Title: Wrecked among cannibals in the Fijis

A narrative of shipwreck & adventure in the South Seas

Author: William Endicott

Commentator: Lawrence W. Jenkins

Release date: September 13, 2025 [eBook #76873]

Language: English

Original publication: Salem: Maine Research Society, 1923

Credits: Terry Jeffress and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

From a water-color painted at Marseilles in 1823 by Anton Roux, Jr.

[1]

A NARRATIVE OF

SHIPWRECK & ADVENTURE

IN THE SOUTH SEAS

BY

WILLIAM ENDICOTT

Third Mate of the Ship Glide

with Notes by

LAWRENCE WATERS JENKINS

Assistant-Director of the Peabody Museum

of Salem

MARINE RESEARCH SOCIETY

SALEM, MASSACHUSETTS

1923

[2]

PUBLICATION NUMBER THREE

OF THE

MARINE RESEARCH SOCIETY

SALEM, MASS.

COPYRIGHT, 1923, BY

THE MARINE RESEARCH SOCIETY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES

THE SOUTHWORTH PRESS

PORTLAND, MAINE

[3]

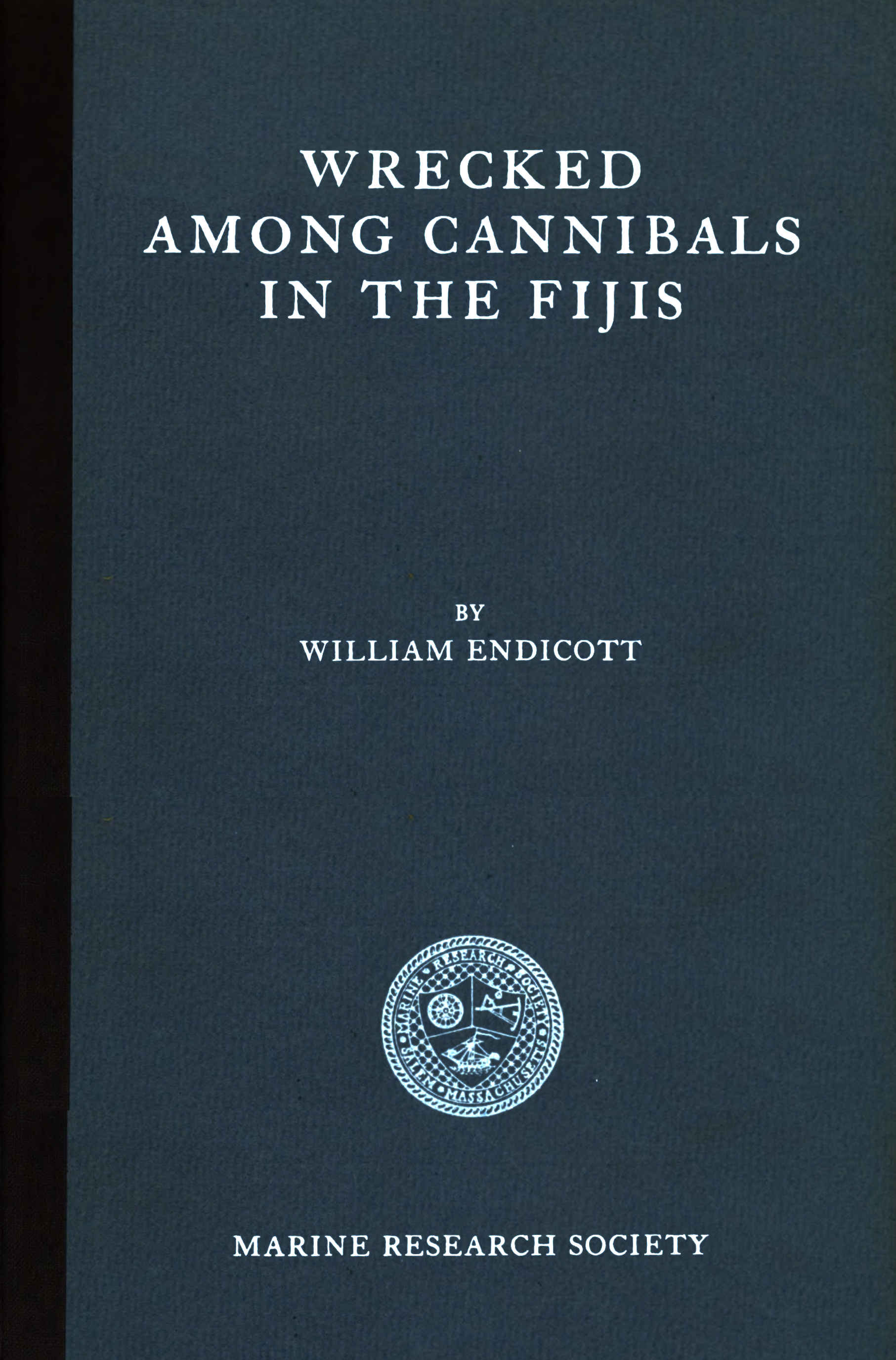

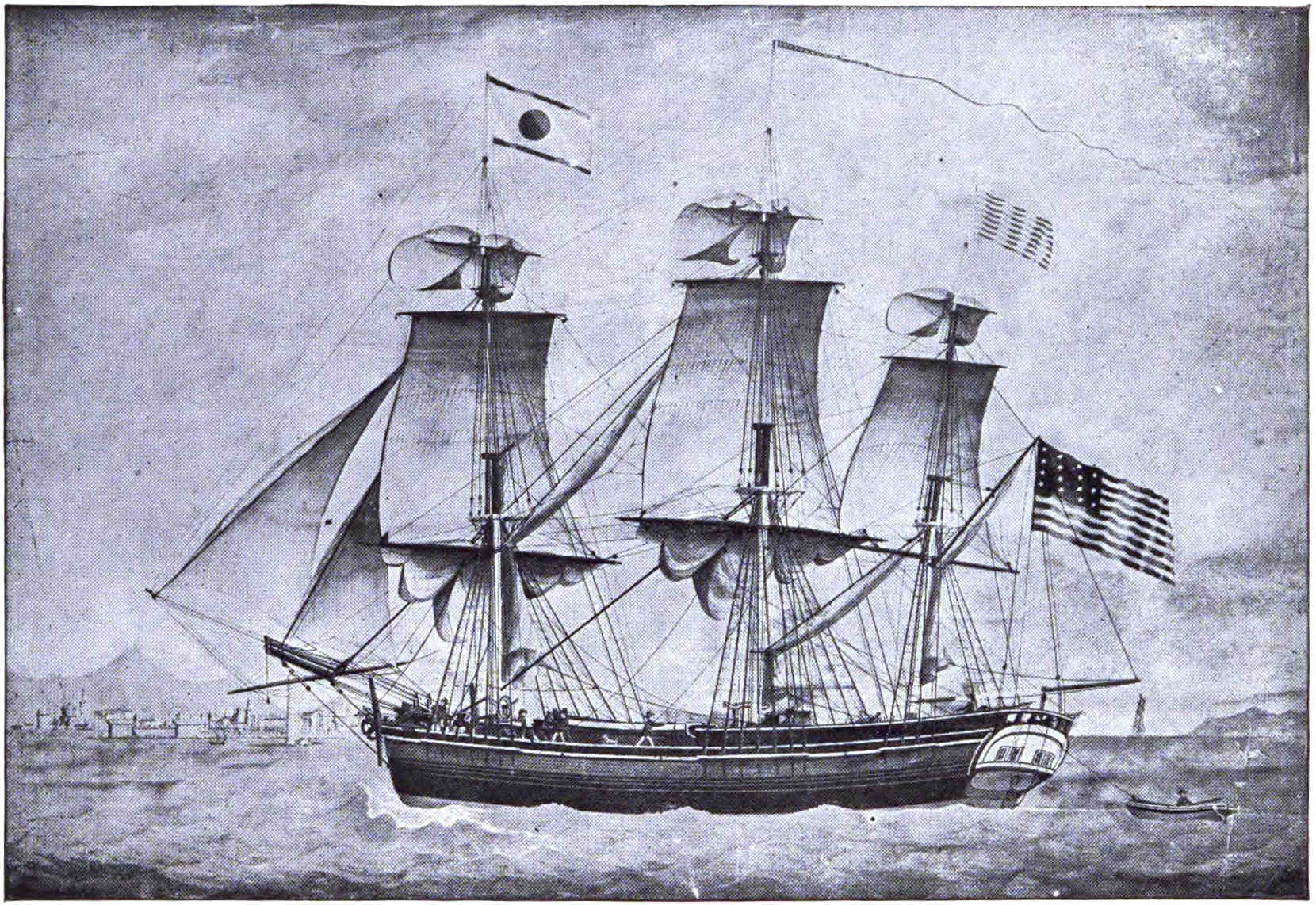

| Ship Glide of Salem Frontispiece | |

|

From a water-color painted at Marseilles in 1823 by Anton Roux, Jr. |

|

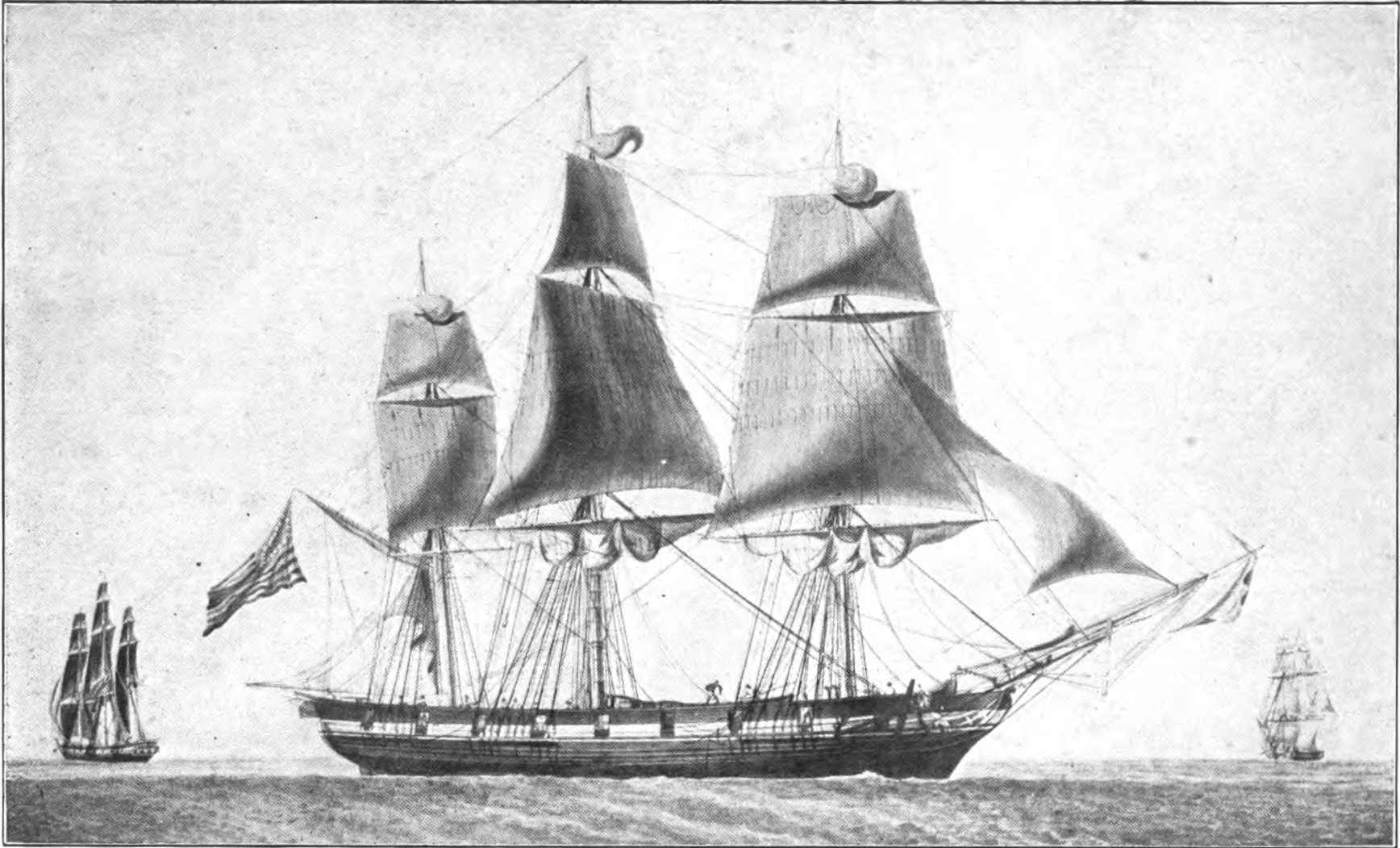

| William Endicott | 15 |

|

From a photograph made about 1860. |

|

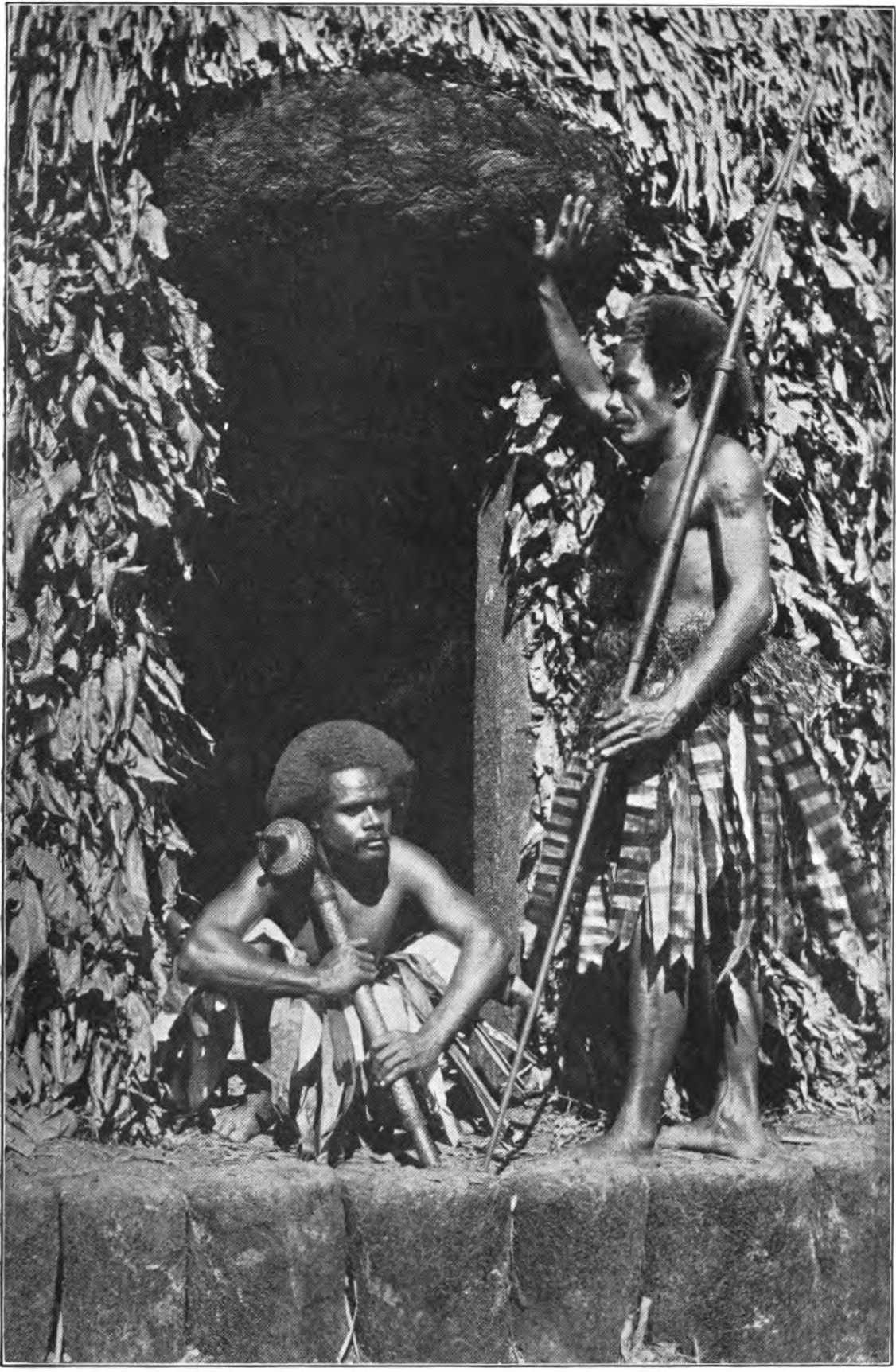

| Fijian Men | 20 |

|

From a photograph made in 1898. |

|

| Ship Ann Alexander of New Bedford | 29 |

|

From a water-color in the possession of the Old Dartmouth Historical Society, New Bedford. |

|

| Fiji War Clubs | 34 |

|

Presented to the East India Marine Society of Salem between 1823 and 1834. Now in the Peabody Museum of Salem. |

|

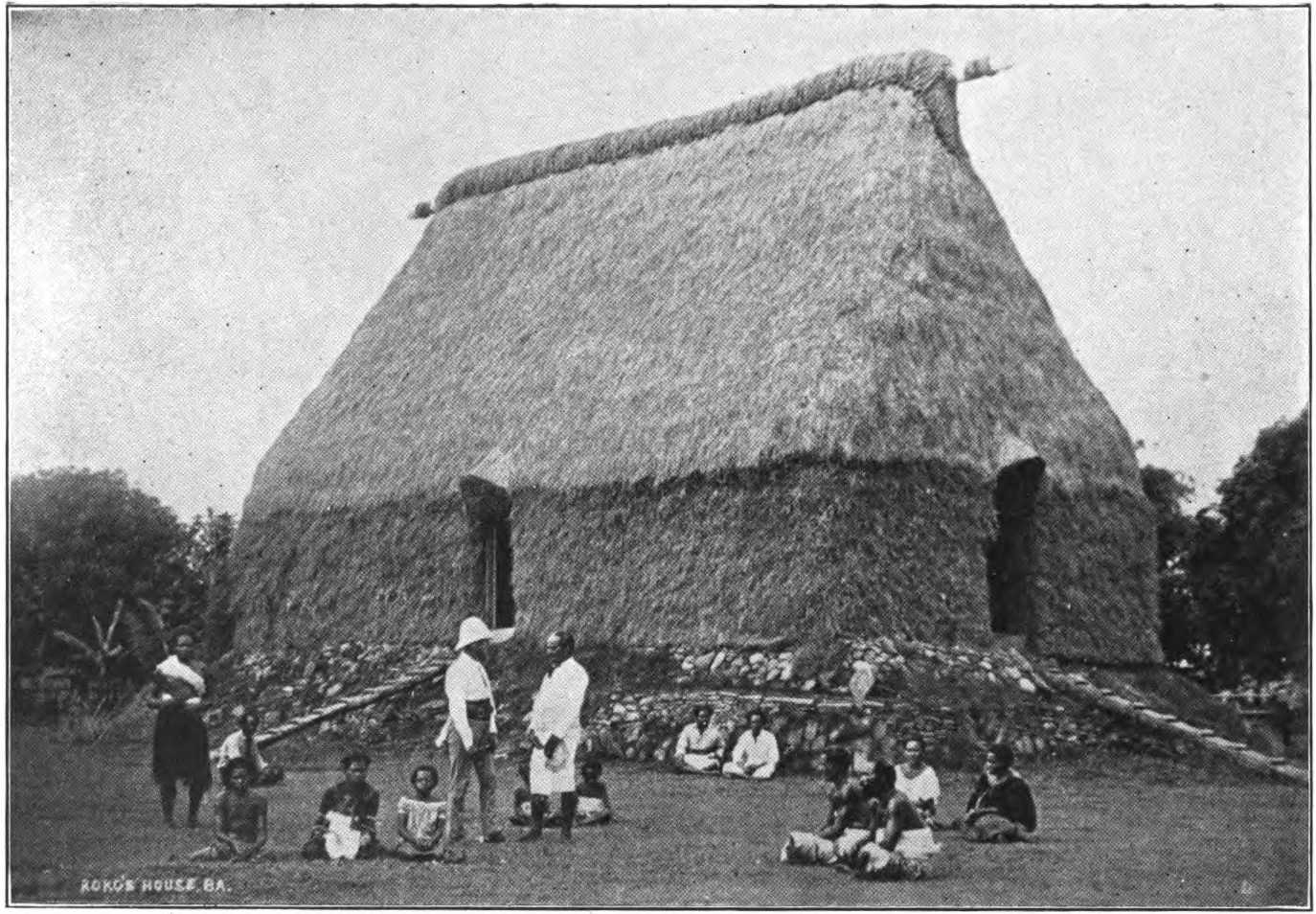

| Fijian House | 40 |

|

From a photograph made in 1898. |

|

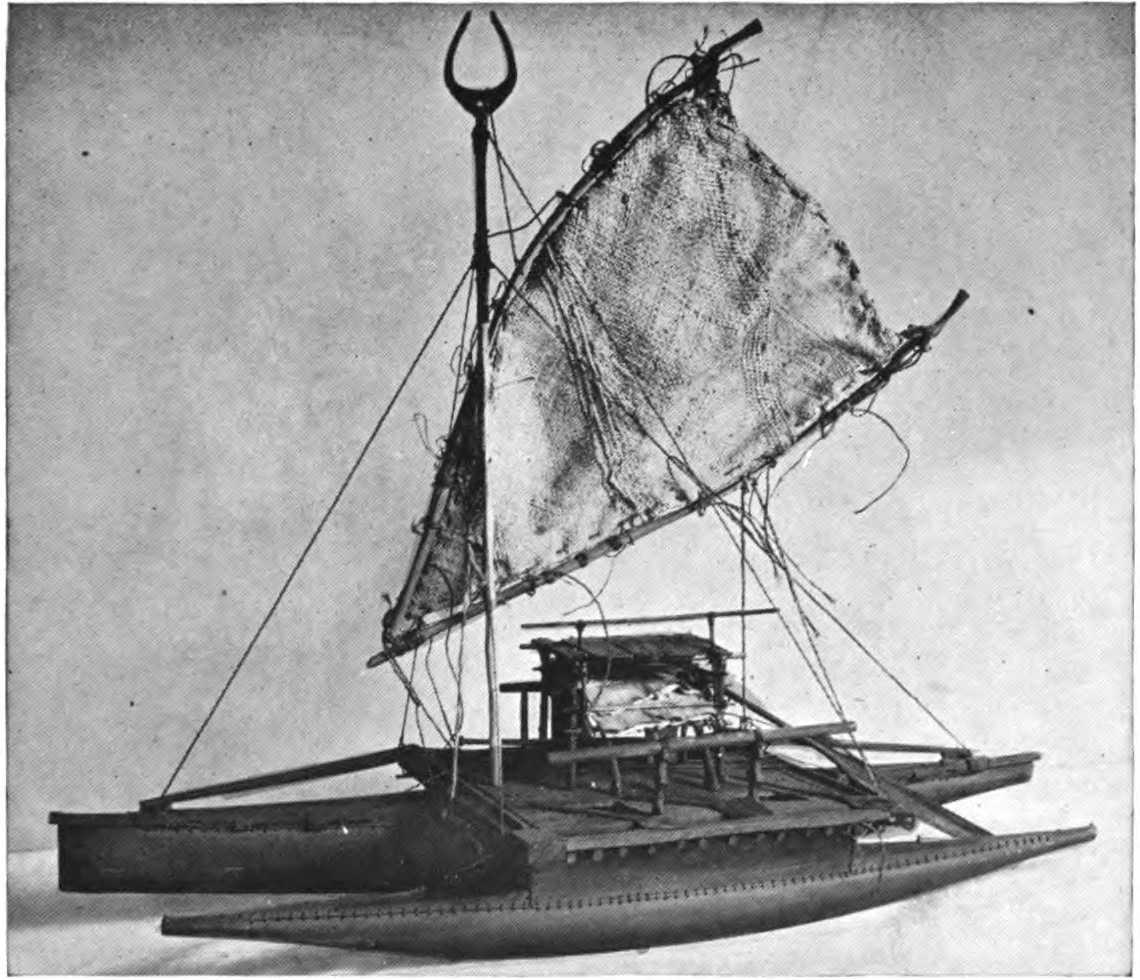

| Model of a Fiji Double Canoe | 44 |

|

Brought to the United States in 1856 by Capt. Thomas C. Dunn, while on the bark Dragon of Salem. Now in the Peabody Museum of Salem. |

|

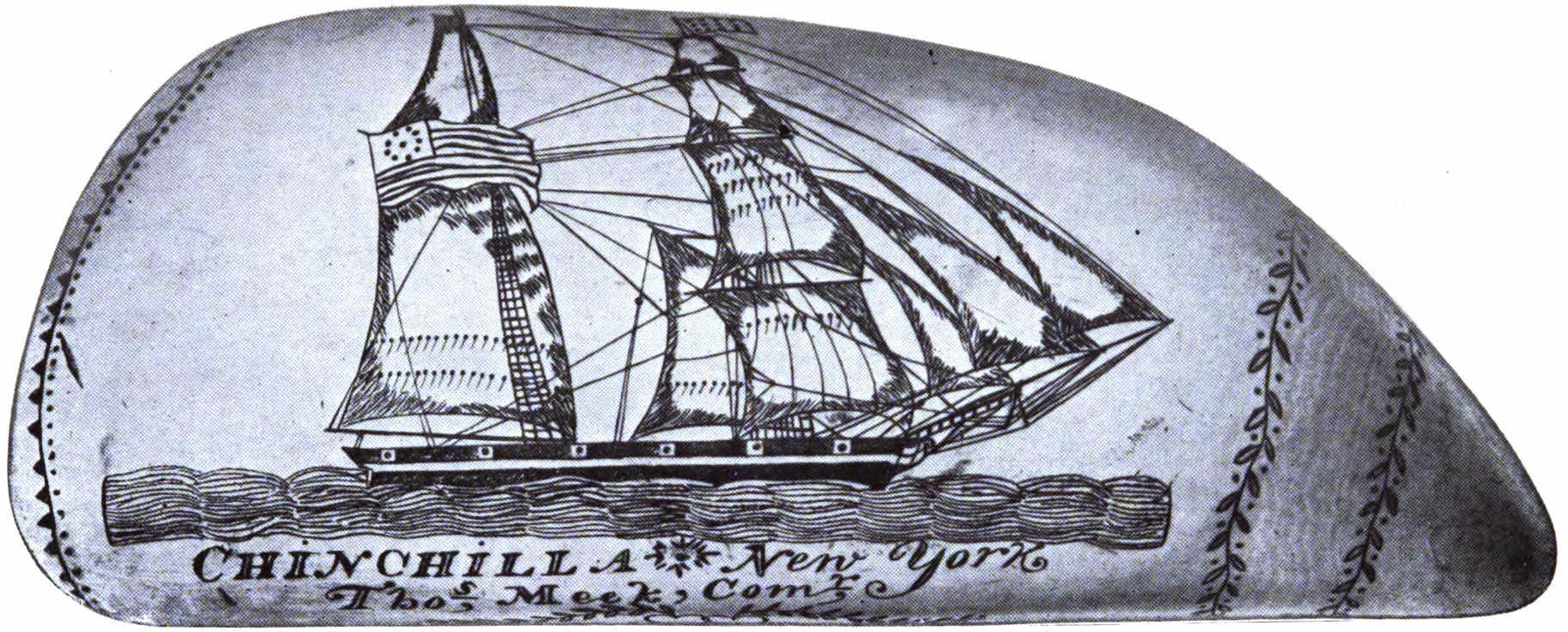

| Ship Chinchilla of New York | 50 |

|

“Scrimshawed” on a whale’s tooth. Presented to the East India Marine Society of Salem in 1825, by Capt. William Osgood. Now in the Peabody Museum of Salem. |

|

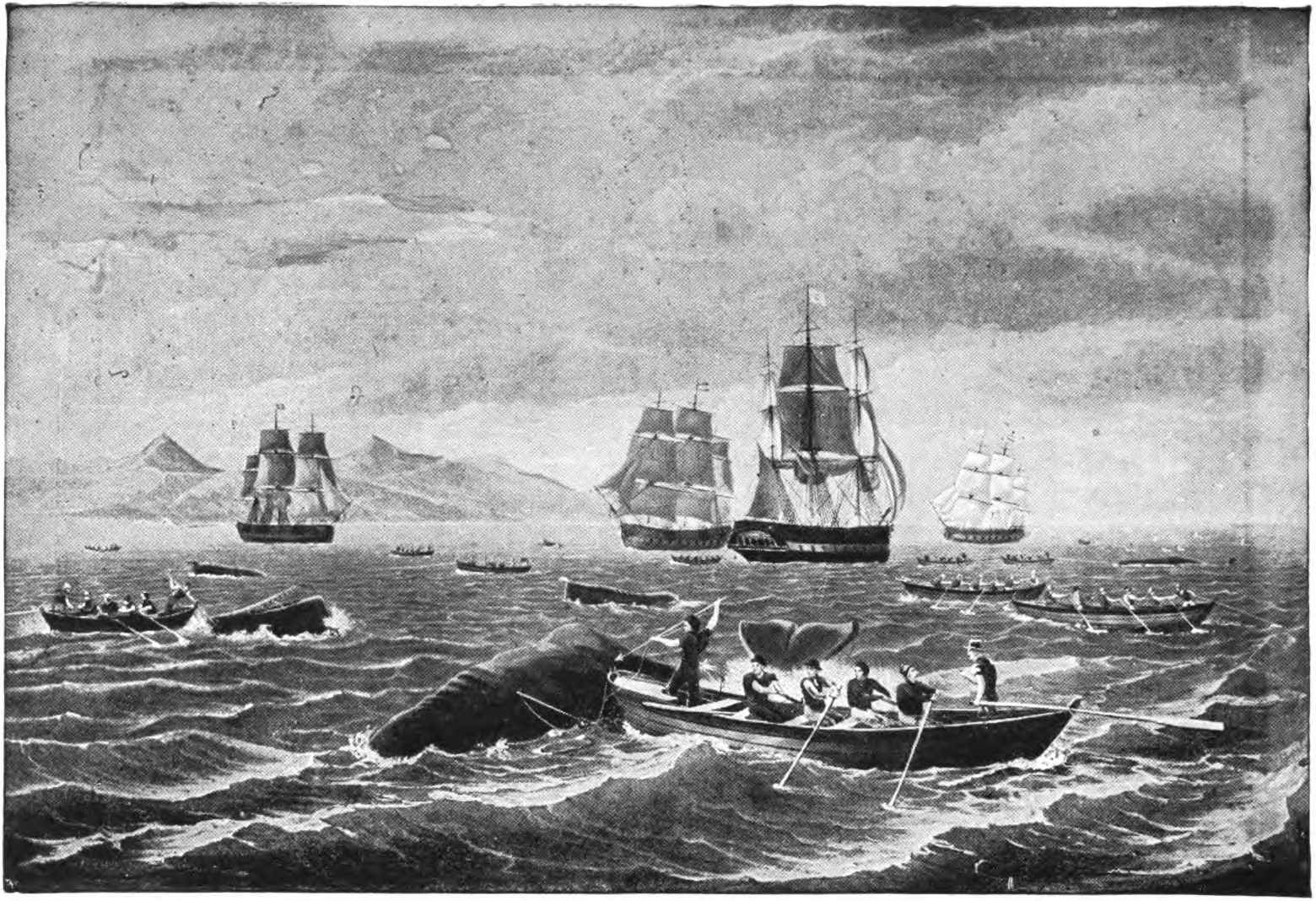

[6] A Shoal of Sperm Whale off the Island of Hawaii in 1833 |

52 |

|

From an engraving by J. Hill after a painting by T. Birch. The picture shows the famous Roach (Rotch) whaling fleet,—the Enterprise, Wm. Roach, Pocahontas and Houqua, all from Nantucket. |

|

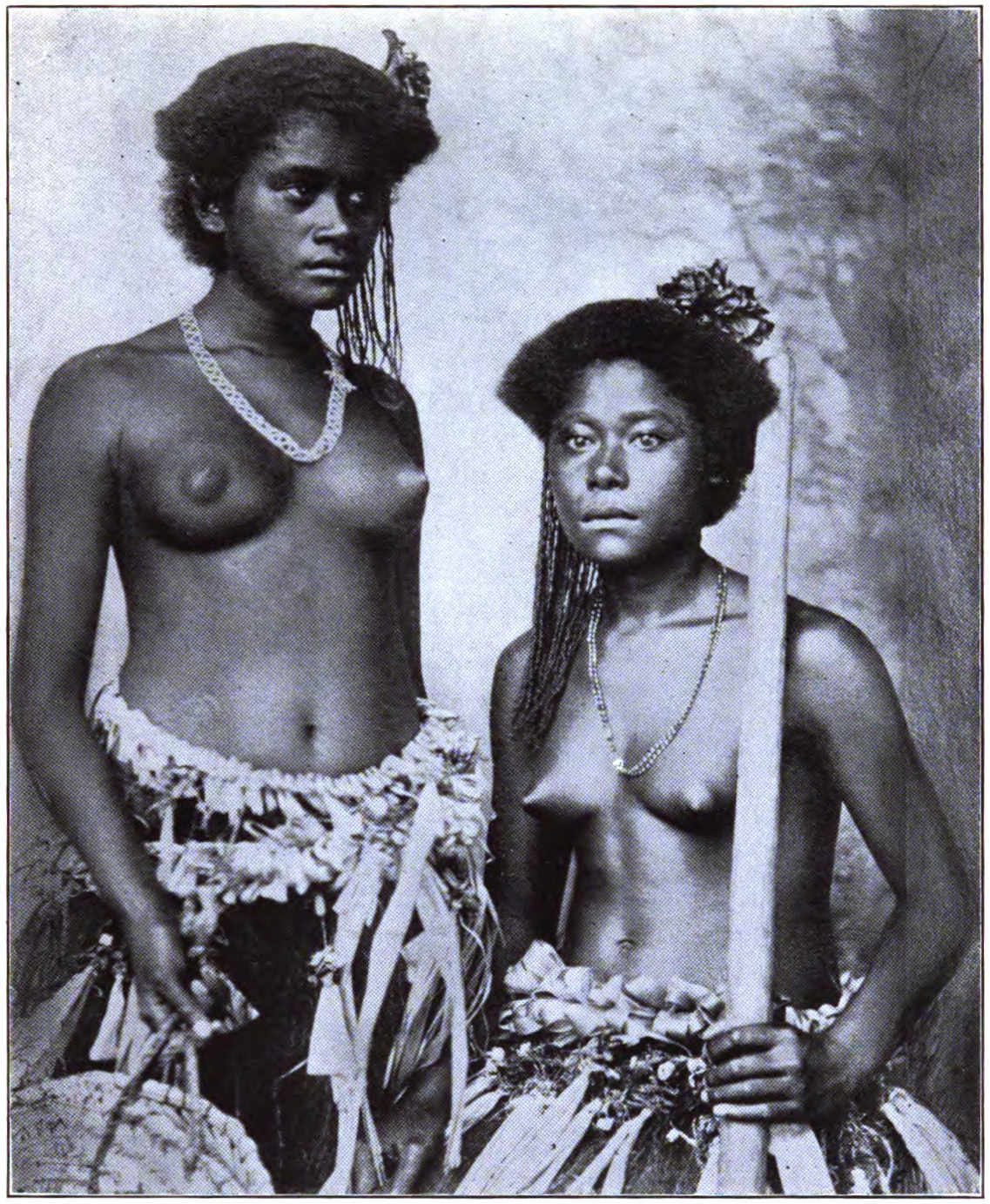

| Fijian Women | 56 |

|

Wearing “maiden locks” indicating that they are unmarried. |

|

| Tooth of a Fijian Cannibal | 66 |

|

Presented to the Essex Institute in 1851 by Capt. John H. Eagleston who stated that it was “A tooth from Na Massa Ngaloa, the greatest cannibal that ever lived, head chief of Rewa, Fiji Islands. Twenty years since conquered most of the islands in the archipelago; since died aged about sixty years. Eleven years ago became Christian—baptised Ratu Mill.” Now in the Peabody Museum of Salem. |

|

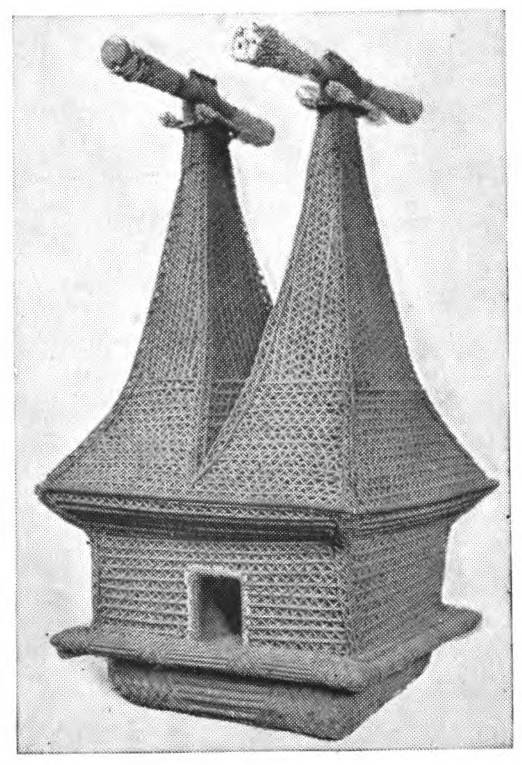

| Model of a Bure or Fiji Temple | 66 |

|

Such models were presented to the temples as offerings. Given to the East India Marine Society of Salem, by Capt. Joseph Winn, Jr., in 1835. Now in the Peabody Museum of Salem. |

|

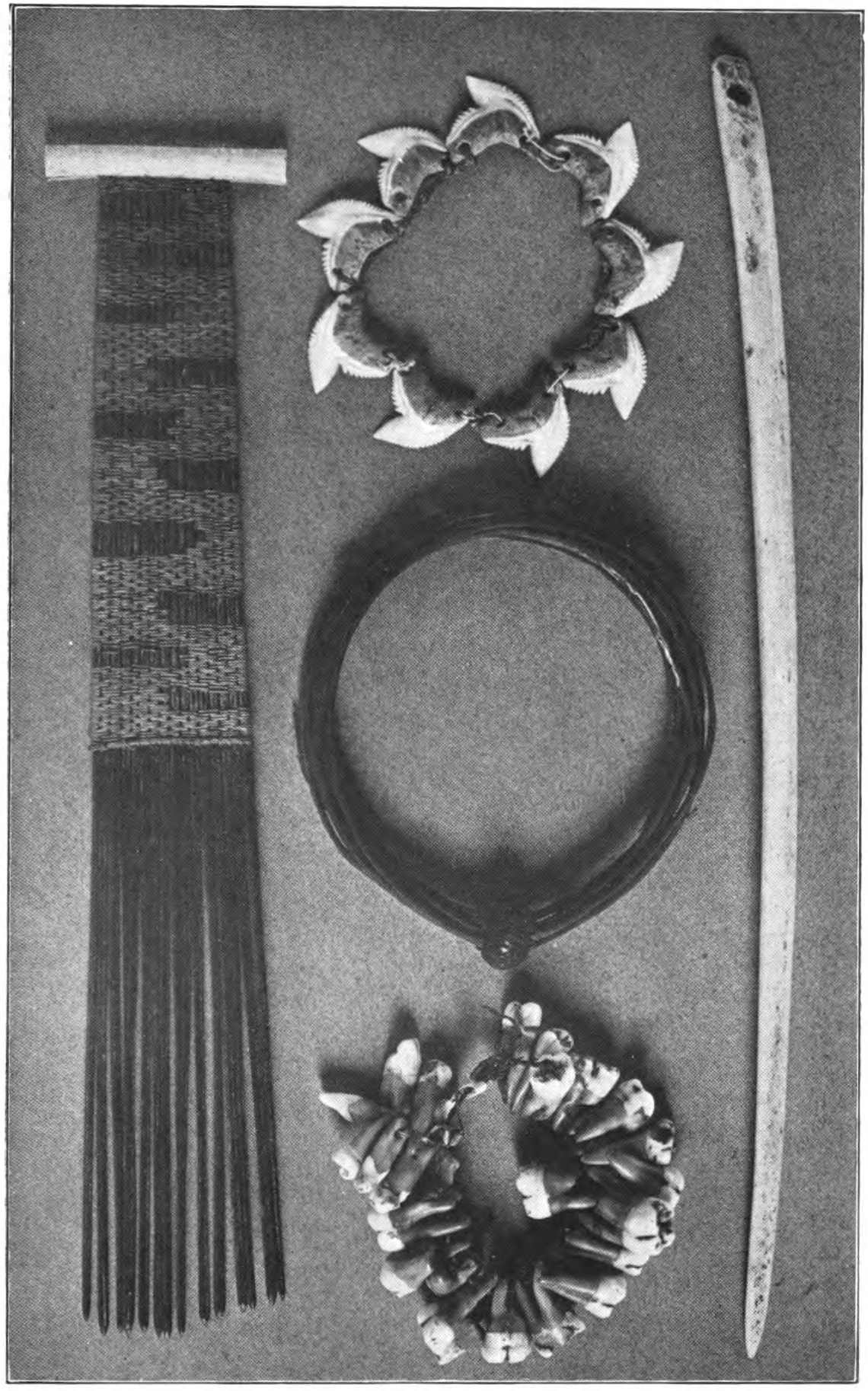

| Objects from Fiji | 68 |

|

Presented to the East India Marine Society of Salem and The Essex Institute between 1831 and 1860. Now in the Peabody Museum of Salem. |

|

[7]

A hundred years ago the young men and boys living in New England seacoast towns could easily find in the forecastles of locally built ships, an opportunity to gratify a desire for adventure and a sight of foreign lands. Many of their shipmates would be neighbors or come from nearby towns and all who intended to follow the sea looked forward with anticipation and pride to the day when they might be able to ship as an officer or be given the command of a vessel. It was no unusual thing at that time for officers and captains to be under twenty years of age and the ship and the sea then possessed a romance and a lure not to be found in the present-day age of steam. The following narrative describes in matter-of-fact language, the experiences of one of these twenty-year old lads who shipped out of Salem, Massachusetts, as third officer in a fine ship bound for the South Seas.

The ship Glide, of 306 tons burden, was built in Salem in 1811 for Joseph Peabody and Samuel Tucker and made thirteen voyages to the Mediterranean, Archangel, South America, India and the East Indies. In 1829 she was sent on a trading voyage to the South Seas under the command of Capt. Henry Archer. Most of her crew were young men and some were green hands. After doubling the Cape of Good Hope a course was set for New Zealand where fresh provisions, wood and water were taken aboard. At that time it was possible to obtain [8] for a small piece of tobacco or some trading article of trifling cost, finely carved and ornamented war-spears and canoe paddles and curiously figured shawls made from the native flax,—articles now highly valued by museums and collectors. While there the ship was visited by Pomare, the principal chief in that part of the island, who brought with him his favorite wife. He was a fine-looking man wearing a blanket fastened over his right shoulder and his face and thighs were tattooed in graceful scrolls. She was handsome for a New Zealander, wore a blanket fastened over her left shoulder and her lips and chin were tattooed.

After a voyage of 142 days from Salem, the Glide reached Narai, one of the Fijis, where fresh provisions were taken aboard. A common musket worth only two or three dollars could be traded for a dozen large hogs and a pair of scissors or a jackknife was valued at a bunch of plantains or forty cocoanuts. When it came to exchanging trading goods for the native labor necessary to obtain the beche-le-mer—the principal article of trade in the islands—a common chisel made by the blacksmith on board from old hoop iron could be bartered for a day’s labor. To earn a chisel the islander must leave his hut early in the morning, sail fifteen or twenty miles to the reef and then work knee-deep in the water for six or eight hours gathering the beche-le-mer, a species of sea snail; after which he must carry his spoil to the ship—and all for a barrel-hoop chisel! The trading goods most esteemed [9] in the Fijis at that time were iron tools, knives, scissors, whale’s teeth, beads and trinkets, but especially muskets, pistols and ammunition.

The place selected for trade was reached about the middle of October, 1829, and after negotiating with the local chief, his people were employed in building three houses,—a “batter house,” a hundred feet long, thirty wide and twenty high, where the beche-le-mer were dried and cured after boiling; a “pot house,” open on all sides, in which the forty-gallon pots were placed to boil the sea snails; and a “trade house,” a building about fifteen feet long, ten wide and eight high, in which trading goods brought in the ship were stored and so made easily available for barter.

The beche-le-mer when found on the reefs are about eight inches long and three inches thick. They are of a dark brown color, have a rough skin which is thickly covered with slime, and are easily taken. Exposure to the air has little effect upon them. After having been purchased by the trading master they are placed in a shallow pool made near the shore where the sea-water flows in at high tide and here the snails are cleaned of slime and then taken to the pot house and boiled about forty minutes. After drying they become hard and are then sent aboard the ship, packed in matting bags and stowed away. When properly cured beche-le-mer will remain in good condition for several years. It requires the Chinese palate to wholly appreciate the peculiar delicacy of its flavor when cooked and served as a [10] table dainty and it was to the Chinese market in Manilla that the Glide’s cargo was taken and sold.

As the natives were a warlike race and the different tribes were constantly engaged in fighting, the dozen men who remained on shore in charge of the trading house and the curing of the beche-le-mer, went fully armed. The Glide, also, presented a warlike appearance. Heavy cannon loaded with cannister and grape-shot appeared at every port-hole and on deck and below weapons were placed so that they were available at an instant’s notice. In each top there was a chest of arms and ammunition and “boarding nettings, eight or ten feet wide, were triced up around the ship by tackles and shipping lines suspended from the extremities of the lower yardarms.”[1] This seemed very necessary as nearly two thousand natives were employed in gathering and curing the beche-le-mer to complete the cargoes of the Glide and the Quill, a brig hailing from Salem, that came in not long after the Glide reached Miambooa Bay.

Severe storms at times prevail in the Fijis and twice the Glide narrowly escaped shipwreck. On the evening of March 21, 1831, a hard gale came up unexpectedly and all night the shrill voice of the leadsman called at intervals, “She drags! She drags!” The next morning at about eleven o’clock, after having dragged her anchors for a distance of nearly eight miles, the ship drove on a shore-reef projecting from the island of Vanua Levu and soon became [11] a total wreck. In the following pages, William Endicott, the third officer of the Glide, describes the events of the voyage and gives an interesting account of the natives among whom he lived for several months; supplying also a short vocabulary of their language.

William Endicott, who wrote this narrative, was the son of Israel and Betsey (Rea) Endicott of Danvers, Mass., and was born there July 7, 1809. He came of a family of sailors and shipmasters and at the age of fifteen went to sea for a voyage to the west coast of South America, in the ship China, Capt. Hiram Putnam. There the ship was loaded with copper and the voyage home made by way of Manilla, China and Calcutta. It was during the homeward passage through the South Seas that Endicott learned of the trade in beche-le-mer. The first officer of the ship was Henry Archer, Jr., a Salem man, and on reaching home he proposed to Joseph Peabody, the great Salem shipowner and merchant, that a voyage be made to the South Seas to obtain beche-le-mer to be traded for Chinese goods. The venture promised large profits and Archer was given command of the ship Glide and he shipped young Endicott as his third mate. This was Endicott’s last voyage to sea and on reaching home he engaged in the morocco leather business and in 1861 was commissioned an inspector in the Salem Custom House. He died Sept. 25, 1881, in Danvers.

The journal of the voyage to the Fijis, kept by him, was given to the Peabody Museum of Salem [12] by his children and is now printed for the first time by the kind permission of the Museum authorities who have also supplied valuable material to illustrate the volume. Accompanying the journal was a log book, kept during the voyage, from which additional information has been abstracted and is included among the footnotes. Mr. Israel O. Endicott, a son of William Endicott, has obligingly furnished biographical information. Thanks are also due to Mr. Charles C. Willoughby, Director of the Peabody Museum of Archæology and Ethnology, Cambridge, Mr. Perry Walton, Boston, The Essex Institute and Mr. Henry W. Wright, Salem, for assistance in illustrating the book.

[1] See Wreck of the Glide, Boston, 1846.

[13]

From a photograph made about 1860.

[15]

WILLIAM ENDICOTT’S NARRATIVE

On May 21st, 1829, I went on board the ship Glide, then lying in Salem harbour, having engaged to perform a voyage in her to the South Pacific Ocean for the purpose of procuring a cargo of beche-le-mer, tortoise shell and sandalwood. At meridian, all hands being on board, we got underweigh with a moderate east wind, and stood out to sea with all sail set. At 5 P. M. we were obliged to anchor outside the harbour where we lay until the following day at 11 A. M. when we weighed again and succeeded in getting to sea. We shaped our course for the Cape de Verde Islands in order to be sufficiently to the eastward where we expected to meet the South East trades, and soon lost sight of the American shores.

Nothing of importance occurred on the passage till the 15th of June, when we saw one of the Cape de Verdes. We passed it and steered to the southward till the 1st of July when we first met the South East trade wind. We continued to steer to the southward, by the wind, until we reached the latitude of 32° south, when the wind becoming more variable, enabled us to proceed more directly on our course; to double the Cape of Good Hope, proceed to the eastward and touch at New Zealand, as was determined by the Captain, and to endeavour to procure some fresh stock. After arriving into the latitude of 40° south, we experienced a succession of gales and blowing weather, which lasted with but [16] little cessation until the 31st of August, when we saw Van Diemens Land,[2] from whence we steered direct for the northern part of New Zealand.

The wind and weather proved favourable and on the 14th of Sept. we saw the island of New Zealand and on the 17th anchored in the Bay of Islands,[3] 117 days from Salem, with one man sick.

We found in this place three English whale ships[4] and one merchant brig.[5] The natives, although engaged in wars and fighting with themselves and being exceedingly fierce and savage, treated us very well and sold us hogs and vegetables in great plenty for muskets, powder, tools, cloth and tobacco. We generally were well pleased with them excepting the strong propensity they had to steal.

The English Mission has a large establishment in this place guarded by a fort, and have succeeded tolerably well in informing the natives and in particular in putting a stop to the horrid practice of eating the dead bodies of their enemies.[6]

[17]

We purchased six of the natives from one of the Chiefs, who we intended to employ in procuring our cargo; and after getting a supply of fresh stock, wood and water, we sailed from this port and steered to the north west intending to touch at the Tonga Islands before we went among the Fegeis, in order to lay in a good supply of vegetables and hogs which are in greater plenty at the Tonga Islands than at New Zealand.

After leaving the land we found the weather boisterous for a few days until we reached the south east trades when it proved mild and pleasant and on the 6th of October, we saw one of the group called Friendly Islands[7] by Capt. Cook and Tonga by the natives. We ran in near to the shore when the natives came off in great numbers in their canoes [18] bringing great quantities of cocoanuts, yams, plantains, hogs and fowls, besides different kinds of fruit, which they readily sold for cloth, beads, etc. As we had plenty of trade which we brought from the United States for the purpose we soon purchased a sufficiency of fresh stock and vegetables.

The natives were of a copper complexion and were of very handsome features and appeared very friendly to us and well pleased with our trade. They were nearly naked having only a small covering over the middle and a few small ornaments round their necks and in the ears.

On the 8th, having purchased a sufficient quantity of stock, we left the Islands and steered for the Fegee Islands,[8] our destined port, where we expected to procure our cargo and where we should be obliged to stop some months.

These are a cluster of islands situated in the Pacific Ocean between the latitudes of 15° and 18° south and the longitudes of 178° and 180° east and [19] very much resemble the West Indies, being very fertile and producing nearly all the fruits and vegetables found at those islands and being situated between the Tropics, the climate is much the same.

Mountains of considerable size are to be found among them though they would be generally considered as low islands. They are surrounded by coral reefs and shoals of sand which renders navigation extremely dangerous though they serve to protect many harbours and bays from the sea. Although situated in the immediate vicinity of the S. E. trade wind, the wind does not prevail at any particular point, but is generally very variable and subject to frequent changes.

These islands are inhabited by a race of people who differ very much from the other uncivilized nations in the South Pacific Ocean, in customs, language and particularly their complexion which is much darker and approaches very near to the Negroes. In stature they are larger than most Europeans and like other Indians are very straight and well built and it is not uncommon to see persons of elegant figure.[9] They are extremely fierce and savage, frequently at war[10] with each other and are addicted to the horrid practice of eating their enemies when killed in battle.[11]

[20]

On the 10th of October, 1829, we arrived among the group and passed Turtle Island,[12] the southernmost of the cluster, steering to the northward intending to anchor in Miamboo Bay, which lay about 100 miles distant, where we expected to commence trading for our cargo. We continued sailing through the passages between the islands (which by reason of the imperfection of our chart, and the islands being improperly surveyed, was rendered extremely dangerous and difficult), until the 18th of the month, when we started from an island (under the lee of which we had to lay by through the night, it being too difficult to proceed till daylight) and steered for the passage through a very large reef of coral.

From a photograph made in 1898.

At 11 A. M. we found our ship safe through the reef but in a very dangerous situation being surrounded [21] by sunken rocks and shoals. We continued sailing for the Bay which was about 40 miles distant, avoiding the rocks as soon as they could be seen, until 1.30 P. M. when a rock was seen directly ahead of the ship. Every effort was made to avoid the danger but it proved of no avail and she immediately struck on her larboard bow about 12 miles from the Bay. We lay’d the sails aback and she went off when we sounded the pumps and found she leak’d 1400 strokes per hour.

After getting clear of the rocks we anchored with the stream and sent the boat well arm’d to examine the Bay. The boat returned in the evening and at daylight we proceeded to get the anchor up but found it impossible without great danger to the ship. Accordingly the cable was cut and at meridian we arrived in Miamboo Bay, Oct. 19th, 1829, Civil Account.[13]

On examining the leak we found the keel split badly and the ship injured so much as it would become necessary to repair her before we could prosecute our voyage, but we found no place where we could heave her down or haul her on shore with safety. Having understood from the natives that there was another vessel at a place 90 miles distant, [22] called Bow,[14] we dispatched a boat to procure assistance and also any information that would be of service to us in our unfortunate situation.

Meanwhile we proceeded to stop the leak, as well as circumstances would permit, until the 20th, when to our great joy we discovered a sail standing for the Bay. At 5 P. M. she anchored and proved to be the brig Quill[15] of Salem, Capt. J. Kinsman, from the Island of Bow. They informed us of the danger of our boat from the natives when another boat was immediately dispatched in charge of the first officer[16] of the Quill, to find the other boat. Oct. 23rd, both boats arrived safe.

Finding it impossible to repair the ship on the shore it was determined to construct a raft from the ship’s spars and the lumber in the ship and to heave the ship down in the Bay, to the raft, Capt. Kinsman [23] kindly offering us his assistance and protection from the natives.

Got underweigh on October 22nd and anchored near to the brig where we commenced transhipping our cargo, stores, provisions, etc., on board of the brig. After this was accomplish’d we proceeded to strip the ship and construct the raft with the spars, etc. We had an interview with the principal Chief of the Island, on Oct. 25th, and purchased some cocoanut trees of him for our raft by means of which, on the 1st of November, we completed it to our satisfaction. After securing and preparing the ship we attempted to heave her down but found no rope in either vessel of sufficient strength. The next day, however, we succeeded in making a rope and hove the ship keel out and found the stem started over to starboard, the wood-ends started considerably, the keel split, etc.

As it was impossible to right the stem in our present circumstances, it was determined to secure it as it was by means of iron clamps, which the armourers of both vessels proceeded to make on board of the brig, and to stop the leak as much as possible with wedges, sheathing and tar.

On Nov. 9th, 1829, we received a visit from Capt. Maurice of the brig Morliana of Woaho,[17] lying about 60 miles distance.

On the 19th of November, after much trouble and after surmounting many difficulties we succeeded in finishing the repairs and when we righted the ship, [24] found we had stopped the leak. We also found that two of our New Zealanders had run away from us and gone to live with the Fegee natives. In the meantime the brig Quill had commenced curing beche-le-mer.

By the 24th we had succeeded in getting all our cargo, provisions, ballast, etc., on board and commenced rigging the ship. The Captain then contracted with one of the principal Chiefs to build three houses on shore for the purpose of curing beche-le-mer at a place called Sub-a-Sub, and on the 9th of December, the first and third officers, with 10 men, went on shore, the houses having been completed, and commenced purchasing beche-le-mer of the natives.

The beche-le-mer[18] is a sort of animal found on the sandy reefs, which very much resembles a leech or blood-sucker in shape, but is much larger. They are supposed to get their sustenance from the slime, which collects on the reefs and shoals so numerous among these islands. The natives obtain them by going onto the reefs when the tide is low, collecting them in baskets made for the purpose from the leaves of the cocoanut tree. They brought them on to the beach near to our house where we purchased them. We then carried the fish into the pot-house and boiled them; then into the drying-house where they were dried by means of fire. When they are considered as cured they are much reduced in size [25] and very hard, but when stowed in the ship they soon become more soft and very much resemble India rubber.

We employed great numbers of the natives, frequently upwards of 80 canoes averaging 10 men each, besides great numbers on shore procuring wood (of which we used great quantities) and assisting us in curing the cargo. The principal articles of trade were muskets, ammunition, whales’ teeth, iron tools, beads and ornaments. Tortoise shell and sandalwood we also purchased of the natives. The turtles they catch with large nets made of the fibres of the cocoanut husk in the making of which they are very expert.

On the 10th of December we got underweigh and ran in towards the shore near to our fish houses and proceeded to finish rigging the ship and repairing damages. After three or four days, finding it difficult to proceed from our unacquaintance with their language, we shipped an interpreter[19] from the brig Quill, also a number of seamen who were acquainted with the method of curing the fish. We also purchased the kettle of Capt. Kinsman (ours being too small to make any progress) and proceeded to purchase the fish of the natives again.

On the 21st the brig Quill sailed for Manilla, having on board about 800 piculs[20] of beche-le-mer, [26] tortoise shell, etc. She returned on the 23rd, in consequence of a head-wind, but sailed again on the first of January.

Jan. 11th, 1830, Seth Richardson died on board the ship. He belonged to Salem and had been complaining nearly all the voyage.

We continued curing beche-le-mer on shore, while those on board were putting the ship in order and nothing particular occurred until the 30th of January when the natives on shore maliciously set fire to our houses and destroyed 60 piculs of beche-le-mer, trade, clothes, etc., and the men with difficulty got on board the ship, at midnight. The next morning we discovered they had broken our kettles for the purpose of getting the wrought iron. We found their principal object in setting fire to our houses was plunder and we immediately sent for the King[21] or principal Chief of the Bay. He came on board and informed us that our houses, being built by an inferior Chief, were more liable to be troubled by the natives. He advised us to use the houses that were employed by the brig Quill, as he built them himself, and he being the King of the Island and Bay, the natives would not dare to trouble them. On the 2nd of February we commenced curing fish in the houses of the King, the blacksmith having mended the kettles.

[27]

On the 10th, as the beche-le-mer began to grow scarce on the reefs, it was determined on the advice of the King to go to another bay, about 40 miles distant and build new houses and employ the natives in that place. On February 19th, the launch, in charge of the 1st officer, was sent round to the Bay with 10 men to prepare for curing the fish and two days later, having taken on board all the things from the shore, we got underweigh and stood out of the Bay of Miamboo.

On the 23rd, we arrived safe in the bay called Aloa by the natives, and found the King with his men had completed the houses and were all prepared to prosecute the business of purchasing and curing the beche-le-mer. Here we continued to cure fish without any interruption till March 23rd, when the interpreter was dispatched about 90 miles to a place call’d Baratta to purchase hogs, with the Chief of that place.

We found on April 9th that we had upwards of 1000 piculs beche-le-mer, 350 pounds tortoise shell and some sandalwood, so we settled with the natives and burnt our houses[22] and put the ship in readiness to go to sea. Four days later the interpreter arrived, bringing 90 hogs, and informed us that the ship Clay,[23] Capt. Millet, of Salem, was at Bow and [28] had brought letters from our friends which the interpreter delivered to us.

On April 15th, 1830, we got underweigh and stood out of the bay of Aloa bound to Manilla. After passing through the inner reef and thinking ourselves safe at sea, we observed a very large coral reef with no passage through it and it being near night and the weather unfavourable, we immediately tacked and endeavoured to gain the harbour we had left; but finding it impossible, anchored outside, near a small island[24] with coral reefs and breakers all around us. The wind increased through the night to a violent gale obliging us to get our topmast down and pay out all on both cables. It continued to blow very hard for four days, the ship being in a very dangerous situation with a large coral reef only two cables length astern. Fortunately, on the 20th, it moderated and we got our masts on end and got underweigh and on the 22nd arrived safe in Miamboo Bay where we lay till the 25th waiting for a favourable wind to go to sea.

On the 25th of April, 1830, we again got underweigh and succeeded in passing out through the passages to sea and steered direct for Manilla. We had a tolerable passage and in fifty days saw the island of Samar at the entrance of the Strait of St. Bernadina and passing it proceeded through the Strait and on the 22nd June anchored in the Bay of Manilla, off Caviter, about nine miles from the city. We found here one American ship and a number of [29] English[25] and Spanish vessels. Got underweigh on June 27th and ran up to the city with the ship for the purpose of discharging our cargo, which was sold to Chinese merchants as the beche-le-mer forms an article of food and is eaten by the principal Chinese.

From a water-color in the possession of the Old Dartmouth Historical Society, New Bedford.

After having discharged the cargo and taken in a sufficient quantity of ballast, we shipp’d 8 Manilla sailors and put the ship in order for another voyage to the Fegees, taking on board some stores, and on the 17th of July we got underweigh and stood out of the Bay, intending to touch at the Sandwich Islands for the purpose of procuring water and fresh stock. On the 22nd, having passed through the Strait of St. Bernadino, we steered to the eastward and soon lost sight of the land. We had a tedious passage (though the weather was mild and pleasant) owing to the light winds which prevailed for most of the time. On the 16th of August we saw the Caroline Islands and on the 18th the Ladrone Isles. [On the 1st of Sept. spoke the ship “Zeneas Coffin,”[26] Capt. Joy of Nantucket on a cruise. On the 4th saw a number of whales and other smaller fish. On the 22nd was boarded by a boat from the whale-ship “Ann Alexander”[27] of New Bedford, Capt. Howland, on a cruise. On the 3rd of Oct. spoke ship [30]“Hector,”[28] Capt. Morse, of New Bedford, cruising for whales.—From Log Book.] After a passage of 84 days arrived at the Sandwich Islands, and on the 9th of Oct. anchored in Mowee Roads.[29] Found in this place one whale-ship[30] and a number of small schooners.

We immediately commenced getting our water and purchasing goats and vegetables for the use of the ship’s company. Many of the natives came on board and appeared very civil. The American Mission appeared to be in a very flourishing condition. A new church[31] nearly finished we observed and the missionaries appeared to have succeeded very well in reforming and civilizing the natives. We found this a most excellent place for watering and for procuring vegetables and fresh stock, etc., which we purchased very, very cheap for iron tools, etc.

On the 15th of October after having taken a sufficient supply of water, stock, etc., we sailed, steering to the southward, bound to the Fegees. We experienced fine weather and a regular trade wind and on the 6th of Novr. saw an island supposed to be Penrhyn’s Island,[32] which the Captain intended to [31] touch at for the purpose of procuring some grass for our live stock if possible. At 5 P. M. we were near to the shore when the natives came off in great numbers and appeared perfectly savage and fierce, hallowing and shaking their spears.

The Captain had given orders for every man on board to arm himself and prepare to resist them should they attempt to attack us. We endeavoured to trade with them and had succeeded in purchasing some cocoanuts when the Captain, in endeavouring to persuade one of the natives to come on board, another native fired his spear at the Captain and slightly wounded him in the neck. He immediately gave orders to fire at them which was accordingly done and 7 or 8 of the natives were killed. We immediately fill’d our sails and stood on our course leaving the natives to bewail the visit of civilized people to their uncivilized shores.

Passed the Tonga Islands on Novr. 16th and on the 18th saw Turtle Island, the southernmost of the Fegee Group. We passed through the passages between the island and on the 24th of Nov. anchored off Ovalou,[33] an island about 25 miles from Bow, the principal town of the Fegee Islands, where the [32] King of the whole group resides. Here the 1st Officer and interpreter left the ship for Bow to have an interview with the King [Tanoa] and on the 26th he came on board in a very large double canoe with some of his principal warriors and two of his wives. The Captain purchased some tortoise shell of him and contracted with him for 2 large houses on an island a short distance from Bow where, on the 1st Dec., we commenced curing beche-le-mer. The interpreter and the Manilla men were employed on shore with a number of English sailors which we hired for the purpose, but finding the beche-le-mer very scarce and the natives not well disposed towards us it was determined to remove from this place and endeavour to find some better place for procuring a second cargo.

Before we could get away a violent gale came on from the northward, on the 16th of Dec. and as our ship lay in an open roadstead, her situation became dangerous and beginning to drift and the reefs but a short distance astern, we let go both of our lower anchors and got our top-gall-masts down. The gale increased to such violence that our chain cable soon parted and the stream,[34] being the only anchor we had left on board, was immediately let go. That in a short time parted also and the ship drifted within [33] a cable length of the breakers, the sea running very high at the time. Our sheet cable still held on and the gale moderating considerable we rode out the gale until the next morning when the cable parted and we drove on to the reef before sail could be made on the ship. Fortunately for us the wind shifting suddenly and blowing off shore we were able to clear the rocks without doing the ship any injury.

We made all sail and after passing out to sea through the reefs we steered over towards the island of Somer-Some,[35] intending to purchase of the natives the cables and anchors of the brig Fawn[36] lately shipwrecked there, as we were wholly destitute of cables or anchors and it would be impossible to prosecute the voyage without a new supply.

Arriving at Somer-Some, on the 19th Dec. we succeeded in procuring 3 anchors and 2 chain cables which formerly belonged to the brig Fawn and also some rigging, and proceeded towards the island of Ovalou again to procure our anchors if possible and get our things from the shore.

On the 25th we anchored in the same place where we lost the anchors, but found it impossible to regain them so the boat was sent on shore to procure [34] stocks for the anchors we had on board. The next day, while the carpenter was employed in cutting the anchor stocks and the men were guarding him from the natives, whom we were suspicious of from their appearance, they rushed down from the mountains and attacked our men who immediately fled to the boat and succeeded in reaching it, excepting two men belonging to Salem, Edmund Knight[37] and Joshua B. Derby, whom the natives killed with their clubs, the latter having previously shot the Chief of the tribe. They took the muskets and stripped the dead bodies of our unfortunate men, those in the boat not being able to prevent them. Hearing the tumult in the ship, another boat was dispatched, armed completely, and succeeded in getting the bodies which we buried on shore. We soon learned the natives intended to attack the ship and immediately got our things on board and prepared the ship for sea. We got underweigh on the 29th Dec. and stood out through the reefs to sea and steered towards Miamboo Bay, where we anchored on the 31st and the 1st and 3rd officers landed for the purpose of passing over the mountains to Aloa Bay, to contract with the King (our friend of the former voyage) while the ship proceeded round to the Bay.

Now in the Peabody Museum of Salem

On the 1st Jan., 1831, the ship arrived in Aloa Bay and anchored near the place where our houses [35] were building, the officers having contracted with the Chief. On the 13th, the house being completed, we commenced curing beche-le-mer. The 1st officer, interpreter and ten men stayed on shore and the rest of the ship’s company commenced repairing the rigging which was found to be in a very bad condition. The head of our main-mast was rotted nearly off and after much trouble and delay a tree was found of sufficient size for a fish,[38] which was purchased of the natives. On the 27th we completed our mast and having refitted the rigging as well as circumstances would permit we prepared to receive our cargo, hoping to be able to prosecute our voyage without more delay which from a succession of misfortunes and accidents had been long protracted and was rendered extremely tedious and thus far unprofitable.

But we found our troubles were far from being at an end for on the 29th we found our principal house on fire which was burnt together with 100 piculs of beche-le-mer, some trade, etc. Another delay was unavoidable, but with the assistance of the King and other Chiefs, another house was soon completed and on the 4th of February we commenced fishing again.

We continued to cure beche-le-mer until the 13th with but little success, when the natives attempted to burn our houses again and appeared disposed to attack the men on shore if an opportunity offered. The Chiefs also seemed disposed to countenance [36] their tribes in their designs. We immediately manned and armed the boats and sent them on shore for the protection of our property and the men. In the morning, a slight attack was made by the natives on our people, but they were defeated without any loss on our side. As we killed a number of them and they perceived the superiority of our muskets over their weapons, they retreated into the woods. We got our things on board without any molestation from the natives and immediately put the ship in readiness for sea.

Finding it impossible to procure a cargo in this place we burnt the houses and got underweigh and stood out of the bay intending to proceed to Mutt-Water,[39] a town and bay on the north end of the island, where we arrived on the 17th and anchored near the shore about a musket-shot distance from the principal chief’s town. We immediately had an interview with the Chief and agreed with him to furnish houses for the purpose of curing beche-le-mer, the Chiefs agreeing to furnish canoes and men to man them, the 2nd Chief of the place, who was much loved and respected by the natives, agreeing to stay on board the ship, as a hostage for our men and property on shore. By the 21st of February the house was completed and we commenced purchasing and curing beche-le-mer.

We continued curing the fish and nothing particular occurred until the 22nd March, 1831, by which [37] time we had procured about 500 piculs of beche-le-mer and 300 pounds of tortoise shell. An accident then befell us which not only ruined our voyage but by which we lost all our property and were cast on the mercy of savages whose fierceness and ferocity are not equalled on the South Seas.

Our ship lay in a channel between a small island and the north end of the island of Tackanova[40] on which was the town and our beche-le-mer establishment at a short distance from the ship. The 1st officer, three of the crew, the Manilla men and several English sailors, whom we employed, were on shore curing beche-le-mer, when an excessive hard gale came on from E. S. E. about 8 P. M. on the 21st. At ten, all hands were call’d and the sheet anchor let go, but as the other cable was payed all out it could bring no strain until the ship began to drift. It continuing to blow very hard and every appearance of a hard gale coming, we proceeded to get our yards and masts down and at 3 P. M. having got the top-gall-masts and main-top-masts down we found the ship drifting and immediately let go the small chain-anchors, one of which was back’d with the ship’s kedge, and payed out a long scope on all the cables. We also got down the fore-top-masts and lower yards. At 9.30, the wind increasing and the ship having drifted so far as to be exposed to the sea, [38] which had now become very high and confused, we payed out the bitter end[41] of all the cables.

At 10 A. M. we perceived by the land, which could only be seen at intervals, that the ship had drifted 7 or 8 miles along the coast and was in a most dangerous situation, the current setting against us and the wind having increased to a hurricane, the sea running very high. Breakers were all round us and there seemed but little chance to save the ship, so we cut away the lower masts and with them went almost every moveable thing from the deck. The breakers were soon seen astern and at about 11 A. M. the ship struck on the shore reef, having drifted 10 miles from her anchorage. The sea soon drove her upon the reef where she bilged and fell over on her side, heeling in towards the land and protecting us from the sea which beat against her with great violence.

We were fortunate in having a chief[42] on board of considerable influence with the natives, who advised us to land if possible and proceed to the town, as the mountaineers would come on board for plunder and would not scruple to take our lives which he could not possibly prevent. Accordingly the ship was delivered to the chief and we proceeded to clear away the boats. Our launch went adrift and was lost in the beginning of the gale and when we lowered a quarter boat it immediately went to pieces. In the [39] two left, we, after much difficulty and danger, succeeded in reaching the shore in safety with no property but our clothes.

We soon met with a party of mountaineers, exceedingly fierce, who robbed us of our clothes, hardly leaving each one with a single garment, it not being in our power to prevent them, and leaving us exposed naked to the storm, without any shelter and perfectly ignorant of the road to the King’s town,[43] nor would any one of them be prevailed upon to show us the way. The savages soon left us and we proceeded on our way towards the town but from our ignorance of the right paths and the fury of the storm, our travelling was rendered exceedingly difficult and tiresome. The next morning, however, we found ourselves all safe in the King’s town. The King[44] and all the principal inhabitants had gone aboard the ship and the five that remained gave us the largest house where, without provisions of any kind and knowing our fate would not be determined until the arrival of the King and his men, we were forced to wait in a painful suspense two days.

After the gale had abated, the King came up from the ship, having plundered her of everything except the salt provisions and bread, and after a consultation with his priests and warriors, he proclaimed that our lives should be spared, that houses should be prepared for us and that we might be permitted [40] to secure what provisions from the ship we could. After hearing this law passed by the King and feeling confident it would be violated on no account, without his orders, our minds were greatly relieved and our spirits, which had been greatly depressed with our misfortunes, rose high with the hope of once more seeing our native country and leaving these savage shores where we had experienced, from the time we first arrived among them, so much trouble and so many misfortunes.

The King having lent us one of his large canoes, with which and our small boat (the only one sav’d from the wreck) we proceeded down to the ship for provisions. We found the natives greatly excited with their prize. The chief, however (who was on board when we struck), received us very well and gave us permission to take anything we pleased; but the natives had destroyed almost everything they had not carried off. Every part of her was ransacked and torn to pieces; the hull cut and hacked for the purpose of getting the iron work, and with pain we saw our unfortunate ship in a most wretched and miserable condition and with no hope of leaving the country till some vessel arrived.

From a photograph made in 1898.

We succeeded in getting 14 pounds of salt meat, a few casks of bread and some other little articles and returned to the town. The King prepared his largest church[45] for us to live in and a small house [41] for our provisions; gave us some cooking utensils and we made arrangements for our comfort and prepared to wait patiently until some relief came to us.

Having understood that there was another vessel among the group previous to our misfortune, it was determined by the captain, with the consent of the King, to proceed in the boat, with a crew, up to the Island of Bow, about 90 miles distant, to learn the fate of the vessel and if he found her safe to request the captain to come to our relief. Accordingly, on the 28th March, having fitted sails for the boat, layed in stores and ammunition, the captain, left us and proceeded on his voyage.

The King supplied us with yams and gave us a number of presents of clothes, and we continued to live on the most friendly terms with the natives. We were tolerably acquainted with their language and from a long acquaintance with them we were soon able to conform in some degree to the customs and manners. We found our King was the sovereign over a large part of the island of Tackanova (the second largest of the Group) and a number of smaller islands over which he reigned with an absolute sway. But he was subject to the King of Bow who was the great sovereign of the whole group.

[42]

The natives of these islands are remarkable from the other natives in these seas, not only from their extreme savage dispositions and eagerness to kill and eat their enemies, but from the dark colour of their skins and the manner in which they dress their hair. They allow it to grow at full length, when it is made very stiff by applying a mixture made of the ashes of burnt coral and then dyed in various colours; the grown people having it always black, when they pick it up into many curious shapes and being very thick and bushy their heads present a very singular and frightful appearance. Their bodies are nearly naked, with no covering except a piece of cloth made from the bark of a tree, wrapped around the waist; though they oil themselves with cocoanut oil which serves to protect their bodies from the rays of the sun and renders the skin soft and pliable.

The females wear a covering made of a sort of grass which is curiously interwoven and being of different colours presents a handsome appearance. Their bodies are oiled and their hair dressed the same as the men. Both sexes always lie with their necks resting on a stick so as not to injure the shape of their hair. The females, although at the complete disposal of the men, are not treated with great severity. They assist in tilling the ground, fishing and cooking; though a great part of their time is spent in fixing their hair. They display considerable ingenuity in making earthen-pots (which much resemble ours) and in making cloth nets.

[43]

The men of whatever rank are learnt the art of war and always carry their arms with them wherever they go. They are very ingenious in the construction of their houses and their war-weapons, but in particular in their canoes. Their houses are much like a one-story house in our country (but without windows) in their shape. They are framed of the limbs of trees seized together with a kind of sennet[46] made of the fibres of the cocoanut husk plaited together. On these are fastened small reeds and on them are secured the thatch with which the house is covered.

Their double canoes are formed of two single ones secured together by large timbers on which a platform is built and on which the sail is set and the natives stand. Single canoes have an outrigger and a platform built on the single canoe on which the sail is set. They commence building first by hollowing out the trunk of a tree, when planks are hew’d and seized on until it is of sufficient size, secured by timbers very much resembling those in a ship. The sail is made of mats, the rope of a kind of bark, and is so constructed as to be turned either way without the necessity of turning the canoe round when tacking at sea. The canoes are all fitted to sail either end first. They are sometimes very large containing [44] room for 4 or 5 hundred persons[47] and nearly as long as a ship. They sail remarkably fast and the natives are very expert in the management of them and as the natives all go arm’d, from their savage dress they present a very formidable appearance.

The natives of these islands believe in a Great Spirit whom they think lives in the sky and who made all things. In every town there are a number of priests whom the natives think are endowed with divine powers by the Great Spirit with whom he sometimes converses and informs them how to direct the people. These priests have great influence with the chiefs in declaring war and managing the affairs of the nation.

The principal amusements consisted in a kind of dance, singing songs relating to the war exploits and fishing expeditions, performing warlike manœuvres, and in drinking the ava[48] extracted from the ava-root, of which they are immoderately fond.

Brought to the United States in 1856 by Capt. Thomas C. Dunn, while on the bark Dragon of Salem. Now in the Peabody Museum of Salem.

A ceremony of this kind was performed almost [45] every morning at the King’s or one of the principal chief’s house and we always had an invitation to attend. A large bowl was prepared in which the cava or ava was put and mixed with water, when it forms a liquor which has much the same effect on a person as opium. The company sit round in a circle, the bowl in the centre, and while it is preparing, they all sing songs relating to some enterprise that is intended or perhaps past, the King having first invoked the Great Spirit to bless the liquor, the people all answering with a word which is equivalent to our amen. It was then carried round in cocoanut shells, the King drinking first, and so on according to the rank, though we always had the honour to drink next to the King. They always give a toast before drinking, frequently wishing the Great Spirit to bless us with a safe arrival to our country; sometimes that he might bless them with a great plenty of yams or fish.

We continued to live on good terms of friendship with the natives, which was much increased by our assisting them in repairing and learning them the use of the muskets and other weapons of which a great many fell into their hands. We always met with a welcome reception when we visited their houses and frequently received small presents of clothes, etc., for the work we did for them, so our situation became quite comfortable, although we could hardly suppress our feelings, to see our property and clothes destroyed, nor reflect on the great [46] distance we were from our homes and friends and the future prospects, without pain and anxiety.

About the last of April, 1831, the king fitted out an expedition of thirty large canoes to go to a place about 50 miles distant to procure certain tribute of the mountaineers which he obliged them to pay him. The King and all the principal warriors, with the women and ourselves, started in the canoes and in two days arrived at the place where we were to meet the mountaineers with the tribute. It was on a beautiful plain where houses were built for the King and the chiefs with their families.

After the King and chiefs were seated in the houses, a party of the women of the mountains marched out in front of our King, fancifully dress’d with flowers and strips of bark of various colours, each having a fish-net of superior workmanship and each bearing in her hand a sort of fan, with which they beat time to a sort of solemn tune which they sung. After performing a number of dances before the King, they divested themselves of their ornaments and nets which became the property of our women, and marched off followed by the shouts and praises of all our party.

A party of the men then presented themselves dressed with a large quantity of curiously-coloured cloth[49] and after performing various dances and [47] manœuvres and leaving their dresses for the men of our party, they marched for the mountains having likewise received the King’s approbation and our shouts and expressions of admiration.

The tribute was now examined by the King’s command. It consisted of 280 hogs, vast quantities of yams, cava-root, etc., on which the High-Priest of our nation envoked the Great Spirit for his approbation of the tribute. The priest, after a ceremony of twirling a cocoanut round two or three times, pronounced that it was very Good, and that it would be proper to have a feast of pork and yams, drink cava, etc. The King then gave orders for a certain number of hogs to be killed, the rest to be divided, and the cava got ready and as we had had nothing to eat for some days we all joined in obeying orders. Each one of the party, ourselves not excepted, received a portion of the provisions and while the King drank his cava, the people prepared the feast.

The King gave the mountaineers a few presents and a specimen of his eloquence in which he informed them that as the ship cast away on his shores had rendered him very powerful, he should expect a larger tribute the next year, giving them to understand he should be ready to use forcible means [48] if it became necessary. With this, the chief took his leave of us and we commenced, according to the advice of the priest, to eat. At night we repaired to the canoes with the tribute and on the next morning started for the town where on the 20th of April we arrived.

On our return, the 2nd officer of the ship, with the carpenter and a number of the crew, left in a canoe to go to Bow, having understood by the natives that a vessel was lost in the same gale that had wrecked our ship and that the Captain and crew resided there. We found the natives of another town, enemies to the King, had set fire to the Glide and she had burnt nearly up.

The 2nd chief, to whom the ship had been delivered, when we abandon’d her, was now taken sick and the priest continued to howl through the night for his recovery. On our asking the reason of such proceedings they told us that the priest was angry because a sufficient sacrifice of pigs had not been made and that the Great Spirit had caused a sickness to afflict the greatest warrior. A number of hogs were immediately killed and buried and numbers of the friends of the chief’s cut off a finger or toe[50] to satisfy the Great Spirit.

We learn’d that it was the custom to cut off their [49] fingers or toes on the death of their friends or on the sickness of their chiefs. We saw a number of very aged people who had become feeble and infirm, call round their friends and bid them farewell and then allow themselves to be strangled and buried without showing any signs of fear for the future or regret for leaving the past.

On the 6th of May we received a letter which was written previous to the gale, from which we learned that the vessel lost at Bow was the brig Niagara,[51] Capt. Nathaniel Brown, and that she was from Salem.

Nothing particular occurred until the 22nd of May, 1831, when a sail was seen standing for the anchorage at 5 P. M. At sundown we were on board and she proved to be the schooner Harriet, Capt. Young, from the Sandwich Islands and last from Wallis Island. They took us all on board the schooner and after procuring the cables, anchors, etc., of our ship we proceeded for Bow.

On the 9th of June, we arriv’d off Averlon and found there the bark Peru,[52] Capt. Egleston, of and [50] from Salem. Captain Egleston took Capt. Archer, Mr. Burnham and the remainder of our crew on board; likewise the Captains Brown and Vanderford[53] of the Niagara with the officers and crew and we proceeded on our course to Bow, where we arrived on June 10th, and anchored off the island where Mr. Manini, supercargo of the schooner, purchased the cables and anchors of the brig Niagara, from the King of Bow. Having succeeded in getting them on board we got underweigh and ran down to Avalon and anchored near the bark Peru. Capt. Brown came on board the schooner and Capt. Young agreed to forward us to the Sandwich Islands.

On the 26th of June, we lost sight of the Fegee Islands, steering to the N. E. for Wallis Island[54] and arriving there three days later, we found the brig Chinchilla,[55] Capt. Meek. Capt. Young not finding it for his interest to return to the Sandwich Islands at present, on the 12th July sailed, intending to return in the space of 6 or 8 weeks, leaving us to reside in their houses and wait for his return.

“Scrimshawed” on a whale’s tooth. Presented to the East India Marine Society of Salem in 1825 by Capt. William Osgood. Now in the Peabody Museum of Salem.

After a long and most tedious stay on this island, [51] on the 8th of November, the American whale-ship Braganza[56] arrived from a cruise off Japan for the purpose of procuring vegetables, water, etc. On the 26th, the brig Chinchilla arrived from Port Jackson, having been obliged to put into that port for provisions. Finding that Capt. Meek was not to return to the Sandwich Islands at present and no chance offering for a passage to a civilized port, I went on board of the Braganza, it being the intention of Capt. Wood to cruise for whales about the Equator for the space of 4 or 5 months and then to proceed to some port for supplies, where I should probably find an opportunity to return to the United States.

On Nov. 29th, we left Wallis Island and proceeded towards the Equator where we cruised until the 1st of February, 1832, and succeeded in taking 25 c. of Sperm Oil. Then finding the head of the main-mast rotted badly and the weather rather unfavourable for prosecuting the whaling business we bore away and steered for Otaheite and on the 23rd February we arrived at Eamco,[57] an island a short distance from Otaheite where the Captain intended to repair his main-mast. We found at Otaheite, the ship Atlantic, Capt. Fisher, who intended to cruise for a short time for whales and then proceed for the United States. I immediately shipped on board and [52] on the 28th February, signed his articles intending to sail the next day. Early the next morning we got underweigh and stood out to sea steering to the south east under short sail with the man at the mast-head looking for whales.

It was on the morning of 20th of April, just as the sun was rising, that the man at the mast-head cried out “There she blows!”[58]

It was very still on board; the ship steered close to the wind, a light breeze from east and not a sound heard except the slight ruffling the ship made as she forced her way through the water. But nothing could have acted so forcibly on our feelings as the cry that whales were in sight. In a moment the ship was in confusion, the sailors came up from below and ran to clear their boats and see all in readiness for the pursuit.

“Where away?” enquired the Captain, as he was coming up the companion-steps and without waiting for an answer ordered the ship to be hove to and the boats manned.

The order was promptly executed by the respective officers and on ascertaining they were sperm whales, he ordered the officers to lower the boats and pursue them. The whales were but a short distance from the ship and we had a good opportunity to observe their movements. The boats, sufficiently armed and manned, soon got amongst the whales, when the man at the mast-head had orders to inform [53] those on deck of the movements in the boats and to inform those in the boats by signals of the situation of the whales.

From an engraving by J. Hill after a painting by T. Birch. The picture shows the famous Roach (Rotch) whaling fleet,—the Enterprise, Wm. Roach, Pocahontas and Houqua, all from Nantucket.

In a few moments we perceived by a great splashing, which one of them made, that the 1st officer had hove his harpoon into one of them. After running under water some time and taking the line out of the boat to a considerable distance, the whale came up on top of the water. The other whales immediately joining the wounded one and gave the other boats an opportunity of striking also, which they immediately improved and all three of the boats were each fastened to a whale at the same time. After the whales became exhausted they hauled up to them and lanced until they were dead.

In this manner the boats continued to improve their time and weapons until 6 of these huge animals were forced to yield their valuable bodies to the superior skill of Nantucket whalemen. They were soon towed alongside the ship and secured by their tails being fastened to the bows. The crew then proceeded to take the blubber on board. Large tackles were secured on the main-mast, the falls taken to the windlass, and every person stationed in his particular place. The officers at the ship’s side, on stages, to cut the blubber as it is hove on board with the tackles. The harpooners on deck to receive the blubber and overhaul the tackles. The carpenter sharpening the spades, the cooperer preparing the casks, the seamen heaving at the windlass, and the Captain superintending the whole.

[54]

They commenced by cutting a hole in the blubber near to the head of the whale, into which a tackle was hooked which served to steady the whale while the officers cut off the head which was hoisted on board. They then proceeded to peel the blubber off the whale, the officers cutting it with their spades into strips about 6 or 8 feet in width and from 12 to 18 feet in length, while it is hove in with the tackles. This causes the whale to turn over and over until the blubber is all off, when they cut the carcass adrift and left it a banquet for the sharks and birds of which there were great numbers around the ship.

After having secured the blubber of all the whales sail was again made on the ship and we proceeded on our way around Cape Horn. In a few days the blubber was tried out and stow’d in the ship’s hold and thus ended what the whalers term’d a fare of sperm oil.

We had a tolerable passage to the United States and on the 25th June, arrived at Nantucket, 119 days from Otaheite, and on the 29th June, 1832, I reached my home in Danvers after having been absent 37 months and 8 days.

[2] Tasmania. William Endicott says in his Log of this voyage: “Van Diemen’s Island appears from the sea to be high and irregular barren land covered with snow to the summits. The shore is bound with craggy rocks.”

[3] Situated at the northerly end of North Island, this was the principal rendezvous of European and American vessels during the early intercourse with the Pacific. Endicott says in his Log: “The Bay of Islands is a fine place for procuring wood, water, potatoes, pigs and vegetables.”

[4] “Indiaman,” “Diana” and “Tower Castle.”

[5] “New Zealander” of New Zealand.

[6] The primitive Maori method of cooking bodies was to dig a hole in the ground about two feet deep in which was placed a quantity of stones. A fire was built over these and when they were red hot most of them were removed. Those remaining were covered with alternate layers of leaves and flesh until there was as much above as below ground. Two or three quarts of water was then thrown over the pile, old mats spread over it and the whole covered with earth to confine the steam. In twenty minutes the flesh was cooked. Cannibalism was entirely abandoned by 1840 owing to the influence of the missionaries.

[7] The Friendly or Tonga Islands are a group lying south-east of Fiji between 18° and 20° south latitude and 174° and 176° west longitude. They comprise some 150 islands, mostly very small, of which only a few are inhabited. They were discovered by Tasman in 1643 and became a British protectorate in 1900. The natives are of Polynesian stock and have become Christians through the efforts of the Wesleyan Mission established here in 1822. Probably the best early account of the natives of any Pacific islands is William Mariner’s “An Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands.”

[8] The Fiji islands are an important group of the Central Pacific lying largely between latitude 15°30′ and 19°30′ South and longitude 177° East and 178° West. They comprise some 155 islands, of which 100 are inhabited, and numerous islets and reefs. The group was discovered by Tasman in 1643 and was ceded to Great Britain by Thakombau on Oct. 10, 1874. The natives are of Melanesian stock with an admixture of Polynesian. The mountaineers of Vanua Levu show the purest strain while the costal tribes of that and the surrounding islands show a very pronounced strain of Tongan blood. All are now Christian through the efforts of the Wesleyan missionaries who went there in 1835 and a white man or woman is safer with these natives than on the streets of New York or Chicago.

[9] The result of the infusion of Tongan blood.

[10] War was the chief object in life for the Fijian man and so great was the desire for killing that two men always walked abreast for fear that if one were behind he would be overcome by the temptation to club his companion.

[11] Cannibalism was not practised exclusively on those killed in war. It was tabu or forbidden to the lower classes and they were most frequently the victims. Sometimes if a chief wanted a body for a feast he would send one of his dependents out to waylay a man of the lower classes. He would approach his unsuspecting victim from behind and strike him on the head with a club before he was aware that anything was to happen. Persons dying a natural death were never eaten but those shipwrecked were rescued only that they might be eaten. Neither sex nor age was a deterrent. One chief was so fond of human flesh that he boasted that he never passed a person that he did not wonder how they would taste. The method of cooking bodies was either by baking, in a manner similar to that practised in New Zealand (see note, page 16), or by boiling. The body was rarely baked whole but was dismembered and the trunk cast aside unless the supply was very short.

[12] Turtle Island—Vatoa.

[13] Civil account—civil day. When at sea the log-book day corresponded with the astronomical day and extended from noon to noon; but when anchored for any extended period of time the log-book record was kept in civil time, that is from midnight to midnight.

[14] Mbau or Ambau, a native town on a small island at the southerly end of Ambau Bay on the easterly side of Viti Levu, the largest island of the Fiji group. This town was the residence of Tanoa, the most influential chief in the Islands. It was off this town that the French brig “l’Amiable Josephine” was cut off by the chiefs of Rewa (or Viwa, a town on Viti Levu, the second most influential town in Fiji) in July, 1834, and the captain and all the crew but three were killed. In retaliation for this Dumont D’Urville destroyed the town of Viwa in 1839. In August, 1834, the chief Vendovi of Rewa massacred the mate and five men of the crew of the brig “Charles Doggett” of Salem. One of the crew was eaten.

[15] Brig “Quill,” of Salem, 189 tons, built at Hingham in 1818. Owned by John W., Nathaniel L. and Richard S. Rogers; commanded by Joshua Kinsman.

[16] Mr. Driver.

[17] Oahu, Hawaiian Islands.

[18] An edible holothurian familiar throughout the East under the Malay name of trepang.

[19] William S. Carey.

[20] From the Malay “to carry on the back”,—a man’s burden. A commercial weight varying in different countries. In the Philippines, where the beche-de-mer was sold, it was 140 lbs.

[21] Tanoa, the most powerful chief in the Islands. He was the father of Thakombau, the most celebrated of the Fijian chiefs and the greatest stumbling block to the missionaries until he was forced as a matter of expediency to adopt the Christian religion in 1854.

[22] The houses were burned so that they might not be used by other traders.

[23] Ship “Clay” of Salem, 299 tons, built at Hanover, Mass., in 1818. Owned by John W., Nathaniel L. and Richard S. Rogers; commanded by Charles Millett.

[24] Anganga Island.

[25] Including the ship “Sophia” of London.

[26] Ship “Zeneas Coffin” of Nantucket, 338 tons, owned by C. G. and H. Coffin; commanded by George Joy.

[27] Ship “Ann Alexander” of New Bedford, 211 tons, owned by George Howland; commanded by Josiah Howland.

[28] Ship “Hector” of New Bedford, 380 tons, owned by Charles W. Morgan; commanded by John G. Morse.

[29] Maui, the second largest island of the Hawaiian group.

[30] Ship “Atlantic” of Nantucket, 321 tons. Commanded by Elihu Fisher.

[31] This church at Lahaina, Maui, was said at the time to be “the most noble structure in all Polynesia.”

[32] Penrhyn or Tongareva was discovered by Seaver in the ship “Lady Penrhyn” in 1788. When visited by the “Popoise” of the Wilkes’ Expedition in 1841 the natives were described as the wildest and most savage-looking beings that had been met with.

[33] Ovalau, a small island about 10 miles east of Viti Levu. On this island is situated the town of Levuka whose harbor is one of the best in the islands. It was the principal residence of white men in the group and was the seat of the British colonial government until 1882, when it was removed to Suva on Viti Levu.

[34] The anchors usually carried were: sheet anchor, the largest and strongest which is only used in time of direst necessity; the best bower anchor and the small bower anchor, about the same size and take their name from their position at the bow of the ship; the stream anchor, smaller than the bowers; and the kedge anchor, smallest of all.

[35] Somosomo, a town of considerable importance, situated on the island of Taviuni or Vuna off the south-eastern point of Vanua Levu the second largest island in the Fiji group.

[36] Brig “Faun” of Salem, 168 tons, built at Quincy in 1816. Owned by Robert Brookhouse of Salem, George Abbot of Beverly and Hall & Williams of Boston; commanded by James Briant. Wrecked in August 1830 on the Cakaudrove coast of Vanua Levu in the bay now called Faun Harbor.

[37] Charles Ambrose Knight, 1st mate of the ship “Friendship” of Salem, a brother of Edmund, was massacred in February 1831, by the natives at Quallah Battoo, Sumatra.

[38] Fish—a piece of timber, somewhat in the form of a fish, used to strengthen a mast or yard.

[39] Mutt-Water or Mudwater, a town on the north side of Vanua Levu. The native name was Bonne Rarah.

[40] Tackanova—Vanua Levu.

[41] The “bitter-end” is that part of the cable which is abaft the bitts when the ship rides at anchor.

[42] Chief Santa Beeta of Bonne Rarah.

[43] Bonne Rarah.

[44] Mah—Mathee.

[45] The bure or temple was the council chamber and town hall of the village. Strangers were entertained there and the head persons of the village often slept in it. As the best constructed building in the village it was elaborately decorated, the timbers and rafters being wrapped with sennit in various designs of red and black. Votive offerings such as clubs, huge rolls of sennit, whale’s teeth, strips of masi, a model of a temple made of sennit or parts of a victim slain in war, decorated the interior.

[46] Sennit—a cord made of the fibre of the cocoanut husk, dried, combed and braided. The Fijians having no nails use this for all sorts of fastenings, lashings and wrappings in varied design. It is made in all sizes from a single strand to a cable and is of very considerable strength.

[47] This statement seems to be somewhat exaggerated. One canoe has been recorded as one hundred feet in length. Wilkes says that the average large canoe was seventy feet in length and would conveniently carry fifty men.

[48] Yaquona of the Fijians, kava of the Tongans and awa of the Hawaiians, is an infusion of the root of the pepper plant (Piper methysticum). The root is first chewed or grated, after which the macerated mass is placed in a bowl and covered with water. The infusion is then strained through a fibre mesh and is ready to drink. It was used on occasions of ceremony or entertainment and its preparation was accompanied by a more or less elaborate ritual. It is used by the races in the Pacific who do not chew the betel nut. Its effects are intoxicating and narcotic.

[49] Tapa cloth, masi of the Fijians, siapo of the Samoans, kapa of the Hawaiians, was the substitute for cloth and paper. It was made from the inner bark of the paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera). The plants were carefully cultivated and when about one inch in diameter were cut down and soaked in water. The bark was removed and beaten. Different pieces were joined together and beaten into one piece so that sheets of almost any size could be made. The finished masi was then decorated by printing or stencilling with dyes of red-brown and black.

[50] One of the chief forms of mourning for the dead, in addition to wailing, was to lop off the little finger of one of the hands. Most of the older natives lost both little fingers. This was confined to the relatives of the deceased unless the latter was one of the highest chiefs when it was confined to the tribe.

[51] Brig “Niagara” of Salem, 246 tons, built at Mount Desert in 1816. Owned by Putnam I. Farnham, Jed Fry and Peter S. Webster; commanded by Nathaniel Brown. Wrecked in Ambau Bay the same day as the “Glide.”

[52] Bark “Peru”, 210 tons, built at Salem in 1823. Owned by Stephen C. Phillips; commanded by John H. Eagleston. Sold to Spanish owners at Manila in 1832. Capt. Eagleston commanded four different vessels in the Fiji trade, was familiar with the language and was on friendly terms with several of the chiefs. He rendered great assistance and furnished valuable information to Lieut. Wilkes while the U. S. Exploring Expedition was at the Fijis.

[53] Capt. Benjamin Vanderford of Salem made many voyages to the Fiji Islands and was familiar with the manners, customs and language. He was afterwards master’s mate and pilot on the U.S.S. “Vincennes” during the Wilkes’ Exploring Expedition and died, March 23, 1842, on the passage home.

[54] Uvea, northeast of Fiji. Discovered by Maurelle in 1781 and again by Wallis in 1797.

[55] Brig “Chinchilla” of New York; commanded by Thomas Meek of Marblehead.

[56] Ship “Braganza” of New Bedford, 217 tons. Owned by Phillips, Russell & Co.; commanded by Daniel Wood. Altered to a bark in 1859 and condemned at Honolulu in 1862.

[57] Eimeo, one of the Society Islands about 10 miles north west of Tahiti.

[58] This account of whaling may have been abstracted by Mr. Endicott from some now unidentified source.

[55]

By an Eye Witness

(Reprinted from “The Danvers Courier,” Aug. 16, 1845)

Mr. Editor. Finding myself in possession of a little spare time, I feel disposed to improve it in overhauling a range or two of memory, and agreeably to promise to commit such of it to paper as may seem of interest, touching on incidents which occurred at the Fejee Islands while on board the Old Ship Glide.

It was on a pleasant afternoon in the month of March, 1831, our ship at anchor off the town of Bona-ra-ra, the crew on board employed in making senett, spun-yarn, yard mats, and other ship gear to fill up the chinks of time, and particularly the ship’s lockers with such articles as are sure to come in play on shipboard, when you have not time to make them.

We were not very busy, neither were we idle; but it was just one of those sort of days at the Fejees when all hands had been hard at work all the forenoon, boating oil to the ship, beche-le-mer, weighing, and stowing it away in the hold, and having once more cleared up decks, felt released from the regular day’s duty, and indulged ourselves in a sail [56] privilege of telling tales, singing songs and reflecting upon “better days gone by.”

Our reveries and yarns were unbroken by any orders from aft except, to strike the bell every half hour, which if it had no other purpose reminded us that thirty minutes more had drifted astern upon the sea of time.

Five bells had been ordered from the quarter deck. I arose to execute the command, when my attention was drawn to the shore by seeing a large collection of savages on the beach, walking towards the town. Having struck the bell, I proceeded to the side of the ship where a canoe with five or six women had just arrived, to sell us fruit. I enquired of them what was the matter on shore. They immediately told me that the men had been to a fight with the Andregette tribe (who lived about thirty miles in the mountains), were victorious and had killed and taken three of their enemies, and were now going to have a grand Soleb, or feast.

I had heard David Whippy, a man who had long been a resident upon these Islands, tell many a long tale of the manners and customs of the natives, and especially of their cannibalism, and I had a strong desire to see the manner in which they prepared and ate human flesh.

While I was considering whether I would ask the liberty I wished, or not, Capt. Archer came up and stood in the companion way. I went aft, made known to him my request, when he replied, “I have no objection but take care of yourself.”

Wearing “maiden locks” indicating that they are unmarried.

[57]

This admonition was gratefully received, yet I felt by no means alarmed, having spent a great portion of my time on shore among the natives, with whom I was on terms of perfect friendship and good will, a circumstance well known to the Capt. or I should probably have received at once from him a denial of my wish to be absent from the ship on such an occasion.

I went down to my chest and brought up a few beads, which I gave to the women in the canoe, telling them I wished to be paddled ashore. They immediately threw their fruits consisting of a few cocoanuts and plantains, through one of the ship’s ports upon deck and considering the beads a compensation for both fruit and passage I was soon on my way to the shore.

I landed upon the beach just ahead of the savages who were coming single file to the village, entering it however by a very circuitous route and in a manner never done except on such occasions.

There were about sixty warriors, though a great many others were in attendance who had joined them while nearing the village.

The bodies of the three dead savages were carried in front, lashed on long poles in a singular manner. They were bound with wythes by bringing the upper and lower parts of the legs together and binding them to the body, and the arms in a similar manner by bringing the elbows to rest on the knees, and their hands tied upon each side of the neck. Their backs were confined to poles which were about [58] twelve feet long. One was lashed on each pole, with six men, three at each end, to carry it.

Those who carried the bodies walked with a limping gait, bending their left knees almost to the ground, but doing it in exact time with the war song they were singing.