Title: Too old to fly

Author: Ivan March

Release date: August 2, 2025 [eBook #76617]

Language: English

Original publication: New York, NY: Street & Smith Corporation, 1929

Credits: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

Sergeant Galladay learned to shoot a machine gun “from the rear end of a mule.” That was the old marine corps phrase to describe a gunner who learned all the tricks of his trade in the jungles and brush of “spiggoty land.”

Quite obviously such a leatherneck was not to be mentioned in the same breath with a fellow who acquired his knowledge of projectory, windage, recoil and assemblage, safe in the lecture room or gun pits of Paris Island.

The grammar-school education of Sergeant Horatio Galladay—then Private Galladay—took place in the Spanish-American War, and his textbook was a many-barreled Gatling gun he turned with a crank. Given plenty of ammunition and a large enough target, Private Galladay caused plenty of damage while he learned. His high-school course was in the Philippines, followed by a college degree of D. B. W.—Doctor of Bushwhacking.

For a diploma he received the navy cross for distinguished service, his sergeant’s chevrons and a letter from the secretary of the navy, complimenting him upon the diligence with which he had pursued his studies—and the enemy.

During that island campaign Sergeant Galladay served as the unwilling carving block for an artistically inclined Moro chieftain. His machine gun had jammed and the entire contents of his army model .38 Colt failed to stop the maddened charge of the brown man, who danced forward, his black eyes fixed gleefully on Galladay’s midriff, his bolo knife cutting anticipatory patterns in the air.

Silent as the death which he was facing, Sergeant Galladay dropped the Moro at last with a straight right to the jaw, but in the meantime the tribesman had carved his initials several times on Horatio Galladay’s anatomy. The men of Company B found him weak in his own blood but still cursing the jammed machine gun which he loved with a blaspheming love.

For fear that Sergeant Galladay might forget what he had already learned about the tricks of machine guns and to keep him abreast of the times in his fine art, a philanthropic government at Washington managed to find perennial fracases in various far-flung corners of the world where a good machine gunner was worth his weight in gold.

He chased cacos through the jungles and up the mountains of Haiti; he crooned to his gun in San Domingo, Nicaragua, China and other places not so well marked on the map. And he acquired, during this post-graduate work, a marvelous knowledge of malaria fever, native liquor and man-eating insects. In addition, during the occupation of Vera Cruz, he earned two bullet wounds through his left leg, which ached abominably in wet weather, and a flattened nose from the gentle caress of a mule’s right hind foot.

The entrance of the United States in the World War found the battle-scarred veteran eligible for a professorship in his favorite subject. Some one in Washington remembered the sergeant, thought twice of his stocky, erect figure, his legs bowed by the weight of the guns he had carried, his cold, blue eyes which had taken on the glint of the metal barrels he had squinted down so often, thought once more of all the knowledge and practical experience in that grizzled head. “Just the man to teach the fine art of machine gunnery to the marine ‘boots,’” General Somebody decided. Forthwise, Sergeant Horatio Galladay was ordered to Paris Island.

Sergeant Galladay went. But he didn’t stay. Thirty minutes after his arrival he marched up to the commanding officer’s desk and snapped to attention, his square jaw thrust forward belligerently and his eyes firing two hundred shots a minute.

“Hello, ‘Hod’!” greeted the C. O., grinning his pleasure at seeing the sergeant again. As a matter of past history, there had been a torrid day in the Philippines when Sergeant Galladay’s bullet-spitting music box had saved the C. O.’s little company from being wiped off the earth. “Hello, Sergeant Galladay!” he added more severely, for he saw trouble in the gunner’s cold eyes.

“’Lo, colonel!” grunted Galladay.

“Well, well, what’s the trouble now?” And the C. O. began to turn over the foot-high stack of paper work. “Suppose you want to go straight to France, eh? Be shooting up the German high command by to-morrow night, eh? Just like the rest of——”

“Right!” barked Sergeant Galladay.

“Listen, sergeant,” reasoned the C. O. placatingly, “we’ve got something better than that for you. Sure! We’re going to give you a commission. Yes, sir, a commission! And put you in charge of machine-gun instruction. How’s that, old-timer? A commission and——”

“Commission be damned!” burred Hod Galladay. “Begging your pardon, colonel. Look here, sir. I’ve been fooling around in these half-pint spigotty wars for twenty-five years. Now when a real war comes along you try to give me a trick commission and shelve me away ‘training boots’! Is it fair? No, it ain’t! Now get this! My hitch in this man’s service is up in six weeks. Six weeks! And if I don’t get a promise of action pronto I’ll quit. Quit cold, unless I join up with them Germans, maybe.”

The C. O. reached for his pipe and waved his hands helplessly. He sensed the utter futility of argument with the old leatherneck.

“All right, all right, you old fire-eater,” he said soothingly. “We’ll just forget that teaching detail. Name your poison. What do you want to do?”

“I want to sign up with the aviation. I hear they’re forming a marine aviation outfit. I want to fly.”

“What?” The commanding officer’s jaw dropped open, the pipe fell from his mouth. He stared at Sergeant Galladay as if the latter were an escaped lunatic.

“Good Lord, Galladay, you can’t sign up with the air service! Why, man, that’s a young fellow’s outfit—got to have a bunch of crazy kids. We’re setting the age limit at thirty and we’d rather have ’em around twenty. Say, how old are you, anyway?”

“Forty-three,” lied Sergeant Galladay manfully.

“Forty-three! Good Lord, that’s only thirteen years over the limit. Guess you better forget that fool aviation idea of yours, sergeant.”

“Quit, then!” the leatherneck said.

The commanding officer shook his head despairingly. These old-timers were damnably set in their ways. If they got an idea into their heads you couldn’t budge it—not with a three-inch field piece. The commanding officer reached for a memo pad.

“Very well then, Galladay,” he sighed. “I’ll recommend that you be attached to this new air-force group. They’ll need some one to teach machine gunnery. But get this! They’ll assign you to that job and keep you on the ground for the duration of the war. Serve you right, too.”

“Keep me on the ground?” grinned Sergeant Galladay. “Sure they will—like hell! Once I get set with that outfit I’ll be flying every ship they’ve got!” He snorted contemptuously. “Too old to fly! Say, colonel, just give you and me twenty men from the old C Company and we could swab up a whole regiment of these here young whipper-snappers they’re recruiting nowadays.”

Sergeant Horatio Galladay thrust his head out of the door of the armory shack of the —th Marine Aviation Group, Ardres, France, just as a bombing squadron, returning from a daylight raid on the submarine base at Ostend, swept downward over the row of French poplars which lined the north end of the drome.

“Four, five, six, seven,” Sergeant Galladay counted the returning planes as their wheels touched the field. “All present and accounted for. That’s good.”

For eighteen months now he had watched the planes—not these particular planes, but ships varying from the old Canadian-rigged, Hispano-powered J. N. training planes and tricky, tail-heavy “Tommies” to these Liberty-motored De Haviland bombers; and always he got the same thrill, the same unsatisfied longing to fly when they took off, the same relief when they returned.

He hadn’t flown over the enemy lines himself yet, but that wasn’t his fault. He had begged, pleaded, cursed, pulled wires—and all he got for it was a laugh and a glance at his grizzled head, a glance which said: “Too old to fly, old-timer—a young man’s game.” So he remained in charge of the noncommissioned machine gunners and the armory shop. True, by dint of threats and bribery he had managed to get a few joy rides and three of the pilots had even allowed him to handle the stick a bit. But when he requested permission to solo—

Sergeant Galladay sighed as he turned back into the shack. He supposed he was too old—too cautious. It took the devil-may-care young-uns for air work. He looked very sad as he placed the Lewis gun he had been repairing back into its wooden case. For a moment or two he caressed the weapon absently, staring into space. Suddenly his shoulders went back, he pulled his fore-and-aft hat over the bald spot on his head and started for the door. His eyes glinted his determination. He’d try once more.

The De Havilands were taxiing up to the camouflaged hangars which lined the field. Motors roared in staccato bursts. Lieutenant “Buck” Weaver, the flight leader, a blond, wind-tanned giant, brought his plane up to No. 1 hangar with a roar, cut the throttle and leaped out of the cockpit, leaving the motor idling. He felt a hand on his arm and turned.

“Well, hello, Hod, old-timer!” he greeted Sergeant Galladay affectionately.

“What luck?” demanded the sergeant.

“Great! Six direct hits. And we picked off two Fokkers on the way home! Not bad, eh, Dad?”

Sergeant Galladay scowled. He had helped to whip the tall, gawky recruit into a real soldier and now here he was with a commission, calling an old-timer “Dad”! Well, at that, the young pilot was a son of whom any real dad might be proud.

“Yeah, Buck, suppose you’ll personally claim both them Boches,” Galladay said with heavy sarcasm. “And about five of them direct hits.” Suddenly his manner changed. He became mild, ingratiating, pleading. “Say, when you going to give me that ride over the lines you promised?”

Lieutenant Weaver flashed a row of strong, white teeth; his young eyes smiled banteringly. “Any time, old-timer. How about this afternoon? We’ll get ‘Hap’ Johnston to go along with us in his bus for company. Suit you?”

Little chills of excitement ran up and down Sergeant Galladay’s spine; he could feel the hair prickle at the back of his neck. At last he was going to fly over the lines! With an effort he controlled himself; his face was as expressionless as a wooden image.

“Suits me fine,” he agreed. “I’ll be ready. What time?”

“Oh, about four. We’ll take a little joy ride up to Nieuport and back. You’ll learn what antiaircraft is like, anyway. I want to be back early. Got a date for six thirty.”

“You and your dates!” scoffed Galladay, for something to say.

Impulsively Buck Weaver took the older man’s arm and led him toward headquarters. Buck was overflowing with sentiment; he must tell some one, and it couldn’t be his flying comrades for they’d laugh at him, kid him unmercifully. Yes, the thrill of the successful raid had increased his excitement and happiness; he must tell someone his secret or burst. Why not the tight-lipped old marine sergeant, Dad Galladay?

“You know any of the WAAC femmes, Dad?” he asked in a low voice as he strode along.

Galladay nodded his grizzled head; his mind was on the promised flight and he hadn’t half heard the flyer’s question.

“Then mebbe you know Miss Childers?” Buck primed, and there was a suggestion of holy worship in his tone. “Ruth Childers?”

The old sergeant shook his head. He was hoping that they’d meet eight or ten or twelve Boche planes that afternoon. He’d show ’em some plain and fancy shooting.

“Well, you got to meet her,” Buck announced gravely. “She’s the most wonderful girl in the world, bar none. Ask me if she’s wonderful!”

“I’ll let ’em have it like they never got it before,” Dad Galladay muttered.

“We’re half engaged,” the handsome young lieutenant admitted in a whisper.

“Which half?” asked Galladay, without thinking what he said.

“Well, it’s like this,” Buck Weaver confessed naively. “She’ll marry me if I give up flying. Marry me.” He repeated the words and stuttered over them. “Only, of course, I can’t give up flying. Not now, anyway. So we’re half engaged and... Holy mackerel! Here she comes to meet me! Ask me, Dad, ask me, isn’t she the neatest, prettiest, nicest—— Ruth, this is Sergeant Galladay. Dad Galladay. Miss Childers, Dad.”

Dad Galladay received a faint impression of a mass of golden-yellow hair escaping from a rakish little cap, of big blue eyes, a pink-and-white complexion and a smiling little mouth. He realized dimly that in front of him stood a girl with her hand outstretched, a very attractive girl, trim and graceful in her neat, brown uniform. Very faintly, too, he understood that the girl’s blue eyes were watching Buck Weaver with love akin to worship and her lips were smiling at the big, blond giant with marvelous tenderness. Sergeant Galladay took the little hand that was proffered him.

“I’ll betcha I’ll get eight out of them ten Boche,” Dad promised inanely.

Too late Buck Weaver kicked the sergeant’s ankle. The girl’s blue eyes had widened with sudden perturbation.

“What’d you say?” she asked, and when the old sergeant stammered incoherently, she turned full on Weaver. “Allington,” she pleaded with half a sob in her voice, “you aren’t going to fly again to-day, are you? Oh, you won’t, will you? Not when you don’t have to. You don’t know how I worry when you’re out. It makes me almost sick and——”

“Oh, shoot!” scoffed Buck Weaver. “I just promised Dad a little joy ride, that’s all. Just up to Nieuport and back. We won’t make any contacts. Sure we won’t. I just want to show him how the antiaircraft work. He’s been hounding me to death for four months now and I got to do it.”

“But——” protested the girl.

“I got to keep my promise, haven’t I?” Buck Weaver insisted. “You needn’t worry. Honest, we’ll scoot home at the first sign of Boche. Honest, I will, Ruth.”

Ruth Childers had taken the hands of the big aviator and was staring up into his bronzed face.

“All right, Buck,” she said. “This time.”

Buck flashed a grin over his shoulder to old Dad Galladay who stood there awkwardly enough, shifting from one foot to the other, still thinking about the eight Boche planes he was going to bring down out of the ten he was already fighting in his imagination.

“See you at four, Dad,” Buck announced. “Toute suite.”

“Sure!” called Galladay, and as an afterthought: “Say, Miss Childers, you needn’t worry about Buck this afternoon. I’ll bring him home O. K. Sure I will.”

The two young people strolled away arm in arm, leaving the old marine sergeant standing there and staring after them. But he wasn’t wondering about young love at all; in his mind he was already pressing the trigger of a Lewis machine gun, soaring high in the air and engaging ten huge enemy planes at once.

Four o’clock found the planes of Buck Weaver and Hap Johnston gassed, oiled, ready and on the line. Sergeant Galladay had seen to it that the motors were tuned up like Swiss watches. For the last hour the old war dog, dressed in a borrowed flying suit which was considerably too big for him, had been adjusting and readjusting the double Lewises in the gunner’s cockpit of plane No. 1. Meantime Corporal O’Hara seated in the other plane, was offering unheeded advice to the old-timer.

“If we run into any Boche don’t get buck fever like I did first time, sergeant!” he shouted. “Yes, sir, I sat there and couldn’t fire a single shot. Not for the life of me. Now don’t get that way, sergeant. Just swing on ’em like you were shooting ducks. Throw the tracers at ’em and keep pouring ’em in.”

“Say, who learned you how to shoot, kid?” Sergeant Galladay snorted contemptuously. “Didn’t I have to show you which end of a gun the bullets came from? Kid, I was shooting off’n the rear end of a mule while you was cutting teeth. Now you know it all just because you happened to knock down a Boche plane or two! Me get buck fever! Say, I expect to get eight out of ten, at least!”

O’Hara grinned, “All right, old-timer! Only better men than you have had it and—— Here comes our two guys. Say, them two babies are the best pilots in the outfit, sergeant. The Heinies know it, too, and if they weren’t scared clean out of the air they’d be on our tails this afternoon.”

Galladay was deaf to everything except the beating of his own heart. He shouted to a mechanic to “twist her tail” and the motor was running long before Buck Weaver reached the plane.

“Feel a bit shaky, dad?” the pilot asked as he climbed into the cockpit. “Most everybody does the first trip over.”

Sergeant Galladay shook his head. “Not a bit shaky, son,” he lied. “Say, listen, this airplane stuff is tame compared with the old days.”

Pilot Weaver grinned and pushed open the throttle until the tachometer registered fourteen hundred revolutions, listened intently to the motor, wiggle-waggled his controls and nodded his satisfaction.

“All right! Pull the blocks!”

Two waiting mechanics removed the heavy wooden blocks in front of the wheels. Weaver taxied to the middle of the field, brought the plane to the wind and gave her the gun. The Liberty motor roared, spitting fire from the exhaust manifolds; slowly the big De Haviland crept forward, gathered speed, skimmed over the ground, bumped gently twice, and leaped into the air.

Around the field the plane circled until the hangars became little camouflaged ant hills and the row of poplars behind them were like miniature nursery trees. Still climbing, Weaver swung his plane toward the coast. Sergeant Galladay could see the English Channel and the port of Calais with the shipping in the harbor like little toy boats. Then he noticed that Weaver had turned his head and was grinning at him. The machine gunner, exultant as a viking in the prow of a pirate ship, waved his hand and grinned back.

Weaver continued to hold the plane’s nose up, and the altimeter on the instrument board indicated twelve thousand feet when she passed over Dunkirk. Beyond that point lay the skeleton houses of the ruined town of Furnes, and the blackened scar stretching to the eastern horizon which was the Flanders front.

Sergeant Galladay peered over the side of the cockpit and scrutinized the ruined landscape below with awed eyes. By glory, they’d made a mess of it down there, he thought. A hell of a way to fight a war—men up to their necks in mud in those zigzagged lines of trenches. Day by day, month by month, hot as hell, cold as Iceland, penned up like rats in their holes, pecking at each other with machine guns and rifles, throwing hand grenades, waiting for a big shell with the right number to blow up a whole squad.

Sergeant Galladay recalled the old, wild, free days in the Philippines—Haiti—Cuba. Fever, snakes, and big tropical ticks there were in plenty—and action, too. But it had been every man for himself there and lots of territory to cover—not this rat-trap warfare.

The Germans weren’t paying any attention to the American planes at all. Where the devil was the Archie—the German antiaircraft?

Whomp! Woof! Woof!

As if in answer to his wonder the German batteries surrounding the town of Nieuport sent up a welcoming barrage of high explosive shells—little clouds of black, dirty smoke which barked at the planes like ferocious dogs. Chains of flaming “onions” drifted upward lazily toward the two allied planes. Sergeant Galladay’s heart leaped wildly. He was actually over the lines now, really flying above German territory. It was the realization of a dream, a realization which found him strangely shaken and breathless.

Weaver turned and grinned again, then signaled to Johnston who was in their rear. The two planes headed back toward the allied lines.

The antiaircraft was still banging away at them, but there didn’t seem to be a German plane in the sky. Oddly enough, Sergeant Galladay, for all his former anticipation and bloodthirsty threats, wasn’t sorry. It was a lot different away up there in the sky than it had been in the good old days down on terra firma with trees to hide behind and plenty of ammunition and a good machine gun set up on a tripod. Down there he was in his element; sky-high, he felt impotent, vulnerable, old. His mind drifted back to that day years ago when he had had the battle with the Moro chieftain and again to the storming of Vera Cruz. There a man had a chance and——

Zip—zip—zip!

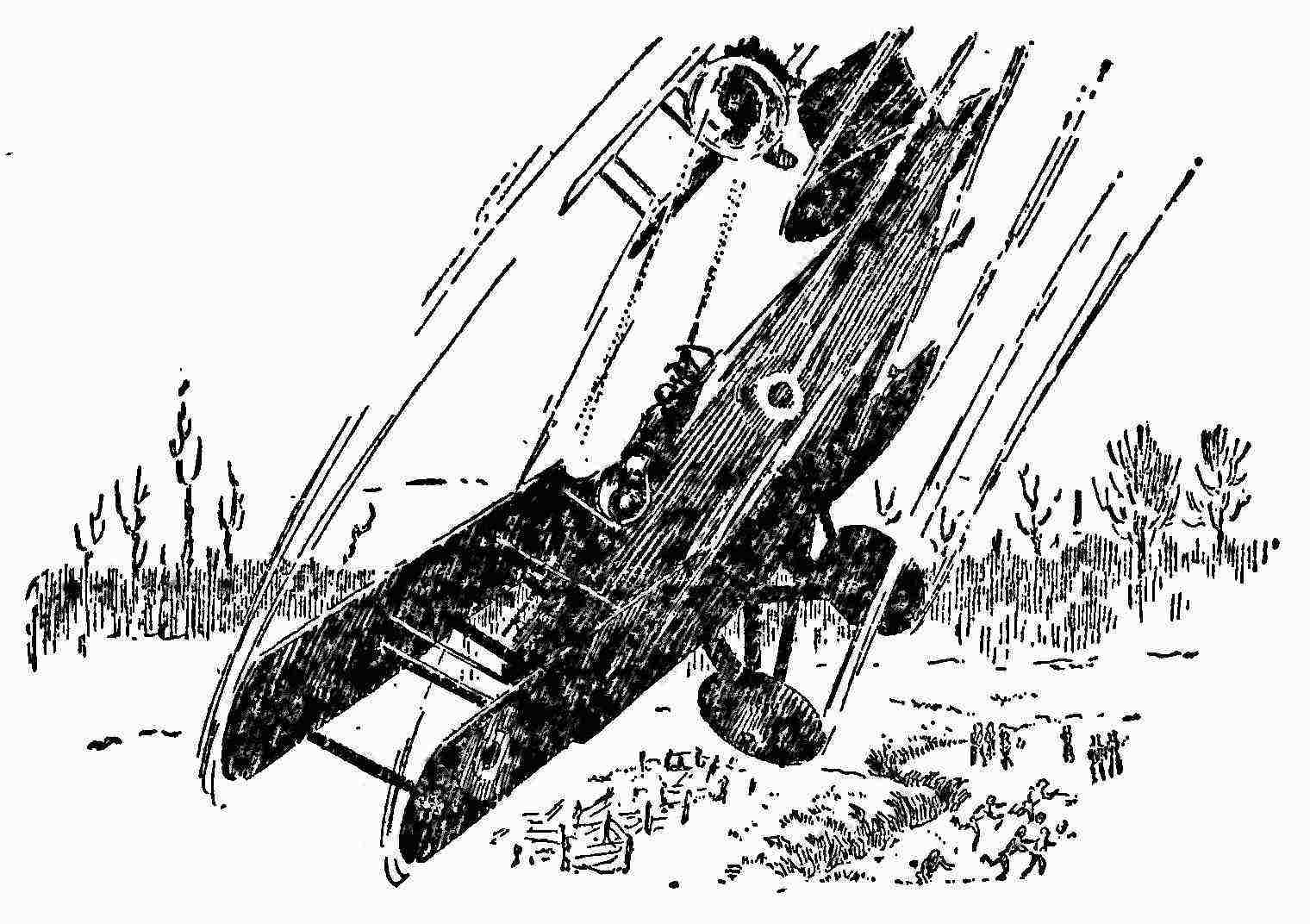

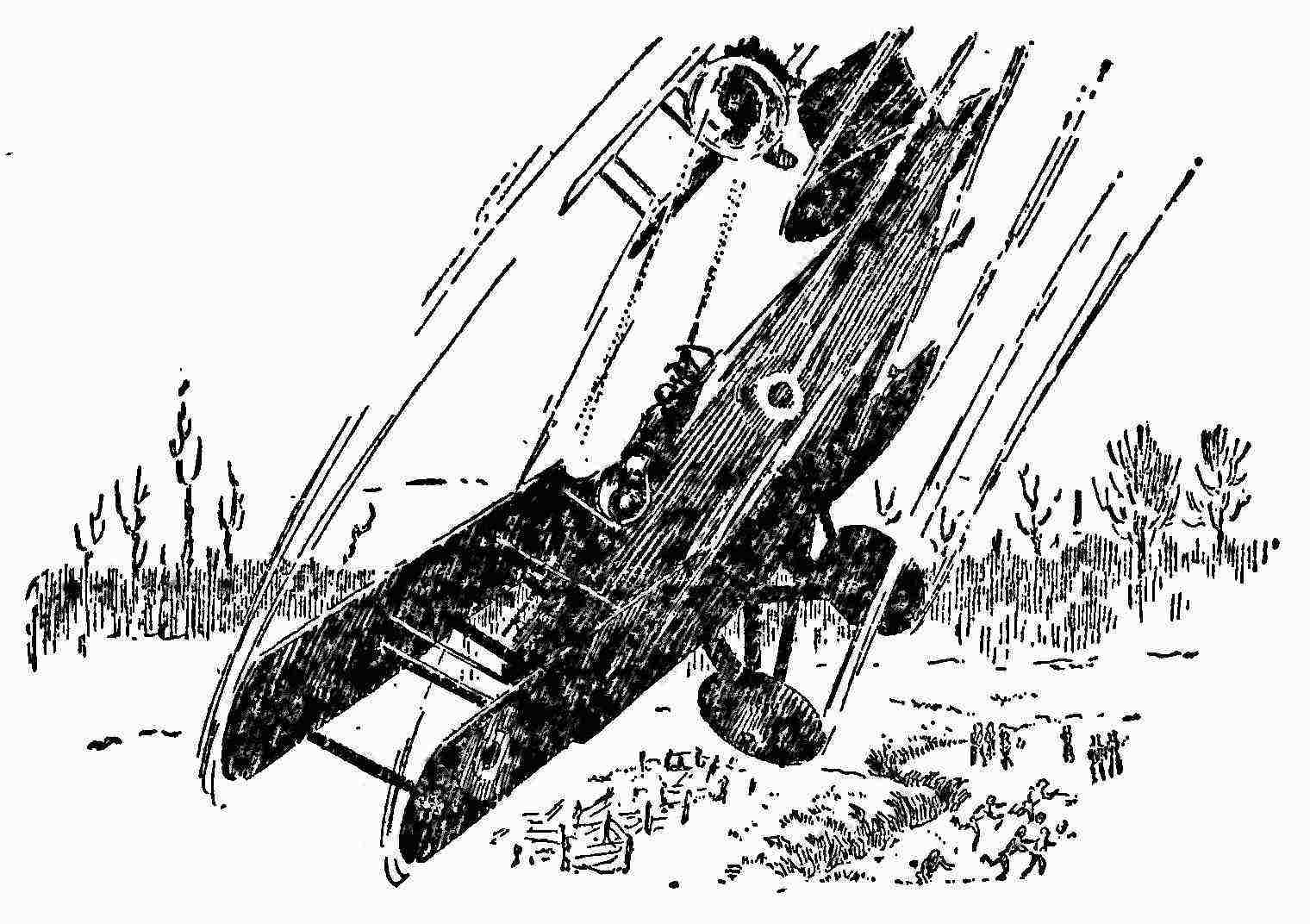

Three white streaks cut past Sergeant Galladay’s left shoulder. He glanced upward, an oath of surprise on his lips. Three little planes with black crosses painted on their wings had appeared out of nowhere and were diving on the De Haviland, their guns gibbering death. Tracer bullets cut through the wing fabric. A panel strut not six inches from Lieutenant Weaver’s right ear flew into splinters. Sergeant Galladay stood braced in the gunner’s cockpit as if paralyzed, his mouth open, his eyes bulging, his guns forgotten, too surprised to move, even to think.

Buck Weaver was thinking fast enough for two. He had counted on Galladay to keep close watch from behind and the attack had taken him completely by surprise, but he was young enough to react with lightning rapidity. Full motor he gave the De Haviland and banked it into a steep, climbing turn. He was endeavoring to shake the Fokkers off his tail and to bring his own fixed guns to bear, but the Germans were no novices. The leader zoomed upward and the other two circled right and left and dived again.

Weaver glanced quickly around him, hoping for support. To his right Hap Johnston was having troubles of his own, a private little dog fight with two other Fokkers. There was no help there, no help anywhere, only the three enemy Fokkers attacking from three directions, converging their fire.

Desperately Buck Weaver dived, twisting the plane like a snipe in flight, but the Germans’ fire continued to find its mark. Bullets ripped through the fuselage, tore at the wings, splintered the struts. One cut Weaver’s sleeve and a second later another struck him in the shoulder, shattering it. He cried out, but strove valiantly to keep control of his plane.

Old Sergeant Galladay saw it all happen with wide, fear-haunted eyes. He hadn’t made a move, hadn’t fired a shot. He seemed paralyzed—a statue of a man. Now the De Haviland nosed over into a vertical dive. With a supreme effort Buck Weaver straightened up and momentarily righted the plunging plane.

“Dad! For God’s sake, heads up!” he screamed.

Sergeant Galladay couldn’t hear the words but the agonized look on Weaver’s face struck him like a dash of cold water, startled him back into reality as if from a nightmare. His mind, which had been stricken numb, suddenly began to race like the motor. The predicament he had created flashed in a searing flame across his brain. Buck fever! He, the old-timer, veteran of a dozen campaigns had been stricken with buck fever like the rawest recruit! But not for long. No, sir! Hadn’t he promised that yellow-haired girl to bring her man back safe and sound? Hadn’t he? And here was her man, good old Buck Weaver, in desperate straits.

With the quickness of a cat the old sergeant bent low in the cockpit and swung his guns to bear on the nearest Fokker. Emboldened by the apparent defenselessness of the De Haviland, the German plane was diving straight upon its prey.

“Damn you! Damn you!” Dad Galladay screamed. “Shoot the kid, will you? Well, I’ll get you for that!”

Rat—tat—tat—tat!

The double Lewises jabbered staccato death. Tracer bullets streaked upward. Sergeant Galladay saw them pour into the fuselage of the Fokker, saw the plane lurch into a spin, motor full on. That was all he needed to see in that quarter. In a flash he swung his guns to bear on the Fokker to the right. The German, observing the fate of his companion, desperately whipped his plane into an Immelman turn. Again Galladay’s double Lewises jabbered one short burst, but the bullets went wild and the sergeant swore coldly, violently, at his own marksmanship.

Buck Weaver, weakened and dazed by loss of blood, fighting back the blackness of unconsciousness, sat bolt upright in the front cockpit and the De Haviland flew as if a mechanical man were at the controls—flew a level course without effort to maneuver, without effort to escape. It was an invitation to the two remaining German planes. They circled and dived again, one from each side, meaning to strike the death blow to this stubborn American plane and the American ace.

Crouched low in the gunner’s cockpit, Sergeant Galladay waited. The Fokkers were already firing. A burst of bullets ripped through the De Haviland’s tail assembly; one glanced off the gun barrel not six inches from the old sergeant’s head, but still he withheld his fire. Buck Weaver cried out again. His leg was shattered this time.

“Dad! Dad!” he shouted. “I’m going—going——” His voice ceased, but his white lips slowly formed two other words: “Ruth—good-by——”

Dad Galladay was sighting along the barrels of the double Lewises, waiting, waiting. He could see the German pilot on the right peering over the side of the plane and it seemed to him that the man was laughing.

“Laugh, will you?” he muttered. “All right, laugh now!” He aimed high, allowing for distance. It was a long shot but he had made as hard ones before in his life. He pressed the trigger.

Rat—tat—tat—tat!

The Fokker lurched sidewise, hesitated a moment; then, in slow, lazy circles it swung downward, the pilot hanging over the side of his cockpit.

Dad Galladay shook his fist at the doomed plane. “Next!” he shouted. “Who’s next? Bring on your whole damned air force! We licked them, eh, Buck, my boy?”

But Buck Weaver did not hear the shouted words. A black veil, spotted with crimson dots, was closing down over his eyes. He felt tired, very tired. Slowly he slumped down in his seat. The pilotless plane nosed over into a dive.

Dad Galladay, clinging to his guns, at first thought that the sudden dive was a maneuver of Buck Weaver’s. Then some inner sense warned him. One glance at the front cockpit told him the desperate state of affairs. Weaver was “out”; the plane was going down out of control. Just then something stung the old gunner in the leg. He glanced upward. The third Fokker, fearing a ruse or wishing to make sure of his kill, was following the American plane down, pouring lead into it. The German was so sure of his prey that he was making not the slightest effort to protect his own plane.

“Gotta get him!” Sergeant Galladay told himself. Once more he squinted along the barrels of his double weapon until the sights were on the vital section of the German plane. “Gotta get him!”

He pressed the trigger, felt the beloved vibration of his machine guns. But the plunging plane destroyed his aim and the bullets flew wild. Cursing, he pressed the trigger again. The guns fired twice—put-put!—and were silent. Out of ammunition! With the swiftness of a magician, the deftness of a card shark, Dad Galladay whipped a pan of cartridges from the rack at his side and fitted it on the guns. None too soon, either. The German plane was not thirty yards distant. Without aiming, almost instinctively, he threw the muzzles of the guns at the German and pressed the trigger. Above him the Fokker wavered; it burst into flames; it shrieked earthward.

The American plane was in little better circumstances. It, too, seemed utterly doomed. It had gone into a tailspin now, the fuselage whipping around viciously. A dozen more turns and the structure, weakened by German bullets, would fly to pieces. The earth where the flaming German lay was racing up at an incredible rate. Nearer, nearer—a matter of a few hundred feet now, a few seconds—and then eternity.

Sergeant Galladay snatched the auxiliary control stick from its brackets in the gunner’s cockpit; unerringly he thrust it into the socket which connected with the auxiliary controls. His motions were cool, precise, his blue eyes were icy cold. And his mind, working with that incredible swiftness which sometimes precedes death, recorded impressions as the whirling tape of a moving-picture camera records pictures—Buck Weaver’s lifeless, bobbing head, the flaming skeleton of the German plane, a trench with men in pot-shaped helmets peering upward, a dead man on the barbed wire in front of the crowded trench.

He pulled the stick back gently. A weakened flying wire snapped like a tightened harp string. Every strut, every member of the wounded plane screamed under the stress. Would she stand it? Would she fly to pieces? And then gracefully the De Haviland righted itself, barely above ground, just over the heads of those white-faced men in the queer, zigzag trench.

A shout sounded, a strange mingling of exultation and savage battle cry. Dad Galladay, “too old to fly,” was soloing at last! Soloing over No Man’s Land, with a wounded pilot in the front cockpit!

Lieutenant Buck Weaver sat propped up in bed in the convalescent ward of a Belgian hospital, just behind the front lines. Around him lingered a faint aroma of perfume and his eyes were fixed upon the door through which Ruth Childers had just left.

Suddenly the doorway framed a wheel chair in which sat Sergeant Galladay. His face was as red as ever and contrasted vividly with the white sheets and white walls of the ward; his grizzled hair rose stubbornly around his bald spot. At sight of Buck Weaver the cold, blue eyes of the old sergeant seemed to become several degrees warmer.

He pushed his wheel chair forward rapidly with his hands until he was beside Buck’s bed, and for a long moment the two sat close, grinning sheepishly at each other.

“Well, I reckon I better congratulate you,” Sergeant Galladay said at last. He threw a stubby thumb toward the door. “I met her outside.”

“What did she tell you?” demanded Buck Weaver, his face beaming.

“Aw——”

“About the congressional medal of honor you have been recommended for, eh?”

“Medal be damned!” burred Sergeant Galladay. “She—she kissed me. I reckon that was for bringing you back alive, eh?”

“And all the time you had those two bullets in you.”

“Aw,” protested Sergeant Galladay, “I never felt ’em. I was too scared to feel ’em.”

“Yes, you were!”

For a moment more there was silence, broken again by Sergeant Galladay. “I reckon you aren’t half engaged any more,” he said, fingering the blanket which was wrapped around his legs. “I reckon you’re all engaged, eh?”

“Yes, Dad,” Weaver said reverentially. “She’s the finest, sweetest, prettiest, nicest——”

“Tell that to the newspapers,” interrupted Sergeant Galladay brusquely. “I heard it all once before, anyway.” He pointed an accusing finger at the young flyer. “Say! I bet you promised her to give up flyin’—get transferred to the damn infantry or somethin’! Didn’t yuh?”

Buck Weaver nodded, but the spasm of mingled disgust and indignation which twisted the old-timer’s face caused him to burst out laughing.

“It isn’t so bad as all that, Dad,” he chuckled. “We compromised. I promised never to climb into a ship again—after the war.”

The expression of righteous indignation on Dad Galladay’s face faded to a sheepish grin. Suddenly his eyes hardened, blue metal between two slits. In his imagination his wheel chair became the gunner’s cockpit of a battle plane, the crutch across his lap a machine gun. Buck Weaver was in the pilot’s cockpit; twenty Boche fighting planes were swooping down upon them. Dad Galladay waved the crutch wildly.

“Bang! Bang! Bang!” he shouted gleefully. “Take that, and that, and that!”

A water bottle on the bed table was knocked to the floor. Its thud brought Sergeant Galladay back to earth, and the wheel chair became a wheel chair, the crutch merely a crutch. Dad Galladay leaned over and touched Buck Weaver on the arm.

“Say, Buck, old-timer,” he confided in an awed voice, “we’ll sure give ’em hell when we’re out of here and flying together, eh?” His voice dropped. “Gosh, it ain’t hardly fair, Buck. No, sir, it ain’t right. We’re jest too damn good for them Heinies.”