Title: On the face of the flood

Author: Mary E. Ropes

Release date: August 10, 2025 [eBook #76666]

Language: English

Original publication: London: The Religious Tract Society, 1913

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

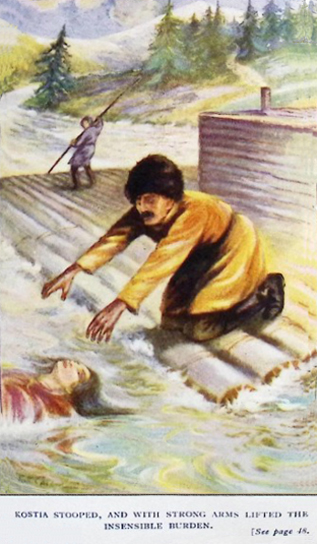

KOSTIA STOOPED, AND WITH STRONG ARMS LIFTED

THE INSENSIBLE BURDEN.

By

MARY E. ROPES

Author of

"Karl Jansen's Find," "Caroline Street," etc.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 Bouverie Street and 65 St. Paul's Churchyard E.C.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

III. A DREAD AWAKENING—KIDNAPPED

ON THE FACE OF THE FLOOD

The Ring that Rolled Away

"MY little son, Sergey, what means this? Thou hast a face on thee as long as my axe-handle! Is there any fresh trouble, child?"

"Ach, yes, Matvey Philipitch, and a very strange trouble it is, God knows! And with a secret to it, too, worse luck; for methinks there is danger for me, whether I find it out or no."

"A secret, my boy? A new trouble? And surely thou hadst enough before. But tell it out to me, so shalt thou rid thy poor little heart of a part, at least, of its burden."

"Have you time, little father, to listen now? I would fain tell my story at once, for I think I cannot bear it any longer alone."

"Yes, I have time," replied Matvey. "But here in the wood is no place for confidences, where thine Uncle Abram might be hiding, and spying, and listening, as his wont is, behind the pines. Come back with me to my home, and my good wife and I will consult with thee how best to help thee in thy trouble."

Sergey followed Matvey farther into the forest, and came, after five minutes' walk, to a solidly built house. It was made of whole pine-tree trunks, the cracks being filled up with tarred tow.

The hut was one of a number scattered about among the trees, for this was a village of wood cutters and raftsmen. But Matvey was the foreman and paymaster, and in virtue of this, his cottage contained two rooms instead of only the solitary apartment which was kitchen, bedroom, and sitting-room, all in one, in the other dwellings.

Matvey was a man in the prime of life, and far better educated, and more intelligent, than the ordinary peasants. Sensible, honest, and reliable, he had the full confidence of his employer, and managed the wood-cutting in the winter, and the raft-making and launching in the spring, when the rivers opened their icy eyelids, and the snows, melting, swelled the flow and quickened the sluggish currents.

Matvey Philipitch Strogoff could not only read and write and keep correct accounts for his master, but he had learned to love his Bible, and daily he studied it, poring thoughtfully over its precious truths, till they bore fruit in his humble, consistent, upright, Christian life, and he became an influence for good in the wild forest where his work lay.

His wife, Christina Ivanovna, was his true helpmeet. And now, as Matvey and the boy Sergey entered the hut, Christina welcomed her young visitor very kindly. For well she knew what a miserable life he led with his uncle, Abram Kapoostin, ever since his parents' death from cholera two years ago.

Of late, too, Abram's conduct had been so strange, and he had neglected his duty so often, disappearing no one knew how, or whither, for twenty-four hours at a time, that the foreman had almost made up his mind to dismiss him. So Christina was not altogether unprepared for a crisis in the affairs of Sergey and his uncle, and was not surprised when her husband said—

"Christina, little dove mine, this poor child is in trouble again, and is come to tell us all about it. Now, Sergey, sit down here and tell thy story, keeping nothing back, so shall we know how to advise and help thee."

So the boy began his tale as follows, while Matvey and his wife listened intently—

"As you well know, kind friends, things have grown worse of late. You have seen that my uncle's heart was not in his work, and often he slipped away, and no one knew where he went or what he did. Nor know I even now. But a strange thing happened last night. My uncle came home drunk, and I awoke with the noise he made, and turning over, I watched him.

"Presently I saw him take from his big boot a little leather bag, and lay it on the table. Then there was a chink! chink! a ring of metal, a flash, and a sparkle, and something rolled off the table, and away into a dark corner at the foot of my bed. But Uncle Abram was too drunk to notice this. He sat there muttering to himself, and lifting a lot of bright things in his hands, and letting them drop, as though he liked the look and the sound of the golden shower. But after a short time he seemed to grow sleepy, and putting the jewels back into the bag, and the bag into his belt, he threw himself, just as he was, upon his bed, and in two minutes was snoring hard.

"But this morning, while we were drinking tea, he suddenly said to me, 'Sergey, did I wake thee when I came in last night?'"

"That was a hard question, little son," commented Matvey. "How didst thou answer?"

"I knew it was a sin to lie," replied the boy; "you have taught me that the children of God must be true in all things. So I took my poor little courage in both hands, and looking my uncle in the face, I said:

"'Yes, you waked me.'

"Then his face grew black with rage, and he shouted, 'And if awake, what didst thou see or hear?'

"'And pray,' said I, 'what should I see or hear?'

"And it was given me to speak quietly and almost carelessly, though my heart beat like your big clock, Matvey Philipitch.

"And I added, 'You know, uncle, you were very drunk, as you often are.'

"'Yes, yes, as I often am!' he cried, his anger seeming to calm down suddenly. 'That is nothing; that is no secret, is it?' And again he looked at me as if he would read my thoughts.

"'No,' I answered, 'certainly it is no secret that you are often drunk. The whole village knows that.'

"Then he got up to go out, but turned at the door. 'I like not thy face, nor thy manner this morning, Sergey,' he said. 'See that thou change both, or I will make thee rue it.' And with that he was gone.

"And then I ran to the corner whither the bright thing had rolled, and there, in the dark and the dust, I found, shining like a little red lamp, this!"

And opening his hand, he showed in the hollow of the palm, a broad, massive gold ring, in which was set one great ruby, with a wonderful light deep down in its heart.

Matvey took it up, and read, engraved on the inner side:

"'Yevgen to Elena.'"

"Strange!" said Matvey. "How came thine uncle, I wonder, by such a jewel as this? It must be of great value."

"I know not," replied the boy, "but therein, I am sure, lies a wicked secret, and the thought makes me unhappy. Moreover, he is sure to miss it when he comes to look over the rest of the trinkets, and he will question me, and I must speak the truth, and then he will kill me."

"Kill thee, child? No, that shall he not," exclaimed Matvey. "But if thou fear to go home to-night, thou canst stay here, and to-morrow I will make a plan to rescue thee, little son, from the fear and the thrall of this ungodly man. And as for this red stone ring, shall I keep it for the present and lock it up?"

"Yes, please do, Matvey Philipitch, and so one day we may learn to whom it belongs."

Matvey's Plan

AS the good foreman and his wife, with their young guest, sat round the table next morning, drinking their tea out of tumblers, in true Russian fashion, the door was rudely pushed open, and Abram Kapoostin stood there, glowering at the cosy little group beside the warm stove.

"Pray, what is the reason of this?" he said, his thick voice rough with anger. "I have been seeking my scoundrel of a nephew all through the wood, and now, forsooth, I find him here. What business have you, Matvey Philipitch, to entice away Sergey from his uncle and guardian?"

"He did not entice me," Sergey began to say, but the foreman silenced him with a gesture, and answered Abram himself.

"There has been—there could be—no enticing. The boy was frightened and unhappy, and so came to us, his friends, for comfort and protection; aye, and he shall have both, in spite of thee, Abram Kapoostin."

The man made no reply, but glared at Sergey from under frowning brows. The foreman went on—

"Some time ago, Abram, I said plainly to thee that I could not suffer thy frequent absences from work, and that if I had to speak again, I should feel it my duty to dismiss thee."

"Me? Dismiss me?" growled Abram. "Dismiss the best axe in the gang?"

"It is true thou art the best axe—the best workman when thou dost so choose," replied Matvey quietly. "But more often thou dost not choose. And no one knows what business other than the woodcraft claims thy time, and keeps thee from thy duty. And moreover, Abram, thou canst not deny that even when thou art here, the village kabak (dram-shop) is haunted by thee, and most of thy wage is spent on that devil's-fire drink that we call vodki. Idle, surly, drunken, unfaithful to God and to the master, an influence for evil in the gang, a bad example to all the younger men, a terror to this boy, whose guardian thou didst promise to be—what hast thou to say for thyself?"

Apparently the man had nothing to say in self-defence; the accusation was all too true.

Matvey continued: "I have warned thee more than once, but thou hast not heeded. Now the time is past; I warn thee no more, but dismiss thee. Here, take thy wages and begone, and see that thy hut is empty and clean by to-morrow, when a better man shall come to live there. This afternoon Sergey and I shall go over and fetch his things, but he returns to thee no more. Now go!"

At this stern dismissal, Abram's bloodshot eyes fixed themselves threateningly upon Sergey.

"All this trouble must be of thy doing, thou sly fox, thou thankless little beast!" he roared, frantic with rage. "Ach, well! I will be even with thee yet. I never forget, I never forgive! Thou hast compassed my ruin, and it shall go hard with me but I will compass thine. Be sure—very sure—of that, thou backbiting serpent!"

"Any more of this, and I give thee in charge of the forest police!" cried Matvey sternly. "Get out of my place, ere I lose all patience, and give thee what thou hast richly earned."

There was a tone in the foreman's ringing voice which even the burly, blustering Abram could not afford to ignore and disobey. One last baleful gaze he fastened upon the boy's troubled face, then he was gone.

"He is furious at the loss of the ring," Sergey said, when the unwelcome visitor had gone, "and I am in worse danger than ever. I dare not even work in the forest, for fear of meeting him. Oh, little father and mother, what can I do?"

"Listen, my son," said Matvey. "Last night the strong south wind and heavy rain made the river ice cracked and rotten, and in some places there is already open water. To-night or to-morrow the remaining ice will break up and float down the current, melting as it goes. Our Number 1 raft, the 'Swan,' is nearly ready to start, and thou shalt go on her as cook-boy and helper. What sayest thou, child?"

"Say—Matvey Philipitch? What can I say but a thousand grateful thanks? I shall grieve to leave you and dear, kind mother Christina, but I should never have a moment's peace or safety here, after those awful threats of uncle's. For even though you have dismissed him, Matvey Philipitch, he may be lurking about in the forest, watching and lying in wait for me. No, it is best every way that I go on the 'Swan,' as you say."

"If thou shouldst prefer to wait awhile longer under our protection, child, the second raft—the 'Wild Goose'—will be going later."

"No, father Matvey, I thank you—but no! I am anxious to be far away as soon as may be. But tell me, are all the rafts to be birds this year?"

"Yes, we shall have the 'Swan,' 'Wild Goose,' 'Duck,' 'Sea Gull,' and others. Last year we had flowers, such as the 'Water Lily,' 'Sunflower,' and so forth. The men take a pride in their rafts, and like them to have names. And I have known some of them grow so fond of their queer, unwieldy craft during the long voyage, that they have wept when they reached their port, and saw the timbers of the raft taken asunder, and the little cabin house, where the raftsmen had cooked, and eaten, and slept, hewn up for firewood."

"Perhaps I shall come to love the 'Swan' thus," said the boy. "But I shall be very lonely without you and mother Christina."

"I have friends in three of the towns through which thou wilt pass," said Matvey, "and to them I will give thee letters in case thou shouldst be sick or in any difficulty. For the rest, Ivan, the skipper of the 'Swan,' and his three sons are good, honest fellows, and they will be kind to thee. About passports there will be no trouble. My master, the Count, pays for a yearly 'permit,' which includes all his raftsmen, and Ivan has the certificate of a raft skipper, who knows all the shoals, the currents, the rocks, rapids, and other dangers. The voyage will take the whole summer, but thou canst return with the men by one of the steam cargo boats, working thy passage homeward, and tramping from whatever spot the steamer sets thee and thy companions down."

That afternoon Matvey and Sergey, according to their arrangement, went over to Abram's hut to get the boy's things. They found him clearing up the place, and packing his possessions. He looked round as his unwelcome callers appeared, and his surly face darkened.

"Sorry to trouble thee, Abram," said the foreman pleasantly, "but we need not do so for long. May Sergey pack away his things in this bag that I have brought?"

"Yes, yes! Take them and begone!" growled Abram. "I'm glad to be going myself to-morrow. A woodman's life is too dull for me, and I have friends with whom I can earn more in a night than I could do with my axe in a year. Ha! Ha! Sir Foreman, what say you to that?"

"Nothing, save that thou and thy fine friends will most assuredly come to a bad end sooner or later."

"Have done with your warnings, Matvey Philipitch. From this day I go my own way, and none shall hinder me."

"Until God hinder thee once for all, thou stubborn will! And hinder thee He shall, when the measure of thy sins is full!" said Matvey solemnly. "Come, Sergey, I see thou hast thy goods ready. Say farewell to thine uncle. It is not likely that thou and he shall meet again."

Abram laughed an evil, sneering laugh. "Nay," said he, "I am sure to see my dutiful nephew again. You see, Matvey Philipitch, I have a small account to settle with him, and this I would not forego, if I could."

"Well," said the foreman, "here he is! Settle it now!"

"No, no," retorted the man rudely. "Such matters are private between relatives. But I only postpone the affair. Some day—or, better still, some night—I will settle up old scores with this young rascal, and if there be anything left of him when I have got through, you are welcome to it, Sir Foreman."

"Come, little son, we have stayed long enough—too long!" said Matvey, shuddering at the malignant words and look of Abram Kapoostin. "Life is not long enough for us to waste time bandying words with a ruffian such as this. Come!"

A Dread Awakening—Kidnapped

NEVER had the finishing touches of any raft so keenly interested Sergey, as these of the "Swan." The chief object in the construction was to float in as small a compass as possible, as much timber as could be sent safely down the current.

This, and the care necessary to make it lie evenly and securely upon the water, made the building of the raft far less simple and easy a thing than at first sight it appeared. Upon the raft a little house or cabin was erected, strongly and firmly made, and into it were packed just the bare necessaries for the long slow voyage, though of course additional provisions could be obtained, and certain stores renewed at some of the places passed on the way.

The cabin was small, but it was wonderful how many things it was capable of holding. It contained a little stove which was to answer the treble purpose of warming the people, cooking the food, and drying the clothes.

A few low stools and a rough table formed the furniture. Beds there were none, but two shelves were used as sleeping-places. And if more than two people wished to sleep at the same time, there was always the floor.

By way of food they had a keg of sour cabbage for soup, some herrings in brine, several huge loaves of rye bread, a wooden bucket of Finnish salt butter, and a box of buckwheat grain for porridge. There were an old battered samovar, a broken-nosed teapot, a few tin pots and wooden spoons, and a knife or two, also two or three earthenware bowls. These things, with a pound or so of tea and sugar, just about took up the available space in the little cabin.

The brilliant shining of the sun for a day or two had completed the destruction of the ice begun by the south wind and rain. And now no ice was to be seen. The river was in full flood. And the morning came when Sergey said a grateful farewell to the good foreman and his wife, and joining Ivan and his three stalwart sons on the deck of the "Swan," began his long slow voyage.

With the blue sky and golden sunlight over him, kind people with him, new scenes and possible adventures before him, the lad felt lighter of heart than for years past. For, after all, he was only thirteen, and at that age the future looks very fair.

All day the "Swan" floated at a fair pace down the stream. And as there was a moon that night, and plenty of light by which to navigate the clumsy craft, there was no need to stop and moor the raft.

Right through the peaceful, solemn night they drifted in the cold white light, keeping in mid-stream so as to take full advantage of the strong current which prevails in flood-time. The woods were still white with the remains of unmelted snow, and now and again Sergey caught a fleeting glimpse of some furtive moving thing among the pine stems, and heard old Ivan mutter into his grizzled beard, "Volk!" (wolf), or "Zaitsa" (hare), or "Lysitsa" (fox).

That first night on the river Tihonka was a thing to be remembered for its novelty, its mystery, and its beauty. So much absorbed indeed was the boy that Ivan had to remind him of his duty as cook, and tell him to prepare supper.

All went smoothly enough that night and the whole of the next day, but towards nightfall the weather changed. A great wind rose, the sky was overcast, and the water was lashed to fury wherever there was space enough to be exposed to the gale.

"We must moor the 'Swan' to-night," said Ivan. "It would not be safe to run her through the darkness. And besides, we are reaching a rocky part of the river, and for this we must have light."

So when darkness began to settle down, the raft was moored close in shore, and the men, wrapping themselves in their sheepskins, lay down, two on the sleeping-shelves, two on the floor, and were soon snoring loudly. Sergey snuggled into a corner and tried to sleep too.

But the cabin was close and stuffy, and the boy could not close his eyes. Longing for a whiff of the fresh, pine-scented air, he got up noiselessly, so as not to rouse the sleepers, and stepped out on to the deck of the raft, and thence to a big flat boulder close to which the "Swan" was moored. Here he sat down, and presently, lulled by the soft sounds of the going in the pine tops, and the swirl of the water, he fell into a deep slumber.

Whether he slept for several hours or for only a brief time Sergey never knew. But he regained consciousness under a suffocating sensation, and a sickening sense of misfortune and danger.

As he came gradually to himself, he realised that he was no longer sitting on the rock where he had fallen asleep, but was being carried along in strong arms that seemed to make light of his weight. Some sort of a gag had been forced into his mouth, so that he could not cry out; nor could he loosen his hands and arms, so tightly was his sheepskin rolled about him.

Hardly awake, he did not struggle at first, but when he began to kick and writhe, fighting desperately for freedom, his worst fears were confirmed, for a hoarse brutal voice said in his ear, "Did I not tell thee we should meet again, thou fox—thou wolf-cub? And now I have thee, and thou shalt pay what thou owest, even to the last copeck."

Sergey could not answer, the gag prevented speech, but he shuddered from head to foot. Just when he had thought himself safe for ever from the tyranny of this bad man, here he was, in worse case than before, for Matvey and Christina were miles away, and Ivan and his sons fast asleep.

"There is no one to help me!" sighed the poor lad. "My uncle may have his will with me now."

Then the extreme of his misery recalled to Sergey's mind what he ought to have remembered before, and a cry went up from the boy's burdened heart to Him Who, watching over Israel, slumbers not nor sleeps.

Sergey could not speak his prayer aloud, but he knew that the Heavenly Father could hear the unspoken prayer, and it gave him comfort to feel that, after all, he was not quite alone or wholly friendless.

For ten minutes or so he was carried over what he was sure was very rough ground.

Then suddenly his bearer seemed to step over some threshold, and in a blaze of light he was set on his feet, the gag was removed, and he found himself in the centre of a barn-like building, and about him a number of rough-looking men who eyed him curiously.

"Here he is!" said Abram Kapoostin. "I'd been on a raft too often myself not to know where Ivan would moor such a night as this. And I was lucky to find him outside the cabin instead of in. I swore—comrades mine—that I would meet this young fox again, and I have kept my word. Now then, thou young thief and traitor, what hast thou done with my jewel?"

An Ordeal

IT was small wonder that Sergey for a long minute stood aghast, helpless with surprise and fear. But with a strong effort he pulled himself together, reflecting that it was certainly better and safer for him to be with several people than with his uncle alone. And anyway, as Matvey had told him, he was not really friendless, since the Heavenly Father was pledged to guard His trusting children, even as He had guarded Daniel in the den, and his friends in the burning, fiery furnace.

So when the question was repeated, "What hast thou done with my jewel?"

Sergey faced the speaker firmly and said, "I have it not; I handed it over to one who will try to restore it to its rightful owner."

"That am I!" shouted Abram. "Speak the truth for once, thou little viper! Was not the ruby ring mine?"

"Yes, certainly," replied Sergey, "if your name is Elena."

A loud guffaw went round the circle, and one huge man, who seemed to be in some sort the leader, said with a pleased chuckle, "He had thee there, Kapoostin!"

"'Yevgen to Elena' was plainly engraved inside the ring," said Sergey. "So it could hardly belong to this uncle of mine—at least, not rightfully."

"Ah! But with us might is right!" replied the big leader. "We have been oppressed and down-trodden in the past, so now we, in our turn, have become the oppressors."

"But all this is not to the point," interrupted Abram. "I for one believe not what the boy says. He most likely has the jewel hidden away upon his person. Captain, may I search him?"

"Yes," answered the big man. "But mind, no violence!"

"You dropped it, uncle, and it rolled into a corner when you were very drunk and did not notice. I picked it up and gave it into safe keeping, and there it is now!"

"So thou sayest! But I search thee all the same!"

Sergey submitted silently, and the search was a thorough one, but of course no ring was found.

"So the boy spoke the truth," said the chief when the search was over. "And thou, Elena, must look elsewhere for thy ring."

And again a burst of laughter shook the sides of the men.

"Sir Captain," said Sergey, "I was just starting on a raft voyage. My friends will miss me and be distressed. Have I your leave to go back to the river and rejoin them?"

"Let him not go, Captain!" cried Abram. "He will betray us to the police the next place the raft comes to, and then we shall be caught and sent to Siberia."

"It is quite likely, Abram Kapoostin, that this, or worse, may be thy fate anyway. But as for the boy," added the Captain, "well—I would rather keep him than let him go, of course, for he would be useful to us.

"Look here, youngster! Wilt thou join us? We are not altogether a bad lot. If we sometimes rob the rich, at least we do not harry the poor. Some of us are in service, some are artisans, others clerks, and a few are students. When a big, wealthy house is left in charge of careless or drunken servants we are burglars and take all we can find.

"And now and again a rich traveller or two pay toll, but we never maim nor murder. All of us being engaged in some sort of work, we can only meet occasionally to make plans and compare notes. We have all had grievances in the past, and now it is sometimes our turn to be on the upper end of the see-saw."

"Why try to explain all this to a mere child, Captain?" grumbled Abram. "If you want him, keep him. I will have him under my eye, and if he tries to get away, he shall suffer for it."

"Thanks, Kapoostin! When I am in need of thine advice, I will ask for it. Now, boy—wilt thou take service—say as page in a nobleman's house (there are large estates about here), and secretly be one of us and play into our hands, meeting with us now and again thus in the forest?"

There was dead silence for a minute. Then the lad's answer came in clear tones:

"No, Sir Captain, I will not!"

The men looked at each other in surprise.

"And why?" demanded the chief.

"There is more than one reason," replied Sergey.

"Let us hear them!"

"First, Sir Captain, my voyage on the raft was planned on purpose to get me away from my uncle, because I could be neither good nor happy living with him."

"Now for reason number two!"

"I was brought up by my parents," said Sergey, "to be honest and truthful, to believe in a good God, and to try to be obedient and faithful to Him. I could not continue thus if I became one of your band."

"Well now," said the chief, looking round at the faces in the torch-light, with an amused smile on his lips—"we have got it this time, have we not? Bless the brat! I would not have him at a gift after that! He shall go back to his raft and be rid of us all, and especially of this bad-egg uncle of his."

"He will betray us if you let him go, Captain," said Kapoostin.

"I don't think he will," replied the chief, "and moreover, I don't think he can. He has no idea who we all are, and as, at our meetings, we wear wigs and beards, he could not recognise any of us, even if he did happen to meet us elsewhere. But say, child—wouldest thou betray us—were it in thy power, and send us to Siberia?"

"No, Sir Captain, you have done me no harm; I would not betray you."

"On thy word of honour?"

"On my word of honour."

"Then farewell, little lad."

"Farewell, Sir Captain, and thank you."

"Take him back to the river, Kapoostin," said the big man. "And thou, Appolon, go too, to protect the boy from this uncle of his."

And the three passed out of the building and vanished into the darkness of the forest.

Eyes Shining in the Dark

NO one in the little rafthouse on the "Swan" ever knew of Sergey's adventure that night. For, tired with the arduous day's work, and sleepy from fourteen to sixteen hours' exposure to wind and sun, the raft skipper and his big sons slept heavily to the music of their own snoring.

So when the boy, left at the water's edge by his uncle and the guardian Appolon, crept noiselessly into the cabin, no one stirred foot or hand, and Sergey betook himself to his usual corner without disturbing the sleepers. Worn out with excitement and weariness, the boy fell asleep too, and knew nothing until he was roused by old Ivan next morning.

"How now, little son?" said the kind old voice. "Thou art not an over early riser, thou new cook-boy. Wake up, child, the samovar ought to have been boiling ere this. Didst thou sleep well?"

Sergey sat up rubbing his eyes.

"Not very, Ivan, but, all the same, I should not have been so lazy. I will make haste now and get your tea ready."

There were new experiences that day for the lad, and some were of such interest and novelty that they made him forget the strange happenings of the night before.

For after a while the river began to narrow again, changing into a turbid, rushing stream, running in rapids over rocks and stones, down a somewhat steep incline. It was just above this incline that the men drove their strong poles deep down into the sand and mud at the bottom to arrest the progress of the raft. They then threw out a plank (so narrow was the channel) on each side to make bridges to the banks.

"Now, Sasha! Now, Kostia!" cried old Ivan. "Quick and lively does it! On shore with you! Vassia and Sergey, stay with me."

In a minute the two elder sons, each with a coil of rope over his arm, had crossed the plank bridges, and now stood on the wooded, rocky banks, one on each side. One end of the coils of rope was securely knotted in huge iron rings screwed into the sides of the raft, while the rest of the rope hung in even coils over the left arm of the young men.

"Now, children, are you ready?" shouted Ivan, when Sasha and Kostia had stood at attention a moment while the "Swan" strained against the arresting poles.

Sergey had meanwhile quickly drawn in the bridge planks, while Ivan and Vassia kept the poles in their places. Yes, all was quite ready, for Kostia and Sasha had now taken a turn of their respective ropes round sturdy tree stems.

"Out with the poles! Let her go!" they shouted together.

And old Ivan and Vassia drew out the poles. The raft made a sudden rush which threw Sergey down and rolled him into the little cabin.

But having gone as far as the stout rope on either side would allow, the "Swan" was again pinned tightly in place by the poles, while the men on shore ran forward, and for the second time took a turn of their ropes round the trees.

Once more the poles were pulled up and the "Swan" rushed on until again checked by the ropes. And the same process was repeated until the rapids were past, and the river broadened out into a quiet expanse of water with a lazy current which bore the ponderous "Swan" only very slowly on her way.

The shore here was low lying, and would be marshy when the frost was all out of the earth. But as yet only the surface of the ground was melted, and in many sheltered places the snow still lay.

As the raft drifted easily along, Sergey cooked the dinner, which to-day consisted of cabbage soup, a dish of baked potatoes, and a big earthen pot of buckwheat porridge, with a lump of butter and a handful of salt in it.

When the lad saw how these men ate, he wondered how the raft could be provisioned for so long a voyage, even with such purchase of food as could be made at the villages or in the towns upon the river. But he had yet to learn that there were ways and means of obtaining food other than by buying. Indeed, that very evening Ivan called a halt, and they moored the "Swan" close in shore where the water was deep right up to the bank.

Here they got out fishing-tackle, and baiting their hooks with bits of salt herring, they fished over the raft side, while Sergey was told to take a hand-net and draw it through the shallows a little farther on.

In an hour or two the anglers had caught plenty of large fish to last several days, while Sergey had secured a bucketful of small, silvery fry, which were consigned at once to strong brine for future use. The larger fish were split open, cleaned, rubbed dry, and laid in salt for twelve hours, then taken up and spread out on the raft deck to dry.

The lesser kinds were cooked at once, and the boy learned how to fry them in water with plenty of pepper and salt. And he was surprised to find that when the frying-pan had been on the stove for about half an hour the water had turned into savoury gravy, and the fish floated in a light brown sea.

To vary the meals, Ivan, who had an old gun with him, now and then shot capercailzie and blackcock, and occasionally a hare, so that the raftsmen did not fare badly on the whole.

One dark night, the moon hidden, black clouds gathering, and a strong wind moaning among the riverside woods, Ivan decided that it would not be safe to proceed. So they secured the "Swan" to a big tree, cooked their supper, and lay down in the cabin as usual to sleep. In the morning the skipper had shot a hare, which was now hanging on a nail just inside the cabin door. The weather being milder than usual, the door of the cabin had been left open.

The men were soon asleep, and Sergey was just dropping off, when his quick ears caught an unusual sound. First a dull, soft thud on the raft deck, and then the cautious tread of light cushioned feet which paused in the open doorway. Wondering and somewhat alarmed, the boy sat up, and saw, just by the door, two great greeny-yellow eyes full of fierce fire. It was far too dark to make out any face or form, and fascinated and silent with fear, he could only stare back into the savage, hungry glare of this invisible intruder.

Out of Evil Good

SUDDENLY the ferocious gaze was veiled or turned aside, and Sergey heard a noise against the wall as of leaping, clawing, and tearing. This roused Ivan who, grasping his old gun which stood loaded in a corner, sprang to the doorway just in time to see a large grey, cat-like animal with tufted ears, springing off the raft on to the shore. He fired at the retreating robber, and the creature, with a yell of rage and pain, dropped and rolled over on the bank.

"Bring a light, child!" cried Ivan.

And Sergey hastily lighted the lantern and looked about to see where the skipper could be.

"Here! I am here!" called Ivan from the bank, and the lad noticed that the old man's voice sounded faint.

He sprang ashore, and found Ivan on his knees beside a huge lynx. The light of the lantern flashed on its glazing eyes, and sharp white teeth bared in an evil grin.

"Is the beast dead?" inquired Sergey.

"Yes, he is dead now, but he was not when I came after him here! And see what he has given me to remember him by!" And Ivan showed his right hand, which had a ragged deep wound across the back of it, while the sleeve of his shirt had been torn to shreds by the vicious claws of the big cat, and the flesh of the arm was scarred as though with barbed hooks.

"Oh, poor dear Ivan!" cried the boy. "How dreadfully it must hurt!"

"That is not what troubles me, little son," replied the old man, "but our voyage has not long begun, and there are many difficult bits of waterway before us. And I fear I shall be unable to use my hand for a long while."

"No, I fear you are right. But as we are coming to a town to-morrow, you must surely see a surgeon, and hear what he says."

"I will, child; thou sayest well! But now call my sons, for they must take this beast's skin. It is a good one, and we can sell it as soon as we got to the town of Krasnoi-Yablok."

Ivan's hand and arm were roughly swathed with a wet towel, Vassia and Sergey acting as dressers, while Kostia and Sasha skinned the lynx, and pegged the skin and feet out on the raft deck to dry in the wind.

Poor Ivan suffered much pain during the next few hours, but he made no complaint, and early next morning the raft was tied up close to the wharf of Krasnoi-Yablok. And Ivan, taking the boy with him, found his way to a hospital where a doctor and surgeon were attending to out-patients.

The latter carefully examined the skipper's injuries, which he said might become serious and even dangerous unless fully cleansed and dressed every day. He also warned Ivan that if he proceeded on his voyage, the chances were that he might have an illness which would prove fatal.

"But, Sir Doctor, I am in charge of the big 'Swan' raft," said Ivan. "My sons are willing, good lads, but as yet they are inexperienced. How can I trust them to take the raft on? Then too, here is this boy, for whom I am responsible; I promised to look after him, and I am loath to neglect my duty."

"When God makes impossible to us what we considered our duty," said the surgeon, with a grave smile, "should it not convince us that the path of duty lies elsewhere?"

Ivan looked up quickly and crossed himself devoutly.

"You are right, good Sir Doctor! The will of God be done!"

"If thou fearest that thy sons cannot safely take the raft farther without thee, skipper, why not all remain here until thy wounds are healed enough for thee to travel?"

"Nay, Sir Doctor, that cannot be, for our firm is under contract to get the rafts to their terminus in a given time, with a margin of only a few days. So that whether I stay or not, the 'Swan' must go."

"Then thou must settle matters as thou best can, good skipper. I can say no more." And the surgeon turned away to another patient.

"Ivan, listen!" said Sergey in low tones. "Since I go on the raft that will make a fourth hand; and Kostia is so clever and strong that he can surely be skipper for a time. Stay here and get cured, and then come on by train, and join the 'Swan' farther down."

Ivan thought silently for a minute. Then he said, "Yes, Sergey, little son, thy counsel is good. So be it!" And the matter was thus settled.

The "Swan" was not to start until late in the afternoon, so Sergey wandered about the town, looking in at shop-windows, and much interested in watching some of the showy vehicles and well-dressed people who had apparently driven in from surrounding estates.

Presently his whole attention was fixed upon a handsome couple who alighted from their open carriage in front of a jeweller's shop, near the door of which Sergey was standing.

"Come in here with me, Elena dear," said the gentleman. "We will try in some sort to replace thy losses. Those forest banditti near Glynoi-Liess took most of thine ornaments, did they not? Was ever carriage tour so disastrous before! Come in, my dove, and choose some for thyself."

"There was only one thing, Yevgen, that I have grieved and even wept over," replied the lady, "and that is the ruby ring thou gavest me on my wedding-day. I never cease to miss it. It was the most precious thing I had, and now I shall never see it again."

Thus spake the lady, and she was about to follow her husband into the shop, when a hand gently touched her arm, and a voice that trembled with earnestness said, "'This is the Lord's doing, and it is marvellous in our eyes!'

"Yes, most gracious Barrina, for you 'shall' see your jewel again! It is in safe hands; I know, and can tell you in whose! There can be no mistake! Is it not a great red stone with a heart of fire, and inside the gold ring is engraved,—

"'Yevgen to Elena'?"

"Yes! Yes! Those are the words, but child, child, who art thou?"

The Rescue

THE raft had started on her voyage again.

Sergey had told the lady Elena his story, or at least that part of it relating to his uncle Abram Kapoostin, and to the finding of the ring. He had given her Matvey's address, and had also himself written a few lines to the foreman, for the lady to enclose.

And then he bade an affectionate farewell to old Ivan, adding that he hoped to see him again very soon, when he should join the "Swan" later on.

But it was rather a depressed little company that started the raft again. Kostia, as skipper, felt the responsibility, and the other three missed the serene presence and quiet confidence of the old veteran whose every summer, for the last thirty years, had been spent in this kind of life.

But, after all, the thing could not be helped, and they must make the best of it. If each did his utmost, disaster might be averted, and at least they would have nothing with which to reproach themselves.

The first night they were all too much excited and too anxious to sleep. It was bright moonlight, and a calm, open waterway, so that there was no difficulty about going on, but the absence of the old skipper was enough to make them all doubly watchful. As the weather was not cold, the four spent the night on the raft deck. And as the day began to break, they too felt light at heart and happier about the voyage before them.

In the course of the morning they successfully worked their way down some rapids, and swung round a curve in the river just below, without coming into collision with any of the rocks that were scattered about. And after this they all gained confidence. It was evident that Kostia, had studied his father's methods to some purpose, and the rest of the crew began to trust him implicitly and obey orders without question.

When Sergey was not busy in the cabin, he lent a hand in managing the raft, and was quite pleased at being allowed to take his part in the work.

So for a week they drifted down the streams, borne on the spring flood. Once, while fishing, they caught an enormous sturgeon, but before they could secure it with net and spike, it had broken the strong line and vanished into the depths from which it had come.

One day, soon after they had passed a little waterside village, they spied, just ahead of the raft, what looked like a bundle of clothes in the water. They could see that it was gradually sinking, and presently it would be entirely submerged.

"What can that be?" said Kostia, who, pole in hand, was keeping the "Swan" from coming too near the bank. For the river here, though deep and rapid, was narrow.

Just then a little wave turned the bundle over, and a white face was upturned to the sky.

"Look! Look!" exclaimed Sasha. "It is a woman!"

"And we must get her out quickly," added Kostia. "Another minute and she will sink!"

So saying, he stepped to the edge of the raft on the right side.

"Sasha!" cried he. "Stand by with the boat-hook, but mind you only catch her clothes, Vassia, keep the raft steady, and steer a bit to the left. Sergey, go and see to the samovar and make some tea."

There were a few anxious moments while each member of the little company carried out the orders of the young skipper. Then Kostia stooped, and with strong arms lifted the insensible burden that Sasha drew in with his boat-hook.

"Take her into the cabin and slip off that sodden cloak, and try to get her warm," said Kostia. "I don't think she's dead. She does not look to me as though she had been very long in the water."

Vassia and Sergey bore the poor creature into the cabin, where the little stove was brightly burning. Here they laid her down, unhooked and drew away her thick cloak, chafed her hands, and poured a little warm tea between her pale lips. And, much to their delight, after about twenty minutes she began to revive, and presently she sat up and looked wonderingly about her.

"What is this?" she said faintly. "Where am I? Who are you?"

"Have no fear, Matushka!" said Vassia, kindly. "You are safe, and with friends. We are raftsmen, and but now we fished you up out of the water."

"The water? Ach, yes!" she replied in a weak voice. "He pushed me in!—like father like son!—and left me to drown. He was drunk—so drunk—and did not know what he was doing. And the water was deep, and I could not get back to the bank."

"And this man," said Vassia, "is he your husband?"

"My husband? Ach, no! Though, for the matter of that, he would doubtless have done the same. But this was my husband's father. When my husband deserted me, I kept house for my father-in-law. But there is no peace nor happiness to be had with any of the family. Assuredly God's curse rests on the Kapoostins root and branch."

"The Kapoostins?" exclaimed Sergey. "Said you the Kapoostins?"

"Yes; that they are all bad alike—thieves, drunkards, liars, cruel as death. But why art thou staring so, child? What is it to thee?"

"What is it to me, Matushka? Why, my uncle is a Kapoostin," said the boy, "and my mother was his sister—no, his half-sister."

"Is thine uncle's name Abram?"

"Yes, it is. How did you guess that?"

"Easily enough," she said indifferently, wringing the water out of her long brown hair. "Abram is my husband, who left me years ago."

"Why, none of us at Glynoi-Liess ever thought that he was married," said Sergey.

"No? Well, he can keep a secret when he likes; also to Abram Kapoostin a big lie is easier than the truth."

Sergey Meets His Aunt

JUST then Kostia came into the cabin.

"Vassia," said he, "go and help Sasha. I would speak with our passenger," and he smiled pleasantly. "I came," he added, as his young brother left the cabin, "to ask what we are to do with you, good Matushka. We are all men here, and have no place for a woman, so that we cannot offer to carry you far. Would you like us to stop now, and put you on shore?"

"I was just telling this boy and the young man you call Vassia," replied the woman, "that I had been pushed into deep water by my drunken father-in-law, for whom I had kept house and worked hard ever since my husband deserted me. And this lad tells me," she continued, with a little friendly nod at Sergey, "that my husband, Abram Kapoostin, is his uncle on the mother's side."

"So he is; I know that well!" replied Kostia. "Strange that you should turn out to be his wife! We have all believed him to be a single man. But now, Matushka, tell me what we shall do for you. For every moment we are getting farther away from your home. Do you wish to return to your father-in-law?"

"No! A thousand times no!" answered the woman.

"Then have you no friends anywhere near, to whom you could go?"

"There are some people I know in the next town you come to. I dare say I could get work there."

Kostia, thought a moment, then he said—

"The next town is Krasnoi-Puil; we get there about nine o'clock to-night. And as the weather is changing and storm threatens, we shall probably lie up in shelter of the quay all night."

"I have never had a Tiotia (aunt) before," said Sergey, "and I do wish, Kostia, that I could have kept her a little longer."

"Thou canst see her again, Sergey, on thy return journey," said Kostia. "Those cargo boats stop at all the towns on the river, and we will find out thy Tiotia if she will give us the name and address of her friends."

"And your name, what is it, my aunt?" asked the boy.

"I am Olga—Olga Kapoostin, and my friends are the Kierayoffs, at number 10 Black Street." And Kostia, wrote down names and address on a small slate hung against the cabin wall.

"So," said he, "we shall find you when we return this way in autumn, before the hard frosts begin. And now, good Matushka Olga, Sergey and I will leave thee to dry thy clothes at the stove, for it is ill work sitting in wet things. Come, child, I would give thee a lesson in steering the 'Swan.' For who knows how soon thou mayest be called to act as skipper!" And he laughed genially at his little joke.

That evening, after supper which Olga prepared—much to Sergey's satisfaction—aunt and nephew had the chance of a little quiet talk. He told her, in answer to questions—all about his uncle, her husband—and how, by the advice of the foreman, Matvey Philipitch, he had started on the raft to get right away from the wretched life he was leading, and the danger in which at last he had found himself. And Olga, in her turn, told him how Abram had left her years ago, taking with him their only child, a little girl called Dunia.

"He had no child at Glynoi-Liess; of that I am sure," said Sergey. "He gave us all to understand that he was a single man."

Down Olga's sad, worn face great tears ran.

"I never want to see him again," she said. "But oh, what would I not give to know what he has done with my dear little girl! Life is very hard, Sergey, for us poor folk. Living or dying, there is no help and no comfort."

"Ah, say not so, Tiotia mine!" cried the boy earnestly. "My parents taught me, and so also Matvey Philipitch, our foreman, that even when we feel ourselves most alone, most desolate, our Heavenly Father is watching over us, pitying us, loving us all the time. And, indeed, Tiotia dear, of late I have come to know what a very real thing is the Presence of God, and His great love shown in our Saviour Jesus Christ. And I love to read in the Gospels the wonderful things written there, and I, too, want to be the Lord's disciple, and to follow Him in all things. Have you a New Testament, Tiotia Olga?"

"No, I have never had one. I can read quite well, and write too, but have never had a book belonging to me."

"Well, look here," said the lad, drawing a little volume from his pocket. "Here is the Gospel of St. John, which I will give you for your own. You need not mind taking it, for I know it almost all by heart. And when you read therein of God's great love in sending His Son, and of the good deeds and sweet words of that Son, you will be helped and comforted as I have been."

"I promise thee, child, that I will diligently study this book."

"And you will pray for light and guidance to understand it, Tiotia?"

"I will indeed."

"And I will pray for you," said the boy.

"Do so, dear child! We ought to feel for each other, Sergey, for we have some experiences alike. I am fleeing from one Kapoostin—thou from another. My life has been in danger from my father-in-law, thine from his son."

"But now, thank God," said Sergey, "we have both given our enemies the slip. Your Kapoostin will think you drowned, and mine knows now that I am well beyond his reach. So, Tiotia dear, we will not despair any longer, but thank God and take courage."

That night the "Swan" reached Krasnoi-Puil and was moored to a ring in the stone quay.

And Olga parted from the three brothers and from Sergey with grateful acknowledgments, and betook herself to her friends in the town. While the raftsmen and their cook-boy, tired with the day's work, lay down early to sleep, so as to gain strength for the duties of the coming day.

A Meeting and a Warning

IT was just about a week after the adventure with Olga Kapoostin that on drifting down to the landing-stage of a riverside village late one afternoon, the young raftsmen were gladdened by the sight of a tall, grey-bearded man standing on the bank.

It was Ivan himself, healed of the lynx-bite, in excellent spirits, and very happy to see again his three sons, the little cook-boy, and his beloved "Swan."

"I arrived by train this morning," said he, "and came down to watch for you, as, from what I could hear, I judged that you had not yet passed down the river. And glad I am, my children, to set my old eyes upon you all once more, and find you safe and well. For which God be thanked." And the old man doffed his cap and bowed reverently.

The "Swan,"—reprovisioned for her further voyage,—was about to be unmoored, when a wharf watchman came up, and made a sign that he would speak with Ivan.

The old man, rope in hand, stepped ashore again.

"What is it, Gregori?" said he.

"Only this," replied the watchman in low tones. "Keep an eye on the banks as you go, skipper, and hold to mid-stream wherever you can. There has been a wood-famine hereabouts, and timber is scarce. A man called Yefraim Issakoff has a saw-mill not far from here, and of late it has been stopped quite often for want of tree stems to saw up. He is not over-particular as to how or where he gets his material, and he won't pay for anything that he can steal. But forewarned is forearmed. Thou art no novice, Skipper Ivan, and wilt know how to be careful."

"I thank thee, friend!" replied the old man. "It is kind of thee to give me this warning. I will keep mine eyes open, and no one shall take my 'Swan' from me if I can help it."

And after a few more words, the raft was started, but not before both Ivan and Kostia had noticed, standing on the bank at a short distance, a slim, sly-looking youth, with a greasy cap crushed down over his eyes. He had, moreover, a bright red scar across his left cheek, which made his face one to be remembered. But just as the raft began to glide down the stream, the young stranger disappeared, and the raftsmen drew their own conclusions as to his reasons for having watched them.

"Look here, Rebiata (children)," said Ivan, "that fellow, I am certain, is a spy in the hire of Issakoff of the saw-mill, farther down the river. He has taken stock of us, and now is gone to report us to his master. I have been warned that he may try in some way to get possession of the raft. But perhaps we can manage to slip through his hands without having to fight him; that is, my children, if for an hour or so, you are willing to work extra hard?"

"Try us, father! We shall not disappoint thee," said Kostia.

And Sasha, Vassia, and Sergey backed him up manfully.

"Well then," said the old man, "you see, all of you, how sluggish is the current here, and that the 'Swan' hardly seems to move. Of course, Issakoff is reckoning upon this, and can very well guess just how long it will take us, in an ordinary way, to reach some lonely, convenient place, where he and his fellows can, by trick or by force, make us give up the raft."

"Which we will not do!" muttered Kostia in his deep voice.

"Which most assuredly we will not do!" chimed in the others.

"Well, listen, children! One way in which I have known a raft stopped, is like this. A stout rope is stretched across a narrow part of the river, and just under the surface of the water, to catch that portion of the raft which is beneath, and arrest its progress. Then, while the raftsmen are wondering what is the matter, and getting in each other's way to find out, some men appear, as though accidentally, in a boat, and offer their help. While they are helping, the raft is drawn nearer and nearer to one of the banks, and here the rest of the timber robbers are ready waiting, and the raft is speedily taken to pieces and carried off."

"And what becomes of the raftsmen?" asked Sergey.

"Well, sometimes (to their shame be it said), they take a bribe and a bottle of vodki to keep the thing secret, and they make up a story for their master about having lost the raft in the rapids, or smashed it up on the rocks. And now and then their master never hears of either men or raft again, for they find it safer to disappear."

"Well, father," said Kostia, "since we are not such raftsmen as these, what is thy plan for us?"

"It is this," replied the skipper. "If Issakoff tries the rope trick, it will certainly be at the bend lower down, where the river narrows in the curve. But he will not expect us to be there for at least two hours more, the current being so slow. Now, children, supposing we could be there in one hour instead of double that time, we might get past that curve before he is ready for us. Afterwards the stream broadens out, and the land on each side is marshy, and the rope trick would be impossible."

"But how are we going to send the 'Swan' along thus quickly, father?" asked Sasha.

"My son, if two strong men towed it, one on either bank, we could more than double our pace."

"Good! Good! Batiuska! The two strong men shall be Sasha and myself!" cried Kostia.

"So be it, my children! But in case of the rope being stretched across early, it would be well for one of you to crouch in the front of the raft, with my big hunting-knife in his hand. Then the very instant the rope is reached, cut it through, and we go on at speed again without a minute's delay. Sergey, that task shall be thine!"

"How thankful I am that thou art skipper once more, father!" said Kostia, as the old man punted the raft to one bank and landed his eldest son, and then to the opposite side to set Sasha on shore. "I should never have known what to do."

"Are the towing-ropes firmly fastened in the rings, children?" cried the old man. "Pull, then, with all your might! And thou, little Sergey, sit here, and be ready with the knife."

Trapped

NO doubt Yefraim Issakoff of the saw-mill was wise enough to know that none of the usual modes of deception would be of any use with such an experienced skipper as old Ivan. And the spy had probably witnessed and duly informed his master that the clever raftsman had joined the "Swan" at the last stopping-place. So, putting their wicked heads together, Issakoff and his men devised another method which they thought was sure of success.

Meanwhile, the "Swan," towed at a fine pace by Kostia and Sasha—reached the narrow place where the river began to curve, and it found no rope stretched under water to bar their progress. The sturdy towing-men were to have been taken on board just before the curve was reached, as they would be needed for working the poles and steadying the raft amid the rush and swirl of the water. But just as the "Swan" was about to pick up first one, then another of the skipper's sons, there came an agonised scream from the river round the corner and out of sight of the raftsmen.

"Help! Help!" again yelled the voice. "I perish! I drown! Oh help!"

The screams diverted the attention of Kostia and Sasha, who, instead of trying to board the "Swan," pressed forward to the point of land that formed the river's curve.

Deprived of their help, it was all that Ivan, Vassia, and Sergey could do, to get the clumsy craft round the corner. And as it was, the dash of the water swept the "Swan" once sharply against the rock, and but for the old skipper's outstretched hand, Sergey would have been jerked off into the water.

As soon as the raft had rounded the curve, those on the deck, and Kostia and Sasha on opposite banks—could see a man struggling in the water. The two young men rushed forward, ready to plunge to his rescue, when suddenly the drowning man's left cheek came to view, and lo, across it flamed the scarlet mark. Also, at that very moment, it flashed upon all the witnesses, both on and off the raft, that the so-called drowning man was a fraud, and only pretending to be in distress.

"Hold, Sasha!" cried Kostia from the edge of the stream. "Do nothing! It is the spy! Father, take us on board quick! You need not stop, come near the bank, and I will leap, and then we will pick up Sasha from his side."

But almost before the words were out of his mouth, a strong noosed cord was thrown round him from behind, where the trees were thick, and the deepest shadows fell. And at the same moment Sasha too dropped to the ground on the bank, captured in the same manner by invisible enemies. In a trice the nooses were drawn taut round the shoulders and arms of the young men, and they were fastened to pine-trees. Others of the enemy caught the raft by means of boat-hooks strapped to long poles, and in spite of all that Ivan, Vassia, and Sergey could do, the "Swan" was pulled to shore and made fast, and the old skipper and his son were bound just as Kostia and Sasha had been.

In the struggle and confusion, however, Sergey was overlooked, and so managed to slip out of sight and hide. But as soon as the marauding party began to move away with their prisoners, the boy followed, hiding and dodging among the trees, rightly judging that as he was free, he might perhaps be of service later. The raft could not well be broken up before morning, so it was safe enough at the bank.

Sergey, keeping the raiders and their four prisoners well in sight, followed through the wood, and from the thick shelter of the undergrowth watched the whole party emerge into a wide open space where stood the saw-mill, and near it a house and a shed. He noticed that Sasha was one of the prisoners, so that the men who secured him on the other bank of the river, must have punted him across. And the lad wondered at the care and fore-thought spent in making their wicked plan so successful. He saw the prisoners thrust into the shed, and a heavy bolt shot home to keep them safe. All the raiders went into the house, and Sergey noticed how one room on the ground-floor was lighted up just after the men entered.

After a while, he ventured to come out from his hiding-place, and peep in through the uncurtained window, which, though covered nearly all over with dust and dirt, had one clean corner which gave him a good view. He saw the whole party gathered round a table on which were two huge bottles of vodki and a number of glasses. At the head of the table sat a middle-aged, wicked-looking man, to whom the rest seemed to defer.

This, Sergey was sure, must be Yefraim Issakoff, the owner of the saw-mill.

The men were a rough, wild set of follows, just the sort to carry out the bidding of such a master. In these lonely places all kinds of crimes are committed and go unpunished, for the police are few, even in the towns, and are so wretchedly paid that they are always open to a bribe from any malefactor who will make it worth while for them to shut their official eyes.

Meanwhile, the only member of the "Swan's" crew at liberty, and fully realising how much might depend upon his knowing the exact position of affairs, Sergey watched and listened intently, seeing and hearing all that passed.

"Well, my men," roared Issakoff, "we've made a grand haul to-night!"

"Ay, it was a fine bit of work, it was," responded the spy; "especially my drowning."

"Thou hast always some compliment to pay thyself, young Scratch-face!" said another of the men. "By my faith, if thou—"

"I suppose that barn is safe?" interrupted Issakoff.

"Ay, we could keep a wild bull in it," replied a big burly man who was shaggy enough for a bear. "It's as strong as a prison."

"'What became of that boy?" inquired Issakoff. "There 'was' a boy, wasn't there?"

At this mention of himself, "that boy" cowered to the earth for a minute or two, but he could hear the reply in the spy's voice.

"Yes, I think there was a boy, but he doesn't count; he was quite small, and I dare say he was drowned."

"We'll hope so," rejoined Issakoff. "Now, brothers, pass the bottles round. No need to keep sober to-night. The raft is ours, the men are safe, and if there is any fuss to-morrow, I shall lodge information in the next town and say I caught them carrying off my property, and so I took their raft for compensation. So now, my children, let us drink to the song of the dying 'Swan,' and to-morrow the 'Swan' will be dead!" And Yefraim Issakoff lifted his glass high in air, and laughed loud and long.

Loosing the Bonds

SERGEY waited and watched until, overcome with vodki fumes, all the men were lying round helpless, and many of them snoring. Not till then did he feel it safe to give up his anxious peering in at the window and steal down to the shed. Very slowly and softly he drew back the bolt, making no noise.

"It is I—Sergey," he whispered. "Here is my knife! Let me cut your bonds. Be very still and come quickly down to the bank. The 'Swan' is there quite safe."

Chafing their stiff and swollen arms, the four men stole out of the shed and followed the lad down to the river. There was the "Swan" untouched. So secure in his possession of it had Issakoff felt himself that he had not removed even a single thing from the cabin.

In fear and trembling, in such haste as they could combine with absence of noise, they got on board, and loosed the raft from her moorings. And as they pushed off with the boat-hook into mid-stream, the old skipper sobbed like a child, and his sons cried too for company.

But Sergey was too happy for tears; he was overcome with thankfulness. Kneeling down bareheaded on the deck, he poured out his prayer out of a full, glad heart.

"O dear, kind Lord," he said, "it is quite true what we have heard—that

Thou deliverest those that look unto Thee; for lo, Thou hast delivered

us as Thou didst Thy servant Daniel in the lion's den, and the three

Hebrew youths in the fiery furnace, and St. Peter in the prison, and

David from the giant. And now, good God, we thank and bless Thee, that

here we are before Thee, under Thine open sky, and on our dear raft

once more. Watch over us still, we pray; protect us all the way, and

teach us to love Thee better and to trust Thee wholly. Forgive us all

our sins, and make us truly Thy children, for Christ's sake."

"Amen," said four husky men's voices.

And the lad, opening his eyes, saw Ivan and his sons all reverently kneeling, and realised that it had been given him to voice a prayer for them all.

"And now," said Sergey, "I am sure you must be needing food, as I am myself. So I go to prepare supper," and he vanished into the cabin.

The next place they came to was a large straggling village, and here they bought butter and vegetables, and Ivan called on the chief man there, related the adventure of the night before, and begged him to telegraph back at once to the town so that the authorities should take measures to prevent such a thing happening again.

"For," he added, "we have other rafts following shortly, and unless safety be assured to us, we must make formal complaint at the capital, and have proper inquiry, and Issakoff and his men put under arrest."

At this, the elder of the village promised to attend to everything, and made a note of the name and the address of the owner of the saw-mill.

And now the raft was once more ready to start, and Kostia was just going to push off when a woman, accompanied by a girl of about Sergey's age, hurried down to the water's edge.

"Stop a minute—only a minute!" she cried. "I want to ask a question."

"Quick, then, Matushka," said Ivan; "we must be off at once."

"I will not keep thee long," pleaded the stranger. "Tell me, please, whence comes thy raft?"

"From far up the river—a place in the forest called Glynoi-Liess," replied Ivan.

"Hast thou," asked the woman, "ever met thereabouts a man called Abram Kapoostin?"

"Again that abhorred name!" rapped out the old man impatiently. "Of course, yes, my good woman, I know him—more's the pity! For there are some kinds of knowledge that we should be better without."

"Hear my reason for asking," said the woman. "Years ago now a man came to this village one day with a child—his little daughter."

At this, Sergey eagerly turned his head and listened.

"I had a small shop in the village," the woman went on, "and he came in and bought a loaf and some kringles on a string, and then said, 'Good Matushka, might I leave my little girl with you just while I make a call or two on business? I will return in an hour.'

"'Thou must tell me thy name first,' I said.

"'I am Abram Kapoostin,' he answered, 'and this is my little daughter, Dunia. My wife is dead, and I am going to try and make a new home somewhere up the river.'

"'Very well,' I said, 'leave the child then, if thou wilt, but leave also that bundle thou hast on thine arm. It will be safe here, and would only cumber thee in thy visits.'

"So, very unwillingly, and with a hateful look on his ugly face, he handed me the bundle, after first taking from it some things and stuffing them into his pockets. Then, with not so much as a 'thank you,' he went his way, and from that day to this I have never seen him again. Believe me, this is the truth!"

"Believe thee? Of course!" cried Ivan. "I know the man well enough, and he is a walking lie. Is this his child? A nice girl, and, thank God, not like her father in face!"

"I love her and would not part from her," said the woman, "but my health has failed, and I can no longer work for our living. A married sister would have me live with her, but she will not have Dunia, and I know not what to do with her."

"But," said Ivan, "thou wouldst not send her back to her father, surely?"

"And, besides," put in Kostia, "he is no longer at Glynoi-Liess, and we know not where he is."

"Why not take her to her mother?" spoke up Sergey. "She is not so very far off, only at Krasnoi-Puil with the Kierayoffs, Number 10 Black Street."

The old skipper turned round in astonishment. "And pray, whence hast thou learnt all this, Sergey?" said he.

"Ach, Batiuska," said Kostia, "all this happened while I was skipper. We will tell thee about it presently."

"Good! Then now we can start. Do thou, good Matushka, take the girl to her mother at Krasnoi-Puil, so shall all be well. And now, farewell!"

The rest of the voyage was through more civilised regions, and no serious mishaps befell the "Swan." Once the raft was nearly run down by a steamer. And on another occasion, while moored to the bank, she was suddenly boarded for a moment by a runaway horse. But it only touched its flying hoofs to the deck, and splashed wildly into the water on the other side, and as the crew was in the cabin at supper, no one was hurt.

The remainder of the journey along the waterway was tedious and uninteresting, and the little party of five was glad enough to reach their destination—one of the larger cities—and to consign their raft to its rightful owner. As soon as they had done this, they began to make tracks for home, and left all together by the first cargo boat that was going a few miles upstream.

Homeward Bound

NOTHING of any moment happened to the raftsmen and their cook-boy till they reached Krasnoi-Puil, where they had landed Olga Kapoostin. There they would have a day to wait before a cargo boat called that would take them up the stream.

So while the young men called on their friends, Ivan and Sergey went exploring in search of Number 10, Black Street. And as they neared the house, they saw, standing out in a small garden, and washing clothes in a huge tub, Olga Kapoostin, looking very well and happy, while near her, wringing out soapsuds over another tub, previous to rinsing in the river, was a pretty girl of thirteen, her short flaxen hair curling all over her little head like a boy's.

"Ach, Tiotia! Tiotia Olga!" cried Sergey, running and throwing his arms round his Aunt's neck.

"And here, too, dear boy, is thy cousin Dunia," said Olga. "It is thanks to thee, they tell me, that I have my girl again. Thou hast no sister, Sergey, let Dunia be one to thee! For are not cousins next best to sisters?"

Then while the children roamed away together, Olga told old Ivan her story. And he vowed, in his righteous indignation, that when he reached home, Abram Kapoostin should not go unpunished.

Just as they were parting, Olga said, "As thou goest up the river, kind Ivan, alighting here and there, wilt thou, in thy goodness, ask those whom thou dost meet, if they can tell thee where is my young brother Appolon—Appolon Gorlieff? He was footman when last I heard of him, in a nobleman's house on a big estate farther up the river. But I have no news of him for a long time."

Sergey, near enough now to hear the name, listened intently. But, for the sake of his promise to the chief of the robbers, he dare not ask a question which might involve his telling the story of his visit to the bandits' stronghold that night.

"I cannot but fear," said Olga, "that he may have got into bad company, or been ill in hospital. I dread lest something untoward should have befallen him."

"I will make all possible inquiry, and will let thee know," said Ivan. "The footmen of the great houses are well known in the towns near, as they are often sent thither on errands."

"The gentleman and lady whose servant he was," replied Olga, "are Count Yevgen Orloffsky, and his wife, the lady Elena."

Here was another connecting-link in the chain of Sergey's strange story!

His hitherto uneventful life in the village had merged in a series of experiences fitting into one another like those little boxes he had often seen—a dozen in a set of graduated sizes, cleverly made by some of the peasant toy-makers in villages not far from his home.

Before the returning crew of the "Swan" left Krasnoi-Puil, another of their own rafts, on its way down the river, called there for provisions, and brought astonishing news.

Abram Kapoostin had been caught breaking into a house some twenty versts from Glynoi-Liess. And he and two others had been arrested and sent in chains to one of the larger towns for trial.

"Matvey Philipitch told him," said Sergey, "that God would one day hinder him in his wicked work, and see—it is turning out even as he said! But oh, I am glad and thankful that he will not be in Glynoi-Liess when I get there. The air will be purer for his absence. But didst thou learn, Ivan, who my uncle's prison companions were?"

"One was a big, fine-looking fellow, they tell me," replied the skipper; "he was more educated than most, and should have known better. He was outdoor steward; a sort of under-manager on a large estate, and instead of protecting his master's property, he robbed him and others too."

"Without doubt my captain of the bandits!" said Sergey to himself. "I only hope Appolon is not one of the three taken, or poor Tiotia Olga will break her heart."

But he kept silence about these matters now, as he had done hitherto, for one of the lessons the boy had learned was to hold his tongue.

When the returning crew of the "Swan" arrived at the big town where Sergey had met Count Yevgen and his lady, the boy would have liked to walk about and look round as he had done before. But the little steamer was going on in an hour's time, so Ivan and the rest of the crew contented themselves with talking to their acquaintances on the quay.

But Sergey, knowing nobody, was standing apart, when some one came up behind and said—

"Canst thou tell me, boy, how soon this steamer leaves? I have to fetch a box of goods from a store in the town, and I would know if there be time to get it."

Sergey turned, the answer upon his lips, and found himself face to face with a young man whose eyes and forehead and voice he remembered at once. But this face was beardless; surely it had worn a beard once.

"Can it be thou, Appolon?" he said.

"And thou art the little Sergey!"

Then in a frightened whisper the young man added: "For God's sake, betray me not! Since that night we both know of, I have repented and have forsaken my evil ways. That night when I was witness of thy courage, I said to myself, 'If God can give a mere child grace to refuse to be wicked, He can surely give it also to a man, if that man asks Him.'"

"And did the man ask Him?"

"He did, and was heard, and strength came. I left the company there and then, and never returned."

Then, leaving the boy glad at heart, he went to get the box, and returning, heard all about his sister, and promised to write to her.

From place to place, sometimes tramping for a dozen versts or more, at others travelling by barge or cargo steamer, the crew went homeward, and on arrival at Glynoi-Liess the whole party received the warmest of welcomes.

And best of all was it to Sergey to be told by Matvey Philipitch and his wife Christina that from that time they would be his parents, and their home should be his.

And when he told them the story of his adventures during his life on the raft, Matvey said, "Little son, many lessons, doubtless, hast thou learnt in these last months, but methinks the greatest and most precious of all are these: 'First—A thing is always possible if it be duty;' and 'secondly—Out of evil God will surely bring good to all who trust in Him.'"

Printed in Great Britain by Hazell, Watson & Viney, Ld.

London and Aylesbury.