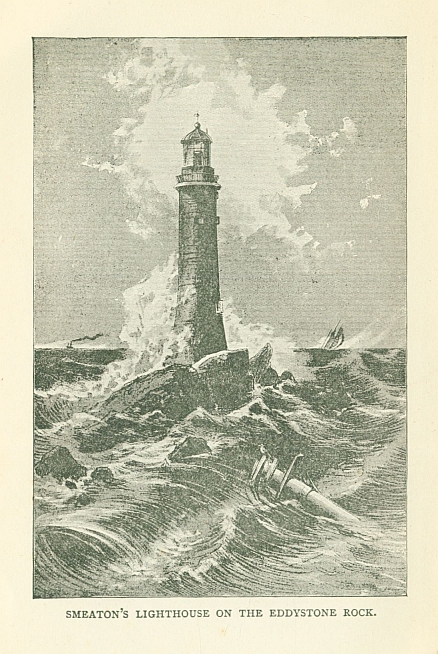

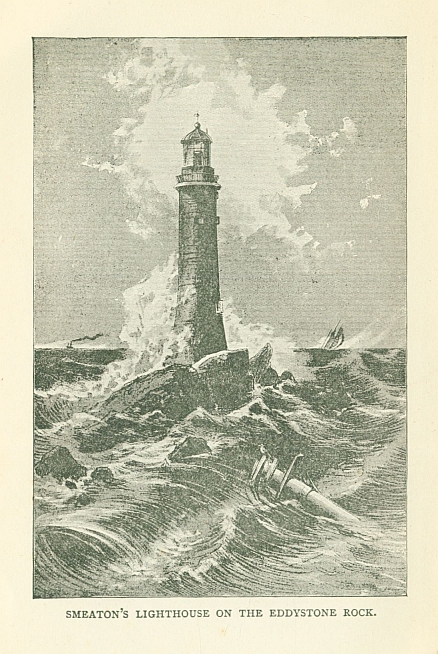

SMEATON'S LIGHTHOUSE ON THE EDDYSTONE ROCK.

Title: The story of John Smeaton and the Eddystone lighthouse

Author: Anonymous

Release date: August 30, 2025 [eBook #76767]

Language: English

Original publication: London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1900

Credits: Al Haines

SMEATON'S LIGHTHOUSE ON THE EDDYSTONE ROCK.

AND

THE EDDYSTONE LIGHTHOUSE.

"And as the evening darkens, lo! how bright.

Through the deep purple of the twilight air,

Beams forth the sudden radiance of its light

With strange, unearthly splendour in its glare!

"And the great ships sail outward and return,

Bending and bowing o'er the billowy swells;

And ever joyful, as they see it burn,

They wave their silent welcomes and farewells.

LONGFELLOW.

London:

T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW.

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK.

1900

Contents.

I. Ancient and Modern Lighthouses

III. How John Smeaton Rose in Life

IV. Smeaton in Private Life—His Last Years and Character

The following pages are founded on Mr. Smiles' "Lives of the Engineers," vol. ii.; "Smeaton and Lighthouses" (edition 1844); "Les Phares;" "Lighthouses and Lightships," by W. H. Davenport Adams; and Smeaton's own account of the "Eddystone Lighthouse." Some minor authorities have also been consulted.

THE STORY OF JOHN SMEATON.

As soon as man began to go down to the deep in ships, and to extend his enterprise from sea to sea, so soon must he have recognized the necessity of lighthouses; or, at least, of some system of signals by which he might guide his course at night when approaching a perilous coast, or seeking to enter the wished-for harbour.

His first attempt in this direction was probably nothing more than the kindling of a huge fire on some elevated promontory or headland, or on the summit of some lofty hill, whence its warning glare could be seen for miles around. But as, on windy nights, much difficulty would be experienced in keeping up the blown and scattered flames, no doubt he would soon conceive the idea of providing a sufficient shelter.

Lighthouses of antiquity.

So obvious was the value of these fiery beacons, and so impossible did it seem to the ancient mariner to navigate the dangerous seas without their help, that he was led to ascribe their origin to supernatural wisdom. According to the Greeks, they were invented by Hercules. There is good reason to believe, however, that long before the ocean was furrowed by a Greek keel, light-towers or fire-beacons had been erected by the Libyans and the Cuthites along the low and perilous shores of Lower Egypt. During the day they served as landmarks, and during the night as beacons. Their purpose being essentially sacred, they were also used as temples, and dedicated to the gods. Regarded by the seaman with reverence as well as gratitude, he enriched them with costly offerings. Some authorities suppose that charts of the Mediterranean coast and of the channels of the Nile were painted on their walls, and that these charts were afterwards transferred to sheets of papyrus. The priests in charge of them taught the sciences of hydrography and pilotage, and how to steer a vessel's course by the aid of the stars and planets. On the summit a fire was ever burning; the fuel being placed in a machine of iron or bronze, composed of three or four branches, each representing a dolphin or some other marine animal, and all connected by decorative work. The machine was fastened to the extremity of a strong pole or shaft, like a mast, and so placed that its radiance was mainly directed seaward.

Homer and the fire-towers.

The impression which the fire-towers produced on the mind is finely described by Homer in a well-known passage of the "Iliad:"—

"As to seamen o'er the wave is borne

The watch-fire's light, which, high among the hills,

Some shepherd kindles in his lonely fold."

It is said that the first regular pharos, or light-tower, was erected by one Lesches, on the Sigæan promontory, at the mouth of the Hellespont.

Though the most ancient, the honour was not reserved to it of bequeathing its name to its successors. This honour was bestowed on the celebrated tower erected on the island of Pharos, off the harbour of Alexandria, which served as a model for some of the noblest lighthouses built in later ages. Thus, it was the type followed by the Emperor Claudius in the pharos raised at Ostia, near the mouth of the Tiber, which appears to have been the completest of any on the Italian coast. This pharos was situated upon a breakwater, or artificial island, which occupied the mid channel between the two massive piers that formed the harbour, and its ruins were extant as late as the fifteenth century, when they were visited by Pope Pius II. Scarcely inferior in architectural excellence was the pharos which conducted the homeward-bound into the prosperous harbour of Puteoli; or that which Augustus erected at Ravenna; or that which from the mole of Messina poured its useful splendour over the seething waters of Charybdis; or that which embellished the island of Capreæ, the favourite retreat of Tiberius, and was destroyed by an earthquake shortly before the emperor's death.

Ancient lighthouses.

We read of a famous lighthouse at the mouth of the river Chrysorrhoas, which flows into the Thracian Bosporus (that is, the Strait of Constantinople). On the crest of the hill washed by this river may be seen, says an old writer, the Timean Tower, a tower of extraordinary height, from whose summit the spectator may survey a wide expanse of sea. It has been built for the safety of the navigator, and fires are kindled upon it for his guidance; a precaution all the more necessary because the shores of this strait are without ports, and no anchor can reach the bottom. But the barbarians in the neighbourhood light other fires upon elevated points of the coast, in order to deceive the mariner, and profit by his shipwreck.

The Alexandrian pharos.

The pharos, or lighthouse, at Alexandria, to which we have referred, was built by an architect named Sostrates, in the reign, it is said, of Ptolemæus Philadelphus. The island on which it stood lay in front of the wealthy city of Alexandria, so as to protect both its harbours, the Greater Harbour and the Haven of Happy Return, from the northern gales, and the inrush of the Mediterranean.

It forms a ledge of dazzlingly white calcareous rock, the northern slope of which is fringed with islets, which, in the fourth and fifth centuries of our era, were inhabited by Christian hermits. A deep inlet on that side was called the Pirates' Creek, because, in very early times, it had been the resort of the Carian and Samian sea-rovers.

The island was connected with the mainland by an artificial mound, or causeway, which, from its extent, seven stadia (about three-quarters of a mile), was called the Heptastadium. In its whole length a couple of breaks occurred, to allow of the passage of the waters, and each break was spanned by a drawbridge. At the island-extremity stood a temple dedicated to Hephæstos, the god of fire, and, at the other, the great Gate of the Moon. The lighthouse was erected at the eastern end, on a kind of rocky peninsula; and as it was built of white stone, and of a very considerable elevation, it was equally a notable landmark from the low sandy Egyptian plains and from the surrounding waters.

It is generally believed that this splendid erection, which is estimated to have measured from 550 to 580 feet in height, fell into decay between 1200 and 1300, and was finally destroyed by the Turkish conquerors of Egypt. That it existed in the twelfth century, we know from the description given by an Arab writer, named Edrisi; a description which our readers will probably be pleased to peruse:—

This pharos, he says, has not its equal in the world, for skill of construction or for solidity; since, to say nothing of the fact that it is built of the best stone, its separate layers of masonry are cemented together by molten lead, and this so firmly, that the whole is indissoluble, though the northern waves incessantly beat against it. From the rock to the middle gallery or stage the measurement is exactly seventy fathoms; and from this gallery to the summit, twenty-six fathoms.

The interior described.

We ascend to the gallery by an inner staircase of sufficient width. This staircase goes no further, and the building, from the gallery upwards, decreases considerably in diameter. In the interior, and under the staircase, some chambers have been built. From the gallery we continue our ascent by a very narrow flight of steps: in every part it is pierced with loopholes, to give light to persons making use of it, and to assist them in obtaining a proper footing.

This edifice, adds our authority, is singularly remarkable, as much on account of its height as of its massiveness. It is of exceeding usefulness, its fire burning night and day for the guidance of navigators. They are well acquainted with its light, and steer their course accordingly, for it is visible at the distance of a day's sail.* During the night it shines like a star; by day you can distinguish it by its smoke.

* There is, of course, some exaggeration here.

A Roman pharos.

Lighthouses or beacons were first introduced into England by the Romans, to whom we are indebted for so much that is valuable and useful. On the crest of the high hill at Dover still stands the pharos, which is supposed to have been built for the guidance of vessels from the coasts of France to the Roman station at Portus Rutupiæ (now Richborough) near Sandwich, or to Regulbium (now known as the Reculvers) on the Thames.

At the present day it is nothing more than a massive shell. In the inside the walls are vertical and squared; on the outside, they incline to assume a conical form. Of the building, as we now see it, only the basement is of Roman work; the octagonal chamber above was constructed in the reign of Henry VIII. The dimensions are about fourteen feet square.

English beacons.

The English beacons were of a ruder and more primitive construction than the Roman. We read in Lambarde, the old topographer, that "before the time of King Edward III. they were made of great stacks of wood; but about the eleventh year of his reign it was ordained that in one shire [Kent] they should be high standards, with their pitch-pots"—that is, tall masts, to whose summit was fastened a vessel full of burning pitch. Those beacons, however, were more frequently used to warn the country on the approach of a hostile fleet than for the purpose of lighting the coasts, though, doubtlessly, they answered both objects. Professor Faraday suggests that the first idea of a lighthouse was the candle in the cottage window, guiding the husband across the water or the pathless moor. The main point to be secured was a steady light, and it mattered not whether this was obtained from pitch-pots, coals, or oil. Wood, however, as the material readiest at hand, was most generally used.

The Tour de Cordouan, situated at the mouth of the Gironde, was long lit up by fires of wood; while, until a comparatively recent period, the lighthouses at Spurn Head, north of the Humber, and on the Isle of May, at the entrance to the Firth of Forth, were lighted by braziers of burning coal.

On Dungeness.

Our English Kings were quick to perceive the importance of insuring greater safety to the vessels composing their commercial navy; and in 1525, Henry VIII. granted a charter to the "brotherhood of the Holy Trinity" (now known as the Trinity House), for the purpose of assisting and protecting navigation by licensing and regulating pilots, and planting beacons, lighthouses, and buoys along the British coasts. But, as Mr. Smiles remarks, the only step taken to carry out objects of such national interest was the granting of leases by the Crown, for a definite number of years, to private persons willing to find the means of building and maintaining lights, in return for permission to levy tolls on all passing shipping. Yet not much was done to render our dangerous coasts easier of approach by means of well-supplied lights. The first erected was on Dungeness in the reign of James I. About the same time some parts of the Cornish coast were lighted up; for we read in the "Travels of the Grand Duke Cosmo, about two centuries ago, that the Plymouth shipping paid fourpence per ton for the lights which were in the lighthouses at night." Fourpence in those days was worth about as much as five shillings in our own, so that the tax must have fallen very heavily on merchantmen. It is also recorded, in the annals of the old town of Rye, that a light was hung out from the south-east angle of the Ypres Tower, as a guide for vessels entering the harbour in the night time; and that this proving insufficient, another light was ordered by the corporation "to be hung out o' nights on the south-west corner of the church, for a guide to vessels entering the port." A pitch-pot was formerly hung from the spire of old Arundel Church, as a beacon for vessels which wished to enter the port of Little Hampton, and the iron support of the apparatus is still to be seen.

Lighting the coasts.

It is obvious that lights such as these were exceedingly imperfect. It was difficult to maintain an equable radiance; they were not visible far out at sea; and they were easily affected by variations of weather, great gales, tempests, or thick mists. Moreover, as navigation increased, and ships more frequently threaded the narrow pass or dangerous channel, more lights became necessary, and thus the old system of lights had to give way to a more regular and extensive lighthouse system.

The modern system.

The first modern lighthouse of a solid and permanent character erected on the shores of England was built, it is said, at Lowestoft in Suffolk, in 1609. In 1665 one was erected at Hunstanton Point; and in 1680, a third on the Scilly Isles. About the same time were established the lighthouses at Dungeness and Orfordness. But all these wore of clumsy construction, of very slight elevation, and of inconsiderable illuminating power. To inaugurate the modern lighthouse the genius of John Smeaton was needed; and from the date of his marvellous monument on the Eddystone Rock up to the present time, nearly every dangerous point of our coasts, every harbour and every river-mouth, has been included in the system of defence which guards our imperial commerce, and enables the seaman to navigate the British waters in almost perfect safety.

About fourteen miles to the south-west of Plymouth harbour, and out in the deep and billowy channel, lies a reel or ledge of rocks, known, in allusion to the swirl of currents always tossing and seething around it, by the name of the Eddystone.

This reef is situated in a line with Lizard Head in Cornwall, and Start Point in Devonshire.

Consequently, it forms a perilous obstruction, not only in the water-way which leads to the great arsenal and haven of South Devon, but in the track of all vessels entering or leaving the English Channel; which, we may add, is frequented by a greater number of ships than any other part of the wide ocean.

The Eddystone rock.

When the tide is up, its hoary crest is scarcely visible, but its position is shown by the eddy which washes to and fro above it; at low tide, several low, jagged, and dreary ridges of gneiss lift their heads from the boiling waves. During a stiff breeze from the south-west, these form the centre, the focus, as it were, of a boiling caldron of waters, and no ship enticed within their vortex can escape destruction.

Henry Winstanley.

As may be supposed, the erection of a lighthouse on rocks so perilous came to be regarded as an urgent need soon after men had learned the value of commercial enterprise. The task, however, seemed so dangerous, not to say impossible, that no one ventured to attempt it, until 1696, when it was undertaken by a noble and patriotic gentleman, named Henry Winstanley, who was much grieved by the loss of life which annually occurred there.

Winstanley is described as one of those eccentric but ingenious men who find a peculiar pleasure in mystifying their friends, and in throwing a kind of glamour or magical atmosphere over our daily, commonplace, realistic life. He made use of his scientific knowledge to play the most extraordinary practical jokes. You went to spend a night or two at his old Essex manor-house. On entering your bed-room, you nearly tripped over an old slipper. You kicked it aside, and, lo, a ghost immediately started from the floor. In your sudden alarm you flung yourself into the nearest chair: out sprang a couple of arms, and clasped you and held you a prisoner. You went into the garden, and sought repose in a woodbine-trellised arbour. Your seat and yourself shot away from the pleasant alcove, and were quickly floating in the middle of the adjoining canal!

The author of such devices as these might be, and was, a noble and chivalrous gentleman, but he was also, unquestionably, a very eccentric character! His eccentricity displayed itself in the lighthouse which his chivalrous humanity instigated him to build on the Eddystone Rock. On first glancing at an engraving of it, you hardly know whether you see before you a Chinese pagoda or a Turkish minaret, grafted on a circular tower, and ornamented with cranes and chains like a London warehouse!

Winstanley began his work in 1696.

The first summer—and, of course, it was in summer only that men could labour on that wind-swept, wave-worn rock—was occupied in excavating twelve holes, and fastening as many irons in them, to serve for the superstructure.

Progress of the work.

Very slowly and drearily did the work go on; for though it was the "sweet summer-time," out in the wild channel the weather would frequently prove of such terrible violence that, for ten or fourteen days in succession, the waters would boil and toss about the rocks—vexed by contrary winds, and by the inrush of the swelling billows from the main ocean—and mount one upon another, like maddened horses, and leap and bound to such a height as completely to bury the reef and all upon it, and effectually prevent any vessel or boat from drawing near. On such days the men, you may be sure, thanked God that they were housed safely on the green shores of Devon.

The second summer was spent in building up a solid circular mass of masonry, twelve feet high and fourteen feet in diameter. In the third summer this huge pillar was enlarged two feet at the base, and the superstructure was carried up to a height of sixty feet. "Being all finished," says the engineer, "with the lantern, and all the rooms that were in it, we ventured to lodge in the work. But the first night the weather became bad, and so continued, that it was eleven days before any boats could come near us again; and not being acquainted with the height of the sea's rising, we were almost drowned with wet, and our provisions in as bad a condition, though we worked day and night as much as possible to make shelter for ourselves. In this storm we lost some of our materials, although we did what we could to save them; but the boat then returning, we all left the house, to be refreshed on shore: and as soon as the weather did permit we returned and finished all, and put up the light on the 14th November 1698; which being so late in the year, it was three days before Christmas before we had relief to go on shore again, and were almost at the last extremity for want of provisions; but, by good Providence, then two boats came with provisions and the family that was to take care of the light; and so ended this year's work."

Winstanley's lighthouse.

In the course of the fourth summer the foundations were considerably strengthened, and the remainder of the work appertaining to the fabric itself was completed. We are told, and the extant engravings show us, that it bore, in its finished condition, a close resemblance to "a Chinese pagoda, with open galleries and fantastic projections." Round the lantern ran a wide open gallery; so wide and open, indeed, that it was possible, when the sea ran high, for a six-oared boat to be lifted up by the waves and driven through it. Such an edifice could not long withstand the violence of the gale or the fury of the waters; but this much was gained by its construction,—it was shown that a lighthouse could be erected on this sea-girt rock, and, therefore, the achievement deserves to be described as "one of the most laudable enterprises which any heroic mind could undertake, for it filled the breast of the mariner with new hope."

The great storm.

Winstanley was very proud of his work, and so convinced, it is said, of its thorough stability, that he frequently expressed a wish to be under its roof in the fiercest hurricane that ever blew beneath the face of heaven, assured that it would not shake one joist or beam. Heaven sometimes takes the presumptuous at their word! Winstanley, with his workmen and light-keepers, had fixed his residence in the tower, when a tremendous storm arose, which, on the 26th of November, 1702, blew a hurricane of unprecedented violence. The sea rolled its billows heavily, and the wind raged, and masses of cloud darkened the horizon, and all Nature seemed convulsed by the elemental strife.

When the dawn broke, the people of Plymouth hastened to the beach, and turned their anxious gaze towards the Eddystone. The waters swirled and seethed around and about the rock; but where was the lighthouse, the fantastic structure raised by the ready brain and daring soul of Winstanley?

During the night it had been swept away, and not a memorial remained of its ill-fated occupants.

The melancholy incident forms the theme of a striking ballad by Jean Ingelow, which concludes in the following manner:—

"And it fell out, fell out at last,

That he would put to sea,

To scan once more his lighthouse-tower

On the rock o' destiny.

"And the winds woke, and the storm broke,

And wrecks came plunging in;

None in the town that night lay down

Or sleep or rest to win.

"The great mad waves were rolling graves,

And each flung up its dead;

The seething flow was white below,

And black the sky o'erhead.

"And when the dawn, the dull gray dawn,

Broke on the trembling town,

And men looked south to the harbour mouth,

The lighthouse-tower was down!

"Down in the deep where he doth sleep

Who made it shine afar,

And then in the night that drowned its light,

Set, with his pilot star."

John Rudyerd.

The usefulness of a beacon on the Eddystone Rock had been so abundantly proved that it was not long before an attempt was made to replace Winstanley's unfortunate structure. A Captain Lovet obtained a ninety-nine years' lease of the rock from the Trinity House Corporation, and engaged as his architect a silk-mercer on Ludgate Hill, named John Rudyerd. The reasons that led him to make so curious a choice are unknown, but the event proved that it was a sensible one. Rudyerd designed a graceful and even elegant building, choosing a circle for the outline, and studying the greatest simplicity, so as to offer the least possible resistance to wind and wave.

In order to obtain a firm foundation, he divided the surface of the rock into seven slightly unequal stages, and in these he dug or excavated six and thirty holes, varying in depth from twenty to thirty inches. Each hole was six inches square at the top, gradually narrowing to five inches, and then again expanding and flattening to nine inches by three at the bottom. Into these dove-tailed cavities or sockets were inserted strong iron bolts, weighing from two to five hundredweight, according to length and structure.

These bolts held fast a course of squared oak-timbers laid lengthwise on the lowest of the seven stages, so as to reach the level of the stage or step immediately above it. Another set of beams was then laid diagonally covering those already laid, and raising the level surface to the height of the third stage. The next course was deposited longitudinally, and the fourth diagonally, and so on alternately, until a basement of solid timber was erected, two courses higher than the highest point of the rock.

His lighthouse.

Rudyerd's lighthouse is generally described as a fabric of wood; but this is incorrect. To obtain the necessary solidity, and a sufficient weight to counteract the weight of the waters of the Channel, he combined courses of Cornish granite with his courses of timber, in the proportion of five to two, so far as the basement went: that is, he laid two courses of timber, and then five of granite, and then two more of timber; all being firmly secured by iron bolts and cramps. On this substructure, which measured 63 feet in height, with a base of 23 feet, he raised four stories of timber, crowned by an octagonal lantern, 10 feet 6 inches in diameter, and a ball of 2 feet 3 inches in diameter. The total elevation, from the lowest surface of the rock to the top of this ball, was 92 feet. Rudyerd completed his work in 1709.

On fire!

For a long period of years, nearly half a century, it withstood the attacks of wind and wave, and many a vessel was kept from destruction by its warning light. On the 2nd of December 1755, it was fated to fall before an unexpected enemy. There were three keepers resident in the lighthouse at the time. One of them, whose turn it was to watch, entered the lantern, at about two o'clock A.M., to snuff the candles, and, to his horror, discovered it to be filled with smoke. On opening the door which led to the balcony, to permit of its escape, a flame instantly leaped from the interior of the cupola. He hastened to alarm his companions, and vigorous efforts were made to extinguish the fire; but these proved ineffectual, owing to the dryness of the woodwork, and the difficulty of raising a sufficient supply of water to the top of the building. Fortunately for the keepers, the flames were descried from the shore, and a well-manned boat put off to their relief.

It reached the Eddystone about ten o'clock, when the fire had been raging for eight hours. The building was wholly destroyed; and the keepers, who had been driven away by the falling beams, the red-hot iron, and molten lead, were found, in a panic-stricken condition, crouching in a recess or cavern on the east side of the rock. They were carried into the boat, and conveyed ashore. Curious to relate, they were no sooner landed than one of them stole away, and was never afterwards heard of. His flight gave rise to a suspicion that the fire was not accidental; yet, when we remember that a lighthouse rock affords no means of escape for its inmates, we can hardly suppose it to be the place an incendiary would select for the scene of his wicked attempt. It is possible that the man's nerves had been so tried by the terrible nature of the peril he had undergone, that he knew not what he did.

The lightkeeper's fate.

Of the other two light-keepers, one, named Henry Hall, met with a singular fate. While engaged in dashing some buckets of water on the burning roof of the cupola, he chanced to look upwards, and a mass of molten lead fell down upon his head, face, and shoulders, burning him severely. On his arrival ashore, he persisted in asserting that a portion of the liquefied metal had gone down his throat. His medical attendant regarded the assertion as the offspring of a disordered imagination; but the man rapidly grew worse, and on the twelfth day of his illness, after an attack of violent convulsions, expired. A post-mortem examination of his body then took place, and Hall's story was found to be true; for in the stomach lay a flat, oval piece of lead, seven ounces and five drachms in weight!

John Smeaton.

Acting on the old maxim of "Try, try, and try again," the Trinity House Corporation determined to erect another light-tower on the Eddystone, and intrusted the work to a mathematical instrument maker, named John Smeaton, who had already acquired a reputation as an ingenious mechanician.

Smeaton at this time was thirty-two years of age. As we shall tell the story of his brave and industrious life hereafter, it will suffice us now to state that he had shown himself in a variety of experiences, skilful, prompt, patient, and indefatigable; never baffled by a difficulty, fertile in resource, and incapable of faltering in any enterprise he had deliberately undertaken.

Design of his lighthouse.

On examining into the conditions of the task which had devolved upon him, he came to the conclusion that the structures of his predecessors had both been deficient in weight; and that if Rudyerd's had not been destroyed by fire, it would not much longer have resisted the fury of the tempest. He announced his intention, therefore, of raising a fabric of such solidity that the sea should give way to it, and not it to the sea; and he determined to build it entirely of stone. Moreover, Winstanley and Rudyerd had wasted much valuable time, from the difficulty of landing on the rock, and the impossibility of working on it continuously for any length of time. But Smeaton proposed to moor a vessel within a quarter of a mile of the scene of action, which should accommodate his company of workmen; and thus they would be prepared to seize every opportunity of launching their boat, and carrying their materials to the rock, instead of making a long voyage from Plymouth on each occasion.

So far as concerned the design of his intended erection, he was ready to adopt Rudyerd's idea of a cone, but he proposed to enlarge its diameter considerably; and the type he kept constantly before his eye was the trunk of an oak tree, which is equally remarkable for gracefulness and strength, and withstands successfully the most furious gales, when other forest trees are bent or broken.

The autumn of 1756 was occupied in the transport of the granite and other materials to the rock, in their preparation, and in the excavation of the steps or stages on which the foundation was to be laid.

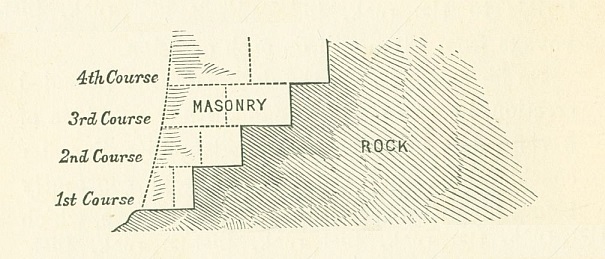

Laying the foundation.

Early in June 1757 the work of erection began. The first stone, weighing two tons five hundredweight, was laid on the 12th. On the next day was finished the first course, consisting of four stones, so ingeniously dove-tailed into one another and into the rock as to form a single compact mass. The sloping form of the rock, to which the foundation was, of course, adapted, required only this small number of stones for the first course; the diameter of the masonry gradually increasing until the highest level surface was reached. Thus:—

Eddystone lighthouse foundation

The second course, completed on the 30th of June, consisted of thirteen blocks of granite; the third course, completed on the 11th of July, of twenty-five; the fourth, on the 31st, of thirty-three. The sixth course was laid down by the 11th of August; and as it rose above the high-water mark, Smeaton was entitled to consider that he had conquered the greatest difficulties of his task.

Fixing the blocks.

Up to this point the mode of procedure in laying and fixing each great block of granite was as follows:—

The stone to be set being hung in the tackle,

and its bed of mortar spread, was then lowered

into its place, beaten with a heavy wooden mall,

and levelled with a spirit-level; and the stone

being accurately brought to its marks, was

considered as set in its proper position. The next

thing was to keep it there, notwithstanding the

utmost violence of the sea might beat upon it

before the mortar was thoroughly hard and dry.

Therefore the carpenter dropped into a couple of

vertical grooves, which had been previously cut in

"the waist" of the stone, each an inch deep and

three inches wide, two oaken wedges, one upon

its head, the other with its point downwards, so

that the two in each groove would lie heads and

points.

With an iron bar, about two inches and a half broad,

a quarter of an inch thick, and two feet and a half long,

he then drove down one wedge upon the other—very

gently at first, so that the opposite pairs of wedges,

being equally tightened, would equally resist each other,

and the stone would therefore keep its place. In like

manner, a couple of wedges were pitched at the top of

each groove; the dormant wedge (i.e., the one

with the point upward) being held in the hand, while the

drift wedge (i.e., the one with the point downward) was

driven with a hammer. So much as remained above the

upper surface of the stone was cut away with saw or

chisel; and, generally, a couple of thin wedges were

driven very moderately at the butt-end of the stone,

whose tendency being to force it out of its dove-tail,

they would, by moderate driving, assist in preserving

the steadiness of the entire mass, in opposition to any

violent agitation arising from the sea.

With an iron bar, about two inches and a half broad,

a quarter of an inch thick, and two feet and a half long,

he then drove down one wedge upon the other—very

gently at first, so that the opposite pairs of wedges,

being equally tightened, would equally resist each other,

and the stone would therefore keep its place. In like

manner, a couple of wedges were pitched at the top of

each groove; the dormant wedge (i.e., the one

with the point upward) being held in the hand, while the

drift wedge (i.e., the one with the point downward) was

driven with a hammer. So much as remained above the

upper surface of the stone was cut away with saw or

chisel; and, generally, a couple of thin wedges were

driven very moderately at the butt-end of the stone,

whose tendency being to force it out of its dove-tail,

they would, by moderate driving, assist in preserving

the steadiness of the entire mass, in opposition to any

violent agitation arising from the sea.

Progress of the work.

The stone thus firmly secured, a certain portion of mortar was liquefied, and the joints having been carefully "pointed," this liquid cement was poured in with iron ladles, so as to occupy every vacant space. The heavier part of the cement naturally fell to the bottom, while the fluid was absorbed by the stone. The vacancy thus left at the top was repeatedly refilled, until all remained solid; then the top was pointed, and, where necessary, defended by a layer of plaster.

The whole of the foundation having thus been brought to a proper level, some other means were required to secure a similar degree of solidity for the superstructure.

A hole, one foot square, was accordingly cut right through the middle of the central stone in the sixth course; and at equal distances in the circumference were sunk eight other sockets, each one foot square, and six inches deep. A strong plug of hard marble, also one foot square, but twenty-two inches long, was driven into the aforementioned central cavity, and set fast with mortar and wedges. This course, however, was only thirteen inches in depth; consequently the marble plug rose nine inches above the surface.

Upon the block thus prepared was set the central stone of the next course, having a similar hole in the middle, so as to receive the upper portion of the marble plug. Hence it is clear that no force or pressure of the sea, acting horizontally on any one of these central stones, could move it from its position, unless it were able to cut in two the marble plug; and to prevent the upper stone from being lifted, in case its mortar was destroyed, it was fixed down by four trenails. The blocks surrounding the central were dove-tailed together as before; and thus one course rose above another without any interruption, except from the occasional inrush of the waves or violence of the weather.

Smeaton's industry.

In his superintendence of the difficult and laborious work, Smeaton's activity and perseverance were unwearied. As soon as it had been so far accomplished as to present the appearance of a level platform, he could not deny himself the pleasure of a promenade upon it; but making a false step, and being unable to recover himself, he fell over the brink of the masonry, and among the rocks on the west side. As it was low water at the time, he received no serious injury. He dislocated his thumb, however, and as medical assistance was not available, he set it himself,—afterwards returning to his work. The incident is characteristic of the firmness and resolution which Smeaton exhibited throughout his busy career.

Building the light tower.

The ninth course was laid on the 30th of September, and concluded the operations for the year.

On the 12th of May 1758, Smeaton and his "merry men" returned to the lonely wave-washed rock, and were delighted to find their work intact. The cement seemed to have become as hard as the stone itself, from which, indeed, it was scarcely distinguishable.

Lusty arms and willing hearts made rapid progress; and by September, the twenty-fourth course was reached and laid. It completed the "solid" part of the building, and was designed to form the floor of the store-room; so that Smeaton had good reason to be satisfied with the progress made. But he knew how great an advantage it would be to exhibit a light in the coming winter; and therefore he resolved on completing the storeroom, if within the range of the possible, and planting a light above it.

The building had hitherto been carried up as a solid mass of masonry, like a breakwater or seawall, to a height of 35 feet 4 inches above its base, and 27 feet above the summit of the rock. It was now reduced to 16 feet in diameter. Of this limited space it was needful to make good use, so far as was consistent with the primary and indispensable condition of strength. The rooms were built with a diameter of 12 feet 4 inches, the walls being 2 feet 2 inches thick. These walls were built up of single blocks, and so shaped that a complete circle was formed by sixteen pieces, which were bound together with strong iron clamps, and secured to the lower courses by marble plugs in the fashion already described. That no damp might make its way through the vertical joints, flat stones were introduced into each, in such a manner as to be lodged partly in one block and partly in another. With all these careful and ingenious contrivances, the twenty-eighth course was completely set by the 30th of September.

Progress of the work.

This and the next course received the vaulted flooring, which answered the double purpose of the ceiling of the lower and the floor of the upper store-rooms. For additional security, a deep groove was here cut into the outer surface of the course, in which a massive iron chain was embedded in molten lead. The next course was laid and set after the same pattern; and by the 10th of October Smeaton had nearly completed his arrangements for establishing a light and lightkeepers at the Eddystone, when they were interrupted by legal difficulties, which had arisen between the lessee of the rock and the Trinity House Corporation.

These were not settled until the following year, so that Smeaton was unable to resume operations before the 5th of July. He worked, however, with so much vigour that the second stage was finished by the 21st; and on the 29th the fortieth course was set, and the third floor finished.

"Laus Deo."

The main column, or body, of the lighthouse was completed on the 17th of August, consisting of forty-six courses of masonry, and attaining an elevation of 70 feet. The last work done was singularly appropriate: the masons carved the words "Laus Deo" (Praise be to God!) on the last stone set above the lantern. All honest work should thus be dedicated to Him through whose infinite goodness we are permitted to achieve it. And, at an earlier date, Smeaton, in devout recognition of the Eternal Power, had inscribed on the course of masonry beneath the ceiling of the upper store-room, "Except the LORD build the house, they labour in vain that build it." It was in this spirit that the great engineer entered upon and accomplished his wonderful enterprises; and it is in this spirit that each of us should go through our daily toil, as if feeling ourselves ever in the immediate presence of our Father, and knowing that we strive, and endure, and hope, and suffer before his all-seeing eye.

The iron-work of the balcony and lantern were next erected, and the gracefully strong and massive structure was crowned by a gilded ball.

The interior of Smeaton's lighthouse was (and is) arranged as follows:—

Interior of the lighthouse.

On the ground-floor—Store-room, with a door-way, but no windows.

First stage, or story—Upper store-room, with two loopholed-windows.

Second stage—Kitchen, with fire-place and sink; two settles, with lockers; a dresser, with drawers; two cupboards; and a rack for dishes. Four windows.

Third stage—Bedroom, with three cabin-beds, each large enough for an adult; three drawers, and two lockers in each, to receive the clothing and other property of the light-keepers. Four windows.

Fourth—Lantern, with circular bench, or seat.

A narrow escape.

In fixing the window-bars, Smeaton met with an accident which might easily have been attended with fatal results. He thus describes the circumstances:—

"After the boat was gone, and it became so dark that we could not see any longer to pursue our occupations, I ordered a charcoal-fire to be made in the upper store-room, in one of the iron pots we used for melting lead, for the purpose of annealing the blank ends of the bars; and they were made hot all together in the charcoal. Most of the workmen were set round the fire; and by way of making ourselves comfortable, by screening ourselves and the fire from the wind, the windows were shut, and, as well as I remember, the copper cover or hatch put over the man-hole of the floor of the room where the fire was—the hatch above being left open for the heated vapour to ascend. I remember to have looked into the fire attentively to see that the iron was made hot enough, but not overheated. I also remember I felt my head a very little giddy; but the next thing of which I had any sensation or idea was finding myself upon the floor of the room below, half drowned with water. It seems that, without being further sensible of anything to give me warning, the effluvia of the charcoal so suddenly overcame all sensation, that I dropped down upon the floor; and had not the people hauled me down to the room below, where they did not spare for cold water to throw in my face and upon me, I certainly should have expired upon the spot."

Smeaton, however, was reserved for useful service; and on the 16th of October the welcome light shone once more from the dreaded Eddystone Rock. And the storm-tossed mariner, as he saw in the distance its helpful ray, and was guided by it how to steer his course, gratefully acknowledged the genius and resolution of the man who had raised it above the whirl of waters, and planted it in a tower so fair and strong.

The light on the rock.

For more than a century it has withstood the storm, an enduring monument to the fame of its great architect. At times, when the billows roll in from the Atlantic with more than ordinary fury, and the white-crested waters come up the Channel under the impulse of a south-west gale, the lighthouse is shrouded in spray, and its flame for a moment obscured. But the shadow passes away, and again across the wild waves it shines like a signal-star. Occasionally, when a mighty wave strikes it, the central mass of water runs up the tall, shapely column, and leaps quite over the lantern; or it beats against the masonry, as if to topple it from its foundation, and the windows rattle, and the building seems smitten with a sharp shudder. But the wind dies down, and the sea grows calm, leaving the lighthouse firmly planted on its rock.

John Smeaton, one of the most distinguished of British engineers, was born at Austhorpe Lodge, near Leeds, on the 8th of June 1724.

Smeaton's early years.

His father was a respectable attorney, who came of an old Yorkshire family; his mother, a quick-witted, firm, gentle-mannered woman, was not unworthy of such a son. He was taught at home during his earlier years, and a happy home it was. Leeds, in those days, had not attained to its present immense proportions, and Austhorpe was completely in the country, sheltered by the noble park and overhanging woods of Temple-Newsham. There was ample scope for the healthy, active boy, to indulge himself in his favourite pursuits, which had all of them a mechanical character. He was never so happy, says one of his biographers, as when put in possession of any cutting tool, by which he could make his little imitations of houses, pumps, and wind-mills. Even while still in petticoats, he was continually dividing circles and squares; and the only playthings in which he took a genuine pleasure were his working models. If any carpenters or masons chanced to be employed in the neighbourhood of Austhorpe, the boy was sure to find his way amongst them; and there he would spend hour after hour, watching the men at work, and observing how they handled their tools. Holmes tells us that, having one day taken due note of the operations of some mill-wrights, shortly afterwards, to the terror of his family, he was seen fixing a rude likeness of a wind-mill on the top of his father's barn.

Another time, when watching the procedure of a party of men engaged in refixing the village pump, he was fortunate enough to obtain from them a piece of bored pipe, which he succeeded in fashioning into a working-pump that actually raised water.

The young mechanic.

At a proper age, the boy was sent to the Leeds grammar-school, where he received, it is supposed, the largest part of his school instruction. In geometry and arithmetic he made very rapid progress; but, as is the case with most clever and industrious boys, he learned more at home than at school. Every leisure moment was occupied by his tools and machines. He acquired, in time, a mechanical dexterity and ingenuity which were really surprising, and availed him in the performance of some amusing surprises. Thus, it happened that some mechanics came into the neighbourhood to erect a "fire-engine," as the steam-engine was then called, for the purpose of pumping water from the Garforth coal-mines, and day after day Smeaton visited the spot for the purpose of watching their operations.

Carefully examining their methods, he made use of the knowledge so acquired to construct a miniature engine at home, appropriately equipped with pumps and other apparatus; and he even succeeded in setting it in motion before the colliery engine was completed. He first tried its powers upon one of the fish-ponds in front of the house at Austhorpe, which he quickly contrived to pump dry, and so killed all the fish in it, greatly to the surprise as well as the annoyance of his father.

Working on in this way, with assiduous application, young Smeaton, by the time he had arrived at his fifteenth year, had made a turning-lathe, on which he turned wood and ivory; and it was his delight to make presents of little boxes and other articles of his own manufacture to his friends. He also learned to work in metals, which he fused and forged without any assistance; and by the age of eighteen he handled his tools as dexterously as any regular smith or joiner.

Always at work.

"In the year 1742," says Mr. Holmes, his biographer and friend, "I spent a month at his father's house; and being intended myself for a mechanical employment, and a few years younger than he was, I could not but view his works with astonishment. He forged his iron and steel, and melted his metal. He had tools of every sort for working in wood, ivory, and metals. He had made a lathe, by which he cut a perpetual screw in brass—a thing little known at that day, and which, I believe, was the invention of Mr. Henry Hindley of York, with whom I served my apprenticeship. Mr. Smeaton soon became acquainted with him, and spent many a night at Mr. Hindley's house till daylight, conversing on these subjects."

Removal to London.

In his sixteenth year, our hero—for every biographer must have a hero—was removed from school to his father's office, where he was engaged in the uncongenial task of copying dreary legal folios, and acquiring as much knowledge of law as might fit him for an attorney's profession. As Mr. Smeaton had a good connection in Leeds, he not unnaturally wished his son to profit by it; but the future engineer revolted from "Blackstone's Commentaries" and "Coke upon Littleton;" and though, like a good son, he attended assiduously to his office duties, every day he found the burden of a detested occupation heavier to bear. Towards the end of 1742, partly with the view of furthering his professional duties, and partly for the sake of taking him away from his all-engrossing mechanical pursuits, Mr. Smeaton sent him to London. Here he made a vigorous attempt to subdue his tastes to his father's wishes; but utterly failing, he wrote to him an earnest appeal for permission to follow what was clearly an unconquerable bias.

With equal kindness and wisdom, his father consented, and young Smeaton immediately entered the service of a philosophical instrument-maker. He applied himself to his new vocation with such admirable energy, and it was so entirely fitted to the measure of his talents, that in a very short time he was able to relieve his father from all expenses connected with his maintenance.

Rising in life.

It is not to be supposed that a young man with so much strength of purpose and clearness of intellect would devote himself only to the mechanical part of his profession. He read industriously and methodically, so as to obtain a knowledge of the principles of theoretical science; he sought the society of educated men; he regularly attended the meetings and lectures of the Royal Society. He started in business on his own account in 1750, when he was only twenty-six; and in the same year he read a paper before the Royal Society on certain improvements effected by himself and Dr. Knight in the mariner's compass. In 1751 he invented a machine to measure a ship's way at sea, and experimented with it in a voyage down the Thames, and in a short cruise on board the Fortune sloop-of-war.

Work and method.

The activity and fertility of his mind are abundantly demonstrated by the nature of the work which occupied him in the following year. In April we read of a paper from his pen detailing certain improvements which he had contrived in the air-pump; in June he describes an ingenious modification in ship-tackle by means of pulleys, so arranged that one man might easily raise a ton weight; in November he describes certain experiments which had been made with Captain Savary's steam-engine, the precursor of James Watt's. Meantime he was engaged in researches into "the Natural Powers of Water and Wind to Turn Mills and other Machines depending on a Circular Motion;" which afterwards gained him the Royal Society's gold medal—almost the highest honour a man of science can receive in England. Now, it is obvious that to accomplish so much honest and valuable work, and at the same time to carry on his business, required great application, great energy, great method. And it must be conceded that throughout life Smeaton was an unwearied seeker after knowledge; that his two main objects were, self-improvement and the public welfare; self-improvement being necessary that he might render the gifts he possessed of the highest possible usefulness to society. "One of his maxims," says Smiles, "was, that 'the abilities of the individual are a debt due to the common stock of public happiness;' and the steadfastness with which he devoted himself to useful work, in which he at the same time found his own true happiness, shows that the maxim was no mere lip-utterance on his part, but formed the very mainspring of his life. From an early period he carefully laid out his time with a view to getting the most good out of it: so much for study, so much for practical experiments, so much for business, and so much for rest and relaxation."

The value of order.

Let the young reader take note of this, and in like manner find for everything its fitting and sufficient time. There is much wisdom in the adage, "A place for everything, and everything in its place;" but it is equally necessary that there should be "an hour for everything, and everything in its hour." The best talents, the best opportunities, will be wholly wasted, unless their possessor can recognize the value of method. The man who does not systematize his time, who does not economize it so as to accomplish in each day the largest possible amount of work, without haste or unhealthy pressure, will make but an indifferent use of his gifts, and will assuredly lose many precious hours. He will be always too late; always endeavouring to overtake the lost moments, and never succeeding in doing so; until at length such a weight will accumulate upon him of work undone and opportunities neglected, that, in his exhaustion and discontent, he will lose all hope, and sink into the idleness of apathy. Method is the secret of success: the methodical student will get out of the twenty-four hours all that it is possible to get out of them; while the irregular and disorderly will lose a more or less considerable portion of them, according to the degree of his want of system.

Smeaton abroad.

Smeaton devoted a portion of his time to the study of French, in order that he might be able to read the valuable scientific treatises contained in that language, and also that he might be able to take a journey which he contemplated into the Low Countries, for the purpose of inspecting the great canal works of the Dutch engineers.

Smeaton in Holland.

He carried out his intention in 1754, when he traversed Holland and Belgium—mostly on foot, or in the truckschuyts or canal boats, which form the national conveyance of those countries—and carefully inspected the most remarkable achievements of mechanical science in the districts through which he passed.

It was with no little interest he found himself in a land which has been literally rescued from the sea by the efforts of human skill and industry; a great portion of which, even in comparatively modern times, was buried deep beneath the waters of ocean; a land to which nature has been so unkindly, and for which man has done so much. In a certain sense, Holland is the creation, as well as the trophy, of the engineer; and wherever Smeaton went, he found himself in the engineer's track. From Rotterdam he travelled by Delft, famous for its pottery, and the Hague, to the great commercial emporium of Amsterdam, and thence, as far north as Holder, examining with critical attention the huge dikes and embankments raised by the labour of man to prevent the sea from recovering its own.

At Amsterdam he saw with delight and surprise its admirable harbour and spacious docks. In Smeaton's time, London had no accommodation of this description, and the numerous fleets which flocked to the British metropolis dropped anchor in the Thames, and loaded and unloaded at the river quays.

Passing round the country by Utrecht, he proceeded to inspect the great sea-sluices at Brill and Helvoetsluys, through which the inland waters found a channel of egress, while the billows of ocean were prevented from forcing an entrance. During this journey he made copious notes of all he saw, and the information thus acquired was of great use to him in his after-labours as a canal and harbour engineer.

The Eddystone lighthouse.

He returned to England in 1755; and shortly afterwards the opportunity came to him which, we believe, comes to every man of industrious habits and steadfast purpose—the opportunity, by a prudent employment of which, we may place ourselves in a position to turn our gifts to good account, and do something for the advantage of our fellows. The lighthouse erected by Rudyerd on the Eddystone Rock, of which we have already given a description, was swept away by a destructive fire on the 2nd of December, and it became necessary to replace it by a new one. The proprietors applied to the President of the Royal Society to recommend to them an engineer who might be safely intrusted with a work so important. The then President, the Earl of Macclesfield, replied "that there was one of their own body whom he could venture to recommend for the work; yet that the most material part of what he knew of him was his having, within the compass of the last seven years, recommended himself to the Society by the communication of several mechanical contrivances and improvements; and though he had at first made it his business to execute things in the instrument way (without ever having been bred to the trade), yet, on account of the merit of his performances, he had been chosen a member of the Society; and that, for about three years past, having found the business of a philosophical instrument-maker not likely to afford an adequate recompense, he had wholly applied himself to various branches of mechanics."

Upon this recommendation the proprietors acted, and Smeaton was engaged to erect the Eddystone lighthouse.

Preparing for the work.

The subject was wholly new to him, and therefore, as was his custom, he began to investigate it in all its bearings before he took any decisive step. One of the earliest conclusions at which he arrived was, that the new lighthouse ought to be built of stone, as the most durable and the safest material. He came to this decision from a careful examination of the plans and models of the two former lighthouses, which showed him that their leading defect was want of weight; of weight sufficient not only to resist the sea, but to compel the sea to yield to the building, so that it might neither rock in the winds nor tremble before the waves.

A visit to the rock.

As soon as he had made up his mind as to the principles on which the lighthouse should be constructed, he paid a visit to its intended site. He arrived at Plymouth about the end of March, but it was the 2nd of April before he could embark for the Eddystone, owing to the violence of the wind and the heavy sea that was running in the Channel. On reaching the rock, the billows beat upon it with so much fury that it was impossible to land. All that Smeaton could do was to view the rocky cone—"the mere crest of the mountain whose base was laid so far down in the sea-deeps beneath—over which the waves were lashing, and to form a more adequate idea of the very narrow as well as turbulent site on which he was expected to erect his building."

Three days later, however, he ventured on a second trip, when he succeeded in landing on the rock, and thoroughly examining it. The only traces he could find of the lighthouses erected by his predecessors were the iron branches fixed by Rudyerd, and remains of those fixed by Winstanley.

On a third voyage to the rock, Smeaton was baffled by the wind, which compelled him to return to harbour without even obtaining a sight of it. After five more days, during which the engineer was employed in looking out a proper site for a work-yard, and examining the granite in the neighbourhood for the purposes of the building, he made a fourth voyage, and although the vessel reached the rock, the wind blew so freshly and the breakers dashed so furiously that it was again found impossible to land. He could only direct the boat to lie off and on, while he watched the breaking of the sea and its action on the reef. A fifth trial, after the lapse of a week, proved equally unsuccessful. After rowing about all day with the wind ahead, the party found themselves at night about four miles from the Eddystone, near which they anchored until morning; but a storm of wind and rain arising, they were compelled to return to Plymouth without succeeding in their object.

Try, try, and try again.

The sixth attempt—we record these minute particulars because they give such a vivid illustration of Smeaton's persevering energy—was successful, and on the 22nd of April, after the lapse of seventeen days, Mr. Smeaton landed a second time.

After a careful inspection, the party retired to their sloop, which lay off until the tide had fallen, when Smeaton again landed, and the night being very calm, he continued on the rock until nine in the evening.

On the 23rd he again landed, and pursued his operations; but this time he was interrupted by the ground-swell, which dashed the waves upon the reef, and, the wind rising, the sloop was forced to put back to Plymouth. During this visit, however, our engineer had secured some fifteen hours' occupation on the rock, and taken the dimensions of all its parts, to enable him to construct an accurate model of the foundation of the proposed structure. To correct the drawing, however, and to insure the utmost exactness, he determined upon attempting an eighth and final voyage of inspection on the 28th of April.

The eighth attempt.

Again the violence of the sea foiled him in his design.

Another fortnight passed, a fortnight of unfavourable weather; but the time was not wasted. The engineer elaborated his design, and made all the preliminary arrangements to proceed with the work. He also drew up a careful code of regulations for the instruction and government of the artificers and others who were to be employed upon it. And this being done, he arranged for a journey to London, but not until he had paid three more visits to the rock for the purpose of correcting his measurements.

In August 1756, as we have already related, the erection of the lighthouse was begun, and operations were continued until the end of November, in spite of the obstacles offered by a violent sea and unfavourable winds.

The return of the workmen to port, in their store-vessel the Neptune, was safely accomplished, though the voyage was not unattended with danger.

A storm at sea.

Unable, in consequence of the violence of the gale, to make Plymouth harbour, the Neptune was steered for Fowey, on the coast of Cornwall. Higher and higher rose the wind, until it blew quite a storm; and in the night Mr. Smeaton, hearing a sudden alarm and outcry amongst the crew overhead, ran upon deck half-dressed to learn the cause. It was raining heavily, and the hurricane lashed the waters into a whirlpool of spray and foam. "It being very dark," says Smeaton, "the first thing I saw was the horrible appearance of breakers almost surrounding us; John Bowden, one of the seamen, crying out, 'For God's sake, heave hard at that rope, if you mean to save your lives!' I immediately laid hold of the rope, at which he himself was hauling as well as the other seamen, though he was also managing the helm. I not only hauled with all my strength, but called to and encouraged the workmen to do the same thing." The sea was dashing with terrible fury, and with a roar which drowned all other sounds, upon the rocks. The Neptune's jib-sail was all at once rent into a thousand shreds; and to save the main-sail, it was lowered, when, happily, the vessel obeyed her helm, swung round, and put out to sea. At daybreak her crew found themselves out of sight of land, and driving towards the Bay of Biscay. But as the gale had abated, they soon got the vessel's head round again, and stood for the coast. Before night they sighted the Land's End, but could not then make the shore. For another night and day they were tossed to and fro, almost helplessly. A vessel coming in sight, they exhibited signals of distress; she bore down, and directed them how to steer for the Scilly Islands. The wind veering round, however, they bore up again for the Land's End, passed the Lizard and Rame Head, and, finally, after being blown about at sea for four days, dropped anchor in Plymouth Sound, much to their own contentment and to the satisfaction of their friends, who were despairing of their reappearance.

Smeaton's activity.

Having fully described the gradual erection of the Eddystone lighthouse in a previous chapter, we will not weary the reader with a repetition of details with which he is already acquainted. But reference may appropriately be made to the energy and restless activity with which Smeaton watched the progress of the enterprise. If there was any position of danger his men hesitated to occupy, he immediately stepped forward and took the foremost place. One morning, in the summer of 1757, when heaving up the moorings of the store-ship, preparatory to starting for the rock, the links of the buoy chain were exposed to a considerable strain upon the davit-roll, which was of cast-iron, and began to bend upon its convex surface. To remedy this, Smeaton ordered the carpenter to cut some trenails into small pieces, and split each length into two, with the view of applying them between the chain and the roll at the flexure of each link, so as to relieve the strain. One of the men remarked that if the chain should break anywhere between the roll and the tackle, the person engaged in inserting the wooden wedges might be cut in two by the chain, or carried overboard along with it. Smeaton, who never required others to undertake what he would not do himself, immediately put aside his men, took the "post of honour," as he called it, and superintended the getting in of the chain, link by link, until it was all on board.

We borrow the following interesting sketch from Mr Smiles:—

While living at Plymouth, he says, the restless, enthusiastic engineer was accustomed every morning to take his post on the grassy summit of the Hoe, and with his telescope to survey the famous rock.

The Plymouth Hoe.

The Hoe is an elevated promenade, occupying a high ridge of land between Mill Bay and the entrance to the harbour, with the citadel at its eastern extremity. It forms the seaport of Plymouth, and commands the beautiful and varied scenery of the Sound. In front of it lies St. Nicholas's Island, bristling with fortifications; beyond, rising in verdurous slopes and terraces from the water's edge, is Mount Edgcumbe Park, with its masses of luxuriant foliage backed by green hills. The land juts out on either side the bay in rocky points, which are crowned with forts and batteries; while in the distance now, though not in Smeaton's time, extends the nobly massive rampart of the breakwater, midway between the bluffs of Redding and Staddon Points, so as to arrest the long roll of the Atlantic waves, and protect the placid expanse of the great harbour. It was from the Hoe that our ancestors first descried the immense array of the Spanish Armada advancing threateningly toward the English coast. It was the favourite watch-tower, so to speak, of Sir Francis Drake in those times of difficulty and peril, as it was now of Smeaton in less critical circumstances: and it may be added, that these two men, each so illustrious in his special vocation, possessed many characteristic qualities in common; perseverance, patience, heroic endurance, indomitable resolution; the qualities, in fact, by which great deeds are accomplished.

A famous hill.

Smeaton, when he ascended the Hoe after a stormy night at sea, had neither eye nor thought for the picturesque beauties or historical associations of the scene before him. All he could think of was his lighthouse on the rock. He knew that he had brought the fullest resources of skill, and care, and prevision to bear upon its erection, yet he could not avoid a feeling of anxiety as to the security of the foundation. Many there were who still went about asserting that no fabric of stone could possibly stand upon the wave-worn, wind-beaten rock; and again and again the engineer, in the first dim light of morning, came to see if their ill-omened predictions had been fulfilled. Sometimes he had to wait long, until he could see a tall white column of spray rise aloft into the morning air. Then he breathed freely, and shut up his telescope, and thanked God that his labour had not been undone. And as the morning advanced, and the light grew fuller and stronger, he was able to discern his shapely light-tower, standing, erect and firm, above the whirl of waters.

The Eddystone lighthouse.

The Eddystone lighthouse, as Mr. Smiles remarks, has now withstood the storms of a century, and at the moment we write it still occupies its advanced position, in front of the dangerous south-western coast, a remarkable monument to the genius and perseverance of its architect. At times, when the swell of the Atlantic rushes up the Channel with more than ordinary violence, impelled by a south-west wind, its tall pillar is shrouded in thick wreaths of spray, and its keen light-star for a moment is obscured. But the cloud passes, and again the welcome radiance streams across the waters, at once a guide and a warning to the homeward-bound. Occasionally a strong wave will strike full upon it, and its central portion, swiftly gliding up the perpendicular shaft, leaps, with one tremendous bound, over the lantern. At other times, a billow will break against it with a fury which seems to menace the security of its foundation. To those within, the report is like that of heavy artillery, and the windows rattle, and the whole building quivers from top to base. But the shudder which then runs throughout the lighthouse, instead of being a sign of weakness, is the "strongest proof of the unity and close connection of the fabric in all its parts."

"The Eddystone in sight!"

"Many a heart has leapt with gladness at the cry of 'The Eddystone in sight!' sung out from the main-top. Homeward-bound ships, from far-off ports, no longer avoid the dreaded rock, but eagerly run for its light as the harbinger of safety. It might even seem as if Providence had placed the reef so far out at sea as the foundation for a beacon such as this, leaving it to man's skill and labour to finish His work. On entering the English Channel from the west and south, the cautious navigator feels his way by careful soundings on the great bank which extends from the Channel into the Atlantic; and these are repeated at fixed intervals until land is in sight. Every fathom nearer shore increases a ship's risks, especially in nights when, to use the seaman's phrase, it is 'as dark as a pocket.' The men are on the lookout, peering anxiously into the dark, straining the eye to catch the glimmer of a light; and when it is known that 'the Eddystone is in sight,' a thrill runs through the ship, which can only be appreciated by those who have felt or witnessed it after long months of weary voyaging. Its gleam across the waters has thus been a source of joy, and given a sense of relief to thousands; for the beaming of a clear light from one known and fixed spot is infallible in its truthfulness, and a safer guide for the seaman than the bearings of many hazy and ill-defined headlands."

Usefulness of the lighthouse.

We find little record of Smeaton's engagements between 1759, when he completed his great undertaking, and 1764, when he applied for and obtained the appointment of receiver for the Derwentwater Estates.* It may be, as one of his biographers remarks, that, as yet, there was little demand in England for the constructive skill of so bold and able an engineer. Not but that there was work enough: for the highways were in a deplorable condition; in many districts intercommunication was rendered difficult by the want of sufficient bridges; in the commercial ports of the country dock accommodation was almost unknown; but England was then too poor, or her energies were too exclusively concentrated upon maritime enterprise and colonial extension, for her to undertake to supply these deficiencies on any extensive scale.

* These estates were confiscated by the Crown, on the death of the last Earl of Derwentwater,—executed for high treason,—and conferred by Parliament on Greenwich Hospital.

His engineering works.

His reputation, however, was gradually extending throughout the kingdom, and in 1760 we find him consulted by the magistrates of Dumfries respecting the improvement of the Nith. He was similarly consulted as to the lockage of the river Wear, the opening up of the navigation of the Chelmer to Chelmsford, of the Don above Doncaster, of the Devon in Clackmannanshire, of the Tetney Haven navigation near Louth, and the improvement of the river Lea; but the improvements he recommended do not seem to have been carried out, through want of funds. In truth, his first great engineering enterprise was undertaken in his own county, where he was employed in extensive repairs of the dams and locks on the river Calder; and he effected many important improvements in that navigation, which confirmed the general belief in his skill and judgment. At the same time he carried out extensive works on the river Aire from Leeds to its junction with the Ouse.

To Smeaton also is mainly due the recovery of the inundated lands in the Lincoln Fens, and in the low levels between Doncaster and Hull. The river Witham, between Lincoln and Boston, was still, it is said, a source of constant grief and loss to the farmers along its banks. It had become choked up by neglect, so that "not only had the navigation of the river become almost lost, but a large extent of otherwise valuable land was constantly laid under water."

At a still later period he undertook to improve the drainage of the North Level of the Fens, and the outfall of the Nene at Wisbeach. For this purpose he recommended the construction of a powerful outfall-sluice at the mouth of the Nene.

Other works in which he was consulted, and in which his engineering ability was signally manifested, may here be mentioned: the drainage of the lands adjacent to the river Went, in Yorkshire; of the Earl of Kinnoul's lands lying along the Almond and the Tay, in Perthshire; the Adling Fleet Level, at the junction of the Ouse and the Trent; Hotham Carrs, near Market-Weighton; the Lewes Laughton Level, in Sussex; the Potterick Carr Fen, near Doncaster; the Torksey Bridge Fen, near Gainsborough; and the Holderness Level, near Hull.

Old London Bridge.

In 1763, he was called upon by the Corporation of London to advise them as to the best means of improving, widening, and enlarging Old London Bridge. In order to accommodate the increased traffic on the river, two arches of the bridge had been thrown into one, but with the effect of so augmenting the rush of the water as to loosen the adjoining piers, by washing away the bed of the river under their foundations. The alarm was so great that few persons would pass either over or under the bridge; and the Corporation hastily summoned Smeaton, who was then in Yorkshire, to their assistance. On his arrival, he proceeded immediately to examine the bridge, and to sound about the foundations of the piers as minutely as possible. He then advised the Corporation to repurchase the stones of the city gates, which had recently been taken down and their material sold, and cast them into the river outside the startings, or buttresses of the piers, to protect them from the action of the tide. His advice was adopted; and simple as were the means suggested, they proved entirely efficacious.

Works on the Calder.

This method of checking the impetuous ravages of water, says Holmes, he had practised before with success on the river Calder. "On my calling on him in the neighbourhood of Wakefield, he showed me the effects of a great flood, which had made a considerable passage over the land; this he stopped at the bank of the river, by throwing in a quantity of large, rough stones, which, with the sand and other materials washed down by the river, filling up their interstices, had become a barrier to keep the river in its usual course."

Smeaton next appears in the character of a bridge-builder. The handsome bridges at Perth, Coldstream, and Banff were erected by him. With reference to the first of these, it should be explained that the Tay being subject to frequent inundations, it was requisite that great care should be taken with the foundations, which were laid down by means of coffer-dams. That is, a row of piles was driven into the river-bed, and round about and between them was thrown a quantity of gravel and earth mixed together, so as to render the enclosed space impervious to water. Pumping power was then applied, and the bed of the river within the coffer-dam was laid completely dry; after which the soil was excavated to a proper depth, and a firm foundation obtained for the piles. Piles were driven into the earth underneath the intended foundation-frame, and then the building was carried upwards in the usual way.

The Perth bridge.

The Perth bridge is a handsome structure, consisting of seven principal arches, and measures about nine hundred feet in length. It was completed and opened for traffic in 1772.

His success in this notable undertaking secured him a very considerable amount of engineering business in the North. At Edinburgh he found employment in improving the water-supply for that city; at Glasgow, in strengthening and securing the old bridge. Far more important were the works he executed in designing and constructing the Forth and Clyde Canal, which links together the east and west coasts of Scotland, the North Sea and the Irish Sea.

The Forth and Clyde Canal.

After a careful examination of the various lines which had been proposed for the canal, Smeaton strongly recommended the adoption of the most direct route possible, and suggested that the depth of the canal should be sufficient to accommodate vessels of large burden. Lord Dundas, the principal promoter of the scheme, adopted Smeaton's ideas, and took the necessary steps for obtaining an Act to authorize the construction of the Forth and Clyde Canal, which was accordingly commenced in 1768.

This canal runs nearly parallel with the famous wall of Antoninus, erected by the Romans to protect the southern Lowlands from the predatory attacks of the wild tribes of Caledonia. It begins at a point near Grangemouth, on the Forth, and ends at Bowling, on the Clyde, a few miles below Glasgow. Its length is about 38 miles, and it includes 39 locks, with an elevation of 156 feet from the sea to the summit-level.