Title: The giant sequoia

An account of the history and characteristics of the big trees of California

Author: Rodney Sydes Ellsworth

Photographer: H. S. Hoyt

Arthur C. Pillsbury

Release date: August 2, 2025 [eBook #76616]

Language: English

Original publication: Oakland: J. D. Berger, 1924

Credits: Sean/AB, Robert Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THAT imposing calm which the great Sequoia of the Sierra Nevada exerts over many came to be individually impressed upon the author during a summer’s residence in the Mariposa Grove two years ago. Indeed, it was the persistence of this spell that made him wish to know more about this noble tree and caused him to inquire into its literary and scientific associations. These studies at length stimulated another desire—that of making the gist of the scattered and heterogeneous mass of material, ranging from popular rhapsodies to scientific treatises, available and accessible to all.

It was likewise the author’s ambition to effect a symmetrical presentation if possible of both the popular and the scientific aspects of the subject. Hence, the rhapsodies have been robbed of their purple and the treatises have been faintly touched with imagination to make them possess an interest for the general reader. By this it must not be presumed that gravity and fidelity have been neglected. They have been preserved throughout.

This book has been written primarily for the good of the greatest number. It is not by a botanist for botanists, but by a tree-lover for tree-lovers. And if from its pages there emanates, however faintly, something of the inspiring and enobling presence of the Giant Sequoia, the author will not have dusted off many an old volume and entertained himself with an examination of its contents in vain.

The author is greatly indebted to Miss Cristel Hastings for her untiring aid in the preparation of the manuscript. He also wishes to extend gratitude to Mr. William T. Amis, who has rendered much invaluable assistance and counsel. Hearty thanks are due various Professors of the University of California from whom the author as a student and friend has received many helpful criticisms and suggestions.

| Part One | ||

| SEQUOIAS OF YESTERDAY AND TODAY | ||

| I— | The Auld Lang Syne of Trees | 13 |

| II— | The Glory of the Mountains of California | 23 |

| Part Two | ||

| GIANT SEQUOIAS OF THE MARIPOSA GROVE | ||

| III— | Galen Clark | 35 |

| IV— | Wonder Trees | 59 |

| V— | Oldest of Living Things | 89 |

| VI— | The Eternal Tree | 102 |

| VII— | A Blossom of Decadence | 115 |

| Part Three | ||

| NAMING OF THE SEQUOIA | ||

| VIII— | A Name for the Ages | 127 |

| IX— | Sequoyah | 134 |

| Bibliography | 159 | |

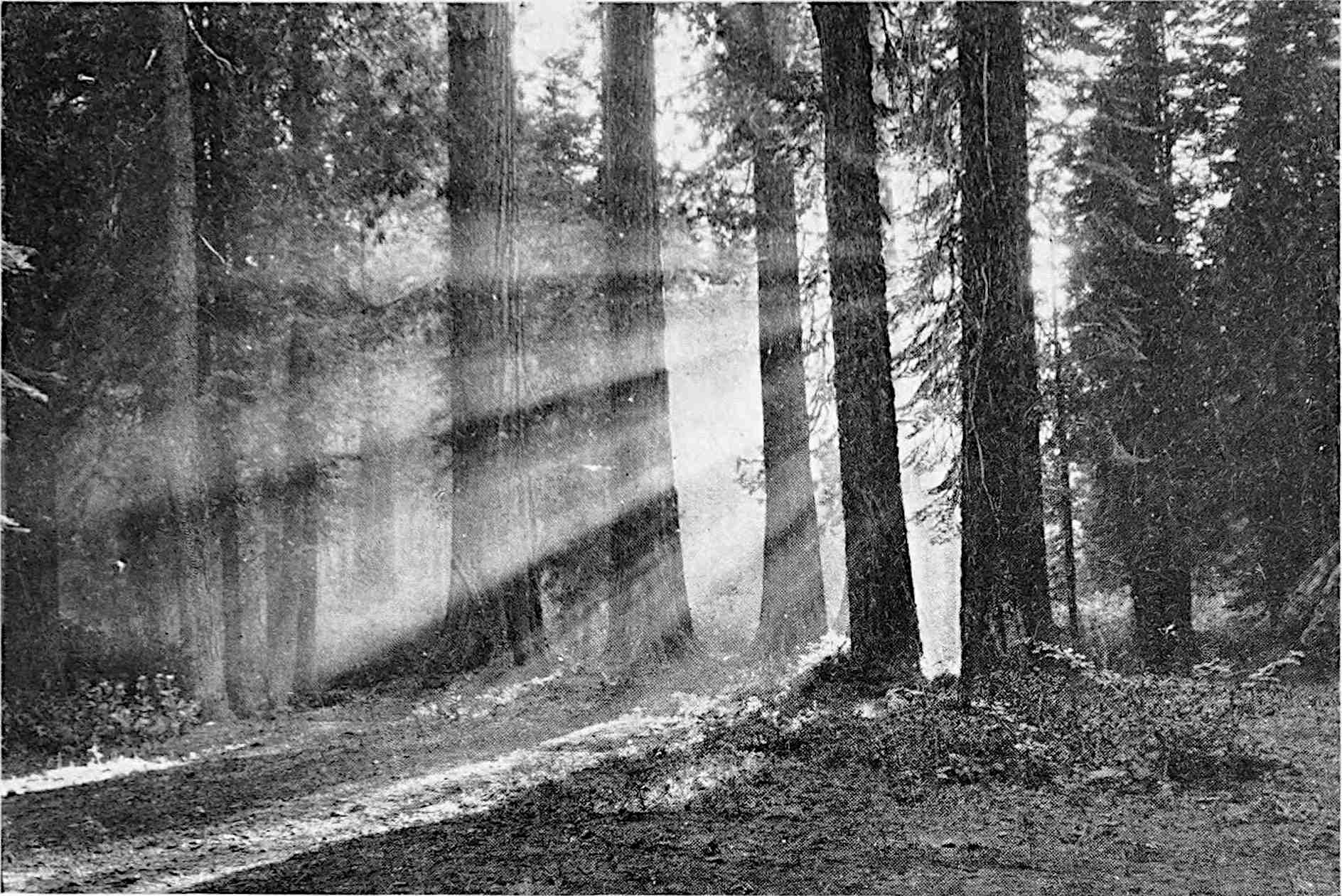

| The Sun Worshippers | Frontispiece |

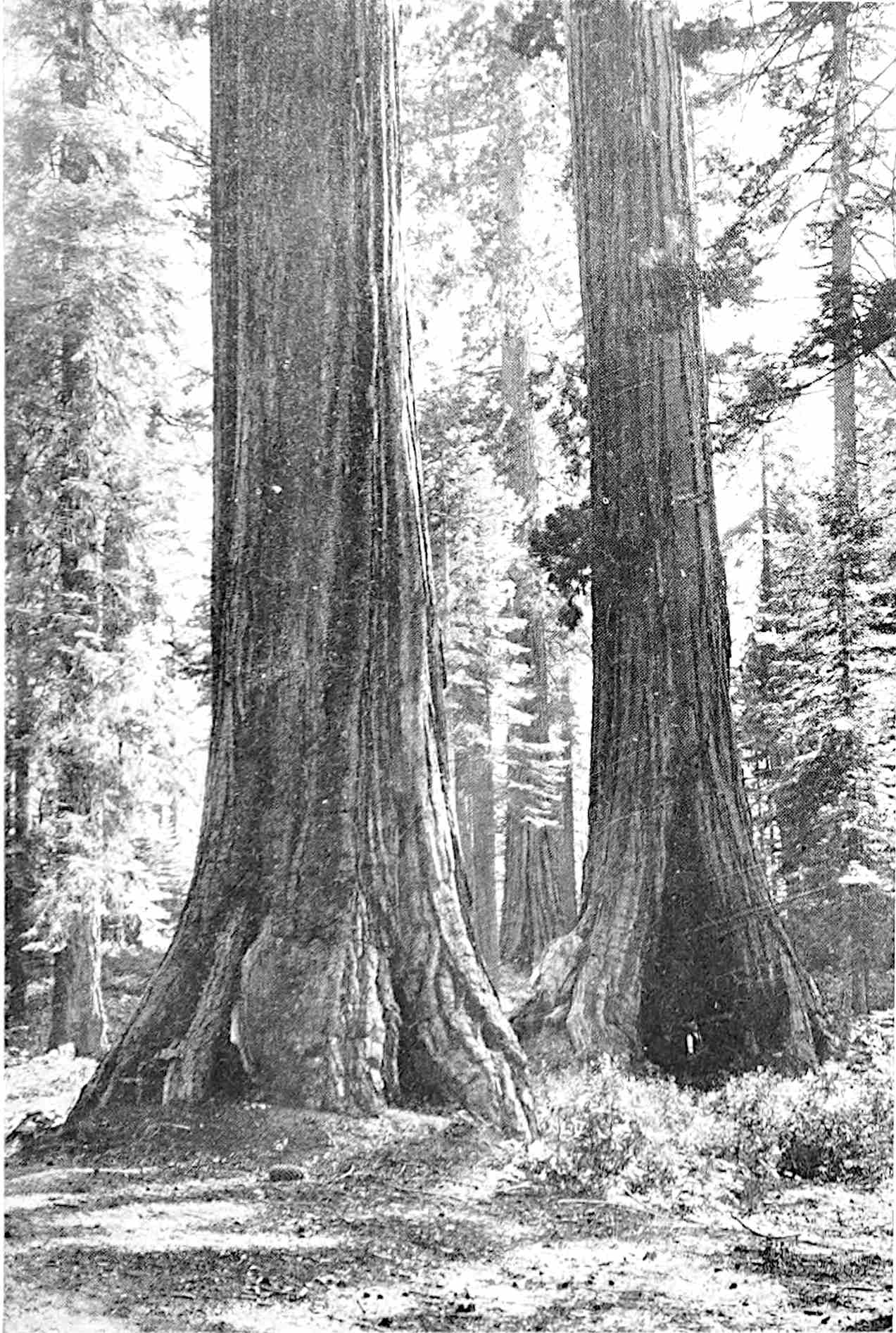

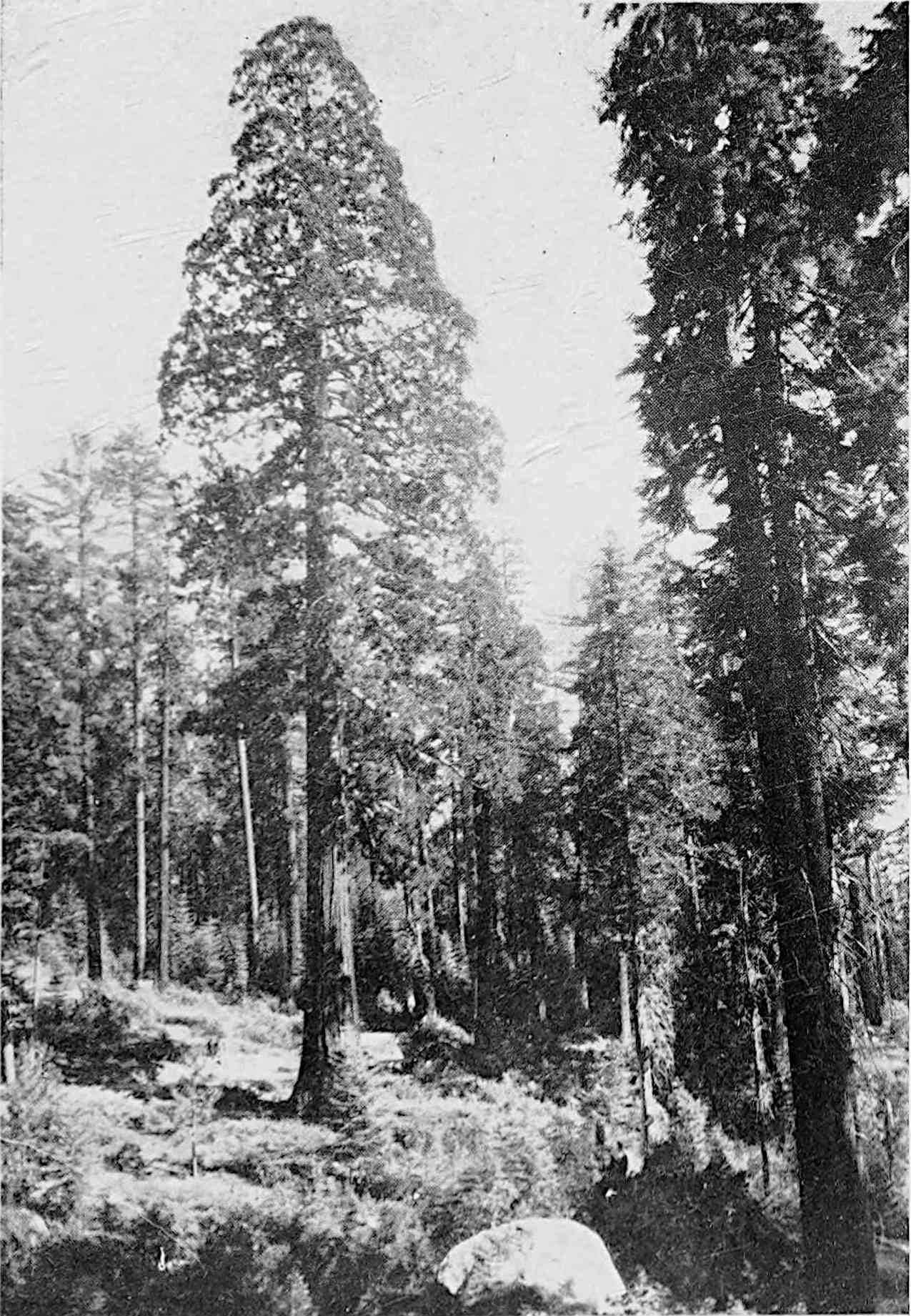

| In the Court of the Giants | 24 |

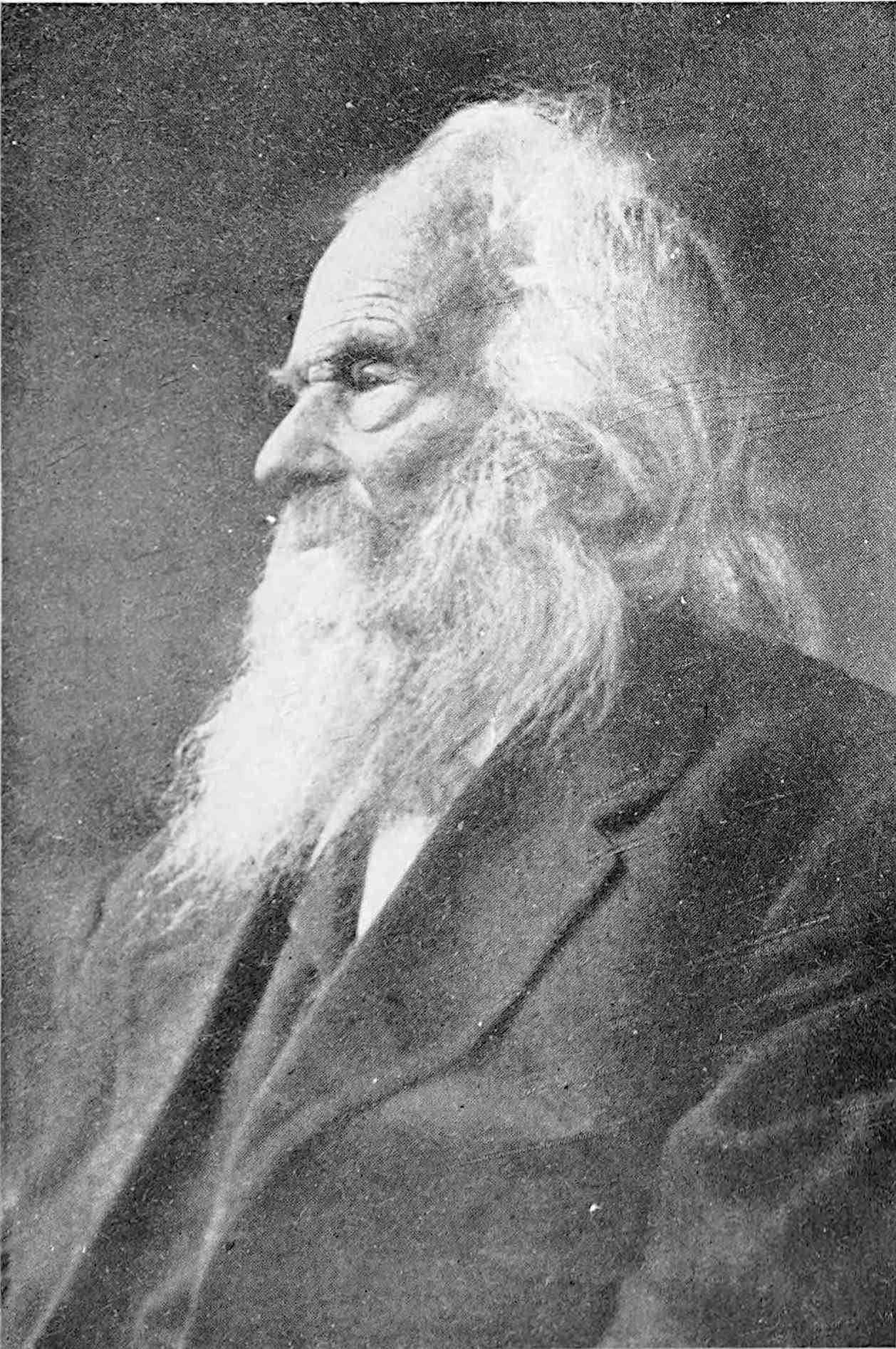

| Galen Clark | 40 |

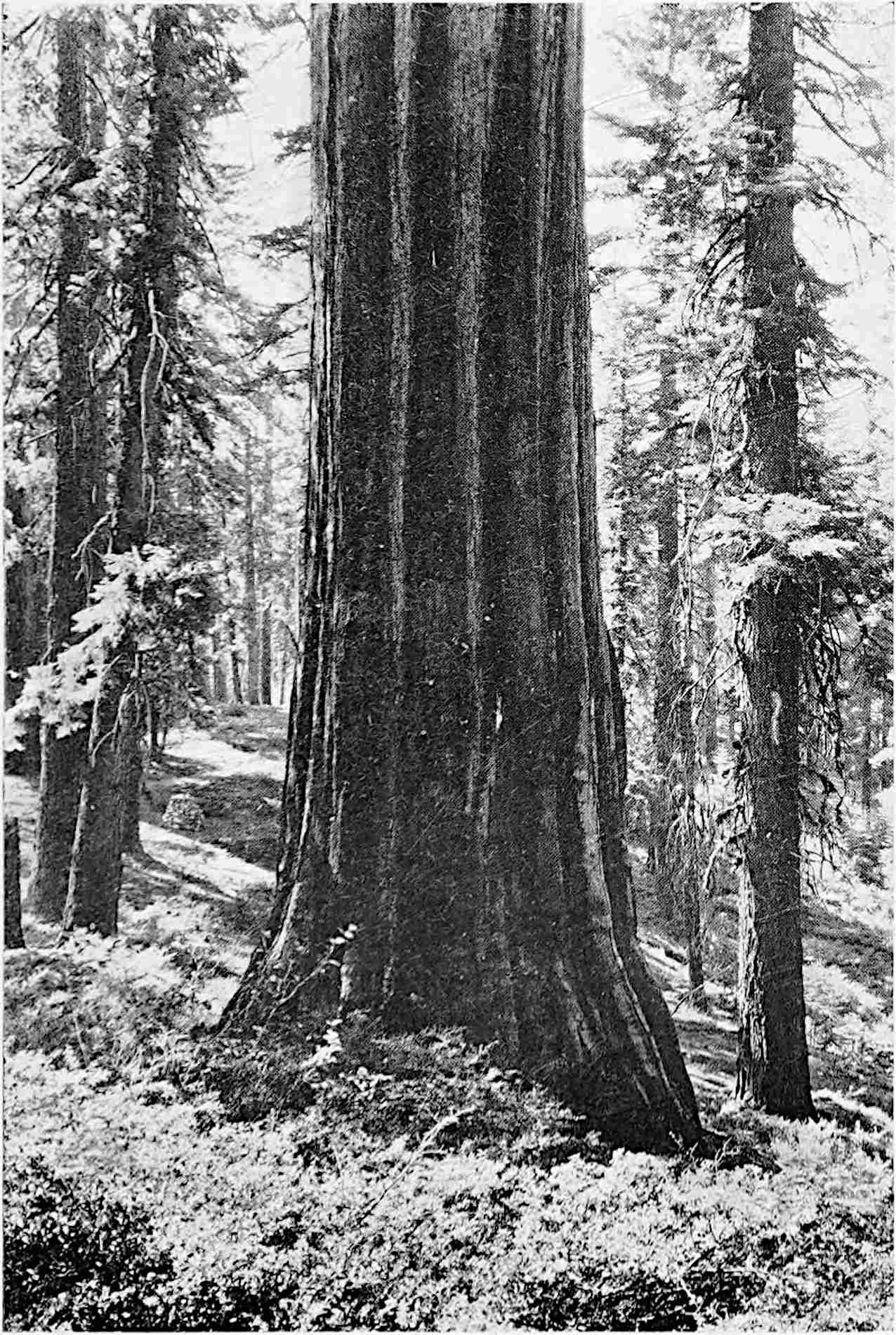

| Galen Clark Tree | 48 |

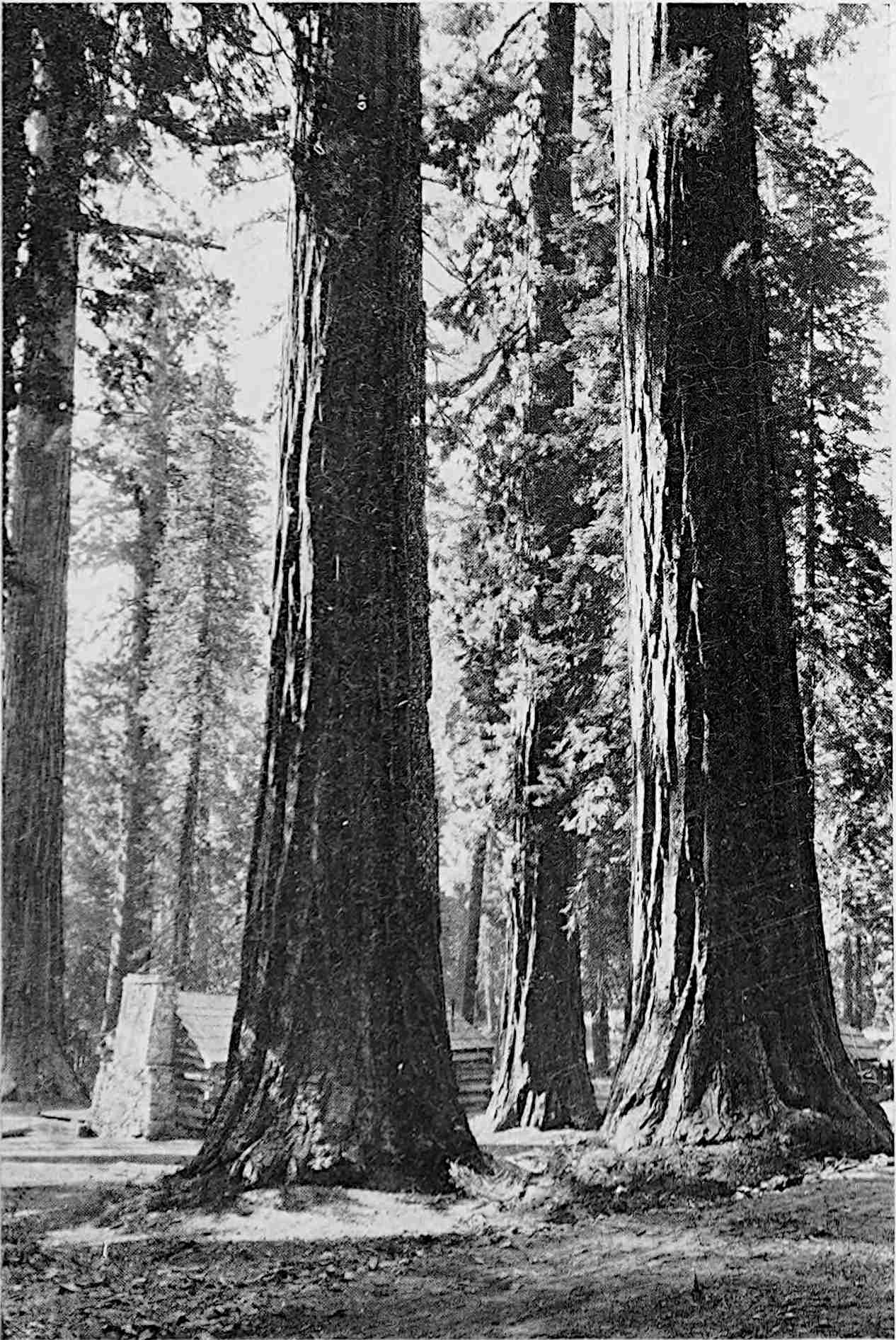

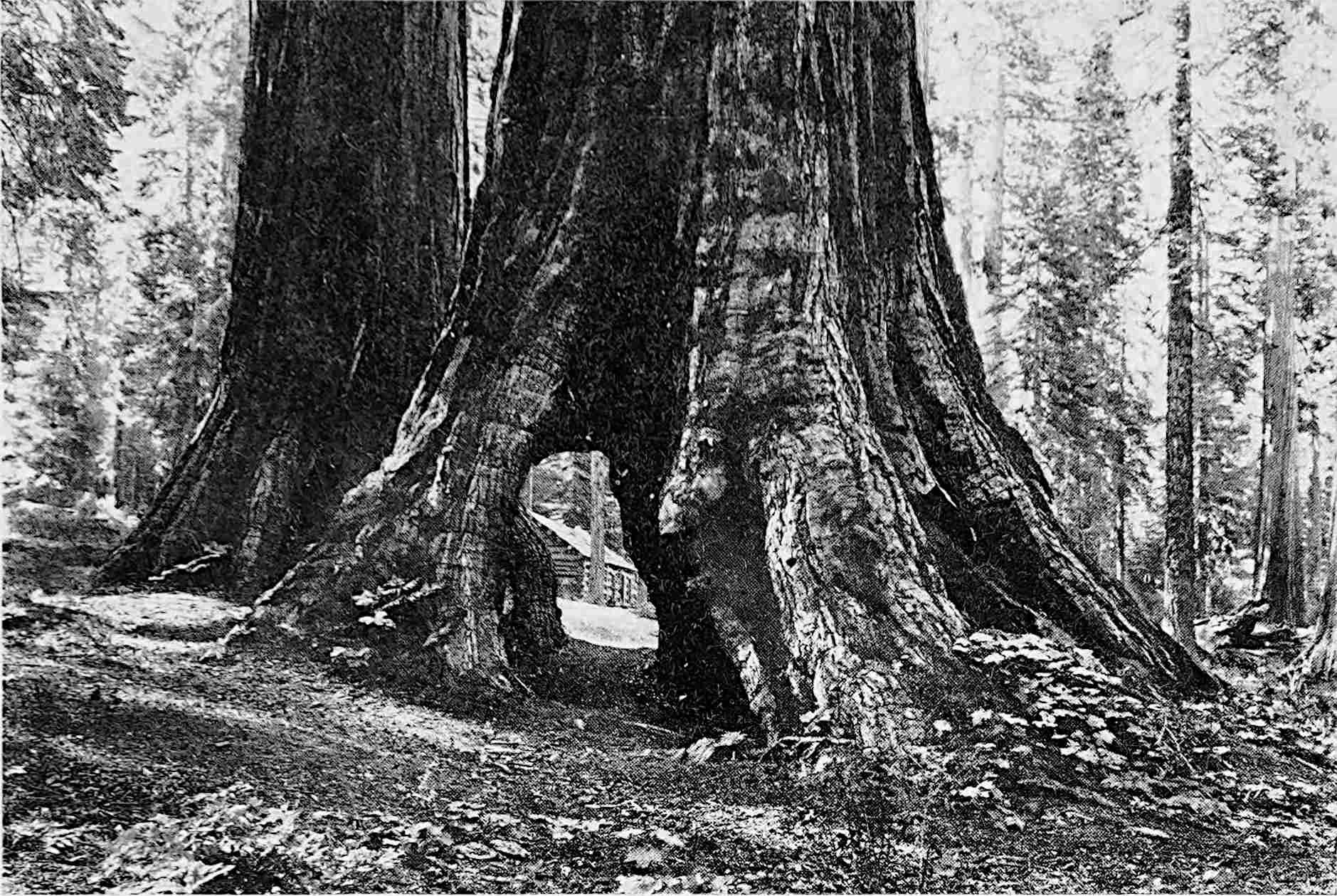

| The Cabin | 64 |

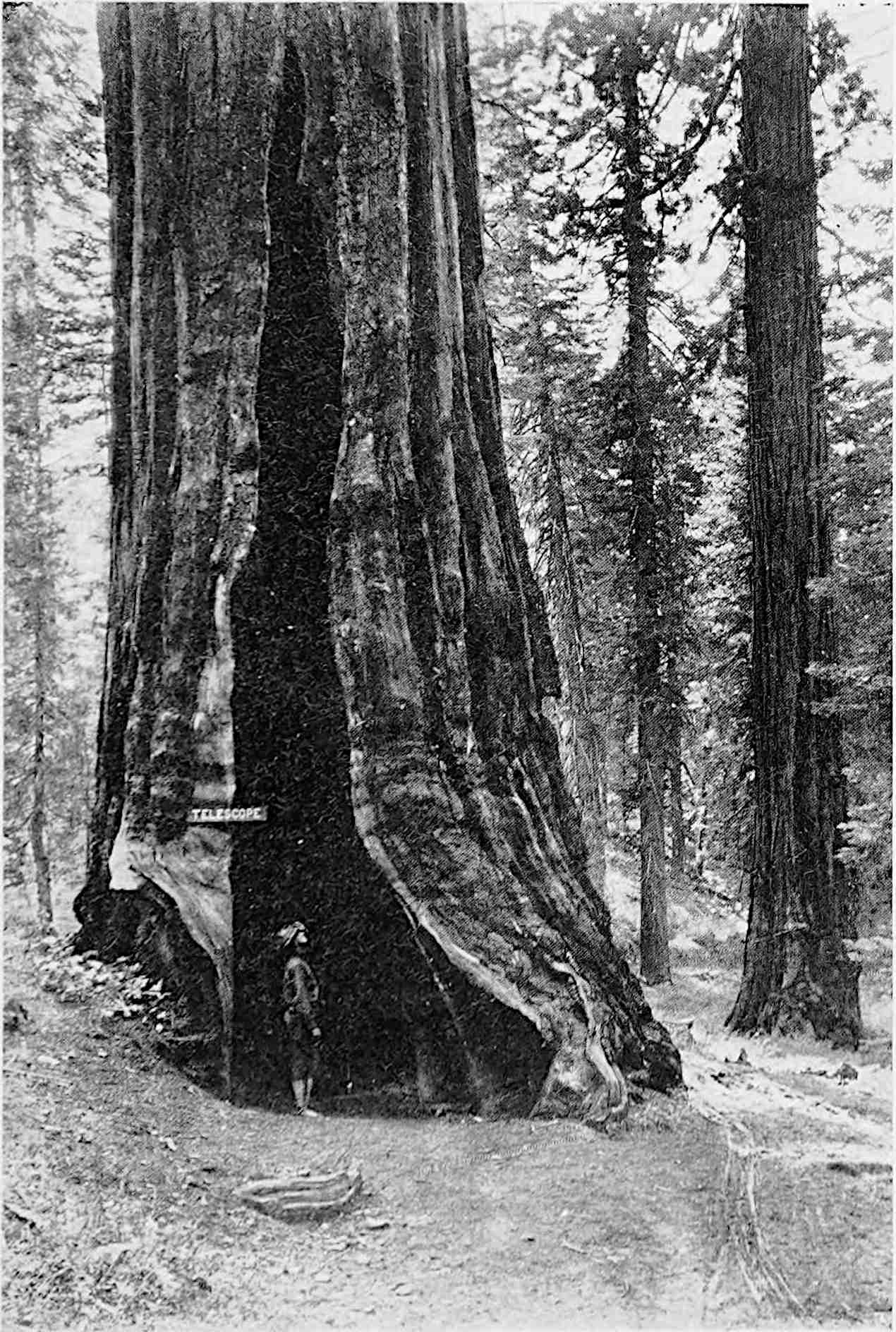

| Telescope Tree | 72 |

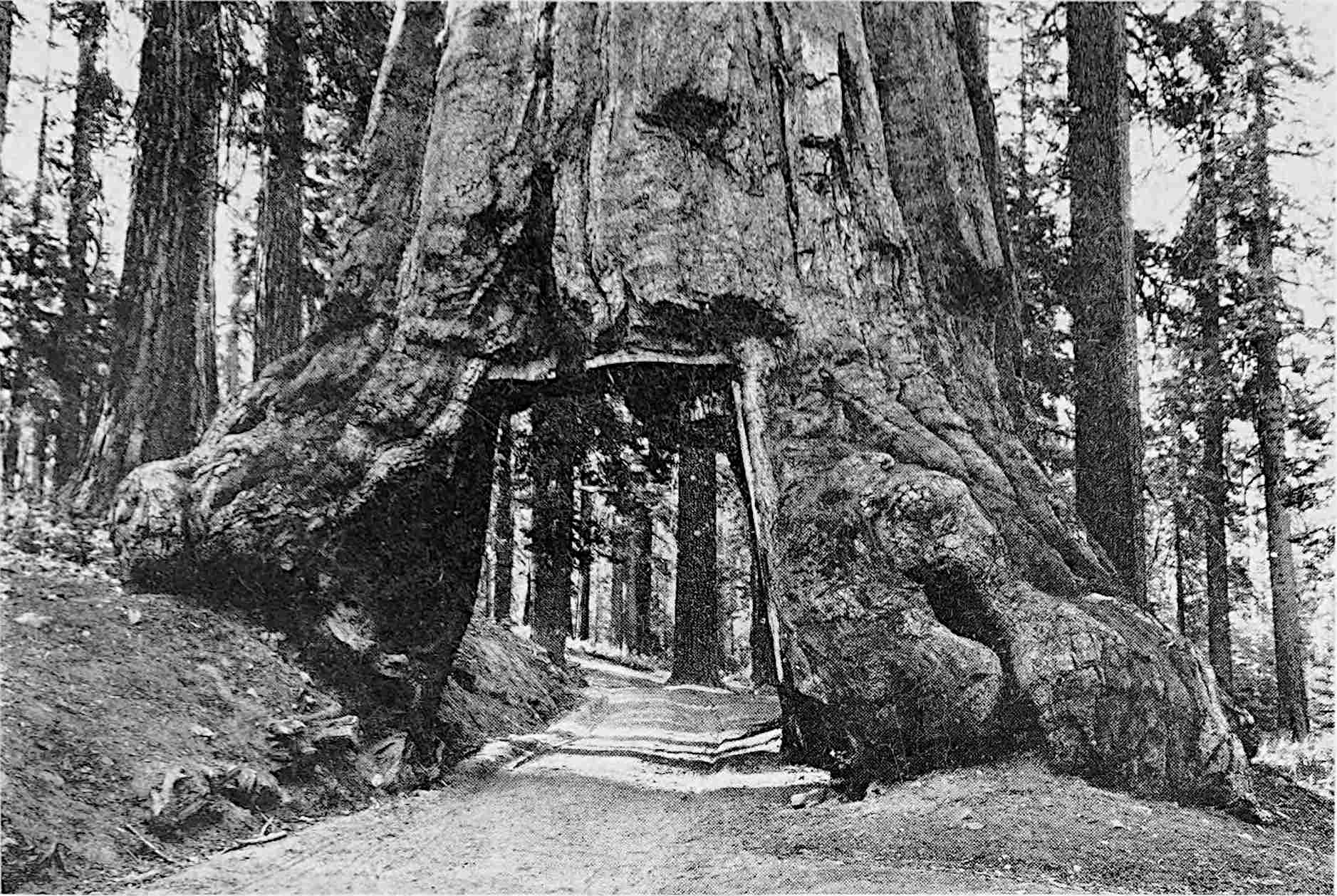

| Wawona Tree | 80 |

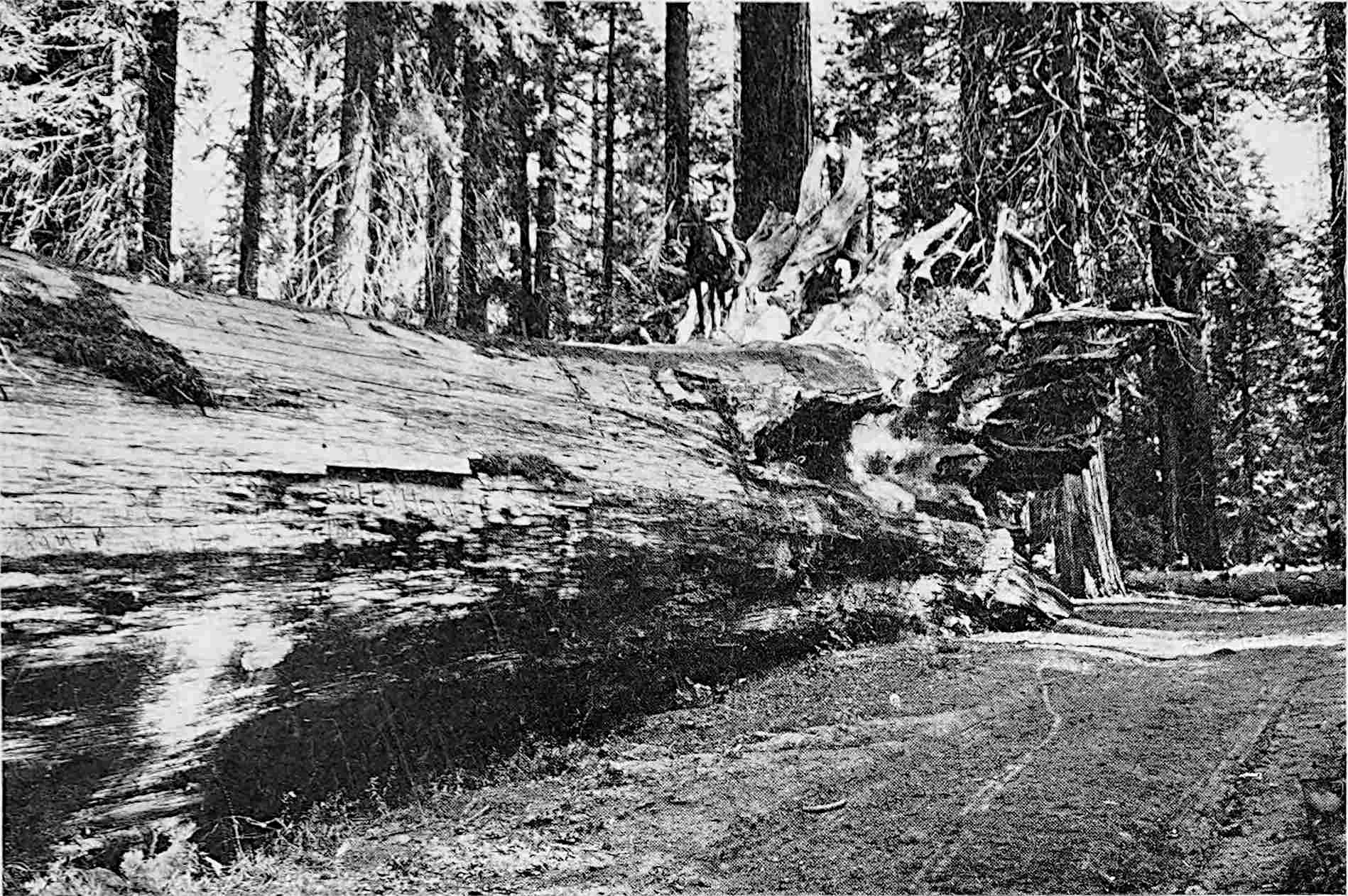

| Fallen Monarch | 96 |

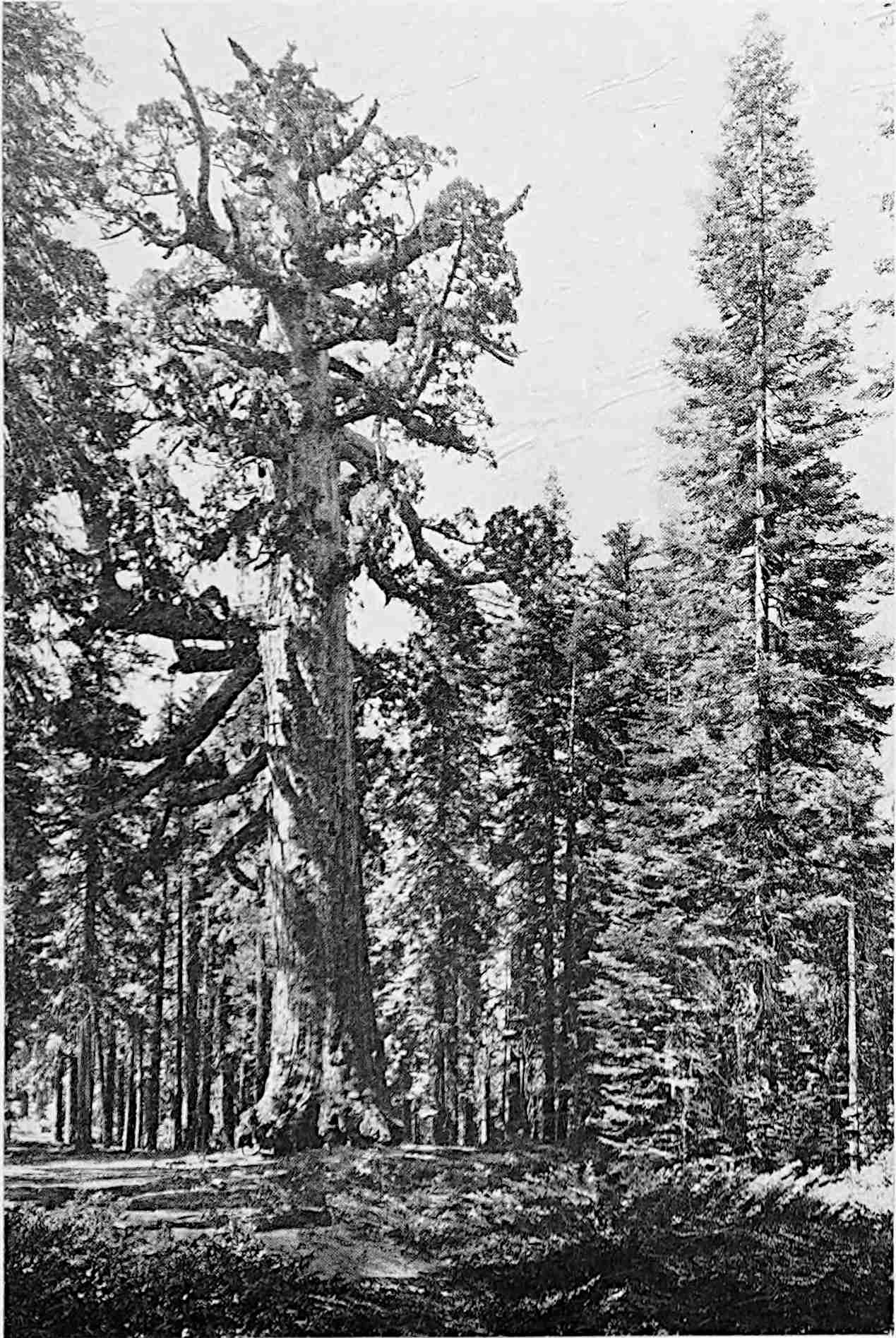

| Grizzly Giant | 104 |

| Alabama Tree | 120 |

| Sequoyah | 136 |

| The Invincible Sequoia | 144 |

THE Sequoia is nature’s most magnificent endowment. King of trees, it has no rival in size the world over, nor is it approached among living things in age. Noblest of all conifers, it has the grandeur of granite and the solemnity of marble. Venerable in aspect, it savors of great antiquity, seeming always to wrap itself in the memories of the past. So striking, indeed, is this feature of its appearance that the intellectual traveler often wonders if its race has played a grander part in the past. Is it a living survivor of an extinct age of monsters?

Time was, and not long ago, when such a question bearing on the antiquity of the Sequoia would have been lightly considered. Now, however, mankind is not altogether satisfied with things as they are, but is mindful of how they came to be so, and the ceaseless searches of science are unveiling the mysteries of the past. The spade unearths a coin whose imprint betrays the beliefs or customs, the finish or crudeness, of an ancient civilization. The discovery of a clay tablet, the uncovering of a ruined temple or a forgotten tomb, sheds fresh light upon the history of a people. Bit by bit the evidence accumulates, and as the vision of the past becomes less dim science 14is better able to conjure up before the mental eye the imposing pageants of a world that has passed away.

Shakespeare calls the world a stage. The allusion, though, is confined to men and women. But as the scientist views the great earth-drama that has been enacted throughout the ages he sees a far more extensive application of this thought. To him “the races of the children of life” are the players, by reason of the fact that all life has been superseded by more complex and more highly evolved forms. Indeed, for millions of years countless multitudes of living creatures have played their little parts on this earthly stage and have gone their way into oblivion. The majority have left as little record as the autumn leaves that drift by the wayside. These are the so-called “lost creations.” Yet a sufficient number have been preserved for the later instruction and delight of man. “Everything,” observed Emerson, “in nature tends to write its own history. The planet and the pebble are attended by their shadows, the rolling rock leaves its furrows on the mountainside, the river its channel in the soil, the animal its bone in the stratum, the fern its modest epitaph in the coal.”

These remains filed away in the archives of nature’s great storehouse constitute the record of the rocks. And as science reconstructs a civilization of yesterday from its rude implements, in a similar manner it interprets the mute meaning of 15these fossils in the rocks. The dry bones and empty footprints are given animation and pictured as they are supposed to have been when alive. Great flying reptiles, called pterodactyls, with an enormous wingspread of twenty-five feet, have fallen into Miocene seas and have been entombed with the leaves and muds of their shallow bottoms. Huge reptiles, called dinosaurs, have stalked across the mud-flats of primeval lakes, leaving their broad footprints in the oozy surface. The tide has come in and gently covered the impression with a fine sediment and preserved it forever. Further deposits of sediment have accumulated and the whole become submerged, until, under constant pressure, they have been compacted into rock and in the course of time have been raised again to dry land.

The record of the rocks discloses the fact that the Sequoia flourished on the earth when these dragons of old time and their weird kin inhabited it. Its forests extended over three continents and it blessed with its shade these creatures more strange and huge than the earth has since borne. Under its high, arching columns dinosaurs took toll of all that could be conquered. Within sight of its imposing forests others, equally formidable, wallowed in shallow seas, while overhead soared pterodactyls, neither bats nor birds, but giant lizards that had acquired the power of flight.

This was millions of years ago. It was during the middle period of life, or, what geologists 16term the Miocene. It was before the advent of fur and feathers—aeons, almost, before man’s coming. In point of time the antiquity of all living things on earth today is of a recent yesterday when compared to the antiquity of the Sequoia. The frail tenure of human works is as but a thousand years amid eternity; nothing; a mockery.

The pick of the fossil hunter has unearthed fossil remains of Sequoia leaves and cones in strata as early as the Triassic. This period represents the morning of reptilian life and is the first of three great ages of the Miocene. At its advent moving life had already safely crossed the border-line of its dependence on water for existence and had succeeded, slowly and laboriously, in invading dry land. Hence, the Sequoia as a race has a claim to almost fabulous antiquity.

Memorials of the Sequoia’s ancestry are more abundant in the rocks of the two succeeding periods of the Miocene, the Jurassic and the Cretaceous. Under the lava flows of Mt. Shasta imprints of its leaves and cones are found. This is indubitable evidence that the Sequoia existed in California at that time. Fossil remains have also been found in localities ranging from “France and Hungary to Spitzbergen and from Greenland to Oregon and Nebraska.” These stratified remains offer positive proof that the Sequoia was a great genus covering the entire Northern Hemisphere and that the now desolate Arctic regions, which were then warm, were luxuriant with 17many of its species. In short, the Sequoia was one of the chief garments of the earth’s vegetation during Miocene times. Its forests must have been the most imposing the earth has ever known. Truly, they were the forests primeval.

It is not a little remarkable that the Sequoia was in existence even before the very mountains which are enobled today by its presence. The vagaries of mutability have been such that it was actually present on earth during the genesis of the Sierra Nevada and saw this range lifted to its place in the sun. Indeed, the eternality of the hills is a misnomer, for mountains have their birth and their youth, their old age and their obliteration. Like successions of living forms they have had their entrance and exit on this terrestrial stage.

During the early period of the Miocene, that country which lay between the Rockies and the Pacific was a flat plain of low relief, with meandering streams and vague divides. Occasional rounded hills broke the monotony of this plain. These were but the abraded stumps of a pre-existing mountain mass—the ruins of mountains that had been. About Jurassic time a general disturbance occurred in the present region of the Sierra Nevada. This was accompanied by an intrusion of a vast body of molten rock which, when solidified, became the granite of the Sierra. During the Cretaceous the entire region between the Rockies and the Pacific again awoke and began to bulge at slow and intermittent intervals. 18The Sierra block had its origin during one of these upheavals and acquired a slight westward slant.

During the age that gave man to the world, the Sierra was uplifted to the light. About the dawn of the Quaternary, the last of the great divisions of geological time, the greatest manifestation of Sierra mountain building took place. This convulsion of the earth hoisted the snowy range to its present sublime elevation.

Following this upheaval came an age of ice. It is to this period that Yosemite Valley owes its glaciation. In fact, the present indefinable charm and fierce grandeur of the High Sierra are legacies of this reign of ice. However, the glaciation of the Sierra must not be correlated with the continental glaciations which ushered in the age succeeding the Miocene. The former glaciation is “more properly to be regarded as corresponding to the very last episode of that long and varied chapter in the geological history of the continent,” states Lawson. Though the final uplift of the Sierra block is a long time past as years go, geologically speaking it is not remote. Indeed, the Sierra Nevada might “safely be placed among the young and giddy mountains of our planet.” From the comparative point of view, on the other hand, the waste of years that have elapsed since the Sequoia first waved its magnificent evergreen dome toward the heavens is bewildering.

Impressive as the evolution of the Sierra must have been, few of the dramas of the earth which 19science has restored are more wonderful than the restriction of the Sequoia exclusively to the mountains of California. The record of the rocks following the great Age of Reptiles tells quite a different story. With amazing abruptness all the rich diversity of reptilian life apparently ceased. Some change seems to have occurred, blotting it out forever, for not a scrap of evidence remains of its continued existence. The dinosaurs are no more; the pterodactyls have vanished. A new type of life, that of the mammal, now holds dominion over the earth. Most astounding of all, the Sequoia still carries on, even to the present day—living survivor of the Age of Reptiles.

Authorities are not agreed concerning the causes that led to the extinction of the reptiles. Science still ponders over the mystery. A feature so extraordinary seems to demand an unusual explanation. Causes of a violent cataclysmic nature are advanced as valid interpretations. Yet science refuses to take cognizance of universal calamities and considers them as apocryphal because they are too unnatural. Climatic conditions, in the main, are probably responsible, for it is upon climate that the wealth or poverty of life on the globe depends. That which was a land of comfort, of abundant food, and of continual summer may have become, through a process of alternate haste and deliberation, a land of long winters, of bitterness and hardship. The good days of the world were exchanged for hard times, 20and those who could not survive were gathered to their forefathers. This, together with volcanic eruptions which took place on a stupendous scale, followed by glaciations of continental extent, apparently conspired in the ultimate undoing of reptilian life. These causes, in all likelihood, are responsible also for the shrinking of the majestic Sequoian woodlands to a mere fragment of their ancient, vast extent.

About the end of the Miocene the earth became intensely active. In its agitation some of its seething interior was exuded to the surface in a deluge of lava. At the same time fountains of molten rocks shot up from volcanoes, causing the heavens to rain fire about them, and sifting ashes afar over the earth. Rivers and lakes floated up in immense clouds of steam over which the blazing beacons suffused weird colorings—lights and shades of an inferno that not even the pen of a Dante would have the temerity to attempt to describe. A land of beauty had become filled with forms of the gloomiest and ghostliest grandeur. The great dinosaurs looked with disquietude upon it all. Unable, by reason of their cumbersomeness, to migrate to a gentler clime, they stoically awaited their doom. The pterodactyls, terrified, fluttered to the ground, flapping their great useless wings as the unearthly flashes from the heavens fell upon them. The noble Sequoias, even more impotent to make a retreat, held their ground until set afire or enveloped in floods of 21molten lava. At length, having exhausted its fury, this agent of wholesale ruin ceased as if stricken lifeless in the midst of its maddest rioting, and the land became a far-stretching waste out of which life had apparently gone forever.

The unknown complex of causes which brought about the ice age that followed probably completed extermination of the reptiles, and it certainly brought the Sequoia, as a race, perilously near to extinction. The temperature became too cold for life adapted to the warm conditions of the Miocene age. As a result, reptilian life paled and declined, until finally its feeble flame flickered out entirely with the arrival of the glacial epoch. The vast amount of water that had been vaporized during the volcanic eruptions returned to the earth in the form of snow. This accumulated in such enormous quantities that continents came to be white worlds where the vacant sky communed only with the silent ice. Pulseless and cold, these vast continental ice caps were as eloquent of death as were the fiery lava flows. Uncharted, trackless seas of ice they were, with all traces of earthly travail buried far beneath them. And a terrible solitude was the lord of this universe.

The scientific world is equally perplexed regarding the mysterious chain of events that again caused the amelioration of climate. At any rate, the warmth of summer gradually overtook the snows of winter, and the ice wasted away. Like 22morning mist it vanished in the sunshine. Lakes filled the yawning throats of volcanoes. Light and beauty replaced ashes and death. Life, too, ebbed back from the southland and conquered the desolation, filling the vacant world with a glorious animation. But it was a different type of life that came. Mammals instead of reptiles now held undisputed dominion. Of all the rich diversity of life that flourished before the advent of the ordeal of volcanic fire and the chilling empire of ice, apparently only the Sequoia escaped utter destruction.

It is this singular survival that prompted John Muir to write of the Sequoia as a “tree which the friendly pines and firs seem to know nothing about. Ancient of other days, it keeps you at a distance, taking no notice of you, speaking only to the winds, thinking only in the sky, looking as strange in aspect and behavior among the neighboring trees as would the homely mastadon and hairy elephant among the bears and deer. It belongs to an ancient stock and has a strange air of other days about it, a thoroughbred look inherited from the long ago—the auld lang syne of trees.”

BUT two species of the genus Sequoia carry on the noble line in these feeble times. Scions of a race whose ancestors extend into the depths of the ages, they seem to be not a part of this puny world. Gigantic in proportion, they are not unlike uncouth vestiges of another age when all things were molded on a monstrous scale. Numbering their years by thousands, they are an “unaccountable oversight” in a world where lives are limited to the psalmist’s span of years, and where there is no hope of gaining the length of days of Methuselah and his kin. Indeed, they appear to be more like mysterious strangers from some far star than solitary and lonely survivors in the midst of an unfamiliar new age. Patiently accepting the part of on-lookers, they disdain to take their place in the active ways of the world and continue to exist for no apparent reason other than to preserve the pristine glory of their ancestors lest it die with them and leave the coming years.

Rarest of all tree species, these two survivors are the Giant Sequoia, or Sequoia gigantea, and the Redwood, or Sequoia sempervirens. Both are impressive 24in the mystery that hangs over their history. But it is only this that they may be said to have in common. In almost every other respect they are quite dissimilar. True, the Giant Sequoia is a grander and more massive edition of the Redwood. However, the former puts the latter in the shade as to girth, while the latter dwarfs the former as to height. The Big Tree is unexceeded among trees in girth; the Redwood probably outstrips all trees of the world in height. Rarely does the Big Tree lift its towering column of verdure more than 280 feet into the heavens. Yet it attains an amazing trunk diameter of 20 to 27 feet well above its immense swollen base. The Redwood seldom produces a trunk more than 15 feet in diameter and the average of the larger trees range from 8 to 12 feet. Trees 280 feet high are not altogether uncommon. Some even wave their evergreen crowns 340 dizzy feet above the ground—truly a prodigious altitude for living shafts of wood to attain.

The Big Tree keeps its youth longer than any known tree and for this reason is acclaimed the oldest living thing. Frequently it reaches as great an age as 2,500 years. A few Giant Sequoias are known to have passed their three thousandth year. Seemingly, this figure fails to convey a satisfactory comprehension of the magnitude of such a great age to the minds of popular writers. As a consequence, the age of this grand tree has suffered unpardonable padding. Nevertheless, 25such estimates are not conclusive and rest only on the speculative notions of fanciful writers. The Redwood, on the other hand, while quite noteworthy in longevity in the tree world, scarcely sees a thousand summers. It must yield the palm in all honor to its greater cousin which ranks first in age of all the worthies of the tree kingdom, and, hence, in the world of living things.

The Sequoia sempervirens is one of the most consummately beautiful of trees. Its beauty is as rare and undefinable as the blue on the mountains in the hour of twilight, as startling and lovely as a flower-clad April, as charming and delightful as the notes of a melody that the winds bear away. And yet beauty is its least perfection. All the cheerful gayety, the contented peacefulness, the warm companionship that are the chief glory of other trees, the Redwood, too, possesses. It is one of the most lovable and friendly of trees. But there is nothing rough or common about it, nothing coarse or voluptuous. To know it is to know something that is genuine. To admire it is to be unable to look upon it with the cold eye of a judge, but with the reverence of a worshipper and the veneration of a child.

The Sequoia gigantea is formidable and sombre in aspect and very often terrible to look upon. Impassive, unapproachable, uncommunicative, it is the very autocrat of the forest. Godlike in physiognomy, at times it is impossible to understand. 26It has a loftiness of port, a dignity of bearing, a sublimity of energy that command attention and win their way insensibly into the soul. Its nature is as hard and flinty as the granite of the mountainside. But in spite of all this highmightiness there is something forlorn and pathetic, something sad and benign about it. All who know the pathos in memories of days that are accomplished and faces that have vanished will realize how replete this tree is with sadness and tenderness. Grand though it is in the religious solemnity and silence that rest upon it there is something pathetic about its very loneliness that resembles sadness as mist resembles the rain. Assuredly, if the Sequoia sempervirens is the most lively and cheerful of trees, the Sequoia gigantea is the saddest and the grandest.

If the Redwood be considered Grecian in its glory, the Giant Sequoia is Roman in its grandeur. Both produce forests of giants. In one beauty and grace held splendid court; in the other greatness and magnificence. The one is Grecian in its idealism, so divine in its loftiness as to exert an elevating and ennobling influence, and so fine in its perfection of form as to epitomize this immortal quality of Athenian genius; the other is Roman in its invincible strength, so imposing in its stolidity and massiveness as to embarrass its beholders, and so baffling in its superiority as to thrill them with awe and fill them with wonder. One is an emblem of eternal youth, ever sprouting 27Phoenix-like from its ruins and pressing with youthful vigor upon the faltering footsteps of its mouldering sires, exempt, like the immortal influence of Greece, from mutability and decay; the other is an emblem of permanence, a form of endurance standing among the temporary shapes of time, a structure not unlike a Roman pile, built to withstand the onslaught of the ages.

Today both species of Sequoia are confined to the mountains of California. They inhabit the western slopes of its two systems of mountains, the Coast Range on the West and the Sierra Nevada on the East. The former parallels the ocean; the latter forms the backbone of the State. Enclosed between these mountain chains lies the great valley of California—a vast, oval plain, scarred all over with grain fields and orchards, and mottled with shadows from the drifting sky squadrons—with its two central rivers, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin, meeting in its center and flowing with tranquil deliberation through a series of bays, on through the Golden Gate to the Pacific.

In comparison with the vast distribution of the genus during Miocene times these two surviving species now occupy a mere fragment of territory. The Redwood is restricted solely to the coastal mountains; the Big Tree obtains only in the Sierras. Together, by reason of the lofty height of the coast species and the gigantic girth of the Sierra species, they comprise a group of 28conifers unrivaled the world over. Since they are found nowhere else, California rightfully merits John Muir’s claim of being the “Paradise of Conifers.”

The Sequoia sempervirens forms a tolerably uninterrupted belt along the seaward side of the Coast Range. This belt is approximately 450 miles long and extends from just beyond the northern California border-line, where it fades out noticeably, south to the bay of Monterey. The maximum width of the Redwood belt is thirty miles and reaches from nearly sea level to an altitude of 3,000 feet. In the vicinity of Crescent City the Redwood approaches the ocean so closely that its tiny cones scatter their minute seeds about the cliffs upon which the wild waves of the Pacific beat. In the hot interior valleys that lie parched and shimmering under summer suns—valleys that are moistened only occasionally by winter rains, conditions are apparently too unfavorable to permit of its growth, and the tree is absent. It thrives only where the fog-laden atmosphere hovers about its crown. Its feathery arms seem to drink in these hazy, lazy mists as if by magic and to precipitate them into gentle showers. Along the river flats frequented by sea fogs, where the soil and environment are ideal, it attains its greatest development. Indeed, on the bottom lands of the Smith River and the main fork of the Eel in Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, the Redwood “completely monopolizes 29the soil and forms virgin forests of the heaviest stands of timber in the world.” “Stands,” according to Jepson in his monumental Silva of California, “of 125 to 150 thousand feet, board measure, to the acre are not uncommon. Instances of even two and one-half million board feet to the acre are on record, while 480 thousand feet, not including waste, have been taken out of a single tree.” When it is realized that good eastern forests produce but ten thousand board feet to the acre, this statement is striking. In fact, such an immense yield separates the Redwood from all the timber trees of the globe.

The Sequoia gigantea is more limited in its range than its fog-loving cousin. Its belt is but 250 miles long and extends from the middle of the American River, near Lake Tahoe, to Deer Creek in Tulare County. It is found in the verdant center of the coniferous belt along the middle heights of the Sierra. This zone of finest vegetation is located between the altitudes of 4,600 to 8,000 feet above the sea where the environment insures the most nearly perfect conditions for tree life; where heat is tempered by elevation and the cold of winter is modified by the proximity of a great sunlit valley. The area covered by the Big Tree, however, fails to equal a hundredth part of that which the Redwood occupies. This is due to the fact that the Giant Sequoia does not occur in an uninterrupted belt. Unlike the Redwood, generally speaking, it congregates in groves. 30Single trees are rarely found alone in solitary grandeur. Preferring the society of its fellows, the Big Tree is almost always found in “family clusters.” Though mingling with Sugar and Yellow Pine, with White Fir and Incense Cedar, these Sequoian groves never lose their identity. The size of the individual Sequoias and their concentration within a definite area are sufficient to set them conspicuously apart from the general forest.

Twenty-six of these scattered patches of forest giants sociably growing with trees of shorter pedigree and lesser dignity have been enumerated by Jepson. These groves logically form a northern and a southern group, with the Kings River as the line of division. The northern portion of the Giant Sequoia belt has so diminished in size that it consists of but seven small groves so widely separated that three of the gaps between them are from thirty to forty miles in width. The northernmost group must be called a “grove” by courtesy, since it contains but six trees half of which are less than three feet in diameter. The southernmost, with the exception of the Fresno Grove, is the most remarkable of the northern group. This is the famous Mariposa Grove. In all these northern patches, the Sequoia is an epicure of climate and site. It grows only in locally favored or protected spots where the sunshine is abundant and the soil rich, deep, and moist.

31

The southern groves mark an almost continuous line through the majestic, trackless forests of pine and fir from the Kings River southward to Deer Creek. The gaps in the belt gradually become increasingly narrow, and then cease altogether. The Sequoia may be said to extend across the wide basin of the Kaweah and Tule Rivers in noble forests broken only by deep, yawning canyons with rivers threading their sinuous way down the center of each. Here, too, the belt widens out, extending from the granite promontories overlooking the fading line of tawny foothills to within sight of the summit peaks—regions of rock and ice lifted above the limit of life. The largest and most famous of these forests is the Giant Forest located near the mouth of the Marble Fork of the Kaweah River and within the confines of the Sequoia National Park. This most wonderful of all American forests was named by John Muir, who must have wept for joy when he stumbled upon it. Thousands of trees are congregated in this forest, five thousand of which are said to be veritable titans in size. It possesses, also, the largest tree in the world, the General Sherman, which has a diameter of 36.5 feet and a height of 280 feet—measurements which easily entitle it to wear the purple of the King of all trees.

In this glorious forest the Sequoia is indifferent alike to exposure and soil, and is found growing in profusion on slopes of every character, some 32even clinging to life on bare granite surfaces in a way wonderful to behold. Multitudes of tender seedlings are continually springing up in moist, sunny openings to carry on the royal line, and companies of slender saplings are eagerly crowding up every slope deserted by their elders, crowning all save the highest eminences. In fact, the marvelous bounty of Nature has produced here the finest assemblage of conifers known to botanical science. The entire region is a billowy sea of evergreens, sinking and rising with the undulations of the land with an unfailing luxuriance, the great rounded domes of the giants swelling above the verdant canopy of pines and firs to mark where the Sequoias sweep along the ridges, rise out of deep canyons, or encamp on sunny meadows in conclave grand and solemn.

33

THE Giant Sequoia must have afforded pride and pleasure to the Creator for it is the finest tree He ever made. Of a truth, there is not in all the world a tree more wonderful.

And yet, man has flouted this “shade of His perfection.” Under its shadow he has neglected to gain inspiration and strength. In the restless trend of the times he has become engrossed in empty pleasures. In the agitation and strife for wealth individual interests, and not those of posterity, have become of moment. As a result only that which offers the allurement of gain has been recognized in the great Sequoia. Its solemn and stately forests have been invaded by the axe and commercialism has turned reverence, not into beams and pillars for places of worship, but into supports for grape vines and barbed wire.

36

Fortunately, the Mariposa Grove has escaped the fate which the axe has brought many of its brethren. Like the groves of yore that were God’s first temples it still stands, a virgin forest. The fluted columns of its mighty trees are softened by the touch of centuries, and so harmoniously are these venerable columns disposed that splendid colonades are formed, giving the effect of a vast, many-pillared hall. The airy masses of foliage that these great trunks mingle high in the heavens form cathedral-like archways of the finest forest ceilings imaginable. These magnificent interlaced archways soften the glare of day and impart a dim religious light which suffuse shifting mosaics of light and shade over the forest floor. Even the thick layers of crumbling bark and the dessicated dust of ages serve to deaden the footfall of the wanderer and to invest the gloom with a profound silence. A deep Sabbath-like calm broods in the very air. Indeed, all seems eloquent of worship. Here Nature stands with arms uplifted.

None escape the sacred influence of such a grove. None, save possibly the white man. Deer with eyes of soft innocence trip timorously through it; burly brown bear never shuffle heedlessly down its winding aisles; and rarely does the noisy, impudent jay muster sufficient courage to disturb its serenity. The Indian with his stone axe never harmed it, nor has the myth that he lighted his fires against its trunks, thus “wantonly destroying that which he was too rude to reverence,” 37been substantiated. It is only civilized man who violates such a sanctuary “just so long,” as John Muir so pithily expressed it, “as fun or a dollar can be gotten out of them.”

Truly, the ways of man are at times past understanding. Under roofs that his frail hands have raised he worships, yet he destroys with utter disregard a Sequoian grove—a temple not made with human hands. Such acts may be damaging. They may even be bad. But they are manifestations of human nature—of the clay as it came from the hands of the Potter. Happily, there are those among men who are of more than common clay. Such a man was Galen Clark. It was he who first made known to the world the Mariposa Grove and who faithfully guarded it for well nigh a quarter of a century. He, above all others, rendered it the most completely free from the axe and preserved it in the condition in which his eyes first beheld it. Lest man forget, he saved it as a place of play and prayer.

Galen Clark came to California in the days of the gold boom. Strictly speaking, he was not of the Argonauts of ’49, since he was not seized by the spell of the gold fever until 1853. Shaking the dust of New York from his feet in October of that year, he joined the eager multitudes who flocked toward the new El Dorado. The year 1854 found him in the country of Mariposa taking part in the pick and shovel storm that was then raging on its mountains. Not unlike the majority, 38he failed to find “a chartless river running on fabled sands of gold.” The chase of the fabulous ended; he took up the less fascinating but more substantial occupation of a surveyor. Occasionally, however, the gold lure again possessed him and he spasmodically returned to mining with the flare-up of local bonanzas. It was while so engaged that he contracted, through exposure and hardships that had already filled the nooks of the gold region with the bones of strong men, a disease of the lungs. The physicians, unable to lessen the great number of hemorrhages, prophesied that he had not long to live. Now a member of the dreary brotherhood of failures, health and strength gone, and knowing that death would claim him soon, he did not become a dissolute miner. Instead of finding a refuge in strong drink, he sought solace through communion with the sweet wonders of the common earth and sky. In truth, he went home to Mother Nature, and became a wanderer finding peace on mountain tops and consolation in piney woods.

Singularly enough, his lungs healed. The climate had accomplished the miracle. The bland and salubrious air rendered pungent by the balsamic odor of Sierran forests, together with an abundance of health-giving exercise, had cured the disease. More strange still, Galen Clark attained the venerable age of ninety-six. Though he continued to lead the life of a mountaineer, and constantly to expose his person to calm and 39storm alike, he never suffered a recurrence of the malady.

It was during one of his mountain rambles that Galen Clark came upon the Mariposa Grove in May of 1857. Having toiled up the slope of a divide with the South Fork of the Merced flashing in its ravine far below, he paused at the summit for rest. Upon gazing around, to his amazement he was greeted by an immense tree. He immediately recognized it as of the same variety and genus as the mammoth trees of Calaveras which had so astounded the world subsequent to their discovery in 1852, and which were, supposedly, the only trees of their kind in existence. A cairn today marks the spot where Galen Clark caught his first glimpse of the Sequoia, and this first majestic shaft upon which his eyes rested in wonderment bears his name carved on a slab of granite hardly more enduring than the tree itself.

Though not alone in this discovery, it is quite certain that Galen Clark was the first white man to thoroughly explore the Mariposa Grove and to make it known to the public. According to his own testimony he was accompanied by one Milton Mann. “A few days later I was in the lower portion of the Grove,” writes the discoverer in Foley’s Guide Book, “and since the Grove was situated in Mariposa County, I named it the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees.” It is not certain, on the other hand, that Galen 40Clark and his companion were the first white men to walk through the Mariposa Grove. The dauntless prospector, undoubtedly, had also traversed this region. In his search for the imprisoned metal that seemed to cry out to him for liberation all of this hitherto unbroken solitude had become familiar ground to his feet. But if any gold-seekers beheld the Mariposa giants earlier than 1857, the discovery died with them.

It is sometimes claimed that one R. Hogg, a hunter employed by a water company to keep its camp supplied with venison and bear meat, discovered the Mariposa Grove in 1855. While in the pursuit of his calling, he came upon three trees of a different nature from any others in the forest. This he reported to Galen Clark and other acquaintances. Later, in the summer of 1857, and following the discovery of the Mariposa Grove, Galen Clark came upon the three trees reported by Hogg in a gulch about one-half mile southeast of the Big Tree grove. The largest of these stragglers, to which Hogg accredited a circumference of more than ninety feet, was so badly burned by a forest fire in 1864 that it was afterwards blown down during a storm. The other two eventually fell victims to the axe.

In April of his forty-third year (1857) Galen Clark settled on the South Fork of the Merced. He had visited Yosemite in 1855. Therefore, it was not without foresight that he staked out his claim beside the trail running from Mariposa 41to Yosemite in the year that the Mann brothers completed it. He selected a spot near the lovely expanse of the Wawona meadow which lies in a basin-like depression encircled by rolling mountains clad in forests of sugar pine that are no more. He built a crude log cabin, thus making the beginning of the white man’s Wawona.

It was not long before his visions of a teeming traffic that would some day wend its steady way before his door en route to the Yosemite became a reality. At first small straggling parties came at lengthy intervals, then larger groups, and finally a steady stream of eager travelers who desired to see the glories of Yosemite began to pass his way. His establishment, too, kept pace with the increasing travel. It varied from canvas and log to tolerably pretentious buildings as the seasons went by. With the advent of the sixties it was known as Clark’s Station, and was the heart of activity in this backwoods country. By this time a trail connected Clark’s with the Mariposa Grove. So impressed had the discoverer become with the importance of his find that he had built a good horse trail of four miles in length, thereby making the wonder trees of the Mariposa Grove more accessible to the world.

A trip to the Yosemite in these early days involved much of hardship without reward; much heat and dust and fatigue in the hope of enjoyment. A ninety-two mile stage ride was necessary before reaching Mariposa and an additional sixty 42miles on horseback. The first night of the horseback journey usually found the traveler at Clark’s, the second amid the solemn immensity of Yosemite’s granite cliff and domes at Black’s, the first structure in the Valley pretentious enough to be styled a hotel. Real enjoyment did not come until Clark’s was reached. Here the traveler had arrived at the outer edge of the civilized world and an atmosphere of romance surrounded the rest of the way. Europeans and New Yorkers were prone to class the trip in the same category as an expedition to little-known Tibet, and the friends of those who were determined on making it urged that such adventurers, before they left draw up their last wills and testaments. Nor is it to be wondered at that tourists returning from Yosemite after such a journey should speak vaguely of “obstacles and difficulties overcome and represent themselves as having a kind of undefinable claim to the character of heroes.”

Everyone who passed over the Mariposa trail carried away a pleasant memory of Galen Clark’s quaint wayside inn and long remembered its proprietor. The generous hospitality that he extended never failed to win the admiration of his guests. Even celebrities from abroad paid him tribute whenever they chanced to speak of him in later years, and always remarked that he had made them feel at home beneath his roof. The poor as well as the rich held him in esteem. No weary wanderer, no matter how low his fortune 43or how humble his pack, was ever turned away hungry or unrested. All were equally welcome, for he shared his loaf with Indian and white alike. Indeed, the natives in the country around loved him for his kind and gracious ways, sought his advice in council, and called him “Father Clark.”

The early guide books that tell of these incipient days of pilgrimages to the Yosemite rarely neglect to remark about the evenings spent about the open campfire of this simple, upright, kindly man. They tell how he presided over the social converse of the evening, how he narrated many a mirth-provoking anecdote, freely exchanging wit and wisdom, and all the while never indulging in boisterous laughter. They allude to those trifles which memory often cherishes—“the slight intonations of his voice indicating that something mildly sarcastic or funny was coming.” Lastly, they usually conclude with a picture of the great sugar pines, one hundred and fifty and two hundred feet high, solemnly standing guard, the files of their fellows extending back into the mystic blackness of the forest, the foremost calmly looking on the happy scene, their shadowy clusters of needles brightening and glowing in the flickering firelight.

Yet these noble qualities which Nature had planted in his being with such munificence unfitted Galen Clark as an inn-keeper. Business was too foreign to his temperament, and he was too utterly self-forgetful to win success. His friends 44multiplied fearfully and wonderfully, but fortune was unkind to him and led him into debt. So low had his estate fallen by 1869, when the Mariposa County survey was made, that he deeded half his Wawona property to one Edwin Moore. A few years later he borrowed money with which to make extensive improvements. These proved so unfortunately planned that foreclosure resulted. Again Galen Clark faced the most discouraging ordeal that can come to man—the making of a new start in life.

Until the late seventies the Mariposa Grove was accessible only by foot or horse. The beginning of the seventies witnessed the completion of the Mariposa road to Clark’s. In 1874 Washburn, Coffman, Chapman and Company were granted permission to extend the Mariposa road to Yosemite, with the privilege of collecting a moderate toll as compensation for its construction. This road, which is now known as the Wawona Road, reached the Valley in July of 1875. Its completion was celebrated in Mariposa in the true holiday manner of the early Californian. Bands and bluster and bunting were the order of the day. One prominent citizen of the community delivered a flowery oration and with an air of great electrical effulgence heralded the event as the dawn of a new era. Indeed, returning travelers from Yosemite could no longer lay claim to the laurels of heroes, for the journey was now considerably shorn of its “terrors.” 45During the spring of ’78 or ’79 the present road from Wawona to and through the Big Trees was built. The opening through the Wawona Tree in the Grove was made in one of these years and vehicles began to carry the curious of the world through this living tree. Clark’s Station was purchased by the Washburn Company in May of 1875, and with the advent of the eighties the present-day Wawona had seen its birth. Clark’s had become but a memory.

Contrary to popular opinion, the quaint Log Cabin which is so redolent with the breath of the fifties was not built shortly after the discovery of the Mariposa Grove. It was built much later, too late, in fact, to pose as “Galen’s Hospice” or to satisfy the lovely legend that it sheltered from the stormy blast wanderers who found themselves far from civilized habitation or human succor. Sentiment would fain preserve this myth. However, truth is firm and in all honor it must be stated that this cabin was not erected until 1885, and that it has never given shelter save to curios and their merchants. The report of the “Commissioners to manage the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees” of 1886 forever proves how palpably against the weight of authority this tale is. “Last year,” the report states, “a comfortable and artistic log cabin was erected at a central point in the Grove ... and ornamented by a shapely, massive chimney with 46a cavernous fireplace guarded by the traditional crane and pendant kettle.”

The first curio dealer to occupy the Log Cabin was “Old Cunningham.” This quaint character made his curios in a hollow tree with the aid of a jig-saw and tourists prized his wares the more knowing that they were made on the spot. When his purse was fat “Old Cunningham” would ride to Wawona to a saloon called the “Snow Plant,” where he was wont to present the bottle and spin yarns. Hutchings left posterity a delightful penciling of this old fellow. “The coach generally halts at a large and deliciously cool spring near the Cabin, where those who have come to spend the day will probably take lunch. Here, too, we shall have the pleasure of meeting Mr. S. M. Cunningham, who knows every tree by heart, its history, size, and name, and can tell you more about them in ten minutes than any man could in an hour (as is the usual case with such wags). I can see his bright and genial look, watch his wiry form and supple movements while I write. There is one thing especially noticeable about Mr. Cunningham—he is never discouraged and sees always the bright side of things, so that when a storm is swaying the tops of the trees until they bend together, he can listen interestedly and tell you laughable incidents until your sides ache.”

With the waning of the gold excitement and the waxing of a stable Statehood, those who were 47laying the foundations of the State began to turn their faces toward the future. Gradually they came to see the need of treasuring some of its natural heritages. They recognized the fact that California had been lavishly favored with great natural wonders. Nevertheless, they came to realize also that she was not so rich in these as to be careless or neglectful of their preservation. They likewise perceived, these far-seeing ones, that although California possessed all of the Giant Sequoias, they were the most perishable of all her treasures if left without protection. Destructive humanity can little change the sublime granite forms of Yosemite. They will always remain unspoiled, and mankind can hardly mar them more than could the clouds that hover about their summits or the butterflies that flit about their bases. It is true that man may plow Yosemite’s meadows and cut down wildflower gardens that have never known a mower. He can destroy its clusters of trees, rob Mirror Lake of its reflective charm, stop the flow of its waterfalls. All this he can do. But however much he tries he can but little alter or disturb the majestic repose of its rocks. Yet he can lay low in a single day a Sequoia that waved its arms to Sierran winds when the Carpenter of Nazareth was born. In one short season he can reduce a hallowed Sequoian grove to an expanse of blackened stubble where only charred stumps remain to mark where trees once stood and “looked at God all day.”

48

Fortunately, however, these builders of a commonwealth saw the light in time. Nor did they wink at it. Hence, the Mariposa Grove came to be made safe from the axe through seasonable legislation and was spared the fate that soon befell other Sequoian groves at the hands of greed and commercialism.

Fortunately, again, Galen Clark was appointed Guardian of the Mariposa Grove by the Governor. The choice was well and wisely made. In fact, when John Muir said, “Galen Clark is the sincerest tree lover I ever knew,” he spoke with fine truth and spirit. Never will Yosemite look again upon the likeness of such a man. In the performance of his duties as guardian of the Yosemite Grant he was not found wanting and proved himself sterling by every standard incident to human nature.

In 1864 when kinsmen in their bitterness and hatred were destroying one another, Senator Conness in behalf of certain influential citizens of California introduced a bill into Congress and the law-makers of Washington paused for a moment in the prosecution of the Civil War to pass the Act which granted to the State that “cleft or gorge in the Granite Peak of the Sierra Nevada Mountains ... known as the Yosemite Valley with its branches and spurs, in estimated length fifteen miles and in average width one mile back from the main edge of the precipice on each side of the valley ... and the tracts embracing what is 49known as the ‘Mariposa Big Tree Grove,’ not to exceed four square miles....” In addition to this the Act stipulated: “the said State shall accept this Grant upon the express conditions that the premises shall be held for public use, resort, and recreation and shall be inalienable for all time.” President Lincoln approved the Act a few days before he made his famous speech on the field of the battle that broke the Southern blade. Shortly after this Governor Low of California formally issued a proclamation accepting the Grant. In it he warned all persons against willful and malicious trespassing and made it a misdemeanor to injure or destroy any of its treasures. In accordance with the terms of the Act, the Executive of California then appointed eight Commissioners to manage the Valley and the Big Tree Grove, naming Galen Clark as one of them. On the second of April, 1866, the State Legislature made formal and legal acceptance of the Grant and clothed the Commissioners with the necessary power to make such regulations as were requisite to its administration and control. At this time the Legislature also authorized the Governor to appoint a Guardian to take active charge of the Grove and the Valley. A small appropriation of two thousand dollars was made for the purpose of making improvements during the ensuing two years and an annual salary of five hundred dollars was voted the Guardian.

50

Life is not always a picking of flowers; often it is a plowing of meadows strewn with hidden rocks. The latter proved to be the lot of the Commissioners in connection with the Yosemite, for their progress was blocked by the hostility of settlers who refused to relinquish their claims. Litigation resulted and the Commissioners encountered only censure and antagonism in their attempts to make of the Yosemite a playground for the people. Happily, they were not so handicapped in their management of the Big Tree Grove, yet here, too, they had difficulties to contend with.

Chiefly among these was the problem of human vandalism. Constant vigilance was necessary to guard against those who seemed to take an insatiable delight in destroying all within their reach. Truly, the besetting sin of all “pilgrims” the world over is their unquenchable lust for “specimens.” Like priests of the Capuchin Convent who “unfailingly show some memento of a saint—a bone of his body, a thread of his garment, a lock of his hair, or a drop of his blood—before they extol his miracles,” the “pilgrims” who journey to Nature’s shrines must, at all hazard, carry away some bit of the shrine to awaken the wonder of the rustics at home. Or, if they are thwarted in this, it becomes imperative for them to inscribe their poor little names in some convenient place on the shrine so that all who run may read. What a pity some 51justly wrathful Sequoia cannot fall on some of these defamers and crush their “eyeballs into dust,” thereby intimidating them and their kind into forever desisting from such acts.

The Commissioners were plagued with vandals of yet another sort—the camper and the sheep-herder; the one starting forest fires through negligence, the other purposely to insure better grass for his “hoofed locusts.” In 1889 the Grove was threatened with disaster. A fire, started because of a camper’s carelessness or through the deliberate design of sheep-herders, secured sovereign possession of the surrounding forest and in one place invaded the Grove itself. In a few days the entire annual appropriation was used in saving the Grove from the angry flames. When their fury was finally conquered, black scars that only time could obliterate remained. It was this memorable fire that consumed the Lone Giant, the largest decumbent monarch in the Grove.

Since the Commissioners had no control over outside forests bordering on the Grove, this calamity indicated the need of building a fireline to arrest the progress of future conflagrations. The necessity of clearing the Grove of its dense masses of inflammable undergrowth was also made apparent. This growth not only obstructed a view of the older trees, but it rendered them inaccessible for close inspection. It also made for poor reproduction by depriving seedlings of light. It choked and starved the younger trees, while 52it robbed the patriarchs of their much needed moisture and hindered their growth. Hence, to render these harmful features negligible, the Commissioners decided to clear the Grove of its underbrush. The appropriations of the next five years were used toward this end. By 1895, all the acreage within the ambit of the Big Tree Grant had been treated to the brush scythe and the grubbing hoe, and the fire menace reduced to a minimum.

No less worthy of attention are the extensive additions and improvements made during these years upon the roads. Each of the main clusters of Sequoias was rendered accessible and travelers could make a complete tour of the Grove viewing its principal wonder trees from the stage, as they do today. The State had received the Grant approachable only by trail. In an amazingly short time, considering the meagerness of appropriations, the State had rendered the Grove accessible to other than hardy travelers. Young and old, the physically fit and the infirm, could now enter it with comfort and safety. In all fairness it must be conceded that the State had made the Mariposa Grant more suitable for the particular use for which it had been appropriated. The Commissioners had administered the Grove for the good of the greatest number. They had taken positive steps to protect it from the carelessness of the thoughtless and the wantonness 53of the ignorant. Unquestionably, they had proved scrupulously careful in their administration of the trust imposed in them.

Yet even so commendable an accomplishment as this only aroused a storm of criticism. The removal of the fire-inviting underbrush shocked the nerves of sentimentalists who advocated the preservation of the Mariposa Grove “in the condition in which it won the admiration of its discoverer and appealed to the enthusiasm of the world.” They lamented over the fancied catastrophe. They fell into near convulsions over the thought that the virginal beauty of the Grove was no more, because its “flowering shrubs” had been grubbed out. Even the Century Magazine took up the bodeful cry. Joaquin Miller’s statement that he had travelled from Babylon to Jerusalem “without seeing so much as a grasshopper, or a bird, or a blade of grass in a land that was once an Eden” was quoted as a prophecy of the Grove’s condition in the near future if these “destructive tendencies” continued. Alexander, they pointed out, mourned because Greek ivy would not grow on the tower of Babel and inferred that such would be California’s lot when her eyesight sufficiently improved to see the need of enhancing the grandeur of her Sequoias by garlands. And all the while they failed to see the irony of their plea. They did not know that sentiment, like ivy, can cling to a very flat surface.

54

Nor is this all that the Commissioners accomplished. To their list of achievements must be added yet another. In order to make the Grant of 1864 a treasure that “all shall share and none shall be the poorer for sharing,” they warred against unscrupulous commercial enterprises. Hawkers continually pressed forward their schemes in honeyed words to make travelers the victims of innumerable petty charges and vexations. However, the Commissioners who were all men of high principles would have none of them. Concessioners who proved unprincipled in their treatment of tourists were summarily deprived of the means with which to accrue further ill-gotten gains. In all truthfulness it can be stated that throughout the entire forty years of State control[1] the various Commissioners never sullied their hands in graft. Though they received not a penny in salary and often laid out considerable sums to swell the meager appropriations of the State Legislature, their office was never used for the purpose of gain. In short, they carried a trusteeship that concerned the high honor of the Commonwealth of California in a manner which justifies the pride of the people.

In all this glorious work Galen Clark, as Guardian, stands head and shoulders above his colleagues. He had that desire to serve without 55its selfish qualities. Not inspired by the love of fame and reputation, he did not toil for self-aggrandizement, like many men. He considered the interest of the people higher and purer than that of the individual. It was this interest that he ever held paramount, that he always best served. To him the highest patriotism was expressed by the man who thought not of honor of self or of individual reward, but who lost himself in the larger and dearer interests of the Commonwealth; who so loved it for its own sake that he was content to be forgotten. In this respect Galen Clark succeeded in a manner so striking that it deserves the name of art, not of artifice. He is practically unknown today. Yet he rendered the people of California, and even of America, a singular service.

“As Guardian he enjoyed a longer contact with the management of the Grant, off and on, than any other single individual. He was reappointed again and again by succeeding Governors as Guardian, and after twenty-four years of service in this capacity, he voluntarily retired, carrying with him the respect and admiration of every member of the Commission, of all the residents of the Valley, and of every visitor who enjoyed the pleasure of his personal acquaintance.”

The tribute paid him on his retirement in 1897 by those with whom he was so long officially associated is worthy of full quotation:

56

Whereas: Galen Clark has for a long number of years been closely identified with Yosemite Valley and has for a considerable portion of that time been its Guardian; and

Whereas: He has now, by his own choice and will, relinquished the trust confided in him, and retired into private life; and

Whereas: His faithful and eminent services as Guardian, his constant efforts to preserve, protect and enhance the beauties of Yosemite; his dignified, kindly and courteous demeanor to all who have come to see and enjoy its wonders, and his upright and noble life, deserve from us a fitting recognition and memorial; now, therefore, be it

Resolved: That the cordial assurance of the appreciation by this Commission of the efforts and labors of Galen Clark, as Guardian of Yosemite, in its behalf, be tendered and expressed to him:

That we recognize in him a faithful, efficient and worthy citizen and officer of this Commission, and of the State; that he will be followed into his retirement by the sincerest and best wishes of this Commission individually, and as a body, for continued long life and constant happiness.

Galen Clark did great things, but apparently fame accompanied him to the grave. Few know of him today. One of the most kindly of men, he had a simplicity so intense that at times it appeared ridiculous to men of sense and candor. Never offending by superiority, modesty composed the very fabric of his being. To be rather than to appear was the ruling passion of his long life. Having an insuperable aversion for bluster and bombast, he talked about himself rarely, and then only with the greatest of reticence. It was only after much persuasion on the part of friends that 57he was induced to write his charming and authoritative account of the Indians of Yosemite in 1904. Doing nothing for the sake of personal display, he never forced himself into the limelight. Unobtrusive and unpretentious, he had all that unaffected humility that some believe to be the essence of Lincoln’s greatness.

No account of Galen Clark would be complete if it failed to touch on his love of Nature. “He was fond of scenery,” testifies John Muir, “and once told me that he liked ‘nothing in the world better than to climb to the top of a high ridge or mountain and look off.’ Oftentimes he would take his rifle, a few pounds of bacon, a little flour and a single blanket and go off hunting, for no other reason than to explore and get acquainted with the most beautiful points of view. On these trips he was always alone and indulged in the tranquil enjoyment of Nature to his heart’s content.”

Few, indeed, have been more sincere in their love of Nature. He loved not only all her moods, both beauteous and terrible, but all her forms from the lowliest flower in the dust by the roadside to the loftiest of Yosemite’s cloud-caressed cliffs. But he lacked the power of expressing his affections. Like Muir, he “read the great book spread out before him;” unlike Muir, he was not gifted with a magic pen. Probably he was too sensitive to his poverty of language to attempt to describe the fairy-like beauty, the rare delicacy, 58and the wondrous tints of an Alpine blossom—“that beautiful creature that catches the smile of God from out the sky and preserves it.”

Twenty summers in the Yosemite formed in Galen Clark an attachment for the Valley that was deep and lasting. Nearing the sunset of his life, like the patriarchs of old, he dug his own grave in the little cemetery near Yosemite Falls. With his hands he hewed his own tombstone from one of the granite blocks the elements had plucked from the cliff over which the snowy flood of the grand Yosemite Falls descend sonorous, and soft, and slow. Taking up a few seedling Sequoias from the Mariposa Grove, he transplanted them at the four corners of his last resting place so that they would shade the grave of their blessed benefactor in the years to come. A man of great age, he must have brooded on death and become familiar with its mystery so that the end did not come as a surprise.

One day in 1910, at the age of ninety-six, the end came and in sorrow and in silence all that was mortal of Galen Clark was laid in the sacred earth, his kindly soul passing on to where, beyond the booming voice of the great fall he so loved, there is peace.

THE Mariposa Grove belongs in the category of the world’s impressive wonders. It presents the most remarkable exhibition of the Sequoias growing between the American and the Kings Rivers and displays Nature’s finest handiwork on the fraternity of the king of all trees. It contains the essence of the most imposing qualities of the Sequoia and is unlike any other grove in its very compactness. Concentrated in its small extent are trees in every phase of development from nurseries of tender seedlings obtaining their feeble hold on life and groups of graceful saplings not half arrived at the maturity of treehood, and just disclosing their impatience to be kings, to venerable patriarchs that are numbered foremost in the world of living things—giants so freighted with age that they exemplify Doctor Johnson’s famous metaphor, “and panting Time toiled after him in vain.”

The Mariposa Grove is superior to other Sequoian tracts in its accessibility, lying as it does in a shallow, crater-like depression near the top of a forested ridge at an elevation of 6,000 feet above the sea and a distance of sixteen miles as the crow flies from the Village in Yosemite Valley. This ridge, upon which the Grove is 60situated, runs in an easterly direction between Big Creek and the South Fork of the Merced, having as its culmination Mt. Raymond, a rocky promontory upon which the snow lingers even in July.

The Grove is approachable over the Wawona Road which winds upward along the south rim of Yosemite Valley. After passing southward in a meandering course through twenty-seven miles of Park forest, the road drops to Wawona from where it again ascends 1,500 feet within eight miles before reaching the portals of the Mariposa Grove. Once within the Grove, but a comparatively brief period of time is required in which to review its salient features. With little effort it may be completely explored and studied. So harmoniously are its wonder trees disposed within the utmost smallest space that all of them may be viewed from a passing vehicle. In fact, even the most cursory journey through the Mariposa Grove will suffice to give an impression of the singular, solemn dignity of the Sequoia.

Possibly much of the world-wide fame of this Grove is due to the fact that it has been brought the nearest to civilization of the several Big Tree groves. Yet interest in it should not spring merely from such a consideration, for it lies in happy proximity to the grandeur of Yosemite’s cliffs and domes. Indeed, it is as distinctive a feature of Yosemite National Park as the Valley itself. Time was when the importance of the Mariposa 61Grove was little if at all recognized. In the last decades of the nineteenth century the Calaveras Grove held the center of the stage. The latter was then the most accessible. Because of this it became the Mecca of naturalists and celebrities of the day who made pilgrimages across the continent in order to visit it. Therefore, the Calaveras giants loom large in the earlier literature of the Sequoia. But with the passing of the stagecoach and the hitching post—with the coming of the “winged wheels” and the “iron horse,” the Mariposa Grove ceased to bloom unseen. Instead of the Calaveras Grove it became the more easily reached. Inevitably the pendulum of popularity swung toward it and yearly the tide of travel that flows its way increases.

The tendency to wander into the wilderness that obtains in these feverish times is advancing the popularity of the Mariposa Grove. Mankind is coming more and more into sympathetic contact with Nature. Yearly thousands of over-civilized people are discovering that nothing so renews the health of the body, so refines the mind, so affords a margin of leisure for the soul, or so has the power to quiet the “restless pulse of care” as communion with Nature. They are discovering that real recreation and enjoyment are not found in crowded cities or fashion-hampered hotels. As a result, unspoiled woods and mountain solitudes, brawling brooks and soundless lakes, flowers and stars, rosy dawns, 62sunset golds and twilight purples are fast becoming the wealth of nations. All this is glorious and full of promise. It lends a happy tone to the times. Truly, if it persists in increasing, the Mariposa Grove is destined to enjoy a tremendous tomorrow.

The Grant made by Congress in 1864 really embraced two distinct groups of the Giant Sequoia. Because these approach within but a few yards of each other, they have come to be looked upon as a single body. The Upper Grove, according to Whitney, contains 365 trees of a diameter of one foot and over. This makes, as the old guide books were wont to point out, “a tree for every day in the year.” The Lower Grove is smaller in area and contains but 182 trees, which are more scattered than those of the Upper Grove. In both groves there are hardly more than 125 Sequoias over 40 feet in circumference, yet these in themselves are so imposing that to view them is compensation for a journey half the circuit of the globe.

The road enters the Lower Grove, describing a figure eight in passing through it and the Upper Grove. The Sergeant of the Guard and the Four Sentinels guard the gateway. Their bright color and port, rather than their size, at once attract the eye. Soon other monarchs, among them the prostrate Father of the Forest, are passed. Then the Grizzly Giant, standing alone in the grandeur 63of its own solitude, chains the attention. Upward wanders the road, passing from one marvel to another. Each seems to surpass its predecessor, and finally, when the road passes through the Wawona Tree, it seems the chief wonder of them all. But when this Highway of the Giants winds back again to the Log Cabin, the traveller learns that the real wonder has been reserved for the last. Here he will find himself in the midst of a most magnificent grouping of Sequoias. Over half a hundred are within sight of the Cabin. But not until, after examining one after another, letting the eye roam over their fluted columns and upward into the blue-green depths of their far-away tops, walking around some and into the enormous hollows of others, climbing up the sides of still other prostrate trunks and stepping them off from end to end, will a proper realization of the immensity of the Sequoia be possible.

The more remarkable trees of the Mariposa Grove have received names to individualize them. But even this practice of late has been carried too far. The names of states, cities, and persons have been indiscriminately tacked to trees that were on earth when the stones of Rome were laid. That such comparatively trivial and frivolous designations so inconsistent with the grandeur and nobility of the Sequoia should be permitted is amazing and regrettable. It detracts seriously from the finer appreciation of the tree and renders its groves “freak museums” which are looked 64upon with a “Barnum eye” as merely “side-show curiosities and big things.” Assuredly, such a practice is to be unreservedly condemned.

Whitney attempted to avoid just such a result as this by distinguishing the greater Sequoias by numerals. However, the undesirability of such a method is at once apparent when pressed into service. Such featureless monotony as “Number 15, fine, sound tree; Number 304, largest and oldest tree in the Grove; Number 262, half-burned at the base,” and the like (as Whitney recites in his Yosemite Guide Book) is produced. Obviously, the trees must be individualized by names. But why attach a name such as Andy Johnson to a tree that saw the light of day when Pompeii was destroyed? Affixing names of such temporary notable figures of the day to a Sequoia savors almost of ticketing the name for an “adventitious immortality.” At any rate, whether it be the tree or the man so honored, probably either would live as long in memory without the connection. If a Sequoia must be labeled, let some striking attribute of the tree itself be the governing factor in selecting the designation.

Foremost of the Sequoias in the Mariposa Grove is the Grizzly Giant. It is among the most massive-stemmed trees of the world and ranks with the oldest inhabitants of the earth. Yet a mere statement of its size little serves to convey an adequate impression of the tree. Measurements are, after all, only relative criteria, at best. As 65well give the tailor’s measurements of Lincoln as an index of his greatness as to try to convey the fascinating immensity of this tree by saying that it is 204 feet high and 31 feet in diameter at the ground. Its stockiness is truly remarkable. Its sturdy trunk tapers upward so slightly to the first great limb—reputed to be six feet in diameter; the size of a mature pine—that the diametric variance is almost imperceptible. Nor is its base excessively expanded. No more, really, than is necessary for strength. In fact, it seems almost too slight an expansion to serve as a diagonal brace or instep for the support of such a gigantic structure upon the earth. Consequently, the diametric measurement of the Grizzly Giant at the ground justly signifies its enormous bulk. Yet even this cannot be accurately obtained for its base has been so badly gnawed by flames that a true measurement is not possible.

Several Sequoias press closely upon the Grizzly Giant in girth. The Lafayette Tree is easily its counterpart, having a ground diameter of 29.4 feet. But in this case the swell at the base is excessive and the trunk itself has less than two-thirds the diameter of the Grizzly Giant. The Columbia Tree even exceeded the Grizzly Giant in girth and must have measured at least 110 feet in circumference before fire claimed half its base. Viewed from the Cabin it is extremely imposing and almost as grand and picturesque in its old age as the Grizzly Giant. Standing on a steep 66slope, its stem appears to be fully as massive as that of the patriarch of the Grove, while its great elbowed limbs and its high top, “bald with dry antiquity” and scarred with tokens of old wars, vest it with a venerable charm. However, a scramble through the dense brush on the up-hill side reveals a large burnt hollow in which a dozen persons could comfortably stand. If sawed close to the ground its stump would be shaped like a crescent moon. A tape stretched around it and across its concave surface would record a diameter of 25.6 feet. The Washington Tree is a foot less in girth at the ground than the Grizzly Giant, yet measured 10 feet above the ground its trunk is a few inches larger in diameter, being 20.7 feet. Nevertheless, it tapers far more and is not nearly so imposing in its pillar-like stateliness as the tree that presides over the Mariposa Grove.

After all, mere figures have their limitations. They are not expressive of Sequoian size. This may be due to the columnar character of the Sequoia’s trunk. It rises smooth and unbroken by protuberance of any kind for a hundred to a hundred and fifty feet. Vastness is so artfully given emphasis and completeness that the whole is not a monstrosity. Symmetry is so perfectly achieved that there is no straining for enormity. What would be a commanding height for a building on a flat level surface appears not out of the ordinary in the Sequoia. This is perhaps why a 67first glimpse of the Sequoia is sometimes disappointing. Examination and meditation are necessary before the grandeur of the tree “grows” upon the observer. Then he is filled with a feeling of awe that no grandeur of architectural pile could possibly inspire.

The Mariposa Grove possesses the tallest of the Sierra Sequoias, the Mark Twain Tree. This magnificent specimen lifts its proud head 331 feet into the sky. Thus, it would reach nearly two-thirds of the way up the lofty Washington Monument and would over-top the dome of the Nation’s Capitol. Yet those who gaze upon it for the first time depart doubting. Seeing is not believing. Its appearance is anything but that of the tallest Giant Sequoia on the globe. Nevertheless, the measurement is accurate and authentic and must stand.[2]

Other Sequoias rank close seconds to the Mark Twain Tree in height. The Captain A. E. Wood, with a height of 310 feet, is not far behind. The Columbia, 294 feet high, the Nevada, 287 feet, and the Georgia, 270 feet, are all exceptional trees. In fact, a score of others could be enumerated before the imperial Queen of the Forest would be reached, whose 219 feet of trunkage place it within the average height of the Giant Sequoia.

Most perfectly formed of the Sequoias of the Grove is the Alabama Tree. The pioneers called 68it the “Pillar of the Temple.” It has developed under full sunlight and is magnificently balanced in all its proportions. Truly, it is one of the finest examples of “Nature’s forest masterpieces,” as John Muir was wont to designate the Sequoia. Fit to support any temple, it stands marvelously perfect, unmarred by fire, untouched by disease, undisturbed by the violence of the elements. Centuries have passed over it, centuries that have noted many disasters in the march of civilization, and yet it has remained free from accident. Its heroic stem is as roundly perfect and as regularly tapered as though turned in a lathe. Unbroken by a limb upwards of nearly two hundred feet, with an instep that adjusts itself to the mass it supports with elegant finish, it discloses a trunk with deeply and widely furrowed ridges not unlike a pillar that Phidias might have fashioned. But no pillar ever conceived by man bore a tint more ravishing or a luster more superb than this. When spotted with shifting patches of golden sunlight, its cinnamon-reddish trunk would put to shame the richest colorings of Numidian marble.

Nor has any pillar of stone ever supported a more exquisite structure than the crown of this Sequoia. Possessed of almost an artificial finish, it is a gracefully trimmed, singularly perfect dome. The supports of this crown leave the trunk in a woody wilderness of huge arms, wild in ungovernable expression, knotted and confused as those of giants who toss their arms in anguish. 69These great limbs, regal-hued in rose and purple, dissolve themselves abruptly into masses of stumpy branchlets which in turn spray out into a soft film of deep blue-green foliage. Indeed, it is impossible to distinguish against the skyline exactly where this arch described by the foliage ends and where sky begins. So subtile are the edges of this crown that they appear to melt away into the heavens. Yet more wonderful is the flame-like semi-halo visible along the crest of this tree just after a rain. Ruskin noticed this light on pine trees. “The whole outer crown,” he states, “becomes a thing of light, dazzling as the sun itself, for every minutest needle is bedewed and carries a diamond, as if living among the clouds it had caught a part of their glory.”