boy to be in, but Jack was of that sterling stuff that heroes are made of, and was determined to make a brave struggle for life.

"If it wasn't for this horrid fog," he muttered to himself as he dashed the salt spray from his eyes, "I should be as right as a trivet, for I could certainly keep myself afloat till the boat picked me up."

Jack, of course, had no idea in which direction he was swimming. As a matter of fact, he was moving away from the "Forte" instead of towards her. The water in the Indian Ocean is so wonderfully buoyant that the middy was not much incommoded by his clothes, which were of very thin texture. The temperature, too, was warm enough to prevent any feeling of numbness.

Jack's heart began to sink a little when he fully recognised how difficult it would be for the crew of the boat to find him. He had had sufficient experience at sea to know that when a man falls overboard in half a gale of wind he is washed away an immense distance from the ship in an incredibly short space of time. He was aware also that the cutter could not be lowered until the way of the ship was nearly stopped, and this involved much necessary delay.

Jack listened intently for the friendly sound of oars grinding in the rowlocks, or for the shouts of his searching shipmates, but amid the roar of the elements not a sound could he distinguish. Once or twice he shouted at the top of his voice, but this he quickly found exhausted him too much, and it was absolutely necessary that he should husband his strength as far as possible in order to keep afloat at all in such a tempestuous sea.

Presently, to his great joy, our hero was struck violently on the shoulder by a circular cork lifebuoy, which was one of those thrown overboard from the "Forte's" poop. With great presence of mind Jack seized the buoy in a strong grip, and it was lucky he did so promptly, as in another moment it would have been washed far beyond him by a rolling wave.

This buoy undoubtedly saved the mid of the maintop's life, for, as we know, the cutter never came within hail of him, in spite of all the efforts of her devoted crew.

Jack never knew how long he drifted about at the mercy of the waves, clinging with desperation to the lifebuoy; but at length, as he was beginning to feel that his strength was fast ebbing away, and that the end must be very near, the fog began to almost imperceptibly melt away, and the middy saw to his delight that there was a sailing-vessel within half a mile of him, staggering along in his direction under a reefed sail, a pile of foamy water at her bows.

Our hero's heart sank a little, for he quickly perceived that the stranger was a dhow. Of the "Forte" there was no sign, but the horizon was by no means clear as yet.

"After all, she may be a lawful trader," muttered Jack, "and if I can only manage to attract her attention, her captain will no doubt land me at Aden or some British port."

By great good fortune, the dhow held straight on her course, and this brought her within a fathom or two of the spot where our hero was so bravely fighting the waves. So exhausted and weak had Jack now become, however, that when he tried to shout in order to attract the attention of the crew of the stranger he found himself unable to utter a sound. Nor did he dare to quit his hold of the lifebuoy even to wave one arm.

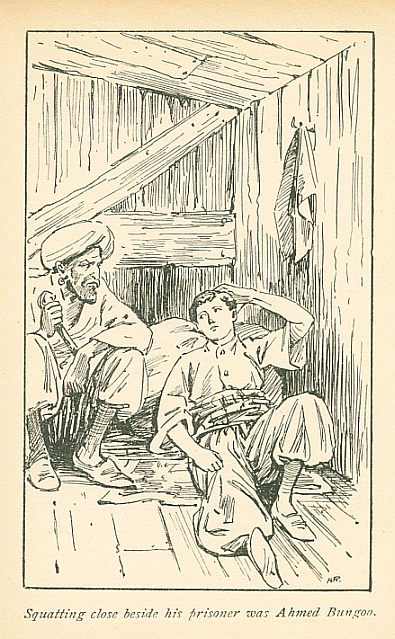

Squatting close beside his prisoner was Ahmed Bungoo.

The captain of the dhow, who happened to be steering his vessel, had the eyes of a lynx, and it did not escape his glance that upon his port bow was a European castaway, clinging to a buoy and buffeted about by a still tempestuous sea. The Arab skipper hated Englishmen like poison, and it would have been quite in keeping with his character to have held contemptuously on his course and left a drowning human creature to perish, but on this occasion he was induced to change his mind by the fact that he thought he perceived the flash of brass buttons upon the middy's jacket, as it rose and fell upon the tumbling waves.

The love of gain had a firm hold upon the sordid mind of this Arab chief. Perchance this was a naval officer, for whose release from captivity the British Government might be induced to pay a heavy ransom! It was too good an opportunity to be lost! The wily Arab promptly hove-to his clumsy craft, and sent away a boat to rescue the castaway.

The long and terrible strain had been too much even for a boy of unusual physical strength. No sooner was Jack bundled unceremoniously on board the dhow than he fainted dead away.

On recovering consciousness, our hero found himself lying upon the rough bamboo deck of a rude cabin built under the poop of the Arab vessel, and dimly illuminated by the open doorway, there being no other means of admitting air or light. A cushion stuffed with native cotton and covered with Turkey red supported Jack's head, and, to his astonishment, the middy found that his own dripping clothes had been stripped from him and their place taken by an Arabic jacket and pair of loose trousers secured by a cummerbund; his feet being slipped into a pair of yellow shoes.

Squatting upon his haunches close beside his prisoner, and with his subtle dark eyes fixed intently upon the middy's blanched face, was Ahmed Bungoo, skipper of the dhow, and one of the most noted slave-dealers of Zanzibar.

The Arab gave a grunt of satisfaction when he saw that the midshipman had opened his eyes, for he had feared for some almost intolerable moments that the prisoner would slip through his fingers.

For a few seconds Jack felt strangely bewildered, then memory asserted her sway in a flash, and he distinctly remembered the train of incidents which had led up to his almost miraculous rescue from a watery grave. He tried to sit up, but fell back helpless with a groan.

Ahmed frowned, and played with the hilt of a gaily-ornamented knife which was stuck into his girdle. He was about to speak when he saw that his captive had fallen into a profound sleep—the sleep of exhausted nature.

Our mid of the maintop slept tranquilly for many long hours, and when he eventually awoke felt quite recovered and as ravenous as a shark. He found himself still in the same position upon the deck of the cabin, but the lynx-eyed skipper had disappeared. In his place a gaunt-looking, grizzle-headed Arab stood on guard at the entrance of the cabin—which was innocent of a door—armed with a very long-barrelled musket and a curved scimitar.

Anxious to thank his preservers, and curious also to ascertain the nature of the vessel which had picked him up, our hero rose to his feet and moved towards the sentry, intending to pass him and go in search of the captain. The Arab, however, perceiving his intention, immediately barred the entrance with his long musket, at the same time uttering some sharp order in Arabic, which of course Jack did not understand. The middy at once gathered, however, from the man's threatening manner that he must consider himself a prisoner, and, thinking it wiser for the present to obey orders, he re-seated himself upon the deck, and, pointing to his mouth, said in a loud voice: "Me want some grub very bad, Johnny."

The sentry shouted to someone who was invisible to Jack, and presently a short, repulsive-looking native with a very black skin appeared upon the scene, bearing in his huge hands a chatty of boiled rice and a wooden spoon. This dish he set before the midshipman, and signed to him to eat.

Jack lost no time, and began to attack the rice with avidity, the two natives eyeing him closely and with the utmost gravity during the proceedings. The rice, being flavoured with a little curry-stuff and some pieces of chopped brinjal, was by no means unpalatable, and the middy left not one grain in the bowl "for manners." Indeed, he felt very much better for the meal.

The short black attendant stalked out with the empty bowl, and almost at the same moment in stalked the Arab captain with an unmistakeable scowl upon his face.

"If that chap isn't a slave-dealer, may I go back to the nursery and pinafores," muttered the mid of the maintop to himself; "and I'm in a jolly tight place if this is a slave-dhow, unless one of our cruisers should happen to fall foul of her."

Feeling sure that this individual was the captain, and anxious to conciliate him—Jack was a born diplomat—our hero made the chief a neat little speech in English, expressing his thanks for past favours, and making a request that he might be landed at the nearest port.

The captain shook his head vehemently, as if to intimate that the English tongue was utterly unknown to him. Then, turning to the sentry, he said in Arabic: "By the beard of the Prophet, a handsome youth! What thinkest thou that Christian dog, the English admiral, will pay for him, eh, Khyraz?"

The sentry twirled his moustache thoughtfully. Then he said, with a hoarse, guttural laugh: "Perhaps the admiral will pay you in cannon-balls instead of gold, O Ahmed, my chief; it's a way the dogs have!"

The captain scowled at this pleasantry. Then he observed tranquilly: "I think it will be sufficient gold to buy a hundred slaves with in the Zanzibar market. We shall do well on our next voyage if we have the good fortune to escape the men-of-war."

Jack's heart rather sank when he found that the captain did not understand any English. How could he convey to him his wish to be landed at the nearest port?

As our hero was turning over these thoughts in his mind, a member of the Arab crew came below, and reported that the yard had been sprung in the gale and needed repairs.

Ahmed, after giving some rapid orders to the sentry, hurried away, and Jack was left to his own meditations, which were by no means pleasant ones.

So badly was the dhow's yard injured that Ahmed decided to put into the Joo-joo river, where he could carry out the necessary repairs whilst his vessel lay securely at anchor. The dhow drew very little water, and safely entered the estuary only a few hours before the "Forte" appeared upon the scene.

The cutter's crew under young Thring's command had been mistaken in imagining that they were taking Ahmed and his men by surprise. There is a saying: "You do not catch a weasel asleep," and the slaver-captain very closely resembled that animal, and was always on the alert and ready for emergencies. Thoroughly alarmed as he was by the apparition of the man-of-war in the offing, and of her boat approaching the shore, he yet trusted to his usual good luck—having never been captured by a cruiser—and hoped that his presence in the river would pass unobserved, shrouded from view as he deemed himself to be by the jutting point of rocks.

The instant, however, the wily Ahmed recognised that the cutter's nose was turned in his direction, he calmly and quietly prepared for action, and as a precaution sent Jack Villiers ashore in charge of three fully-armed men, on whose faith and courage he knew he could implicitly rely.

In dogged, obstinate bravery this slaver-captain was certainly not deficient. He was prepared to fight to the last drop of his blood in defence of his vessel and human cargo. With regard to his prisoner, Jack Villiers, the chief was very much averse to treating with naval officers for his release, much preferring that negotiations for that purpose should, if possible, be carried on with a Consular Agent at some port. Herein he showed his wisdom—the wisdom of the serpent.

Thring could scarcely believe his eyes when they fell upon his chum Jack being hurried away up the cliffs by three swarthy, fleet-footed Arabs. That piercing cry of "Help! help!" had gone to his heart, for he did not fail to instantly recognise the well-loved tones of that friend whom he had mourned as dead. If it had not been for the fact that the Arabs, in the hurry and confusion, had omitted to gag their captive, even Thring might have been deceived, for his friend was still arrayed in his Oriental costume.

"Bless my heart if you ain't right, and that's Mr. Villiers hisself!" sang out Lobb, on hearing the young middy's exclamation. "How in the name of wonder did——" And, without finishing his sentence, the coxswain snatched up an Arab musket which he knew to be loaded.

"The swabs have knocked him over, and may be a-murderin' of 'im!" he cried, in horrified tones.

But Thring made a dash at the long barrel. "Don't fire at them, Lobb; you might hit poor Jack."

The seaman lowered the gun. "I could pick off any one of the warmints if I had a mind to," he said; "leastways, if this was a Martini-Henry I had in my fist; but by ill fortin it ain't."

Thring stamped on the deck in despair, as he watched with agonised glances his helpless chum being borne away into the interior, accompanied by about a score of escaped slaves.

His duty was plain, however. He recognised that at once. An immediate return to the "Forte" to report matters was imperative, and there were some wounded men—both sailors and Arabs—to attend to. Ahmed, as we know, had lost his life, and the same fate had overtaken one of his principal followers. Several of the cutter's crew were suffering from wounds, but fortunately none of them were serious.

It was necessary to leave a small guard on board the dhow, and Thring was about to step into the cutter with his reduced crew when it was reported to him that the "Forte's" pinnace was approaching. Captain Brooke, having observed the dhow's mast, and that the cutter had gone—as he thought—to reconnoitre, very promptly sent away one of his largest boats, containing a score of armed men, under command of the gunnery lieutenant.

"This is a very serious matter," exclaimed that officer when he had heard the middy's story. "Thank God your friend is alive, and I trust we may yet see him aboard safe and sound. There is not a moment to lose, however, and we must return instantly to the ship and report matters to the captain. I'll put half a dozen additional men aboard the slaver, and then we'll sheer off."

Captain Brooke looked very grave when he heard the extraordinary news brought by the two officers. The glad intelligence that Jack Villiers was alive spread like wildfire throughout the ship, and everyone, fore and aft, was burning to join in an expedition to effect his release.

The captain hoped that the Arabs would come off and treat for the release of the prisoner, and to this end—through the ship's interpreter—several parleys were held with the Arab captives, who, evidently in terror of their lives, protested stoutly that no Englishman had been on board the dhow at all, and that Thring and his boat's crew must have been mistaken in thinking they had seen such a person. In despair at their obstinacy, Captain Brooke ordered the prisoners to be released and put on shore, with a parting and most emphatic reminder that if a hair of the missing midshipman's head was hurt they would all eventually be recaptured and hanged at the yard-arm.

Several parleys were held with the Arab captives.

Meanwhile energetic preparations were going on for fitting out an expedition. Every available boat was manned and armed, and the little naval brigade, consisting of a hundred bluejackets and twenty marines, was placed under the command of the gunnery lieutenant, Mr. Howard. All the necessary arrangements, however, took some time, especially as the steam-launch had to be hoisted out and fitted for active service. Captain Brooke did not regret the delay, as he still hoped that his warnings to the released Arab prisoners would have effect, and that Jack would be held to ransom without loss of time. In this, however, he was doomed to disappointment, for no messenger bearing the olive-branch of peace arrived upon the scene.

The sun was now descending swiftly into his cloudy bed in the radiant west, and, as there is scarcely any twilight in the tropic zone, the officers of the "Forte" recognised that it would be impossible for the expedition to start before the following morning. It was known, of course, that only three armed Arabs had formed Jack Villiers's escort; but, for all that was known to the contrary, these men might easily induce some of the warlike Somalis to join them and assist in forming ambushes or other devices of guerilla warfare.

There were two prime difficulties which presented themselves to Captain Brooke's mind. The first and most important was that the Arabs, incensed at being pursued, might put Jack to death out of pure spite; and the second was that it was impossible to tell in which direction the fugitives had gone, as nothing had been seen of them since the cutter's crew had observed them clambering up the acclivities of Ras Joo-joo like so many startled deer pursued by a leopard.

Dawn broke in a clear cloudless sky. The "Forte," now anchored in the bay, appeared to be lying in a tranquil lake, unruffled by the lightest catspaw. The bleak and barren-looking shores appeared to be deserted. Not a human being was visible on strand or cliff, although the signalmen repeatedly swept them with their powerful telescopes.

It was necessary to take action, and that promptly.

The naval brigade was mustered, and then drafted into the boats. Every man was armed with a rifle and cutlass, the petty-officers being supplied with revolvers as well. Thring, as a friend of the kidnapped midshipman, was allowed to accompany the force, much to his own satisfaction.

The steam-launch took the little flotilla in tow, and, with her engines going full speed ahead, steered for the mouth of the Joo-joo river, where it was proposed to disembark the force. No field-guns were taken, owing to the nature of the country, but the launch had a seven-pounder mounted in her bows in case it should be necessary to disperse any body of natives that might assemble to dispute the landing—a not very probable contingency.

As the estuary of the river was opened out, two small canoes were observed upon its waters, the occupants of which were apparently engaged in fishing.

Young Thring was in the launch with the gunnery lieutenant, actively at work with his telescope.

"There's your dhow safe enough at anchor," observed Mr. Howard; "but I wonder what those fellows are up to in the canoes."

"Perhaps they're spies, sir," said the middy.

"We must make prisoners of them in any case. It is just possible that we may be able to wring some information out of the fellows if they are inhabitants of the country."

The boats having been cast off, the gig was ordered to immediately seize the two canoes, the natives in which were now paddling away up-stream in evident alarm. They were quickly captured, however, and brought on board the launch, where they stood before the lieutenant trembling in every limb.

Through the interpreter, who understood all the dialects of the coast, Mr. Howard cross-examined the men, who proved to be members of the Somali tribe, and genuine fishermen. On the promise of a large reward if their information should prove correct, these fellows spun a long yarn, some items of which proved to be of great importance.

It appeared that they had seen Jack Villiers carried away up-country, and out of curiosity had followed in the track of the fugitives—a white prisoner being a very uncommon sight on their coast. They soon perceived that the Arabs were not unacquainted with the country, for they made straight for a large, rudely-fortified village situated on the left bank of the river, and some ten miles from its mouth. This settlement was ruled over by a petty chief of warlike tastes, who often made cruel and utterly unprovoked raids upon his neighbours.

The fishermen went on to relate that they saw the Arabs and the escaped slaves enter this village, and that they felt sure the chief had received them amicably. They themselves had not dared to approach any nearer, but had slunk off to their own home, a mere hovel on the banks of the stream; nor had they seen or heard anything more of the prisoner or his captors.

This news—if trustworthy—was of enormous importance, for it located the whereabouts of the fugitives. The lieutenant gave it as his opinion that the chief in question had probably been a friend and ally of Ahmed's in former days, and that the news of that slave-dealer's death would probably exasperate him very much against all Englishmen, and decide him to assist the Arabs with all his armed forces.

The fishermen, on being asked if they would consent to act as guides, willingly agreed to do so; and, as the river was too shallow to allow of the boats proceeding up-stream, the naval contingent was landed at a convenient spot on the left bank, and quickly formed up for an advance. The country here was fortunately open and fairly level; and, though there was no road, the ground was firm under the men's feet, and not obstructed by scrub or jungle. The only signs of vegetation were a few mangrove-bushes that lined the banks of the muddy, sluggish stream, and an occasional clump of lofty bamboos.

The officers were of opinion that the fishermen were speaking the truth, but every precaution was taken to guard against treachery by throwing out scouts and an advanced line of skirmishers.

The excitement of action enabled Thring to keep up his spirits to a certain extent, but he had a terrible foreboding that the treacherous Arabs would not scruple to murder his chum should it suit their purpose to do so. Certainly there were some grounds for his fears. The little middy felt as if he had lived a lifetime in the last few days, so great had been the tension.

As far as possible the brigade followed the course of the river, which was not a sinuous one, its turbid current flowing evenly between oozy mudbanks, whereon an occasional crocodile was seen basking in the hot rays of the tropic sun. These repellent reptiles slid off almost noiselessly into the water on viewing the approach of human beings.

Every moment—early as it was—the heat grew more intense, and a veritable plague of flies attacked the men on the march; but the gallant fellows made light of all these annoyances, and joked and laughed like a lot of light-hearted schoolboys out for a picnic. The idea that the kidnapped middy might be cruelly murdered did not occur to them. As Lobb confided to one of his cronies: "In course there'll be a bit of a scrimmage, mate, and then we'll have the young gentleman back amongst us as right as a trivet, d'ye see?"

After an arduous forced march of three hours or so, the village was reported to be in sight, and every heart beat high with expectation. A considerable détour had been made in the last three miles, so as, if possible, to enable the force to make an attack upon the village in the rear, and also for the purpose of avoiding some patches of forest near the river. Several natives had been seen making their way rapidly in the direction of the settlement, and there could be no doubt that they would give the alarm to those within the rude but strong palisades that formed the warlike chief's principal line of defence.

A halt was called under the shade of some trees, and the officers conferred together for a few moments.

A loud jabbering, mingled with shouts of both defiance and alarm, now rang out from the village. Children screamed, dogs barked, cocks crew, and goats bleated, and it was evident enough that any idea of taking the place by surprise must be abandoned.

Rapidly the naval brigade formed into line and, with the officers leading, charged forward at the double. The men had orders not to cheer or to fire a shot until they were close to the palisades, which latter enclosed the village on every side except that which opened upon the river. Extending beyond these stockades were stretches of cultivated ground, containing crops of maize, sweet potatoes, melons, and tomatoes. There was absolutely no cover for the attacking force, a few guava-trees and clumps of cacti being the only break in the uniformity of the ground—an unfortunate circumstance.

As the bluejackets and marines swept forward to the attack, it became evident that the defenders had loopholes for firearms in their palisades, for a brisk fire was opened at different points upon the advancing brigade, and several men fell out of the ranks wounded; for, though most of the bullets flew high, a few found their billets accurately enough. The ambulance corps at once conveyed these poor fellows to the rear, where the surgeons were in attendance to dress their hurts.

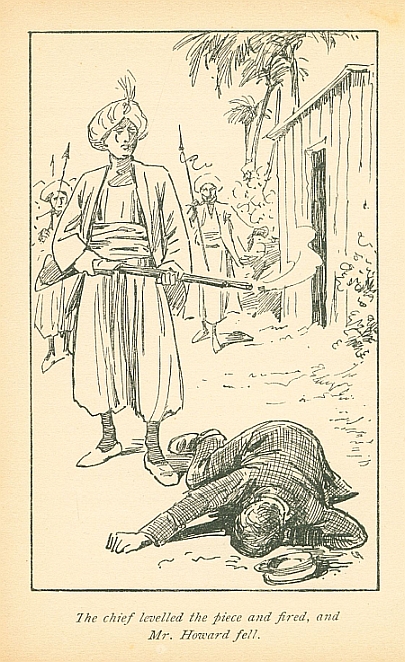

The chief levelled the piece and fired, and Mr. Howard fell.

It was clear that there would be a desperate attempt on the part of the garrison to roll back the charging line of stormers, for in addition to the sharpshooters—who were but few in number—a large posse of warriors could be observed assembling just within the stockades, evidently mounted on platforms erected for the purpose. The rays of the sun flashed brightly on the spears, swords, and hatchets which these fellows bore, and lit up their savage countenances and wild fluttering turbans with weird effect.

Close to a strongly-barricaded gateway on the northern side of the line of defences two or three banners were lazily flaunting in the gentle breeze, and near this spot stood the chief, Sooltan Shah, himself, surrounded by his chief advisers and the three Arabs who had acted as Jack Villiers's escort.

Sooltan Shah was a powerfully-built man of middle age, and his clean-shaven tattooed face bore a mingled expression of cruelty and pride strongly stamped upon it. A large scar reaching from his right eye to the corner of the mouth, and a slight cast in one eye, lent the whole face a ferocious and sinister look which disagreeably impressed everyone who gazed upon it.

As I mentioned before, this individual had been on very friendly terms with the dead slaver-captain, and his wrath had been greatly aroused by the news that the little residue of Arabs had brought him.

"The dogs are brave," he said to his counsellors, as he admiringly watched the charge of the naval brigade; "but they'll never swarm over my palisades. If they do, my trusty warriors will wet their spears in the blood of my foemen, and their bodies shall be cast to the vultures."

As he finished speaking, the thin white line halted and poured in a volley at close range. Then it swept forward again, a ringing British cheer from over a hundred throats rushing out like a blast from amid the rolling battle smoke.

Two bullets rang by close to Sooltan Shah's gaudy and voluminous turban, and one of the Arabs standing close beside him sprang three feet into the air and fell dead at the chief's feet—shot through the heart. Sooltan's face was convulsed with passion. Seizing a musket, the butt of which was inlaid with ivory, from one of his attendants, he levelled it at the gunnery lieutenant and fired. The slug struck the ground a couple of feet in front of the officer.

"Give me another musket," roared the chief; "my second shot is always a deadly one."

Again he levelled the piece and fired. Mr. Howard fell, his drawn sword flying from his grasp.

"One chieftain has bitten the dust, ha! ha!" exclaimed Sooltan, with savage glee. "Now is Ahmed's death avenged, and we shall see these white men fleeing before us like a herd of gemsbok before a hungry lion."

"Some of the dogs are beneath the gateway. Shoot them down!" cried one of the Arabs excitedly.

Scarcely had the words escaped his lips than a terrific explosion rent the air, and chocks of timber, stones, and dust were hurled upwards with great force. Sooltan and those standing around him were thrown violently to the ground, and a shower of debris fell around them. A strong odour of gunpowder filled the air, and volumes of grey smoke slowly drifted away on the wind.

A detachment of seamen-gunners had blown up the barricaded gateway, and thus created a wide gap, through which a party of stormers swept in to the attack with ringing cheers.

Sooltan Shah had only been partially stunned. The desperate courage of the man asserted itself in spite of the rude awakening he had received. Seizing a weighty spear, he rapidly thundered out some orders to those around him, and then, with hasty steps and a lowering brow, rushed down at the head of his men to endeavour to stem the onward rush of the "Forte's" men.

Meanwhile other mines had been sprung, and at several points the active sailors were seen swarming over the stockades like a troop of wild cats. Some of these, however, were shot down and others wounded by the long spears of the natives.

Young Thring, brave, cool, and collected amidst all the turmoil of this hand-to-hand fight, was one of the first to enter the village, and, with the aid of a body of veteran seamen, drove the line of defenders—still fighting desperately—backwards into the narrow lanes that divided the rows of beehive huts one from the other. The middy had asked the interpreter to keep close to him, that he might be enabled to question some of the prisoners as to the whereabouts of Jack Villiers, whom he hoped to rescue alive out of the hands of his ruthless captors—if, indeed, the poor fellow had not already perished by the hands of an assassin.

As the middy and his men pushed on, the resistance of the villagers grew feebler and feebler, and at length ceased altogether. In answer to the queries of the interpreter, one of the prisoners asserted that he knew well the hut in which Jack Villiers had been confined, and would guide the victors to it. With a terrible anxiety gnawing at his heart, Thring marched on rapidly with his men, and quickly arrived before the hut which had been used as a prison.

It was deserted and empty, and there were unmistakeable bloodstains upon the earthen floor.

When our mid of the maintop was hurried ashore from the dhow in the Joo-joo river, he had no idea that a man-of-war was in the offing, and that one of her boats was about to board the slaver.

The sounds of the conflict were heard somewhat indistinctly in the cave in which the three Arabs and the middy had taken refuge, but Jack felt with a sudden exaltation of spirits that it was probable that a British boat had arrived upon the scene, and that his immediate release might be reasonably expected.

Sadly were his hopes dashed to the ground when, with his arms bound behind him, he was hurried out of the cave and up the cliffs by his guards. One glance at the dhow beneath him showed our hero that there were British bluejackets on board, although in the confusion of the moment he did not recognise Thring or any of the cutter's crew.

One wild cry burst from the unhappy boy's lips. The next moment he was struck to the ground by his relentless captors, gagged with a piece of cotton cloth, and then forcibly borne away up-country in a state of semi-consciousness, from which he did not fully recover till he found himself cast—released from his gag, but bound and helpless—into a small beehive hut in Sooltan Shah's stockaded village.

A whirl of conflicting thoughts passed through the poor boy's mind, and for the first time since his rescue from the waves did it occur to him that his captors might take it into their heads to end his existence and their own responsibility at the same time.

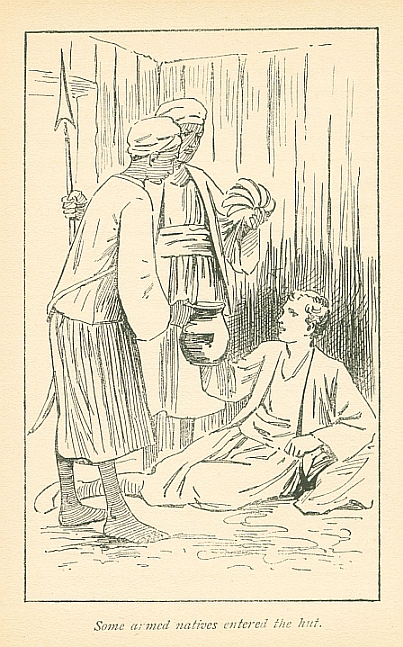

Some armed natives entered the hut.

The possibility of this ending to his adventure struck a chill to the midshipman's brave young heart, but his family motto happened to be "Nil desperandum," and he had never yet, in his short career, failed to act up to it. Indeed, a braver or more resourceful boy than Jack Villiers it would be difficult to find, even in that nursery of heroes, Her Majesty's Royal Navy.

Therefore the middy soon plucked up his spirits and began to turn over some problems in his mind—problems of escape from durance vile.

"I'd give anything to know," muttered Jack to himself, "whether those bluejackets on board the dhow recognised me as an Englishman or not. In this rig they might easily have taken me for an Oriental, for some of these Arabs are as fair as a European. I wonder what cruiser they belonged to? Could they have been some of my own shipmates? What luck if they were! Even then, however, the skipper might think it too risky to send an expedition up-country. He would probably try and treat with the beggars instead, and meanwhile I may have a knife stuck into me."

The middy was almost in complete darkness, for there was no window to the hut, and when his guards had thrown him down upon the earthen floor they had gone outside to mount guard, shutting the palm-leaf door behind them and carefully securing it. A few straggling rays of light came in through chinks here and there, but they could not disperse the depressing gloom of the interior.

Jack's head ached: the effects of the blow the Arabs had dealt him, coupled with the long march under the almost intolerable rays of a vertical sun; and for a time his thoughts did not take a very definite shape.

About an hour after his arrival in the village, some armed natives, in no way resembling the Arabs, entered the hut, bearing a small bunch of bananas and an earthenware pitcher containing goats' milk. These they placed on the floor beside the prisoner, removed the lashing from his arms, and then without a word glided outside and resumed their vigilant watch and ward.

"I'm glad they haven't forgotten the grub," said Jack to himself; "for when one is down in the mouth one wants to be figged up a bit."

After munching a few bananas and taking a good long pull at the pitcher our hero felt more himself, and was thankful to get his arms free for a short time, for the numerous turns of rope had made them very stiff and uncomfortable.

The guards re-entered, replaced the lashing with almost brutal force, and then withdrew again.

"No, I've not forgotten the dodge those fellows at Guildford Fair taught me," muttered Jack, who had been lost in profound thought for some minutes, "and I really believe I could get my arms free if I wanted to. Then if I only had a knife or some sort of tool it might be possible to hack one's way through these flimsy walls, which are only made of dried palm-leaves or something of that sort."

The day wore on, and at length night fell—a still, balmy night, with a sky scintillating with a million flashing stars.

A scanty supper of boiled rice and salt fish was served to the prisoner, and then the guards left him stretched upon the ground for the night, securely bound—or so they thought, having never had the opportunity of attending Guildford Fair and being initiated into its mysteries!

The exhibits at the Surrey county-town usually included a "strongman" who could shake himself free from any entanglement of rope, however cunningly knotted around him. In exchange for a sovereign, and a promise never to reveal the secret to anyone else, our hero had been shown the trick. There was no fraud or jugglery about the matter. When you know the way it is as simple as ABC, but then every schoolboy has not a sovereign to spare for this sort of thing, has he?

No sooner did Jack find himself left alone for the night than he proceeded without loss of time to put his plan of escape into execution.

I am not going to tell you how the rope lashings were cast off, for the simple reason that I do not know, for Jack is a boy of honour, and I have never been able to get him to divulge the secret, even to me—his own father.

Suffice it to say, however, that in ten minutes' time our hero had succeeded in getting his arms free; and his first act was to stealthily grope about in every corner of the dark hut in the hope of finding some object that might be of use to him in the endeavour to bore through the leafy walls of his prison-house.

The only thing the middy found, however, was a shell shaped like a scallop. There was absolutely nothing else lying about.

"This won't do," said Jack to himself; "one can't cut with this blunt thing, and even if one could, the noise would be sure to arouse those beggars of sentries outside. I didn't think of that before."

Our hero felt bitterly disappointed. Then a sudden thought flashed through his mind, and he crept to the back of the hut and began softly but quickly digging a hole in the earthen floor, close up to the wall, with his newly-found treasure, the shell. The soil proved light and sandy, and with such ceaseless energy did the prisoner work that in an hour's time he had excavated a hole sufficiently large to allow of his body passing through.

The next moment Jack was lying flat on the ground outside the hut, listening intently. He could hear the sentries jabbering near the doorway, but apparently he was free to steal away from the back without being perceived, unless there happened to be any of the inhabitants of the village abroad.

Congratulating himself on his good fortune, our hero moved stealthily forward and gained a small grove of guava-trees, where for a few moments he paused. Then, making a sudden resolve, he ran swiftly away and disappeared over the brow of a hill in the direction of the river.

Not ten minutes after this the guards entered the hut and instantly saw that their prey had escaped. Fearful of the fate that awaited them when Sooltan Shah learnt the news of the flight of the captive, the warriors, six in number, hurriedly set off in pursuit of the fugitive, having agreed among themselves that no alarm should be given unless the chase proved a futile one.

* * * * *

In spite of the complete victory they had achieved, ending in the death of Sooltan and the surrender of his warriors, the seamen and marines returned to the mouth of the Joo-joo river with heavy hearts. The corpse of Jack Villiers had not been discovered, in spite of the most strenuous search, but every member of the force believed him to have been most foully murdered. More especially was young Thring downcast and broken-spirited, for the bonds of friendship had been very strong between the two boys.

There was one subject for congratulation, and that was that the gunnery lieutenant, who had been struck down by the African chief's bullet, was likely to recover from the wound in the thigh which he had received.

The "Forte's" boats had been left at anchor in the river under command of the boatswain, with orders to await events. When the naval brigade hove in sight, the flotilla moved in to facilitate the operation of embarking the men, many of whom were more or less badly wounded.

Is it possible to understand young Thring's astonishment and joy when, to his utter amazement, he saw, standing beside the boatswain in the stern-sheets of the launch, and energetically waving a turban over his head, his dearly-loved chum and messmate, Jack Villiers?

What a resounding cheer went up from the whole throng of seamen and marines, who, breaking loose from all the bonds of discipline, rushed down to the river's brink, frantically throwing their caps up in the air, and generally behaving like a lot of schoolboys to whom an extra week's holidays had just been granted!

In another moment Thring was wringing his friend's hand as if he was particularly anxious to dislocate the fingers, and both boys began to chatter like excited magpies.

"Yes, yes, and after you got clear of the village, and you found you were being hunted down by the sentries, what happened then?" demanded Thring, with breathless interest.

"Well, I knew jolly well I hadn't a chance with the beggars at running," said the mid of the maintop modestly, "and so after a bit, when I found they were catching me up hand-over-fist, and I was jolly well losing my wind, I just swarmed up a dense tree that overhung the banks of the river, and stowed myself away amongst the thickest branches—just like Charles II. in the Boscobel oak! I'm certain the beggars knew I was up a tree, but, owing to the darkness and the thickness of this patch of jungle, they never found me. For a long time after daylight I could hear the shouts and cries of natives, and did not dare to descend. Then a long silence ensued, but I still lay low, thinking it might be a trap set for me; but I believe now that the news of your advance upon their village had reached them, compelling them to go back and assist in its defence. After waiting a long time, I concluded that the coast was clear, and went down the tree like a shot. Following the river, I discovered by great good luck a canoe made fast amongst some thick reeds. There were paddles on board, and I hopped in like a house on fire and sculled down the river as if all the hippopotami and alligators in Africa were after me! I needn't spin you the rest of the yarn, for here I am safe and sound and as fit as a fiddle!"

"But how about them there bloodstains on the floor of the hut you were imprisoned in, sir?" queried a sceptical old quartermaster standing by; "and I didn't see no hole dug under the wall abaft, not so much as a bread-room rat could creep through."

Thring explained briefly to his chum what had been seen during the occupation of the village. Jack laughed heartily.

"It's evident that native prisoner was laughing in his sleeve at you," he said, "and took you to a house where they had been killing some fowls. You always were rather green, Thring, old chap, weren't you? I say, what an adventure this'll be to tell the mater, won't it?"