Title: Lalla Rookh

An Oriental romance

Author: Thomas Moore

Illustrator: T. Sulman

John Tenniel

Release date: September 2, 2025 [eBook #76794]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Longman, Green, Longman, & Roberts, 1861

Credits: Aaron Adrignola, Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

| LALLA ROOKH. | |

| Illuminated Title-page. | |

| [From several ancient MSS. in the Library of the East India House.] | |

| PAGE | |

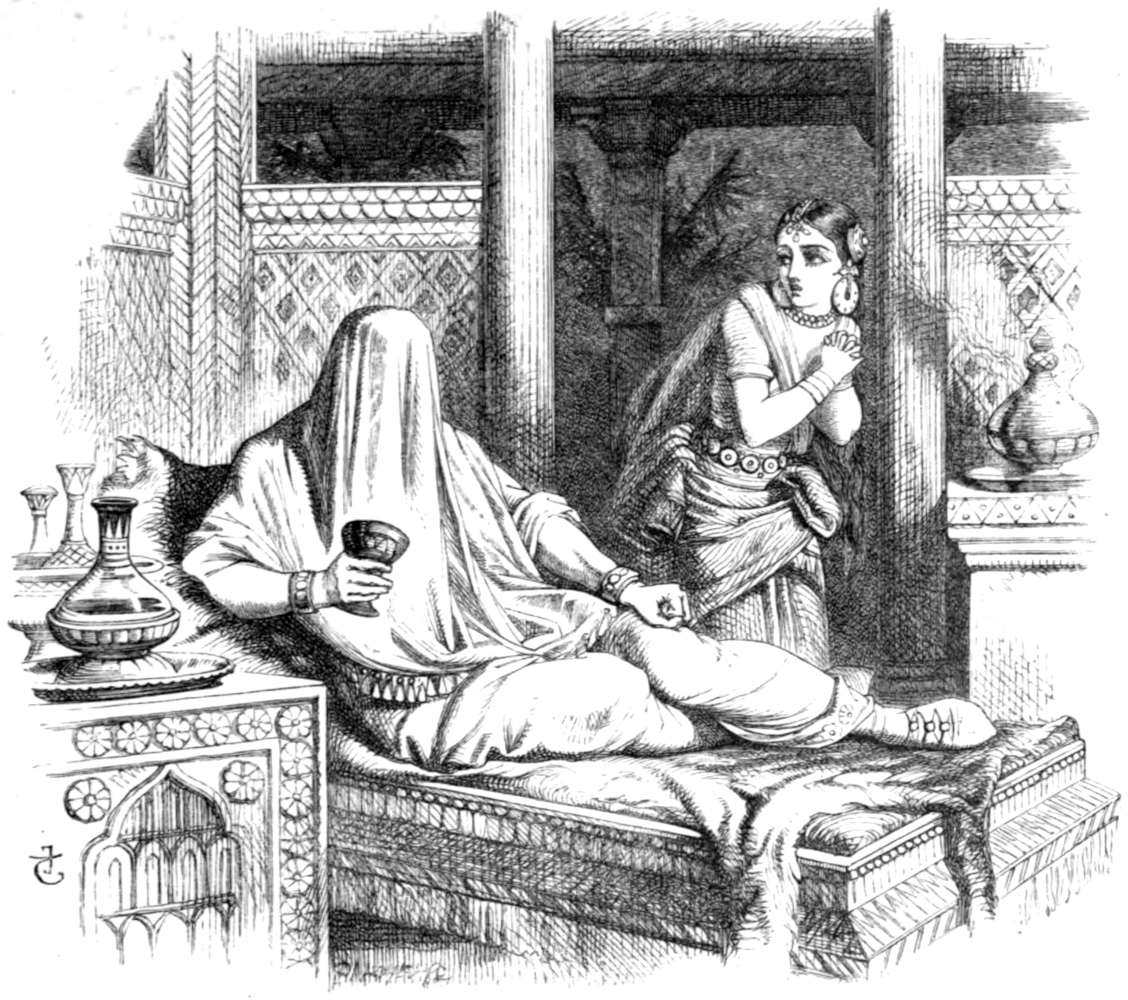

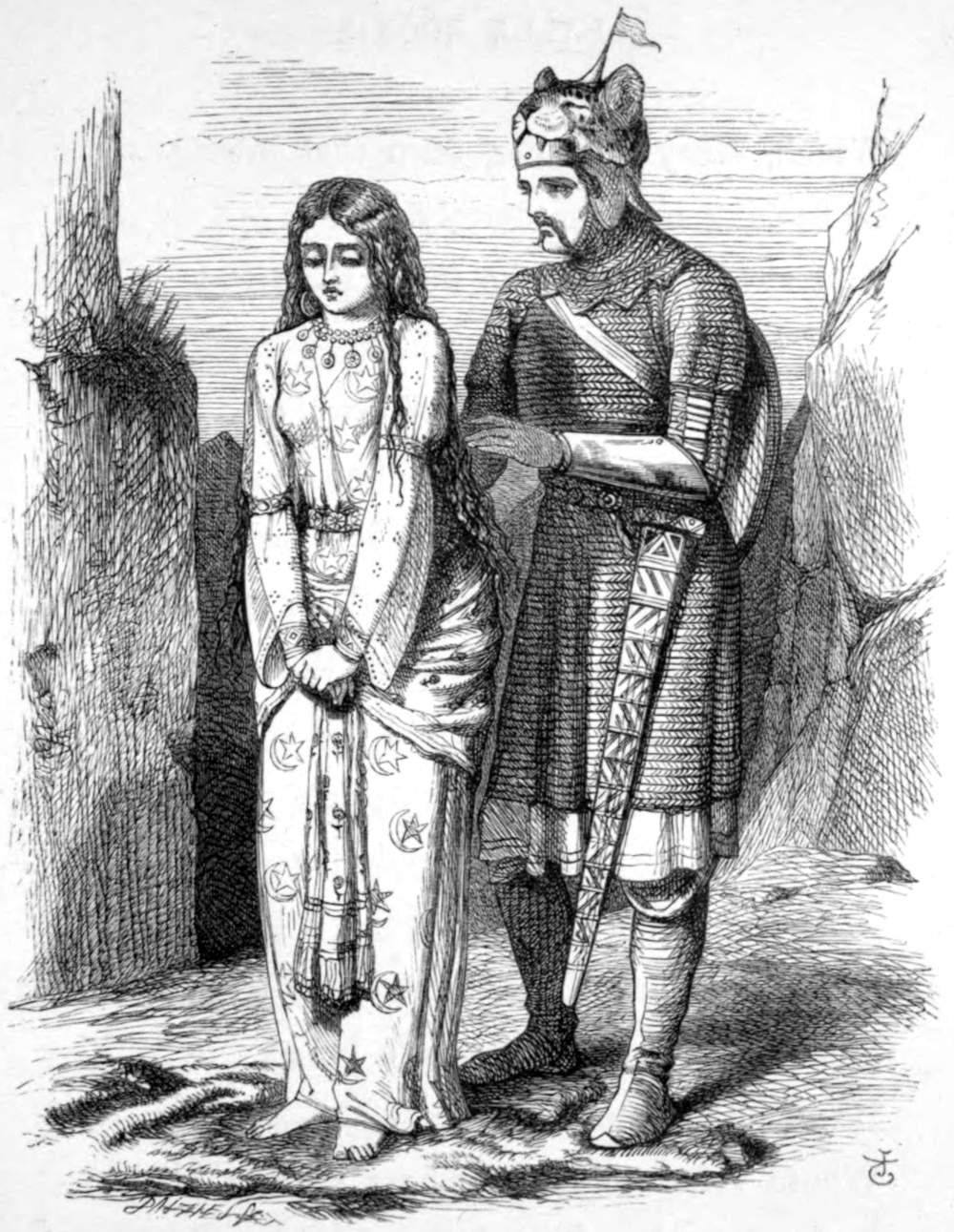

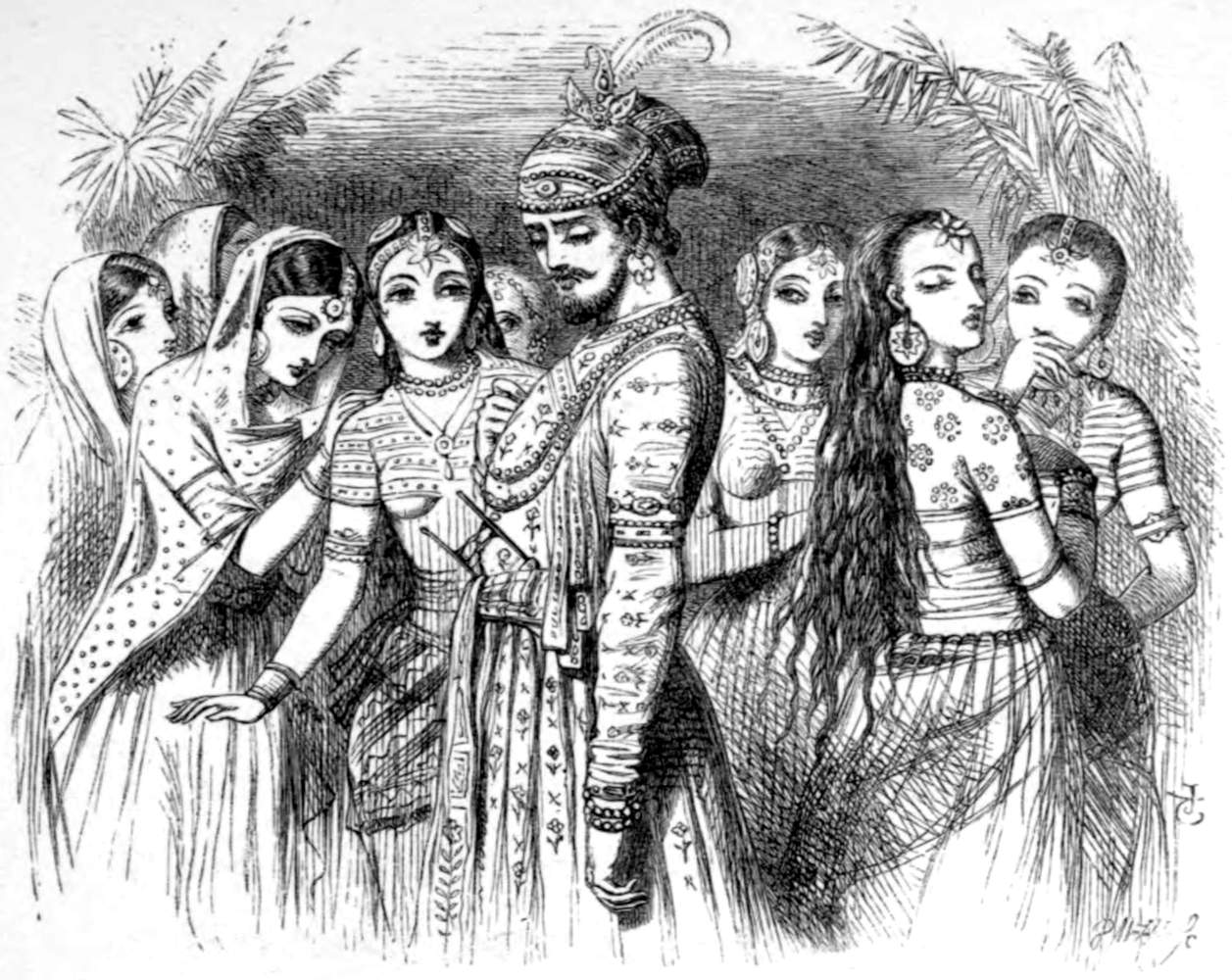

| He was a youth about Lalla Rookh’s own age. | 1 |

| That Veiled Prophet of Khorassan | 8 |

| THE VEILED PROPHET OF KHORASSAN. | |

| Ornamental Title-page | 9 |

| [Principally from a beautiful MS. in the British Museum.] | |

| There on that throne, to which the blind belief | |

| Of millions rais’d him, sat the Prophet-Chief. | 11 |

| All, all are there;—each Land its flower hath given, | |

| To form that fair young Nursery for Heaven! | 14 |

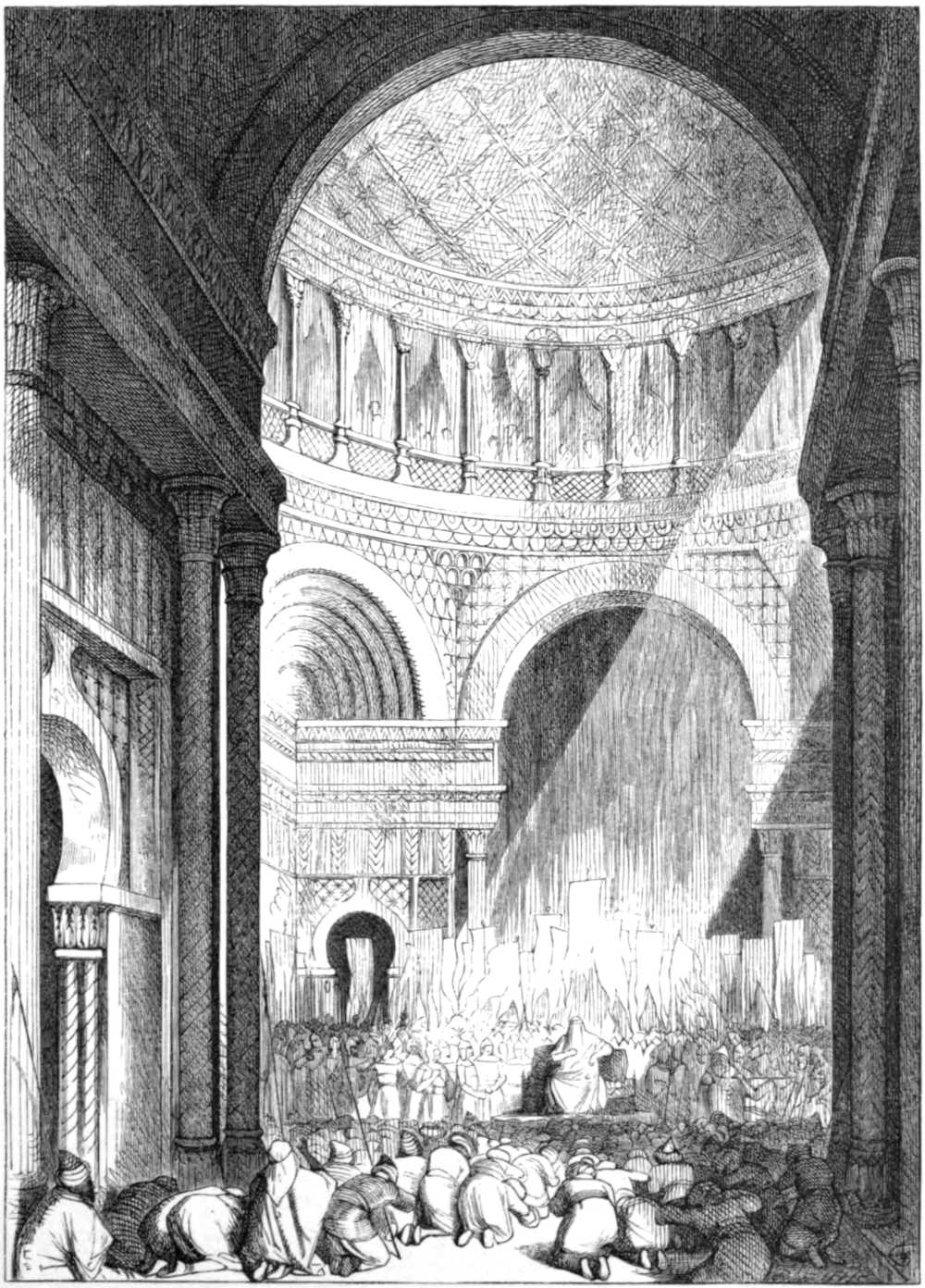

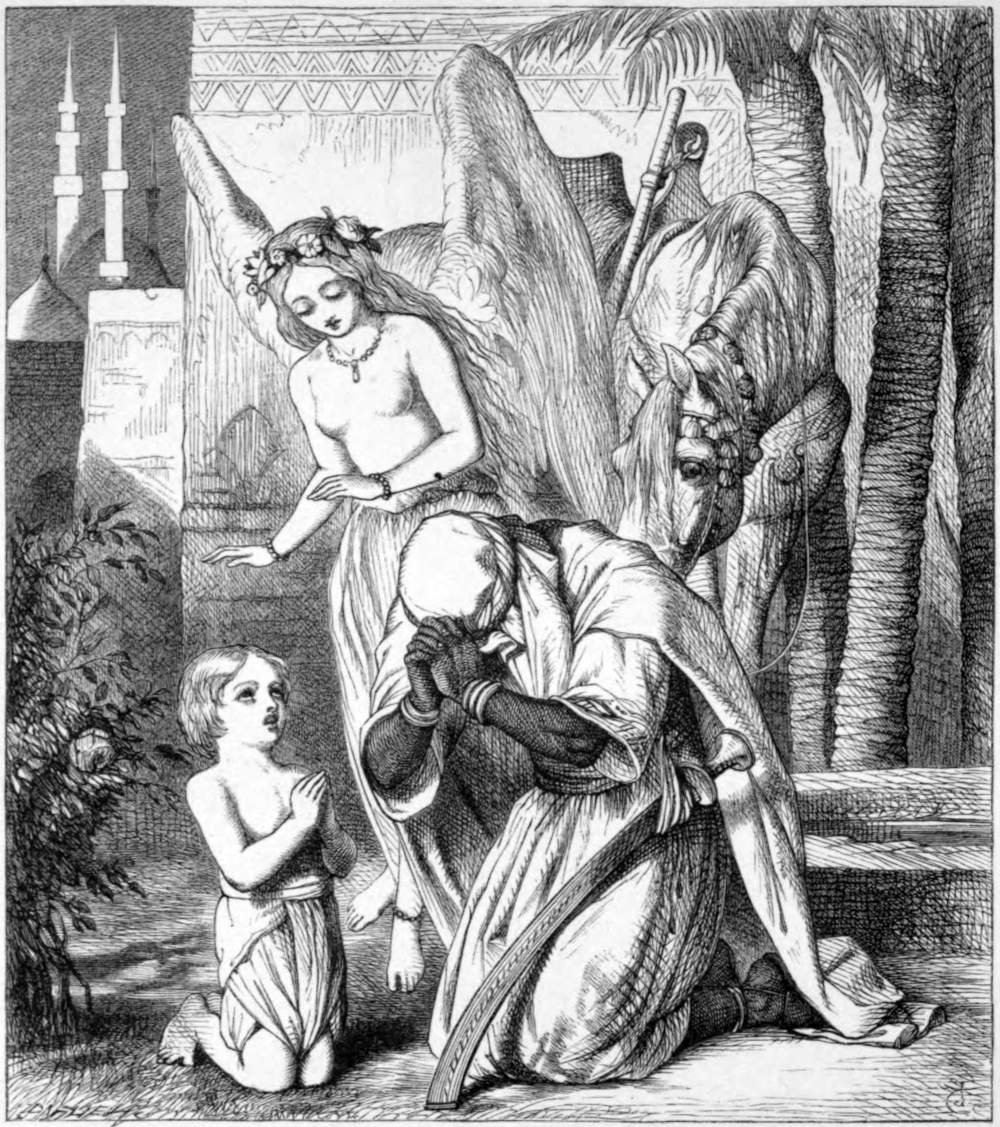

| Believes the form, to which he bends his knee, | |

| Some pure, redeeming angel, sent to free. | 17 |

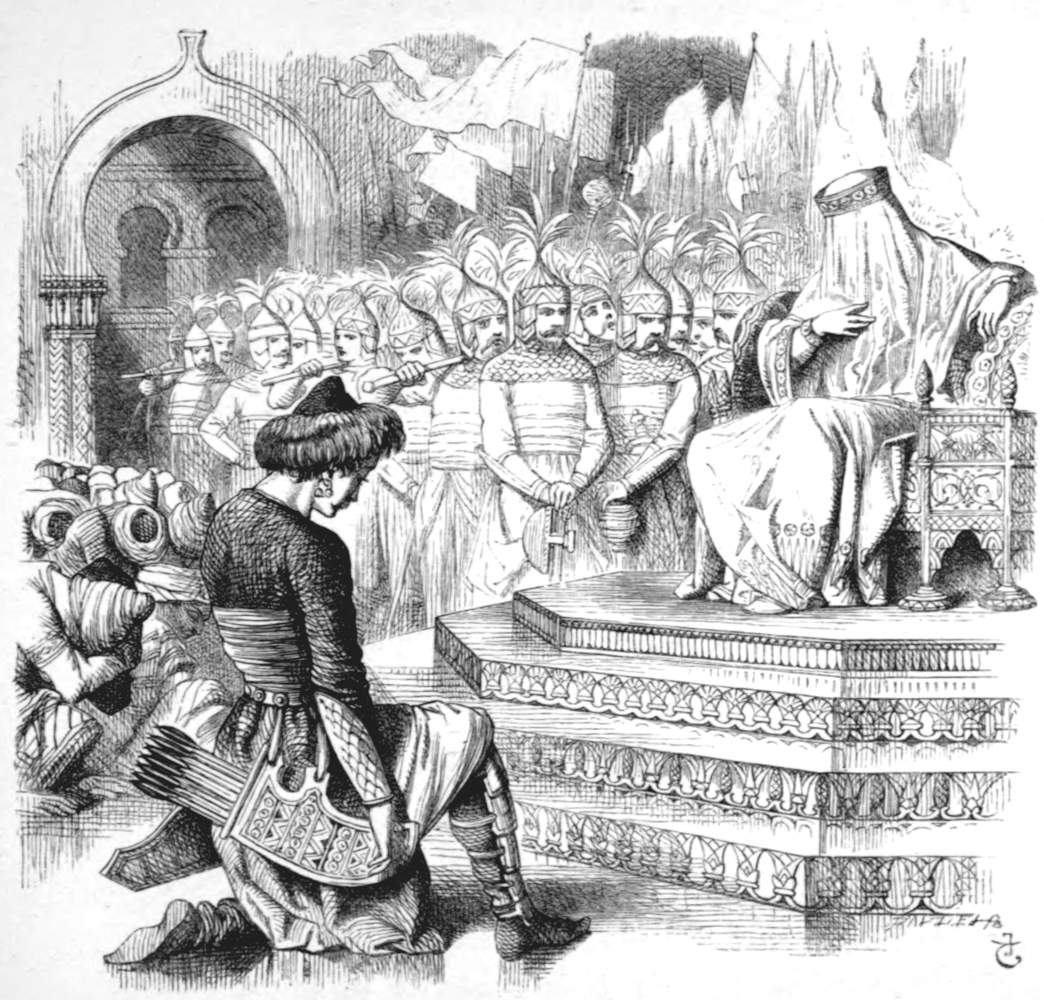

| She saw that youth, too well, too dearly known, | |

| Silently kneeling at the Prophet’s throne. | 21 |

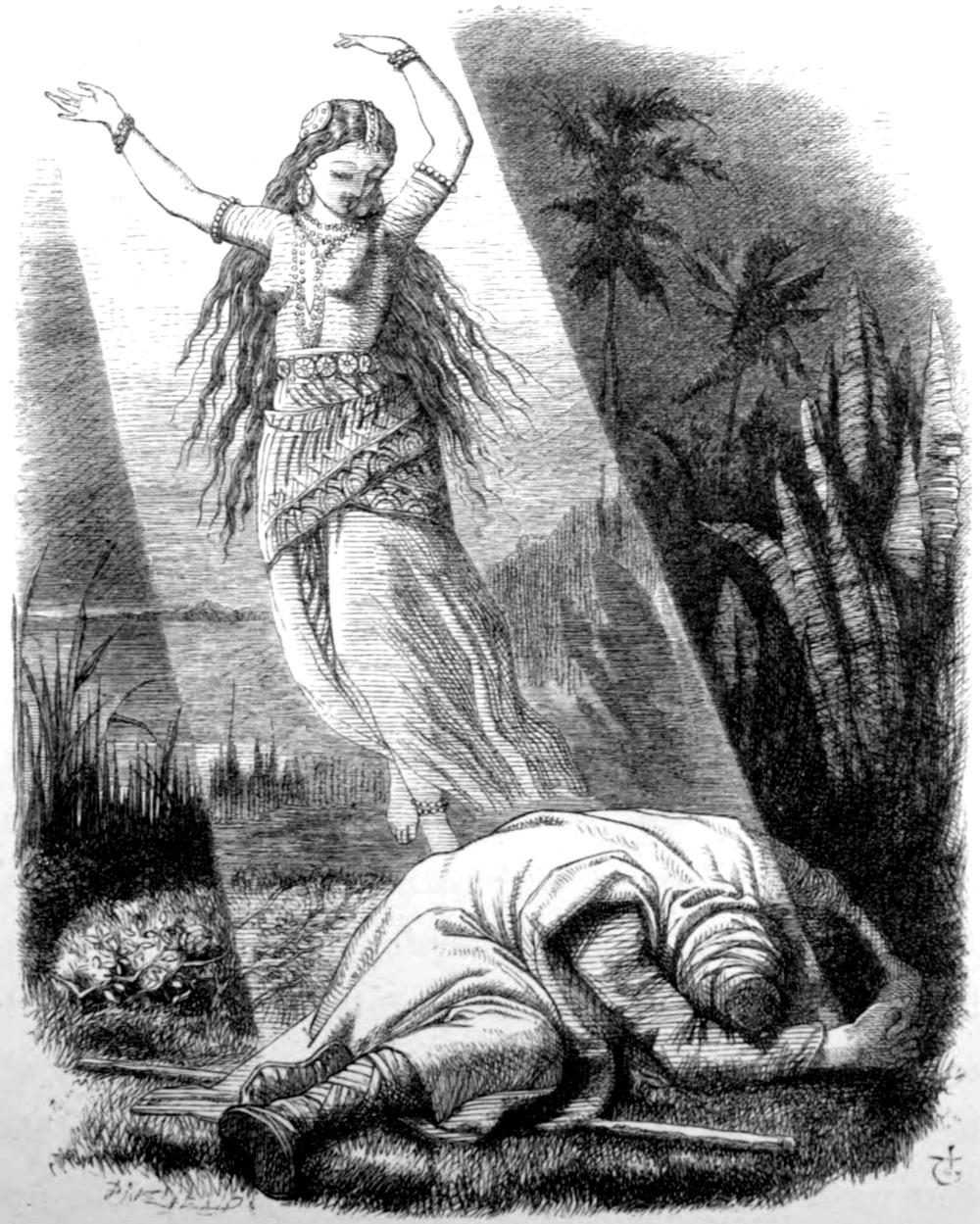

| All fire at once the madd’ning zeal she caught;— | |

| Elect of Paradise! blest, rapturous thought! | 25 |

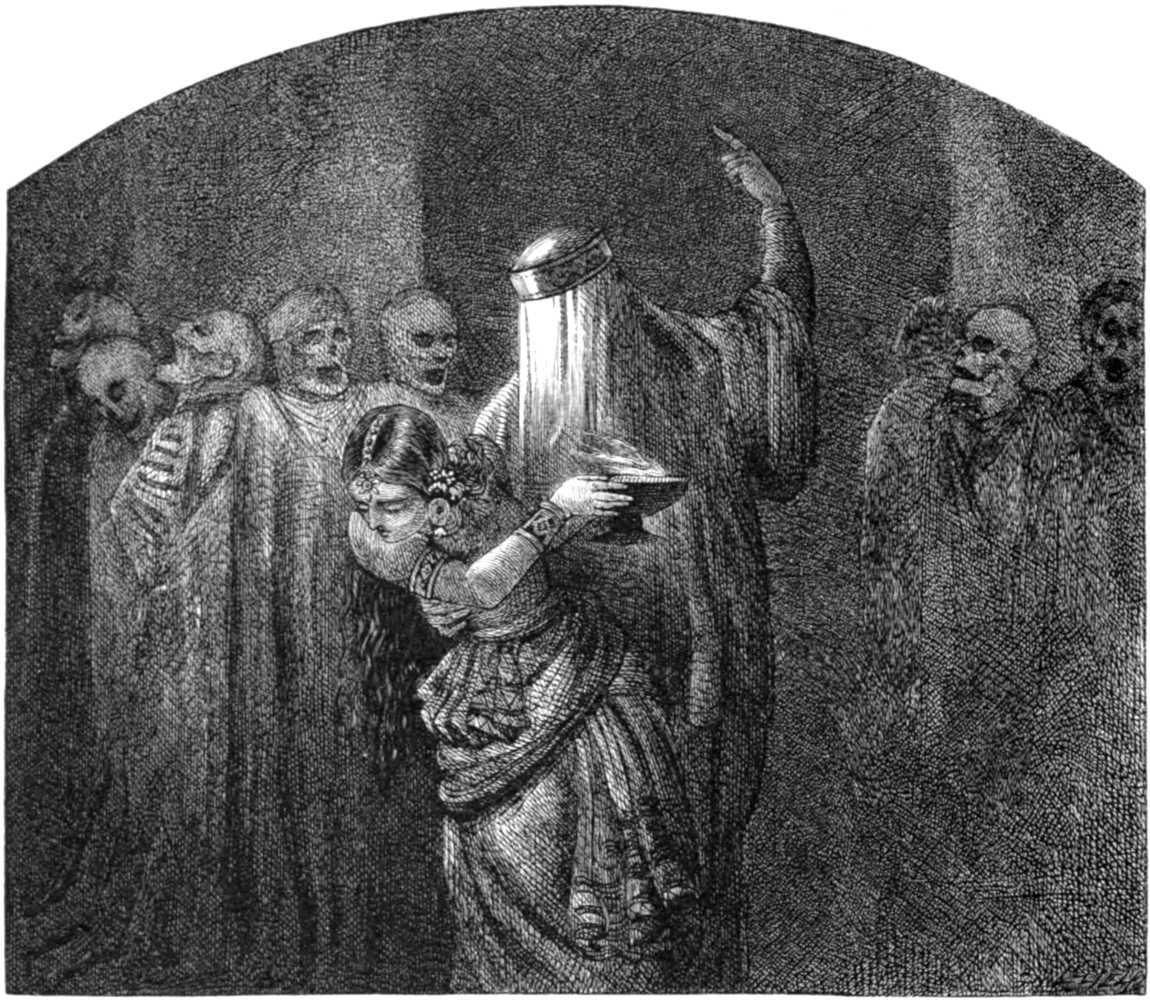

| She swore, and the wide charnel echoed, “Never, never!” | 28 |

| At length, with fiendish laugh, like that which broke | |

| From Eblis at the Fall of Man, he spoke. | 35 |

| “Such the refin’d enchantress that must be | |

| This hero’s vanquisher,—and thou art she!” | 41 |

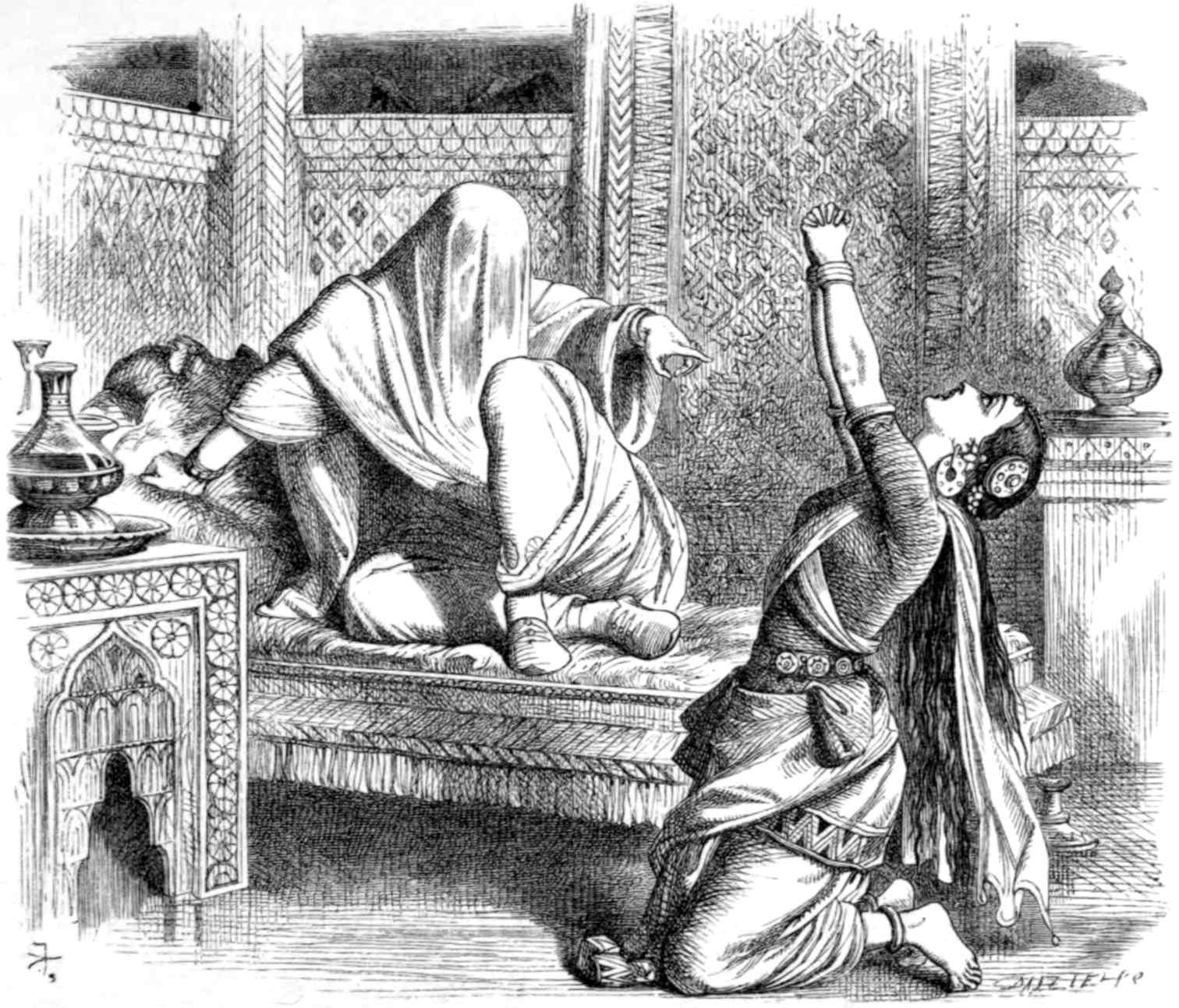

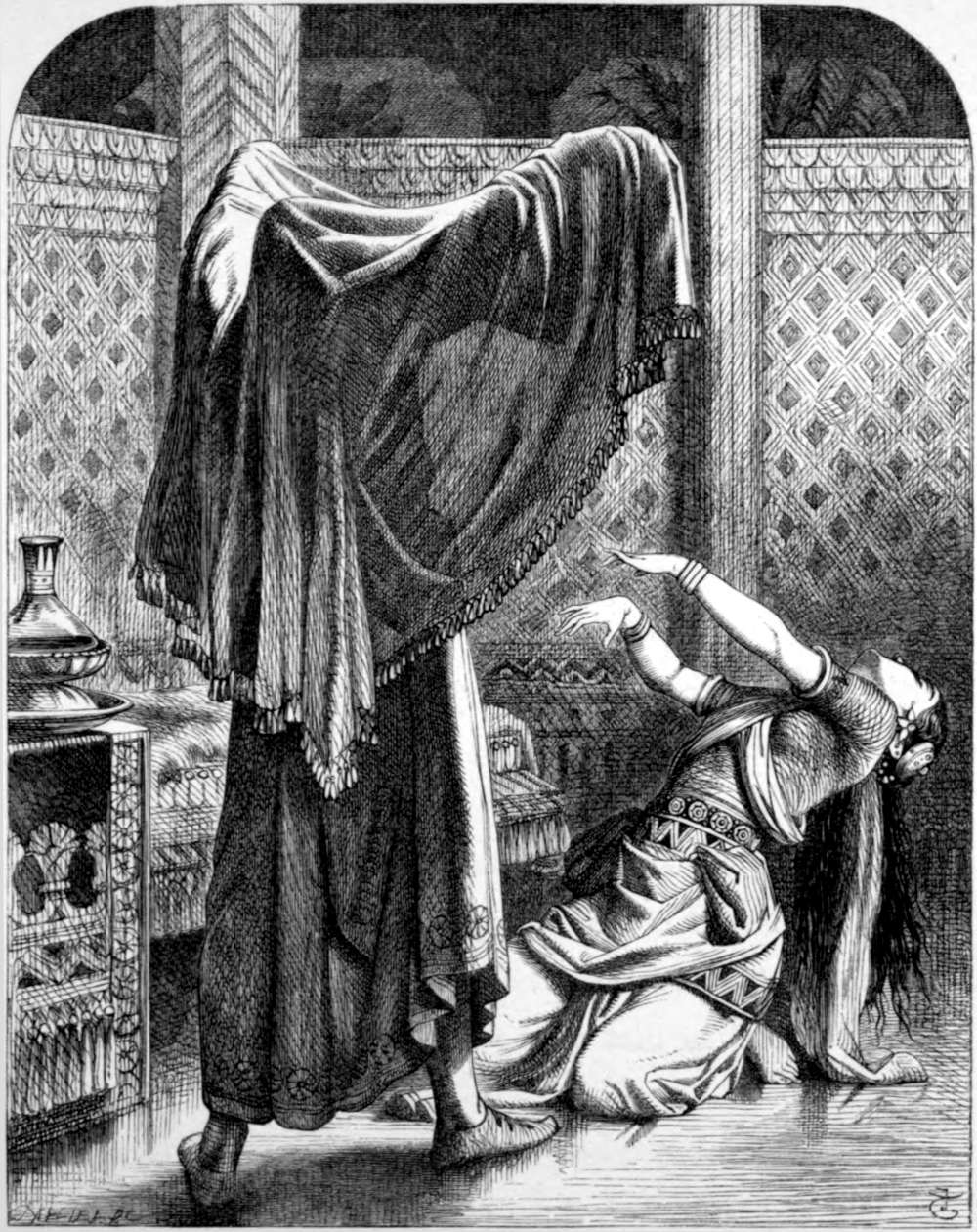

| He raised his veil—the Maid turn’d slowly round, | |

| Look’d at him—shriek’d—and sunk upon the ground! | 47 |

| Now, through the Haram chambers, moving lights | |

| And busy shapes proclaim the toilet’s rites. | 50 |

| Young Azim roams bewilder’d,—nor can guess | |

| What means this maze of light and loneliness. | 53 |

| He sees a group of female forms advance. | 59 |

| “Poor maiden!” thought the youth, “if thou wert sent.” | 62 |

| vi | |

| Oh! could he listen to such sounds unmov’d, | |

| And by that light—nor dream of her he lov’d? | 68 |

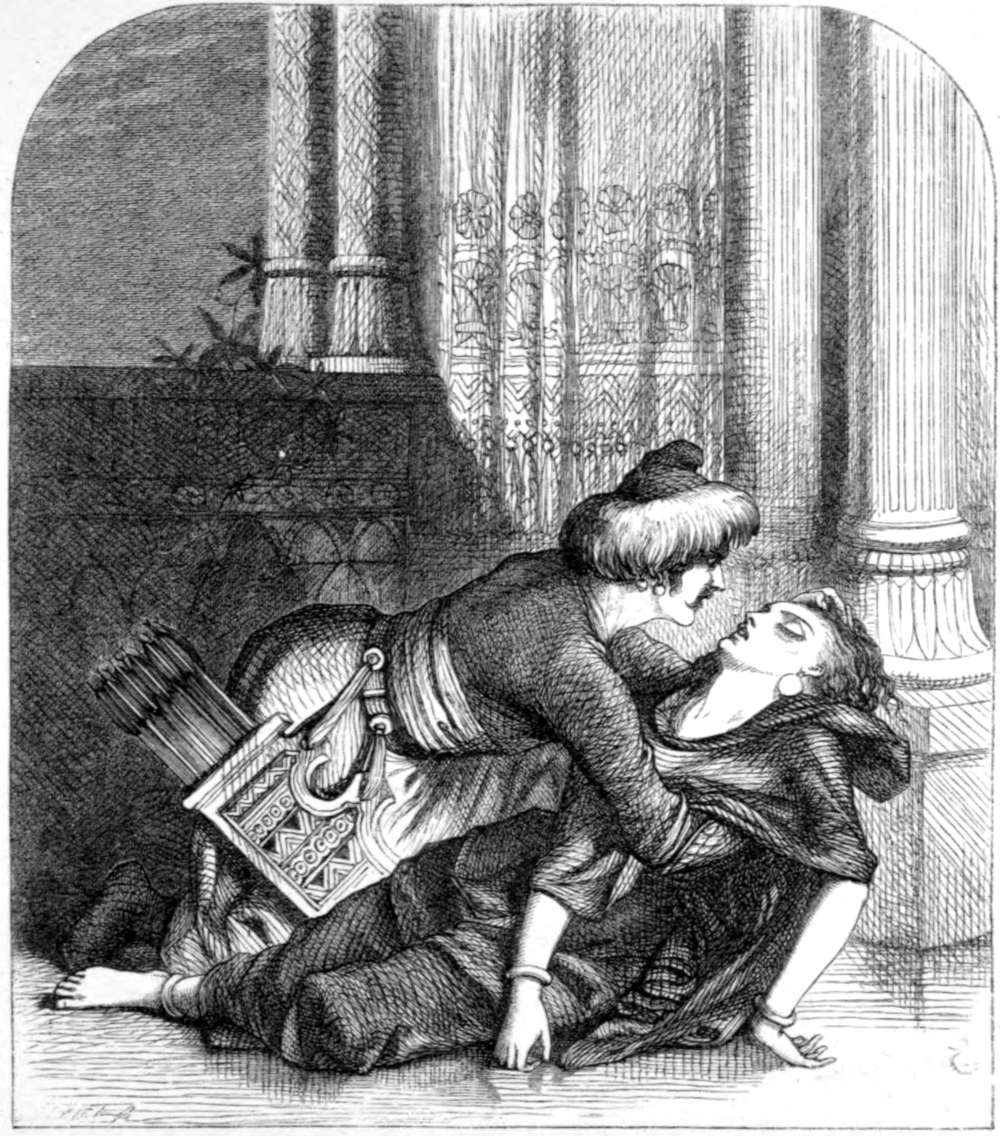

| “Look up, my Zelica—one moment show | |

| Those gentle eyes to me, that I may know.” | 71 |

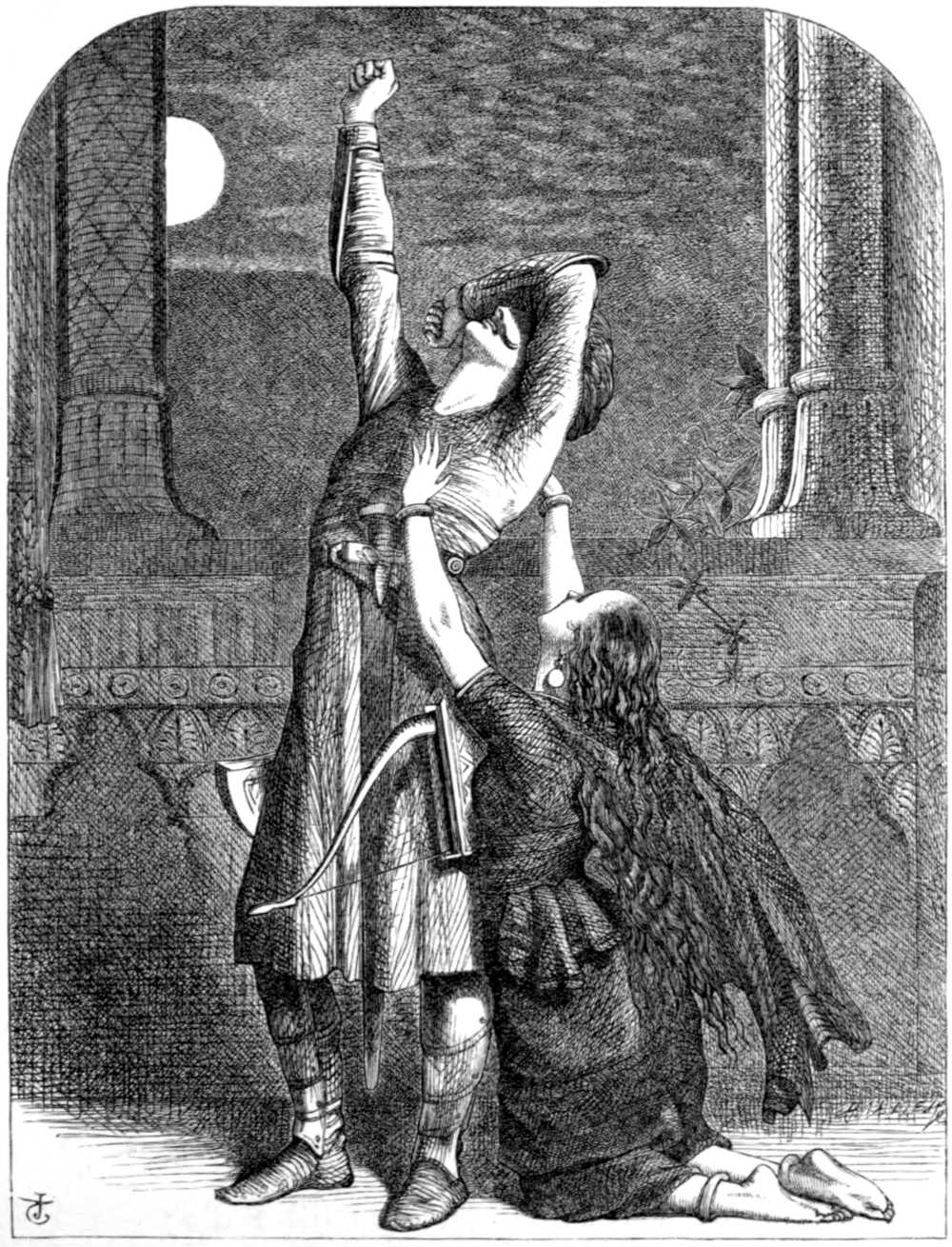

| “Oh! curse me not,” she cried, as wild he toss’d | |

| His desperate hand tow’rds Heaven. | 75 |

| “Thy oath! thy oath!” | 79 |

| They saw a young Hindoo girl upon the bank | 81 |

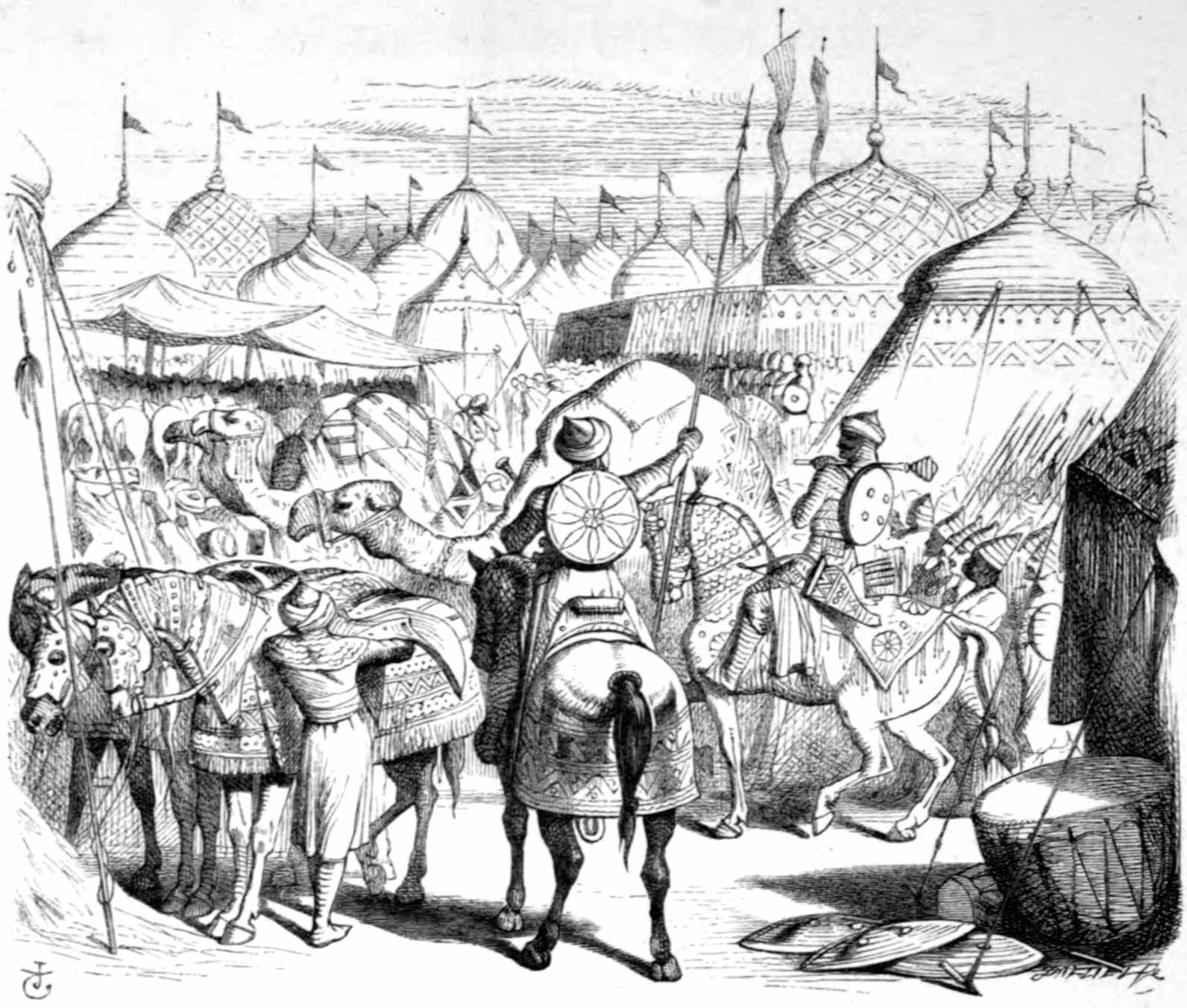

| Whose are the gilded tents that crowd the way? | 84 |

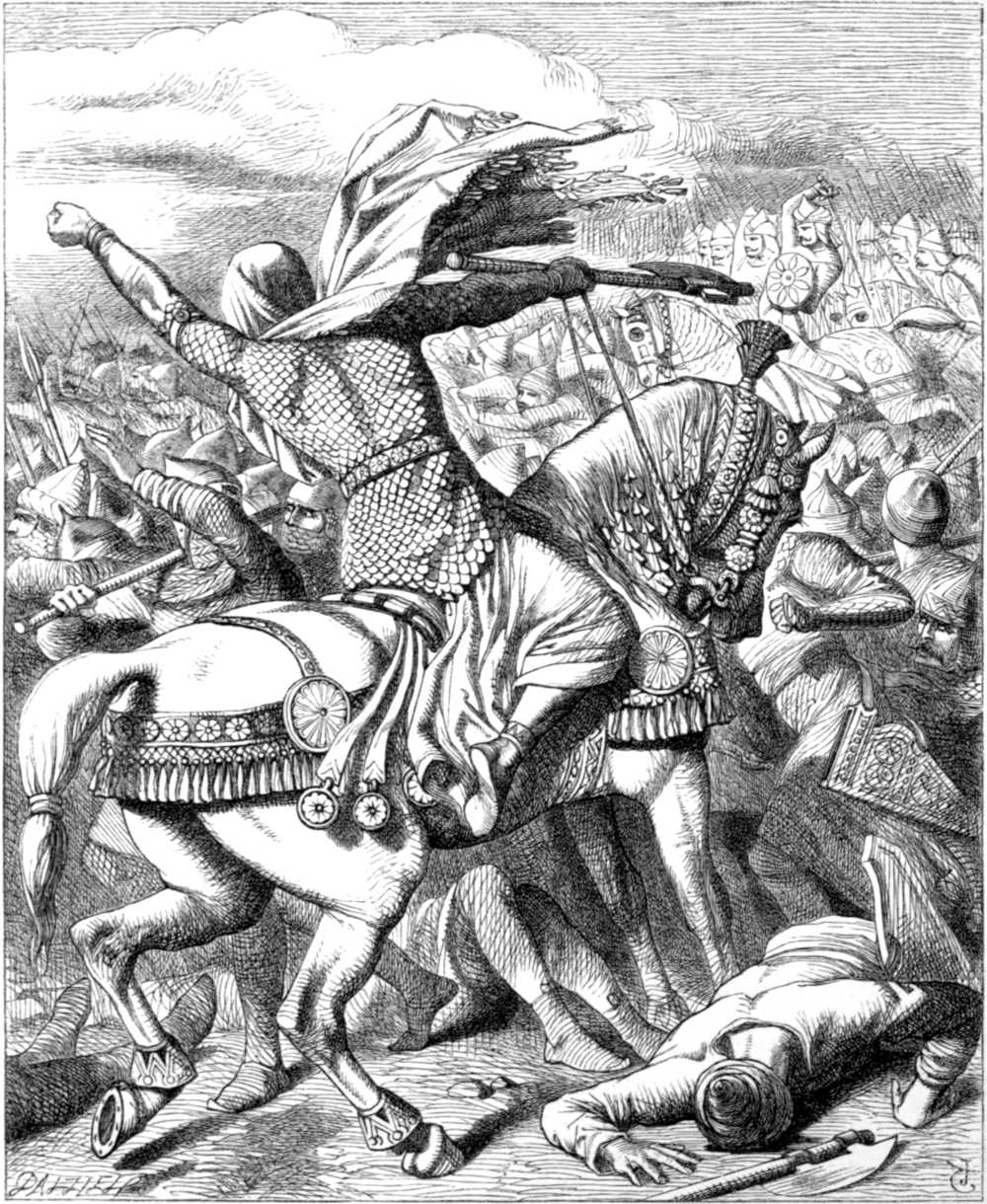

| In vain he yells his desperate curses out. | 90 |

| For this alone exists—like lightning-fire, | |

| To speed one bolt of vengeance, and expire! | 94 |

| And they beheld an orb, ample and bright, | |

| Rise from the Holy Well. | 98 |

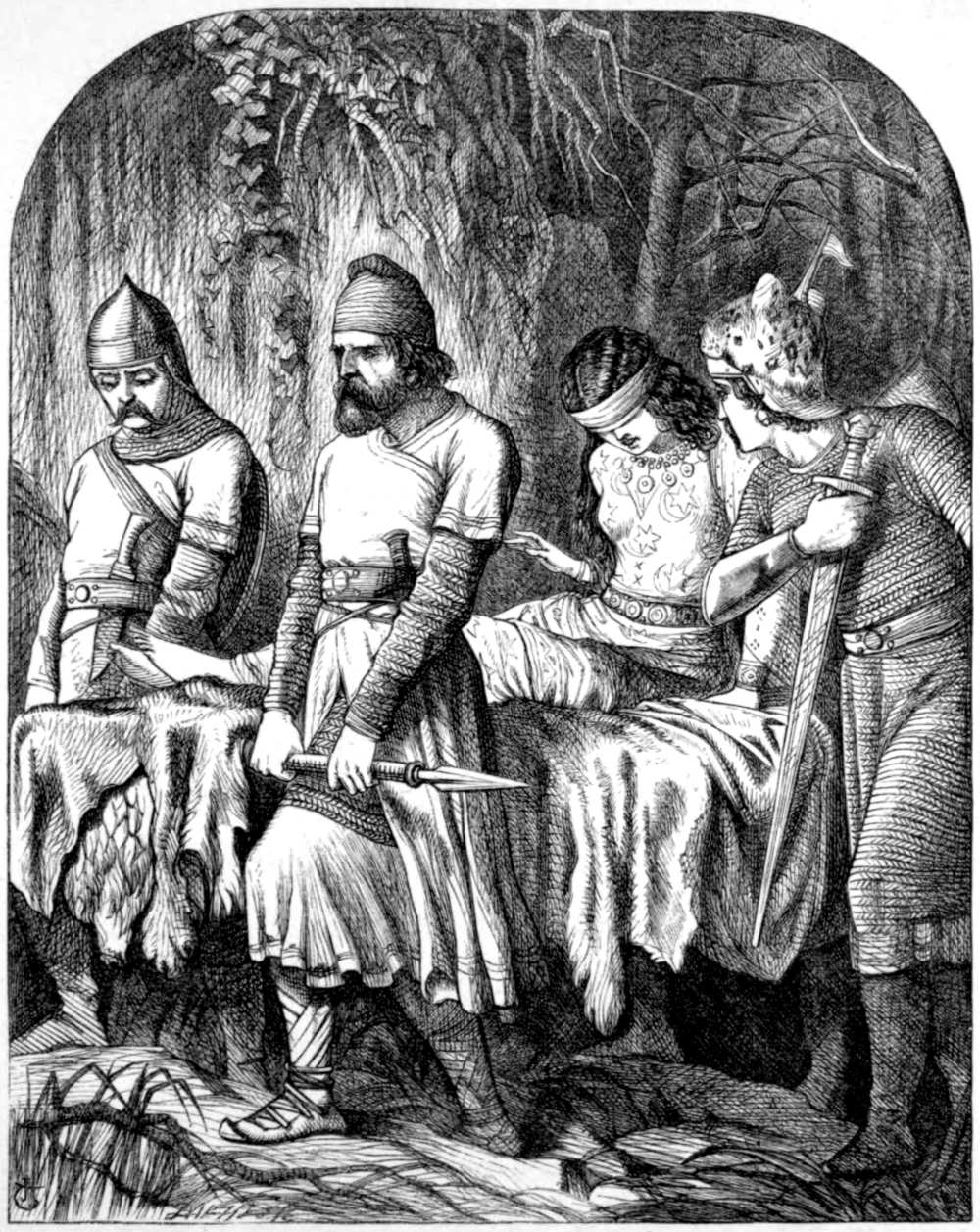

| And led her glittering forth before the eyes | |

| Of his rude train, as to a sacrifice. | 102 |

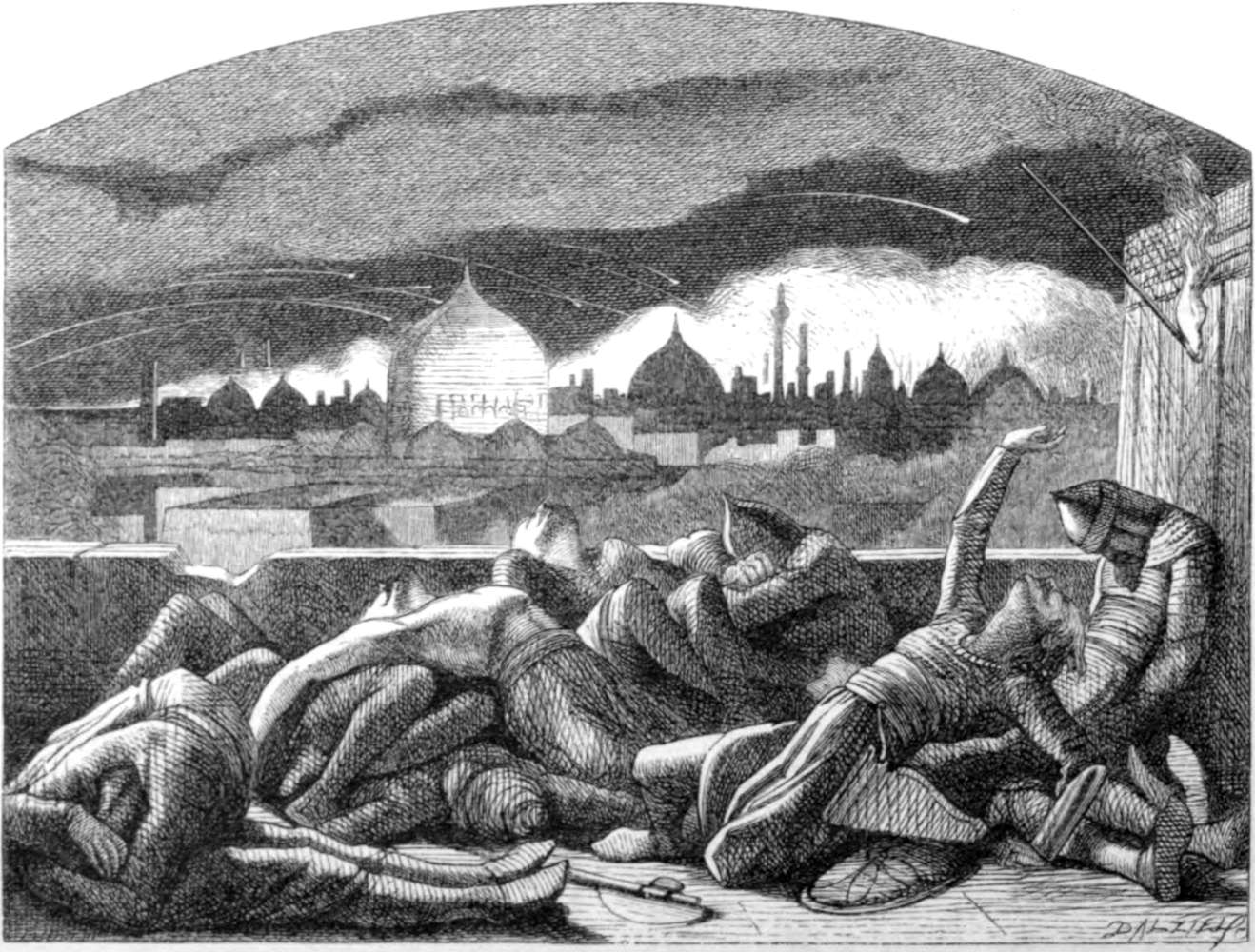

| And death and conflagration throughout all | |

| The desolate city hold high festival! | 104 |

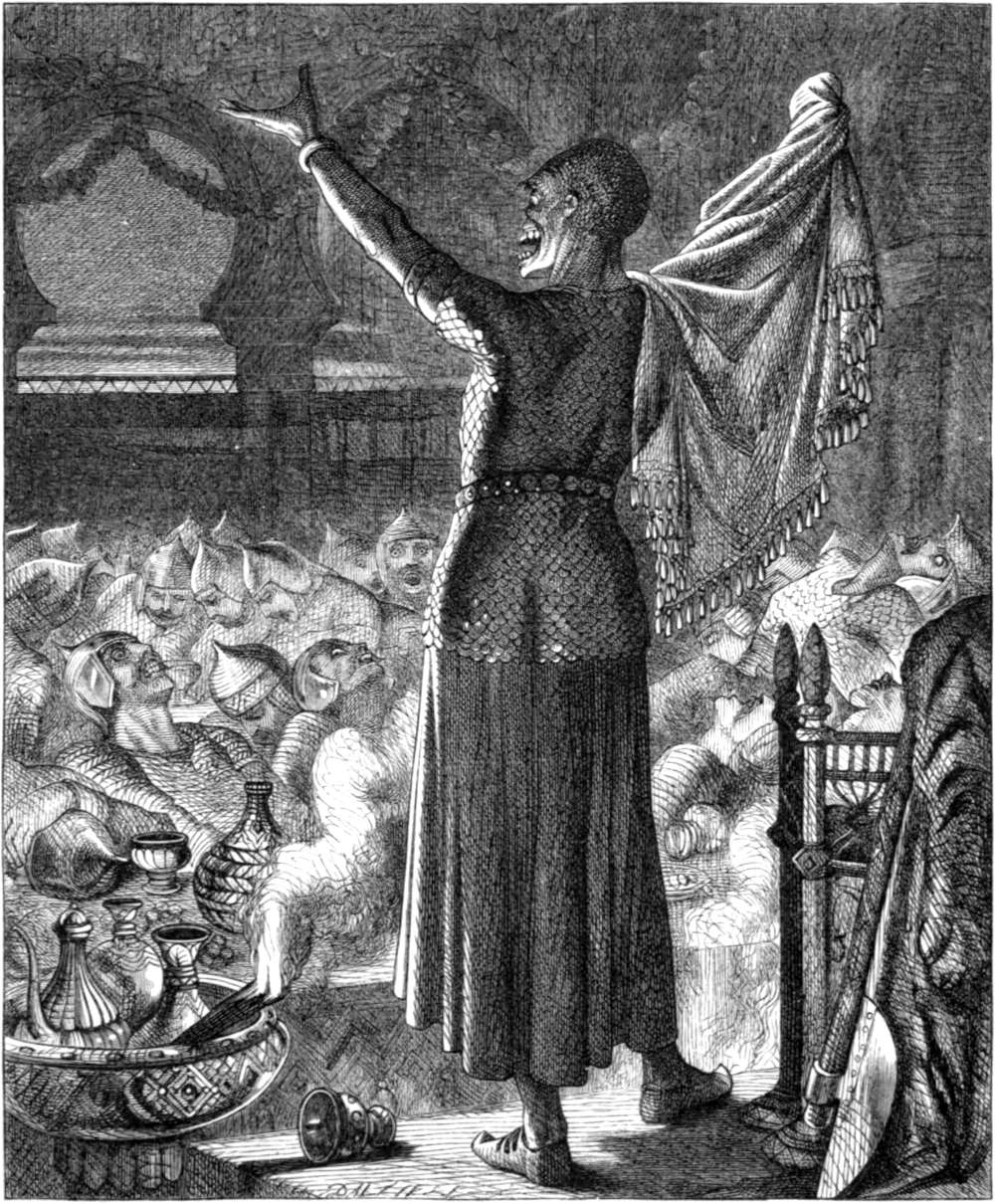

| “There, ye wise Saints, behold your Light, your Star— | |

| Ye would be dupes and victims, and ye are.” | 109 |

| He sprung and sunk, as the last words were said— | |

| Quick clos’d the burning waters o’er his head. | 113 |

| “And pray that He may pardon her,—may take | |

| Compassion on her soul for thy dear sake.” | 117 |

| For this the old man breath’d his thanks and died. | 119 |

| PARADISE AND THE PERI. | |

| Ornamental Title-page | 127 |

| [Architectural details from Baghdad, &c.] | |

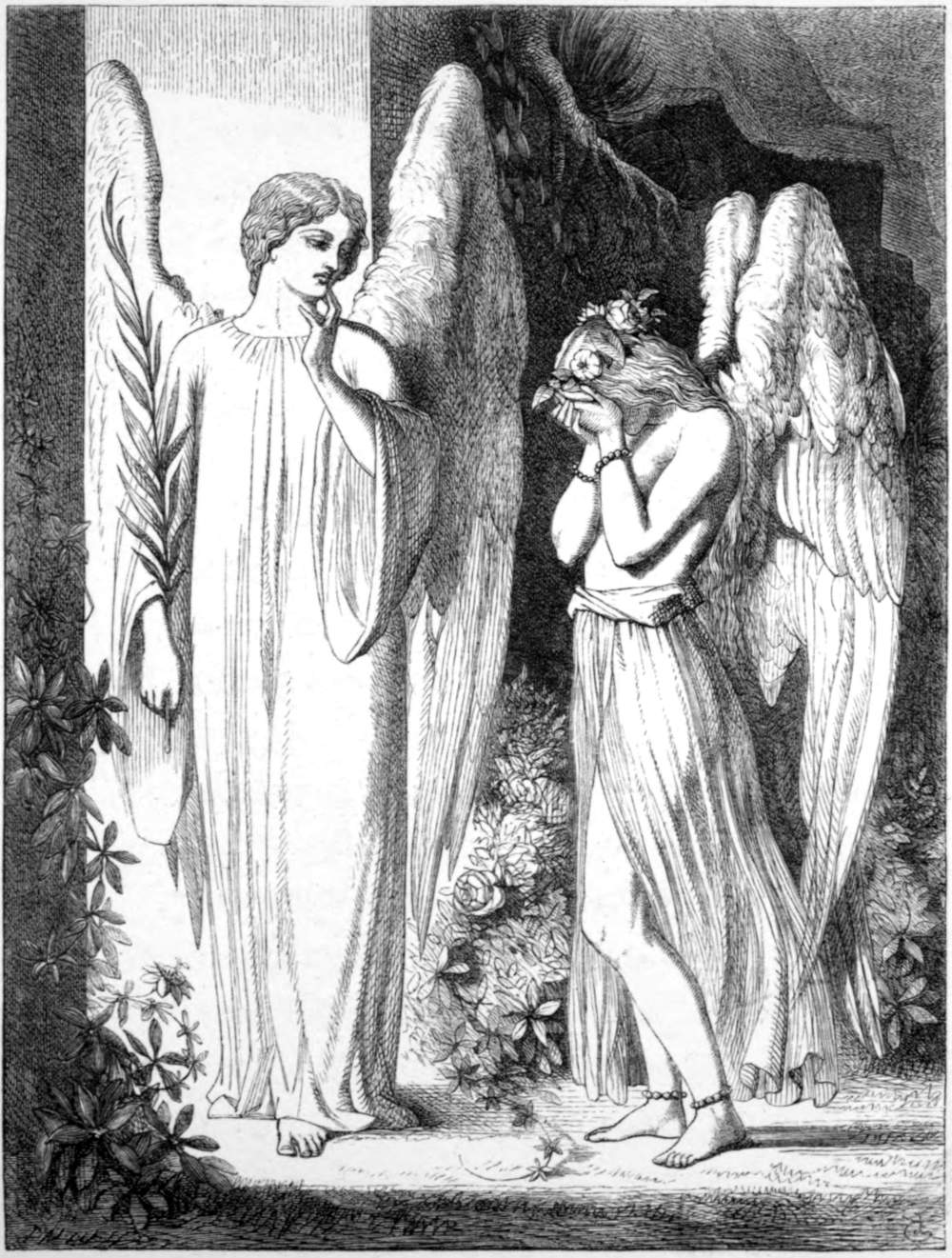

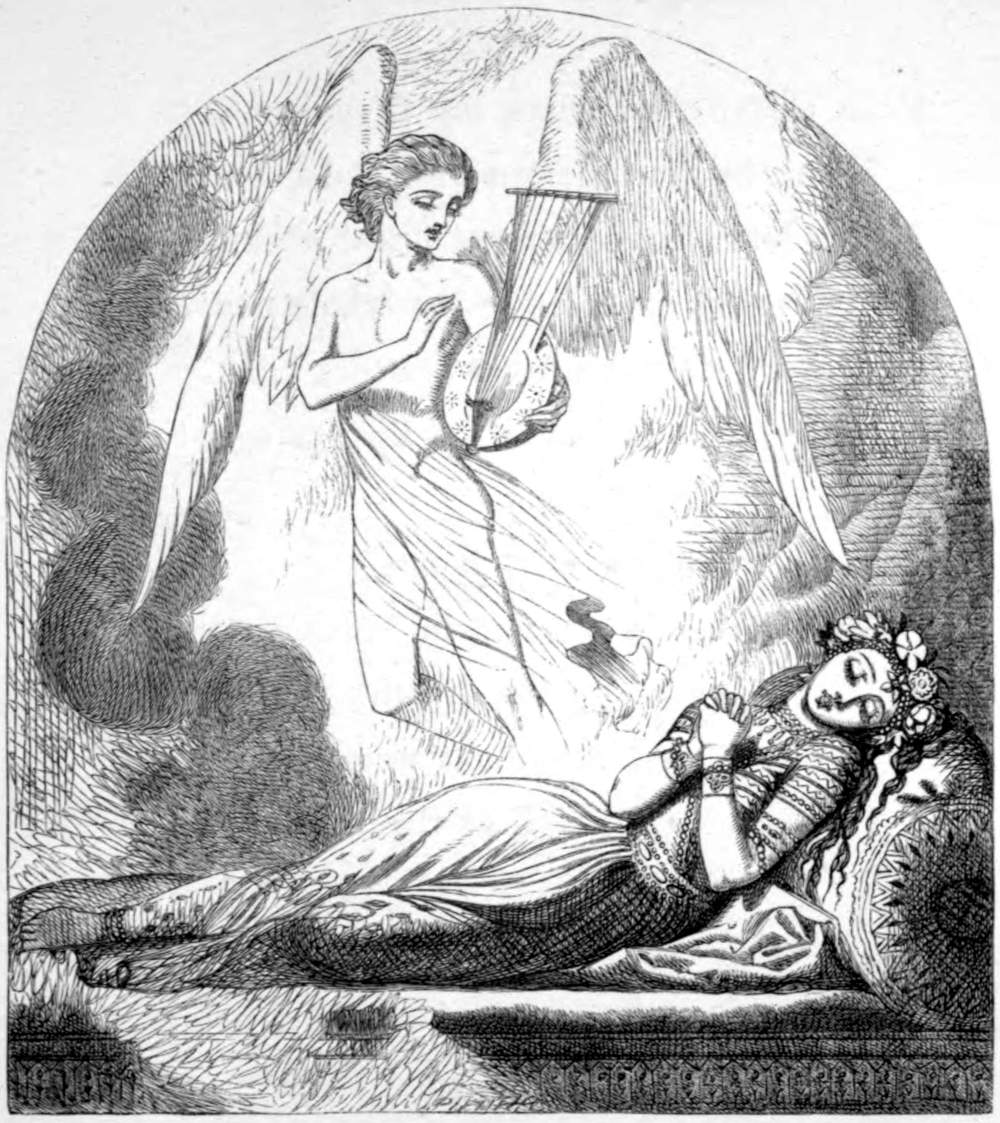

| The glorious Angel, who was keeping | |

| The gates of Light, beheld her weeping. | 129 |

| ⸺She caught the last— | |

| Last glorious drop his heart had shed. | 135 |

| Like their good angel, calmly keeping | |

| Watch o’er them till their souls would waken. | 143 |

| vii | |

| Then swift his haggard brow he turn’d | |

| To the fair child, who fearless sat. | 148 |

| Blest tears of soul-felt penitence! | 151 |

| And now—behold him kneeling there | |

| By the child’s side, in humble prayer. | 152 |

| “Joy, joy for ever!—my task is done.” | 154 |

| THE FIRE WORSHIPPERS. | |

| Ornamental Title-page | 167 |

| [In part from the binding of a “Shah Namah,” in the East India House Library.] | |

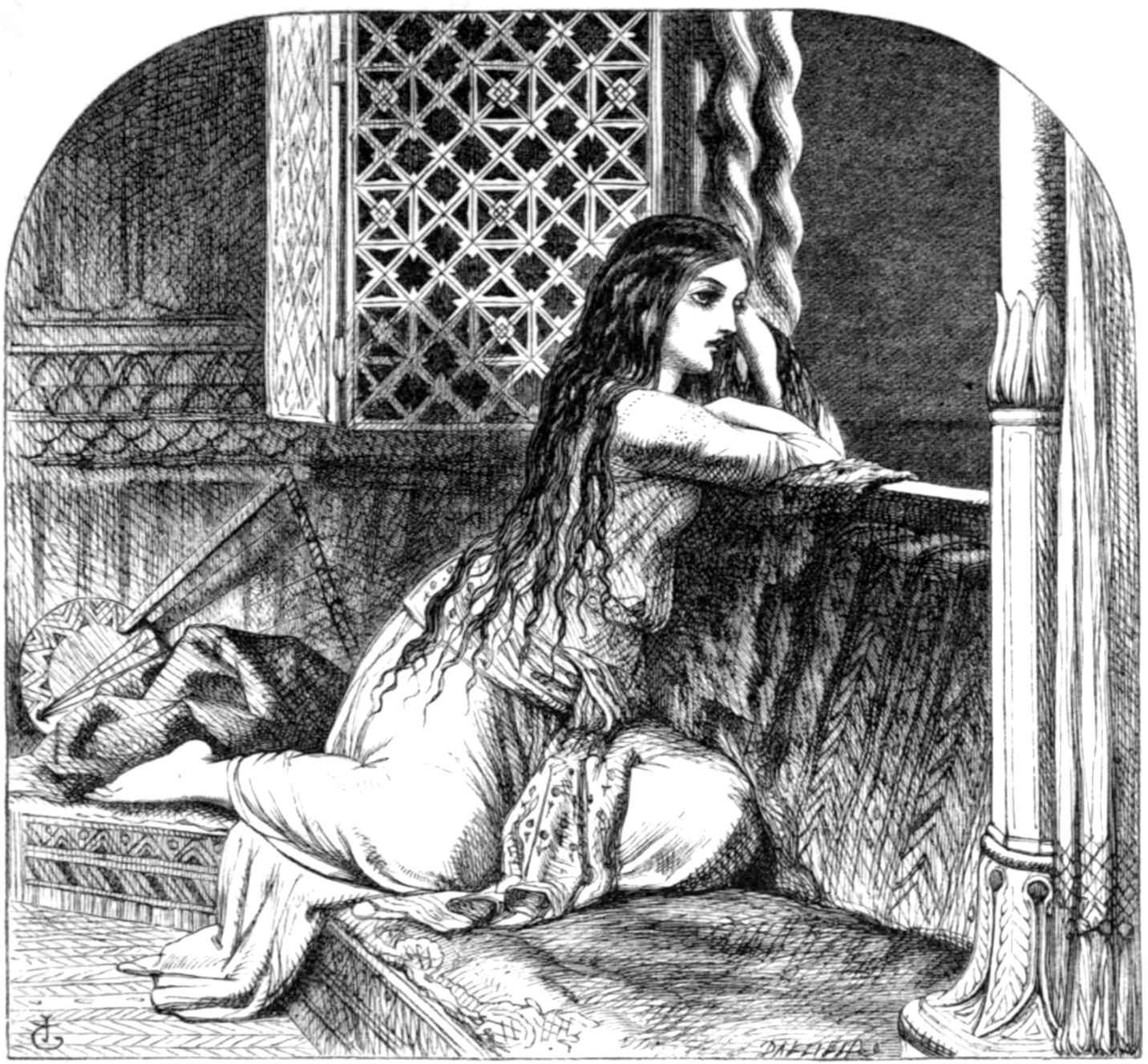

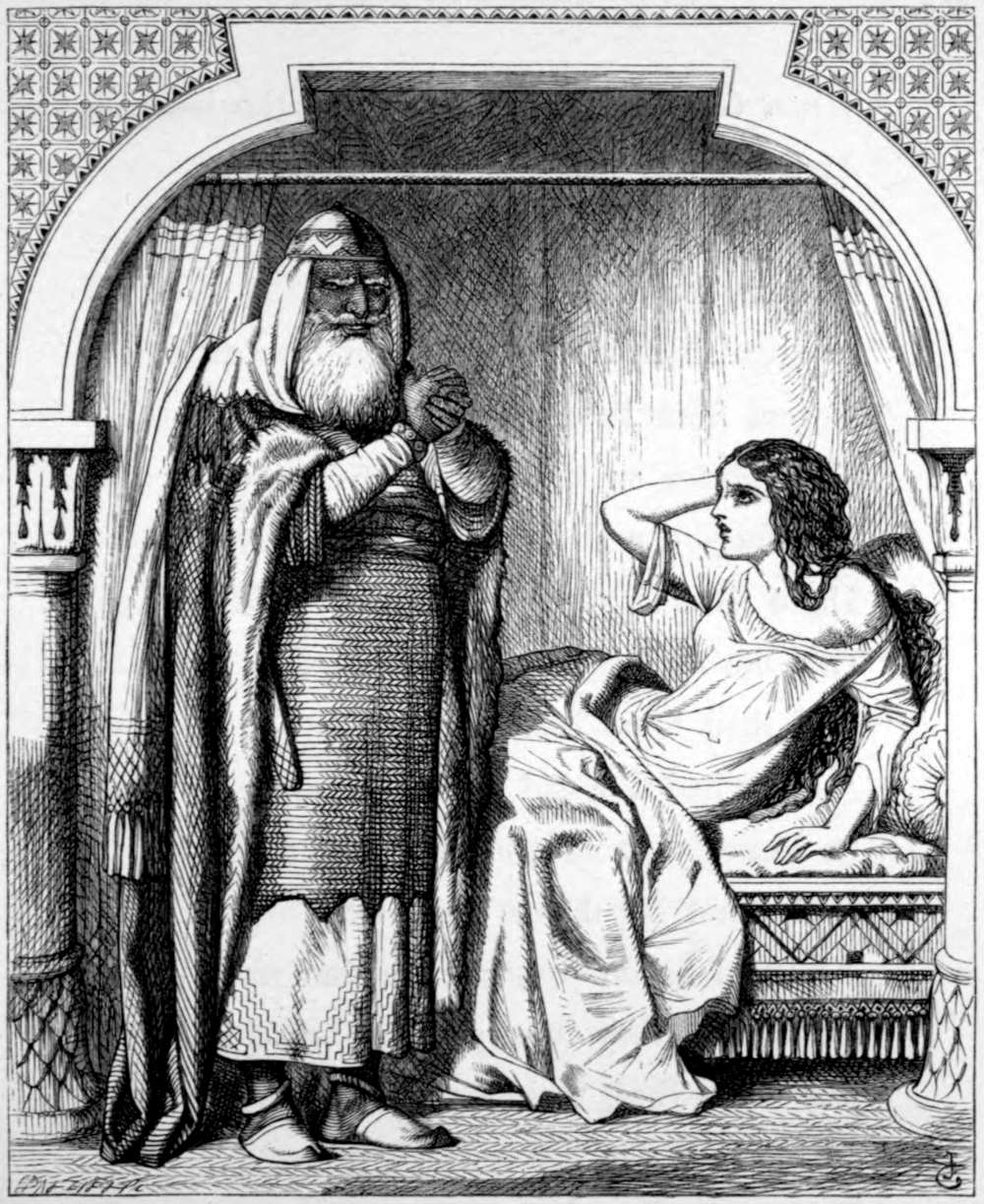

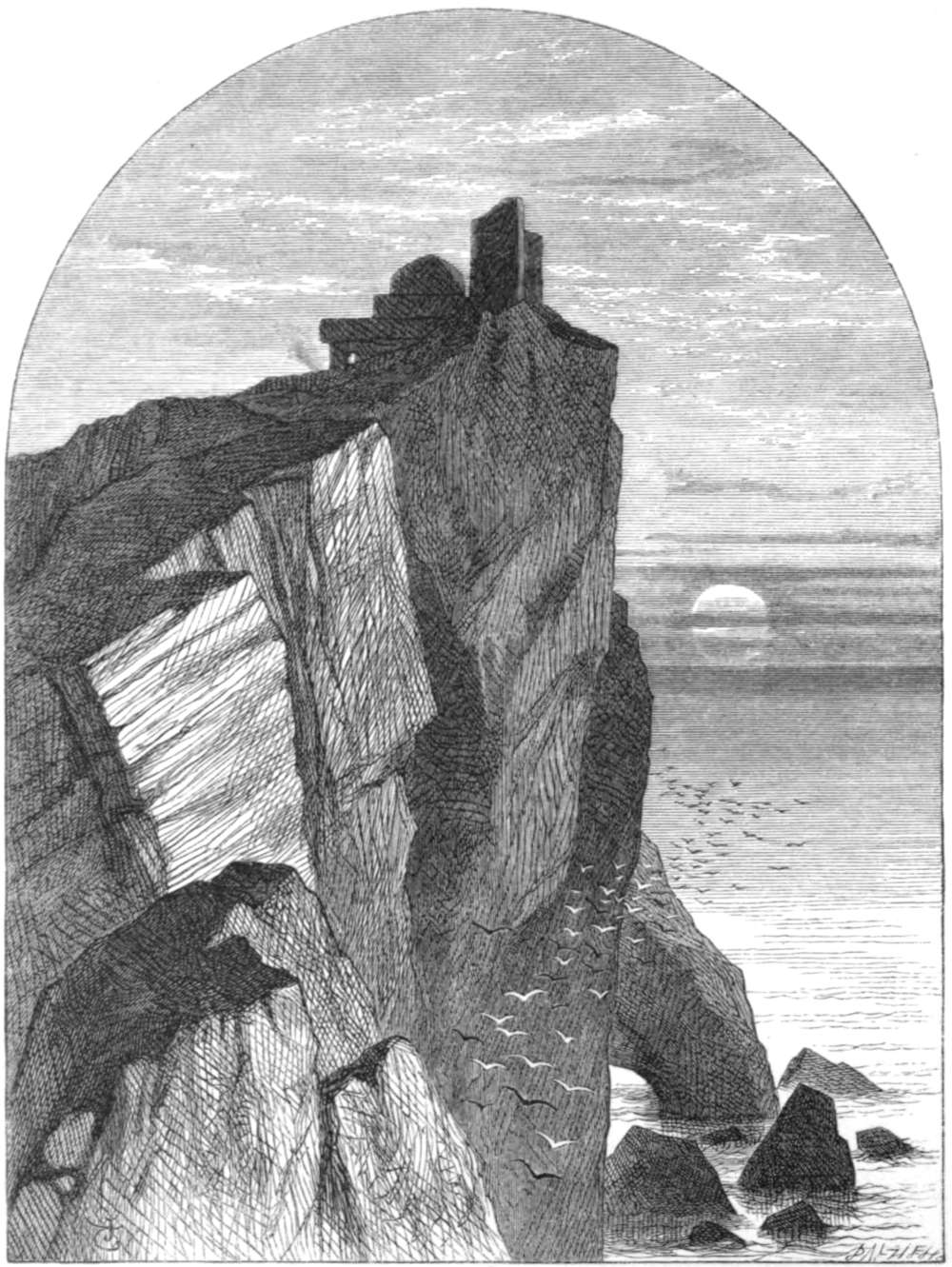

| And sits alone in that high bower | |

| Watching the still and shining deep. | 169 |

| “Oh! ever thus, from childhood’s hour, | |

| I’ve seen my fondest hopes decay.” | 181 |

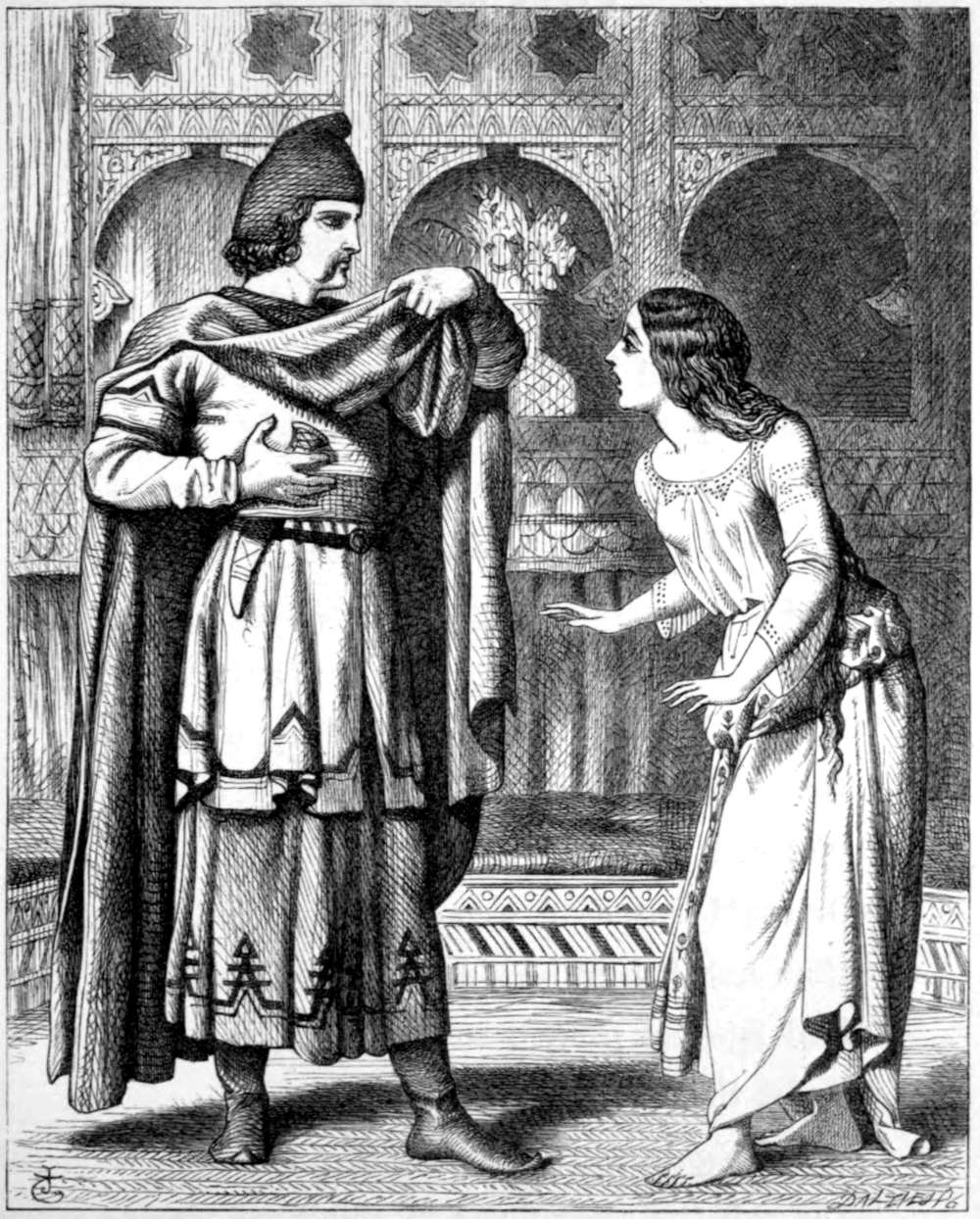

| “Here, maiden, look—weep—blush to see | |

| All that thy sire abhors in me!” | 185 |

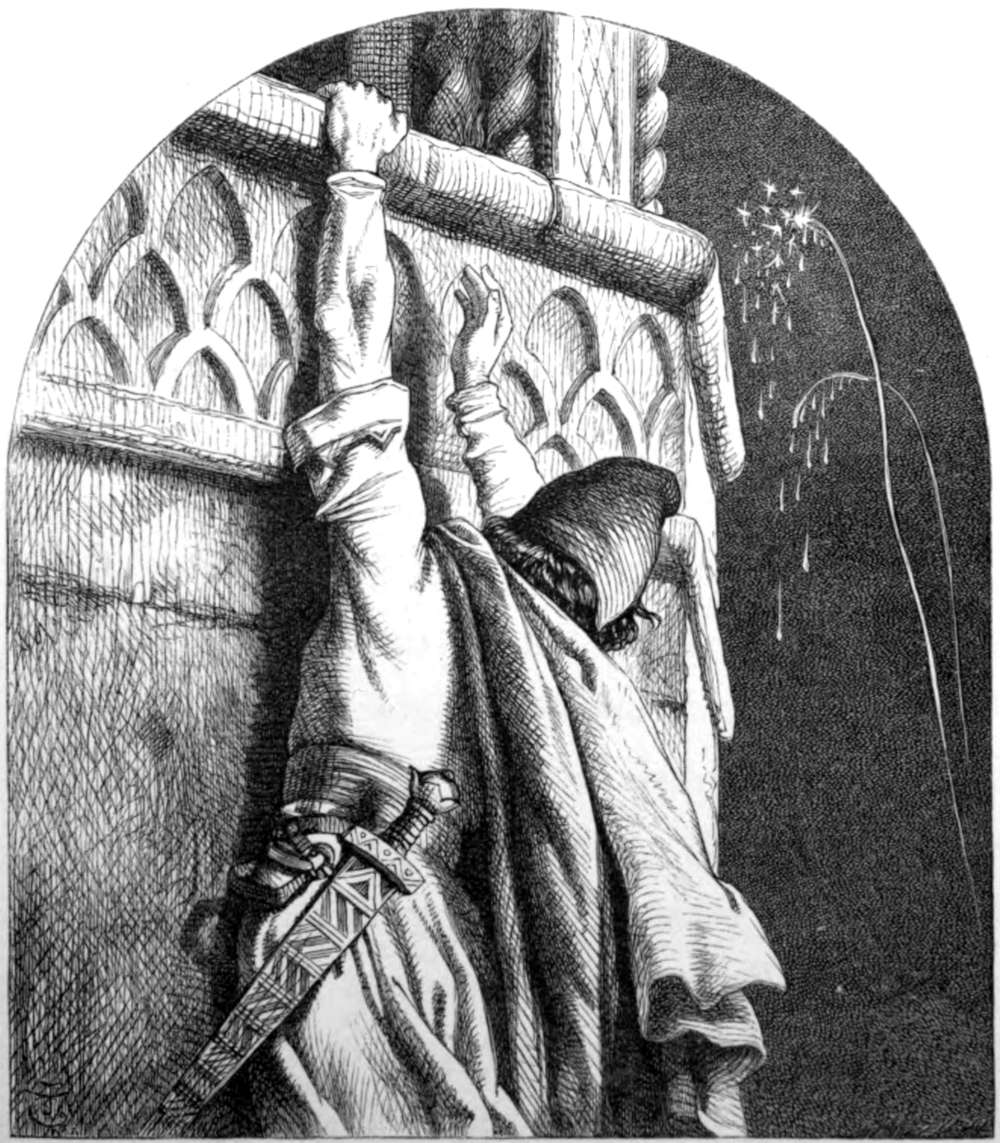

| Fiercely he broke away, nor stopp’d, | |

| Nor look’d—but from the lattice dropp’d. | 189 |

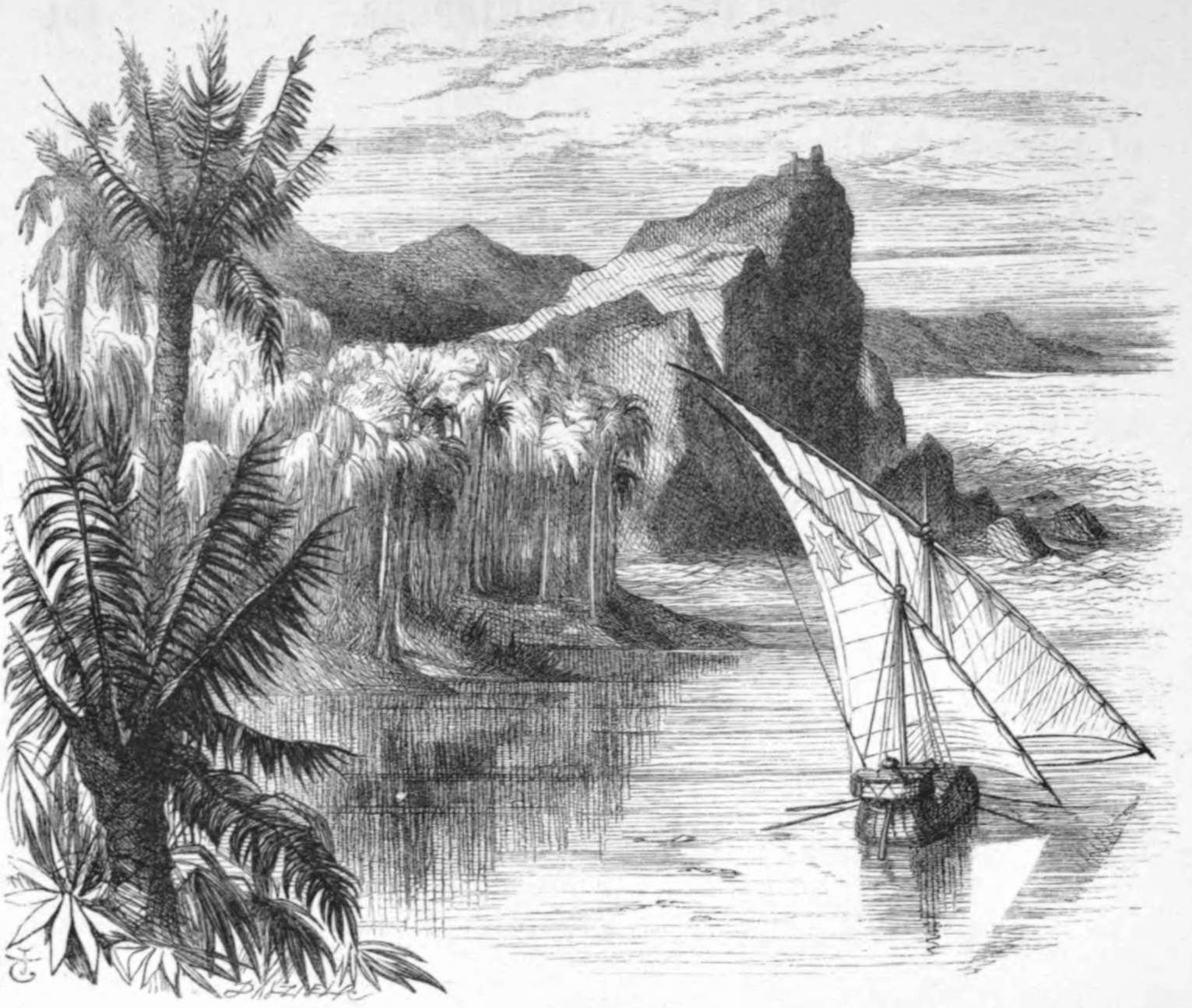

| The morn hath risen clear and calm, | |

| And o’er the Green Sea palely shines. | 192 |

| ’Tis Hafed—name of fear, whose sound | |

| Chills like the muttering of a charm! | 197 |

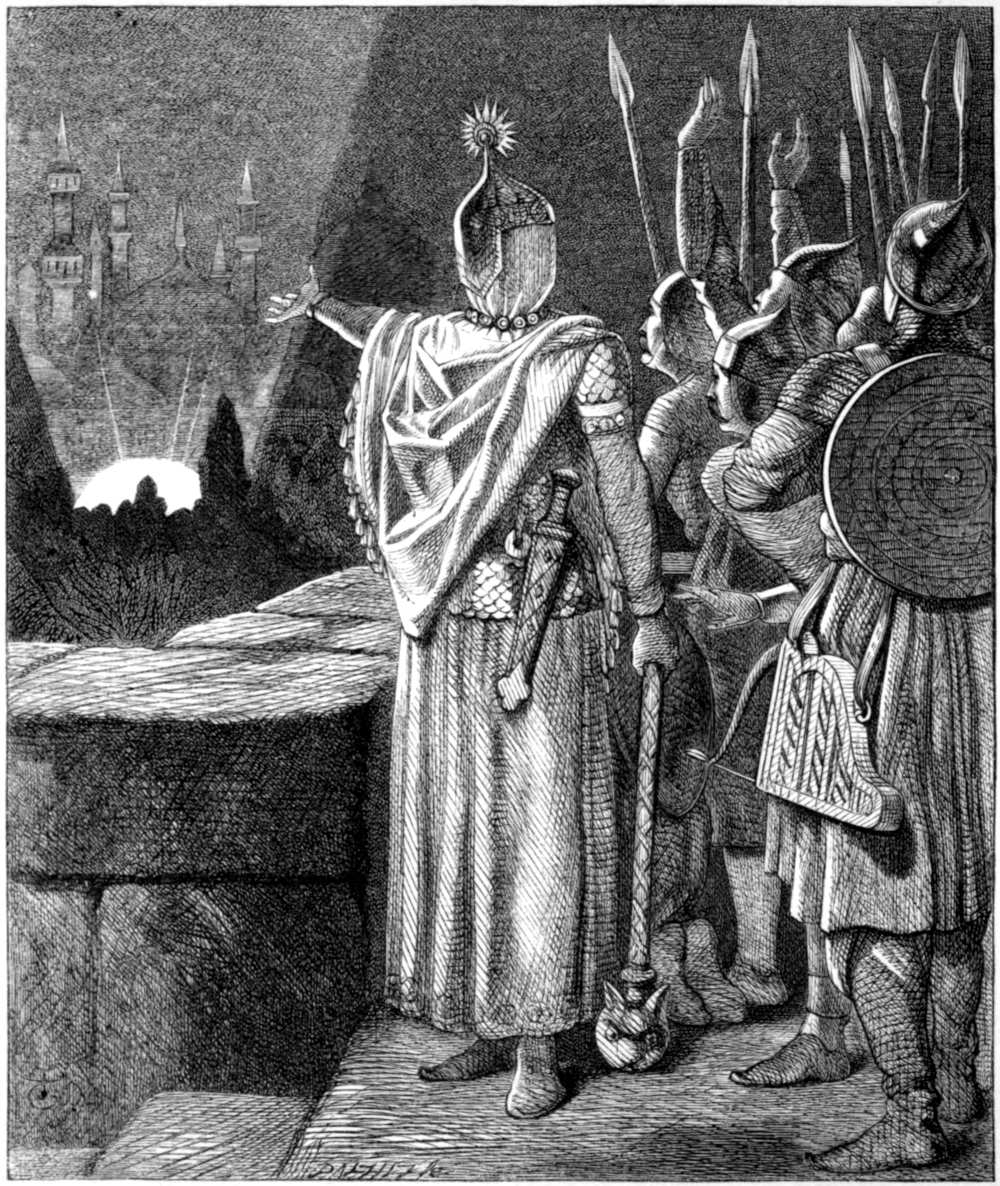

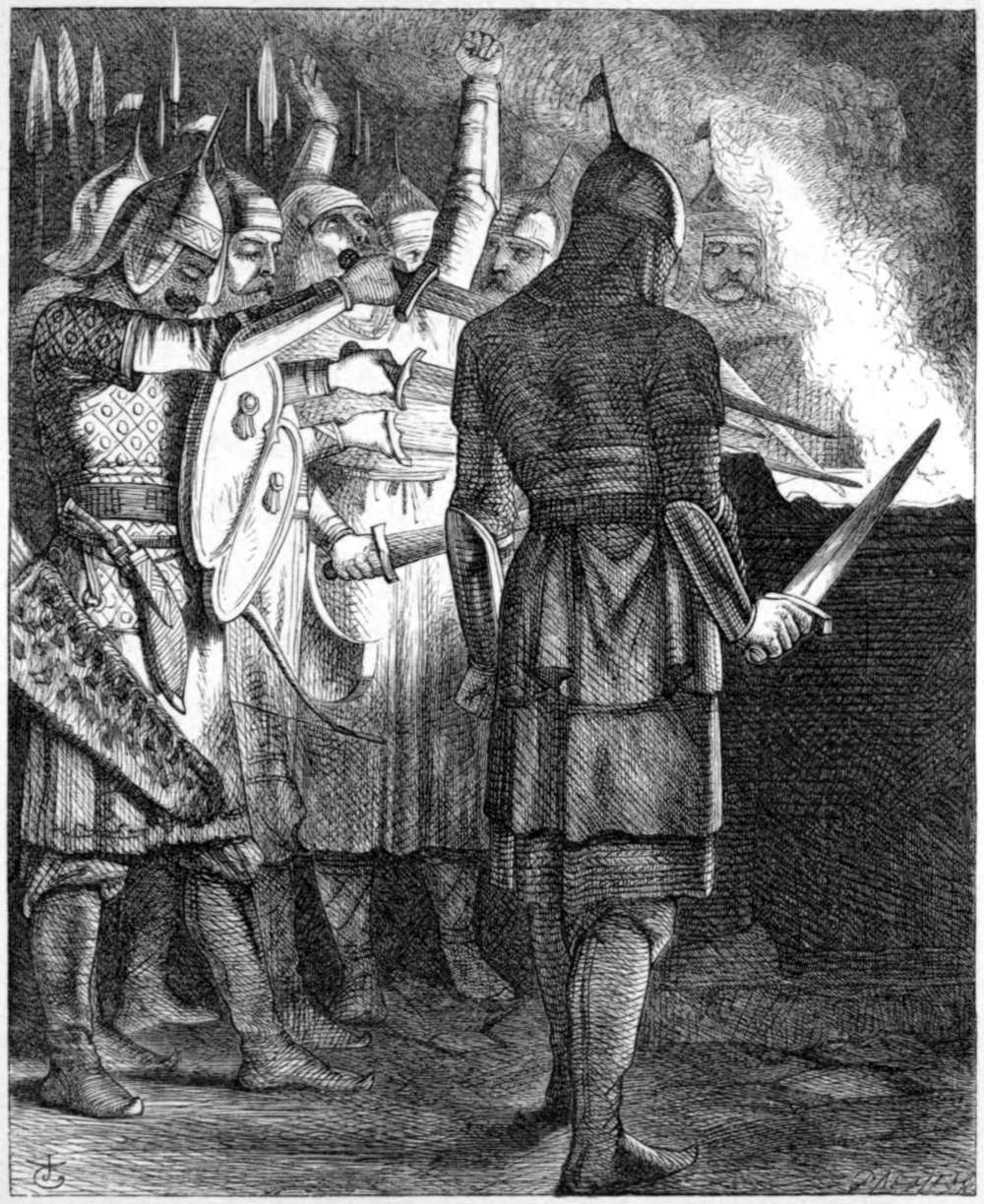

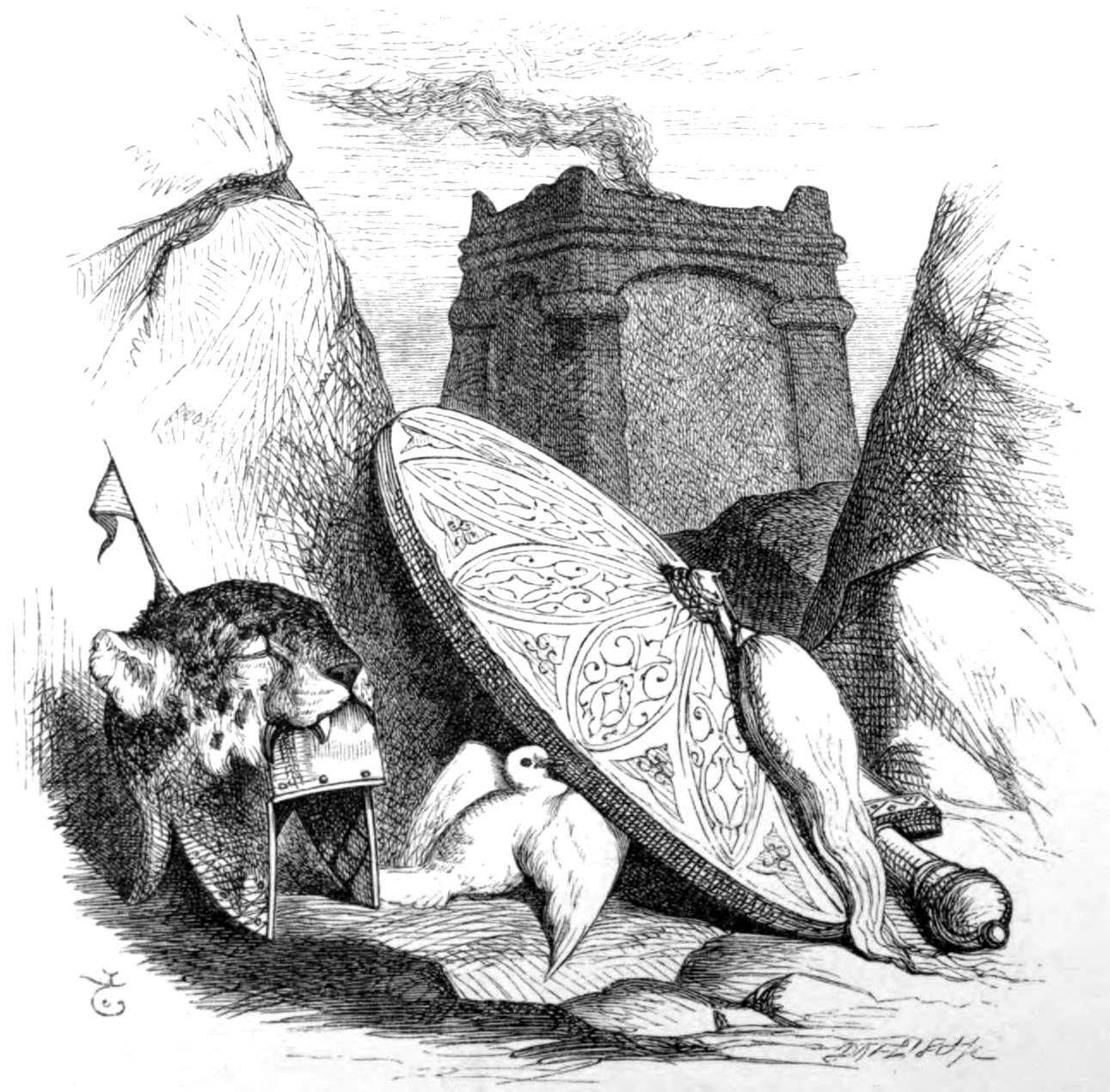

| His Chiefs stood round—each shining blade | |

| Upon the broken altar laid. | 205 |

| “This very night his blood shall steep | |

| These hands all over ere I sleep!” | 211 |

| And o’er the wide, tempestuous wave | |

| Looks, with a shudder, to those towers. | 216 |

| And snatch’d her breathless from beneath | |

| This wilderment of wreck and death. | 222 |

| Shuddering, she look’d around—there lay | |

| A group of warriors in the sun. | 227 |

| “Tremble not, love, thy Gheber’s here!” | 233 |

| Ancient Persian Fire-Altar, &c. &c. | 236 |

| ’Twas one of those ambrosial eves | |

| A day of storm so often leaves. | 238 |

| viii | |

| Breathless she stands, with eyes cast down. | 241 |

| He felt it—deeply felt—and stood, | |

| As if the tale had frozen his blood. | 248 |

| A signal, deep and dread as those | |

| The storm-fiend at his rising blows. | 254 |

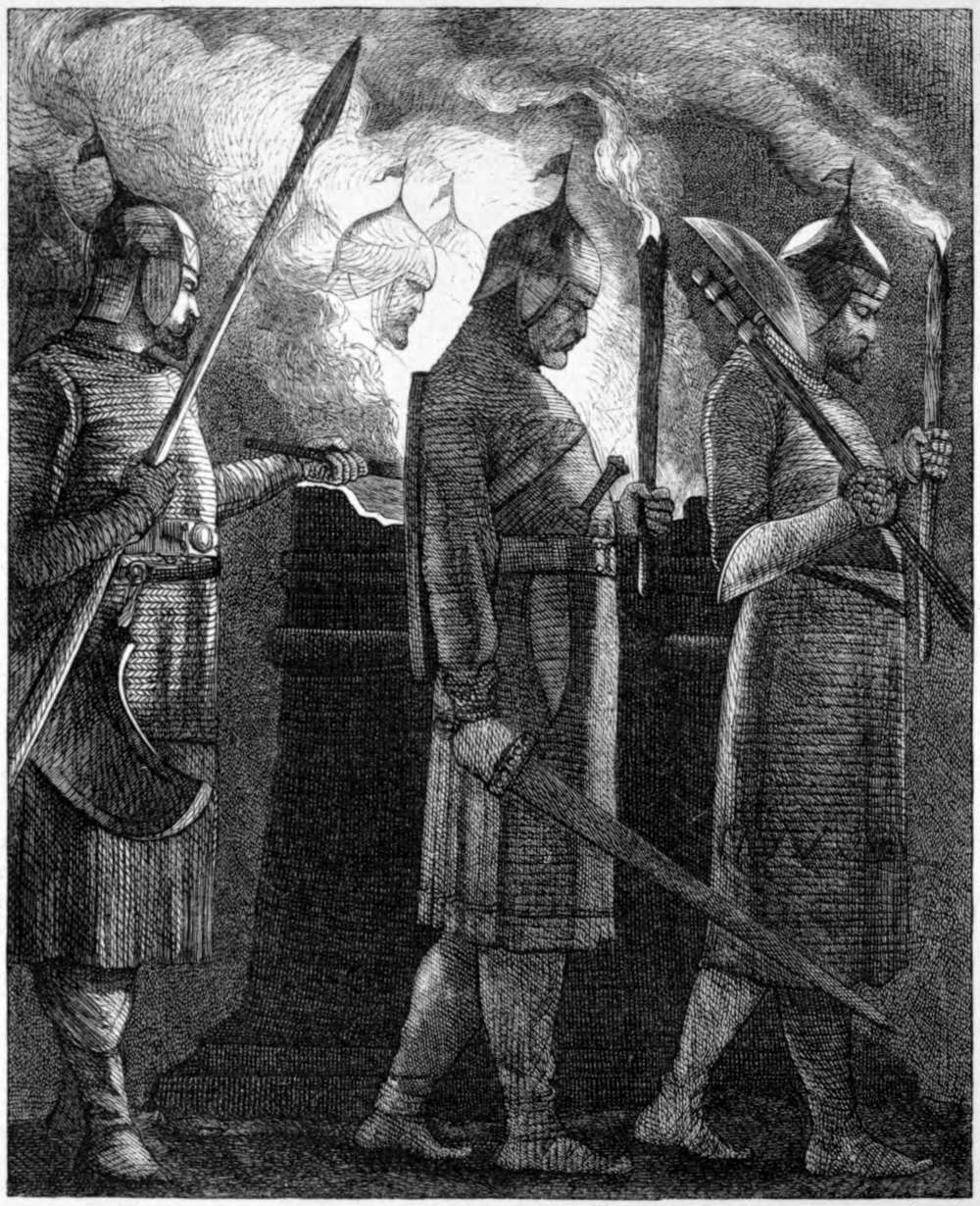

| As mute they pass’d before the flame | |

| To light their torches as they pass’d. | 256 |

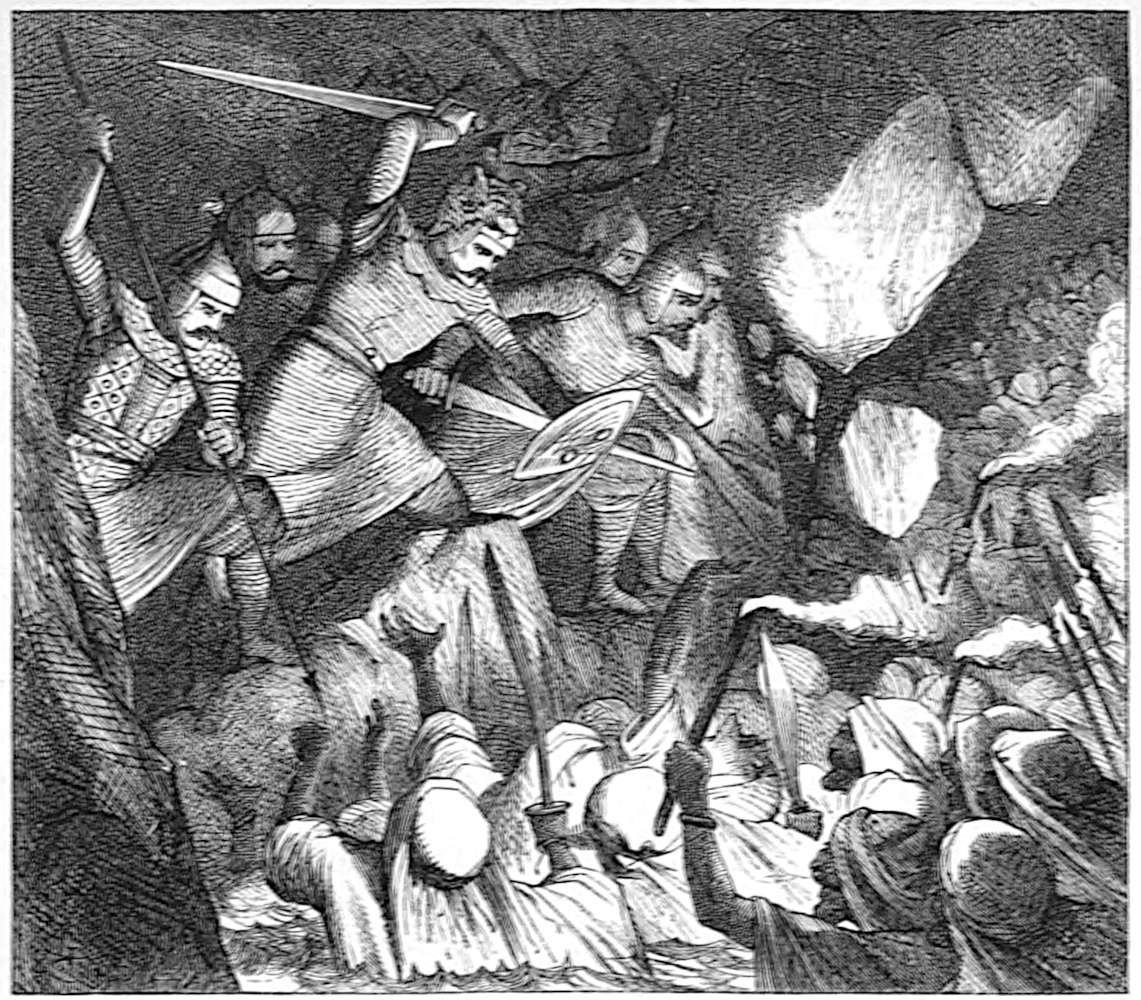

| They come—that plunge into the water | |

| Gives signal for the work of slaughter. | 263 |

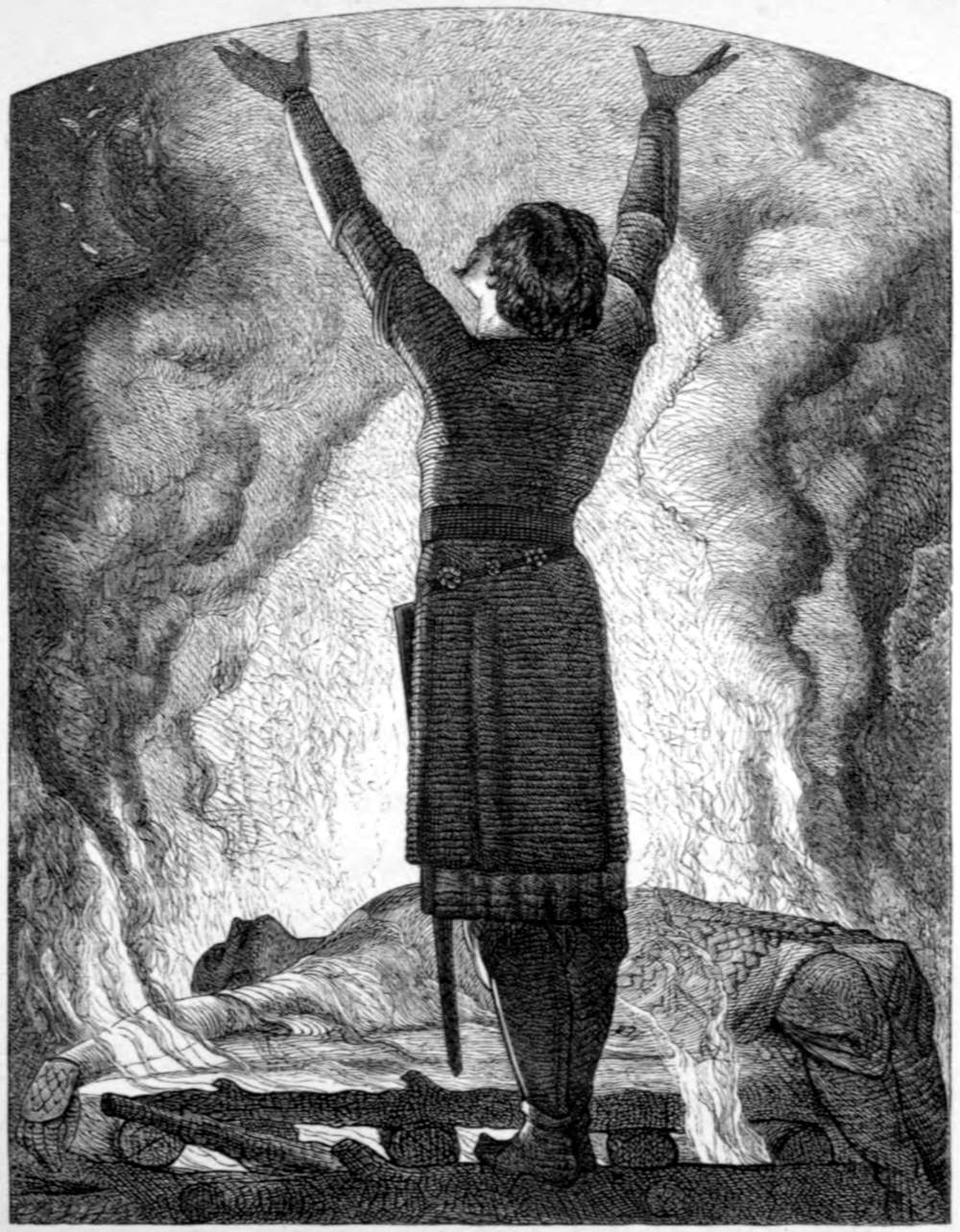

| “Now, Freedom’s God! I come to Thee.” | 269 |

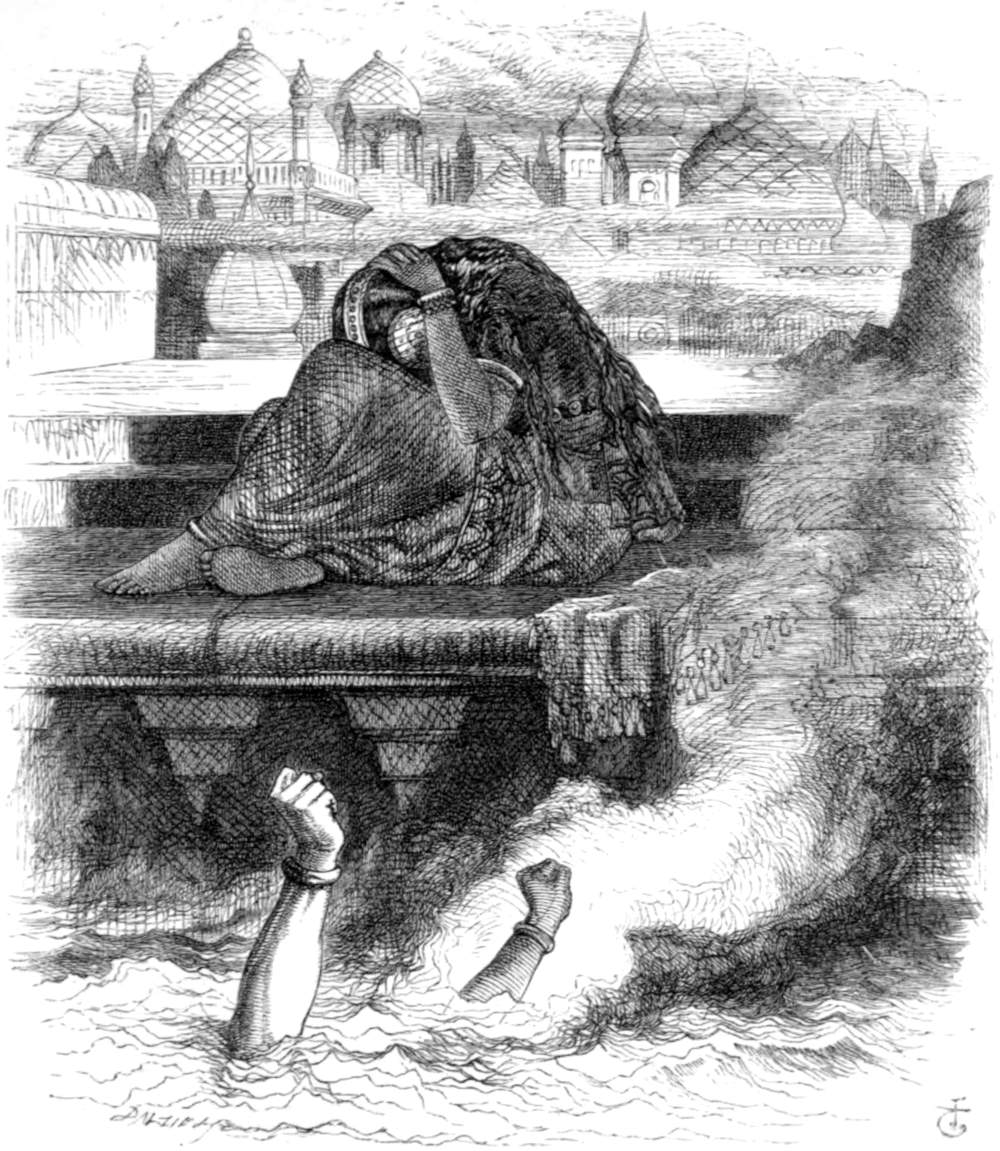

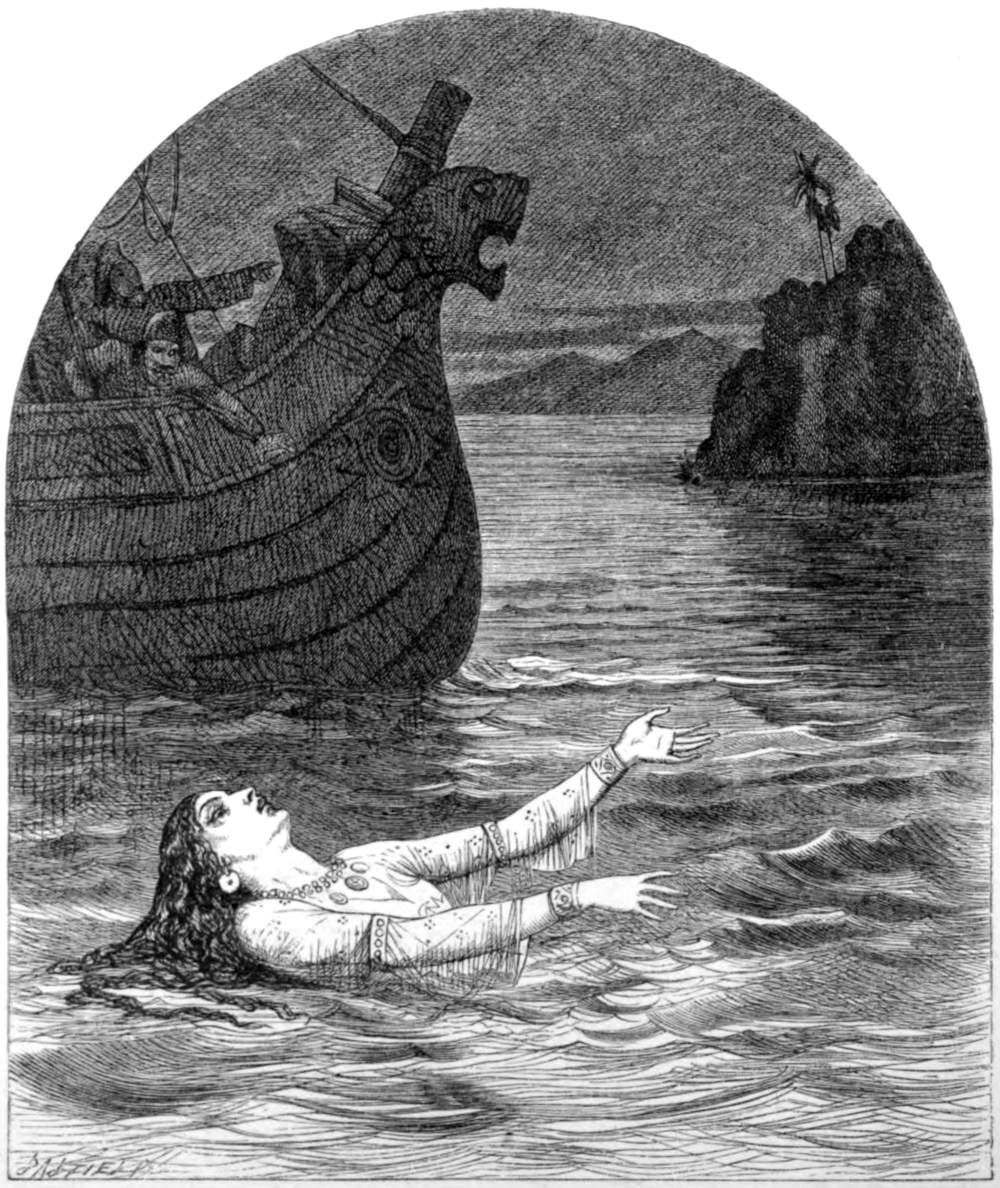

| Where still she fix’d her dying gaze,— | |

| And, gazing, sunk into the wave. | 274 |

| “Farewell—farewell to thee, Araby’s daughter!” | 277 |

| THE LIGHT OF THE HARAM. | |

| Ornamental Title-page | 283 |

| [From porcelain and illuminated MSS.] | |

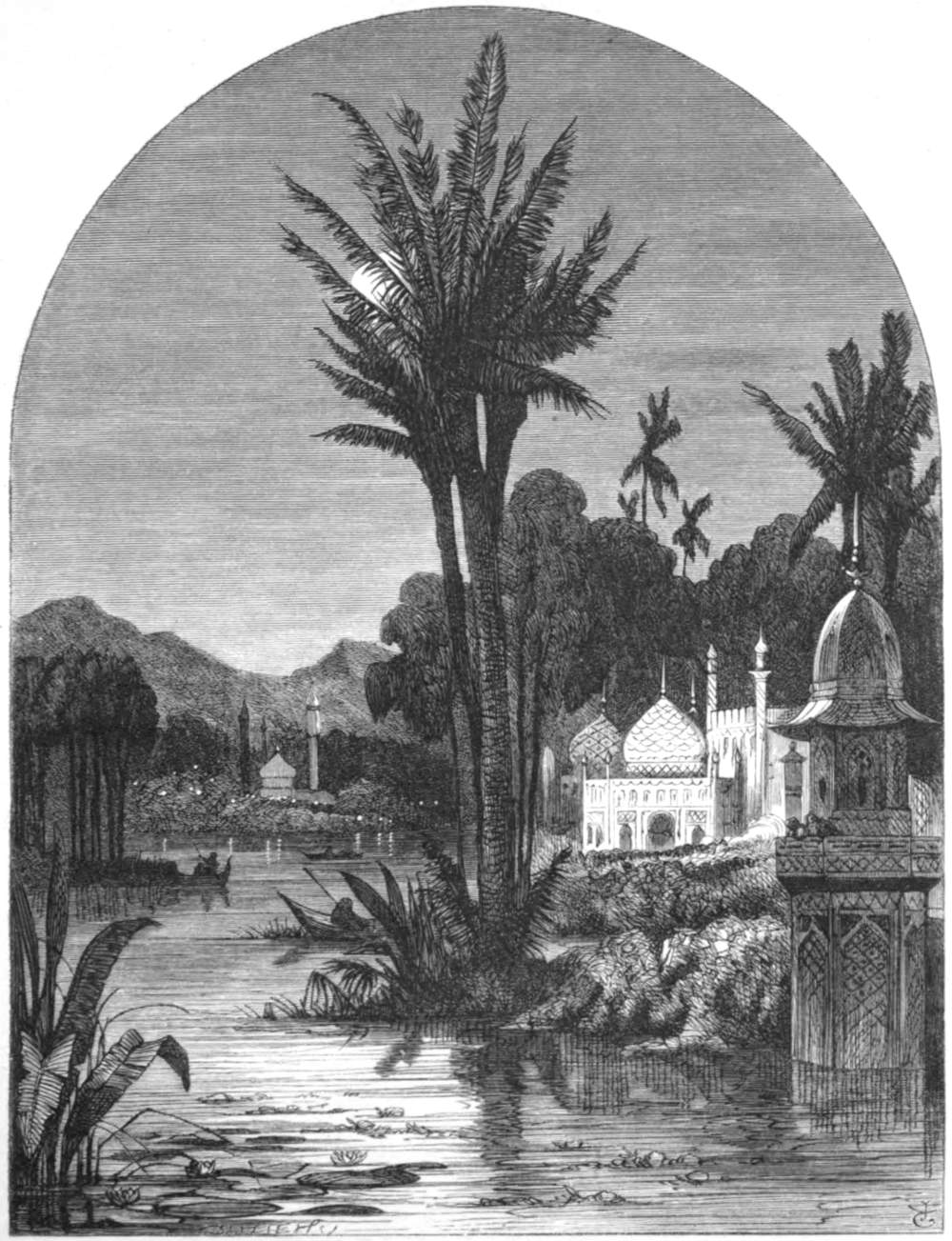

| Or to see it by moonlight,—when mellowly shines | |

| The light o’er its palaces, gardens, and shrines. | 285 |

| He saw, in the wreaths she would playfully snatch | |

| From the hedges, a glory his crown could not match. | 291 |

| Such cloud it is that now hangs over | |

| The heart of the Imperial Lover. | 295 |

| He heeds them not—one smile of hers | |

| Is worth a world of worshippers. | 297 |

| Fill’d with the cool, inspiring smell, | |

| The Enchantress now begins her spell. | 302 |

| No sooner was the flowery crown | |

| Plac’d on her head, than sleep came down. | 305 |

| That all stood hush’d and wondering, | |

| And turn’d and look’d into the air. | 315 |

| She whispers him with laughing eyes, | |

| “Remember, love, the Feast of Roses!” | 320 |

| They had now begun to ascend those barren mountains. | 321 |

| The marriage was fixed for the morning after her arrival. | 329 |

The Poem, or Romance, of Lalla Rookh, having now reached, I understand, its twentieth edition, a short account of the origin and progress of a work which has been hitherto so very fortunate in its course, may not be deemed, perhaps, superfluous or misplaced.

It was about the year 1812, that, far more through the encouraging suggestions of friends than from any confident promptings of my own ambition, I conceived the design of writing a Poem upon some Oriental subject, and of those quarto dimensions which Scott’s successful publications in that form had then rendered the regular poetical standard. A negotiation on the subject was opened with the Messrs. Longman in the same year; but, from some causes which I cannot now recollect, led to no decisive result; nor was it till a year or two after, that any further steps were taken xin the matter,—their house being the only one, it is right to add, with which, from first to last, I held any communication upon the subject.

On this last occasion, Mr. Perry kindly offered himself as my representative in the treaty; and, what with the friendly zeal of my negotiator on the one side, and the prompt and liberal spirit with which he was met on the other, there has seldom, I think, occurred any transaction in which Trade and Poesy have shone out so advantageously in each other’s eyes. The short discussion that then took place, between the two parties, may be comprised in a very few sentences. “I am of opinion,” said Mr. Perry,—enforcing his view of the case by arguments which it is not for me to cite,—“that Mr. Moore ought to receive for his Poem the largest price that has been given, in our day, for such a work.” “That was,” answered the Messrs. Longman, “three thousand guineas.” “Exactly so,” replied Mr. Perry, “and no less a sum ought he to receive.”

It was then objected, and very reasonably, on the part of the firm, that they had never yet seen a single line of the Poem; and that a perusal of the work ought to be allowed to them, before they embarked so large a sum in the purchase. But, no;—the romantic view which my friend, Perry, took of the matter, was, that this price should be given as a tribute to reputation xialready acquired, without any condition for a previous perusal of the new work. This high tone, I must confess, not a little startled and alarmed me; but, to the honour and glory of Romance,—as well on the publisher’s side as the poet’s,—this very generous view of the transaction was, without any difficulty, acceded to, and the firm agreed, before we separated, that I was to receive three thousand guineas for my Poem.

At the time of this agreement, but little of the work, as it stands at present, had yet been written. But the ready confidence in my success shown by others, made up for the deficiency of that requisite feeling, within myself; while a strong desire not wholly to disappoint this “auguring hope,” became almost a substitute for inspiration. In the year 1815, therefore, having made some progress in my task, I wrote to report the state of the work to the Messrs. Longman, adding, that I was now most willing and ready, should they desire it, to submit the manuscript for their consideration. Their answer to this offer was as follows:—“We are certainly impatient for the perusal of the Poem; but solely for our gratification. Your sentiments are always honourable.”[i]

I continued to pursue my task for another year, being likewise occasionally occupied with the Irish xiiMelodies, two or three numbers of which made their appearance, during the period employed in writing Lalla Rookh. At length, in the year 1816, I found my work sufficiently advanced to be placed in the hands of the publishers. But the state of distress to which England was reduced, in that dismal year, by the exhausting effects of the series of wars she had just then concluded, and the general embarrassment of all classes both agricultural and commercial, rendered it a juncture the least favourable that could well be conceived for the first launch into print of so light and costly a venture as Lalla Rookh. Feeling conscious, therefore, that under such circumstances, I should act but honestly in putting it in the power of the Messrs. Longman to reconsider the terms of their engagement with me,—leaving them free to postpone, modify, or even, should such be their wish, relinquish it altogether, I wrote them a letter to that effect, and received the following answer:—“We shall be most happy in the pleasure of seeing you in February. We agree with you, indeed, that the times are most inauspicious for ‘poetry and thousands;’ but we believe that your poetry would do more than that of any other living poet at the present moment.”[ii]

The length of time I employed in writing the few stories strung together in Lalla Rookh will appear, to xiiisome persons, much more than was necessary for the production of such easy and “light o’ love” fictions. But, besides that I have been, at all times, a far more slow and painstaking workman than would ever be guessed, I fear, from the result, I felt that, in this instance, I had taken upon myself a more than ordinary responsibility, from the immense stake risked by others on my chance of success. For a long time, therefore, after the agreement had been concluded, though generally at work with a view to this task, I made but very little real progress in it; and I have still by me the beginnings of several stories continued, some of them, to the length of three or four hundred lines, which, after in vain endeavouring to mould them into shape, I threw aside, like the tale of Cambuscan, “left half-told.” One of these stories, entitled The Peri’s Daughter, was meant to relate the loves of a nymph of this aërial extraction with a youth of mortal race, the rightful Prince of Ormuz, who had been, from his infancy, brought up in seclusion, on the banks of the river Amou, by an aged guardian named Mohassan. The story opens with the first meeting of these destined lovers, then in their childhood; the Peri having wafted her daughter to this holy retreat, in a bright, enchanted boat, whose first appearance is thus described:—

A song is sung by the Peri in approaching, of which the following forms a part:—

In another of these inchoate fragments, a proud female saint, named Banou, plays a principal part; and her progress through the streets of Cufa, on the night of a great illuminated festival, I find thus described:—

There are yet two more of these unfinished sketches, one of which extends to a much greater length than I was aware of; and, as far as I can judge from a hasty renewal of my acquaintance with it, is not incapable of being yet turned to account.

In only one of these unfinished sketches, the tale of The Peri’s Daughter, had I yet ventured to invoke that most home-felt of all my inspirations, which has lent to the story of The Fire-worshippers its main attraction and interest. That it was my intention, in the concealed Prince of Ormuz, to shadow out some impersonation of this feeling, I take for granted from the prophetic words supposed to be addressed to him by his aged guardian:—

In none of the other fragments do I find any trace of this sort of feeling, either in the subject or the personages of the intended story; and this was the reason, doubtless, though hardly known, at the time, to myself, that, finding my subjects so slow in kindling my own sympathies, I began to despair of their ever touching the hearts of others; and felt often inclined to say,

Had this series of disheartening experiments been carried on much further, I must have thrown aside the work in despair. But, at last, fortunately, as it proved, the thought occurred to me of founding a story on the fierce struggle so long maintained between the Ghebers,[iii] or ancient Fire-worshippers of Persia, and their haughty Moslem masters. From that moment, a new and deep interest in my whole task took possession of me. The xviiicause of tolerance was again my inspiring theme; and the spirit that had spoken in the melodies of Ireland soon found itself at home in the East.

Having thus laid open the secrets of the workshop to account for the time expended in writing this work, I must also, in justice to my own industry, notice the pains I took in long and laboriously reading for it. To form a store-house, as it were, of illustration purely Oriental, and so familiarise myself with its various treasures, that, as quick as Fancy required the aid of fact, in her spiritings, the memory was ready, like another Ariel, at her “strong bidding,” to furnish materials for the spellwork,—such was, for a long while, the sole object of my studies; and whatever time and trouble this preparatory process may have cost me, the effects resulting from it, as far as the humble merit of truthfulness is concerned, have been such as to repay me more than sufficiently for my pains. I have not forgotten how great was my pleasure, when told by the late Sir James Mackintosh, that he was once asked by Colonel W⸺s, the historian of British India, “whether it was true that Moore had never been in the East?” “Never,” answered Mackintosh. “Well, that shows me,” replied Colonel W⸺s, “that reading over D’Herbelot is as good as riding on the back of a camel.”

I need hardly subjoin to this lively speech, that xixalthough D’Herbelot’s valuable work was, of course, one of my manuals, I took the whole range of all such Oriental reading as was accessible to me; and became, for the time, indeed, far more conversant with all relating to that distant region, than I have ever been with the scenery, productions, or modes of life of any of those countries lying most within my reach. We know that D’Anville, though never in his life out of Paris, was able to correct a number of errors in a plan of the Troad taken by De Choiseul, on the spot; and, for my own very different, as well as far inferior, purposes, the knowledge I had thus acquired of distant localities, seen only by me in my day-dreams, was no less ready and useful.

An ample reward for all this painstaking has been found in such welcome tributes as I have just now cited; nor can I deny myself the gratification of citing a few more of the same description. From another distinguished authority on Eastern subjects, the late Sir John Malcolm, I had myself the pleasure of hearing a similar opinion publicly expressed;—that eminent person in a speech spoken by him at a Literary Fund Dinner, having remarked, that together with those qualities of a poet which he much too partially assigned to me was combined also “the truth of the historian.”

Sir William Ouseley, another high authority, in xxgiving his testimony to the same effect, thus notices an exception to the general accuracy for which he gives me credit:—“Dazzled by the beauties of this composition,[iv] few readers can perceive, and none surely can regret, that the poet, in his magnificent catastrophe, has forgotten, or boldly and most happily violated, the precept of Zoroaster, above noticed, which held it impious to consume any portion of a human body by fire, especially by that which glowed upon their altars.” Having long lost, I fear, most of my Eastern learning, I can only cite, in defence of my catastrophe, an old Oriental tradition, which relates, that Nimrod, when Abraham refused, at his command, to worship the fire, ordered him to be thrown into the midst of the flames.[v] A precedent so ancient for this sort of use of the worshipped element, would appear, for all purposes at least of poetry, fully sufficient.

In addition to these agreeable testimonies, I have also heard, and, need hardly add, with some pride and pleasure, that parts of this work have been rendered into Persian, and have found their way to Ispahan. To this fact, as I am willing to think it, allusion is made in some lively verses, written many years since, by my friend, Mr. Luttrell:—

That some knowledge of the work may have really reached that region, appears not improbable from a passage in the Travels of Mr. Frazer, who says, that “being delayed for some time at a town on the shores of the Caspian, he was lucky enough to be able to amuse himself with a copy of Lalla Rookh, which a Persian had lent him.”

Of the description of Balbec, in “Paradise and the Peri,” Mr. Carne, in his Letters from the East, thus speaks: “The description in Lalla Rookh of the plain and its ruins is exquisitely faithful. The minaret is on the declivity near at hand, and there wanted only the muezzin’s cry to break the silence.”

I shall now tax my reader’s patience with but one more of these generous vouchers. Whatever of vanity there may be in citing such tributes, they show, at least, of what great value, even in poetry, is that prosaic quality, industry; since, as the reader of the foregoing pages is now fully apprized, it was in a slow and laborious collection of small facts, that the first foundations of this fanciful Romance were laid.

The friendly testimony I have just referred to, appeared, some years since, in the form in which xxiiI now give it, and, if I recollect right, in the Athenæum:—

“I embrace this opportunity of bearing my individual testimony (if it be of any value) to the extraordinary accuracy of Mr. Moore, in his topographical, antiquarian, and characteristic details, whether of costume, manners, or less-changing monuments, both in his Lalla Rookh and in the Epicurean. It has been my fortune to read his Atlantic, Bermudean, and American Odes and Epistles, in the countries and among the people to which and to whom they related; I enjoyed also the exquisite delight of reading his Lalla Rookh, in Persia itself; and I have perused the Epicurean, while all my recollections of Egypt and its still existing wonders are as fresh as when I quitted the banks of the Nile for Arabia:—I owe it, therefore, as a debt of gratitude (though the payment is most inadequate), for the great pleasure I have derived from his productions, to bear my humble testimony to their local fidelity.

Among the incidents connected with this work, I must not omit to notice the splendid Divertissement, founded upon it, which was acted at the Château Royal of Berlin, during the visit of the Grand Duke Nicholas to that capital, in the year 1822. The different stories composing the work were represented in Tableaux Vivans and songs; and among the crowd of royal and noble personages engaged in the performances, I shall mention those only who represented the principal characters, and whom I find thus enumerated in the published account of the Divertissement.[vi]

| xxiii | ||

| “Fadladin, Grand-Nasir | Comte Haack (Maréchal de Cour.) | |

| Aliris, Roi de Bucharie | S. A. I. Le Grand Duc. | |

| Lalla Roûkh | S. A. I. Le Grande Duchesse. | |

| Aurungzeb, le Grand Mogol | { | S. A. R. Le Prince Guillaume, |

| { | frère du Roi. | |

| Abdallah, Père d’Aliris | S. A. R. Le Duc de Cumberland. | |

| La Reine, son épouse | { | S. A. R. La Princesse Louise |

| { | Radzivill.” | |

Besides these and other leading personages, there were also brought into action, under the various denominations of Seigneurs et Dames de Bucharie, Dames de Cachemire, Seigneurs et Dames dansans à la Fête des Roses, &c. nearly 150 persons.

Of the manner and style in which the Tableaux of the different stories are described in the work from which I cite, the following account of the performance of Paradise and the Peri will afford some specimen:—

“La décoration représentoit les portes brillantes du Paradis, entourées de nuages. Dans le premier tableau on voyoit la Péri, triste et desolée, couchée sur le seuil des portes fermées, et l’Ange de lumière qui lui addresse des consolations et des conseils. Le second représente le moment où la Péri, dans l’espoir que ce don lui ouvrira l’entrée du Paradis, recueille la dernière goutte de sang que vient de verser le jeune guerrier Indien.…

“La Péri et l’Ange de lumière répondoient pleinement à l’image et à l’idée qu’on est tenté de se faire de ces deux individus, et l’impression qu’a faite généralement xxivla suite des tableaux de cet épisode délicat et intéressant est loin de s’effacer de notre souvenir.”

In this grand Fête, it appears, originated the translation of Lalla Rookh into German[vii] verse, by the Baron de la Motte Fouqué; and the circumstances which led him to undertake the task, are described by himself in a Dedicatory Poem to the Empress of Russia, which he has prefixed to his translation. As soon as the performance, he tells us, had ended, Lalla Rookh (the Empress herself) exclaimed, with a sigh, “Is it, then, all over? are we now at the close of all that has given us so much delight? and lives there no poet who will impart to others, and to future times, some notion of the happiness we have enjoyed this evening?” On hearing this appeal, a Knight of Cashmere (who is no other than the poetical Baron himself) comes forward and promises to attempt to present to the world “the Poem itself in the measure of the original:”—whereupon Lalla Rookh, it is added, approvingly smiled.

i. April 10, 1815.

ii. November 9, 1816.

iii. Voltaire, in his tragedy of “Les Guèbres,” written with a similar under-current of meaning, was accused of having transformed his Fire-worshippers into Jansenists:—“Quelques figuristes,” he says, “prétendent que les Guèbres sont les jansénistes.”

iv. The Fire-worshippers.

v. “Tradunt autem Hebræi hanc fabulam quod Abraham in ignem missus sit quia ignem adorare noluit.”—St. Hieron. in Quæst. in Genesim.

vi. Lalla Roûkh Divertissement, mêlé de Chants et de Danses, Berlin, 1822. The work contains a series of coloured engravings, representing groups, processions, &c. in different Oriental costumes.

vii. Since this was written, another translation of Lalla Rookh into German verse has been made by Theodor Oelckers (Leipzig, Tauchnitz, Jun.), which has already passed through three editions.

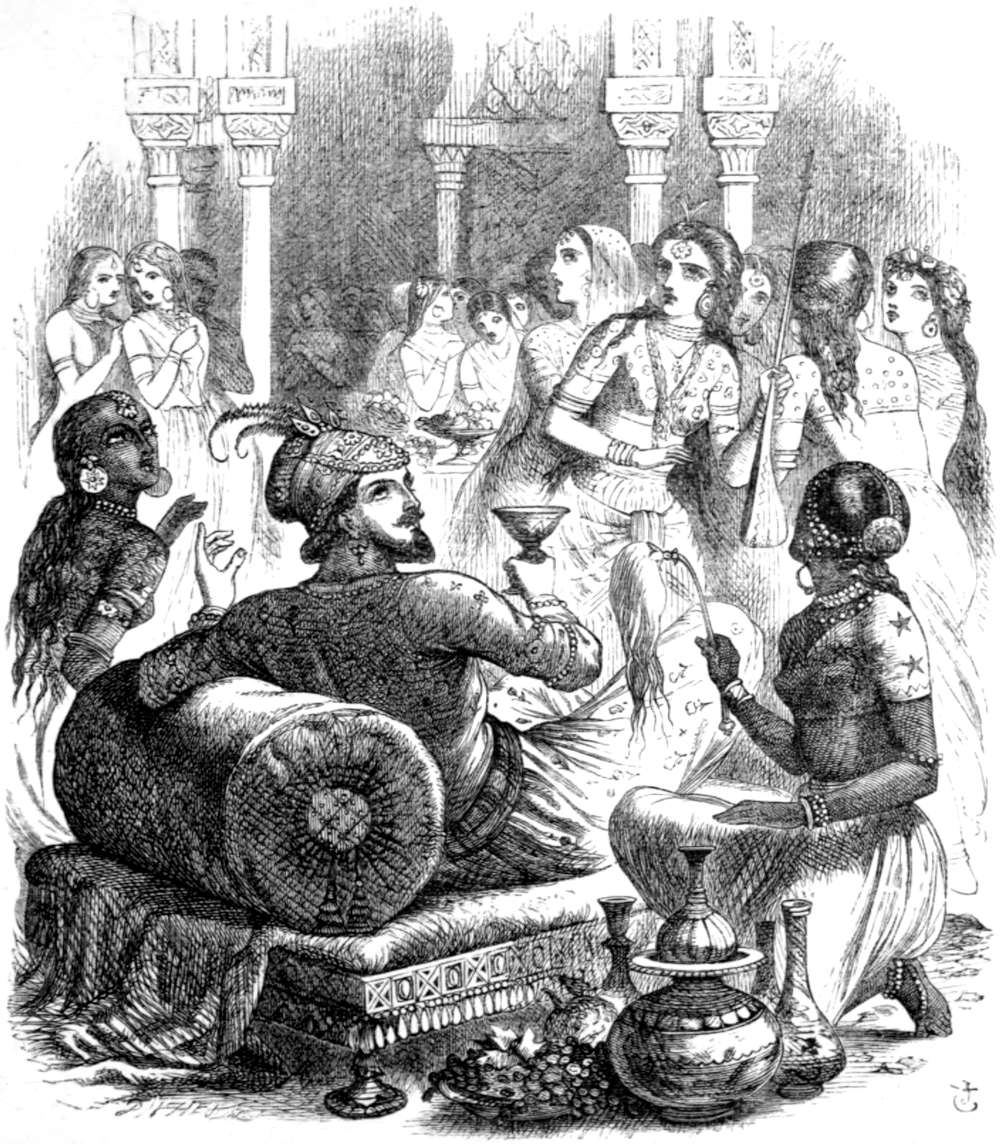

In the eleventh year of the reign of Aurungzebe, Abdalla, King of the Lesser Bucharia, a lineal descendant from the Great Zingis, having abdicated the throne in favour of his son, set out on a pilgrimage to the Shrine of the Prophet; and, passing into India through the delightful valley of Cashmere, rested for a short time at 2Delhi on his way. He was entertained by Aurungzebe in a style of magnificent hospitality, worthy alike of the visitor and the host, and was afterwards escorted with the same splendour to Surat, where he embarked for Arabia.[1] During the stay of the Royal Pilgrim at Delhi, a marriage was agreed upon between the Prince, his son, and the youngest daughter of the emperor, Lalla Rookh;[2]—a Princess described by the Poets of her time as more beautiful than Leila,[3] Shirine,[4] Dewildé,[5] or any of those heroines whose names and loves embellish the songs of Persia and Hindostan. It was intended that the nuptials should be celebrated at Cashmere; where the young King, as soon as the cares of empire would permit, was to meet, for the first time, his lovely bride, and, after a few months’ repose in that enchanting valley, conduct her over the snowy hills into Bucharia.

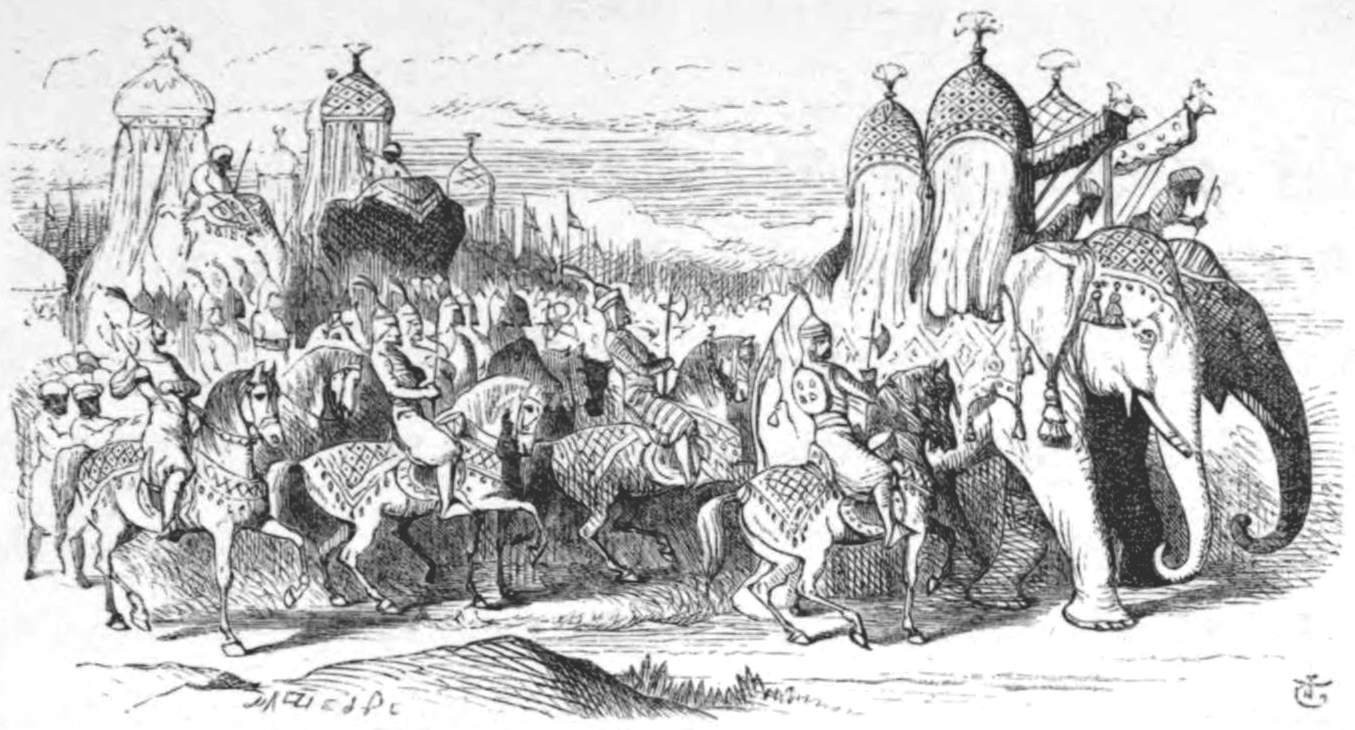

The day of Lalla Rookh’s departure from Delhi was as splendid as sunshine and pageantry could make it. The bazaars and baths were all covered with the richest tapestry; hundreds of gilded barges upon the Jumna floated with their banners shining in the water; while through the streets groups of beautiful children went strewing the most delicious flowers around, as in that Persian festival called the Scattering of the Roses;[6] till every part of the city was as fragrant as if a caravan 3of musk from Khoten had passed through it. The Princess, having taken leave of her kind father, who at parting hung a cornelian of Yemen round her neck, on which was inscribed a verse from the Koran, and having sent a considerable present to the Fakirs, who kept up the Perpetual Lamp in her sister’s tomb, meekly ascended the palankeen prepared for her; and, while Aurungzebe stood to take a last look from his balcony, the procession moved slowly on the road to Lahore.

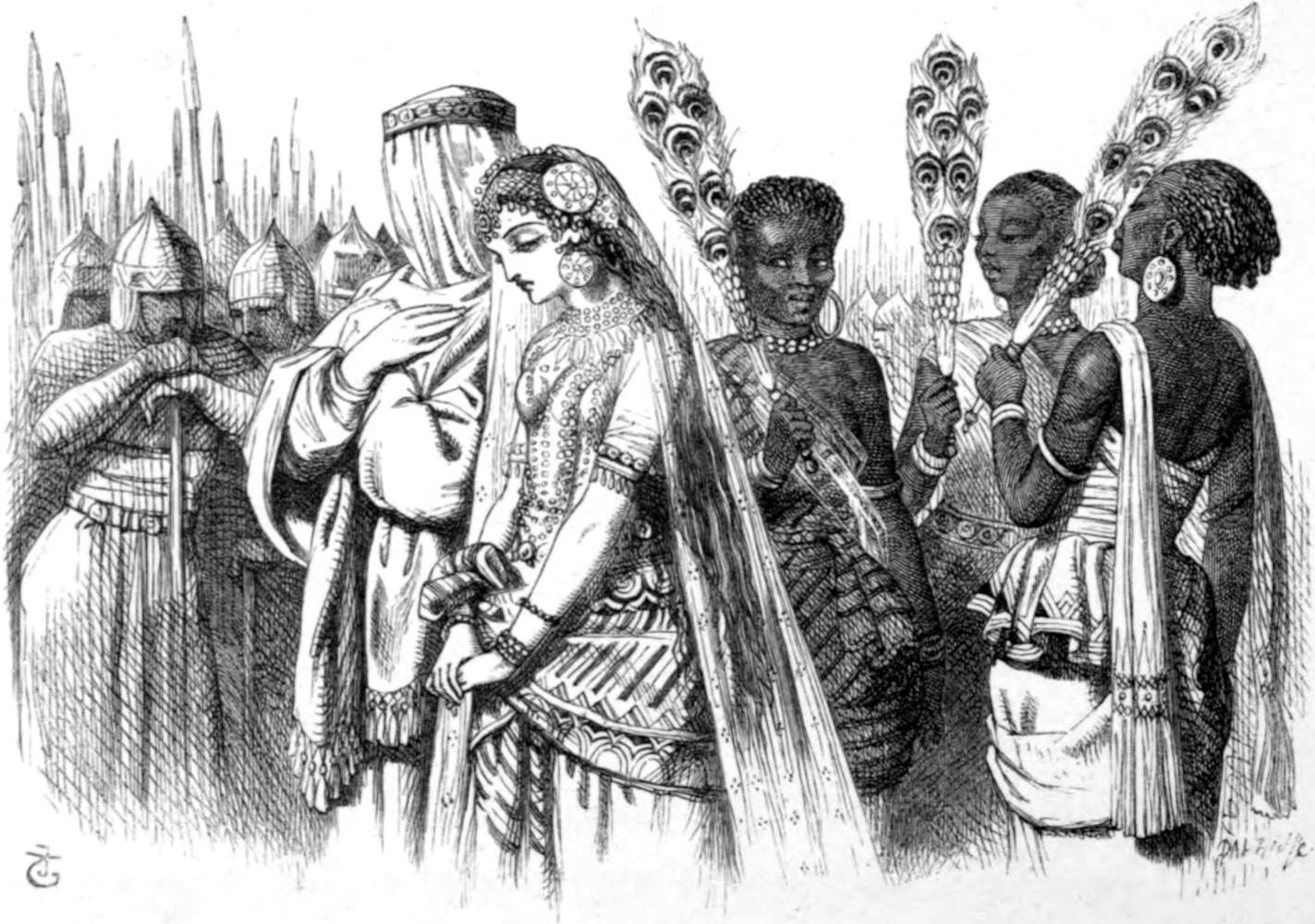

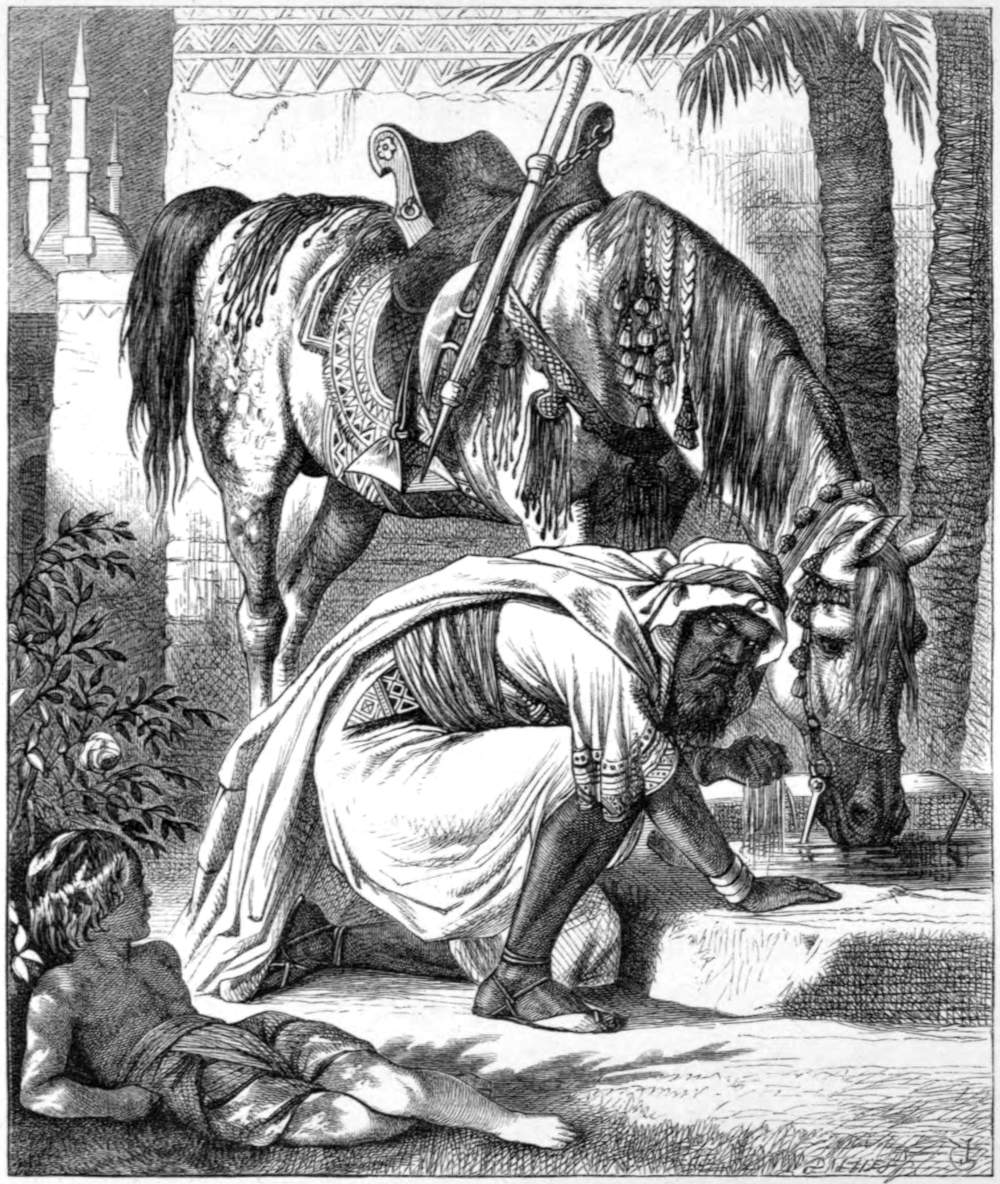

Seldom had the Eastern world seen a cavalcade so superb. From the gardens in the suburbs to the Imperial palace, it was one unbroken line of splendour. The gallant appearance of the Rajahs and Mogul Lords, distinguished by those insignia of the Emperor’s favour,[7] the feathers of the egret of Cashmere in their turbans, and the small silver-rimmed kettledrums at the bows of their saddles;—the costly armour of their cavaliers, who vied, on this occasion, with the guards of the great Keder Khan,[8] in the brightness of their silver battle-axes and the massiness of their maces of gold;—the glittering of the gilt pine-apples[9] on the tops of the palankeens;—the embroidered trappings of the elephants, bearing on their backs small turrets, in the shape of little antique temples, within which the Ladies of Lalla Rookh lay as it were enshrined;—the rose-coloured veils of the 4Princess’s own sumptuous litter,[10] at the front of which a fair young female slave sat fanning her through the curtains, with feathers of the Argus pheasant’s wing;[11]—and the lovely troop of Tartarian and Cashmerian maids of honour, whom the young King had sent to accompany his bride, and who rode on each side of the litter, upon small Arabian horses:—all was brilliant, tasteful, and magnificent, and pleased even the critical and fastidious Fadladeen, Great Nazir or Chamberlain of the Haram, who was borne in his palankeen immediately after the Princess, and considered himself not the least important personage of the pageant.

Fadladeen was a judge of everything,—from the pencilling of a Circassian’s eyelids to the deepest questions of science and literature; from the mixture of a conserve of rose-leaves to the composition of an epic poem: and such influence had his opinion upon the various tastes of the day, that all the cooks and poets of Delhi stood in awe of him. His political conduct and opinions were founded upon that line of Sadi,—“Should the Prince at noon-day say, It is night, declare that you behold the moon and stars.”—And his zeal for religion; of which Aurungzebe was a munificent protector,[12] was about as disinterested as that of the goldsmith who fell in love with the diamond eyes of the Idol of Jaghernaut.[13]

5During the first days of their journey, Lalla Rookh, who had passed all her life within the shadow of the Royal Gardens of Delhi,[14] found enough in the beauty of the scenery through which they passed to interest her mind, and delight her imagination; and when at evening, or in the heat of the day, they turned off from the high road to those retired and romantic places which had been selected for her encampments, sometimes on the banks of a small rivulet, as clear as the waters of the Lake of Pearl;[15] sometimes under the sacred shade of a Banyan tree, from which the view opened upon a glade covered with antelopes; and often in those hidden, embowered spots, described by one from the Isles of the West,[16] as “places of melancholy, delight, and safety, where all the company around was wild peacocks and turtle-doves;”—she felt a charm in these scenes, so lovely and so new to her, which, for a time, made her indifferent to every other amusement. But Lalla Rookh was young, and the young love variety; nor could the conversation of her Ladies and the great Chamberlain, Fadladeen, (the only persons, of course, admitted to her pavilion,) sufficiently enliven those many vacant hours, which were devoted neither to the pillow nor the palankeen. There was a little Persian slave who sung sweetly to the Vina, and who, now and then, lulled the Princess to sleep with the ancient ditties of her country, about the loves of Wamak and 6Ezra,[17] the fair-haired Zal and his mistress Rodahver;[18] not forgetting the combat of Rustam with the terrible White Demon.[19] At other times she was amused by those graceful dancing-girls of Delhi, who had been permitted by the Bramins of the Great Pagoda to attend her, much to the horror of the good Mussulman Fadladeen, who could see nothing graceful or agreeable in idolaters, and to whom the very tinkling of their golden anklets[20] was an abomination.

But these and many other diversions were repeated till they lost all their charm, and the nights and noondays were beginning to move heavily, when, at length, it was recollected that, among the attendants sent by the bridegroom, was a young poet of Cashmere, much celebrated throughout the valley for his manner of reciting the Stories of the East, on whom his Royal Master had conferred the privilege of being admitted to the pavilion of the Princess, that he might help to beguile the tediousness of the journey by some of his most agreeable recitals. At the mention of a poet, Fadladeen elevated his critical eyebrows, and, having refreshed his faculties with a dose of that delicious opium[21] which is distilled from the black poppy of the Thebais, gave orders for the minstrel to be forthwith introduced into the presence.

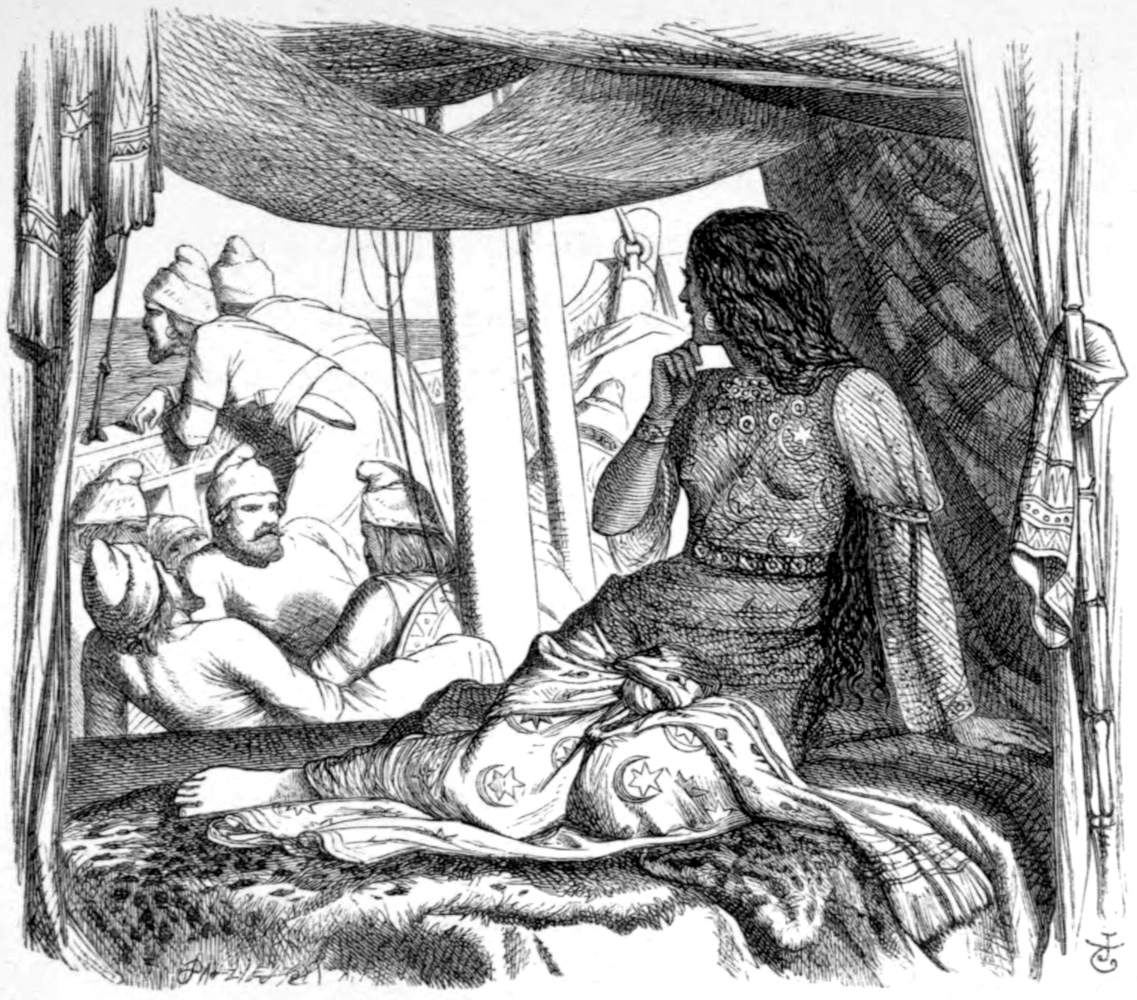

7The Princess, who had once in her life seen a poet from behind the screens of gauze in her Father’s hall, and had conceived from that specimen no very favourable ideas of the Caste, expected but little in this new exhibition to interest her;—she felt inclined, however, to alter her opinion on the very first appearance of Feramorz. He was a youth about Lalla Rookh’s own age, and graceful as that idol of women, Crishna,[22]—such as he appears to their young imaginations, heroic, beautiful, breathing music from his very eyes, and exalting the religion of his worshippers into love. His dress was simple, yet not without some marks of costliness; and the ladies of the Princess were not long in discovering that the cloth, which encircled his high Tartarian cap, was of the most delicate kind that the shawl-goats of Tibet supply.[23] Here and there, too, over his vest, which was confined by a flowered girdle of Kashan, hung strings of fine pearl, disposed with an air of studied negligence:—nor did the exquisite embroidery of his sandals escape the observation of these fair critics; who, however they might give way to Fadladeen upon the unimportant topics of religion and government, had the spirit of martyrs in every thing relating to such momentous matters as jewels and embroidery.

For the purpose of relieving the pauses of recitation by music, the young Cashmerian held in his hand a kitar;—such 8as, in old times, the Arab maids of the West used to listen to by moonlight in the gardens of the Alhambra—and, having premised, with much humility, that the story he was about to relate was founded on the adventures of that Veiled Prophet of Khorassan,[24] who, in the year of the Hegira 163, created such alarm throughout the Eastern Empire, made an obeisance to the Princess, and thus began:—

48On their arrival, next night, at the place of encampment, they were surprised and delighted to find the groves all around illuminated; some artists of Yamtcheou[58] having been sent on previously for the purpose. On each side of the green alley, which led to the Royal Pavilion, artificial sceneries of bamboo-work[59] were erected, representing arches, minarets, and towers, from which hung thousands of silken lanterns, painted by the most delicate pencils of Canton.—Nothing could be more beautiful than the leaves of the mango-trees and acacias, shining in the light of the bamboo-scenery, which shed a lustre round as soft as that of the nights of Peristan.

Lalla Rookh, however, who was too much occupied by the sad story of Zelica and her lover, to give a thought to anything else, except, perhaps, him who related it, hurried on through this scene of splendour to her pavilion,—greatly to the mortification of the poor artists of Yamtcheou,—and was followed with equal rapidity by the Great Chamberlain, cursing, as he went, that ancient Mandarin, whose parental anxiety in lighting 49up the shores of the lake, where his beloved daughter had wandered and been lost, was the origin of these fantastic Chinese illuminations.[60]

Without a moment’s delay, young Feramorz was introduced, and Fadladeen, who could never make up his mind as to the merits of a poet till he knew the religious sect to which he belonged, was about to ask him whether he was a Shia or a Sooni, when Lalla Rookh impatiently clapped her hands for silence, and the youth, being seated upon the musnud near her, proceeded:—

Lalla Rookh could think of nothing all day but the misery of these two young lovers. Her gaiety was gone, and she looked pensively even upon Fadladeen. She felt, too, without knowing why, a sort of uneasy pleasure in imagining that Azim must have been just such a youth as Feramorz; just as worthy to enjoy all the blessings, without any of the pangs, of that illusive passion which too often, like the sunny apples of Istkahar,[96] is all sweetness on one side, and all bitterness on the other.

82As they passed along a sequestered river after sunset, they saw a young Hindoo girl upon the bank,[97] whose employment seemed to them so strange, that they stopped their palankeens to observe her. She had lighted a small lamp, filled with oil of cocoa, and placing it in an earthen dish, adorned with a wreath of flowers, had committed it with a trembling hand to the stream; and was now anxiously watching its progress down the current, heedless of the gay cavalcade which had drawn up beside her. Lalla Rookh was all curiosity;—when one of her attendants, who had lived upon the banks of the Ganges (where this ceremony is so frequent, that often, in the dusk of the evening, the river is seen glittering all over with lights, like the Oton-tala, or Sea of Stars),[98] informed the Princess that it was the usual way, in which the friends of those who had gone on dangerous voyages offered up vows for their safe return. If the lamp sunk immediately, the omen was disastrous; but if it went shining down the stream, and continued to burn until entirely out of sight, the return of the beloved object was considered as certain.

Lalla Rookh, as they moved on, more than once looked back, to observe how the young Hindoo’s lamp proceeded; and, while she saw with pleasure that it was still unextinguished, she could not help fearing that all 83the hopes of this life were no better than that feeble light upon the river. The remainder of the journey was passed in silence. She now, for the first time, felt that shade of melancholy, which comes over the youthful maiden’s heart, as sweet and transient as her own breath upon a mirror; nor was it till she heard the lute of Feramorz, touched lightly at the door of her pavilion, that she waked from the reverie in which she had been wandering. Instantly her eyes were lighted up with pleasure; and after a few unheard remarks from Fadladeen, upon the indecorum of a poet seating himself in presence of a Princess, every thing was arranged as on the preceding evening and all listened with eagerness, while the story was thus continued:—

120The story of the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan being ended, they were now doomed to hear Fadladeen’s criticisms upon it. A series of disappointments and accidents had occurred to this learned Chamberlain during the journey. In the first place, those couriers stationed, as in the reign of Shah Jehan, between Delhi and the Western coast of India, to secure a constant supply of mangoes for the Royal Table, had, by some cruel irregularity, failed in their duty, and to eat any mangoes but those of Mazagong was, of course, impossible.[149] In the next place, the elephant, laden with his fine antique porcelain,[150] had, in an unusual fit of liveliness, shattered the whole set to pieces:—an irreparable loss, as many of the vessels were so exquisitely old, as to have been used under the Emperors Yan and Chun, who reigned many ages before the dynasty of Tang. His Koran, too, supposed to be the identical copy between the leaves of which Mahomet’s favourite pigeon used to nestle, had been mislaid by his Koran-bearer three whole days; not without much spiritual alarm to Fadladeen, who, though professing to hold with other loyal and orthodox Mussulmans, that salvation could only be found in the Koran, was strongly suspected of believing in his heart, that it could only be found in his own particular copy of it. When to all these grievances 121is added the obstinacy of the cooks, in putting the pepper of Canara into his dishes instead of the cinnamon of Serendib, we may easily suppose that he came to the task of criticism with, at least, a sufficient degree of irritability for the purpose.

“In order,” said he, importantly swinging about his chaplet of pearls, “to convey with clearness my opinion of the story this young man has related, it is necessary to take a review of all the stories that have ever⸺”—“My good Fadladeen!” exclaimed the Princess, interrupting him, “we really do not deserve that you should give yourself so much trouble. Your opinion of the poem we have just heard will, I have no doubt, be abundantly edifying, without any further waste of your valuable erudition.”—“If that be all,” replied the critic,—evidently mortified at not being allowed to show how much he knew about every thing but the subject immediately before him—“if that be all that is required, the matter is easily despatched.” He then proceeded to analyse the poem, in that strain (so well known to the unfortunate bards of Delhi), whose censures were an infliction from which few recovered, and whose very praises were like the honey extracted from the bitter flowers of the aloe. The chief personages of the story were, if he rightly understood them, an ill-favoured gentleman, with 122a veil over his face;—a young lady, whose reason went and came, according as it suited the poet’s convenience to be sensible or otherwise;—and a youth in one of those hideous Bucharian bonnets, who took the aforesaid gentleman in a veil for a Divinity. “From such materials,” said he, “what can be expected?—after rivalling each other in long speeches and absurdities, through some thousands of lines as indigestible as the filberts of Berdaa, our friend in the veil jumps into a tub of aquafortis; the young lady dies in a set speech, whose only recommendation is that it is her last; and the lover lives on to a good old age for the laudable purpose of seeing her ghost, which he at last happily accomplishes, and expires. This, you will allow, is a fair summary of the story; and if Nasser, the Arabian merchant, told no better,[151] our Holy Prophet (to whom be all honour and glory!) had no need to be jealous of his abilities for story-telling.”

With respect to the style, it was worthy of the matter;—it had not even those politic contrivances of structure, which make up for the commonness of the thoughts by the peculiarity of the manner, nor that stately poetical phraseology by which sentiments mean in themselves, like the blacksmith’s[152] apron converted into a banner, are so easily gilt and embroidered into consequence. Then, as to the versification, it was, to 123say no worse of it, execrable: it had neither the copious flow of Ferdosi, the sweetness of Hafez, nor the sententious march of Sadi; but appeared to him, in the uneasy heaviness of its movements, to have been modelled upon the gait of a very tired dromedary. The licences, too, in which it indulged, were unpardonable;—for instance, this line, and the poem abounded with such:—

“What critic that can count,” said Fadladeen, “and has his full complement of fingers to count withal, would tolerate for an instant such syllabic superfluities?” He here looked round, and discovered that most of his audience were asleep; while the glimmering lamps seemed inclined to follow their example. It became necessary, therefore, however painful to himself, to put an end to his valuable animadversions for the present, and he accordingly concluded, with an air of dignified candour, thus:—“Notwithstanding the observations which I have thought it my duty to make, it is by no means my wish to discourage the young man:—so far from it, indeed, that if he will but totally alter his style of writing and thinking, I have very little doubt that I shall be vastly pleased with him.”

Some days elapsed, after this harangue of the Great Chamberlain, before Lalla Rookh could venture to ask 124for another story. The youth was still a welcome guest in the pavilion—to one heart, perhaps, too dangerously welcome:—but all mention of poetry was, as if by common consent, avoided. Though none of the party had much respect for Fadladeen, yet his censures, thus magisterially delivered, evidently made an impression on them all. The Poet himself, to whom criticism was quite a new operation, (being wholly unknown in that Paradise of the Indies, Cashmere,) felt the shock as it is generally felt at first, till use has made it more tolerable to the patient;—the Ladies began to suspect that they ought not to be pleased, and seemed to conclude that there must have been much good sense in what Fadladeen said, from its having sent them all so soundly to sleep;—while the self-complacent Chamberlain was left to triumph in the idea of having, for the hundred and fiftieth time in his life, extinguished a Poet. Lalla Rookh alone—and Love knew why—persisted in being delighted with all she had heard, and in resolving to hear more as speedily as possible. Her manner, however, of first returning to the subject was unlucky. It was while they rested during the heat of noon near a fountain, on which some hand had rudely traced those well-known words from the Garden of Sadi,—“Many, like me, have viewed this fountain, but they are gone, and their eyes are closed for ever!”—that 125she took occasion, from the melancholy beauty of this passage, to dwell upon the charms of poetry in general. “It is true,” she said, “few poets can imitate that sublime bird, which flies always in the air, and never touches the earth:[153]—it is only once in many ages a Genius appears, whose words, like those on the Written Mountain, last for ever:[154] but still there are some, as delightful, perhaps, though not so wonderful, who, if not stars over our head, are at least flowers along our path, and whose sweetness of the moment we ought gratefully to inhale, without calling upon them for a brightness and a durability beyond their nature. In short,” continued she, blushing, as if conscious of being caught in an oration, “it is quite cruel that a poet cannot wander through his regions of enchantment, without having a critic for ever, like the old Man of the Sea, upon his back!”[155]—Fadladeen, it was plain, took this last luckless allusion to himself, and would treasure it up in his mind as a whetstone for his next criticism. A sudden silence ensued; and the Princess, glancing a look at Feramorz, saw plainly she must wait for a more courageous moment.

But the glories of Nature, and her wild fragrant airs, playing freshly over the current of youthful spirits, will soon heal even deeper wounds than the dull Fadladeens 126of this world can inflict. In an evening or two after, they came to the small Valley of Gardens, which had been planted by order of the Emperor, for his favourite sister Rochinara, during their progress to Cashmere, some years before; and never was there a more sparkling assemblage of sweets, since the Gulzar-e-Irem, or Rose-bower of Irem. Every precious flower was there to be found, that poetry, or love, or religion has ever consecrated; from the dark hyacinth, to which Hafez compares his mistress’s hair,[156] to the Cámalatá, by whose rosy blossoms the heaven of Indra is scented.[157] As they sat in the cool fragrance of this delicious spot, and Lalla Rookh remarked that she could fancy it the abode of that Flower-loving Nymph whom they worship in the temples of Kathay,[158] or of one of those Peris, those beautiful creatures of the air, who live upon perfumes, and to whom a place like this might make some amends for the Paradise they have lost,—the young Poet, in whose eyes she appeared, while she spoke, to be one of the bright spiritual creatures she was describing, said hesitatingly that he remembered a Story of a Peri, which, if the Princess had no objection, he would venture to relate. “It is,” said he, with an appealing look to Fadladeen, “in a lighter and humbler strain than the other:” then, striking a few careless but melancholy chords on his kitar, he thus began:—

155“And this,” said the Great Chamberlain, “is poetry! this flimsy manufacture of the brain, which, in comparison with the lofty and durable monuments of genius, is as the gold filigree-work of Zamara beside the eternal architecture of Egypt!” After this gorgeous sentence, which, with a few more of the same kind, Fadladeen kept by him for rare and important occasions, he proceeded to the anatomy of the short poem just recited. The lax and easy kind of metre in which it was written ought to be denounced, he said, as one of the leading causes of the alarming growth of poetry in our times. If some check were not given to this lawless facility, we should soon be over-run by a race of bards as numerous and as shallow as the hundred and twenty thousand Streams of Basra.[198] They who succeeded in this style deserved chastisement for their very success;—as warriors have been punished, even after gaining a victory, because they had taken the liberty of gaining it in an irregular or unestablished manner. What, then, was to be said to those who failed? to those who presumed, as in the present lamentable instance, to imitate the license and ease of the bolder sons of song, without any of that grace or vigour which gave a dignity even to negligence;—who, like them, flung the jereed[199] carelessly, but not, like them, to the mark;—“and who,” said he, raising his voice, to excite 156a proper degree of wakefulness in his hearers, “contrive to appear heavy and constrained in the midst of all the latitude they allow themselves, like one of those young pagans that dance before the Princess, who is ingenious enough to move as if her limbs were fettered, in a pair of the lightest and loosest drawers of Masulipatam!”

It was but little suitable, he continued, to the grave march of criticism to follow this fantastical Peri, of whom they had just heard, through all her flights and adventures between earth and heaven; but he could not help adverting to the puerile conceitedness of the Three Gifts which she is supposed to carry to the skies,—a drop of blood, forsooth, a sigh, and a tear! How the first of these articles was delivered into the Angel’s “radiant hand” he professed himself at a loss to discover; and as to the safe carriage of the sigh and the tear, such Peris and such poets were beings by far too incomprehensible for him even to guess how they managed such matters. “But, in short,” said he, “it is a waste of time and patience to dwell longer upon a thing so incurably frivolous,—puny even among its own puny race, and such as only the Banyan Hospital[200] for Sick Insects should undertake.”

In vain did Lalla Rookh try to soften this inexorable critic; in vain did she resort to her most eloquent 157common-places,—reminding him that poets were a timid and sensitive race, whose sweetness was not to be drawn forth, like that of the fragrant grass near the Ganges, by crushing and trampling upon them;[201]—that severity often extinguished every chance of the perfection which it demanded; and that, after all, perfection was like the Mountain of the Talisman,—no one had ever yet reached its summit.[202] Neither these gentle axioms, nor the still gentler looks with which they were inculcated, could lower for one instant the elevation of Fadladeen’s eyebrows, or charm him into any thing like encouragement, or even toleration, of her poet. Toleration, indeed, was not among the weaknesses of Fadladeen:—he carried the same spirit into matters of poetry and of religion, and, though little versed in the beauties or sublimities of either, was a perfect master of the art of persecution in both. His zeal was the same, too, in either pursuit; whether the game before him was pagans or poetasters,—worshippers of cows, or writers of epics.

They had now arrived at the splendid city of Lahore, whose mausoleums and shrines, magnificent and numberless, where Death appeared to share equal honours with Heaven, would have powerfully affected the heart and imagination of Lalla Rookh, if feelings more of this earth had not taken entire possession of her already. She 158was here met by messengers, despatched from Cashmere, who informed her that the King had arrived in the Valley, and was himself superintending the sumptuous preparations that were then making in the Saloons of the Shalimar for her reception. The chill she felt on receiving this intelligence,—which to a bride whose heart was free and light would have brought only images of affection and pleasure,—convinced her that her peace was gone for ever, and that she was in love, irretrievably in love, with young Feramorz. The veil had fallen off in which this passion at first disguises itself, and to know that she loved was now as painful as to love without knowing it had been delicious. Feramorz, too,—what misery would be his, if the sweet hours of intercourse so imprudently allowed them should have stolen into his heart the same fatal fascination as into hers;—if, notwithstanding her rank, and the modest homage he always paid to it, even he should have yielded to the influence of those long and happy interviews, where music, poetry, the delightful scenes of nature,—all had tended to bring their hearts close together, and to waken by every means that too ready passion, which often, like the young of the desert-bird, is warmed into life by the eyes alone![203] She saw but one way to preserve herself from being culpable as well as unhappy, and this, however painful, she was resolved to adopt. Feramorz must no more be admitted 159to her presence. To have strayed so far into the dangerous labyrinth was wrong, but to linger in it, while the clue was yet in her hand, would be criminal. Though the heart she had to offer to the King of Bucharia might be cold and broken, it should at least be pure; and she must only endeavour to forget the short dream of happiness she had enjoyed,—like that Arabian shepherd, who, in wandering into the wilderness, caught a glimpse of the Gardens of Irim, and then lost them again for ever![204]

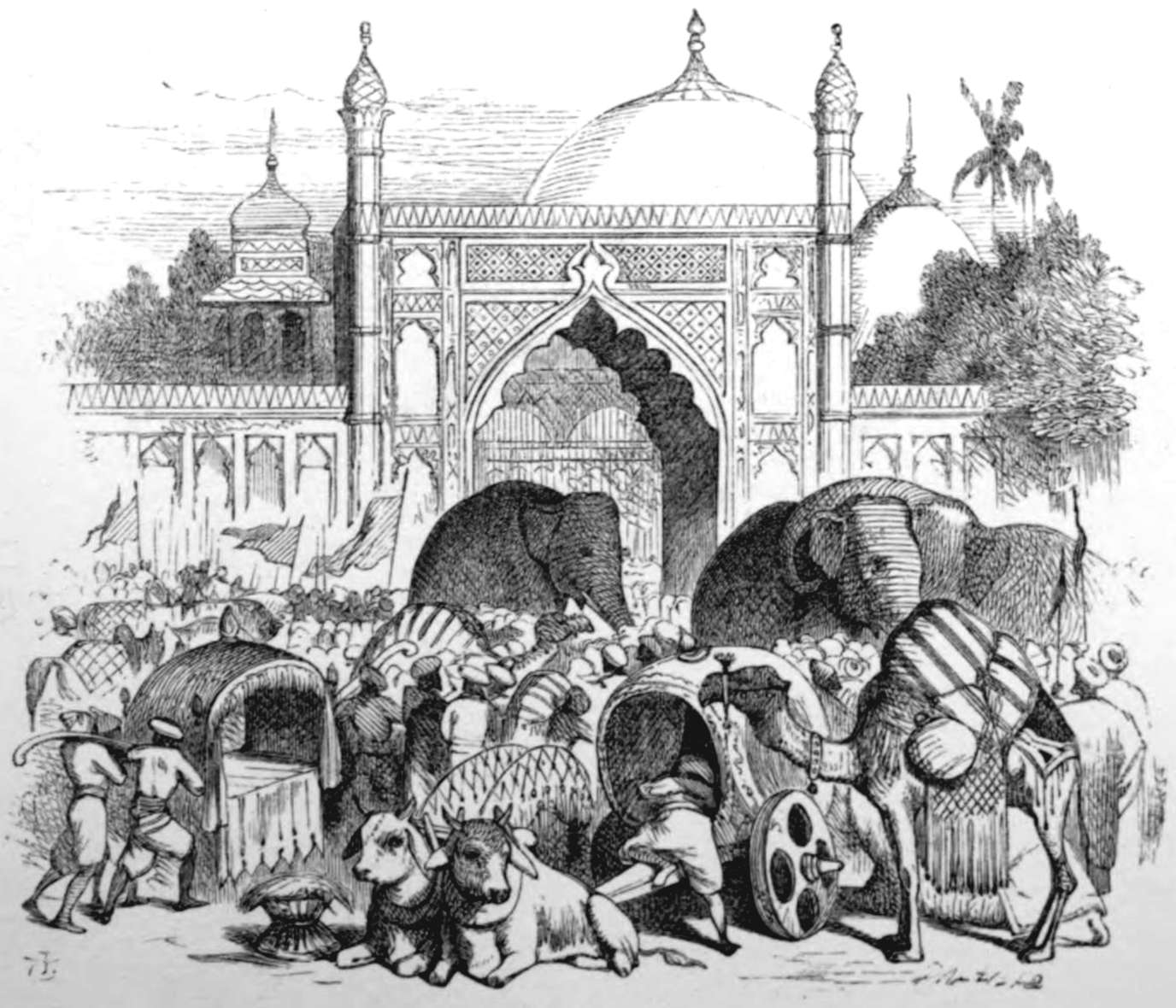

The arrival of the young Bride at Lahore was celebrated in the most enthusiastic manner. The Rajas and Omras in her train, who had kept at a certain distance during the journey, and never encamped nearer to the Princess than was strictly necessary for her safeguard, here rode in splendid cavalcade through the city, and distributed the most costly presents to the crowd. Engines were erected in all the squares, which cast forth showers of confectionery among the people; while the artisans, in chariots[205] adorned with tinsel and flying streamers, exhibited the badges of their respective trades through the streets. Such brilliant displays of life and pageantry among the palaces, and domes, and gilded minarets of Lahore, made the city altogether like a place of enchantment;—particularly on the day when Lalla Rookh set out again upon her journey, when she was accompanied to the gate by all 160the fairest and richest of the nobility, and rode along between ranks of beautiful boys and girls, who kept waving over their heads plates of gold and silver flowers,[206] and then threw them around to be gathered by the populace.

For many days after their departure from Lahore, a considerable degree of gloom hung over the whole party. Lalla Rookh, who had intended to make illness her excuse for not admitting the young minstrel, as usual, to the pavilion, soon found that to feign indisposition was unnecessary;—Fadladeen felt the loss of the good road they had hitherto travelled, and was very near cursing Jehan-Guire (of blessed memory!) for not having continued his delectable alley of trees,[207] at least as far as the mountains of Cashmere;—while the Ladies, who had nothing now to do all day but to be fanned by peacocks’ feathers and listen to Fadladeen, seemed heartily weary of the life they led, and, in spite of all the Great Chamberlain’s criticisms, were so tasteless as to wish for the poet again. One evening, as they were proceeding to their place of rest for the night, the Princess, who, for the freer enjoyment of the air, had mounted her favourite Arabian palfrey, in passing by a small grove, heard the notes of a lute from within its leaves, and a voice, which she but too well knew, singing the following words:—

The tone of melancholy defiance in which these words were uttered, went to Lalla Rookh’s heart;—and, as she reluctantly rode on, she could not help feeling it to 162be a sad but still sweet certainty, that Feramorz was to the full as enamoured and miserable as herself.

The place where they encamped that evening was the first delightful spot they had come to since they left Lahore. On one side of them was a grove full of small Hindoo temples, and planted with the most graceful trees of the East; where the tamarind, the cassia, and the silken plantains of Ceylon were mingled in rich contrast with the high fanlike foliage of the Palmyra,—that favourite tree of the luxurious bird that lights up the chambers of its nest with fire-flies.[208] In the middle of the lawn where the pavilion stood there was a tank surrounded by small mangoe-trees, on the clear cold waters of which floated multitudes of the beautiful red lotus;[209] while at a distance stood the ruins of a strange and awful-looking tower, which seemed old enough to have been the temple of some religion no longer known, and which spoke the voice of desolation in the midst of all that bloom and loveliness. This singular ruin excited the wonder and conjectures of all. Lalla Rookh guessed in vain, and the all-pretending Fadladeen, who had never till this journey been beyond the precincts of Delhi, was proceeding most learnedly to show that he knew nothing whatever about the matter, when one of the Ladies suggested that perhaps Feramorz could satisfy 163their curiosity. They were now approaching his native mountains, and this tower might perhaps be a relic of some of those dark superstitions, which had prevailed in that country before the light of Islam dawned upon it. The Chamberlain, who usually preferred his own ignorance to the best knowledge that any one else could give him, was by no means pleased with this officious reference; and the Princess, too, was about to interpose a faint word of objection, but, before either of them could speak, a slave was despatched for Feramorz, who, in a very few minutes, made his appearance before them—looking so pale and unhappy in Lalla Rookh’s eyes, that she repented already of her cruelty in having so long excluded him.

That venerable tower, he told them, was the remains of an ancient Fire-temple, built by those Ghebers or Persians of the old religion, who, many hundred years since, had fled hither from their Arab conquerors,[210] preferring liberty and their altars in a foreign land to the alternative of apostasy or persecution in their own. It was impossible, he added, not to feel interested in the many glorious but unsuccessful struggles, which had been made by these original natives of Persia to cast off the yoke of their bigoted conquerors. Like their own Fire in the Burning Field at Bakou,[211] when suppressed in 164one place, they had but broken out with fresh flame in another; and, as a native of Cashmere, of that fair and Holy Valley, which had in the same manner become the prey of strangers,[212] and seen her ancient shrines and native princes swept away before the march of her intolerant invaders, he felt a sympathy, he owned, with the sufferings of the persecuted Ghebers, which every monument like this before them but tended more powerfully to awaken.

It was the first time that Feramorz had ever ventured upon so much prose before Fadladeen, and it may easily be conceived what effect such prose as this must have produced upon that most orthodox and most pagan-hating personage. He sat for some minutes aghast, ejaculating only at intervals, “Bigoted conquerors!—sympathy with Fire-worshippers!”[213]—while Feramorz, happy to take advantage of this almost speechless horror of the Chamberlain, proceeded to say that he knew a melancholy story, connected with the events of one of those struggles of the brave Fire-worshippers against their Arab masters, which, if the evening was not too far advanced, he should have much pleasure in being allowed to relate to the Princess. It was impossible for Lalla Rookh to refuse;—he had never before looked half so animated; and when he spoke of the Holy Valley his 165eyes had sparkled, she thought, like the talismanic characters on the scimitar of Solomon. Her consent was therefore most readily granted; and while Fadladeen sat in unspeakable dismay, expecting treason and abomination in every line, the poet thus began his story of the Fire-worshippers:—

190The Princess, whose heart was sad enough already, could have wished that Feramorz had chosen a less melancholy story; as it is only to the happy that tears are a luxury. Her Ladies, however, were by no means sorry that love was once more the Poet’s theme; for, whenever he spoke of love, they said, his voice was as sweet as if he had chewed the leaves of that enchanted tree, which grows over the tomb of the musician, Tan-Sein.[235]

Their road all the morning had lain through a very dreary country;—through valleys, covered with a low bushy jungle, where, in more than one place, the awful signal of the bamboo staff,[236] with the white flag at its top, reminded the traveller that, in that very spot, the tiger had made some human creature his victim. It was, therefore, with much pleasure that they arrived at sunset in a safe and lovely glen, and encamped under one of those holy trees, whose smooth columns and spreading roofs seem to destine them for natural temples of religion. Beneath this spacious shade, some pious hands had erected a row of pillars ornamented with the most beautiful porcelain,[237] which now supplied the use 191of mirrors to the young maidens, as they adjusted their hair in descending from the palankeens. Here, while, as usual, the Princess sat listening anxiously, with Fadladeen in one of his loftiest moods of criticism by her side, the young Poet, leaning against a branch of the tree, thus continued his story:—

215Lalla Rookh had, the night before, been visited by a dream which, in spite of the impending fate of poor Hafed, made her heart more than usually cheerful during the morning, and gave her cheeks all the freshened animation of a flower that the Bid-musk had just passed over.[266] She fancied that she was sailing on that Eastern Ocean, where the sea-gipsies, who live for ever on the water,[267] enjoy a perpetual summer in wandering from isle to isle, when she saw a small gilded bark approaching her. It was like one of those boats which the Maldivian islanders send adrift, at the mercy of winds and waves, loaded with perfumes, flowers, and odoriferous wood, as an offering to the Spirit whom they call King of the Sea. At first, this little bark appeared to be empty, but, on coming nearer⸺

She had proceeded thus far in relating the dream to her Ladies, when Feramorz appeared at the door of the pavilion. In his presence, of course, every thing else was forgotten, and the continuance of the story was instantly requested by all. Fresh wood of aloes was set to burn in the cassolets;—the violet sherbets[268] were hastily handed round, and after a short prelude on his lute, in the pathetic measure of Nava,[269] which is always used to express the lamentations of absent lovers, the Poet thus continued:—

237The next evening Lalla Rookh was entreated by her Ladies to continue the relation of her wonderful dream; but the fearful interest that hung round the fate of Hinda and her lover had completely removed every trace of it from her mind;—much to the disappointment of a fair seer or two in her train, who prided themselves on their skill in interpreting visions, and who had already remarked, as an unlucky omen, that the Princess, on the very morning after the dream, had worn a silk dyed with the blossoms of the sorrowful tree, Nilica.[284]

Fadladeen, whose indignation had more than once broken out during the recital of some parts of this heterodox poem, seemed at length to have made up his mind to the infliction; and took his seat this evening with all the patience of a martyr, while the Poet resumed his profane and seditious story as follows:—

278The singular placidity with which Fadladeen had listened, during the latter part of this obnoxious story, surprised the Princess and Feramorz exceedingly; and even inclined towards him the hearts of these unsuspicious young persons, who little knew the source of a complacency so marvellous. The truth was, he had been organising, for the last few days, a most notable plan of persecution against the poet, in consequence of some passages that had fallen from him on the second evening of recital,—which appeared to this worthy Chamberlain to contain language and principles, for which nothing short of the summary criticism of the Chabuk[301] would be advisable. It was his intention, therefore, immediately on their arrival at Cashmere, to give information to the King of Bucharia of the very dangerous sentiments of his minstrel; and if, unfortunately, that monarch did not act with suitable vigour on the occasion, (that is, if he did not give the Chabuk to Feramorz, and a place to Fadladeen,) there would be an end, he feared, of all legitimate government in Bucharia. He could not help, however, auguring better both for himself and the cause of potentates in general; and it was the pleasure arising from these mingled anticipations that diffused such unusual satisfaction through his features, and made his eyes shine out, like poppies of the desert, over the wide and lifeless wilderness of that countenance.

279Having decided upon the Poet’s chastisement in this manner, he thought it but humanity to spare him the minor tortures of criticism. Accordingly, when they assembled the following evening in the pavilion, and Lalla Rookh was expecting to see all the beauties of her bard melt away, one by one, in the acidity of criticism, like pearls in the cup of the Egyptian queen,—he agreeably disappointed her, by merely saying, with an ironical smile, that the merits of such a poem deserved to be tried at a much higher tribunal; and then suddenly passed off into a panegyric upon all Mussulman sovereigns, more particularly his august and Imperial master, Aurungzebe,—the wisest and best of the descendants of Timur,—who, among other great things he had done for mankind, had given to him, Fadladeen, the very profitable posts of Betel-carrier, and Taster of Sherbets to the Emperor, Chief Holder of the Girdle of Beautiful Forms,[302] and Grand Nazir, or Chamberlain of the Haram.

They were now not far from that Forbidden River,[303] beyond which no pure Hindoo can pass; and were reposing for a time in the rich valley of Hussun Abdaul, which had always been a favourite resting-place of the Emperors in their annual migrations to Cashmere. Here often had the Light of the Faith, Jehan-Guire, been known to wander with his beloved and beautiful Nourmahal: and 280here would Lalla Rookh have been happy to remain for ever, giving up the throne of Bucharia and the world, for Feramorz and love in this sweet, lonely valley. But the time was now fast approaching when she must see him no longer,—or, what was still worse, behold him with eyes whose every look belonged to another; and there was a melancholy preciousness in these last moments, which made her heart cling to them as it would to life. During the latter paid of the journey, indeed, she had sunk into a deep sadness, from which nothing but the presence of the young minstrel could awake her. Like those lamps in tombs, which only light up when the air is admitted, it was only at his approach that her eyes became smiling and animated. But here, in this dear valley, every moment appeared an age of pleasure; she saw him all day, and was, therefore, all day happy,—resembling, she often thought, that people of Zinge, who attribute the unfading cheerfulness they enjoy to one genial star that rises nightly over their heads.[304]

The whole party, indeed, seemed in their liveliest mood during the few days they passed in this delightful solitude. The young attendants of the Princess, who were here allowed a much freer range than they could safely be indulged with in a less sequestered place, ran wild among the gardens and bounded through the meadows, lightly 281as young roes over the aromatic plains of Tibet. While Fadladeen, in addition to the spiritual comfort derived by him from a pilgrimage to the tomb of the Saint from whom the valley is named, had also opportunities of indulging, in a small way, his taste for victims, by putting to death some hundreds of those unfortunate little lizards,[305] which all pious Mussulmans make it a point to kill;—taking for granted, that the manner in which the creature hangs its head is meant as a mimicry of the attitude in which the Faithful say their prayers.

About two miles from Hussun Abdaul were those Royal Gardens,[306] which had grown beautiful under the care of so many lovely eyes, and were beautiful still, though those eyes could see them no longer. This place, with its flowers, and its holy silence, interrupted only by the dipping of the wings of birds in its marble basins filled with the pure water of those hills, was to Lalla Rookh all that her heart could fancy of fragrance, coolness, and almost heavenly tranquillity. As the Prophet said of Damascus, “it was too delicious;”[307]—and here, in listening to the sweet voice of Feramorz, or reading in his eyes what yet he never dared to tell her, the most exquisite moments of her whole life were passed. One evening, when they had been talking of the Sultana Nourmahal, the Light of the Haram,[308] who had so often 282wandered among these flowers, and fed with her own hands, in those marble basins, the small shining fishes of which she was so fond,[309]—the youth, in order to delay the moment of separation, proposed to recite a short story, or rather rhapsody, of which this adored Sultana was the heroine. It related, he said, to the reconcilement of a sort of lovers’ quarrel which took place between her and the Emperor during a Feast of Roses at Cashmere; and would remind the Princess of that difference between Haroun-al-Raschid and his fair mistress Marida,[310] which was so happily made up by the soft strains of the musician, Moussali. As the story was chiefly to be told in song, and Feramorz had unluckily forgotten his own lute in the valley, he borrowed the vina of Lalla Rookh’s little Persian slave, and thus began:—

Fadladeen, at the conclusion of this light rhapsody, took occasion to sum up his opinion of the young Cashmerian’s poetry,—of which, he trusted, they had that evening heard the last. Having recapitulated the epithets, “frivolous”—“inharmonious”—“nonsensical,” he proceeded to say that, viewing it in the most favourable light, it resembled one of those Maldivian boats, to which the Princess had alluded in the relation of her dream,[378]—a slight, gilded thing, sent adrift without rudder or ballast, and with nothing but vapid sweets and faded flowers on board. The profusion, indeed, of flowers and birds, which this poet had ready on all occasions,—not to mention dews, gems, &c.—was a most oppressive kind of opulence to his hearers; and had the unlucky effect of giving to his style all the glitter of the flower-garden without its method, and all the flutter of the aviary without its song. In addition to this, he chose his subjects badly, and was always most inspired by the worst 322parts of them. The charms of paganism, the merits of rebellion,—these were the themes honoured with his particular enthusiasm; and, in the poem just recited, one of his most palatable passages was in praise of that beverage of the Unfaithful, wine;—“being, perhaps,” said he, relaxing into a smile, as conscious of his own character in the Haram on this point, “one of those bards, whose fancy owes all its illumination to the grape, like that painted porcelain,[379] so curious and so rare, whose images are only visible when liquor is poured into it.” Upon the whole, it was his opinion, from the specimens which they had heard, and which, he begged to say, were the most tiresome part of the journey, that—whatever other merits this well-dressed young gentleman might possess—poetry was by no means his proper avocation: “and indeed,” concluded the critic, “from his fondness for flowers and for birds, I would venture to suggest that a florist or a bird-catcher is a much more suitable calling for him than a poet.”

They had now begun to ascend those barren mountains, which separate Cashmere from the rest of India; and, as the heats were intolerable, and the time of their encampments limited to the few hours necessary for refreshment and repose, there was an end to all their delightful evenings, and Lalla Rookh saw no 323more of Feramorz. She now felt that her short dream of happiness was over, and that she had nothing but the recollection of its few blissful hours, like the one draught of sweet water that serves the camel across the wilderness, to be her heart’s refreshment during the dreary waste of life that was before her. The blight that had fallen upon her spirits soon found its way to her cheek, and her ladies saw with regret—though not without some suspicion of the cause—that the beauty of their mistress, of which they were almost as proud as of their own, was fast vanishing away at the very moment of all when she had most need of it. What must the King of Bucharia feel, when, instead of the lively and beautiful Lalla Rookh, whom the poets of Delhi had described as more perfect than the divinest images in the house of Azor,[380] he should receive a pale and inanimate victim, upon whose cheek neither health nor pleasure bloomed, and from whose eyes Love had fled,—to hide himself in her heart?

If anything could have charmed away the melancholy of her spirits, it would have been the fresh airs and enchanting scenery of that Valley, which the Persians so justly call the Unequalled.[381] But neither the coolness of its atmosphere, so luxurious after toiling up those bare and burning mountains,—neither the splendour of the 324minarets and pagodas, that shone out from the depth of its woods, nor the grottos, hermitages, and miraculous fountains,[382] which make every spot of that region holy ground,—neither the countless waterfalls, that rush into the Valley from all those high and romantic mountains that encircle it, nor the fair city on the Lake, whose houses, roofed with flowers,[383] appeared at a distance like one vast and variegated parterre;—not all these wonders and glories of the most lovely country under the sun could steal her heart for a minute from those sad thoughts, which but darkened, and grew bitterer every step she advanced.

The gay pomps and processions that met her upon her entrance into the Valley, and the magnificence with which the roads all along were decorated, did honour to the taste and gallantry of the young King. It was night when they approached the city, and, for the last two miles, they had passed under arches, thrown from hedge to hedge, festooned with only those rarest roses from which the Attar Gul, more precious than gold, is distilled, and illuminated in rich and fanciful forms with lanterns of the triple-coloured tortoise-shell of Pegu.[384] Sometimes, from a dark wood by the side of the road, a display of fire-works would break out, so sudden and so brilliant, that a Brahmin might fancy he beheld that grove, in whose purple shade 325the God of Battles was born, bursting into a flame at the moment of his birth;—while, at other times, a quick and playful irradiation continued to brighten all the fields and gardens by which they passed, forming a line of dancing lights along the horizon; like the meteors of the north as they are seen by those hunters,[385] who pursue the white and blue foxes on the confines of the Icy Sea.

These arches and fire-works delighted the Ladies of the Princess exceedingly; and, with their usual good logic, they deduced from his taste for illuminations, that the King of Bucharia would make the most exemplary husband imaginable. Nor, indeed, could Lalla Rookh herself help feeling the kindness and splendour with which the young bridegroom welcomed her;—but she also felt how painful is the gratitude, which kindness from those we cannot love excites; and that their best blandishments come over the heart with all that chilling and deadly sweetness, which we can fancy in the cold, odoriferous wind[386] that is to blow over this earth in the last days.

The marriage was fixed for the morning after her arrival, when she was, for the first time, to be presented to the monarch in that Imperial Palace beyond the lake, called the Shalimar. Though never before had a night 326of more wakeful and anxious thought been passed in the Happy Valley, yet, when she rose in the morning, and her Ladies came around her, to assist in the adjustment of the bridal ornaments, they thought they had never seen her look half so beautiful. What she had lost of the bloom and radiancy of her charms was more than made up by that intellectual expression, that soul beaming forth from the eyes, which is worth all the rest of loveliness. When they had tinged her fingers with the Henna leaf, and placed upon her brow a small coronet of jewels, of the shape worn by the ancient Queens of Bucharia, they flung over her head the rose-coloured bridal veil, and she proceeded to the barge that was to convey her across the lake;—first kissing, with a mournful look, the little amulet of cornelian, which her father at parting had hung about her neck.

The morning was as fresh and fair as the maid on whose nuptials it rose, and the shining lake, all covered with boats, the minstrels playing upon the shores of the islands, and the crowded summer-houses on the green hills around, with shawls and banners waving from their roofs, presented such a picture of animated rejoicing, as only she, who was the object of it all, did not feel with transport. To Lalla Rookh alone it was a melancholy pageant; nor could she have even borne to look 327upon the scene, were it not for a hope that, among the crowds around, she might once more perhaps catch a glimpse of Feramorz. So much was her imagination haunted by this thought, that there was scarcely an islet or boat she passed on the way, at which her heart did not flutter with the momentary fancy that he was there. Happy, in her eyes, the humblest slave upon whom the light of his dear looks fell!—In the barge immediately after the Princess sat Fadladeen, with his silken curtains thrown widely apart, that all might have the benefit of his august presence, and with his head full of the speech he was to deliver to the King, “concerning Feramorz, and literature, and the Chabuk, as connected therewith.”