Title: King and commonwealth

A history of Charles I. and the great rebellion

Author: Bertha Meriton Gardiner

J. Surtees Phillpotts

Release date: August 12, 2025 [eBook #76676]

Language: English

Original publication: Philadelphia: Jos. H. Coates and Co, 1876

Credits: Neil Mercer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note

1. In the original printed edition of this work the chapters are not divided into subheaded sections, but each page has a header at the top. In addition, there are marginal notes (sidenotes), many embedded within lengthy paragraphs (the incidence of sidenotes varies markedly through the book). To preserve this material and in the interests of readability:

(a) While the original paragraphing has been retained, the text of page headers has been inserted into appropriate paragraph breaks, shown as centered subheadings. These entries are suppressed where multiple headings would occur within the same paragraph: in this case only the first header is shown.

(b) Marginal notes have been inserted close to their original location.

2. Footnotes (some of which are lengthy or in diagrammatic form) have been numbered and placed at the end of the chapter in which they appear.

3. Illustrations, in the form of maps and genealogical tables, are shown in appropriate paragraph breaks. A list of illustrations, not part of the original work, has been included following the Table of Contents.

4. To facilitate readability on electronic devices, the complex diagram preceding p. 1 has been split into four parts.

5. New original cover art included with the work is granted to the public domain.

KING AND COMMONWEALTH

A HISTORY

OF

CHARLES I. AND THE GREAT REBELLION

BY

B. MERITON CORDERY

AND

J. SURTEES PHILLPOTTS

HEAD MASTER OF BEDFORD SCHOOL

FORMERLY FELLOW OF NEW COLLEGE, OXFORD

PHILADELPHIA

JOS. H. COATES AND CO.

1876

[Pg v]

The aim in writing this short history has been to give within a moderate compass a lively idea of the feelings and motives at work in what was perhaps the most important epoch of our national history. With this aim it seemed best to treat the main events with all that fulness of detail, which assists the imagination in realizing the past, and to omit such minor actions as seemed not essential to the understanding of the main facts. The same rule has been followed in dealing with the military history. For this, personal visits have been made to the battle-fields, and some rough sketches of the ground have been added. No constitutional question has been touched without a preliminary attempt to put the growth and forms of the Constitution before the reader in such a manner as to encourage him to form a judgment for himself.

In a joint work it is difficult to define exactly the part taken by each writer, but my own share in the book may be described rather as that of editor than author; it has, in fact, been mainly confined to matters of style and arrangement, [Pg vi]with criticisms on events and on constitutional questions. My coadjutor, who kindly undertook the subject at my suggestion, wrote the first draft of the whole book, and is not only responsible for the accuracy of the facts, but deserves all the credit of research into original documents at the British Museum and Bodleian libraries.

While for facts our endeavour has always been to go to contemporary records, yet it is impossible that any one can write on this period without feeling more obligation to the labours of Mr. Forster than can be adequately expressed in foot-notes. Acknowledgement is also due for many suggestive ideas not only to Hallam and other writers on the time, but to Mr. Freeman for the light he has thrown on the early history of the English constitution, and to Mr. Bagehot for his vivid description of its practical working at the present time.

I cannot conclude without expressing our thanks to Mr. R. W. Taylor for some corrections in the proof, to the Rev. C. E. Moberly for revising the earlier chapters, and above all to the Bishop of Exeter, whose occasional hints have given the kind of help that can only be given by one who has not only an accurate knowledge of the facts, but a thorough grasp of the constitutional questions at issue.

J. SURTEES PHILLPOTTS.

[Pg vii]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | CONSTITUTIONAL INTRODUCTION.—GOVERNMENTS OF ELIZABETH AND JAMES I. | 1 |

| II. | CHARLES’ FIRST PARLIAMENTS.—IMPEACHMENT OF BUCKINGHAM.—PETITION OF RIGHT (1625–1629) |

29 |

| III. | ELEVEN YEARS OF ARBITRARY GOVERNMENT (1629–1640) | 51 |

| IV. | MEETING OF LONG PARLIAMENT AND TRIAL OF STRAFFORD (1640–1641) | 82 |

| V. | GRAND REMONSTRANCE.—IMPEACHMENT OF FIVE MEMBERS (1641–1642) | 99 |

| VI. | FIRST YEAR OF THE WAR.—BATTLES OF EDGEHILL AND NEWBURY (1642–1643) | 123 |

| VII. | RISE OF INDEPENDENTS.—BATTLE OF MARSTON MOOR.—SELF-DENYING ORDINANCE (1643–1645) | 148 |

| VIII. | NASEBY.—END OF WAR (1645–1646) | 179 |

| IX. | PRESBYTERIANS, INDEPENDENTS, ERASTIANS, AND THEIR THEORIES | 199 |

| X. | TRIUMPH OF THE ARMY OVER PARLIAMENT.—DEATH OF THE KING (1647–1649) | 212 |

| XI. | SOCIAL STATE OF ENGLAND | 248 |

| XII.[Pg viii] | TRIUMPHS OF THE COMMONWEALTH BY LAND AND SEA (1649–1652) | 277 |

| XIII. | FALL OF REPUBLICANS, AND BAREBONE’S PARLIAMENT (1651–1653) | 303 |

| XIV. | THE FIRST THREE YEARS OF THE PROTECTORATE (1654–1656) | 328 |

| XV. | THE LAST TWO YEARS OF THE PROTECTORATE (1656–1658) | 347 |

| XVI. | RICHARD CROMWELL.—ANARCHY.—THE RESTORATION (1658–1660) | 367 |

| APPENDIX | 386 | |

| INDEX | 394 |

| PAGE | ||

| Governmental structure | x | |

| Genealogy, monarchs of England and Scotland | Chapter I., Footnote 9 | |

| Genealogy, monarchs of Europe | Chapter I., Footnote 14 | |

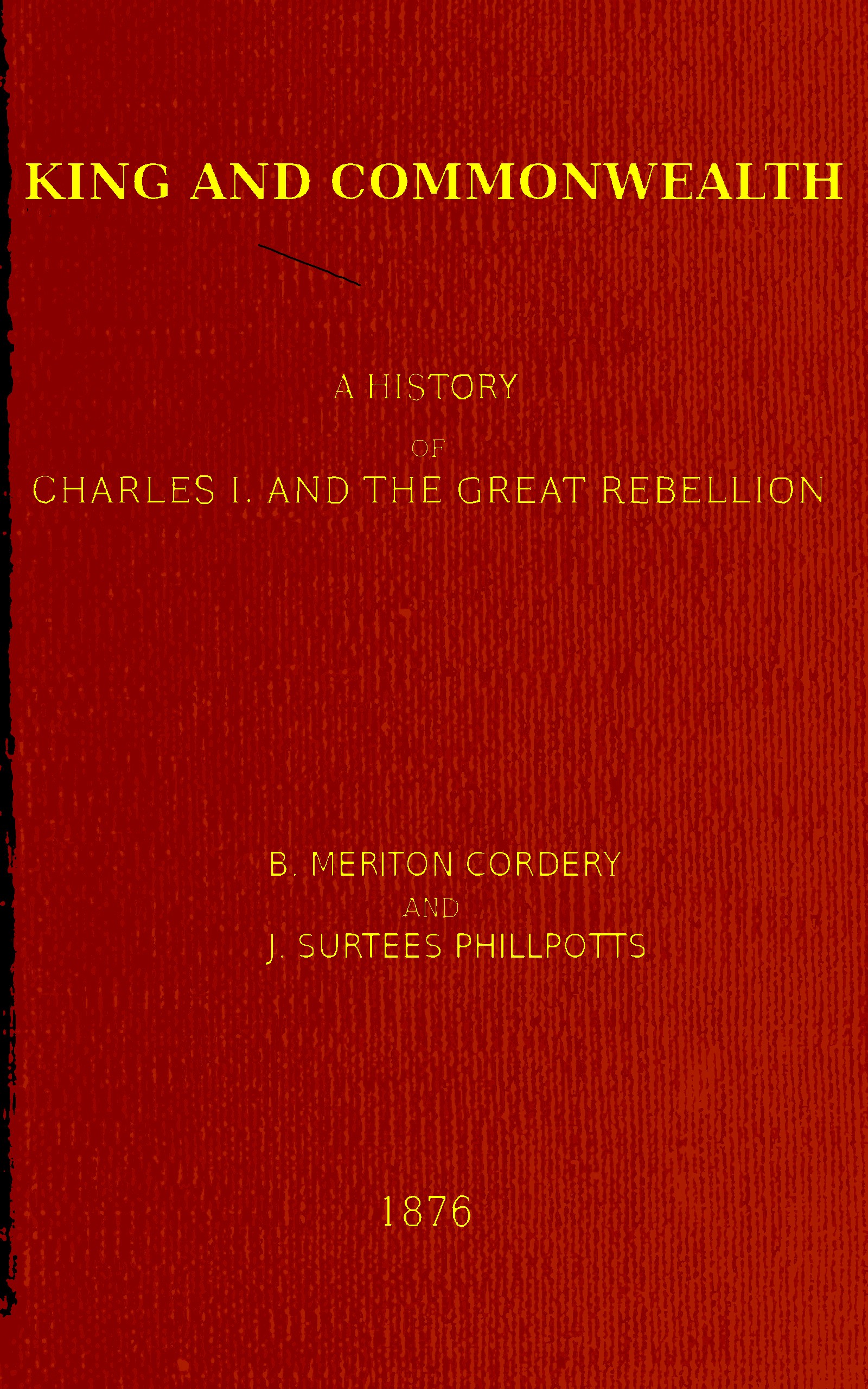

| Map of Rochelle area | 46 | |

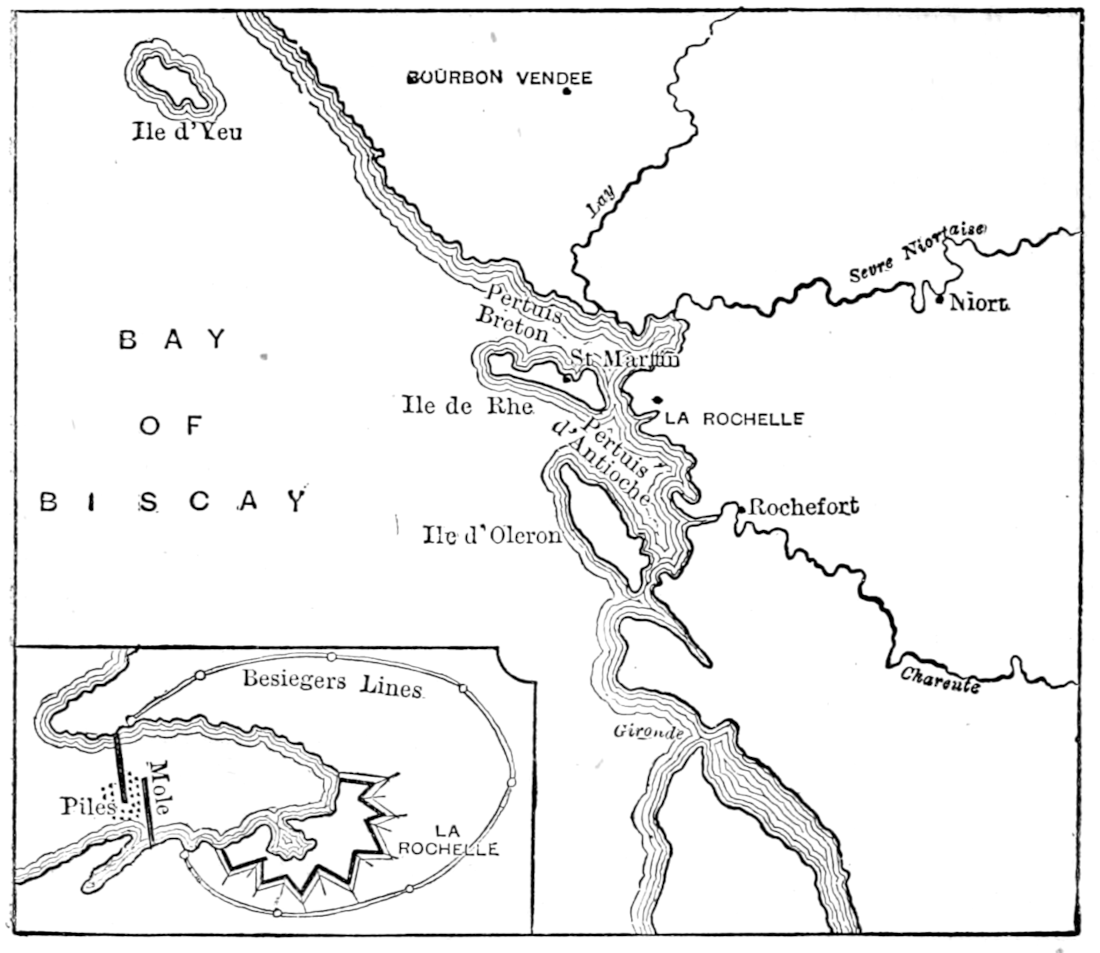

| Battle of Edgehill, 23rd Oct. 1642 | 126 | |

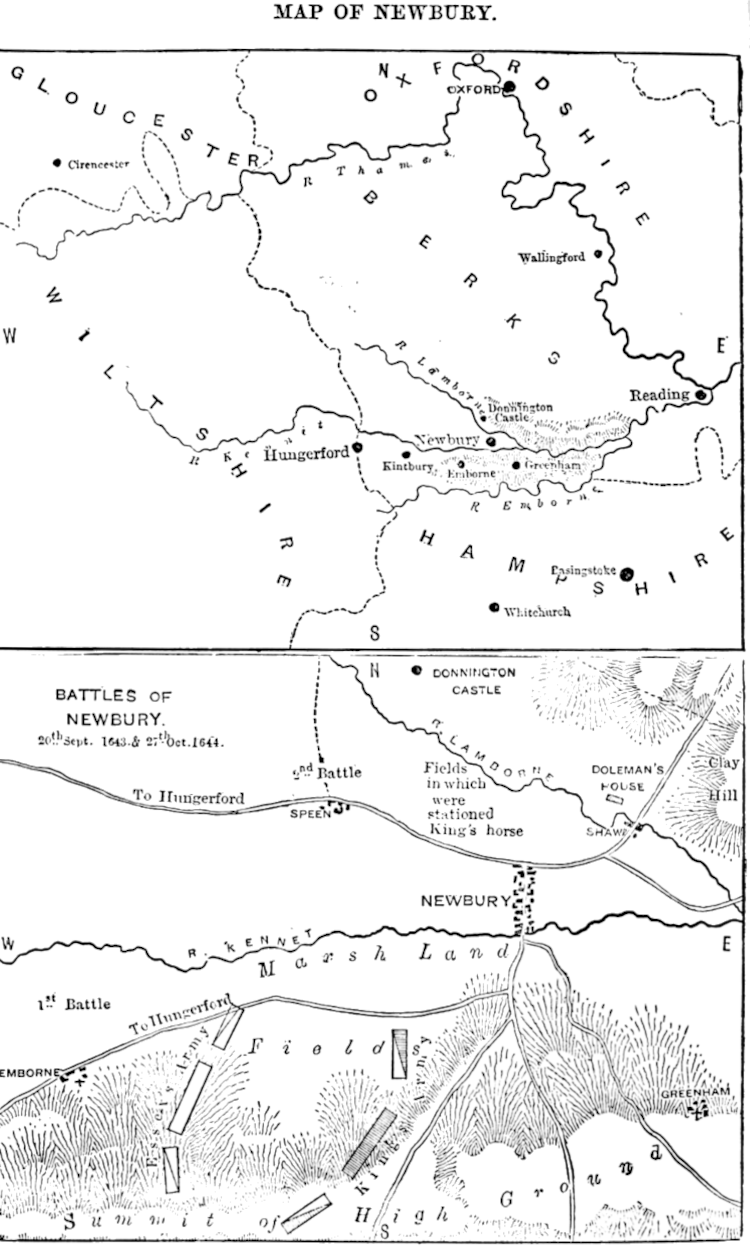

| Battles of Newbury, 20th Sept. 1643 & 27th Oct. 1644 | 145 | |

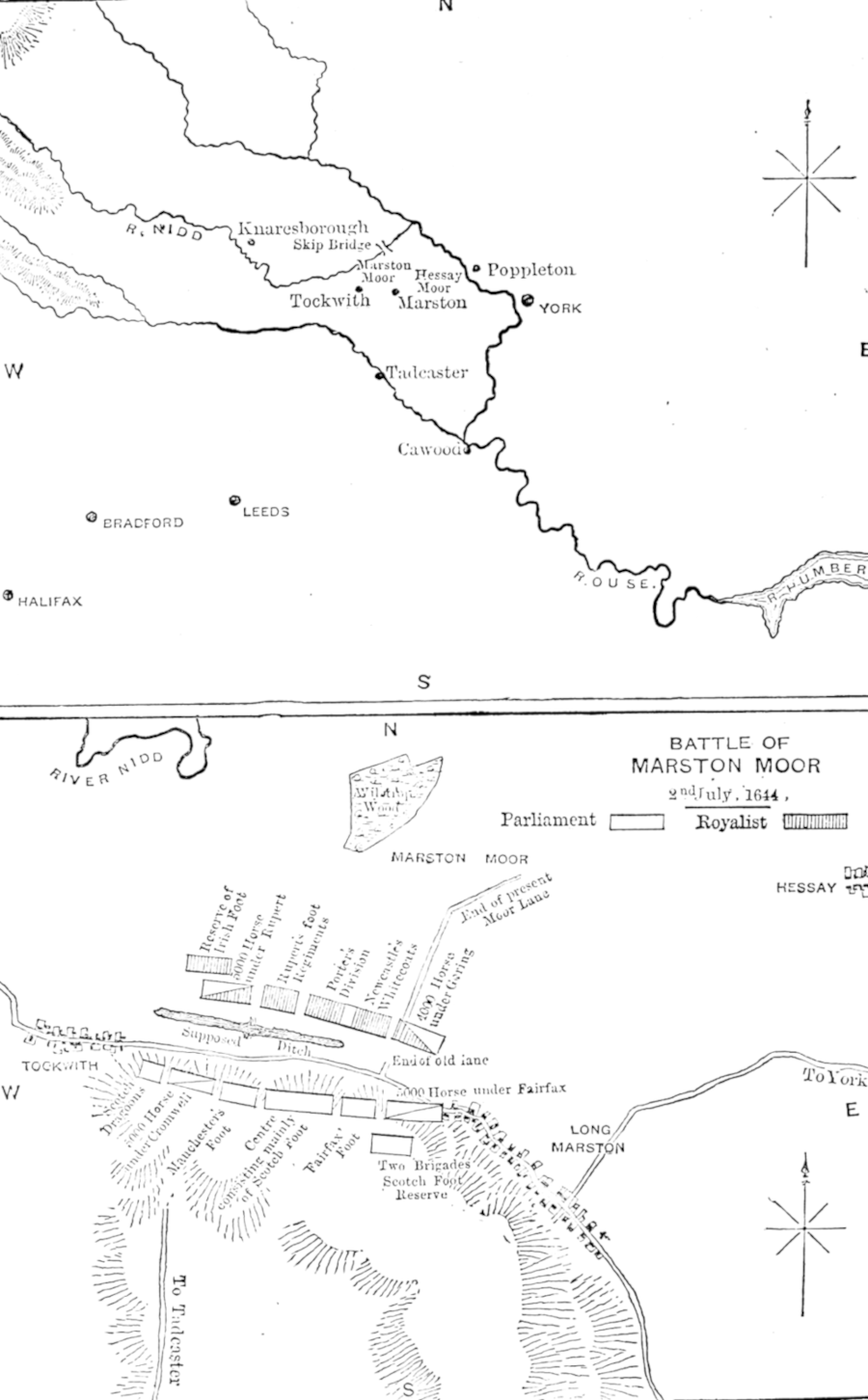

| Battle of Marston Moor, 2nd July 1644 | 164 | |

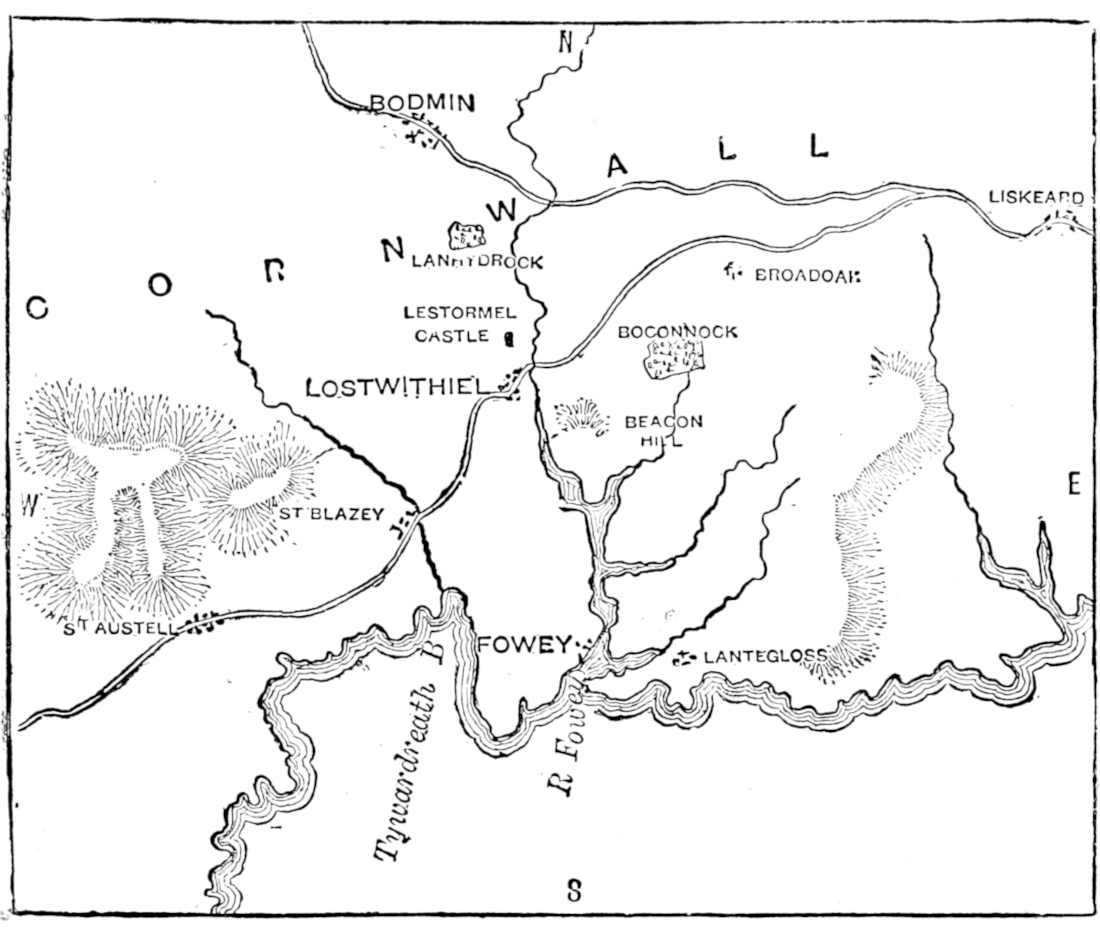

| Map of Lostwithiel area | 169 | |

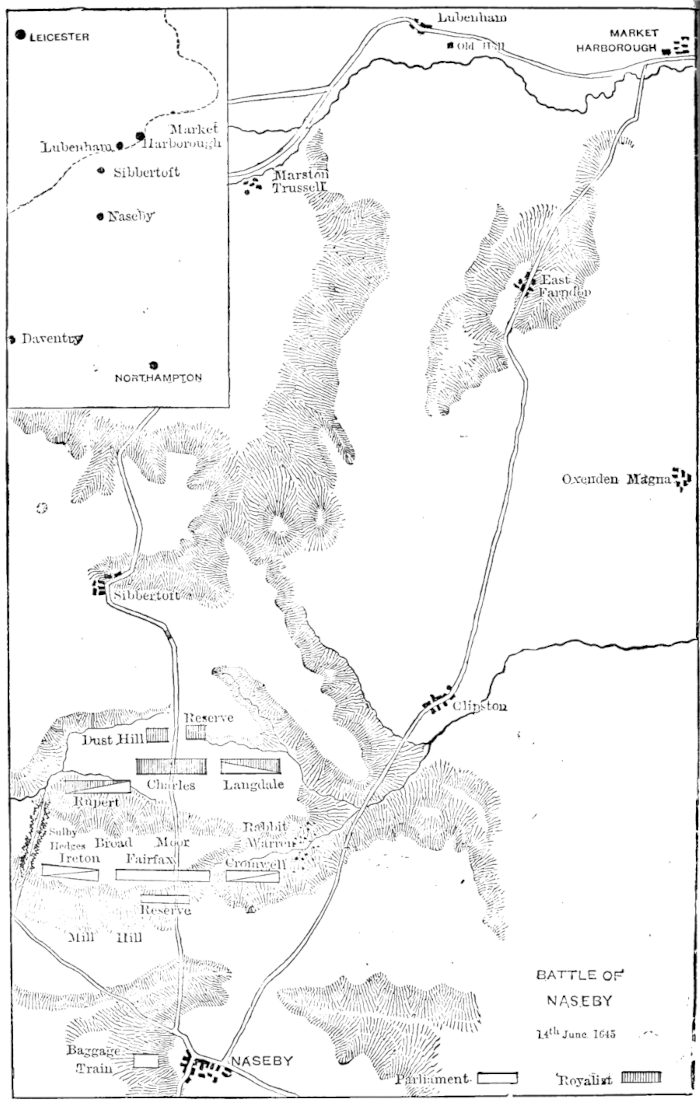

| Battle of Naseby, 14th June 1645 | 185 | |

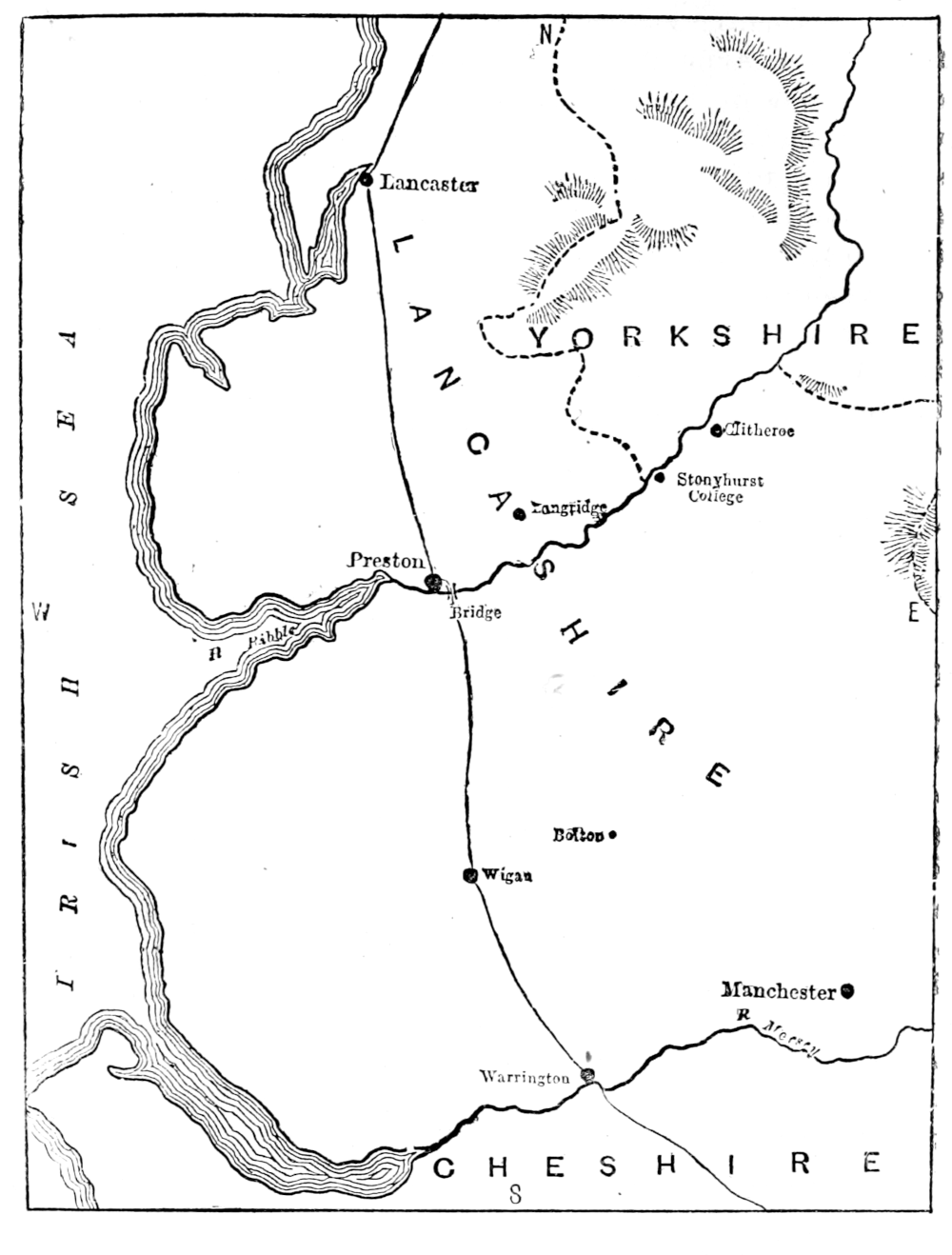

| Map of Lancashire | 229 | |

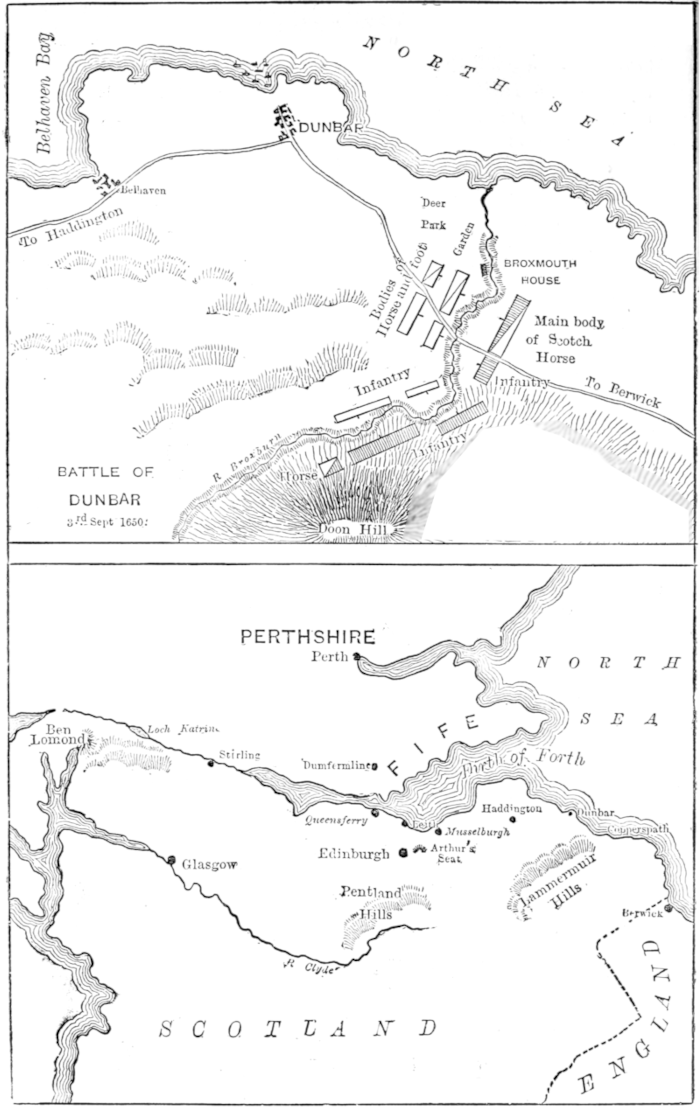

| Battle of Dunbar, 3rd Sept. 1650 | 289 | |

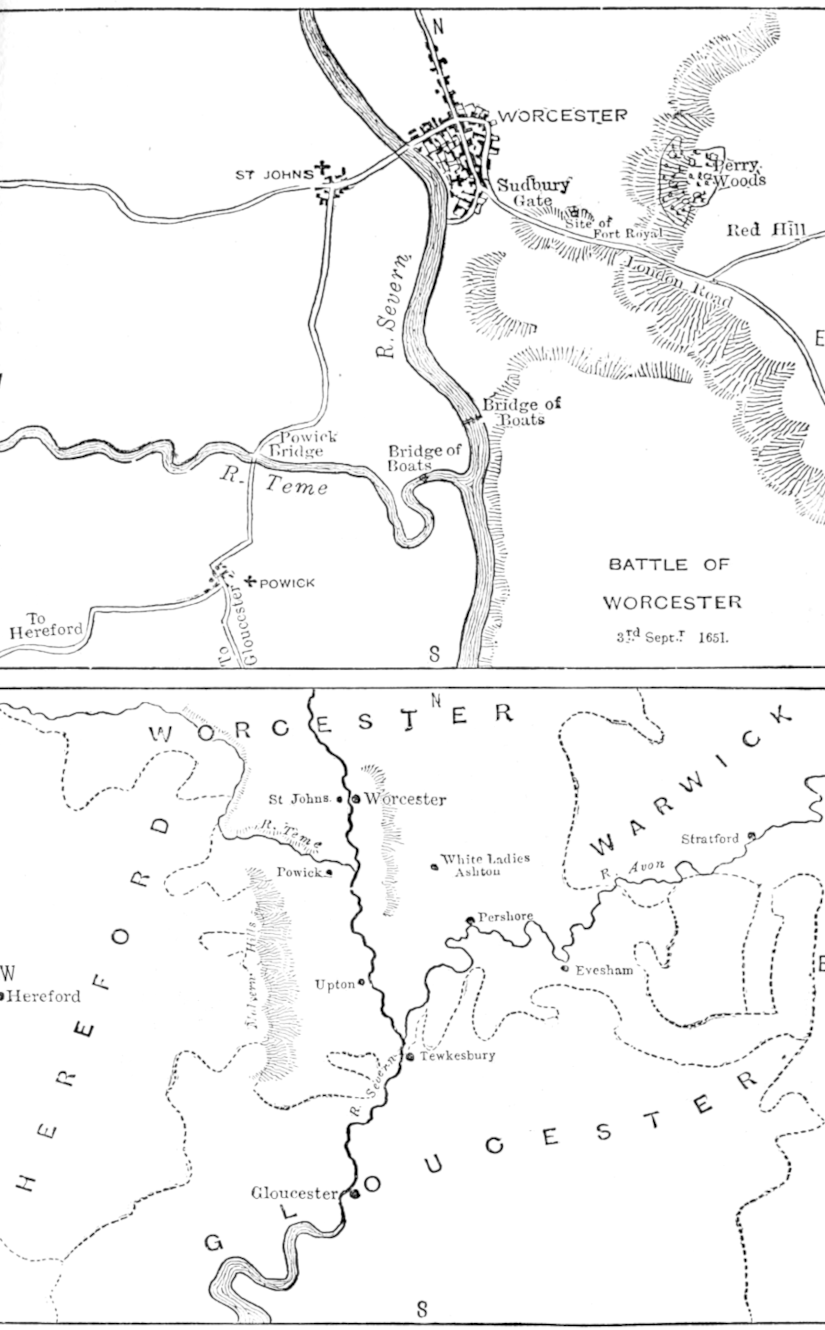

| Battle of Worcester, 3rd Sept. 1651 | 294 |

Notes

(A) Judges appointed and removed by king, but by their oaths bound to give judgment according to the laws, and to do equal law and execution of right, without having regard to any person

(B) Councillors appointed and removed by king; use of torture

(C) Judges, councillors, and others appointed by king

(D) President appointed by king

KING AND COMMONWEALTH.

CONSTITUTIONAL INTRODUCTION.—GOVERNMENTS OF ELIZABETH AND JAMES I.

No people ever was and remained free, but because it was determined to be so; because neither its rulers nor any other party in the nation could compel it to be otherwise. If a people—especially one whose freedom has not yet become prescriptive—does not value it sufficiently to fight for it and maintain it against any force which can be mustered within the country, it is only a question in how few years or months that people will be enslaved.—Mill, Dissertations and Discussions.

Three functions of government,

I. Legislative, II. Executive, III. Judicial.

A people, to be free, must take part in, or possess

control over, the three powers of government, Legislative,

Executive, Judicial. As to the first, if they are

to be masters of their persons and properties, neither

laws must be made nor taxes imposed without their

consent; secondly, ministers of the executive, whether councillors

of state, tax-collectors, military or police officers, must be personally

responsible to the law courts, or they may infringe with

impunity the laws the people have secured; lastly, though persons

and properties be protected by laws, and though ministers

be liable to prosecution, this protection is nominal only, unless

the judges who interpret the laws, are sufficiently independent of

the executive.

I. Legislative. Liberties of Englishmen in 16th and 17th centuries. I. Englishmen of the seventeenth century shared in the legislative power with the sovereign, who could make no laws without consent of the two Houses of Parliament. Their properties were protected from arbitrary seizure, their persons from arbitrary imprisonment, by two statutes, the Magna Charta, first granted by King John, and the Confirmatio Chartarum, first granted by Edward I. [p. 2]These together provide, first, that no person shall be put in prison without legal warrant, or kept there without being brought to trial according to the laws of the land; that is, that the question of law shall be decided by the established judge of the law; secondly, that the question of fact, whether a man accused at the suit of the crown, has, or has not, committed the crime laid to his charge, shall be decided by a jury of twelve of his countrymen; and lastly, that no taxes of any sort shall be imposed without consent of Parliament.

Classes represented in Parliament. Several classes of the nation shared indirectly in the government by being represented in Parliament. In the Upper House sat the temporal and spiritual lords of the realm in their own right. To the Lower House all the fifty-two counties of England and Wales, with the exception of Durham, returned two members each, elected by freeholders possessed of lands or tenements to the annual value of 40s.[1] Freeholders including feudal tenants and yeomen. The term freeholder included two classes, holders of land by knight’s service, and holders of land by free socage.[2] The first class was composed of feudal tenants, gentlemen by birth, who had originally held land in return for military service, and whose tenure was still subject to several irksome burdens. The second class was composed of yeomen, men of ignoble blood, but with a tenure dating from feudal times. The Normans of the conquest would have thought it beneath them to hold land by any other than a military tenure. But in many cases they permitted the despised Saxons to remain in possession of their lands, sometimes on condition of performing agricultural services which soon took the form of a fixed annual rent; sometimes on condition merely of taking an oath of fealty and paying occasional fines. Thus in England there sprang up in quite early times an independent class who were owners of the soil, and though not of gentle birth, sat on juries, voted at county elections, and attended the courts in which freeholders met together to transact the business of their county.

[p. 3]Burgesses. Besides county representatives, the House of Commons contained over four hundred members, returned according to usage by certain privileged towns. These were the classes possessed of political rights. Below these were the whole mass of the unenfranchised—hired labourers, tenants at will, and copyholders.[3]Copyholders and hired labourers unrepresented. These were the descendants of those Saxons whom the Normans had reduced to a state of serfdom; and, unlike freeholders, were incapable either of sitting on juries or voting at elections. For the last hundred years, however, they had nearly all been free, and were protected in person and property by the same laws as freeholders.

All classes being thus possessed of the same liberties, their common freedom gave them common interests, and caused them to unite in spite of social distinctions, and oppose the establishment of arbitrary government.

No privileged class.

In France the political condition of the people was inferior to that of the English, and this mainly from want of union and fellow-feeling between the different ranks into which French society was divided. There was no class answering to the English yeomanry; the feudal tenants were a noble and privileged class, and were divided by this barrier of privilege from their unfortunate inferiors in rank, on whom the main burden of direct taxation fell; as the inequalities of taxation increased, the different classes became more and more isolated, and thus the kings, never meeting with combined resistance from the whole body of their subjects, came by degrees to usurp absolute power, to impose taxes at will, and to govern without the aid of any national assembly.

II. Executive Power now exercised by a committee of the legislature. II. A people are little benefited by the possession of good laws, unless those laws are respected and obeyed by those who are entrusted with the execution of them. The executive power was then, as now, exercised by ministers of the crown. But in the course of two centuries the position of these ministers has been totally changed. The queen’s ministers are now in such close harmony with the Parliament, that they have been defined as a committee of the [p. 4]legislature.[4] Chosen out of the predominant party in Parliament, they conduct the government only so long as they can command a majority of votes in the Lower House. If their measures are outvoted, they have no choice but to resign office, or by obtaining a dissolution, to appeal to a new Parliament for renewal of the support which is their only claim to power.

Executive in 16th century exercised by the crown. In the sixteenth century, on the contrary, the executive power lay entirely in the hands of the king, who settled all questions of administration, made peace and war, appointed and dismissed officers of state, and expended the revenue, uncontrolled by the representatives of the people. Yet, great as was the power thus exercised by the crown, two safeguards were provided against its abuse.Two safeguards. (1) No army in England. The first was negative, the absence of a standing army in England. In France absolute power was upheld by an army, recruited in part by foreigners, and officered solely by nobles; this army the king found no difficulty in maintaining, as he imposed taxes at pleasure. No such right, however, belonged to English monarchs, who were without the funds necessary for the support of a standing army; and it was only by means of a standing army, possessed with an ‘esprit de corps’ of its own, and divided in interest from the people, that arbitrary government could be permanently established. The House of Commons always originated money bills; they held, therefore, the purse-strings of the nation, and were careful only to grant supplies sufficient for the ordinary purposes of government.

[p. 5] (2) Responsibility of king’s ministers.The principles of the constitution contained a second and positive safeguard against the abuse of the regal power. Great lawyers had long since declared that the king, his subjects, was bound to respect the laws. “The king,” Bracton wrote as early as the thirteenth century, “also hath a superior, namely God, and also the law, by which he was made a king.” It was not likely, however, that the subject would have either the power or the desire to arraign sovereigns themselves before courts of law. A fiction of the lawyers intervened and gave a better means of securing the same end. This fiction was that the “king could do no wrong.” From this it followed that if wrong was done, the ministers, and not the king, must have advised and executed the wrong; ministers could not screen themselves behind the king’s name; if they broke the laws in the performance of their functions, though it was at the king’s bidding, they were still liable to be sued by the injured parties in a court of justice.

Liberties not secure. (1) Illegal powers exercised by crown. Still these safeguards had not been found sufficient to prevent the executive from violating the law. In the first place, several powers, sometimes simply oppressive, sometimes actually illegal, were regarded as belonging to the crown in right of the royal prerogative. By these both the subject’s property and liberty were endangered. Thus the king, though he dared not tax without consent of Parliament, used to borrow large sums under the name of loans, which were seldom repaid. Both the king and his council imprisoned without showing legal cause. Proclamations were made by the King in Council, which, though regarded as temporary measures only, were in matter of fact laws, and sometimes had penalties attached to them for disobedience. So again, though the use of torture was not lawful by the common law, and contrary to several statutes, State prisoners were constantly put to the rack on the strength of warrants signed by the king.

In the second place, though the law allowed the subject to seek redress, the redress was rarely attainable. Few dared to incur the king’s displeasure by attacking the conduct of his servants, and if they did, juries were often intimidated,[5] judges were often corrupt.(2) Judges dependent upon crown. The strength of the chain is the [p. 6]strength of its weakest point. The weak point of the English constitution lay in the dependence of the judges upon the crown; unless the interpreters of the laws were independent, no law could ever effectually secure the liberties of the people.

(3) Arbitrary courts. And in the third place, besides the common law courts, other courts of justice existed, in which the accused was neither tried by jury nor sentenced according to known laws.

III. Judicial. Omitting the Court of Chancery, which had no jurisdiction in political cases, there were then, as now, three chief courts of justice, the King’s Bench, the Common Pleas, and the Exchequer, all of which sat at Westminster; four or five judges belonged to each, who in all cases were bound to give judgment, not according to their own pleasure, or the will of the king, but according to the law of the realm, whether statute or common law.[6]

Since the Act of Settlement in 1702 the common law judges hold office for life, receive salaries fixed by law, and can only be dismissed from office if convicted of some offence, or in consequence of an address of the two Houses of Parliament. But in the seventeenth century they only held office at the pleasure of the king, and being dependent in part upon his bounty for their salaries, were regarded as the servants of the court.[7]

But these courts at any rate acknowledged the known laws, and tried prisoners by jury. Of a very different character was the Court of Star Chamber, so called because its sittings were held in a room leading out of Westminster Hall, of which the walls were decorated with stars. The germ of this court lay in a jurisdiction exercised from the time of Edward III. by the king’s Common Council, which was accustomed to call to account offenders too powerful to be brought to submit to the ordinary courts of law. Then came a second stage. An Act of Parliament was passed in the reign of Henry VII. (1491), forming a court of justice, composed of certain members of the [p. 7]council, and entrusted with powers of judging cases of riots, the bribing of juries, and other specified offences. This second stage gave a parliamentary sanction to the court, but limited its powers and specified its persons. It was out of this chrysalis that the Court of Star Chamber emerged. By the end of Henry the Eighth’s reign, it had reached its third, or final stage, in which it boasted parliamentary sanction, at the same time that it repudiated the conditions under which that sanction had been given. The limits of persons and of offences had both disappeared. The powers formerly vested only in the members of the court of Henry VII. had silently passed into the hands of the whole body of the Common Council,[8] while its jurisdiction had been extended beyond the offences specified by the statute to cases of breach of trust, fraud, and libel.

Besides the Court of Star Chamber, there was a second court, the Court of High Commission, which deprived the subject of the protection granted him by the common law, and of trial by jury. After Henry VIII. quarrelled with Pope Clement VII. about a divorce from Catherine of Arragon, Parliament passed an Act of Supremacy, declaring the king the supreme head of the Church. This was re-enacted when Elizabeth came to the throne (1558), and an addition made to it, granting the queen power to appoint persons to exercise jurisdiction in ecclesiastical affairs, as, for instance, in the reformation of heresies and abuses. Elizabeth, therefore, was acting within her powers when, in 1583, she erected a permanent commission, consisting of twelve bishops, privy councillors, and others; but she undoubtedly was straining her power when she gave this court an authority—not granted her by the statute—to try suspected persons by juries, or by any other means they could devise, and to punish by fine and imprisonment. Thus, while the Court of Star Chamber, by judging cases of libel, deprived the subject of liberty of speech, the Court of High Commission deprived him of liberty of conscience. Both alike, therefore, soon came to be hated by the people; both were distinctly contrary to Magna Charta, for in neither was the accused tried by jury or by the laws of the land; both were contrary to the first axioms of justice, [p. 8]the separation of accuser and judge, for in these courts the ministers of the crown first prosecuted a man in their capacity of councillors, and then themselves passed sentence upon him as judges.

Queen Elizabeth was not disposed to yield up any powers, legal or illegal, that had been exercised by her predecessors on the throne.Caution with which Elizabeth exercised her power. She, however, was careful not to strain them beyond what the temper of the nation would bear. Though she often violated the rights of individuals, she never attacked those of large numbers at once, and always kept on good terms with her parliaments, by making concessions at times when a refusal would have caused ill-feeling. But notwithstanding the tact with which her government was conducted, as the people increased in knowledge and wealth, they grew more and more sensitive to infringements of their rights, and gave signs that through their representative, the House of Commons, they would soon call upon the crown to resign the powers it had usurped to the great detriment of the subject’s liberty.

That the legislature should make laws, and the executive break them, was a sufficient cause in itself to produce a rupture between the two powers. The probability, however, of such a rupture was greatly increased by the fact that a second cause of quarrel existed between the crown and the Parliament—religious differences.The Reformation directed by the English kings. In England, the Reformation had been, no doubt, a popular movement, as it had been abroad; but it was controlled and directed by a monarchy which had but a partial sympathy with its aims. The consequence was an exceeding moderation. The king was made head of the Church in place of the pope; the monasteries were dissolved; the clergy were allowed to marry; the doctrine of purgatory was denied, as was that of a physical change in the elements at the sacrament; images and crosses were removed from churches; the people were allowed to read the Bible in their own tongue; an English liturgy was composed; and the English sovereigns, heads of the Church, said, as it were, to the people, ‘Thus far shall ye go, and no farther.’ But no sooner had the princes finished their work, than a new set of reformers arose, preaching another, fuller, more popular reformation.

Popular reformers attack popish ceremonies. The main principle of the reformers was to get rid of those [p. 9]superstitious observances which marred the freedom of the worshipper’s communicating with his Maker; they did not believe in the necessity of priestly intervention, nor in the special sanctity of prayers in a foreign tongue. On the continent, this principle had been carried much further than in England; and when exiles, who had fled the country during the persecutions of Mary’s reign, returned home from Flanders, Strasburg, or Geneva, they regarded the English Church as hardly deserving the name of reformed. ‘How many signs of Romish superstition,’ they said, ‘are left in the prayer-book, and the services! What abuses yet remain in administration! Look at the plurality of benefices. How can one man be in a dozen places at a time? Are the clergy still to flaunt the priestly surplice and gaudy popish vestments, foolish and abominable apparel, in which the Catholic priests pretend to make mere water holy, to achieve a miraculous transformation of bread and wine, or to conjure the devil out of persons and places possessed? Is the communion-table not to stand, table-like, in the body of the church, but to be set up in the chancel like the altar of the papists? Shall the sign of the cross in baptism, the bowing at the name of Jesus, the ring in marriage, the keeping of saints’ days, all these remains of popish superstitions, be observed in a church that calls itself reformed! Surely the snake is only scotched, not killed.’

Elizabeth, on the contrary, while she regarded the authority of her bishops as a support to the power of the crown, also hoped, by disallowing further change in church ceremonies, to conciliate Catholics. Her ecclesiastical power was absolute.No toleration allowed by Elizabeth. She, therefore, refused to give the Puritans satisfaction even in matters of form. If the Puritan minister would officiate at the services of the Church, he must wear vestments he abhorred; if he would baptize a child, he must make the sign of the cross; if he would join two people in marriage, he must use the ring; in all points, he must conform exactly to the minutiæ of the rubric.

Act of Supremacy. The Act of Supremacy was a double-edged sword, cruel to Puritans and Catholics alike. All clergymen holding benefices, all laymen holding office in the State, who refused to take an oath, when tendered, recognizing the queen as head of the Church, were to be deprived of their benefices or [p. 10]offices (1558).Act of Uniformity. The Act of Uniformity forbade ministers, beneficed or not, to use any other than the established liturgy; for the first offence, they forfeited all their goods and chattels; for the second, they suffered a year’s imprisonment; for the third, imprisonment for life; while fines were imposed upon laymen who stayed away from their parish church on Sundays or holidays (1559).

But persecution, instead of suppressing the reformers, only increased their numbers and animosity. From attacking ceremonies, they went on to attack the authority of the bishops.Reformers desire establishment of Presbyterian Church. If the Holy Scriptures, they said, contain all things necessary for salvation, then where in them is to be found mention of that proud hierarchy of archbishops, bishops, and priests, by which the English Church is governed? Turning their eyes towards Scotland, they there saw established a church on a Presbyterian model, governed by assemblies of ministers and lay elders on less hierarchical principles than the Episcopal. For this model they claimed the authority of a Divine Right, as being the original form of church government established by the will of God in the time of the apostles.

To the queen, this new programme of reform, attacking, as it did, not only episcopal authority, but her own prerogative as head of the Church, was still more distasteful than that which had required merely a reform of ceremonies.

An established church may be either self-governed or governed by the State.Episcopal Church dependent upon the State. The Episcopal Church was a State church in the fullest sense of the term; archbishops and bishops, like ministers of state, were appointed by the sovereign; no laws to regulate the conduct of the laity in spiritual matters could emanate from any source but the queen in Parliament; and, in fact, there was no spiritual authority distinct from the State.Presbyterian Church independent of State control. On the other hand, the Presbyterian Church prided itself on being self-governed. According to this system, every parish had its minister, its deacon, and its lay elder, together forming a little court of justice, or kirk session, which called parishioners to account for spiritual and moral offences, such as drunkenness, scolding, or Sabbath-breaking; and punished by censures, fines, or imprisonment. So many parishes formed a presbytery; so [p. 11]many presbyteries formed a province, and both presbytery and province possessed a distinct judicial assembly, composed of lay elders and ministers. Lastly, there was a general assembly of the church, composed of all the ministers of parishes, together with a sprinkling of lay elders, and to this body appeals were made from the judicial decisions of the lesser assemblies. The orders and regulations made by the general assembly of the church were binding upon the whole nation, clergy and laity. This church had been established in Scotland by rebellion, and its ministers did not hesitate to set up their own authority in opposition to that of king and State. “Disregard not our threatening,” they said to James VI., “for there was never yet one in this realm, in the place where your grace is, who prospered after the ministers began to threaten him.”

Episcopal Church less tyrannical than the Presbyterian. Of these two systems, the Episcopal form of church government, though less popular, was also less tyrannical than the Presbyterian. The powers of English bishops were far more limited than those of Scottish assemblies. The Church of Scotland, however, which gave power to the ministers of the people, instead of to courtly prelates, suited the enthusiasm of the age, and naturally recommended itself to the more earnest reformers on this side the border.Bishops support the power of the crown. Rejoiced to find that Elizabeth regarded the Presbyterians as rebellious fanatics, the bishops on their side now set up a counter claim of Divine Right in favour of the Episcopal Church as administered by the queen; and, in return for the privilege of fining, imprisoning, and ejecting nonconformists, taught the people that kings rule by Divine Right, as the viceregents of God upon earth, and that opposition to the commands of princes is disobedience to the commands of God.

Puritans cannot be suppressed. But Puritan ministers, though deprived of their livings, could not be silenced. They thought the whole state of society and religion in England needed to be penetrated with a new spirit. Themselves eager readers of their Bibles, zealous preachers, active reformers, filled with true missionary zeal, they found that the court and nobility cared little for serious matters, and that noblemen and gentlemen spent their time in gaming, in dancing, in attending grand shows, or in fighting on the continent. They aimed at a social as well as a religious [p. 12]reform. Printing had largely increased the numbers of readers and writers, and had at the same time extended the range not only of serious but also of profane literature. It was an age of poets. There were two hundred living in the last part of the century, Spenser and Shakespeare amongst them. The middle classes followed the same kind of amusements as their superiors, frequenting the bear-garden, the bowling-green, the gaming-house, and the theatre. The country people had their wakes and fairs and festivals. Amidst so much rioting and pleasuring the Puritans saw few ministers competent to lead the people to more serious paths. The clergy, so far from checking the freedom of society, were as eager in the pursuit of amusement as their parishioners: before the Reformation their incapacity had been the reproach of the Catholic Church; it was now equally the reproach of the newly established Church. Many Catholics, rather than lose their livings, had taken the oaths required of them—were they reformed? While they passed their time in taverns, gaming and drinking, they were not likely to acquire the new art of preaching. “Dumb dogs,” said the Puritans, are “left to guard the Church, while we are turned out.” In many villages no sermon was heard “from year’s end to year’s end.” Such a church seemed to invite reform; and the Presbyterians were ready for the task. Persecution not going far enough to extirpate the reformers, only attracted the minds of others to the consideration of the questions in dispute, and discussion led to more advanced views on reform. Episcopacy was generally the religion of the upper classes.Sectarians. Presbyterian opinions prevailed amongst the middle ranks; and now the very poorest of the nation began also to have their special ideas on religious questions. Men, women, and children, poor people who had nothing to support them but their handicrafts and trades, would in summer-time meet in the fields outside London at five o’clock in the morning, and in winter in private houses, in order to worship after their own fashion. Every congregation, they maintained, however small, ought to be left free to settle its own affairs, without interference from either bishops or assemblies. Amongst these latest reformers were several distinct sects, which, without holding the same doctrines, agreed in their general view of church government; and being taught by weakness to combine together in spite of minor differences of opinion, were the [p. 13]first to raise the flag of ‘liberty of conscience.’ More cruelly used than Presbyterians, many of these sectarians fled the country for Holland, where they established churches on their own principles. Those who stayed in England ran the risk of imprisonment for life.

Elizabeth supports Protestant cause on continent. In spite, however, of persecution, the reformers were devotedly loyal to the queen. For though, through political motives, she persecuted Puritans at home, abroad she supported the Protestants in the fierce conflict they were waging with Catholicism. On one side were arrayed the pope, the King of Spain, the Emperor of Austria, the Catholic princes of Germany; on the other, Sweden, Denmark, Holland, and the Protestant German princes; and it was chiefly owing to the support of England that this side was able to maintain its ground against the Catholics.

The popes had long desired to force back into their fold the country that was thus recognized as the head of Protestant States. Pius V. had said he wished he could shed his blood in an expedition against England; and now Gregory XIII. urged on Philip II. of Spain to attempt the conquest of the heretic kingdom. He could not have found a prince or nation more suited for his purpose. The Spaniards and English hated one another with a national as well as a religious hatred. A love of enterprise and discovery had spread rapidly amongst all classes during Elizabeth’s long reign. Adventurers, led often by noblemen and gentlemen, sailed to America and the West Indies, making fruitless efforts to discover gold mines, or to found colonies.Enmity between Spain and England. On these expeditions they burnt the settlements and seized the treasure ships of the Spaniards, who, being already possessed of Mexico, Peru, and much of the West Indies, regarded themselves as sole lords of the New World, and were quite prepared for a war to the knife with the intruders.

It was thus to fight the battle at once of the pope and of the nation that the Invincible Armada sailed from Spain. It sailed to take vengeance on a heretic queen, who, while supporting the Dutch in rebellion, disputed the claims of Philip to the possession of two continents. It came threatening England with conquest and Protestantism with destruction. But storms and winds and the courage of English seamen shattered and destroyed the Armada (1588). The triumph of England was the salvation of [p. 14]the Protestant cause. The invaded now becoming the invaders, burned Spanish galleons in the very harbours of Spain.

Her foreign policy a chief cause of Elizabeth’s popularity. With the people success will go far to justify even a tyrannical government. Hence it was that, although storms were rising, and the political atmosphere was charged with electricity, no violent contention ever arose between Elizabeth and her subjects. The occasional illegal acts committed by her government, the cruel sentences passed upon Puritans by the courts of High Commission and Star Chamber, were forgiven because she pursued a foreign policy that accorded with the wishes of the nation, and caused England to be feared and respected. The bonds of loyalty seemed strong because they had not been tried too severely, It is a principle in mechanics that girders should not be strained beyond the limits of perfect recovery. An excessive tension may not only cause danger for the moment, but may be a source of permanent weakness, Such a tension came when the nation was ruled by monarchs who had neither the capacity to lead their Parliaments nor the temper to follow them.

On the death of Elizabeth the great Tudor line was extinct.[9]James I., his character. James VI. of Scotland, who outwardly united the two kingdoms, failed to unite his subjects to himself. He was thought cowardly, conceited, pretentious. It was believed that flattery was the readiest road to his favour; he certainly suffered himself to fall under the control of unworthy favourites, so that his court received the character of being the head-quarters of riot and vice, if not of far darker crimes.

[p. 15]

The members of the Commons refused to grant the money of the nation to be lavished on such favourites or wasted in such riot. James, therefore, did not trouble himself with often meeting the representatives of the people. Holding the theory that he was possessed of absolute power, he ventured to try to carry that theory into practice. A few instances will show the manner in which the liberties of the subject were violated by his government.

His first Parliament granted him for life duties on exports and imports, called tonnage and poundage (1604). These duties were fixed at a certain rate; for instance, there was a duty of 2s. 6d. on every hundred-weight of currants imported into the country.James imposes illegal taxes. James, of his sole authority, trebled this duty, and afterwards, without asking the consent of Parliament, imposed heavy taxes upon almost all merchandise. In principle there is no distinction between the illegal levying of a direct or an indirect tax. The ignorant, however, are much more struck by that which comes plainly before them. Hence, had James attempted to raise a direct tax, such as the subsidies granted in Parliament, which were levied on land and articles of personal property, he would have aroused far more indignation than he did by the imposition of illegal customs. The subsidy must have been paid directly into the hands of the tax-gatherer, whereas the illegal duties were paid in the first instance by the merchants, and the fact that these merchants repaid themselves out of the profits of the consumer by raising prices, was not obvious to the vulgar. The people, however, really suffered in purse as well as in right, and Parliament would have been wanting in its duty, if it had not protested against this interference with the property of the subject.

The person of the subject was no safer than his property.

It is contrary to the common law of England to force any man to criminate himself. The Courts of High Commission and Star Chamber, however, did not follow the procedure of the common law courts, and were in the habit of tendering the prisoner an oath, technically called the oath ex officio, to answer truly all questions put to him. Two Puritans, for refusing to take this oath, were imprisoned by the Court of High Commission.Illegal commitments. The common law allowed every man committed to prison upon a criminal charge, to apply to the court of King’s Bench for a so-called writ of habeas corpus, directing the [p. 16]gaoler to produce his prisoner and the warrant upon which he was committed before the court on a stated day.[10] The judge, upon view of the warrant, discharged the prisoner, released him on bail, or sent him back to prison to await his trial, according as the charge against him was no offence in the eye of the law, or a bailable offence, or one for which no bail could be received.

The two Puritans in question were brought before the judges of the King’s Bench on a writ of habeas corpus.Arbitrary procedure of Court of High Commission. Fuller, their counsel, argued that they ought to be released, because the High Commissioners had not been empowered by law to imprison, or fine, or administer the oath ex officio. This argument struck at the root of the authority of the High Commission, and Fuller was himself summoned before the court, on the ground that he had slandered the king’s authority. He refused, like his clients, to take the oath, “to answer truly all questions put to him,” and applied to the Court of King’s Bench for a prohibition to stay the proceedings. It was by means of such prohibitions that the common law courts were accustomed to prevent the ecclesiastical courts from meddling with cases which properly came under the cognizance of the common law. The judges sent the prohibition, but at the same time signified that they should not interfere, if the High Commissioners charged the prisoner with heresy and schism. The Puritan advocate was accordingly convicted of heresy, fined £200, and committed to prison. The common law judges would not interfere in his favour, though he appealed again to them, and he seems, eventually, to have regained his liberty only by submitting, and paying the fine.[11]

The Courts of Star Chamber and High Commission, however illegally their jurisdiction was acquired and conducted, at least brought definite charges against the accused, and allowed him a [p. 17]form of trial.Arbitrary action of King’s Council. The King’s Council went even further than this, and constantly committed political opponents of the government, without bringing any charge against them, or allowing them the benefit of a trial. The imprisonment extended from weeks, or months, to years, and the writ of habeas corpus, which ought to have protected any subject from such an outrage, was rarely obtainable. In the case of Arabella Stuart, the causeless displeasure of the king formed the ground of a life-long imprisonment. This lady, who was first cousin to James, married, through pure affection, a distant relation, William Seymour, a descendant of Mary, the youngest daughter of Henry VII.Case of Lady Arabella Stuart. James, jealous of the union of two relations, both of whom had a distant claim to the crown, confined Seymour in the Tower, and placed Arabella in confinement at Lambeth. Both made their escape, with the intention of meeting at Leigh, near Blackwall, on board a French vessel, which was engaged to carry them across the Channel. Arabella arrived before her husband, and, in spite of her entreaties, her attendants, in fear of pursuit, forced the captain to sail. Seymour, on his arrival, finding the French vessel gone, hired a collier, and was landed in safety at Ostend. Arabella was not so fortunate. When within sight of Calais, a vessel, sent from Dover in pursuit, overtook the fugitive, and carried her back to England. On her arrival, she was immediately committed to the Tower, whence she wrote to the two chief justices, imploring them to secure her a trial by the usual writ of habeas corpus: “And if your lordships may not, or will not, grant unto me the ordinary relief of a distressed subject, then, I beseech you, become humble intercessors to his Majesty, that I may receive such benefit of justice as both his Majesty by his oath hath promised, and the laws of this realm afford to all others, those of his blood not excepted. And though, unfortunate woman! I can obtain neither, yet, I beseech your lordships, retain me in your good opinion, and judge charitably, till I be proved to have committed any offence, either against God or his Majesty, deserving so long restraint or separation from my lawful husband.” Arabella’s just demand remained ungranted. Her marriage was no crime at law, and had she been brought before the judges, they could hardly have done less than order her release. The idea of attempting to change the succession would [p. 18]have been ludicrous, if true, but there was no ground for suspicion of political motive in the marriage to give a shadow of excuse for her restraint. Separated from her husband, and broken-hearted, Arabella lost her reason, and, after some four years of confinement, at last died in the Tower.

The Countess of Shrewsbury, Arabella’s aunt, was brought up before the council, on the charge of being an accomplice in her niece’s escape. Refusing to implicate herself, by answering in any way to a charge so unknown to the law, she bravely replied, that, if the council had a charge against her, she would be ready to answer before her peers. Such an appeal to the hated liberties of the subject was not suffered to pass unpunished, and for several years her name appears in the list of unhappy inmates of the Tower.

It was not only the king’s animosity which was to be dreaded, but the greed of the court. The interests of the nation were bought and sold by courtiers and ministers. Several of James’ council were in receipt of salaries from the King of Spain. Others were in a nefarious league with the pirates who then preyed on our shipping. The story of Sir John Eliot and Captain Nutt sheds a flood of light on various judicial and executive anomalies of the reign. In 1623 Eliot was Vice-admiral of Devon. Amongst his duties were those of boarding pirate vessels, and deciding upon the lawfulness of prizes. Captain Nutt, an English pirate, who, at the head of several ships, had for three years past ranged the seas between the coasts of England and America, was notorious alike for audacity and cruelty. Sailing to Torbay and landing in force whenever he came ashore, he dared the vice-admiral to seize him, and boasted of the pardons he had already obtained. Armed with a copy of one of these pardons, conditional on the captain’s surrendering himself within a certain time, Eliot risked his life and went on board the pirate vessel. There was little doubt that the time within which the pardon was valid was already past, but Nutt, acting probably on the supposition that Eliot could only be influenced by mercenary motives, agreed to surrender himself, and to pay a fine of £500, together with six packs of calves’ skins. If the pardon were good, the fine would be shared between the vice-admiral, Eliot, and the lord-admiral, Buckingham. Directly the man was ashore, Eliot placed him under arrest, and then wrote an account [p. 19]of the whole transaction to the council. He took occasion to point out how the pirate, even while treating, had audaciously seized a Colchester brig, laden with woods and sugar to the value of some £4000, but left the question of the validity of the pardon entirely to their lordships’ decision. The first result of this was, that Eliot received a letter from Conway, the under-secretary of state, highly commending him for his good service, and intimating that he should before long receive the honour of kissing the king’s hand. Within a few days Eliot repaired to London, not, however, to kiss the king’s hand, but to become a prisoner in the Marshalsea, and answer in the Court of Admiralty charges preferred against him by the Council Board. The pirate, Nutt, to give his court friends an excuse for shielding him, had the audacity to come forward as the accuser of his captor, alleging that Eliot, both by letter and message, had urged him to sail to Dartmouth and make prizes of divers ships that were there, laden with goods and money out of Spain; and that it was not until thus encouraged that he had ventured on seizing the Colchester brig. The letter Nutt was unable to produce; the charges were denied both by Eliot and his officers. The judge of the Admiralty, in his reports to the council, did not venture to express an opinion in regard to Eliot, but pointed out how the lord-admiral’s interests might be neglected, if the vice-admiral were kept long absent from his post in Devon. But while Buckingham at the time was in Spain, Eliot’s enemy, and Nutt’s friend, Sir John Calvert, the principal secretary of state, was in England. It was through his influence that the council had proceeded against Eliot. The pirate had rendered him some service in the establishment of a colony in Newfoundland, and if his word may be believed, this was his sole motive for seeking to blacken the character of the vice-admiral, and obtain a pardon from the king for that “unlucky fellow, Captain Nutt.” It was no wonder Eliot felt angry and used stronger language in writing to Secretary Conway than he usually employed. “I cannot so much yet undervalue my integrity, to doubt that the words of a malicious assassin, now standing for his life, shall have reputation equal to the credit of a gentleman.” Nutt, however, by means of his powerful friend, obtained his pardon and, in addition, a grant of £100 out of the ship and goods seized at Torbay. The duration of Eliot’s imprisonment is uncertain; probably he [p. 20]remained in the Marshalsea until the following October, at which time Charles and Buckingham returned from Spain. In the following month he was canvassing for a seat in the last of James’ parliaments.[12]

While person and property were thus dealt with, it was hardly likely that there should be any recognition of the later rights of freedom of speech and freedom of thought. Presbyterians and sectarians were forced to fly the country, in order to escape imprisonment.Puritans persecuted. Puritan preachers were ejected from their livings. Puritan writers were prosecuted in the Star Chamber. James himself made a jest of the fines inflicted on them;—“it were no reason that those that will refuse the airy sign of the cross after baptism should have their purses stuffed with any more solid and substantial crosses.”[13] But persecution that does not go far enough to extirpate its victims defeats its own ends. Sympathy was felt for the Puritans, their opinion spread, and the division between the two parties grew wider and wider. Clergymen who found favour at court adopted doctrines approaching to those of Rome, and supported the power of the crown by teaching the duty of passive obedience, and the doctrine of the Divine Right of kings. Clergymen who found favour with the people taught that in the plain words of Scripture is to be found all that the Christian needs for his guidance; and denounced to their hearers, as sinful and displeasing to God, popish ceremonies and doctrines, and the worldly court-life, with its drinking, swearing, acting, fine dressing, and dancing.

Thus, at the end of James’ reign, men of very various opinions were all alike designated Puritans.Word Puritan designates men of various opinions. There was the sectarian, who desired that each separate congregation should be allowed its own special form of worship; the Presbyterian, who desired to see a church similar to that of Scotland established in England; the churchman, who objected to popish ceremonies and doctrines; the patriot, who, from opposing tyranny in the State, came to mistrust a church that taught the duty of passive obedience to kings’ commands; and, lastly, the earnest man, who, by merely leading, in his own person, a pure life, seemed to reprove [p. 21]the manners of the court; all these became alike objects of the scoffs and jeers of the king’s friends, and were classed together as factious hypocrites and Puritans.

But neither James’ pretensions to absolute power, nor his actual infringement of the constitution, nor the persecution of Puritans, nor the vices of his court, did so much to alienate the affection of his subjects, as did the conduct of his foreign policy.James’ foreign policy cause of division between himself and his subjects. The Thirty Years’ War had now begun. Matthias, Emperor of Germany, ruler of Austria, Hungary, and Bohemia, was childless. To secure the succession, he caused his cousin Ferdinand, archduke of Styria, to be crowned as next king of his great kingdoms of Bohemia and Hungary.[14] This prince had been brought up by the Jesuits, and was so ardent a Catholic that he said he would sooner beg his bread from door to door, than that the Catholic Church should suffer injury. He had long since driven the Protestants out of his own duchy of Styria. Sooner than accept such a fanatic as their king, the Bohemians, of whom the majority were Protestants, rose in rebellion, and offered the crown to one of their own persuasion, Frederick, prince of the Palatinate,[15] who [p. 22]accepted the dangerous gift, and was crowned King of Bohemia (August, 1619).

Thirty Years’ War. This was the origin of the great religious struggle between Catholics and Protestants, which is called the Thirty Years’ War. Frederick, the Protestant champion, had for his enemies, Ferdinand, elected Emperor of Germany on the death of Matthias (1619); the Catholic princes of the German empire; and Philip III. of Spain.

The Austrian Emperors of Germany, and the Kings of Spain, Milan, and the Netherlands, being near relations, always acted in one another’s interests. Jealousy of the united power of Spain and Austria inclined France to prefer political to religious considerations, so that it usually supported the Protestant princes in withstanding the encroachments of the emperors; but it was useless at the present time for Frederick to look for help to a country torn by civil dissensions, and governed by a minor.

From James, his Protestant father-in-law, whose daughter, Elizabeth, he had married amidst the rejoicings of the English (1613), as well as from his fellow Protestant princes of the empire, he might, not without reason, hope for support, in a war nominally undertaken in the interests of the Protestant cause.

James, however, hating war, had made peace, on his accession, with the old Catholic enemy, Spain, and declared his intention to the French ambassador, of “avoiding war as his own damnation.” But, on the breaking out of the Thirty Years’ War, the king found himself placed in a dilemma. For he must either give up his theory of non-intervention, or suffer England to fall from the proud position to which Elizabeth had raised her, as head of the Protestant States. Even now, when we recognize the full evil of war, it seems hardly generous in those themselves possessed of liberty to refuse assistance to a free people maintaining their freedom against foreign armies. To English Protestants, in whose minds the remembrance of the Armada was still fresh, it seemed at once both base and foolish to look on [p. 23]with indifference, while a Protestant people were deprived of liberty of conscience by armies composed of foreigners and Catholics. Protestant Europe was one country; and a blow struck at one Protestant State was regarded as a blow struck at the interests of all Protestant States.

James’ reasons for refusing to assist his son-in-law James, however, acting in opposition to the wishes of his subjects, refused to support his son-in-law. In the first place, he desired to avoid hostilities with Spain, in the interests of a match that he had been negotiating for the past six years between the Prince of Wales and Philip the Third’s daughter, to whose dowry he cannily looked as a means of paying his debts, without applying to Parliament for aid. He had just executed England’s greatest captain, Sir Walter Raleigh, to please Philip. In the second place, he disliked the idea of assisting subjects in rebellion against their prince. In favour of the first motive, there was nothing to be said. Who could uphold a King of England in relying on foreign gold for the support of his government, rather than on the good-will of his subjects? In favour of the second more might be urged, though not from James’ point of view. The Bohemian nobles, the authors of the rebellion, were rapacious and lawless, and without the moral qualities necessary for the conduct of a revolution and the establishment of a free government. A state of anarchy in Germany was foreseen as the probable result of their success, and even several Protestant princes refused to assist Frederick in weakening the imperial power, by which alone some sort of law was maintained between the different States that composed the empire. Accordingly, neither England nor France took part in the struggle; the Protestant princes made peace for themselves (July, 1620); and Frederick was defeated and driven out of Bohemia (Nov., 1620). When the armies of Spain and Austria proceeded to invade the Palatinate, Frederick’s hereditary dominions, James summoned a Parliament, with a half-formed resolve of breaking with Spain, and taking an active part in the war (1620).

It was impracticable for England to maintain a large army in the Palatinate, and even the attempt would have required supplies far larger than the country was disposed to grant. James was aware of these facts, and therefore the slower to enter upon hostilities. Commons press James to enter on spirited policy, but slow to grant necessary funds.It must be allowed that the Commons acted unreasonably. [p. 24]The country gentlemen, who came up to Westminster once in five or six years, were not enlightened by newspapers, and had no means of acquainting themselves with the intricate course of foreign politics, or of forming any correct estimate of the probable cost of a war. Now, while knowledge of their own incapacity prevented them from pretending to direct operations, their Protestant zeal caused them to press James to assist his son-in-law, and their ignorance to suppose that this could be done at comparatively a small expense to the country. Elizabeth had always had the skill so to direct the blow that it should inflict the greatest injury to her adversary at the least possible cost to herself. She would have seen that the sea was England’s field of fame, and would never have marched an army to Heidelberg. Had she still sat on the throne, perhaps a dash upon some Spanish port might have rendered the Protestants a material assistance, by drawing Philip’s armies off from Germany. But her foreign policy, when not marred by misplaced parsimony or favouritism, had been marked by her exceptional genius, and it was unreasonable to expect her commonplace successor to strike out a line of action at once spirited, effective, and economical. It was probably fortunate for England that he never heartily made the attempt.

The Parliament was asked for money sufficient to maintain for the winter some regiments of English volunteers, engaged in defending Heidelberg, the capital of the Palatinate.Commons petition James to marry his son to a Protestant princess. But the Commons, before voting money, desired to see the king commit himself to a decided policy, and prepared a petition, begging him to marry his son to a Protestant princess, and to make war on Spain. James, hearing beforehand of the contents of the petition, wrote a letter, forbidding the House to meddle with his son’s match; and adding, as a warning to those who should disregard the royal command, that, “as for liberty of speech, he was free to punish any man’s misdemeanours in Parliament, both during and after their sitting.” In meddling with matters of peace and war, the Commons were not so sure of their ground, but liberty of speech[16] they regarded as a precious inheritance from their [p. 25]earliest ancestors. A second petition was at once prepared, begging his Majesty, “such a wise and just king, to recognise liberty of speech, their ancient and undoubted right.” James replied by saying “he would not infringe their privileges, only he did not like their style of speaking—how could any privileges be their undoubted right and inheritance, when these were all derived from the grace and permission of his ancestors and himself?”

Commons enter in their journals declaration of their privileges. The Commons, too wise to let such doctrine as this pass unchallenged, entered a protest in their journals (18 Dec., 1621), to the effect that, ‘Their liberties and privileges were the undoubted birthright of the subjects of England; the State, the defence of the realm, the Church, the laws and grievances were proper matters for them to debate; members have liberty of speech, and freedom from all imprisonment for speaking on any matters touching Parliament business.’ James, in the full assembly of his council, and in presence of the judges, caused the journal-book to be brought before him, and, with his own hand, erased this protestation, declaring it to be invalid, void, and of none effect.

The dissatisfaction of the nation at the king, and his Spanish Catholic match, was greatly increased after the dissolution of this Parliament (6 Jan., 1622).Protestants defeated. Abroad, the Protestants were being defeated, persecuted, crushed. Frederick was driven, not only out of Bohemia, but out of [p. 26]his hereditary dominions, the Palatinate, and forced, with his family, to take refuge in Holland, and live on the alms of the Prince of Orange. Protestants were banished from Austria Proper. In Bohemia, the Protestant faith and civil liberty disappeared together. In the Palatinate, the Protestant worship was suppressed. In France, the government was in arms against the Huguenots, and succeeded in wresting one stronghold from them after another. Spain seized the hopeful opportunity to renew the war with Holland.

Spanish marriage spoken, written, preached against. The Puritan pulpits “rang against the Spanish marriage.” In vain James told the bishops to prevent the clergy from preaching on such topics; in vain he issued proclamations, forbidding the people to talk; their voices could no more be restrained than a “mountain torrent.” Pamphlets were written and published which risked the ears, if not the lives of their authors.Tom Tell-Truth. Most malignant of all, “Tom Tell-Truth” attacked the king and his government on every side.

“I, a poor unknown subject,” says the pamphleteer, “who hear the people talk, will undertake that discontinued but noble office of telling your Majesty the truth. Some there are that find fault with your government, even to wishing Elizabeth were alive again, for we have lost by change of sex. Great Britain, say they, is a great deal less than little England was wont to be. The excess of peace hath long since turned virtue into vice, and health into sickness.

“The Spaniards and the Duke of Bavaria play with your Majesty as men do with little children, at handy-dandy, which hand will you have? and give them nothing. The very losers at cards fall a cursing and swearing at the loss of the Palatinate; and, when told of your Majesty’s proclamation not to talk about State affairs, answer in a chafe, ‘You must give losers leave to speak.’

“You sent my Lord of Doncaster into France to mediate peace. It would have been better had the money spent on that embassage been given to the poor Huguenots; they may well call England the ‘Land of Promise.’ The princes that serve the Pope send arms; you—that should fight the battles of the Lord—ambassadors.

“No need for your Majesty to fear the Puritan religion; if a king will be absolute and dissolute, it is a wonder he will suffer any other; for it may be observed in some parts of Christendom[17] that let a king ruling over a Protestant people be never so wicked in his person, nor so enormous in his government, let him stamp vice with his example, let him remove the ancient bounds of sovereignty, and make every day new yokes and new scourges for [p. 27]his poor people, let him take rewards and punishments out of the hand of justice, and distribute them without regard to right or wrong; in short, let him so excel in mischief, ruin, and oppression, as Nero compared with him may be held a very father of the people. Yet, when he hath done all that can be imagined to procure hate and contempt, he may go boldly in and out to his sports, clothed in his quilted garments, stiletto-proof, he shall not need to take either the less drink when he goes to bed, or the more thought when he riseth.

“His minions, a pack of ravenous curs, think all other subjects beasts, and only made for them to prey upon; they may revel and laugh, when all the kingdom mourns. His poor Protestant subjects shall only think he is given them of God for the punishment of their sins, for the preachers shall praise him and make the pulpit a stage of flattery. He ought to be obeyed, not because he is good but because he is their king. The subject is tied to such wonderful patience and obedience as doth almost verify that bold speech of Machiavel, when he said, ‘Christianity made men cowards.’”[18]

Charles and Buckingham go to Spain. James, after quarrelling with his Parliament, eagerly renewed the Marriage Treaty with Spain. He hankered more than ever after the Infanta’s dower, and hoped, by means of Philip’s interest with the Emperor, to secure the restoration of the Palatinate to Frederick. The Spaniards, on their side, were ready for a treaty which would secure them from a war with England while fighting in Germany. Following the suggestion of the Spanish ambassador, Charles undertook a secret journey to Spain, intending to conclude the treaty in person, and return home with his bride by his side (Feb., 1623). He was accompanied only by his father’s favourite, George Villiers, Marquis (afterwards Duke) of Buckingham.

Philip IV. took advantage of this foolish act to raise his demands, and obtained the consent of both James and Charles to secret articles, in which they engaged never to put the laws against Catholics into force, and to obtain the consent of Parliament to their repeal within three years. The promise was worthless; for James well knew the Parliament would never consent.

Marriage Treaty with Spain broken off. Wearied by the delays caused by the Spaniards, Charles returned home (Oct., 1623) before the time agreed on for the performance of the marriage ceremony, and afterwards wrote to the Earl of Bristol, with whom he had left his proxy, that there was to be neither marriage nor friendship, unless Philip consented to restore the Palatinate to Frederick by force of arms. This demand broke off the [p. 28]treaty; for whatever delusive hopes Philip had held out to James, he had never undertaken to do more than endeavour by his interest with the Emperor, to effect a peace favourable to Frederick. “We have a maxim of State,” said a Spanish minister, for once speaking the truth,“that the King of Spain must never fight the Emperor.”

Money voted by Parliament to carry on war with Spain. Buckingham, who had quarrelled with the Spaniards, was now eager for war. James found his favourite would leave him no peace till he summoned a Parliament, which he did sorely against his will, and then Buckingham, with Charles by his side to confirm his story, gave the two Houses a false account of what had taken place in Spain, declaring that the Spaniards broke off the match because the prince would not become a Catholic. James’ court was not a good school for training a young prince in the duties of veracity; and it was certainly unfortunate for Charles’ character that the circumstance of his first introduction to Parliament should have been of so ambiguous a nature. However, the story thus supported was believed for the time, and the question of peace and war with Spain being submitted to the Commons’ consideration, they voted a subsidy of £300,000 to defend the coasts and help Holland. The same year four regiments crossed the Channel to assist the Dutch in fighting the Spaniards in the Netherlands (1624).

French Marriage Treaty. While the nation desired a Protestant alliance, the king only thought of a dowry. James now proposed to marry his son to another Catholic princess, Henrietta, sister of Louis XIII., King of France. He died, however, before the marriage took place, after a reign of twenty-three years (25th March, 1625). Though a French marriage was hailed as a deliverance after the Spanish project, yet the history of the next twenty years will perhaps seem to justify the Commons’ antipathy to any Catholic marriage.

[1] Money was about four times its present value, that is, one shilling then could purchase as much food or other necessaries of life as four shillings now; so this would now represent land which would bring in £8 a year as rent and cost say £250 to buy.

[2] Socage is probably derived from Saxon soc, “liberty,” “privilege,” “franchise.” Socagers were bound to attend the court of the lord to whose soc or “right” of justice they belonged.

[3] The copyholder held land of the lord of the manor, subject to certain restrictions and agricultural services enumerated in the copy of the roll of the estate. So long as he performed those services he might not be dispossessed.

[4] Though this is substantially true as a contrast to the position of the ministry in the 16th century, it would be a great mistake to disregard the influence of the forms under which the constitution works. (I.) Even now the control of the Commons is not so great as it seems. The ministers are not mere delegates, for Parliament controls rather than directs; it has no right to tell the Queen’s ministers what to do, though it can veto their proposals, and censure them for their acts when done; the initiative remains with the cabinet. (II.) The influence of the crown is more than it seems. (i.) It has a voice in discussing despatches which settle foreign policy. (ii.) Though it cannot exclude from office a man who has made himself indispensable to the nation, it has, no doubt, a negative voice in the selection of the less conspicuous members of the cabinet, and thus exercises a real, though imperceptible, influence on the attitude of rising politicians.

The form is always of vast importance in constitutional questions. The popular influence, which seems to be the substantial power, is the wind that fills the sails and gives the motion; but the exact direction of the motion must still depend in a large measure on the helmsman. The shipwreck of the 17th century came from an attempt to sail in the teeth of the wind. A skilful helmsman may do much by gaining and losing tacks, but the Stuarts were not skilful.

[5] Under the Tudors, juries had been fined and imprisoned for deciding against the crown. If they decided for the crown, though unjustly, they could not be punished, because they could not have been tampered with by the sovereign!

[6] The common law consists of customs handed down from Norman times, and of the judgments of judges founded upon those customs; statute law of acts of Parliament.

[7] Thus in James’ time the Admiralty judge acknowledges the receipt of instructions, “by which I understand his Majesty’s resolution to continue Sir John Eliot in prison. I am glad I did forbear to deliver my opinion of the state of his cause, lest perhaps it might have differed somewhat.”—Forster’s Eliot, i. ii. 4.

[8] The king had two councils: his Privy Council, which advised with him in all State matters, and his Common Council. In the Common Council sat, not only all members of the Privy Council, but also some of the common law judges, and others added at the pleasure of the king.

Henry VII., 1492–1509.

|

+————————-+————————+

| |

Henry VIII., 1509–1548. Margaret = James IV. of Scotland.

| |

+——-+——————-+————————————+ +——————+

| | | |

Edward VI. Mary. Elizabeth. James V. of Scotland.

1548–1553. 1553–1558. 1558–1603. |

|

Mary, Queen = Lord Darnley,

of Scots. | H. Stuart

+——————————————-+

|

James VI. of Scotland and I. of England, 1603–1625.

|

+————————————————-+——————————-+

| |

Charles I., 1625–1649. Elizabeth = Frederick.

| |

+——————-+————————+ +——————————-+——————————-+

| | | | | |

Charles II. Mary. James II. Chas. Louis. Rupert. Sophia.

[10] Habeas corpus ad subjiciendum are the first words of the writ to the gaoler, meaning that he is to have the person (of the prisoner) to produce before the court (so habeas corpus ad testificandum are the first words of a writ for producing a prisoner to give evidence). The writ was anciently called corpus cum causâ, because it required the return of the cause of detention, as well as of the body imprisoned. The principle of the writ was contained in the Magna Charta of King John, which enacted that “no freeman should be imprisoned but by lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” It was used between subject and subject in the time of Henry VI., and against the crown in that of Henry VII., so that it was fully recognized as law long before the re-enactments in the reign of Charles I., and the Habeas Corpus Act of Charles II., 1679.

[11] Gardiner, Hist. of Eng. (1603–1616), i. 445.

[12] Forster: Life of Sir J. Eliot, i. 2.

[13] Ellis Orig. Letters, iii. 450: Coins were called crosses from the stamp of the cross on the reverse, as sovereigns from the king’s head on the obverse.

Ferdinand = Isabella Maximilian I., Emperor

of | Spain. of Germany,

| Archduke of Austria.

| |

| +————————-+

| |

Joanna = Philip the Fair.

| Archdukes of Austria,

Kings of | Spain, Kings of Bohemia, Hungary,

Milan, | Naples, and Emperors of

and Nether-| lands. Germany.

|

+——————-+——————————————————————————————+

| |

Charles V., Emperor of Ferdinand I. (emperor

Germany, 1519–1556. after resignation of

| his brother Charles V.),

| 1556–1564.

Philip II., |

1555–1598. +————————-+——————-+

| | |

| Maximilian II., Charles, Archduke

Philip III., 1564–1574. of Styria.

1598–1621. | |

| +————————————-+————+ |

| | | |

Philip IV., Rodolph II., Matthias, Ferdinand II.,

1621–1667. 1574–1612. 1612–1619. 1619–1637.

[15] The Count Palatine represented, in theory, the king or emperor as judge in his own palace. Barons, especially those of frontier provinces, had similar royal judicial privileges delegated to them. Such provinces were called palatine. In Germany there was an upper and lower Palatinate; the lower Palatinate comprised the upper part of the rich Rhine valley, with Heidelberg for its capital, and conferred a vote at the election of the emperors of Germany.

[16] Even in Edward the Third’s time, the Commons seem to have been allowed to debate on many things concerning the king’s prerogative; and Henry IV. promised to take no notice of any reports made to him of their proceedings before such matters were brought before him by the advice and assent of all the Commons. A Parliament, or “speaking-house,” would be a poor guardian of liberties without itself having liberty of utterance. The principle was well stated nearly half a century after this (1667): “No man can doubt but whatever is once enacted is lawful; but nothing can come into an Act of Parliament but it must be first affirmed or propounded by somebody; so that if the Act can wrong nobody, no more can the first propounding. The members must be as free as the Houses; an Act of Parliament cannot disturb the State; therefore the debate that tends to it cannot; for it must be propounded and debated before it can be enacted.”—May’s Parl. Practice, 102.

Besides freedom of speech on subjects of Parliamentary debate, the principal privileges of Parliament were:

The right of both Houses of judging and punishing their own members for any misdemeanour committed in Parliament.

The right of the Commons of determining any disputed election.

The right of members of both Houses to enjoy freedom from arrest, and exemption from all legal process, while Parliament was sitting, except on charges of treason, felony, and breach of the peace.

[17] I.e., in England.

[18] Somers’ Tracts, II. 487–9.

[p. 29]

CHARLES’ FIRST PARLIAMENTS.—IMPEACHMENT OF BUCKINGHAM.—PETITION OF RIGHT.—(1625–1629).

Little was known of the new king, who was only twenty-four years old when he came to the throne, and had seldom appeared in public. His manners were grave and cold; he loved order and propriety. “I will have no drunkards in my bedchamber,” he said, and turned out of office one of Buckingham’s own brothers. The courtiers followed the lead of their master, and led outwardly decorous lives.[19]

Certainty of quarrel between King and Parliament. But all hopes that were entertained of good agreement between king and people were doomed to a speedy end. Charles, who from his earliest years had heard taught at his father’s court the doctrine of the Divine Right of kings, regarded it as the duty of Parliament submissively to vote supplies and carry out the wishes of the monarch, without questioning his government or bargaining for redress of grievances. His subjects, on the other hand, still smarting at James’ disregard of the laws of the land and the privilege of Parliament, were determined to make the new king acknowledge the limits which the laws set to the prerogative of the Crown.

An immediate cause of quarrel between Charles and the nation lay in the ascendancy of Buckingham, whose popularity had faded almost as soon as born. For if he had broken off the Spanish match on the grounds alleged by himself, he had since brought about the king’s marriage with another Catholic, Henrietta Maria, sister of Louis XIII. It is rare for a favourite to [p. 30]remain supreme during the life of one master; still more rare for him to gain the affection of a second.Buckingham hated; his character. Disappointment that Buckingham had not been ruined on the death of James now intensified the hatred felt by all classes towards him. Almost every officer employed by the Government was his creature, and at his command. “He on whom the duke smiled, was advanced; he on whom he frowned, cast down.”[20] The highest nobles in the land found that, to stand well in the eyes of the king, they must court the favour of this haughty minion—this upstart country squire. Buckingham himself was ill-fitted to exercise power. Handsome, of fascinating manners, courageous and not implacable, he was yet vain withal, insolent, reckless, no genius, and utterly selfish; a man who would embroil his country in war to salve a wound of vanity, and then, after pledging his country’s word, break it again to satisfy a change of whim. Such was the adviser with whom Charles met his first Parliament—a Parliament he soon summoned, as he was preparing a fleet for an expedition carefully kept secret from the country, and found himself in urgent need of money to fit this out. (18th June.)