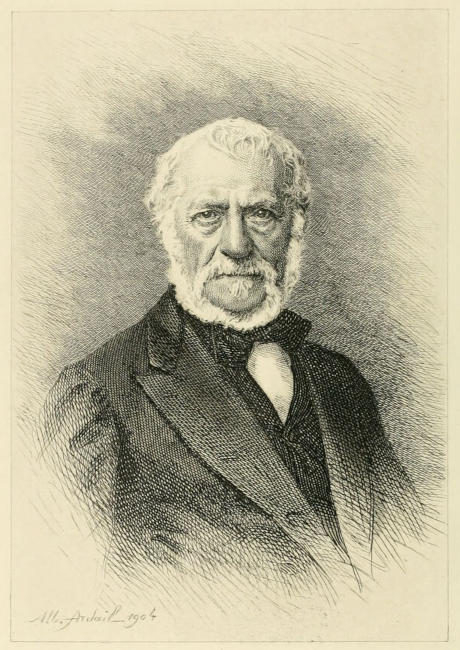

MARTIN

Title: The historians' history of the world in twenty-five volumes, volume 11

France, 843-1715

Editor: Henry Smith Williams

Release date: October 14, 2025 [eBook #77058]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: The Outlook Company, 1905

Credits: David Edwards and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: As a result of editorial shortcomings in the original, some reference letters in the text don’t have matching entries in the reference-lists, and vice versa.

[i]

[ii]

[iii]

MARTIN

[iv]

[v]

THE HISTORIANS’

HISTORY

OF THE WORLD

A comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations

as recorded by over two thousand of the great writers of

all ages: edited, with the assistance of a distinguished

board of advisers and contributors,

by

HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS, LL.D.

IN TWENTY-FIVE VOLUMES

VOLUME XI—FRANCE, 843-1715

The Outlook Company

New York

The History Association

London

1905

[vi]

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

Press of J. J. Little & Co.

New York, U. S. A.

[vii]

[viii]

[ix]

| VOLUME XI | |

| FRANCE | |

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Later Carlovingians (843-987 A.D.) | 1 |

| Charles the Bald, 1. The Northmen, 2. Edict of Mersen, 3. The Northmen’s allies, 4. Beginning of the great fiefs, 5. Edicts of Pistes and Quierzy, 6. Louis II to Carloman, 7. Charles the Fat, king and emperor, 8. The feudal régime, 10. The church, 13. Capetians and Carlovingians, 14. The last Carlovingians, 17. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Foundation of the Capetian Dynasty (987-1180 A.D.) | 22 |

| Henry I, 24. Deeds of the great barons, 26. Philip I, 27. Louis the Fat and Louis the Young, 30. Battle of Brenneville, 31. The abbot Suger, 34. Emancipatory movements after the Crusades, 38. The communes, 38. Philosophy and thought; Abelard and St. Bernard, 40. Abelard and the university, 44. The position of woman, 45. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Development of the Absolute Monarchy (1180-1270 A.D.) | 47 |

| Prince Arthur of Brittany, 49. The Albigensian Crusade, 51. League against Philip Augustus, 54. The battle of Bouvines, 54. Last years and influence of Philip Augustus, 56. Louis VIII, 56. Louis IX, called St. Louis, 58. First Crusade of St. Louis, 60. Last years and death of St. Louis, 61. Hallam’s estimate of St. Louis, 63. Piety and christianity of St. Louis, 64. Progress of the monarchy under St. Louis, 67. Aspects of thirteenth-century civilisation, 71. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Philip III to the House of Valois (1270-1328 A.D.) | 74 |

| Philip (III) the Bold, 74. Philip (IV) the Fair, 75. New war with Flanders, 76. The quarrel between Philip and Boniface VIII, 77. Sentence of the Templars, 83. Philip’s fiscal policy, 84. Execution of Jacques de Molay, 85. Political progress in Philip’s reign, 87. Louis (X) the Quarrelsome, 89. Philip (V) the Tall, 91. Charles (IV) the Fair, 92. Aspects of civilisation, 93. The great fairs, 95.[x] | |

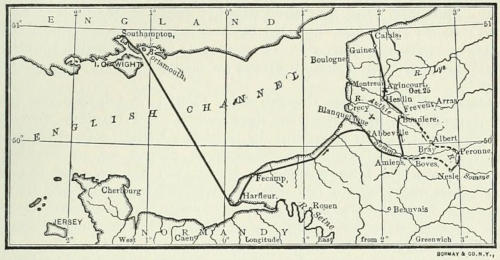

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Opening of the Hundred Years’ War (1328-1350 A.D.) | 98 |

| Edward III claims the throne of France, 103. The battle of Sluys or L’Écluse, 104. The war in Brittany, 107. Joan de Montfort defends Hennebon, 108. Philip’s financial difficulties, 110. Renewal of the war with England, 111. Edward returns to France, 112. Froissart’s description of Crécy, 114. Michelet on the results of Crécy, 118. The siege of Calais, 119. Suspension of the war, 121. Territorial acquisition, 122. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| John the Good and Charles the Wise (1350-1380 A.D.) | 124 |

| Trouble with Charles of Navarre, 126. The states-general of 1355, 128. The battle of Poitiers, 130. The states-general of 1356-1357, 132. The dauphin repudiates the Grande Ordonnance, 134. The Jacquerie, 135. Death of Marcel, 137. Peace negotiations; Edward in France, 138. The story of Le Grand Ferré, 139. The Treaty of Bretigny, 141. The last years of King John, 142. Charles the Wise, 143. Early exploits of Bertrand du Guesclin, 144. End of the Breton War; battle of Auray, 146. Du Guesclin leads the free companies into Castile, 147. The Peace of Bretigny is broken, 149. The English invasion, 150. Last years of Charles V and of Du Guesclin, 152. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Betrayal of the Kingdom (1380-1422 A.D.) | 155 |

| War in Flanders; battle of Roosebeke, 156. Insurrections in Paris and Rouen, 157. The King assumes the rule, 159. Hatred of the nobles for the ministry, 162. The king goes mad: the princes return to power, 163. Domestic troubles and scandals, 165. Civil war, 167. Henry V invades France; a French view, 169. Michelet’s account of the battle of Agincourt, 170. Massacre of the Armagnacs in Paris, 174. The duke of Burgundy master of Paris, 175. Siege of Rouen, 176. Henry and John the Fearless, 177. The Treaty of Troyes, 178. Henry’s struggle with the dauphin, 180. Woes of the people; the Danse Macabre, 182. The University of Paris and the council of Constance, 184. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Rescue of the Realm (1422-1431 A.D.) | 187 |

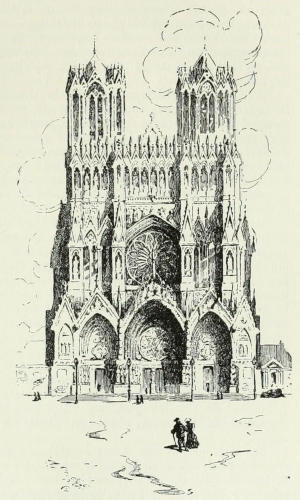

| Monstrelet describes the siege of Montargis, 189. The siege of Orleans, 190. The “battle of the Herrings,” 191. The Maid of Orleans (La Pucelle), 194. Joan at the court, 196. The deliverance of Orleans, 198. Joan of Arc leads the king to Rheims, 200. Joan defeated at Paris, 203. Capture of Joan of Arc, 204. Trial of Joan of Arc, 206. The Twelve Articles, 207. The findings of the faculty, 211. The sentence and its execution, 213. The rehabilitation of Joan of Arc, 218. The British estimate of Joan’s services, 219.[xi] | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| “The Convalescence of France” (1431-1461 A.D.) | 220 |

| The Treaty of Arras, 222. The French return to Paris, 224. The Pragmatic Sanction, 225. The atrocious crimes of the barons, 226. Gilles de Retz, 226. Charles begins the work of reform, 228. Agnes Sorel; the Praguerie, 230. Effective progress against England, 233. Expedition to Switzerland and Lorraine, 235. The battle of Sankt Jakob, 236. Military and financial reforms, 236. The close of the Hundred Years’ War, 238. The battle of Castillon, 239. The last years of Charles VII, 242. Quarrels with Burgundy and with the dauphin, 242. Death of Charles VII; the influence of his reign, 244. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The Reign of Louis XI: The Triumph of the Crown (1461-1483 A.D.) | 247 |

| Relations with the Church, 249. The war of the Public Weal, 250. The battle of Montlhéry and the Treaty of Conflans, 250. Political intrigues, 253. The struggle with Charles the Bold, 254. Comines describes the visit to Péronne, 255. The storming of Liège, 259. The return of Louis to France, 262. Edward IV of England aids Charles the Bold, 263. Gold and diplomacy make Louis the victor, 265. Last deeds of Charles the Bold, 266. Mary of Burgundy, 268. War with Maximilian, 270. Last years and death of Louis, 272. Martin’s estimate of Louis XI, 274. Louis’ influence on civilisation, 275. Establishment of posts in France, 275. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Charles VIII and Louis XII—The Invasion of Italy (1483-1515 A.D.) | 278 |

| Charles VIII, 278. The rule of Anne de Beaujeu, 279. The struggle with the duke of Orleans, 284. Charles VIII in Italy, 288. Death of Charles VIII, 293. Louis XII, “the father of his people,” 293. Marriage with Anne of Brittany, 295. Foreign affairs, 297. Internal affairs, 302. Last years of Louis XII, 304. | |

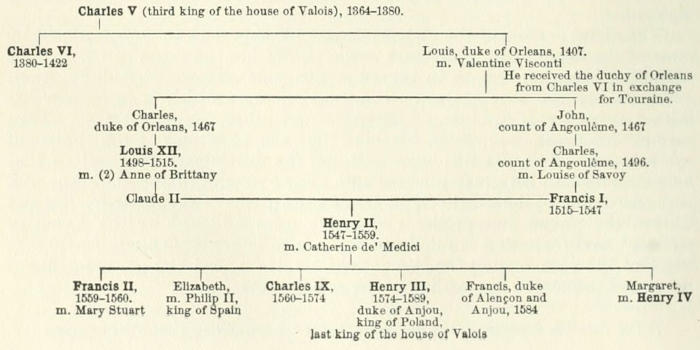

| CHAPTER XII | |

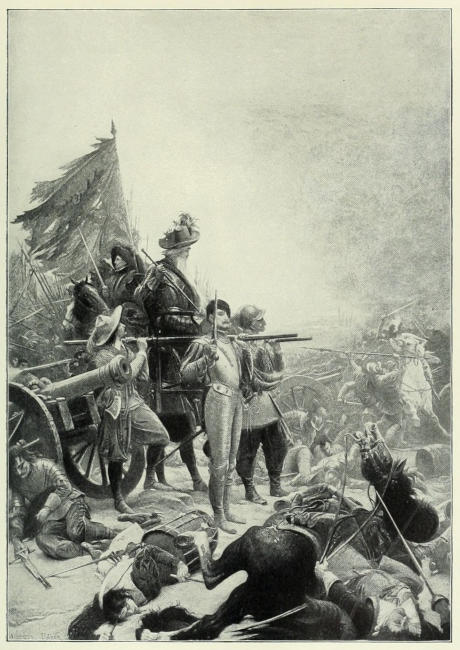

| Imperial Struggles of Francis I and Henry II (1515-1559 A.D.) | 306 |

| Critical survey of Francis I and his period, 306. A brilliant campaign in Italy, 308. The Concordat, 309. Strife between Francis I and Charles V, 310. Meeting of Henry VIII and Francis I on the Field of the Cloth of Gold, 311. Francis I and Charles V at war, 313. Defection of the duke de Bourbon, 314. A disastrous campaign in Italy; the battle of Pavia, 316. Francis captive in Spain; the Treaty of Madrid, 320. Further dissensions and the “Ladies’ Peace,” 322. Internal affairs, 325. The French Renaissance, 328. War again between Francis I and Charles V, 332. Last years and death of Francis I, 335. Gaillard’s estimate of Francis I, 336. Character and policy of Henry II, 337. Court favourites, 338. Religious persecutions and royal marriages, 339. War with Charles V and his successor, 342. The siege of Metz, 343. Minor engagements; the abdication of Charles V, 346. Battle and defence of St. Quentin, 347. The retaking of Calais, 347. The Treaty of Câteau-Cambrésis, 348. The last days of Henry II, 349.[xii] | |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Catherine de Medici and the Religious Wars (1559-1589 A.D.) | 351 |

| Francis II, 352. Religious parties, 353. Death of Francis II, 355. The accession of Charles IX, 356. Civil war, 357. The Edict of Amboise and its results, 359. The Second Religious War, 361. The Third Religious War, 362. Admiral Coligny; the Peace of St. Germain, 364. A troubled peace; the marriage of Henry of Navarre, 365. The attack on Coligny, 368. Preparing for the massacre, 370. The Massacre of St. Bartholomew, 374. Effects of the massacre, 376. Last years, death, and character of Charles IX, 378. The accession of Henry III, 380. Political conditions, 381. The Holy League, 383. The war of the Three Henrys, 384. The battle of Coutras, 386. The Day of the Barricades and the Treaty of Union, 388. The meeting of the states-general, 388. The assassination of Henry, duke of Guise, 390. Death of Catherine de Medici, 392. The siege of Paris and the death of Henry III, 392. | |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Henry of Navarre, First of the Bourbons (1589-1610 A.D.) | 395 |

| Henry’s struggle for the crown, 395. The battle of Ivry, 397. The duke of Parma and the Spaniards, 400. Henry IV and the league, 401. Opposition of the pope and Philip II, 404. The Edict of Nantes, 405. Reorganisation of France with the aid of Sully, 407. Amours and second marriage of Henry IV, 409. Intrigues of De Biron, 412. The last years of Henry’s reign, 414. Grand design of Henry IV; his death, 415. Character and policy of Henry IV, 417. Martin’s estimate of Henry IV, 418. Stephen’s characterisation of Henry IV and his times, 419. | |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| The Literary Progress of France in the Sixteenth Century | 422 |

| Calvin, 426. Montaigne, 427. | |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| The Early Years of Louis XIII and the Rise of Richelieu (1610-1628 A.D.) | 432 |

| The regency of Marie de Medici, 432. Disgrace of Sully, 434. First revolt of the lords, 434. Last assembly of the states-general, 436. Majority of Louis XIII; marriage with Anne of Austria, 438. Richelieu appears, 438. Assassination of Marshal d’Ancre, 441. The ministry of Luynes, 443. The Huguenot uprising; the siege of Montauban, 445. Death of Luynes, 448. Richelieu’s return to the ministry, 449. Conspiracy of the court against Richelieu, 450. The siege of La Rochelle described by Seignobos, 452.[xiii] | |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| The Dictatorship of Richelieu (1629-1643 A.D.) | 457 |

| Richelieu and the king, 458. Richelieu enters the European arena, 460. Enmity of Marie de’ Medici against Richelieu, 462. The Day of Dupes, 462. Exile of Marie de’ Medici, 464. The revolt of Gaston and the execution of Montmorency, 465. Foreign affairs, 466. Wars with Austria, 468. Attempt to assassinate the cardinal, 469. Character of Louis, 470. Revolt of the count de Soissons, 472. Caillet’s estimate of the administration of Richelieu, 472. The church and the state under Richelieu, 475. The conspiracy of Cinq-Mars, 478. Recovery and triumph of Richelieu, 480. The last days of Richelieu, 482. Stephen’s estimate of Louis XIII and of Richelieu, 484. | |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| The Supremacy of Mazarin (1643-1661 A.D.) | 487 |

| Battle of Rocroi, 489. The importants, 491. The education of the young king, 493. Military glory, 494. Treaty of Westphalia, 496. Mazarin’s domestic policy, 497. First insurrection of the Fronde, 499. The Day of the Barricades, 500. Second act of the Fronde; arrest of Condé, 505. Resistance of Bordeaux, 506. Disgrace and exile of Mazarin, 507. Condé in power, 508. Return of Mazarin, 509. The last phase of the Fronde, 511. Battle of St. Antoine, 513. Second exile of Mazarin, 513. Mazarin again in power, 515. War with Spain continues, 516. Alliance with Cromwell; war in Flanders, 517. The Treaty of the Pyrenees, 520. Last years and death of Mazarin, 522. | |

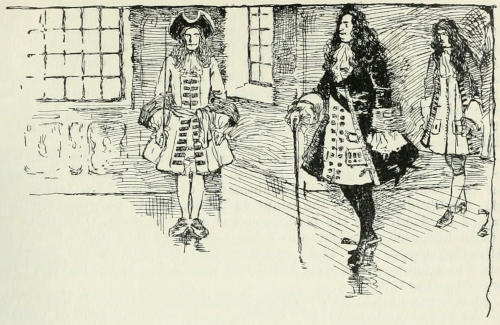

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| “L’ÉTAT, C’EST MOI” (1661-1715 A.D.) | 525 |

| The ministers, 528. The man with the Iron Mask, 531. The ministry of Colbert, 531. Reorganisation of the finances, 532. Michelet’s estimate of Colbert, 535. Louvois, 538. Vauban, 539. Séguier, legislative works, 540. Lionne, foreign affairs and diplomacy, 541. Triumph of the absolute monarchy, 541. Submission of Parliament, 542. Submission of the nobility, 543. The third estate, 543. Louis XIV and the church, 544. The Protestants, 545. Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, 546. The Jansenists, 548. The police, 549. The court of the grand monarch, 550. Mademoiselle de la Vallière, 551. Madame de Montespan, 555. Poisoning: the Brinvilliers case, 556. The retirement of Montespan, 558. Madame de Maintenon, 559. Effect of Louis XIV’s policy on the nation, 561. | |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| Louis XIV, Spain, and Holland (1661-1679 A.D.) | 563 |

| The war of the Queen’s Rights, 566. The Triple Alliance, 569. Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, 570. Projects against Holland, 571. The Treaty of Dover; death of Madame, 572. Treaties with other powers, 573. The war with Holland begins, 574. The passage of the Rhine, 575. The French in Holland and Germany, 576. The new coalition against France, 577. Defection of England and the imperial allies, 581. Operations in Franche-Comté; Turenne in Alsace, 581. Condé in the Netherlands, 584. Last campaigns of Turenne and Condé, 584. Events of 1676; affairs in Sicily, 585. Campaign of 1677; negotiations for peace, 587. Louis XIV settles with the coalition, 589.[xiv] | |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| The Height and Decline of the Bourbon Monarchy (1679-1715 A.D.) | 592 |

| Acquisition of frontier places, 593. Preparations for a second coalition, 596. Relations with Turks and Berbers, 598. Second coalition; the league of Augsburg, 599. The Revolution in England, 600. War of the league of Augsburg, 601. Attempts to restore James II, 601. Devastation of the Palatinate, 603. The war in Savoy and Piedmont, 604. The war in the Netherlands, 604. Steenkerke and Neerwinden, 605. Last years of the war; treaty with Savoy, 606. The Treaty of Ryswick, 608. Louis XIV and the Polish throne, 609. The question of the Spanish succession, 610. Accession of the Bourbons in Spain, 612. The Grand Alliance or third coalition against France, 613. War of the Spanish Succession; the French victories, 615. The camisards, 617. War of the Spanish Succession; French reverses, 617. The battle of Blenheim, 618. The battle of Ramillies, 620. The battle of Malplaquet, 624. The battle of Denain, 626. Treaties of Utrecht and Rastatt, 627. Death of Louis XIV, 629. | |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| The Age of Louis XIV: Aspects of its Civilisation (1610-1715 A.D.) | 632 |

| Foundation of the French Academy, 632. The patronage system, 633. Literary characteristics, 635. Science, 637. Poetry: Boileau, 640. Oratory: Bossuet, 641. The third period, 642. The drama; tragedy, 643. Corneille, 643. Racine, 644. Comedy, 645. Architecture, 647. Sculpture and painting, 648. Music and the opera, 650. Rapid decline of the age of Louis XIV, 651. A French view of the effect of the age, 651. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 653 |

PART XVI

THE HISTORY OF FRANCE

BASED CHIEFLY UPON THE FOLLOWING AUTHORITIES

A. ALISON, ALEXIS BELLOC, L. P. E. BIGNON, LOUIS BLANC, JULES CAILLET, J. B. R.

CAPEFIGUE, THOMAS CARLYLE, FRANÇOIS R. CHÂTEAUBRIAND, ADOLPHE

CHÉRUEL, JOHN WILSON CROKER, E. E. CROWE, C. DARESTE DE LA

CHAVANNE, BRUGIÈRE DE BARANTE, A. GRANIER DE CASSAGNAC,

PHILIP DE COMMINES, JURIEN DE LA GRAVIÈRE, LE COMTE DE

TOCQUEVILLE, JEHAN DE VAURIN, VICTOR DURUY, GABRIEL

HENRI GAILLARD, FRANÇOIS GUIZOT,

C. P. M. HAAS, ERNEST HAMEL, LUDWIG HÄUSSER, KARL HILLEBRAND, G. W.

KITCHIN, LACRETELLE, A. LAMARTINE, T. LAVALLÉE, P. E. LEVASSEUR, J.

MALLET-DUPAN, HENRI MARTIN, JULES MICHELET, F. A. MIGNET,

MONSTRELET, C. PELLETAN, VICTOR PIERRE, JULES QUICHERAT,

ALFRED RAMBAUD, J. E. ROBINET, DUC DE SAINT-SIMON,

J. R. SEELEY, C. SEIGNOBOS, J. C. S. DE SISMONDI,

ALBERT SOREL, H. M. STEPHENS, H. VON SYBEL,

H. TAINE, M. TERNAUX, A. THIERS,

F. AROUET DE VOLTAIRE

TOGETHER WITH AN ESSAY IN FOUR PARTS

THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL EVOLUTION OF FRANCE

BY

ALFRED RAMBAUD

WITH ADDITIONAL CITATIONS FROM

J. AMBERT, MARQUIS D’ARGENSON, A. ARNETH AND M. A. GEFFROY, JULES BARNI,

E. BERTIN, PAUL BONDOIS, A. BOUGÉART, M. N. BOUILLET, E. BOUTARIC,

H. T. BUCKLE, T. BURETTE. F. CANONGE, HIPPOLYTE CASTILLE, H.

CARNOT, SYMPHORIEN CHAMPIER, CHRONIQUE DE ST. DENIS,

CONTINUATOR OF GUILLAUME DE NANGIS, OLIVIER

D’ORMESSON, C. A. DAUBAN, A. DE BEAUCHAMP,

G. AND M. DU BELLAY, MAXIMILIAN DE

BÉTHUNE, DUC DE SULLY, ÉMILE DE

BONNECHOSE, MARQUIS DE CHAMBRAY, MARQUIS DE FERRIÈRES, PIERRE DE

L’ESTOILE, CHARLES MERCIER DE LACOMBE, BERNARD DE LACOMBE,

FRANÇOIS DE LANOUE, LA BARONNE DE STAËL, DU FRESNE

DE BEAUCOURT, H. FORNERON, C. A. FYFFE, BERNARD

GERMAIN, ABBÉ GIRARD, HENRI GIRARD, SAINT-MARC

GIRARDIN, HENRY HALLAM, HERMANN HETTNER,

VICTOR HUGO, W. H. JERVIS, J. B. F.

KOCH, H. LEBER, U. LEGEAY, G. H.

LEWES, L. DE LOMÉNIE,

O. DE LA MARCHE, SIR THOMAS ERSKINE MAY, MARQUIS OF NORMANBY, E. DE

MÉZERAY, COUNT VON MOLTKE, WILHELM MÜLLER, DAVID MÜLLER, W. F. B.

NAPIER, J. B. PAQUIER, JULIA PARDOE, A. RASTOUL, P. ROBIQUET,

C. ROUSSET, ROSSEEUW ST. HILAIRE, D. SAUVAGE, MAURICE DE

SAXE, EDMOND SCHÉRER, F. C. SCHLOSSER, SIR WALTER

SCOTT, A. SORBIN, J. L. SOULAVIE, SAINT

RENE-TAILLANDIER, EUGÈNE TÉNOT, J. E.

TYLER, MAURICE WAHL, JAMES WHITE,

E. F. WIMPFFEN, HENRY SMITH

WILLIAMS, R. T. WILSON

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

[1]

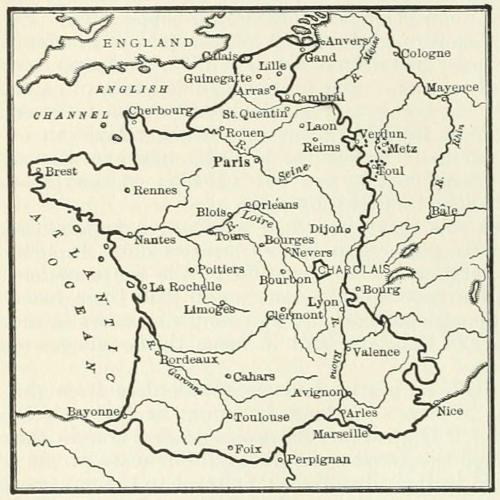

Up to the present we have told the history of the Gauls, the Gallo-Romans, and the Franks; with the Treaty of Verdun we begin the history of the French people. There now existed in France, except the Northmen, who already were beginning to appear on its coast and who established themselves there only in small numbers, all the races of which her people are formed, and all the elements, Celtic, Roman, Christian, and Germanic, whose combination goes to make up her civilisation. The medley is even already too sufficiently advanced for one to distinguish any longer the Gallo-Roman from the Frank, the civilised man from the barbarian. All have the same customs and almost all the same tongue. The French idiom showed itself officially in the Treaty of Verdun. Law ceases to be personal and becomes local; national custom replaces the Roman or barbaric codes; there are scarcely any slaves; there are but few free men—we shall soon see nothing but serfs and lords.

But this France has no longer the extent of Gaul; the Treaty of Verdun has confined it to the Schelde and the Maas, the Saône and the Rhone, and the population within these narrow limits finds them still too broad; they wish to live apart, for themselves alone, and not to sustain a vast dominion which is crushing them and which they do not understand.

The son of Judith and Louis le Débonnaire, Charles the Bald, king of France since 840, was nothing but an ambitious man of the people. Length of days was generously bestowed upon him, as it had been with Charlemagne, for he reigned thirty-seven years—but he knew how to do nothing with his life. Difficulties, it is true, were great. The same year when the destinies of the empire were moulded at Fontenailles, Asnar, count of Jaca, helped himself to the sovereignty of Navarre, and the Northmen burned Rouen—in 843 they pillaged Nantes, Saintes, and Bordeaux. At the same [2]time the Aquitanians rose up for a national king. The Bretons had found theirs in Noménoë, whom Charles had excommunicated by the bishops, but who defeated his lieutenants; and Septimania had its chief in Bernhard. The Saracens and the Greek pirates ravaged the south while the Northmen devastated the north and the west. And as if to fill the cup of misfortune of which this age was the bearer, the Hungarians, successors of the Huns and Avars, were putting in an appearance in the east.

These dreaded pirates, the Northmen, were the men whom hunger, thirst for pillage, and love of adventure drove each year from the sterile regions of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. In three days an east wind brought their two-masted ships to the mouth of the Seine. The fleet obeyed a kuning or king. “But,” says Augustin Thierry, “he was king only at sea and in battle; for when the banquet hour arrived the whole troop sat at the same table, and the beer-filled horns passed from hand to hand without there being a first or a last. The sea-king was followed everywhere with fidelity and obeyed with zeal, for always he was reputed the bravest of the brave, like him who had never drained a cup at a protected fireside.

“He knew how to handle ships as a good knight his horse, and to the ascendency of courage and skill there was added the power that superstition gave him. He was initiated in the sciences of the Runes. He knew the mysterious characters which, graven on swords, would procure victory, and those which inscribed on the stern or on the oars would prevent shipwreck. All equal under such a chief, supporting lightly their voluntary submission and the weight of mailed armour which they promised themselves to exchange for an equal weight of gold, the Danish pirates gaily travelled the ‘path of the swans,’ as their ancient national poetry called it. Now they hugged the shores and watched their enemy in the narrow straits, bays, and little anchorage grounds, from which they got their name of vikings,—children of the bays and creeks,—now they hurled themselves forth in pursuit of him across the ocean. The violent storms of the North Sea scattered and crushed their frail ships. There were always some missing when from the chief’s ship came the signal to gather together, but those who survived their shipwrecked companions had no less confidence and no more concern. They laughed at the winds and the waves which could not destroy them. ‘The might of the storm,’ they sang, ‘aids the arms of our oarsmen—the tempest is at our service; it throws us where we would go.’”

Some of them often, in the midst of the clash of arms and the sight of blood, became possessed with a sort of mad fury which redoubled their strength and made them insensible to wounds—as if they saw revealed to their eyes the palace of their god Odin and the shining hall of Valhalla. Others showed an irresistible courage under torture, and sang their death-song in the agonies of torment. Thus the famous Lodbrog, when thrown into a ditch filled with vipers, flung proudly back these words to his enemies:

“We have fought with the sword. I was still young when in the East, under the stars of Eirar, we dug a river of blood for the wolves and invited the yellow-legged bird to a great banquet of corpses: the sea was red like a fresh-opened wound and the ravens swam in blood.

“We have fought with the sword. I have seen near Aienlane (England) numberless bodies filling the decks of the ships; we continued the fight for [3]six whole days and the enemy did not give in; the seventh, at sunrise, we celebrated the mass of swords. Valthiof was forced to bend under our arms.

“We have fought with the sword. Torrents of blood rained from our swords at Partohyrth (Pesth). The vulture could find no more in the bodies; the bow thrummed and arrows buried themselves in coats of mail; sweat ran over the sword blades. They poured poison into the wounds and harvested the warriors like Odin’s hammer.

“We have fought with the sword. Death seizes me. The bite of the vipers has been deep. I feel their teeth at my heart. Soon, I hope the sword will avenge me in the blood of Ælla. My sons will rage at news of my death—anger will redden their visages; besides, brave warriors will take no rest until they have avenged me.

“I must cease—behold the Dysir whom Odin sends to lead me to his joyful palace. I go thither with the Ases, to quaff hydromel at the seat of honour. The hours of my life have run out and my smile braves death.”

Religious and warlike fanaticism are here joined together—these pirates loved to shed the blood of priests and stable their horses in the churches. When they had ravaged a Christian land: “We have sung them,” they said, “the mass of spears; it began at early morn and lasted till the night.” Charlemagne felt these terrible invaders from afar; under Louis le Débonnaire they grew bolder. Some of them set up abodes, in 837, on the island of Walcheren, and made tributary the river lands of the Maas and the Waal. After 843 they came every year. From the mouth of the Schelde, the Somme, the Seine, the Loire, and the Gironde, they ascended into the interior of the country. A number of towns, even the more important, as Orleans and Paris, were taken and pillaged by them without Charles being able to make any defence. From the Rhine to the Adour, from the ocean to the Cévennes and the Vosges, all was devastated. They even acquired the habit of not returning home during the winter and settled down on the island of Oissel—above Rouen, at Noirmoutiers at the mouth of the Loire and on the island of Bière, near St. Florent. It was thither they carried their booty and thence they set out on new expeditions.

Chroniclers not understanding that apathy of the Frankish nation once so brave, who now let themselves be pillaged by a handful of adventurers, could only explain these things on the supposition that there had been a tremendous massacre at Fontenailles (Fontenay).

There is some truth in these words. Charlemagne’s fifty-three expeditions had used up the Frankish race, and his conquests, where always some of his warriors were left behind to rule, had spread it over three kingdoms. The dissensions of Louis le Débonnaire’s sons completed this dissemination. Now there were no longer free men to be found, because of the terrible [4]results of so many wars, because in the midst of growing anarchy almost all the free men had renounced an independence which left them in isolation and consequently in danger, to become the vassals of men able to protect them. The Edict of Mersen (847) says, “Every freeman may choose a lord, either the king or one of his vassals, and no vassal of the king will be obliged to follow him in war unless against a foreign enemy.” With the subjects thus disposing of their obedience, the king in civil war remained unarmed and powerless, and as he was as incapable of making the great obey him as he was of protecting the small, the latter gathered around the former. The king’s vassals diminished; those of the great lords increased. On all sides national interest was forgotten in solicitude for that of the individual. Rouen troubled itself little about the misfortunes of Bordeaux, Saintes, and Paris, and that is why in this age, as in the last days of the Roman Empire, and for the same reason, namely the absence of that common and spirited sentiment known as patriotism, a few small bands could ravage a great country. Charles tried to send them back by giving them gold; but this was the surest means to attract them. The Roman Empire had done the same thing with the barbarians, and we know with what result.

The number of true Northmen must have been comparatively few, since they came from afar and over the sea. “But,” as a chronicler of the time remarks, “many inhabitants of the country, forgetting their regeneration in the holy waters of baptism, plunged into the dark errors of the pagans: they ate with these pagans the flesh of horses sacrificed to Thor and Odin, and took part in their atrocious crimes.” And these renegades were the most to be feared. They acted as guides to the invaders, they knew how to foil the ruses their countrymen adopted to cheat the greed of the barbarians, and showed even less respect and mercy than the latter for the religion and the people they had abandoned. Sometimes even some of the powerful nobles were paid by the Northmen, with money raised by the pillage of France, so as not to be disturbed in their expeditions.

The most dreadful of these pirates was Hastings, who ravaged the banks of the Loire from 843 to 850, sacked Bordeaux and Saintes, threatened Tours, which still celebrates to-day, on the 21st of May, a victory won from him, circumnavigated Spain and, robbing and burning the while, reached the shores of Italy. He had been drawn by the great name and wealth of the capital of Christendom; but he mistook Luna for Rome. Hastings sent word to the count and the bishop that his companions, conquerors of France, wished no harm to the people of Italy and only wished to repair his storm-battered ships, and that he himself, wearied of his roving life, wished to seek repose in the bosom of the church. The bishop and the count refused him nothing; Hastings even received baptism; but the gates of the town remained shut. Some time after the camp was filled with lamentations; Hastings was dangerously ill. Messengers came with the news and declared at the same time that the dying man intended to leave all his booty to the church provided his body might be interred in consecrated ground. The Northmen’s cries of grief soon announced the death of their chief. They were permitted to bring his body into the town, and the funeral ceremony was prepared in the cathedral itself. But when they had set down the corpse in the middle of the choir, Hastings suddenly rose up and struck the bishop down, while his companions, drawing their concealed arms, [5]massacred both priests and soldiers. Master of Luna, Hastings perceived his mistake. He was made to understand that Rome was a long way off, and could not be so easily captured, so he set sail with his booty and at the end of several months reappeared at the mouth of the Loire.

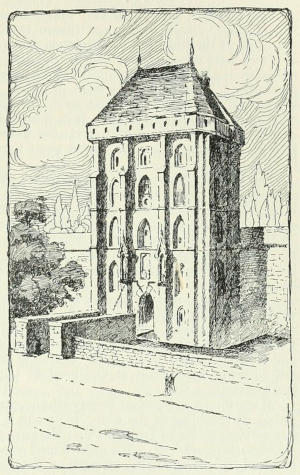

Ancient French Doorway

Charles the Bald had reunited one part of the country, between the Seine and the Loire, under command of Robert the Strong, ancestor of the Capetians, in order to oppose a more efficacious resistance to the Northmen and the Bretons, a great number of whom had joined the pirates. Robert gained two victories over the Bretons and defeated a body of Northmen loaded with the booty of Brie and of the town of Meaux. This was the valiant leader whom Hastings encountered on his return from Italy. He had just sacked Le Mans when Robert and the duke of Aquitaine caught up with him at Brissarthe (Pont-sur-Sarthe) near Angers. The barbarians numbered but four hundred, half Northmen, half Bretons; and at Robert’s approach they betook themselves to a church and barricaded it. It was evening, and the French put off the attack until the next day. Robert had already taken off his helmet and coat of mail, when the Northmen, suddenly opening the doors, threw themselves upon the dispersed troops. Robert rallied his men, drove the enemy back to the church, and tried to follow them in. But he fought with bared head and breast and on the threshold was mortally wounded. Duke Rainulf of Aquitaine fell by his side (866). Hastings, delivered of his dread adversary, ascended the Loire and made his way as far as Clermont-Ferrand. No other means could be found of ridding France than by giving him, in 882, the county of Chartres. But he even abandoned this at the age of nearly seventy, to resume his life of adventure.

The Northmen were the greatest but not the only one of Charles’ troubles; the Breton Noménoë repelled all his attacks, crowned himself king, and left the title to his son Hérispoë. The Aquitanians elected as leader the son of their late king, Pepin II, whom Charles the Bald had deposed. Driven out on account of his vices, Pepin allied himself with the Northmen and Saracens to pillage his former subjects, but he was captured and shut up in a cloister. Charles recovered, for the time, Aquitaine, lost it, recovered it again and gave it to one of his sons. But the true masters of the country [6]were Raymond, count of Toulouse, who also ruled over Rouergue and Quercy; Walgrin, count of Angoulême; Sancho Mitara, duke of Gascony, whose capital was Bordeaux; Bernhard, marquis of Septimania; Rainulf, duke of Aquitaine and count of Poitiers; Bernard Plantevelue, count of Auvergne; all of whom founded hereditary houses. To the north of the Loire, Charles had been constrained in the same way to constitute, for Robert the Strong, the grand duchy of France, from which sprang the third line of kings. North of the Somme it had been the same thing with the county of Flanders, given to the king’s son-in-law, Baldwin Bras de Fer (Iron Arm), and between the Loire and Saône, the powerful duchy of Burgundy for Richard the Judge. Thus under Charlemagne’s grandson not only was the empire divided into kingdoms, but the kingdoms themselves were dismembered into fiefs.[1]

Charles made, however, more and more the effort to retain in his service and that of the state the class of freedmen. In 863, the Edict of Pistes ordered a census of the men bound to military duty. The most severe penalties were pronounced against those who deprived these men of their horses and their arms, and also against the artful ones who sought to avoid military duty by giving themselves to the church.

This prince, so weak at home, wished nevertheless to aggrandise himself abroad. The king who could not wear his own crown undertook to acquire others. At the death of the emperor Lothair, in 855, the inheritance was shared between his three sons. The eldest took Italy, the second Lorraine, and the third Provence. The last only lived until 863, and the king of Lorraine until 869, and neither had any children. Charles the Bald tried, on their death, to lay hands on their dominions. His plans miscarried in 863, but succeeded in 870, when he shared Lorraine with his brother, Louis the German. In spite of the weakness and dishonour of his reign, Charles the Bald brought together again, at least on one side, the France which the Treaty of Verdun had broken up.

Instead of continuing this policy Charles sought for the imperial crown, left once more without a wearer in 875. He sought it in Rome from the hands of the pope, took on his return to Milan that of the Lombard kingdom, and as his brother, Louis the German, had died, he attempted to annex the latter’s dominions to his own—that is, Germany to France. At this moment the Northmen took Rouen from him. He was beaten on the Rhine; Italy likewise escaped him.b

Unity existed only in the ambitious fancy of the feeble Charles. In spite of his titles and his crowns, his power in Italy, Lorraine, and Provence was as much a cipher as it was in Gaul; the dismemberment of the kingdoms into duchies and counties, and of the latter into viscounties, sireries, and seigneuries, still continued; and, at the very moment when he was dreaming of his grandfather’s empire, he was finally completing his own destruction by changing the feudal system from a custom into a law.

Before going to Italy in 877, he assembled a diet at Quierzy to formulate rules for the government of Gaul by his son, and there was delivered that famous capitulary from which we may date the feudal revolution: “If one of [7]our trusty subjects,” runs this capitulary, “inspired by the love of God, desire to renounce the world, and if he have a son or some other relative capable of serving the state, he is free to transmit to him his privileges and honours at pleasure. If a count of this kingdom dies, we desire that the nearest relatives of the deceased, the other officers of the county, and the bishops of the diocese provide for its administration until such time as we shall be able to intrust his son with the honours with which he was invested.”

This capitulary effected no change in the existing state of things, it only confirmed accomplished facts and legalised a revolution which had its origin in the customs of the Germans even before their entry into Gaul, that is to say the transformation of fiefs into freeholds and the acquisition of hereditary rights in duchies and counties. From this time the distinction between allods and feods had no longer either reality or importance; as the son of the count inherited not only the domains but also the offices of his father, the distinction between the magistrate sent from the king and the lord of the manor was done away; and the titles of duke and count no longer expressed merely an office, an honour, or a dignity, but sovereign rights. The feudal system was thus inscribed in the law.c

Such was the condition in which Charles the Bald left France when, in 877, he went to Italy, to fulfil the obligations he had contracted on receiving the imperial crown. Pope John VIII had begged him to drive the Saracens from the peninsula, and repress the aggressions of his nephew Carloman, king of Bavaria, a pretender to the empire. It is astonishing, the persistence with which Charlemagne’s descendants, in taking arms against each other, not only hastened the disorganisation of their own states, but accomplished the rapid ruin of their house in Italy, Germany, and even France, where it lasted three or four generations longer than anywhere else. The campaign of 877 bore no result. Charles’ only idea after he got to Italy seems to have been to pillage the imperial domains. Abandoned for the most part by his vassals, he was obliged to return to France, fell ill during the return, and died the 6th of October, a few days after he had crossed the Mont Cenis.

Louis the Stammerer, given a share in the throne during his father’s lifetime, was crowned by Hincmar at Compiègne in presence of most of the great vassals. By the advice of Hincmar the new king pledged himself to disturb no man in the possession of his benefices or offices and to respect the liberty of the churches. He was also obliged to make a distribution of lands, abbeys, and counties “to whoever,” says one chronicle, “demanded them first.”

Charles the Bald had worn four crowns, those of France, the empire, Italy, and Lorraine. His son inherited the first only. The imperial crown and the crown of Italy passed to the head of a Carlovingian prince of the Germanic branch. Ludwig of Saxony contended with Louis the Stammerer for that of Lorraine and the two claimants came to terms by dividing the kingdom on the bases of the treaty of 870. This treaty was renewed in 878 at Fouron on the Maas. The south was troubled by the revolt of Bernhard, marquis of Gothia, who took arms and formed a league of malcontents. But Bernhard, count of Auvergne, and Boson, duke of Provence, took from him successively Gothia and several counties which he possessed in Burgundy.

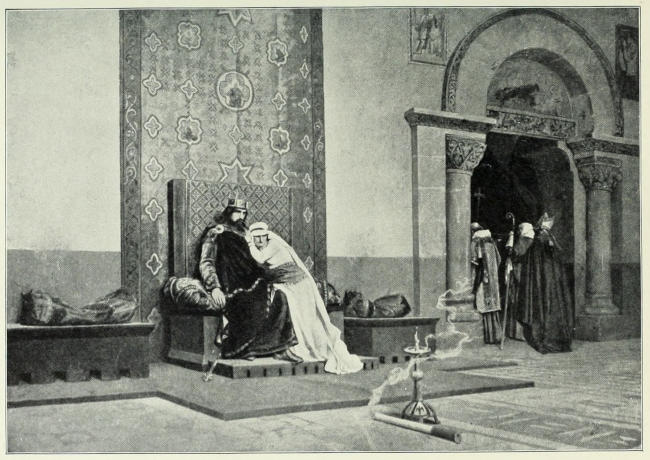

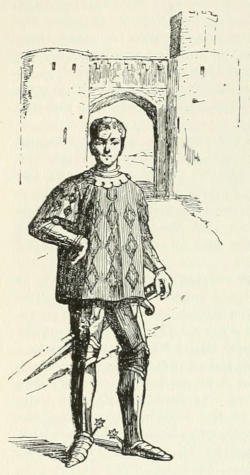

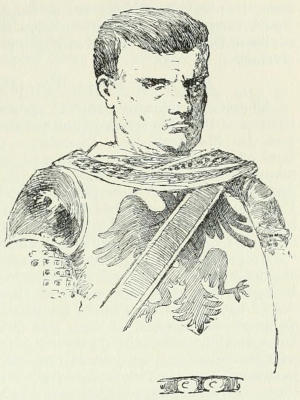

Louis III and Carloman

(From an old print)

Louis the Stammerer, having fallen into a decline, died in 879 at Compiègne leaving two sons, Louis and Carloman, of whom the eldest was sixteen years old. The seigneurs were divided; some wished to proclaim the young [8]French princes, others to give the crown to the German prince, Ludwig of Saxony. But the party of French princes was the most numerous and the abbot Hugo, who was its leader, hastened to crown the two brothers.d Two victories over the Northmen, notably that of Saucourt in Vimeu, gave a little glory to these princes. But these advantages did not prevent the recommencement of brigandage. In 885 the famous Hastings gave up the county of Chartres, and Carloman paid the others of his race to take themselves off. “They promised peace,” says the chronicler sadly, “for as many years as we could count them one thousand pounds’ weight of silver.” The two kings died by accident, Louis in 882, Carloman in 884. One had governed the north of France, the other Burgundy and Aquitaine.

These two had a brother, Charles the Simple, but the nobles preferred a grandson of Louis le Débonnaire, Charles the Fat, then emperor and king of Germany. The whole heritage of Charlemagne was now reunited in Charles the Fat’s hands. But times had changed. This man weighted down with so many crowns could not even inspire terror in the Northmen.

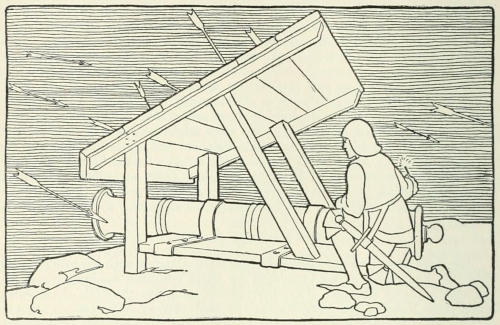

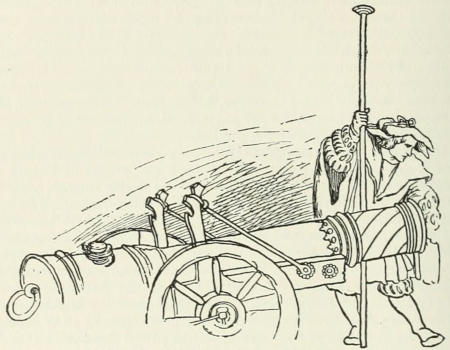

Charles had already ceded Friesland to one of their chiefs. Another, the famous Rollo, a kind of giant who, as legend tells us, always went about on foot because no horse could be found for his mount, had recently taken Rouen and Pontoise and killed the duke of Le Mans. At the approach of his countrymen, the new count of Chartres, the former pirate Hastings, hastened to meet them and all marched upon Paris, which had already three times submitted to the sack. But Paris had recently been fortified. Great towers covered the bridges (Petit-Pont and Pont-au-Change) which connected the island of the city of Paris with the two shores. The Seine was then barricaded with seven hundred huge barges in which the Northmen intended to voyage into Burgundy, a region they had not yet visited. The inhabitants, encouraged by their bishop Gozlin and by Count Eudes, son of Robert the Strong, held out for one year. The attack began November 26th, 885. The tower of the Grand-Pont, on the right bank, not being finished, the Northmen assailed it. For two days they fought there with great fury and Bishop Gozlin was wounded by a javelin. The Northmen were driven back and intrenched themselves in a camp around the church of St. Germain l’Auxerrois, where deserters soon taught them all the knowledge of Roman military science that had survived the ages. The invaders first built a three-storied rolling tower, but when they tried to bring it up to the walls, the Parisians killed with arrows those who were moving it. Then they advanced with battering-rams, some under portable screens covered with raw leather for protection from fire, and some [9]under shields in the form of the Roman testudo. When they came to the edge of the moat they began to fill it up with earth, fascines, whole trees, and even the bodies of captives whom they put to death before the very eyes of the besieged. While those farthest away drove off the defenders of the battlements with a hail-storm of arrows and leaden ball, those close to the tower hammered it with the rams; but all in vain. The Parisians poured streams of boiling oil, wax, and molten pitch upon the enemy; their catapults hurled huge rocks which crushed the assailants’ screens and shields, and let down iron hooks which tore away the coverings and made the enemy a target for their arrows. Three blazing ships floated down to the bridge, were stopped by the abutting stone piles, and could not set it on fire.

This hopeless resistance had lasted for more than two months when a sudden rise of the river carried away, on the night of February 6th, 886, a portion of the “Petit-Pont.” The Northmen immediately rushed upon the tower on the left bank, now cut off from the city. Only twelve men were stationed there, but they held out for a whole day and then retired, still fighting, to the wreckage of the bridge. Finally they surrendered on the promise that their lives would be saved, but as soon as the barbarians got hold of these brave men they put them to death. One of them, of gigantic frame, appeared to be a chief, and the Northmen decided to spare him; but he begged to share the fate of his companions. “You will never get ransom for my head,” he told them, and so forced them to kill him.

Meanwhile reports of the Parisians’ courage had spread over the land and others were emboldened to emulate their example. Several pirate bands which had left the siege were beaten; the counsellor of the emperor Charles, Duke Henry, succeeded even in getting relief into the besieged town, but the pagans still maintained the blockade. Misery became extreme in the city and many people died. Bishop Gozlin and the count of Anjou “passed to the Lord.” The brave count Eudes managed to make his way out and went to hasten the emperor’s arrival, and when he saw the latter started, went back to his besieged people. The promised relief finally appeared, Duke Henry at its head. Wishing to reconnoitre the situation himself the duke advanced too near, and his horse fell into one of the Northmen’s pits. Here he was killed and those who had come with him were disbanded. Paris was once more left to its fate. The Northmen now believed that despair reigned there, and that they could have the people at little cost. They began a general attack, but the walls covered with valiant defenders proved insurmountable. They then tried to fire the door of the great tower, by heaping up against it a great wooden pile, but the Parisians made a sudden sortie and drove back the assailants and the fire at the same time.

At the end of long months, Charles finally arrived with his army on the heights of Montmartre. The Parisians, filled with ardour, awaited the signal of combat, when the news came to them that the emperor had bought with money the withdrawal of their half vanquished enemy and given the barbarians permission to “winter” in Burgundy, that is to say, to ravage that province. They at least refused to be a party to this shameful agreement, and when the Northmen’s ships presented themselves at the bridges they refused to let them pass. The pirates had to drag their boats upon the shore and made a wide detour in order to avoid the heroic city (November, 886). The brave people of Sens imitated the courage of the Parisians and resisted the Northmen for six months.

In that year Paris gloriously won its title of capital of France; and its chief, the brave count Eudes, laid the foundation of the first national [10]dynasty. The contrast between the courage of the little city and the cowardice of the emperor turned everyone against the unworthy prince.b On all sides he was accused of indolence and incapacity. A great weakness of body and spirit had come over him. The vassals wanted an able and active king.

Those of Germany and Lorraine, assembled at Tribur, near Mainz, in 887, pronounced Charles’ deposition “because he was lacking,” says the Annals of St. Waast, “in the necessary strength to govern the empire.” The feeble and unfortunate emperor suffered the fate of the “do-nothing” Merovingian kings. He was shut up in the monastery of Reichenau, on Lake Constance, and died in about two months.d The empire of Charlemagne was irrevocably dismembered; its pieces served to form seven kingdoms—France, Navarre, Cisjurane Burgundy, Transjurane Burgundy, Lorraine, Italy, and Germany.

But it was not only the empire that was dismembered; it was also the realm and royalty itself. At the close of Charlemagne’s reign, feudalism was not yet founded, but it was almost completely established at the death of Charles the Bald a half century afterwards. And this was because the progress of feudal institutions was singularly hastened by the historical events we have just been studying.

Royal authority at the end of Charles the Bald’s reign was ruined, as it had been under the later Merovingians, for the same reasons and in the same fashion. The king had no more money and he had no more land to give away. He tried to take from the church, but the church resisted. The bishops assembled in council at Meaux and at Paris in 846, in the early years of the reign, advised Charles the Bald to send missi dominici to make a thorough investigation of the lands of the royal fisc, which had been usurped. “You must not,” they told him, “let a state of poverty, which does not accord with your dignity, push your magnificence to do things you would not wish to do. You cannot have attendants to serve you in your house, unless you have the means to pay them.” Here we see royalty reduced to indigence. The king himself recognised it. “We wish,” he said, one day, “to determine, with the advice of our faithful, how we may live in our court honourably and without poverty, as our predecessor did.”

Since the reign of Charles the Bald, public authority had disappeared. The kingdom, ravaged by the Northmen, the Bretons, and the Aquitanians, was in the throes of brigandage. Brigandage had sunk so deeply into the customs of the country that oaths were exacted from freemen not to attack houses or to conceal robbers. In his twenty-third capitulary (857) the king, after speaking of the infinite evils caused not only by the incursions of the pagans, but also by the vagabondage of some of his own royal subjects, orders the bishops, counts, and missi to call together general meetings which everyone without exception must attend. The bishop was to read to the gathering the precepts of the Gospels, the fathers, and the prophets against brigandage. The capitulary itself furnished quotations from Christ, the prophet Isaiah, St. Augustine and St. Gregory. If these were not sufficient the bishop was to add all those he might find himself. He was also to threaten all hardened sinners with anathema, and to explain to them what a terrible punishment it was. On their own side the counts and missi were to read the laws of Charles and of Louis against brigandage.

[11]

If these readings had no effect the guilty man was threatened with the sentence of the bishops and the prosecution of the judges. If he showed contempt for the one or the other he could be summoned to the king’s presence. If he refused to come he would be excluded from the holy church, on earth as well as in heaven. He would be pursued until driven from the realm. But to this there must be a public force, and such existed no longer; and this is why the king was compelled to replace it with sermons and threats of hell.

Ruins of a Norman Church, France

In no age of history did the weak have more need of protection than in the tenth and eleventh centuries, and this is why the last freemen disappeared throughout a large portion of Gaul, especially north of the Loire.

[12]

After having fled for a long time at the approach of the pagans to the forest, among the wild beasts, some stout-hearted had turned their heads and refused to abandon all they had without some attempt at defence. Here and there in mountain gorges, at river fords, or on the hill overlooking the plain, walled strongholds were raised up where the brave and the strong held their own. An edict of 862 directed the counts and the king’s vassals to repair their old castles and to build new ones. The country was soon covered with these strongholds against which invaders often flung themselves in vain. A few defeats taught these bold people prudence, and they dared not venture so far amid these fortresses which had sprung out of the ground on all sides, and the new invasion, now made hazardous and difficult, came to an end in the following century. The masters of these castles became later the terror of the country side they had helped to save. Feudalism so oppressive in its age of decadence had its legitimate term. All power is raised up by its good services and falls by its abuses. These hedged and walled-in castles were places of refuge from the Northmen, but often also they became nests of brigands. However, little by little, out of the chaos came a new order of things.

We have seen how the king and his nobles assured themselves of the services of a greater or less number of men by giving them benefices or rather taking these men under their protection by making them their vassals. One might be a beneficiary without being a vassal or a vassal without being a beneficiary; in the days of Charles the Bald there were vassals who held no land. These were the vagi homines, so often mentioned in the prince’s edicts—brigands in search of fortune and who transferred their loyalty from one noble to another at their pleasure. It was to remedy these disorders and to organise these unruly members of society that Charles the Bald ordered every freeman to choose a lord and remain faithful to him.

Doubtless it happened more often than otherwise that the man who received a piece of land made himself a vassal of the man who gave it to him, but the two states finally became much confused. One might be at the same time both beneficiary and vassal, and take upon himself the very narrow obligations of one and the other condition. Indeed after a property had been held for several generations by men who inherited their obligations together with the land, it seemed as if the fief carried its rights and duties with it and communicated them to those that held it. In the end the property, which always remained, was considered rather than the men, who came and went. It was no longer the weak man who bound himself to the strong one but the little acreage to the great domain, and certain formalities symbolised this new relation. The land became his in a manner to replace itself in the hands of the great landlord, in the shape of a clod of sod or the branch of a tree, which the petty proprietor brought himself. This land, so burdened with obligations, was the fief.

When France became covered with fiefs each property had its own organisation; it had its lord, great or small, and there was no land without its lord. Whoever had no land had no condition, for there was no lord without his land. Certain relations were established between the different fiefs—there were some which were dominant and others which were dominated. The dominant fiefs were those of the dukes and the counts, who assumed all the power which royalty had delegated them and who ruled as petty kings over their duchies and counties. Their vassals and the latters’ sub-vassals depended upon them before depending upon the king. As for the dukes and counts, they were the vassals of the king, but as the feudal [13]hierarchy developed, the obligation of the vassal became, as a matter of fact, less strict. The duke of Burgundy’s vassals obeyed him; of course the duke of Burgundy would not make the mistake of disobeying the king.

Such was the great revolution accomplished at the end of the ninth and in the tenth century. After the deposition of Charles the Fat appeared the great fiefs whose names we find over and over again throughout the whole of French history. The duke of Gascony owned all the country south of the Garonne, and the counts of Toulouse, Auvergne, Périgord, Poitou, and Berri, the district between the Garonne and the Loire. To the east and north of the latter river everything belonged to the count of Forez, the duke of Burgundy, the duke of France, and to the counts of Flanders and Brittany who exercised their royal rights over the land. To the kings remained only a few towns which he had not yet been constrained to give away in fiefs.

In the ninth century royalty fell and feudalism arose; the former had lost its strength, the latter had not yet acquired that which it was soon to have. The church alone had all the power. She wanted nothing—the authority in knowledge and morality, the ardent faith of the people, rich domains—in fact, while everything was breaking up and civil and political society going to pieces, the ecclesiastical body showed its unity and its healthy condition in the fifty-six councils which were held in the reign of Charles the Bald alone. The bishops, reasoning on the right of the church to interfere in the conduct of every man guilty of sin in order to correct and punish him, arrived logically at the pretension that they could depose kings and dispose of their crowns. They were not only the ministers of religion, but participated at the time in the administration of public affairs. Since Charlemagne, who brought them into the government of his empire, they may be found taking part in all affairs and speaking everywhere with authority. These were they who degraded and re-established Louis le Débonnaire, who told at Fontenailles on which side justice lay. In 859 Charles the Bald, threatened with deposition by some of the bishops because he violated his own laws, could find nothing further to reply to this assumption of authority than that “having been consecrated and anointed with the holy chrism, he could not be overthrown on his throne, nor supplanted by anyone without being heard and judged by the bishops who had crowned him king.” This right Archbishop Hincmar, of Rheims, the most illustrious personage of his day, had haughtily claimed.

This power of the church was a fortunate thing in these days, when might made right, for she alone found herself in a position to keep alive the idea that justice was above strength; and to oppose the aristocratic principle of the feudal organisation, she put forward that of the brotherhood of man. In place of hereditary primogeniture which prevailed in civil society, she practised election for herself and proclaimed the rights of the intellect. If the prerogative of deposing kings which she claimed was a usurpation of temporal authority it must be recognised that the latter had no antidote but the sacerdotal power, and the weak and oppressed no other security than the protection of the churches. When Lothair II, king of Lorraine, put away without reason Queen Thietberga in order to marry Waldrada, Pope Nicholas I took up the poor, betrayed, outraged woman’s cause, and at the risk of persecution established her rights. While law was impotent and opinion without strength, it is well that somewhere there existed an avenger of outraged morality.b

[14]

Eight kings shared in the division of the empire through the deposition of Charles the Fat. In France it was Eudes, count of Paris, who had just defended that town against the Normans and whose glory was heightened by contrast with the ignominious conduct of Charles the Fat.

The accession of Count Eudes was an important fact, although overestimated perhaps, if one wishes to regard it as a bridge between Gaul and France and between the Franks and the French. It was not the beginning of a revolution of which he was the consummation; nor yet a point of departure, for it was Frenchmen rather than Angevins who fought with Robert the Strong at Brissarthe. However, apart from the fact itself, the reign of the first French king was certainly important. The Normans, turned loose upon Burgundy by Charles the Fat, had gone still further; they threw themselves upon Champagne which they were proceeding to ruin with fire and sword when the new king attacked them in the defiles of the Argonne, near Montfaucon. A brilliant victory made a worthy beginning to his reign, but that was all. Wearied by the fruitless struggle, occupied elsewhere by the anxieties which Aquitaine gave him where through race jealousy his “usurpation,” as the monks of that time and the seventeenth century historians called it, had not been recognised, and at a time when they placed at the head of acts, Christi regante: rege nullo (“in the reign of Christ and absence of the king”). Eudes finally adopted the Carlovingian policy and drove the Normans back with his purse. What brought about his ruin was that he broke too abruptly with the feudalism that made him king. His cousin Vaucher rebelled against royal authority. Eudes could not understand that this authority was no longer anything but a phantom, even in his hands, and he had his cousin’s head cut off after obtaining his submission. The people deplored the light-hearted nonentity of a Carlovingian king, but a faction which formed in favour of young Charles the Simple, youngest son of Louis the Stammerer, waxed in strength until the former count of Paris was obliged to capitulate. He admitted his rival to a sort of partnership and at his death the kingdom of France returned to Germanic dominion, if we can admit, that it is still possible to recall the Austrasian origin of Charles the Simple (898).

Under this reign the people were finally delivered from the long Norman invasion, which stopped of its own accord, and by act of the invaders rather than resistance of the invaded. Since the time the Norman vassals collected at the mouth of the Seine, the country round about had been nothing but a desert, towns abandoned, villages in ashes; one could travel whole leagues without even hearing a dog bark. Since there was nothing more to be got they ran the risk of dying by hunger. The Normans finally perceived with their positive spirit that it was better to take possession of the land than to pillage its ruined inhabitants, and that it was worth more to make these rich territories valuable than to get sustenance from their ruins. Thenceforth everything was changed. The fleets from the north brought colonists instead of pirates, and the peasants found in their midst a protection which they could not have gotten anywhere else.

The new plan had been in operation for some time when a great emigration was determined upon in the north, owing to the subjection of all the chiefs under one head. The movement set out in the direction of Neustria under the leadership of Rollo, the famous sea-king—one of those who had assisted at the siege of Paris in the days of Charles the Fat, and had established a fixed home in that country. For some years the new-comers kept [15]up their old practises. They burned St. Martin of Tours, and went to Bourges and killed the bishop. Rollo reappeared before the towers of the châtelet. Finally he came to an understanding with Charles the Simple, who gave him his daughter Gisela in marriage and raised him to the rank of the feudal barons, by legalising his seizure of Neustria. Rollo became duke of Normandy, and the king of France’s vassal, not without making the latter often feel that he troubled himself little about the nominal suzerainty. When the time for doing homage came and they wished him to do it in the Carlovingian manner, by kissing the sovereign’s foot, “No, by God,” exclaimed the proud sea-king, and he signed to one of his soldiers to kiss the royal foot for him. But the soldier, not less proud, seized Charles’ foot and put it to his lips without kissing it. The king fell back and his people remained dumb and motionless amid the laughter of Rollo and his companions[2] (912). The barbaric traits of the Normans did not prevent their quickly assimilating the semi-civilisation they found in their new country. Normandy was soon the most prosperous and best policed province in the kingdom. As Ordericus Vitalisi says, a child could have crossed it in safety, a purse full of gold in his hand. There runs a tale that one day while hunting Rollo hung his gold bracelets on a tree and they remained there two years without anyone’s daring to touch them.

Charles the Simple lost no time in indemnifying himself for the cession of Neustria by the acquisition of Lorraine which became his on the death of Louis the Child, son of the emperor Arnulf; but he did not profit long by this addition to his realm. He had made a favourite of a person of low degree, a man named Haganon. Haganon, more solicitous than his master to uphold the royal dignity, soon displayed the desire of raising it, to his own profit, from the state of subjection in which it was kept by the powerful nobles. Two of the latter presented themselves four days in succession to speak with the king and waited in vain at the door of his bed-chamber. They finally went away thoroughly angry, saying that Haganon would soon be king with Charles, or Charles a man of low condition with Haganon. Of these two noblemen, one was Henry the Fowler, or the Saxon, king of Germany, and the other Robert, duke of France, brother of the late king Eudes.

In 920, at a court held at Soissons, the nobles assembled together, all broke the blades of straw and threw them on the ground at the feet of Charles the Simple, declaring that they disowned him as their king. Each took his departure at once, and Charles remained alone on the spot where the assemblage had met. There followed two years of hesitation, at the end of which Robert, duke of France, caused himself to be proclaimed king in the cathedral of Rheims by his vassals and those of his son-in-law, Rudolf of Burgundy. Charles having retired to Lorraine, the new king prepared to seek him as far as the foot of the Ardennes. He did not anticipate any resistance, but Haganon purchased the services of a band of Normans, living along the Maas, which Charles led in person into Robert’s domains. A battle took place on the plain of St. Médard (Soissons) near the Aisne (923). Robert, throwing his long white beard over his coat of arms, seized his banner and flung himself into the mêlée. He fell upon Fulbert, his rival’s standard-bearer, when Charles cried out, “Take care, Fulbert.” The [16]standard-bearer, turning, dodged the blow which Robert was aiming, and cleft the duke’s head with his sword. Charles the Simple gained nothing by this. Robert’s son, Hugh, hastened up with his brother-in-law, Héribert de Vermandois, and remained to the end master of the battle-field, strewn with eighteen thousand dead.

Of the two men who had claimed the title of king that morning, one lay cold in death, the other was dethroned by defeat. Robert’s son sent to consult his sister Emma, wife of Rudolf of Burgundy, to know what he should do with the crown on his hands. Emma replied that she would prefer to kiss the knees of her husband rather than those of her brother, and Rudolf was made king (July 13th, 923).

The aged Rollo was now minded of the homage which he had formerly held so cheaply, and as faithful vassal loudly declared himself the protector of the vanquished king. Doubtless he preferred such a sovereign as Charles the Simple to a connection with that powerful house of the dukes of France, who moved everything at their pleasure. Unfortunately he did not have the king in his hands. Charles had taken refuge at Bonn with the king of Germany, the same Henry the Fowler whom he had once kept waiting at his own door. He wished now to make use of the services of Héribert of Vermandois, who swore to replace him on the throne. The king sought Count Héribert at the gates of St. Quentin, where the latter knelt and kissed the king’s knee. The count’s son refused to do the same and Héribert took him by the neck and forced him to kneel. Then he conducted the king into St. Quentin and entertained him with great magnificence. But the next day he had him seized in the night and conducted to Château Thierry, whence they carried him to the tower of Péronne. Héribert then marched with Rudolf against the Normans, who were with great difficulty driven back from the Île-de-France and Beauvoisis. Rudolf believed himself mortally wounded during an encounter in Artois and the inhabitants of Laon saw him carried into their city on a barrow. Rollo died a short time afterwards, leaving as successor his son, William Longsword.

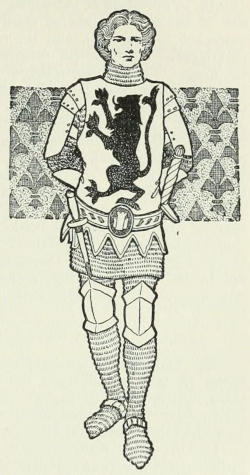

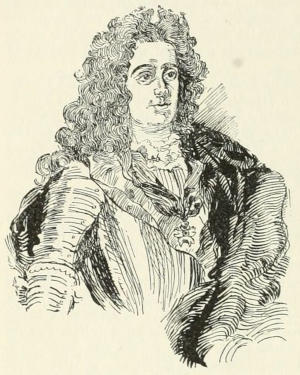

Rudolf, King of France

The count of Vermandois had not undertaken this piece of treachery for nothing, and had already obtained the archbishopric of Rheims for his son, a child of five years. They placed the boy on a table in the presence of the bishops, and after stammering a few words of catechism, he was consecrated with the approbation of the onlookers. But even this did not satisfy the father’s ambition, who demanded the county of Laon for himself. Rudolf, [17]who was finding his restless and dangerous auxiliary too powerful, feared perhaps the fate of Charles the Simple, and met the demand with a refusal. Thereupon Héribert dragged Charles from prison, clothed him in rich raiment, and took him to the court of William Longsword, who saluted him as king. This was all that was needed to decide Rudolf, who ceded the county of Laon, and Charles was put back in Péronne. But when Héribert tried to commence the same game again, Rudolf this time took up arms and pressed him so hotly that he was obliged to flee to Germany. There now remained to him nothing but Péronne, but Henry the Fowler, the count of Flanders, and the duke of Lorraine interfered; Rudolf gave him back his possessions and died soon after without a male heir (936). Charles the Simple had preceded him by a few years to the tomb (929). The vacant throne was for a second time at the disposition of the duke of France, who did not want it, since he found it much pleasanter to remain peacefully in real possession, pre-eminent as he was among the feudal lords, than to plunge himself into interminable controversies by placing on his head a crown which had become the target for so much contention. Rudolf’s enemies, of whom we have mentioned but a small part, had much reason to support the duke in this resolution. Hugh now remembered that at the time of the fall of Charles the Simple the latter’s wife Odgiwe had taken to England their son Louis, then a child, but now, after thirteen years of exile, entering upon his sixteenth year. Hugh congratulated himself on his great mind and went after him.

Louis IV, surnamed Louis d’Outre-Mer on account of his long sojourn on the other side of the Channel, occupied the throne eighteen years, but his reign was one long humiliation. Hugh exploited his generosity to the king, as Héribert had done about his treachery, and scarcely got him to the shores of France than he dragged him to the duchy of Burgundy and made Louis invest him with it; and moreover Louis had the chagrin of seeing that his act was useless. Hugh the Black, Rudolf’s brother, bravely defended his heritage. The royal signature served nothing to the duke of France who, armed as he was, could only snatch a few shreds from the duchy of Burgundy. Thwarted in his ambition he turned to other things and demanded the county of Laon. Following Rudolf’s example, Louis refused this demand, but for a still more powerful reason. The county of Laon was the sole domain left the crown through the usurpations of feudalism. Louis, who would have been nothing more than a stranger in his kingdom if this were taken from him, preferred a one-sided struggle. Fortunately for him, the emperor Otto came to his rescue, but not before he was besieged in his own city, and deserted by his most faithful partisans. The presence of the imperial army saved him from disaster, but Otto when he went home did not leave him any the stronger. Incapable of holding his own so close to the duke of France, Louis appeared before the people of Aquitaine, always favourably disposed towards the Carlovingian kings, since they had nothing to fear from them and had shown no more preference for the kingship of Duke Rudolf than they had for that of Count Eudes. Well received everywhere, Louis nevertheless encountered but a sterile compassion, and must have thought himself fortunate in that the duke of France, become more formidable than ever since the death of Héribert de Vermandois, was willing to await an occasion of revolt or rather of war.

[18]

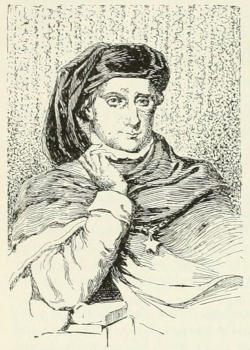

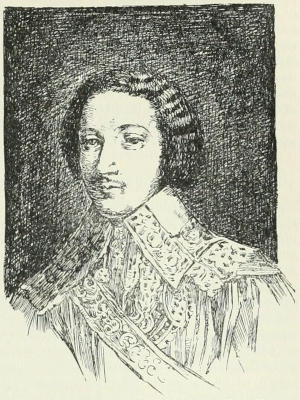

Louis IV

(From an old print)

Meanwhile William Longsword had met a tragic end, assassinated by Arnulf, count of Flanders, after an interview on one of the islands of the Somme, in December, 942. He left one son named Richard, only ten years old. The moment was now favourable for Louis to assert the royal authority, inactive in his hands. He appeared at once in Rouen, received the homage of the young Richard, and made himself the child’s guardian. The people nearly besieged the house in which he lodged when they learned that he intended to take the boy back to Laon, but a few tactful words calmed everything. But once he had the young duke in his palace he used no more caution. The child, separated from all his Norman attendants, even from his tutor, found himself in truth a captive. The people who looked after him were severely reprimanded on one occasion for having taken him outside the city on a hunt for birds. Evidently the king’s intention was to strengthen the royal crown by putting it under the protection of the ducal crown of Normandy. Osmond, Richard’s tutor, cut this dream short by a bold stratagem. Disguised as a groom he managed to get near his pupil, enveloped him in a bale of hay, and carried him thus on his shoulders to the outskirts of Laon, where horses were waiting. Touched to the quick Louis d’Outre-Mer appealed to the ambition of Hugh of France and proposed to share Normandy with him if he would help get it back. Hugh agreed, but scarcely was Louis established in Normandy than he forgot his promises and sent the duke back to Paris. But the king paid dearly for this breach of faith. At news of the subjection with which their Neustrian brothers were threatened, the Northmen sent a large fleet under the command of Harold, the Dane. A battle took place on the banks of the Dive, not far from Rouen, in which the French were completely routed (945). Louis, wandering swordless through the country at the will of his horse, whose bridle had been cut by sword-blows, met a soldier from Rouen who, anxious for the king’s safety, concealed him on an island in the Seine, where however he was discovered. The king’s liberty was negotiated with great show by Hugh of France, who finally got him out of the Normans’ hands. Great was the surprise when the end of this fine devotion became known. From his Norman prison Louis entered another which Hugh was determined he should not leave until he gave up the city and county of Laon. After this last misfortune Louis seemed less a king than a ruined lord. He filled the German court with his plaints, wrote to the pope, and summoned councils. Councils, pope, and emperor all failed before Hugh’s will. Finally tired of the fight, and knowing well that Louis would be none the more formidable with it, Hugh gave the county back to the king, who did not enjoy it for long. Four years later, while pursuing a wolf on the road from Rheims to Laon, Louis’ horse threw him and he died from the fall (954).

[19]

Hugh had obtained a part of Burgundy on the return of Louis d’Outre-Mer; he now made use of the accession of Louis’ son Lothair, to have Aquitaine given him. But this time again, the royal sanction was powerless. William, duke of Aquitaine, received the invader in arms, and the war lasted for two years, when the duke of France died. He had named two kings and permitted a third to reign. Hugh Capet, his eldest son, inherited the duchy of France, and at the same time his father’s great influence, which he used in more moderate fashion.

He never came into hostility with Lothair throughout the latter’s whole reign. He looked on quietly while the king was active in the east, west, and north, trying to get his hands on Normandy, seizing some territory from the count of Flanders, which he had to give back, and making military excursions into Lorraine as far as the borders of Germany. This fruitless activity, this restless desire to attempt hopeless conquests, was in singular contrast with Hugh Capet’s power of repose. One would have said that the latter divined the future and that he disdained to forestall fortune by a single step in the belief of what would come to him.

In all this empty reign there is but one event that offers anything of interest. During an expedition in Lorraine (978), the principal object of his covetousness, Lothair came unexpectedly upon Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle), where Otto II was then staying. The emperor was about to sit down to table when the arrival of the king of France forced him to flee, and Lothair ate the dinner prepared for Otto. Otto swore to sing to him beneath the walls of Paris such a Halleluiah as the king had never heard; and what seemed like an angry piece of bravado was really carried out. The emperor appeared with sixty thousand men upon the heights of Montmartre after having ravaged the country around Rheims, Laon, and Soissons, and caused to be intoned by a number of clerks the Halleluiah with which he had threatened Parisian ears, and in the chorus of which this whole army joined.[3] Paris was avenged for this din; for in crossing the Aisne, swollen by storms, on his return, Otto lost his booty, baggage, and all his rearguard (980). It is true that he carried away with him the remembrance of the most formidable psalmody of which history makes mention, and the honour of having planted his lance in one of the gates of Paris; but these were rather frivolous achievements for the son of Otto the Great, and his Halleluiah would certainly have produced much more effect had he taken his sixty thousand men to sing it at Rome.f

The campaign, however, was successful in having raised mutual disgust between Lothair and Hugh Capet, the latter finding himself exposed to incursions and ravage from the idle ambition and provocation of Lothair, who was unable to support him by any force; while Lothair, on his side, saw that Hugh merely protected his own territories, without caring for Laon or Lorraine. Lothair, therefore, became reconciled to Otto, held a meeting with him on the Maas, and, as the price of the emperor’s friendship, waived his pretensions to Lorraine, at which his followers’ hearts corda Francorum, says the Chronicle of St. Denis,j were much saddened. If the descendant of Charlemagne gave up his claims upon Lorraine to Otto, it was idle for Hugh Capet to remain in hostility with the German emperor. The latter, after his pacification with Lothair, had gone to Italy; thither Hugh Capet sent, proffering friendship and alliance with Otto. The reply was an invitation to the duke to visit the emperor in Italy: a request with which Hugh Capet [20]complied, to the great anxiety and suspicion of Lothair, who, according to Richer,k used every effort to have Hugh’s return intercepted. The latter felt it necessary to pass the Alps in the disguise of a groom, and thus returned to his duchy.