Quivering with rage, Consuelo stood still.

Title: Caravans to Santa Fe

Author: Alida Malkus

Illustrator: Marie A. Lawson

Release date: August 18, 2025 [eBook #76701]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1928

Credits: Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Quivering with rage, Consuelo stood still.

A hundred years ago, in a valley that lies on the slope of flame-shot mountains, a little town of ancient crooked streets slept in the sun, entirely shut away from outside civilization—a bit of old Spain, lying in rare and mellow beauty in the mountains of the Sangre de Cristo. Beyond the Cordilleras lay other ranges of rocky, snow-capped peaks, and beyond these again stretched hundreds of miles of barren desert, succeeded by still other hundreds of miles of rolling plains—a land of red men and bearded bison.

Through the streets of the adobe-walled Villa, the town of Santa Fe, life flowed with a sluggish content or took siesta. At this moment it was taking siesta. The cook slept with her bare toes spread in the cool mud beneath a dripping olla, the wood boy and his compadre, the burro slept within a few feet of each other, the burro standing in the sun, the boy lying in the blue shadow of a wall. Doña Gertrudis Chaves y Lopez slept with open mouth, through which issued contented little whistles of escaping steam. Don Anabel Lopez himself slept, but not even sleep could relax the pride of his hawk nose, the defiance of his well-bred snore.

But Consuelo Lopez did not sleep; she lay in her bedroom, sulking. She was bored as only sixteen can be bored, and waved a naked foot in the air in rage. “Bestia!” she exploded, venting her angry thought. “Moribundos! The dead ones!” Reaching under her pillow, Consuelo drew out a silver case from which she extracted a cigarette. Slipping to a window where one long dazzling shaft of sunshine pierced a crack in the shutter, she held a small burning-glass over a wisp of paper. It flamed in a moment; the cigarette was lit, and she resumed her pose. A step sounded outside the door. Consuelo threw the cigarette disdainfully behind the bed, but the step passed on and she recovered it again before it had time to go out. It was fortunate that Doña Gertrudis was so insistent upon her daughter’s beauty sleep. Consuelo would be permitted to indulge her boredom undisturbed for another hour. A raging boredom she rather enjoyed, but not a languid one.

“They think it enough for me to sit here and twiddle my fan. To sit here and listen to Manuel! Tink-a-tinkaa, tink-a-tink, Thy heart so true! Caramba! I know everything he can say by heart. Rather would I marry myself to one of the rope-haired trappers or the barbaric Yanqui caravaners that come over the plains a-trading. They are men. What if they do lack cultivacion, and cannot roll their r’s. They appeal to me. Yes!

“Ah, would but Don Tiburcio Garcia arrive, with something of the outside world about him, and the latest news from Chihuahua and Mexico City. And clothes, ah, what clothes! What will he think of me?”

Consuelo stretched herself reflectively upon the bed, tossing aside a hand-woven coverlet of drawn threads, and lifted the bare foot to catch a breeze stirring through deep-silled windows. She took from the carved chest of drawers beside her a wrought-gold mirror studded with pink semi-precious stones and carefully regarded her face from this angle and that. The sole imperfections that appeared within its frame were those of a cracked mercury back. Consuelo considered and approved the mirror’s various reflections. They were more pleasant than her thoughts. In fact, her mirrored face was all that she cared about at the moment. Hers was that most charming of Spanish types, which in profile is straight-nosed, delicately cut, but which in full face appears childish, the nose short, a trifle broad, the eyes large and heavy-lidded, the lips full, petulant. There was strength in the squaring of the jaw and in level, heavily marked brows, scowling now with her rebellions.

Everything one wanted to do was prohibited—to dance with the caravaners, for example. Only disagreeable things were permitted. How could one consider one’s suitors seriously if they were like Manuel, her second cousin, so eager that he bored beyond insults? He would be on hand this afternoon, singing his interminable verses. Well enough to have him as a sort of permanent court, even though Luis did make all sorts of fun of his cousin. But then, Luis was critical of everything; brothers generally were. He’d be a bit more respectful when he heard about Don Tiburcio! A caballero from the City of Mexico, a veritable Spanish grandee? Consuelo did not dream, after Don Tiburcio had visited Santa Fe the summer before, that he could ever again be interested in her. Yet he had sent word to Don Anabel that he was coming, and had made special inquiry for her. She blushed with embarrassment when she thought of the outrageous manner in which she had treated Don Tiburcio; she’d slapped his face when he raised her hand and was about to implant a kiss upon it!

But then, she was only a little girl last year. Now she could appreciate what it meant to have so courtly and traveled a suitor. In a few days his pack train should arrive from Chihuahua and life would be vastly more exciting. There would be new clothes for her, too. Kid shoes—oh, she would be furious if they were not lefts and rights—brocade, perhaps some sapphire earrings.... It was time to dress for the afternoon. Still Consuelo lay looking idly from her mirror to the windows. Who knew at what moment one might hear the call, “The caravan is coming!” and she, with every other girl and woman in Santa Fe, would dash to window or door to gaze at the Yankee traders as they rode into town. Then there would be the delight of new goods to buy from those unknown lands beyond the rising sun, new faces to see, new thoughts to think upon.

The very thought brought Consuelo to her feet. Throwing off the ancient blue Chinese mantle brought in for her from the Orient by her father, she tried the effect of a high comb in her hair. Dipping a wide-toothed tortoise comb into the tepid water that still stood in a heavy silver washbasin by her bed, she ran it through the dark waves till they curled crisply, with a shining order. Pulling at the sides till a few loose ringlets detached themselves, she set the comb atop the coiled mass, draped over it a white lace mantilla, and stood entranced. She would wear it to the baile when the caravan came.

Somehow a greater thrill lay in the advent of the lean, ruddy strangers from America than in the coming of the Spaniard’s train. From the arrival of one caravan to another she could scarcely wait—the creaking wheels, the clatter of chains, the shouting and talking, the strange English tongue. She introduced herself before the mirror and smiled demurely at the imaginary gentleman she was meeting.

Then tossing comb and lace aside, she threw herself on the bed again and shouted, “Fay-lee-cita! Fay-lee-ee-cita!” It was some time before Felicita, Consuelo’s peon slave, appeared; she was met by a small red shoe thrown at the door, but hitting the girl squarely as she entered the room.

“Why do you keep me waiting for my water every single day?” Consuelo was shouting; but she stopped now, a bit abashed. “How could I tell you would come this time so soon? But I must be dressed, quick!” She had suddenly remembered that at five some young trappers would be down from Taos to talk with her father on business, and she wished to be dressed and sitting in the patio, from where one could see and be seen when visitors entered the zaguan and sat with Don Anabel in the living room.

Felicita backed out of the door and fairly ran after the water, and Consuelo began to throw clothing about the room, already disorderly, but quaint and full of charm, a curious combination of luxury and crudity. Large and high-ceiled, its adobe walls were tinted a salmon pink; the two windows, square-paned, deeply recessed by the three-foot walls, were curtained with lace, and the great carven bedstead was draped with rose-red damask hangings from Spain. On the high chest of drawers were a pair of silver candlesticks, and above hung a heavily framed mirror of old Spanish make. Before a small corner fireplace with an Indian chimney lay a thick and enormous buffalo skin, and the rough board floor was strewn with other peltries. On each side of the bed lay a tinted white Angora sheepskin. At the foot of the bed stood a high carven chest in which lay Consuelo’s clothing, gowns brought over many weary hundreds of miles, packed securely on the backs of burros that wound mountain passes, crossed ravines, and plodded over deserts in the long journey up from Vera Cruz, the eastern port of Mexico.

There were many shawls, black Spanish lace from Seville, a bright embroidered peasant challis, gold and salmon flowers on a white ground, fine merinos and cashmeres of European peasant patterns. Consuelo chose now a white dress of sheer batiste, embroidered heavily in white, full-skirted, with a short plain bodice. She donned the red shoe that still lay under the bed, and when Felicita had brought her the other from the doorway, she permitted the peon woman to throw the flowered shawl over her shoulder, and stepped out into the corredor. Then she turned impulsively and ran back. Snatching a silk scarf from the bed, she draped it over Felicita’s head.

“Here. Did I hurt your tummy? Take this.”

Her mother was waiting for her in the living room. Across the table from Doña Gertrudis sat Manuel, plucking his guitar tentatively, persuasively. Not everyone in New Spain rose when a lady entered the room, but Manuel always stood when Consuelo appeared in the doorway. Her mother did not glance up from the altar-piece which she embroidered; it was the only work that her plump fingers had ever been engaged upon. Doña Gertrudis was fat, small-boned, her chin lost in the amiable creases which had engulfed the beauty of her youth. In spite of the heat of the August day, she was dressed in the favorite black of the Mexican woman of Spanish descent. Heavy rings of yellow gold, set with garnets, roughly cut but of marvelous color, covered her fingers, a bracelet to match weighted her small wrist, and weighty gold earrings pulled down the lobes of her fat little ears. Her dress of black silk was voluminous and hung straight from her shoulders,—a fact which the shawl about her shoulders could not hide.

“And we shall have roast young pig, joint of young antelope, guinea-fowl, when Don Tiburcio arrives,” she was saying as Consuelo came in. “Manuel has a new copleta, Consuelo querida, composed specially for you, today,” she went on. Doña Gertrudis had been a famous coquette in her own time, and although the announced visit of Don Tiburcio Garcia had opened up wider vistas matrimonially for her daughter than New Spain had previously afforded, she had a family fondness for her cousin’s son and was too diplomatic to slight him.

Manuel, taking silence as assent, was already strumming, and intoning his new copleta in a plaintive nasal tenor. But his presence and his plinking were quite ignored by the girl, who swished to a chair near the window and looked steadfastly out, leaving Doña Gertrudis to keep time with her foot and dream of love.

As to Don Anabel Lopez, hidalgo, master of the house and lord of vast lands granted to his family by the Spanish crown a century and a half before, he was not at all pleased with the prospect to which Consuelo looked forward with secret delight and anticipation. The coming of the Yankee traders across the plains with their freighted caravans of mules and covered wagons, was an event to be tolerated only for the gain it brought. Bitterly Don Anabel resented the intrusion of the hated “English” into the province conquered by Spain two centuries before.

Yet he could trade the pelts of beaver, lynx, fox, the robes of buffalo and of deer, brought in to his post by trappers white or red, at a profit that would have made Connecticut Yankees wince had they known that he himself had acquired them for a handful of tawdry merchandise, and stores that were cheaper from New Orleans and St. Louis than from Vera Cruz and Mexico City.

On this warm and sunny afternoon of late summer Don Anabel stood before the door of his store and warehouse, scowling. He could look up the little winding street to the Mountains of the Blood of Christ, as they had been passionately and piously named by the early Conquerors, and red-streaked they were now even in the yellow light of the afternoon sun. Don Anabel looked to the passes that led north and east; he was perturbed.

“Luis,” he called sharply to the young man who lounged through the doorway, a languid cigarette hanging from his lips, “I see a rider coming down the trail from Lamy. Can you see any one following? I believe it must be either an advance of the caravan arriving over the Santa Fe Trail or else the trappers I expected down from Taos, coming by the lower route.

“I only hope it is the trappers, for I would like to get their business over with before the caravan arrives. This Gringo trade from beyond the mountains has cut so largely into our own rightful business within the province that we must make whatever profit we can out of the goods they take back with them. The peltries they buy are cheap at the price, anyway.”

“What is the Governor charging them a load this year?” asked Luis, who was rather a handsome young fellow of eighteen or twenty, with a straight nose and loose, full lips.

“Just what was charged two years ago when the first caravana of wagons entered the territory—five hundred dollars each wagon-load; and, Santa Maria! it is little enough.”

“Little indeed,” assented Luis, indifferently. “When does the excellent Don Tiburcio arrive? Have we been taming the little sister so that she won’t scratch this time?”

“I expect Don Tiburcio at any time now. That may be the dust of his caravan. He is bringing camlet cloth and silken grogram, shawls, combs, white sugar, ammunition, the usual merchandise. And Heaven send he arrive before the Americanos with their cargo from the United States, and have his goods disposed of.”

“And my linen shirts?” Luis inquired with more animation than he had yet shown. He followed his father back into the storeroom.

Don Anabel nodded, a trifle annoyed. “I believe he brings linen. But with the four frilled camisas which I gave you at Easter-time you should have no urgent need for more shirts at present. By the way, you do not wear the ruby ring which your parents gave you at Christmas.” He eyed his son keenly. Luis flicked an ash from his cigarette and replied, evenly: “Not all the time. It is a trifle large, and much too fine a stone to run the risk of losing.”

“So I thought when it was presented to you,” remarked Don Anabel, drily. “How does it happen, then, that I find it on the finger of the gaming friar of Albuquerque——?”

Luis flushed. He did not reply, but looked away in embarrassment.

“The usual thing? Tell me no lies, Luis.”

“I exacted the promise that I might redeem it, and expect to do so very shortly now.”

“Well, I trust that you will. But not from the fray. Come to me when you are ready.” Don Anabel drew his hand from his pocket and, opening it palm upward, showed a splendid garnet ring, set in dull heavy gold. “It has cost me three hundred duros to get back your pledge, several times the amount of your losses; but it is too fine a gem to have imported but to lose.”

His words were cut short by a commotion outside in the streets, and shouts coming down the canyon road.

“They are coming! They are coming!” shouted ragged children capering in the roadway.

“Who comes? Who comes?” the cry went up from doorway and street. People poured out into plaza and lane, siestas abandoned for so great an occasion.

“A caravan, from Mexico.” A rider came galloping down the street and drew up in a cloud of dust before Don Anabel’s warehouse. He leaped from the sweating horse, bowed low before Don Anabel, and spoke, “Don Tiburcio Garcia follows on the trail, and his caravana is but a short distance behind him.”

Hastily Don Anabel sent a messenger to his house with the news, but already it had traveled ahead, and as the entire establishment had known for days just what was to be done for the guest from the capital, all was immediately thrown into a fury of activity. The great open square in the center of the Villa became suddenly alive, the loungers before the palace of the Governor all hurried up the street; blanketed Indians from the pueblos followed in leisurely dignity; girls and women flocked to windows and doors; and shouting filled the air.

“Here comes the cavalier from Mexico. The cavalcade of Don Tiburcio de Garcia is arriving.”

Now that the moment was at hand, Doña Gertrudis flew out of her customary placidity like a nervous ground bird fluttering about its nest. She toddled hither and thither on her ridiculous little feet, scolding, all but weeping; she smelled the distilling coffee, threw up her hands, shrieking. “What miserable café! Tepid water!” The beverage was in reality almost a pure caffein that had distilled and dripped for two hours, a potent drug.

“And make the chocolate thick, do you hear, Concha? Three eggs in it—three—and beaten a half-hour.” Concha knew well how to make the chocolate, the favorite drink of Spaniard, and of ancient Aztec before him. It was her special province to make it, rich, thick, sweet, beaten like a mousse. Doña Gertrudis tasted the red-hot chili, ordered the house servants this way and that. The corral behind the kitchen was filled with the squawking of unfortunate fowls being chased to their destiny—arroz con pollo (chicken with rice).

Having thoroughly demoralized the slow but eventually sure processes of Lupe, the cook, Doña Gertrudis bustled into her bedchamber to put on more jewels and daub a fine white flour over her cheeks and neck, while she chattered like a parakeet through the doors to Consuelo, who had abandoned Manuel for her mirror.

When the mirror had told her that the necklace of tawny topaz was prettier with white than was the opal chain, she lingered till the sound of horses and a company of men so excited her curiosity that she had to pull back the persianas and peer out. Herded by the shouts of the arrieros, a caravan of a hundred mules and burros was being crowded into the plaza. Had they brought her new satin shoes and brocaded skirt? There was Don Tiburcio! In the high hat, a wrought leather jerkin over a gold-embroidered vest, a wide copper-studded belt, and as he dismounted a bit stiffly from his lathered horse Consuelo took note of beautiful tight-fitting trousers, fawn-colored, over which were riding leggings of Mexican leather. All this in a flash, then Consuelo’s eyes swept to the travel-worn face of the southern Don.

A true son of the Conquerors of the New World was Don Tiburcio de Garcia y Mendoza. A dark, lean man of thirty, who looked ten years older, he was tall, and hatchet-jawed, with a nose of perfect aquilinity, and a thin mouth made somewhat prominent by large even teeth. The mouth seemed harsh, cruel even, till it broke into a smile. His brow was high and narrow, and his well-cut ears lay close to his aristocratic head. Don Tiburcio was filled with the adventurous spirit of his forbears or he would not himself come trading at the head of his caravans up the Cordilleras from Mexico, enduring every sort of physical hardship and running the gantlet of fiercely treacherous Indian tribes.

His father, Don Diego Alvar Roybal de Garcia, never left his broad estates in Guadalajara not even to travel north to the immense cattle ranches of the Garcias in Chihuahua. The supervision of all that he left to his son, and as the caravan journeys to the north proved highly gainful, he made no objection to them. Romance called to the young man. The lure that first brought the Spanish Conquistadores up through this country had drawn him—gold and gain, perhaps undiscovered treasure waiting there—and, indeed, at the end he had found beauty, too. Nowhere in the southern provinces had Don Tiburcio seen a face to compare in his estimation with that of the little hoyden who had slapped him the summer before. And to speak truthfully, it was the conquest of that untamed child which had lured him back this time over the hot stretches of desert between Santa Fe and Chihuahua as urgently as the money to be gained in trade.

Night had fallen before arrangements for the caravan had been disposed of and the weary pack animals relieved of their cargo. Don Tiburcio refreshed himself and removed the stains of travel, making ready to present himself in the candlelit sala of Don Anabel’s house and to meet the ladies. He made a fine figure in his velvet short jacket, his silver-buttoned breeches, and a pair of excellent boots with inch heels. He was taller than either his host or Luis, both of whom wore their best heeled boots also, and their finest shirts of frilled white linen, their handsomest serapes and sashes, brought from Mexico the year before. Father and son stood until their guest had seated himself in a heavy low chair. A slippered servant brought small silver goblets and a pitcher, and Don Anabel poured a fragrant drink. “My peach brandy, señor,” he offered. “Saludes [Your good health]! It seems to me that it has an exceptional flavor. The peaches are from the Valley of the Rio Grande.”

The visitor from Mexico sipped critically and settled down with the appreciation of the connoisseur. “It is quite perfect, señor. And well I remember the most excellent grape of last year.”

“You shall taste of a still older vintage at supper, Don Tiburcio.”

“And is not that the indiana we brought you last year?” Don Tiburcio nodded at the red calico tacked shoulder high about the whitewashed walls to protect the backs of those who sat around the room. The simple hangings looked, in the glimmer of yellow candlelight, like a rich tapestry, a proper setting for the heavy, brass-studded chairs, for the florid oak table, the massive candlesticks. The rough floors were covered with buffalo robes and with rich Mexican shawls, serapes, and serapes also draped the sofas at each side of the room. On the wall above the mantle of the low fireplace hung a painting, dark and old and cracked and priceless. Don Anabel prized it above all his possessions, claiming it was a Murillo; and because of his affection for the painting, which he related had been brought over a century and a half before, his family also venerated the canvas. It was a Madonna and Child, with cherubim. Don Tiburcio looked for and found the painting.

“Two possessions of yours I would like to take away with me, Don Anabel,” the Mexican visitor said with that air of courteous compliment of the grandee.

“Mi casa es suya, señor [My house is yours],” Don Anabel was repeating the formal phrase of Spanish hospitality.

“This painting is one,” Don Tiburcio continued, knowing well that it was almost the last thing in the world that Don Anabel would part with, “and the other——” His words remained unspoken, for at this moment the ladies entered the sala, Doña Gertrudis first, billowing in importantly, glowing with rose garnets and pearls. Consuelo followed demurely, decorously, with lowered eyes, yet inclining her head to Don Tiburcio’s bow. Within her bodice her heart was beating furiously, but from the tail of her eyes she watched the distinguished visitor.

“It is a great pleasure to see you once again, señora, and you, señorita. Your servant.”

“Igualmente, igualmente [Equally, equally], señor!”

“And now let us sup.” Don Anabel led the way toward the dining room, which was at the rear of the house, near the kitchen. They passed through the entrance hall, out into the patio, and crossed to the other side. Don Anabel’s house, like all large Mexican houses, was a square built about an inner court, into which most of the rooms opened. Into a long cozy room they stepped, where dining and serving tables were heaped with the efforts of the good Lupe. Every dish was of purest silver, plate and goblet, bowl and salver; candlelight; linens of finest drawnwork; a young roast pig served whole on a massive platter; chicken and rice flanked with squash; stewed corn; melon cooled in the fountain; wines from the grapes of the Tesuque Valley near Santa Fe; pickled watermelon; apricot pastries. It was a scene of mediæval plenty. The guest tasted everything, to Doña Gertrudis’s satisfaction, and ate well, slowly, savoring the feast after the rough fare enforced during the long journey up into the province.

“I am reminded,” he addressed Doña Gertrudis, “that I captured far to the south of here, señora, a number of young javalinas [peccary], and I have brought one alive for you. I think you will like the flavor, for it is even more delicate, if possible, than the shoat here.”

Thus the talk turned to his voyage. The Indians to the south, while not on the warpath, were far from being peaceful. Acoma, that strange Indian pueblo perched upon the high rock, held a deadly hatred for all Spaniards, the visitor said, and there were, southward a few days’ travel, bands of plains Indians that strayed over from eastward, who were more fierce than any he had yet seen. But the country was rich and fertile. Corn he had seen fourteen feet high; peaches that would not enter a pint cup; and beaver enough to line all the capes of all the crowned heads in Europe. He held the company enthralled with brave tales of many perilous escapes upon this journey, and strange sights that he had seen in the desert.

When he had left the northern part of Chihuahua behind and was looking for the Valley of the Rio Grande he had somehow missed it, his scout not having recognized the river bed, in that season bone dry, and he had gone some miles to the east, following up a strange spur of mountains which resembled the carven spires of a church or the colored pipes of a great church organ. Not finding a pass over this rocky spur which lay between him and the river valley, he and his caravan had kept along the foot of it, going northward for perhaps sixty leguas. Then they had come upon the strangest sight that ever it had been his lot to behold in the desert country. At first Don Tiburcio related he had thought he was seeing a mirage; it seemed to him he saw snow. As he went nearer and nearer, and snow it still remained, he doubted but that he must be mad. Yet when they had reached the place there rose before them a great hill of dazzling white stuff which had the brilliance of snow in sunshine, and which the light desert breeze blew off in a fine white mist. And this curious salt, for such he deemed it to be, drifted in waves, and whatever was lost in it was nevermore found—so the Indians whom he had encountered above the spot had told him. And in those mountains which he had skirted was silver, aye, and even gold, so vowed a Pueblo Indian from the place called Isleta!

“And you did not remain there to discover whether or not it were so, señor?” inquired Luis, aghast.

“Ah no! We were weary, and the animals needing water, and there would be gold aplenty—and other matters more important at my journey’s end.” Don Tiburcio replied, suavely, and looked directly at Consuelo.

Flushed with excitement, she flashed and sparkled now, plying the Don with eager questions about his trip. And so the evening passed, and when she lay upon her pillow late that night Consuelo wondered if with that lean, fascinating caballero lay her future and her fate. Impersonally she dreamed, stirred from the monotony against which she had been rebelling; but somehow her fancies were not real to her, no pictures of the future arose to her sleepy brain. Yet as she slipped into a dreamless slumber that future was shaping, moving toward her as rapidly as the lumbering feet of oxen could move.

The city of New Orleans, even after the French sold it to the United States, remained a place of gilt-braided social life, where the brilliant creole “quality” held bright levees. It was, too, a port of intrigue and of commerce that swirled about the wharves and up and down the great Mississippi.

Had the society that frequented his mother’s drawing-room in the lovely old French city not been so brilliant, the ladies so entertaining, the gentlemen so distinguished, Steven Mercer would have rebelled quite openly against a life that seemed to him mainly frills and lace. He was happier on the river than anywhere. For one reason only would Steven stay at home, his keeled boat moored idly at a delta wharf: to hear epauletted gentlemen recount the thrills of the War of 1812; to listen spellbound while naval celebrities who had been with Decatur told of that immemorial engagement in the Tripolitan harbor. That had been in the year of Steven’s birth. It was a bitter disappointment to a boy of seventeen to reflect that those days were over.

“Steven prefers combat,” his mother lamented; “now that there are no more wars, he wants to run away to sea, to trade, I am sure!” She was always afraid of this vulgar reversion.

“Why not?” Hamilton Mercer would reply to his wife. “Steven is a man grown. This country is new. It breeds men.” He looked with pride on his son’s six feet, on the breadth of him. When Steven was twenty-one he would take him into the business of Mercer & Co., the largest mercantile importing house in Louisiana. Let him do as he wished until then, aside from his studies.

But his gay little French maman made many demands upon Steven. She was exacting as to his manners, but for the rest did not trouble about whether he roamed the plantation or studied his Greek. As a child she had been content to turn him over to his governess or his tutors. Now that he had grown into a tall, muscular youth, and a handsome one, he must attend her levees, escort her at times. And although Steven admired his mother very much and had been brought up to the life, it must be confessed that he preferred his father’s wharves to his mother’s drawing-room.

Quick enough at goods and figures, still he went less often to the offices of Mercer & Co. than to the riverside. Yet trade was already claiming him for her own, to tread in the footsteps of his paternal ancestors—ship captains, merchants, and merchant owners of good vessels all—whose blood stirred restlessly in his veins, calling him to new markets and to adventure.

Down on the wharves, where vessels from strange ports were putting in with their merchandise for the warehouses of Mercer & Co., that was where Steven had always loved to be. Where the negroes talked in their own river talk, and fought the English-speaking blacks of the West Indies. Where one could talk in villainous Portuguese with equally villainous-looking, ear-ringed sailors, with salty first mates from Lisbon, Calcutta, Hong-Kong, Liverpool. Across the Gulf to Mexican ports went their cargoes, and up the river to that wide inner country searched by the sinuous fingers of the great Mississippi, the Father of Waters.

Scarcely a quarter of a century had passed since Napoleon had sold to the United States “Louisiana,” the French territory stretching from the Mississippi westward to the Rockies, and from the Gulf of Mexico northward to Canada; a buffer against the British which Napoleon himself could not hold and sold for a song. France had counted on Spain’s keeping the American colonists out of the West, and had secretly ceded her vast territory to the Spanish crown, but British traders from Montreal dispatched their bateaux down the Mississippi and up the Des Moines and Arkansas Rivers, undisturbed by the Spanish galleys sent against them. Spain abandoned the land she could not hold.

She thrust it back upon France, busy with the wars that Napoleon provided for her at home. Hence New Orleans became an American port. The mouths of the mighty Mississippi were no longer closed to the ships of the United States. The inland empire which the great stream watered, bottled up no longer by the Spanish and French, was filling rapidly with the land-hungry settlers of the new United States. It was less than fifty years since the Revolutionary War, and yet already the thirteen original Colonies had expanded across the Alleghanies, west to the Mississippi. Even under French occupation there had been more Americans in St. Louis than French.

At New Orleans docks bale after bale of goods from New York or from Charleston, from Massachusetts or from New Jersey, was shifted to the new keeled boats of the river. Up the Mississippi to St. Louis and beyond they went, branching off upon the Arkansas to push into the west. And down the river, borne with the incredible speed of that mighty current, came the flat-bottomed bateaux, laden with pack after pack of lustrous furs.

“Where are they going?” Steven always asked the river captains as he watched the new boats, that went by steam, loading for the upstream voyage. “To the Oklahoma fur-traders at Fort Gibson, to Leavenworth for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company,” or, “For the Indians, for New Spain.”

Fascinated by the broad bosom of the river as he was, Steven was a dozen times on the verge of running away up the Mississippi to see for himself the tribes of Indians living a wild free life on the plains. Something always happened to prevent. His mother had had a fête champêtre at their country place at Pas Christian the last time he was so tempted. That was when he was thirteen; and the country beyond still remained a mystery.

Persons of interest and importance came sometimes to the offices of Hamilton Mercer as well as to the soirées of Madame Mercer. And on the day that Steven arrived at seventeen, and at a restlessness that could no longer be endured, two such were destined to present themselves at the merchant’s establishment. Hamilton Mercer had gone up the river to Pas Christian to oversee his plantations, and Steven was attending to some minor matters of business.

He found conversing with Mr. Morley, his father’s chief clerk, a dark-bearded Frenchman in the habit of the voyageurs who came down the river at the helms of their fur-laden bateaux. The man’s appearance and dress fascinated Steven. He waited around until Monsieur Delmar was presented to him. The Frenchman represented a group of Western traders and was arranging for a large shipment of merchandise of a commoner sort than that usually handled by Mercer and Co.

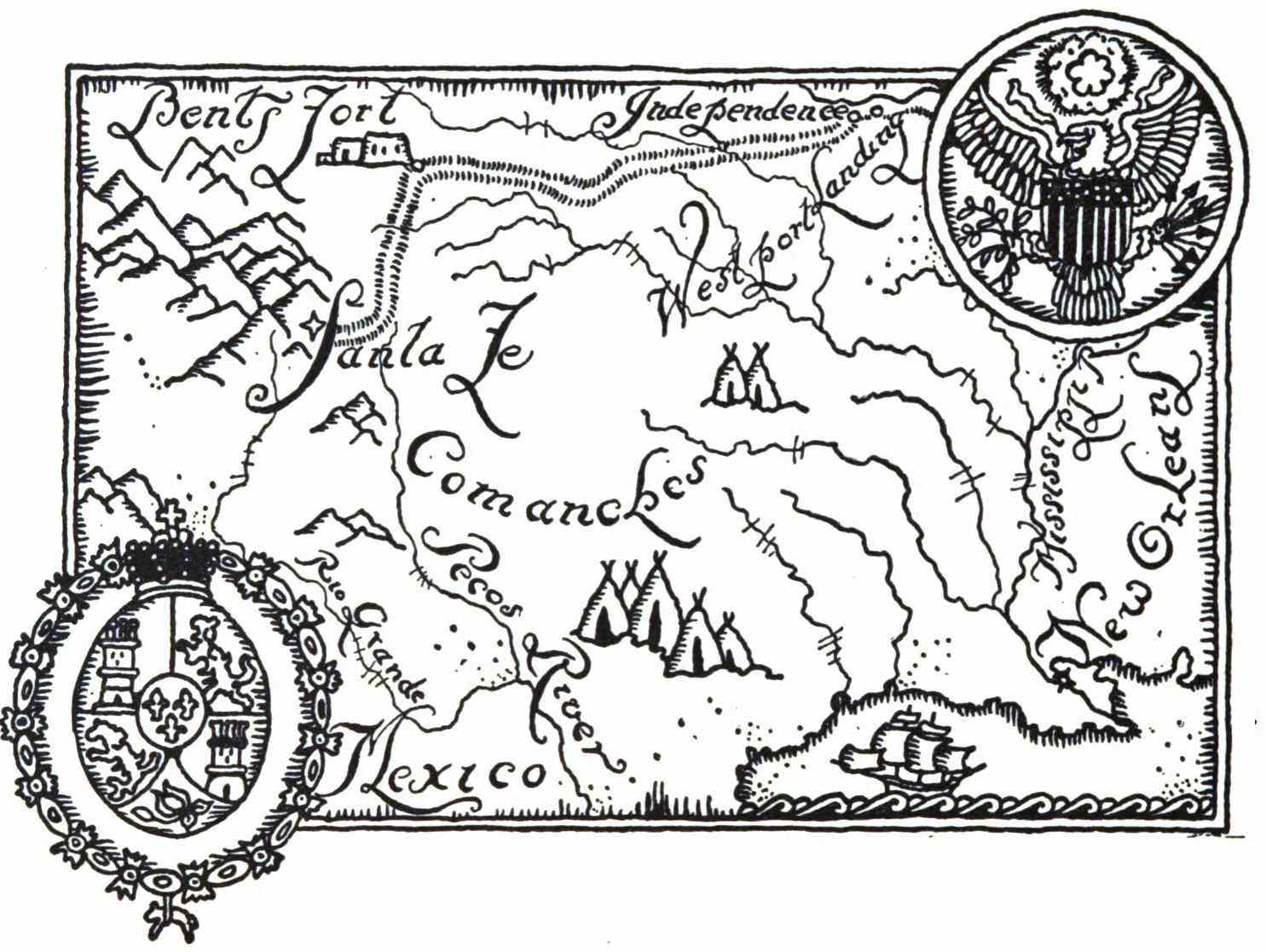

It was for the far Western trade, he said, in Mexican territory. The customer told of the commerce that had grown up during the past four years with New Spain, that province of Mexico; a vast, far territory, lying a good five months’ travel away, beyond the Rocky Mountains. Great caravans were crossing the continent every six months, he said, carrying thousands of dollars’ worth of merchandise into New Mexico, to the Villa de Santa Fe. Last year the government had built a new fort way up above St. Louis, upon the Missouri River, just to protect the people from the Indians.

The route to the West lay from this Fort Leavenworth in the Kansas country, to Santa Fe in Mexico—a three months’ journey, more or less.

“So soon as this goods I buy now reach the place from which they start,” Monsieur Delmar explained, “the caravan will set out. Many wagon, maybe twenty, thirty, forty—and mules. A big train, so to be safe against those Indian who fight across the plain.

“This year my fr’en’, Colonel St. Vrain,” he told them, “build with the brothers Bent a large fort and trade station in that Mexican country, on the River Arkansas; safety is there for les voyageurs.”

The Frenchman was eager to be on the return. He had come down the river from St. Louis at the rate of from fifty to a hundred miles a day, borne on the bosom of powerful currents, but it would take longer than usual to ascend the river, swollen as it was with the melting snow and rain.

Under the fire of Steven’s eager questions the Frenchman expanded on his theme. It was the tale of the Trail that he told—the Santa Fe Trail that watered with blood the growth of an empire to the west. Attacked by savage red men on the long overland journey, oftentimes at the end of the Trail thrown into prison by hostile Spanish governors, still they came, trader and trapper. “Some day, by Gar! we see who own that land.”

Steven sat entranced while his carriage and horses waited below. This was better than stories of the past; it was going on right now. This was adventure, a life for men. This was a conquest that lured him. He knew then that he must ask his father to send him with a shipment of goods across the plains.

“Could I join the caravan that will leave this spring?” The request came almost before he realized it.

“Pourquoi pas?” Monsieur Delmar would give the boy a letter to Colonel St. Vrain. The colonel would take him in his train without doubt. The Frenchman was leaving New Orleans at once, the following morning, and the letter was therefore written upon the spot, and Monsieur Delmar took his departure. With the missive thrust into his pocket Steven prepared to leave the offices and return home to wait his father’s arrival. They would talk the project over.

As he donned the tall hat of the dandy of the day, Mr. Morley rapped, ushering into the room a gentleman who wore a wide hat pulled down over his eyes. A dark cloak thrown over his shoulder was held across the lower part of his face in spite of the warmth of the day.

“You will see the gentleman?” inquired the courteous Morley.

The visitor waited until the door closed behind the clerk, and then, without removing his hat or releasing his hold on the cloak clutched beneath his chin, took the chair Steven proffered.

“Señor,” he began in Spanish, “I expected to see a grown man, pardon, and you are but a youth.”

“You are looking for my father, sir,” Steven replied. “I am Steven Mercer, a sus ordenes, at your service,” for Steven spoke Spanish as well as French. He bowed. “May I not serve you in my father’s place?”

At this the visitor removed his hat, threw back his cloak, revealing a long dark face with an extremely high forehead. “Señor,” he repeated, “I am Gomez Pedraza, recently elected President of the Republic of Mexico”—Steven gasped and rose to his feet—“and still more recently abdicated. I am fleeing to England because military force and the machinations of my opponent have forced me from the position to which I was rightfully elected. I have but a short time here in New Orleans, and, to be brief, I have a favor to ask of your father. I have been assured by faithful friends that he is a man of the utmost probity, and”—he eyed Steven keenly—“I am inclined to believe that one may repose the same confidence in the son.”

Curiously affected by the statement of Señor Pedraza, Steven was actually trembling as he replied, “Señor, I will try to serve you as my father would were he here, and I beg of you to tell me in what way that may be.”

“I wished to learn,” replied the visitor, “whether your father is engaged in an expedition of trade to our northern province of New Mexico. There is an overland route from this country, the Santa Fe Trail—you may have heard of it—over which much goods are being carried to our northern territories. Has Señor Mercer dealings with any trader in whom he has implicit trust—one who is trading with New Mexico?”

“My father himself does not send goods to the West,” Steven replied, “but he sells to the merchants engaged in trade on the prairies and at the fur-trading stations. Just today he has supplied enough for several loads to a buyer for the traders to New Spain.”

“Do not say New Spain,” interposed Señor Pedraza. “The province is New Mexico. But, alas! Mexico is less independent since she threw off the yoke of Spain but six years ago than she had been for two hundred years under the Spanish vice-regents. To return to my mission, however—is there, then, no chance of your father sending any of his own men over the plains? For I have a mission that I would intrust to him.”

“Yes,” answered Steven, boldly and without a moment’s hesitation. “I myself am going to take the trip. I shall probably travel with the caravan of one of the great traders of the plains.”

“Then”—the deposed President of the troubled country across the Gulf leaned impressively nearer the young man—“then, Señor, will you accept the mission? Will you carry a dispatch for me to one whom you will encounter at Santa Fe? When he will arrive I do not know—sometime within the next few months—but the message must be delivered into his hands. His name is upon the inner envelope, which you will discover upon your arrival. It is a matter of great moment to Mexico.”

“I will do it, señor.” With the impulsiveness of youth Steven rose, accepting with no further ado a mission of apparently grave importance. The two clasped hands.

“When will you be leaving?” Pedraza lowered his voice.

“As soon as may be señor. It will take time to make all arrangements, but the caravan leaves, so monsieur tells me, sometime in the spring, and as it is now January I shall have to make haste.” As the words fell from his lips Steven felt an inner exultation, coupled with amazement, that this could indeed be he. To take upon himself such a decision, without so much as consulting his parents, without obtaining his father’s permission! Why, he didn’t even know whether he could have any merchandise! But the desire of youth overruled any other consideration.

The deposed President of Mexico drew close to the boy. “Señor, you are young.” He spoke in a low voice. “But I have the confidence in you. Some day I shall be returning to Mexico; then, you may be sure, the interests of the American traders from New Orleans shall not be slighted. Señor, adios!” He thrust a sealed letter into Steven’s hands and, once more muffling his face, opened the door before which an attendant awaited him, and took his departure.

Steven stood before the closed door, his blood singing in his veins, the packet already hidden in an inner pocket. There was no doubt about it now. He was cast for adventure. It was as good as done. He hurried home to the birthday festivities in his honor, and many an older soldier of fortune that night envied his youth, his shining face, seeing in him the potentialities of fresh achievement.

“And as to your brave days of eighteen twelve,” cried Steven to the toast of the gilt-braided officer, “we are living in brave days. There is plenty of work for a man of mettle today, too——” He caught himself, lest some word escape him. The evening passed at length. Steven lingered in his father’s study.

The thing must be talked over. All Steve’s instinct was to pack his luggage and depart; but he was too well brought up, too faithful, seriously to consider such a course. Of course, his mother would say no. His father would have to be relied upon to win her over. But to win his father’s consent. Out with the question! that was the only way.

“Would you consider, sir, sending a wagon of your own for the trade upon the Western prairies?” he began, most business-like.

Hamilton Mercer considered. “Why, no, Steve, I’ve never leaned toward making any investment there,” he replied, slowly. “The hazards are too great. And although the rewards are said to be fabulous, I know personally no one whom I would intrust with the handling of several thousands of dollars’ worth of investment.”

“How about myself?” Steven looked straight at his father, meeting his eyes coolly enough, albeit with a rising color and a pounding heart. Mr. Mercer rose in astonishment; he considered some moments before replying.

“Steven, no, my son. I do not think that you are prepared for the hardships, the enmities, the dangers, of such pioneer enterprises. I could not say that I would outfit a caravan for you.”

“Very well, sir.” Steven took the rebuff quietly, hiding his acute disappointment. “But a man must know life sometime.” That was all there was to the conversation. Two days later Hamilton Mercer found a note upon his study table. “I have gone, father, to join the caravans leaving from Independence. Tell maman not to have any worries about me.” And so Steven Mercer had run away, not to sea, but to follow in the wake of the prairie schooner.

Nearly three months later a tall youth, with reddish-blond hair, a straight nose still peeling under the blistering rays of the river sun, deep-set blue eyes, and an enviable burn, stepped off a river boat at Westport Landing. He carried two heavy bags, while a small darky struggled after him with another. Steven had been fortunate in catching the American Fur Company’s steamer which was plying the river between New Orleans and St. Louis.

Arriving at St. Louis, he had had to disembark and continue his trip by bateau. The freight destined for Fort Leavenworth and for Independence had been loaded aboard the flat-bottomed river boats, and the slow pull upstream begun. Steven had learned, on the afternoon after his conversation with his father, that at midnight that night one of the Astor Company’s steamers would start up the Mississippi, laden with provisions. He determined at once to take it. There remained but a few hours before it left and his preparations had been hurried and stealthy, of necessity. He had thrust into two bags all the clothes that they would contain and into the other such of his personal treasures as it seemed to him he might need: books, a brace of rather ancient pistols, a hunting-knife, a set of chessmen and a board. And so here he was, for once eager to leap ashore, and the next thing to find Colonel Ceran St. Vrain and the caravan he expected to join.

Independence! the spot from which the westward-moving train was to set out. How was he to reach the place? He hung around the landing, watching the bales of goods unloaded from one bateau after another, looking for some one who might be going his way. A trapper in buckskins and beaded moccasins yelled profanely and ardently as the oarsmen battled against the current and struggled for a safe landing. Not far away stood his mules, waiting for their loads.

“Independence?” nodded the half-breed. “You ride over with me, Pierre Lafitte. Sure, you ride my white mule, Céleste.” Buy a horse at Independence. No time to stop now or they would miss the caravan, if they had not already done so. Pierre had but a small amount of cargo, and soon they were trotting through the streets of the new settlement, a little place of frame houses at the juncture of the Missouri River with the Kansas, later to be known as Kansas City. It was only about eight miles to Independence, and as the trapper pushed straight ahead they would reach it in an hour or so.

“Why do you think we might miss the caravan?” asked Steven, his heart sinking at the thought. “I thought it would not leave till May or June.” It would be a fearful disappointment, a disaster, to fail to connect with the caravan, he felt. It might be six months before another would be leaving for Santa Fe, and he would have the opportunity to cross the plains to that mysterious country of New Spain. He felt for the stiffly folded packet which he carried always beneath his vest, the missive given him by President Pedraza. The sense of importance and responsibility which it gave him was at times almost too weighty. What was this mission of national import which he had engaged himself to perform? This thought was running through his head now.

“One caravan have already leave,” said Pierre in reply to Steven’s question. “The Indian are very bad this year. Ute, Pawnee, Cree, Comanche, no like the way white men shoot back.”

Pierre’s tongue had been loosened by several pulls from a flask, and as they jogged briskly along he unburdened himself with talk of the trade, of the American Fur Company and its nefarious ways. “Bribe the Indian with weesky,” he said, “an bad weesky at that.” You never knew what you would get for your furs; lots of trappers frozen out by changed prices. Supplies so high; six dollar for an ax, five dollar for an iron kettle. Sometimes your winter’s catch lost or stolen. The Rocky Mountain Fur Company just as bad. That General Ashley of St. Louis, belonging to the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, had stolen a cache of furs up north, planted by Skeen Ogden of Hudson Bay Company, just because he himself have bad luck. In four years Ashley had grown very rich, and sold out to Smith and Sublette of St. Louis.

Pierre was depressed. After ten years’ trapping he was only $550 ahead, and he’d had to come way down from the Colorado River to collect what was due him at St. Louis. The trader who staked him with supplies had tried to cheat on him, and had sent Indians after him on the Trail to kill him before he could get down to St. Louis and get his account straightened out with the company itself. He’d gotten off with his life, but not much else. It was a hard trade. But he wanted to get away from this civilization and be back on the upper Colorado.

Having unburdened his soul, the trapper relapsed into a taciturn silence, and it was so that they completed the journey, jogging into the little town of Independence, where before the big general store and hotel they saw at once that a caravan was making ready. Steve drew a breath of relief, and the suspense which he had felt let down.

“There is Colonel St. Vrain,” and Pierre pointed out a stocky figure in the fustian suit of the townsman of the period, and a broad Mexican hat. A few minutes later Steven stood before him, a heavy-set man with wide, pleasant face.

“Colonel St. Vrain?” The colonel looked up to see a burned young man of twenty-two or three, he judged (so much had three months on the river done for him), who towered head and shoulders over himself, and took an instant liking to “Steven Mercer of New Orleans, at your service monsieur.” Busy as he was—the arrieros were loading the mules with their packs, and everywhere wagons were being charged with their cargo—the colonel stopped to listen to Steven’s request and to read the letter of introduction, upon which he again shook hands with Steven.

“But certainly, my lad, if you wish to cross the Trail with us you are welcome. And welcome you surely are, for another few hours and we should have left. We have waited here six weeks for this merchandise while William Bent, my partner, went ahead with the other caravan, escorted by Major Riley from Fort Leavenworth, and three companies of soldiers. We shall sleep on the prairies tonight, so make haste. But,” and the colonel eyed Steven keenly, “I see you bring no equipment, no merchandise?”

Steven reddened beneath his burn. “No, monsieur, my father is not yet convinced of the possibilities of trade westward to Santa Fe——”

St. Vrain nodded energetically, not displeased, perhaps, at that. “Are you driver, guide, trapper? Non! You are not. I pay you no wages, but all who are of the caravan must do what they can to make themselves useful, n’est-ce pas?”

“Oh, I shall pay my own expenses, mi coronel,” protested Steven. The hospitable but practical St. Vrain was at this moment called away to supervise a wagon-load and Steven was led off to the store by Pierre to pick out his outfit. They opened Steve’s luggage to take stock of what he had. Three flannel shirts of the kind that the river men down on the Mississippi wore, some heavy socks, that was all of a frontiersman’s outfit that his bags yielded. He closed them quickly, a bit ashamed to have the guide see the fine linen underthings, the starched shirts, an extra suit of fustian, and one of silk, also a pair of smartly turned city boots.

“I can leave these bags here,” he said, and was all for discarding them grandly.

“But, no,” cautioned Pierre. “Take them with you. If you do not wish to wear the clothes, you can sell them out there. The Mexicans will buy everything.”

Steven emerged from the store transformed, wearing Mexican leather breeches open from the knee down, plainsman’s boots, and a shirt shipped from his father’s warehouse. It had taken the whole of his month’s allowance to outfit himself—gun, ammunition, his rations of beans, salt pork, coffee, and flour, which were added to the general commissary of the colonel’s outfit. He deposited $200 in all with the storekeeper, and his remaining $300 Steven tied tightly in a leather pouch and hung it inside his shirt.

With his grips and new outfit he reported back to the colonel, was assigned a seat in the wagon following the colonel’s own, second in the caravan, and took his stand at one side while he watched the preparations for departure, hoping to be called upon to do something, ready to jump for such service.

Here were swarthy Mexicans, whom the boy from New Orleans recognized, as he had talked with many off the ships from Vera Cruz, swearing and sweating as they made ready the mule pack train which would make up half of the caravan. A mula de carga was brought up to where the cargo lay upon the ground, the sheepskin pad and saddle-cloth thrown upon its back, the aparejo, the hay-stuffed saddle of leather which protected the animal’s back from the cargo, set on top, and cinched with a wide grass bandage as tightly as the shouting, straining arriero could draw it, while the mule groaned and grunted. It seemed to Steven raw cruelty, but he kept his own counsel, watching one animal after another saddled in this way, swiftly, expertly. The cargador and his assistant, using their knees as levers, deftly heaved the heavy bales of goods up on to the mules’ backs, lashing them firmly with a stout rope passed under the belly of the animal, while a vicious-looking crupper passed beneath their scarred and lacerated tails further served to hold the whole tight. In five minutes a mule was loaded. “Adios,” shouted the cargador, slapping the animal on the rump. “Good-by.” The assistant would sing out, “Vaya [Go].” “Anda [Walk],” the cargador would answer, upon which the animal would trot off to feed until the rest of the train was ready.

There were thirty wagons in this caravan, drawn by mules, with the exception of two belonging to the colonel, which would carry three tons of goods each, twice as much as the others, and which were each drawn by twelve oxen. This was something new on the Trail and the colonel was most particular to see how the oxen served. The remaining six wagons belonging to St. Vrain carried one and a half tons each and were drawn by eight mules. The rest of the caravan was made up of eight-mule wagons and the mule train, with thirty or forty extra mules and horses that would bring up the rear of the caravan, as usual.

The colonel had been chosen captain of the traders, and his word would be law on the voyage across the plains. He rode back and forth now, directing the loading of his own wagons and superintending the work of all. Steve’s bags were packed under the seat of the wagon in which he was to ride. The caravan was falling into line before he realized it. No time to lose; the train had waited as long as it dared for the goods from New Orleans, and, now they were ready, they would go.

“All’s set,” was heard from one teamster after another.

“Stretch out,” shouted the mayordomo (who was next in command) as the muleteers ran along, cracking their whips and driving the grazing mules into line. “Catch up! Ca-aatch up!”

The driver of Steve’s wagon leaped to his seat, curled the whip over the backs of his eight mules, yelling and gee-hawing at them; there was a great shouting all down the line, an answering accolade from the populace of Independence which had all gathered in the square to watch the departure, and they were off, to the jingle of chains, the rattle of yokes, the yee-hawing of balky mules, rolling down the incline that led away westward, with a flourish and a bravery, right into the setting sun.

To Santa Fe, seven hundred and fifty miles ahead—with but one white settlement in all the distance—lumbered the caravan. There were fifteen wagons, fifty men, and more than three times that many animals. Before them stretched the undulating prairies, waving with deep grass; behind wound the tail of the caravan. Above, the skies were richly blue, gorgeous with vast white clouds.

Four nights on the plains, under the stars, listening about the camp fire to talk of trader and trapper. Steven was filled with tales of the Trail, and of the fortunes that lay already mined and minted over the far mountains—theirs for the journeying after. Seated now in the lead wagon beside St. Vrain, Steven wondered if in all that vast wilderness of land there could be other living beings than the fifty men and near two hundred animals of their caravan.

“Ha! you think not,” said the Frenchman, chatting now in French, now in English. “In this land”—he swept his hand about the horizon—“live many great nations of red men—Kaw, Kansas, Pawnee, Arapahoe, Kiowa, Comanche, Apache, Cheyenne. Many tribes, two to ten thousand strong.” It was the fur-traders, St. Vrain remarked with pride, who had taught the Indians to need white men’s goods—calico, whisky, looking-glasses, and gunpowder.

“Not so many people in Santa Fe,” said St. Vrain, “just about two thousand souls, but, mon Dieu! there were near fifty thousand in the state, all told—Mexicans and Pueblo Indians—and that was worth risking something for. The Spaniards had been shipping everything but the foodstuffs of the land up from Mexico for almost three hundred years. And they have further to come than we. What could be easier than this?”

“It is wonderful,” Steven agreed, “yet I wonder if those new steam-driven engines which they ran on a track in Maryland last winter will not be crossing this plain some day. Think, they could pull all this freight without any effort at all.”

“I doubt if ever,” St. Vrain shook his head skeptically. “They could never lay the track, and could make but little better time. We’ve come fast. We’ll be nooning at One-hundred-and-ten-mile creek. Day before yesterday I showed you where the Oregon Trail branched off; now the way lies straight ahead till we strike the Arkansas at the Bend. Your Senator Benton, and President Monroe, too, have been good friends to the traders, getting the old Trail surveyed. This is the way lad, that the first fellows who found that country yonder traveled. They followed the sunset, the Spaniards, till they struck a river flowing from the west, the Arkansas. And that’s the way the first traders, La Lande and Pursley, came twenty-five years ago; they’re still living in Santa Fe, doing business. And Captain Pike, exploring for the United States—I’ll show you a great peak named after him when we reach the mountains. But poor Pike got onto Mexican territory and built him a winter fort, thinking it was the United States, and they threw him into prison in Santa Fe as a spy. Lots of those who came after him met the same fate; and since they blazed the way many traders have come.

“I’ve heard it said out yonder”—the colonel nodded towards the sunset—“that those early Spaniards thought they were going to find cities with streets paved with gold! Seven of them!” The fat Frenchman threw back his head and laughed appreciatively. “But the gold is in the pocket, not in the street; and it’s silver, bar and bullion and minted coin.” He slapped his thigh, roaring heartily. “That is what the trader finds in honest trade where the Spaniard failed with all his bloodshed. Yet do you know, they hate us like pizen! Many a man who found his way across this trackless plain and through the mountain passes wasn’t able to find his way back. Rotted in Mexican jails like McKnight and his party back in 1812, that lay for ten years in Chihuahua carcels, their goods confiscate; mais oui!”

“How did this Pursley happen to be allowed to live in Santa Fe unmolested?” asked Steven, curiously, a trifle uneasy at such a record.

“They wouldn’t let him leave. He knows where free gold lies thick in those mountains,” the colonel replied. “He won’t tell where and they wouldn’t let him get away. They always hope to find out where. Some day he may tell and there’ll be a trail broader than this worn to the diggings, mark me.”

The colonel flecked the backs of his oxen to speed their measured pacing. “My countree she give up an empire here,” he said at length in English. “Two hundred year she been here, up and down the Mississip. England push down from the Great Lakes, from the Hudson Bay, but she can’t push the voyageur off the rivers and lacs. Those Spanish they lie safe behind those mountains, like the dog in the mange; cannot hold this land and don’t want anyone else to. The Mexican, and now the Texan South, they get as bad as the Indian every year now. Don’t want traders to pass through Texas.

“But two hundred and fifty thousand dollars’ worth of goods have been carried over this trail this year, my lad.” The colonel nodded impressively. “I talk with all the traders who buy for forts and with fur-traders as well. And that is not all. Colonel Bent tells me that seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars’ worth of trade has been taken in to Santa Fe from Mexico this year from everywhere. For this reason I myself and Charles Bent have made our move to Taos this year. Colonel Bent stays on the Arkansas. Too bad there is no river to Santa Fe. See how many trading stations and forts already on the Oklahoma.

“But come, I see you are more interested in stories of adventure. Is it not so? You shall have enough of it before you have finished.” Steven’s eyes lit with delight. “Last year a company of young men from Franklin, Missouri,” the colonel continued, “reached Santa Fe, sold their goods, and months later came staggering back to Independence on foot, almost dead. They’d been attacked almost from the moment they left Santa Fe, their mules stampeded off. They had finally to hide nearly all the money they’d made, ten thousand dollars silver—cached it on Chouteau’s island on the border.

“Will they go back for the money? I bet you que oui! Some of them are with that caravan ahead with Bent. Major Riley will guard them to the cache. Oh, you’ll have adventure aplenty my lad.”

“Tonight I stand guard for the first time”—Steven was hugely pleased—“but everything has been very quiet so far, Colonel.”

“Let us hope it will continue to be so,” replied St. Vrain, fervently, “as we have no military escort. We’re but four days out and there is a six weeks’ journey at least before us. Do you see that dark streak yonder on the horizon? That’s buffalo, a hundred herds, likely.”

To Steven the endless, treeless prairie stretching away before them held all the lure of the sea for the sailor. His eager eyes looked over its waves, anticipating what lay beyond. A natural road, surveyed five years before as far as the Mexican border. But through the mountains beyond, where there were no roads—that was where the survey was needed; where many a good man was killed from ambush in some narrow canyon.

Great clouds were massing to the south and rolling up into the sky, their fleecy whiteness shadowed by heavy, rain-filled masses. The mayordomo rode forward from the rear to consult with the colonel. They decided that, with so heavy a storm brewing, it would be well to halt and have supper over before the rain began. The cry went down along the line of the small army that stretched out for a mile in the rear, “Catch up, ca-aa-atch uu-up!”

The colonel ordered his outfit to make a halt immediately and the cook went about making a fire of caked buffalo dung, which he lit with the dried grasses of the prairie. Soon coffee was steaming in enormous pots, salt pork and beans were warming in huge iron kettles, and flapjacks were mounting on a hot iron griddle. There were many individual parties in the caravan who cooked and ate by themselves, but the colonel’s outfit had a cook. The colonel carried with him a small tent, which was not always set up, a camp table and folding chairs, so that upon occasion he could eat with comfort and style. But tonight he and Steven, the mayordomo and Pierre, squatted about the camp fire, and in the queer half-light that hung below the clouds, now rumbling and thundering ominously, they quickly dispatched their food. The colonel at once set about making his wagon shipshape for the night, and the arrieros ran about, covering their cargoes and aparejos. The mules and oxen were turned into the improvised corral of the caravan train; the wagons were driven into a circle and locked together by running the long tongues under the beds of the wagons ahead. This had scarcely been accomplished when with a great drive of wind that set loose rope and canvas a-slapping and whipping, the storm was upon them.

As he could not reach his own wagon, Steven ducked for the colonel’s tent, which was pitched just outside the circle of wagons and in a little depression against a hill. He found the colonel sitting in the center of his bed, a pipe in his mouth, a lantern already lit, and a huge limp map spread out upon his knees. It was a buffalo hide upon which was drawn in charcoal and in colored rock a plan of the Rockies and of certain passes that lay beyond. While the thunder cracked over their heads and the little tent rocked and swayed in the gale till Steven thought it must surely collapse, St. Vrain unconcernedly examined his map, shouting to Steve, “We’re takin’ a new trail over the mountains this side Santa Fe; old buffalo and mountain-sheep trail. Les animals sylvestres, wild critters, knew it was the easiest way, but no one on two legs had sense to find it out till by accident recently.”

Each word was interrupted by terrific peals of thunder, and flashes of lightning, and after a short time by a cloudburst directly over the caravan, which let loose such a deluge that the colonel’s lantern was doused, while at the same time a flood of water ran over the floor and left the bed islanded in the center. Steven wished he were in his wagon, well above the flood, but he had no thought of venturing out in the storm to reach his own bunk.

“Time to go on watch.” In the darkness the colonel set his mouth to Steve’s ear and roared. Amazed, but none the less ready, Steven struggled out through the whipping flaps of the tent and staggered blindly toward the spot where his wagon stood. He collided with St. Vrain’s mayordomo, who shouted, “Watch.” Steve’s buckskin shirt and breeches were already slimily wet, but he managed to reach inside the wagon, feel about till his hand encountered his own bundle, and drag out a heavy, stiff, Navajo blanket. He thrust his head through the slit, grabbed his gun, and stumbled toward the corral opening, to take orders.

Between peals of thunder that drowned the voice, and torrents of rain beneath which even the mules hung their heads and drooped their tails, Steve was assigned the northwest watch. He strode away to his first post, reflecting that upon a night like this no Indian would be thinking of attack. The thought reminded him of what he felt would be Indian tactics, and he crouched lower as he walked, holding his gun ready, cocked, as though charging into battle, instead of into the prairie dark.

Beyond he could see, as the lightning flashed, a small clump of bushes on the side of a little knoll not fifty feet from the caravan corral. He made toward this, planning to crouch in the lee of it, where he would not be seen in the occasional flashes of lightning. The blanket, a poncho, was already getting in its good work, for he felt warm, if wet, next his skin, and the coarse Navajo wool was practically water-proof. The tail of his beaver cap performed its office nicely, but the brim could not keep the sheets of water out of his eyes or his mouth.

As he stooped toward the bush he heard a whizzing noise from behind, ducked involuntarily, but not enough to completely escape a blow from the missile hurled at him. It nicked his ear and scalp, but he had no time to notice the pain. A form rose up out of the blackness and grappled him. His gun was wrenched away in the struggle to keep his feet and to hold fast the arms of wire that clutched below his thighs. He kicked forward mightily, a kick that caught the dark assailant amidships, and down they went together, to roll struggling to the bottom of the knoll. By which time Steve’s long arms and longer legs had done much toward increasing the distance between himself and his attacker, and when they reached the bottom he was on top, but straining in every sinew, winded, his throat almost cut off from air by fingers of steel.

It infuriated Steve. The blood of fighting ancestors of the sea rose in his brain and suffused his eyes, so that literally he saw red in the night’s blackness. Fingers gouged his eyeballs. It was agony. With a howl of rage he lifted his big-boned young body and lunged down with one hundred and seventy pounds, his knees landing in the other’s stomach. The clutching hands relaxed, the figure went limp. Steven got to his feet, stumbling backward over the fallen rifle. He recovered the weapon and faced about to charge the darkness and any other attacks it harbored. A flash of lightning showed the figure of an almost nude Indian lying before him, face turned to the sky, eyes open.

Steven felt overcome by weakness; his legs were turned to water. He struggled back toward where the wagons must be, missed them completely, had a sense of being utterly alone in a limitless space of storm and prairie. Blindly and a trifle wildly he headed in the opposite direction; then a brilliant flash showed him the wagons lying to his left. A few moments later he bumped into the captain for the night, pacing his rounds about the wagons. A sudden lull of the thunder and winds had come and the rain had lessened to a mild, steady downpour.

“Indians,” Steven gasped to the captain. He pointed toward the bush where he had taken his station. “Guess I killed him!” He sank dazedly upon a bale of cargo, his eyeballs still tortured. Half a dozen men had already spread in a cordon in some deep matted grass beyond the corral. A dozen more came running; the camp was alert. There was firing, muffled and sounding far away. Steve pulled himself together and hurried toward the sound. The mayordomo rose up out of the grass. “On guard!” he barked. “At the gate!” and without any inquiry into Steven’s condition slunk on all fours round to the other side of the wagons.

The wind stopped, and the lightning. The rain descended in a warm, steady stream. Curiously warm, thought Steven, as he wiped his dripping face. Repressing an involuntary shudder that shook him, he tried to pierce the darkness, watching this side and that, his rifle presented, nerves tense. The rain stopped. Hours passed, hours during which Steven grew rather faint, with a strange nausea at the pit of the stomach. He longed to lie down, to sleep, and fought the shameful stupor that crept over him, and was conquered, only to settle again. He would be disgraced, and the penalty unnamable, were he to sleep at his post. He had a vague feeling of remorse that he had not said good-by to his father and mother before he left New Orleans—so long ago, so far away. He must not go to sleep.

St. Vrain, the mayordomo, and some others appeared suddenly out of the gloom. St. Vrain held up a dark lantern which he had been carrying under his cloak, and in the barely perceptible light looked at Steven. “Come on into my tent. He’s relieved from guard duty.” He nodded to one of the trappers, and Steve followed him a trifle uncertainly. In the tent the colonel drew out a kit with bandages and salve, a rude equipment but skillfully handled with the deftness of long practice.

“Tomahawk cut; leetle further and he shave off your ear. Leetle further and he shave off the top of your head—Kiowa,” the colonel explained when he had finished the job. “Treacherous and fierce. Out scouting. You put fear in the spy. He run, run his horse, but we get him. Morning is nearly come now; you will go to catch some sleep.”

Steven managed to reach his bunk in the wagon just in time. Clambering over the seat, he sank with a reeling head to his couch on the bales and his senses swam off to blissful unconsciousness the moment his head touched the blanket pillow. How much time had passed when he was waked he could not imagine. The sun was shining straight in his face, but he could have slept the clock around. “Breakfast,” he could hear the cry. “We’re off in a half hour.”

He had been asleep but a few hours and ached in every muscle. Then he remembered his tussle with the Indian the night before. He dragged himself out to the camp fire, where scalding coffee and corn bread were being passed out hurriedly. The coffee was bracing, and St. Vrain’s hearty reception even more so. Steven noticed for the first time that the front of his coat and his sleeve had literally been soaked with blood, and his poncho was still damp and stained a dull red.

The arrieros were shouting to the mules, which came running and stood each beside his own equipage and cargo, waiting to be saddled, except a few unruly ones who kicked up their heels and dashed off before the pursuit of their drivers. The oxen went readily into their yokes, and in an incredibly short time the caravan was once more moving over the prairie, not so smoothly this morning, for the road was gummy and slippery with mud. It was heavy and the ruts became deep.

“There’ll be no nooning today,” St. Vrain announced as he rode by on a mule. “We’ll make Cottonwood Creek by night and go into camp there.” But an unexpected occurrence was to set even the captain’s decision aside. They had passed out of the storm-soaked area into a dry region where apparently not a drop of rain had fallen.

Almost unperceived by Steven, a vibrating trembling of the earth became apparent. It developed rapidly into a roar like distant thunder. Steven listened, surprised; there was something elemental, alarming, in the tremor. A number of hunters and trappers were riding by at a dead run.

“Buffalo! buffalo!” the shout went up. Leaping from his seat, Steven ran ahead in time to see a cloud of dust come rolling over the crest of a slope about a quarter of a mile beyond and to the right of the caravan. Out of the dark cloud a black moving mass came thunderingly forward. It was a herd of perhaps thousands of buffalo charging straight down upon them. The caravan train was thrown into a panic. The oxen pushed forward mightily, lowing in their fear. The mules went crazy, pulling out of the ruts and dashing madly away from the oncoming stampede, while the drivers yelled, lashed with their long whips, and pulled back on the reins. The driver of Steven’s wagon leaped out, thrusting the whip into Steve’s hands, and he found himself shouting at the crazed animals, lashing them on the off side while the driver tugged at their heads on the nigh side, trying to turn them from the Trail, straining to keep the wagon from overturning, while to the right the stampede came nearer and nearer. He had a momentary impulse to jump, but realized he was safer right on the wagon. He was more frightened than ever he had been in his life before.

The men who had ridden forward were trying to turn the avalanche of buffalo, but it was impossible to swerve more than a portion of the herd, and, borne on by their own momentum, a horde was sweeping down upon the pack train. It looked as though they must pass directly over the caravan. Snorting, their little eyes blood-shot, blood streaming from the nostrils of many that had been shot, they came straight towards Steve’s wagon. The mules in the path of these monarchs of the plain went wild, rearing, bucking, their heavy cargoes notwithstanding, while some of them bolted off the Trail and clear out of sight. His oxen lowing frantically, Steve managed to pull out of the road. The hunters, who had wheeled and were riding along beside the massive animals, were firing into their ranks. It seemed as though bullets must be less than grape seed against the hairy leather hides, yet one after another fell, but without affecting the charge, for the rest stampeded on over them.

The shooting of the lead bulls, however, parted the mass and the ponies galloping alongside caused a division in the ranks; while one part swerved off at right angles, a great herd passed right through and over the ranks of the caravan. Two wagons were upset and beneath the thundering hoofs of the irresistible mass many of the mules were overtaken and went down. When the buffalo had passed over the spot nothing remained to be seen of mules, cargo, atajo, saddles. They were ground into the dust.

St. Vrain was dashing up and down on his horse, trying to keep the whole caravan from utter demoralization, while the hunters bore hard on the flanks of the swerving beasts, dropping many of them, and diverting them off and across the plains, following the rest of the herd. The caravan was finally brought to a halt. It took hours to pursue and bring back the stampeded mules that had escaped and to repair the damage. When this was done and order somewhat restored, all fell to with alacrity at skinning buffalo and butchering the fresh meat. It was very welcome, as it was the first of any consequence they had had since leaving Independence.

While they were cutting out the tenderest parts, Steve helping, and learning how to wield a knife, his hands covered with grease and gore, a sound the like of which he had never before heard, and which he was never to forget, split the air. A troop of Indians mounted on pinto ponies rode over the hill, and bore down on the still disorganized caravan.

“I thought so,” said St. Vrain. “That herd was stampeded down upon us.”

The band of feathered red men now approached circuitously at a canter, their demonstrations friendly. There must have been fifty or sixty of them. Each brave held up both hands as a signal not to shoot, while they came nearer and nearer until they were able to see lying on the plain the large number of buffalo that had been killed, and to take in the extent of the caravan. Because of the rolling character of the country through which they were now passing it was impossible to tell how far the train might extend, or whether beyond the rise in the near distances a military escort might be following.