“Bump—Slide—Splash!—and he plunged beneath the surface of the icy lake.”

—Page 3

Title: The adventures of Twinkly Eyes the little Black Bear

Author: Allen Chaffee

Illustrator: Peter DaRu

Release date: October 13, 2025 [eBook #77049]

Language: English

Original publication: Springfield: Milton Bradley Company, 1919

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Mairi, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

“Bump—Slide—Splash!—and he plunged beneath the surface of the icy lake.”

—Page 3

These little stories, which are intended both for children and their elders, are really true to natural science.

Disguised in fiction form, the reader gets a taste of biology, botany, zoology, and meteorology.

Such a taste may or may not lead the child to further study along those lines, but it will certainly give him a heightened appreciation of out-door life. Incidentally, he will have accumulated in the easiest possible way a great many facts that he will retain all his life.

The tales should also create a kindlier attitude toward our friends in fur and feathers, as well as instilling some of the stern virtues of the wilderness.

That these tales may be suitable for bedtime reading, no animal hero is ever killed. The big words are explained, and the adventure of each chapter harks back to the preceding in a way to refresh the memory of the reader who only takes time for a chapter an evening.

On the other hand, my readers have thus far included a large proportion of quite grown-up little boys.

| Chapter | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Twinkly Gets a Ducking | 1 |

| II. | Mother Black Bear to the Rescue | 4 |

| III. | A Stern Lesson | 7 |

| IV. | But He Learns It | 10 |

| V. | Mrs. Porcupine Shows Fight | 13 |

| VI. | Driven from Their Pond | 17 |

| VII. | Sink or Swim | 20 |

| VIII. | Writho, the Black Snake | 23 |

| IX. | “Whoof! Whoof!” | 26 |

| X. | The Better Part of Valor | 29 |

| XI. | A Tip on Thunder-Storms | 32 |

| XII. | A Wild Mother’s Love | 35 |

| XIII. | Twinkly Eyes Gets Even | 38 |

| XIV. | A Different Twinkly Eyes | 41 |

| XV. | There’s Many a Slip | 45 |

| XVI. | The Bee Tree | 48 |

| XVII. | Twinkly Eyes and Trouble | 51 |

| XVIII. | Twinkly Shows His Mettle | 54 |

| XIX. | Down But Not Downed | 57 |

| XX. | Twinkly Applies First Aid | 60 |

| XXI. | Mammy Cottontail’s Secret | 63 |

| XXII. | One of Twinkly’s Neighbors | 66 |

| XXIII. | Introducing Bobby Lynx | 69 |

| XXIV. | A Bunny Ball | 72 |

| XXV. | Twinkly Eyes Attends a Frolic | 75 |

| XXVI. | A Joke On The Little Black Bear | 78 |

| XXVII. | School For Bunnies | 81 |

| XXVIII. | A Boy and A Bear | 84 |

| XXIX. | The Tables Are Turned | 87 |

| XXX. | A Climbing Match | 90 |

| XXXI. | The Bear Gets The Best of It | 93 |

| XXXII. | The Little Bears Go Fishing | 96 |

| XXXIII. | Twinkly Again Meets The Porcupine | 99 |

| XXXIV. | A Good Sport | 102 |

| XXXV. | Bobby Lynx Learns A Lesson | 104 |

| XXXVI. | Twinkly Watches Again | 108 |

| XXXVII. | Foxy Counsel | 111 |

| XXXVIII. | A Jolly World | 114 |

| XXXIX. | Who Will be Sorriest? | 117 |

| XL. | Twinkly Eyes Plays Safe | 121 |

| XLI. | Twinkly Eyes Gets a Great Surprise | 124 |

| XLII. | Twinkly Eyes Plots Mischief | 127 |

| XLIII. | Twinkly Teases Unk Wunk | 130 |

| XLIV. | Twinkly Eyes Gets His | 133 |

| XLV. | Bobby Lynx Goes Fishing | 136 |

| XLVI. | A New Acquaintance | 139 |

| XLVII. | The Hired Man Drops a Match | 142 |

| XLVIII. | The Forest Aflame | 146 |

| XLIX. | In the Face of a Common Peril | 149 |

| L. | While There is Life, There is Hope | 153 |

| LI. | The Boy from the Valley Farm | 156 |

| LII. | Twinkly’s Fellow Refugees | 160 |

| LIII. | A Way for the Squirrel Family | 163 |

| LIV. | What Happened to Fleet Foot | 166 |

| LV. | Twinkly Eyes Goes House-Hunting | 169 |

| LVI. | At the Sugar Camp | 173 |

| LVII. | A Feast and a Fast | 176 |

| LVIII. | The First Snow | 179 |

| LIX. | Twinkly Eyes Goes to Bed | 182 |

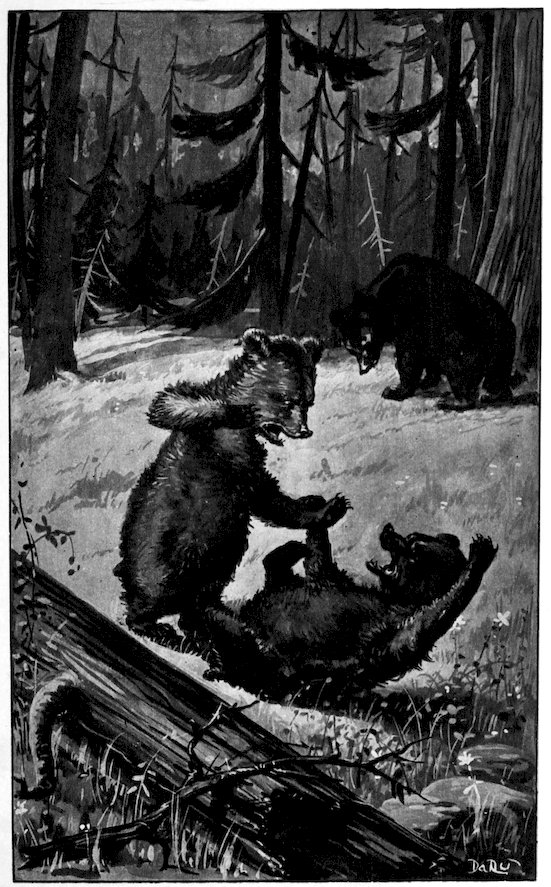

Two such roly-poly babies you never did see!

Mother Black Bear had named them Woof and Twinkly Eyes.—And you never in all your life met two such rollicking black balls of mischief as those two cubs!

Small wonder that Mother Black Bear needed such long black claws, long white teeth, and such a terrifying growl, with two such treasures to protect.

Why, she wouldn’t even let Father Black Bear come near them when they were so young, for fear some time they would plague him too far and make him lose his temper!

As the warm days of July ripened the blueberries along the slopes she used to lead the cubs down Mt. Olaf into the lowlands on berrying expeditions. And my! How they did enjoy these trips! How they stuffed 2themselves on the luscious fruit, snatching up great pawfuls of it, leaves and all, till their fuzzy sides rounded out like puff balls!

Then, too, there were often the most delicious sour-tasting ants under the logs and boulders that Mother Black Bear turned over for them! Life was one feast, what with the abundant food provided by Mother Black Bear herself and that found everywhere in the woods about them! Those cubs hadn’t a complaint to make!

True, they climbed right over one another in their eagerness to get the best of everything, and they growled little baby growls in imitation of their mother and squealed little piggish squeals of delight. But that was all a part of the game.

When there was nothing to eat in sight—or rather when they were too full to hold any more—they began to yawn and stretch and curl themselves up together like so many sleepy kittens.

Then when they had slept enough there were wrestling matches and boxing bouts and playing pranks on mother,—pulling her ears 3and clambering over her till she was forced to box their ears.

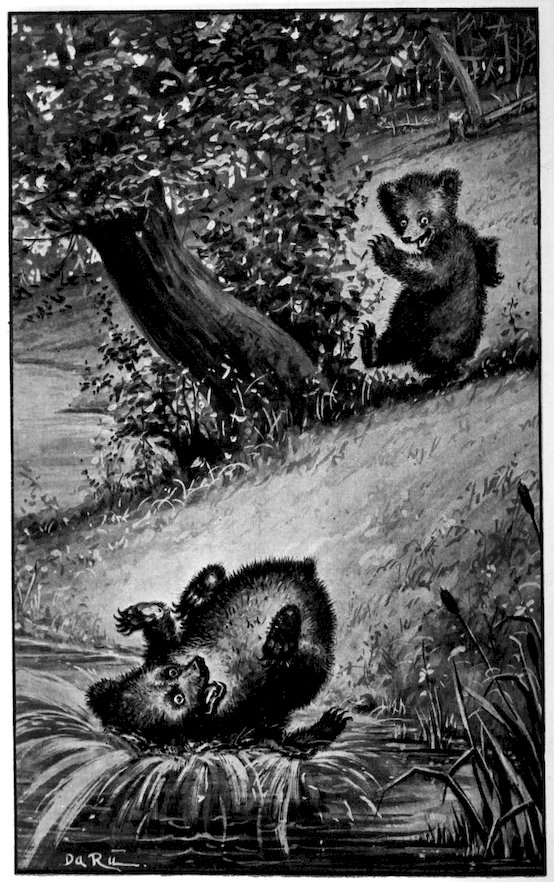

One lazy afternoon Twinkly was just nodding off to sleep, all curled up in a little fuzzy ball, when Woof came up from behind and gave him a shove. Now, as it happened, Twinkly had been lying at the top of a steep incline that led down to Lone Lake, and he went down that incline like a rubber ball, before ever Mother Black Bear could stop him. Bump—slide—splash!—and he plunged beneath the surface of the icy lake.

![[Bears]](images/i_012.jpg)

It is so wonderfully snug and comfy to be drowsing off on a warm afternoon, all curled up in a fuzzy little ball. So, at least, thought Twinkly Eyes, Mother Black Bear’s littlest cub.

But what an awful contrast to find oneself rolling down the bank like a rubber ball, till one came, bump, slide, splash, to the icy water!

And then to go down, down, down, gasping for breath and so horribly frightened that one thought the end had come!

It was certainly a terrible experience for the five-months-old cub, when his brother Woof gave him that mischievous shove!

Mother Black Bear was really frightened. Not that she was afraid of Lone Lake—not a good swimmer like Mother Black Bear; and not that she feared being unable to rescue 5the little fellow. But Mothers are always frightened when anything happens to their babies. Mother Black Bear was no exception.

She was just like any other mother in believing that her babies were the brightest and the handsomest and the most wonderful little creatures that anyone ever had.

So she didn’t even stop to think when she saw Twinkly’s little body rolling down the bank with its legs still wound around its nose. She just slid!—Afterwards there was a long trench where she had slid down that bank on her haunches!

She reached the water the very moment he did, and it wasn’t two seconds before she had plunged into the blue depths and grabbed the struggling youngster by the nape of his neck.

Dragging him straight back up the bank, she spread him out in the sunshine and began licking him dry, while he whimpered and coaxed for sympathy.

“This teaches you a lesson, young man,” she told him, when she had made sure he wasn’t hurt and wasn’t going to catch cold. “Never sleep on the edge of a bank. And 6Woof, don’t you ever again shove anyone over the bank like that,—not unless it’s someone you never want to see again,” and she gave Woof a good cuff on the ear to help him remember.

“But I’m glad, in one way, that this had to happen. Because it shows that you must learn to swim at once. Life is uncertain at best, in the woods, and you never can tell when you may need to know.”

“Ow! the water is too cold!” squealed Twinkly Eyes, backing away into the brush.

“We’ll go where it isn’t,” said Mother Black Bear firmly. “But we’re going this very afternoon. Come along!”

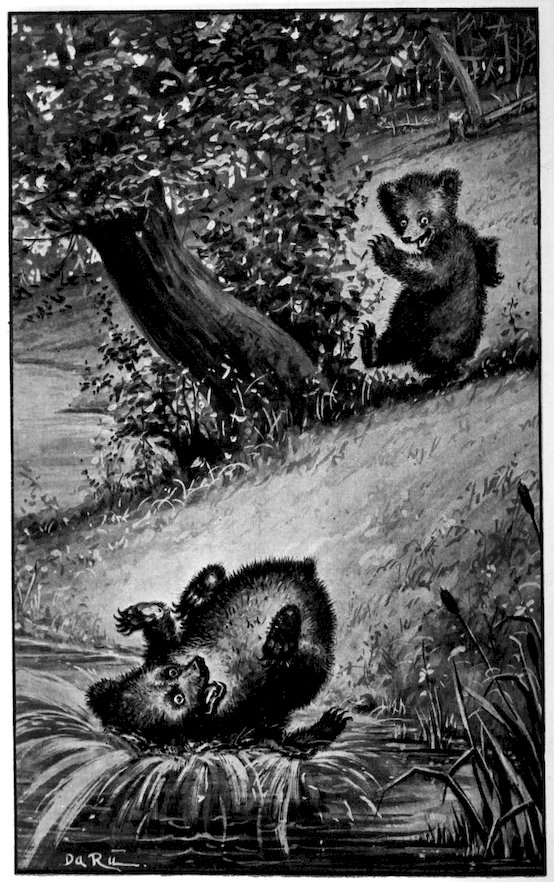

![[Bears]](images/i_015.jpg)

“Oo! I don’t want to learn to swim!” squealed Twinkly Eyes.

“Why don’t you?” asked Mother Black Bear, though she had quite made up her mind to give the cubs a lesson that very afternoon.

When Mother Black Bear had made up her mind to a thing, that was all there was to be said about it, so far as the cubs were considered.

Her word was law. Still, that did not prevent them from complaining at times. It is a certain amount of relief to complain, even when one knows it won’t do any good, isn’t it? At least the two cubs found it so.

“The water’s so-o-o-o cold,” wailed Twinkly Eyes, whose wet fur made him shiver.

“You won’t be cold, once you get to paddling about,” said Mother Black Bear. “Come on, quick! There’s a shallow place farther on where the sun has warmed the water.”

8She led the way through the bushes, Woof trotting obediently at her heels. Twinkly tried to run away, but he didn’t get very far. Mother Black Bear quickly found his hiding place.

“Come!” she insisted away down deep in her throat, with that rumbly sound that the cubs knew meant business.

Since the accident she felt it was not safe to let another day go by without making sure that they could at least keep from drowning.

“Come here!” she growled to Twinkly in no uncertain tone. That small imp simply didn’t dare disobey!

Woods babies generally are that way, and it is a lucky thing for them, let me tell you, or no telling what would happen to them!

Puffing and panting as they tumbled after her, the fat cubs soon found their mother seated on her haunches beside a quiet pool, where the sun danced through the leaves till the water seemed all mottled. Tall ferns grew all about them and every now and again a frightened frog would say, “K’dunk!” and go splashing to the bottom of the pond.

“Twinkly Eyes, are you coming?”

—Page 9

9“Now, then, just follow me,” said Mother Black Bear, when they had stared at the water for a moment. She waded off till she stood shoulder deep.

Twinkly braced himself firmly with all four feet and cocked one ear at the depths before him. His unexpected plunge when Woof had rolled him off the bank had shaken his faith in water, even for drinking purposes.

“Come!” commanded Mother Black Bear, and he knew he would have to wade in or get a good boxing. He whimpered, wondering which would be worse. He was a most unhappy little bear cub, for one so roly-poly!

Woof on the other hand, had waded in after his mother, and now—much to his own surprise—found his fat sides floating with just a stroke or two of his broad forepaws.

“Twinkly Eyes, are you coming?” called Mother Black Bear, wading back to where he stood.

“I don’t want to know how to swim,” wept the little black rascal, backing away still farther.

The next instant Mother Black Bear seized him by the scruff of the neck and dropped him straight into the pool!

He had been badly frightened, had Twinkly Eyes, the littlest bear cub, when Woof shoved him into the lake.

But underneath it all he had had a comfortable feeling that Mother Black Bear would somehow come to the rescue. There had never been a time, in all the five months of his existence, when she had not solved his troubles for him.

But now! To have Mother herself drop him in! It was too much! There was no hope anywhere. No one to rescue him! No way ever to get out again unless he found a way himself!

As this fact dawned on him he struck out with his broad fore paws, his nose turned to shore. So vigorous were his efforts that the first thing his untrained little body did was to go down, down, down to the very bottom of the pond.

11But he held his breath, because he remembered the time before, when he had swallowed so much water.

Somehow, he scarcely knew just how it happened, he found himself coming up again, safely enough.

“Wuhr! Splurf!” he gasped.

“Good work,” encouraged Mother Black Bear. “You see, you couldn’t drown if you wanted to!”

But already Twinkly Eyes had gone under water again, and this time he made the mistake of losing his nerve and trying to squeal for help. Of course that filled his nose with water, and that frightened him still more, till the first thing he knew, he was flapping about on the bottom of the pond with the most awful feeling he had ever known. His eyes he kept tight closed to keep the water out and not knowing where he had landed made it all the worse.

As an actual fact he hadn’t been under a minute before Mother Black Bear had pulled him out again. But to the five months cub, it seemed an hour. “Help, Help!” he gasped, the minute his nose came above water.

12His mother, seeing how terrified he had become, towed him gently to the bank and left him there to shake himself dry in the sun while she finished with his brother Woof.

This fat fellow had been enjoying Twinkly’s struggles as he paddled slowly about the pond, and his little black eyes danced with laughter.

But Twinkly had not given it up. That laughter was more than he could stand. “I’ll get you for that,” he growled in his high-pitched little voice, running around the bank to the point nearest his brother. With one mighty leap he landed fairly on top of Woof.

And Woof? Why, he simply took one deep breath and went under, and Twinkly went under with him. But this time he was too mad to be afraid. He forgot even to shut his eyes. Being able to see how near the bottom of the pond really was did more than you can imagine to give him confidence in himself.

The next thing Mother Black Bear knew, both cubs were swimming with all the zest of small boys.

But her pleasure was short lived. For rattling through the underbrush at that very moment came Mrs. Porcupine with three prickly babies, headed straight for their pond!

Yes, sir, Mother Black Bear’s pleasure was short lived. For no sooner had the cubs started off side by side across the pond than there was a curious rattling sound behind her, like the rattling of dry twigs.

She turned her head like a flash. It was Mrs. Porcupine, her quills rattling together as she walked. She was headed straight for the little pond, and Mother Black Bear knew there was going to be trouble.

Not that she would have cared, had she been alone. She would have given it up willingly enough. In fact, had she been alone, she would have preferred a larger pond for her swim.

But Mother Black Bear was not alone. She had fat little Woof and Twinkly Eyes to look out for. And it certainly was too bad, now that they were really making headway 14with their swimming lesson, to have to give up their pond. Twinkly had at last forgotten to be afraid, but if they had to give up the pond to Mrs. Porcupine, he might lose his nerve again, and all her work would have gone for nothing.

Yet learn to swim he must, before ever another accident befell him. Of this Mother Black Bear felt very certain.

She, therefore, eyed Mrs. Porcupine a bit anxiously; the more so when she spied the three little porcupines creeping along behind her.

Of all the folk that live in the Deep Woods, there is probably none more absolutely fearless than Mrs. Porcupine, and for a very good reason. She knows that nothing can so much as touch her without getting badly hurt on her barbed quills.

Where everyone else darts along the forest trails alert to catch the slightest sight or sound or smell that might mean an enemy, she strolls along with the utmost calm. She knows that no one can touch even her babies without getting hurt. For they are just as full of quills 15as she is, and their little quills are even sharper.

But if she fears no attack, neither will she harm other animals unless attacked. It is only when they come too near that she strikes at them with her barbed tail.

This afternoon she was headed for the self-same little pond that Mother Black Bear had selected, and for the self-same reason, as we shall see. When she saw Mother Black Bear and the two cubs, she didn’t stop for even an instant. She came right on to the edge of the pond as if there were no one already occupying it. She looked straight past Mother Black Bear as if she hadn’t been there at all, and grunted to her babies to climb on her back.

Mother Black Bear gave a growl. “We got here first,” said she, crossly. But Mrs. Porcupine pretended not to hear. She just went on into the water with her babies on her back—she had flattened down her quills for them—and from all the concern she showed, you would have thought she didn’t know the bears were there. That was her way of showing fight. She hadn’t a doubt in the world that they would give their places to her.

16“Come—quick!” Mother Black Bear called to her cubs, losing her nerve as the quilly creature allowed herself to float over on the side the cubs were on. “Quick, I tell you!—Scramble!”

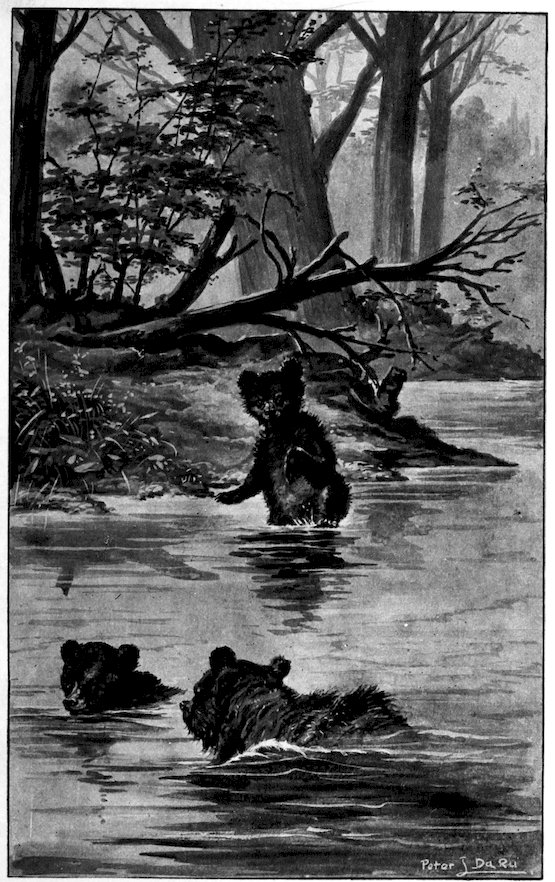

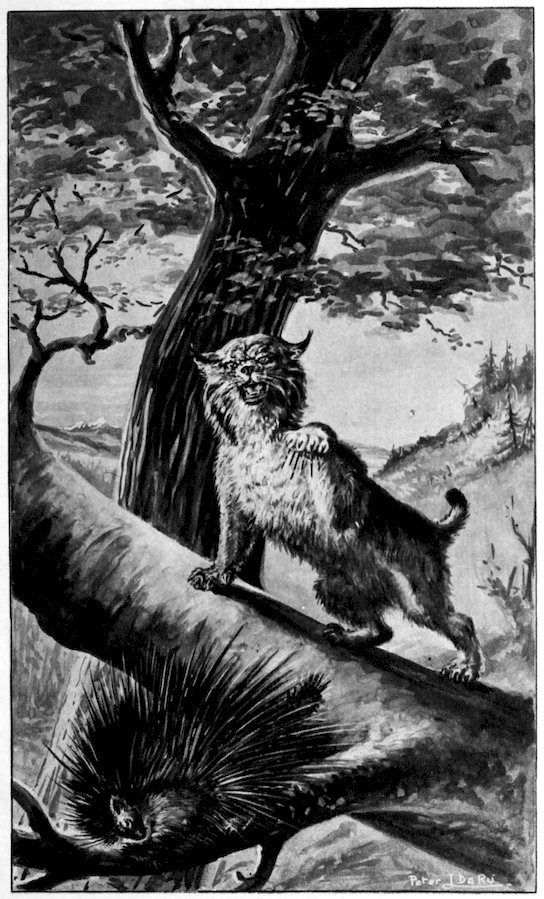

![[Bears & porcupine]](images/i_027.jpg)

Well it was for Woof and Twinkly Eyes, the fat bear cubs, that they had learned obedience.

For had they not scrambled out of the pond the instant their mother bade them they would have got badly hurt.

Mrs. Porcupine is not a neighbor to be treated with disrespect, as Mother Black Bear knew. Had one of the cubs gone an inch too near her prickly babies, their little tails would have gone slap, slap right in the faces of the cubs, leaving their barbed quills behind them.

That is why, even though Mrs. Black Bear felt she had first right to the swimming pool, she gave it up to Mrs. Porcupine the minute that lady entered the water.

The bear cubs didn’t in the least understand why they should be asked to scramble out of the pond so hastily; but they didn’t stop to ask why. They just scrambled!

18Once safely on the bank, Mother Black Bear hurried them to the shelter of the tall ferns and bracken. Here she posted them side by side where they could see the pond.

“Just watch,” she whispered, “and see—what you will see!”

The pair settled themselves on their awkward little haunches, eyes dancing with excitement. They did love a mystery!

Now Mrs. Porcupine is covered thick with quills, and these are as sharp as needles. When she meets an enemy she can make them stand out all over her back till she looks like a giant pincushion. But she can also flatten them down as smooth as a bale of hay.

Just on the edge of the pond, she flattened them all so nicely that the three baby porcupines were able to clamber aboard and sail out into the pond on her back.

“Gee! that must be fun,” thought Woof.

“I’ll bet they fall off,” thought Twinkly Eyes.

Mother Black Bear, who knew just what was going to happen, thought to herself, “I might have tried that myself if only I had thought in time!”

19“Unk wunk, unk wunk, unk wunk!” sang Mrs. Porcupine, pulling up the water lily pads and munching the juicy roots.

“Unk wunk, unk wunk,” mimicked the little porcupines, nibbling at the bits she took in her mouth to see what they were like.

Lower and lower swam Mrs. Porcupine, till the babies had to climb higher on her back to keep from getting wet. Mother Black Bear’s eyes fairly twinkled at what was about to happen.

Lower still sank the living raft, till it was half under. The babies didn’t mind, once the surprise of getting wet was over. But the raft was sinking lower still. Now Mrs. Porcupine just had her nose out.

Then—suddenly—she dived clear under!

![[Porcupine]](images/i_030.jpg)

“Ooh! They’ll drown!” squealed Twinkly Eyes, as Mrs. Porcupine went under water with her babies on her back.

But they didn’t!

It had come so gradually, for one thing, that they weren’t the least bit frightened. Mrs. Porcupine has simply flattened her quills down smooth and taken them on her back while she swam out for lily pads. They had nibbled the pads and thought they were having the finest kind of ride.

As Mrs. Porcupine went deeper into the water and the babies got their feet wet, they scarcely noticed, so warm was the water in the little pond and so sure were they that Mother was right there.

When she sank till they were all half under, they only thought it fun. They had no idea of what was going to happen before they reached dry land again. Had they known what was going to happen, they would have 21been dreadfully frightened. In fact, they wouldn’t have ventured out at all, even on their mother’s back.

It is often that way with people. If they knew just what was going to happen next, they would lose their nerve entirely. Yet generally when it does happen, it isn’t nearly so bad as they feared. Sometimes it isn’t bad at all.

If the baby porcupines had had any idea that their mother was going to dive clear under water with them, they never in this world would have ventured one foot from shore. But that was one of the things Mrs. Porcupine kept to herself. She was very good at keeping things to herself, was Mrs. Porcupine, and it saved her a lot of trouble.

At any rate, from being in the warm pond water with their feet safely planted on Mother’s back, the babies suddenly found themselves in the water with nothing under their feet but water, and Mother coming up away on the other side of the pond.

The two cubs, watching from the bracken, smiled from ear to ear, their little black eyes dancing with enjoyment.

22“Come!” said Mrs. Porcupine, swimming about just out of reach. And the three baby porcupines simply had to strike out for themselves.

To their own very great surprise they found that their hollow quills floated them beautifully. In fact, it is easier for a porcupine to swim than it is for almost any other animal.

“What do you think of that?” Mother Black Bear asked her cubs.

“Pretty slick,” said Woof.

“Gee, I wish you’d taught me that way,” said Twinkly Eyes.

“I’m going to teach you something else now,” said Mother Black Bear, “Come!” and she started up a water maple that grew hard by.

“Oo—ee! I can’t climb,” Twinkly was just beginning, when he heard a curious rustling in the grass behind him. Turning his head he spied Writho, the Black Snake, making straight toward him!

“He found himself staring straight at Writho the black snake.”

—Page 23

Now Twinkly Eyes had been perfectly certain a moment before that he could never climb that tree after his mother.

The next instant there had been a queer little rustling in the tall grass, and he found himself staring straight at Writho the Black Snake.

He had never seen a black snake before, but he would have known just from the smell of him that he was some one to avoid.

“Climb! Climb!” rumbled Mother Black Bear from the water maple. Had he needed warning, her anxious tone would have been enough.

And Twinkly Eyes climbed—my, how he scrambled up that tree! He didn’t once stop to wonder if he might fall off. He just drove his sharp little claws into the bark and up he went, faster than he would ever have dreamed possible!

24Mother Black Bear smiled to herself. She had learned something from watching Mrs. Porcupine dive from under the little porcupines. She had learned that if a youngster is given his choice of sinking or swimming he will find a way to swim. Of course, she could have leaped to the rescue the instant Writho became dangerous. She wouldn’t have let him hurt her cub! But when she saw him wriggling through the grass she knew that Twinkly Eyes would need no coaxing to take to the tree. In that she was not mistaken.

Meantime, where was Woof? He had climbed the tree on the other side of the trunk, quite without urging, and he now came out on a limb some distance from the ground.

“Good boy!” said Mother Black Bear, patting him fondly.

This was too much for Twinkly Eyes. Had not Woof caused all of his troubles that afternoon by rolling him into the water? Then, too, he felt that he was a good boy himself for having scrambled up the tree so readily. To have his brother get all the praise!

Fat little Woof was just licking up a delicious big black ant when Twinkly crept up 25behind him. The next instant he received a blow in the ribs that fairly knocked the breath out of him.

The wrestling match that followed sent both cubs spinning from their branch. But so fat they were, and so roly-poly, that they minded their fall about as much as they would have a box on the ear. They just rolled over and over and over in each other’s arms all over the ferns and bracken, still punching and biffing one another.

In fact, they rolled about so fast that the first thing they knew they had come down on something cold and slippery that writhed out from under them with an angry hiss.

Woof, ever the quicker of the two, was back up his tree in a twinkling, but poor Twinkly Eyes was for the second time staring straight into the angry eyes of Writho. And the snake was between him and the tree!

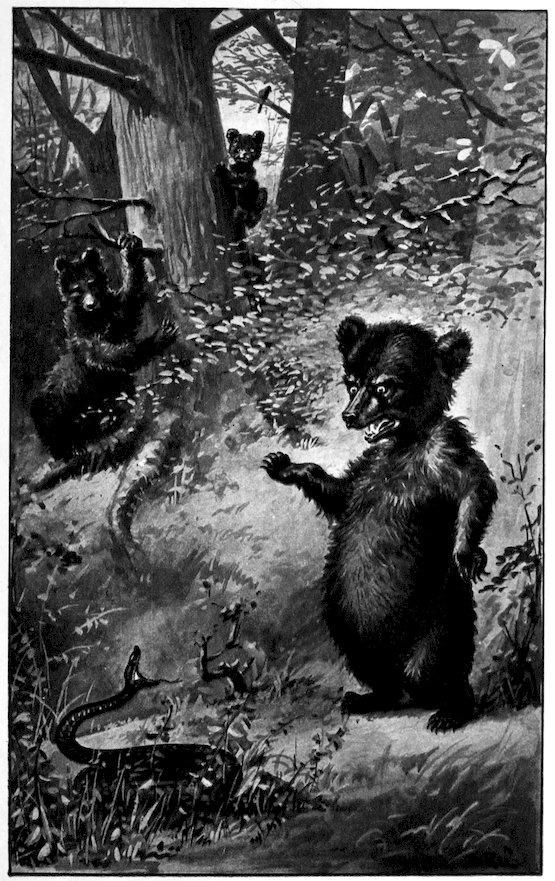

![[Bear & snake]](images/i_038.jpg)

“Trouble again!” thought Twinkly Eyes, as he found himself staring into the angry face of Writho, the Black Snake.

“You rolled right on me,” scolded Writho. “Haven’t you any consideration for other people at all?”

“I’m sorry,” pleaded the cub, “I had no idea—”

“You want to look where you’re going,” scolded Writho. “I could bite you for what you did!”

“Oh, please don’t,” squealed Twinkly Eyes, retreating toward the pond, as Writho wriggled closer. Then he remembered Mrs. Porcupine and her family, whom he could hear grunting “unk wunk” as they nibbled lily pads. It would never do to back up too close to those prickly creatures. Neither would it do to turn his back on Writho, whose red forked tongue hissed at him from between two of the sharpest looking fangs he had ever seen.

27“Truly, I didn’t mean to step on you, Mr. Writho,” said the little bear, and his voice sounded very sorry and very much afraid.

But he kept backing around nearer and nearer his tree, until it was right behind him.

“Whoof, whoof!” he suddenly roared at the snake, stamping a fore foot loudly.

Writho was so amazed that he stood stone still, and in that instant the cub had raced up his tree in safety.

“Why didn’t you think of that before?” laughed Mother Bear. “Writho is an awful bluffer. He didn’t really mean to bite at all. The trouble was, it hurt his pride to be stepped on.”

“So was I a bluffer,” confessed Twinkly Eyes.

“No, you weren’t, my son. You could have killed him with one blow on the back of his neck, had he really tried to bite you.”

“Wish I’d known,” sighed the cub. “I certainly had a bad scare.”

“Now climb up here in the sun and dry your fur,” said Mother Black Bear, “while I talk to you. As a rule I don’t advise bluffing. I don’t advise making any threat you cannot 28back up with tooth or claw. Because once people find you out, they will have no more respect for you.

“But with a coward and a bluffer like Writho it often works. Most snakes are cowards. All they want is to be left in peace. They’ll only attack a big animal like you when you step on them and make them mad. They hiss and stick out their tongues at us just for a bluff.

“I’ve never seen Writho attack any animal larger than a hare or a chipmunk in all my life.

“But you’ll do well to keep clear out of the way of Mrs. Porcupine and the whole porcupine family, big and little,” and she peered back into the pond, where the three prickly babies were just following their mother out of the pond.

“Hello, there! I do believe they are making for our tree!”

![[Porcupines]](images/i_041.jpg)

Mother Black Bear sighed as she saw Mrs. Porcupine making for her maple tree.

“If she wants it, I suppose she will have to have it,” she told the cubs. “Wisdom is the better part of valor.”

“What is wisdom?” asked Woof, the larger of the fat cubs.

“Wisdom,” said Mother Black Bear, “in this case is giving up our tree rather than having a fight with Mrs. Porcupine about it.”

“But we got here first,” shrilled Twinkly Eyes, the smaller cub. “She has no right to it.”

“That makes no difference with Mrs. Porcupine,” growled Mother Black Bear. “She has no sense of right and wrong. She is too well armed with those awful quills to value other people’s rights. She just about has things all her own way in the Deep Woods, 30because few of us care to fight with her. It’s lucky that all she wants is her own stubborn way. She is a ve-ge-tarian, you know. She eats no meat.

“Just why she should decide on our maple tree—of all the trees she has to choose between—is more than I can see. Though, of course, it IS easy for the little ones to climb.”

“Will they have to climb up there in the sun and dry off, too?” asked Twinkly Eyes.

“Where else would they get any sun?” asked Woof, gazing up at the forest roof. In this part of the woods the trees all grew so high and so close together that their upper branches interlaced, so that one only got a patch of the sky here and there.

Woof, peering through the green gloom, could see Mrs. Porcupine and the three little Porcupines slowly making toward their maple.

“Don’t let her have it,” he begged Mother Black Bear, who loved nothing better than to see a scrap. “You could lick her, Mother!”

“Well, no, I shouldn’t like to try it, not with you youngsters along,” she answered, swinging her long head from side to side uneasily, as she prepared to lead the way 31to the ground. “Your father might, but I shouldn’t like to try it.”

“Why, the old ‘Unk Wunk!’”

“First she chased us out of our pond, now out of our tree,” complained Twinkly Eyes. “Can’t we bluff her off, the way I did Writho, the black snake?”

“I should say not,” said Mother Black Bear in alarm. “Nothing on this earth could frighten Mrs. Porcupine. Come along here,” and she reached up and gave each cub a spank that sent them hurrying to the ground. It was not a moment too soon, for as they landed on one side of the trunk the Porcupine family started up the other, though for all the sign they made, Mother Black Bear and the cubs didn’t even exist.

But the latter’s peace of mind was short-lived.

“We are certainly going to have a thunder-storm,” exclaimed Mother Black Bear, as she sniffed the air.

“Are you scared, Mother?” asked Twinkly Eyes.

“Well, that all depends on how fast you cubs can beat it out of these woods!”

“No sir-ee! I certainly don’t like the looks of things,” said Mother Black Bear, hurrying the cubs through the green gloom of the forest aisles.

“Mrs. Porcupine is welcome to our maple tree! There’s going to be a thunder-storm, and it’s going to be a big one,” and she pointed her nose skyward to sniff.

Out over the lake the black clouds were banking up over the sky at a great rate. The cubs crowded close to her sides, as the rolling and rumbling of clouds banging together came to their ears.

The air was full of the peculiar fresh odor you always notice before a shower.

“Are you scared, mother?” Twinkly Eyes kept asking.

Mother Black Bear glanced about, this way and that.

33On every side, as far as she could see, there were just five or six kinds of trees, oaks, poplars, willows, maples, elms and ash trees, all growing to nearly the same height. Here and there was a blackened trunk standing gaunt and naked where the lightning had struck. For these trees, as every woodsman knows, are the very ones most likely to be struck.

“I don’t like to get caught in these woods,” insisted Mother Black Bear, starting off at a brisk pace along the southern border of the lake. It was all the cubs could do to follow, paddling along on their chubby legs with panting breath and red tongues lolling from their little black muzzles.

“I can’t keep up,” whispered Twinkly Eyes who brought up the rear.

“Lightning waits for no one,” rumbled Mother Black Bear, refusing to slow down even a mite. A nearer crash of thunder, as the first big raindrops began to fall, sent her forward on the run.

“Where are we going?” asked Woof, who rather enjoyed the excitement.

34“We’re going to find the kind of trees lightning doesn’t strike,” Mother Black Bear flung behind her without stopping.

“Beech, birch, chestnut, basswood!” She broke into a run.

“Oh, mother—those white birches over behind Pollywog pond,” gasped Woof, trying his best to keep up with her through the pelting rain.

“Just where we are headed,” rumbled Mother Black Bear. “If only—we can reach them—in time!”

A blinding flash of lightning darted down the trunk of a huge old oak to the left. This time the thunder seemed to come at the same instant.

Mother Black Bear looked back over her shoulder. Woof was close behind,—but where was Twinkly Eyes?

She turned instantly to find out.

At the instant of the lightning flash that came so near, Mother Black Bear had been racing for dear life to get to the safe shelter of the birch grove.

She knew that lightning is not so apt to strike in a birch grove as in the giant oaks where the storm had found them.

But then the cubs had both been close at her heels. The instant she missed Twinkly Eyes she turned back to find him. He lay flat on the ground, his heels in the air, just where he had tumbled when the big crash came. He was so frightened that he could scarce regain his feet. His legs trembled till he could go no further.

Mother Black Bear tried her best to carry him in her mouth, but he was so fat and roly-poly and wiggled so at every clap of thunder that she had to give it up.

36Woof, who was close at her heels every minute, was all for climbing the tallest tree they could find, but Mother Black Bear selected a comparatively open patch with no tree higher than its neighbors; and there she crouched beside the cubs, covering them with her own body when the big drops turned to hailstones.

“It’s bad to be caught among the oaks in a thunder storm,” she told the cubs as they waited. “It’s bad to be caught under any tall tree. Better far, when a storm comes up, abandon your tree and wait out in the open where there is nothing to attract the lightning.

“There are only two things in all the Deep Woods that a bear ought really to be afraid of, and one of those is lightning—for there’s no fighting back,” said Mother Black Bear.

“What is the other thing you are afraid of, Mother?” asked Woof, “Mrs. Porcupine?”

“No, I’m not afraid of Mrs. Porcupine, if I did think best to let her have our tree. I just believe in keeping out of her way, that’s all.”

“Then what is the other thing you are afraid of?” asked Twinkly Eyes, whose 37trembling had ceased as the storm passed around to the south.

“Men with guns,” said Mother Black Bear im-press-ive-ly. (When you say a thing im-press-ive-ly, you try to impress it on other people’s minds, so they will never forget.) “You can’t fight men with guns. That is once when a bear just simply has to run away.”

“That would suit Twinkly Eyes, all right,” laughed Woof, poking his brother in the ribs. “Eh, there?”

The smaller cub gave a growl. “Just because I didn’t want to learn to swim!—I’ll teach you to be afraid yourself, one of these days! You see if I don’t!” he growled in his baby throat, as he thought of how Woof had pushed him into the lake.

He’d get even, somehow, Twinkly told himself, seizing his brother’s nose; and as the fat cubs clinched the storm was forgotten.

Mother Black Bear gave them each a cuff, then stalked away, leaving them unprotected in the pelting hail.

Such clawing and biting and squealing as followed you never did see!

The clouds rolled away toward Mount Olaf and the hail changed to rain, and the rain suddenly gave way to a red glow in the West where the sun goes to bed. But the cubs fought on.

Mother Black Bear stood and watched, feeling that they were gaining a training in the use of their muscles that would stand them in good stead later on. She would interfere only if she saw that one of them was really getting hurt.

“Such clawing and biting and squealing—you never did see!”

—Page 38

39Now just behind the circle of brushwood in which they had sought safety from the thunder storm there was an old root that sloped straight down a 15-foot incline.

To this Twinkly was trying his best to shove his brother, and though he was somewhat lighter than Woof, weighing a bare six pounds to Woof’s six and a half, he was also quicker on his feet, and he did finally succeed in backing the other up to the incline.

True, there was no lake at the bottom, as there had been when Woof shoved him down the bank in his sleep, but at least the teaser should find out what it felt like to be sent rolling in a helpless ball.

With a sudden wrench he sprang free, just as he had the larger cub humped up at the top of the slide, defending his head with all four paws. The result was that fat Woof rolled like a rubber ball straight down the incline, whirling around and around till he came up, plunk, against the trunk of a tree.

But to Twinkly Eyes’ surprise Woof not only picked himself up with a laugh of enjoyment, but he raced back up the slope to try 40it again, ducking his tiny head and doubling up into a ball for the purpose.

Again and again he tobogganed down that slope, Twinkly staring after him wide-eyed. So that was the way he had thought to get even!

He was so surprised that he stood clear up on his hind legs, staring. Then he tried it himself!

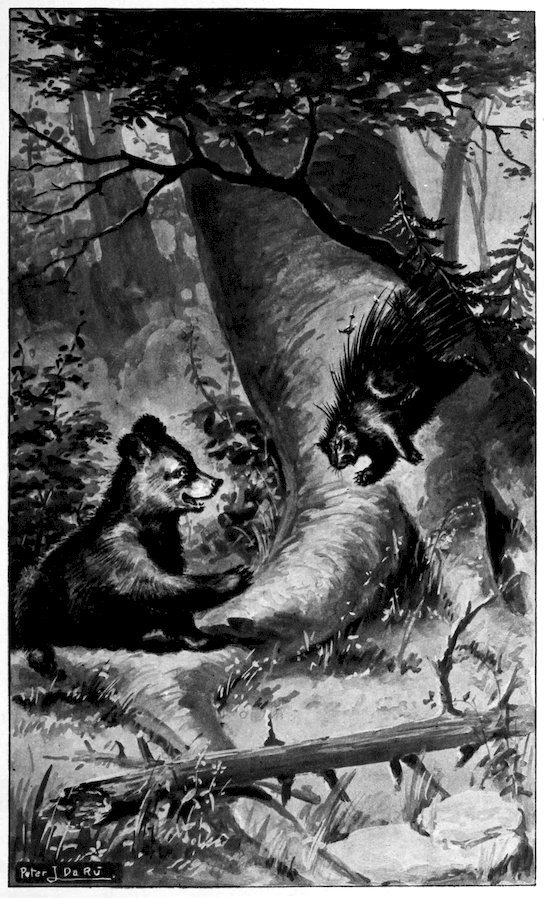

![[Bears]](images/i_055.jpg)

Summer passed, with its lessons. And thanks to Mother Black Bear, there wasn’t an animal his size in all the Deep Woods that Twinkly Eyes was afraid of, when at last the long sleep came.

Emerging in the spring from the snug den in which he and his brother had drowsed away the long months, snuggled close into their mother’s furs, he was a different Twinkly Eyes.

He was both older and wiser,—and oh, so much thinner! His voice had deepened, too.

Soon he began hunting by himself. For Mother Black Bear now had two new little roly-poly cubs. And sometimes he didn’t find much to eat.

One morning he met Tattle-tale the Jay.

Now Tattletale was not really a mean fellow: he was just mischievous. He loved to play 42pranks. His tattling was for the most part a warning to the smaller forest folk of the approach of their enemies, Cooper the Hawk and Bobby Lynx, and Mother Black Bear.

When any of these were out for game, he would fly from one tree-top to another just ahead of them, screaming his warning at the top of his lungs, till there wasn’t a hare or a wood mouse anywhere that did not have a chance to run to hiding.

Now, though, he was so furious with the Red Squirrels for smashing two of Mrs. Jay’s pretty eggs that he made up his mind to get even. It never once entered his head that he was the first offender. For if he hadn’t begun the quarrel by robbing Shadow Tail, of his poor little hoard of seeds, Mother Red Squirrel would never have harmed the eggs.

If he had thought, he might have called it square, instead of making a bad matter worse. But Tattletale didn’t stop to think. All he could see was his own grievance. Besides, Mrs. Jay felt so bad about the eggs that he had to promise her something that would soothe her ruffled feelings.

43The very next morning, just as the first pink rays of the rising sun began glinting off the dew-wet leaves in the open places, he was flitting about after grasshoppers when he spied Twinkly Eyes, the little Black Bear, slouching along the little trail to Pollywog Pond.

“Good morning, Mr. Bear,” he chirped.

“Good morning,” rumbled the yearling cub, peering and blinking into the treetops at the flash of blue wings. Twinkly’s eyes are very poor, though his ears are so sharp and his nose sharper. He could hear the squeak of a wood mouse a long way off, and he could tell just by sniffing whether or not he would find those delicious sour-tasting ants underneath a fallen log.

“How do you find the hunting these days?” asked Tattletale politely.

“Oh, nothing extra—nothing extra at all,” grumbled Twinkly Eyes. “Haven’t had much of anything but roots and frogs so far this spring. Blueberries aren’t ripe yet, there won’t be any nuts till fall, to say nothing of green corn. And a bear of my size can’t make much of a living off of grubs and mice, of 44course. I do wish I could find a bee tree!”

“I don’t suppose, now,” ventured the Jay, “that you’d be interested in a nest of young squirrels?”

“Try me—just try me once!” chuckled the little bear.

“All right; see that old oak?” directed Tattletale, flying on ahead.

![[Bear]](images/i_059.jpg)

Fortunately for most of us, there is many a slip ’twixt the cup and the lip, which only means that many a plan is laid that doesn’t pan out just as it was expected to.

It was so in the case of Twinkly Eyes, the little Black Bear. It was lucky for him and it was lucky for Shadow Tail, the Red Squirrel, and it was lucky for Tattletale, the Jay. For if Tattletale had really been the means of leading the little Bear to Mother Red Squirrel’s nest, she’d never have forgiven Tattletale, but surely would have gone back and broken the rest of the eggs on which he had left Mrs. Jay sitting so patiently.

And if Twinkly Eyes had really caught the squirrel babies, as he wanted to, he’d have made such an enemy of every squirrel in all the woods around that he’d never have known peace again. For they’d have followed through the treetops, everywhere he went, 46scolding him and warning the mice and frogs and snakes to beware of his coming.

But there was one thing Tattletale the Jay had not stopped to consider when he led Twinkly Eyes to the tree in which Mother Red Squirrel had located. He didn’t stop to realize that the squirrel babies were far too clever to be caught napping.

No sooner did Shadow Tail and his brothers hear Twinkly’s great claws scrambling up the tree trunk than they promptly leaped into another tree, and the bear had his climb for his trouble.

Sliding down the trunk like a bag of meal, he tried the next tree, on the Jay’s advice, but with the same success. The little squirrels raced from branch to branch around him, hurling taunts and laughter at him, till he really began to be angry. But it was Mr. Jay he was angry with!

“See here,” he grumbled, “I do believe you have just been playing a prank on me!”

“Oh, no, I assure you,” began Tattletale, flying down beside the bear.

But Twinkly Eyes would have none of it. He suddenly remembered how often the Jay 47had warned his quarry away from him by flying just overhead and shrieking, “Look out, look out! A bear!”

With this memory bitter upon him, he made a sudden slap at Tattletale with his great barbed paw. But the bird was too quick for him. He was back in the tree tops before the little Bear knew what had happened.

“All right,” said Tattletale, “if you feel that way about it! You can’t do me any harm,” and he was off with a flash of his blue wings.

For a while Twinkly wandered on, hungrily listening for the squeak of a shrew mouse. Then suddenly he pricked up his ears. It was—it certainly was the buzzing of a honey bee! It came from a little wild rose bush.

Now a honey bee meant but one thing to Twinkly Eyes—a bee tree, and a bee tree meant honey. He would follow the sound when the bee flew home, and then—Um! His mouth fairly watered.

As Twinkly Eyes, the little Black Bear, heard that buzzing from the wild rose bushes, he forgot his troubles with the Jay.

Indeed, he fairly danced for joy. For had he not been waiting greedily all spring for the sound of a honey bee?

Now he would find the bee tree, and feast on honey to his heart’s content! For of all the good things in the great green woods—mice and berries and grubs, and fish and frogs, and sour-tasting little red ants, to say nothing of juicy roots, and the nuts of autumn—he loved nothing half so well as honey.

He had had a taste just once, but he had never forgotten!

While wrestling with his brother one day the spring before, when they were three months cubs, their mother had suddenly called them to follow and trailing straight after a bee her sharp ears had discovered, she led them 49to a hollow tree where the yellow comb lay in great fragrant chunks.

Twinkly Eyes licked his chops at the memory. Then Mother Black Bear had shown them how to hide their noses and shut their eyes when the bees came too near these unprotected places. Otherwise the angry insects could try as hard as they would, and they could not reach through the glossy fur.

Twinkly Eyes had escaped without a sting and he had decided in his infant mind that Mother was altogether too cautious for any use.

This year Mother Black Bear had a new set of cubs to teach and train, and Twinkly and his brother were living in bachelor quarters.

A moment Twinkly watched, and then the bee had all the honey she could carry. Buzzing happily, she started back through the woods toward an open glade on the other side of Pollywog Pond.

Twinkly followed, his sharp ears guiding him where his little near-sighted eyes could not, till his eager sniffings brought to his 50nostrils the first faint fragrance of the bee tree.

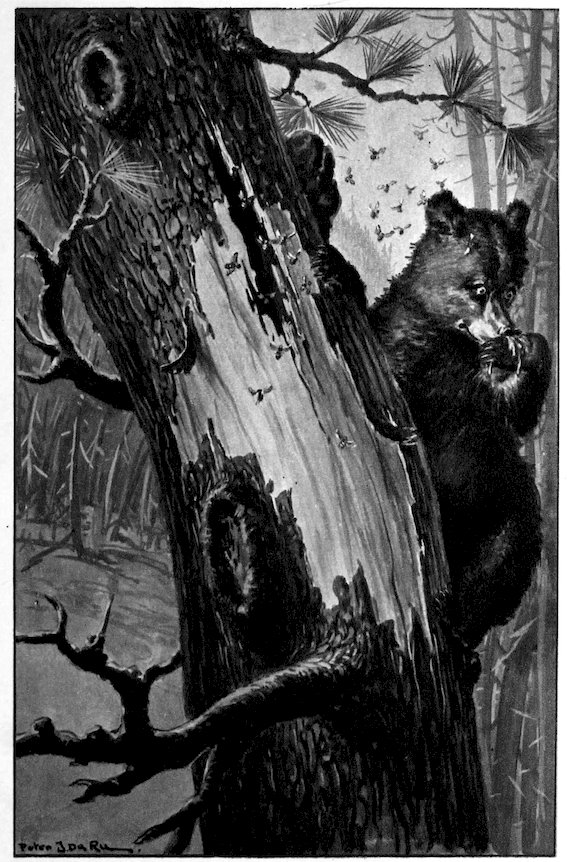

Now other bees began to join the first one, till there was quite a little swarm headed for a hollow pine—a great, gaunt tree that had been hollowed out by lightning and now stood, scarred and blackened, on the top of a hillock.

“It’s a pretty good world, after all,” Twinkly Eyes decided, as he ambled up the slope.

![[Bees]](images/i_065.jpg)

“Yes, sir, it’s a pretty good world after all,” mused Twinkly Eyes, the little Black Bear, as he neared the bee tree.

Certainly everything about him promised a blissful day.

Warblers sung happily from every treetop, swallowtail butterflies danced above the wild rose bushes, and puffy white clouds shadowed the blue of the sky. There was just enough breeze to feel good as it ruffled his glossy fur. Then too, blueberries were nearly ripe, and the fragrance of wild grape vines promised delights to come.

But best of all was that heavy hum of a thousand bees carrying their golden honey into the hollow pine tree.

It was a tall old pine that had once been struck by lightning. One side was scored and blackened; near the top was a small dark 52hole, into which the returning bees poured steadily, while others poured steadily out again.

And oh! The wonderful odor that came from that hole! How it made his mouth water! There was nothing whatever to indicate that trouble might be near.

Now Twinkly Eyes had been in his mother’s charge the first time he had climbed a bee tree, and thanks to her warnings he had escaped unstung. It seemed to him now, as he thought of that wonderful day, that his mother had been altogether more cautious than there was any need of being.

But, no sooner had his claws begun to rattle upon the trunk of the hollow pine than the buzzing grew louder, and it seemed to Twinkly Eyes that there was a new note in it, quite different from the contented hum he had heard before. In fact, he began to wonder if there might be trouble after all. Still, he was not one to give up at this point! The sweet comb would be worth a lot of trouble! He scrambled faster, till one paw clutched the edge of the hole.

53Instantly the bees had settled thick upon his coat, trying their best to ram their red-hot stings into his glossy fur, but it was too thick for them, and Twinkly minded not at all.

Suddenly a red-hot needle struck him on the lip.

“Hoof—woof!” he protested, licking the burnt place. It hurt dreadfully.

Another needle pricked him, this time on the tip of his protruding tongue. This time Twinkly slapped so angrily that he flattened the bee, but it didn’t help his tongue, and his lip began to swell.

But there was no time to think about that. As he reached for a better hold, his paw tore a strip of the rotten bark away, and he had to shut his eyes and cover his nose with his paw while the angry swarm darted about his head in a buzzing fury.

No, indeed, Twinkly Eyes was not the Bear to give up just when he had one paw in the honey!

For the same paw that covered his nose from the angry insects, as he clung to the old pine, also brought to his tongue the most wonderful flavor he had ever known.

All the smarting and burning in tongue and lip could not spoil that flavor. He must have more of it, and that at once! For what had he watched and waited these long weeks if not for this very chance? Was he to be driven from the feast by a little brown insect with a barb in the end of its tail?

No indeed! No mere honey bee could make him turn back now.

Struggling still nearer that dark round hole from which the fragrance issued he drew a long breath and plunged in.

“My how his little black eyes danced with the delight of it!”

—Page 55

55Another needle point, red hot, stung him, this time on the lid of his right eye; and if the sting on his lip had tortured him, this was something far, far worse. He whimpered unhappily, and rubbed the sore place gently against his upraised foreleg.

My! how those bees did buzz and threaten him! But they couldn’t reach him through his fur, so long as he kept his face protected. He clung to his hole just the same, and by and by he dug his free paw deep into the honeycomb within and brought a great luscious chunk to his mouth.

Now that their little store was really disappearing, despite all they could do the bees at once began setting to work to rescue some of their treasure. Still there were enough left on guard to give Twinkly cause for watchfulness.

He grabbed another mouthful, and gulped it down, with the bees that still clung to it. My, how his little black eyes danced with the delight of it!

If only that eyelid would not smart so dreadfully! It was swelling, too, and he could hardly see out of that eye at all.

56His tongue was swollen, too, on the tip end where the bee had stung him, till it began to feel so big he feared he wouldn’t be able to close his jaws in another minute.

But he would not give up! Not Twinkly Eyes! Not till every last smell of that honey was gone! Now that he had risked it thus far, he reasoned, he might as well have something to sweeten his pain.

The little Black Bear was nothing if not persistent, and persistence is a virtue that stands one in good stead in the wilderness.

Then suddenly a most surprising thing happened.

![[Bear]](images/i_073.jpg)

A great many things can happen to a bear cub that he doesn’t expect to happen.

It was so with Twinkly Eyes. No sooner had he made up his mind to enjoy his feast in the bee tree in spite of his stings when—zipp! Off came a great long strip of the rotten bark! And while it disclosed even more of the yellow comb, it also happened to be the very strip of bark to which the little bear was clinging with his left forepaw.

Now his right paw was deep in the honey at the time, and a bear cannot cling in the top of a pine tree with his hind legs alone. The result was that there was a wild scrambling, then the sound of claws rattling noisily over the bark that they could not get a grip in, and finally the snapping of a hazel bush that stood just beneath.

58Twinkly Eyes had come down like a bag of meal!

He gave one big grunt, then a series of whimpers. For even if you are a yearling cub and your bones are padded with great heavy muscles and thick fur, it isn’t the most comfortable thing in the world to fall crashing out of the top of a bee tree.

Fortunately for Twinkly Eyes, he had hugged the trunk just enough, as he descended, to break the fall. Then, too, he landed on the hazel bush, which sprang under him in a way still further to soften his landing. But even at that, things whirled about him for a few minutes there.

Then he arose, a bit groaningly, it is true—what with his swollen eyelid and his burning lip and tongue. And what do you suppose he did next?

Most anyone would have felt that he had had enough adventure to last him for some time. But not so Twinkly Eyes! That was not the kind of mettle he was made of!

Though his little near-sighted eyes could not see the crack that now reached for nearly his own length down the hollow trunk, his 59keen brown nose told him that the scent of honey was even stronger than before. And, though his black sides already stuck out, his mouth still watered for more.

He sniffed longingly, then tried to soothe his swelling eyelid with his paw. He certainly felt bunged up, to say nothing of the jolting he had just received. He couldn’t see out of his right eye at all now, and there was a lump the size of a walnut on his lip.

But, oh, the delicious fragrance! The honey he had waited a year to find! In his long winter’s sleep he had dreamed of it more than once, and licked his paws in vain. Throughout the lean spring, as he grubbed for roots, he had listened in vain for the very buzzing that now filled the air all about him.

It was too much! He would try again!

There was no resisting that odor of wild honey dripping from the comb—not to one who loved wild honey like Twinkly Eyes, the little Black Bear!

He must have more! His eye swollen shut, his tongue stinging like fury with the hot flame of the bee’s sting, he pulled himself together and started up the tree again.

The bees were working like mad to carry away at least a part of their store before he should devour it; but they were not too busy to try once more to drive him off. A fourth bee gave up his life to thrust his barbed and poisonous sting into his nose. But Twinkly Eyes only became the more stubborn in his desire to clean out the tree.

Bracing himself in the crotch of a branch just beneath the opening, he thrust one paw in deeply and brought it back dripping with 61yellow liquid and dotted with black bees. Bees and all went into his eager mouth, and he crunched joyously handful after handful. Once a bee tried to come too near, and with one sticky sweep of his honeyed paw he imprisoned the insect, whose wings stuck so fast he could only buzz helplessly, traveling back and forth from the place where the bees wanted the honey to the place where Twinkly Eyes wanted to have it.

Thus, in time, the treasure of the pine tree disappeared,—and my, you should have seen how that little bear’s sides stuck out! It was a lucky thing for him that the honey was all gone, I tell you!

And what a sight he presented, as he slid down the trunk and ambled off to Pollywog Pond! His face by this time was smeared with honey from ear to ear. Flying leaves and little chips of bark clung to it as if they had been pasted there. Add to that his swollen eyelid, which by now had raised a great black welt, and his nose and his mouth all lumpy from the poisonous stings, and one would certainly have said he had been in a fight.

62But he felt so perfectly blissful with his sides rounded out with honey the way they were that he wasn’t the least bit sorry. Not Twinkly Eyes! He would have done the same thing over again the next day had he had the chance.

He knew just what to do with his wounds, and he did it. Searching along the banks until he found some particularly sticky clay, he plastered it freely all over his tortured face until he looked, if possible, worse than before.

But he felt a whole lot better, let me tell you. The wet clay soon began to draw the poison, and besides, bears get over things like that quicker than human beings would. So by the time he had had a nice long snooze and a drink and a stretch, and the round yellow moon began to rise from behind the firs, Twinkly Eyes was ready for almost anything.

Now Twinkly Eyes had a lively bump of curiosity on that furry black head of his. He was much interested in other people’s affairs. And he used to lie hidden by the hour, just to find out what other wood-folk were up to. But of all the dwellers in that wilderness, none interested him so much as the Cottontail family. That is, none except his old enemy the porcupine!

One day, lying under a clump of high-bush blue-berry bushes, in the early spring sunshine, he learned a secret.

“We have a secret at our house! Truly, truly, truly,” sang Betty Bluebird, sitting on a fencepost with her red blouse turned to the warming glow of the early morning sunshine.

“We have too, we have too, we have too!” trilled Robin Red-breast, running along the roadway with a weather eye for worms.

64And down in the marsh behind the barn, Conqueree, the Red Winged Blackbird, was shrilling at the Crows like a little soldier in red epaulettes: “Clear out! Or I’ll put you out! I’m Conqueree! Conqueree! Conqueree!”

“You cawn’t, cawn’t, cawn’t!” the crows retorted, trying to drown out his threats with a hoarse chorus of denial, as they swirled around and around him, keeping just barely out of reach of his swift beak. “We have secrets we won’t tell! Such secrets!—Round, gray green secrets, four to a nest, hidden away up in the tops of the tallest pine trees! And you cawn’t, cawn’t, cawn’t guess what they are!—you cawn’t.”

“Trust a crow to tell all he knows!” chuckled Daddy and Mammy Cottontail, crouched on guard before a small round hole scooped out of the turf and lined with bits of fur from Mammy Cottontail’s breast. “We could tell a pretty cunning secret ourselves, only we have better sense than to shout our affairs to the four winds,” and their slim ears waggled wisely.

65Sure enough, packed snugly back under a blanket of dried grass, six of the softest, roundest little wriggly-nosed babies that ever made a bunny feel like kicking his heels in the moonlight slept with their long ears folded close along their backs and their long hind legs doubled up under their fuzzy brown bodies.

“Do you suppose they’ve all got the same kind of secrets?” whispered Mammy Cottontail delightedly.

“Nothing to compare with ours,” sniffed Daddy, then stopped suddenly, as the little Bear snapped a twig in his effort to creep nearer.

![[Rabbits]](images/i_082.jpg)

Twinkly Eyes had roamed to quite another part of the woods when the twilight stillness was pierced by a sudden screech from up on Mount Olaf.

Mammy Cottontail’s timid heart quailed within her. Mother Red Squirrel could scarce be blamed for all but dropping from her limb; and even Father Red Fox looked anxious at the thought of the red-brown pups in the rocky den on the hill-top.

Far down at the Valley Farm, “Lynx!” whispered the Boy, wide-eyed, “Hope he isn’t coming down to make trouble for our wood folks. He’s mighty fond of baby bunnies.”

Away up almost at the top of Mount Olaf a great cat, three times as heavy as barnyard Tamas, was creeping, creeping, creeping along 67through the underbrush, on great furry feet that made no sound.

His broad ears bore little tufts at their tips, his jowls were squared off with the most ferocious-looking whiskers, and his thick tail was no more than a stub.

“Children,” quavered Mammy Cottontail, “That was a lynx! Now, I want to tell you something, and I want you to listen with all your ears, because it is very, very serious!

“Old man Lynx and his family live up on that mountain top, and while they don’t come down this far once in a coon’s age, we’ve got to be prepared! Because it would be a terrible thing if they did! Terrible for us, and terrible for everyone we know!

“I’ll tell you why he screeched that way! It was to scare timid folks like us, so that we’d jump and betray our whereabouts. Yes’m, that’s exactly what he screeched for! To make us jump!

“Because, you see, when Mother Nature invented little brown bunnies and grouse hens and muskrats and all the rest of us forest folk, she knew exactly what she was about. And she gave us our brown coats so that we’d match the ground, and couldn’t be seen by the big 68prowling creatures that are always trying to have rabbit and grouse for dinner. And just so long as we keep as still as field mice, we stand a fighting chance of not being seen.

“But Old Man Lynx knows this as well as we do. He knows that when he goes hunting o’nights, none but the foolish will be stirring a hair’s breadth from their own warm beds. And if there are no foolish ones that he can sneak up on, with his great padded paws that tip-toe so silently through the underbrush, he screams in the hope that it will startle some of us so dreadfully that we will forget to keep still, and jump.”

“It’s enough to make any one jump out of his skin,” said Daddy.

“But that’s exactly what the Old Man figures on. And if you can’t control your nerves any better than to jump when he screeches, he can see exactly where you are! If he’s anywhere near, that is! Well, you children had better go to sleep now. But just you remember this: Lie still when you hear him scream, and ten to one he’ll never know where you are.”

“Yes, Mammy,” whispered six timid little voices.

It was not often that Old Man Lynx gave voice to the pangs of hunger. For he knew that for every grouse or hare or baby fox he startled into betraying its whereabouts, he scared a dozen so far away that it made hunting harder next time.

But tonight he was teaching some one else the trick.

At the very time that Father Red Fox was viewing his own red-brown pups with such mingled pride and amusement, and Mother Douglas was driving Father Douglas out of the old oak tree, lest he should step on one of the squirrel babies, and Mammy and Daddy Cottontail were taking turn and turn about guarding the six brown bunnies on the edge of the cornfield, Madam Lynx—away up on the top of Mt. Olaf—was just as proud as any 70one of two great, scraggly kittens, as heavy-pawed and bob-tailed and fierce-looking as anything that could be imagined.

At first even these ferocious creatures were as blind and helpless and appealing as any tame kittens could have been, though without their grace. And as soon as they learned the use of their legs, they rolled and tumbled, and growled and spat, and boxed one another about, fully as mischievously as had Fluff, the maltese kitten at the farm, when she and her little brothers lived in the basket behind the kitchen stove.

But Old Man Lynx was kept mighty busy, let me tell you, as soon as they were weaned and could eat meat; for the two youngsters were such ravenous creatures and they grew so fast, and the mountain air was so stimulating, that it just seemed as if he couldn’t bring in enough to keep his share of the larder filled.

So it was by way of teaching young Bob Kitten and his brother how to hunt that old Man Lynx had screamed in such a blood-curdling manner.

71Decidedly Wriggly Nose and Shadow Tail, and even fat young Frisky Fox, were going to have a very much harder time of it making their way in the world, now that there was a new young lynx on the top of Mount Olaf.

Twinkly Eyes was later to share a couple of interesting adventures with young Bobby Lynx.

![[Lynx]](images/i_088.jpg)

Mammy Cottontail, the little brown hare, had been living in the Old Apple Orchard for several weeks now and the bunnies were half-grown.

One moonlight night toward the end of June—the self-same night that Twinkly Eyes had found the bee tree, Mammy said:

“Children, we are going on a frolic tonight. So come along, Flap Ears and Furtive Feet, and Wriggly Nose and Paddy Paws, and Fuzzy Wuzz and Hippity Skip! Daddy’s there waiting for us now!”

Through the moonlight woods she led them in one long line along a little briar-grown rabbit path, the youngsters kicking their heels high in their excitement.

Now they crept under a patch of huckleberry bushes, and now they hugged the shadow of a grapevine. Straight across the 73blueberry burn, they galloped,—under the fruit-laden bushes, then across a corner of wild meadow where the daisies gleamed high above their heads, and all about them was the aroma of sweet fern.

Their path ran zig-zag, this way and that, here circling back upon itself, there darting off at right angles, till anyone trying to follow it would have had an interesting time, to say the least.

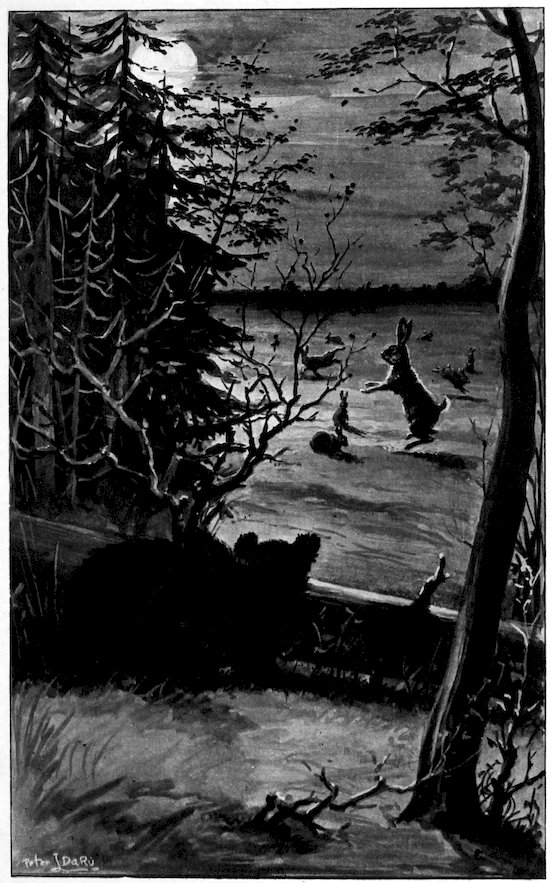

But after various turnings and twistings through the woods, and doublings around the rocky hilltop behind Pollywog Pond, they found themselves away back on the border of a little glade, an opening in the trees where the grass was short and fine like that in a fairy ring. And the moon streamed down, making it all as light as day.

Here on every side were outposts, and the mere crunching of a dead leaf by any creature larger than a rabbit would be the signal for the warning tap-tap of the long hind feet of those on guard.

Within the circle of the moonlit glade a dozen hares were already assembled, and more were coming in from every side.

74Mammy Cottontail drew up in the shadow of a tree trunk, that the youngsters might get their courage up before joining those in the open. Soon there were half a hundred bunnies, young and old, together, scampering about and having a glorious good time. They pranced and they danced and they raced one another. They leapt back and forth across a log and they leap-frogged over one another, kicking their heels to the moon. There was never a sound to break the stillness save the chirping of crickets away back in the meadow they had left.

Then, so suddenly that Mammy’s heart gave an extra beat, there came the warning thump! thump! thump! just behind them!

![[Rabbit]](images/i_091.jpg)

Now Twinkly Eyes, the little Black Bear, had no idea when he awoke of all that was going on so near him.

But ambling down to Pollywog Pond for a drink after his feast of honey, the sound of his crunching over a dead twig was enough to warn the sharp ears that ringed about the rabbit frolic; and from first one outpost and then another came the thump, thump, thump, of a half hundred padded feet on the forest floor.

In an instant every one of the bunnies which a moment before had been capering madly in the moonlight had sought cover.

Mammy Cottontail and her little brood, watching from the shadow of their tree trunk, were already hidden, hearts beating bumpety-bump in their anxiety.

76For perhaps ten minutes they listened, their hearts sounding like trip hammers in the breathing stillness of the forest night, in which no creature larger than an insect moved, save the silent-winged bats and owls.

At least, that was what the listening bunnies thought! But Twinkly Eyes, the sly one!—had heard the thump, thump of the outposts; and he knew just what it meant. Although his little sides were already rounded from his feast of honey, a bear is always hungry. And Twinkly Eyes decided to attend the frolic.

If Mammy Cottontail, anxious little mother that she was, had known all that was being plotted in the head of the little Bear, she would have started her brood for home on the fastest gallop.

But Twinkly Eyes, for all his weight, had paws padded so softly that he can, when he wants to, steal through the underbrush without a sound to warn his quarry of his coming.

Yes, sir, that little rascal can slip through the woods as still as a mouse, and you could sit straining your ears but you would never hear so much as the crunching of a leaf beneath 77his foot. When he really wants to, he can move like a shadow.

Now he had decided to attend the frolic, but not to join in the play! Mammy Cottontail, never dreaming of the sleek black form that crept so silently to the edge of the clearing, led her six out among the merry-makers. Soon Wriggly Nose and Paddy Paws, and Flap Ears and Furtive Feet, and Fuzzy Wuzz and Hippity Skip were leaping and dancing as gaily as the best of them.

The full moon, shining down on the little glade, showed their furry forms so plainly that even Twinkly with his near-sighted little eyes, could see them kick their heels in air.

Crouched in the shadow of the very log where a little while before Mammy and her six had hidden, he watched and waited.

![[Rabbits]](images/i_094.jpg)

Twinkly Eyes had his mind all made up, as he hid there in the shadow of the tree trunk, to add a rabbit to his feast of honey.

He therefore crouched with his great steel paw ready to give the one crushing blow that would be necessary the moment the first brown bunny was so foolish as to pass within his reach.

He watched gleefully as he saw their sleek brown forms dancing so care-free in the moonlight. “Hippity skip and away we go!” their soft feet seemed to sing, as they galloped back and forth across a fallen log.

Saucy fellows, he told himself, as they flapped their long brown ears or leaped high in the air.

“Leaping high in the moonlight”

—Page 79

Oddly enough, so silently had the little Bear approached that not one of the outposts 79was aware of his presence. The wind was blowing directly toward him, so that they did not even get his scent.

Only Mammy Cottontail, prancing gaily around to the right, thought for just an instant that she had caught an alien odor. Leaping high in the moonlight, she struck her long hind feet three times upon the ground, to see if she could startle whatever it was into betraying its whereabouts.

At her danger signal, every bunny in the glade stopped stone still to stare and listen; but Twinkly Eyes was not to be thus betrayed. He was too big to be startled by her stamping, and too wise to come out into the open, where every rabbit, once warned, could easily outrun him.

Not he! Twinkly Eyes just bided his time, huddled down as still as any frightened field mouse. He sat so long in one position that his legs got cramped and he began to feel distinctly drowsy. Why on earth didn’t one of those fat bunnies come just a wee bit closer? How weird they looked, now chasing one another, now pausing to nibble a few grasses, but always well within the open glade where the 80moon would have shown them the first instant an intruder thrust a paw within the charm-ed circle.

After a while, though, the wind died down, and with the bear scent that now suddenly came to the merrymakers, there was a series of frightened squeaks, and in less time than the twinkle of a moonbeam, every last bunny of them had darted under the ferns or into the deep shadows, and the little glade was as empty as if they had never been there.

Then Wriggly Nose, more daring than the others, crept very, very silently toward that dreadful odor. He peered amazed at what he saw.

Twinkly Eyes had fallen fast asleep.

![[Bear & rabbit]](images/i_099.jpg)

Yes, sir, there was Twinkly Eyes, the little Black Bear, fast asleep!

How Wriggly Nose and Paddy Paws and the rest did wiggle their long brown ears at the sight!

“So he had been spying on our frolic!” whispered Flap Ears with a giggle.

“Yes, he thought he’d have hare for supper. Why do you suppose he didn’t catch one of us, when he came so near?” asked Wriggly Nose, his eyes a-twinkle.

“Huh, he knew we could run the faster,” and Paddy Paws threw his chest out.

“He was waiting to knock you down the instant you came near enough,” said Mammy Cottontail, suddenly appearing in the midst of her little brood. “Don’t go too near! He might wake up at any minute!”

82“Aw, come on,” urged Flap Ears to the younger bunnies. “I’ll bet you can’t jump as high as I can,” and he vaulted fully five feet into the air.

“Bravo,” said Mammy Cottontail. “That is as good as I could do myself!”

“I can leap farther,” boasted Wriggly Nose, and shooting like a coiled spring from the ground, he landed a good ten feet away.

“They’ll soon be able to take care of themselves,” chuckled Daddy Cottontail, hopping over beside Mammy at this moment. “We must have more of these drills.”

“Yes,” whispered Mammy, “but don’t let ’em know it’s a part of their schooling. Let ’em think it’s only play, or they won’t take any pleasure in it.”

“Right!” agreed Daddy Cottontail. “The great secret of training the young is to make it play for them. Now when I was a youngster—”

He stopped to prick up his ears.

“What is it?” whispered Mammy, with an anxious eye on the little bunnies, who were now playing leap-frog with the hares from the other side of Pollywog Pond.

83“Didn’t you get a sniff of something, just then, when the wind changed?” asked Daddy. “I could have sworn—there! A fox! A fox!” he signaled with that tap—tap—tap of his long hind legs that sounded so much like drumming on a hollow log.

Instantly every bunny in the glade had dashed to cover, and gone scuttling for home along the crookedest little rabbit road it could find.

For a Fox has sharper eyes than a bear, a keener nose and better ears, and on top of everything else, he can run as fast as the fastest hare that ever grew. At least, a large fox could, and even young Frisky Fox had grown into a foe worth keeping at a distance.

For the taint on the wind was that of Frisky Fox, out on a little spree of his own.

![[Fox]](images/i_102.jpg)

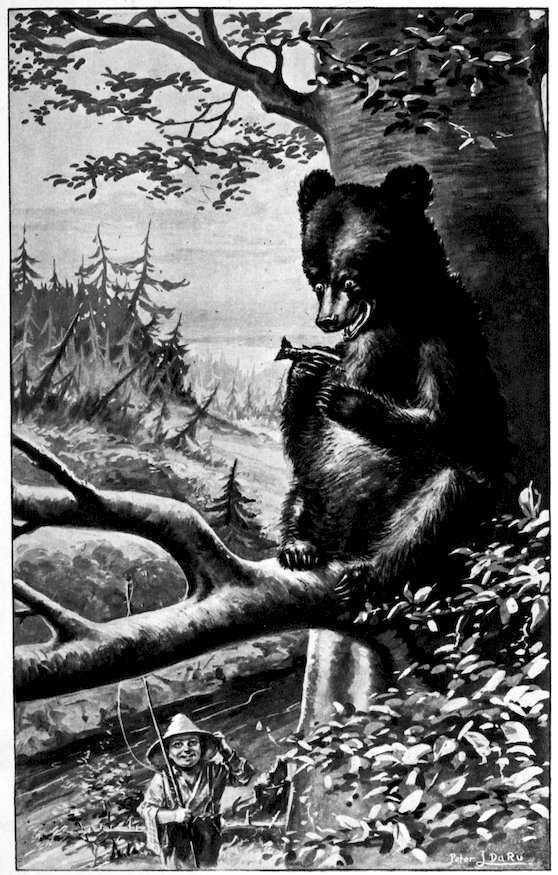

Human ears are never so sharp as those of the wood folk who have to live by their wits. So when the Boy from the Valley Farm heard nothing, and saw nothing, he concluded there was nothing there.

But Twinkly Eyes, the little Black Bear, was following him none the less, half fearful and half curious to see what this two-legged creature might be up to in his woods.

It was a pleasant afternoon, with just enough of a haze to subdue the sunlight. The rain had left the earth fresh and green in the open patches, and the air was sweet with the perfume of Steeple Bush and Joe Pye Weed and pink Sweet Clover. From away down by the meadow back of the Farm came the tinkle of a cowbell, the only sound to break the stillness, save the faint lapping of the river against a boulder.

85The Boy stopped beside a pool half-shadowed by an overhanging log. His sharp eyes could just make out a big fat trout that lay headed up-stream, lazily fanning the water with his fins, to keep himself in position.

Now Twinkly Eyes, who had concealed himself in a clump of bushes a little downstream, began to see the meaning of the long black pole with the line dangling from the end of it.

First the Boy took a tin can from his pocket, a can with holes punched in the top. Selecting a fat white angle worm, of a sort that the little Black Bear well knew grew in the wet places, he fastened it on his hook and dangled it before the trout. But to no avail! That canny fellow knew perfectly that no such worms of soft fat whiteness were ever found in his stream. The kind of worms he sometimes found when there was a cave-in from the bank were strong, slim black ones.—He refused even to nibble.

The Boy next tried a cricket, then a grasshopper, and finally a fat white grub—but with the same result. Then, quite by chance, he chose a black worm.

86But before he cast it, he saw a shining green turtle about as big around as a good-sized crab-apple floating about, just a little upstream. And carefully laying his pole along the bank, he made a grab for the fellow. That roiled the water, and although he didn’t get the turtle, it was one of the luckiest things he could have done. For when he cast his worm into the pool again, the water was so muddy that the old trout thought, of course, the bank had caved in above there, and he made for that black bank-worm as if he had fasted for a week.

A tweak at the line, and the boy was so excited that he swung his fish fully two rods through the air, landing him in the very bush behind which Twinkly Eyes was hiding!

The little Black Bear gave a start of surprise, and for just one instant his head was exposed to the boy’s startled gaze.

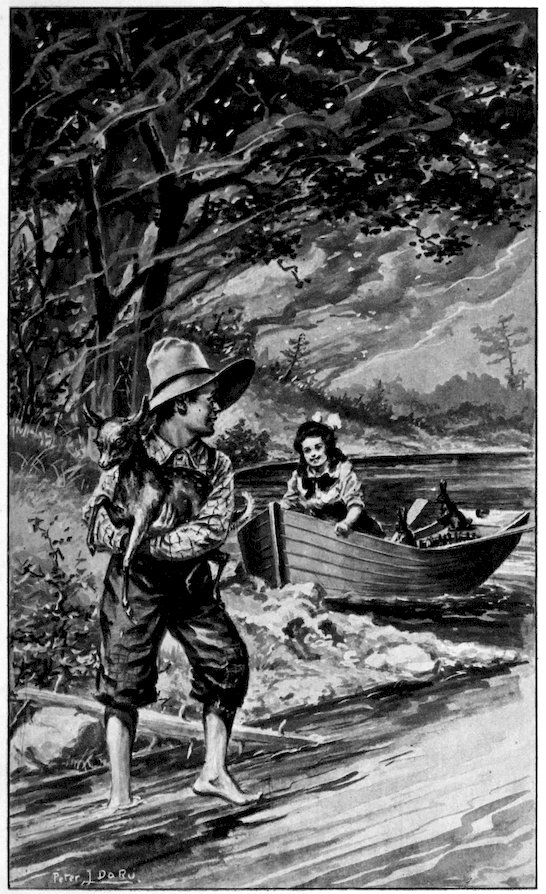

![[Fishing]](images/i_105.jpg)

The Boy from the Valley Farm held his head high with pride.

For had he not—on the self-same day—landed a big fat trout and seen a bear cub!

That would certainly be something to tell at home, even for a backwoods boy! His mouth watered as he thought of the way his mother would broil his fish.

But alas, for the best laid plans of mice and men! When he found the place where he had landed his catch, there was no fish there. Could it be that he had only dreamed he caught it? But no, here was its tail on the trampled ground. Someone had stolen it. But who? That was the question!

Why, of course, the little Black Bear whom he had startled out of the underbrush!

“The rascal!” exclaimed the Boy, half amused, half crest-fallen. Well, I only hope he needed it more than I did.

88“Now I suppose they will never believe me at home when I tell of my big catch.” He started whistling ruefully, as he set about mending his broken horsehair line, which had got badly tangled in the bushes.

Then his eye fell on something that made him pause, wide-eyed. Being a backwoods boy, he was almost as keen at reading the signs about him as were the wood folk themselves—that is, so far as he was able! Of course his nose and ears were very much less sharp than theirs, but he had even better eyes than most of them.

Here was evidence his eyes could not deny, though he reached out and felt of it to be sure. One fin of his stolen trout lay caught in the very top of a hazel bush.

“Now, how on earth did that get there?” he asked himself. People who are much alone are very apt to talk to themselves. “If that cub ate the fish down here, where the ground is trampled, how did he come to drop the fin in a bush higher than his head?”

“Oh you rascal!” shouted the boy, in delight