[i]

MEDIEVAL

RHETORIC AND POETIC

[ii]

[iii]

MEDIEVAL

RHETORIC AND POETIC

(to 1400)

INTERPRETED FROM REPRESENTATIVE

WORKS

BY

CHARLES SEARS BALDWIN

PROFESSOR OF RHETORIC IN COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

GLOUCESTER, MASS.

PETER SMITH

1959

[iv]

Copyright, 1928

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

Reprinted, 1959

By Permission of

MARSHALL W. BALDWIN

[v]

SANCTO THOMÆ AQVINATI

PHILOSOPHO POETÆ

ARTEM ILLIVS SÆCVLI

RHETORICAM ATQVE POETICAM

REDINTEGRATAM

COMMENDAT INTERPRES

[vi]

The rhetoric and the poetic of any age, as the complementary

theories of composition, are indicative of its

habits in education and in literature. Thus their medieval

history concerns all students of the middle age. For

consecutive interpretation in this single aspect both supplements

the more comprehensive surveys and adds significance

to many special studies. Whether for initiation,

for review, or for suggestions of further inquiry, medieval

rhetoric and poetic offer a directly literary guide.

As in my preceding volume, Ancient rhetoric and poetic,

conciseness has been sought by proportion. Space is

given to those salient tendencies which mark the literary

course. Minor relations and collateral studies, indicated

no less carefully, are relegated to the notes, but included

in the index. Detailing the actual theory and the actual

practise of composition, often for the first time, I have

tried no less to show their bearing, to make medieval

rhetoric and poetic available by interpreting them in

historical sequence. Thus are interpreted the tasks of

the schools, the poetic developments of and from the

hymns, the habits of prose rhythm, the encroachment of

logic upon rhetoric and of rhetoric upon poetic, the progress

of verse narrative.

Ancient theory being eminent in a few cardinal texts

long recognized as representative, the former volume

subordinates history to exposition. Medieval theory, on

the other hand, being best grasped as development from

an inheritance, the plan of the present volume is historical.

[viii]Though each aims at sufficiency within itself, the second

refers again and again to the first, and the two volumes

together offer a history down to 1400. Throughout this

history rhetoric and poetic are seen to be indeed complementary.

Where they were distinguished, as where

they were confused, they are most fruitfully studied side

by side. Each illuminates the other because their relations

are always significant historically.

Their medieval history must begin with those particular

influences from antiquity which were transmitted through

the last schools of the Roman Empire, especially through

the schools of Gaul. It is a Latin history; for contact

with Greek was soon lost and was not widely reëstablished

till the Renaissance. But in the imperial centuries before

the separation East and West, Greek and Latin, agreed

so far in literary ideals and practise that the whole Mediterranean

basin had a substantially common system of

education through rhetoric. An inert survival of what is

known historically as the second sophistic, this was

sharply challenged by St. Augustine’s reversion through

Cicero to the elder tradition for authority to direct the

real oratory of preaching. Nevertheless the schools of

Gaul continued the sophistic tradition beyond the fall

of Rome.

Nor were the large philosophy of rhetoric in Cicero’s

De oratore, the great survey of Quintilian, the later medieval

guides. The prevalent textbooks were Cicero’s

youthful digest De inventione and a second book universally

attributed to him, the Rhetorica ad Herennium.

Though the survival of these minor works may be due

partly to the accidents of manuscripts, their persistence

has other causes. De inventione reduces to summary

what the middle age taught least, those counsels of preparation

[ix]and ordering which ancient teaching had progressively

adjusted to oral discourse, and for which the earlier

middle age had less opportunity. The Rhetorica ad Herennium,

comparatively summary also as to analysis and sequence,

is devoted largely to style, and reduces stylistic

ornament to a list so conveniently specific that medieval

schools made it a ritual. Though the greater Cicero and

Quintilian were known to such original minds as Gerbert

in the tenth century and John of Salisbury in the twelfth,

they were hardly available for the usual course of teaching.

Medieval rhetoric was generally a lore of style. Here

rhetorica tended to coincide with that school study of

Latin poetry which was a recognized function of grammatica.

The constant quotation of Horace’s “Ars poetica”

is one of the signs of the merging of poetic with rhetoric.

The conventional doctrine from both was largely of

descriptive dilation. Among the effects of this teaching

which outlast schooling and reach beyond Latin are certain

conventions of vernacular poetry. Conversely,

poetic advance in the vernaculars is seen in breaking away

not only from school rhetoric, but from rhetoric altogether.

The main medieval fields proper to rhetoric were sermons

and letters. The former, exploring their rhetoric

in the earlier centuries, continued to feel the example,

perhaps more than the precept, of St. Augustine. Even

the Dominicans had no need to seek a new lore of oral

composition. What is distinctive in sermon composition

of the twelfth century is oftener poetic than rhetoric.

Letters, on the other hand, are at once a legitimate application

of ancient rhetoric and a distinctively medieval

development. They practically comprehend the medieval

rhetoric of written prose. Though ordinary routine was

largely content, as in any other time, with correctness,

[x]and therefore with recipe and formulary, serious study

of both composition and style is evident in the better

manuals, and conspicuous in those achievements which

are part of medieval literature.

The teaching of poetica, from of old a part of grammatica,

included extensive practise in Latin verse. This

had early to take account of that dominance of stress

which had gradually supplanted the ancient control by

time. The characteristic medieval achievements in Latin

lyric are the hymns. Radiating into other songs, even

into humorous and satirical verse, the hymns were the

common lyric fund of medieval Latin. As early as St.

Ambrose they had created a new Latin poetry; and the

beauty of their various art was not exhausted with Adam

of St. Victor. Meantime they opened to the vernaculars

those poetic possibilities of stanza which arise from the

development of rime. Medieval poetic theory, on the

contrary, went but a little way. Mainly pedagogical

formulation, it lagged far behind the most characteristic

medieval poetic advance, which was in verse narrative.

Here is a sharp contrast with the Renaissance. The

fifteenth century opens a long series of critical inquiries

into poetic. The middle age, merging poetic with rhetoric

in the schoolroom, was little concerned to make it tally

with vernacular achievement. With the death in 1400

of Chaucer, whose criticism exposed this lack, the poetic

of medieval narrative reaches its term.

I owe to the unstinted courtesy and scholarly interest

of a trustee of Barnard College, Mr. George A. Plimpton,

the privilege of studying at leisure his manuscript of

one of the most important Bolognese dictamina, the

thirteenth-century Candelabrum. Far better than Boncompagno

or Thomas of Capua, better even than Conrad,

[xi]this unprinted manual exhibits dictamen in both scope

and method. My other debts are too manifold to rehearse.

The bibliographical notes, if they recorded the

reading of years, would defeat their proper object of

serving further study. Therefore they have been made,

as in the former volume, at once specific and strictly selective,

applied to each chapter separately, and further

indicated both in the index and on a page of recurring

abbreviations after the table of contents.

As I record gratefully my obligation for generous help

with the proofs to my colleagues Professors Ayres, Clark,

Krapp, McCrea, Moore, Perry, and Van Hook, and to

my old friend, the Jesuit scholar Dr. Donnelly, I see further

in such coöperation great promise for the progress of

medieval studies.

C. S. B.

Barnard College

Columbia University

January, 1928.

[xii]

| CHAPTER |

|

PAGE |

| I. |

THE SOPHISTIC TREND IN ANCIENT RHETORIC |

1 |

|

A. The Two Historic Conceptions of Rhetoric |

2 |

|

B. The Second Sophistic |

8 |

|

1. Philostratus, Lives of the Sophists |

8 |

|

2. The Character of Sophistic |

9 |

|

a. virtuosity |

9 |

|

(1) declamatio |

10 |

|

(2) improvisation and memory |

13 |

|

(3) delivery |

16 |

|

b. dilation |

17 |

|

(1) ecphrasis |

17 |

|

c. pattern |

20 |

|

(1) the elementary exercises of Hermogenes |

23 |

|

d. elaboration of style |

39 |

|

(1) literary allusion and archaism |

40 |

|

(2) decorative imagery |

41 |

|

(3) balance |

42 |

|

(4) clausula |

48 |

|

(5) vehemence |

49 |

| II. |

ST. AUGUSTINE ON PREACHING (DE DOCTRINA CHRISTIANA, IV) |

51 |

| III. |

THE LAST ROMAN SCHOOLS AND THE COMPENDS (FIFTH TO SEVENTH CENTURIES) |

74 |

|

A. The Schools of Gaul |

75 |

|

1. Ausonius |

75 |

|

2. Sidonius Apollinaris |

78 |

|

3. Textbooks |

87 |

|

a. grammatica and dialectica |

87 |

|

b. rhetorica |

89 |

|

[xiv]

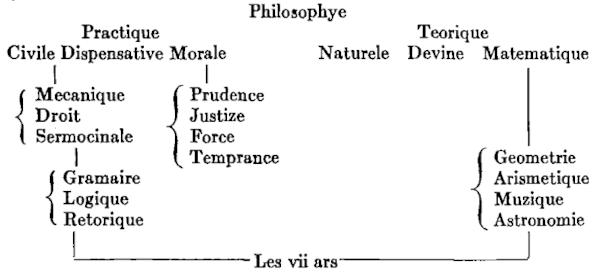

B. The Trivium in Compends of the Seven Liberal Arts |

90 |

|

1. Martianus Capella |

91 |

|

2. Cassiodorus |

95 |

|

3. Isidore |

95 |

| IV. |

POETIC, OLD AND NEW (FIFTH TO SEVENTH CENTURIES) |

99 |

|

A. Claudian and Boethius |

100 |

|

B. Prudentius, Sedulius, Fortunatus |

103 |

|

C. The Earlier Latin Hymns |

107 |

|

1. Iambic |

116 |

|

2. Trochaic |

119 |

|

3. Other Measures |

121 |

|

4. Poetic Conceptions |

123 |

| V. |

THE CAROLINGIANS AND THE TENTH CENTURY |

126 |

|

A. The Trivium in the Greater Monasteries |

127 |

|

B. Grammatica |

130 |

|

1. Poetica |

130 |

|

2. Hymns |

132 |

|

a. iambic |

132 |

|

b. trochaic |

134 |

|

c. other measures |

136 |

|

3. Narrative Hexameters and Elegiacs |

140 |

|

C. Dialectica |

141 |

|

D. Rhetorica |

142 |

|

E. The Poetic of Germanic Epic |

145 |

| VI. |

RHETORIC AND LOGIC IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES |

150 |

|

A. The Trivium at Chartres, Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries |

151 |

|

B. The Trivium in Hugh of St. Victor |

153 |

|

C. The Metalogicus of John of Salisbury |

156 |

|

D. Thirteenth-Century Surveys |

172 |

|

1. Alain de Lille, Anticlaudianus |

172 |

|

2. Vincent de Beauvais, Speculum doctrinale |

174 |

|

[xv]

3. St. Bonaventure, De reductione artium ad theologiam |

176 |

|

4. Brunetto Latini, Trésor |

178 |

| VII. |

LATIN POETIC IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES |

183 |

|

A. Doctrinale and Græcismus |

184 |

|

B. Poetria |

185 |

|

1. Matthieu de Vendôme, Ars versificatoria |

185 |

|

2. Geoffroi de Vinsauf, Poetria nova |

187 |

|

3. Évrard, Laborintus |

189 |

|

4. Johannes de Garlandia, Poetria |

191 |

|

5. Common Traits |

195 |

|

C. Hymns |

197 |

|

1. Progress of Rimed Accentual Verse |

197 |

|

2. Variations in Trochaic Stanza |

201 |

|

3. Symbolism |

203 |

| VIII. |

DICTAMEN |

206 |

|

A. The Rhetoric of Dictamen |

213 |

|

B. Digest of Candelabrum I-V |

216 |

|

C. Cursus |

223 |

| IX. |

PREACHING |

228 |

|

A. Vernacular to the People, Latin to the Clergy |

232 |

|

B. Collections |

233 |

|

C. Manuals |

236 |

|

D. Symbolism |

239 |

|

E. Composition |

245 |

|

1. Imaginative Method |

245 |

|

2. Logical Method |

247 |

|

F. Style |

250 |

|

1. Rhythm |

250 |

|

2. Balance and Rime |

251 |

|

3. Refrain |

254 |

| X. |

POETIC ACHIEVEMENT IN VERNACULAR |

258 |

|

A. Lyric and Epic |

258 |

|

[xvi]

B. Experiment and Convention in Romance |

260 |

|

1. Romance in Latin and in Vernacular |

260 |

|

2. Walter Map and Marie |

261 |

|

3. Chrétien de Troyes |

264 |

|

4. Conventional Composition |

267 |

|

C. The Poetic Composition of the Divina Commedia |

269 |

|

D. The History of Medieval Verse Narrative in Chaucer |

280 |

|

1. Poetic Conventions in the Earlier Poems |

281 |

|

2. Poetic Innovation in the Troilus and Criseyde |

284 |

|

3. Criticism of the Poetriæ |

289 |

|

4. The Poetic of the Canterbury Tales |

296 |

|

SYNOPTIC INDEX |

303 |

|

INDEX |

307 |

[xvii]

ABBREVIATIONS RECURRING IN THE NOTES

[The abbreviations used in each chapter will be found with the

list of references below the chapter heading.]

| AH |

Dreves and Blume, Analecta hymnica medii ævi, Leipzig,

1886-1911 (cited by volume and page). |

| ARP |

Baldwin (C. S.), Ancient rhetoric and poetic, New York,

1924. |

| Clerval |

Clerval (l’Abbé A.), Les écoles de Chartres au moyen âge, du

Ve au XVIe siècle, Chartres, 1895. |

| CSE |

Corpus scriptorum ecclesiasticorum latinorum, Vienna. |

| F |

Faral (E.), Les arts poétiques du XIIe et du XIIIe siècle,

recherches et documents sur la technique littéraire du moyen âge,

Paris, 1924. |

| Halm |

Halm (K.), Rhetores latini minores, Leipzig, 1863. |

| Keil |

Keil (H.), Grammatici latini, Leipzig, 1870-1880 (cited

by volume and page). |

| Manacorda |

Manacorda (G.), Storia della scuola in Italia, volume

I, Il medio evo, Milan, 1913 (2 parts in separate volumes). |

| Manitius |

Manitius (M.), Geschichte der lateinischen Literatur des

Mittelalters, Munich, 1911, 2 vols. (in Von Mueller’s Handbuch

der klassischen Alterthums-Wissenschaft, IX, ii). |

| Mearns |

Mearns (J.), Early Latin hymnaries, an index of hymns

in hymnaries before 1100, Cambridge (University Press), 1913. |

| MGH |

Monumenta Germaniæ historica (cited by page of the

appropriate volume). |

| NE |

Notices et extraits des manuscrits de la Bibliothèque

Nationale ... (cited by volume, part, and page). |

| PL |

Patrologia latina (Migne, cited by volume and column). |

[1]

CHAPTER I

THE SOPHISTIC TREND IN ANCIENT RHETORIC

References and Abbreviations

| Ameringer |

Ameringer (T. E.), The stylistic influence of the second

sophistic on the panegyrical sermons of St. John Chrysostom,

Washington, 1921 (Catholic University of America Patristic Studies). |

| ARP |

Baldwin (C. S.), Ancient rhetoric and poetic, New

York, 1924. |

| Boulanger |

Boulanger (A.), Ælius Aristide et la sophistique dans la

province d’Asie au ii siècle de notre ère, Paris, 1923. |

| Burgess |

Burgess (T. C.), Epideictic literature, University of

Chicago Studies in Classical Philology III (1902), 89-251. |

| Campbell |

Campbell (J. M.), The influence of the second sophistic on

the style of the sermons of St. Basil the Great, Washington,

1922. |

| Guignet |

Guignet (M.), St. Grégoire de Nazianze, orateur et épistolier,

Paris, 1911. |

| Hubbell |

Hubbell (H. M.), The influence of Isocrates on Cicero,

Dionysius, and Aristides, New Haven (Yale dissertation), 1914. |

| Méridier |

Méridier (L.), L’influence de la seconde sophistique sur

l’œuvre de Grégoire de Nysse, Paris, 1906. |

| Wright |

Wright (W. C), Philostratus and Eunapius, the lives of

the sophists, with an English translation, London and New

York, Loeb Library, 1922. |

[2]

A. The Two Historic Conceptions of Rhetoric

Plato’s distrust of rhetoric is a permanent reminder.

It is so significantly typical that it recurs throughout the

history of education, and must recur. Again and again

educational practise has found that it cannot do without

rhetoric; again and again educational theory has grudgingly

inquired what to do with it. For distrust of rhetoric

may be more than the impatience of the philosopher with

the orator, of speculation with ordered presentation, of

the quest for truth with persuasion. This is involved too;

for philosophers have often been impatient of presentation.

They have wished to think aloud, or to question

and answer, or merely to analyze for themselves, without

being held to consecutive explanation. Plato himself

falls short of discerning the importance of making truth

available and effective for the mass of men incapable of

scientific analysis; and this is the ground of Cicero’s rejoinder.[1]

But Plato’s distrust is more deeply of rhetoric

as he heard it taught. Even in his day Greek rhetoric

was largely sophistic, the rhetoric of personal display and

triumph. In the Gorgias[2] Socrates admits the function

of a nobler rhetoric, but cannot find it in use. In the

Protagoras[3] he asks the vital question, “About what does

the sophist make a man more eloquent?” In the Phædrus,

which discusses rhetoric more specifically, his satire is

most evidently of sophistic. To this the ultimate objection

is moral. A man should train himself “not with a

view to speaking and acting before the world, but for the

sake of making himself able ... to please the gods.”[4]

Plato challenges not merely the method of the sophists,

[3]but their ideal. Since rhetoric has almost always had some

part in education, and since it always ultimately involves

morality, Plato raises a leading question.

The ultimate, the only final answer to Plato’s challenge

is the Rhetoric of Aristotle. This proceeds from a conception

not only larger than the sophistic of Gorgias and

Protagoras, but also significantly divergent in aim. The

true theory of rhetoric as the energizing of knowledge,

the bringing of truth to bear upon men,[5] is there established

for all time. Aristotle amply vindicated rhetoric

by defining its place among studies, its necessary correlation

with inquiry and with policy, its permanent function.

He settled the question of rhetoric philosophically. He

established its theory. But this theory was oftener accepted

than followed. The sophists had, indeed, been

put in their place more surely by Aristotle than by Plato;

but they continued to thrive, until ancient rhetoric became

more and more sophistic.

The conception animating the practise and the teaching

of sophistic, far from being limited to antiquity, is medieval

as well, and modern. Apparently it is permanent.

Rhetoric is conceived by Aristotle as the art of giving

effectiveness to truth; it is conceived alike by the earlier

and the later sophists and by their successors as the art

of giving effectiveness to the speaker. The conceptions

are not contradictory. The second may be theoretically

included within the first; and actually Demosthenes may

learn something from Isocrates. But to embody them

in educational procedure, to carry out either as the controlling

idea of a course of study, is to discover that sooner

or later they become practically incompatible. Ingenuous

youth will be devoted either to energizing truth or to

[4]exploiting itself. There will come a parting of the ways;

for the two conceptions are divergent. What Aristotle

discerned as differentiating is differentiating still. The

flaw in sophistic is moral. It may not impair technical

training; but by deviating motive it tends to impair education.

For Aristotle’s theory is a touchstone. To recall rhetoric

to the true function discerned by him has repeatedly

been the object of reform in teaching. What has intervened

to deviate rhetoric and frustrate its best use has

again and again been the preoccupation with giving

effectiveness not to the message, but to the speaker.

Ancient sophistic is thus typical. It is not merely historical;

it is historic. The false conception divined by

Plato, and exposed finally by Aristotle’s demonstration

of the true conception, led ancient rhetoric through empty

personal triumphs into an elaborate art of display, devoid,

at its worst, of other motive. As sophistic spread, as its

idea of rhetoric became dominant, ancient education was

narrowed;[6] and ancient oratory eddied in shallows until

it found a new course with the new motive of Christian

preaching.

In exorcising the false conception Aristotle removed the

false sophistic emphasis from style. He does not despise,

nor even slight, technic. He finds analysis of sentence

rhythms necessary. But his goal in this, as in his analysis

of figures, is beyond the technical means of securing particular

effects. He does not classify figures for reference;

he seeks in both phrase and cadence the function; and he

discusses neither until he has spent some two-thirds of

his treatise on the function of rhetoric as a whole course

of study. This he finds philosophically necessary. Otherwise

[5]rhetoric cannot be justified; otherwise, he clearly

implies, it is narrowed and degraded. For him rhetoric

is so inextricably moral that it should never be divorced

from subject matter of real significance.

But what subject matter of real significance has oratory

when it is barred from discussion of present policy? Here

appears a strong external cause of the spread of sophistic.

The sophistical trend, already marked, was furthered by

the narrowing of public discussion. Of the three fields[7]

of oratory distinguished by Aristotle, deliberative, forensic,

and occasional, the first was restricted by political

changes. It faded with democracy. So later it faded at

Rome, and still later in other realms. Deliberative oratory

presupposes free discussion and audiences that vote.

The steady increase of government from above administered

by an appointed official class hastened also the

tendency of the second kind of oratory, forensic, to become

technical, the special art of legal pleading. Thus

the only field left free was the third, occasional oratory,

encomium, or panegyric, the commemoration of persons

and days, the address of welcome, the public lecture. A

favorite field even in Plato’s time, it is in any time the

freest field for imaginative and emotional appeal and for

personal triumphs. Thus it was early and assiduously

cultivated by the sophists. Though it opens, on the other

hand, the highest reaches of eloquence, though Isocrates

is more than a sophist and Lincoln’s Gettysburg address

is as far from sophistic as possible, still its becoming the

main field of Greek oratory gave the lead to sophistic.

In such conditions sophistic could control education; and

its control of education reacted upon the conditions to

make a vicious circle. Oratory and the training for it

[6]became preponderantly an art of display; and the rhetoric

finally bequeathed by the ancient schools was sophistic.

In sum, the sophistic tendency, which may be found in

any highly developed literature, was confirmed in Greek

by causes both intrinsic and extrinsic. Becoming a habit,

it became a scheme of education. Against this Plato

represents Socrates in fundamental opposition. Aristotle

does more than oppose it; he establishes constructively

a rhetoric whose persuasion shall be more than personal

appeal and personal triumph. But the rhetoric nobly

and philosophically conceived by him did not succeed in

supplanting the tendency seen at its best in Isocrates.

The conception of Isocrates in Philostratus, though inadequate,

is not wrong essentially.

The siren which stands on the tomb of Isocrates the sophist—its

pose is that of one singing—testifies to the man’s persuasive

charm, which he combined with the laws and habits

of rhetoric. Balances, antitheses, rimes, though he was not

their discoverer but only the skilful user of what had been

discovered already, he put his mind to, and also to amplitude,

rhythm, sentence-movement, beat. These things prepared the

diction of Demosthenes, who was a pupil, indeed, of Isæus,

but a disciple of Isocrates. Philostratus, Lives of the

Sophists, I. 17 (Wright’s translation, page 50, modified).

The Isocratean ideal of eloquence, influential even upon

its critic Dionysius of Halicarnassus, even upon so great

an orator as Cicero,[8] became more sophistic in the practise

of the schools. In the first century of our era sophistic

had won its place, by the second century an eminence

undisputed till Christian preaching returned to the sound

ancient tradition.

[7]

For sophistic is the historic demonstration of what

oratory becomes when it is removed from urgency of

subject matter. Seeking some inspiration for public occasions,

it revives over and over again a dead past. Thus

becoming conventionalized in method, it turns from

cogency of movement to the cultivation of style. Cogency

presupposes a message. It is intellectual ordering for

persuasion, the means toward making men believe and

act. Style, no longer controlled by such urgencies of

subject, tends toward decoration and virtuosity. A

necessary study in any rhetoric, it had been highly cultivated

during Greek democracy; but under monarchy

and Empire it became a preoccupation, almost a monopoly.

Sophistic practically reduces rhetoric to style. The

old lore of investigation (inventio), paralyzed by the compression

of its trunk nerve, has little scope beyond ingenuity.

Organized movement[9] (dispositio), similarly

impaired at the source, tends to be reduced to salience and

variety, or to be supplanted by pattern. Memory becomes

verbal. But style and delivery, becoming the main

reliance, are elaborated into a systematic technic to a

degree almost incredible to-day. In sheer virtuosity the

second sophistic has hardly a parallel in earlier or later

centuries. It is more like the art of Paderewski or Bernhardt

than like that of Demosthenes.

[8]

B. The Second Sophistic[10]

1. Philostratus, The Lives of the Sophists[11]

The Lives of the Sophists by Philostratus derives the

“new” sophistic of his day from the old. New, says he,

it is not. We may call it a second sophistic; but it keeps

an old tradition. Far from apologizing for sophistic, old

or new, Philostratus is proud of it. He sets out to celebrate

it as a great tradition. Gorgias is not defended

from Socratic exposure; he is claimed as a distinguished

ancestor.[12] That rhetoric is not what Aristotle urged,

that it is after all sophistic, Philostratus assumes. Nor

is the assumption merely provincial vanity; it was widespread

and secure. There was no need to vindicate what

was generally accepted. Moreover the facts justify not

only the assumption of Philostratus, but his history.

Though he is not historical in method, his assertion of

continuity from Gorgias down to the platform artists of

his day has been approved by studies really historical, and

affirmed for the fourth century as well. The Lives of the

[9]Sophists, therefore, exhibit the second sophistic as the fixing

of an old tendency in habitual practise and teaching.

During the second, third, and fourth centuries, and

throughout the Roman world, rhetoric meant a sophistic

generally constant. The leanings of particular schools,

such as Stoic Pergamum, were not wide enough to bring

new departures. They were merely shifts of emphasis

within a common doctrine and practise. The cult of

“Atticism” was too artificial to check the general tendency

to “Asianism.”[13] What was learned at Athens

could be practised at Rome; and neither Athens nor Rome

dimmed the glory of Smyrna and Antioch.[14] The schools

of Bordeaux were to become essentially like those of Gaza

and Carthage. The same “Gorgian figures” were learned

by St. Augustine in Latin Africa, by St. Gregory Nazianzen

in the Greek East, and by the pagan Libanius. Greco-Roman

rhetoric was as pervasive as Roman law and

almost as constant.

2. The Character of Sophistic

a. VIRTUOSITY

In estimating this rhetoric, then, little allowance need

be made for place or date.[15] Its main characteristics

were so constant as to stand out clearly. The most obvious

[10]arise from the general aim of virtuosity. This is

the constant assumption of Philostratus. Individual

triumphs were not so much triumphs of individuality as

outstanding exhibitions of skill in working out a pattern.

In method, in composition, there was little difference between

a teacher’s assignments to his amateur pupils and

his own professional orations.[16] Sophistic is largely an

oratory of themes.

(1) Declamatio[17] (μελέτη)

THEMES OF THE SOPHISTS CELEBRATED BY PHILOSTRATUS

Historical or Semi-historical Themes

The Lacedemonians deliberate concerning a wall. I. 20 (70).[18]

(Isæus; so Aristides, II. 9 (220).)

Demosthenes swears that he did not take the bribe.

Should the trophies erected by the Greeks be taken down?

The Athenians should return to their demes after Ægospotami.

Xenophon refuses to survive Socrates.

Solon demands that his laws be rescinded after Pisistratus has

obtained a bodyguard. I. 25 (122-132). (Polemo.)

The Cretans maintain that they have the tomb of Zeus. II. 4

(188). (Antiochus.)

Scythians, return to your nomadic life. II. 5 (194). (Alexander

of Seleucia; so Hippodromus, II. 27 (296).)

The wounded in Sicily implore the Athenians who are retreating

thence to put them to death with their own hands.

Pericles urges them to keep up the war even after the oracle

declares Apollo’s support of the Lacedemonians. (II. 5;

both also of Alexander.)

[11]

Isocrates tries to wean the Athenians from their empire of the

sea.

Callixenus is upbraided for not having granted burial to the

Ten.

Deliberation on affairs in Sicily.[19]

Æschines, when the grain had not come.

Those whose children have been murdered reject a treaty of

alliance. II. 9 (220, seq.) (Aristides.)

Hyperides, when Philip is at Elatea, heeds only the counsels

of Demosthenes. II. 10 (230). (Hadrian of Tyre.)

Islanders sell their children to pay taxes. II. 12 (238). (Pollux.)

The Thebans accuse the Messenians of ingratitude. II. 15

(244). (Ptolemy.)

Callias tries to dissuade the Athenians from burning the dead.

II. 20 (256). (Apollonius of Athens.)

The citizens of Catana.

Demades against revolting from Alexander while he is in India.

II. 27 (296). (Hippodromus.)

Fictitious Themes

The adulterer unmasked. I. 25 (132). (Polemo.)

The instigator of a revolt suppresses it. I. 26 (136). (Secundus.)

The ravished chooses that her ravisher be put to death. II.

4 (188). (Antiochus.)

A tyrant abdicates on condition of immunity. (Ibid.)

The man who fell in love with a statue. II. 18 (250). (Onomarchus.)

The magician who wished to die because he was unable to kill

another magician, an adulterer. II. 27 (292). (Hippodromus.)

Evidently the themes were generally the same as those

of the declamationes celebrated by Seneca.[20] Some of them

were identical. Such subjects give the oratory of the

imperial centuries, both Greek and Latin, the air of athletics,

[12]and make its teaching seem largely gymnastic.

Gregory Nazianzen, indeed, calls the sophists “oratorical

acrobats.”[21] But instead of dismissing sophistic with

so obvious a sarcasm, we may learn something from its

delight in verbal artistry.

For what, then, ultimately do we blame them? For their

absolute emptiness of thought? But who shall say that they

were trying to think, or that they were asked to think?...

a kind of eloquence, and also a system of education, of which

we have not any longer even the notion; for it rested on a

sentiment which has disappeared, the absolute and disinterested

love of speaking well—disinterested not always, indeed, as to

personal advantage, but always as to thought. Who knows

whether thought was for them anything else or anything more

than a simple motif, a theme to be developed, something which

sustained the discourse without imparting to it any value,

something like the libretto of an opera?[22]

Since the oratory of display is still with us, the second

sophistic should be taken to heart as a complete historic

demonstration of what must become of rhetoric without

the urgencies of matter and motive.

Philostratus has no qualms. For him declamatio

(μελέτη), far from being merely a school exercise, is a

form of public speaking on a par with any other. It is

[13]even the form of his sophists. He pays little attention

to any other except encomium, which is also a school

exercise. Reading the past with the eyes of the present,

he finds it in Gorgias,[23] who elaborated “encomia of the

Medic trophies.” “Medics” (Μηδικά), dilations on the

old glories of the Persian wars, were the favorite subjects

of declamatio. This is evident both from their frequent

recurrence and from Lucian’s satire.[24] Scopelian, Philostratus

thinks, was best

in Medics, in the Darius and Xerxes things, I mean; for, to me

at least, he of all the sophists seems to render these best and

to set a tradition of rendering for his successors. I. 21 (84).

Ptolemy of Naucratis, however, was nicknamed Marathon.[25]

The wonder is that the nickname was sufficiently

distinctive.[26]

(2) Improvisation and Memory

The vogue of such subjects does much to explain the

otherwise incredible accounts of improvisation. “Propose

a theme,” the sophist’s challenge which Philostratus

traces back to Gorgias,[27] becomes less startling when we

find that the theme, as well as the treatment, might come

from stock. Even so the readiness and fluency seem

phenomenal and were the great boast. See Mark of

Byzantium recognized by pupils in the school of Polemo.

[14]

Accordingly when Polemo asked for themes to be proposed,

they all turned towards Mark.... Mark, lifting up his

voice and tossing his head, said: “I will both propose and

execute.” Thereupon Polemo ... discoursed at him long

and wonderfully on the spur of the moment; and when he had

declaimed and heard Mark declaim, he was both admired and

admiring. I. 24 (104).

Aristides was exceptional in declining to speak thus; and

Philostratus thinks the less of him.[28] Generally improvisation

was expected as a mark of virtuosity.[29] The locus

classicus, perhaps, of improvisation, the most daring and

phenomenal virtuosity, is ascribed by Eunapius to Prohæresius.

Then from his chair the sophist first delivered a graceful

prelude ... then with the fullest confidence he rose for his

formal discussion. The proconsul was ready to propose a

definition for the theme, but Prohæresius threw back his head

and gazed all round the theater ... and beheld in the farthest

row of the audience, hiding themselves in their cloaks, two

men, veterans in the service of rhetoric, at whose hands he

had received the worst treatment of all, and he cried out: “Ye

gods! There are those honourable and wise men! Proconsul,

order them to propose a theme for me. Then perhaps they

will be convinced that they have behaved impiously.”...

Whereupon, after considering for a short time and consulting

together, they produced the hardest and most disagreeable

theme that they knew of, a vulgar one, moreover, that gave

no opening for the display of fine rhetoric. Prohæresius

glared at them fiercely, and said to the proconsul: “I implore

you to grant me ... to have shorthand writers assigned to

me.”... Then he said: “I shall ask for something even

[15]more difficult to grant ... there must be no applause whatever.”

When the proconsul had given all present an order to

this effect ... Prohæresius began his speech with a flood of

eloquence, rounding every period with a sonorous phrase....

As the speech grew more vehement and the orator soared to

heights which the mind of man could not describe or conceive

of, he passed on to the second part of the speech and completed

the exposition of the theme. But then, suddenly leaping in

the air like one inspired, he abandoned the remaining part,

left it undefended, and turned the flood of his eloquence to

defend the contrary hypothesis. The scribes could hardly

keep pace with him, the audience could hardly endure to remain

silent, while the mighty stream of words flowed on.

Then, turning his face towards the scribes, he said: “Observe

carefully whether I remember all the arguments that I used

earlier.” And without faltering over a single word, he began

to declaim the same speech for the second time. (Wright’s

translation, 493.)

This performance is extraordinary only in degree.

That of Isæus, as reported by Pliny,[30] seems the same in

kind; and so, apparently, are many other recorded triumphs.

Taken together, they reveal strict limits. The

improvisation was mainly of style. It consisted in fluency

of rehandling, of variations upon themes, and in patterns,

so common as to constitute a stock in trade. It permitted

the use over and over again not only of stock examples

and illustrations, but of successful phrases, modulated

periods, even whole descriptions. It was the art of a

technician, not of a composer.[31] Memory, too, thus

trained, was no longer the orator’s command of his material;[32]

it was the actor’s command of words. Though a

[16]sophist might, indeed, be a thinker, he hardly needed to

be for the purposes of his oratory. His fluency was typically

not in seizing and carrying forward ideas and images,

but in readiness to draw upon a store.

(3) Delivery

The character of this oratory is further expressed in

the records of its delivery. Even more than modulation

Philostratus exhibits sonority and force. Polemo’s delivery

was thrilling as an Olympian trumpet.[33] Scopelian

imitated the volume of Nicetes and had the sonority of

Gorgias.[34] Favorinus fascinated even those who did not

understand Greek.[35] The carrying voice spoke in marked

rhythms. Gesture, pushed sometimes to the extent of

acting, was habitually demonstrative. Sitting at first,

the orator might then leap to his feet, smite his thigh,

walk, stamp, sway as a Bacchante. If such theatrical

delivery seems to moderns of the West more violent than

it seemed to its own audiences, it has never been extinct;

and any one familiar with the oratory of display in any

time will recognize the sophist’s heavy frown, his mien of

deep thought, his air of authority.[36] Chaucer’s Pardoner

speaks for the whole sophist line:

I peyne me to han an hauteyn speche.

Canterbury Tales, C. 330.

Such weight and vehemence of delivery, sometimes conceding

a benignant smile, oftener relying on arrogance,[37]

was the bodily expression of the impressiveness (δεινότης)

cultivated no less assiduously in style. The sophist was

[17]over-expressive lest for a moment he should cease to be

impressive. The audience need not be held to any course

of thought; it must not be held too long by any one device

of style; but it must unflaggingly admire. It must be

spellbound. The constant implication of Philostratus

probably echoes the ideal of orator and audience alike:

behold a great speaker!

b. DILATION

Such oratory must be dilated, even inflated. That it

was so in fact any one may satisfy himself who has the

patience. The amplification[38] practised by Cicero and

taught by Quintilian, though in print it may seem over-anxious,

is an oratorical necessity. It is not merely Greek

expansiveness; for it moves also the more stinted Latin.

In any language it must almost always be practised as a

means to oral clearness.[39] But sophistic amplification

has no such warrant. It is often purely decorative. Instead

of marking a stage of progress, it often merely dwells

on a picture, or elaborates a truism, or acts out a mood.

It is there for itself, expecting its own applause. Many

of the figures of speech are devices of dilation; for sophistic

is an art not only of elaboration, but of elaborateness.

(1) Ecphrasis

Without enumerating devices that constitute a large

part of sophistic, we may see the characteristic dilation

at the full in the single form known as ἔκφρασις.[40] An

[18]ecphrasis is a separable decorative description, usually of

a stock subject. “I will draw this for you in words,”

says Himerius,[41] using the formula of introduction, “and

will make your ears serve for eyes.” The natural beauty

of a prospect or of the human body is detailed for admiration,

even oftener the artistic beauty of statue or temple.

The orator turns on, as it were, a storm, a feast, the prospect

of a city. The essentially artificial character of the

ecphrasis is obvious in the favorite exercise of word-painting

a peacock.[42] Apparently a boy could carry this

peacock from school to the platform and continue to use

it with merely verbal variations.

Of course the ecphrasis might rise to a higher level.

So it did often. An accomplished orator might make it

splendid, even really moving. Oratory cannot afford to

neglect the appeal of oral description. None the less the

ecphrasis had two essential vices. First it was extraneous,

separable, detachable, a clear sign that sequence did not

count. Secondly, instead of following the Aristotelian

[19]counsels of specific concrete imagery, it habitually generalized

and rapidly became conventional.

Ecphrasis is no less significant for poetic. A form of

Alexandrianism[43] avoided by Vergil and adopted with

enthusiasm by Ovid, it perverts description because it

frustrates narrative movement. The habit of decorative

dilation in oratory confirmed a decadent habit of literature.[44]

That the habit is decadent even when indulged

with more taste is suggested by certain passages in De

Quincey, in Pater, most clearly perhaps in that English

sophist Laurence Sterne. Among the ecphrases of the

Sentimental Journey is one that he executed upon a theme

taken from the most expert mocker of the sophists,

Lucian,[45] and has made quite typical of the soothing

rhythms and the elegant dilation of sophistic eloquence.

The town of Abdera, notwithstanding Democritus lived

there, trying all the powers of irony and laughter to reclaim

it, was the vilest and most profligate town in all Thrace.

What for poisons, conspiracies, and assassinations, libels,

pasquinades and tumults, there was no going there by day;

’twas worse by night. Now when things were at their worst,

it came to pass that the Andromeda of Euripides being represented

at Abdera, the whole orchestra was delighted with it.

But of all the passages which delighted them, nothing operated

more upon their imaginations than the tender strokes of

nature which the poet had wrought up in that pathetic speech

of Perseus, “O Cupid! prince of gods and men.” Every man,

almost, spoke pure iambics the next day, and talked of nothing

but Perseus’ pathetic address—“O Cupid! prince of gods and

men!” In every street of Abdera, in every house—“O Cupid!

Cupid!” in every mouth, like the natural notes of some sweet

melody, which drop from it whether it will or no, nothing but

[20]“Cupid! Cupid! prince of gods and men!” The fire caught;

and the whole city, like the heart of one man, opened itself to

love. No pharmacopolist could sell one grain of hellebore;

not a single armorer had a heart to forge one instrument of

death. Friendship and Virtue met together and kissed each

other in the street. The golden age returned and hung over

the town of Abdera. Every Abderite took his oaten pipe,

and every Abderitish woman left her purple web, and chastely

sat her down, and listened to the song. “’Twas only in the

power,” says the fragment, “of the god whose empire extended

from heaven to earth, and even to the depths of the

sea, to have done this.”

c. PATTERN

For the composition of the whole speech sophistic

generally had little care. That planned sequence, that

leading on of the mind from point to point, which is the

habit of great orators and the chief means of cogency,

presupposes urgency toward a goal. Sophistic often had

no goal. The audience need be won only to admiration,

not to decision. Easily, therefore, rhetoric came to pay

no more attention to logical movement than poetic to

movement in narrative. Like Alexandrian narrative,

sophistic oratory cares little for onwardness; and its lore

is reduced to prescription for detail.

If Philostratus seems occasionally aware of the value

of planned movement, scrutiny will reveal that he is

thinking not of the order of the whole, but only of sentences.

For instance, the passage praising Isocrates for

his “brilliant composition”[46] specifies his handling of

[21]rhythms; “for thought after thought concludes upon a

balanced period.”

This lack of plan may seem paradoxical in the works of

writers as artistic as the Greek men of letters. So, indeed, it

is; but it is explained by the quite different conception that

the Greeks—at least those of the decadence—have of the

beauty of a discourse. For them the whole value is in the

detail. The perfecting of the whole is secondary; they have

no taste for it. By a sort of deliberate intellectual myopia

they restrict their field of vision to the analysis of a paragraph,

a period, a phrase, even a word. Their esthetic sense,

so to speak, is fragmentary.[47]

As if to mark the lack of individual planning for cogency,

sophistic is commonly composed upon set patterns. No

other body of oratory has so uniformly resigned itself to

forms. The orator could devote his whole attention to

each separate development because its place was predetermined

in a traditional series of topics. The encomium[48]

of a country was expected to deal with its situation,

climate, products, its race, founders, government, its

advancement in learning and literature, its festivals and

its buildings, unless indeed the whole encomium were

based on one of these topics. Similar topics controlled

the praise of a city, a harbor, a bay, an acropolis. The

classification of these as separate forms goes on to enumerate

the speech at an embarkation, a marriage, a birthday,

a festival, etc., as in a complete letter-writer.[49] Similarly

prescribed was the encomium of a person. So pervasive

[22]were its topics that they invaded even written biography.[50]

Philostratus follows them in his account of Herodes Atticus.[51]

Basil, on the other hand, explicitly rejects them

as inept for encomia of Christian martyrs; and his protest

shows at once their prevalence and their typical vice.

The school of God does not recognize the laws of the encomium,

but holds that a mere telling of the martyr’s deeds

is a sufficient praise for the saints and sufficient inspiration

for those who are struggling towards virtue. For it is the

fixed habit of encomia to search out the history of the native

city, to find out the family exploits, and to relate the education

of the subject of the encomium, but it is our custom to

pass over in silence such details and to compose the encomium

of each martyr from those facts which have a bearing

on his martyrdom. How could I be an object of more reverence

or be more illustrious from the fact that my native city

once upon a time endured great and heavy battles and after

routing her enemies erected famous trophies? What if she

is so happily located that in summer and winter her climate

is pleasant? If she is the mother of heroes and is capable

of supporting cattle, what gain are these to me? In her herds

of horses she surpasses all lands under the sun. How may

these facts improve us in manly virtue? If we talk about the

peaks of mountains near, how they out-top the clouds and

reach the farthest stretches of the air, shall we deceive ourselves

into thinking that drawing praise from these facts we

give praise to men? Of all things it is most absurd that when

the just despise the whole world, we celebrate their praises from

those things which they contemned.[52]

Such composing upon a pattern is legitimately a school

exercise. Its use in elementary education is not confined

[23]to sophistic. What is sophistic is its extent and its prescriptiveness,

still more its extension from school into

adult and professional practise. How far the oratory of

the imperial centuries was controlled by fixed topics becomes

startingly evident in its conformity to the rules

set forth by the manuals of elementary exercises.[53] Theon’s

of uncertain date may have been superseded[54] by that

of Aphthonius in the fourth century, which at any rate

had a long life.[55] But the pattern is most concisely shown

in the second century by Hermogenes,[56] whose work is

typical of them all. There some of the most characteristic

habits of form in sophistic oratory are seen as prolongations

of school exercises.

THE ELEMENTARY EXERCISES (προγυμνάσματα) OF HERMOGENES[57]

Myth (Fable)

Myth is the approved thing to set first before the young,

because it can lead their minds into better measures.

Myths appear to have been used also by the ancients, Hesiod

telling that of the nightingale, Archilochus that of the fox.

From their inventors myths are named Cyprian or Libyan

or Sybaritic; but all alike are called Æsopic, because Æsop

used myths for his dialogues.

[24]

The description of a myth is traditionally something like

this. It may, they say, be fictitious, but thoroughly practical

for some contingency of actual life. Moreover it should be

plausible. How may it be plausible? By our assigning to

the characters actions that befit them. For example, if the

contention be about beauty, let this be posed as a peacock;

if some one is to be represented as wise, there let us pose a

fox; if imitators of the actions of men, monkeys.

Myths are sometimes to be expanded, sometimes to be told

concisely. How? By now telling in bare narrative, and now

feigning the words of the given characters. For example,

“the monkeys in council deliberated on the necessity of

settling in houses. When they had made up their minds to

this end and were about to set to work, an old monkey restrained

them, saying that they would more easily be captured

if they were caught within enclosures.” Thus if you are concise;

but if you wish to expand, proceed in this way. “The

monkeys in council deliberated on the founding of a city;

and one coming forward made a speech to the effect that

they too must have a city. ‘For see,’ said he, ‘how fortunate

in this regard are men. Not only does each of them have a

house, but all going up together to public meeting or theater

delight their souls with all manner of things to see and hear.’”

Go on thus, dwelling on the incidents and saying that the

decree was formally passed; and devise a speech for the old

monkey. So much for this.

The style of recital, they say, should be far from periods and

near to pleasantness. The moral to be derived from the myth

is sometimes put first, sometimes last. Orators[58] too appear

to have used myth instead of example.

[25]

Tale

A tale, they say, is the setting forth of something that has

happened or of something as if it had happened. Sometimes,

however, authorities set the chria instead of this.

A tale differs from a story as a poem from an extended

poetical work. For a poem or a tale is about one thing, a

poetical work or a story about several. Thus a poetical work

is the Iliad, for example, or the Odyssey; but a poem is (one

of the component parts, such as) the making of the shield,

the visit to the shades, or the slaying of the suitors. And

again, a story is the history of Herodotus or the composition

of Thucydides; a tale is the incident of Arion or that of Alcmæon.

The forms of the tale are said to be four: the mythical; the

fictitious, which is also called the dramatic, as those of the

tragic poets; the historical; and the political or personal. But

for the present we consider the last.

The modes of tales are five: direct declarative, indirect

declarative, interrogative, enumerative, comparative. Direct

declarative is as follows: “Medea was the daughter of Æetes.

She betrayed the golden fleece”; and it is called direct because

the whole discourse, or the greater part, keeps the nominative

case. Indirect declarative is as follows: “The story runs

that Medea, daughter of Æetes, was enamored of Jason,”

and so on; and it is called indirect because it uses the other

cases. The interrogative is this mode: “What terrible thing

did not Medea do? Was she not enamored of Jason, and did

she not betray the golden fleece and kill her brother

Absyrtus?” and so on. The enumerative mode is as follows:

“Medea, daughter of Æetes, was enamored of Jason, betrayed

the golden fleece, slew her brother Absyrtus,” and so on. The

comparative is as follows: “Medea, daughter of Æetes, instead

of ruling her spirit, was enamored; instead of guarding

the golden fleece, betrayed it; instead of saving her brother

Absyrtus, slew him.” The direct mode is suited to stories,

[26]as being clearer; the indirect, rather to trials; the interrogative

to cross-questioning; the enumerative, to perorations, as rousing

emotion.

Chria

A chria[59] is a concise exposition of some memorable saying

or deed, generally for good counsel.

Some chriæ are of words, others of deeds, still others of

both: of words, i.e., essentially sayings, as “Plato said that

the Muses dwell in the souls of the fit”; of deeds, i.e., essentially

doings, as “Diogenes, seeing an ill-bred youth, smote

his tutor, saying ‘why did you teach him thus?’”

A chria differs from a memoir mainly in scope; for some

memoirs may run to considerable length, but a chria must

be concise. It differs from a proverb in that the latter is a

bald declaration, whereas a chria is often (developed) by question

and answer; and again in that a chria may be based upon

deeds, whereas a proverb is based only upon words; and

again in that a chria introduces the person who did or said,

whereas the proverb has no reference to a person.

Chriæ have been distinguished, mainly by the ancients, as

declarative, interrogative, and investigative.

But now let us come to the point, that is the actual working

out. Let this working out be as follows: first, brief encomium

of the sayer or doer; then paraphrase of the chria itself; then

proof or explanation. For example, Isocrates said that the

root of education is bitter, but its fruit sweet: (1) encomium,

“Isocrates was wise,” and you will slightly develop this topic;

(2) chria, “said, etc.,” and you will not leave this bare, but

develop the significance; (3) proof, (a) direct, “the greatest

affairs are usually established through toil, and, once established,

bring happiness”; (b) by contrast, “those affairs which

succeed by chance require no toil and their conclusion brings

no happiness; quite the contrary with things that demand our

[27]zeal”; (c) by illustration, “as the farmers who toil ought to

reap the fruit, so with speeches”; (d) by example, “Demosthenes,

who shut himself up in his room and labored much,

finally reaped his fruit, crowns and public proclamations.”

(e) You may also cite authority, as “Hesiod says, ‘Before

virtue the gods have put sweat’; and another poet says, ‘The

gods sell all good things for labor.’” (4) Last you will put an

exhortation to follow what was said or done.

So much for now; fuller instructions you will learn later.

Proverb

A proverb is a summary saying, in a statement of general

application, dissuading from something or persuading toward

something, or showing what is the nature of each: dissuading,

as in that line “a counsellor should not sleep all night”; persuading,

as in the lines “he who flees poverty, Cyrnus, must

cast himself upon the monster-haunted deep and down steep

crags.” Or it does neither of these, but makes a declaration

concerning the nature of the thing: “Faring well undeservedly

is for the unintelligent the beginning of thinking ill.”

Again, some proverbs are true, others plausible; some simple,

others compound, others hyperbolic:

(1) true, such as “no one can find a life without pain”;

(2) plausible, such as “never have I asked what manner of

man takes pleasure in bad company, knowing that birds

of a feather flock together”;

(3) simple, such as “wealth may make men even benevolent”;

(4) compound, such as “no good comes of many rulers; let

there be one”;

(5) hyperbolic, such as “earth breeds nothing feebler than

man.”

The working out is similar to that of the chria; for it proceeds

by (1) brief encomium of him who made the saying, as

in the chria; (2) direct exposition; (3) proof; (4) contrast; (5)

enthymeme; (6) illustration; (7) example; (8) authority. Let

the proverb be, for example, “a counsellor should not sleep all

[28]night.” (1) You will briefly praise the speaker. Then to (2)

direct exposition, i.e., to paraphrase of the proverb, as “it

befits not a man proved in counsels to sleep through the whole

night”; (3) proof, “always through pondering is one a leader,

but sleep takes away counsel”; (4) contrast, “as a private

citizen differs from a king, so sleep from wakefulness”; (5)

“how, then, might it be taken? if there is nothing startling

in a private citizen’s sleeping all night, plainly it befits a king

to ponder wakefully”; (6) illustration, “as helmsmen are incessantly

wakeful for the common safety, so should chieftains

be”; (7) example, “Hector, not sleeping at night, but pondering,

sent Dolon to the ships to reconnoiter.” (8) The last topic

is the one from authority. Let the conclusion be hortatory.

Refutation and Confirmation

Destructive analysis is the overturning of the thing cited;

constructive analysis, on the contrary, its confirmation.

Things fictitious, such as myths, are open to neither destruction

nor construction; destruction and construction apply

only to things that offer argument on either side.

Destructive analysis proceeds by alleging that the thing is

(1) obscure, (2) incredible, (3) impossible, (4) inconsistent or,

as it is called, contrary, (5) unfitting, (6) inexpedient: (1) obscure,

as “in the case of Narcissus the time is obscure”; (2)

incredible, as “it is incredible that Arion in the midst of his

ills was willing to sing”; (3) impossible, “it is impossible that

Arion was saved on a dolphin”; (4) inconsistent or contrary,

“quite opposite to preserving popular government is wishing

to destroy it”; (5) unfitting, “it was unfitting for Apollo,

being a god, to love a mortal woman”; (6) inexpedient, when

we say that it is of no use to hear this.

Confirmation proceeds by the opposites of these.

Commonplace

The so-called commonplace is the amplification of a thing

admitted, of demonstrations already made. For in this we

[29]are no longer investigating whether so-and-so was a robber

of temples, whether such-another was a chieftain, but how

we shall amplify the demonstrated fact. It is called commonplace

because it is applicable to every temple-robber and to

every chieftain. The procedure must be as follows: (1) analysis

of the contrary, (2) the deed itself, (3) comparison, (4)

proverb, (5) defamatory surmise of the past life (of the accused)

from the present, (6) repudiation of pity by the so-called final

considerations and by a sketch of the deed itself.

Introductions will not be merely within the commonplace,

but will be maintained up to it. For instance, if the commonplace

be about a temple-robber, the introduction, not in sense

but in type, may be as follows: “All evil-doers, honorable

judges, should be hated, but especially those whose audacity

is directed toward the gods”; or again, “If you wish to deprave

other men, let this one go; if not, punish him”; or again, “To

outward seeming the only one on trial here is the accused, but

in truth you judges, too; for to be false to one’s oath of office

may be more criminal than transgression.”

Then, before proceeding to the deed itself, (1) discuss its

contrary; e.g., “Our laws have provided for the worship of

the gods, have reared altars and adorned them with votive

offerings, have honored the gods with sacrifices, festal assemblies,

processions.” Then the application to the indictment.

“Naturally, for the favor of the gods preserves cities; and

without this they must be destroyed.” (2) Now proceed to

the case in hand. “These things being so, what has this man

dared?” and tell what he has done, not as explaining it, but

as heightening. “He has defiled the whole city, both its public

interests and its private; and we must fear lest our crops fail;

we must fear lest we be worsted by our enemies,” etc. (3)

Next go on to comparison. “He is more dangerous than

murderers; for the difference is in the object of attack. They

have presumed against human life; he has outraged the gods.

He is like despots, not like them all, but like the most dangerous.

For in them it appears most shocking that they lay

[30]hands on what has been dedicated to the gods.” And you

will bring into the denunciation comparisons with the lesser,

since they are destructive. “Is it not shocking to punish the

thief, but not the temple-robber?” (4, 5 above.) You may

draw defamation of the rest of his life from his present crime.

“Beginning with small offenses, he went on to this one last,

so that you have before you in the same person a thief, a

housebreaker, and an adulterer” (5, 4 above). You may

cite the proverb in accordance with which he came to this

pass, “Unwilling to work in the fields, he wished to get money

by such means”; and, if you are denouncing a homicide, (you

may tell) also the consequences, “a wife made widow, children

orphans.” (6) Use also the repudiation of pity. Now you

will repudiate pity by the so-called final considerations of

equity, justice, expediency, possibility, and propriety, and by

description of the crime. “Look not on him as he weeps now,

but on him as he despises the gods, as he approaches the

shrine, as he forces the doors, as he lays hands on the votive

offerings.” And conclude upon exhortation. “What are you

about to do? what to decide concerning that which has been

already judged?” So much for the present; the ampler

method you will know later.

Encomium

Encomium is the setting forth of the good qualities that

belong to some one in general or in particular: in general, as

encomium of man; in particular, as encomium of Socrates.

We make encomia also of things, such as justice; and of

animals without reason, such as the horse; and even of plants,

mountains, and rivers. It has been called encomium, they

say, from poets’ singing the hymns of the gods in villages

long ago; and passes also used to be called villages.

Encomium differs from praise (in general) in that the latter

may be brief, as “Socrates was wise,” whereas encomium is

developed at some length. Observe too that censure is classified

with encomia, either because the latter may be euphemistic

[31]or because both are developed by the same commonplaces.

In what, then, does the encomium differ from the commonplace?

For in some cases the two seem very much alike. The

difference, they say, appears in the end, in the issue. For

whereas in the commonplace the aim is to receive a reward,

encomium has no other (end) than the witness to virtue.

Subjects for encomia are: a race, as the Greek; a city, as

Athens; a family, as the Alcmæonidæ. You will say[60] what

marvelous things befell at the birth, as dreams or signs or the

like. Next, the nurture, as, in the case of Achilles, that he

was reared on lions’ marrow and by Chiron. Then the training,

[32]how he was trained and how educated. Not only so, but

the nature of soul and body will be set forth, and of each under

heads: for the body, beauty, stature, agility, might; for the

soul, justice, self-control, wisdom, manliness. Next his pursuits,

what sort of life he pursued, that of philosopher, orator,

or soldier, and most properly his deeds, for deeds come under

the head of pursuits. For example, if he chose the life of a

soldier, what in this did he achieve? Then external resources,

such as kin, friends, possessions, household, fortune, etc.

Then from the (topic) time, how long he lived, much or little;

for either gives rise to encomia. A long-lived man you will

praise on this score; a short-lived, on the score of his not sharing

those diseases which come from age. Then, too, from the

manner of his end, as that he died fighting for his fatherland,

and, if there were anything extraordinary under that head,

as in the case of Callimachus that even in death he stood.

You will draw praise also from the one who slew him, as that

Achilles died at the hands of the god Apollo. You will describe

also what was done after his end, whether funeral games

were ordained in his honor, as in the case of Patroclus, whether

there was an oracle concerning his bones, as in the case of

Orestes, whether his children were famous, as Neoptolemus.

But the greatest opportunity in encomia is through comparisons,

which you will draw as the occasion may suggest.

Similarly also living things without speech, so far as they

permit. You will draw your encomia from the place in which

the thing lives; and in addition to the country of its birth you

will tell to which of the gods it is dedicated, as the owl to

Athena, the horse to Poseidon. In like manner also you will

tell its nurture, the nature of soul and body, its deeds and their

use, the length of its life; and you will use throughout such

comparisons as fall in with these topics.

Encomia of things done you will draw from their inventors,

as the things of the chase from Artemis and Apollo; from those

who practised them, as heroes. But the best procedure for

such encomia is to consider those who pursue them, of what

[33]sort these are in soul and body, e.g., hunters as manly, courageous,

more alert in intelligence, physically vigorous. Finally

you will observe that we must make encomia of the gods;

and it is to be borne in mind that such encomia must be called

hymns.[61]

Furthermore plants similarly, each from the topics of its

habitat, of the god to which it is dedicated, as the olive to

Athena, of its nurture, as how it is grown. If it needs much

care, you will marvel at this; if little, at that. You will tell

concerning its body, its rapid growth, its beauty, and whether

it is ever-blooming, as the olive. Then its usefulness, on which

you will dwell most. Comparisons you will lay hold of everywhere.

Furthermore encomium of a city you may undertake from

these topics without difficulty. For you will tell of its race

that its citizens were autochthonous, and concerning its nurture

that they were nourished by the gods, and concerning its

education that they were educated by the gods. And you will

expound, as in the case of a man, of what sort the city is in

its manners and institutions, and what its pursuits and accomplishments.

Comparison

Comparison has been included both under commonplace

as a means of our amplifying misdeeds, and also under

encomium as a means of amplifying good deeds, and finally

has been included as having the same force in censure. But

since some (authors) of no small reputation have made it an

exercise by itself, we must speak of it briefly. It proceeds,

then, by the encomiastic topics; for we compare city with

city as to the men who came from them, race with race, nurture

with nurture, pursuits, affairs, external relations, and the

manner of death and what follows. Likewise if you compare

plants, you will set over against one another the gods who give

them, the places in which they grow, the cultivation, the use

[34]of their fruits, etc. Likewise also if you compare things done,

you will tell who first undertook them, and will compare

with one another those who pursued them as to qualities of

soul and body. Let the same principle be accepted for all.

Now sometimes we draw our comparisons by equality, showing

the things which we compare as equal either in all respects

or in several; sometimes we put the one ahead, praising also

the other to which we prefer it; sometimes we blame the one

utterly and praise the other, as in a comparison of justice and

wealth. There is even comparison with the better, where

the task is to show the less equal to the greater, as in a comparison

of Heracles with Odysseus. But such comparison demands

a powerful orator and a vivid style; and the working

out always needs vivacity because of the need of making the

transitions swift.

Characterization (ΗΘΟΠΟΙΙΑ)[62]

Characterization is imitation of the character of a person

assigned, e.g., what words Andromache might say to Hector.

(The exercise is called) prosopopœia when we put the person

into the scene, as Elenchus in Menander, and as in Aristides

the sea is imagined to be addressing the Athenians. The difference

is plain; for in the one case we invent words for a

person really there, and in the other we invent also a person

who was not there. They call it image-making (εἰδωλοποιία)

when we suit words to the dead, as Aristides in the speech

against Plato in behalf of the Four; for he suited words to the

companions of Themistocles.

Characterizations are of definite persons and of indefinite;

of indefinite, e.g., what words a man might say to his family

when he was about to go away; of definite, e.g., what words

Achilles might say to Deidamia when he was about to go forth

to war. Characterizations are single when a man is supposed

to be making a speech by himself, double when he has an

[35]interlocutor: by himself, e.g., what a general might say on returning

from a victory; to others, e.g., what a general might

say to his army after a victory.

Always keep the distinctive traits proper to the assigned

persons and occasions; for the speech of youth is not that of

age, nor the speech of joy that of grief. Some characterizations

are of the habit of mind, others of the mood, others a combination

of the two: (1) of the habit, in which the dominant

throughout is this habit, e.g., what a farmer would say on

first seeing a ship; (2) of the mood, in which the dominant

throughout is the feeling, e.g., what Andromache might say

to Hector; (3) combined, in which character and emotion

meet, e.g., what Achilles might say to Patroclus—emotion

at the slaughter of Patroclus, character in his plan for the

war.

The working out proceeds according to the three times.

Begin with the present because it is hard; then revert to the

past because it has had much happiness; then make your

transition to the future because what is to happen is much

more impressive. Let the figures and the diction conform to

the persons assigned.

Ecphrasis[63]

An ecphrasis is an account in detail, visible, as they say,

bringing before one’s eyes what is to be shown. Ecphrases

are of persons, actions, times, places, seasons, and many other

things: of persons, e.g., Homer’s “crooked was he and halt of

one foot”; of actions, e.g., a description of a battle by land

or sea; of times, e.g., of peace or of war; of places, e.g., of

harbors, sea-shores, cities; of seasons, e.g., of spring or summer,

or of a festal occasion. And ecphrasis may combine

these, as in Thucydides the battle by night; for night is a

time and battle is an action.

Ecphrasis of actions will proceed from what went before,

from what happened at the time, and from what followed.

[36]Thus if we make an ecphrasis on war, first we shall tell what

happened before the war, the levy, the expenditures, the fears;

then the engagements, the slaughter, the deaths; then the

monument of victory; then the pæans of the victors and, of

the others, the tears, the slavery. Ecphrases of places, seasons,

or persons will draw also from narrative and from the beautiful,