Title: Nature's year

The seasons of Cape Cod

Author: John Hay

Illustrator: David Grose

Release date: August 1, 2025 [eBook #76613]

Language: English

Original publication: Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc, 1961

Credits: Steve Mattern and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

[Pgs 1-3]

NATURE’S YEAR

A PRIVATE HISTORY

THE RUN

NATURE’S YEAR

[Pg 4]

[Pg 5]

The Seasons of Cape Cod

ILLUSTRATED BY

DAVID GROSE

1961

Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Garden City, New York

[Pg 6]

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 61-8166

Copyright © 1961 by John Hay

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

[Pgs 7-8]

For Kristi, Susan, Kitty, Rebecca, and Charles Mark—

with me on this journey through the year

[Pg 9]

July 11

A Start on Cape Cod—An Entry—Other Lands within the “Narrow Land”

August 25

A Wild Home Land—The Musicians—A Walk with an Oven Bird—Toward the Sea

September 47

Youth on the Move—An Open Shore—Chipmunks

October 61

Where Is Home?—The Field of Learning—Colors of the Season—The Last Day in October

November 81

The Seed in the Season—The Clouds—The Inconstant Land—The Dead and the Living

December 97

An Old Place, an Old Man—Night in the Afternoon—Two Encounters

January 113

Exposure—Ice on the Ponds—Contrast and Response

February 127

Secrets in the Open—The Sea in the Ground—Need—Death, Man Made

March 143

Restless Days—An Extravagance—Interpretation—Response

April 161

Deeper News—April Light—“Frightened Away”

May 173

Declarations—Facets of Expression—Travel

June 187

The Garden—Room to Spare—The Binding Rain

[Pgs 11-12]

[Pg 13]

I drove to Cape Cod with travelers from everywhere. I came to this narrow peninsula over the blistering, insatiable roads of America with the summer crowd—in my shirt sleeves, with dark glasses to protect my sight—conscious of almost nothing but cars, and casualties ... our migrations have them too, like the birds and fish.

I saw an accident so terrible I could not describe it. Machines were flung into the air and smashed. A life was tossed away, a human being crushed like a doll. Human relationships were pathetically severed by the brutality of chance. Then we were allowed to go on—travelers racing down the highway through the blood-boiling heat of the sun. We come in with speed and we go away with speed, and we are both afraid and desirous of it. The human run in its relentless self-absorption seems more abstracted than any other natural force.

The resident population of Cape Cod is some 80,000, and in July the number increases to an estimated 250,000 or more, a kind of barometric rise that is equivalent to what is happening in the earth at large. After Labor Day, when the summer tribe has gone back to the cities, relief comes. You can cross the road in comparative safety. Then, something like apathy pervades the Cape, as if its diminished society were trying to recover from an encounter with enormous odds.

Now I am off the road and back on the 110-foot hill where we put our house—part of a ridge that runs along the glacial moraine about a mile back from Cape Cod Bay. Dry Hill was its[Pg 14] local name, and in fact, driving a well, we found a constant source of water only at 130 feet. This evening the yellow light runs liquidly through the oak trees and the pitch pines around us. I can hear the voices of some of my travel companions lifting from the shore, calling, pleading, protesting. A snatch of radio music comes in. A plane drones overhead. The warm air seems to breathe hard, as if to compete with human breath.

I often wonder, when I am back on the Cape again, whether I chose the right place in which to live. It looks bare and scrubby, lean and poor, in comparison with those lands to the north and west of us which are far prouder in their trees. It has been burned over, cut down, and generally abused by man, and most of its healthy trees will never attain full growth because of the salt spray that the winds drive over them in many storms. And the sea, for all its surrounding presence, seems a mere backdrop a great deal of the time, a flatness along the horizon, but it is indomitably there. All the winds, the plants, the shores, the contours of this low land, are influenced by it, and because of it we are carried out into a distance in spite of ourselves. The sea mitigates our insularity.

Cape Cod reefs out into the Atlantic. I saw our house when it was new as a ship above the trees. I imagined a voyage. I recognize that although there are some true fishermen here who sail the year around, the rest of us are summer sailors, with no lasting allegiance or commitment to the dangers of salt water. Yet the Cape provides space for whoever might take the risk or pleasure of finding it. The sea and sky are very wide. The winds blow in from all quarters.

The yellow evening lowers now, through the young, shining leaves of the oak trees, creating new recesses of darkness. Tides of fire hang above the water. There are snatches of bird song through the woods: a robin; the silver pealing of a wood thrush; a towhee; a whippoorwill, starting in on its over-and-over-again, the loud repetitious whistling that makes the night known even as the day hangs on. And finally faint stirrings here and there, easings down, last faint pips and trills before the dark. I am conscious of the tenancy[Pg 15] of nature, in which there is more putting forth, more endurance, more population, in fact, than any visitor or local man might ever begin to realize. The great world we live in is no longer one for hide-outs. If this makes for intolerable pressure and despair, it also brings much more into view. Local recognition becomes a general need, and there are more possibilities in it than we have been told. While the human race has been approaching three billions in number, and making ready to put its mark on the moon or hang its hearing aids off Venus, I seem to have spent many years missing, or unwittingly avoiding, almost as many lives and chances close to home. How can I begin to compensate?

[Pg 16]

I had decided to start this book in July, with the idea that this was the time embodying the full, crowded height of life—the noise, the color, the jostle of creatures in wonderful variety, just like that load of passengers getting off the boat at Provincetown to see the sights. The leaves are fresh. The motions of greed and fulfillment are in full course. Even so, I hardly knew what riches to snatch at first. In fact, another bold, heat-heavy day, with its crowds and its pride of accident, had the effect of making me recoil. I was muttering: “Slow down. Slow down. Why so thick and fast?”

On my way back from walking to the mailbox just now, I stepped off the road into the oak trees through which it runs, dropped the newspapers and the letters, watched and waited. I sat on the upper edge of a hollow where dappled shadows rocked lightly between the trees, on their gray trunks, and across the sloping ground. There was a pervading swish of leaves around me, an occasional stirring at the tree tops. I heard the slow, dragged caroling of a red-eyed vireo. Filtered light played on the low growth of sarsaparilla, hazelnut, huckleberry, and bracken, or dry land fern, with the brown floor of oak leaves in dead but useful attendance, holding moisture, shelter, and fruition in reserve.

The wood had a climate of its own, cooler, darker than the hot, damp, wide open world of road and shore. There are climates within climates, as there are worlds within worlds. Under the bark of a tree the beetle inhabits a place that has special atmospheric conditions differing from the woods outside it; and so it is with the[Pg 17] woodchuck in its hole, the ants in their hill. Any place, of whatever size, however endowed in our scheme of things with grandeur or insignificance, any home, may be greatly subtle in its variance.

A sweet, plaintive “pee-a-wee,” and a wood peewee, a neat little bird, black, light gray, and white like a phoebe, but with white wing bars, flew in quickly and lightly, to perch on a gray limb. The bird would tuck its head down, and then move it from side to side, looking for flying insects, repeating its song every five seconds or so. Its tail, not bobbing like a phoebe’s, twitched very slightly when its head moved. Then, in brief action, it fluttered out, caught an insect, and returned to its perch. These little flights covered most of the area around its tree, almost methodically. Once I heard the crack of its bill as it chased a fly almost down to the ground, halfway across the wood. It alighted on a new branch—to try out another base of action? But then another peewee flew in, perched, and sang at a far corner of the hollow, and the first one hurriedly flew back to its original perch as if it had been threatened and was making sure of its position. The wood seemed strung together by the intangible threads of their motion.

These were some of the ways by which a wood peewee follows its destiny, employing its chosen place, attending to minutiae, to duty and performance. This was appropriate use, measured necessity. And as the outer earth led to this part of the wood, and it in turn to the “micro-climates” within it, so the birds drew my attention to the insects. I had been bitten a little, just enough to remind me, in my enjoyment, that the place was not unnaturally hospitable; and there were unseen spider mites that would leave me some inflammations to remember them by. Now I searched the space above me, aware, through the flights of the peewee, of the flying life it pursued. Some flies hovered, rocking lightly in the air, and then swung abruptly to one side, or dropped away, buzzing insistently. Tiny midges, illumined by sunlight, waggled between the trees. Moths fluttered down briefly to touch the pale leaves they resembled.

So I had been filled, as I sat there, with a sense of employment.[Pg 18] I was part of a quiet, steady, structure of action. What better “security” could I find than that—learning, feeling, that a prodigious energy held all component parts in place and made them dance. In the neatness, discipline, almost detachment, of the bird’s little game as it pursued its subsistence, I saw the working out of natural law in numberless parallels.

Perhaps there was a law to be learned for me. If nature is more than just a background for human thought and endeavor, then it requires a special commitment, a stepping down, a silent, respectful approach. Otherwise we are liable to hear ourselves first, and be put off.

I have been given an entry, but not on my own terms.

[Pg 19]

To answer the question “Where am I?” seems not to be an easy thing. “Obviously” this is the vacation land of Cape Cod where the sun sends the bathers to the beaches and the rain drives them back inland to buy souvenirs, where the harbors are crowded with pleasure craft and the highways with cars—an area whose purpose it is to attend to human distraction. Yet right in the middle of it the action of a small bird reveals a land of its own; and how many others are there still unmet?

It is very strange to me that I have known so little about what was around me, and that I took so long merely to make some inquiries ... about a few names, a few alliances between living things, just enough to give me a hint or two about the growing we are never finished with. We live in a common realm about which we are still half ignorant and half afraid.

A little girl at the beach comes running through the shallow waters crying: “Something touched me, and it wasn’t Daddy!”

Later on, her mother wonders aloud if crabs bite. She picks one up and when she gets her answer, screams with pain and anger at all the “unnatural” and the unknown.

Just the other side of us is not only a bewildering variety but a space, which we have still to find, filled with an unfamiliar silence, or random sounds, seemingly disconnected motions, sudden flights that we witness out of the corner of an eye. When we only assign the word “purpose” to ourselves, it is hard to understand just what credit to give that which only stands and waits, or moves from one place to another. I sit on the beach, moving[Pg 20] a little away from a portable radio that a man has brought to assure himself of his continuous hold on human affairs, and look out over the hazy surface of the water, past a long border of waves that lollop on the sand. There is a large bird standing on a rock not far offshore. I know it as a great black-backed gull, a scavenger, a predator, which sometimes eats the eggs and kills the young of other species of gulls whose nesting islands it shares, and robs other birds of their food ... and that is about all I know, aside from having watched its splendid, easy flight. So it stands, and may stand, for an hour or more at a time, sea-surrounded, glaring out with expressionless yellow eyes. Is it digesting a heavy meal? Is it waiting for low tide so that its feeding grounds will be uncovered? Is it greedy, savage, lazy, and bold? All such questions are tentative. The subject is aloof.

Why is there so much hanging around and waiting, so much suspension in nature? It comes as an occasional surprise to us timekeepers. In the gull we suspect obliviousness, and yet it may be prompted by the demands of a space of water, light, air, stretching before and around it, in its being, of whose motion and sense we are scarcely aware.

We see very little. I am told that the very sands we sit on are full of minute organisms. The visible life, perhaps in the form of a few beach fleas, represents an extremely small percentage of the life unseen, a condition which has its parallel in the soil. But a short walk or wade along the shore can give you proof enough, without the need of a nip from a crab, that the tidal grounds are covered and circulating with life, a life which in its marine forms might seem small, simple, primitive, and unallied with much that we landed mammals can understand.

I cannot inquire much of the moon snail, blindly, slowly moving across the sands under the tidal waters, with its large foot feeling for a clam. It only reveals itself to me by outward acts and signs which do not seem to have much variety. A small hole, countersunk in a shell, is common proof that a moon snail has drilled in and then eaten the occupant. When you see a[Pg 21] “sand collar,” which this animal forms of sand grains and eggs, you know another side of its existence. Perhaps that is all there is to it—eating and reproduction—the round shellfish mindlessly carrying out its destiny. If it says anything at all to me it is only out of undeciphered darkness, silence, and original need.

A tiny, shrimplike animal hovers in the water, then darts over my foot, only describing itself to me by its quick motion, and that is all I know of it. It suddenly buries itself in the sandy bottom, where reflected sunlight makes golden nets, that stretch and tremble through the constantly flowing waters.

The tide ebbs. The sun starts to evaporate the moisture from the top surface of a big rock, part of a jetty that thrusts out from the beach. I see a number of dark periwinkles around and under an algae-sheathed, water-soaked branch that lies there, a source of food for these browsers and vegetarians. They are a common marine snail, used for human food in many parts of the world, and usually so numerous and well known as to be taken for granted. As the water recedes and sinks below the surface of the jetty, the sun beats down, drying the rock. Some of the animals stay under the shade and moisture of the stick, but more begin to move slowly away from it. When these travelers finally reach the edge of the rock, they start down its shaded face. Their dark, whorled shells, though an intrinsic part of them, are hoisted, moved around, almost in a full circle, seeming to slip loosely over their bodies as they move down. Their black tentacles, like antennae on insects, wave slightly on their snouts, and their slimy foot works slowly down. Their motion is a curious combination of probing, oozing, gliding, and at the same time, holding on, assuring the grip, with a kind of portentous caution. Since I can easily tip one off with my finger, I also feel a tenuousness about them, in their relation to this realm of tidal power with its constant displacements—but adaptability is probably a better way to think of it. They have lasted, in their loose wandering, through a period of time which we can only estimate. They have a special authority. As I watch them it seems to me that no other action is of any more[Pg 22] pressing importance during this moment in the scheme of things.

These personifications of motion, these strangers, have untouched lands of their own.

That silent sea at my side is colossal, inscrutable, and holds out no solace or advice. We only have our toes in, on a tiny section of its summer shore. Most of us barely touch its surface. Even so, it offers as much to a traveling human as to a snail. It is still an old space unexplored, and if we leave the vacation sands and set out on an afternoon’s sail, we may be following some need of wind and water in us, some unused acquaintance.

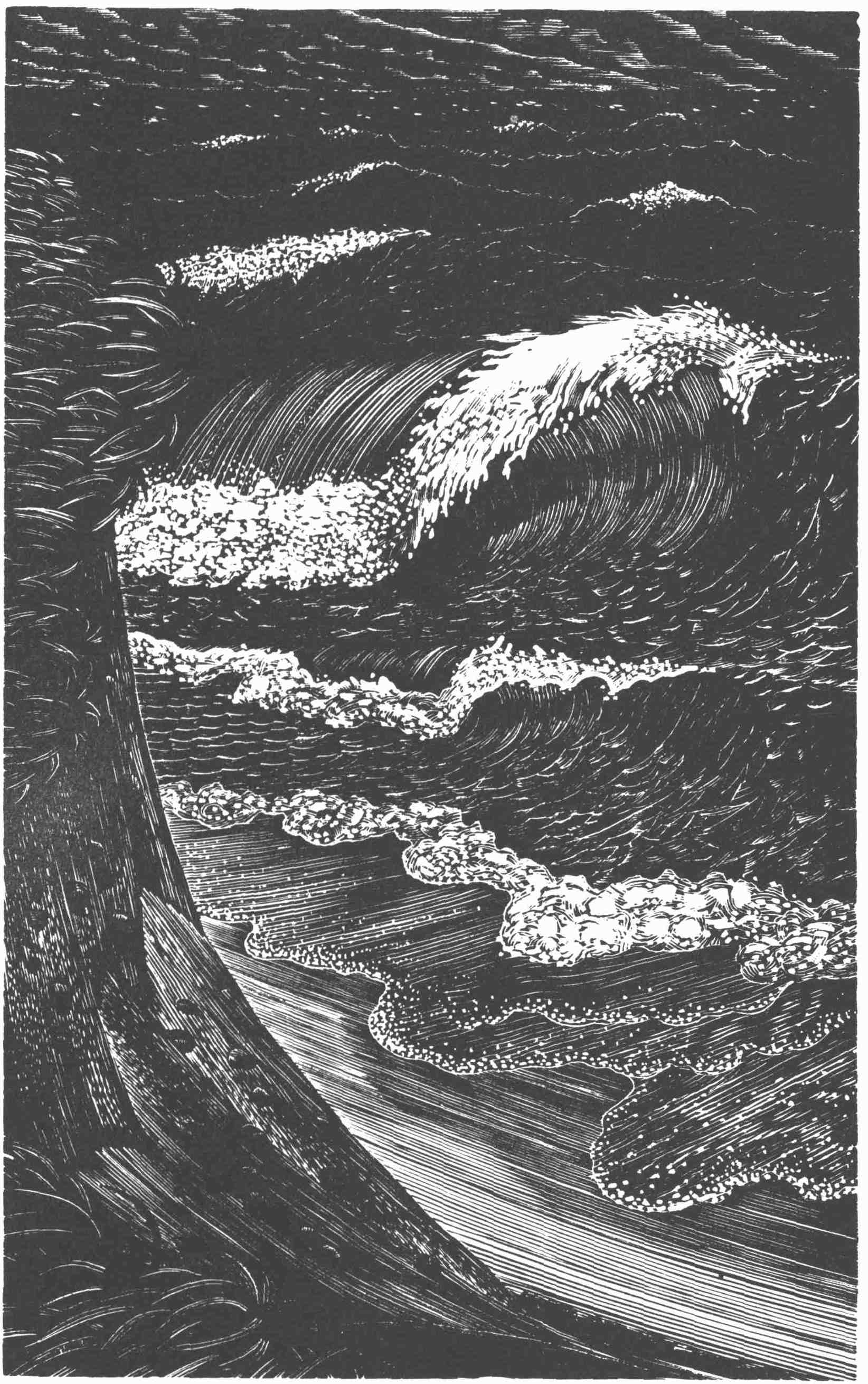

There is a well-known sand bar to steer by in the hazy distance across Cape Cod Bay. We buck the steely waves upwind, close hauled, half hot in the sun, half cold and shivering when the water thrashes in over the bow of the boat. Ropes creak slightly through the boom and the mast. The wake bubbles. Wood strains through water. The west wind blows stiff over conflicting waves. The time passes with a certain monotony but for the craft of sailors and its requirements. There is nothing called for but to sail, with no other distractions on this immediate flat world of light, no concern ... and yet we sense some ultimate demand that comes from this blue giant, whose depths and tricks are still unfathomed.

The flat necessity of it makes sailing its own satisfaction. It becomes physical. We fly, we feel, we calculate, by sinew, flesh, and bones, and through the salty blood in our veins. We may be a degree closer to the black-backed gull.

There on arrival are great white sheets of sand curving up into a barrier of dunes back of a pebbly beach, where a beach buggy rolls along scaring up clouds and crowds of terns, and sanderlings in spinning flight. The jeep stops and teen-agers jump down and out, crying stridently. We anchor the boat just off the beach. The water is clear and cold. The dunes are sun reflectors, clean and warm, and we find whitish-gray grasshoppers on them, flecked like the sand.

Sailing back again in late afternoon, the boat goes fast and[Pgs 23-24] free before the wind over the water now turned green, a blend of sky blue and the yellow of a falling sun. The bay lies out like an enormous garden, patched with color and motion, the salt waters full of latent power, ready with every kind of mood, flowing by and over, interwrought, crossing time and circumstance. We pass a clanging bell buoy. Evening comes on. Gold icicles on the water are turning and softening to shades of pink and purple. It is like striding over a wide land of peace and plenty, before we tack into the harbor.

[Pgs 25-26]

[Pg 27]

What I wanted to do was follow the year around, recognizing that hours, days, months, or years are as elusive as unseen atoms (even though, universal law being consistent, we deduce their behavior with some success). I am not sure where July left off and August began. Summer flies away from me, like an unknown bird.

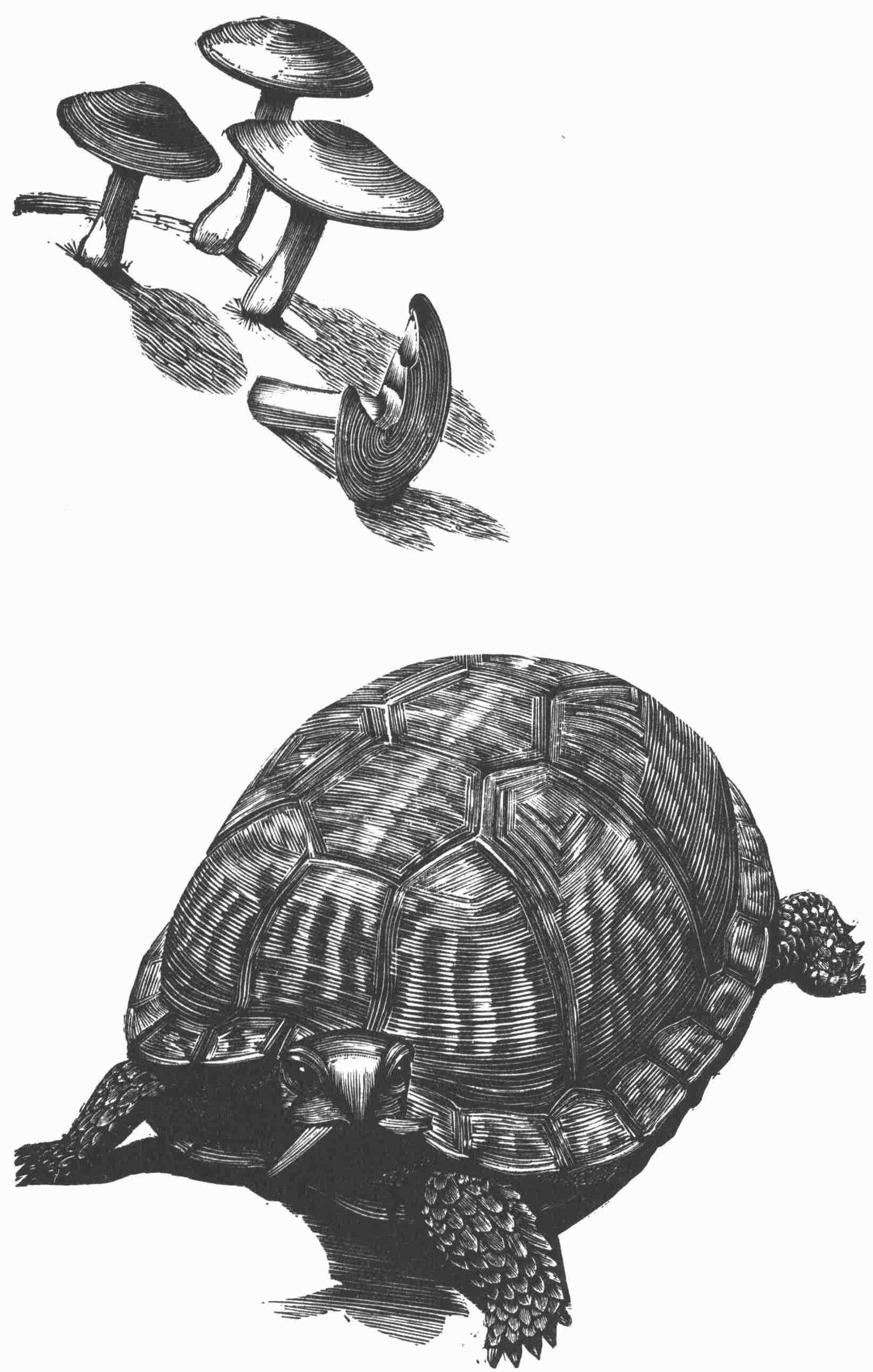

Out into August then, while there is time. When I step into it as if into something new, I sense thousands and thousands of roving lives, taking their opportunities where and when they can. The day is hot and shining. The oak leaves, no longer fresh and young, but spotted with growths, chewed by insects, frayed and scarred, are still tough, deeply green, harnessing the sun, under a stir and slide of air. Two big red-tailed hawks sail high overhead, screaming constantly. A blue jay screams, in a fair likeness. The hawks wheel lower down along the trees, inside the horizon. Then two little tree sparrows flit by. Insects drone, stir, and buzz. There is a dragging, rattling sound of leaves as a box turtle moves slowly along. A cicada chorus rises like a sudden breeze from the southeast and then subsides. Two black and white warblers go through the cover of the woods in a quick butterfly flight together. The “Tock! Tock!” of a chipmunk sounds behind a brush pile, almost like the end notes of a whippoorwill’s song.

I feel a balance in space between them all: the roamers, hawks, or gulls, in the sky’s great allowance; the spider swinging on a thread and making its own web of a world; colorful, elusive warblers through the trees; the chipmunk on its chosen ground.[Pg 28] These sounds, synonymous with motion, seem to hold them in mutual alliance, round in a lightness of air that is strict and easy in its coming and release, like the cicadas; but there is an intensity here that makes my heart beat faster.

A jay jumps down to a branch, cocks its crested head, with those black eyes full of readiness, and brays. The spider wraps up a captured moth with rapid skill. A robber fly waits on a leaf with throbbing abdomen and a look of contained vitality. It is not to be known. I see the brown, glazed wings folded back in the sunlight, and two black, sky-light eyes on top of its head. It seems preternaturally lean. It stays there for ten minutes and I watch it closely, almost suspended with it in my attention. A robber fly is a tough predator, but to call it cold, indifferent to pain, careless of life, darkness personified? Our terms are useless. I do not know. Then my attention is cut, as it abruptly darts off, swinging in an arc, perhaps to catch a housefly a hundred feet away.

In the buzz, the running light, the stir of summer, I feel as if each motion, each event had its own pressing concern. This homeland, no longer graced with the name of wilderness, is full of wild, unparalleled desire.

Everyone knows that the month of August is loaded with insects, although they come under the heading of “bugs,” a menace to human society. Their fibrous trills are incessant in the grass. Their high, shrill sounds announce the heated air. Those two species that we hate more than most, just for their familiarity, the flies and mosquitoes, drone around us. In the heat of noon our senses are a little clouded. We may be mumbling something about “the will of life be done,” and it is being done ... in great part by the insects. The summer rage to take and to share in taking is carried out in minute detail, from the tiniest mite in the soil to the dragonfly.

Manifest energy, using its short summer span, fills our surroundings with its wealth of insects. It has not been long since I was taught the modicum of knowledge needed to name a[Pg 29] few of them, to start in on a fraction of the 680,000 species that fill the earth; but it was enough to add to my sight. I had never realized that such foreign and incredible variety existed so close to me.

A yellow jacket tugs furiously at a dead cricket on the road, like a hungry dog with raw meat. Delicate aphids waver on flower stalks. A big striped cicada killer roams through the oaks. Other wasps sip juice or nibble carrion. Dragonflies dart across both land and water on their tangential licks of speed. The cabbage butterflies flutter and alight with pale, yellow wings held together like one thin sail against the sunlight. Over and under, in and out, flying, crawling, suspended in plants and in the growth of plants, seizing their time, waiting, indefinitely if need be, held in chrysalis or egg, emerging, feeding, adding to death and life in death ... what are these strangers?

There are wasps as red as rubies; flies of a more scintillating, vibrant green than emeralds; and shiny bronze or golden beetles which are the envy of human art. If color is life, to make the human eyes ring and the body respond, they have it, and they also lack it. Some are so diaphanous as to belong only to the sunlit air, and some are so dark, as though part of unseen depths, that all color is only a dance, springing away.

We use up constant, frustrated energy keeping them in check. Their dry throbbing annoys us. They eat our crops, transmit disease, and drive us away from our pleasures: although in the bold stare of nature they are effective employees. We might, slapping a mosquito, recognize their necessity as pollinators, earth movers, or food, respect the role they play in decomposition and growth ... then we must turn around and invent new poisons. Insects are redoubtable enemies. We are never quite sure which of us is in the ascendancy, just as we are never sure of what they are.

Still we can look and marvel at their complex detail: these wings like lace or spun glass; wings cut short and wide or thin as a hair; wings with the pattern of flowers, or veins of a leaf;[Pg 30] bodies round and narrow, oval or oblong; strange truncated abdomens; huge, compound eyes; legs impossibly thin and long, or unbelievable in number and still co-ordinated; heads like alligators; bodies like sticks; false eyes; false horns; repulsive, intangible, unreal.

Here seems to be automatic, nerve-end response in unreflecting zeros, whose lives pass with their deaths, but still, on this earth crust they are affiliated with everything. That which may frighten or startle a bird, like the eye spots on a moth’s wing, is related to a bird. Animals are adapted to their environments and the medium in which they live and act; but so many tricks and curiosities are embodied in the insects, so many far-fetched connections of shape and motion, as to leave all particular environments behind.

In their variety they are in balance with our imagination. Don’t they show as many bursts, tricks, starts, halts, and fires, as much somnolence and surprise in their color, shape, and action as we desire in the exercise of our consciousness? Nature is unbiased in its attention, concentrating equal power on all forms of its expression. When we begin to conceive of nature in terms of creative process—continually evolving, fantastically complex, immensely resourceful—then we recognize our counterparts wherever the sunlight strikes across the air. We share in a communication.

Last month I noticed a group of small butterflies on the mauve flower of a milkweed. They were, as I found out, hairstreak butterflies, with a dusky, grayish-lavender coloration, and little orange patches on the lower edge of their wings. When the wings are folded, their hind tips have tails resembling antennae, which may have the effect of a protective device to confuse a predator. After I frightened them off, they returned in a little while to rest on the very same flower. Their color was not the same as a milkweed’s but in tone and value it was close enough so as to hide them from view at a fairly short distance. The flower and the animal were united in a sensitive embodiment of contrast.

[Pg 31]

A few days later I noticed that the flower was gradually paling. Then, on the twenty-fifth of July, the last blossoms dropped off, and the butterflies were gone. An obvious affinity, and a mystery at the same time, of two forms of life in a unique response to nature’s web of motion.

It took me a long time to become aware of just how much these affiliations and responses made up the life of earth, how much of an elaboration they amounted to. In the past also, when I saw a robin hop across the lawn, a frog jump into the water, or a tree swallow glide through the air, I reacted with pleasure or disregard—by chance, in other words—without realizing just how big a role chance played in their appearance. In the same sense the obvious upheavals of a season—drought, or heavy rains—meant little to me beyond their immediate, local effect. After a while I began to be aware of all the circumstances that must surround me. One dull day I realized their unlimited context, and thought how slow and agonizing my own changes were in comparison.

Expected things happen. But the variations are just as compelling as the stable order from which they come. This June, for example, was cold and wet, and the rains continued into the summer months. The hatching of insects was delayed and the development of some plants and grasses. Many fledgling tree swallows were found dead in their nests, a disaster which seems to have been caused directly by the weather. Aquatic insects are a favorite food of the tree swallows, but in cold, wet weather these insects tend to remain in immature stages and do not develop into flying adults. (Swallows chase after their food in flight.) And, in fact, when insects are few, the tree swallows seem to be discouraged from looking for them. If such conditions keep up, they may leave a nesting area to look for food elsewhere.

Our local run of alewives, those inland herring that migrate from salt water every spring to spawn in fresh-water ponds, seemed to be a little later than usual; and the young, hatched from the eggs they left behind them, started down to salt water past[Pg 32] schedule in July. If the ponds are colder in temperature than is normal, it probably affects the young alewives’ size and chance of survival. They grow larger and healthier in warm-water ponds because they are started sooner and have a richer supply of food. A smaller, slightly weaker fish is more easily caught by a predator.

Because this spring was somewhat off the average mark (and in a sense there is no average), many of the relationships between plants and animals dependent on it were altered. Some of the effects, in animal population or health, might be felt for a long time to come.

Although ice, fire, storms, hurricanes, unusually wet or dry seasons, and now the hand of man, may alter the local earth almost beyond recognition and bring its inhabitants to disaster, natural occurrence has an indomitable will. Its changes outlast all others. Uncounted lives are sent ahead, balanced always, but with relationships through time and space that are never exactly the same. A leaf drops earlier. Frogs start to shed their skins, or migrate locally at a time that depends on new climactic conditions. Why have I seen so few mole runs this year? Last year there were comparatively few baltimore orioles. This year in orange pride they were leaf calling and diving everywhere. I have seen very few phoebes in our vicinity of late, and scarcely any bluebirds. There may be more mosquitoes this summer and fewer grasshoppers than usual. I can inquire, for each species, and find out what I want to know, if there is logic, and cause and effect to its behavior; but all are related in a realm that is wider than I ever imagined.

[Pg 33]

Many Augusts, singing loud, have passed me by without my giving them a shred of attention. What made the sound? The air, or the trees, the month itself, embodied in unknown voices? I don’t think I knew much more than that, although I suppose I was aware of what a cricket sounded like. Perhaps it is time to find out more. I know now, as I did then, that at night when the air is soft and cool, a multitude of separate actions having died down, and when the earth is relieved of a fire taken to the stars, a plainsong goes up and the night takes substance in pulsing sound.

When I listen, I see that in detail the sounding of an August night is not melodious. It is full of clicks, dry rasps, ratchets, reedy, resinous scrapings, and except for countless populations playing on one string, disassociated. There is only one phrase for each species of insect. The over-all sound is occasionally reminiscent of telegraph wires, mechanically shrill and tense; but in the context of the night, speckled with stars, it becomes as wide, warm, and luminous as any symphony.

Having heard of using a flashlight to search for these musicians, I go out, sometime after eight-thirty, and start training it on sounds, with complete lack of success at first. Either the sound stops, or the animal that makes it is invisible to me. A bat flies overhead, chasing insects. It is known for accuracy, having ears with a receptiveness like radar, tuned to the finest measurements of space, but its flight seems frantic. It beats back and forth, around, over and under. Suddenly it is very close, perhaps[Pg 34] a few inches over my head. I duck at the leathery, fluttering sound, something like the rippling folds of a taut chute, despite my knowing that only in lingering myth and hearsay do bats catch in human hair. Then it is off again, with its violent, erratic flight.

The darkness takes deeper hold. It is full of the loud throbbing, the insistently high-pitched rasping of the insects, with an occasional tree frog sounding a contrapuntal “Ek-ek.” Playing my flashlight under the trees shows up a spider web in beautiful detail. The silk strands are clear against the black night, their swoops and whorls all held together by long perfected execution, with the tiny engineer way up on his round span, his semblance of the globe in its vast waters.

In high suspension, in the larger silences of the sky, all rings well in consonance, and the pulse of living instruments is with the massed stars that run out and dive away above all heads, and with the ground, my heart and ear, my blood and bone.

A persistent light racheting makes me concentrate on one bush, where I eventually find a green, well-camouflaged, long-horned grasshopper with orange eyes—a male, since it has no ovipositor on its abdomen. The females are silent, with the honored role of being courted and invited.

The flashlight seems to have no effect on him. The front wings are slightly apart, raised up a little, and vibrating ... a kind of fast, dry shuddering. The sound is a light “zzz,” ending with a rapid “tic-tic-tic.” This grasshopper is a waxy green. His antennae, almost twice as long as his body, go up in sweeping curves, and wave, sometimes both together in a semicircle, sometimes singly in both directions, as he stops his playing, and begins to move slightly down a twig. Then I notice a female moving in his direction. Had he increased the tempo of his playing when she came near? Did he sense success?

Still harder to spot—almost impossible by day, and difficult enough at night—are the snowy tree crickets, but they are numerous[Pg 35] in this low-treed, shrubby area. Where the long-horned grasshoppers sound at intervals, the combined chorus of snowy tree crickets pulses on. They are slender little creatures, a very pale, almost immaterial, green, but their fragile, transparent, membranous wings, raised higher than those of a long-horned when it plays, make a cry that rises up like peepers in the spring. This is the famous “temperature cricket” whose song speeds up or slows down in response to heat or cold. According to the field manuals, you can divide the number of notes per minute by four and then add forty, which will give you the approximate temperature in degrees Fahrenheit.

So this great scraping and fiddling perpetuates a dance. The first frost will end the lives of most of these musicians. August’s high sounding means a coming end, but all of its connections and associations join in sending on the year. This is what the month means, as well as the hum of tourists driving down the Cape and back again. Listen to the chosen string.

There is a miraculous sensitivity in the cricket that slows down when the temperature begins to cool at night, or even when a cloud passes over the sun by day. The male calls to attract the female, though it is apparently not known whether her arrival may not be the result of happenstance. His playing is as much a part of general expression as individual intention or reaction. In any case the eggs are laid, which will stay dormant throughout the winter, to hatch in the spring. The organic cycle continues, making an announcement, sending up a music whose players are so attuned to light and dark, sunlit or clouded skies, warm air or cold, day or night, that their existence depends upon the slightest change.

[Pg 36]

The broader aspects of the weather are more apparent to my kind of receptiveness, which is less mortally tuned to degrees than a grasshopper. There is still an abnormal amount of rain as the month goes on. Their sun blotted out, many tourists have left the Cape earlier than usual. I notice that the days are shorter and cooler. The prevailing wind, southwest in fair weather, southeast before a storm, blows gently, or in gusts when it rains. A big mud puddle on our wood road has collected a whole population of green frogs. At night there is great frog carnage on the wet highways. I have noticed in the past that this is their season for traveling, whether it is wet or dry, but heavy rains encourage their migration, sending them far and wide. There is a multitude of garden toads around the house. One night it cools down to about 50 degrees and in the dawn hour the leaves are bluish gray with dew. A hurricane, spawned in the Bahamas, is two hundred miles east of Florida, but beginning to turn slightly to the north, away from the eastern seaboard. High seas are predicted in three or four days’ time.

I feel as though we were hesitating on the brink of new necessities, swinging between one resolution and another not yet found. The season is beginning to join the winds. Some migrant birds have already flown away. Other birds fly through the leaf canopy feeding seriously and silently. A warbler, a female yellow-throat, skips lightly along a patch of briar and vines. A brilliant oriole jumps into a patch of oaks and moves on down sunlight-yellow ramps of leaves, and a black-billed cuckoo, a large brown[Pg 37] bird with a handsome, long tail, stops in on a branch with a look of eagerness and seeking, then flashes off again. There is a change in their action and timing. The adults are long since through with the claiming and proclaiming that rang in the woods before they nested. The steady, constant business of feeding their young is about over for most species, though I see a flicker, or yellowhammer, come through the trees in diving, shooting flight, with a young one following loudly after it. There are many fledglings, but on the whole the birds, many of them starting to molt, are silent compared with spring and early summer.

This wood road of ours, where the birds fly through, is used every school-day morning by our children on their way to catch the bus. It is a kind of open line through change. It rides the side of a low ridge, and glacial hollows dip away from it. It once served as a wagon road for woodcutters, and is still shaded by the insistent, if none too “sturdy,” oaks, which come back again and again, no matter how many times they are cut. They make the road a green tunnel in summer, and their gray branches with knotted fingers rattle and sway above it in the wintertime. It receives many travelers by land and some by sea. (A few Januaries ago I found a dovekie there, a little sea bird with the black back, short black wings, and white breast of a penguin. It is one of the members of the auk family, breeding in Greenland and migrating down from the ice-locked waters of the Arctic Circle to feed in the Atlantic during the winter. Its short wings are meant for swimming, diving, and flying in and out of waves, so they are not very effective when blown inland by a storm. The dovekie I found was unable to take off, and in any case weak and hungry. So after a futile effort to feed it, I took it back to Cape Cod Bay, where it started to fly along the surface of the water, though weakly, in short, floundering dashes.)

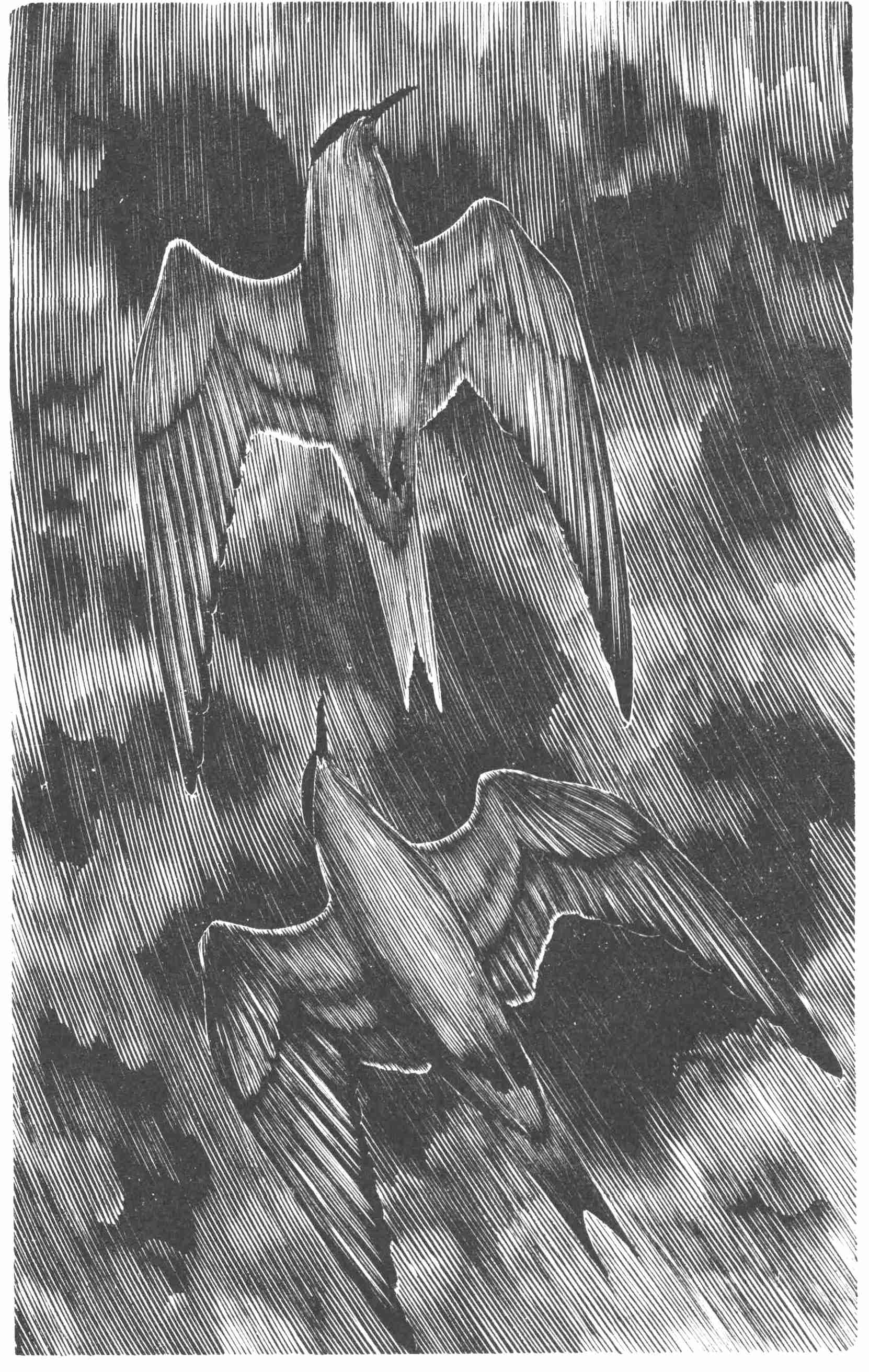

With a half mile of concentrated road it is easier to take cognizance of friends and strangers than when you are trying to make California on the transcontinental highway. You can see how it is used by skunk, squirrel, deer, and the hunters of deer.[Pg 38] I walk it in expectation. One of the animals that constantly move across the road and live in the woods beside it is that bird which looks like a tiny thrush but is classified as a wood warbler, the oven bird. Its “Teacher! Teacher!” rings out in spring and early summer. It was named after its leaf-hidden nest, made on the ground, with a hole going in at the side like a Dutch oven.

Here is an oven bird, tail bobbing slightly, perched on the lower branches of a red maple beside the road ... a little more out in the open than usual, less concentrated on its earlier nesting territory. It flutters down to the road. This is one of those birds that have the distinction, if that is what it is, of being able to walk, rather than hop or run. So it starts walking, through the dappled shadows on the road, as I keep a respectable distance behind it. Or perhaps I walk and it attends to business. The oven bird goes back and forth, pecking insects, with a quick meandering, interrupted by an occasional little jump at the leaves of an overhanging shrub or plant. This is not a straight walker, no Indian with a destination, but its body moves constantly from left to right in purposeful flexibility.

“How well you see!” I think to myself. I can see nothing at my level but a tiny yellow caterpillar swinging through the air on a silken thread. But it is clear to me that the oven bird works the road with clear results. We keep going. We come to a stretch in full sunlight where the trees stand off to the side, and my companion keeps to the shadows with determination, pecking away at insects along the few inches of shaded bank to one side. A flicker bursts through, shouting: “Tawicka! Tawicka!” and the oven bird flies ahead a few feet and then goes on walking.

We have now traveled about an eighth of a mile. Under a heavy weave of leaves the bird moves to left and right over the road, pecking for insects, working, progressing. Olive brown; capped with an orange stripe; with speckled breast and pale pink legs ... a shadow bird, a leaf litter bird; and now a fellow walker, that has made more use of this road than any of us[Pg 39] and our omnivorous machines. At a sharp bend in the road where it leads up to the house, the oven bird finally flies off and disappears in the trees, in a southerly direction by coincidence. Our walk is over, but the flight of birds will leave all cars behind.

[Pg 40]

There is “man” and there is “nature.” But do we really know where the climate of existence starts, where its storms are brewed? All weather is unexpected. Another variation in the known routine, another change in use, and we may move, reluctantly, into some new awareness while primal energy bowls on with infinite capacity.

Among the oaks the leaves on the top branches sway and rustle, while those on the wood floor scarcely lift at all, but there is a constant sound of air among them, and it might be possible to hear a ferment in the ground. Small suns blaze through round leaf lobes. Standing on a slope toward the north from which the glaciers came, and the auroras crackle, shimmer, and flow, and the cold from Canada will have its way, I have a feeling of portentous motion, of being sledded out on a speeding globe.

The hurricane veered off. There was rain, but no great winds. The mud puddle in the road dried up after several sunny days, and the green frogs left; but when it filled up again they had not returned. The frogs have a different motion in them and will not come back to suit my metronome.

Many vacationers are going home. We can almost walk across the highway without fear. There is still the press, the fevered demands of summer in the air, but something else is going to have its way.

A changing light, a shifting wind, calls me out to meet more of this earth than I know. Habit stifles me. My round needs to be recharged. So I take a walk, like the oven bird, though not to gather[Pg 41] any more food than my senses and my spirit need. There is a lobe of land a mile away, through the oaks, over the shore road, and across to sea level, called the Crow Pasture. It is bordered by a tidal inlet and marsh on one side and the sands of Cape Cod Bay on the other. It is covered with low, wind-topped growth, blueberry bushes, beach plums, stands of pitch pine, and stunted oak; and it is flushed with moving light and shadow, hovered over and hunted by great clouds. The Crow Pasture is without houses so far, and it is a bare recipient of high events, the range of storms, the distances that come in and declare themselves by wind or flight, the summer vaunting of the sun, the cold appeal of the moon. Narrow, rutted dirt roads lead into it and take you on.

This land, once used for pasturing cows, now domesticated only by sparrows, robins, and chickadees, has final summer abundance in it. Locusts bound from dry land grasses with rattling wings. Green head flies buzz in savage haste. A yellow and black goldfinch flies over, bouncing along.

There are ebony-beaded blackberries on the ground, and a few dark berries left on high bush blueberries. A stiff wind from the south shakes up the thickets and the wild indigo, a compact, light bouquet of a plant with cloverlike leaves and yellow pea flowers. Pointed cedars stir and writhe. The air rushes through the bayberries with their glossy leaves, and it sweeps down across the marshland ahead through purple and yellow grasses that plume and sway, off to the white sands beyond.

Open land, wild air, lead ahead until salt water appears, the blue barrens that curve beyond sight. Stiff, stunted bushes are backed up at the edge of the marsh, hideaways for sparrows, then marsh rosemary, or sea lavender, shows in occasional clumps through the eddying stalks of grass. One area is thick with mosquitoes, sounding a low melody of harassment. In the bed of a ditch, dotted with holes made by fiddler crabs, are the tracks of a skunk. All that lives here permanently, not foraging like a skunk, or migratory like most of the birds, has to stand strong light, harsh winds, and salt spray, that dry, abrase, and burn.

[Pg 42]

The marsh merges with the sand, back of low dunes covered with stiff, sharp-tipped beach grass and seaside goldenrod, thick stalked, with broad soft leaves, a succulent, related to cacti, made to hold and retain moisture. The beach shelves down from the dunes and meets the exposed tidal ground, ledges of dark peat which is pitted like volcanic rock, and very slippery to walk on. Beyond it at low tide the sand flats ease out, stretch and flow, with aisles and purple fingers of water rippling, writhing, and probing across them.

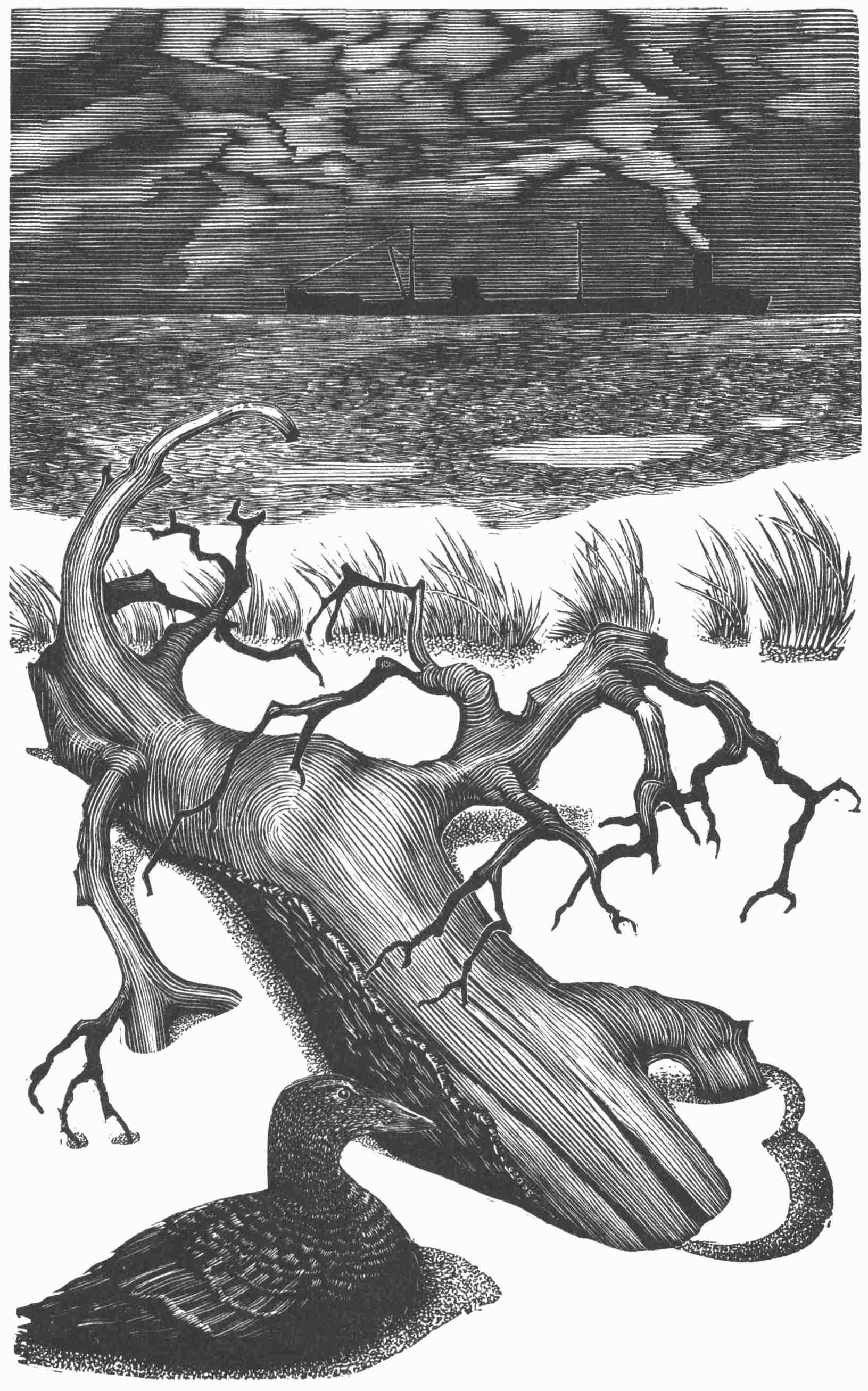

Further along the shore a group of gray and white herring gulls stand into the wind. Hiding in a clump of peat-rooted grasses a few hundred feet from them is a gull in its first year. One of its wings is broken, with the primary feathers dragging on the ground. The bird stalks slowly along, tripping a little, isolated, a picture of shame and loss. When I approach, it moves reluctantly toward the other gulls, then stands into the wind slightly behind and to the side of them. Suddenly the flock takes to the air, and the young gull stays down, crippled, unable to forage for its food, and ultimately doomed. There are various kinds of mutual assistance in nature. Some species, like Canada geese, may help, or try to help a fallen mate; but there are no hospitals. I am told that a sick bee rolls out of a hive if it can, or is pushed out by the others. Animals must be deeply aware of death, and they die alone, perhaps with an instinctive understanding that they have to pay the price of a health which nature ultimately requires.

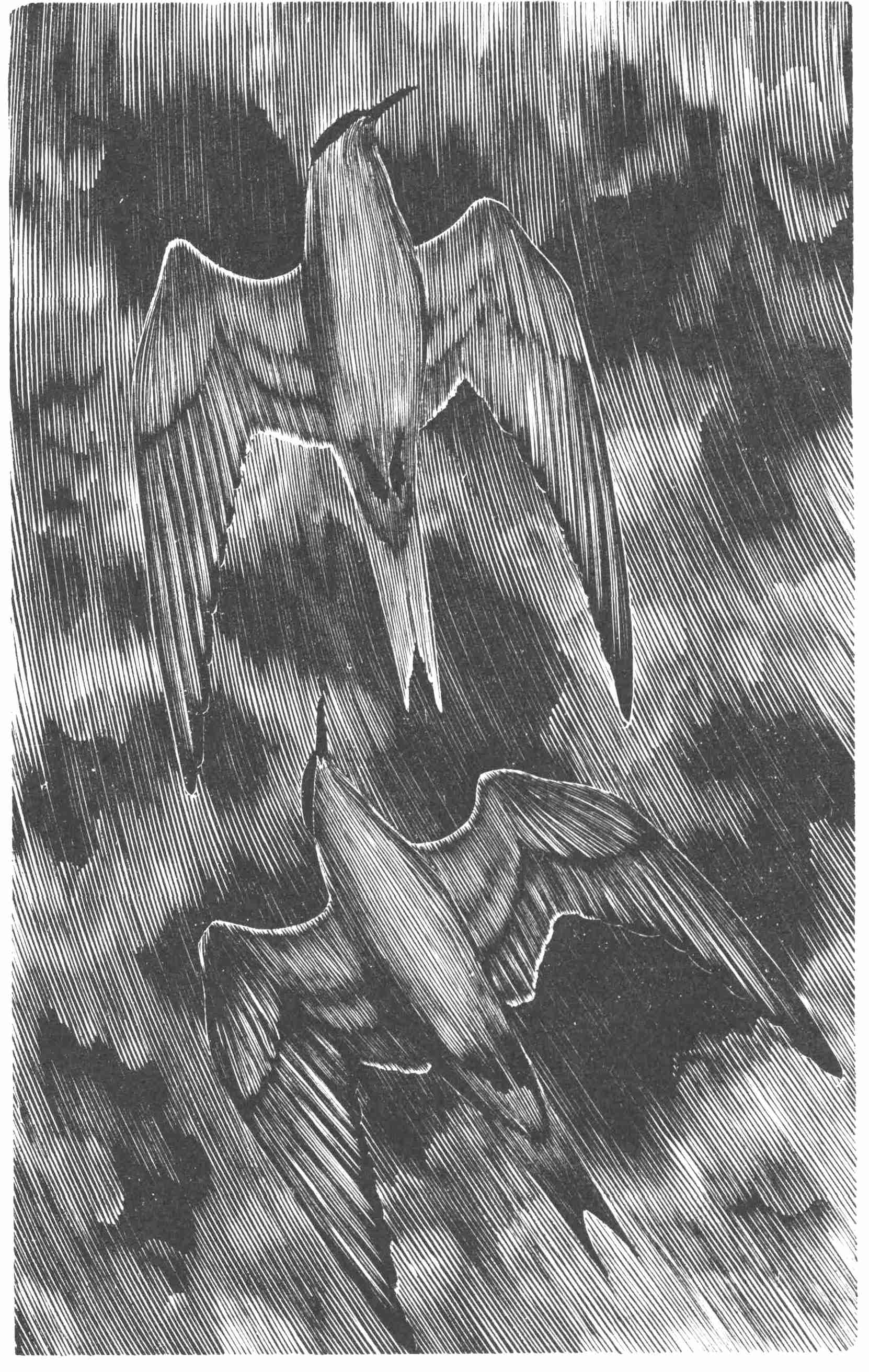

The landscape slopes on and out from life to life, swept by the air, an earth, sand, water, run of interchanging light. Clouds of white terns are hovering and diving over the waters of the bay. Suddenly a dark-plumaged marsh hawk flies into the midst of them. They harry it in the blue, heat-clouded sky. The hawk circles, dodges, flaps on, while they dive on it continually. It twists and rises higher and higher trying to shake them off, until it plummets down and flies low over the surface of the water, making a great round turn back to the shore.

The crippled gull stands and waits with hurt patience. The[Pg 43] hawk flies back to the marsh behind the beach and begins to beat slowly over it, covering the ground methodically, hunting the unwary shrew, mouse, or sparrow. The terns dive for fish. The tide waters begin to slip in over the sand. Measure for measure. Necessity keeps its component parts in order, as the light changes, and the south wind keeps blowing.

Down the shore to the east is an inlet called Paine’s Creek, which receives the inland migration of alewives in the spring, and takes out their young, hatched in early spring and summer, as they swim to salt water. The alewife fry, two or three inches long, attract gulls and terns. During the month there has been a migratory colony of terns in the vicinity, principally common terns, both adult and immature.

In the general Cape Cod area there are two principal nesting places every year, at Tern Island, Chatham, and in Plymouth. During the season—the birds arrive about the end of April—both terneries have populations which number in the thousands. There are in addition a few small islands off the Cape and a few comparatively isolated areas where smaller groups nest successfully, although terns are sociable birds, and breed best in large numbers. In August, beginning with the arctic tern, which, I am told, is the earliest to migrate, the birds begin to leave their nesting sites in groups or small companies on their way south. They spend the winter anywhere from Florida to the edge of the Antarctic ice.

So the Paine’s Creek area, with its sand eels and alewife fry, represents a way station, a stopping-off place, one leg of a migratory journey ... the first for birds hatched during the late spring or early summer. Terns reach flying age in a month, but their parents go on feeding them for some time. They are slow to mature and do not breed until they are about three years old.

The young are not much smaller than their parents, and without a close watch it might be hard to tell the difference at first; but their heads are gray, as compared with the jet-black napes and crowns on the adults. They still spend most of the time waiting to[Pg 44] be fed. Some make inexperienced, practice flights over the water, plunging in and out in an almost kittenish, hit-or-miss way, while their parents dive like arrows, pinpointing the surface with little flashes of spray, from which they rise up with silver quarries in their sharp bills. But as many more of the young terns stand along the beach or on shoals at the mouth of the inlet, crying, begging to be fed.

Terns are intensely active and brilliant in performance. They are comparatively small birds, but they are capable of migrating over thousands of miles of ocean waters, and their long, angled wings beat deep, low, and strong. They are all black and white sharpness, flashing as bright as the gold circlets of water around sharp grasses at the mouth of the inlet. They swing. They dart. They winnow the air. Their lovely white shuttlecock tails spread out and settle as they turn against the wind, crying: “Kierr! Kierr!”

Two juveniles wait on a shoal, constantly calling in a high-pitched tremolo, intensified when a parent bird flies over them. The trim expert adult flies past, then swings back down the shore and circles back, finally coming in to land between them. It has no food in its bill, but stands there for a minute or so, and then begins to move away from them, as they crouch and strut after it in an almost elderly way, crying their protests. It signals departure with a slight lift of its wings and in a few seconds flies up, the thwarted young ones taking off behind it.

In this behavior I see the play of learning, the many repetitions that precede a balanced natural art. Other adults swing in with sand eels or fish in their bills and hover, or circle back, avoiding rivals, then drop down next to a twittering, beak-gaping child, giving it the whole fish, or holding on to it and flying away, which has the effect of teasing the young one to follow after. In this way the fledgling terns, some still crouching down in a submissive manner as they did in their nests, learn to fly up, to chase, dive, and dodge, to breast the air, and beat their wings for all the long voyages their lives may hold.

[Pgs 45-46]

In a few weeks most of them will suddenly flock away and migrate. In the meantime they practice the instinctive measures of growth, training in the insistent, excitable ways of a tern, for air and open waters over half the earth.

[Pgs 47-48]

[Pg 49]

The tourists and the summer residents begin to leave the Cape. This is a visible exodus, with many more cars going out than coming in. The people in charge of commerce count our summer gains and our losses. Those of us who are year-round residents can admit it in public, now that the representatives of the humming, spreading urban world have departed. Here now is a half-populated place, temporarily, perhaps shamefully, consigned to a dull future. And yet, according to the practice I have begun to learn by years of residence, I can now look around, with room to spare. What fills this emptiness? What will I see when I take off my dark glasses?

I notice, by the way, that some of us are now predicting the local future with more assurance. I hear a real Cape Codder (meaning someone born here, preferably before 1900) pronouncing that there will be a frost around the sixteenth, and that “We’ll have a blow pretty soon.”

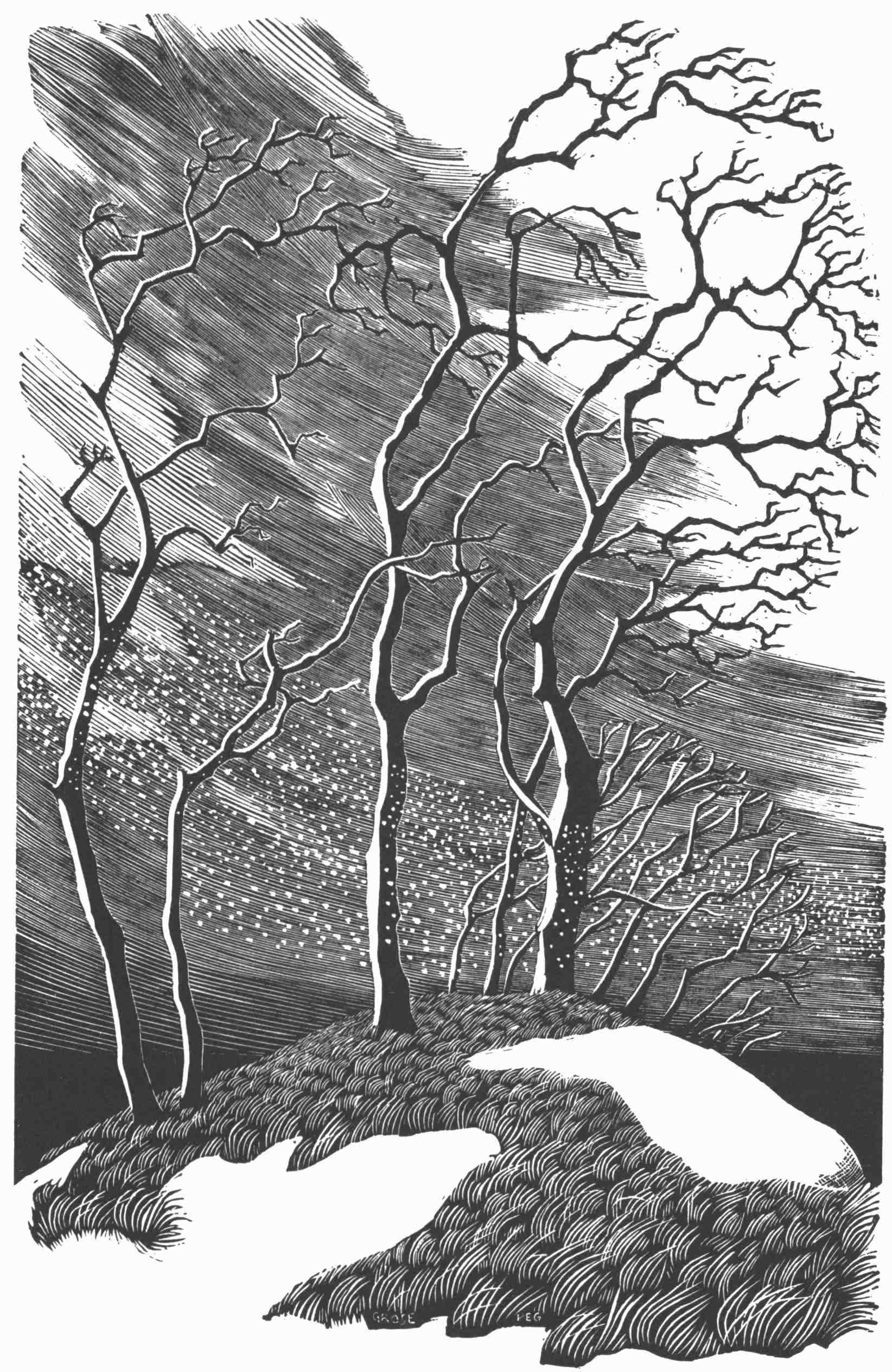

The night heaves with heat. A half-clouded, half-misted sky shows occasional stars. Then an onshore wind begins to blow and the land stirs and frets in the darkness. I feel that new revolutions are in order, earth-honored, momentous changes.

In the morning the weather vane stands to the north. The sea is kicked up, the trees are swaying, and the temperature has dropped into the fifties. A new wind is getting in its licks, rolling and lunging against us. The air above the sea meets the great air masses from the land. Warm and cold, water and air, west and south, north and east, join in a game of strength. The whole day[Pg 50] is a trial for the future, with the running clouds as its pawns. A child asks her father: “Can the day blow away?”

When the wind dies down and the clouds clear off, the air has changed from a hazy warmth to clarity. The sea turns dark blue, groined with white caps. The land seems strict and clean, lifted into pure new skies and a new silence, although at night the musical pulsing of the snowy tree crickets is still as shrill and loud as spring peepers.

This is a marginal season like the spring. It is full of new appearances, as well as late fruitions. The goldenrod, strong flower of the sun, still plumes its store of light, and represents me well in my country, in spite of congressional inclination to award some puffy, manufactured rose with the title of national flower.

Asters, lilac and white, grow abundantly in the sandy soil. Their little pin wheel flowers are as crisp and clean as the new dresses of the girls when they go off for the first day of school. The novelty, after the closed-in summer tempo, is an outwardness. There are many immature birds that appear suddenly in various untried places, and not necessarily because of the demands of a set migration. Because of these fledglings the various bird populations have so increased that they are pushed into looking for food beyond their nesting areas.

Immature hermit thrushes appear as if at random, and many robins and towhees. The towhee, once called red-eyed, a name that seems to have been changed to rufous-sided, is a handsome black, white, and terra-cotta bird which likes scrubby areas, thickets, and open woods. So we see it frequently. It has a black and white tail with which it puts on a spectacular performance, flicking and flashing its feathers like a gambler with a deck of cards; and it floats over the brush and across the ground with its tail spread wide behind it.

Now the young towhees call “Twee! Twee!” not quite at adult strength and clarity, but they are finding themselves. They are on the move.

A covey of young quail suddenly starts across the road, coming[Pg 51] out of a field still loud with insects. Heads and necks up, they run almost trippingly forward with sweet, piping alarm.

A young red-tailed hawk is brought into school by a boy whose father found it trapped in his chicken yard and killed it ignominiously with a baseball bat. Red tails are big beauties with a thick supply of feathers. Their backs are brown, their white bellies flecked with brown. The usual place to find them is high up, wheeling around the sky on a watch for rodents; and occasionally they fly out of pitch pine woods where they roost. The dead one has lost its piercing cry and the electric glare in its eyes, but its talons still look formidable. They are black, and as sharp-tipped, as wildly curved, as hooks of steel, joined in power and flexibility.

Bright days warm the surface of the inland ponds that have their outlet in the waters of our local brook and estuary leading through marshes to Cape Cod Bay. The sun’s radiance hurries up the alewife fry in their ancient impulse to go down to salt water, from which they will return in three or four years’ time to spawn like their elders, usually in the same fresh-water system where they were hatched. These little silver fish, with an unfathomed stare in their big eyes, run out on an ebb tide from Paine’s Creek. They attract gulls and terns, which hover in crowds against the west wind.

The plumage of the young terns still in the area now shows a more definite contrast between black and white. They have become more adept at flight. Many are still being fed ... almost continuously during those hours of shallow water when fish are easier to catch, so that the passivity of those still waiting on the sands looks like a consequence of being overstuffed. I get the impression that less food is being proffered by the parent birds, but they have certainly not relinquished their responsibility. They bring in small fish and their large children gulp them down and wait for more. Other young birds are now flying readily—chasing after their parents, beseeching attention, but more often trying to fish for themselves. Little by little, by rewards and refusal, failure and success, they are progressing toward the perfected action of[Pg 52] mature birds. They are becoming more aggressive, fighting for space over a crowded channel, or protecting their catch. The adults, whose success in fishing they are beginning to approximate, hover over the water, beaks pointing down, then dive suddenly, wings partly folded back. They hit the water like small stones, then come up again, flying away fast if they have a fish in their bills, chased by other birds that cry “Karr! Karr!” with a slightly growling note. It is not so much that the young terns are taught, in our sense of the word, as that they become more and more a part of the communicable rhythm of the whole race of terns. Their circling, diving, hovering, or racing downwind are common proficiencies of motion, that fit the great environment of air and sea. Growing up is rhythmic practice. There is not such a gap between tutelage and its recipients as there might seem to be among human beings.

Terns seem involved in a ritualistic performance throughout their lives. Much of the behavior they show in getting food as nestlings and fledgling birds has its parallels in adulthood. There is the “fish flight,” for example, which has its origins in the begging, receiving, and then hunting food of a growing bird. (A fish is a master image, a center of recognition and attachment, with all the formality of action it entails.)

The fish flight is a term which in its strict sense is applied to the behavior of birds during pre-courtship. It involves emotional display between pairs of birds, as distinct from their food-getting habits in general. In detail it includes differences in calls, in the relative positions of birds during flight, and in the way they carry a fish. A fish in the bill not only represents the fulfillment of need. It may also be an offering, a display, and perhaps the instrument for a mutual awareness between male and female, even before sex recognition occurs. But if the fish flight can be tied down to behavior at a particular stage in their lives, the terns also show similar reactions before and after it. Mated birds go on offering fish as they fly by one another, or begging, so that feeding is used to maintain a bond between them. And of course the fish is the[Pg 53] basis of all the instinctive training of the young. The process of begging and receiving, or offering for the uses of recognition, continues on in many forms through their life stages. They pursue a formality. Their flights show the grace in action of a whole society.

At half tide, when the water recedes over the sand flats, the terns flock there, preening and bathing in the tidal pools. Occasionally one will lift its wings up beautifully into the wind, receiving the wash of air. Some fly back to the inlet and drink the brackish water. The community seems to gather more and more closely together as time goes on. They all begin to roost densely in one area. At times they take to the air, as if alarmed. They rise and circle, crowds of white, crying shrilly, and then fly down again. Or they spin like a larger flock of sandpipers, a white cloud dancing with dizzy perfection over some fish weirs in the distance. Perhaps it could be called communal practice for the next journey. In their rhythms they are self-sustained, self-protective, like schools of fish, but at the same time bound out, under the laws of the wild air. One day soon I will go down to watch again, finding that most of them have flown away.

[Pg 54]

We stay where we are, while the young migrant birds and the men of the city leave us. But the days sharpen and change. The nights grow longer and cooler. The westerly winds increase. There is a brilliance in the air, and the sea makes a clean statement to our senses. “Adjust your vision,” the sky seems to say, “to a turn in height and depth and in a new area of relentless winds.”

Those migratory birds that are still with us feed actively, fly with restless energy, and collect in flocks. In many undisturbed areas, down by the barrier beaches and through the salt marshes, treeless, open to the sun, you can see a great number using their special physical advantages to feed or fly, hide or attack, in the patterns of environment.

The U. S. Wildlife Refuge at Monomoy is on a long spit of barrier beach and marsh extending south from the town of Chatham ten miles into Nantucket Sound. It is wild, unadorned with tourist cabins, and so an undisturbed refuge and resting place for migratory birds. At first you find warblers, gnat-catchers, orioles, vireos, and other land birds, working silently through low oaks, pines, and stunted, salt-sprayed shrubbery. Then the marshland sweeps ahead with open ground, and curving inlets behind a long beach where the surf pounds endlessly, the sands inlaid with the debris of the sea—whelks, surf clams, or scallops. Back in the marsh where mud snails stream slowly ahead in a long procession, the shore birds race in, or turn quickly in a shimmering flock, or settle among the hummocks, and along sandy rims.

Dowitchers stolidly probe the mud with their long bills. That[Pg 55] mottled, distinctive bird, the ruddy turnstone, pushes, or turns over, pebbles and stones—thus proving its name—as it searches for the worms and crustaceans underneath. Shy piping plovers, white as oyster shells, stand by themselves behind a dune. Sanderlings hurry back and forth with little twinkling legs. The yellowlegs fly up and over with short, piercing cries, their wings curved like sickles. Or a solitary marbled godwit flies by, handsomely patterned on its wings with black and white. Least sandpipers, tiny animals with greenish legs, hurry and flit along, feeding at the edge of the tide pools and the rim of inlets.

The terns—common, roseate, least—fly at a point where the tide comes in through an opening in the beach. Sharp-cut divers, they swoop low, dipping into the water again and again. A few ring-billed gulls move among the shore birds. They are a little like a small herring gull, but their heads are more rounded, like pigeons. They have a lighter flight, and a softer look than their raucous, flat-headed relatives. And over the ridge of the beach, against up-dune horizons, is a long belt of great black-backed gulls, large, proud, and with a look of supreme idleness and cruelty.

Here is “function” in all variety, each life to its place, filling a niche, with the special form and manner by which it feeds and tries to survive. And every bird is a bird of the sun, adapted to this treeless, narrow shore that blazes with cutting light, the light of sand, or rock turned to sand, of water, roaring and moaning in the sea, rushing back through a tidal cut on the ebb, then trickling, evaporating, and swelling in again at the flood. Each animal works an open coast, across its burning days. The fliers with wings so sharp, energies of light, fit the high or low wants of the wind, the curves and sweeps of the open marsh, the glaring sands. And they hurry on stilts, or tiny short legs. They bob up and down. They run trippingly along—all to the rhythm of the watered, indefinite shore, looking for food that is rhythmic in myriad ways. Here is a great tribe of searchers.

The human race, as it climbs laughingly into motor boats and roars down an inlet, or sits soberly baiting fish hooks in a row[Pg 56] boat, or basks in the sun, is no less brought in, fitted to this region—for all our autonomous great world of threats and shelters. There is some compelling call, that springs its lives ahead, and will not be talked away. Even the large, extraneous footmarks of seventy male and female “birders”—a very special tribe—are evidence of an omnivorousness, a searching, communicating, flocking together, from which no animals are entirely exempt.

[Pg 57]

As some of the inhabitants of sea and shore move on to the south, inland life adjusts itself to local climate. The leaves on the trees are still green, but the bracken, or dry land fern, has turned brown, one of the early signs of autumn. My surroundings are full of statements of this kind, an end result of preparation. I notice one of them. I stop—pleased to be told—and then I wonder what was silently going on in August to have placed us with such definition in September. Plants and animals move into a new light, a new scene, when I am merely groping with their names. Perhaps because I have read too many newspapers, I am limited to what we call events. I see some outward evidence, and am obliged to go backward in order to reconstruct what might have been, when the real show is already over.

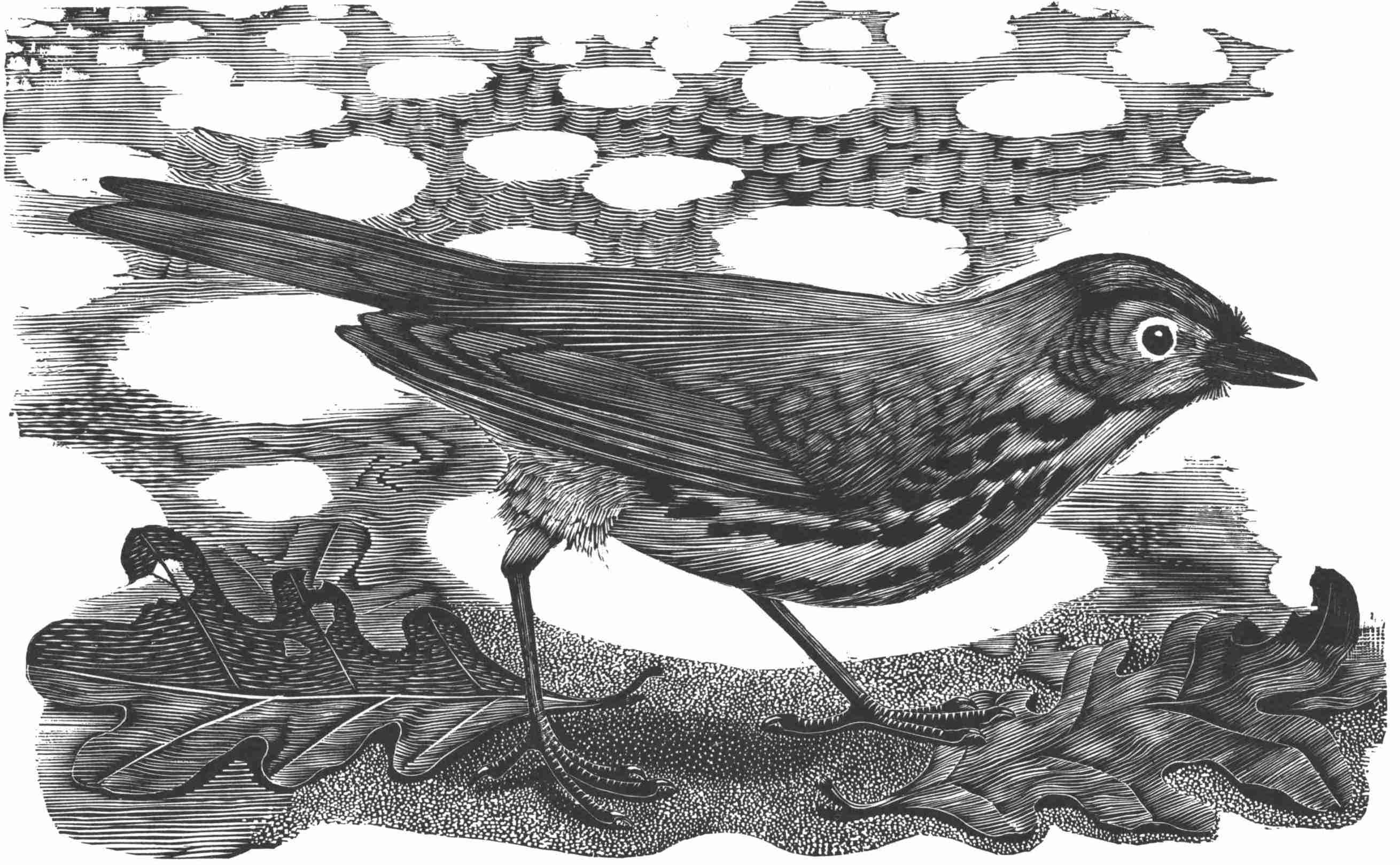

So all September’s reassociations and revolutions may just end up for me as a clump of locust leaves tugged loose by the wind, or the sudden opening in a milkweed pod, or a new chill in the air. One day I notice that a milkweed pod—on the same plant where I saw the butterflies—erect like a lamp on its bent stem, has developed a dimpled line down the middle. The next day it has cracked apart, and there in the sheath are the compact seeds, overlapping like fish scales, making a kind of cone with a tail of soft silk made up of myriads of threads. They are moist at first, in their womb, then they dry out and each seed parachutes away, the silky rays darting, swirling, racing high, subject to every turn and twist of air. There will be new populations, out of old circumstances. What happened to the milkweed before this culmination?[Pg 58] How many hairstreak and monarch butterflies paid it a visit? How did it change with change in temperature and moisture and length of days? Where did it come from originally? Next year, if I have not been sent ahead myself, I will stand watch over the plant so as not to miss what might be the greatest show on earth.

We depend on all too occasional visits to understand other modes and rhythms of existence with any depth, although there are times when a chance sight goes deep enough to last. This season of the year the chipmunks are very active, foraging for grains and nuts to store in their hibernation chambers underground. Cats, of which there are far too many loose on the Cape, kill so many chipmunks that it is sometimes hard to see how the population keeps up. (For one thing, these little “ground squirrels” only seem to have one brood a year.) Cats bring them home almost daily, teased into a terrible dance, spinning around like weary boxers on a revolving stage. A chipmunk’s alert curiosity, or habit of freezing into attention, may well be its most vulnerable point. Cats will get them when they are out in the open filling their cheeks with food. They will also come out of the shelter of a hole, or stone wall, to investigate the source of some unusual noise or light tapping, or a whistle, or just stay fixed when a man approaches, in a kind of actively questioning mood.

I hear a scattered dashing in the leaves, and there it is—a striped, bright-looking little animal, tail twitching, arrested in motion, quivering and throbbing, its throat pulsing at a furious rate. We watch each other for three or four minutes. I too have my share of curiosity. Gradually its quick pulsing dies down. It turns its head slightly away, with those moist, black, intent little eyes. With a quick flip it is around a tree, then drops down to run along the leaves again and jump behind a boulder.

It was in no mortal danger that time, but our two lives were brought together into relationship by another danger—the dark universe of chance. I felt it as almost a kind of love between strangers, in which my mental being was in no way divorced from what might lie behind a chipmunk’s eye.

[Pgs 59-60]

I remember another chipmunk, in Vermont this time, whose chosen ground was a hillside pasture. I came on the animal when it was carrying part of an apple up a slope toward its hole, located in the side of a ridge some twenty feet above an old apple tree. When it saw me it dropped the apple, which promptly rolled downhill. Then it watched me with that silent waiting on chance, that throbbing look of expectation which they have, one paw twitching slightly and clutched to its chest. I was quiet, and at a respectable distance, so the chipmunk picked up its food again and hurried back to the hole; but the apple was too big to go in, and it rolled back downhill. This happened four times. The apple rolled down. The chipmunk hauled it back up, turned it around, put it up against the hole, a little like a man facing the problem of moving a large bed through a narrow door. Finally it nibbled bits off the edge, slipped sideways into the hole, and pulled the apple in after it. I stole up as quietly as I could and saw that it was eating away successfully with its food overhead. A problem had been solved, and with a fair amount of intelligence.

The illumination we find in nature does not necessarily come from comparing degrees of intelligence, in which man always finds himself the winner. The light goes deeper. Our analytical ways, our methods of order, imitate an order which is indefinitely resourceful. Sometimes it shows itself past explanation. It is like this September evening after rain. For a short time, ten minutes perhaps, not long before dark, the earth is colored with magic, shadowless light. The grass is intensely green. The sky turns gray and pink. Distant fields are red and astonishingly bright. All colors are sure and strong, joining in pure gradations. The evening is full of mystic peace. A kitten watches the light, transfixed in the doorway (together, for all I know, with some chipmunk by the stone wall outside), arrested by what I in my own silence can only think of as an unmatchable glory, never to return in quite the same measure.

[Pgs 61-62]

[Pg 63]

The ordered days wheel on and fall into patterns consistently new. On further acquaintance, the place I live in seems to extend its boundaries and add to its store of lives. I struggle to understand. The more I add to my list of things as time goes on, the less my crude interpretations fit the circumstances. I started here with a tract of land. I built a house. I have a family. I am not yet sure of my location. The kingfisher says one thing, and the frog another. The snake travels a few thousand feet of home area, and the tern thousands of miles. They are both on Cape Cod. Then one leaves another. All action blows hot and cold with endless variations. A little knowledge makes my center rock with uncertainty.

I am not even a native in the strict sense, and cannot be said to know my way around by feel, as a man might who was born here. I had a talk the other day with a time-honored Cape Codder on the subject of how fish or birds found their way. He was not able to give me any illumination on the scientific aspects of the subject, but when it came to human beings, he did give me some tips on how to avoid getting lost. I had confessed that I once set off in a rowboat and was lost in an offshore fog for the better part of a morning, rowing steadily in the wrong direction.

The next time that happened to me, he suggested, I should drop anchor and wait for the fog to lift. In that dense shroud it is also possible, if you happen to be wading in shallow water, to lose sight of your boat when it is only a few yards away. Under such circumstances he once used his fishing line to help him get[Pg 64] back to the boat by using the lead sinker as the center of a compass, playing out the line and circling until he reached it.

The sea can be a trackless wilderness only a few yards offshore. Natives have been lost in it as well as newcomers. Still, there is no substitute for acquaintance, for knowing the sea’s look and its ways. This man claimed he could feel his way in the fog. In other words, taking in all factors, familiar or deducible, such as the way the tide is running, whether it is ebbing or rising, how the wind goes, and from what quarter, or even guessing direction by the ridges on a sand bar, he could take the right course, without, as he put it “letting my judgment interfere.”

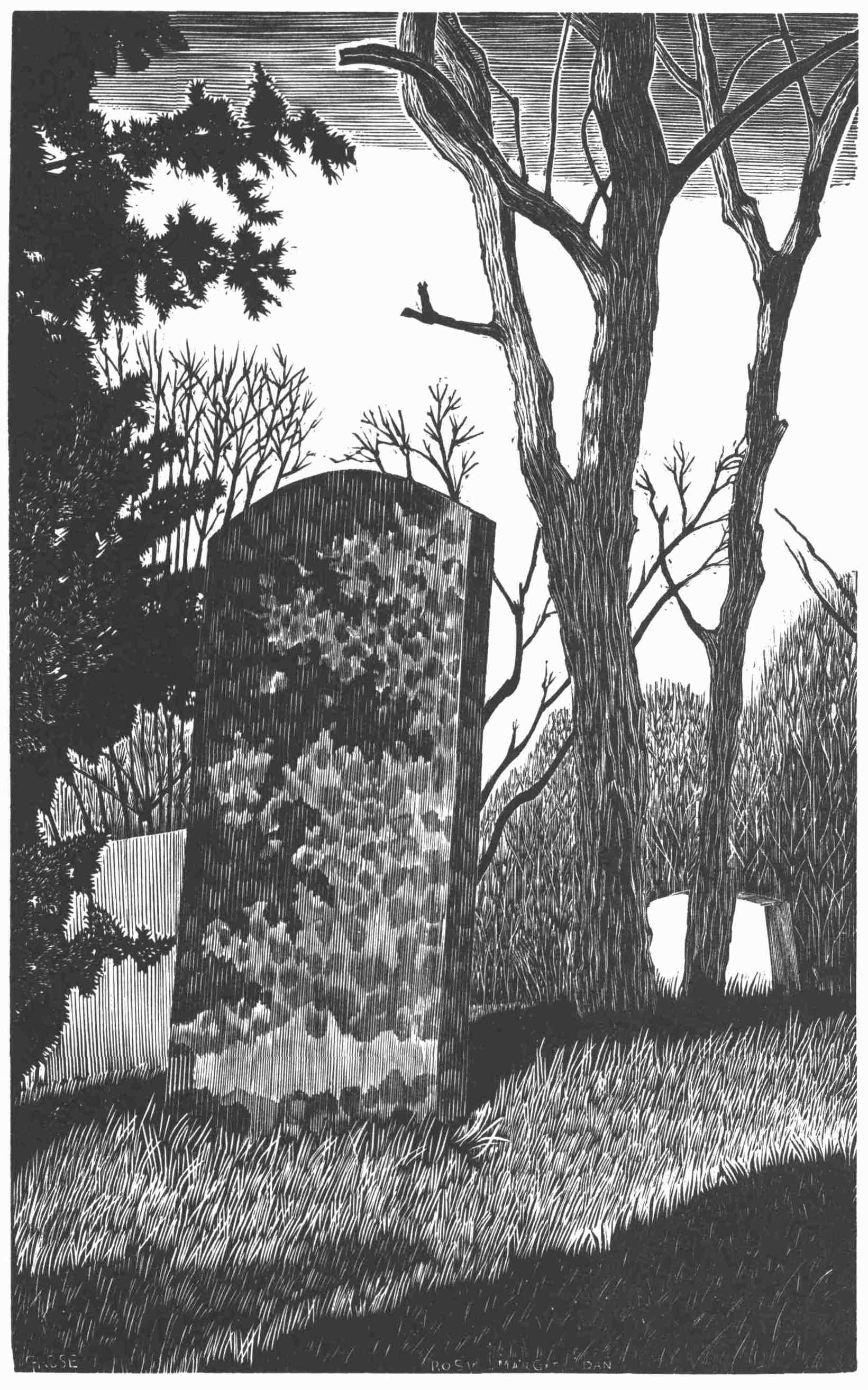

It took me a while just to learn the local compass directions, but now that I have my north, south, east, and west inside me, I am not sure, even walking through the trees, that I will not bump into my old ignorance. It takes time to find your way. A man new to the countryside might well be envious of some of the older inhabitants that know where they are without trying—a turtle, for example. A box turtle’s slow motion over the year seems like a true measure of ancientness. While the birds, the fish, the men depart, this dry land reptile seems to feel responsible for holding back, for the weight of the earth itself. In the springtime I have seen a slow pair approaching each other in a mood of affinity, while the rest of the procreative world danced overhead, and I have seen a female laying her eggs in a sand bank, covering them over with a last shove of her hind legs, then moving away, a little more quickly than usual, it seemed to me, as if to return to the more agreeable task of waiting things out. When fall comes and their cold blood slows, they grow torpid and finally dig out of sight into the ground.

On one of these warm days in early October I hear a slow dragging in the leaves, and come upon a box turtle eating a mushroom. They have beautifully patterned shells, ocher or yellow, sometimes orange, and dusty black, almost batik in design, with many variations. I stand about eight feet away, while it holds its head and neck straight up, watching me. I guess it to be a male,[Pg 65] by the bright red little eyes. The eyes of a female are a darker reddish brown.

His wrinkled red neck pulses a little. His yellow beak and curved mouth line are tight shut under his flat-topped head, with bits of mushroom sticking out on either side. Very comical, he looks; but he stares down any inclination in me to laugh out loud. He watches me without moving for a full fifteen minutes before I get tired of the experiment and go away. Nothing, he seems to realize, can outlast a box turtle. This old male, with his wrinkled red jowls, and his soft, puddled-looking feet, must represent some antediluvian complacency, or, for all I know, a reasonable pride.

In captivity box turtles have exceeded forty years before they died, and some grow to be much older than that, if they avoid being crushed on the highways or killed by forest fires, since they are otherwise invulnerable to most predators, excepting man. This year a box turtle was found locally by a man whose deceased relative had carved his initials on its shell in 1889, making the turtle seventy-one years old. How old the turtle was when so tagged is not known.

They are wanderers—more so, for example, than the water turtles, and with a certain assurance. Within their chosen environment, of open field, shrubby slope, or marsh periphery, they cover a great deal of ground. They seem to carry a staying power with them, and an ancient decorum. They are like old natives true to ancestral places. There is something enviable about this fittingness to home.

Still, I have enough modern restlessness or rootlessness in me to think that a home or piece of land probably has fewer boundaries than ever before. We are going to have to know our location “way out,” as some of the old Cape Codders used to say. I have an equal envy of the terns that are flying toward the Caribbean or the Antarctic. They are birds of the world, in which they know their direction by markers that are light-years away, or so some scientists believe after much investigation. The latest theory is that migrating birds find their way by the sun’s changing position during[Pg 66] daylight hours and by some of the constellations at night. They have a built-in mastery of what it took many thousands of years for man to learn, with his surpassing intellect. They are readers of the stars. Their home is in the wide blind sky.

[Pg 67]