Title: Minor tactics of the chalk stream and kindred studies

Author: G. E. M. Skues

Release date: August 31, 2025 [eBook #76776]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Adam and Charles Black, 1914

Credits: Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

| AMERICA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, NEW YORK |

| AUSTRALASIA | OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 205 Flinders Lane, MELBOURNE |

| CANADA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA, LTD. St. Martin’s House, 70 Bond Street, TORONTO |

| INDIA | MACMILLAN & COMPANY, LTD. Macmillan Building, BOMBAY 309 Bow Bazaar Street, CALCUTTA |

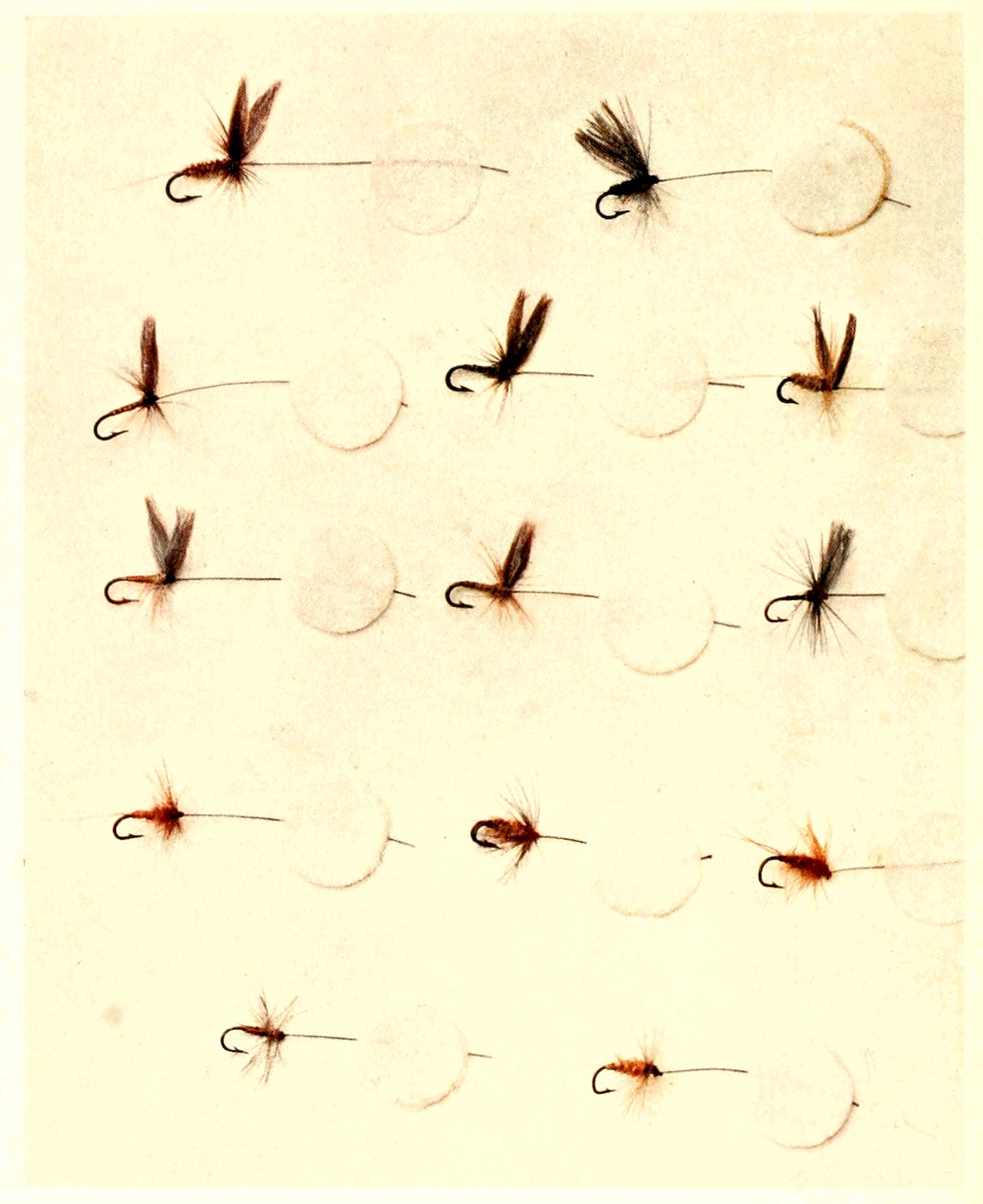

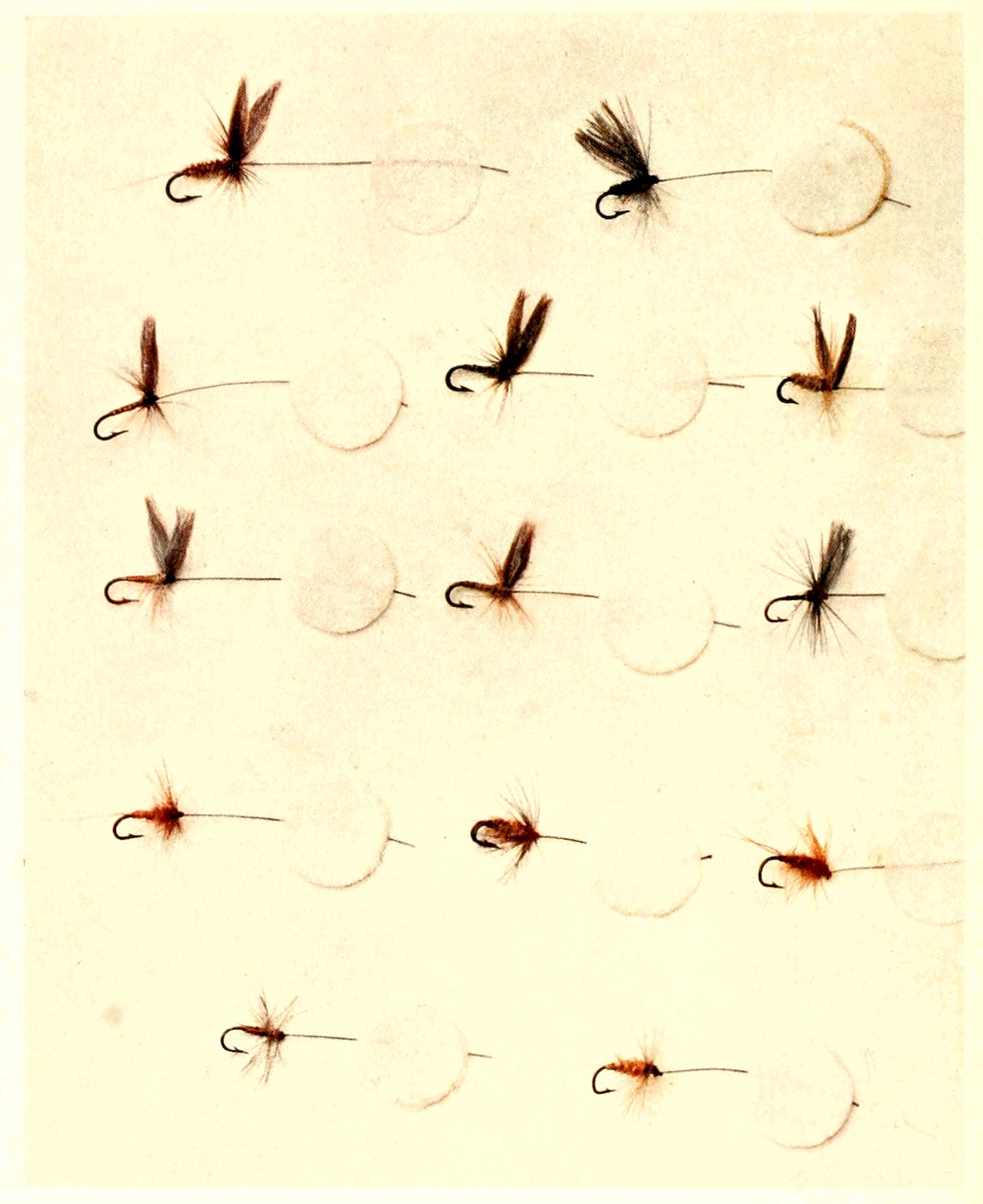

| Rough Spring Olive. No. 1. |

Iron Blue Dun. No. 00. |

|||

| Greenwell’s Glory. No. 0. |

Greenwell’s Glory. No. 00 Double. |

Watery Dun. No. 00 Double. |

||

| Pale Summer Greenwell’s Glory. No. 1. |

Pale Summer Greenwell’s Glory. No. 00 Double. |

Black Gnat. No. 00. |

||

| Tup’s Indispensable. Wet. No. 0. |

Tup’s Indispensable. Wet. No. 00 Double. |

Olive Nymph. No. 0. |

||

| Dotterel Hackle. Tied Stewartwise. No. 00. |

Tup’s Indispensable. Floater. No. 0. |

![[Logo]](images/ititle.jpg)

It would ill become me if I allowed a Second Edition of “Minor Tactics of the Chalk Stream” to go to the public without expressing to those writers who have dealt with my volume in the Press my grateful sense of the generosity with which, whether they were or were not in agreement with the main object of the work—the endeavour to put the wet fly in what I conceive to be its right place on the chalk stream—they have one and all received it. In the fifty or so Press notices, short and long, I find, without exception, an absence of the harsh word, and a pervading urbane and kindly spirit which is of the true Waltonian still. Such fault as has been found has in the main been that I have shown undue timidity in dealing with the pretensions of the dry-fly purist. To that criticism I should like to reply that in dedicating my book to my friend the dry-fly purist I was using no idle word—that in asking him to make room for the wet fly beside the dry fly as a branch of the art of chalk-stream angling, I knew myself to be making a claim on viiihim which he would not willingly concede, and I was determined that no harsh or provocative word of mine should give offence to any of the many good friends, good anglers, and good fellows who would not—at the first onset, at any rate—find themselves able to see eye to eye with me.

I take leave to hope that the interval since the first publication of “Minor Tactics” has brought a good few of them round to the view that, without ousting the dry fly from pride of place as major tactics of the chalk stream, the wet fly has its subsidiary, but still important, place of honour in chalk-stream fishing.

Rising from the perusal of “Dry-Fly Fishing in Theory and Practice,” on its publication by Mr. F. M. Halford in 1889, I think I was at one with most anglers of the day in feeling that the last word had been written on the art of chalk-stream fishing—so sane, so clear, so comprehensive, is it; so just and so in accord with one’s own experience. Twenty years have gone by since then without my having had either occasion or inclination to go back at all upon this view of that, the greatest work, in my opinion, which has ever seen the light on the subject of angling for trout and grayling; and it is still, as regards that side of the subject with which it deals, all that I then believed it. But one result of the triumph of the dry fly, of which that work was the crown and consummation, was the obliteration from the minds of men, in much less than a generation, of all the wet-fly lore which had served many generations of chalk-stream anglers well. The effect was stunning, hypnotic, submerging; and in these days, if one excepts a few eccentrics who have been nurtured xon the wet fly on other waters, and have little experience of chalk streams, one would find few with any notion that anything but the dry fly could be effectively used upon Hampshire rivers, or that the wet fly was ever used there. I was for years myself under the spell, and it is the purpose of the ensuing pages to tell, for the benefit of the angling community, by what processes, by what stages, I have been led into a sustained effort to recover for this generation, and to transmute into forms suited to the modern conditions of sport on the chalk stream, the old wet-fly art, to be used as a supplement to, and in no sense to supplant or rival, the beautiful art of which Mr. F. M. Halford is the prophet. How far my effort has been successful I must leave my readers to judge. I myself feel that in making it I have widened my angling horizon, and that I have added enormously to the interest and charm of my angling days as well as to my chances of success, and that, too, by the use of no methods which the most rigid purist could rightly condemn, but by a difficult, delicate, fascinating, and entirely legitimate form of the art, well worthy of the naturalist sportsman.

In the course of my too rare excursions to the river-side, I have elaborated some devices, methods of attack and handling, which I have found of service, some applicable to wet-fly, some to dry-fly fishing, or to both. In the hope that xithese may be of interest or service, I have included papers upon them.

In conclusion I should like to express my gratitude to the proprietors of the Field, for permission to reprint a number of papers contributed by me to that journal over the signature “Seaforth and Soforth,” which come within the scope of the work; and to Mr. H. T. Sheringham, for his invaluable advice and assistance in the arrangement of these papers.

| PAGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NOTE TO THE SECOND EDITION | vii | ||

| FOREWORD | ix | ||

| CHAPTER | |||

| I. | OF THE BEGINNING OF THINGS | 1 | |

| OF THE INQUIRING MIND | 1 | ||

| II. | SUBAQUEOUS HAPPENINGS IN NATURE | 8 | |

| OF THE DROWNING OF DUNS AND OTHER INSECTS | 8 | ||

| OF THE STAGES IN A RISE OF DUNS | 9 | ||

| III. | SUBAQUEOUS HAPPENINGS IN ART | 14 | |

| OF MEDICINE FOR BULGERS | 14 | ||

| OF UNDER-WATER TAKING, ITS INDICATIONS, AND THE TIME TO STRIKE | 17 | ||

| OF ROUGH WATER AND GREY-BROWN SHADOW | 20 | ||

| IV. | SUPPLEMENTARY IN THE MATTER OF FLIES | 24 | |

| OF WET-FLY DRESSINGS FOR CHALK STREAMS | 24 | ||

| OF THE IMPORTANCE OF COLOUR OF TYING SILK | 29 | ||

| OF THE IMITATION OF NYMPHS, ETC. | 30 | ||

| V. | SPECIAL CONDITIONS AND WET-FLY SOLUTIONS | 36 | |

| NERVES | 36 | ||

| OF THE TROUT OF GLASSY GLIDES | 38 | ||

| OF THE WET FLY IN POOLS, BAYS, AND EDDIES | 41 | ||

| OF THE JUDICIOUS USE OF THE MOON | 44 | ||

| OF THE WET-FLY OIL TIP | 45 | ||

| OF GENERALSHIP AND THE WET FLY | 47 | ||

| A POTTED TROUT, AND ONE OTHER | 49 | ||

| OF TWO SATURDAY AFTERNOONS | 54 | ||

| xiv | |||

| VI. | UNCLASSIFIED | 57 | |

| OF HOVERING | 57 | ||

| OF THE PORPOISE ROLL | 59 | ||

| VII. | SUNDRY CONSIDERATIONS | 60 | |

| OF THE RELATION OF PATTERN TO POSITION | 60 | ||

| OF THE USE OF SPINNERS | 63 | ||

| OF GENERAL FEEDERS | 67 | ||

| ON ATTENTION TO CASUAL FEEDERS | 70 | ||

| OF THE FREQUENTATION OF DITCHES | 73 | ||

| OF THE NEGOTIATION OF TAILERS | 76 | ||

| OF THE FASCINATION OF BRIDGES | 78 | ||

| VIII. | MAINLY TACTICAL | 81 | |

| OF THE DELIBERATE DRAG | 81 | ||

| IN THE GLASS EDGE | 84 | ||

| OF THE CROSS-COUNTRY CAST | 87 | ||

| WHAT TUSSOCKS ARE FOR | 89 | ||

| OF THE ALLEGED MARCH BROWN | 91 | ||

| OF GENERAL FLIES | 92 | ||

| IX. | CONSIDERATIONS MORAL, TACTICAL, PSYCHOLOGICAL, AND INCIDENTAL | 95 | |

| OF FAITH | 95 | ||

| OF THE BANK OF VANTAGE | 98 | ||

| OF COURAGE AND THE JEOPARDIZING OF TUPPENCE HA’PENNY | 103 | ||

| OF IMPOSSIBLE PLACES | 105 | ||

| OF THE USE OF THE LANDING-NET | 109 | ||

| OF THE WEEDING TROUT | 115 | ||

| INCIDENTALLY OF THE LIGHT ROD ON CHALK STREAMS | 117 | ||

| AND OF WET-FLY CASTING | 120 | ||

| X. | FRANKLY IRRELEVANT | 122 | |

| A DRY FLY MEMORY | 122 | ||

| XI. | ETHICS OF THE WET FLY | 126 | |

| XII. | APOLOGIA | 131 | |

I read recently in that fine novel, “A Superfluous Woman,” a sentence enunciating a principle of wide application, to which anglers might with advantage give heed: “We ought not so much to name mistakes disaster as the common practice of servile imitation and faint-hearted acquiescence.” In no art are its practitioners more slavishly content “jurare in verba magistri” than in angling. Tradition and authority are so much, and individual observation and experiment so little.

There is, indeed, this excuse for the novice, that, going back to the authorities of the past after much experiment, he will find that they know in substance all, or practically all, that, apart from the advance of mechanical conveniences and entomological science, is known in the present 2day. The difficulty is to dissociate the dead knowledge, which is reading or imitation, from the live knowledge, which is experience. And if these pages have any purpose more than another, it is not to lay down the law or to dogmatize, but to urge brother anglers to keep an open and observant mind, to experiment, and to bring to their angling, not book knowledge, but the result of their own observation, trials, and experiments—failures as well as successes.

In all humility is this written, for I look back upon many years when it was my sole ambition to follow in the steps of the masters of chalk-stream angling, and to do what was laid down for me—that, and no other; and I look back with some shame at the slowness to take a hint from experience which has marked my angling career. It was in the year 1892, after some patient years of dry-fly practice, that I had my first experience of the efficacy of the wet fly on the Itchen. It was a September day, at once blazing and muggy. Black gnats were thick upon the water, and from 9.30 a.m. or so the trout were smutting freely.

In those days, with “Dry-Fly Fishing in Theory and Practice” at my fingers’ ends, I began with the prescription, “Pink Wickham on 00 hook,” followed it with “Silver Sedge on 00 hook, Red Quill on 00 hook, orange bumble, and furnace.” I also tried two or three varieties of smut, and I rang the changes more than once. My gut was gossamer, 3and, honestly, I don’t think I made more mistakes than usual; but three o’clock arrived, and my creel was still “clean,” when I came to a bend from which ran, through a hatch, a small current of water which fed a carrier. Against the grating which protected the hatch-hole was generally a large pile of weed, and to-day was no exception. Against it lay collected a film of scum, alive with black gnats, and among them I saw a single dark olive dun lying spent. I had seen no others of his kind during the day, but I knotted on a Dark Olive Quill on a single cipher hook, and laid siege to a trout which was smutting steadily in the next little bay. The fly was a shop-tied one, beautiful to look at when new, but as a floater it was no success. The hackle was a hen’s, and the dye only accentuated its natural inclination to sop up water. The oil tip had not yet arrived, and so it came about that, after the wetting it got in the first recovery, it no sooner lit on the water on the second cast than it went under. A moment later I became aware of a sort of crinkling little swirl in the water, ascending from the place where I conceived my fly might be. I was somewhat too quick in putting matters to the proof, and when my line came back to me there was no fly. I mounted another, and assailed the next fish, and to my delight exactly the same thing occurred, except that this time I did not strike too hard.

The trout’s belly contained a solid ball of black 4gnats, and not a dun of any sort. The same was the case with all the four brace more which I secured in the next hour or so by precisely the same methods. Yet each took the Dark Olive at once when offered under water, while all day the trout had been steadily refusing the recognized floating lures recommended by the highest authority. It was a lesson which ought to have set me thinking and experimenting, but it didn’t. I put by the experience for use on the next September smutting day, and I have never had quite such another, so close, so sweltering, with such store of smuts, and the trout taking them so steadily and so freely.

It was a September day two or three years later when I had another hint as pointed and definite as one could get from the hind-leg of a mule, but I didn’t take it. There was a cross-stream wind from the west, with a favour of north in it, and all the duns—and there were droves of them—drifted in little fleets close hugging the east bank, where the trout were lined up in force to deal with them, and feeding steadily. Fishing from the west bank, I stuck to four fish which I satisfied myself were good ones, and in over two hours’ fishing I never put them down. I tried over them all my repertoire. I battered them with Dark Olive Quill, Medium Olive Quill, Gold-ribbed Hare’s Ear, Red Quill (two varieties), Grey Quill and Blue Quill, Ogden’s Fancy, and Wickham, and 5I left them rising at the end with undiminished energy, and went and sat down and had my lunch. Then I sought another fish, and began again, when suddenly it occurred to me that I had not tried the old-fashioned mole’s-fur-bodied, snipe-winged Blue Dun. I had only a solitary specimen, and that was tied with a hen’s hackle; but such as it was, and greatly distrusting its floating powers, I tied it on. I did not err in my distrust, for after a cast or two it was hopelessly water-logged. I dried it as well as I could in my handkerchief, and despatched it once more on its mission. It went under almost as it lit, just above a capital trout, but for all that it was taken immediately. The next trout, and the next, and the next, took it with equal promptitude; one was small, and had to go back, but the others were quite nice average fish.

Then, in my eagerness, I was too hard on my gossamer gut when the next trout took my fly, and he kept it. I had no more of these Blue Duns, and I did not get another fish till the evening.

Still I did not realize that I was on the edge of an adventure, nor yet did I realize whither I was tending when Mr. F. M. Halford told me how a well known Yorkshire angler had been fishing with him on the Test, and, by means of a wet fly admirably fished without the slightest drag, had contrived to basket some trout on a difficult water.

6Indeed, it was several years later that, after fluking upon a successful experience of the wet fly on a German river which in general was a distinctively dry-fly stream, I began to speculate seriously upon the possibility of a systematic use of the wet fly in aid of the dry fly upon chalk streams. In conversation with the late Mr. Godwin (held in affectionate remembrance by many members of the Fly-fishers’ Club, and, indeed, by all who knew him), who had seen the very beginnings of the dry fly on the Itchen, and remembered well and had practised the methods which preceded it, I learned how, fishing downstream with long and flexible rods (thirteen or fourteen feet long), and keeping the light hair reel-line off the water as much as possible, these early fathers of the craft had drifted their wet flies over the tails of weeds, where the trout lay in open gravel patches, and caught baskets of which the modern dry-fly man might well be proud.

I gathered, however, that a downstream ruffle of wind was a practical necessity; and as I could not pick my days, and such as I could take were few and far between, I realized that, even if they appealed to me—which they did not—these methods would not do for me, as I might, and often did, find the river glassy smooth, but that, if I were to succeed, it must be by a wet-fly modification of the dry-fly method of upstream casting to individual fish.

7I could not believe that the habits of the trout were so changed as to make this impossible, and I began to look for opportunities to experiment. The bulging trout presented the most obvious case, yet it was rather by a chain of circumstance than by the straightforward reasoning which now seems so simple and obvious that I was led into experiments along this line.

How I effected some sort of solution of the problem with a variant of Green well’s Glory, and later on with Tup’s Indispensable, is detailed elsewhere, as also are my experiments with the trout of glassy glides (who seldom break the surface to take a winged insect, presumably because of the drag), together with other fumblings in the search of truth; but from that time forth I have seldom neglected an opportunity to test the wet fly on chalk-stream trout. It may be that on many occasions I have used the wet fly when the dry would have been more lucrative. On the other hand, I have found it furnish me with sport on occasions and in places when and where the dry fly offered no encouragement, nor any prospect of aught but casual and fluky success, and I have provided myself with a method which forms an admirable supplement to the dry fly, and has frequently given me a good basket in apparently hopeless conditions, and in the smoothest of water and the brightest of weather.

It has been advanced as an argument against the use of the wet fly, that duns and the other small insects which drift down upon the surface of a stream are never seen by the fish under water, and that a wet fly is therefore an unnatural object, especially if winged. “Never” is a big word, and I venture to think the case is overstated. I have watched an eddy with little swirling whirlpools in it for an hour together, and again and again I have seen little groups of flies caught in one or other of the whirls, sucked under and thrown scatterwise through the water, to drift some distance before again reaching the surface.

Anyone who has kept water-insects in spirit for observation or mounting is aware that they readily become water-logged, and by no means insist on floating. Again, we have it on the best authority that certain of the spinners descend to the river-bed to lay their eggs, and probably, that function performed, they ascend again through 9the water, giving the trout a chance while in transit. Thus the trout may well be familiar with winged insects under water. Even if he were not, it may be doubted whether he is sufficiently intelligent to reject a thing which he fancies he has found good to eat on the surface merely because it happens to be below. Indeed, experience so conclusively proves that trout will take the winged fly under water that those who repudiate both these propositions are upon the horns of a dilemma. Many hackled flies are more or less—and generally less—careful imitations of nymphs or larvæ. But of these more anon.

It has often been the subject of admiring comment that, before ever the angler can see a single fly in air or upon water, the trout will have lined up under the banks, and settled at the tails of weed-beds, and have begun to take toll of insect life; and many have commented on the startling unanimity with which trout begin to feed all at once all over a river or length. Some seem to suppose that, with a quick appreciation of values of temperature, atmosphere, barometric pressure, and what not, the trout discern when the flies will rise, and are there in readiness. Is it necessary to suppose anything far-fetched? It has often seemed to me that the swallows and martins can and do detect in advance the preparations for a rise in the 10swarming of nymphs released from weed or gravel, or whatever their particular fastness may be, and borne down the current. This precedes the actual hatch for a period greater or less according to temperature, pressure, and perhaps other little-understood conditions; and so it happens that no trout that is not “by ordinar’” stupid could fail to appreciate that game is afoot, and to put himself in position to enjoy the sport.

If one goes down to the bottom of the High in Winchester, near by King Alfred’s statue, and peers between the railings, one may generally see several brace of handsome trout; and if one takes some new bread and presses it together in little balls hard enough to make it sink, but not sink too fast, and throws it to the trout, one may see some most beautiful catching, neater than that of the most finished fielder in the slips. So when the nigh-upon-hatching nymphs are being hurried down, your trout shall enjoy some pretty fielding before the bulk of the quarry come near enough to the surface to attract attention to the trout’s movements by any swirl or break on the surface. If the trout be lying out on the weeds from which the nymphs are issuing, you shall see the trout swashing about in the shallow water covering the weed-beds, in pursuit of the nymphs, and presenting the phenomenon known as “bulging.” This is the first stage of the rise.

Presently, as the swarm of drifting nymphs 11becomes more numerous, escaping units, first in sparse, then in increasing numbers, reach the surface, burst their swathing envelopes, and spread their canvas to the gales as subimagines. Presently the trout find attention to the winged fly more advantageous—as presenting more food, or food obtained with less exertion than the nymphs—and turn themselves to it in earnest. This is the second stage. Often it is much deferred. Conditions of which we know nothing keep back the hatch, perhaps send many of the nymphs back to cover to await a more favourable opportunity another day; so it occasionally happens that, while the river seems mad with bulging fish, the hatch of fly that follows or partly coincides with this orgy is insignificant. But, good, bad, or indifferent, it measures the extent of the dry-fly purist’s opportunity.

Good, bad, or indifferent, it presently peters out, and at times with startling suddenness all the life and movement imparted to the surface by the rings of rising fish are gone, and it would be easy for one who knew not the river to say: “There are no trout in it.” For all that, there are pretty sure to be left a sprinkling, often more than a sprinkling, of unsatisfied fish which are willing to feed, and can be caught if the angler knows how; and these will hang about for a while until they, too, give up in despair and go home, or seek consolation in tailing. Often these will take a dry 12fly, but an imitation of a nymph or a broken or submerged fly is a far stronger temptation. This is the third stage.

Now, the dry-fly purist is quite entitled to his own opinions, and to restrict himself to the second stage; but if there be other anglers who are willing to vary their methods, who can and do catch their trout, not only in the second stage, but also in the first and the third, and if their methods spoil no sport for others, who shall say that they are wrong in availing themselves of all three stages of a rise of duns?

I remember well one day late in May when the three stages were excellently well marked. There was a bright sun, a light breeze from the east with a touch of south in it, and I was on the water about 9.30, and took the left bank, with the wind behind my hand. No fish were rising, but on reaching the water-side I almost stumbled on top of a trout which stood poised over a clear gravel patch under my own bank. Fortunately, however, I withdrew without his seeing or suspecting me. My pale-dressed Greenwell’s Glory trailed in the water, and I delivered it without flick, well wet, a foot or so above the spot where I had marked my fish. There was no break of the surface, but a sort of smooth shallow hump of the water about the size of a dinner-plate, with a dip in the middle, as the fish turned and I pulled into him. Presently I saw a brace bulging vigorously over some 13bright green weeds. It was not the first or the tenth time that my sunken Greenwell covered the fish that one of them came; but when he did there was no doubt about it, and he joined number one in the basket. Two more followed in a short time, unable to resist the same lure. Then it seemed to fail of its effect, though the river was freely dotted with rings, and after wasting much time I tumbled to the situation, and changed to a floating No. 1 Whitchurch—most effective of Yellow Duns—on a cipher hook. The effect was immediate, but I had put it off too long, and when I looked up from basketing my third trout to the Whitchurch the rise had worn out. But I was not done yet. I changed to a Tup’s Indispensable dressed to sink, and, fishing upstream wet in likely runs and places, I made up my five brace before I knocked off for lunch.

For many a year bulging trout were the despair of my life, and in those days I would gladly have said “Amen” to the opinion expressed in a letter to the Fishing Gazette of March 13, 1909, by the angler who writes over the pen-name of “Ballygunge,” that when trout were bulging you “might as well chuck your hat at them” as a fly. Many times had I vainly plied them with Gold-ribbed Hare’s Ear, as recommended by Mr. F. M. Halford, as well as most of the current imitations of duns on the water, and Wickhams, Tags, and other fancy flies to boot. Hoping against hope, I never gave up trying for those aggravating fish, and one day, towards the end of a bad exhibition of bulging by the trout, I actually caught a brace, and lost a third, on a Pope’s Green Nondescript—a dun tied with starling wing, red hackle and whisk, and a dark green body ribbed with broad flat gold.

On many occasions since I have found that fly kill well at the beginning of a rise, and it may be 15that on the occasion spoken of the trout which I got were on the verge of giving up bulging in favour of the winged dun. But I was not satisfied. Then the recollection of a visit to the Tweed struck me with the notion that on that water all the trout practically bulged all the time, and that with their wet-fly patterns Tweed anglers were able to give a good account of themselves, and I searched among Tweed patterns for the nearest analogue to Pope’s Green Nondescript. I thought I found it in Greenwell’s Glory, if varied by exchanging for the hen blackbird wing a starling wing. The likeness was not very exact, but it was close enough to experiment on. The point that I wanted to achieve was to combine with the colours of Pope’s Green Nondescript the type of dressing special to the Tweed Greenwell’s Glory. Rough, slim upright wings, well split, and standing well apart when wet, made of several thicknesses of feather so as to absorb water, and not to give it up readily when cast; body spare, consisting of the waxed primrose tying silk only, closely ribbed with fine gold wire, and one or at most two turns of a furnace hen’s hackle with ginger points, no whisk (whisks only help flotation), and a rather rank hook to take the fly under. The type of dressing is to be found applied to all his patterns in Webster’s “Angler and the Loop Rod.”

Whether it was because I had faith in my 16medicine, or whether any other cause was at work, I know not, but the experiment was, despite some misses due to failure to judge the right moment to pull home the hook, an immediate success.

Bulging trout are bold feeders, and seem to mind being cast over less than do those which are taking surface food; but they are much more difficult to cover accurately, because they rush from side to side and up and down, and the odds are that, if you cast to one spot, the trout is careering off in pursuit of a nymph to right or left of it. But once the trout sees the fly, the chances of his taking it are far better than are the chances that a surface-feeding trout will take the floating dun which covers him. The fly is allowed to drag in the stream, so as to be thoroughly wet, and is then cast upstream to the feeding fish in all respects like a floating fly, except that it is not dried or allowed to float. The weight of the reel-line will probably be enough to dry the gut, so that the risk of lining your trout is minimized, only the fly and the first link or so of gut going under before it reaches him. I found it best to tie this pattern on gut, and, dressed as described, it has been worth many a good bulger to me, apart from its value for general purposes.

Later on the value of Tup’s Indispensable fished wet impressed me much, and its resemblance to a nymph induced me to give it a trial upon bulging trout. For wet-fly purposes this is as near the 17dressing as I am at liberty to give: Primrose tying silk lapped down the hook from head to tail, a pale blue or creamy whisk of hen’s feather as soft as possible and not long, three or four turns of coarser untwisted primrose sewing silk at the tail, body rather fat, of a mixed dubbing of a creamy pink (invented by Mr. R. S. Austin, the well known angler and fly-dresser of Tiverton), and a soft blue dun hackle, very short in the fibre, at the head, the dressing being preferably finished at the shoulder behind the hackle. When this fly is thoroughly soaked it has a wonderfully soft and translucent, insect-like effect. It proved even more successful than Greenwell’s Glory, and with one or other I am almost always able to give a good account of bulgers instead of coming empty away.

Friends with whom I have discussed the use of the upstream wet fly on chalk streams have frequently said to me: “But how are you to know when the trout takes, and when to strike?” It is a very pertinent question, and the answer is not to be given in a word. Often the indications which bid you pull home the hook are so subtle and inconspicuous that the angler is at a loss to account for the miracle which is evidenced by his hooped rod and protesting reel, but even in the roughest 18water something helps the angler to divine the moment for action. In a subsequent section, under the heading “The Grey-Brown Shadow,” will be found an account of a day’s sport with the wet fly in an upstream wind so rough as to throw the river into waves. The flash of the fish as it turns to take the fly may often be seen, so dimly and so momentarily as to be apt to escape notice if one does not know what to look for; but I have on several occasions even divined it through water which reflected a bright white glare, and seemed opaque to the eye. If on these occasions a hooked trout had not proved the truth of my observation, I could not have sworn to having certainly seen anything move; but there through the surface, which looked at the angle of view impenetrable to the eye, I did seem to glimpse a faint pink flash that corresponded to no movement on the surface, and there was the fish soundly hooked, and no fluke about it.

Often under an opposite bank, when the light will not permit you to see your gut or fly, you will see a trout suddenly ascending to near the top of the water, and as suddenly sinking; then, if you tighten, ten to one your hook is firmly in his jaws, and you see him shaking his head savagely at the unexpected restraint upon his liberty ere he makes his first rush.

When fish are bulging, the moment of taking the fly is generally marked by a swirl, and the 19angler should strike immediately. Fortunately, a wet-fly strike, even if misconceived or mistimed, is far less likely, so long as the fish is clean missed and not lined, to alarm him than is a strike with the dry fly, because the wet fly comes out through the water at a point far below the fish instead of being drawn along the surface.

In glassy glides, which are always fast water, one either sees the fish turn to the fly, or, if the light prevents it, one sees a little crinkle, or break, work up through the water to the surface, which warns the angler to strike. Often the gut lying on the surface goes under as the fish draws in the fly, and alike in daylight and moonlight it acts as a float; and even if the fly be taken too deep below water for any other indication to be in time, it will warn the angler to attend to business. An ingenious angler, as elsewhere explained, has conceived and utilized successfully the idea of oiling his gut cast for fishing wet directly upstream in rapid water, and an excellent device it is for its occasion.

But perhaps the commonest indication of an under-water taking in water of slow or moderate pace is an almost imperceptible shallow humping of the water over the trout. It is caused by the turn of the fish as he takes the fly, and when the angler sees it it is time to fasten. If he waits until the swirl has reached and broken the surface (and it may not be violent enough to do so), he may be too late. If the fly drops directly over 20the fish, that shallow hump seems often almost simultaneous with the lighting of the fly; but if the cast be wide, your trout will not infrequently dart a yard or more to a wet fly—when for a dry fly he would do no such thing—and then the angler has a warning of the coming of the shallow hump on the surface which tells him that the iron is hot. It may be questioned, however, whether it is not more difficult to time correctly the strike for which one has had such warning than one which comes without warning.

In my experience, the trout which takes under-water is generally very soundly hooked. A trout taking floaters on the surface frequently sips them in through a narrowly-opened slit of mouth, but an under-water feeder draws in the fly by an extension of the gills which carries it in with a full gulp of water.

In the effort to divine the indications which call for striking with the wet fly I confess I find a subtle fascination and charm, and, when success attends me, a satisfaction beside which the successful hooking of a fish which rises to my floating fly seems second-rate in its sameness and comparative obviousness and monotony of achievement.

It was blowing up freshly from the south-west as the train ran into Winchester one April a year or two back, and ere the water-meadows were reached 21the distinct bite in the wind had given ample warning that, maugre the crisp yellow sunshine, 11.30 clanging from the cathedral spires left ample time to get down to the water-side and put rod and tackle together before the big dark olives or the smaller and rather lighter olives, which warn one to put up a Gold-ribbed Hare’s Ear, put in an appearance. April was three parts through, yet the backwardness of the season made conditions correspond more nearly to three weeks earlier in the normal year.

Soon everything was in readiness, and a couple of dark Rough Olives, tied on gut, with dark starling wing, heron herl body dyed in onion dye and ribbed with fine gold wire, and hackle and whisk of ginger, lightly dyed olive, were put into the damper to soak, on the chance that the wet fly might pay better than the dry.

Noon and the quarter-past chimed from the belfry, and then a big dark olive drifted on to an eddy near by, and, lifted out on the meshes of a landing-net, was identified. The hint was enough. One of the flies in soak—tied on No. 1 hooks—was knotted on, and the surface was scanned for the first dimple. Presently it was located—such a tiny, infinitesimal, dacelike dimple, hinting rather than proving the movement of a trout. It was hardly noticeable in the turmoil made by the strong ruffle of the upstream wind against the somewhat full current of the stream. It was 22rather far across for accurate casting in such a wind, and presently a sudden gust slammed the line down upon the spot with such a splash as no self-respecting trout could be expected to endure.

A movement upstream was prescribed by the conditions, and presently another dimple like the last was spotted in a more favourable position. It was repeated after an interval, but no fly was to be seen on the surface; so, without an attempt at drying, the Rough Olive was despatched on his mission, and lit a foot or so above the spot. Again, and once more, it did so, and then there was a hint of a grey-brown flicker in the hollow of a wave. By instinct rather than reason the hand went up, and the arch of the rod showed that the steel had gone home. In due course the trout—a fish of fourteen inches—was landed, and the angler proceeded upward.

He soon found, however, that to reach and cover the trout satisfactorily it behoved him to cross, and tackle them from the other side, and he made his way to the footbridge. On the way down, on the main stream he saw another hint of a rise in midstream, where the waves were highest. The wind served him well, and the fly was over the trout in no time. For four or five casts there was no response; then again that grey-brown shadow for a moment in the trough of a wave, mounting rod, a screaming reel, and a vigorous trout was battling for his life.

23Arrived presently at the desired spot, the wet Rough Olive was taken off and a dry-fly pattern mounted and duly oiled, and offered to three fish in succession, with the result that they all went down. Then back once more to the wet-fly, and thrice more ere 1.30 struck there was the faint flash of grey-brown under water, the same instinctive response, a spirited battle for life (successful in one instance), and then the rise petered out and not a fish was stirring. And though at 2.30 a strong rise of the smaller olive came on, and lasted till 4.30, keeping hundreds of swallows and martins busy, yet not another fish put up a neb. Perhaps it was because the sun had gone in.

There are those who wax indignant at the use of the wet fly on dry-fly waters. Yet it has a special fascination. The indications which tell your dry-fly angler when to strike are clear and unmistakable, but those which bid a wet-fly man raise his rod-point and draw in the steel are frequently so subtle, so evanescent and impalpable to the senses, that, when the bending rod assures him that he has divined aright, he feels an ecstasy as though he had performed a miracle each time.

Assuming that we have made up our minds to test the wet fly upon chalk streams, it must be taken as an axiom that the ordinary patterns of the dry fly will not do. They are built to dry and to float. The patterns required must be built to soak and to sink. Therefore bodies and hackles which throw the water must be rejected in favour of bodies and hackles which take up the water or readily enter it. So dubbed bodies in place of quills, hen hackles in place of cock’s, and of these a minimum of turns in place of a maximum; and if whisks are used, they, too, must be soft and soppy. For the same reason, wing material, if employed, should be so arranged as to take up the maximum of water, and to let it go as unwillingly as possible. Furthermore, the bulk of material in proportion to the hook metal must be reduced as far as possible.

Given these requirements, let us look around, as I did, among all the various systems of wet-fly 25dressing in use, from John o’ Groat’s to Land’s End, and see what features we ought to borrow from them. If we make up our minds, as I think we shall, that it is desirable to expose the body of our fly freely, we shall not adopt any system which lays the wings low over the back of the fly, that type being designed to secure what is called “a good entry” for a dragging fly, and we have nothing to do with dragging flies or any form of river raking or dredging, or with any flies which, like the Devonshire types, carry superabundance of bright cock’s hackles. So we are limited to the systems which dress their flies with upright wings, like the Tweed and Clyde types, and to the soft hackled Yorkshire style.

The conditions, however, of our waters confine us to tiny patterns—Nos. 0 and 00 hooks in the vast majority of cases, and occasionally No. 1—and the supply of tiny soft absorbent hackles from birds other than poultry, sufficiently small to leave the body well exposed, is hardly to be had. So, taking one consideration with another, it would seem that the Tweed and Clyde patterns, being used on a broad and in many places equablyflowing river, will have advantages enough to invite a trial.

Now, what are the features of the Tweed and Clyde patterns? First there is the spare body, dressed with tying silk only, with or without wire ribbing, or lightly dubbed with soft fur, making 26an absorbent dubbing; then a small and lightly-dressed soft hackle, two turns at the outside, close up behind a pair of wings tied in a bunch, and either left single or, preferably for our purposes, split in equal portions, and divided with the figure-of-eight application of the tying silk behind the wings and in front of the head, the whole tied on a rank, and not too light, round-bend hook.

It will be suggested that the trout does not see the winged dun under water. That is approximately, though not quite absolutely, true; but for all that, being in some respects rather a stupid person, if size and colour are right, he will not make much bones of the position of the fly with reference to the surface being incorrect. It might be supposed, again, that a hackled pattern would better suggest the nymph stage than a winged pattern. This may be true, but the theory has yet to be worked out in much detail before one can dogmatize about it. Elsewhere my preliminary efforts in this direction are described. Here I could say that the wings built up of a length of feather rolled into a bunch have the advantage of taking up a lot of water, and not releasing it readily; and they also assist to let the fly down more lightly on the water than so lightly dressed a fly would fall but for the wings. To let a hackled fly down as lightly, one would need a lighter wire and a larger hackle. The wings also 27help the fly to swim correctly in the water, with the weight of the straight, unsnecked, round-bend hook as the counterpoise to the parachute action of the wings.

My own belief is that wet flies tied on gut swim better and hook better than those tied on eyed hooks. As the drying action of casting is reduced to a minimum, they are not so ready to go at the neck as when used as dry flies; but if the angler prefers it, there is no reason why he should not use eyed hooks, though snecked bends of any kind and upturned eyes are deprecated. Down-eyed hooks, round, unsnecked, square-bend, and Limerick, in the order named, are recommended.

When immediate sinking in rather fast water is required, additional weight can be got by tying on a second hook, and making the fly what is technically known as a “double.” These are more easily tied on gut than on eyed hooks, though there is a maker who supplies eyed hooks for doubles in sizes Nos. 1, 0, and 00, one packet containing the eyed hook, and the other the shorter-shanked companion hook to be lashed on. In either case the hooks have to be separated with the thumb-nail, so as to stand at an angle of 45 to 60 degrees before using. Lest it should be suggested that these double hooks, fished wet, lend themselves to a form of snatching, let me say that I can only recall a single instance of a trout being hooked on a wet double otherwise than fairly in 28the mouth, and in the course of my experiments I have given them an extensive trial.

The range of wet-fly patterns required is not extensive. I have found the following serve all practical purposes:

It will be observed that hooks a size larger than those employed for floaters can often be used.

The very short range of hackled patterns is dealt with later.

Years ago I spent a week upon the Teme, fishing wet, and I remember looking down one sunny morning upon my cast in shallow water, and being struck by the appearance of my Yellow Dun. The body was dubbed with primrose wool, but though, while dry or in the air, every turn of the tying silk was completely hidden, yet, looking down upon the fly in the water, I could see every turn distinctly, and the dubbing was scarcely noticeable, and I was glad that the tying silk harmonized so perfectly with the hue of the dubbing.

The importance of the base colour of the tying silk was still more strongly brought home to me a day or two later. I had tied some imitations of a pale watery dun which was on the water with a pale starling wing, light ginger hackle and whisk, 30and a mixture of opossum and hare’s poll for dubbing; but some I had tied with pale orange silk, and some with that rich maroon colour called Red Ant in Mr. Aldam’s series of silks. The grayling took those tied with pale orange freely, but would not look at those tied with Red Ant.

It maybe of less consequence for floating flies, but for wet flies I have since always been careful to have the tying silk either harmonious with the colour of the natural subimago, or corresponding to the colour of the spinner. For instance, for an Iron Blue Dun I should use claret silk dubbed with mole’s fur or water-rat; for the old-fashioned mole’s fur Blue Dun, primrose to heighten the olive effect in the dark blue; primrose silk also for a Hare’s Ear; in the Willow-Fly, orange silk under the mole’s fur or water-rat; in the Grannom, green very darkly waxed, or black; and so on. The fact is that the transparency of fur and feather is marvellous. A starling’s wing looks much denser than a dun’s, but place it over print, and you can read every word through; and fur is practically as transparent when wet.

For some time after my introduction to Tup’s Indispensable I used it only as a dry fly, but one July I put it over a fish without avail, and cast it a second time without drying it. It was dressed 31with a soft hackle, and at once went under, and the trout turned at it and missed. Again I cast, and again the trout missed, to fasten soundly at the next offer. It was a discovery for me, and I tried the pattern wet over a number of fish on the same shallow, with most satisfactory results. I thus satisfied myself that Tup’s Indispensable could be used as a wet fly; and, indeed, when soaked its colours merge and blend so beautifully that it is hardly singular; and it was a remarkable imitation of a nymph I got from a trout’s mouth.

The next step was to try it on bulging fish, and to my great delight I found it even more attractive than Greenwell’s Glory. It was the foundation of a small range of nymph patterns, but for under-water feeders, whether bulging or otherwise, I seldom need anything but Tup’s Indispensable, dressed with a very short, soft henny hackle in place of the bright honey or rusty dun used for the floating pattern. The next I tried was a Blue-winged Olive. There was a hatch of this pernicious insect one afternoon. The floating pattern is always a failure with me, and in anticipation I had tied some nymphs of appropriate colour of body, and hackled with a single turn of the tiniest blue hackle of the merlin. It enabled me to get two or three excellent trout which were taking blue-winged olive nymphs greedily under the opposite bank, and which, or rather the first of which, like their predecessors, had refused to 32respond to a floating imitation. The body was a mixture of medium olive seal’s fur and bear’s hair close to the skin, tied with primrose silk, the whisk being short and soft, from the spade-shaped feather found on the shoulder of a blue dun cock.

Another pattern, successful in the last two months of the season, is dressed with a very short palish-blue dun or honey dun hen’s hackle, a body of hare’s poll tied on pale primrose silk, with or without a small gold tag and palest ginger whisks. But it is evident that on this subject I am only at the beginning of inquiry. Of course there is nothing very new in the idea of imitating nymphs. The half stone is just a nymph generally ruined by over-hackling.

In July, 1908, I caught an Itchen fish one afternoon, and on examining his mouth I found a dark olive nymph. My fly-dressing materials were with me, and I found I had a seal’s fur which, with a small admixture of bear’s hair, dark brown and woolly, from close to the skin, enabled me to reproduce exactly the colours of the natural insect. I dressed the imitation with short, soft, dark blue whisks, body of the mixed dubbing tied with well-waxed bright yellow silk, and bunched at the shoulder to suggest wing-cases, the lower part of the body being ribbed with fine gold wire. Two turns of a very short, dark rusty dun hackle completed the imitation, much to my satisfaction.

33Apparently it was no less agreeable to the trout, for, beginning to fish next morning at ten o’clock, I found six fish rising on a shallow. I began with a small Red Sedge, as no dun was yet on the water, and missed several of them. Then, putting up Pope’s Green Nondescript, I again missed three fish in succession. I then bethought myself of my nymph, and, knotting it on, in a few minutes I had five of the six fish, and had lost the other. I then found a trout feeding in a run, evidently under water. I made a miscast at him, and he came a yard across to take the nymph, but did not take a good hold, for I lost him, only to secure a better fish a few moments later. It then came on to blow and pelt with rain in such sort as to render it no sort of pleasure to continue fishing, and I knocked off at eleven o’clock, with three brace as the result of an hour’s fishing.

I have made me a shallow spoon-shaped net of butterfly-net material to attach to the ring of my landing-net. It has the advantage of taking anything which comes down the stream, whether on or under the surface, and its practical use demonstrates itself in more ways than one. For instance, in September, 1909, I went down to the river about 9.30, and, having put my rod together, sank my net in the water, and watched for what came down. There were a number of tiny diptera, but no trace of dun or nymph. I therefore concluded that it would be some time before the trout 34would be lined up under the banks, and that I could safely go away for an hour, and try certain carriers where the feeding of fish is not dependent on the rise. I did this, and put in over an hour’s exciting, if not very remunerative, sport before returning to the main river. The rise came on about 11.30. But for my net I might have wasted all the time on the bank, instead of conducting a siege of three very handsome trout, and bringing up two of them.

On occasion I have found a Dotterel dun tied with yellow tying silk on a No. 00 hook, and hackled with the tiniest dotterel hackle, after the manner of Stewart (i.e., not hackled all at the head, but palmer-wise for halfway down the short body), quite remunerative fished wet. This, I imagine, is taken for a dun emerging.

But it is not only duns whose nymphal stages may be imitated. I borrowed a tube containing some nearly full-grown larvæ of the alder, and though I am given to understand that in this stage the alder passes the greater part of its existence in the black mud formed by decaying vegetation, I made a sort of imitation of them which rather pleased me, and I tried it in Germany in mid-May. Whether the trout are or are not familiar with the natural insect in this stage I cannot say, but they took the imitation with such avidity that I speedily wore out my three specimens. They were only made as an experiment, and I tried no more, as 35I felt qualms in my mind as to whether it was quite the game to imitate this insect in this stage, any more than it would be to fish an imitation of the caddis. I am therefore not giving my recipe. Nor do I give that for making a caddis or gentle which I once tried, with mad success for a few minutes, and gave up, conscience-stricken. I have since seen alder larvæ in a glass tank in the Insect House at the Zoological Gardens, and, though their conditions are there no doubt quite artificial, they were swimming so freely and seemed so much at home in the water that I think it more than probable that they venture into the open often enough to be familiar to the trout. The long pale trailing processes along their sides suggested to me whether there was not to be found in the alder larvæ the prototype of the bumble.

I was at one time greatly interested in an attempt to imitate the fresh-water shrimp, and I tied a variety of patterns, including several with backs of quill of some small bird dyed greenish-olive, and ribbed firmly while wet and impressionable with silk or gold wire; but somehow I never used or attempted to use any one of them. I, however, gave one to an acquaintance, and he tied it on, and, standing on a footbridge, cast it downstream over some trout which were reputed uncatchably shy. At the first cast a big fish rushed at the shrimp, slashed it, and went off leaving the one-time owner lamenting.

Years ago, long ere the spirit of revolt was in me, when I followed as closely as I knew how the maxims of the apostles of the dry fly, and knew no other method for chalk streams, I suffered many blank days and much depression from a state of weather and light which must be familiar to all chalk-stream anglers—the more particularly because the “d——d good-natured” and sympathetic friend who knows nothing of the subject picks it out to say knowingly: “What a beautiful day for fishing!” It is clouded, dull, leaden, overhung, and the reflected light on the water is a dead milk-and-watery white; while, looking down into its depths, one sees everything with a deadly and crystalline clearness. There is no hint of thunder about, but on such days the trout are all nerves. Never are they so difficult to approach, never are they so ready to dart off with that torpedo wave. And if one finds a rising fish, and puts a dry fly over him, even if he bolts not, he rises no more.

37But at length there came a day when my first timid experiments in the fishing of chalk streams with the wet fly had proved encouraging enough to lead to my having a small stock of wet-fly patterns for chalk-stream fishing. It was a bad sample of those days when the nerves of trout seemed all on the jump, and I had fished from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. without so much as a rise. It was not that the fish were not rising. On the contrary, they rose very well—not very much, perhaps, but the best days are often those when the rise is moderate. But this day every fish I cast to went down at once, and too often I saw that detestable torpedo wave, sometimes at the approach, and more frequently at the first cast.

Soon after three I tied on a Tup’s Indispensable dressed on gut, and crawled carefully to within a long cast of a trout which rose at infrequent intervals in a narrow side-stream under the opposite side. My line trailed on the water as I approached, and I made the minimum of effort to dry the fly ere I delivered it, so as to attract as little attention as possible to my movements. So it came about that the fly, when it lit a yard or more to the left of and above the trout—it was a bad cast as regards direction—went immediately under. For the nth time that day I saw that torpedo wave as the fish darted through the shallow water. I rose with a sigh, but as I did so my rod was a hoop, and the reel screeched; for the trout’s dart 38had been at the fly, not from it, and it had gone a full yard or more to fetch it. He was just short of one and three-quarter pounds. Before four o’clock I had another brace by the same method. They were not easy, and I did not get every fish I tried, or even many; but I got some where with the dry fly I should assuredly have gone on getting none, and the trout stood to be cast to in a way they would not that day to the dry fly.

It is true enough that there are days and times when the dry fly will beat the wet fly hollow, but there are days when the converse is the case, and from subsequent experience I can recommend the trial of the wet fly on those dull, nervy days of milk-and-watery glare.

There are places on most rivers where the water comes swiftly and in solid volume down a slope too slight in the incline to create a fall, too short to create a rapid or stickle, and too smooth to cause a broken surface, yet with a rapid run below. The result is a glassy glide, gin-clear, with an air of unusual smoothness, and such a pace that there is an immediate drag upon any floating fly which is laid upon the current. Often some of the handsomest and best fighting trout in the river are to be found in such places, where their blood is constantly refreshed by the highly oxygenated water, their health and energy kept up to the 39mark by the need of contending against its swiftness, and the inducement to so contend is present in the plentiful supply of food brought down by the current.

Such a glide do I know well, with some excellent fish always showing there, but never breaking the surface; and for years I found them impregnable, for the simple reason that, if one pitched a fly over their noses, it was past them before they could rise to it, and if one pitched it up enough to give the fish a chance to take it they wouldn’t, because there was a prompt and streaky drag if the line were, as it could hardly help being, the least little bit across stream. Even the natural fly would sail over them unmolested.

But one day some years back, on a calm afternoon in July, with not a trout rising, I was on the Itchen, and I had crawled up some half-mile of sedgy bank in search of a feeding fish without finding one. But on the far side, in front of a certain post, the remnant of a one-time fence, I knew from experience that there was usually a fish—at any rate at feeding-time. There was nothing to suggest any particular dry fly, and on the previous afternoon—a Sunday—I had spent a pleasant twenty minutes watching a fish in front of the stump taking something under water with a sort of porpoise roll. It therefore occurred to me to put up one of those little Greenwell’s Glories, dressed by Forrest of Kelso on pairs 40of No. 00 hooks to gut, with which the name of Mr. Ewen M. Tod is associated. I had bought them in the previous spring to experiment upon bulging trout. These flies are known as “doubles,” and are not ready floaters. One puts a thumb-nail between the barb, and forces them apart till the two hooks form an angle of 45 degrees with each other. The fly dropped a yard above the post and sank. When it should have been nearing the post, a faint swirl rising to the surface seemed a sufficient indication of a movement below to justify a raising of the rod-point, and the fish was fast. In this manner it came about that a small Greenwell’s Glory on double hooks terminated the cast when the glassy glide above adverted to was reached. A trout lay out in it in position to feed, but though he moved a little from side to side, and may have been intercepting food, he made no rise. Keeping well out of sight, I dropped the Glory on the far side of and in front of the fish, and it at once went under. Again came the small disturbance welling quickly to the surface; up went my hand, and again a good trout was fast.

That afternoon I killed two and a half brace of good fish with the wet fly fished into likely places without seeing a single rise. The other three fish—but that is another story.

Since that day I have killed many a good fish in that hitherto impossible spot, and one morning 41in July, 1908, I had two and a half brace in less than an hour with a wet double Tup’s Indispensable out of it.

There is probably no problem which has filled the souls of so many dry-fly anglers with the despair attending defeat as that presented by a day when a cross-stream wind, whether up and across, down and across, or straight across, drives every dun under the opposite bank, and into little pools and eddies between the prominences on that bank, and so out of the line of the current which would otherwise carry them along. Then every big trout in the river seems to shift out of the current and into the sheltered bay or eddy, and there he sets to work collecting with busy neb the little argosies which have lost their tide, and are drifting helpless on slack water. It seems so easy to drop the fly in the right place. So it is, but if, as is many times more than probable, your cruiser is away a foot or two, or is deliberate in his movements, and does not take the fly at once, your drag has made itself painfully evident, and your fish is down for half an hour. No, on those occasions the only chance with the dry fly is to hit your fish with it on the tip of the nose at a moment when few naturals are about. Then he may snap it—but what a number of chances against its so falling!

42No, here is a case in which the wet fly is clearly predicated, and it should be so dressed as to go under without the least hesitation. The advantage which the wet fly has is not that the trout is taking the nymph in preference to the floating dun, though he is probably doing that far more than is apparent, but that, whereas a drag on the surface is fatal and betrays the gut, an under-water drag is not betraying, and the movement of the fly caused by the drag may, in its beginning at any rate, be even attractive to the trout, as imparting motion suggesting life and volition to an otherwise suspicious object. The drag also serves to tighten instead of slackening the line, so that a very small strike fixes the hook.

When the trout takes a wet fly in such a position, the surface indications are by no means obvious; but if the angler be on the alert to strike when such indications come, it is wonderful how soon he can pick up the knack, and what excellent fish this method brings him. A strike which does not touch the fish, being in the nature of an under-water drawing of the fly, will often have no scaring effect upon a feeding fish, where a strike with a floating fly would send him headlong to cover.

It is difficult to pick among my recollections one instance more illustrative than another of the value of this method, but I will take an afternoon in July, 1908. It was a cold day for the time of 43year, with a keen north-westerly wind across and a little down. A few little pale duns were going down, being beaten by the wind into and among the bays along the opposite bank, where they dodged in and out among the flags. Three trout, and three only, could I find moving, and they were taking every dun which went over them. I tried Little Marryat, Medium Olive, Flight’s Fancy, Ginger Quill, and Red Quill, in vain. In fact I put all three down. But they meant feeding, and were soon going again. It was the last day of a seven-day visit. I had so far forty-six trout, and I wanted to round off the fifty. I put up as an experiment a tiny dotterel hackle, tied with primrose tying silk in the true Stewart style, not with the fibres radiating from the head, but palmer-wise for halfway down the body. The trout had it at the very first offer, and was duly landed. I went on to the next, and got him almost immediately. The third, for some reason, had no use for Dotterel duns, but the moment I covered him with a Tup’s Indispensable he slashed it, and joined the other two in my creel. I looked in vain for a fourth, and there was no evening rise, so I had to leave off with but forty-nine of my fifty. But for the wet fly, I am convinced I should have had to content myself with the single brace which the morning rise had brought me, and that would have been a disappointing ending to a good seven days.

Though blinder than the proverbial bat in any slanting light, and therefore not as fortunate as I should like to be in fishing the evening rise, and though academically of opinion that fishing should cease when the dusk no longer lets the angler discern his fly, I confess to being at least as unwilling as any better endowed with sight to leave the water-side while the trout are still busy sucking down the spinners; but there are occasions when, if the moon be up enough to cast black shadows under the banks, and I can find the suitable spot with rising fish, I envy no man his superior eyesight—mine is good enough. Let me illustrate my meaning by describing the occasion on which I made my little discovery.

It was an evening in July. I had not begun fishing before four o’clock, and the afternoon had only earned me a single trout, and he no great shakes, either. The evening rise came on, and the trout began to feed briskly; but my infirmity was against me, and I missed or misjudged several rises, and it began to look as if I were going to make nothing of my opportunity, when I came to a bend where the current swung in pitch-black shadow under the opposite bank, while between the near edge of the shadow and my bank the stream ran molten moonlight. Round the bend in the dark I could hear the trout feeding away 45gaily, and the rings of their rises surged into the silver of the lighted current.

It seemed a mad thing to do, but I despatched my Tup’s Indispensable to a spot in the dark as near as I could judge above the ring of a good fish. My cast lay like a hair on the surface, stretching into the dark, not too taut. Suddenly I saw my gut draw straight upon the current, the farther end disappearing under the sheen of the moonlight, and, without waiting to think, I raised my rod-point, to find myself in battle with a solid fish. Thrice in the twenty minutes the rise lasted did I repeat this experience. Each trout was soundly hooked, and a nice level lot they were, running from one and a quarter to one and a half pounds. Thus was success at the last moment pulled by a fluke out of almost certain defeat. It is not always possible to find place and light serving in this way, but if you do, make use of the moon.

In my observations upon the judicious use of the moon, I indicated the advantage to be derived, in cases where the light prevented the rise from being otherwise detected in due time, from watching the gut cast as a float signalling the taking of the fly. Indeed, it is not only by night that the cast may be watched with advantage, but often by day when casting a fly, wet or dry, but especially wet, into a bad light, while the cast or part of it may be 46seen floating on a glassy piece of water. It is now some years since, in the columns of the Fishing Gazette, I called attention to what I described as the “wet-fly oil tip” in this connection. I take no credit for this invention. It belongs entirely to Mr. C. A. M. Skues, the secretary of the Fly-fishers’ Club, and its discovery came about in this way:

We were fishing opposite banks of a German trout stream, the Erlaubnitz, and the day rise of fly was over. The trout, which had been hovering over their pockets in the weeds and in the runs between them, had dropped out of sight, and it was obvious that it would need something to attract them more noticeable than the pale watery duns which were the staple of the season. We agreed upon Soldier Palmers tied with bright scarlet seal’s fur. Presently the far bank began catching them, though he was fishing upstream wet in rather fast water. I hailed him, and he said he had paraffined his gut cast to within the last two links from the fly and watched his cast. I was not above a hint, and in a minute or two I was experiencing the benefit of the wet-fly oil tip, and we were kept busy till six o’clock brought on the usual rise of Little Pale Blue of Autumn, and a change to floating patterns. It also involved a change of cast, for a cross-stream cast with oiled gut betrays you with a vile drag. It is a disadvantage of paraffining your gut that it limits 47you to one cast—viz., that directly upstream. But there are times when it is well to accept the limitation.

There is a bend on Itchen where the water runs deep and black. Over the best of it hang three large trees, under which, if trout be rising anywhere on the river, they will be found pegging away, and often when they are moving nowhere else. The place is near the spot where anglers foregather for lunch and a pull at pipe or flask; so the fish under these trees are hammered more than a little, and their knowledge is in direct proportion to their experience. Here, too, anglers usually take apart their split canes in the evening, and, ere they do so, have one last chuck in the dusk with Sedge, Coachman, or large Red Quill at one or all of these rising trout, but it is the rarest thing for one to be caught. I have caught six of them in fifteen years. Perhaps it is because to cover them one must fish straight across from the opposite bank—no other attack is possible—and they can hardly fail to see rod and angler.

But it fell about in the year of grace 1909 that my lawful occasions took me along the right bank, on which the trees grew, past the haunt of these aggravating risers, and I took the occasion to observe. None of them were moving at the time, and the water was lower by some inches than the 48normal. I looked in the place where the best of the risers was usually present when attending to business, but he was not there. Four or five yards farther upstream the bottom, from being shallow, dipped suddenly to the deep, with a sharp brown earthy edge, and there, lying in shelter from the current under the earthy ledge at the head of the hole, lay a trout which I put down at a comforting two pounds. He saw me, and slithered into his fastness, but I did not forget the hint. Many times had I cast to that trout when rising, but always under a tree some yards below. Now I would cast to him when not rising, and I would fish him in his hide. The lowest of a small cohort of ribbon-weeds craning their tips gently over the surface indicated the neighbourhood of the lip of the hole, and, scanning the opposite side carefully, I marked the exact bunch of yellow flower from behind which I ought to deliver my cast, and marked on the hither bank a bunch of purple hemlock which indicated the centre of the hole.

Later in the day from the opposite bank I sent over a wet Tup’s Indispensable to the weed’s edge several times without avail.

The next time I came down the fish was rising to surface food, and I left him severely alone. My time was to be when he was not rising, for no trout seems able to resist a nymph at any time, even if not feeding, and a nymph of sorts he should have. Coming back later, I found stillness reigning; 49so, mounting a Tup’s Indispensable, I soaked it well, and flicked it over to the edge of the weeds. It lit, and went under, leaving the gut for the most part along the surface. The gut drifted down, the fly end slowly slipping under the upper film. The fly was withdrawn and the cast repeated. Once more the gut lay along the surface; once more it slipped slowly through to a point; then it seemed to move under with a certain decision. I raised my rod-point with a drawing action, and the trout which had defied ten thousand dry flies was on. He wasn’t quite two pounds, but it doesn’t matter. It was generalship which got him, which discerned that in his holt he was possibly accessible to the seductions of the casual nymph-suggesting wet fly in a way in which he was not accessible to the temptations of the too well known dry fly in the place of vantage where he daily fed.

When the drowners are out in the water-meadows flushing the ditches till they flood the tables and drench the grasses with water seeking its way back through the herbage to the river by way of ditch, drain, and carrier, the wise old trout who know their business may be found in narrow ditches and channels down to foot-wide runnels in search of the earthworm and the miscellaneous pickings of the grasslands. Again, when July 50comes round, and the season of minnowing is indicated, the big trout once more make their way, in search of minnows, into the narrower irrigation channels of the water-meadows. So ardent are they at times in pursuit of their quarry that on occasion it is possible to net them out without their becoming aware of their danger.

On one occasion I got three good trout thus from behind at one scoop of the landing-net, and turned them back into the main.

Often, if they get into a channel with a constant flow and a steady food-supply, trout will not care to drop back to the river, and will take up a position of strength, where, inaccessible to the fly of the angler, they daily increase in size and lustihood. Such potted fish are almost entirely subaqueous feeders, a floating dun rarely crossing their field of vision. They grow dark and copper-coloured, and very unlike the fish of the river from which they hail.

One such fish do I remember, who took up his holt in the eddy just above a hatch-hole, through which ran the whole of a brisk stream some two to two and a half feet wide, turning at right angles to do so, after impinging on his eddy as on a sort of water-buffer. It was not hard to approach the place without being seen, but the moment one looked over the edge his troutship would flash down through the hatch-hole and into the racing stream beneath. Several times I mounted a 51Sedge, tied on a No. 2 hook attached to a strong cast, and dibbed cautiously over the edge. Once I caught a companion trout of one pound five ounces, but on all other occasions the attempt was fruitless.

Tired at length of these failures, and not pleased that such a trout as our friend of the hatch-hole eddy should give no sport to the fly, one afternoon I approached the hatch-hole from below, slid down my wide and large landing-net into the thrust of the stream, and looked suddenly over into the eddy. There was a brown flash to the hole, and next moment the trout was kicking in the net—black hogback with red copper sides and gleaming white belly, two and a half pounds, and as fat as a pig. Swiftly I conveyed him the needful fifty yards or so to a side-stream some ten or twelve yards wide, and turned him carefully loose. He made no pretence of being scared, but moved leisurely away across and up stream. I watched him cross a patch of weeds and enter a gravelled clearing, where a tidy trout lay, butt him out of it, and establish himself in his place. In a few moments he moved up into the next place, butted out the brace of trout which occupied it, and took the position of vantage. He did not remain long, but moved to the next pool, again ejecting the occupants.

Still dissatisfied, he moved higher up to where the stream was narrowed by camp-sheathing to 52support a low wooden bridge over which carts pass to carry the meadow hay. Here he ejected the three or four occupants, and established himself finally, with his neb close up under the sill of the bridge—too close for a fly to be got in ahead of him—obviously with the key of the larder in his pocket; and here daily for the next five days of my stay I saw him firmly planted, but, though I plied him with Sedge, and Quill, and Tup’s Indispensable, wet fly and dry fly, I never got an offer or an indication of a desire to offer from him, nor did I ever see him break the surface, and I left him in situ at the end of my visit.

During these five days, however, crossing from the smaller stream to the main, I saw a trout in a foot-wide runnel hovering with that quivering of the fins that indicates a willingness to feed. He was not a big fish—about one pound—but I thought it would be sport to try and cast to him and catch him in so narrow a channel, and I knelt down to deliver the fly. He saw me, however, and moved up. It was on my way ’cross meadow to the main, so I followed him till I came to the place where the runnel’s water-supply issued from a pipe which entered its head, at right angles to its course, from the centre of one of the tables. The flow from the pipe had worried out a corner hole, which was wide and deep enough to admit my whole landing-net and a bit over, and I dipped it in. I saw the amber gleam of my trout as he 53slashed by me and fled back down the runnel he had ascended, but wriggling in the net which I lifted was a bouncing fish, black, hogbacked, with copper sides and white belly, in first-rate fettle, and weighing better, at a guess, than one and a half pounds, evidently an old inhabitant of that corner. The main was but a few yards off, and I carefully turned in my captive.

Two days later I was fishing up the bank of the main in blazing sunshine, searching for a rising fish, but finding none, when my attention was attracted by a movement in the water close under my bank some ten or fifteen yards above the spot where I turned the trout in. I dropped my wet Greenwell’s Glory a foot or so from the spot, and, answering the draw of the floating gut signalling some under-water adhesion, I tightened on a nice fish, and after the usual preliminary exhibition of coyness, emphasized by sundry jumpings, I persuaded him to come ashore. The spring-balance said one pound ten ounces. Colour, size, and shape, were identical with the trout I had turned back two days before, and though, of course, I cannot prove it, I have no doubt he was the same.

Now, why did one of these potted trout take the fly, and the other refuse? This is my theory: Both had got the exclusive habit of subaqueous feeding, but the big one had his nose in a position where it was impossible to get a wet fly to him so as to pitch above him, or even alongside of his 54head, and the water was too fast for it to be worth the while of a fish of his calibre to turn and follow a mere nymph. The smaller fish was in a position to be covered, and the moment the nymph came to him under water he had it as a matter of course. Possibly, in the same position the larger trout might have done the same.

They were consecutive. Both were in August, 1909, and the reason why they are recorded is not because of any remarkable success, but because they illustrate varying conditions on the same river, proving amenable to varying treatment.